Through the Eyes of the Crow AThesisPresented by LilyFillwalk

TotheArtFieldGroupofPitzerCollege Inpartialfulfillmentof

ThedegreeofBachelorofArts

SeniorThesisinStudioArt

Spring,2022

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to my reader, Prof. Tarrah Krajnak, for helping me throughout this thesis and my college art career. Thank you to my parents, John Fillwalk and Eva Zygmunt, for your advice and encouragement. Thank you to Aurora Strauss-Reeves, for being a beautiful model in work throughout my art career and a loving friend. Thank you to my senior seminar group (Jack Contreras, Claire Manning, Olivia Meehan, Max Otake, Julia Stewart, and Zoe Storz) for your constant feedback throughout this year.

Introduction:

The Corvid bird family, including the raven (Corvus corax) and the crow (Corvus), are perceived as one of the world’s most intelligent. From their ability to solve puzzles to their capacity to communicate with others in their species, corvids continue to shock humans with their capabilities.

My initial interest in birds as an artistic subject began while reading an article about changing bird migration patterns due to climate change and increased bird deaths in New York City (Bateman et al., 2020). Birds are experiencing a phenomenon labeled ‘False Spring,’ where temperatures rise at different times due to anthropogenic climate change, causing birds to migrate earlier (Bateman et al., 2020). Along with this, I followed the new policy being created in New York City centered on decreasing light pollution for bird safety (Hoylman, 2022). New York City is experiencing increased bird deaths due to the city's light pollution, causing migrating birds to become disoriented and fly into skyscrapers leading to their death. In the casual observance of weekly ecological news, I realized birds were affected in many ways by the current climate crisis caused by human behavior and wanted to continue this research, which instigated personal mourning in my artwork. I learned about corvid the species by listening to one of my favorite podcasts, “Ologies: with Allie Ward,” in the Fall of 2021. Inspired by the ‘Ologies’ subject matter, I narrowed my research to the corvid bird family. Throughout this thesis, I will be referring to crows when mentioning the species and corvids when mentioning both the crow and raven collectively.

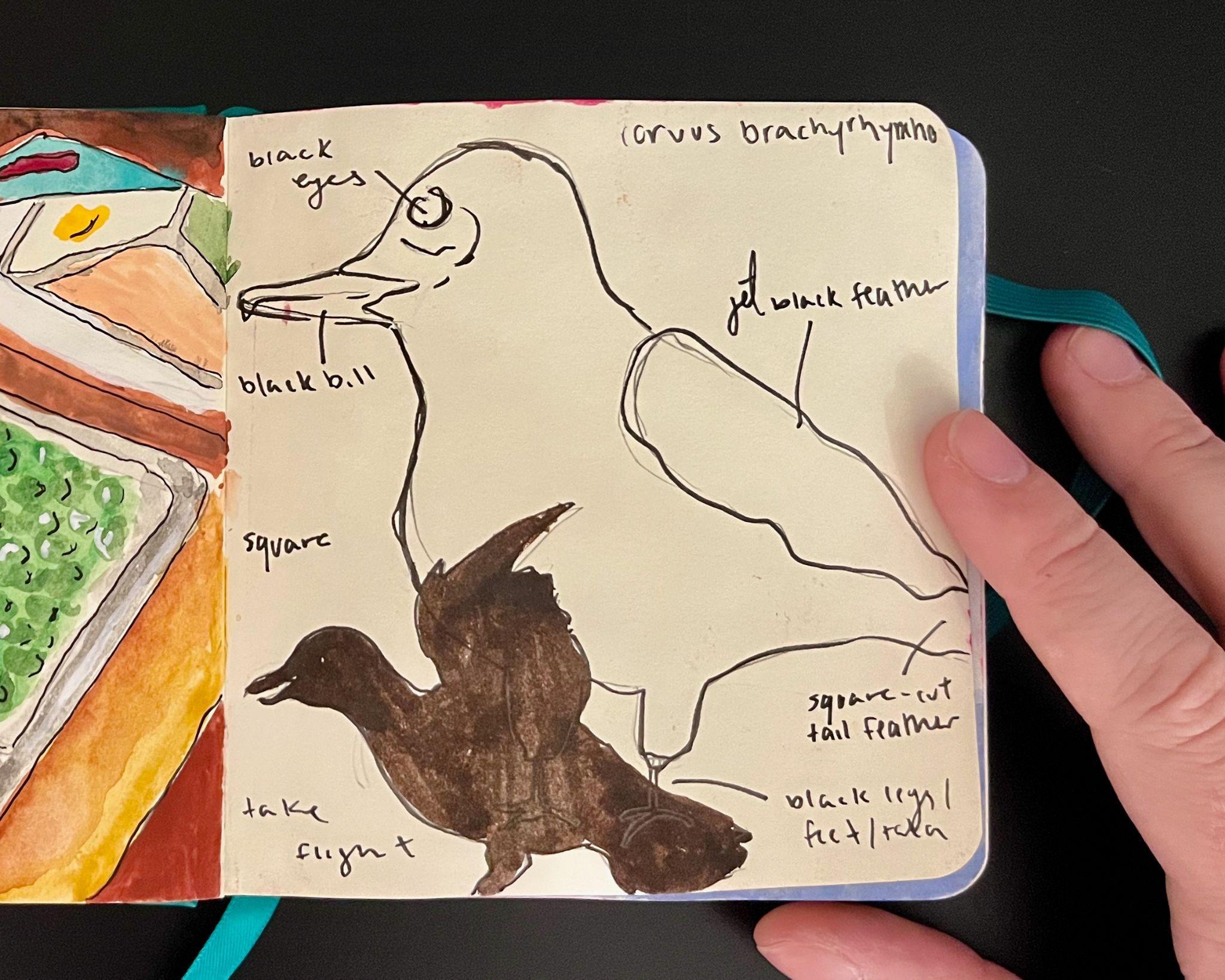

Anthropogenic climate change and related temperature increases have resulted in a surge in the mosquito population, and a subsequent escalation of West Nile Virus, causing a heightened mortality rate among crows (Reiter, 2001; Tam et al., 2016). West Nile virus causes high mortality rates within the crow species (Tam et al., 2016). This phenomenon among the American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) is so widespread that it is often observed as a proxy for the prevalence of the virus in an area (LaDeau et al., 2011). Land use also plays a role in the crow population decline. With a 1% increase in urban land cover, there is around a 5% decline in the (log) of crow abundance (LaDeau et al., 2011). With increasing global urbanization, crow abundance continues to decline. As crow death increases, opportunities for the study of the species’ unique and ceremonial reaction to its respective mortality have heavily influenced the development of my thesis.

The intelligence of the crow has been widely studied, particularly due to its reaction to death among the species. Crows ultimately react to the death of their species with ceremonial mourning in ways such as mobbing around the body, avoidance of place,

procreation, and even necrophilia. This thesis ultimately explores how crows communicate, recognize, and react to the danger in both life and death surrounding the ever-increasing threat of climate change. While this project encompasses how crows perceive and respond to impending threats to their survival, I see this project as a metaphor for the opportunity before the human species to react to and ultimately mitigate climate change which is an impending peril to the world's population.

Theoretical Framework and Discussion:

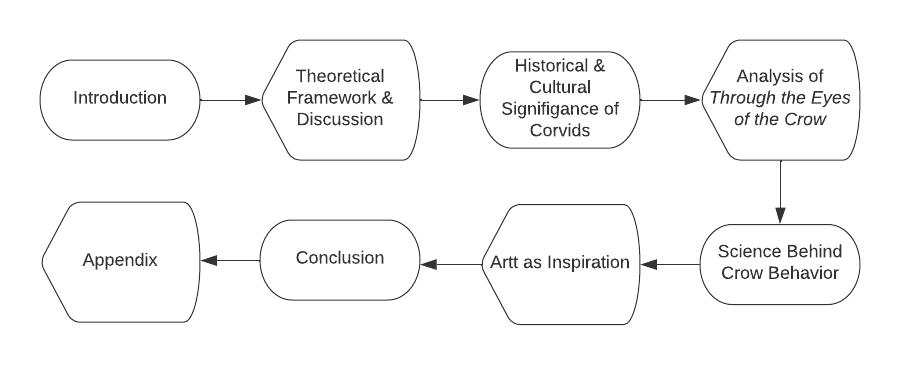

This thesis will analyze Through the Eyes of the Crow, outline the historical and cultural significance, discuss the research that informed this project, and discuss artists and artworks of inspiration. Throughout this work, I hope to draw a connection between the crow species and the human condition we currently exist in, compelling the viewer/participant toward action to mitigate current circumstances and ultimately ensure our survival.

Theorists that are referenced within this thesis include Claude Lévi-Strauss (Structuralist Theory), Stuart Hall (Theories of Representation), Liesbet van Zonnen (Feminist Theory), and David Gauntlett (Theories of Identity). The artwork itself is informed primarily by scientific research regarding crow ecology.

Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, within Structural Anthropology, proposed that the raven holds mystic qualities within many cultures due to serving as an intermediary between life and death (Strauss, 1974). In many cultures, corvids serve as symbols of bad omens to wisdom. Corvids also often scavenge for food, primarily dead animals. Due to this, the corvids are primarily associated with death. Within this thesis, corvids also are associated with death, tying largely back into themes of loss and mourning in the presence of climate change.

Historical and Cultural Significance of Crows/Ravens

Within Norse mythology, ravens are symbols of thoughtfulness and wisdom. Odin, a wise god in Norse mythology, sacrificed his eyes to gain his infamous insight. Due to

this, he possessed two ravens, Huginn and Munin, that helped him see throughout the nine realms of Asgard (Knutsen, 2011). Huginn traditionally symbolizes thought, while Munin symbolizes memory or mind (Knutsen, 2011). In some mythological texts, the two ravens also welcome fallen soldiers into Vahalla, a hall for slain warriors that acts as an honorable afterlife (O'Donoghue, 2007). Again, we see a return to the Corvids acting as a symbol of death.

Similarly, within South Asian culture and Hinduism, the crow symbolizes death and bad omens. Yama (or Yamadharmaraja) is the god of the dead in Indian mythology. The crow acts as a messenger for Yama, bringing death messages across the land (Shrestha, 2006). It is also believed that when an individual dies, their soul is temporarily carried within the crow's body (Shrestha, 2006). Within Serbian Epic Poetry, corvids similarly are messengers of death. In the Kosovo myth, the Serbian ruler Lazar was challenged by Ottoman Sultan Murad I, referred to as the Battle of Kosovo (Humphrey, 2013). Lazar wanted to die as a martyr in this battle, with the reasoning being that the Serbian people would end up in the Kingdom of Heaven (Humphrey, 2013). Within this Epic, the raven plays a messenger role, communicating to individuals the death of their loved ones in the battle.

Regarding battle, corvids are also present in conflict within Celtic mythology. In Celtic mythology, The Morrígan (a goddess), translating roughly to great queen, takes the form of a crow regarding battle and fate (Aldhouse-Green, 2015). The sister of The Morrígan, Babd Catha, is a goddess of war who similarly turns into a crow in battle (Aldhouse-Green, 2015).

In Greek mythology, corvids also play a messenger role, but they are more associated with bad omens. Corvids have strong ties to Apollo, the God of Prophecy. The god was in a relationship with Coronis, a Thessalian Princess. While still in a relationship with Apollo, Coronis had an affair with a mortal man named Ischys (Fumo, 2004). Apollo had given Coronis a raven to protect her in her travels to earth, but Apollo eventually found out about the affair due to the raven later conveying the information (Fumo, 2004). In anger about the affair, Apollo sent Artemis to kill the couple and later turned Coronis into a constellation.

The corvid family also symbolizes various ideals in different religions. Within Christianity, the raven was the first bird that Noah let off the Ark in Genesis (Bible, Genesis 8:6-7, 1996). After the release of the raven, Noah also let a dove go (Bible, Genesis 8:6-7, 1996). The intention behind the release of the dove was to see if it could find any surfaces to land on, and since there was still water, the dove could not find a landing spot and returned (Moberly, 2000). The release of the crow intended to see if the crow would find carnage to eat, and the bird eventually returned to the boat, as well (Moberly, 2000).

Within Islam, the raven taught humankind how to deal with the concept and aftermath of a death. The story of Cain and Abel ends with the death of Abel and Cain not knowing how to dispose of the body:

Then Allah sent a raven, who scratched the ground, to show him how to hide the shame of his brother. ‘Woe is me!’ said he; ‘Was I not even able to be as this raven, and to hide the shame of my brother?’ Then he became full of regrets (Quran, Surah 5:31).

The ‘Holy One’ in the text sends two ravens to Cain, and one of the birds kills the other (Berman, 1995; Friedlander, 1965). To show Cain how to bury Abel, the surviving raven digs a grave for the fallen raven with its talons and buries the body (Berman, 1995). Cain follows suit and buries his brother. Throughout the world’s folklore, mythology, and religion, crows serve to symbolize many ideals, but the most prevalent are ideals that surround the messaging and act of death. While this is how humans perceive and give meaning to crows, how do crows perceive interactions within their species?

Through the Eyes of the Crow

The physiological vision of the crow is unique. Due to their eye structure, crows have a more comprehensive vision view than humans (Kanai et al., 2014). Along with this, crows have unstable vision due to the anatomical position of the eyes connected to the beak (Kanai et al., 2014). Most birds, including crows, have a fourth cone to see colors closer to ultraviolet light wavelengths (Eaton, 2005). Most humans have three cones, making ultraviolet light not accessible to the human eye (Roorda & Williams, 1999). Once one understands the science behind how crows physically see, one can focus on how crows perceive and behave accordingly.

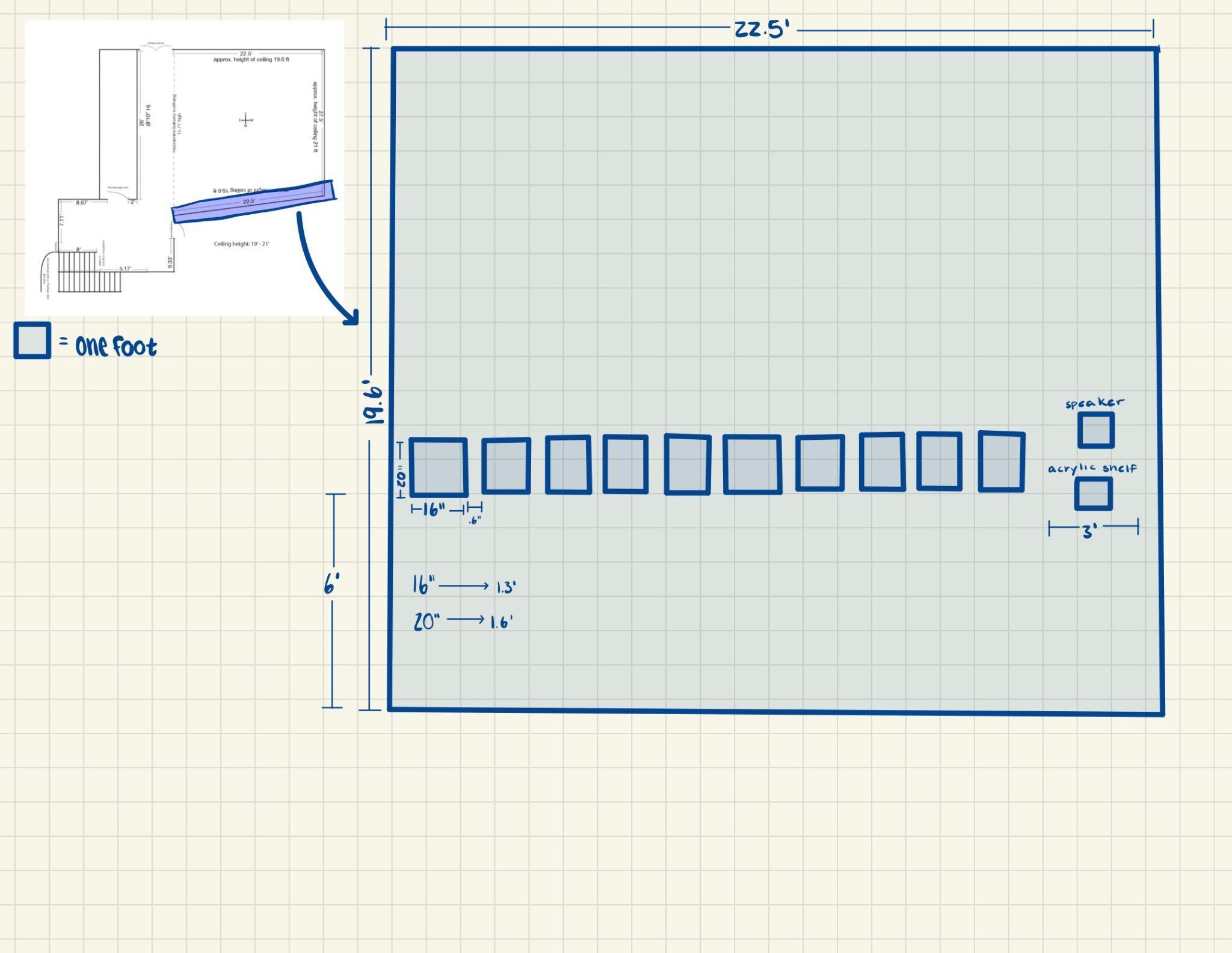

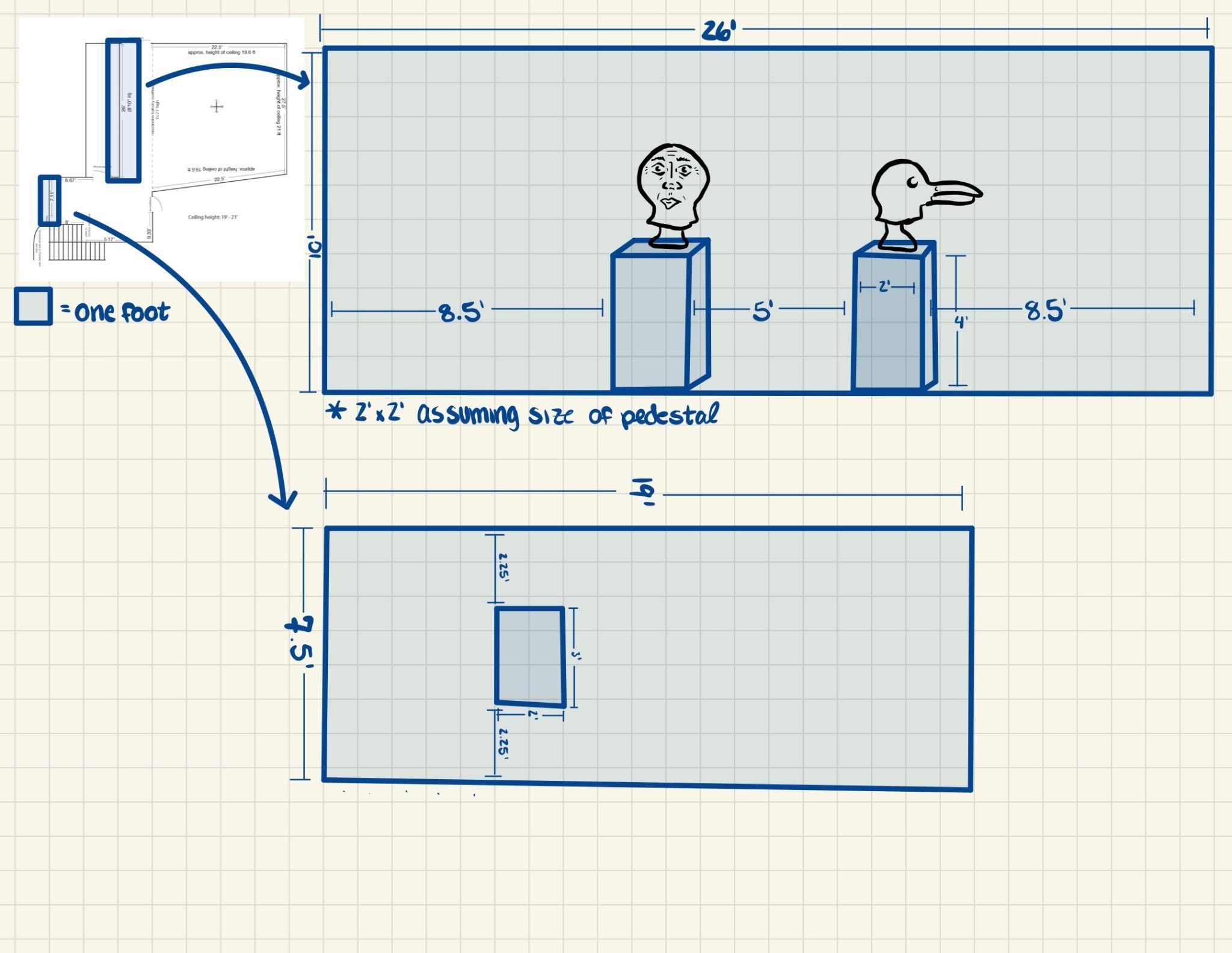

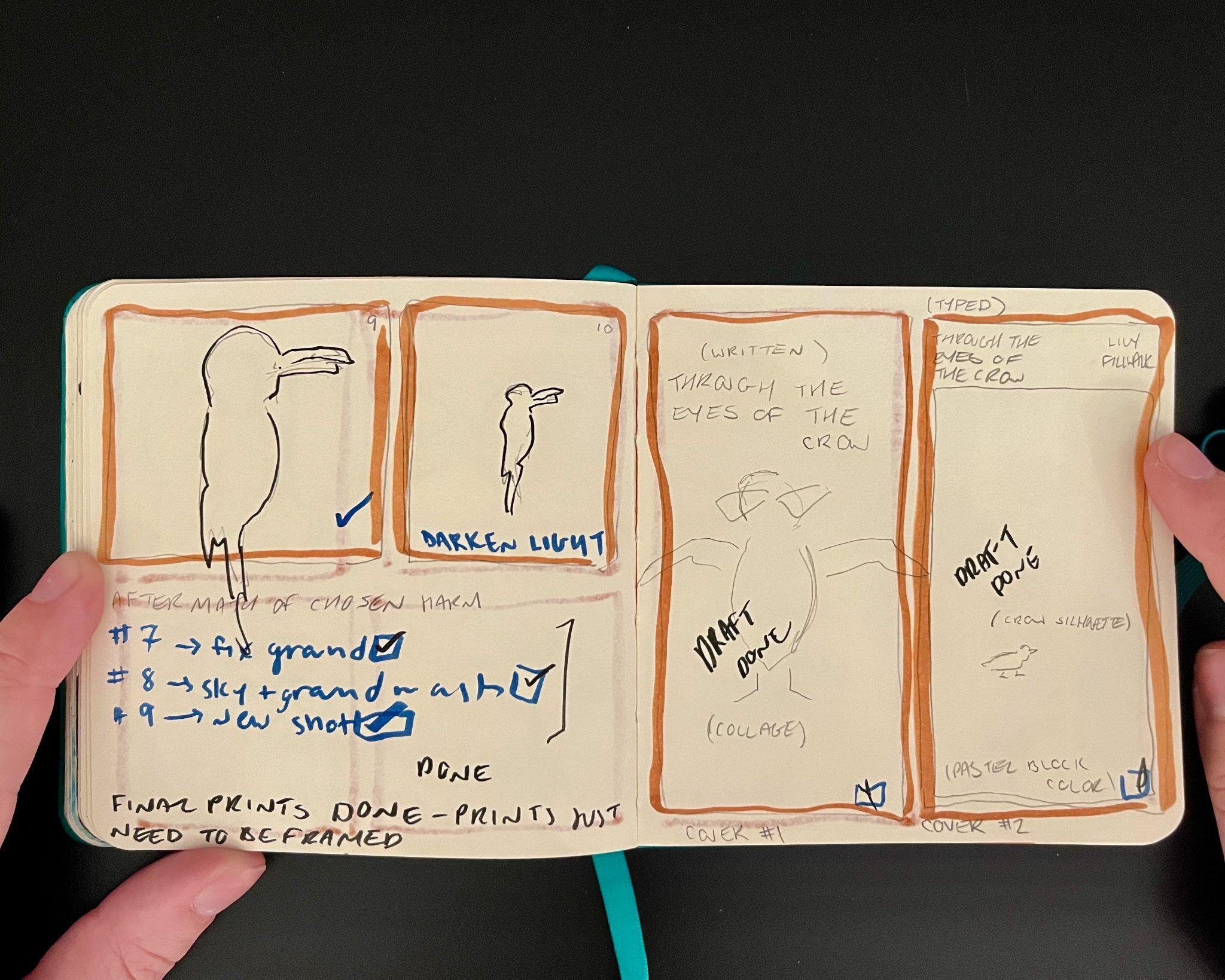

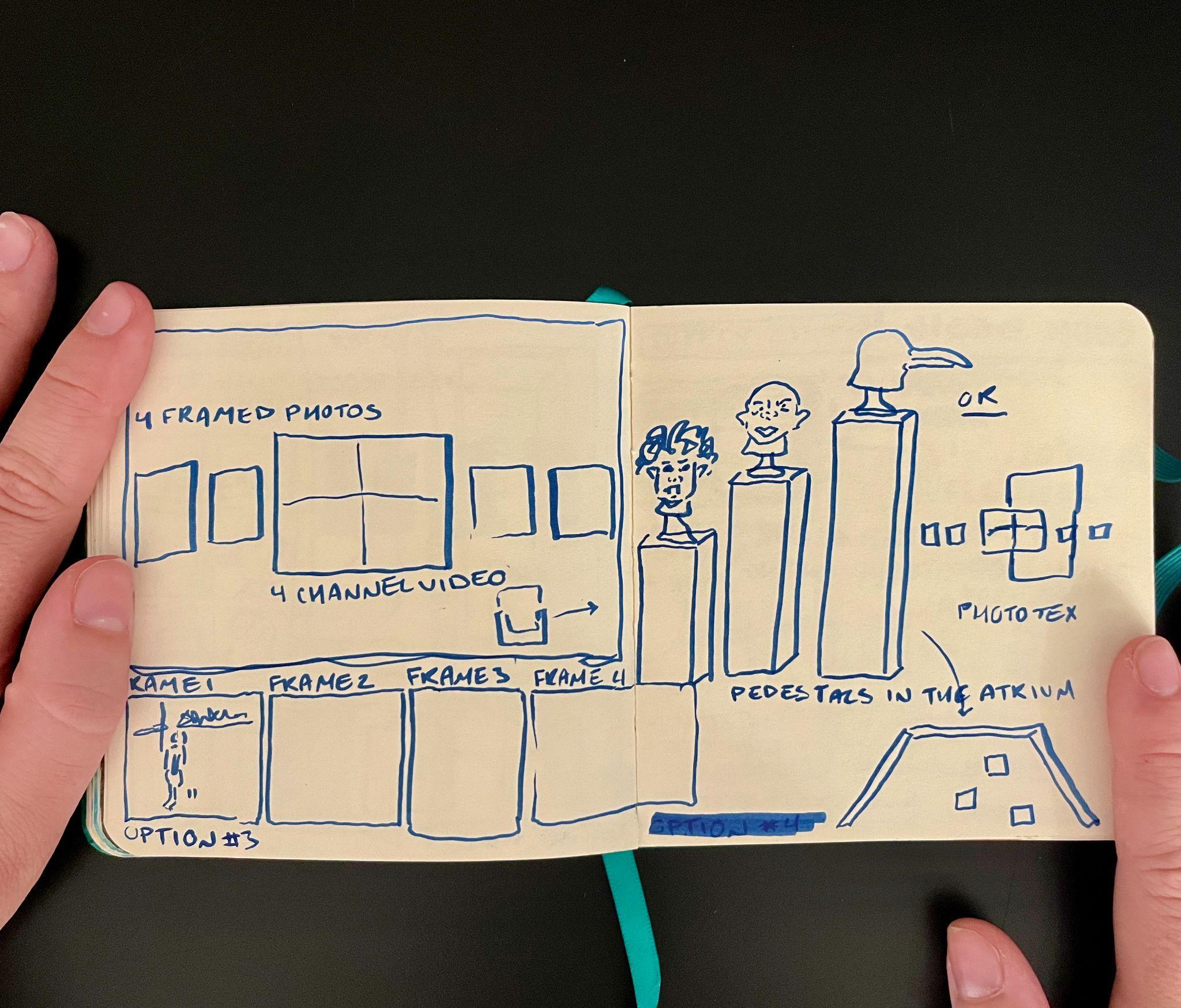

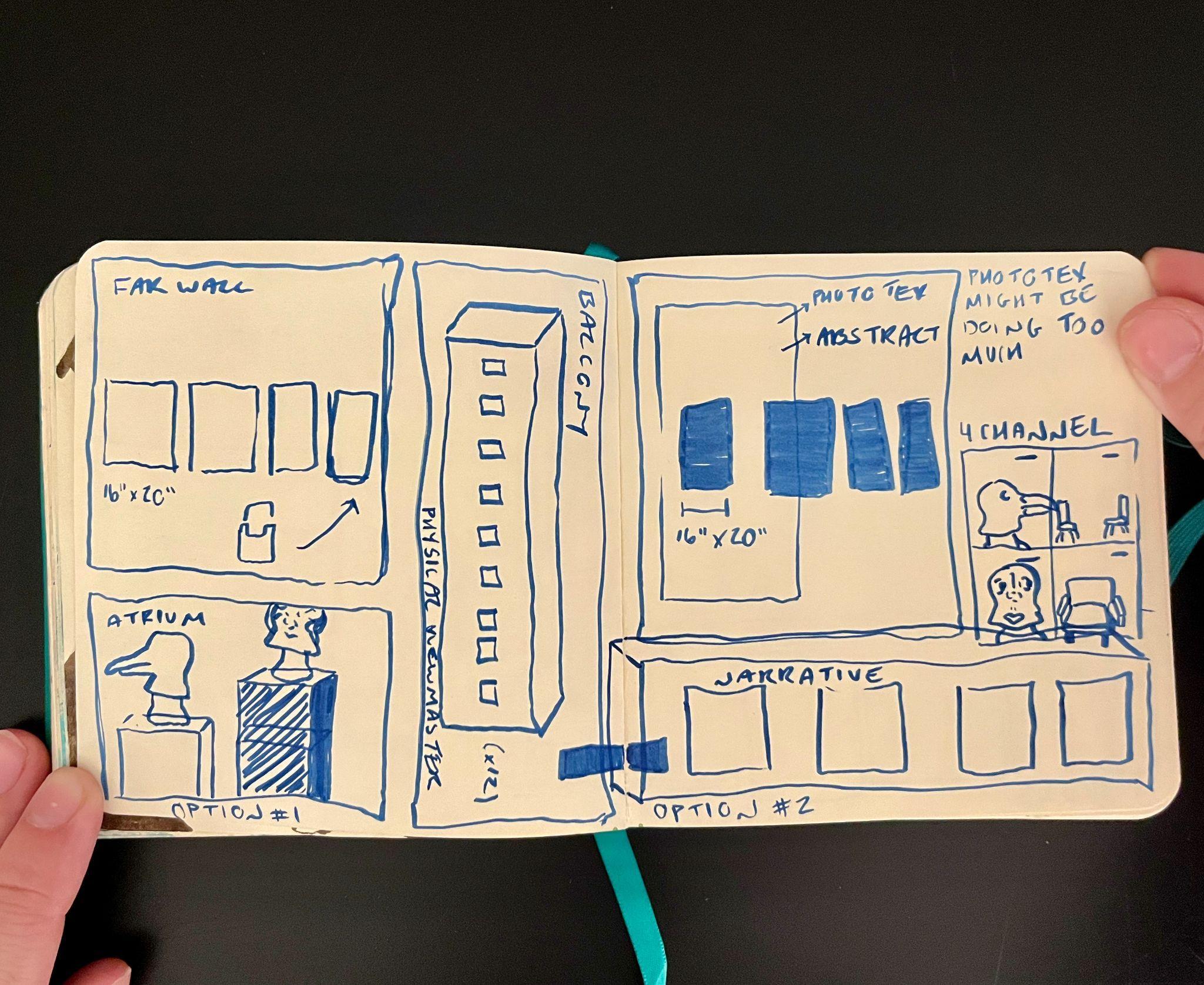

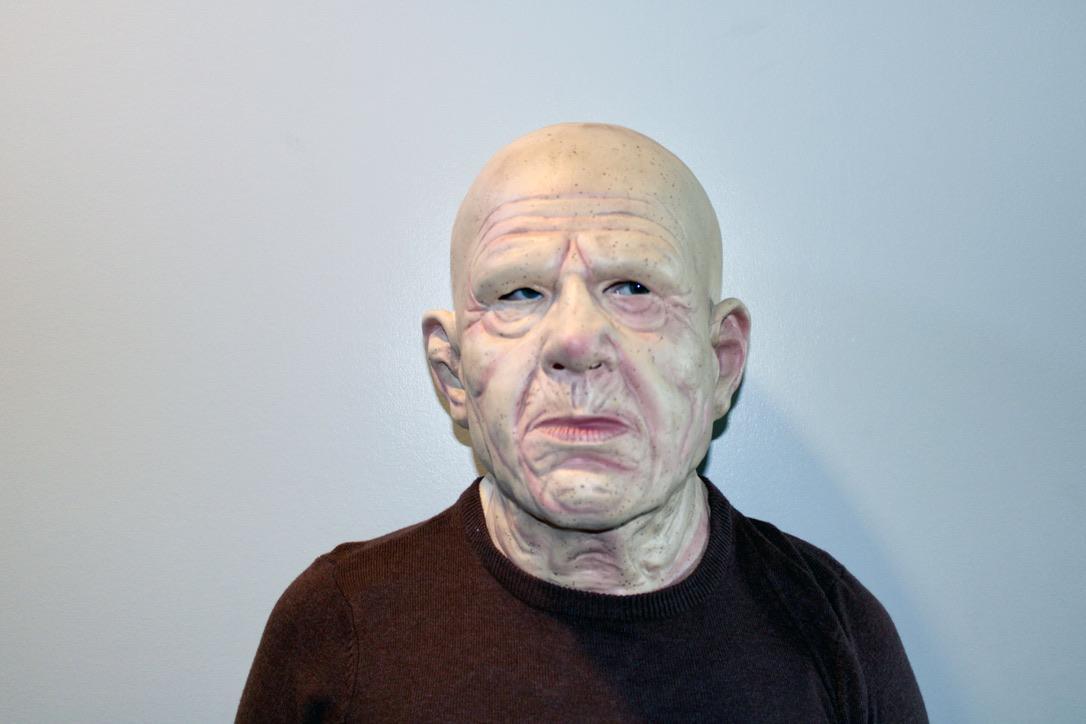

My thesis entitled Through the Eyes of the Crow explores how crows perceive and react to danger and death within their surroundings. A narrative of ten photos is presented on the gallery wall within the work. Within the narrative, the crow serves as a metaphor for how the species perceives a threat and potential death within their surroundings due to human actions. This thesis is also centered around how there will be an increase in crow deaths due to anthropogenic changes to our environment and what mourning might look like in the future.

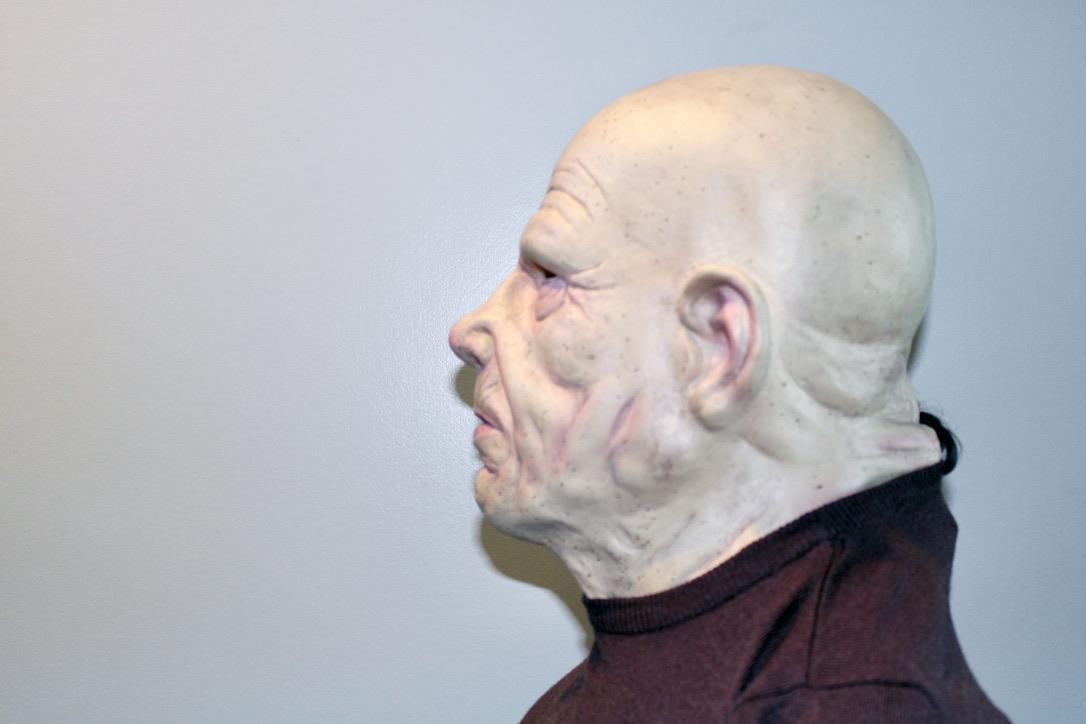

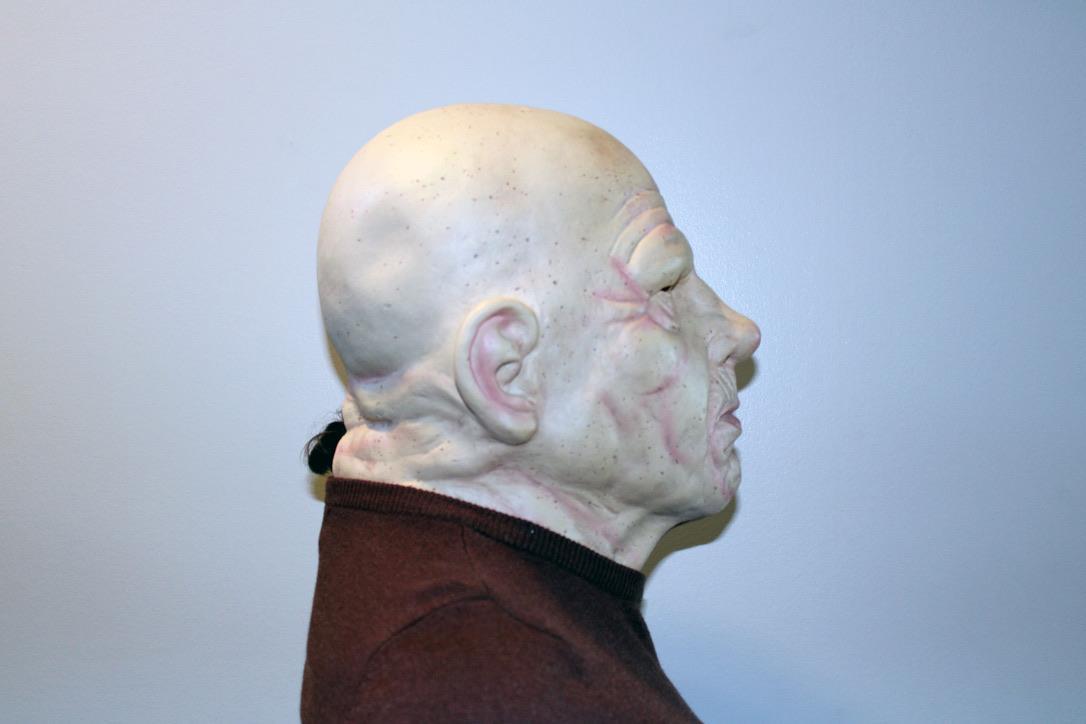

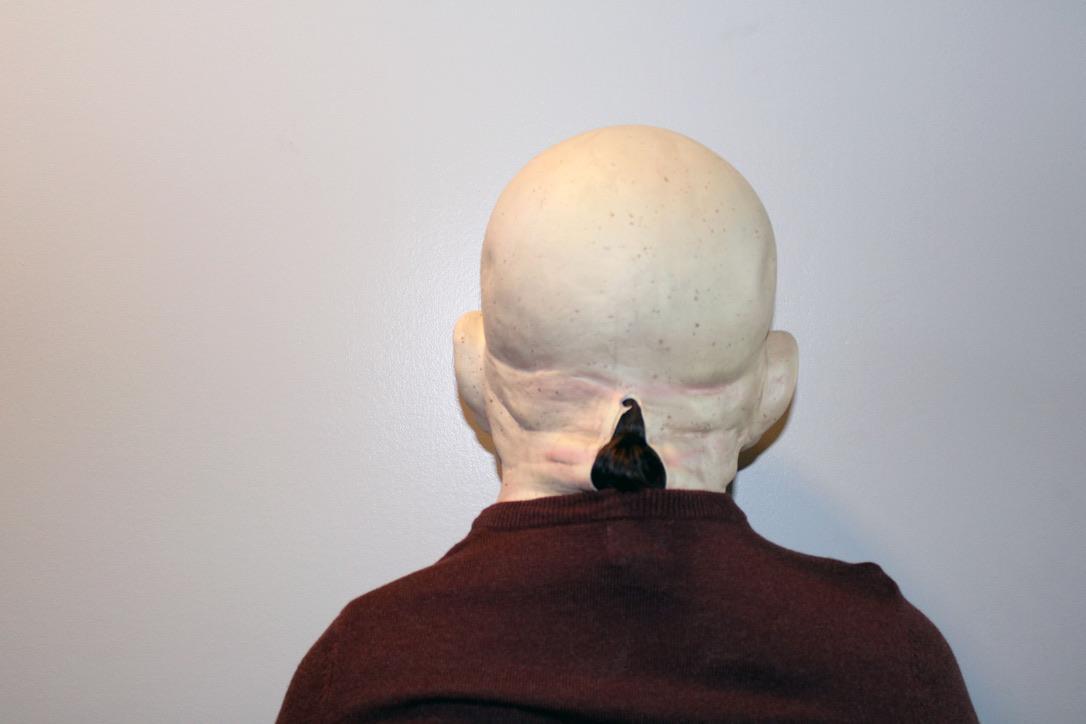

The narrative, being able to be read left to right, begins with an image of the back of the crow's head. Then, the camera moves into the crow mask and through the eyes. This imagery indicates to the viewer that they are perceiving through a non-human lens.

Figures 2-11. Narrative of Throughout the Eyes of the Crow

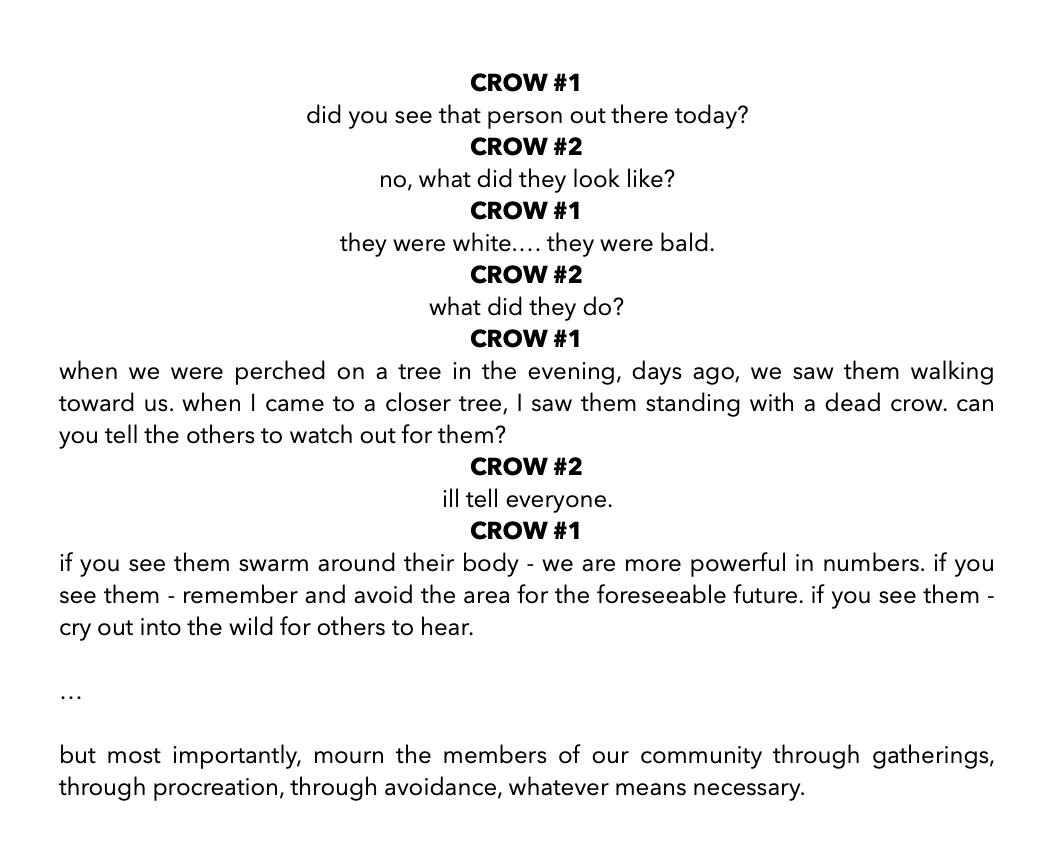

The rest of the narrative depicts a masked figure pulling a crow out of its pocket and launching the body across a field. The end of the narrative includes a dead crow, indicating the figure killed or inflicted harm on the animal. The figure within the work acts as a symbol of the harm humans have caused the natural world, leading to a larger issue of anthropogenic climate change. The crow uses their perception abilities within the narrative to increase their species’ survival. In conjunction with the narrative, there is a video component to Through the Eyes of the Crow, entitled Crow Conversation (Figure 3), where two crows converse about the perception of the narrative. The conversation includes advice on survival techniques in the presence of a threat and instructions on how to mourn the loss of a fellow crow (Appendix B).

The audio, consisting of various crow calls, and masks used being present, gives context to the narrative. The audio is a compilation of crow calls in California sourced from the Macauly Library (Media Search - eBird and Macaulay Library, 2012). The work was created and shown in California, and the audio makes place-based ties rather than crow calls from throughout the nation or world. While simultaneously listening to the audio component, walking through the narrative is intended to immerse the viewer’s senses fully.

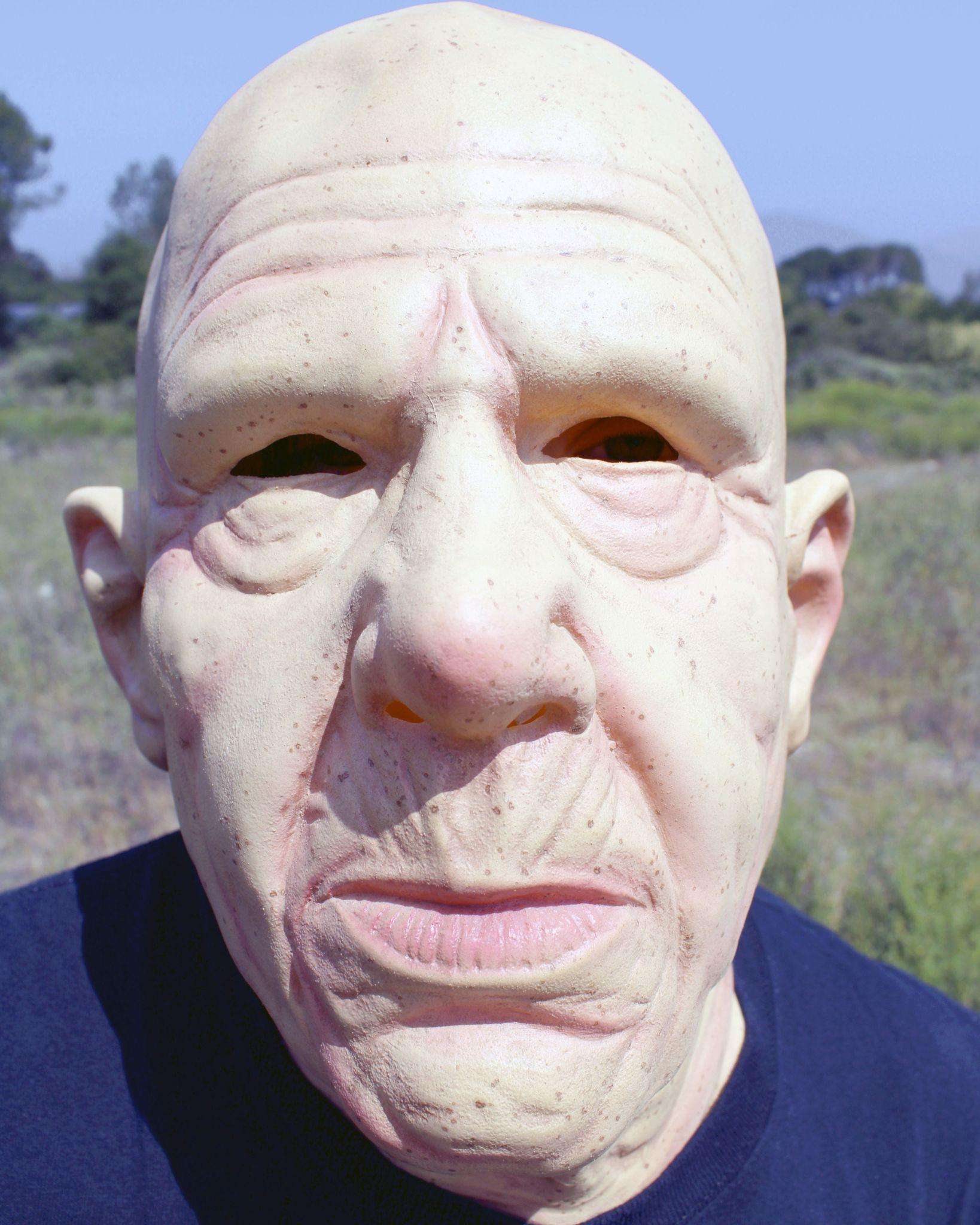

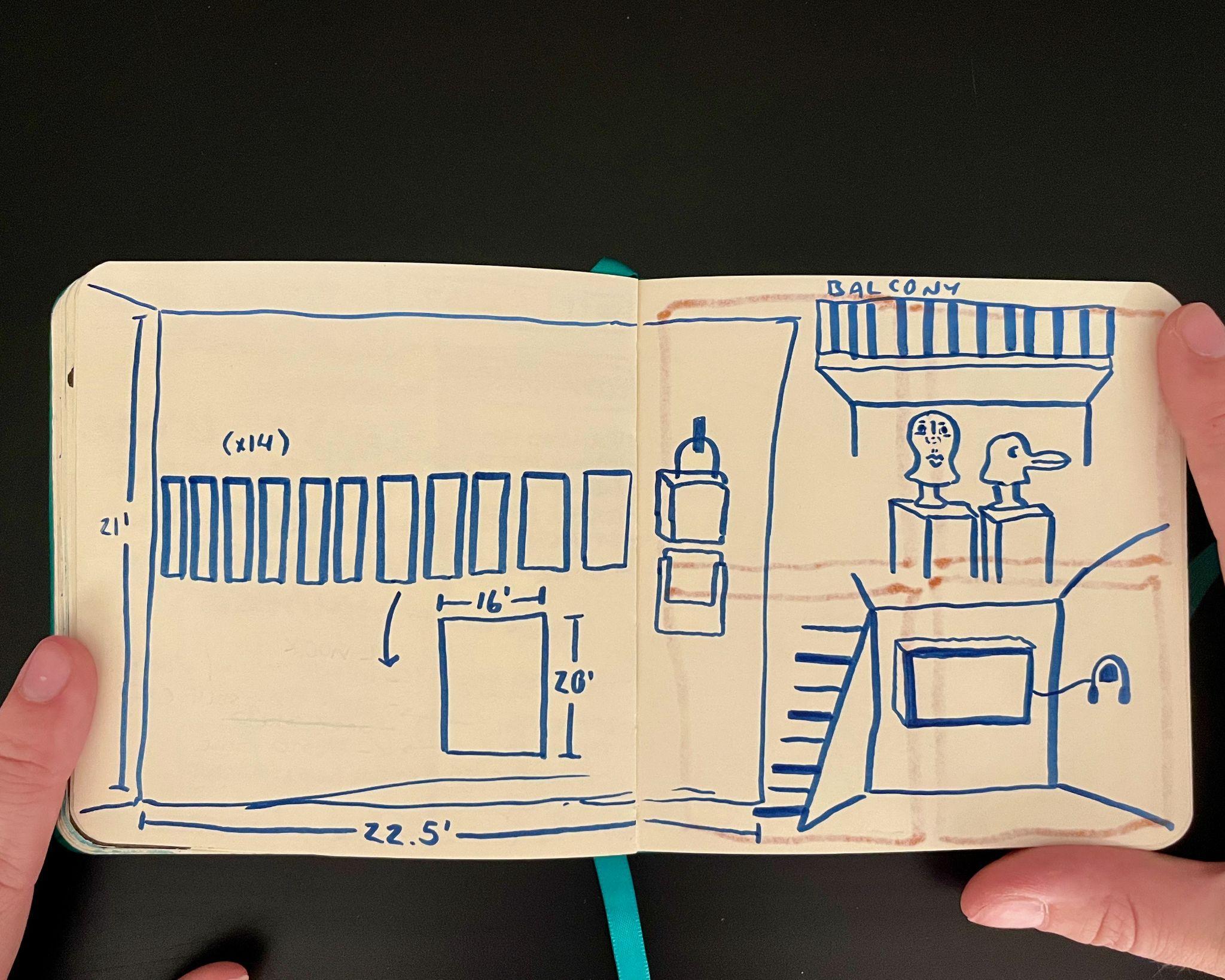

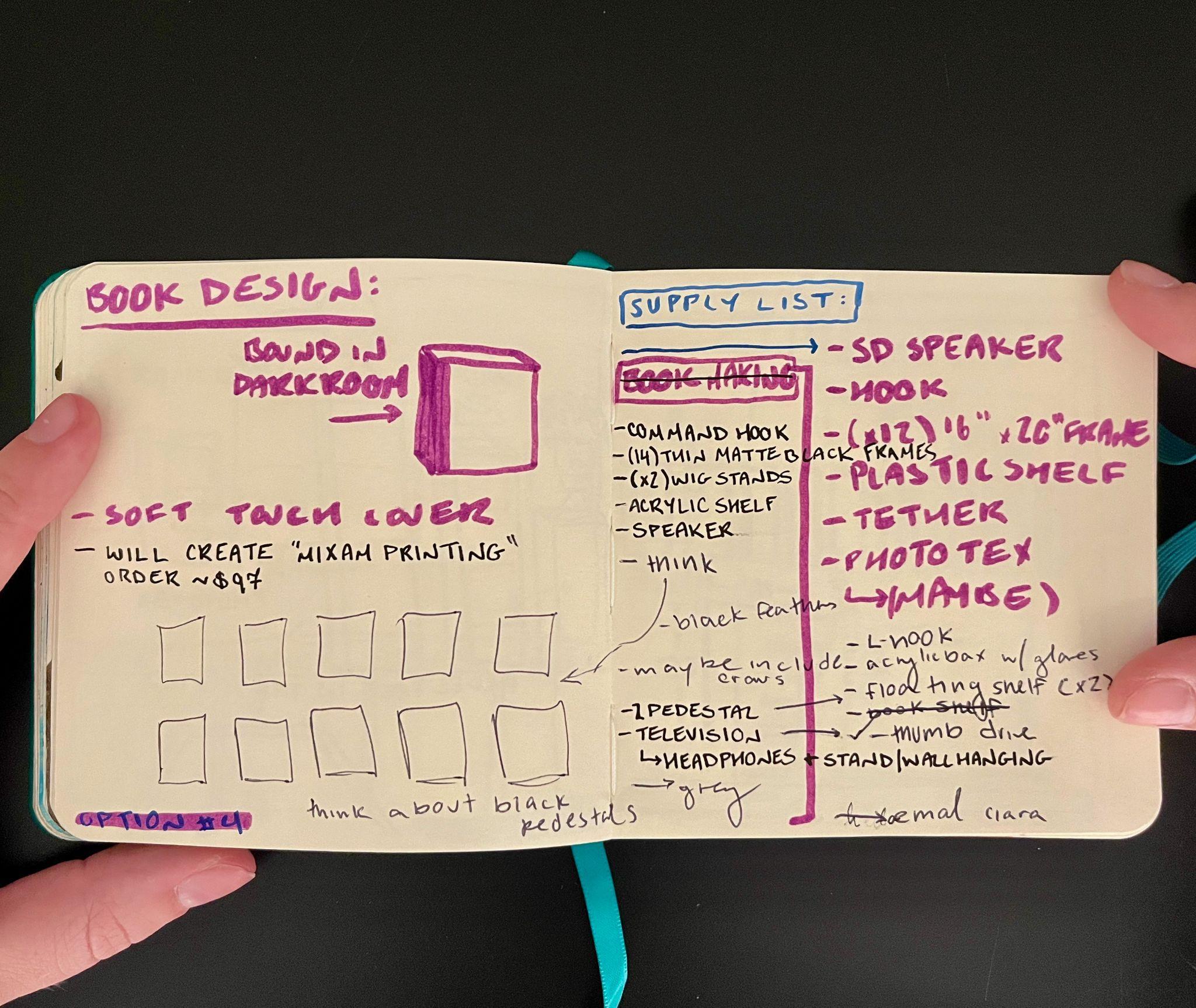

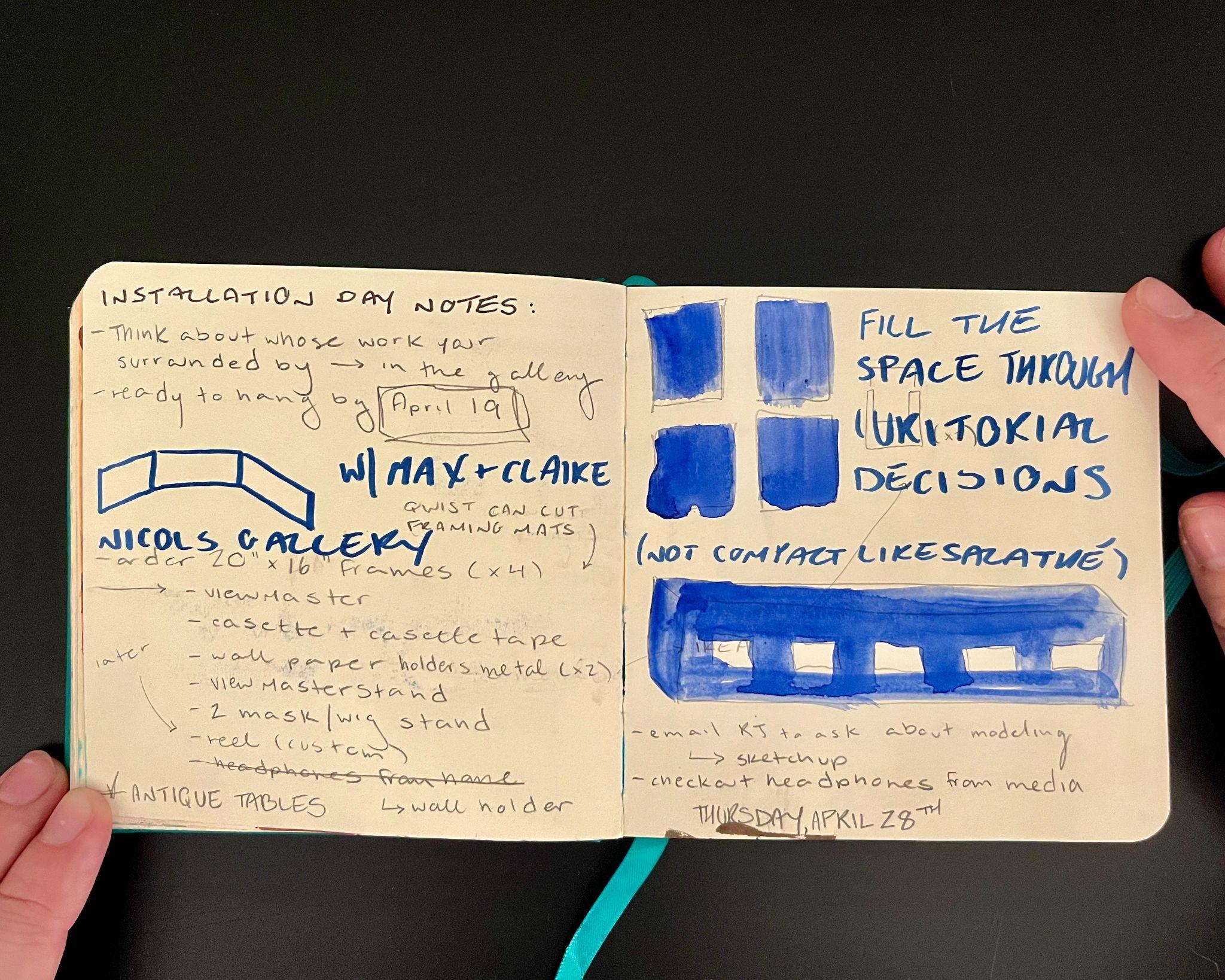

Below is the planned layout of Through the Eyes of the Crow (Figure 4). 10 photos illustrating a narrative lined in a row on the wall in 16”x 20” frames. On the right side of the installation are a hung speaker and a floating shelf holding the written version of the thesis. Two masks, a white male and a crow, are also featured in work.

Viewing means were limited due to the current COVID-19 pandemic1 . Due to consciousness of the spreading of germs during interaction with the work, the use of an immersive device such as a ViewMaster or binoculars were not used in the installation. While these mediums were not able to be utilized, I incorporated an immersive viewing experience for the audience by providing an opportunity to position oneself behind the mask and perceive from the crow’s vantage point.

While there might not be a completely immersive experience for the viewer, what role does the audience play in the viewing of Through the Eyes of the Crow?

1 This work was created during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2022. Personal protective equipment (PPE), such as medical grade N95 face masks, were utilized to stop the spread of COVID. Along with this, it has been found that social interaction (i e the perception of emotions) has been hindered due to the use of facemasks within the pandemic (Carbon, 2020). There are slight parallels of the use of medical face masks and costume masks within this work due to the time of creation.

Within Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, Stuart Hall discusses the importance of representation throughout media and media language (Hamilton, 1997). Along with this, Hall emphasizes that the media created largely represents the ideological views of the producer, removing objectivity (Hamilton, 1997). Similarly, David Gauntlett, within Media, Gender, and Identity: an Introduction, discusses the role of the audience as being an active rather than a passive entity (Gauntlett, 2008). Just as in Hall and Gauntlett's works, through the story depicted in Through the Eyes of the Crow, the audience is allowed to experience fear through the lens of a crow. While the scenes are fictional, they are informed by research and relate to more prominent themes of the dangers of anthropogenic climate change. Climate change is currently an extremely controversial topic and is now a political issue rather than one based on science. As in the case of the works presented, Through the Eyes of the Crow raises the issue of how one’s lense (and what it, therefore, sees as credible data) influences interpretation and sense of urgency related to climate change. This is similar to this written thesis, where the audience can take what elements of my defense make sense to them and leave what they disagree. In the media field, audience activity is described as the Theory of Identity, where “that while everyone is an individual, people tend to exist within larger groups who are similar to them. [Gauntlett] thinks the media do not create identities, but just reflect them instead” (View, 2019).

Docupoetics is “socially engaged poetry that often uses nonliterary texts—news reports, legal documents, and transcribed oral histories, for example—and sometimes incorporates original reporting” (Where Poetry Meets Journalism, 2019). In some texts, such as M Archive by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, the work becomes the art, the artificial artifact with artificial data. The photo narrative within Through the Eyes of the Crow visually emulates the ideas of docupoetics, creating a fictional story based on the extensive scientific research behind crow behavior.

Throughout the Eye of the Crow, connects fiction with science in an attempt to ask questions such as:

What are the limitations of science?

What are the limitations of art?

And where do they overlap?

How do we have access to other beings through both mediums, and how does each medium fail?

The Science Behind Crow Behavior

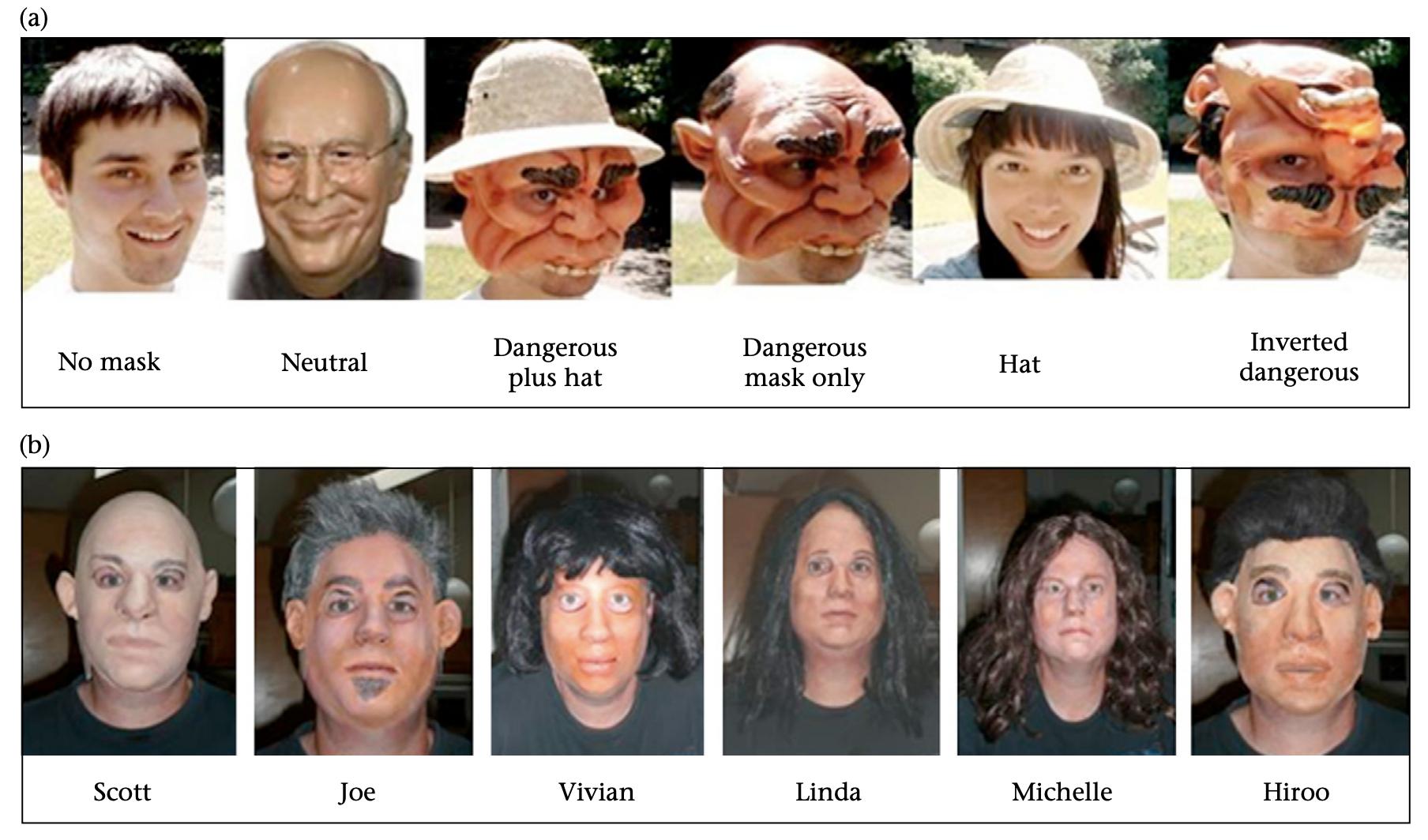

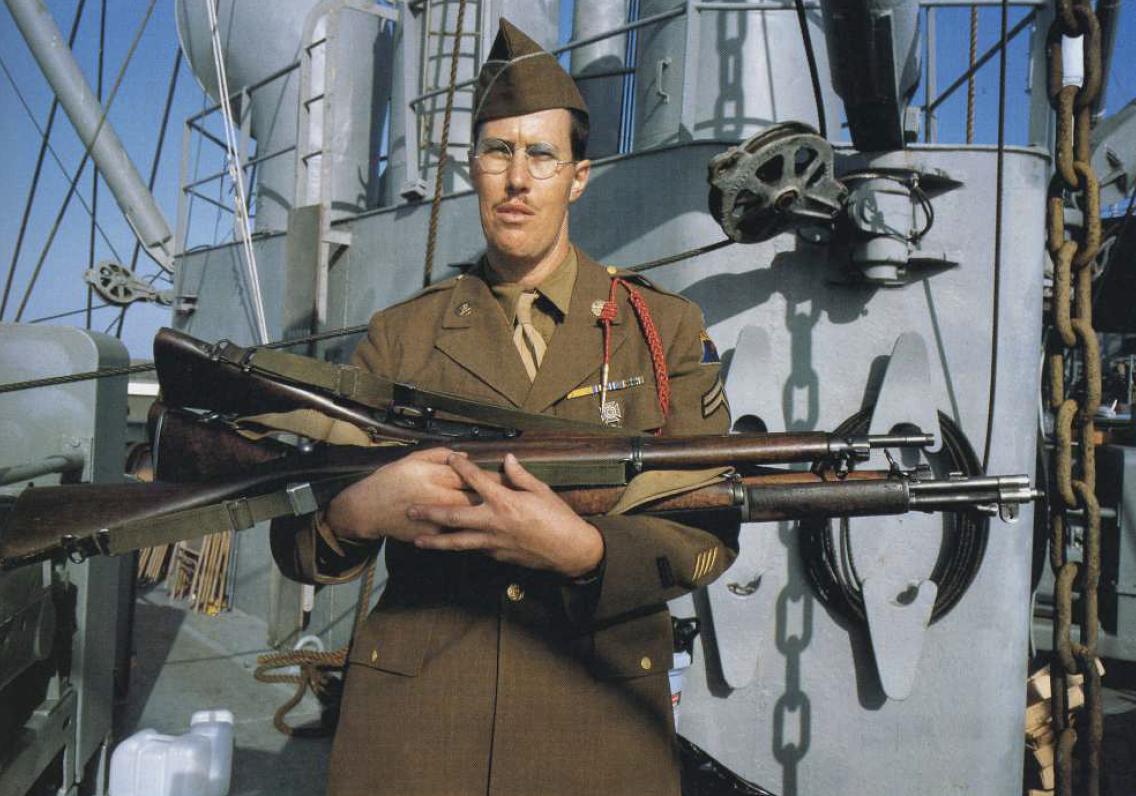

Throughout this thesis, I ultimately looked at how crows see and experience life and death. The science behind the recognition of this phenomenon inspired this project. In a study at the University of Washington, crows were presented with the stimulus of six different mask treatments to understand the species’ reaction to danger. The main scientists involved were Dr. John Marzluff and Dr. Kaeli Swift. Three of the masks

involved in the experiment were considered ‘dangerous.’ The danger presented in the study was the trapping and eventual release of 7-15 crows conducted by individuals wearing the danger masks (Marzluff et al., 2010). Masked people (both dangerous and neutral) then walked in areas where the crows were present. The study found that crows can recognize a face of danger in various settings, such as one face in a crowd, and remember the face of the identified threat for 2.7 years (Marzluff et al., 2010). Crows can also communicate the face of danger to other crows, creating a sense of mob mentality for protection. The various masks used in the study are presented below (Fig. 5).

Figure X. “(a) Treatments for experiment 1, from left to right: no mask, neutral mask, dangerous mask plus hat, dangerous mask alone, dangerous hat alone, and inverted dangerous mask. (b) Treatments for experiment 2 and 3. Each of the first four masks (from left) was used in a single site as the dangerous mask; the last two masks (from right) were always neutral masks. These masks were custom-made by taking moulds from three males and three females, half of Asian descent and half of European descent.” (Marzluff et al., 2010).

Along with facial recognition, crows have the cognitive ability to recognize and react to the death of their species. Within a study observing the Wild American crow’s reaction to the death of a member of its species, it was found that crows can spatially remember danger (Swift et al., 2015). When crows witnessed a threat, such as a human near a dead crow, the location of the sighting was approached more carefully with actions such as collecting food (Swift et al., 2015).

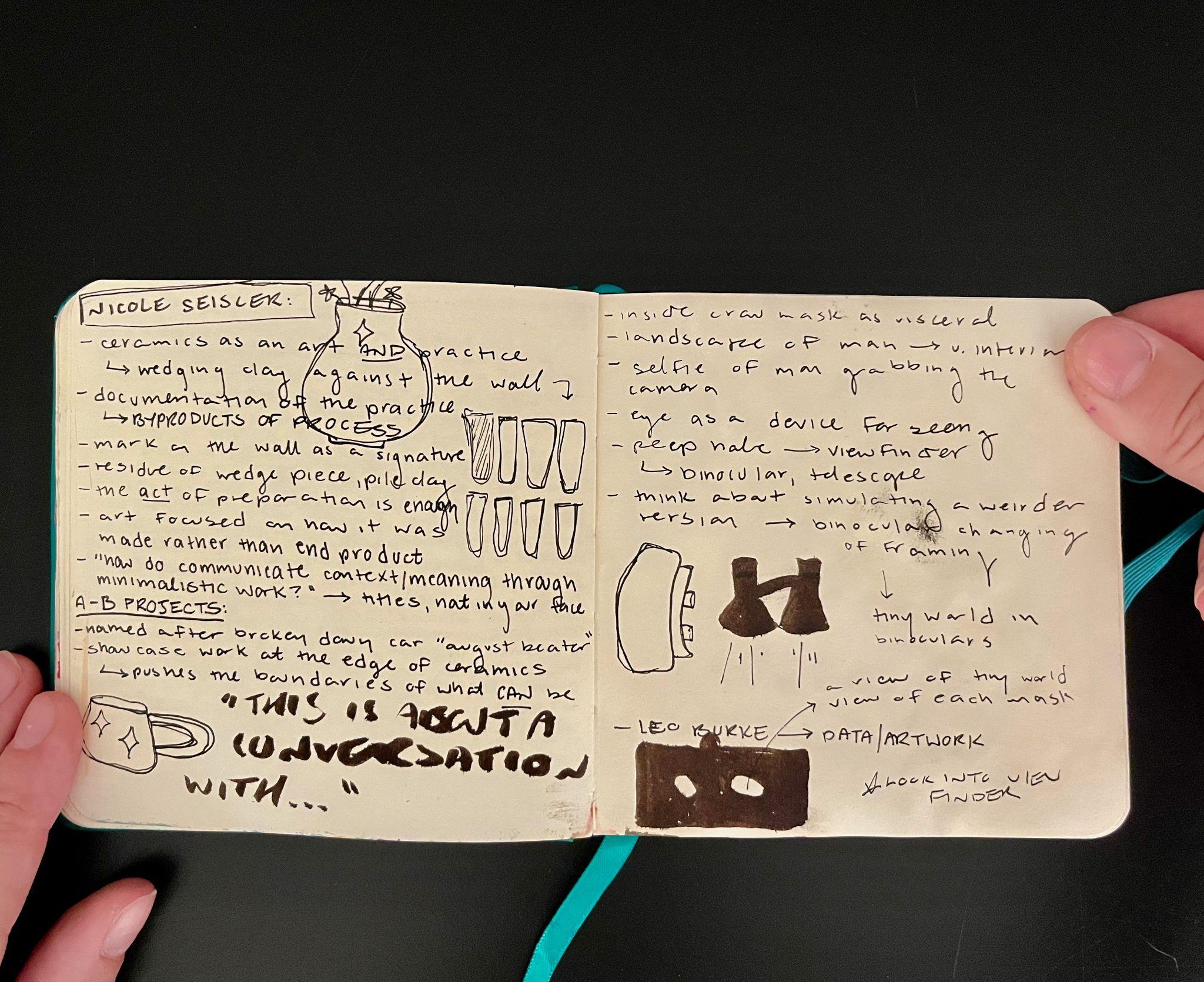

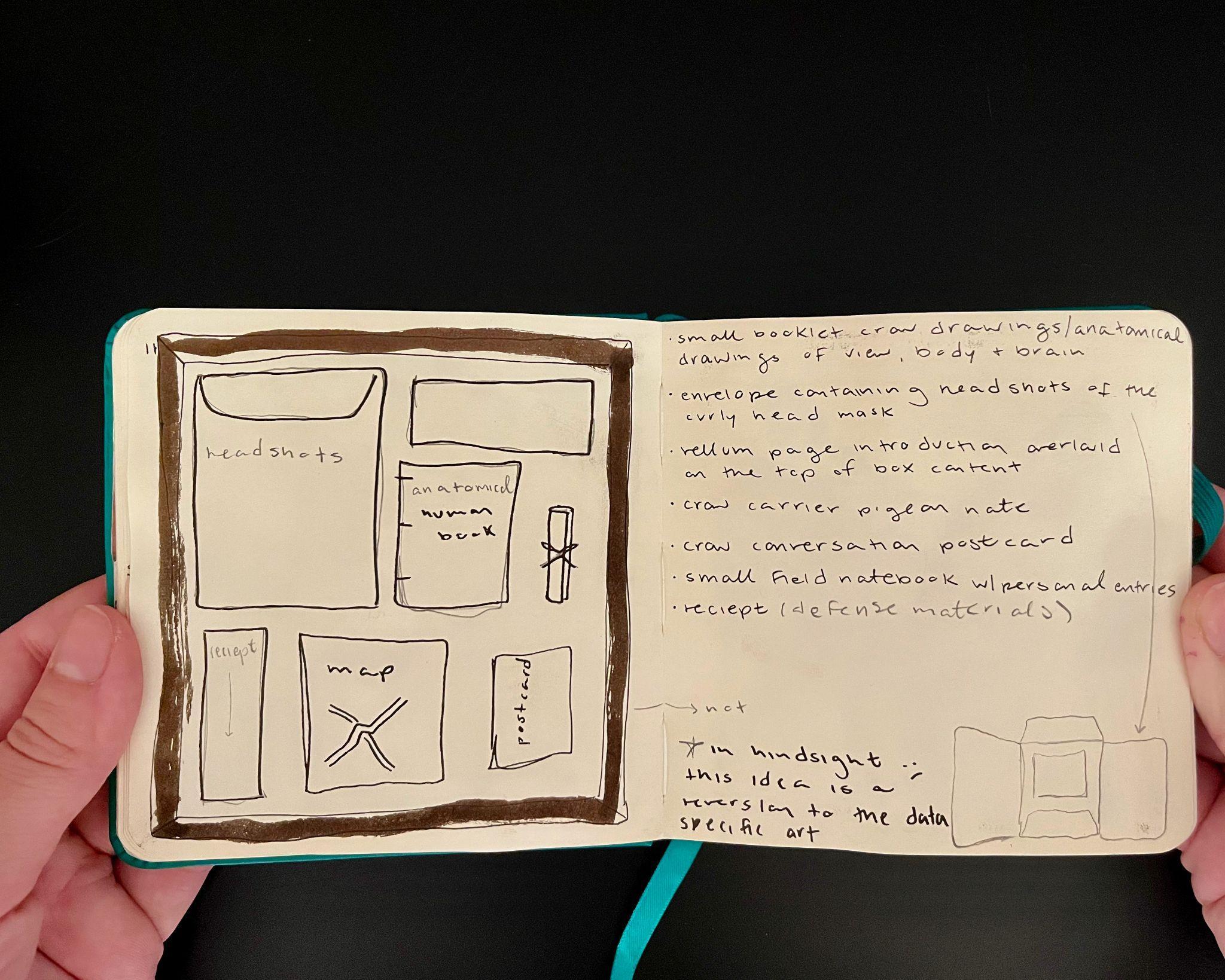

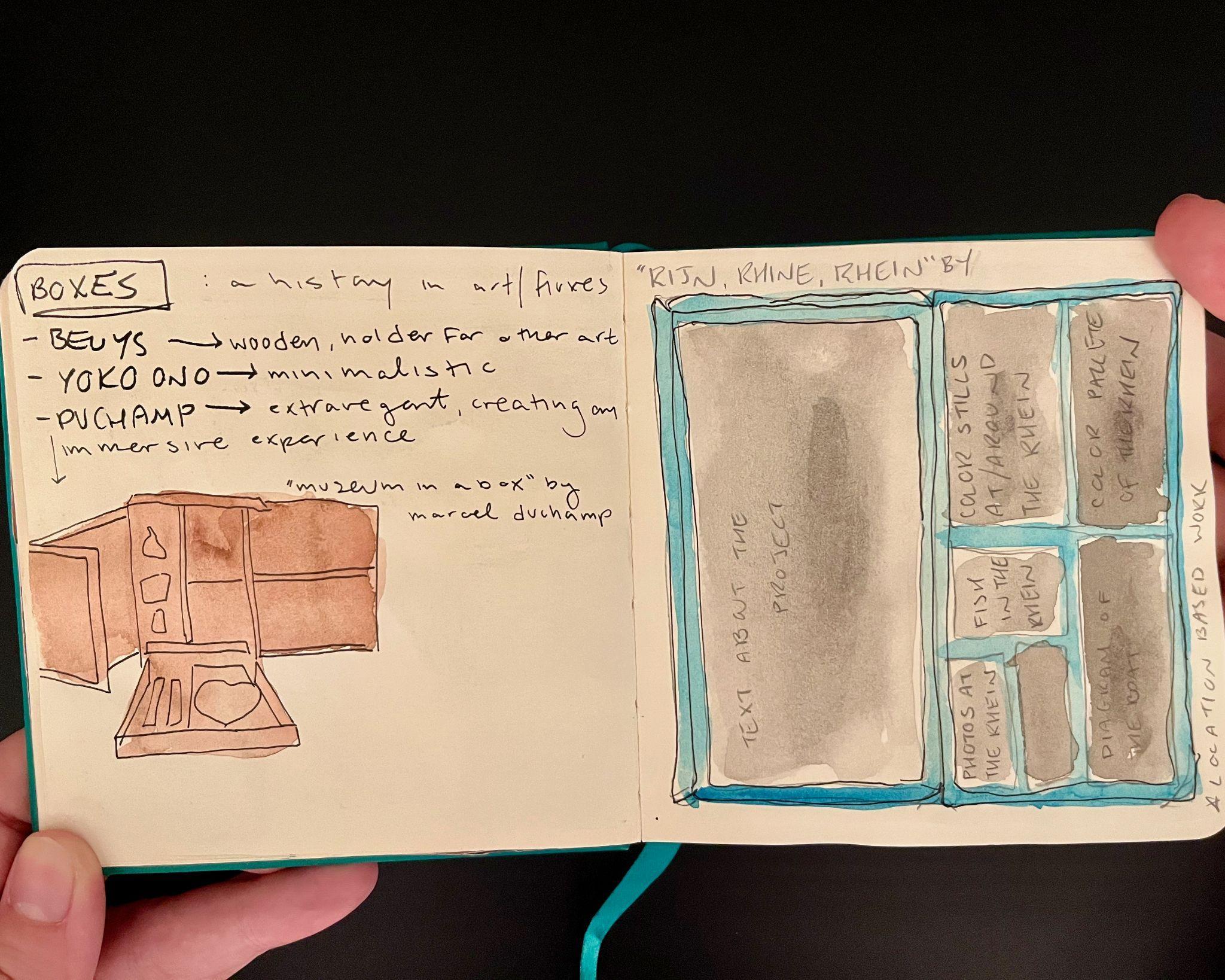

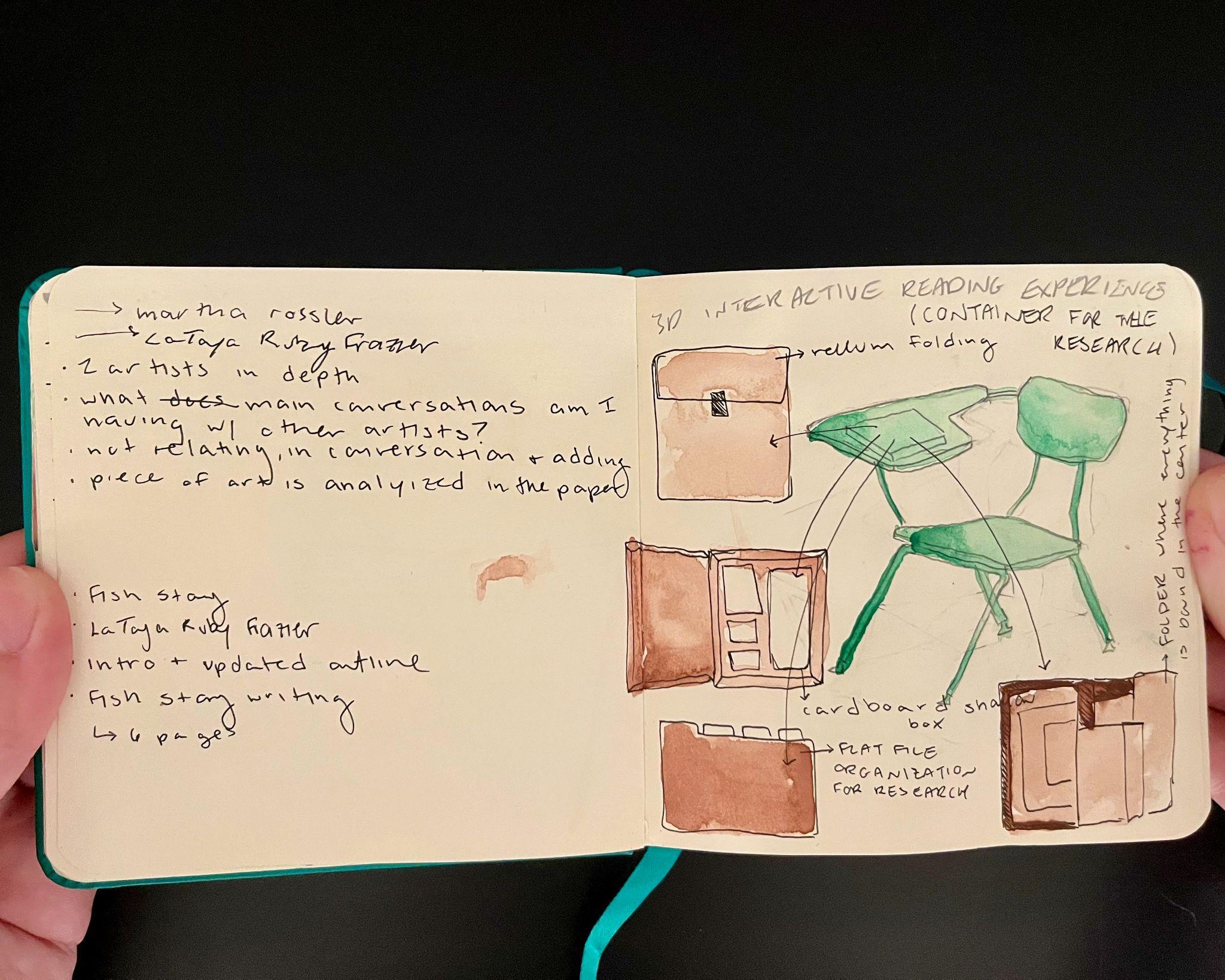

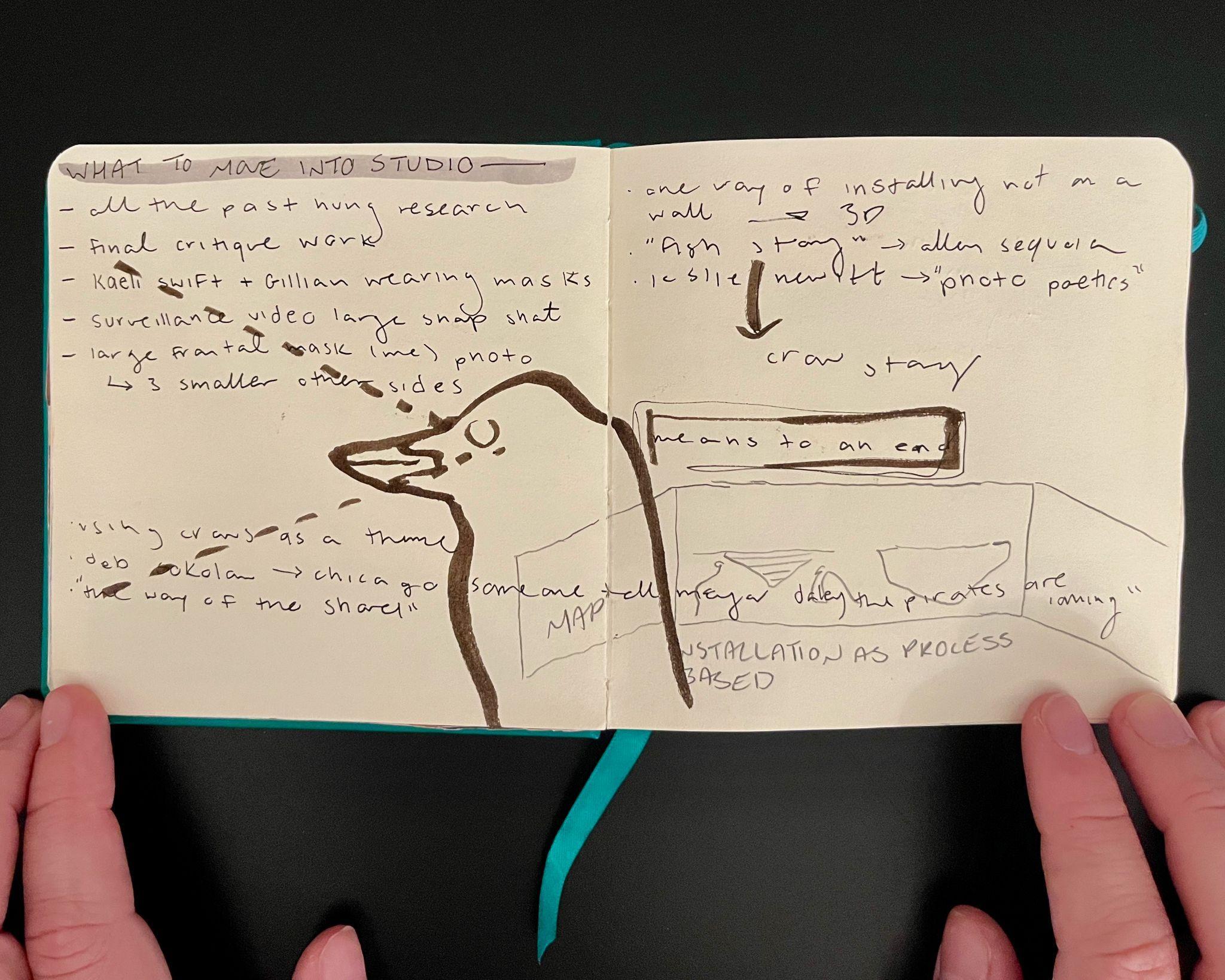

Data within Dr. Kaeli Swift’s publications informed a sound piece created early on within my thesis process. The work sonfied the data collected within the study ‘Wild American crows gather around their dead to learn about danger.’ I transformed the data, and each data point was assigned a tone. This sound piece transformed throughout the creation and development of my thesis project and was ultimately not included in my final thesis. I removed this piece strictly due to presenting data rather than representing it. In similar regard, I overlaid graphs of the same data with abstract photos of crows. The research inspired the creation of this data-based art and, throughout time, led to the current state of the project. While this approach was more based on science and data, I challenged myself in the spring semester to take more of a creative approach to this project relating to masks and multispecies perception. I have included my process throughout the creation of the work, including sketchbook pages, studio walls, and failed concepts (Appendix A, Appendix D, Appendix E).

Thinking about the science behind crow's vision, we can apply this information to a more creative thought process. This thesis is centered and grounded in research, which

is informed by the practice of other research-based artists such as LaToya Ruby Frazier and Allan Sekula.

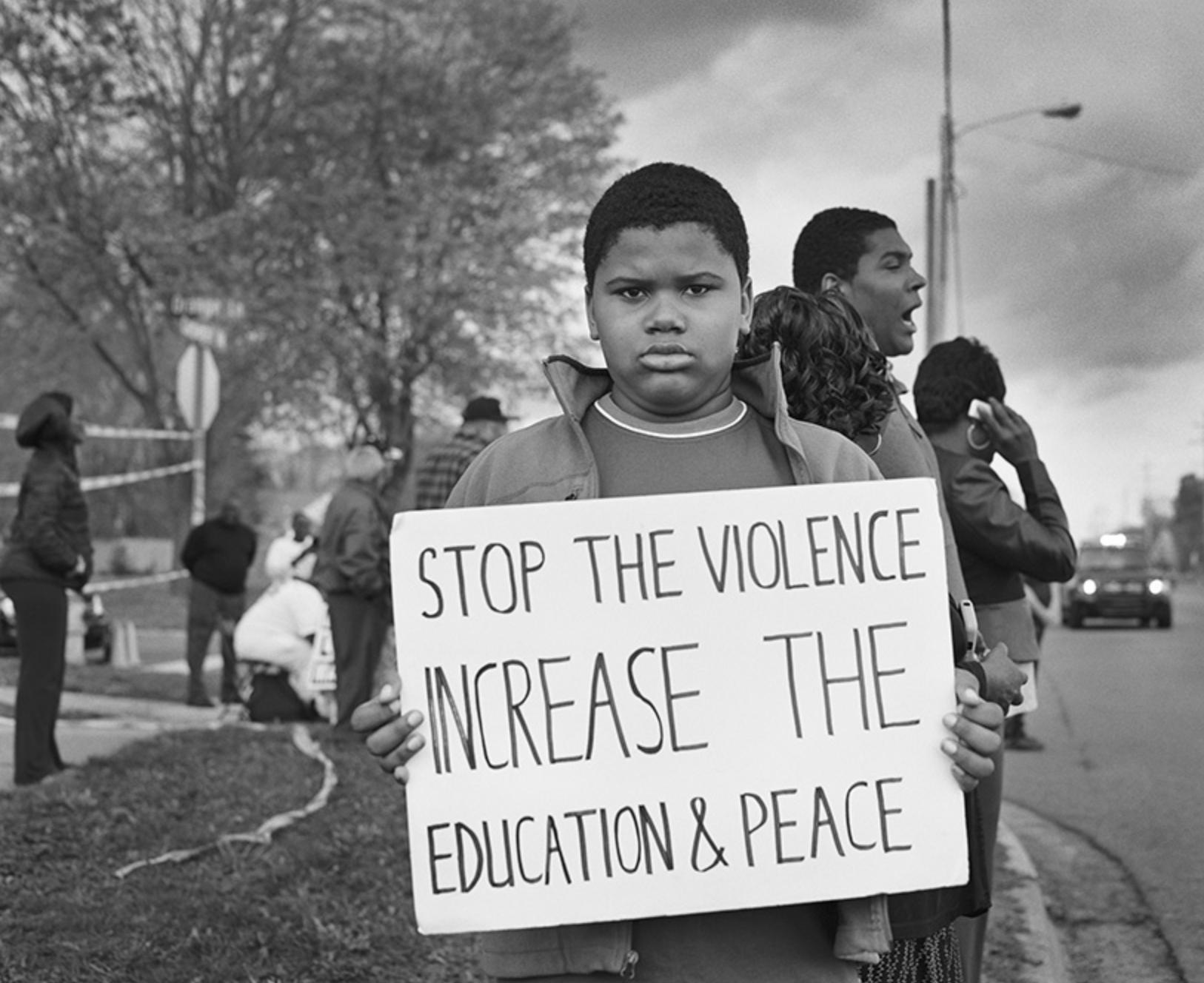

Flint is Family by LaToya Ruby Frazier

Flint is Family, created in 2016 by LaToya Ruby Frazier, is a photo essay documenting the ongoing water crisis in Flint, Michigan. In 2014, the Flint City Council changed the water source to the Flint River, which was contaminated (Pauli, 2020). The new treatment plant did not treat the water correctly, and eventually, the corrosive water ate into individuals’ lead pipes, contaminating the water of Flint’s residents with lead (Pauli, 2020). The population of Flint is 57% Black, allowing the lead contamination to be an environmental justice issue (Martinez, 2016). Exposure to lead can cause neurological development problems in children, memory loss, constipation, abdominal pain, headaches, miscarriages, anemia, kidney and brain damage, and even death (Lead: Health Problems Caused by Lead, 2022).

Frazier immersed herself in the city of Flint for five months while completing this project. Frazier followed three generations of women in a Flint family to document the lives of those affected by the water crisis (Flint is Family, 2019). Select pieces from the photo essay are below (Fig. Xa-Xd). This photo essay was just the start of Frazier’s work in Flint.

Frazier has continued her work in Flint and has helped fund, through the proceeds from her Flint-based show and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the movement of an atmospheric water generator into the city to help solve the water crisis (LaToya Ruby Frazier, 2019). Fraizer is coming out with a new photo book entitled Flint is Family in Three Acts that includes more documentation, interviews with community members, poems, and text. Flint is Family in Three Parts is planned to be released in the summer of 2022.

Through the Eyes of the Crow relates to the work of Flint is Family due to its research base. Within Flint is Family, Frazier presents her research in community narratives time and place-based work, outlining her practice and her choice of subject matter. While initially based on data and science, Through the Eyes of the Crow presents the research behind the project in a more abstract manner. Without seeing data, fact-based statements, or scientific references, the viewer is immersed in the behavior of a crow and how they perceive the threat of personal annihilation firsthand, much as humans are situated within the context of climate change.

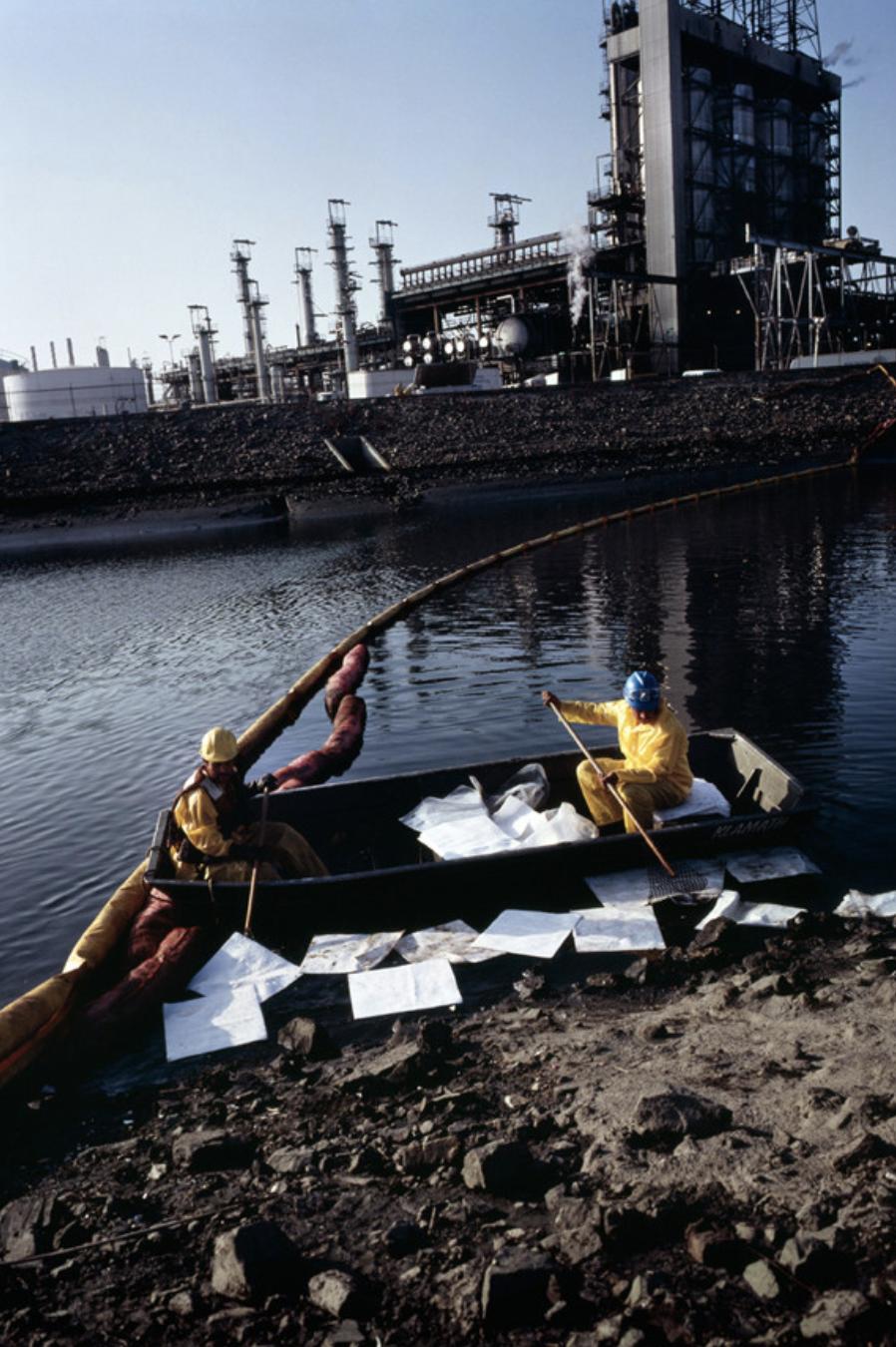

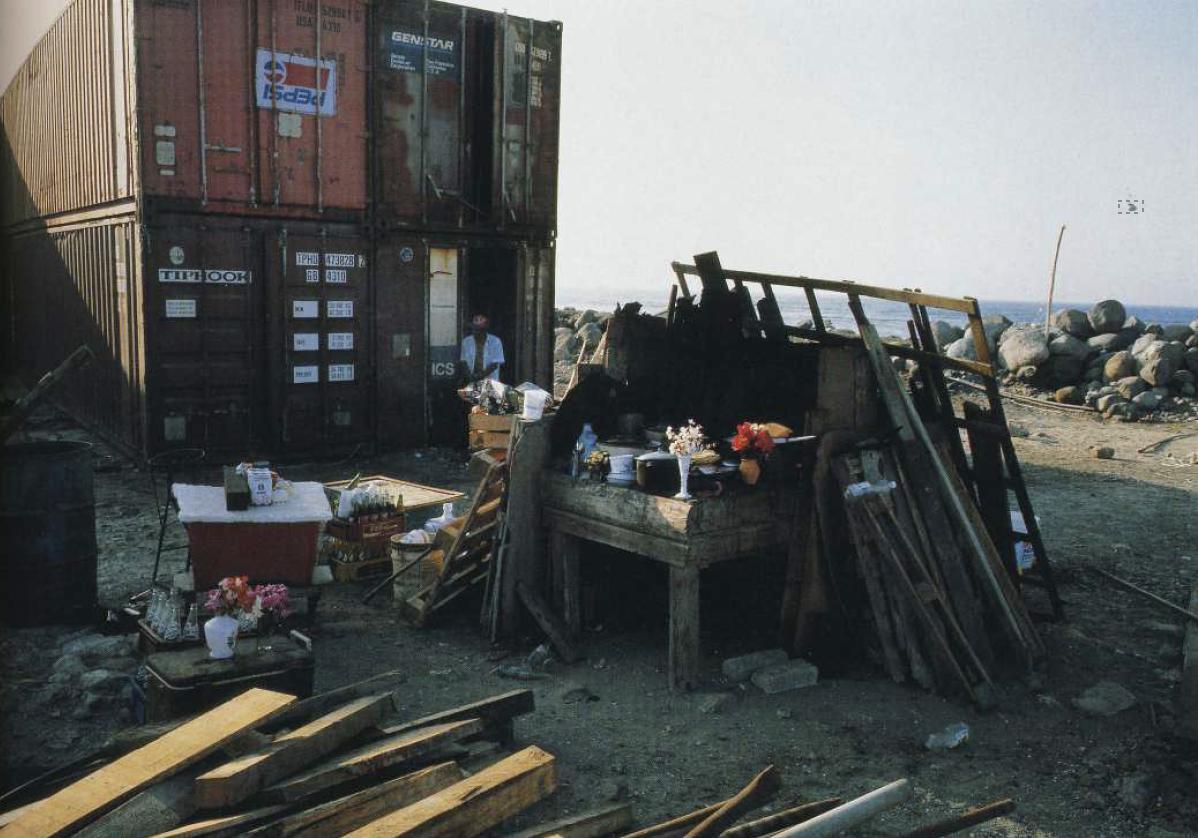

Fish Story by Allan Sekula

Fish Story, written by Allan Sekula in 1995, centers around the story of working-class individuals and labor in an era of globalization. The book includes seven chapters containing 105 color photographs alongside twenty-six black and white text panels (Allan Sekula. Chapter One, Fish Story from the series Fish Story. 1988-95, 2013). Throughout Fish Story, Sekula uses the analogy/storyline of fishing and trade to explain capital globalization and labor exploitation (Sekula and Buchloh, 1995).

Within Chapter One, entitled ‘Fish Story’ Sekula creates “a unique record of unemployment and dilapidation in the old industrial powers, the capitalist pursuit of cheap labor around the globe, and the strenuous work of seafaring” (Allan Sekula. Chapter One, Fish Story from the series Fish Story. 1988-95, 2013).

Chapter Two, “Loaves and Fishes,” explores the position that individuals (sailors and dockers) are under the leadership of politicians like President Ronald Reagan, who demanded that labor be utilized to expand the global supply network on a massive scale (Sekula and Buchloh, 1995).

Chapter Three, “Middle Passage,” dives into the notion of American excellence and theory being labor exploitation of the working class people through citing Engels’s Conditions of the Working Class in England (Engels, 2005) through the continued analogy of the sea:

Engels' narrative begins at sea, in maritime space. A space defined in many of its distinctive features by earlier pre-industrial capitalism, a capitalism based on primitive accumulation and trade. When it was initially seized by the imagination and made pictorial as a coherent and integrated space rather than as a loose emblematic array of boats and fish and waves, maritime space became panoramic. Its visual depiction even today conforms to models established by Dutch marine painting of the seventeenth century. It is in these works that the relationship of ships to cities is first systematically depicted. Obviously, the various historical modes of picturing maritime space should be distinguished from any provisional list of actual maritime spaces: the ship itself, the hinterland, the waterfront, the seaport. breakwaters and seawalls, coastal fishing villages, islands, reefs. The beach, the undeveloped shoreline. The pelagic space of the open sea. the deeps, and so on (Sekula and Buchloh, 1995).

Throughout the narrative, Sekula intertwines theory and fiction, creating a cohesive anti-capitalist narrative that is understandable to the reader. With the text in

conjunction with the photos, a comprehensive understanding of globalization is presented under the disguise of fiction.

Chapter Five, “Message in a Bottle,” discusses Jule Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea regarding the main character, Captain Nemo. Captain Nemo’s treasure, within this context, symbolizes “primitive accumulation” - the source of the original capital and how this eventually created class distinctions (Verne, 1998; Marx, 2022). The photos in this chapter are mainly documenting the working class in Spain.

Chapter Six, “True Cross,” examines the importance and value of materials, such as gold, in trade. Chapter 7, “Dictatorship of the Seven Seas,” concludes Fish Story by discussing leadership and proletariat rebellion and uprising through acts of violence.

Sekula, throughout Fish Story, incorporates anti-capitalism theory from scholars such as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engles into a photo documentary of ‘maritime space’. Tying in fictional maritime characters, such as Captain Nemo, Sekula attempts to break down these theories to the ‘common person,’ spreading the notion of increasing labor exploitation with expanding globalization (both within the United States and across oceans). There is also a beautiful dichotomy between the serene Silver Dye Bleach Print photos of the sea in conjunction with labor exploitation.

While Flint is Family is research-based and presented in strictly photos, Sekula takes a different approach to his work and reveals more of the investigation within his work through citations in his writing. While Through the Eyes of the Crow does not expand upon such a written narrative, an extensive research process was involved in creating the final result. While the work is seemingly about crows, there is a much deeper meaning involved in bringing light to the harms of increasing climate change for crows and the world. Just as Fish Story is not necessarily about the sea, and instead of the promotion of anti-capitalism and the harms of globalization, Through the Eyes of the Crow is more than a narrative about crows. It is a metaphor for the position in which we find ourselves and the decisions we ultimately must make with the data before us, and how these decisions will inform our ultimate survival.

Conclusion

Through the Eyes of the Crow adopts a multispecies perspective, encouraging humans to engage immersively with the crow and understand how fear is perceived, experienced, and acted upon. Influenced by research-based work such as Flint is Family, by LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Allan Sekula’s Fish Story, Through the Eyes of the Crow explains a narrative of the harm of humankind to organisms in the natural world. But more than that, it provides a provocative look at the decisions we can make, should we have the will to survive, that will inform our future direction. Just like the crow learns from death and destruction and uses its intellect to inform future annihilation, could we use the data before us to do the same, should we be so compelled?

Appendix A. → Planning Notes/Sketchbook Pages

Appendix C. → Mask Profiles

Aldhouse-Green, Ancient Gods and Legends 978-0-500-25209-3.

Allan Sekula. . (2013). The Museum of Modern Art; MoMA.

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/164247

Bateman, B. L., Taylor, L., Wilsey, C., Wu, J., LeBaron, G. S., and Langham, G. (2020). Risk to North American birds from climate change-related threats. Conservation Science and Practice, 2(8), e243.

Berman, S. A. (1995). Midrash tanhuma-yelammedenu : an english translation of genesis and exodus from the printed version of tanhuma-yelammedenu with an introduction, notes, and indexes. KTAV Pub.

Bible, K. J. (1996). King James Bible (Vol. 19). Proquest LLC.

Bruchac, M. (2018). Penn Museum Blog | Tlingit Raven Rattle: Transformative Representations. Penn Museum Blog.

https://www.penn.museum/blog/museum/tlingit-raven-rattle-transformative-re presentations/

Carbon, C.-C. (2020). Wearing Face Masks Strongly Confuses Counterparts in Reading

Emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566886

Corvid Research. (2012). Corvidresearch.blog; WordPress.com.

https://corvidresearch.blog/

Debord, G. (2012). Society of the Spectacle. Bread and Circuses Publishing.

Eaton, M. D. (2005). Human vision fails to distinguish widespread sexual dichromatism among sexually “monochromatic” birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(31), 10942-10946.

Engels, F. (2005). The condition of the working class in England (pp. 22-27). Routledge.

Flint Is Family (2019, July 9). LaToya Ruby Frazier.

https://latoyarubyfrazier.com/work/flint-is-family/

Fumo, J. C. (2004). Thinking upon the Crow: The" Manciple's Tale" and Ovidian Mythography. The Chaucer Review, 38(4), 355-375.

Friedlander, G. (1965). Pirke de rabbi eliezer: (the chapters of rabbi eliezer the great) according to the text of the manuscript belonging to abraham epstein of vienna ([2d, American ed.]). Hermon Press.

Gauntlett, D. (2008). Media, gender and identity: An introduction. Routledge.

Hamilton, P. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (Vol. 2). Sage.

Hoylman, B. (2022, January 6). Senator Brad Hoylman and Assembly Member Patricia Fahy Introduce “Dark Skies” Act to Minimize Light Pollution and Protect Migrating Birds. NY State Senate.

https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/brad-hoylman/senator-bra d-hoylman-assembly-member-patricia-fahy-introduce

Humphreys, Brendan (2013). The Battle Backwards A Comparative Study of the Battle of Kosovo Polje (1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) as Political Myths (PhD). University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-10-9085-1.

Jagose, A. (1996). Queer theory: An introduction. nyu Press.

Kanai, M., Matsui, H., Watanabe, S., and Izawa, E.-I. (2014). Involvement of vision in tool use in crow. NeuroReport, 25(13), 1064–1068.

https://doi.org/10.1097/wnr.0000000000000229

Knutsen, R. (2011). Messenger of the Deities. In Tengu (pp. 138-143). Global Oriental.

LaDeau, S. L., Calder, C. A., Doran, P. J., and Marra, P. P. (2011). West Nile virus impacts in American crow populations are associated with human land use and climate. Ecological research, 26(5), 909-916.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. (2019). A creative solution for the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Ted.com; TED Talks.

https://www.ted.com/talks/latoya_ruby_frazier_a_creative_solution_for_the_ water_crisis_in_flint_michigan

Lead: Health Problems Caused by Lead. (2022).

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/lead/health.html#:~:text=Exposure%20to%2 0high%20levels%20of,a%20developing%20baby’s%20nervous%20system.

Martinez, M. (2016, January 26). Flint, Michigan: Did race and poverty factor into water crisis? CNN; CNN.

https://www.cnn.com/2016/01/26/us/flint-michigan-water-crisis-race-poverty/

Marx, K. (2022). Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I - Chapter Twenty-Six. Marxists.org. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch26.htm

Marzluff, J. M., Walls, J., Cornell, H. N., Withey, J. C., and Craig, D. P. (2010). Lasting recognition of threatening people by wild American crows. Animal Behaviour, 79(3), 699-707.

Media Search - eBird and Macaulay Library. (2012). Macaulaylibrary.org.

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=amecroand

mediaType=aandsort=rating_rank_descand__hstc=75100365.0ed3f702b02607

87d5c0d0664eae419e.1646283215152.1646283215152.1646283215152.1and __hssc=75100365.2.1646283215152and __hsfp=220267803and

_gl=1*s4cpx8*_ga*MjM5NDk0NDYzLjE2NDYyODMyMTQ.*_ga_QR4NVXZ8B

M*MTY0NjI4MzIxNC4xLjEuMTY0NjI4NDg1My42MA..#_ga=2.259506627.830 221084.1646283215-239494463.1646283214

Moberly, R. W. L. (2000). Why did Noah send out a raven?. Vetus Testamentum, 50(3), 345-356.

O'Donoghue, H. (2007). From Asgard to Valhalla: the remarkable history of the Norse myths. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pauli, B. J. (2020). The Flint water crisis. WIREs Water, 7(3).

https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1420

Peterschmidt, D. (2017, November 17). Crows, A Bird That’s Not Bird-Brained. Science Friday; Science Friday.

https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/crows-a-bird-thats-not-bird-brained/ Reiter, P. (2001). Climate change and mosquito-borne disease. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109(suppl 1), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.01109s1141

Roorda, A., and Williams, D. R. (1999). The arrangement of the three cone classes in the living human eye. Nature, 397(6719), 520–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/17383

Sekula, A., and Buchloh, B. H. (1995). Fish story (Vol. 202). Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag.

Shrestha, B. G. (2006). The Svanti festival: victory over death and the renewal of the ritual cycle in Nepal. Contributions to Nepalese Studies, 33(2), 203-221.

Strauss, C. L. (1974). Structural anthropology. Persona and Derecho, 1, 571.

Swift, K. N., and Marzluff, J. M. (2015). Wild American crows gather around their dead to learn about danger. Animal Behaviour, 109, 187–197.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.08.021

Tam, B. Y., and Tsuji, L. J. (2016). West Nile virus in American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) in Canada: projecting the influence of climate change.

GeoJournal, 81(1), 89-101.

The Qur'an (E. H. Palmer, Trans.). (1965). Motilal Banardsidass. Van Zoonen, L. (1994). Feminist media studies (Vol. 9). Sage.

Verne, J. (1998). Twenty thousand leagues under the seas. Oxford University Press. View. (2019, June 12). David Gauntlett – Identity Theory. Media Studies @ Guilsborough Academy; Media Studies @ Guilsborough Academy.

https://guilsboroughschoolmedia.com/2019/06/12/david-gauntlett-identity-the ory/#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20theory%3F,but%20just%20reflect%20them %20instead.