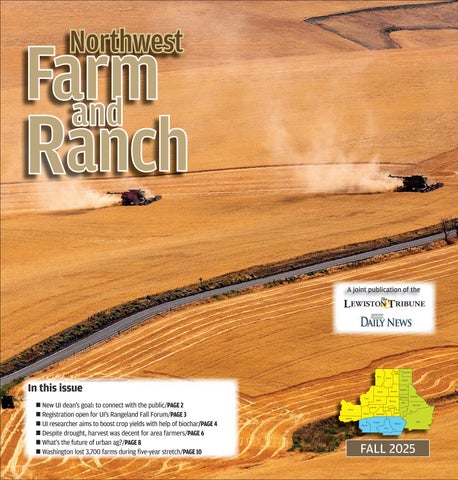

In this issue

New UI dean’s goal: to connect with the public/PAGE 2

Registration open for UI’s Rangeland Fall Forum/PAGE 3

UI researcher aims to boost crop yields with help of biochar/PAGE 4

Despite drought, harvest was decent for area farmers/PAGE 6

What’s the future of urban ag?/PAGE 8

Washington lost 3,700 farms during five-year stretch/PAGE 10

Leslie Edgar, who grew up on an Idaho farm, wants UI’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences to engage with the public

By Kathy Hedberg Farm & Ranch

Leslie Edgar, the new J.R. Simplot endowed dean of the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Idaho, is eager to make connections between the public and the mission of her school.

“I’m spending a lot of time traveling on a listening tour,” Edgar said during one of the few moments this summer she was back in her office in Moscow.

“I’m talking to stakeholders, agriculture producers (and others) to hear what their needs are. I’m spending a lot of time listening and over the next few months will be transitioning to a vision to inform (the public) on a strategic plan for our college to help support Idaho.”

Edgar served as head of the college for nine years. She has a long and varied career as an agriculture communicator, researcher and educator that has led her and her family across the United States.

“I really built a career focused on how do you use different models of communication to influence the perception of ag and ag commodities. My experience focused on electronic media and how to use it to change perceptions,” she said.

Edgar pointed out that the public often doesn’t trust the science that comes out of higher education. Her aim is to craft messages that can help people understand what the land-grant university is about and the value of its research

Leslie Edgar, the new J.R. Simplot endowed dean of the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Idaho, took over the dean’s position in June, following the retirement of former dean Michael Parella.

and science to the general population as well as agriculture producers.

“My vision for CALS (College of Agriculture and Life Sciences) is, I really want to see our college focus on innovating Idaho, whether in teaching, research or Extension and how what we do as an academic unit that we can all be a part of innovating Idaho,” she said.

Edgar grew up on a farm

family in Kuna, Idaho, and received her bachelor’s degree in animal science and a master’s in agricultural systems, technology and education from Utah State University. As head of CALS she oversees more than 240 faculty on campuses across the state at 10 research and Extension centers and UI Extension offices in 42 counties and three tribal communities.

Before coming to Idaho,

secured millions of dollars in research grants and contracts, and earned numerous professional awards.

She is the first woman to serve as the J.R. Simplot endowed deanship — a position that was created earlier this year.

Edgar said the endowment is noteworthy because “they were really looking at the legacy (of J.R. Simplot) ... and wanted to ensure that the dean would have funding to make sure critical initiatives were met.”

Those initiatives could include situations such as disease outbreaks or other issues related to agriculture.

The Simplot company, which underwrites the position, “wants to make sure that the dean has some flexibility with funding to move forward with initiatives critical to the UI land grant institution and make sure we’re educating students and developing research to help agriculture and using the Extension system to make sure that information gets into the hands of producers and rural communities. We’re seeing a lot of volatility within the federal funding” for such purposes, she said.

Edgar is married and has five grown children. She and her husband enjoy gardening, canning, camping, fishing and own property in Council, Idaho, and Juliaetta.

Edgar was the associate dean of research and director of the Agricultural Research Center at Washington State University’s College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resource Sciences.

She also has taught and led research and experiment stations at New Mexico State University, the University of Arkansas and the University of Georgia. She has authored more than 70 journal articles,

“I always wanted to get back to the state of Idaho,” she said. And when the opportunity to apply for the CALS deanship opened, “I felt quite blessed as the first female dean for the UI and to be able to give back to the state in which I was raised and work with ag producers and make sure the research we’re producing, we’re taking it to rural communities and stakeholders so they can make good life decisions.”

Hedberg may be contacted at khedberg@lmtribune.com.

University of Idaho

The Nancy M. Cummings Research, Extension and Education Center in Salmon, Idaho, is seen in this photo. The center will be the spot of next month’s UI Rangeland Fall Forum.

Event at Salmon, Idaho, planned for Oct. 2-3

Registration is now open for those who want to attend the University of Idaho’s annual Rangeland Fall Forum, planned for Oct. 2-3 at Salmon, Idaho.

The forum will include panel sessions and hands-on learning. Those who want to register can go to tinyurl. com/ycvfrb4p

Panel discussions are planned for 1-5:30 p.m. Oct. 2, followed by a social from 5:308 p.m. The following day, a program titled “Novel Approaches to Restoration, Drone Show, Virtual Fencing

Show” is scheduled for 8-11:30 a.m.

The forum will take place at the Nancy M. Cummings Research, Extension and Education Center in Salmon.

The focus of this year’s event is on the new ideas and new technologies available to rangeland stewards, according to a UI news release.

“Some tools for managing rangelands are thousands of years old, like rock or wood fences, but as we enter an age of AI-assisted technologies and drones, rangeland stewards are going to have access to a wide variety of new tools,” said Eric Winford, associate director of the Rangeland Center.

Panelists scheduled to appear include Tip

Hudson, Washington State University Extension specialist and host of “The Art of Range” podcast; Tori O’Neil, rancher; Paul Wolf and Colby McAdams, U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service; and others.

The forum is open to anyone interested in rangelands, including operators, managers, businesses, nonprofits, governments, community members, journalists and students.

The Rangeland Center was established in 2011 by the Idaho State Legislature to address the challenges facing Idaho rangelands and the communities that rely on them, according to the UI news release.

Got something to sell, rent, or announce? Place your classified ad in the paper and online with one easy step. Whether it’s local readers flipping pages or browsing clicks, your message goes further. CLASS ADS are published

University

By Ralph Bartholdt University of Idaho

On Driscoll Ridge south of Troy, Jaycee Johnson learned about farming while sitting in the buddy seat of her father’s combine.

As they bumped along a rolling Palouse farm field kicking up dust, Johnson learned about erosion, soil moisture, yield and plant nutrients.

“I’d be sitting next to him in the cab of the combine, and you can just see as you’re going over a hillside where the yield is lower, and when you get into the draw you have a much higher yield,” Johnson recalls. “My dad was always very talkative and would tell me why this was happening, educating me about it.”

Hillside plants struggled because runoff eroded the soil, carrying nutrients to the valleys where crops thrived.

“My grandpa talked about the erosion; my dad talks about it — he’s been farming here for 40 years,” she said. “We definitely chatted about that quite a bit.”

Johnson, a UI doctoral student in biological engineering, is applying her farm experience to help boost yields on the Palouse.

Under professor Dev Shrestha,

Johnson is helping study how adding biochar to fields can reduce runoff and boost soil moisture on Palouse hillsides prone to erosion by wind, rain and snowmelt.

Basics of biochar

Biochar, a biproduct of farming and logging, is made by superheating leftover wheat stalks, chaff and wood slash until they disintegrate but haven’t yet turned to ash, Shrestha said. Biochar has been used in gardening to increase soil moisture, but it’s expensive.

Because the ingredients to make biochar are readily available in the Northwest, Shrestha sees potential for a regional, low-cost biochar industry.

“Right now, it’s very expensive to apply at farm scale,” he said. “But in the surrounding area and regionally, there are millions of tons of wood waste with very low to no market value. That wood waste can be turned into biochar to make a low-cost soil enhancement. Eventually, I’m hoping we can establish an industry here where the lumber mills can turn their wood waste into biochar.”

Lab studies show biochar improves soil moisture by increasing porosity and providing surfaces that retain water. Biochar’s large surface area and porous structure help soil retain more water per volume.

If farmers had an affordable product that could be applied to the least productive, highly eroded portions of their fields, they could boost

yields, reduce fertilizer costs and farm more sustainably, Shrestha said.

His team of students and faculty members from the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences installed nearly 300 underground soil sensors to various slopes in an agricultural field south of Moscow to monitor moisture. After a season of data collection, biochar will be applied to the same fields to measure its impact on soil moisture.

“We know biochar helps retain soil moisture, but we don’t yet know how much or its economic value to farmers,” Shrestha said.

“Once we have the data, we’ll develop software for farmers that gives them feedback on where and how much biochar to apply to get the most bang for their buck.”

Johnson said her father, like many Palouse farmers, is open to better farming methods and is always exploring new practices. If biochar proves effective and affordable, it will likely catch on with other local farmers, she said.

Many farmers are looking for ways to conserve the amount of nutrients that they often apply at a constant rate across their fields, Johnson said.

But overapplying nutrients to offset runoff caused by rain or snowmelt is costly. Much of it leaches away before reaching the plants where it is needed most.

Being able to keep fertilizer where it’s placed allows

farmers to decrease input costs.

Promoting a more efficient system

“This project aims to help farmers lower their input costs and increase yields, and that’s really what you want in an efficient system,”

Johnson said. “One of the challenges of farming is producing enough for a growing population with the same amount of land we’ve always had — biochar could help maximize the yield.”

The research also considers environmental factors.

“We want to produce a large yield for years to come, so we want to retain topsoil and prevent leaching of chemicals and fertilizer into waterways, which can harm the environment,” said Johnson.

Later, she learned how to operate all the equipment on the farm, from small tractors to combines.

“I remember conking it out on the hillsides and having to let out the clutch to get it to go again, or roll backward down the hill,” she said.

Johnson earned her undergraduate degree in 2024 in biological engineering at UI after her dad encouraged her to pursue a degree that was practical.

“I knew I wanted to do something agricultural related,” she said. “This research has the potential to really help farmers in the region.”

Jaycee Johnson grew up farming with her family near Troy where she learned early about the problems of erosion on the Palouse.

Melissa

Hartley/University

of Idaho

“We know biochar helps retain soil moisture, but we don’t yet know how much or its economic value to farmers. Once we have the data, we’ll develop software for farmers that gives them feedback on where and how much biochar to apply to get the most bang for their buck.”

DEV SHRESTHA, UNIVERSITY OF IDAHO PROFESSOR

Area farmers say all winter crops and most spring crops have been harvested, and yields were better than expected

Combines move across wheat fields south of Lewiston in July. Despite drought conditions, most farmers in the region had decent yields during this summer’s harvest.

August Frank/For Farm & Ranch

August Frank/For Farm & Ranch

Machines work the fields south of Moscow during harvest in August. Despite drought conditions, most farmers in the region had decent yields during this summer’s harvest.

By Kathy Hedberg For Farm & Ranch

Although many farmers feared massive crop failures this year because of the prolonged drought, winter wheat harvest, for the most part, has come in much better than expected.

“I was pessimistic about how the crops were coming out,” said Randy Olstad, grain division manager for the Pacific Northwest Farmers Cooperative in Colfax.

“We definitely had no bumper crop but I think the crops surprised most people. They were a little bit better than expected. Some pockets were 10% to 15% below average and spring crops were a letdown. But we were thinking we were going to have big quality issues but overall the quality aspect was really good.”

As of the first week of September

all winter crops and most spring crops in the region had been fully harvested. Pulses, namely garbanzo beans, are usually the last crop to be harvested and most farmers had wrapped that up by the second week of the month.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor for the first part of September, most of north central Idaho and southeastern Washington remained in the red zone, indicating severe drought. Olstad pointed out that farther north the temperatures eased up somewhat and “the Bonners Ferry crop had really good rains. When they were trying to harvest they had too much rain and some quality issues, mainly because it was too wet.”

Doug Finkelnburg, University of Idaho Extension agent for Nez Perce County, underscored Olstad’s

assessment of the harvest year.

“Overall it’s kind of two different stories,” Finkelnburg said. “Winter wheat came out better than everyone feared with average to below-average (yields) and quality fairly decent. It wasn’t great but, again, it turned out better than everyone was fearing.

“We’ve been in a drought situation for months but the crop finished early.”

Finkelnburg said he got word from a grower in the Lewiston area who began cutting his winter wheat on June 29 — 10 days to two weeks sooner than usual.

“The spring cereals were severely affected by the dry weather and (harvest) was significantly below average,” he added.

One bright spot was that, because of the drier weather, stripe rust and other fungal diseases that

can affect wheat and other cereal grains were not much of a problem this year.

The outcome was the same for peas, lentils and chickpeas as for wheat, Finkelnburg said. Variety trial data on pulses from the Camas Prairie and Palouse showed that the crops did well, although spring pulses did not flourish.

“The story is, the reason we grow so much winter wheat here is, it’s less risky,” he said. “It uses moisture stored in the ground over the winter and finishes with moisture in the spring. When water is our limiting factor, winter crops are less risky in this area.”

Finkelnburg said it is hoped the area will receive ample moisture this fall to allow farmers to seed their winter crops before snowfall.

Hedberg may be contacted at khedberg@ lmtribune.com.

As cities swell and rural populations shrink, a Washington State University Extension-led coalition is tackling the challenge of how to feed urban communities using locally sourced foods.

Spearheaded by the National Urban Research and Extension Center (NUREC), the Building-Integrated Agriculture (BIA) initiative is planting the seeds for a

novel food system designed for cityscapes — think fruit and vegetables grown on skyscraper rooftops, against stadium walls, or inside repurposed warehouses.

“Our initiative is about reimagining how agriculture and cities coexist,” said Brad Gaolach, the founding director of NUREC who is based at WSU Everett’s Metropolitan Center for Applied Research and Extension. “As a national project incubator, we’re about spurring this type of innovation.”

The BIA initiative launched with the 2024 Grow(in)’ On! Summit, which convened nearly 70 experts from 13 states and three countries to explore how cities can integrate food systems

design and policy. Outcomes so far include new research collaborations and the formation of national working groups focused on workforce development, demonstration projects and urban ag education.

While the traditional land-grant Extension system historically focused on rural regions, more than 80% of Americans now live in metropolitan areas, according to the 2020 U.S. census. NUREC, which transitioned from a regional hub in Washington state to a national center in 2023, is working to align national Extension services with the modern needs of urban residents, many of whom face food insecurity or limited green space.

“I recently led a national discussion group of Extension faculty and staff on how to handle a local resident’s request for assistance with establishing vanilla bean production in abandoned warehouses,” said Maggie Anderson, WSU NUREC program manager. “We’re also working on connecting the farmer at Fenway Park stadium in Boston with entrepreneurs and farmers in other cities nationwide to implement garden-top stadium designs similar to the one there.”

A cornerstone of the initiative is a toolkit of learning modules, resources, blog posts, and reflections, all aimed at solving the design challenges of urban food production. Developed by WSU in collaboration with Oregon

State University and the University of Oregon, the toolkit is funded via the USDA 2025 Farm Bill.

“This toolkit helps answer questions like, ‘Can you recycle graywater in a greenhouse on top of a skyscraper? Will a nearby building block sunlight? What’s the load-bearing capacity for a rooftop garden?’ ” Gaolach said. “We’re translating our agricultural insights into architectural practice.”

NUREC’s summits and workshops are also sparking unexpected collaborations among city officials, architects and entrepreneurs eager to embed food production into urban planning, public health, and climate resilience strategies. In partnership with the National League of Cities, the BIA initiative is expanding its reach to a nationwide network of urban leaders.

“We’ve got people saying, ‘Let’s start a podcast. Let’s find funding. Let’s build momentum,’ ” Gaolach said. “That’s the kind of energy this initiative is attracting.”

NUREC’s work offers a glimpse of what future Extension services and food systems may look like.

“We have to start thinking of food as critical infrastructure,” Anderson said. “We’re helping improve food security and urban livability in Washington and across the nation.”

“This toolkit helps answer questions like, ‘Can you recycle graywater in a greenhouse on top of a skyscraper? Will a nearby building block sunlight? What’s the load-bearing capacity for a rooftop garden?’ We’re translating our agricultural insights into architectural practice.”

— BRAD GAOLACH FOUNDING DIRECTOR OF NUREC WHO IS BASED AT WSU EVERETT’S METROPOLITAN CENTER FOR APPLIED RESEARCH AND EXTENSION.

Amplify your crop’s root systems from the start. Increase water and nutrient use e ciency with &

By Mara Mellits The Seattle Times

Don McMoran is a fourth-generation farmer. And his family’s farm in Mount Vernon, Wash., might end with him.

McMoran grew up on his family’s farm. He remembers the “good old days” when he’d work hard, but also made enough money to replace equipment or buy new land.

McMoran has two 16-year-old daughters. One is “mildly interested” in the family farm, he said, while the other is “a hard no.”

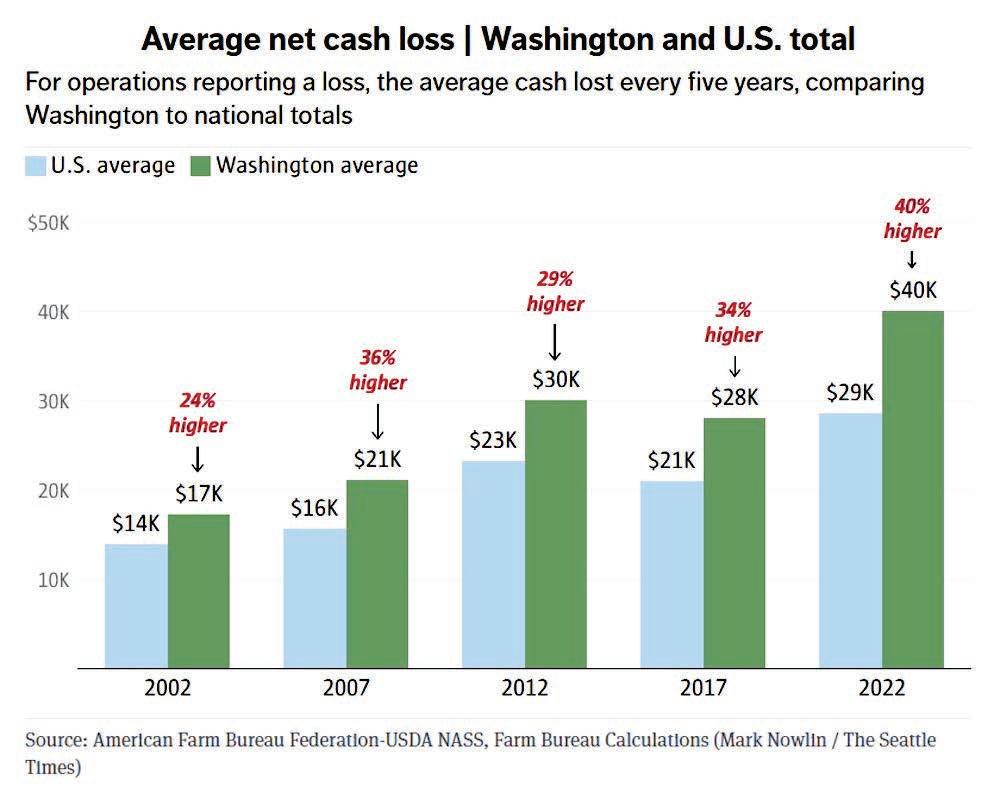

His story is one familiar to many Washington farm families. The stressors placed on farmers, including inflation, weather changes and tariffs, can all take a toll on their mental health, leading them to shut down their farms and leaving the next generation less interested in taking over. Over 3,700 farms shut down in Washington from 2017 to 2022, according to the Census of Agriculture.

“It’s fun when you’re making money, but the flip side of that is when you work your tail off and you have to go to your banker and get a loan, that’s not fun at all,” McMoran said.

The potential of a generational farm leaving the valley, that’s a really hard pill to swallow,” he said.

A 2025 report conducted by the Washington State Department of Agriculture found the state’s farmer suicide rate far exceeds the national average. Agricultural suicides are nearly 25% higher than the overall state rate, according to the report. Strenuous lifestyle, lower access to mental health providers and the social

stigma that comes with seeing a psychologist all contribute to higher suicide rates in these communities, the report said.

Many farmers also lack benefits such as health insurance, paid leave and retirement plans.

State Rep. Tom Dent, a Republican from Moses Lake, secured funding for the report and was on the committee that oversaw it. He said he understands the stressors firsthand as a farm owner. He’s even had his own friends take their lives, he said.

Dent said the report is concerning but also eye-opening. Farmers face several economic stressors as profits fail to cover the increasing cost of labor and rising prices for fuel, fertilizer, seed and chemicals, according to the report. In 2023, labor expenses were 462% higher in Washington than the national average, according to data from the American Farm Bureau Federation. Another labor concern: Farms reliant on immigrant farmworkers have also faced uncertainty as President Donald Trump’s administration began its immigration crackdown, though Trump has since curbed enforcement at farms. He’s also indicated he may

break from his pledge to deport all undocumented immigrants to allow migrant farmworkers to remain in the country.

Dent said that when working on a farm, there’s always something to do. With costs going up and farm products being worth less, it puts a bigger load on farmers. They stop going out for dinner and attending church, and all that’s left is the stress of the farm.

“When farmers are making money, there’s no better job in the world,” McMoran said. “But to get up every morning, work your tail off to lose money. That’s a really difficult situation to be in.”

‘It’s a 24-hour job’

When McMoran saw how stressed other farmers in his community were, he decided to do something.

About three years ago, he teamed up with Conny Kirchhoff, the associate director of the Washington State University psychology clinic, to launch a free therapy voucher program. McMoran had already been serving as director of Washington State University extension in Skagit County and principal investigator of the Western Region Agricultural Stress Assistance Partnership.

The voucher program offers six free sessions with Kirchhoff, a licensed psychologist, to all farmers and farmworkers living in Washington. While she does offer in-person sessions, most take advantage of the virtual option. That way it’s completely anonymous: No one can see their pickup and wonder what a farmer may be doing at a doctor’s office, McMoran said, noting the stigma of reaching out for help is very apparent.

“From my upbringing, I was taught from a very young age to bite your lip, don’t cry, don’t complain, jump in, get the job done,” McMoran said.

Kirchhoff has observed financial worries are the No. 1 stressor for farmers.

“It’s a 24-hour job,” Kirchhoff said. “Very often, if it’s a farm that has been in a family for several generations, it feels like it’s a personal failure if they have trouble on the farm.”

In addition to the therapy voucher program, McMoran also created Pizza for Producers. The initiative invites agricultural workers to learn how to make pizza and serves as a mental health workshop for farmers and farmworkers, who often work in solitude. The latest Pizza

for Producers event was held this month.

In the 2025 report, many farmers listed the burdens that come with regulations as another stressor. Several said navigating government agricultural and grant programs while also ensuring compliance with new policies can be overwhelming. Farmers said understanding the bureaucratic language takes time and resources.

Dent said it’s important for politicians to assess the regulatory load placed on farmers.

“Are we creating a further financial burden by some of the things that we’ve done through the Legislature, and if so, can we reduce that burden?” Dent said.

Some farmers even said they use specialists to interpret some of the legal jargon.

Farmers found loan repayment requirements to be some of the most confusing, according to the report.

McMoran said the regulations placed on farmers in Washington are much higher than in other states.

“When it all comes down to it, farming isn’t as much fun as it used to be,” McMoran said.

Continued on Page 12

Continued from Page 11

Generational pressure

For some, the biggest stress can come from inside your own home. Kids see the stress placed on their parents and don’t want to continue with farming. Farmers feel the stress of not letting down the generations that came before them.

McMoran said he doesn’t blame his daughters for not wanting to take over the farm. He knows how hard the work is and how low the returns are.

In his role with WSU extension,

McMoran talks to many young people who share his daughters’ view and don’t want to go into farming. The extension’s agriculture and food systems program works with young people to get them excited about farming.

There are many farmers who’d love to pass on their farms to the next generation, McMoran said, but it’s hard when there’s not a lot of profit.

His parents told him his predecessors went through difficulties to find the perfect place to farm, just so it’d be his.

“You better not screw it up,” McMoran recalled. “That’s a lot of pressure.”

Laura Siegel, the health communications officer for AgriSafe Network, a national nonprofit that educates health care providers and people working in agriculture, said that even when kids do want to take over, the hand off can be difficult.

For longtime farmers, handing over control feels like they’re losing a part of their identity. That can lead to another tension point: when the younger generation has new ideas that older generations may not agree with.

Working with family can also get

tough, though Siegel notes carving out time to spend together when no one discusses work or the farm can help.

Dent said that when he speaks with his constituents, a common sentiment is, “great-grandpa started this ranch, and I’m going to lose it.”

For farms that have been in a family for several generations, it can feel like a personal failure if someone has trouble on the farm, Kirchhoff said.

“We’re always looking for solutions,” McMoran said. “I’d love to work myself out of farm stress suicide prevention work. This year, it’s needed more than ever in history.”