PRACTICE

LEADERSHIP

LEADERSHIP

VISION

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE PREMIER LEAGUE

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

TO SURVIVE LONG ENOUGH TO SUCCEED, YOU WILL NEED TO BE IN PEAK CONDITION, PHYSICALLY AND MENTALLY PROF VIN WALSH PAGE 89

The League Managers Association, National Football Centre, St. George’s Park, Newborough Road, Needwood, Burton upon Trent, DE13 9PD www.leaguemanagers.com

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and not necessarily those of the League Managers Association, its members, officers or employees. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

Editor Alice Hoey alicehoey1@gmail.com

Editorial Contributors from the LMA Wayne Allison, Mark Farthing, Sue McKellar, Jason Ratcliffe

Publisher Jim Souter jim.souter@leaguemanagers.com

Art Editor Sarah Ryan sarah.ryan@leaguemanagers.com

Artwork

Luna Studio

Illustrations © iStock

LMA Chief Executive

elcome to the LMA Mental Health and Resilience Guide, the latest in our series of Personal Development Guides. These world-class resources are designed to be an essential part of your toolkit throughout your management career.

The LMA is committed to offering ongoing support, advice and expertise to its members and affording insight to managers and coaches across the professional game. Through its Institute of Leadership and High Performance, the LMA delivers CPD-accredited educational programmes and resources, created around a 360-degree model, covering You, Your Team, The Game and The Industry.

This model starts with You. Your personal health and wellbeing is fundamental to success in football coaching and beyond, so we are committed to giving you and your family members access to the best wellbeing support and resources available at every stage of your career.

These support services are provided under the LMA Wellness programme. Through the Wellness programme, our members and their families have access to world-leading healthcare professionals and specialist clinicians across all areas of wellbeing. Members are offered regular bespoke, personalised health assessments, personal lifestyle guidance, and 1-to-1 mental and emotional wellbeing support, 24/7.

Our mental health services are guided and supported by the LMA’s team of in-house consultant psychiatrists and psychologists, who have many years of experience working in football and other elite sport environments, including Olympic and Paralympic sports, rugby, cricket and tennis.

While football management and coaching can be exciting and extremely rewarding, it is a relentlessly high-pressure environment, characterised by volatility and instability, and many emerging challenges. It is therefore of utmost importance that you are aware of the potential issues and pitfalls that you may face during your career, and build coping strategies to get you through the tough times.

Everyone has mental health as well as physical health and, as with physical health, there may be times when you feel less mentally fit than usual. The purpose of this guide is to give you supporting information in the area of mental health and resilience, and ensure you know where to access support, if and when you need it.

It includes, for example, sections on Loneliness and Isolation, Depression, Anxiety, Motivation, Sleep and Nutrition, and examines how you can take control and take positive steps towards maintaining a healthy balance. Most importantly, it provides signposting to the extensive support services provided by the LMA.

We are hugely grateful to all members of the LMA Medical Advisory Panel and our wider specialist team for the support and guidance they offer to our members, and to the LMA team for providing the very best of care.

With respect to this guide, in particular, we would like to thank the LMA members, overleaf, for their honest insight, and our contributors: Dr Fairuz Awenat, Dr Steve Bull, Dr Andy Cale, Jeannette Jackson, Steve Johnson, Dr Allan Johnston, Nick Littlehales, Richard Nugent, Jason Ratcliffe, Dr Tim Rogers, Jeremy Snape, Prof Vincent Walsh, Tom Young, and our Editor, Alice Hoey.

We are also extremely thankful to the Premier League for their invaluable support in delivering world-class programmes and resources to our members.

This guide, like much of the learning provided through the LMA Institute of Leadership and High Performance, would be nothing without the unique insight of the LMA’s members.

We would like to thank each of the managers here sincerely for their time and honesty in sharing their experiences.

FOCUS ON THE FUTURE THAT’S WITHIN YOUR CONTROL RATHER THAN THE PAST YOU CANNOT CHANGE

ALICE HOEY PAGE 26

A little preparation can make the transition to full-time management less of a psychological shock to the system.

Words: Richard Nugent

Whether your first step into management has been carefully planned or thrust upon you out of the blue, there is something unique about the mix of excitement and anxiety that comes with the first days of the job. Even experience in an assistant or supporting role won’t fully prepare you for the mental challenges of being in charge, with all the pressure and responsibilities that it entails. There are, however, things you can do to get ready to lead, starting with these five areas of focus:

Perhaps the single most important piece of work you can do ahead of starting your first job is to get clear on what your leadership values and principles are. Numerous pieces of leadership research tell us that we are more likely to follow, engage with and be motivated by someone who is clear on what they stand for and who demonstrates those beliefs consistently.

What can your players expect from you? How will you show up for your staff every day? What is your core belief about people and leadership, and how are you going to live that every day?

If you’re moving out of the dressing room and into the manager’s office, one of the biggest changes early on is likely to be the nature of your relationships. You will never be able to have quite the same connection with a group of players again. With this in mind, it is vital to develop a new, different set of connections in order to avoid the sense of isolation that many managers feel.

If you have the opportunity to recruit your own staff, they can form part of the group that gives you that important social connection, but you also need to think beyond this. Who will you spend time with away from work? Who are your trusted confidants? Who will give you energy when you need it and who can help you to relax? When things are at their toughest, who are the best people to spend time with?

You will need your connections at the most difficult of times, so don’t leave relationships and support to chance.

Too many managers think that relentlessness is the foundation of success, but you can’t expect yourself to perform at your best without structured rest and recovery.

Recovery should be viewed as an important performance factor, and as such it must be scheduled, protected and regular. As a new manager, there is so much to learn, and so many new situations will challenge you mentally and drain your energy. The idea that it is healthy and productive to work at maximum capacity every day for the season and recuperate afterwards is outdated. Schedule social time, exercise, family and relaxation and stick to the schedule diligently.

There might be a temptation in your first job to stay in firm control by doing everything yourself. However, a consistent trait of genuinely confident leaders is their ability to relinquish power. Doing so means forward planning.

If you’re clear on your values and principles, it should be easier to decide what you do and what others will be responsible and accountable for. It also helps if you are able to recruit your own staff, with an understanding of what you need them to deliver and how.

Whether or not you hire your own staff, it’s important to set people clear goals and expectations, then let them get on with doing their jobs. If they underperform or under-deliver, manage them, but also remember to give them feedback on good work so they can learn, progress and be more willing to do it again. Delegation can itself take time, so ideally all of this should be planned ahead of your first day in the job.

When preparing for large-scale change, there are four critical areas for self-leadership and wellbeing. These should be developed ahead of your first role to give a solid emotional base for the challenges and excitement ahead:

Self-efficacy – the sense that you can make a difference, learn and overcome challenges. This can be developed by reflecting on previous successes and by gathering feedback from others.

Self-esteem – by focusing on times when you have had a positive impact on others and contributed to challenging situations, you will increase the value you place in yourself.

Resilience – the ability to recover from challenges is an innate one. Spending time reviewing situations when you have overcome difficulties further develops resilience.

Self-confidence – the core emotional state of trust in yourself is crucial for optimal performance and decision making. Reflect on situations when you felt naturally confident and imagine yourself in other more challenging situations feeling just as confident. Remember, confidence is an internally generated state rather than something that develops as a result of external achievements.

Many managers run headlong into their first jobs without preparing themselves, mentally and emotionally, to face the myriad of decisions and the complex challenges that the job entails. With a solid foundation, based around the four critical areas, you’ll have the best chance of making the most of that first, crucial opportunity.

Give yourself time to consider the role from every angle. What will leadership mean to you? How will you live your values and principles? What are your motivations and hopes, and are your expectations realistic? Think, too, about who you will surround yourself with and what roles they might play, at work and away from it, and who you might turn to for support and advice. Leave nothing to chance, especially not your wellbeing.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

As the manager, your every word and action will be scrutinised by the media and fans, and your public profile will grow and change in nature. Preparation and resilience are key if you’re to safeguard your mental wellbeing and perform at your best.

Words: Walter Smith OBE

I’ d served as assistant manager to Jim McLean at Dundee United and Graeme Souness at Rangers before I became full-time manager for the first time, at Rangers. I therefore had a good understanding of what the job entailed. However, even if you have an appreciation of what’s required of the manager in terms of media handling – how tough it can be to give a press conference following a big defeat, for example – until you’re in those shoes you can’t know what it feels like. It’s one test where you can’t know how well prepared you are until you’re sitting there facing the cameras.

There are also big changes when it comes to the level of exposure and scrutiny you face when you become the manager. As an assistant manager or in another support role in the club lots of people know you, but generally they’re people within the club or associated with it. When you become the manager

you’re thrown into the spotlight and are suddenly known to a far greater audience. Your public profile grows and if you were previously a high-profile player then that won’t feel too much of a change.

If, like me, you weren’t then it can take some adapting to. Even after 10 years as an assistant manager, it was a relatively new thing to have members of the public know who I was. While it may never become something you enjoy as a manager, you do get used to it over time. It’s a reminder that you have a public profile that you need to be careful with.

I’ve found it to be, on the whole, a pleasant thing to have people recognise and approach me when I’m out and about. However, it can feel more of a challenge when you’re going through a difficult time in the job, when the team has had a run of bad results or when there’s a real test of your abilities as a manager.

The level of scrutiny from both the public and the media is now very high and constant. When I first started in management, I had to deal largely with the written press, but television came to the fore and then, towards the end of my management career, so did social media. Managers now face criticism from the public and the media on all of these channels and it can be tough, mentally, to deal with this, as you’re often not able to respond, or to respond as you might want to.

For example, I think it’s important to not enter into online discussions or respond to criticisms online; it can open up a can of worms and make things more difficult for you in the long run. It’s best to remain professional at all times and try to think about what you can influence. Don’t waste time on things you can have no effect on.

There have been several times in my career when I faced very difficult situations but wasn’t able to open up to the media. Once was at Everton when players were sold behind my back, and the second was at Rangers when the club was going through financial difficulties. Something like that really tests your resilience. There are always reasons why things are the way they are and why we make the decisions we make, but as the manager you’re not always able to give people the full story.

Over time, you learn to handle situations like these in a way that puts on the best front and that conveys your messages as best you can. Experience teaches you the skills you need to be able to handle all aspects of the media, including criticism.

Ultimately, criticism comes with the job, and no matter how successful you are you will still come in for it to some degree. If you’re someone who is badly affected by it, you either need to develop your resilience skills or accept that the job’s not for you.

It’s important to be able to accept it when people find fault with what you’re doing, just as you accept their praise when they agree with it. Say to yourself that you’re not going to be influenced or affected by either. I always took the approach of taking that middle ground and it certainly helped me through. It meant I didn’t get too carried away when we were successful nor too down when we weren’t.

Ultimately, the high profile nature of the football manager’s job can mean that at times it feels like you’re living life in a goldfish bowl. However, it’s something you do get used to and get better at handling. It’s worth remembering, too, that your public profile sometimes puts you in a position where you can help a great many people; it’s important to remember and appreciate that.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

Staying calm in difficult or high-pressure situations enables you to perform at your best and reduces the risks to your mental wellbeing. Equipping yourself with good resilience skills is key.

Words: Alice Hoey

While all managers face difficult, often high-pressure, situations throughout their careers, not all cope with them in the same way. Those who are equipped with good resilience skills respond calmly and rationally, maintain perspective and feel in control. As a result, they are able to arrive at decisions and solutions with relative ease and move on from each situation quickly.

People with low resilience are more likely to perceive situations as challenging or threatening and so more readily exhibit symptoms of stress. This stops them from performing at their best just when they need to most, and over time can damage their mental wellbeing, increasing the risk of low mood, depression and anxiety.

Chronic or prolonged work-related stress can even lead to burnout, which is characterised by exhaustion, cynicism, a lack of job satisfaction and the

perception that you’re less capable at what you do. People suffering from burnout may start to distance themselves from the people around them, impeding their professional efficacy, and their physical and mental health may start to deteriorate.

The good news is that, while some of us might be naturally more resilient in the face of difficult or high-pressure situations than others, through practice and experience we can all improve our resilience skills.

It’s helpful to first understand what’s going on in the body when you feel stressed. The symptoms are essentially those of the primitive fight-or-flight response – the heart beats faster, the breathing quickens, the muscles tense and you may begin to panic, over-think things or catastrophise. When this happens you need some in-the-moment strategies to quickly turn the threat response down and regain some focus.

Exercises that involve focusing on the breathing (see below) can help to lower the levels of certain neurotransmitters in the brain associated with the stress response. This has the effect of bringing breathing and heart rate back to normal, enabling you to think more calmly and rationally.

Such exercises are also useful in bringing your thoughts back to the present. As stress often stems from thinking about negative outcomes, realistic or otherwise, being able to remain focused only on what’s happening right now is key.

1 Breathe by inflating and deflating the belly rather than the chest.

2 Breathe in deeply, then exhale until every bit of air has left the lungs.

3 Breathe in through the nose to the count of five, then out to the count of five.

Fundamental to learning to perform better under pressure is the realisation that it isn’t the situation itself that is stressful, but how you perceive it. That’s why two people will react differently in the same scenario. Indeed, stress is defined as the imbalance between how you perceive the threat or challenge and how you feel that you can cope with it. By trying to change your perceptions around these things and see things in a different light you can start to respond in a more constructive manner.

The first step is to think about what’s driving your response to the situation and identify if you’re falling into one of a number of common mind traps. These include ‘all or nothing’ thinking, where you focus on total success or total failure, ‘personalisation’, where you take all of the blame when something goes wrong, and ‘catastrophising’, where you allow your thoughts to leap forward to worst-case scenarios.

Once you know that you’re falling into a mind trap, it’s possible to challenge your perception of the situation and start to think differently. Ask yourself questions such as these:

• What is the worst that might happen as a result of this situation?

• Is my response in proportion to that possible outcome?

• What might be influencing my perception of the situation and is that helpful or even logical?

• Can I look at things another way?

• How would I advise a friend or colleague to react in this situation?

Given the turbulent nature of management, the ability to remain stoic in the face of defeat and setbacks and to bounce back quickly from disappointment is essential. An important part of resilience is the ability to remain rational in difficult or negative situations and to look forward in a positive frame of mind. Regrets can be difficult to shake off, but once you’ve taken useful lessons from a past experience it’s essential to accept what has happened and move on. Stress, as we’ll see in the article on Dealing with Change (pg 36), often results from feeling a loss of control, so focus on the future that’s within your control rather than the past you cannot change.

When you do find that you’re burdened with worry or regret it can help to put your thoughts in writing. List all the things that cause you concern, anxiety or stress and then note for each one whether you have any influence or control over it. This process should help to highlight what it is worth focusing on, i.e. the things you can control and influence, and what it is pointless to worry about.

I’ve learned that you can only get hurt by things that you allow to hurt you and you can’t control what people think about you. Actually most people aren’t thinking much about you at all, so there’s no point in worrying about it. You can only do your best.

JOHN COLEMAN

Developing resilience is essentially about forcing yourself to think differently about the situations you face in life, including those you perceive to be high pressure. For example, is the pressure you are feeling generated by you and is it based on expectations that are actually beyond your sole control to deliver?

Given that everyone has different criteria for success, you can never meet everyone’s standards, so the most important measure has to be your own. However, it’s important that you don’t put yourself under unreasonable pressure by judging yourself by unrealistic standards.

Pressure is often positioned as harmful, but you need some pressure to perform at your best. What’s key is finding effective tools for dealing with difficult situations so that you can control your stress response and continue to perform at your best when you need to most.

Recognise that you are not at the mercy of your thoughts and emotions, but can learn to turn down the brain’s filters and, calmly and rationally, begin to see things for what they really are.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

Improved mindset for dealing with periods of uncertainty

Improved physical and psychological wellbeing

Better task focus

Better problem solving and ability to think clearly under pressure

Improved performance

Increased ability to sustain performance during periods of high demand

Reduced likelihood of suffering from anxiety and depression

Better sleep

Lower risk of stress-related health problems, such as heart disease

I’ve learned to cope with tough times and disappointments by saying to myself what I say to my children, which is that so long as you know you’ve done your best you can sleep at night. If I know I’ve done my best, whatever anyone else thinks, that’s good enough for me.

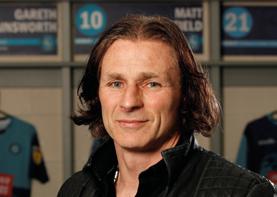

GARETH AINSWORTH

I had over 16 years’ experience as an assistant and first-team coach before I got my first management job, so I was probably better prepared than many managers. However, it’s still so different when you become the manager and you have to make decisions you didn’t have to make before.

I was lucky early on because we were winning games, but there were also very difficult periods. During those times, it becomes so much harder to cope; you have to work so much harder at dealing with the pressure.

Even though you may wake up on Monday morning still feeling down about the weekend’s result, you know you can’t let those around you see it. You mask it to give the impression that you’ve got it out of your system and are looking ahead to the next challenge, to training and planning for the next game.

At any stage in your career there will be an element of masking your real thoughts and emotions, but over the course of your career you learn to cope with your emotions better. I’m at a stage of my career now where I’m more able to roll with the disappointments, accept them and move on. That partly comes from experience. The more situations you find yourself in the more you feel you can handle the next one and, over time, you devise mechanisms to help you do that.

While leaders at the top are usually surrounded by people, they often feel isolated and alone. Turning to others in a similar situation for support is one of a number of coping strategies.

Words: Tom Young

At some point in your career, it’s likely you’ll experience feelings of loneliness or isolation. As human beings, we are instinctively social animals who crave connection and belonging. Yet leadership dictates that ‘the boss’ is always one step removed from the in group. As the manager, you are treated differently. This may be particularly noticeable if you’re just starting out, especially if you’re transitioning from player to coach. Too friendly and you get too close, too cold and relationships become difficult to build. Either way, you are no longer one of them.

A paradox of leadership is that you may feel lonely and isolated, yet you are surrounded by people, energy and noise. Even when you are actually alone, your smartphone will be pinging constantly with fresh information and communication.

Isolation is defined by your perceptions. Despite the chaotic and dynamic nature of your role, it is you as the leader who shoulders the ultimate responsibility for the success of the team, constantly balancing the immediate need for short-term results with the broader aim of long-term development. One leader, in another sport, described the feeling as, “like walking around with your P45 in your pocket each and every day”.

Football managers are by no means unusual in this. Chief executives in boardrooms around the world have been found to experience the same thoughts and emotions. In some ways, it indicates an element of effective leadership – that you are maintaining a certain level of distance between you and the people you are leading.

These feelings are entirely normal, understandable and human, and are particularly relevant to leadership. We have been writing about loneliness in leadership for hundreds of years. In Henry IV, Part II, William Shakespeare writes, “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.”

However, while loneliness is a common and perfectly valid human emotion, it can be damaging, chipping away at your resilience and increasing the likelihood of mental health issues, such as depression, stress and anxiety. So, what proactive steps can you take to counter this side-effect of leadership?

There’s always help and support out there. You can ask the opinions of your backroom staff at the club, but sometimes it’s helpful to turn to people on the outside who may have a view while not being so close to the problem.

WALTER SMITH OBE

During times of loneliness or isolation, you may feel alone with your thoughts and try to push them away. This can be energy sapping and rarely works. It is far more effective and rational to acknowledge your thoughts, write them down, and reflect on them.

Much of the problem of isolation, or feelings of isolation, stems from the weight of responsibility that the leader carries and their understandable reluctance to unburden themselves on others, particularly their staff. However, given that most managers will have wrestled with such emotions during their careers, it can help to share your experiences and thoughts with trusted colleagues and friends in the game. Make use of your existing connections, make new ones at networking and learning events, and build trusting relationships.

This process does not need to be exclusive to football, but can extend to learning from other leaders and other sports. Mentors can also prove invaluable in acting as a sounding board for your thoughts and emotions and may be able to draw on their personal experiences to help you find a more positive way forward. Leaders tend to have few people they can turn to for advice and honest conversations, so think about who might fill this role for you.

In order to build a high-performance culture there needs to be trust, and for trust to exist there must be a foundation of vulnerability, a willingness to talk about how you’re feeling. Far from being a sign of weakness, sharing your emotions is essential; if you as the leader can’t do this, how can you expect the same of your people?

While it’s easy to become engrossed in your role and to find yourself defined by your professional life, it’s essential to not neglect the other areas of your identity. Talk to those people who are closest to you and seek out moments of value elsewhere. Spending time with family and friends, or pursuing a hobby or physical activity can provide a much-needed sense of perspective.

You may feel isolated in your role at times, but remember there are a host of other coaches and managers in the same position. As awareness of mental health increases, we encourage people to ask for help or to check in on others. Make sure you look after each other. Read more about Identity on pg 70.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

Becoming proficient at identifying your irrational or limiting beliefs will help you to ‘flip’ them towards a more rational and solutions-based way of thinking. This process of reflection is a habit and a skill that needs to be worked on over time.

Start by giving yourself a 10-minute time slot at the beginning and end of each day, then increase this over time, if possible.

Turn your phone off and anything else that might distract you.

Think about your most common negative reactions, such as bursts of anger, stress or anxiety and where they might stem from.

Look back on recent situations, question how productive your response was and how you might have reacted differently.

Management can be a very lonely place. Everyone is on your side when you’re winning, but when things aren’t going your way you learn quite quickly who your friends really are and who has your back.

Over the past year, however, I’ve learned that you’re only as isolated as you allow yourself to be. You have to let people in as much as you can. Don’t shut down; use the people you trust, the ones you know are there for you during bad times as well as good and, in particular, other managers in the game.

It has been overwhelming to me how many people in and around the women’s game have reached out to me with support over the past year. I’ve learned that if you’re willing to open yourself up and let people in there are many people out there willing to help, many of whom will have been through something similar in their careers.

Research suggests that uncertainty and lack of control are the principle causes of stress. Unfortunately, challenging periods, normally accompanied by some element of change, expose us to both.

Words: Dr Fairuz Awenat

The human mind tends not to like uncertainty, particularly where threat is possible. Scientific studies have found that most people would rather know that they’re going to have a negative experience (such as an electric shock) than be unable to predict it. In other words, people feel less stressed when they know what’s coming, even if it’s painful.

The idea is that by knowing it’s coming you can at least prepare to deal with it. From an evolutionary perspective this makes sense, because being familiar with your environment and able to predict things has strong survival benefits. As a result, we’ve evolved to judge the feeling of uncertainty itself as a threat. Football management is a uniquely pressured environment, with constant uncertainty and many aspects that are beyond your immediate control. Right from the start of your career, therefore, it’s important to have at your disposal tools that enable you to manage these constant ‘threats’.

The skills proven to be helpful are known as ‘psychological flexibility’ skills and, like any skills worth mastering, they take the commitment of ongoing practice if they’re to pay dividends.

As is the case with many things, prevention is preferable to cure. If you can build the psychological flexibility ‘muscles’ ready for use, they’ll be able to flex when the heavy lifting of life is needed. Try to ensure that however pressured your life is, you make time for basic self-care. This might include a regular commitment to exercise, daily practice of mindfulness meditation, setting boundaries between work and family life, and giving yourself opportunities to eat and sleep well. While these may sound basic or obvious, the cumulative effect will be that you develop enough resilience to roll with the curve balls that life throws at you.

However passionate about the job you are, it’s also essential to remember that your job is ‘what you do’, not ‘who you are’, and to recognise that you fulfil various important roles other than your job. When unsettling changes are taking place in your professional life, it is helpful to broaden your focus and find stability in other meaningful areas of your life, whether that be family, hobbies or a learning activity in which you might be involved.

It is the things that matter most to us in life that cause us the most pain, so it’s inevitable that when things don’t go the way we want or threaten to go wrong we experience psychological pain. This is what’s known as ‘the reality gap’ – the gap between the reality you want and the one you currently have. In such situations we often expect ourselves to not feel these unwanted emotions, but this is unrealistic; humans are supposed to feel pain when things they care about go wrong. It is unavoidable, what is key is how you respond to it.

Faced with unwelcome challenges, the human mind often kicks into dwelling on problems that are out of its control, predicting future ones, and constantly time travelling between the past and future. While we’re doing this we’re missing out on actually living life right now. Mindfulness, when practised regularly, is a useful tool for noticing unhelpful thoughts without getting caught up in them, enabling you to refocus your attention on taking effective action to deal with the problem in hand, rather than wasting time worrying about it.

Given that things beyond our control cause us stress, it helps when we feel that we’ve regained some control where we can. There are only three things that are completely within your control:

Actions – Although it might not feel like it, your own actions are completely within your control, although these can be influenced by your thoughts, and emotional and physical states. Your mind can only make suggestions to you; what you do and whether you act on these suggestions is up to you.

Aspirations – These are the things you care about, your goals and your values. While others may have an influence on shaping these, they are yours alone to choose. These include things you care about enough to do, even if no one else ever knows about them. Being aware of and connecting to your own values means that you can consciously prioritise and commit to investing in the most meaningful aspects of your life.

Attitude – This is the way in which you live your actions and aspirations. An attitude of willingness and seeing everything you do as a choice is one that fosters positive experiences. When we do things grudgingly or resentfully it damages our own and others’ experiences. Basically, if you’re going to do anything, do it with an attitude of willingness.

As these are the only things we have complete control over, where possible we can use them to influence other things, but need to apply acceptance where not. Acknowledging and letting go of what is out of your control while taking full control of what is possible is the most helpful approach to adopt.

It’s important to maintain perspective on an unwanted or difficult situation and ask how you might grow from it. As an exercise, ask yourself these questions, writing the answers down:

• Have you ever dealt with a similar situation and what helped you get through that?

• What resources and support might you need to help you deal with the situation in the best way possible?

• How might you look at the situation in a year, two years, or more? How might someone else view things and how would you encourage them to respond?

Ultimately, while we’ve evolved to dislike change and uncertainty, it’s an unavoidable part of life and a necessary part of successful growth. Essentially, uncertainty and possibility live in the same house, so if you want one, you have to be prepared to deal with the other. Try to have a growth mindset, seeing failure as part of the learning process and challenging times as springboards to improving your abilities.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

Because we’re hard-wired to behave in ways that offer short-term relief, when a negative event or change throws us off course, we may turn to what feels like a quick fix. A study looking at coping strategies identified drinking alcohol, shopping, surfing the web, eating and playing video games as the most common coping strategies used, but they were also rated as the least effective by those that used them.

The most effective strategies identified included exercise, reading, listening to music, meditating, spending time outdoors, being with friends and family, and engaging in creative hobbies. These are sometimes referred to as ‘seeds vs switches’. Coping behaviours that are switches are ‘quick fixes’ that numb unpleasant experiences, but you don’t grow psychologically from them. Seeds (such as exercise or meditation), meanwhile, take time and effort, but they provide growth and longer-term solutions.

Read the article on addiction on page 56.

One of the most effective solutions for me is talking. Often you don’t want to talk when you’ve lost or things aren’t going your way, but discussing it with people who have some experience and understand what you’re going through can really help. Over the years, I think you become better at opening up to people.

CHRIS HUGHTON

Depression is common and can have a damaging impact on life and work. However, there are things you can do to reduce the risks and there is plenty of support available should you need it.

Words: Dr Allan Johnston

One in four of us will suffer from a mental health problem at some point in our lives, and the other three will suffer from at least one of a range of issues that affect mental wellbeing. Of the mental health problems, depression is one of the most common forms.

As with many other mental health issues, low mood and depression exist on a spectrum. At one end you’ll have very positive mental health, if you’re in the middle you may have a mental health problem, such as stress or low mood, and if you’re at the other of the spectrum you may have a mental illness, such as depression.

Depression is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as experiencing low mood, reduced energy, reduced activity and other associated symptoms, for at least two weeks. The symptoms experienced are both biological and cognitive and may have biological, psychological and social causes.

Psychiatrists think of mental illnesses such as depression in terms of a bio-psycho-social model because of these three interlinking elements.

Biologically, we know that individuals with depression have a reduced level of neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin and noradrenalin, in the mesolimbic cortex, which is the area of the brain that computes all factors related to mood. That includes memories, what you notice, see, hear, taste, smell and touch, and how you think about yourself and the world around you. With reduced levels of these neurotransmitters, an individual is less able to recall happy memories or to notice positive things. Antidepressants work by boosting the levels of these two neurotransmitters.

Reduced sleep or, rarely, an excess of sleep

Reduced appetite, leading to weight loss

Reduced energy levels

A lack of pleasure at things you’d normally find enjoyable or motivating (known as anhedonia)

Reduced concentration

Negative thoughts about yourself, the future or the world around you

Common cognitive symptoms of depression include negative self-esteem, feeling worthless, and perceiving negative things about the world around you or your future in it. There is, of course, interaction here between the biological and the psychological so, for example, if you’re not noticing the positive things around you or are less able to recall positive memories you’re more likely to feel negative and pessimistic, and to doubt yourself.

Finally, if you have a problem relating to your housing, finances, relationships, education or employment it can also affect your psychology and biology. If you experience a sudden negative life event, or a gradual deterioration in one area, it can impact on your mood and, as a result, cause biological and psychological symptoms. For example, if an individual loses their job it might cause them to doubt themself and their abilities. They might then stop eating and sleeping well and cancel engagements with friends.

Because each part of your bio-psycho-social health affects the others, your mood can spiral downwards and, if problems are not properly acknowledged and addressed, mental health issues such as low mood can become mental illnesses. It’s important, therefore, to be aware of how you’re feeling and note any changes in your behaviour or mood.

It’s worth remembering, however, that if you do the right things, your mental wellbeing can spiral in a more positive direction. Even if you consider your mental health to be good, it could probably be better, so you should always be looking for ways to maintain or improve your mental wellbeing, just as you might your physical health.

Biological, psychological and social actions can all make a positive difference. For example, you could try to improve your sleep routine, eat more healthily and avoid maladaptive behaviours for stress, like drinking alcohol excessively, smoking or gambling. You could take more regular exercise, speak more to friends and family who you trust, and be proactive about your personal and professional development.

If you are aware of what support is out there you can get help when most needed or support a colleague with good advice and signposting. The ability to recognise the support that’s available to you, to access it when necessary and to feel grateful for it is what’s known as ‘perceived social support’ and it has been found to be one of the main components of resilience.

It may be helpful to conduct a personal support audit, thinking about who you would turn to for support, what you would turn to them for, how you would contact them and what they are able to provide.

A wide range of professional support is available, including through the LMA, your GP, the 111 out-of-hours GP phone line, and the Samaritans. Every A&E department has a mental health department that can provide support in a crisis. This is what you might term ‘downstream’ support, but further ‘upstream’ there are also important services available through the LMA, in areas such as legal support, career advice, continuous learning and mentoring. Work-based stress, redundancy, career insecurity, relationship problems, and ill health can all contribute to feelings of low mood and depression. Therefore, anything that helps you to deal with them and feel good about yourself and the world around you is hugely valuable for your continued mental wellbeing.

Anything you can do to improve your mental health reduces the likelihood of you getting a mental illness such as depression.

1 Find ways to improve the quantity and quality of your sleep with a good routine

2 Improve your diet

3 Get outside more

4 Get regular exercise

5 Visit your health professional regularly, as health concerns such as chronic pain can contribute to low mood

6 Invest in personal and professional relationships

7 Do more of the things you enjoy doing and are good at

8 Be aware of stressors away from the job (e.g. house, finance, family) and get help if need be

9 Be more self-aware; note how you’re feeling, how you think about yourself and see yourself

10 Consider what support might you benefit from, including ‘downstream’ support (e.g. psychiatrist and mentoring) and upstream support, (e.g, financial support and professional development)

There are times when people feel so low that they have unhelpful thoughts, which may relate to ending their lives. At that point, it’s vitally important to seek help. Suicidal thoughts are not permanent – they come and go – but at the time that you have them they can present as a risk of harm to self. It’s important to know in such moments that you are not alone. You deserve support and it is available out there for you. This may come from a range of confidential sources, including the LMA, your GP, the Samaritans and your local A&E.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

Recognising the support that’s available to you, accessing it when necessary and feeling grateful for it is key in resilience. Think about who you would turn to for support, what you would turn to them for, how you would contact them and what they are able to provide.

After I lost my job, I suffered from depression for around a year. Three or four months in, I found that I was wallowing in my low mood, and actually doing things to make myself unhappy. I’d become almost comfortable in that state. The feelings were very much like grief. I wasn’t thinking right, I was over-thinking everything, and focusing on regrets and all things negative.

I rang the LMA’s confidential helpline for support and I had counselling, which helped a little. The biggest turning point for me, though, was reading a book called ‘Stop Thinking, Start Living’. It put the ball back in my court by helping me to refocus and retrain my mind. I learned I needed to think of anything else, even neutral things to stop the cycle of negative thoughts.

My mood improved over the course of a few months and, in particular, I found it helped to be away from my normal home life for a while, to have some space to put the strategy in place.

I’m sure that if I’d known then what I know now about the tools you can use to have more control over your thinking, I would never have got into that difficult place to begin with.

Anxiety is probably the most common mental health problem and can present in many forms, with symptoms either mild or severe. Being aware of any anxious feelings and what triggers them is important in reducing the symptoms.

Words: Dr Allan Johnston

Anxiety has many forms. These include simple phobias, where you are afraid of a specific thing such as heights, or more complex phobias, such as agoraphobia and social phobias, where you feel anxiety in large busy areas or when making small talk with strangers.

There are also what are known as Generalised Anxiety Disorders, where there’s a high level of background anxiety in response to a range of factors. Panic attacks, where someone has episodes of acute anxiety for a short period of time, or more complex anxieties such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are also types of anxiety. What they all have in common are their biological and psychological symptoms. Biological symptoms include muscular tension, shortness of breath, palpitations in the chest, nausea or vomiting, tremor, sweaty palms, and feeling

hot, or dizzy and faint. These often go hand in hand with psychological, or cognitive, symptoms, such as fear of a particular situation.

In response to anxiety people often fear that they’re going mad or are going to die. This form of cognitive anxiety, known as catastrophising, causes a person to over-think things or think too far ahead. While this response would have been beneficial in fight-or-flight events, with anxiety it is excessive and inappropriate to the situation.

Because the biological and psychological symptoms affect one another, things can easily spiral. For example, as a person starts to feel anxious their breathing and heart rate may speed up, causing them to panic that they’re having a heart attack. This cognitive panic may cause breathing and heart rate to increase further, which leads the person to feel more anxious and the spiral continues. There are times when anxiety might also present itself as anger, causing you to become unusually irritable or to speak out of turn in a way that isn’t normal for you. It’s important, here, to be aware of how you’re feeling and to recognise your triggers, the things that bother you or set you off. There may, for example, be an unresolved issue or vulnerability from your past that means you resort to anger when feeling anxious as a form of defence.

Simple phobias

Complex phobias, e.g. agoraphobia and social phobias

Generalised anxiety disorders, e.g. a high level of background anxiety

Panic attacks

Complex anxieties, e.g. OCD and PTSD

Other unhelpful approaches could include the use of drink or drugs to self medicate symptoms of anxiety. While these may mask the symptoms in the short term they do not treat anxiety and can lead to worsening symptoms or other issues such as addictions.

With anxiety, it’s also important to recognise what in the situation is within your control and what is outside of your control. Focusing your energy on the factors under your control can be helpful. No amount of anxiety will change something that is outside of your control or bring it within your control.

As with depression and low mood, symptoms of anxiety lie on a spectrum. While some symptoms will be mild and have only limited effects on your life others could be severe and debilitating. For this reason, good self-awareness is essential if you’re to recognise and acknowledge the extent to which anxiety is affecting your life and work.

If your symptoms are constant or at times severe and are having an impact on how you function or live your life day to day then it’s certainly worth seeking professional help and support, whether through your GP or through the LMA. A doctor or psychiatrist will be able to recommend a range of effective treatments for anxiety, including counselling, CBT therapy and antidepressant medications.

We all have some degree of anxiety, and whether your symptoms are mild or severe there are likely to be things you could do to improve your mental health. Various anxiety management therapies exist that can help with the biological or physical symptoms, including deep breathing, progressive muscular relaxation, meditation, relaxation and listening to music. Meanwhile, if you’re over-thinking things or are starting to catastrophise, cognitive strategies such as mindfulness can bring you back to the moment, helping you to think only of the problem or situation immediately ahead of you. Talking to trusted people will help let out some of your worry.

A type of CBT therapy known as ‘graded exposure’ can also help with some forms of anxiety. With graded exposure, you take on a challenge one small step at a time. If, for example, you tend to feel anxious about speaking in front of a large audience, you might start with addressing a close friend, then a small group of colleagues and work up in increments to speaking to a larger audience. In football management, such graded exposure to potential stressors won’t always be possible, as the job can be full on from the first day. However it’s worth considering it before starting your first role. Think about where your biggest anxieties lie, and how biological and cognitive strategies, and methods such as graded exposure and professional support might help you to deal with them more effectively.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

1 Manage the biological symptoms through deep, progressive muscular relaxation, meditation or listening to music

2 Avoid over-thinking and catastrophising by using mindfulness to bring you back to the moment

3 Share your thoughts or concerns with people you trust

4 Try ‘graded exposure’, acclimatising yourself gradually to whatever it is you fear

5 Recognise when your anxiety is affecting your life and work and seek professional help

Muscular tension

Shortness of breath

Nausea or vomiting

Palpitations

Tremor

Sweaty palms

Feeling hot and flustered

Fear of a particular situation

Fear that you’re going mad or are going to die

Catastrophising (over-thinking things and thinking too far ahead)

Bursts of anger or irritability

While it might be tempting to seek short-term relief from stress and anxiety, alcohol and addictive behaviours such as gambling can have serious long-term impacts on your life and work.

Words: Dr Tim Rogers

Humans are hard-wired to look for immediate or quick relief during difficult times, so when we feel stressed, anxious or unhappy we may turn to short-term ‘fixes’. Our brains all have what can be considered reward circuitry, a network centre of neuronal wiring that is involved in representing pleasurable responses to enticements like food, sex and gambling. It is likely that changes in other brain areas are important too, such as the ‘amygdala’, where negative emotions and anxiety are processed.

Alcohol dependence, one of the most common, often runs in families. This is partly down to genetics, but also because substance use is influenced by your family’s attitudes to alcohol and the environment you grow up in. Free will is, however, still a hugely significant factor and many people with dependence are supported to find the will power to control or stop their drinking.

Most of us who drink alcohol can recall times when we drank too much or even periods when the way in which we were using alcohol felt unhealthy. At what point, though, does this become dependence?

When the phrase ‘addicted’ is used about alcohol, many people assume that this must mean the experience of withdrawal symptoms. An example can be feeling shaky or sweaty if not drinking, symptoms that are relieved by consuming more. Although this can occur in severe cases of addiction, it might be surprising to hear that anyone who is drinking regularly will have a degree of alcohol dependence.

The exact medical definition can vary slightly, but the main feature of an addiction is loss of full control over how you drink. Impaired control over drinking can begin with noticing that you intend to drink a certain amount but, when it comes to it, you end up consuming more. Wanting to cut down or stop drinking but not managing to do so is also a warning sign. In other words, you don’t always have to be drinking to extreme levels to become dependent on alcohol.

Other important changes to look out for include tolerance. People who drink heavily tend to keep increasing the amount they drink because they need to consume more to get the same effect.

Another key consideration is to honestly ask yourself about the extent to which alcohol has caused a problem for you in different areas of life. How often has drinking meant that you haven’t been able to do what you should do at work or at home? Has it caused any problems in relationships? Has anybody close to you commented that it might be worth cutting down? Continuing to drink in these situations is a warning sign, especially if alcohol has caused or made a physical or an emotional problem feel worse.

Our brains are wired to experience stress, anxiety and often to think negative things. This is normal and a little stress is often helpful for how we perform. However, it’s important to have a range of healthy strategies to deal with excess worry. Alcohol can, for a short while, relax us and increase confidence. Alcohol can of course help social enjoyment too but, if you’re not feeling good, the rapid escape that it offers from negative emotions can be powerful and difficult to avoid. The irony is that alcohol is a depressant. Longer-term alcohol use can therefore cause major depression and a wide range of other unwanted psychological and physical health problems.

It is important to understand the effect of alcohol on sleep in particular, especially given the impact that poor sleep can also have on day-to-day mental health, including mood, concentration and decision making. After a long and demanding day, it may be tempting to have a drink or two to help you sleep. Whilst alcohol can help you drop off, drinking disrupts your normal sleep cycle. Regular drinking can have a surprising impact on the quality of your sleep.

If you think you may have an issue with drinking, it’s worth seeing first of all how easily you are able to go a few days without any alcohol. If you find it difficult, ask yourself to what extent the after-effects of alcohol or your dependence on it are impacting on your performance at work, your home life, sleep and overall wellbeing. Support is available via the LMA’s in-house sport and performance psychiatrists, in the strictest confidence.

An understanding of the risks of gambling is important to safeguard your personal health and wellbeing and your performance as a manager.

Words: GambleAware

Two-thirds of the adult population of Great Britain gamble, and for most of them it’s an enjoyable leisure activity. However, an estimated two million adults experience some level of harm from their gambling, with negative impacts on themselves, their families and their communities. For around a third of a million adults it develops into a gambling disorder, a behavioural addiction recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO), and consequences become more severe. These are not just financial; they can include depression, anxiety and loneliness to the extent that some people will contemplate or attempt suicide.

However, it’s not always easy to spot the outward signs that someone is experiencing negative effects of gambling. Even at its most severe, it can be a hidden addiction, out of sight of family, friends, colleagues and health professionals.

Common signs include:

• Spending more money and time on gambling than you can afford.

• Having arguments with family or friends about money and gambling.

• Losing interest in usual activities or hobbies like going out with friends or spending time with family.

• Borrowing money, selling possessions or not paying bills in order to pay for gambling.

• Neglecting work, school, family, personal needs or household responsibilities because of gambling.

• Feeling anxious, worried, guilty, depressed or irritable.

If your gambling has become an addiction, you may need treatment through a specialist service to help address both your gambling and any underlying issues. This looks to not only reduce the impact of the gambling on your life, but also improve your overall mental health.

Thankfully there is plenty of advice, support and treatment available, and these can be very effective in reducing the negative impacts of gambling. A free, confidential advice, support and help is available 24/7 via the National Gambling Helpline on 0808 8020 133.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

ONCE AT A CERTAIN LEVEL, MANAGERS TEND TO FORGET THE KEY ROLE THAT PROFESSIONAL RELATIONSHIPS PLAYED IN THEIR LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT

STEVE JOHNSON PAGE 83

Understanding why you’re here and what you’re doing it all for will help you to remain committed and resilient through the toughest times.

Words: Jeremy Snape

It takes incredible commitment to become an expert in any craft. To dedicate your life to something you need a passion deep enough to drive you forward through years of hard work and sacrifice, and to pick you up after setbacks and disappointments.

It’s essential, therefore, that before you set out on your career path you’re sure it’s the right one and you have sufficient motivation and commitment to last the journey.

We tend to think of motivation in terms of goals, awards, league positions or financial gains, but this is only ‘extrinsic motivation’, where we’re driven to achieve a particular outcome, or indeed avoid one, such as redundancy. While an extrinsic motivation may be a useful way to check your progress along the way, making it a destination in itself is dangerous, because the outcome you are

working so hard to bring about is unlikely to be entirely within your control.

What’s more, as these kinds of drivers are short term, when they dominate your thinking you are more likely to make short-term, short-sighted decisions rather than looking for sustainable long-term solutions.

When we look deeper into the motivations of people who excel at their crafts we see that they focus as much on their ‘intrinsic motivations’ as their extrinsic ones. These are driven by internal rewards, and common ones include the search for learning and continual improvement, the freedom to choose how you get the job done, purpose and belonging. Unlike extrinsic motivations they don’t stop once a season ends or a competition is over.

When you have a balance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations it’s a potent mix that may help you to stay the course, even through adversity and setbacks.

Periods of adversity, especially extended ones when it may seem your goals are slipping away, can be painful. They may even result in feelings of shame. Research around motivation and resilience shows how, with the right mindset, we are better equipped to deal with such situations.

Martin Seligman’s work around resilience provides a framework of three Ps for how we explain things to ourselves: Personalisation – how much we think something relates only to us; Pervasiveness – how much of our wider job, identity or whole lives is affected by the issue; and Permanence – how long we think the situation will last.

If, for example, someone with low resilience misses a penalty in a crucial game, their self-talk might sound something like this: “This is typical of me, why is no-one else experiencing this” (personalisation), “I’m not good enough” (pervasiveness) and “This has been going on for years and I can’t see it changing” (permanence).

Contrast this interpretation of events with someone with higher resilience. “Everyone misses a penalty at some point” (not personalised), “My thinking as I put the ball down wasn’t clear enough” (specific skill, not pervasive across my whole identity) and “I can work in training to make sure it doesn’t happen in the future” (can be improved quickly, not permanent at all).

Mastery – the search for learning and continual improvement

Autonomy – the freedom to choose how we get the job done

Purpose – making a contribution to something bigger than ourselves

Belonging – feeling a deep connection to a community that shares our dreams, values and beliefs

Goals – achieving targets set by someone else

Recognition – winning awards or titles or reaching a certain position

Financial gain – achieving for money or other tangible incentives

Pleasing others – the desire to impress or make people proud

Fear – perhaps of losing your job or losing face

At Bristol City Women I have a board with our vision, goals and philosophy on it and when I’m feeling low or a bit lost it’s really helpful to be able to go back to that and remind myself why I’m doing what I’m doing. Keeping my motivations and the end point in sight helps me to avoid getting too lost in the emotion of things.

We can all recognise this in ourselves. It goes beyond simply choosing optimism over pessimism and challenges us to question our ability to deal with the inevitable pain and suffering that the quest for high performance brings.

Vice Admiral James Stockdale from the US Navy was captured in the Vietnam War and, as well as enduring eight years in a prisoner of war camp, needed to help as many of his men as possible to survive the torture and desperation of their imprisonment. He realised that the people who survived were not the optimists, the ones who hoped they’d be out by Christmas, Easter or summer each year, and were heartbroken when they weren’t. It also wasn’t the pessimists, who believed their life would end in the camps; their helplessness became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Those who survived were the ones who were able to embrace the brutal reality of their current situation while being driven by the dream of being reunited with their loved ones. Commander Stockdale himself believed that this would be his most powerful life event and, by transcending it, he would be able to share his story and help many people in the future. This ability to endure short-term pain because of a longer-term inspirational goal, centred on oneself, seems to be key.

If you enter a new role or season armed only with optimism, you’ll feel the full force of the disappointment if things don’t pan out as you’d expected. When you anticipate and accept that tough times lie ahead and are able to stay connected to your purpose and your intrinsic reasons for doing the job, you stand the best chance of steering through such periods unscathed. Perhaps the perfect antidote to adversity is seeing every challenge as a valuable learning experience and focusing on the benefit that your work brings to others. We need to think less about our short-term survival and more about the bigger picture, including how much we and others grow during both periods of success and adversity.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

Consider how you’re looking at things from the three sides (Martin Seligman):

Personalisation – how much does the situation relate to you in particular?

Pervasiveness – how much of your job, identity or whole life is affected?

Permanence – how long will the situation and its effects last?

For example, after missing a penalty, you might say to yourself:

RESILIENT VS NON-RESILIENT

“Everyone misses a penalty at some point”

“This is typical of me, why is no-one else experiencing this”

“My thinking as I put the ball down wasn’t clear enough”

“I’m not good enough”

“I can work in training to make sure it doesn’t happen in the future”

“This has been going on for years and I can’t see it changing”

Having an identity and self-worth that are built on things other than your profession is fundamental to mental wellbeing and resilience.

Words: Jeremy Snape

For managers just entering the profession, it’s important to be aware that the job can become all-consuming if you allow it to be, eating away at free time, hobbies and relationships.

It’s natural that your profession should be seen as such a central part of your identity – it’s where you spend much of your time and, if you’re lucky, where you share your passions and strengths. Unless you’re a household name, ‘What do you do?’ is often the first thing a stranger will ask of you.

However, the psychological trap that many of us fall into is letting our jobs define who we are. We have a human need for acceptance and to feel good enough and given that it tends to be only at work that we get measured, scored and valued in a tangible way, we tend to overplay the importance of our work. As a result, some ambitious people attach around 80 per cent of their self-worth to their professional lives, leaving only a fifth for their roles as husbands, wives, sons, daughters, mentors, charity ambassadors, and so on.

In elite sport, perhaps more than any other industry, ‘who we are’ is made up of ‘what we do’. To survive long enough to succeed in management you need absolute dedication, passion, hard work and tenacity, so it’s easy for the job to become all-consuming.

But while it might seem almost a prerequisite of the job that you give it your all, it can become a problem when it defines you. This is especially true if you lose your job or step away from the profession, for whatever reason. One sport psychologist said that professional athletes are the only people to die twice, once with the traumatic loss of their athletic identities on retirement and again in later life. Reinvention can take years and is often a painful process as you learn to be comfortable giving the response ‘I used to be a….’

In the pressure cooker of management, having a balanced identity and self-worth, built on a range of interests and roles, is essential to good mental health. When you’re happy overall with who you are and judge your worth not only by what happens on the pitch, but also by your role as a parent, a friend, mentor or ambassador, you’re better prepared and better supported in the face of setbacks and disappointments, criticism and comparison. What’s more, when you do hit a hurdle, you’ll bounce back more quickly and avoid spiralling into negative thoughts.

Remaining connected to people and interests outside of football is also important in minimising feelings of loneliness and isolation, which are common among leaders at the top of their game.

Think of your identity like the ropes holding up a tent, the more you have pegged down, the more stable the tent is. Should any of the tent pegs come unstuck, there are others to take the strain, but with only one rope (your career) firmly in the ground, you’re likely to be shaken by even the slightest gust of wind.

Developing a healthy identity and self-worth starts with awareness. For most of us, our careers become a blur of months flying by and we rarely pause to reflect. Starting to notice where you help people or add value in a team can be a powerful starting point. In a world that celebrates personal goals and short-term sales figures, we often underplay the importance of working selflessly as a team.

When your career is going through difficult times, try helping other people to shine through your advice, mentoring or support. These ‘invisible’ efforts often go unnoticed, but by consciously choosing to do the right thing on these difficult days you are reinforcing to yourself that you have so much more to offer. You need an incredible level of determination and focus to be successful in your career, but by understanding your wider strengths and where you add value to other people’s lives, you will gain all important perspective and stability in return.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

To become a successful manager you need drive and determination, so it’s only natural to put the job before other things. Regardless of what you do, it’s always on your mind; it’s all-encompassing and separating yourself is difficult but essential if you’re to keep clarity of mind, which is a big part of resilience.

WALTER SMITH OBE

You can’t put a price on things like family and health. It’s really important to remember that and to recognise what you have away from the profession. It takes the pressure off when you have stability in your life that isn’t affected by football.

While I love football management and want to be successful at it, I need a break sometimes. It’s good to have other interests. I love music and being with the band takes me away from thinking about work, as does being with people who are neither involved with football nor are in the public eye. Singing with the band is the biggest release, because the only thing on my mind is getting the lyrics or the tune right. Football is a bubble, and while it’s a great bubble to be in and one you have to embrace, you can’t let it take over.

People compare themselves to others and worry. You have to look at yourself sometimes and say, I’ve done pretty well to be where I am, because this world isn’t easy. If you can look in the mirror at the end of the day and know you did your best and treated everyone well, what more can you do?

Good self-awareness equips you to minimise the negative impact when you’re at your worst and maximise the positive impact when you’re at your best.

Words: Dr Steve Bull

Self-awareness is about knowing yourself really well. In particular, people who have high self-awareness are tuned into their strengths and understand what they’re like when they’re most effective. As a result, they’re able to deploy their strengths and manage themselves to maximum effect, with the most positive impact on others.

Equally, self-aware people are tuned into what happens when they are least effective, so they recognise what their potential stressors are, or what triggers a negative reaction in them, and what is most likely to derail their performance. This makes them more resilient, because they can recognise quickly when they’ve been knocked sideways and understand what they need to do to manage the pressure, stay calm in the moment and return to a positive frame of mind.

As we’re all different and have different triggers and stressors, it’s essential that we each recognise our own and how we react to them and consider how we might manage such situations better.

Understanding that we are all different is key to not only getting the best out of ourselves, but also to managing others effectively. For example, some people are introverts, others are extroverts and some are a bit of both. Introverts need time to themselves to think things through away from other people. It re-energises them and so is particularly important if they’re tired or are trying to deal with a difficult situation.

Extroverts, meanwhile, are energised by being around other people and tend to be at their best when in company. It’s important to understand and acknowledge what type of person you are, what energises you and what you need in order to deal with challenging periods. As leaders, we all need to be energised and focused, but we need different strategies to achieve that. Because personality type has such a profound impact on personal effectiveness and on your ability to manage others, it’s advisable to look into it early on in your career. However, while personality tests can help to highlight key traits such as extroversion and introversion, they have limited benefit when done in isolation. Far better is to work with a coach or mentor so you have the opportunity to translate the results into something meaningful and practical.

You have to find time to keep yourself fresh and rejuvenated, so that you can remain effective and efficient in the role and set a good example to those around you. The challenge as a manager, though, is fitting it all into the working day while still looking after everyone and everything else that comes with the job. Understanding yourself and what you’re good at and not so good at is really important in this.

NIGEL ADKINS

Some people are naturally more self-aware than others, but like any skill it’s something we can all become better at with practice. Effective coaches and leaders invest in that learning process and accept that it never stops. You’re always changing, so you have to keep your understanding of yourself and what makes you tick up to date. Be proactive and constantly work at it.

That means taking time to reflect on yourself, your strengths and weaknesses, and your stressors and how you react to them. Feedback is essential here, and some of the most basic questions you can ask people include:

• What am I like?

• What is it I do when I’m at my best and having the biggest positive impact on those around me?

• What do you see in me when I’m at my worst?

Working with a coach or mentor is another great place to start when looking to improve your self-awareness, as they can give you observational feedback and challenge you to think about how you operate. They may also be able to help you work through a profiling process, such as a leadership assessment or personality test.

Self-aware people are good at reviewing their performance, at the end of each day or week or after a significant event. Take time to ask yourself what happened, why you chose to do what you did and whether it had a positive impact. If it didn’t work, why was this?

What’s most important in this process of reflection is that you’ve either got to be challenging yourself or be challenged by others. We all have a perception of the impact that we make on others, but often it’s not terribly accurate. It’s only when we seek the opinions of others that we can really develop self-awareness.

For further information or support, please contact the LMA Member Services team on 01283 576350 or 07855 022117.

1 Recognise your strengths – what are you like at your best and how can you deploy your strengths more often?

2 Identify your stressors – what triggers the worst in you or causes you to be least effective? How might you deal with those stressors better?

3 Seek feedback – asking questions about yourself takes courage, but it’s essential if you want to understand the real impact you have on other people.

4 Assess your individual needs – a personality or leadership test, taken with a coach or mentor, can help identify how you work best and what you need in order to cope better.

5 Reflect on your performance – routinely review how effective you were, how well you dealt with situations and how might you have done things differently.

6 Work with a coach or mentor – having someone who can challenge you, provide feedback and help you to self-assess is invaluable.

I’m a huge extrovert; I love being around people and I thrive off interaction. It’s important to know yourself and your needs, but also to recognise that not everyone is the same. Some people need their own space to think and be away from it all.

GARETH AINSWORTH

Good psychometric tools can be the bedrock of self-development, holding up a mirror, confirming what makes you who you are and to what, therefore, you can attribute your successes. Conversely they can help you decide if you can and should change to improve certain qualities, behaviours and traits.

Such tools need to be approached with an open mind as they encourage you to self-reflect, using close trusted friends and family to confirm or challenge assessments, and to accept or change their behaviour in any given situation, should they need to.