Dr Salwa Gouda Modern Arab Women’s Poetry: A Voice of Resistance and Resilience

Poetry has always pulsed through the veins of Arab culture, serving as both mirror and compass for societies navigating the complex terrain of tradition and modernity. For Arab women, the poetic tradition has been particularly transformative - a sanctuary where silenced voices find resonance and a battleground where patriarchal structures face relentless challenge. The Iraqi poet Nazik al-Mala’ika’s haunting lines from Cholera (1947) - “In the darkness, in the silence, the wails rise... Who will tell the mother her child is gone?” - marked a seismic shift in Arabic literature. Not only did she pioneer free verse in Arabic poetry, but she demonstrated how women could transform personal anguish into powerful social commentary, using their pens to document collective trauma through an unflinchingly feminine perspective.

The mid-20th century witnessed Arab women poets radically redefining their literary landscape. Palestinian poet Fadwa Tuqan, whose work earned her the title “Poet of Palestine,” exemplified this transformation in Enough for Me (1967): “Enough for me to die on her earth/be buried in her/to melt and vanish into her soil/then sprout forth as a flower.” Tuqan’s genius lay in her ability to intertwine nationalist resistance with intimate corporeal imagery, positioning the female body as both metaphor and medium for political expression. This revolutionary approach created space for subsequent generations to explore increasingly bold themes. Syrian poet Maram al-Masri’s I Look at You (2004) pushed boundaries further with its raw eroticism: “I look at you/as a starving woman looks at bread/as a prisoner looks at the horizon.” Such verses didn’t merely describe desire - they weaponized it, asserting women’s right to articulate their own sexuality on their own terms.

The contemporary landscape of Arab women’s poetry reveals an extraordinary diversity of voices grappling with urgent political realities. The late Gazan poet Hiba Abu Nada, tragically killed during Israel’s 2023 bombardment of Gaza, left behind verses that pulse with defiant love: “I shelter you, Gaza, with my last heartbeat/with the ink of my veins I write you.” Her work exemplifies how Arab women poets document war not as detached observers but as embodied participants, their words forged in the crucible of personal and collective survival. Egyptian poet Fatima Naoot’s A Sheep’s Life (2015) demonstrates another form of bravery, confronting religious authoritarianism at great personal risk: “They told me: Be a sheep/The butcher’s knife is kinder than the wolf’s teeth/I said: I prefer the howl of wolves/to the silence of the flock.” For these poets, writing is never merely an artistic act - it’s an existential stance, a refusal to be silenced or subdued.

The thematic breadth of modern Arab women’s poetry reflects the complexity of their lived experiences. Saudi poet Hissa Hilal’s explosive appearance on Million’s Poet with The Chaos of Fatwas (2010) - “I have seen evil in the eyes of fatwas/at the doorways of darkness/where they shroud the light of day” - demonstrated how poetry could become a public challenge to religious extremism, even within conservative societies. Meanwhile, diaspora poets like Somali-British Warsan Shire have given voice to the migrant experience with visceral immediacy: “no one leaves home unless/home is the mouth of a shark.” Their work complicates simplistic narratives of Arab womanhood, revealing layered identities shaped by displacement, memory, and cultural hybridity. Tunisian poet Amina Saïd’s The Saffron Lady (1999) represents yet another dimension, weaving together Islamic mysticism and feminist consciousness: “She undresses the sky at dusk/with hennaed hands/teaching the moon/how to wear its light.” These poets collectively demonstrate how Arab women are reclaiming and reimagining their spiritual and cultural heritage.

The institutional challenges facing Arab women poets remain formidable. Censorship boards across the Arab world routinely suppress works deemed politically or morally transgressive. State surveillance and religious fatwas create climates of fear, while mainstream literary circles often dismiss women’s writing as lacking in universal significance. The Palestinian poet Maya Abu Al-Hayyat articulates this struggle in The Cake: “They told me my poems are too small/that they don’t tackle the big issues... as if the occupation of my body/isn’t the original occupation.”

Despite these obstacles, poets are finding innovative ways to circumvent restrictions. Digital platforms have become crucial alternative spaces, with Instagram poets like Bahraini American poet Amina Atiq and Kuwaiti poet Mona Kareem building international followings. Kareem’s So You Know You’re Not Alone (2016) captures the diasporic experience in haunting fragments: “This is how we love:/with exile’s grammar/ every verb irregular.” Such works demonstrate how technology enables new forms of creative expression and solidarity.

The future of Arab women’s poetry lies in its fearless hybridity and adaptability. Younger generations are increasingly blending poetic forms with multimedia art, performance, and activism. Syrian poet Golan Haji’s collaborations with visual artists, or Lebanese poet Joumana Haddad’s experimental typography, point toward an exciting interdisciplinary future. The rise of collectives like the Palestinian Women’s Poetry Network and online journals such as Jadaliyya suggests growing institutional support for these voices. Most importantly, the poetry itself continues evolving, as seen in the work of emerging voices like Emirati poet Afra Atiq, who blends Nabati traditions with spoken word, or Sudanese American poet Safia Elhillo, whose The January Children explores postcolonial identity through fragmented lyricism.

What makes contemporary Arab women’s poetry uniquely powerful is its refusal to be categorized or contained. It is at once deeply personal and resolutely political, rooted in tradition yet radically innovative. As Syrian poet Najat Abdul Samad wrote in When I Am Overcome by Weakness (2016): “I bandage it with the outcry of a mother/ who lost her child to a bombing.” These words capture the essential duality of this poetry - it is both wound and suture, bearing witness to brokenness while insisting on the possibility of healing. In classrooms and protest marches, on social media and in underground journals, Arab women’s poetry continues to “sprout forth as a flower” from the hardest ground, as Fadwa Tuqan prophesied. Its resilience lies not despite adversity, but precisely through its unflinching engagement with it - a lesson in how art can survive, and even thrive, under the most oppressive conditions. For readers worldwide, engaging with this poetry isn’t passive consumption; it’s an act of solidarity with voices that refuse to be erased, and a recognition that their struggle for expression is inseparable from the universal human fight for dignity and freedom.

Chaden Diyab

Chaden Diyab is a Syrian chemical engineer holding a Ph.D. in Environmental Science from Pierre and Marie Curie University in France. She has worked on numerous environmental and technological issues between Europe and the Middle East and has made significant contributions to raising environmental awareness through research and books. Among her works are several poetry collections, including The Soul Player (2022) and Invisible Faces (2023). She has also authored a children’s literature book titled Paris’ Journey in Space, which includes six activity booklets focused on environmental education for children. Additionally, she is the screenwriter for the film Hope, which addresses the issue of Syrian refugee children in the city of Urfa on the Syrian border.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

The Invisible Faces

Do not write, For your poems Raise voices From the lofty body And announce revolutions… And ring… The danger bell.

For I claim To be revolutionary, But I fear The bodies of women… So I hide them, And their freedom… So I smother it.

For I am a democrat, Madam… I have raised flags And sharpened claws To seize your poems… And I mix the freedom of my desires With betrayal To savor My pleasures….

Do not write, For I fear Your words, And I tremble Under their judgment, And I shiver…

At your strength and your tenderness.

continued overleaf...

Do not write, For I despise my own softness… That you draw from my depths, And the man I become For a few moments in our embrace…

Do not write, For I hate your flowers That you scatter On your lips… And the roses In the strands of your hair, And my weakness… When I touch Your limbs.

Do not write, For you would reveal My secrets, And you would teach The crowds my path, And you would tell humans And spirits How to craft love For stranded souls… on the shores of my civilization.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Fatima Harsan

Fatima Harsan, born in Qamishli, northern Syria, is of Kurdish origin. She studied Arabic at the University of Aleppo and taught Arabic in Qamishli and Raqqa for 15 years before seeking refuge in Sweden in 2001. There, she obtained a teaching qualification and worked as a mother tongue teacher and assistant for Arab students in Örebro. In 2016, she founded the Kurdish Culture and Language Center, organizing multilingual poetry evenings featuring Arab, Swedish, and Kurdish poets. A writer of free verse and flash poetry, her works have been translated into Swedish, Italian, French, and Kurdish. She has participated in poetry events across Sweden and Germany and published three collections: “The Earrings of the Air Still Ring” (2018), “The Expansion of Love in My Pupils” (2025), and “Fatima’s Palm and What It Writes” (2025), the latter being a selection of her works translated into Swedish. Her poetry was also featured in an anthology of Kurdish women poets translated into French and English.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

To Be a Painting

Words often trouble me, silence preoccupies me— so much that I’ve started learning sign language. Inside me, a desire: to hold a brush and colors, to cut through heavy speech, to be read in images. I trace dark blue hues on my shoulders and neck, slick green algae spreading across my body, two dark clouds on my face, above them, eyebrows knotted by bright lightning, and a mouth with a tied tongue. Wings as wide as my hands, and a lone bird curled into itself, refusing to leave my heart.

A Leather Bag

I carry with me a worn-out leather bag, always clutching it by its neck. I don’t keep a perfume bottle or lipstick inside, unlike other women.

My bag holds a bundle of keys, blank papers and a pen, painkillers, and a sublingual spray to correct my heartbeat. A necklace indicating my use of strong blood thinners— in case of a sudden fall— to save me from internal bleeding.

I grip the keys tightly: The car key—”my strong legs, never panting.” The work key—anchors my existence, fuels my hurried steps. A key for family—I cling to it for mercy. A key for friends—I hold it tight so none slip away. A key I guarded fiercely, clutched hard, hoping for the brightest future— I lost it in the blink of an eye. Since then, my heart has bled, and I curled into myself. Years passed, and I folded the bleeding. I was damaged in many places, set the bag aside, found myself, tried various relaxants, trained in yoga, steam baths, enjoying nature.

But the veins in my hands still bulge like the threads of that bag, my skin is stained, and my spasm remains the same, right at the neck.

Fawzia Alawi Alawi

Fawzia Alawi Alawi is a Tunisian poet, novelist and essayist who has published nine poetry and short story collections, in addition to a novel entitled “Faces for One Woman” (2020). She also won several national and regional awards.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

What If We Were Trees

What if we were trees, our roots entwined in some far-off earth, drinking in the scent of hidden springs, nourished by the milk of stones and the unquenched lava of volcanoes?

What if we were acacias, sycamores, or willows lost in light’s embrace, kissing the details of shadow? Why not be apple trees, perhaps, to retell the tale of temptation, mount the steed of knowledge, search beyond those distant dunes and hills robed in life’s green?

Surely, we’d weave into our souls what birds teach of idle chatter, what leopards know of desire’s fierceness, what clouds murmur in water’s hum.

Trees we’d be, filling valleys with fruit, letting nightingales nest in our chests, deer sleep against our trunks, and among the buds of our sighs, songbirds would sing.

Then surely, there’d be no war, no blood, no orphans, no widows, no wailing— only reed flutes, seasons of grapes, and cups brimming with fragrance and love.

Hanaa Metwally

Hanaa Metwally is an Egyptian writer born in Mansoura, holding a bachelor’s degree in foreign Trade from Mansoura University. She has published several works, including the novel A Day Left to Kill (2024) and the short story collection Three Women in a Small Room (2025). She won the Suad Al-Sabah Award in 2019 and received grants from both Mufradat and Al-Mawred Al-Thaqafy foundations. Her play Philosophers Don’t Know Love was longlisted for the Doha Drama Award.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

Caramel Tears

Before you read, imagine yourself in front of a theater stage. The events unfold here and now, not there and then.

Characters and Props:

An offstage voice—a dignified, grieving woman; a group of women in mourning attire but without sorrow; a radio reciting verses from the Holy Quran; a man serving black coffee; numerous elegant ceramic cups; a cloud of cigarette smoke; a framed portrait of a handsome man adorned with a black mourning ribbon beside a slightly aged wedding photo of the same man; a heavyset man; a thin man; a frying pan caramelizing sugar; eggs dissolving in milk.

Scene One:

Setting: A home reception room.

The offstage voice hums a French funeral melody for a minute before fading away. Time: Night. The hands of the Victorian-style wall clock near the handsome man’s portrait approach 9:30 PM.

Decor: Elegant, orderly European-style classical furniture, exuding the scent of cleaning fluids and fresh air freshener. The furnishings are monochromatic. The women form a circle around the dignified, grieving lady, who weeps silently. She lifts her face with pride, enduring condolences with stoicism. The offstage voice returns, humming the French funeral melody as the curtain slowly closes.

continued overleaf...

Scene Two:

Before the curtain rises, a large sign drops with bold, colored letters: “One Week Earlier.”

Setting: A bedroom. The walls are painted in shades of fuchsia. A wedding photo of a handsome man and an elegant woman hangs on the wall. A soft bed. A man sleeps beside a woman in a white nightgown—bare-chested, arms exposed. The man wears traditional sleepwear.

The woman jolts awake, turns on a soft light that illuminates her delicate face. She gazes at her sleeping husband, wipes salty beads of sweat from his forehead, kisses his cheek, sips from his lips, runs her palm over his head. The husband turns away. She adjusts the cold AC, places her left hand on her heart, turns off the light, looks at him once more, and blows a fleeting kiss to his lips.

The curtain closes softly as the offstage voice plays a French funeral melody.

Scene Three:

The large sign drops again, now reading: “One Day Earlier.”

Setting: A clean, elegant kitchen open to a refined dining area. The woman wears a sand-colored mid-length skirt, dark thick stockings, and flat shoes, her upper half hidden under a floral-printed blouse.

She moves like a busy bee—swift, efficient, and organized. The aroma of spices, the sound of sizzling oil, and the steam rising from the electric oven whet the appetite. She endlessly dusts and sprays fresh scents.

From stage right enters the handsome husband, accompanied by a kind-faced heavyset man and a witty thin man. The three sit around the table. The woman approaches, smiling warmly, welcomes the guests, and arranges the dishes neatly. She sits opposite them, her gaze lingering on her husband’s face.

The Thin Man: The food is delicious, as always

The Heavyset Man: I can’t stop eating—I need a spare stomach! Lucky man, you are.

The Husband: (Laughs hysterically) It’s only fair she excels at something to distract from her failure to bear a child, unlike other mammals.

(The lights dim until darkness swallows everyone. The offstage voice—a woman’s sob—plays a French funeral melody.)

Scene Four:

At an ambiguous time...

The woman is curled up on the bathroom floor. The monotonous sound of dripping water. Her wails are like a wounded animal bleeding out. The stage is dark except for a faint spotlight casting her shadow. The husband’s voice comes from outside. Husband: You forgot to make the caramel cream. I want it now—immediately. (Darkness swallows the shadows. The curtain falls.)

Scene Five:

The Kitchen.

The woman still weeps. Her crying turns into muffled sobs, yet she buzzes with activity like a bee. She places sugar in the pan, lights the flame. The milk boils. She cracks eggs into a small bowl, whisks them with an electric mixer. Tears fall into the pan—the salt threatens to ruin the caramel. She wipes her tears, fixes the caramel, but new tears fall, nearly spoiling the mixture again. She pours the milk and egg mixture into the oven, separated from direct heat by a water bath. She returns to salvage the caramel—another tear drops. She removes the custard, places it in an ice bath to cool, then into the fridge. Her eyes pour endless tears. She takes it out, now firm, prepares the caramel, but tears drip in again. Her sobs grow more agonizing. She pours the caramel over the cream set in an elegant mold. A spotlight follows her as she carries the caramel cream to her husband, seated on the couch in the dining room, watching TV. He devours it greedily.

The clock spins rapidly. The husband’s head droops to his chest—never to rise again. The offstage voice—a woman humming a French funeral melody.

Curtain.

Hawaa Al-Qamudi

Eve

(In Praise of Farewell)

Grant me time to bid you farewell, like Adam and Eve at their first meeting naked, groping each other. I count your fingers and touch them with my lips, I taste the coffee’s bitterness, and I swoon when I feel the rebellion of your shoulder blades on your back. What does your mole tell me when my lips play a scorching longing, and when my hands coil around your trunk?

Grant me a moment to kneel before you, drench me in the milk of your desire, so I may pray like a sorrowful goddess whose time of fertility has passed. I wash your feet with these tears the milk of a strange soul that has lost you.

Time to bid you farewell, so I may understand why I was cast out of Paradise...

Hawaa Al-Qamudi is a Libyan poet who has published three poetry collections. Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

In Praise of Absence

Oh Lord, It is love the key to the soul, the elixir of the heart, the body’s whinny.

Death is when your fingers no longer speak to me, when your kiss is cold, just a bite of the lip, when your heart no longer feels my breast, and your chest has no room for my joy. And when my fear crumbles between your arms, it finds you heedless of my moans.

I am no angel I am just that girl who loves you, who names night and day after you, who calls out to the sea by your name.

She understands your soul, loves your scent, licks the sweat of your fear. But exhaustion has gnawed at her heart, the roads have bitten her feet, and she fears she won’t find you.

Mastoura Musfar Al-Arabi

Mastoura Musfar Al-Arabi is a prominent Saudi poet, literary critic, and academic specializing in modern literature and criticism. An influential cultural figure, she co-founded the Professional Literature Society under the Ministry of Culture, chaired the Poetry Platform at the Arab Poetry Academy, and served on cultural committees for major events including Jeddah Book Fair and Okaz Cultural Market. Her poetry has been translated into Spanish and English, featured in international festivals across the Arab world, and included in the Encyclopedia of Arab Women’s Poetry (2021). Her notable publications include poetry collections like “What Confused Me... What I Never Left” (2020) and critical works such as “Meaning-Making in Saudi Poetry” (2020), with her creative and academic contributions being the subject of scholarly studies and the critical book “Revelations of Meaning” analyzing her poetic works.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

A White Space

Between me and others, there is a white space a shadow leaning toward the heart, a tendency to overlook. Life is simple: it asks that we cast off our shoulders the burden of suspicion, that we indulge in whiteness. Between me and others, there is another poem, spoken without confusion, a regal desire gazing toward what comes with hanging dreams and wide questions.

About a Biography in Water

Like a hand waving in the air, Like a traveler without the furnishing of a path, As the bow hums before an intended strike, I chose not to reclaim from the tale my forgotten role and I crossed eternity alone!

About a biography in water, I thirst to test my singularity.

My anxiety is a skittish gazelle in the wind, reading what it can of the blood of disappointments, mixing the fire of my days with the honey of my rebellion.

No Way to Sway Me

I believed in myself, so I plucked the apples of misguidance alone, and I drank alone.

I am the entire lexicon of femininity, all of it, and water is my aim!

Washed in cold to my very end, I let the windows crave, and I love my coldness!

I am my pride no way to sway me, so no proof can save you, and no doors remain beyond me!

Nehad Zaki

Nehad Zaki is an Egyptian poet, journalist, and writer, born in December 1987. Recognized for her evocative literary voice, she was awarded the Buland Al-Haidari Prize for Young Arab Poets in 2022. Beyond poetry, Zaki is a multidisciplinary artist with a passion for drawing, fine arts, film criticism, philosophy, and literature. Her intellectual curiosity spans the broader human sciences, enriching her creative and analytical work. In February 2022, she published her book “As If It Were the Resurrection”, a collection that further establishes her as a compelling voice in contemporary Arabic literature.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

The Mask

I know this face it’s an old copy of me. You can hear the clatter of its bones being ground. All that remains of it is buried between millstones in the same ancient cellars my grandfather took as refuge in his battle for survival.

The White Land

The sirens won’t reach your ears, and the light in your room could draw the shells— as it pleases them.

A fruit fly shatters your patch of sleep, yet not a finger is harmed.

You defeat them by not existing, and they defeat you in their imagination.

They don’t know you’re still alive in the belly of a whale.

And you’ve mastered the act of your death scene, leaving your upper half dangling off your bed in the bedroom.

The Old Man of the Port

I cross the lake that separates my bed from reality and step with my earthy feet.

I open my door to strangers— in loneliness, they are homeowners.

Passersby, friends you already know you’re bidding farewell.

And like an old man dwelling in the port, I’ve perfected goodbyes just as I’ve perfected meetings.

No forced affection, no fake smile, no tear hanging in the eye’s socket.

On the sidewalk among the bags, you can test your grief every day like testing coincidences.

And beware of what?.

We cry before each other without feeling shame.

If only we were whales now...

continued overleaf...

When we become whales, my love, when we swim in the endless ocean and merge with the blue, so no barriers remain between us and it.

When we dwell in the depths, we no longer fear it, and a kinship is born between us and the seabed.

When we discover the possibility of singing without needing an orchestra, and we chant with bubbles of air our daily verses.

When water becomes our home, my love, we will be happy.

Photograph courtesy Pixabay.

Rand Al-Rifai

Rand Al-Rifai, a Jordanian born on October 6, 1977, holds a master’s degree in accounting and finance and is currently pursuing a PhD in the same field. She has worked as a lecturer in accounting and finance at various universities and community colleges. An active cultural and social figure, she is a member of several professional and literary associations, including the Jordanian and Arab Trainers’ Unions and the Council of Arab Writers, Literati, and Intellectuals. Her first poetry collection, “With a Serious Heart” (2021), was supported by Jordan’s Ministry of Culture, followed by a second collection, Cuneiform Tablets (2024). She is preparing a third poetry manuscript and a novel titled Hala 30 and has published critical articles in Jordanian and Arab cultural magazines while participating in numerous literary festivals and events.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

Children of Adam

The mosquito may hate me, May feel insulted to be killed by a shoe. One who witnessed her brutal death may lie in wait for me, May come for vengeance—blood for blood is the law of the tribes.

The ants of the earth may resent me, Because I destroy all their homes And wipe out their entire colonies. To them, I am a blind slaughterer,

Who coldly burned their young alive. Yet I wore a sheer shirt, Sang like a sparrow, Danced like a field butterfly, Drunk on the scent of roses, Drowned in pleasure— Until it died like a martyr.

For I am Adam of this earth, The one who broke its virginity to plant wheat, The one who betrayed its affection. I beg when it resists, But when it yields, My soul turns disgusted.

I am Adam of this earth, The heir and the master. I am Adam of this earth, Come for a time as punishment, And in the end, I return as I descended— With no briefcase, And no throne.

Death

And the worst of death Is to dissolve like shapeless clay in a potter’s hand, Without meaning, To become just a memory Murdered by time, then forgotten… To venture alone into the boundless unknown.

Death is the last one you meet, Your final covenant with disappointments, Your last pact with questions, The last thread binding you to sunlight, The end of all covenants.

Death is the closing reel of your path— Whether you were first or last, A prince or a bastard, An angel or a devil, Great or small— It makes no difference. Alone, in your naked body, you will return.

Your death reduces you to a grain of sand— Weightless, faceless, nameless— Just a number among the counted.

Death is the first to answer you: Who are you? How did you go? How did you return? How will you move on?

It is your first step toward Paradise— Alone, without companions. The first unseen you comprehend, The first unknown you truly live, Without pretense. It is your great awakening, While people bear witness.

It is the death of power and the executioner, The death of darkness, The death of pain and regret, The death of chains.

For though loss is sorrow, Loss is a matter for the living— It means nothing to the lost.

It is the death of death itself—so do not fear. Walk your path with love, And let death be your friend.

Rasha Ahmed

Rasha Ahmed is an acclaimed Egyptian poet and cultural editor whose evocative verse explores themes of absence, longing, and the quiet fractures of the everyday. Her published collections—marked by lyrical precision and emotional depth—include The Boredom of Losses, It Was Nothing but the Water of My Heart, With a Pale Light, and An Empty Seat Weary by the Light. Through sparse yet resonant imagery, Ahmed’s work traces the edges of memory and desire, often blurring the line between personal lament and collective melancholy. Her voice, both intimate and expansive, has solidified her place among contemporary Arabic poets who redefine silence as its own language.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

What I Usually Do

What I usually do is try to catch your name as it slips from my mouth, its wings fluttering in the room like my fists in the air.

What I usually do: open the suitcase of illusion, cast a glance at life— its glimmer comes fleeting, then enters the illusion.

After that, I do nothing important, only... smile at the truth with much sorrow.

To Roland Barthes

Forgive me— the hour has grown late. Does love arrive late?

I will answer you: It arrives late, always.

Barthes, I know him.

I met him once by chance, my lover and I, in an old tavern by the sea. He proposed to us twenty entrances to love. We didn’t believe him.

Why did you stammer as you unraveled the story’s dust? What a fool you are!

A lover does not complain of love, but when the rain grows heavy, the doorknob slips from their grasp.

Barthes, my lover repeats that he never wore masks, that meanings never betrayed him, nor description, nor the snares of glances. Only— he was very lazy. Each time he neared our shadows—

Barthes, do you love Umm Kulthum? Did she light your night with sighs? Did she toss her handkerchief into the pleasure of the text?

Tonight, I will celebrate you. I will pluck the world from your chest, and my lover and I will laugh as he leans on my shoulder. Just leave your masks at the door, so I may arrange the story well, like bread upon my head: the birds eat from it, and I starve.

Then my sighs descend from the sky. My burning in him was an ache— nothing but an idea that visited me, like the unconscious that precedes the shadow.

When he says I love you, have you tried to outrun them both at once? Has a kiss ever stung you from parched lips without the panting of longing?

The signs my lover inscribed on my body— I follow them like a teenager in love with a lighthouse keeper, who delights in life at night while misleading every ship until they burn on my shore.

Thus Spoke the Poetess

This is how I managed to make you believe I am a poetess. I always sit in the back row, lean on the margins, and leave a transparent barrier between you and me, so you think I am drowning in the fog of metaphor.

So, you believe the cold in my eyes is grief! That the indifference in my voice is an old wound or fracture! That the echo of emptiness inside me is the chime of laughter!

This way, I wrap myself in darkness so you won’t see the shattered mirrors on my face, so you won’t notice the howling inside me, so you won’t realize I’ve lived a life without a shadow. This is exactly how I deceived you.

Safaa Elnagar

Safaa Elnagar (b. 1973) is an Egyptian writer and scholar with a PhD in Media (Radio and Television) from Cairo University. Her notable literary works include the short story collection The Girl Who Stole Her Brother’s Height (Merit Publishing, 2004), the novel The Resignation of the Angel of Death (Sharqiyat Publishing, 2005), and the short story collection The Maidens Shell Peas (Rawafed Publishing). Her academic and creative writings explore social and political themes in Egyptian society.

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

Dark Intervals

As is his new habit, he dries my hair, but today his hands reach for my neck, feeling the veins, and I burst into laughter. When his lingering hands reach my ears and encircle my face, I slip away from them and run from him, caught between the naivety of my giggles and my panting breaths.

His behavior has changed! Sometimes he asks me to sit across from him, and I settle into the chair he points to. Silence stretches as he stares at my face, as if searching for something he’s lost.

Perhaps it’s her picture—the one he hides in his wallet. He loves her, yet he cuts her off, even after death, refusing to recite Al-Fatiha for her. He can’t forget how she left him as a child, sucking his fingers, only to move to another man’s bed as soon as my grandfather died, before she even took off her mourning clothes. And he can’t forgive her for dying before he became a man who could defend his right to her.

Other times, he warns me against playing with the neighbors’ boys, threatening to break my neck if he sees me talking to one. I didn’t need his warning—before his shadow even fell over the street, the chain of play would lose a link. Once, he caught me off guard, suddenly looming over me, yanking my hair and hitting me. My mother tried to calm him, to pull him away from me. After he let me go, she held me in her arms and scolded me:

“Didn’t I tell you not to stay out late? You’re grown now.”

Then she’d go back to insisting that I was almost a carbon copy of her… my grandmother, who never grew old. That’s why she could never let go of her men—except for my father, who was merely her son, stealing her motherhood before she returned to her true self: the stranger’s woman.

continued overleaf...

His staring intensifies, and the innocence of my features fades. I become a woman painted in rainbow colors, undressing in men’s hands. Our faces blur in his eyes, and when we meet, I don’t know who he sees. I lengthen my braid, hoping he’ll notice it, but the fiery hair always flares in his gaze, and the number of men who undress me in his mind multiplies.

Ever since her image possessed him when he looks at me, I can’t sleep with any part of my body exposed. Even if I’m wearing pajamas and pants in the summer heat, I must be covered—even if just by a bedsheet. I look like a mummy wrapped in linen, submerged in death. I’m asleep, but all my senses are awake, circling me like a pharaoh’s curse lying in wait for whoever opens the tomb door. At the slightest shift in the air of the room, my eyes snap open, and I pull the cover from my face like a sentry in old tales announcing his vigilance with a shout:

“Who’s there?”

The nights multiply when I uncover my face and ask if he wants something. I reassure myself with an answer: “The matches are on the desk.” I’ve made a habit of keeping a matchbox there so that if the power goes out, I’ll have a light source. It happens again and again, and each time, the matches remain untouched in their place.

The dragon’s breath from the distant East strikes my head, and fever sweeps through me like an endless storm. It starts with a headache and chills running through my body. Heat rises from my skull, soothed only by cold compresses, though they do nothing for the ringing in my ears or the reel of memories and delusions spinning relentlessly in my mind’s eye.

Coming home from school, I rush up the stairs to our top-floor apartment. The neighbor’s son, descending just as fast, bumps into me—deliberately—his arm brushing against my chest, which always leads my leaps. He apologizes with wide eyes, but I ignore him, cursing his audacity in my head. Before I reach the last step, fragments of their argument reach me, some sharp, others fading away. I approach our door, and before I press the buzzer, I hear her scolding him with reproach:

“Not even the neighbors’ daughters are safe from your antics… Shame on you! She’s practically a bride now.”

“Shame? You’re the one who’s lost her mind.”

As soon as I enter, silence falls after my mother’s kiss and my father’s warm welcome— which my mother calls excessive coddling. Beyond that, a heavy quiet, breaths held between a woman resigned as a peasant, fresh from her village in her black galabiya smelling of earth, and a man who never stops staring and searching. My head burns hotter, like a rocket defying gravity, and my mother still presses compresses with one hand while massaging my legs with the other. I don’t feel their weight—just their pulse, hinting at a pain I can’t grasp.

The night drags on, my mother still beside me, sleepless. Through the flames gathering in my eyes, I see him pat her shoulder, urging her to rest while he takes over the compresses and massages. When she refuses with a shake of her head, he insists, soothing her hand, telling her to go and rest—though worry is the only comfort I know.

Minutes pass monotonously between compresses, the embers of fire flickering. Between waves of pain, I feel the fever—not in my legs, but in the hands massaging them…

A shiver runs through me again, and fumes rise from my head, forming images from the movies I’ve watched—dogs sinking claws into my flesh, a wolf clamping its jaws around my neck, stealing my soul. Then comes the fiery-haired woman—her eyes gleaming with allure and temptation. I fear her, yet I want to be her. And the neighbor’s son peeks at my legs as I climb and descend the stairs.

The hands move up from my legs, past my knees, slithering further, creeping like a snake, its hiss feverish as hell… lying in wait like death. My throat dries like cracked earth. I try to open my eyes, unable to distinguish between the fire in my head and its nightmares. His face appears on the red mesh, a vein pulsing from heat—not the fever consuming me.

I gather all my strength and look into his eyes, his hand stiff on my bare thigh. I push it away, and the flying strands of hair turn into long braids. His hand jerks back, and I break free. My voice gathers to ask:

“Do you want the matches?”

Without guiding him to them—as I usually do—he turns his back, forgetting to cover me.

And as I come home from school, rushing up the stairs to our top-floor apartment, the neighbor’s son bumps into me again—just as fast, just as deliberate—his arm brushing my chest, always ahead of my leaps. Before he can apologize with wide eyes, I unbutton my blouse and let him catch me in his arms.

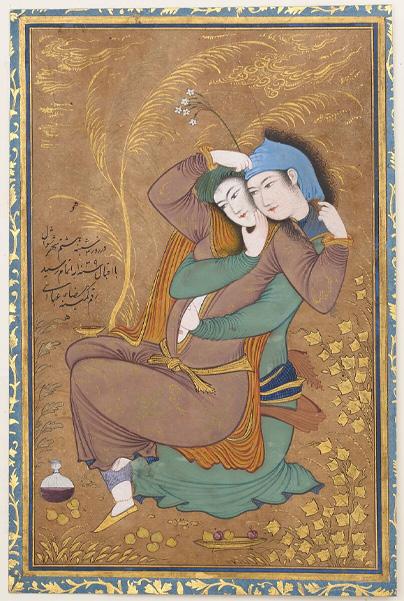

The Lovers, painting by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi (Iranian, ca. 1565–d. 1635).

Sheren Fathy

Sheren Fathy is an Egyptian writer, born in November 1982. She graduated from the Faculty of Pharmacy and has published eight literary works, including novels and short stories. She won the 2023 State Encouragement Award for her novel Leila’s Threads and the Sawiris Cultural Award for her short story collection The Heroine Doesn’t Have to Be Fat

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

Paper Days

The days passed by with unbearable slowness and loneliness. She didn’t even realize when she became entangled in that strange habit. She would tear a sheet from the exam results plastered on the wall and chew it in her mouth. As her saliva mixed with the taste of starch and the ink of that cheap paper, she felt a strange comfort, a beautiful numbness spreading through her limbs.

She had learned this habit as a child, whenever her father punished her for a mistake she had made—a misspelled word, a stained or torn dress she hadn’t noticed. She always felt the punishment was unjust, so she searched for a way to erase the bad memories from her mind. She learned to eat the days when she was punished, whether by beating or by having her allowance withheld. She would eat the past days, sometimes adding two extra, just to make sure everything related to that memory was completely wiped away.

Her parents noticed the missing exam papers, but they paid no attention, assuming some child was making paper boats or toy guns to play with.

On her fortieth birthday, things were different. She felt no satisfaction toward the years that had passed, especially after returning from her ill-fated trip to Alexandria... where she had failed to meet the love she had waited for so many years to return from abroad. He had come back, but not into her arms as she had hoped. She began to resent all her past years. She realized that all the paper she had eaten tasted the same. The flavor didn’t change from Saturday to Tuesday, or from March to October—even if the years printed on the exam results in bold numbers were different.

Time had passed her by without fulfilling her dreams or even remembering her. As a child, during hide-and-seek, she often wished she would never come out of hiding. The idea tempted her greatly—when she pressed her face against the wall, closed her eyes, and counted to a hundred, giving the others time to hide. How she wished she could just turn away from the world forever, disappear into the wall, merge with it, and never return to finish the game. But she hated blind man’s bluff, where someone tied a scarf over her eyes.

continued overleaf...

That game hid her from the world but didn’t isolate her from it. There was no wall to cling to; everyone didn’t hide from her—she could feel them, hear them, their hands reaching out, their voices suddenly closing in from all directions without warning, impossible to stop.

She thought of building a high wall. She would hide behind it from the world... She would carve a hollow inside it to slip her arm through and walk embracing it. It would be flexible, bending with her, adjusting in height and width according to her needs and the streets she passed through. She would make small holes to peek at the world when she wanted to look closely. The holes would let her see without being forced to endure the stares and scrutiny of others. She would watch them like a god, unseen. She would widen the holes if she needed to reveal a part of herself to someone... but most of the time, she would keep them closed. And she wouldn’t remove the wall until the world’s noise had completely faded.

She had finished her studies, spent years in language courses, then her master’s, then her Ph.D. Yet even after all that, she never got the job she wanted, nor the life partner she had waited for.

On her fortieth birthday, she didn’t blow out the candle. She let it burn until it extinguished on its own. She rubbed her hands together vigorously in front of the burnt-out candle, grinding them against each other. She heard the sound of her finger bones grating. She lifted her palms to her nose, searching for old scents clinging to them—hazy memories, the remnants of an old love story, the medicines she used to sort for her parents before they passed, the ink of late-night study sessions, the tension of exams. She looked for gentler smells but found none.

She returned to her habit. She devoured the past week, but it wasn’t enough. She consumed the entire month. Before she knew it, she was swallowing the entire exam results sheet on the wall... She didn’t just suck the paper’s juices or spit out the crumbs as usual—she forced herself to swallow it whole. She felt the days and months seeping into her body. Time mixed with her saliva before sinking into her stomach, carried by her blood through her veins, flowing to every part of her.

One year wasn’t enough. She opened her closet, stuffed to the brim with untouched exam results—years she had kept imprisoned for sudden bouts of hunger. She devoured decades without feeling full.

She felt time gnawing at her bones, thinning them. She didn’t need a mirror to notice the massive amounts of white hair invading her forehead within minutes, nor the deep, thick lines carving arcs under her eyes and around the corners of her mouth.

She traced all the changes that had come over her, and before she knew it, she was stuffing more paper, more years into her mouth... She kept chewing and swallowing until she had consumed all her remaining years in one go.

Touria Majdouline

Touria Majdouline is a distinguished Moroccan poet, novelist, and university professor with a Ph.D. in Criticism and Modern Arts. An award-winning writer, she has received the Nazik Al-Malaika Poetry Prize (2011), the ISESCO Prize for Cultural Work Development (2012), and the International Excellence Prize in Cultural Work (2024). She is an active cultural figure, serving as a founding member of the Association of Creative Women in Mediterranean Countries, head of the Moroccan-Andalusian Friendship Association (Ibn Rushd Forum), and an advisory board member of the Lebanese magazine Manarat. Her acclaimed works include poetry collections like A Sky That Slightly Resembles Me (2005, translated into Spanish) and Nothing More Beautiful (2023), the novel The Trace of the Bird (2025), and the critical study Vision and the Mask (2016).

Translated from Arabic by Dr. Salwa Gouda.

A Free Woman

In my mind, I intend to return language to its rightful owners And content myself with gestures For whenever I forget time, I grow wiser. I begin giving names to the years And colors to the days, And perhaps, out of sheer boredom, I read pre-Islamic poetry, Amusing myself with the shadows of regret on time’s face. No—I have forgotten nothing. All nights are mirrors for remembrance, And there is no distance for absence. All speech is windows for presence. I simply save a few breaths for myself, And perhaps, in the last third of the night, I ring the bells of truth.

I care not for what was or what will be.

I do not knock on rhetoric’s door to reach truth, Nor do I wander in imagination like butterflies. My tongue is no longer an oasis of metaphors No moon grows old in my sky, No anger sprouts at the edges of speech.

Alone, the evening and I Share a balcony at sunset, Then slip into night’s embrace With fewer dreams, less sleeplessness, And enough shadows for forgetting.

continued overleaf...

Who are you?

The critics and guardians of meaning ask. Even I wonder who I am. I have no thresholds for first readings, As the critics have taught us. And my heart, broken by longing, Has grown light Just as I wished a year ago.

And my wounded shadow, Which once collapsed like a drowning man on my shores, Or flailed hopelessly like a shipwreck in the Atlantic, I now stretch into space and plant within it, Drawing many suns upon it, And from their transparent light, I distill words, Singing for the little time that remains:

I am a free woman. And above all, I was not the one who led Adam to the apple. I merely grew tired of sitting beneath the lush tree, So I stood To strip away the shadows coiled around me.

That beautiful, clumsy apple took Adam’s hand And burdened me with the sin of women. Now it is good for nothing, Powerless to rewrite history again.

I am a free woman. I do not remember where I last met my bitter features. My hands once sought refuge in water, My body weighed down by wounds, The earth bewildered, restless with anxious steps, The sky a forest of metaphors.

I crossed time standing like a spear, Gazing into the flame. I left the land that witnessed my toil And carried my borders with me to another exile. I built a voice for echoes, A roof for my small dreams, And forgot to change the sky!

This is me A woman, utterly free. I have no dream Except to die in full vigor.

Cover artwork ‘Paintbrushes’ by Irish artist Emma Barone