Some of life’s greatest joys come on four legs or in little shoes.

This month, we celebrate the laughter, love, and lessons that come from our kids and our pets—the ones who remind us how to live in the moment, greet each day with wonder, and find joy in the simple things.

In these pages, you’ll meet Betty, the unforgettable “C.E.O.” of Healthy Body Healthy Soul—a rescue dog whose story is nothing short of miraculous. Her journey will warm your heart and remind you that second chances are always possible.

You’ll also find a dash of end-of-summer sweetness in “Summer Is for Popsicles” with refreshing popsicle recipes perfect for lazy afternoons with friends and family. And in “Whisking Up Confidence,” we explore how cooking with children is far more than just making meals.

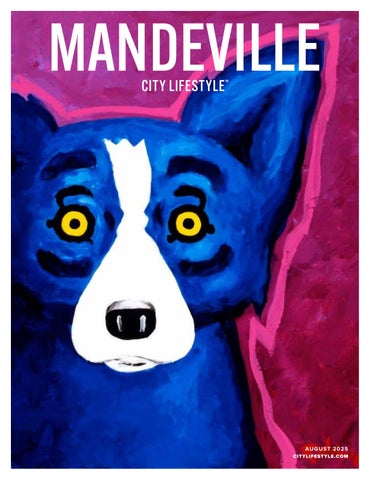

Our feature story, “Rhapsody in Blue {Dog},” takes a contemplative turn with a look at the life and art of Louisiana’s own George Rodrigue. His iconic Blue Dog has not only become a symbol of the South and a global pop icon, but it has also touched the hearts of art lovers across the globe, including those of us right here in Mandeville.

As always, our Business Monthly and Events Calendar connect you to the people, businesses, and happenings that make our community shine.

Whether you’re chasing toddlers, chatting with grandchildren, walking the dog, or savoring the final days of summer, may this issue inspire you to slow down, look around, and hold close the ones—furry or otherwise—who make life sweet.

REBECCA GEORGE & CHRISTIAN GEORGE , PUBLISHER & CO-PUBLISHER @MANDEVILLECITYLIFESTYLE

PUBLISHER

Rebecca George | rebecca.george@citylifestyle.com

CO-PUBLISHER

Christian George | christian.george@citylifestyle.com

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Christian George, Bailey Hall, Angela Broockerd, Linda Ditch

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Rodrigue Studios, Janie Jones, Allyson Lipari, Daphne Frilot, Abby Sands

CEO Steven Schowengerdt

COO Matthew Perry

CRO Jamie Pentz

VP OF OPERATIONS Janeane Thompson

VP OF SALES Andrew Leaders

AD DESIGNER Matthew Endersbe

LAYOUT DESIGNER Lillian Gibbs

QUALITY CONTROL SPECIALIST Hannah Leimkuhler

Located at 2130 Monroe Street, Monroe Street Animal Hospital is dedicated to providing compassionate care for pets at every stage of life. Led by Dr. Paige Massey and Dr. Alissa Whitney, the hospital offers grooming, boarding, diagnostics, and comprehensive veterinary services in a low-stress, Fear Free environment. With techniques to reduce anxiety and fear, Monroe Street Animal Hospital ensures happier, healthier visits for your pet. Schedule your appointment today by calling (985) 629-4075.

Scan to read more

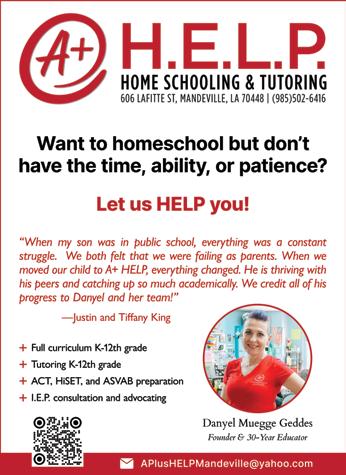

A+ HELP Mandeville offers customized homeschooling for K–12th grade, led by a Special Education teacher with 30 years of experience. With small, instructor-led classes and individualized learning plans, A+ HELP welcomes students of all academic levels and educational needs. The mission of A+ HELP is to build confidence, inspire a love of learning, and help every child thrive in a nurturing environment. Learn more about how A+ HELP can support your family at aplushelp.net.

As part of its 175th anniversary, Our Lady of the Lake Roman Catholic Church is unveiling in Mandeville City Lifestyle a special focus on ten stained glass windows depicting the arc of salvation. Each month, the church invites readers to scan the accompanying QR code for a curated audio tour of each window. Designed by Franz Mayer of Munich in the 1950s, these windows illuminate the gospel—each one a homily in glass and grace. Scan

At Covington Trace ER & Hospital, we are redefining the emergency room experience. With a state-of-the-art facility and advanced medical technology, we ensure that every aspect of your experience is tailored to meet your needs. Our personalized care plans, coupled with compassionate service, allow you and your loved ones to feel better—quickly and comfortably. Find 24/7 care, minimal wait times, and rapid, accurate onsite imaging and laboratory services. Discover the care you deserve when you need it most.

We accept all commercial insurance. According to the No Surprise Act, emergency visits are covered regardless of our network status.

ARTICLE BY CHRISTIAN GEORGE

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

ALLYSON LIPARI,

DAPHNE FRILOT, ABBY SANDS

Some stories feel written by fate. This is one of them. On the evening of Sunday, October 1, 2023, Daphne Frilot and Faith Joubert of Healthy Body Healthy Soul lost their dear friend and client Betty Bruce to cancer. Fourteen hours later, on Faith’s usual Monday morning drive to the hospital, she spotted what looked like a discarded stuffed animal on the roadside.

“Betty is more than our mascot. She is our heart, our beloved C.E.O. ... our treasure.”

For reasons she still can’t explain, Faith stopped the car, glanced in the rearview mirror, and noticed the “toy” was moving.

She backed up, got out, and saw her: an emaciated little dog with filthy fur and exhausted eyes.

“I can’t pick you up right now,” Faith told her softly. “But I promise I’ll be back.”

She called Daphne immediately. Daphne rushed to the spot, found the frail dog, and carried her to the nearest shelter, giving a donation to ensure her care.

Before Daphne even arrived, the name “Betty” had come to her mind. When she returned to the center, Annie, one of their intuitive Reiki practitioners, heard the story and immediately said, “Well, that’s Betty.”

Hours later, Cindy, their other Reiki master, echoed the same thought without ever hearing Annie’s words.

At first, practicality prevailed. Faith and Daphne didn’t need a dog in the center.

But they were hooked. Daphne visited Betty every day. At the shelter, they called her “Legs” because she dragged her little hind legs behind her. She was four pounds of fur and fleas and likely suffering from spinal injury—partially paralyzed and incontinent.

The shelter was quietly considering their options.

On October 9, though, the shelter allowed Faith and Daphne to bring her home. They immediately brought her to the center’s therapeutic energy room.

They tried trips outside, but Betty’s incontinence remained. Thank goodness for doggie diapers, which they discovered two days later. Everyone said she’d likely never walk again.

But they didn’t know Betty.

By October 14, she’d spent hours in the therapeutic energy room and had earned her own medallion. By October 17, she was climbing dog gates with her front legs and running in the yard.

With her new pack, and lots of love to go around, Betty became a Facebook and Instagram star—and the center’s most enthusiastic greeter.

Since then, Betty has continued to thrive in the therapeutic energy of the EE System. She has regained some bladder control, doubled her weight to eight pounds, and become fast, strong, and adored by everyone who meets her. She travels with Faith and Daphne, has flown on airplanes, and has sniffed the red rocks of Sedona and the ocean air of Miami.

And on October 9, 2024, Faith and Daphne celebrated her “rebirthday”—the day her life began again.

Betty is more than Healthy Body Healthy Soul’s mascot. She’s their heart, their beloved C.E.O. (Chief Encouragement Officer), and most importantly, their unexpected treasure. And like all the best stories, hers continues to unfold.

Ask for Betty when you visit Healthy Body Healthy Soul for movie night. She’ll be there— ready to greet you, ready to heal you, ready to lick you, ready to love you.

To learn more about Healthy Body Healthy Soul, or to experience the EE Light System for yourself, you can reach Faith and Daphne by email at info@healthybodyhealthysoul-la.com , by phone at 985-898-9445, or through their website at healthy bodyhealthysoul-la.com. You can also find them on Facebook ( Healthy Body Healthy Soul LA) and Instagram (@healthybodyhealthysoulla). Or, simply stop by in person at 220 Park Place, Suite 300, Covington, LA 70433. All are welcome!

ARTICLE BY ANGELA BROOCKERD | PHOTOGRAPHY BY JANIE JONES

There’s something truly special about inviting your child into the kitchen—not just for the cookies or cupcakes, but for the confidence, creativity, and connection that come with it. Cooking with your children isn’t just a fun way to pass the time; it’s an opportunity to build lifelong skills and memories that stick.

Sure, teaching a young child how to crack an egg or measure flour can test your patience—but hang in there. With a little trial and a fair amount of error, they’ll start to develop the fine motor skills that allow them to prep a recipe all on their own one day. The best part? They’ll gain confidence along the way, one scoop, stir, and sprinkle at a time.

Cooking together also taps into something a little magical—memory. The smell of cookies baking or chili simmering on the stove can instantly transport us back to childhood. That’s not just nostalgia talking—science backs it up. Our sense of smell is closely tied to autobiographical memory, especially memories formed early in life. So those sweet, savory scents? They’re more powerful than you might think.

The key is to start simple. Let your toddler play with mixing bowls, spoons, and measuring cups. These little moments of pretend play actually help build the fine motor skills needed for real kitchen tasks. Begin with small jobs—scooping flour, flattening cookie dough with a rolling pin—and gradually add more steps as your child becomes more confident.

It won’t be perfect. The flour might fly, the sugar might spill, and the measurements might be slightly off—and that’s okay. Embrace the mess, stay patient, and focus on the fun. A dash of encouragement and a sprinkle of praise go a long way in keeping your little chef engaged and excited.

Over time, you’ll see the magic unfold: a child who’s not only learning how to cook but also growing more independent, capable, and proud of what they’ve created. And who knows? Maybe one day, they’ll pass those same recipes—and memories—on to their own kids.

CONTINUED >

• 1 cup and 2 tablespoons white flour

• 1/4 teaspoon baking soda

• 1/2 cup oatmeal

• 4 tablespoons honey

• 1/2 teaspoon vanilla

• 4 tablespoons buttermilk

• 1/2 teaspoon almond extract

• 1/4 teaspoon salt

• 1/4 cup whole wheat flour

• 1/4 cup unsalted butter, room temperature

• Optional: add 1/4 teaspoon nutmeg or cinnamon

CONTINUED >

1. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees.

2. Put the oatmeal in a blender or food processor and pulse for about a minute, until it’s reduced to a rough powder. Add the ground oatmeal to the whole wheat and 1/2 cup of the white flour, baking soda and salt to the bowl of an electric mixer affixed with a paddle attachment, and turn on to mix. Add butter and blend on medium speed until the butter has been incorporated and the mix looks a little like wet sand. Add the buttermilk, vanilla, honey and almond extract and blend. If the dough looks too wet to roll, add the remaining flour 1/4 cup at a time until the dough forms a ball and pulls away from the sides of the blender.

3. Turn the dough out onto a piece of plastic wrap and flatten into a disc. Cover completely and chill in the fridge for at least one hour, up to overnight.

4. When ready to bake, preheat the oven to 400 degrees and place dough on a lightly floured surface (using the remaining 2 tablespoons of flour). Roll out until 1/8 inch thick. Cut out with desired cookie cutters and bake for five to seven minutes, based on your preference. Five minutes will get you a softer cracker, while seven will get you a crisp cracker.

Enjoy!

George Rodrigue,

ARTICLE BY CHRISTIAN GEORGE PHOTOGRAPHY BY RODRIGUE STUDIOS

By now, no vision of Louisiana—or the broader American canvas—feels complete without George Rodrigue’s Blue Dog gazing back at us with those unblinking, iconic eyes.

With over four thousand paintings to its name, Blue Dog slipped the Louisiana leash and roamed far beyond the bayou of its birth. From New York to Tokyo to Venice, the cobalt canine broke all the rules—lounging in presidential suites, curling up in French palaces, chasing down Berlin buses, and leaving luminous paw prints across the pages of The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal , and People.

No longer just a Southern symbol, America’s beloved dog strutted into pop royalty. Equal parts myth, muse, and media darling, it photobombed the likes of Jimmy Buffett, Sylvester Stallone, and Drew Brees.

Even Friends couldn’t resist. Season Six, back wall of Central Perk, hanging there like he owns the lease and knows the punchlines.

Rodrigue’s dog, unbothered and electric as ever, escaped the canvas and padded straight into legend. And in 2008, it made its boldest leap yet—blasting into orbit aboard NASA’s space shuttle Endeavour, tail wagging like the cosmos had always been the plan.

But who was George Rodrigue? How did a classically trained Cajun artist become the mind behind the masterpiece? And how did a scrappy studio sidekick named Tiffany evolve into one of the most recognized icons of American pop art?

To find out, I meet up with Jacques George Rodrigue— son of George and now the keeper of his father’s legacy—at Coffee Rani in Mandeville, hoping to trace the origin story of the dog that stared its way into our history and hearts.

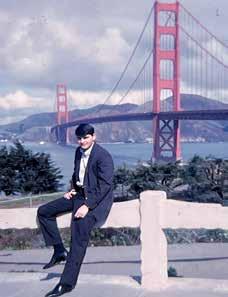

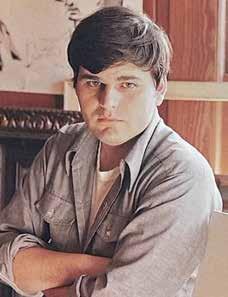

George Rodrigue was born in 1944 in New Iberia, Louisiana, to a Parisian mother and a Cajun father who built tombs from brick and mortar. His childhood was steeped in bayou flavor—Spanish moss, Sunday Mass, and the quiet tug-of-war between two cultures. At home, the family spoke French. At school, it was punished.

In third grade, polio left Rodrigue quarantined for nearly a year, bedridden while the world carried on outside his window. To pass the time, his mother brought sculpting clay, then a paint-by-numbers kit of The Last Supper Rodrigue flipped the canvas over and began painting without

instructions. No lines. No rules. Just instinct. And inside that room, suspended between illness and stillness, something sparked.

His earliest sketch—a turkey, signed with a mysterious question mark—hinted at the signature spirit to come.

At Catholic high school, he kept drawing. “Stand up, George!” his civics teacher often barked. “How many times have I told you— you’ll never amount to anything with that drawing.”

After a few semesters at the University of Southwestern Louisiana, Rodrigue packed his paints and pointed west. He’d been accepted into the ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles, one of the most prestigious art schools in the country. He had no money. No place to stay. But he’d been given a chance. In Los Angeles, he trained in the classical technique: form, shadow, composition, control. This was the late 1960s. Vietnam. Woodstock. Revolution in the streets. But Rodrigue remained largely untouched by the era’s noise. A quieter kind of shock stirred him more deeply: his classmates had never even heard the word Cajun .

What he’d assumed was common—gumbo, French, zydeco, boudin—suddenly felt rare and fragile. Endangered even. Then came Warhol.

Rodrigue wandered into the Ferris Gallery and saw pop art’s rebellion firsthand—soup cans, repetition, bold color, commercial edge. His professors rolled their eyes, but Rodrigue leaned

in. The idea that art could be iconic and accessible to everyone might strike a nerve, but it also struck a chord.

After a brief stint in New York, tragedy called him back. His father passed away unexpectedly at sixty-five. Rodrigue returned to Louisiana for the funeral and never left again.

“He wanted to capture what he felt was his dying culture,” Jacques tells me. “And he knew he couldn’t do that from anywhere else.”

When Rodrigue came home, he didn’t paint what Louisiana looked like, he painted what it felt like.

His early landscapes were shadow-soaked: thick trunks, deep browns, soil-washed greens. Unlike the wide, hopeful skies of European renderings of Cajun Country, Rodrigue pushed the horizon line high, cropping the trees before their crowns. No open expanse. No escape. Just exile beneath a heavy canopy of oak limbs.

“This is what I wanted to show,” he said. “The pain, the suffering of all these people.”

In the 1950s, Louisiana schools banned French. Cajun culture was slipping away, and Rodrigue sensed what was happening: a quiet erasure of a people and their past. So he made the oak tree his anchor—his own Campbell’s soup can.

“It represented protection,” Jacques explains. “It’s where the Cajuns found shelter.”

Rodrigue returned again and again to the Evangeline Oak in St. Martinville, named for the heroine in Longfellow’s 1847 poem Evangeline, a tale of Acadian lovers lost during the 1755 expulsion from Nova Scotia.

Look closely at his early works. Rodrigue’s figures stand beneath the branches, clearly in the shade but never shadowed. Why? Because George didn’t want the sun to light his exiled subjects; their light source was more hidden, internal. What Rodrigue called “the hope of a culture trying to survive in a new world.”

And in those early Lafayette days, Rodrigue needed a strong dose of hope too—especially when he was selling paintings from the trunk of his car to two or three buyers a month. Money was tight, but when clients couldn’t pay, he bartered, trading paintings for shoes and tire rims.

No museum was interested. The art world barely looked his way. But Rodrigue kept painting. “It wasn’t the yes that fueled him,” says Jacques. “It was the no.”

In 1970, Rodrigue landed his first big break: an exhibition of nearly fifty works at the Louisiana State Museum in Baton Rouge.

The show was filled with his signature dark landscapes—deep oaks, heavy branches, shadowed ground. Rodrigue was just finding his voice, and for the first time, someone outside his circle was coming to hear it.

The Baton Rouge Advocate sent Ann Price, an art critic, to cover the show. Rodrigue was thrilled—his first professional review!

Beside himself with excitement, he opened the newspaper to read her headline:

“Painter Makes Bayou Country Dreary, Monotonous Place.”

Price described his work as “shadowy, depressing,” “flat and drab,” with “none of the life and color that pulses there.”

It crushed him.

But it also drove him deeper into his own vision—one rooted not in public approval but cultural memory.

Rodrigue never forgot the sting of that first critique. In her 2013 book The Other Side of the Painting, his second wife, Wendy, wrote, “The experience gave him self-confidence, and in twenty years, I have yet to see George rattled by negative remarks or criticism.”

The following year, in 1971, Rodrigue painted one of his most beloved works: The Aioli Dinner—a kind of Cajun Last Supper inspired by a faded photograph of his grandfather’s dining club. “It was my way of documenting two hundred years of Cajun culture,” he said. He never sold it.

The Blue Dog began, as legends often do, with something small and scruffy.

Her name was Tiffany. Rodrigue’s first wife, Veronica, brought her home as a puppy, a mix of English Cocker Spaniel and terrier. “Kind of smart, kind of bad,” she once said, laughing. Tiffany

“I fed that dog for ten years. Now the dog is feeding us.”

—GEORGE RODRIGUE

would curl up beside Rodrigue’s easel, always slightly askew, one hind leg kicked out at an angle.

Rodrigue began photographing her—not from above, but eye to eye. He crouched, meeting her gaze head-on. That simple, instinctive choice became everything. The stare wasn’t playful. Wasn’t pleading. It was something else entirely: alert, unblinking, and oddly eternal.

By 1984, Rodrigue had become something of Louisiana’s unofficial state artist. That year, he was commissioned to illustrate Bayou , a collection of Cajun ghost stories for the New Orleans World’s Fair. One tale, the legend of the loup-garou , the mythical werewolf said to haunt the bayous, led him back to Tiffany.

Beneath imagined moonlight, Rodrigue painted her fur the color of dusk—cold, spectral, somewhere between slate and silver. With red glowing eyes, it was a haunting but accurate depiction of the Cajun folklore.

In 1988, he brought these paintings to an exhibition at the Upstairs Gallery in Beverly Hills. Somewhere in the room, he overheard a visitor mutter: “What’s with the blue dog?”

The name stuck.

Returning home, he painted a towering version—seven feet tall— on a yellow background and called it Loup-Garou. It was the first painting he’d made in more than two decades without a landscape.

Then came the boldest move of all: he opened Rodrigue Studios in the French Quarter at the corner of Royal and St. Louis and filled it with nothing but Blue Dogs

And just like that, Blue Dog had a name, a home, and a life of its own.

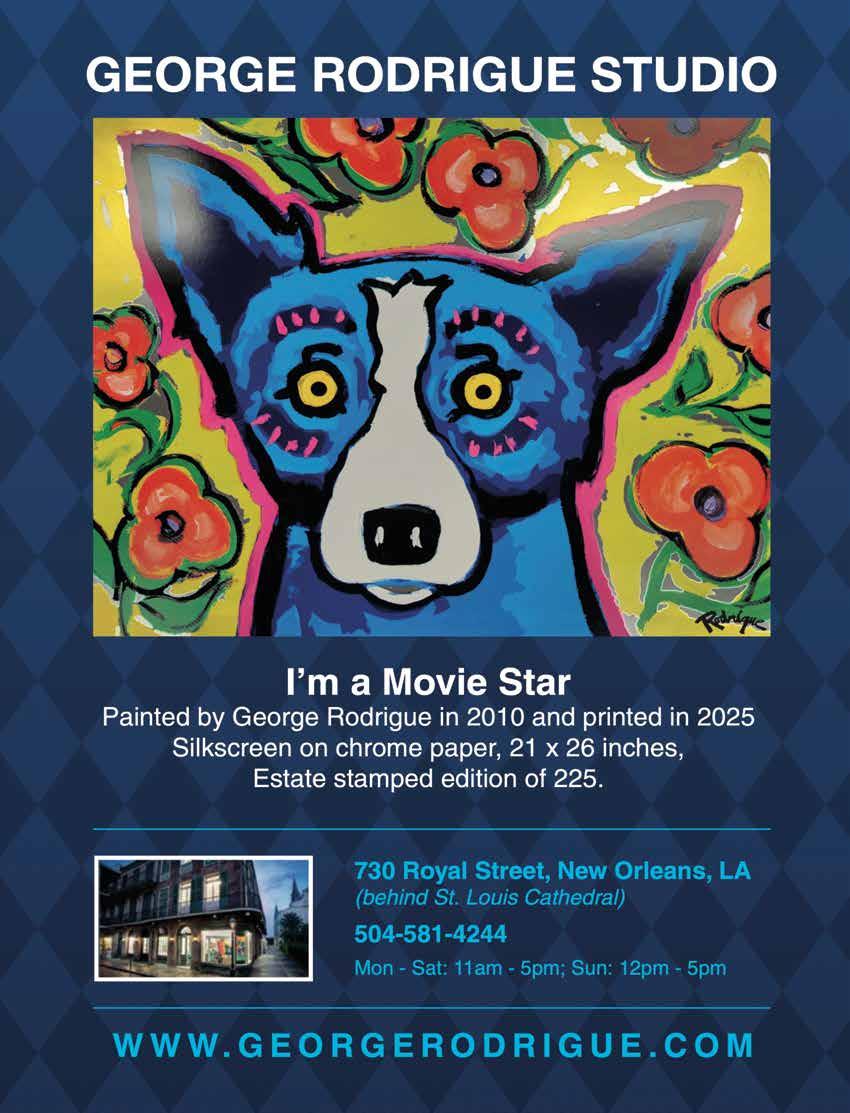

Top: I'm a Movie Star by George Rodrigue, 2010

Middle Left: Blue Dog Saint by George Rodrigue, 2006

Middle Center: Kiss Me I'm Cajun Too by George Rodrigue, 1992

Middle Right: Handle My Heart with Care by George Rodrigue, 1995

Bottom Left: The Dukes of Dixieland by George Rodrigue, 2013

Bottom Right: Life's a Blast by George Rodrigue, 2001

Would Blue Dog be a fleeting trend? A hot minute in the media?

On March 5, 1992, the answer was a loud “Not a chance.” The Wall Street Journal ran a story titled How Many Dogs Can Fetch Money? An Artist-Alchemist Turns a Blue Pooch Into Gold . And suddenly, Blue Dog wasn’t just a curiosity—it was a phenomenon. Gone were the days of hanging paintings anywhere that would take them. Now, the art world had finally perked up. “I fed that dog for ten years,” he liked to say. “Now the dog is feeding us.”

In 2007, the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis hosted a major retrospective of his work. It caught the attention of the New Orleans Museum of Art, which followed with a full-scale exhibition in 2008, the largest of Rodrigue’s career.

Then the brands came calling. Absolut Vodka. Xerox. Neiman Marcus. Rodrigue’s work slipped into national ad campaigns, and his collectors list grew starrier. Stallone. Schwarzenegger. Blue Dog became as bankable as it was beloved.

Even the White House wanted in. Rodrigue was commissioned to paint portraits of President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. In classic fashion, he tucked a Blue Dog into the frame.

Across four decades, Rodrigue’s cobalt muse carried him from small-town obscurity to international acclaim. Named Louisiana’s official Artist Laureate, featured on NBC’s Today

Show and CBS Sunday Morn ing, his Blue Dog creations—part fine art, part pop artifact—reflected his uncanny gift for creating images that refused to be forgotten.

“There was something about George, this very unique spirit about him,” says Emeril Lagasse. “It was infectious.”

Jacques echoes the sentiment. “His laugh could fill a room before he even entered it.”

His father was nocturnal by nature. “Like a vampire,” he says. “He painted through the night and slept until noon. Worked best when the world was quiet.”

While wielding his brush, he often rested his hand on an Arthurian-looking sword he’d unearthed as a child, a gleam of ornate metal beside the easel.

His method was precise and personal. He began with photographs, always his own, projected faces onto canvas, sketched the outline, then applied the paint.

When Rodrigue painted Blue Dog, he followed a template, sure. But the results never felt formulaic. Bold backgrounds. Surreal props. Shifts in color or expression. He leaned in and withdrew, toggling glasses, adjusting small details until they clicked. The eyes came always last.

“The pupils were everything,” says Jacques. “They were the soul.” Rodrigue thrived on experimentation—oils, silkscreen, even

early Photoshop. Yet the essence never changed: a solitary man in silent vigil, painting a dog who always stared and never blinked.

James Michalopoulos, one of his contemporaries, once noted Rodrigue’s rightful place beside Andy Warhol. “Rodrigue was a pioneer,” he said, “a cultural alchemist harnessing Bayou Surrealism with every brush stroke.”

Constellations of accolades surrounded him. And even Ann Price—whose cutting review Rodrigue could still recite by heart—had gotten one thing right: “He shows some competence as a painter,” she wrote, “particularly with his use of light.”

That light came from within. It was the beacon that kept him painting, kept him chasing the fading echoes of a culture he refused to let disappear.

Rodrigue wasn’t just an artist. He was, in the words of Jacques, “someone who believed in leaving things better than he found them.”

That belief shaped not only his paintings but his philanthropy. He quietly paid tuition fees for students, helped struggling families, and gave away cars to those in need.

When Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, Rodrigue rushed home from Texas to help his staff. Alongside Wendy and Jacques, he hauled paintings out of flooded studios, salvaging what he could.

For a time after, he couldn’t bring himself to paint. The exile, the loss, the aching silence—it hit too close.

Then he found a way through, painting We Will Rise Again : a Blue Dog submerged in water, rising.

The image raised over half a million dollars for the Red Cross. But more than that, it became a symbol of resilience. Not a portrait of what New Orleans was, but as Rodrigue believed, what it could be: bruised but unbroken. A truly New Orleans.

“It didn’t take me long to realize what a legend George Rodrigue was,” said Drew Brees, “and what a legendary story Blue Dog is.”

That spirit—of art as a lifeline—lives on through the George Rodrigue Foundation of the Arts (GRFA), founded by Rodrigue in 2009 to support arts education across Louisiana. Through scholarships, teacher resources, and George’s Art Closet, which provides free supplies to schools, the foundation has touched the lives of thousands.

“To be studied by a child,” he once said, “is more important than hanging on the walls with the great masters.”

Today, his sons Jacques and André continue GRFA’s mission and operate Rodrigue Studios in New Orleans and Lafayette. The galleries showcase their father’s work exclusively, carrying forward not only his images but his legacy, his belief that art can change the story we tell about ourselves and the place we call home.

On December 14, 2013, at the age of sixty-nine, Rodrigue succumbed to his long battle with cancer, likely the cost of years spent breathing varnish and oil paint.

But the colors remain. And today, Blue Dog burns brighter than ever, immortalized in the new PBS documentary Blue: The Life and Art of George Rodrigue. Rodrigue’s legacy continues not only on screen, but also on the walls of the Cabildo in New Orleans, where a landmark exhibition invites visitors to step directly into his world. In life, he gave us portraits of exile and hope. In death, he left behind something rare: a rhapsody in blue.

I took the tour myself and walked away feeling reflective, questioned in all the right ways.

To stand before an original Rodrigue, and not merely a print, is like looking into a mirror, seeing yourself with new eyes. But it’s also like gazing through a window onto a brighter world—where the horizon sits lower, and above it, the sky stretches wider, more open and endless than before.

Like a myth made modern, Blue Dog still peers at us from the canvas. Never smiling, never moving, Blue Dog simply stares—almost startled at what it sees happening on our side of the canvas.

Blue Dog doesn’t offer answers. Only questions. Who am I? Who are you? What are we doing here?

What’s life all about?

“The best thing about Blue Dog,” Jacques explains, “is that everyone sees something different. Blue Dog lives in people’s homes, in people’s hearts.”

Untitled by George Rodrigue, 2011

“It didn’t take me long to realize what a legend George Rodrigue was, and what a legendary story Blue Dog is.”

—Drew Brees

Like fast-drying acrylic, Blue Dog sparks an immediate connection with us, one that’s instant, direct, and unmistakable.

But like oils that never fully dry, there’s a freshness woven into the fur of its immortality. As if, for the briefest second, we’ve caught Tiffany off guard, and both of us are there staring at each other, suspended in the paradox of a fleeting, eternal moment.

Blue Dog has transcended the lines we so often draw, belonging to no one. And yet, enchantingly, it belongs to everyone willing to look through its bright yellow, ever-asking eyes.

In that sense, Blue Dog will never fall out of fashion. And neither will Rodrigue—the Cajun artist who, with the bravest of brushstrokes, gave us a story worth remembering and a legacy worth preserving.

“You’ll never meet another human being like George,” says Emeril Lagasse. “He’s still painting somewhere.”

To learn more, visit GeorgeRodrigue.com, RodrigueFoundation.org, George Rodrigue Art on Facebook, @George_Rodrigue on Instagram, and George Rodrigue (@RodrigueStudio) on YouTube.

If you own an original Rodrigue painting, please contact Jacques Rodrigue, who is preserving his father’s work in a digital archive. The documentary Blue: The Life and Art of George Rodrigue is streaming on the PBS Passport app, your local PBS affiliate, or broadcasts. Check listings at wlae.com/rodriguebluedogfilm/watch. The exhibition Rodrigue: Before the Blue Dog is open at the Cabildo in New Orleans until September 28.

When disaster strikes, we show up for each other. Flooding across Texas has uprooted families and disrupted daily life across entire communities but hope is never far when neighbors come together City Lifestyle is identifying those most affected and helping deliver real support where it’s needed most.

KNOW SOMEONE IMPACTED?

Nominate a family, individual, or local leader in need of care and restoration. our voice can help us reach the people who need support the most

ARTICLE BY LINDA DITCH PHOTOGRAPHY PROVIDED

As temperatures rise, children race to the freezer for this frosty treat or wait anxiously for the approach of the musical ice cream truck. Making homemade popsicles is a fun, kidfriendly activity. These recipes feature kid-favorite flavors with an added taste twist. The only tricky part is waiting for them to freeze.

ingredients:

Makes 18 to 24

• 2 quarts Concord grape juice

• 1/2 cup sugar

• 12 whole cloves

• 4 cinnamon sticks

• 3 tablespoons whole allspice

directions:

Put all of the ingredients into a large saucepan. Bring the mixture to barely a simmer and let it cook for 30 minutes. Remove from the heat and pour the juice through a cheesecloth-lined strainer into a bowl or pitcher to remove the spices. Allow the juice to cool to room temperature, and then refrigerate until well chilled. Pour mixture into popsicle molds. Freeze until firm.

Makes 18 to 24

• 2 cups sugar

• 2 cups water

• 1 cup lime juice

• 2 cups tart cherry juice

directions:

In a saucepan, combine the sugar and water over medium heat, stirring until the sugar dissolves. Remove from the heat. Add the cherry juice and taste. Add additional sugar or water if needed. Let come to room temperature and then refrigerate until well chilled. Pour mixture into popsicle molds. Freeze until firm.

AUGUST 1ST

COOLinary: A Celebration of Dining in America’s Most Delicious City

Restaurants Throughout New Orleans | 11:00 AM

Enjoy specially curated, multi-course meals at unbeatable prices during COOLinary New Orleans, August 1–31. Dozens of top restaurants offer prixfixe lunches starting at $28 and dinners or brunches for $58 or less. It’s the perfect time to indulge in New Orleans’ finest cuisine and check off your summer food wish list in true Crescent City style.

AUGUST 15TH

Online | 6:00 PM

Join Dr. Jerry Pounds of Concierge Counseling of Mandeville for “Fair Fighting,” a practical, insightful, and relaxed online seminar helping couples resolve conflicts and communicate more effectively. Held Friday, August 15, 2025, from 6:00–8:00 PM CDT with recorded replay available. Early bird pricing: $57 per couple. Limited spaces. Register now to strengthen your marriage from the comfort of home.

CONTINUED

AUGUST 16TH

Covington White Linen for Public Art

409 E. Boston St., Covington | 6:00 PM

Celebrate the end of summer at Covington White Linen for Public Art, Saturday, August 16, 2025, from 6–9 PM. Enjoy live music, art demonstrations, shopping, dining, and strolling through downtown Covington in your finest white attire. Local businesses donate a portion of sales to the Covington Public Art Fund. Free and family-friendly. Visit covingtonpublicart.org for details.

AUGUST 16TH

Q50 Races “Bleau Moon” 5 & 10 Miler in Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau State Park | 7:45 PM

Run under the stars at the Q50 Races “Bleau Moon” 5 & 10 Miler, Saturday, August 16, 2025, at Fontainebleau State Park. This unique nighttime trail race along Lake Pontchartrain starts at 7:45 PM. Proceeds benefit the New Orleans Mission. Spectators welcome. Headlamps required. Register at ultrasignup.com or visit q50races.com for details.

AUGUST 22ND

American Legion Banana Split Celebration

Inaugural Yellow Tie Gala

2031 Ronald Reagan Hwy, Covington | 6:00 PM

Celebrate Great American Legion Banana Split Celebration at the inaugural Yellow Tie Gala, Friday, August 22, 2025, 6–10 PM, at American Legion Post 16 in Covington. Enjoy a catered buffet, open bar, and live big band music. Wear your brightest yellow! Proceeds benefit scholarships and community programs. Tickets $50. For details, visit northshorefoodbank.org.