CRITICAL

Critical Resistance (CR) was formed in 1997, advocating against the idea that “imprisonment and policing are a solution for social, political, and economic problems” (History, 2018). The main objectives of CR are to halt the construction of new prison/jail developments, push progressive policy, resist state repression, and help individuals understand how life could exist without the prison industrial complex (PIC) and policing systems. CR is funded primarily by grassroots donations (67%) and foundation grants (33%) (Ways to Give, 2022). CR organizes for individuals who are impacted by the PIC, such as individuals who are kept in incarceration facilities for profit, BIPOC individuals who are preyed on unfairly by the United States (in)justice system, and neighborhoods who are displaced by the construction of these institutions. As stated before, CR organizes in ways such as defying jail/prison expansions, advocating for increased connection with incarcerated individuals with their families, and organizing against policies that would increase incarceration rates or injustices. Largely, CR is an abolitionist group focused on humanizing individuals who have been incarcerated and organizing against institutions that have inflicted injustice on these same communities for decades.

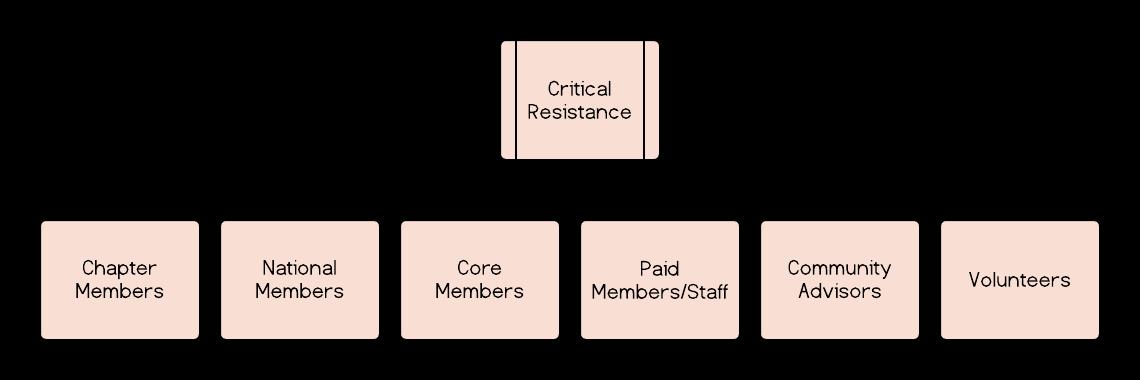

CR identifies itself with a horizontal, member-led structure rooted in pre-figurative politics. Pre-figure politics, broadly, is focused on “participative democracy, horizontality, inclusiveness, and direct action” (Fans, G., 2022). CR is organized by six distinct leadership roles: Chapter Members, National Members, Core Members, Paid Members/Staff, Community Advisors, and Volunteers (Our Structure & Membership, 2022). The Chapter Members are individuals who attend regular CR meetings and work on grassroots campaigns within the main cities where they have chapters (Oakland, Los Angeles, New York, and Portland). The National Members are individuals who do not live in a location with a CR chapter and help with fundraising and conference organization initiatives. The Core Members of CR are individuals who are involved in both the National and Chapter initiatives. Paid Members/Staff are compensated leaders for CR who are considered the “infrastructural backbone of the organization” and act as directors for initiatives and other organizing efforts. Community Advisors are incarcerated individuals, scholars, or experts in the field who provide knowledge to CR, but do not have decisionmaking power. Volunteers are a form of non-paid, nonofficial members who help with more remote organizing for CR, such as phone banking, editing newsletters, and translating materials. Members are individuals who do not live in a location with a CR chapter and help with fundraising and conference organization initiatives. The Core Members of CR are individuals who are involved in both the National and Chapter initiatives. Paid Members/Staff are compensated leaders for CR who are considered the “infrastructural backbone of the organization” and act as directors for initiatives and other organizing efforts. Community Advisors are incarcerated individuals, scholars, or experts in the field who provide knowledge to CR, but do not have decision making power. Volunteers are a form of non-paid, nonofficial members who help with more remote organizing for CR, such as phone banking, editing newsletters, and translating materials.

Looking through CR’s past projects, I came across their Prisoner Radio Project. The Prisoner Radio Project targeted the radio as a form of communication inside the prisons due to the facilities' inability to control the medium as they could with mail and visits Prison Radio Project, 2008). The radio show was broadcasted from 2002 2007 in Oakland, Berkeley, and Fresno. Each show had four parts: short stories about the PIC, the main story, a 15-minute interview segment with the show’s host, and the prisoner mailroom segment. A few of the show’s topics included the criminalization of sex work, alternatives to policing, prison labor and connections to slavery, the globalization of the PIC, and what education looks like inside carceral facilities.

Within the class ‘Community Engagement & Coalition Building,’ taught in the fall of 2022 by Prof. Jaime Stein, we were assigned to read Planning to Stay by William Morrish and Catherine Brown. Planning to Stay provides a framework for organizing within a community, focusing on place and asset based thinking (Morrish & Brown, 1994). Using the framework presented in Planning to Stay, we will analyze CR’s Prison Radio Project to see how closely the concepts work in reality. While there is a disconnect between this project and the neighborhood planning outlined in Planning to Stay, there are still organizing similarities (Morrish & Brown, 1994). Throughout the creation of the Prisoner Radio Project, the organizers went through the following stages discussed in Planning to Stay.

After a communication problem was identified within the PIC, CR organized to work together to create a solution to this issue. CR also gathered around this issue, identifying what kind of communication the PIC had, and then went through the ordering process to visualize the communication system that would allow free speech around prison abolition. Through CR’s envisioning of the Prison Radio Project, they went through the making process, and through the actualization of the issue, the organization took action. While the project is not currently in existence, the radio show lasted five years. To sustain the Prison Radio Project, CR involved prominent abolitionists in the show, such as Angela Davis. To obtain sustainability, CR wanted to include content from incarcerated individuals in the form of poetry, stories, and potential content ideas in the radio show. A drawback of the Prison Radio Project was that it aired once a month and was only a half hour. CR recognized this; if this were to happen again today, they might organize a radio hour that supplemented where the Prison Radio Project fell short.

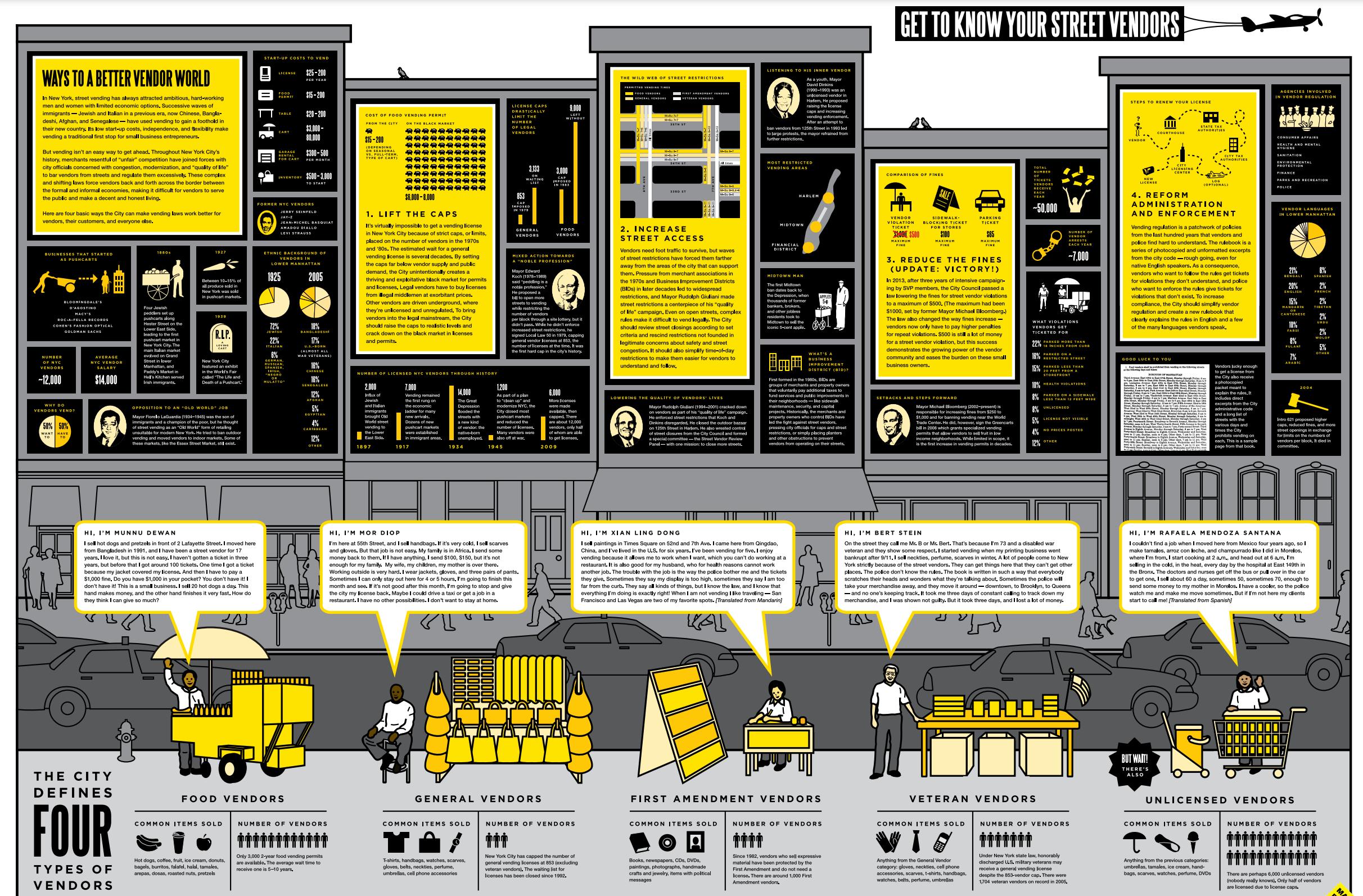

Within the class ‘Community Engagement & Coalition Building,’ an example of effective communication by an organization was Vendor Power, created by the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP: Vendor Power, 2022). Vendor Power, a pamphlet, communicates the rights of street vendors in New York City, an education on the history of street vending, and how to fight/avoid street vending fines.

Using Vendor Power as a reference point for communicative infographics, CR similarly communicates information. In projects such as Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Steps in Policing, CR produced similar infographics using color and symbols to aesthetically portray the impacts of advocating for reformation vs. abolition in the policing system (Reformist reforms vs. abolitionist steps in policing, 2020). This infographic educates the everyday person about how police reform is not the answer to fixing the (in)justice system and rather tries to persuade the reader to think about police abolition.

Another project similar to Vendor Power executed by CR was Prison vs. Princeton (Prison vs. Princeton, 2011). Within the infographic, CR compared the financial costs of a year at Princeton University to the cost of an individual incarcerated for one year. The infographic ultimately conveys that prison spending is much greater than the spending on higher education. The project's conclusion was CR urging the United States of America’s government to fund education rather than the PIC and to re-prioritize our societal values. This is similar to the Vendor Power infographic in that the authors communicate specific statistics to persuade their audience, which was not seen in Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Steps.

8ToAbolition, R. (2014). #8ToAbolition. #8ToAbolition. https://www.8toabolition.com/resources

A Budget to Save Lives, CA COVID 19 Public Health and Safety Budget Immigrant Legal Resource Center ILRC. (2022). Ilrc.org. https://www.ilrc.org/budget save lives ca covid 19 public health and safety budget

Agendatobuild. (2015). Agendatobuild. https://www.agendatobuildblackfutures.com/

carceral tech resistance network. (2022). Carceral Tech Resistance Network. https://www.carceral.tech/

CUP: Vendor Power. (2022). Linkedbyair.net. http://cup.linkedbyair.net/Projects/MakingPolicyPublic/Vendor Power

Fians, G. (2022, March 18). Prefigurative politics. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/prefigurative politics

Freedom to Thrive: Reimagining Safety & Security in Our Communities. (2017, July 5). The Center for Popular Democracy. https://www.populardemocracy.org/news/publications/free dom-thrive-reimagining-safety-security-our-communities

Herskind, M. (2019, July 14). Resource Guide: Prisons, Policing, and Punishment Micah Herskind Medium. Medium; Medium. https://micahherskind.medium.com/resource guide prisons policing and punishment effb5e0f6620

History. (2018). Critical Resistance. https://criticalresistance.org/mission vision/history/

Interrupting Criminalization. (2022). Interrupting Criminalization. https://www.interruptingcriminalization.com/

Kelly, K. (2019, December 26). What the Prison Abolition Movement Wants. Teen Vogue; Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/what is prison abolition movement

Morrish, W. R. & Brown, C. (1994). Planning to stay: A collaborative project. Milkweed Editions.

No New Jails NYC. (2014). No New Jails NYC. https://www.nonewjailsnyc.com/no new jails close rikers now we keep us safe guide

Our Structure & Membership. (2022, August 31). Critical Resistance. https://criticalresistance.org/mission-vision/ourmembership structure/

Prison vs. Princeton. (2011, November 16). Critical Resistance. https://criticalresistance.org/resources/prison vs princeton/

Prison Abolition Should Be the American Dream. (2020). Bitch Media. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/prison abolition should be the american dream

Prison Radio Project. (2008, March 30). Critical Resistance. https://criticalresistance.org/projects/critical resistance radio/

Reformist reforms vs. abolitionist steps in policing. (2020, May 14). Critical Resistance. https://criticalresistance.org/resources/reformist reforms vs-abolitionist-steps-in-policing/

Stanley, E. (2015). Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex. Akpress.org. https://www.akpress.org/captivegenders2.html

Thinking about how to abolish prisons with Mariame Kaba: podcast & transcript. (2019, April 10). NBC News; NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/thinking about how-abolish-prisons-mariame-kaba-podcast-transcriptncna992721

Ways to Give. (2022). Critical Resistance. https://criticalresistance.org/ways to give/

We Came to Learn: A Call to Action for Police Free Schools. (2019, January 29). Advancement Project. https://advancementproject.org/wecametolearn/