NEW THINKING

was the wettest recorded May since the historic 2010 flood. As of this writing, June is not shaping up much better. We have only had a few days of 90-degree-plus growing weather. It is shaping up to be a challenging year.

We have some of the best turf managers in the industry and I know you will find a way to have a tremendous surface. If you don’t know an answer, ask a colleague or one of our terrific vendors. Someone will be there to lend an ear. Stay positive. At the time I am writing this, there are 70 days, 23 hours, 50 minutes, and 5 seconds until college football kickoff.

As always, if you have any questions or ideas, please reach out to a board member. We are currently nailing down the speakers for the 2026 TTA Annual Conference. We are hoping to bring you another great event.

Hope to see you soon.

Ryan Storey

TTA President

The Tennessee Turfgrass

Tennessee Turfgrass is the official publication of The Tennessee Turfgrass Association

400 Franklin Road

Franklin, Tennessee 37069 (615) 928-7001 info@ttaonline.org www.ttaonline.org

PUBLISHED BY

Leading Edge Communications, LLC 206 Bridge Street Franklin, Tennessee 37064 (615) 790-3718

info@leadingedgecommunications.com

EDITOR

Dr. James Brosnan

TTA OFFICERS

President Ryan Storey Line to Line LLC

Vice President Ryan Blair, CGCS Holston Hills Country Club Secretary / Treasurer

Crossroads Sod Farm

Past President

Chris Sykes

Tellico Village

Executive Director

Melissa Martin Tennessee Turfgrass Association

TTA BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Jason Bradley Ben Dodd

Dan Johnson

Ashley Gaskin

Cal Hill

Jeff Huber Bill Marbet

Wells McClure Bob McLean

William Newsom

Kevin Noble

TTA ADVISORY MEMBERS OF THE BOARD

Bill

Stars of the Industry Awards recognizes outstanding individuals in the turf industry. Please try to keep in mind any operations or individuals that make a statement to you or the industry and nominate them for a Stars Award.

You do not have to be a member to nominate someone for an award.

One of the most prestigious and highest recognitions bestowed on a Tennessee turfgrass professional by the Association is the Tom Samples Professional of the Year Award. TTA members are given the opportunity to nominate those who they feel have made contributions to the turfgrass industry.

This award recognizes outstanding contributions by individuals, organizations, businesses, educational institutions, and agencies for successful projects or activities designed to improve the environment through wildlife habitat preservation, water and resource conservation and reduction, and educational outreach.

The TTA recognizes that our members make personal and professional contribution to our industry and to the organization you serve. This award is presented to a sports field which has demonstrated those qualities.

The TTA recognizes that our members make personal and professional contribution to our industry and to the organization you serve. This award is presented to a golf course which has demonstrated those qualities.

Following the success of its 2024 debut, the BEACON program is returning this fall! Designed to connect emerging professionals with leaders across the turfgrass industry, BEACON brought together students and employers from nationally ranked golf courses, leading agrochemical companies, and other key sectors in its inaugural year.

We’re excited to announce that BEACON 2025 will take place October 14–15 in Knoxville, Tennessee. Mark your calendars. This year promises to be even bigger and better. Additional details will be shared later this summer.

For questions, please contact Dr. Becky Bowling at rgrubbs5@utk.edu.

In the meantime, you can read more about last year’s event: https://www.turfnet.com/news.html/uts-beaconprogram-connects-dots-between-students-employers-university-research-r2051/

January 5 – 7, 2026 | Embassy Suites | Murfreesboro, TN

Don’t miss this opportunity to keep up with all the latest news, information and research from leaders in the industry! Our education committee is working hard to plan another excellent program that includes topics that will help you grow in knowledge and advance your career.

Awards, pesticide sessions, tradeshow and excellent networking opportunities are also on the docket – you don’t want to miss it! Follow us on X @TnTurfAssoc or visit ttaonline.org for updates.

Mark your calendar for these upcoming events and check ttaonline.org for more events throughout the year.

AUGUST 5, 2025

11:30 AM (EDT)

Turfgrass Tuesday –10 Years After a Pesticide Ban in Connecticut Zoom

SEPTEMBER 2, 2025 11:30 AM (EDT)

Turfgrass Tuesday –Behind the Curtain at Pinehurst

Zoom

OCTOBER 7, 2025 11:30 AM (EDT)

Turfgrass Tuesday –FIFA World Cup Update

Zoom

OCTOBER 14, 2025

BEACON 2025

Knoxville, TN

By Dr. Brandon Horvath , Professor, Turfgrass Pathologist, UT Plant Sciences

Tall fescue is a prominent lawn grass choice especially in the Middle and Eastern Tennessee regions where cool-season turfgrasses are more prevalently used. Brown patch, caused by Rhizoctonia solani, is the most damaging pathogen affecting tall fescue lawns throughout Tennessee. This fungal disease can transform a lush, vibrant lawn into a patchy, unsightly expanse when conditions favor disease development.

While fungicide applications are often necessary for severe outbreaks, proper fertility management serves as the foundation of an effective preventative strategy. Fertility practices directly influence plant health, disease susceptibility, and recovery potential. Unfortunately, many common fertilization practices can actually make the problem worse. Supported by several years of research findings, we have recently employed a different approach that maintains some growth turfgrass potential via fertility that enables infected plants to recover following disease pressure. Understanding the relationship between fertility inputs and disease development will allow lawn care professionals to implement proactive management programs that reduce disease severity while maintaining a quality turfgrass stand. This article explains how different fertility approaches affect brown patch in tall fescue lawns and provides practical ideas for turfgrass managers to implement these approaches in a lawn care setting.

Understanding Brown Patch Disease

Rhizoctonia solani is a soilborne fungal pathogen that is present in most turfgrass environments. The fungus survives unfavorable periods as mycelia in thatch and soil. Under specific environmental conditions, primarily with high temperature and humidity, the fungus becomes active and begins to attack the plant.

In tall fescue, R. solani primarily infects the leaf blades and sheaths, creating lesions that eventually result in a circular “patch” appearance. The fungus spreads via mycelial growth, moving from plant to plant through direct contact (Figure 1). Unlike other turfgrass diseases, brown patch does not spread via spores.

Tennessee’s climate creates ideal conditions for brown patch development during much of the main growing season. The Brown Patch pathogen becomes active in response to:

• Temperature thresholds: Nighttime temperatures that consistently remain above 65°F with daytime temperatures between 80–85°F. These conditions typically develop in TN from mid-May through September, sometimes persisting into October.

• Humidity factors: Relative humidity that exceeds 80% greatly increases infection rates. Our humid summer climate, especially during nighttime, will frequently exceed this threshold.

• Leaf wetness: Extended leaf wetness periods of 10+ hours dramatically increases infection rates. Evening irrigation practices, frequent summer thunderstorms, and morning dew are common in Tennessee and contribute to this risk factor.

So, it is under these conditions that the plant becomes most susceptible to fungal attack and infection. Historically, conditions coincide with timing of when recommendations suggest backing off on fertility applications to allow the plant to “harden off”. However, our work has shown that a plant that is not able to actively recover will be in a worse position as multiple rounds of disease take place and decimate the stand.

Nitrogen is the most important nutrient for proper turfgrass growth, and there is a direct and significant impact on nitrogen management with brown patch susceptibility in tall fescue. Traditionally, research has shown that water-soluble, quick-release nitrogen sources (such as urea, ammonium sulfate, and ammonium nitrate) significantly increase brown patch severity compared to slow-release formulations. The main reason for this effect has been that at higher doses, the plant grows more rapidly, resulting in a thinner cuticle and lush, succulent growth. Modern practices, however, allow for much lower application rates of N fertility, and a spoonfeeding approach can often improve turfgrass performance. Using controlled-release nitrogen sources like polymer-coated urea will deliver nitrogen more gradually (Figure 2), which in turn will reduce disease-prone succulent growth while maintaining adequate plant growth for recovery. This relationship is really the key to using fertility to help manage the damage caused by brown patch. Ideally, the turfgrass manager wants the plant to grow just enough that when conditions aren’t conducive for disease, the plant will grow out of the symptoms and recovery will take place. When that condition exists, the turfgrass plants will be capable that when exposed to another disease cycle, some damage will occur, yet recovery will again take place.

Under-fertilizing a turfgrass stand or lawn is much more common today than over-fertilizing. As long as the applicator avoids excessive nitrogen application during high-risk periods, one of the most common fertility mistakes that often leads to more severe brown patch outbreaks can be avoided. By providing the plant with “just enough” fertility, the need for plant growth can be balanced with not overstimulating the pathogen’s ability to attack. I began to change my own perspectives on these recommendations about a decade ago, when some of our research clearly demonstrated that having moderate fertility applied during the growing season led to lower brown patch severity and also a decrease in undesirable competition from bermudagrass encroachment.

3. Research plots showing the effect of a single spring Polymer Coated Urea (3 lbs/1000, Gal Xe One, Simplot) application vs. monthly applications of Urea (1lb/1000) and regular applications of a fungicide for brown patch control. Most of the off-color turf is infested with brown patch damage.

As a result, I began making some adjustments in my recommendations on fertility:

• Late Spring (April-May): Limit applications to 0.5-0.75 lb N/1000 sq ft using primarily slow-release sources as temperatures begin to approach the brown patch threshold. Alternatively, one could use a very slow-release poly coat urea, that would provide ~3 lbs N/1000 sq ft for the April-August Period (~20 wks)

• Summer (June-August): Make low rate applications (0.1–0.2 lbs N/1000 sq ft; ~0.6-1.2 lbs N/1000 total for 3 months) during the highest risk brown patch season. These applications are made to just maintain some turfgrass growth and recovery potential without sparking lush succulent growth. Slow-release sources can also be used.

• Early Fall (September): Use fertilization at 0.75–1.0 lb N/1000 sq ft as temperatures moderate to focus on turfgrass recovery from summer stress and disease pressure.

• Late Fall (October-November): Apply 1.0–1.5 lb N/1000 sq ft, emphasizing root development and carbohydrate storage.

In total, here in Tennessee, managers should target about 4–5 lbs of N/1000 sq ft/year for a quality Tall Fescue lawn. Making these slight adjustments in how we fertilize will help reduce the damage caused by disease while allowing for turfgrass recovery throughout the season, maintaining turf quality.

Effective brown patch management in tall fescue lawns requires an “all-hands” approach centered around proper fertility practices. By understanding the relationship between nutrition and disease development, lawn care professionals can significantly reduce brown patch severity while maintaining acceptable turf quality.

Key takeaways include:

1. Timing is critical: Avoid quick release, high rate, nitrogen applications during high-risk periods (June-August in Tennessee)

2. Source matters: Use slow-release sources to smooth out N release over time mimicking a low rate “spoon feeding” approach

3. Integrate approaches: Coordinate fertility with appropriate cultural practices and if needed, fungicide interventions

4. Prevention focus: Implement proactive programs rather than reactive treatments

Using these research-based fertility practices, I’m confident that turfgrass and grounds managers can significantly reduce the impact of brown patch in client and home landscapes while promoting healthier, more resilient tall fescue lawns.

By J. Scott McElroy Professor, Turfgrass Management and Weed Science, Auburn University

and James D. McCurdy

Professor and Extension Specialist, Turfgrass Management, Mississippi State University

Given the current climate surrounding federal funding discussions, we want to provide detailed information about research outcomes from the ResistPoa project. Our goal is transparency about what taxpayer dollars accomplished when this project received funding. For information regarding this project, please see http://resistpoa.org/

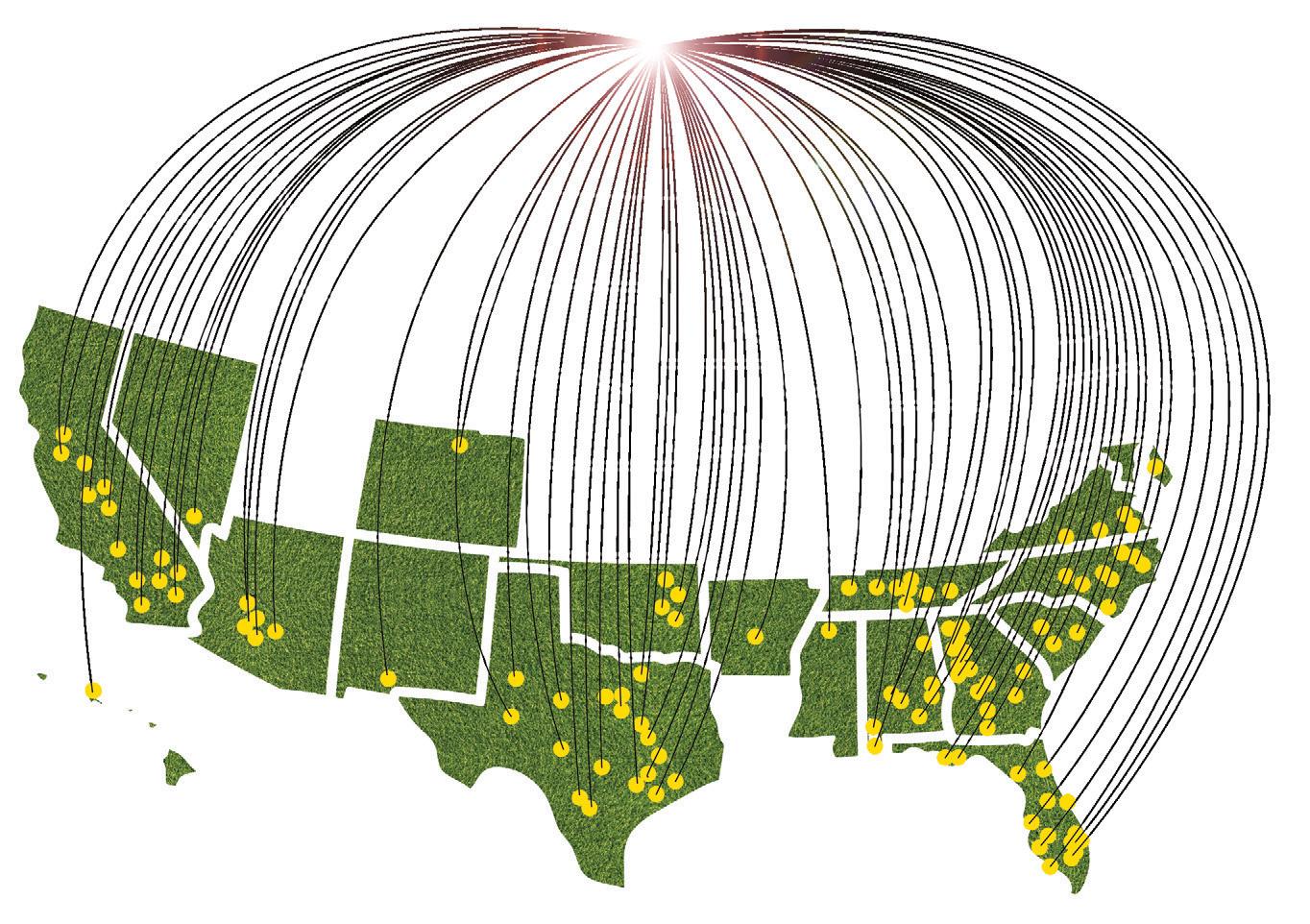

ResistPoa launched in 2018 as a nationwide initiative to tackle the growing problem of herbicide-resistant annual bluegrass (Poa annua) in turfgrass systems. This four-year, $5.7 million project, funded by the USDA Specialty Crop Research Initiative brought together 16 scientists from 15 universities across the country.

The project had clear objectives: develop better management practices for annual bluegrass control, map the extent of herbicide resistance nationwide, and create decision-support tools for turf practitioners. Essentially, we needed to understand how bad the resistance problem really was and give golf course superintendents, sports field managers, and other turf professionals the tools to fight back.

Annual bluegrass might seem like a small problem, but it’s not. This weed costs the turfgrass industry millions of dollars annually in control measures and lost playability. When herbicides stop working, managers face expensive reseeding, overseeding, and intensive maintenance schedules that strain budgets and resources.

Our team’s biggest accomplishment was conducting the first comprehensive national survey of herbicide resistance in annual bluegrass. We collected and tested over 1,300 populations from turf sites across five different climate zones. The results were sobering—by 2023, we documented populations resistant to up to nine different herbicide modes of action.

This wasn’t just academic research. These findings gave turf managers concrete data about what to expect in their regions. Instead of guessing whether an herbicide might work, superintendents could now reference our maps and data to make informed decisions about their control programs.

We dug deep into the science behind why annual bluegrass develops resistance. Through molecular analysis of dozens of populations, we identified specific genetic mutations that allow the weed to survive herbicide treatments. For example, we discovered a novel mutation in the β-tubulin gene that helps annual bluegrass resist popular pre-emergence herbicides like prodiamine.

Decreased down time, increased revenue.

The surface is very “puttable.”

The dots are sand that is level with the turf.

DryJect® is a high-pressure, water based injection system that blasts holes through the root zone and fractures the soil profile. Plus, it automatically fills holes as it aerates.

DryJect® makes a big difference in playability … right away!

But genetics wasn’t the whole story. We also found that annual bluegrass uses other tricks—enhanced metabolism and reduced herbicide uptake—to survive treatments. These non-target-site resistance mechanisms were particularly common with ALS-inhibiting herbicides like foramsulfuron (Revolver) and trifloxysulfuron (Monument).

Research is only valuable if people can use it. Our team tested alternative control methods that don’t rely solely on herbicides. We demonstrated that aggressive fraise mowing (essentially shaving the turf surface) could dramatically reduce annual bluegrass infestations in bermudagrass turf. While this technique isn’t suitable everywhere, it gives managers another tool in their arsenal.

We also examined how cultural practices affect the weed’s competitiveness. Studies in Oregon showed that adjusting irrigation frequency and phosphorus fertilization could influence how well annual bluegrass competes with desirable grasses. These findings are being incorporated into our best management practice guidelines.

What makes ResistPoa unique is that we have included social scientists to study the human side of weed management. Through surveys and interviews with turf managers, we identified real barriers to adopting better practices: budget constraints, risk aversion, and simple lack of awareness about resistance.

We developed a user-friendly decision support tool—essentially a calculator that helps superintendents visualize the long-term benefits of diversified management versus short-term cost savings. This economic modeling helps justify upfront investments in integrated approaches rather than relying on the same herbicide year after year.

From day one, we emphasized getting information to the people who needed it. The project created ResistPoa.org as a central hub for resources, now hosting about 70 educational documents that users can filter by turf system and control method.

We produced a best management practices poster explaining herbicide modes of action and effective rotation strategies. This poster was distributed to over 2,000 stakeholders in print and downloaded more than 1,000 times online.

Our team organized field days, workshops, and webinars across the country. These weren’t just presentations—they were handson demonstrations where turf managers could see control trials in action and ask questions directly.

Perhaps most importantly, we trained the next generation. At least 22 graduate students, 25 undergraduates, and roughly 10 postdoctoral researchers received training through ResistPoa. These students are now professors, consultants, and golf course managers, multiplying the project’s impact.

1.

•

•

•

2. Where is it used?

• High demand athletic fields: football, soccer, baseball, softball, and rugby.

• High traffic areas: Horsetracks, goalmouths, and tournament crosswalks.

The real test of success is whether the turf industry is actually using our findings. Early indicators are positive. Golf course superintendents are referencing our resistance maps to make proactive decisions about herbicide rotations. Instead of waiting for a product to fail, they’re switching to different chemistries based on what our survey showed in similar conditions.

We worked closely with industry advisory panels from the beginning, including golf course superintendent associations, sod growers, and lawn care companies. This collaboration ensured our research reflected real-world conditions and that recommendations fit industry needs.

When preliminary results showed certain populations surviving standard herbicide rates, industry partners helped us quickly alert practitioners so they could adjust rates or tank-mix with other products. Seed producers worked with us to test for annual bluegrass contamination and resistance in turfgrass seed lots.

The project generated over 20 peer-reviewed publications in journals like Weed Science, Crop Science, and Weed Technology. This wasn’t just about meeting academic requirements—these papers ensure the knowledge is archived and accessible to guide future research and management decisions. Our management guides are “Open Access”—you can download them from the Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management Journal.

Our investigators delivered dozens of conference presentations at weed science and turfgrass meetings, sharing results throughout the project’s duration rather than waiting until the end.

ResistPoa created lasting benefits beyond its four-year timeline. The network of scientists, Extension agents, and industry professionals formed during the project continues to collaborate on turf challenges. We’ve seen the power of coordinated research, and that collaboration model is being applied to other problems.

The students and researchers trained under ResistPoa have spread throughout the industry, carrying this knowledge into their new roles. This multiplier effect means the project’s impact extends far beyond the original $5.7 million investment.

Turfgrass represents a $100 billion industry encompassing millions of acres of golf courses, sports fields, and maintained landscapes. ResistPoa demonstrated how targeted federal investment in specialty crop research can protect this industry and the green spaces Americans value.

Annual bluegrass remains a formidable opponent, but the collective action marshaled by ResistPoa has given the industry evidence-based tools to manage this weed sustainably. The project exemplified how integrated approaches—combining science, education, and industry partnership—can tackle complex agricultural challenges effectively.

Bagavathiannan, M. V., McCurdy, J. D., Brosnan, J. T., & McElroy, J. S. (2018). National team to use $5.7 million USDA award to address annual bluegrass epidemic in turfgrass. Texas A&M AgriLife News.

Grubbs, B., McCurdy, J., & Bagavathiannan, M. (2019). Poa annua: A plan of action. Golf Course Management Magazine.

Rutland, C. A., Brosnan, J. T., McElroy, J. S., & Zuk, J. W. (2023). Survey of target site resistance alleles conferring resistance in Poa annua. Crop Science, 63(5), 3110-3121.

McCurdy, J. D., and others (2023). Developing and implementing an integrated weed management program for herbicide resistant Poa annua. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management, 9(1), e20225.

Allen, J. H., and others (2022). Herbicide resistance in turf systems: insights and options for managing complexity. Sustainability, 14(21), 13399.

USDA-NIFA. (2020–2022). ResistPoa Project Extension and Training Outputs. USDA-NIFA Annual Reports.

José Javier Vargas Almodóvar Research Associate II

Turf & Ornamental Weed Science

The University of Tennessee 2431 Joe Johnson Drive 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996 (865) 974-7379 jvargas@utk.edu tnturfgrassweeds.org @UTweedwhisperer

Greg Breeden Extension Specialist, The University of Tennessee 2431 Center Drive 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-7208 gbreeden@utk.edu tnturfgrassweeds.org @gbreeden1

Jim Brosnan, Ph.D. Professor, The University of Tennessee Director – UT Weed Diagnostics Center 112 Plant Biotechnology Bldg. 2505 EJ Chapman Drive. Knoxville, TN 37996 Office: (865) 974-8603 tnturfgrassweeds.org weeddiagnostics.org mobileweedmanual.com @UTturfweeds

Kyley Dickson, Ph.D. Associate Director, Center for Athletic Field Safety Turfgrass Management & Physiology (865) 974-6730 kdickso1@utk.edu @DicksonTurf

Midhula Gireesh, Ph.D. Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

The University of Tennessee UT Soil, Plant and Pest Center 5201 Marchant Drive Nashville, TN 37211 mgireesh@utk.edu (615) 835-4571

Brandon Horvath, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Turfgrass Science

The University of Tennessee 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. 2431 Joe Johnson Drive Knoxville, TN 37996 (865) 974-2975

bhorvath@utk.edu turf.utk.edu @UTturfpath

Becky Bowling, Ph.D. Assistant Professor and Turfgrass Extension Specialist

The University of Tennessee 112 Plant Biotechnology Bldg. 2505 E.J. Chapman Dr. Knoxville, TN 37919 (865) 974-2595 Rgrubbs5@utk.edu @TNTurfWoman

John Sorochan, Ph.D. Professor, Turfgrass Science

The University of Tennessee 2431 Joe Johnson Drive 363 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-7324 sorochan@utk.edu turf.utk.edu @sorochan

John Stier, Ph.D. Associate Dean

The University of Tennessee 2621 Morgan Circle 126 Morgan Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-7493 jstier1@utk.edu turf.utk.edu @Drjohnstier

Nar B. Ranabhat, Ph.D. Assistant Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

University of Tennessee UT Soil, Plant and Pest Center 5201 Marchant Drive, Nashville, TN, 37211 (615) 835-4572 nranabhat@utk.edu @UTplantPathoDoc

Keele

By Grayson Guthrie 1st Assistant Superintendent

The Governors Club (615) 351-0610

gguthrie@thegovernorsclub.net

Ihad the unique and enriching opportunity to attend National Golf Day in Washington, D.C., a professional experience that blended advocacy, community service, and a shared passion for the game of golf. This trip was more than just a chance to speak to elected officials or participate in a community service project on golf courses—it was a chance to see firsthand how deeply interwoven golf is with legislation, economics, public health, and environmental stewardship. Across three eventful days, I was able to represent not only the interests of golf professionals and enthusiasts in my state but also contribute to the positive perception of golf as a force for good in communities across the country.

The trip began with the National Golf Day opening ceremony which set the tone for the entire week and brought together professionals from all corners of the golf industry—course superintendents, PGA professionals, association executives, and business owners alike. One of the highlights of the evening was the keynote speaker, Jake Sherman, one of the founders of Punchbowl News. It was a fascinating and relevant address; Punchbowl News has emerged as a critical player in political journalism and understanding the legislative process. Sherman provided insight into the current political climate, the inner workings of Congress, and how advocacy can make a difference—even in an oftengridlocked environment.

This was followed by a detailed discussion of the key talking points we would be addressing in our meetings with lawmakers. These issues were not only relevant to golf as a sport but also to golf as an industry that supports millions of jobs and contributes $102 billion annually to the national economy. We were briefed on topics ranging from taxation and disaster relief to healthcare and research funding. While I was already familiar with some of the topics, hearing the perspectives of policy experts helped me better understand how to frame our arguments in a way that would resonate with legislators and their staff.

The next day, our schedule was packed with meetings on Capitol Hill. We had meaningful discussions with the legislative assistants of Senator Bill Hagerty, Senator Marsha Blackburn, Representative Mark Green, Representative Scott DesJarlais, Representative Chuck Fleischmann, and Representative Andy Ogles. A major point of discussion during these conversations was the “sin tax” designation that golf courses currently fall under. This classification categorizes golf facilities alongside gambling and alcohol-related businesses, which prevents them from receiving federal disaster relief funds. As recent natural disasters have shown, golf courses are just as vulnerable to hurricanes, floods, and wildfires as any other business or community institution. Yet, due to this outdated classification, they are often excluded from critical support. This puts not only the facilities but also their employees and local economies at risk, given golf’s impact on local tourism, environmental management, and the physical health of its patrons.

Another significant topic was the Farm Bill, particularly the inclusion of the Turfgrass Research Initiative. With turf comprising 60+ million acres and being the 4th largest crop in the United States, this federal investment is vital for the continued sustainability and innovation within turfgrass science.

Golf courses are among the largest managed green spaces in the United States, and they play an important role in water conservation, soil health, and urban cooling. Funding turfgrass research enables golf facilities to improve their practices, reduce water and chemical use, and adopt more environmentally sustainable techniques. In other words, this is not just a golf issue—it’s an environmental one that intersects with agriculture, land use, and climate resilience.

We also addressed the PHIT Act, or the Personal Health Investment Today Act, which proposes allowing individuals to use Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) and Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) toward physical activity expenses, including golf. This proposal is rooted in a growing understanding that preventative health care—exercise, active lifestyles, and community wellness—is essential to reducing longterm healthcare costs. We presented golf not just as a sport or hobby, but as an accessible form of exercise that contributes to physical and mental well-being for people of all ages.

Other topics included workforce development in the golf industry, access to green spaces for underserved communities, and the broader economic impact of golf in our region. Throughout the day, I was struck by how receptive and engaged the legislative staff were. Even if they didn’t have prior experience with golf policy, they asked thoughtful questions and took detailed notes. It reminded me that advocacy works when it’s based on facts, empathy, and a clear connection between public policy and everyday lives.

After a full day of advocacy, the last day of our trip was a welcome shift in pace and focus. We participated in a community service project that took place at two of Washington D.C.’s public golf courses: the Old Soldiers’ Home Golf Course and East Potomac Golf Course. This allowed us to put our mission into practice. While policy discussions are vital, so too is the visible commitment to improving and preserving the spaces where golf happens.

The work was hands-on and satisfying–we mowed greens and fairways, seeded putting surfaces, planted trees, and detailed flower beds with fresh mulch.

Working alongside volunteers from across the country created a strong sense of camaraderie. It was a physical reminder that we’re all in this together—not just talking about change, but making it happen with our own hands. The restoration and beautification efforts we made at these historic courses not only benefit the players who use them but also preserve green space in a major metropolitan area. It’s a demonstration of golf’s potential to provide refuge, especially in urban settings.

Throughout the three days, I gained a deeper appreciation for the complexity and scope of the golf industry. Golf can be seen as a leisure activity or a luxury pursuit, but this trip reinforced just how much more it is. Golf touches issues of public health, environmental sustainability, economic development, youth engagement, and community identity.

Whether we were advocating for fair disaster relief policies or planting trees on public courses, the unifying theme was that golf has the potential to be a force for social good.

A lasting impression from the trip is the power of unity. The National Golf Day coalition represents a variety of roles and organizations, but we spoke with one voice. We weren’t just advocating for our own jobs or facilities—we were advocating for the future of the game, and for its benefits to people and communities across the nation. That sense of shared purpose made the whole experience more powerful and meaningful.

In reflection, this trip was not only a career highlight, but also a reminder of the importance of civic engagement. Too often, people feel disconnected from the political process, or assume that their voices won’t matter.

But by showing up, making our case, and following up, we are shaping the future of golf and influencing the policies that affect our industry. Even the conversations with legislative assistants, which some might overlook, are crucial touchpoints in the legislative process. Those relationships matter. The clarity of our message matters.

Moving forward, I hope to build on this experience by staying active in advocacy efforts—at both the state and national levels. I plan to share what I learned with colleagues and encourage others in the golf industry to get involved. Whether it’s attending town halls, engaging with local representatives, or participating in community clean-up efforts, we all have a role to play.

In conclusion, National Golf Day in Washington, D.C. was far more than a work trip. It was an opportunity to advocate for meaningful policy change, engage in service, and elevate the role golf can play in American life. I am grateful for the opportunity that the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America, the American Golf Industry Coalition, and the Tennessee Turfgrass Association provided, and I am energized to continue this important work.

97 th Tennessee FFA Convention

March 23 – 26, 2025 Gatlinburg, TN

TURF & LANDSCAPE MAINTENANCE PROFICIENCY AWARD

Thank you for your generous investment in the future of agriculture and the next generation of industry leaders. Your support of Agricultural Proficiency Awards empowers FFA members to turn their passion into purpose through hands-on, real world epxeriences.

The 2025 Turfgrass Management Proficiency Award winner is Will Riley from the Hendersonville FFA Chapter. Will began his Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE) by mowing lawns in his neighborhood, but his ambitions quickly grew. He soon joined the team at a local golf course, where he expanded his skills and knowledge of turfgrass management.

Many Varieties Maintained at .500

MONDAY (AM)—SATURDAY TO ACCOMMODATE YOUR JOB NEEDS

• Backed By Two Decades of Rigorous Testing

• Requires 38% Less Water

• Maintains Quality and Color

• High Traffic Tolerance

• Over 2 Billion sq. ft. Installed

In 2023, Will played a key role in a major course renovation project – assisting with the transition from bentgrass to Bermuda. His contributions helped improve both the aesthetics and performance of the course, and he continues to build on that momentum as he explores a future in turfgrass science and management.

Because of your partnership, students like Will are not only gaining valuable experience but also shaping the future of the turfgrass industry in Tennessee and beyond. Thank you for making a lasting difference.

The winner will represent Tennessee at the National FFA Convention, held October 29 – November 1, 2025 in Indianapolis, Indiana.

By J. Scott McElroy, PhD Professor, Auburn University

Herbicide Resistant Sedges. I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but the next big herbicide resistance problem is going to be sedges – and not just one. Probably all of them.

The two major weeds that have caused the greatest problem relative to herbicide resistance to date are annual bluegrass and goosegrass. In 2010 Harold Walker and I were the first to identify sulfonylurea herbicide resistant populations of Poa annua. Before that, resistance to triazines had been identified throughout the southeast, initially in Mississippi by Dr. Eual Coats. Resistance to preemergence herbicides to prodiamine, pendimethalin, and dithiopyr were identified in North Carolina and by me, in Tennessee. Since all of this, there are populations that have evolved resistance to glyphosate (Roundup) and likely to indaziflam (Specticle).

Not to toot my own horn, but my group at Auburn are the principal leaders when it comes to herbicide resistant goosegrass research. We were the first to report oxadiazon (Ronstar), foramsulfuron (Revolver) and sulfentrazone (Dismiss) resistance. Resistance to dinitroaniline preemergence herbicides and metribuzin (Sencor) were previously reported. Because of this resistance and due to the loss of diclofop (Illoxan), there are some turfgrass situations in which there is basically no herbicide available.

Sedges have four main herbicide groups that are effective for control:

• ALS inhibitors,

• sulfentrazone (Dismiss),

• traditional preemergence herbicides indaziflam (Specticle)

• oxadiazon (Ronstar);

and secondary preemergence herbicides dimethenamid (Tower) and S-metolachlor (Pennant Magnum).

ALS inhibitors include sulfonylureas such as trifloxysulfuron (Monument), flazasulfuron (Katana), halosulfuron (Sedgehammer), imazosulfuron (Celero), and others; and also, imazaquin (Sceptre, formerly known as Image.)

I should include MSMA, but its use is so limited that it is not seen as a viable option for all turfgrass situations. Certainly, if you have access and it is labeled for your situation, using it is not a bad idea. Basagran (bentazon) is also available, and although control is limited, it still is an option.

Patrick McCullough, formerly an extension specialist at the University of Georgia, was the first to see the developing problem of herbicide resistant sedges. McCullough identified annual sedge and green kyllinga resistance to ALS inhibiting herbicides. Working with weed scientists who work in row-crops, we have also identified ALS-inhibitor resistant yellow nutsedge, small-flower umbrella sedge, and rice flat sedge in Georgia and Arkansas. (Research papers we have collaborated on are listed at the end).

ALS inhibitors are a key set of herbicides for postemergence sedge control. The only other post herbicide in turfgrass is Dismiss and preemergence herbicides are still available. Here is the problem: First, from a postemergence standpoint, this puts all the pressure on Dismiss. From what we have seen with Poa and goosegrass, when the control selection shifts to only one active ingredient, it is not long until that herbicide is facing resistance as well.

Preemergence herbicides are problematic because many of the sedges are perennial and pre herbicides are not timed properly to coincide with sedge emergence. That is why sedges are typically targeted for post applications rather than pre.

What is the plan moving forward? First, if you are dealing with an annual sedge or kyllinga problem, make sure you are timing those preemergence applications properly. This means some follow-up pre-application in June or July. Virtually every other weed has its window of germination in the spring months, but some sedges –namely cock’s comb kyllinga and annual sedge – germinate later in the June time frame. Second, if you don’t have resistance, it is probably a good idea to start mixing or rotating different modes of action. Since there are basically only two post herbicides, it requires mixing sulfentrazone with ALS inhibitors, or rotating them from year to year. If you have had success with Basagran (bentazon), then consider integrating it as well.

“We have NorthBridge on the diamond at baseball and also NorthBridge on the outfield of baseball…and we did that same at softball. The cultural information in the industry was NorthBridge is the better grass. And so that was my vote to administration.”

—JON DEWITT, ATHLETIC GROUNDS DIRECTOR, UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA

pened in March of 1948, Sewell-Thomas Stadium, “The Joe” as its called has played host to the University of Alabama baseball team for many decades. In 2015 the stadium underwent a complete modernization renovation and following the makeover, switched to NorthBridge Bermudagrass. Athletic Grounds Director Jon Dewitt loves the recuperative ability that NorthBridge displays along with its color and the fact that they don’t need to overseed with its cold hardiness. NorthBridge is also featured as the grass covering the perennially ranked softball team’s field as well.