LINACRE NEWS

As summer gently winds down and Oxford takes on that unmistakable golden glow, I have found myself reflecting on the things that make Linacre such a vibrant, connected place. High among them are sport and music, two seemingly different pursuits that share one vital purpose: bringing people together.

Rowing has long held a special place in College life, and for good reason. It is about far more than physical fitness and early mornings. It is about shared goals, resilience, and the camaraderie that can only come from pulling together, literally. This year’s Summer Eights were a perfect example of sport at its best. Linacre fielded four crews, with rowers from 13 different nationalities. That diversity wasn’t just a backdrop: it was a strength. Together, they achieved something remarkable: the Women’s First Eight won blades, bumping successfully

on each day of racing. It is no small feat, and a proud moment for the entire College. The cheers from the boathouse were louder than ever, especially with supporters such as our Chancellor, William Hague, there to cheer them on.

But community spirit at Linacre doesn’t end at the riverbank. Music also plays a central role in drawing us together. This year, the College Choir and the University of Oxford Postgraduate Orchestra (founded and based at Linacre) gave a stunning outdoor performance that included Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Oxford Elegy, a rarely performed and notoriously demanding piece. And yet, in true Linacre style, our members rose to the occasion. The performance was deeply moving, not just for its musicality, but for the clear sense of connection between performers, and the joy of achieving something difficult, together.

Our Choir has sung in eight different languages this year. This is a wonderful reminder that music, like Linacre itself, thrives on diversity. In rehearsing and performing, students learn about each other’s cultures, perspectives, and passions. It is collaboration in its truest form. Music, much like rowing, builds trust and friendship in ways that words alone often can’t.

What ties sport and music together is the sense of shared endeavour. Whether it is a 6am rowing outing in the mist or a late-night rehearsal chasing the perfect harmony, these experiences teach our students that they are part of something bigger than themselves. They learn ambition, empathy, and the sheer joy of striving for excellence side by side.

At a time when the world can feel increasingly fragmented, and digital life often replaces real connection, these communities of practice offer the chance to belong. That’s why Linacre continues to champion sport and music, not as optional extras, but as integral to our mission of fostering a compassionate, inclusive academic environment.

In every stroke of the oar and every note of a shared song, Linacre’s community spirit is alive and well. And for those of us lucky enough to be part of it, past or present, it is a powerful reminder of what this College is truly about.

Nick Leimu-Brown Principal

In its second year of operation, Linacre’s Board of Trustees has moved from formation to focus. Having built a strong foundation for good governance, the Board is now putting its energy into what matters most: helping Linacre flourish—not just financially or structurally, but intellectually, culturally and sustainably. In this article the Chair, Femi Macaulay, shares an update from the Board.

Over the past 12 months, the Board has worked across a broad canvas: refining policy, strengthening oversight, and supporting strategic projects. The common thread through all of it has been our desire to serve Linacre’s mission with integrity and ambition.

From Vision to Strategy—A Shared Endeavour

One of the clearest messages to emerge this year—both from our meetings and from the confidential self-review survey taken by our Trustees—is the importance of a robust, well-defined strategic plan to the Board's work. Trustees strongly endorsed the need for such a framework: not as a bureaucratic exercise, but as a vital tool for aligning decisions with the College’s long-term ambitions.

To that end, we are working closely and collaboratively with the Senior Management Team to convert Linacre’s Strategic Vision into a focused, viable and financially grounded plan. This includes identifying what success looks like under our four core themes— Student Experience, Accessibility

and Diversity, People, and Environmental Sustainability—and setting clear priorities over a 3–5 year horizon.

This work is not just about what Linacre wants to achieve, but how we make trade-offs, allocate limited resources, and remain agile in an increasingly uncertain external environment. It is, in the best sense, a shared endeavour—one that will serve the College for years to come. I look forward to sharing the updated Strategic Vision with our alumni community and on the College website next year.

Investing in People and Place 2024–25 has seen important developments across the Linacre estate. Building on the successful reopening of the Bamborough Building, we approved a major refurbishment and extension of 189 Iffley Road to create additional Junior Research Fellow (JRF) accommodation and improve existing student accommodation. This project, funded through a generous legacy received from the late Professor Whelan, exemplifies how philanthropy and strategy

can intersect to enhance College life and support our academic community.

The Board also endorsed the acquisition of a property on the Iffley Road to further expand our accommodation offering for early-

career researchers. Both decisions were made in alignment with our sustainability goals, and as part of a broader effort to enhance the quality, efficiency and inclusivity of College facilities.

Meanwhile, the College’s ambitious decarbonisation programme continues to gain ground. We were pleased to see the completion of retrofitting across several off-site buildings and look forward to progress on the next phase of this estate-wide transformation.

Linacre continues to perform well financially in what remains a highly challenging environment for higher education. Despite inflationary pressures and staffing cost increases, the College reported an operating surplus—driven in part by strong performance from catering, return on endowment and income from subsidiary activities. The Board has kept a close eye on financial sustainability, risk, and regulatory compliance. Over the year, we ratified updated policies on financial crime, safeguarding, and gift acceptance, while also supporting improvements to the College’s risk register methodology.

These changes might not make headlines—but they matter deeply. They signal a governance culture that is thoughtful, disciplined, and committed to long-term stewardship.

In May, we invited all Trustees to take part in a confidential self-review survey to assess how well the Board is working. The feedback was encouraging. The survey surfaced a hunger for more: more time to engage with

strategic issues, more opportunity for informal collaboration with the SMT and Governing Body, and more structured involvement with students and frontline staff. These are not weaknesses—they are signs of a Board that is learning, listening, and committed to continuous improvement.

Throughout our work, we have remained focused on what matters most: the student experience. Whether reviewing admissions data, discussing accommodation needs, or evaluating philanthropic opportunities, we have consistently asked, “How does this improve life for our students?”

Encouragingly, Linacre continues to attract a growing number of applicants who list it as their firstchoice college—particularly in the Medical Sciences. This suggests that our reputation for inclusivity, internationalism and academic rigour is cutting through.

We are also thinking carefully about how we support students at risk of hardship, particularly as cost-of-

living pressures continue to bite. This will remain a focus for us in the year ahead.

The next 12–18 months will be an exciting time. We aim to finalise the strategic plan, complete the next phase of estate improvements, and deepen our understanding of how to balance competing priorities— from sustainability to staffing, from academic excellence to financial resilience.

We will also continue to explore how best to engage with the wider Linacre community: students, staff, fellows and alumni. As Trustees, we are stewards of a mission that transcends any one moment, person or project.

It is a privilege to do this work. And as our survey responses made clear, this Board is not only committed to helping Linacre thrive—it is energised, thoughtful, and ready to lead.

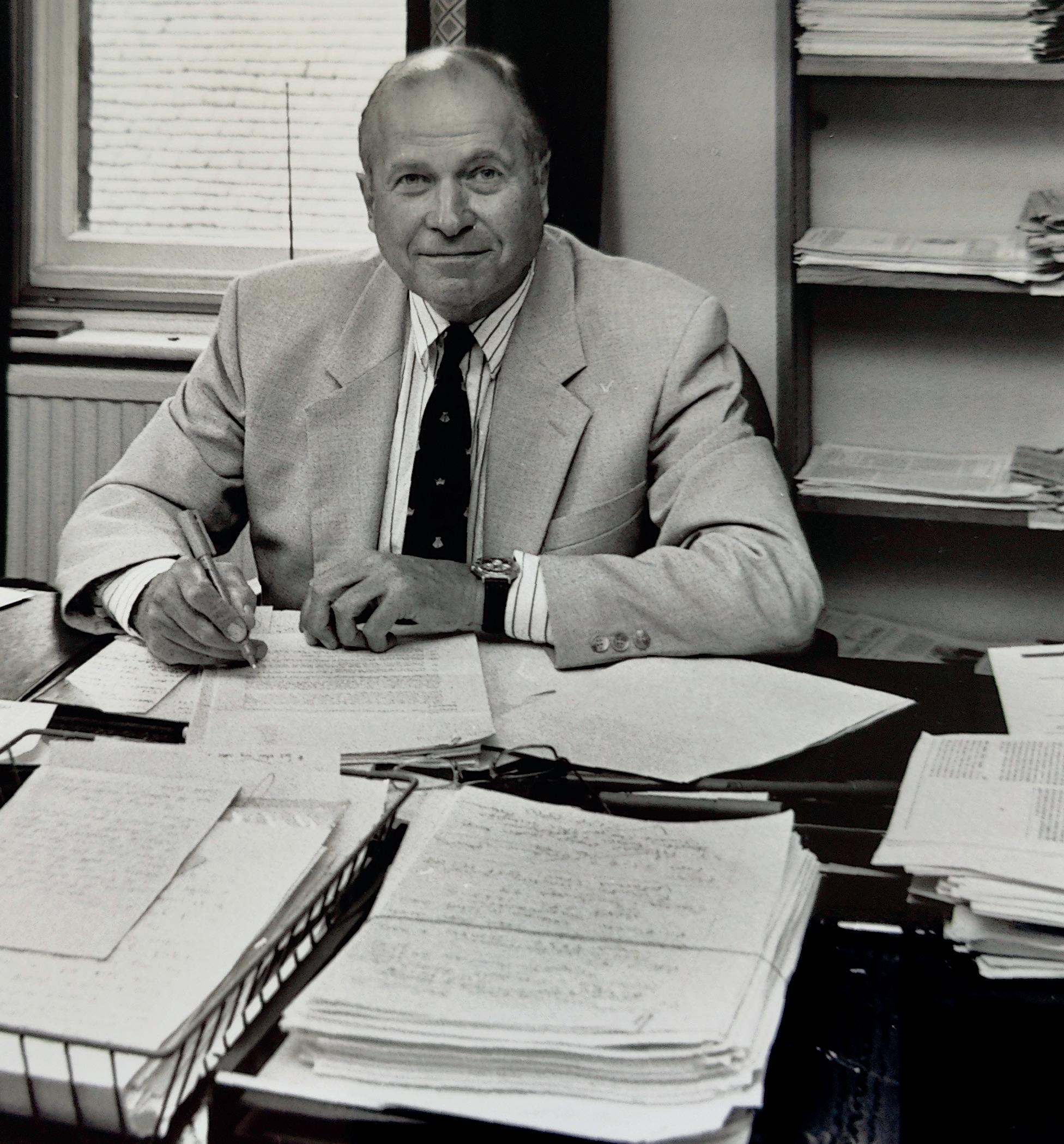

By Femi Macaulay (1983) Chair of the Board of Trustees (pictured

above with the Principal)

The Boat Club has enjoyed a stellar year. Women's Co-Captain, Sophie Kubik, shares below an update from the LBC Committee, which is led by Co-Presidents Tom Ginnis and Tom Underwood, Women’s Co-Captains Emily Stone and Sophie Kubik; and Men’s Captain Elias Drost and Vice-Captain Manny Djanga.

The committee is incredibly pleased with the past year, which saw an increase in membership from our partner college Nuffield and a strong sense of support from both college communities. The highlight of the year was our W1 winning blades at Summer Eights and finishing 14th on the river in the Linacre Women’s highest finish since 1983!

Michaelmas Term as usual started with rain, rain, and more rain, but we were happy to recruit a keen crop of novices whose hobbies include marathon running, fencing, kickboxing, sailing, Ironman, cycling, football and cricket. Quickly hooked on rowing (even on the ergs), every novice got bumps racing experience by the end of the season!

The women also took a trip to the Head of Prague in November, courtesy of our remarkably large Czech membership, a tradition we hope to continue in years to come.

In Hilary Term, W1 and M1 took to the river for the 169th Torpids, which were limited to fixed divisions due to rain. The women were bumped by a rapid (and ultimately blades-winning) Merton on day one, but proceeded to bump Corpus Christi, St. Anne’s, and Wolfson II in the coming days, culminating in +2 for the week. The men’s side put on a record-setting spoons performance, going -11 over the four days, and are looking forward to a meteoric rise next year.

In the Easter Vacation the team went to Bayonne, France, for our annual training camp with the Société Nautique de Bayonne. The sunshine and gorgeous River Adour made up for winter rowing and everyone came away fitter, faster and stronger for Eights.

The 202nd Summer Eights did not disappoint with gritty performances from all four crews and 13 nationalities represented within the Linacre boats. M1 and M2 were happy to improve on their Torpids

performance with each crew falling 3 places in the week. W2 showed their stamina, being bumped by Wadham II on day one and then rowing over, chasing an elusive Magdalen II, on days two, three and four. We are proud of their fight (and fitness!) and are hungry for Magdalen’s stern in 2026.

W1 bumped Exeter along the Greenbank on day one, avenging Exeter’s day four bump on Linacre last year. Day two saw a bump just after Donnington Bridge (in about 30 strokes, per the cox orb) on a rapidly falling St. Anne’s, which was good, because the team needed all their strength for a hard-fought day three bump on Green Templeton along Boathouse Island. Coming into day four with blades on the mind, W1 gave it everything off the start to bump Jesus in the Gut and, it is rumoured, hit a 1:29/500 split along the way.

The team celebrated with a wonderful Eights Dinner at Vincent’s Club!

The Centre for Eudaimonia and Human Flourishing is housed in the magnificent Stoke House in Old Headington. Professor Morten L Kringelbach, Linacre Fellow and Director of the Centre, leads an interdisciplinary team of around twenty researchers and artistsin-residence who are conducting research into the roots of flourishing and how they are affected in health and disease.

Over the last four years, the research output of the Centre has been prolific, with around 30 peer-reviewed articles per year published in high-impact journals such as Nature Human Behaviour, Science Advances, PNAS, Nature Communications and Nature Reviews Neuroscience. During term time, the Centre hosts a weekly hybrid seminar series open to the public. This series has attracted some excellent speakers, and the talks are available at linacre.ox.ac. uk/about/centre-for-eudaimoniahuman-flourishing

The Cillo Foundation has recently provided significant philanthropic funding for a new programme within the Centre, which will build on existing research to investigate how rapid advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) will impact human flourishing. The Centre will address several critical questions, including

whether AI will be used for good or bad, whether it will serve humanity or work against it, and whether we will retain control over AI or whether it will control us.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of these questions, the Programme will engage researchers from a wide range of academic disciplines. Its research will focus on three core building blocks: the organism, encompassing biology and brain science; the connective tissue, involving brain-computer interfaces; and the synthetic system, which includes physics and artificial intelligence. In time, this work will hopefully contribute to a more meaningful co-existence with AI.

An important aspiration for the Centre is to include nature in its core mission. After all, how is human flourishing possible without nature? Each year on June 21st,

the Centre hosts a summer solstice celebration for Linacre members— alumni warmly welcomed— featuring singing and dancing from the College choir.

The Centre also engages with local environmental issues essential to flourishing. Oxford is at the confluence of at least seven rivers and historically commerce has flowed down these rivers , but now our waterways are threatened by the appalling pollution of raw sewage. Last year, the Centre participated in the Nature Based Solutions Conference at the Oxford Natural History Museum, designed to bring about local and global change. Sacred water was needed for the opening of the conference and, led by Chris Park, a renowned local storyteller and beekeeper, members of the Centre undertook a water pilgrimage from St. Margaret's Well in Binsey.

This year, MSt Music (Musicology) student Sam Kail-Dyke (2024), formed the first Oxford Postgraduate Orchestra which is based at Linacre. In this article, he reflects on his inspiration for creating the Orchestra and the success of its inaugural year.

I caught the bug for conducting during my undergraduate studies and once I knew that I was coming to Oxford for my master's degree, I was keen to keep developing the skill. Since I was only going to be in Oxford for one year, finding an existing ensemble to conduct would be tricky, so it seemed only logical to start something myself. Discovering that I would be coming to Linacre helped me spot the ‘gap in the market’ for postgraduate-exclusive music making opportunities.

When forming the orchestra, I was keen to build something that I would want to be part of myself. For me, this meant performing canonical orchestral repertoire, in full, and to a high standard, whilst being open to all without the need for auditions. This is exactly what we have been able to achieve, and I hope that these qualities have helped us to create a welcoming and exciting space for graduate musicians.

Although the orchestra has only existed for a year, we have been able to perform some fantastic concerts including: collaborations with the English National Ballet and the Parkinson’s charity MuMo; a packed concert in Brasenose College Chapel; and performances at Linacre events, most recently in the College garden with the Linacre Choir. During this performance, as well as showcasing orchestral repertoire such as Fanny Mendelssohn’s ‘Overture in C’ and Beethoven’s 'Symphony No. 1', we had the incredible experience of performing Ralph Vaughan Williams’ ‘An Oxford Elegy’. This rarely performed piece is an evocative reflection of Oxford written for orchestra, choir, and narrator, and sets the texts of Matthew Arnold’s ‘The Scholar Gipsy’, and ‘Thyrsis’ to music. It was no small undertaking but led to an exceptional performance that provided a wonderful conclusion to the academic year.

I am very proud of what we have been able to achieve with the orchestra this year. Not only for the concerts we have performed, but also for the wonderful community of postgraduate musicians we have been able to develop. The orchestra has encouraged several members to pick up their instruments following a hiatus during their studies. Personally, this is one of the things I have been most proud of - it has been fantastic to see members rediscover musicmaking and find the orchestra a weekly oasis in their busy academic schedules. Forming an orchestra is not a one-man job and I have been grateful to receive a huge amount of support from the College. Particular thanks must go to the Senior Tutor, Jane Hoverd, and to the Principal for all that they have both done to make the orchestra a success. The opportunity to create Oxford's first postgraduate orchestra at Linacre has undoubtedly been the jewel in the crown of my Oxford experience.

The Welfare Lead is a new role at Linacre and Melissa Cross has been in post since September 2024. Melissa is a professionally qualified social worker and her background means that she has supported individuals during their most vulnerable and desperate times. She sees this as a privilege. In this article, Melissa reflects on her first year helping students 'over the line' at Linacre.

The smiles, high fives, and triumphant “we got there” moments were a defining part of this summer’s degree celebrations and leavers’ dinners. It was my first time reaching the end of the journey with Linacre students whom I have supported throughout the year. Standing alongside them and their families was more meaningful than I could have imagined.

Throughout my career in social work, I have supported unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and their families in accessing essential resources such as shelter, clothing, food, and education. I have worked closely

with young people navigating life in care, as well as individuals facing complex challenges related to mental health, substance use, exploitation, violence, and homelessness. From managing a large social work team, I know that three in five people experiencing homelessness have been in care. Of those, only 13% progress to university—and among them, dropout rates are twice as high, with a fivefold increase in the likelihood of attempting suicide in adulthood. I have always practised (beware therapy speak) motivational, strengths-based, solutions-focused, traumainformed and relationship-based techniques to help people believe

that they could change the narrative and defy the statistics.

My work at Linacre

This year, the College has allowed me to take a creative and proactive approach in my role as Welfare Lead at Linacre. I have engaged with over 400 students—many of whom are international and adjusting to life in the UK for the first time. I have offered a friendly face and a consistent source of guidance, empathy, and practical help, regardless of the scale of the issue.

I have refreshed our information delivery to include accessible audio and visual formats for incoming students, and proactively

reached out to those identifying as needing support, helping them navigate their Oxford experience with confidence. As a friendly, chatty Australian, I have practiced relationship-based support—being visible, creative, patient and observant. I have named and shamed imposter syndrome to reduce the pressure of perfectionism and to promote open dialogue. I also co-led a pilot initiative with Iffley Sports and the University Counselling Service, integrating exercise, coaching, and mentoring to enhance student mood, motivation, and resilience.

Tailored support strategies have included:

• One-on-one gym sessions and gardening

• Walks in the University Parks to encourage gentle engagement

• Care packages during highpressure periods

• Interview preparation and coaching for life beyond Oxford

• Promoting rest to prevent burnout

• Signposting to specialist services

The true measure of impact lies in the individual stories: the student whom I helped access adult mental health services, the individual I worked with to overcome panic attacks, the one who I supported through the grief of losing a parent, or the student who had been unable to submit their work due to overwhelm.

The feedback that I have received so far has been positive and while some universities struggle to respond to student crisis, Linacre remains calm. We have committed to proactive, personalised support and I hope to have fostered a safe, connected community where wellbeing is openly discussed.

How you can help

Our Welfare Lead, Melissa Cross, would love to hear from any members of our alumni community who would like to mentor current students or early career researchers.

Wise words and encouragement from those who have already trodden the often-bumpy, academic path at the University of Oxford, could be invaluable in helping future students 'over the line'.

You can contact Melissa by emailing: welfare@linacre.ox.ac.uk

Sophie

Kubik will receive her MPhil in Political Theory from Linacre in 2025. Earlier this year,

she was awarded the Busuttil Domus Prize for research in Business, Criminology, Government, International Relations, Law or Politics. In this article she shares her research which explores the nature and function of equality as a political and social concept.

If one were to google Linacre College, the first thing you would find is: “Linacre College offers a stimulating and supportive graduate community which is rich in diversity and egalitarian in its ethos.” I happen to agree with this statement, and I admire Linacre (and our alumni community) for their tireless pursuit of equality within and beyond the walls of the College. But while equality is something which almost everyone wants, it is very hard to figure out what it actually is.

Mathematically, equality is a relationship between identical figures: i = i. Legally, most countries have instituted some sort of equal rights into their political systems, and we operate on the general belief that our politics should reflect the moral conviction that all human beings are created equal. The problem, these days, seems to lie in our social lives. Demands for social equality stand at the forefront of activist movements today, and they seem as fundamental to the pursuit of justice as they are difficult to concretely capture and achieve –which is why, while both moral and legal equality now seem relatively uncontroversial, social equality stands firmly on the agenda of the 21st century.

In my research, I attempt to capture the concept of social equality by engaging with the work of 20th century political theorist Hannah

Arendt (1906-1975). This involves two claims. The first, with Arendt, is that we should think of equality not as an assumed moral value or underlying legal condition, but as an active commitment that we must make and renew every day. The second, against Arendt, is that equality should be pursued and theorised about primarily in the social, rather than the political sphere. Of course, society and politics bleed into one another. So, part of the challenge and importance of this project is to understand the relationship between society and politics, and how political equality is now largely achieved while social equality continues to elude us.

In her famous 1951 book 'The Origins of Totalitarianism,' Arendt rejected the idea that equality can be assumed to stem from inborn moral worth. She declared instead that: Equality […] is not given us, but is the result of human organisation insofar as it is guided by the principle of justice. We are not born equal; we become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights. (301)

This commitment approach is how I argue we – as theorists and as people – should think about equality. By reminding ourselves that we must actively commit to equality, and to renew this

commitment every day, Arendt shows us a way to escape the complacency with which we accept claims to ‘natural’ human equality but fail entirely to make them a reality. She shows us that the egalitarian ethos must be cultivated, rather than assumed. Yet, in this quote, Arendt seems to argue that this egalitarian commitment is purely political, made real only through equal rights under the law, a perspective unhelpful to our modern struggle for social equality which goes beyond the law. So, there is more to be done to excavate a conception of social equality from Arendt’s work.

Arendt’s dependence on legal equality stems from her schematisation of the modern world into three distinct spheres of operation. In 'The Human Condition' (1958) she presented this now-famous political phenomenology. Humans can be found within and between the private sphere, like the family or home, where we are primarily concerned with the differences for which we love each other, rather than what makes us equal; the political sphere, where we create a common world by making laws and setting up institutions to ensure our artificial equality; and the social sphere, which is in public but not explicitly political, and where we in fact spend most of our time.

The social causes us some philosophical problems precisely because it meshes the private and the political – it is the sphere in which we must reckon with private difference and public equality. Therein, we are confronted with people who are very different from us, and yet we must find a way to get along. Arendt worries that this is a difficult balance to strike, and that we are more likely to respond with tribalism and hatred than to find points of commonality. Looking around today, one might worry that she’s right. But I argue that the difficulties raised by the social sphere make it the perfect space in which we should theorise about and strive for equality.

To achieve social equality, then, we need to think through the various group-based identities we hold, like race, gender, and sexuality, but we also need to think about what makes

us unique and what might come through only when we interact with new people in public – perhaps a gift for organisation or a talent for bringing people together. Arendt captures these two sides of our identities by separating between what and who we are. What we are is comprised of naturally given, contingent, or physical factors. This includes things we typically think of as socially salient group identities like race, gender, and sexuality. Who we are is demonstrated through our actions – it includes the principles we commit ourselves to and the ways we interact with the world. Arendt thinks we can only show who we are if we become absolutely free from what we are; we must transcend the what to achieve the who.

For Arendt, the social is a nightmarish place, because in it, we are forced to be both what and

who we are at once. She worries this ends up making us a confused mess, both to ourselves and others. But I think this way of thinking about identity makes a lot of sense as to how we talk about social equality and acceptance today: we want to be recognised for both what and who we are, for the group identities we share with others, but also for our unique talents and oddities. In other words, I argue that social identity can be understood as being composed of both what and who we are. So, Arendt’s description of the social sphere, and her big problem with it, in fact gives us the language we need to clarify what social equality is, and how we might achieve it, in the modern world. Theory may not automatically beget practice, but it can always help to clarify our goals and perhaps even motivate us to pursue them in our everyday lives.

Linacre Fellow, Chris Thorogood is the Deputy Director of Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum. Here he shares his lifelong mission to save the world's largest plants.

When I was a child, I sat crosslegged on my bed poring over old books depicting curious plants in a faraway land. I remember one that contained a black and white photograph of a curious flower growing in the Southeast Asian rainforest. I can still picture it: an astonishingly large, grotesquelooking pentagon, draped over the floor like a starfish. This was the largest flower in the world, the book told me, spanning a metre. I was possessed by it and wanted to see one growing in the wild more than anything. Rafflesia had cast its spell on me.

But Southeast Asia may as well have been the moon to me then. There was no way in which I could see the plant that haunted me from the other side of the globe. So I conjured one up in a pretend rainforest behind our back garden. We lived next to an old cemetery where I scrambled up yew trees and swung from the branches, pretending I was in the jungle. I made a life-sized Rafflesia replica out of papier mâché and clay, then sat on a fallen gravestone in the thicket, staring at it. This was the closest I could get to seeing the world’s largest flower.

Today I am the Deputy Director of Oxford Botanic Garden and

Arboretum, and I have dedicated my life to studying the biology of extraordinary plants such as Rafflesia: revealing their secrets, and trying to find ways to save them from extinction – a threat faced by two in five of the world’s plant species. Most of the 40 species of Rafflesia are threatened, but the plant is challenging to protect: it is almost impossible to grow, and its seeds cannot be banked in a freezer. Not to be confused with the unrelated titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) – a plant sometimes seen in botanic gardens, which possesses a giant structure bearing many small flowers (rather than one large one) – Rafflesia has been grown by almost no one. Rafflesia is a parasitic plant that steals its food from a tropical vine. It spends most of its life cycle within the vine, emerging only to bloom: it is a plant within a plant. These characteristics are what make Rafflesia stubbornly resistant to cultivation.

Besides a handful of places (the most popular being Mount Kinabalu in Borneo), most Rafflesia habitats are deep in rainforests that require special permits to enter and days of trekking to reach. They are all but impossible to see. In 2022, I joined a tribe in a remote rainforest in Kalinga in the Philippines in

pursuit of a particularly rare species of Rafflesia, and the experience was nothing short of lifechanging for me. I was honoured to be the first Westerner to see Rafflesia banoanoa, and only the third botanist. The plant grows deep in a wilderness through which a path must be hacked by machete. By the time I reached the plant, I was leach-stricken and it is no exaggeration to say that I dripped blood, sweat and tears on its flowers.

Last year I joined an expedition to Mount Kemalugong in the Philippines; once again I was told I was the first Westerner to venture up its slopes, and my fellow botanists and I were the first scientists to visit. It was a privilege to have permission to ascend – something I was nearly denied because someone had been shot recently on the mountain. We departed by torchlight at 2 am, hauling ourselves up the steep, deadly snake-infested slope. It was hard work but compensated for by views over the hills in the violet light of dawn – these were simply unforgettable. To our disappointment, when we eventually reached our destination, the Rafflesia species we were in pursuit of was in tight bud. In fact, most of my Rafflesia quests have

ended this way – failure – but this makes the successes even greater.

Today I work with foresters across Southeast Asia to examine and explore ways to protect Rafflesia. In 2022, I received funding to take my colleagues from the Philippines to Indonesia, where together we learnt how to propagate Rafflesia from the only person in the world who knows how: an old man called Mr Ngatari in Bogor Botanic Garden, Indonesia. He has dedicated his life to ‘growing the ungrowable’. Mr Ngatari gave us a private workshop showing us how to graft Rafflesia from an infected vine onto a new root stock. Then we applied what we had learnt from him in Indonesia to the Philippines, where conservation action is needed most. With permits in place, we collected a vine infected with Rafflesia from Mount Makiling in Luzon, and grafted this onto a new (uninfected) one in protected rainforest. This is the first attempt at Rafflesia propagation in the Philippines. My recent book Pathless Forest is all about the adventures on which my colleagues and I embarked to find Rafflesia, and ways to protect it.

Like many botanists, I illustrate plants. Art and science are both lenses through which I make sense of the natural world. Science asks questions: my scientific research probes deep into the lives of plants to find the answers. Art complements the science. I have always painted plants and people. I absorb images in the field and hold onto them; then when I am home I set them free. The medium I choose depends on the subject. My expeditions in pursuit of Rafflesia were captured in graphite. I make sketches in my field diaries; then, when I return to Oxford, I Illustrate them on hardboard.

Through illustration and science writing, I hope to help people see plants. Plants have a tough time when it comes to conservation: most people don’t see them; or at least not like animals – a phenomenon known metaphorically as ‘plant blindness’. We are simply better attuned to seeing other animals, which we evolved to hunt and flee. We live in a time of unprecedented global challenges to which plants hold many of the solutions, from food security and medicine to carbon capture: we cannot afford to ignore them. Through writing I seek to portray plants differently: for them to push up against the margins of convention; and show how they are vital for our own future as for that of the planet we share.

Pictured below - Rafflesia arnoldi, the largest flower in the world. Pictured overleaf - Chris's illustration of the Banao Tribe with Rafflesia banaoana.

Associate Professor Andrew Dansie (2012) is the Academic Lead of Humanitarian Engineering at the University of New South Wales, a 'Category A – World Class Expert’ with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, and Board Member of the Australia Africa Universities Network. He was a Clarendon Scholar during his DPhil in Geography and the Environment at Linacre. Here he shares his mission to strive for equity in opportunity and access to resources, providing examples of current projects in Uganda and Fiji.

I vividly remember the day I received my offer to undertake a DPhil at the University of Oxford. Linacre College was my first choice of College, a choice made because of the environmental credentials and focus of the College, the fact I knew some current and past Linacrites who spoke so highly of it, and its egalitarian structure and ethos. Perhaps I would also meet some like-minded individuals while I was there? When I received the offer, I was a Research Fellow at the United Nations University and had reached a point in my career where I could either go down the management path or a sciencebased problem solving path, which required a PhD in the UN System before going any further.

I was always fascinated with biology, animals, and plants, and had realised that to successfully protect nature and biodiversity any approach had to be done in partnership with, and in consideration of, humans. We are now over 8 billion people on the planet, having roughly quadrupled our global population since the end of WWII. This is a tremendous increase in 80 years which is thanks to medical and technological advances but comes at the expense

of the environment and any semblance of the sustainable use of the planet’s natural resources. With the global population forecast to plateau in 2100 somewhere between 10-11 billion people, the need to operate sustainably within out planetary boundaries will require us to do more with less in terms of resources. This is going to require innovation, collaboration, and equity in opportunities.

Moving back into academia for my DPhil provided me with a reminder of the joy and challenges of real field-based research plus a taste of teaching to undergraduate and masters students. This made universities an attractive place to not only implement on-the-ground change but to engage with the incoming generations of students who bring passion and new ideas. I now combine my multilateral institution experience and academic training as an Associate Professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Academic Lead for Humanitarian Engineering at UNSW.

What this means from a research perspective is that I get to work with amazing and inspiring in-country partners on providing sustainable

and appropriate solutions to challenges faced by disadvantaged people and communities. Importantly, this disadvantaged state almost always comes from negative impacts occurring from factors outside of one’s control. I would like to share two examples of the work I am doing; working on the provision of safe drinking water for primary school children in Uganda, and developing mangrove-based nature-based solutions in Fiji.

Drinking water in Uganda

Access to safely managed drinking water is lacking for 2.2 billion people and while progress is being made, it is not enough to reach the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 targets by 2030. Innovation is needed. With much of the population growth between now and 2100 to occur across Africa, opportunity to develop new solutions for safe drinking water has tremendous chance for impact.

In rural areas, decentralised approaches that utilise solar power and do not need a constant supply of consumables offer many advantages. Working with Gulu University and the Africa STEM Education Initiative (ASEI) since 2020, we have developed

a point-of-use water treatment system which applies ultraviolet c-wavelength (UV-C) light to remove harmful microbes when the tap is turned on. At one of the pilot sites, Hilder Primary School, a school of 1,400 boarding and day students in northern Uganda, the students had to collect firewood to boil their water every day. The UV-C system designed and built in collaboration between Gulu University, ASEI, and UNSW now provides safe drinking water without the negative health impacts on students from smoke and environmental impacts from constant wood gathering. Typhoid cases amongst students at the school have dropped from 30 per term to 3 on average, with the remaining three cases being foodborne. The collaboration is now seeing demand for additional sites and ongoing water quality testing is underway to ensure the reliability of the system before securing funding for scale-up activities.

The Pacific is unfairly impacted by anthropogenic climate change and not on track to achieve any of the 17 UN SDGs by 2030. Innovation and research is needed to improve the progress and address critical

issues such as water, energy, and food security. I co-lead a Project Halo, a multi-year, multi-beneficiary, multi-million dollar project that began in 2024. Supported by Swire Shipping and in partnership with the University of the South Pacific and regional and international multilateral partners, Project Halo is undertaking large-scale rejuvenation of degraded coastal lands and integrating mangroves into highly urbanised coastlines through mangrove-integrated coastal infrastructure. The research team comprises twelve PhD students and academic specialists in both Fiji and Australia. This approach is supporting the next generation of science-based problem solvers and echoing the high ambition of the Pacific to do more and be better with regards to climate change. The opportunity to invest in the environment and measure the additional societal and economic benefits offers an off-ramp from the business as usual approach and instead provides both coastal protection and support for livelihoods connected to the land and traditions. With many universities currently considering their role in the world, we are seeing increased deliberation on what ‘impact’ is. A move towards

recognising ‘societal impact’ is heartening to see across many institutions. While harder to measure compared to traditional citationbased metrics of academic impact, this recognition is essential if we are to support the innovation and collaboration needed to get to the best version of 2100 that we can hope for. It is essential that equity in opportunity and access to resources is improved to allow more people to achieve their desired potential and lead safe and fulfilling lives.

On my end, not only did I meet many people at Linacre that are now life-long friends, I met my wife and we live amongst the trees on the outskirts of Sydney, retaining that connection to nature, with three young boys. These boys will, according to Australia’s average life expectancy, see what world we have created in 2100 but many other children the same age will not, purely because of where they are born. This must change.

Dr. Sajda van der Leeuw (2015) is a lecturer in Modern & Contemporary Art in the department of History of Art at Utrecht University. She is an art historian and philosopher, with a DPhil in History of Art, and a proud alumna of Linacre. Here she shares her research in the relationship between art and the natural world.

The paradigm of this mutual overlap is [therefore] what the ancients called “breath” (pneuma). … [T]o breathe –means in fact to have this experience: what contains us, the air becomes contained in us; and conversely, what was contained in us becomes what contains us.

- Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture (2018), pp. 10-11.

We often forget that we are breathing, continuously – even right now, while reading this text. But the question that sometimes arises, when one becomes aware of one's breathing is: am I sure that it is ‘I’ who breathes? I cannot stop breathing by myself, I cannot will myself not to breathe – so is the breath mine? Or is it given to me –does it only go through me? Am I, in fact, ‘being breathed’, in some way, by life, by the atmosphere of the Earth that I inhabit? Indeed, many indigenous people believe that the breath is not something human: it is spirit, something much bigger than

our individual lives – something that connects all life. Chief Seattle once said: “… [A]ll things share the same breath – the beast, the tree, the man. The air shares its spirit with all the life it supports.” He also warned the ‘white man’ that he was not the creator of this “web of life. He is merely a strand of it. What ever he does to the web, he does to himself.”

Since the turn of the millennium, many scholars have labelled the current geological epoch as the Anthropocene: an era in which humankind's very presence has the potential to destroy most of the Earth’s biosphere (and with it, ourselves plus most animal and plant life). The use of this term leads to a very human-centric view of the future of Earth: either humankind destroys, or ‘saves’ the planet. While the first is the perspective we are currently facing with our climate emergency, the second is – as most things that are simply negated – not much better. ‘Saving

the Earth’ is a reflection of the idea that we are, indeed, able to do so. That we and only we – as humans –have the power to do so. Yet slowly a movement gains strength in which it is believed that what really is needed is a change of perspective altogether: from the human-centric view to a non-humancentric view. In the latter view, the ‘more than humans’ – bacterial, animal, and plant life – are the ones who really have the power to save the Earth. Interestingly, our culture in which the Selfie seems to have become the most popular art form, seems to be unable to imagine what a nonhumancentric view of life would look like. Yet art can give us some insight into this. In an article for The Guardian (12 December 2019) about the Lascaux paintings in the south of France, Barbara Ehrenreich asks the question “why nobody has asked the question” that these murals portray only animals, geometric shapes, and hand prints, but no humans with a face. After all, Ehrenreich points out, “The non-

human animals are painted with almost supernatural attention to facial and muscular detail, but […] the humanoids painted on cave walls have no faces. [They appear like] bipedal stick figures that can sometimes be found on the margins of the panels containing animal shapes.” The interesting answer she gives to this question comes from the paleoarchaeologist Jean Clottes, who writes in his book 'What Is Paleolithic Art?': “The essential role played by animals evidently explains the small number of representations of human beings. In the Paleolithic world, humans were not at the centre of the stage.”

It is difficult for us, humans, to imagine a world where we are not at the centre of the stage. From Instagram to the daily news: we are fascinated by our human presence and actions. Yet in the history of art we find some traces of what it means to experience a presence that is not so ego-centered: more focused on nature, animals and plants. There is a long history in which art’s main focus is nature, yet when I started my studies in the History of Art, I was especially drawn towards Land Art (also often called Eco Art, or Earth Art). Land Art is a relatively recent movement, starting in the 1960s, of artists who are working in, with, and for nature. When I started my research about Land Art, first as an undergraduate student and later as part of my DPhil research at Linacre, it dawned on me that many of our contemporary shortsightedness about our relationship to our planet is literally connected to viewing. Indeed, it was and is my belief that the climate emergency is also the result of a visual crisis: the inability to visualize the longterm consequences of our actions (i.e. those resulting from glacial ice melt, biodiversity loss, global warming, or desertification, etc.).

This is why contemporary art has become a key player in affecting, visualizing, and even changing people’s behavior – with the potential to evoke a progressive shift in our relationship towards our planet longer term.

One example of contemporary art in helping us humans with visualising and (as Bruno Latour calls it) sensitising, is Olafur Eliasson’s work Ice Watch, which was installed a few times anew at different locations, but in 2018 in front of the Tate Modern in London. The installation consisted of large blocks of glacial ice from the waters surrounding Greenland, coming from the nearby glacier melting at high speed. This work of art serves as a starting point to talk, sense, and actually see the climate emergency: not only to reflect on our waste of time while talking about it without coming to concrete solutions and actions, but also by hearing and seeing the melting of the 850 year-old blocks of ice used in Eliasson’s artwork over just a few days while they were being ‘exhibited’. With the melting of the glaciers, the centuries of time they symbolise – like a very old tree that is cut and used for its wood – are lost, too. While melting, observers could hear the air bubbles within there for hundreds of years, popping open and finally joining the atmosphere again – invisible, yet breathed in through the many lungs of the visitors present at the time. Imagine a work of art or heritage that is 850 years old, for example the Bayeux Tapestry or the Notre Dame Cathedral, being destroyed before our eyes within the next few days. The sense of loss, the direct acknowledgment of historical and cultural value gone, would strike us deep and keep us enthralled throughout the process. Eliasson’s Ice Watch shows us something similar, and makes us

the direct witness (not just seeing it far-off, on a photograph or on television) of such a destruction due to the climate emergency. As the artist said himself about this installation: “Put your hands on the ice, listen to it, smell it, look at it –and witness the ecological changes our world is undergoing.”

In the face of an ecological crisis, can artists contribute to a progressive shift in how we (re-) envision the complex interrelatedness of the violation of nature and our human habits and wastefulness? Can environmental artworks affect environmental attitudes, perceptions, beliefs, and unethical behaviour towards nature? In the age of the Anthropocene, where the selfie is the most looked at every day, it might be that we now need art to connect us to nature – to restore our own nature back to us. For it is only by finding back ourselves as nature, that we might recover the inherent responsibility of humanity as caretakers of the Earth in a more humble way, stop our eco-violence, and start co-existing again with all other lifeforms: to learn again how we cannot be at the centre of the stage. It is either that, or leaving the

stage empty of our own presence altogether – a future vision that we are currently, blindly, bringing into existence at high speed.

The Common Room has always been the heart of the College. It is where friendships form, societies are launched, and stories are shared over drinks, darts and games of pool. But after decades of loyal service, the space needs an update. While our members remain at the cutting edge of research, the spaces they share have not always kept pace.

We are excited to announce that plans are being drawn for a reimagined Common Room. This is not just a cosmetic upgrade; it is a transformative project that will create a more functional environment to meet the evolving needs of students while also supporting the wider College community. Concept drawings (pictured below and overleaf) envision a more flexible, brighter, and more welcoming space for students, alumni, fellows, and guests. This is not the first time that the Common Room has undergone

a major refurbishment. Delving into the archives, we found a wonderful description in Linacre News from the Domestic Bursar, Russell Read, about why renovation works were also required in 1998:

"The bar was far too small; it was the wrong shape and faced the wrong way. The beer tended to be on the warm side. People kept falling off the bar stools because they were falling apart. Hands could be squeezed through dilapidated ‘security’ shutters to extract the odd bottle of scotch and the locks were a bit suspect too. Draught lager went off in the summer (as did Bar Secretaries, some never to be seen again!)”

While the stools are hopefully less hazardous, the décor is now

outdated and the space, dominated by a dark wooden bar, is limited in its flexibility and its broader appeal. Beyond its tired aesthetic, the room

contains ageing infrastructure and outdated wiring that urgently needs attention.

The College warmly invites our alumni community to be part of an exciting new chapter for the Common Room. The revitalised space offers a range of recognition and naming opportunities, and

every contribution—large or small— will help create a lasting legacy for generations of Linacrites to come. We recently asked members to share their memories of the Common Room and have thoroughly enjoyed reading the stories submitted so far. If you would like to contribute your reflections of this space, please visit the ‘Common Room Refurbishment’ page on our website and complete the online form.

"Watching the 1994 Football World Cup and suffering (with the other Italians) through the loss of Italy in the final at penalties. Drinking gallons of (bad, sorry) coffee after lunch while having amazing conversations with other members of College (including at the time Fellow, now Principal, Nick Leimu-Brown.) For two years, it was my home away from home!"

Marco Trombetta (1993)

“I performed at my first ever open mic night at Linacre and I appreciated the welcoming environment that gave me the courage to get on 'stage'!"

Julianne (2014)

"After nearly every meal in the Dining Hall, I’d go up to the Common Room, have some tea from the trolley, and settle in for a chat with whoever was there. We’d stay up 'til closing over pints of Becks, laughing and joking and making new friends. The Common Room was the beating heart of the community and I hope it remains so for generations of Linacrites to come!"

Marie Keil (2014)

Your time at Linacre likely included moments of meaningful connection like the memories that have been shared. The Common Room refurbishment project offers alumni the opportunity to give back by helping shape a space that both supports today’s students and embodies the inclusive environment that we all value.

For further information on how you can help breathe new life into the Common Room and create a more functional and inspiring hub for our community, scan the QR code or visit the Common Room webpage below.

The Common Room, pictured in 1987

The Linacre Lecture Series is a high-profile public lecture series, rooted in an ethos of interdisciplinary research. Hosted by Linacre College since 1991, a long list of leading academics from around the world have been invited to Oxford to share their research with members of the College and the wider University community. This year, the Linacre Lecture Series was hosted and organised by Linacre Fellows Dr Ashley Coutu, Dr Tea Ghigo and Dr Vibe Nielsen.

The lecture series reflected the interdisciplinary backgrounds of the organisers, across anthropology, archaeology, art history, and science: as a Research Curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum, a Lecturer in the History of Art, Materials and Technology at UCL, and a Museum Anthropologist and Researcher at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and the University of Copenhagen, the organisers used the lecture series as an opportunity to delve into the dynamics of cultural communication and explore the unprecedented challenges and opportunities facing museums in a rapidly changing world. Inspired by the interdisciplinary conversations on museums and communication that the organisers have had during their time at Linacre and fuelled by their experiences leading public engagement activities, such as museum tours and exhibitions, the lecture series was born out of a wish to address how museums and other cultural institutions can ensure that their narratives remain relevant and relatable.

The lecture series focused on issues related to the impact of new conservation theories and

practices, including their effects on audience engagement, the practices of decoloniality in museums and the most effective strategies that have emerged from them, as well as questions related to how museums can effectively communicate issues surrounding materials in an increasingly digital environment, harness the potential of AI and technology in cultural communication, and use these tools responsibly. Being highly interdisciplinary in its scope, the series targeted primarily professionals across the Galleries, Libraries and Museums of Oxford and the interdisciplinary academic community at Linacre College. Furthermore, the lectures were livestreamed and internationally advertised to broaden their impact. The organisers wanted to provoke thoughtful reflection on creating interdisciplinary narratives that leverage the full spectrum of tools and strategies available in the modern world to engage museum visitors. The theme of the series resonated with many people within the Linacre community and beyond. The lectures were very well attended online and in-person, even scholars briefly visiting Oxford joined enthusiastically, and the discussions

about cultural communication and the future of museums were lively and thought-provoking.

Starting with two inspiring lectures by Professor Salvador Muñoz Viñas from the Universitat Politècnica de València in Spain and Professor Katrien Keune from the Rijksmuseum and the Universiteit van Amsterdam in the Netherlands, the potential of scientific and ‘technical disciplines’ were discussed in relation to heritage conservation and the ways in which it can be harnessed in museum communication. In his lecture on 'Conservation as Meaning-making and Unmaking', Professor Salvador Muñoz Viñas demonstrated that the conservation of cultural heritage is a captivating and ever-evolving field, which over its two-centuries long history, has undergone significant transformations. Professor Katrien Keune’s lecture on 'Unlocking Art's Wonders: Science as a Bridge to Public Engagement' explored how integrating scientific research into art museums can enhance public engagement and understanding. Drawing on her experiences at the Rijksmuseum, she discussed 'Operation Night Watch', a live, public examination

of Rembrandt’s 'The Night Watch', and Mission Masterpiece, an interactive children’s exhibition on conservation science.

In the third session of the series, the attention was turned to another timely matter within the field of museums: Namely, how museums with so-called ethnographic collections deal with their colonial legacies. To address this issue, two prominent figures within the field of what might be called decolonial museum practice, Professor Wayne Modest, the Director of Content of the Wereldmuseum in the Netherlands, and Professor Laura Van Broekhoven, the Director of the Pitt Rivers Museum, were engaging in a thoughtprovoking conversation, chaired by Dr Vibe Nielsen. Members of the audience eagerly participated in the discussions and contributed to the conversation with questions to the speakers about how the Wereldmuseum and the Pitt Rivers Museum have been dealing with the colonial legacies of their institutions in the past and what challenges lie ahead.

As May turned into June, researchers and curators of the Gardens, Libraries and Museums of Oxford, gathered at Linacre College for the fourth session of the series: a GLAM Round Table Discussion

chaired by Professor Christopher Morton, Deputy Director and Head of Research at the Pitt Rivers Museum and Linacre's VicePrincipal. The Round Table sparked many inspiring conversations and potential future collaborations, as panellists Professor Silke Ackermann, Director of the History of Science Museum, Dr Ricardo Perez de la Fuente from the Natural History Museum, Dr Sarah Edwards from the Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum, Dr Virginia Llado-Buisan from the Bodleian Libraries and Dr Gina Koutsika from the Ashmolean engaged with the audience in a lively debate about how the narratives of the Gardens, Libraries and Museums of Oxford can remain relevant and relatable, in a rapidly changing world.

In the last week of Trinity Term, the series rounded off with two more lectures: In her lecture 'Museums as Spaces of Living Practice: Lessons from MOWAA’s Emergence', Dr Ore Disu, Director of the Museum of West African Art in Benin City, Nigeria, presented how MOWAA is dedicated to the preservation of heritage, the expansion of knowledge and celebration of West African arts and culture. She discussed how the recently opened museum is being developed as a centre of excellence, creating opportunities

for African and Diaspora artists and scholars. The last lecture of the series was given by Dr Matthias Wivel, Head of Research at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark, who presented some of the creative and scholarly choices behind the Michelangelo Imperfect exhibition at the National Gallery of Denmark. In his lecture, 'Beyond the Auratic: Michelangelo Multiplied', he described aspects of the creative collaboration behind the new facsimiles of the Michelangelo Imperfect exhibition, examined its critical reception and suggested possible paths forward.

Dr Ashley Coutu, Dr Tea Ghigo and Dr Vibe Nielsen are very grateful to everyone at Linacre College who supported the making of the series and to their wonderful lineup of speakers, who provided some thought-provoking insights and inspiring conversations on the future of museums. The organisers would like to thank everyone who attended the lectures – from the Linacre community and beyond – and actively engaged in the lively discussions that the series provided.

(Pictured below - Professor Laura Van Broekhoven, Dr Vibe Nielsen, Professor Wayne Modest, Dr Tea Ghigo and Dr Ashley Coutu.)

Linacre's second Principal, Sir Bryan Cartledge, was in post from 1988 until 1996. In this article, he reflects on his time at Linacre and his determination to establish the College as a leader in environmental sustainability.

After a distinguished career in the British Diplomatic Service, which included roles as Private Secretary (overseas affairs) to two British Prime Ministers and culminated in his appointments as Ambassador to Hungary and the Soviet Union, Sir Bryan arrived at Linacre. Upon assuming leadership in 1988, he immediately set about elevating the College’s profile. His strategic efforts to enhance Linacre’s visibility proved to be transformative, ushering in a new era of growth and recognition for the College.

Having seen for himself the devastating effects on Russia of environmental neglect, Sir Bryan was determined to create a profile for Linacre as a leader in environmental sustainability. To further this vision, he established an annual lecture series featuring prominent speakers, including the former Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine. These talks were later published by Oxford University Press, further raising the College’s profile. Sir Bryan remembers, “one of the first lectures was delivered by Sir James Lovelock, the pioneer and 'grand old man' of environmentalism. His exposition

of his 'Gaia theory' of the wholeness of the Earth's environment was persuasive and moving.”

Under Sir Bryan’s guidance, and with the help of an active environmental student group led by Veronica Strang (1989) and Kim Polgreen (1989)—strongly supported by the Domestic Bursar, Russell Read—Linacre also expanded its accommodation with the construction of the Abraham Building, named for Sir Edward Abraham, who was a benefactor to the project. This award-winning structure not only provided muchneeded space but also showcased cutting-edge, environmentally sustainable materials and techniques. Built in 1995 and opened by the Chancellor of the University, Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, in the presence of Sir Edward, the Abraham Building achieved a BREEAM excellent rating, won the Oxfordshire Special Conservation Award 1995 and earned the highly prestigious Green Building of the Year Award 1996. The Prince of Wales, now King Charles III, later visited the Abraham Building beacuse of its green credentials.

Sir Bryan's environmental legacy continues decades later,

with the recent renovation of the Bamborough Building to significantly reduce carbon emissions as well as ambitious plans to decarbonise the entire College estate over coming years. Sir Bryan notes:

"It gives me huge pleasure to watch the progress that Linacre has made, and continues to make under Nick Leimu-Brown's leadership. I am particularly glad that concern for the Earth's environment continues to be a major theme in Linacre's activities; the original series of Linacre Lectures on the environment, in the 1990s, played an important role in putting Linacre on the Oxford, and national, map."

Sir Bryan also encouraged Linacre’s students to establish sports clubs and compete within the collegiate University, with rowing becoming particularly popular. Given Linacre's chronic shortage of funds, Sir Bryan had a hard job persuading the Governing Body to provide £30,000 to pay for new shells to replace the College's single ageing clinker-built craft. It was eventually accepted that a good showing on the river was one of the best ways of establishing Linacre's identity within the University; and

it was noted that applications to Linacre from graduating members of Oxford's undergraduate colleges increased significantly after Linacre's Boat Club made its mark.

Linacre remains closely connected to Sir Bryan and his wife, Lady Helen Cartledge. Sir Bryan is part of a growing group of Linacre community members who have thoughtfully chosen to support the College beyond their lifetimes through a bequest in their Will, ensuring that their legacy will continue to benefit future generations.

“My modest legacy is specifically designated for the relief of student hardship. One of my greatest regrets as Principal was my inability, because of the College's relative poverty at that time, to do more to help students who for one reason or another were in acute financial difficulty. It is important to me to contribute to the alleviation of what is bound to be an ongoing problem.”

Leaving a gift to Linacre in your Will can make a lasting difference to College. Legacy gifts help ensure that future generations of students benefit from the world-leading education and rich opportunities provided here at Linacre and that we continue to be at the cutting edge of research.

Those who inform us of their intention to leave a legacy are warmly invited to join the Bamborough Circle, a special group that recognises the generosity and lasting support given to the College through a gift in your Will.

If you would like to inform us of your legacy intentions or if you are interested in finding out more about leaving a gift in your Will to Linacre, our Legacy and Planned Giving Manager, Verity Armstrong, would be happy to hear from you. Please contact: legacies@linacre.ox.ac.uk Further information can be found at: Linacre.ox.ac.uk/ alumni/wills

David Rogers (2001), MBE, completed an MSc in Software Engineering at Linacre. He is the CEO of Copper Horse and the former Chairman of the global mobile industry's Fraud and Security Group at the GSMA. In In this article, David explores the growing need for responsible security engineering within the modern world.

In 2025, the need for cyber security has never been greater. Great strides have been made in the last fifteen years, particularly led by the UK's National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) whose staff have provided the intellectual leadership needed for pointing policy makers at the solutions for securing the connected world. By providing an underlying 'glue' of technical security expertise to all government departments, the UK has been able to deliver a series of legislation and Codes of Practices, leading to regulatory requirements that are grounded in real-world problems, while providing practical implementation solutions for technology. These measures

have resulted in guidance and legislation being co-opted across the world, with the NCSC model being adopted by many countries. Resiliency is a shared problem.

The challenge now is that the problems have been identified, solutions recommended and mandated, but there is a bottleneck of compliance. Companies that were struggling to get the right people to operationally secure their businesses have too few people to be able to manage compliance to multiple regulatory requirements. In companies operating globally, this is multiplied many times over, with companies operating huge mapping spreadsheets to decipher

and match-up requirements that ask for the same thing in slightly different ways.

Frustratingly, these days from an engineering perspective it isn't a difficult problem to solve. Businesses have long ignored the need to secure the products they sell. The only sector to take leadership on product security was the mobile industry, long under attack from every type of threat actor; standardising and adopting strong security measures from the hardware upwards, providing foundations of trust for the software and applications running on products. The security technology is there; we know what good looks like - it just needs to be adopted across every sector.

For product security particularly - whether it be webcams for consumers, industrial controls for a factory or car electronics, it all boils down to the same thing - software running on chips, placed on a Printed Circuit Board (PCB). The commonality between operating systems and software, communications protocols and hardware platforms means that security vulnerabilities in one type of device in a particular business sector are usually present in other devices, in other sectors. The collective failure to address these issues throughout supply chains

has led to insecurity in businesses across the world. Malicious hackers are able to exploit common vulnerabilities in devices which in some cases have not been patched for many years. This also applies to bad practices - the use of common, default passwords by product vendors is something that has been known about and accepted by everyone (including users) for many years. It was an issue that was being exploited as a system entry point for hackers and automated bots, repeatedly, infamously taking down large parts of the internet due to the 'Mirai' botnet in 2017. Often tagged as 'sophisticated hacks', companies and their suppliers had basically left the keys in the door to their companies - and worryingly still do. This supply chain of product insecurity is also a large part of the issue.

This lag in adoption of security measures puts the secure adoption of new technologies at risk tooand that is if they are developed securely in the first place. The global race to adopt AI in all its forms has led to security and privacy considerations being set aside in favour of rapid innovation. Large Language Models (LLMs) have been pushed in beta form to the general public who have been guinea pigs in the great LLM experiment. Copyright and ownership have been ignored as anything and everything is consumed as training datawhether it is good quality or not. LLMs are currently rotting from within - making their own queries to search engines which in turn return bad answers generated by LLMs. Machines are essentially lying to other machines. They are often presenting false information in such a way that the "real world" is not real. If this trend continues, it has the potential for large-scale human safety issues.

The death spiral of information has begun, but it is not too late to fix it. The bad reputation that LLMs have brought to the domain of AI and machine learning hides some stunning successes where AI has been able to augment and surpass human capabilities. The projects to read the carbonised scrolls at Herculaneum could not have been possible without the aid of computers and machine learning. Pattern matching at scale aids the identification and triaging of cancers. When supervised by a human expert, these tools provide us with super-powers.

In Copper Horse we have been working on the Innovate UK funded Trustable AI Bill of Materials (TAIBOM) project together with the University of Oxford and a group of other companies. Our aim is to provide an open method of assuring and validating that an AI model and its information hasn't been tampered with and is what it purports to be. Our team were

required to build models to apply the TAIBOM and then to attack them. One of the models we built was designed to read 17th century shorthand - particularly that of Thomas Shelton, whose systems were used by notable figures such as Samuel Pepys, Isaac Newton, Thomas Jefferson among many others. This inter-disciplinary use of machine-learning allowed us not just to expand the art of the possible in securing information, but to break new boundaries and provide historians with tools to facilitate their research. It also allowed us to demonstrate the very clear need for institutions to be able to issue authoritative and high-quality datasets that not only assert ownership but that vastly improve future AI models that use them. Adopting solutions such as TAIBOM for information assurance, combined with securing the underlying software and hardware foundations of products that use AI, will provide a much safer and secure future for humanity.

Richard Comont (2009) completed a DPhil in Zoology and now serves as the Science Manager at the Bumblebee Conservation Trust. In this article, he explores the troubling decline of one of the UK's most prolific pollinators.

At times, it can feel like ‘Save the Bees’ has superseded ‘plant a tree’ as the go-to environmental mantra of the 21st century. But which bees? And why? Britain has around 275 species of bee calling the country home and only one of these is the honeybee, while 24 are bumblebees. The remainder are collectively known as ‘solitary bees’ (because they do not live in social colonies). Honeybees tend to get all of the press, but they are essentially livestock (living in hives tended by beekeepers), and they are not actually all that great at pollination. By contrast,

bumblebees are heavyweight pollinators in all senses of the term. They spend most of their waking moments moving from flower to flower, transferring pollen. Due to their size and furriness, bumblebees fly in cool, cloudy weather, when other pollinators are grounded, and their differing tongue lengths and individual preferences mean they visit – and pollinate – a much wider range of plant species than honeybees. These overlooked insects do not just provide the sound of summer with their gentle buzz, they are also key workers in our food chain and wider

ecosystems. But bumblebees are in trouble.

Since the 1930s, agricultural intensification has replaced horsepowered mixed farming with floristically rich hay meadows, rough grazing, and unfarmed areas of steep or stony ground, with simplified, monoculturerich, diesel-powered landscapes. The rise of machinery and the financial imperative to farm every last square inch of land has seen wildlife squeezed out of much of the farmed countryside. More recently, increased pesticide usage and climate change have also degraded the habitat quality of the landscape. Bumblebees’ key requirement is floral continuity –they need flowers to provide the nectar that adult bees feed on and the pollen that they feed to their larvae. And they need that from March, when the queens come out of hibernation and establish nests, until new queens enter hibernation in September. It is not just one or two flowers either. A single nest will contain 50-400 workers at its peak, all foraging less than 1km. A genetically sustainable population needs 30+ nests, close enough to come into contact. Bumblebees need large-scale, well-connected, flower-rich landscapes under good management in order to survive, let alone thrive – they embody

the Lawton principles of 'more, bigger, better, and joined-up' more than perhaps any other insects. In 21st-century Britain, such areas are increasingly hard to find. Two of Britain’s bumblebee species – the Short-haired and Cullum’s bumblebees – became extinct during the last century, and many others have suffered major range contractions.

The Bumblebee Conservation Trust was set up in 2006 to address concerns about ‘the plight of bumblebees’. I joined the organisation in 2013, immediately after completing my DPhil at Linacre, and have led the scientific work of the Trust ever since. One of the main issues of bumblebee conservation was the lack of accurate data illustrating what was actually happening and how climate change was affecting each species. The Trust established a citizen-science-abundancebased monitoring scheme called 'BeeWalk' in 2008 and this has informed the majority of my work. With over a thousand transects walked on a monthly basis across Britain, it is now one of the largest bumblebee sighting datasets worldwide. Long-term, standardised monitoring is how we separate anecdotes from trends, and BeeWalk provides a window into the world of bumblebees that is not provided by any other data. It is tempting to lump all bumblebees in to the same category, but actually each species emerges at a different time, has a different-sized nest, different thermal tolerances, and distinct preferences for foraging, nesting, and overwintering. Consequently, each species reacts individually to changes in climate and habitat, and even to weather from year-to-year. One of the biggest surprises from the BeeWalk dataset is just how contrasting the species are from each other.

2024 was such a bad year for insects that everyone seemed to notice. From the Telegraph to the Guardian to Springwatch, everyone was asking ‘Where are the bees and the butterflies?’ It proved the worst year on record for British bumblebees and numbers were down 22.5% on the long-term average. A cold, wet spring likely hit queens at their most vulnerable when they were searching for suitable nest sites, foraging, incubating their brood and defending a nascent colony, alone. Fewer flowers, less pollen, reduced nectar and increased incubation proved a lethal cocktail for many species and counts of Redtailed and White-tailed bumblebees were down by 74% and 60%, respectively. National monitoring shows that even ‘common’ species are not guaranteed resilience when a bad spring arrives. The 2024 crash is a reminder that a warming, wetter and more erratic climate can turn a slow decline into a step change with little or no warning.

Safeguarding bumblebees does not just help bees, it protects the whole living fabric of the countryside.