Copyright © 2024 by the National School Public Relations Association. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without formal permission from the National School Public Relations Association or from the organization audited in this report.

Adobe: Malambo C/peopleimages.com (front); WS Studio 1985/Studio Romantic/Yakobchuk Olena/yoshitaka/Andrey Popov (above, clockwise from “materials”); Blue Planet Studio (back).Loudoun County Public Schools (LCPS) in Virginia has contracted with the National School Public Relations Association (NSPRA) for an in-depth, independent review of the school district’s overall communication program. The NSPRA Communication Audit process helps to identify the strengths, weaknesses and opportunities for improvement in a school communication program through an extensive process that includes:

y A review of print and digital communication materials, tools and tactics;

y Quantitative research through the surveying of district staff (instructional, support, administrative, etc.), parents/ families and community members; and

y Qualitative research through focus groups with these same audiences and through interviews with staff who perform formal communication functions for the district.

Details of this process can be found in the Introduction of this report.

The results of this process are shared in four main sections of the report:

y The Key Findings section provides details about what was learned through the review of materials and the analysis of quantitative and qualitative data.

y A SWOT Analysis distills these findings into the division’s primary internal strengths and weaknesses, and external opportunities and threats related to its communication goals.

y The Benchmarking of Results section reflects how the division’s communication

program compares to other districts on nationally benchmarked SCOPE Survey questions and national standards of excellence in school public relations, as outlined in NSPRA’s Rubrics of Practice and Suggested Measures.

y The Recommendations section details suggested strategies and tactics for addressing identified communication gaps and for enhancing effective strategies already in place.

Following is an overview of this report. As with all school systems, LCPS has areas in which it excels as well as areas where improvements can be made. For a full understanding of what was learned, the rationale behind the resulting recommendations and what will be required to implement those steps, it is recommended that the report be read in its entirety.

y LCPS has a highly qualified communications staff with a wide range of skills and expertise that will enable them to build on the program’s current strengths, even as they are making improvements in areas of challenge.

y Communications staff recognize that communication improvement is an ongoing process and are already implementing changes to how communications and engagement with stakeholders is approached and structured.

y The division’s new superintendent and school board members understand the importance of a strong communication program and they support the Department of Communications and Community Engagement through access to division leaders and information as well as by providing the equipment, tools and

staff resources needed to communicate broadly and effectively.

y The division’s high-quality education program, excellent schools and supportive community offer many opportunities for positive story-telling.

y There has been a perceived lack of transparency in communication in recent years. Internal factors creating this perception include fear of making a mistake when communicating, uncertainty about who is responsible for communicating and concerns about violating privacy.

y Rapid growth of the division, doubling the number of students and opening 36 new schools in the past 20 years, has put strain on the communication infrastructure, which sometimes results in confusion or contradictory messages.

y Perceptions of inadequate engagement and two-way communication has internal audiences feeling overlooked about decisions. Externally, parents and community members feel they are frequently asked for input but don’t hear how their input impacts decisions.

y LCPS’ engagement efforts are decentralized and spread across multiple offices and programs.

y Regional population growth has changed the culture and demographics in Loudoun County, creating divisions between longtime and newer residents that impact the strategies the division must use to effectively communicate with residents.

y Community members who have no affiliation with the division (e.g., children are grown, they do not have children, their children attend private schools) lack adequate information from the division to correct the sometimes inaccurate

information conveyed on social media.

y LCPS receives a greater than usual amount of national media attention, and that requires significant staff time to be allocated to reactively respond to media inquiries.

Based on analysis of the research, the auditors suggest the following strategies for enhancing LCPS’ communication program. For each of these recommendations, a series of practical action steps based on current best practices are included in the report.

1. Expand the LCPS Strategic Communications Roadmap into a comprehensive communication plan.

2. Leverage new leadership to rebuild trust and confidence.

3. Improve communication infrastructure by developing and consistently implementing communication processes and procedures.

4. Combat misinformation and disinformation.

5. Develop a stronger, more proactive media relations plan that contains a social media component.

6. Strengthen the two-way communications culture in LCPS.

7. Implement tactics to engage local residents with no personal connections to the schools.

Implementing these recommendations should be considered a long-term process that involves everyone responsible for communicating in LCPS, not just communications staff. It is generally not feasible to address more than two to three recommendations each year. But while some report recommendations may require major investments of time, this report also offers opportunities to rethink existing practices or to make quick improvements without a significant investment of resources.

When assessing the communication program of an organization, it is important to first have an understanding of the organization itself as well as the environment in which it operates. That background is provided here.

LCPS is the third-largest school division in Virginia, serving more than 82,000 students in 98 schools and employing more than 13,000 staff. The division is located in northern Virginia, and is part of the large metropolitan area that includes all of Washington, D.C., and parts of Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia.

LCPS is governed by the nine-member Loudoun County School Board, which serves as the official policy-making body of the division, operating under the laws adopted by the General Assembly of Virginia. School board members are elected for two- or four-year terms in the November general election with one member elected for each of the eight electoral districts and one member elected at-large. Voters elected nine new school board members in November 2023 to begin serving in January 2024.

The LCPS student body is racially, ethnically and economically diverse. According to the Virginia Department of Education, students identify as 40.4 percent white, 26 percent Asian, 19.5 percent Hispanic, 7.3 percent Black/African American and 5.9 percent two or more races. About a quarter of students are considered economically disadvantaged, and about a fifth are English language learners.

LCPS has experienced rapid growth over the past 30 years. The division had fewer than 16,000 students in 1992. Then in the past 20

years, division enrollment increased from about 40,700 students in 2003 to more than 82,000 students in 2023, and the division opened 36 new schools in the same time period, according to data provided by the LCPS Division of Planning and GIS Services. Enrollment declined modestly by about 100 students from the 202223 school year to the 2023-24 school year.

The division enjoys strong financial support from constituents, with 71 percent voting “yes” on a November 7, 2023 school facilities bond measure that allows the division to issue more than $362 million in general obligation bonds for school facilities.

Superintendent Dr. Aaron Spence began his tenure in September 2023, following a challenging period for LCPS that included the COVID-19 pandemic and national media scrutiny. As this communications audit was being conducted, Dr. Spence was in the midst of a listening tour where he will hold separate sessions for staff and community at each of the 18 high schools in the division over an eight-month period to build relationships with the community and discern where change may be necessary. Dr. Spence previously served as superintendent of Virginia Beach City Public Schools, and school board members from that district lauded his leadership in a Dec. 31, 2023 Washington Post article.

The division has highly regarded schools, as cited by participants in every focus group and interview, with an overall graduation rate of 97 percent and 70 percent of 2023 graduates planning to attend a four-year college.

One of the four goals in the One LCPS: 2027 Strategic Plan for Excellence is to “enhance educational excellence through building meaningful relationships with families and the community.” Its aligned actions are to:

y Deepen family engagement by offering inclusive opportunities for conversation across the division; and

y Strengthen existing and create new business and community partnerships.

The division supports its commitment to communication through various board policies and regulations that address the importance of two-way communication between the school board, participation by the public in school board meetings, media relations, community involvement and guidelines for various methods of communication.

The LCPS Department of Communications and Community Engagement (DCE) is formed by an award-winning team of 14 professionals, who have a diverse set of skills and expertise:

y Chief Communications and Community Engagement Officer Natalie Allen

y Director of Communications and Community Engagement Joan Sahlgren

y Public Information Officer Daniel Adams

y Communications Supervisor Erin Robinson

y Communications Coordinators Christina Arpante, Ed.D., Amiee Freeman and one

open position to be filled

y Graphics and Digital Content Specialist Nicole Eggers

y Internet Content and Video Production Assistant Denver Peschken

y Executive Assistant Kimberly Goodlin

y Videographers Jeff Riegel, Michael Ferrara and Laura Cruz

y Administrative Assistant Maria Polink

Their department has earned the division numerous state and national communication awards over the years, including NSPRA Golden Achievement Awards in 2023, 2022 and 2018 as well as multiple NSPRA Publications and Digital Media Excellence Awards. Their work has also earned multiple Telly Awards for excellence in video and two Emmy Awards from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences: National Capital Chesapeake Bay Chapter for short form video content and video essay.

Like the division itself, the department has evolved over the last 10 years as the division’s enrollment and communication needs grew. From an office of seven in 2014, it expanded by seven positions between 2020 and 2024 to better match staff capacity with increasing responsibilities and stakeholder demand for two-way communications from the division.

Recently named its own department, today DCE oversees a wide range of functions such as:

y Managing LCPS’ mass notification system

y Coordinating emergency communications

y Overseeing the development of a new website planned for launch in fall of 2024

y Producing content for the LCPS website, news releases and newsletters

y Fielding media requests

y Producing videos for LCPS-TV

y Serving as communication liaisons with the division’s various departments

y Overseeing division branding

y Writing speeches and providing briefing documents for the superintendent and school board members

y Responding to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests (405 received during the 2022-23 school year)

It should be noted that this department is separate from the division’s Family and Community Engagement Office, which exclusively serves English language learners and their families and operates within the Department of Teaching and Learning.

NSPRA’s mission is to develop professionals to communicate strategically, build trust and foster positive relationships in support of their school communities. As the leader in school communication™ since 1935, NSPRA provides school communication training, services and national awards programs to school districts, departments of education, regional service agencies and state and national associations throughout the United States and Canada. Among those services is the NSPRA Communication Audit, which provides:

y An important foundation for developing and implementing an effective strategic communication plan.

y A benchmark for continuing to measure progress in the future.

The development of any effective communication program begins with research. Therefore, the first step of the process is to seek data, opinion and perceptions. The process for this research is detailed in the following section, and the results of this research can be found in the Key Findings section.

Based on the research findings, the auditors identify common themes and make general observations about the strengths and weaknesses of the communication program. The auditors then use this information to develop Recommendations designed to help the division address communication challenges and enhance areas of strength. Each of these customized recommendations are accompanied by practical, realistic action steps grounded in today’s public relations and communications best practices, as reflected within NSPRA’s 2023 edition of the Rubrics of Practice and Suggested Measures benchmarking publication.

It is important to note that the primary goal of any communication program is to help the division move forward on its stated mission. Accordingly, the auditors developed each recommendation in light of the division’s vision: “Every student will reach their full potential and achieve their dreams;” its mission: “Empowering all students to make meaningful contributions to the world” and the One LCPS: 2027 Strategic Plan for Excellence.

The result is a report that will provide LCPS with a launching point for enhancing communication efforts for years to come.

The NSPRA Communication Audit process incorporates three methods of research to capture both qualitative and quantitative data.

Materials Review.

One of the first steps in the communication audit process involved the Department of Communications and Community Engagement submitting samples of materials used to communicate with various internal and external audiences (e.g., the One LCPS Strategic Plan for Excellence 2027, the LCPS Strategic Communications Roadmap 2023-24, board policies related to communication and a wide range of sample materials and publications

produced by the department). The auditors conducted a rigorous review of these materials as well as of the division and school websites and social media.

These digital and print materials were all examined for effectiveness of message delivery, readability, visual appeal and ease of use. The auditors’ review of websites and social media platforms also focused on stakeholders’ use of and engagement with online content.

For LCPS, NSPRA conducted its proprietary School Communications Performance Evaluation (SCOPE) Survey to collect feedback from two stakeholder groups: parents and families, and employees (instructional, support and administrative staff). The nationally benchmarked SCOPE Survey was conducted from November 28 - December 15, 2023. It included questions regarding the following:

y How people are currently getting information about the division and its schools, and how they prefer to get it.

y How informed they are in key information areas such as leader decisions, district plans and district finances.

y Perceptions about what opportunities exist to seek information, provide input and become involved.

y To what degree stakeholders perceive communications to be understandable, timely, accurate, transparent and trustworthy.

There was also an opportunity for participants to comment on any aspect of school or school/ department communications.

Responses to the SCOPE Survey resulted in attaining the following confidence interval for each audience, based on the total audience populations reported by the division and using the industry standard equation for reliability.

y Parent Survey:

2,732 surveys completed

±1.8 percent confidence interval (± 5 percent target exceeded)

y Faculty/Staff Survey:

1,384 surveys completed

± 2.5 percent confidence interval (± 5 percent target exceeded)

This same survey has been administered to more than 100 school districts across the United States, and the Benchmarking of Results section includes the SCOPE Scorecard, which compares LCPS’ SCOPE Survey results with the results of other districts who have conducted the survey.

The core of the communication audit process is the focus groups component designed to listen to and gather perceptions from the division’s internal and external stakeholders. The auditors met in person or virtually with 20 focus groups and conducted interviews with the superintendent, the chief communications officer, the director of communications and community engagement, the chief academic officer and school board members from December 4 - 20, 2023.

For the focus groups, division officials identified and invited as participants those who could represent a broad range of opinions and ideas. Each group met for an hour and was guided through a similar set of discussion questions on a variety of communication issues. Participants were assured their comments would be anonymous and not attributed to individuals if used in the report.

The stakeholder groups represented in the focus group sessions and interviews included the following:

y Parents (three groups, including a nonEnglish-speaking group)

y High school students (two groups)

y Community leaders and partners

y Teachers (middle and high schools)

y Teachers (elementary schools)

y Support staff (custodians, aides, nutrition, maintenance)

y Paraprofessionals

y Transportation staff

y Professional staff (two groups of psychologists, counselors, curriculum specialist, nurses, etc.)

y Administrative assistants

y Directors/supervisors

y Principals (middle and high schools)

y Principals (elementary schools)

y Family and Community Engagement Office staff (exclusively serve English language learners and their families)

y Department of Communications and Community Engagement staff

y Superintendent

y LCPS School Board members

The NSPRA team who delivered these communication audit services included the following:

y Naomi Hunter, APR, Lead Auditor / NSPRA Communication Surveys Manager

y Steve Mulvenon, Ph.D., Consultant Auditor

y Sarah Loughlin, On-site Audit Assistant / NSPRA Communication Manager

y Alyssa Teribury, On-site Audit Assistant / NSPRA Communication Research Specialist

y Susan Downing, APR, NSPRA Communication Audit Coordinator

y Mellissa Braham, APR, NSPRA Associate Director

The team’s vitae are included in the Appendix

This report demonstrates the willingness of the LCPS School Board, superintendent and chief communications officer to identify and address communication challenges, and to continue to strengthen the relationship between the division and its internal and external stakeholders. When reviewing the report, it is important to keep the following in mind:

y The report is intended to build on the many positive activities and accomplishments of the division and its Department of Communications and Community Engagement by suggesting options and considerations for strengthening the overall communication program. The recommendations included here are those the auditors believe are best suited to continuing to elevate LCPS’ communication program.

y NSPRA’s communication audit process involves a holistic assessment of a district’s overall communication program, meaning it goes beyond any one department or individual to assess communication efforts throughout the division and its schools.

y Whenever opinions are solicited about an institution and its work, there is a tendency to dwell on perceived problem areas. This is natural and, indeed, is one of the objectives of an audit. Improvement is impossible unless there is information on what may need to be changed. It is therefore assumed that LCPS would not have entered into this audit unless

it was comfortable with viewing the school district and its work through the perceptions of others.

y Perceptions are just that. Whether or not stakeholders’ perceptions are accurate, they reflect beliefs held by focus group participants and provide strong indicators of the communication gaps that may exist.

y This report is a snapshot of the division at the time of the auditors’ analysis, and some situations may change or be addressed by the time the report is issued.

The recommendations in this report address immediate communication needs as well as those that are ongoing or that should receive future consideration as part of longrange planning. Implementation of the recommendations should be approached strategically, using this report as a road map and taking the following into consideration:

y It is generally not feasible to implement more than two to three major recommendations each year while maintaining all current communication programs and services.

y The recommendations are listed in a suggested order of priority, but school leaders may choose to implement the recommendations at different times.

y Recommendations may go beyond the purview of the Department of Communications and Community Engagement. NSPRA views communication as a function that occurs across every level of a division. While some recommendations may apply only to formal communications staff, others may apply to additional departments or staff.

y Look for opportunities for immediate improvement and to rethink existing practices. Action steps that can be taken immediately with minimal effort from the school or the Department of Communications and Community Engagement and still pay quick dividends are noted as “quick wins’’ with the symbol shown above. There also are action steps that may offer opportunities to “rethink” a task or process that could be eliminated or reassigned based on stakeholders’ feedback and the auditors’ analysis. These are noted with the symbol shown to the left.

y Some recommendations may require additional staff capacity or financial resources to undertake while maintaining existing communication activities.

Participants were generous in sharing their thoughts and ideas during the focus group sessions. They were also interested in finding out the results of the communication audit. Because of their high level of interest and the importance of closing the communication loop to build trust and credibility, NSPRA recommends that LCPS share with focus group participants the outcome of the audit process and its plans for moving forward.

Be sure to also share this information with key stakeholders such as employees and parents/families. This kind of transparency will demonstrate that division leaders prioritize twoway communication with stakeholders.

NSPRA’s staff auditing team can provide suggestions and examples for how this report could be effectively shared with various constituencies as well as the public.

The following key findings reflect common themes that emerged from the SCOPE Survey, focus group discussions, interviews with division leaders and review of district materials. In reviewing the charts that follow on SCOPE Survey results, keep in mind that LCPS exceeded confidence interval targets for both parent/family and employee responses; there is a high level of confidence in the results.

This section of the report begins with key findings on stakeholder perceptions of the division’s image because communication from a district influences how it is perceived by stakeholders. Conversely, the image or reputation of a district influences the nature of communications necessary for a district to achieve its goals.

y On the SCOPE Survey, when participants were asked to rate their overall perception of the division, 60 percent of parents and employees rated the division as excellent or above average. Some of the most common words survey participants identified as coming to mind when they think of the division are good, diverse, quality and inclusive, as illustrated on page 33.

Overall Perception of the Division

y When converted to a 5-point scale for comparison with national averages, ratings for perceptions of the division by LCPS parents and employees are close to the average SCOPE Survey results of more than 100 school systems nationwide and above average for systems with more than 50,000 students.

y When asked about the image and brand of LCPS, participants in all focus groups praised the division for its high academic standards, dedicated and caring staff, and its success in preparing students for college and career. A staff member commented, “Our community is diverse, supportive and caring, with individuals who value education.”

y Focus group participants in multiple groups noted that the division is located in one of the wealthiest counties in the United States, which brings significant resources to the district, resulting in top-notch programming, a wide range of curricular choices and modern, wellmaintained buildings.

y The division has grown rapidly over the past 20 years, bringing change that has affected its brand and image, according to focus group participants in nearly all groups. A department leader noted, “I think a lot of times we communicate with people who don’t know us, but we communicate with them as if they do.” Another district employee voiced a concern that the division isn’t educating newcomers about the high quality of LCPS schools: “A neighbor sent her kids to private school because she moved here from an area where public schools weren’t valued.”

y Several division leaders expressed a belief that LCPS is not effectively engaging families and the wider community, and that an effort to do so is critical to building trust. Example comments included a perceived “need to focus on community and family perceptions of communication and how we can attain authentic two-way communication,” and a belief that, “We don’t have a good ground game with key communicators and tendrils into the community that promote two-way dialogue.”

y Participants in every focus group voiced concern about the discrepancy between their firsthand, positive experiences within the division’s schools and the perception held by outsiders whose views are shaped predominantly by national and local news coverage. Comments such as these were typical:

“I hear from family [members] around the country that we’re constantly in the news. It’s disheartening.”

“The media’s portrayal of us doesn’t align with our reality.”

“The negative people get the microphone.”

y In every focus group, auditors heard a longing for the wider community to hear stories about the many positive things happening across the division. As examples, focus group participants shared stories of student successes and achievements as well as anecdotes about the dedication of staff in supporting students.

y Parents, employees and community members in nearly all focus groups expressed optimism about the opportunity for a new superintendent, new division leaders and new school board members to bring about positive change and improve morale among staff and parents after several years of challenges that included the COVID-19 pandemic and high-profile, national media attention. Just a few of many such comments auditors heard include:

“There’s now a great opportunity to build that community engagement back up. The new superintendent is community-minded.”

“The new board of education is an opportunity for a reset.”

”The new superintendent seems to be on board with providing the county hope, equity and listening.”

“Leadership has changed and the fort is starting to be taken down. They are inviting businesses to the table to provide input. It’s a slow needle they are trying to move.”

y LCPS parents and employees have a rich array of sources from which they can learn news and information about the division: email; newsletters from the division, school sites and departments; district and school websites; the Blackboard Connect mass communication system for phone, email and texts; various mobile apps for classrooms; social media; and news media.

y The SCOPE Survey sought participants’ insights on the frequency with which they rely on various sources for information about LCPS. The results on the following two pages show that on a daily or weekly basis, the top three sources of information for parents and employees are email, the division newsletter and what other people tell them, though employees rely more heavily on what other people tell them, and parents rely more on newsletters.

The LCPS results on pages 15-16 are similar to national averages on the SCOPE Survey, where email is the top source used daily/weekly to get information about a school system by both employees (93%) and parents (85%). Also high on the national averages are newsletters (57% for employees, 61% for parents) and what others tell me (64% for employees, 43% for parents).

y When survey participants who use email as a frequent source of information about the division were asked which types of email they reference, both groups showed a strong reliance on a number of sources but rely most heavily on information emails from the division.

Types of Emails Referenced for Division Information

What others tell me

Newsletters

Website

Social Media

Local news and media

Calendar

Meetings

Text messages

Mobile app

Phone calls

Printed Information

School board

Frequency of Reliance on Communication Sources for Information About the Division - Employees

Newsletters

Loudoun County Public Schools

Frequency of Reliance on Communication Sources for Information About the Division - Parents

What others tell me

Website

Calendar

Text messages

Social media

Local news and media

Mobile app

Phone calls

Printed information

School board

Meetings

y Survey participants who use newsletters as a frequent source of information about the division were asked which types of newsletters they reference. Results indicate that parents rely most heavily on principal or school newsletters, which are read by 79 percent of parents, and staff rely most heavily on the One LCPS Newsletter, which is read by 84 percent of staff.

y Survey participants who frequently rely on what other people tell them for information about the division were asked whom their sources of information are. As shown to the right, employees rely most heavily on colleagues for information and parents rely most heavily on their student, followed by teachers and principals.

y While local news and media are less frequently used sources of information for LCPS parents and employees than email, newsletters and what other people tell them, it is a more frequently used source than in many division/districts NSPRA audits. The following chart compares the reliance of LCPS stakeholders on local news and media in comparison with several other recently-audited school systems in major metropolitan/suburban areas.

y NSPRA used Meltwater, a media monitoring service, in its analysis of local and national news coverage of LCPS during the 2022-23 school year, which began for students on Aug. 25, 2022, and ended on June 8, 2023. The analysis finds that news coverage of LCPS is largely neutral.

During the school year, there were 3,735 English language news articles published about LCPS in the United States, an average of 12 mentions per day. Unusually large spikes in national news coverage occurred on Oct. 17 (200 mentions), Nov. 4 (225 mentions), Dec. 5 (173 mentions), Dec. 12 (400 mentions) and Dec. 13 (353 mentions). News topics coinciding with those spikes included a group’s recommendation for a school name change in LCPS, the election of local board members, teacher-related court rulings and appeals, the release of a grand jury report on an investigation in LCPS, and the indictment of the former LCPS superintendent.

Meltwater’s analysis of the “sentiment” of the national news coverage of LCPS in 2022-23 shows 57.3 percent were neutral, 31.5 percent were negative and 11.2 percent were positive.

Less than a third of the national news coverage (30.7 percent) was from media sources in Virginia (19.5 percent), Washington, D.C. (8.1 percent), Maryland (2.3 percent) and West Virginia (0.8 percent). The majority was from other states.

Sentiment of National News Coverage Aug. 25, 2022 - June 8, 2023

Sentiment of Virginia News Coverage Aug. 25, 2022 - June 8, 2023

Analysis of coverage only in Virginia finds 607 mentions during the 2022-23 school year, for an average of two mentions per day. Spikes in news media coverage were similarly seen in Virginia on Nov. 4, Dec. 5 and Dec. 12. During the spike period, the sentiment of coverage was 49.5 percent neutral, 41.7 percent negative and 8.9 percent positive. Otherwise, at

least two-thirds of the coverage for the rest of the school year had a neutral sentiment (Aug. 24 – Oct. 17, 2022: 78 percent neutral, 14.4 percent negative, 7.6 percent positive; Dec. 14, 2022 – June 8, 2023: 75.8 percent neutral, 18.9 percent negative, 5.4 percent positive).

y LCPS is regularly covered by two local weekly newspapers, The Loudoun Times-Mirror and Loudoun Now. Both have a strong online presence and weekly print editions. Additionally, The Washington Post occasionally carries stories on major division events. The four major television networks (NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox), independent station DCNewsNow, and online media such as InsideNOVA.com and Patch also cover division events. During the 2022-23 school year, reporters with Loudoun Now, the Associated Press and WJLA-TV (an ABC station) generated the most articles about LCPS and significantly more than other media outlets’ reporters.

y LCPS’ national media attention is perceived by some parent and employee stakeholders as affecting the content and frequency of division communications.

Participants in several focus group sessions expressed a belief that the extensive coverage, which rank-and-file employees perceive as unfairly negative, has produced an atmosphere of caution when communicating because of concern that any misstep, however minor, might put the division back in the spotlight.

In another focus group, auditors heard a different perspective. Members in this group said that after being criticized for a lack of transparency, the division is now overly eager to issue media releases on even minor issues.

y Parents and employees rely on different communication sources depending on the type of information they are seeking, as shown in the charts on pages 19-20.

Both parents and employees prefer email as their source of information for all but emergency communications, for which they prefer text messages.

For communication on student’s progress and how to best support their learning, email and the parent portal (ParentVUE) are rated the most highly.

When staff were asked to identify their preferred methods for receiving information to help them perform their duties and support student learning, email also received the highest rating.

y Social media ranked fifth for employees and seventh for parents as a source of information about the division, but in nearly every focus group, participants shared a perception that social media plays an especially significant role in providing information and shaping public opinion

Parents’ Preferred Methods for Communication About Student Progress

Parents’ Preferred Sources for Various Types of Information

Employees’ Preferred Sources for Various Types of Information

Employees’ Preferred Sources for Information About How to Perform Their Duties

in LCPS. Focus group participants perceive that social media posts about negative attentiongrabbing incidents quickly overshadow positive news and general information. A division director commented, “These negative occurrences happen everywhere, but our county’s proximity to D.C. creates a unique situation,” sharing a belief that Loudoun County is too often a “poster child” for a range of controversial issues that play out on social media.

y Parents have higher levels of satisfaction with LCPS communication than employees. When SCOPE Survey participants were asked to give an overall rating for their satisfaction with communication from the division, 58 percent of parents and 47 percent of employees rated LCPS as excellent or above average.

y When these responses are converted to a five-point scale to compare with the SCOPE Survey results of more than 100 school systems nationwide, LCPS’ ratings for overall satisfaction with communication are slightly below the national average but comparable to an average of districts with 50,000 or more students enrolled, as shown in the following chart.

5=Excellent 4=Above Average 3=Average 2=Below Average 1=Very Poor *Districts with enrollment of 50,000 - 187,000

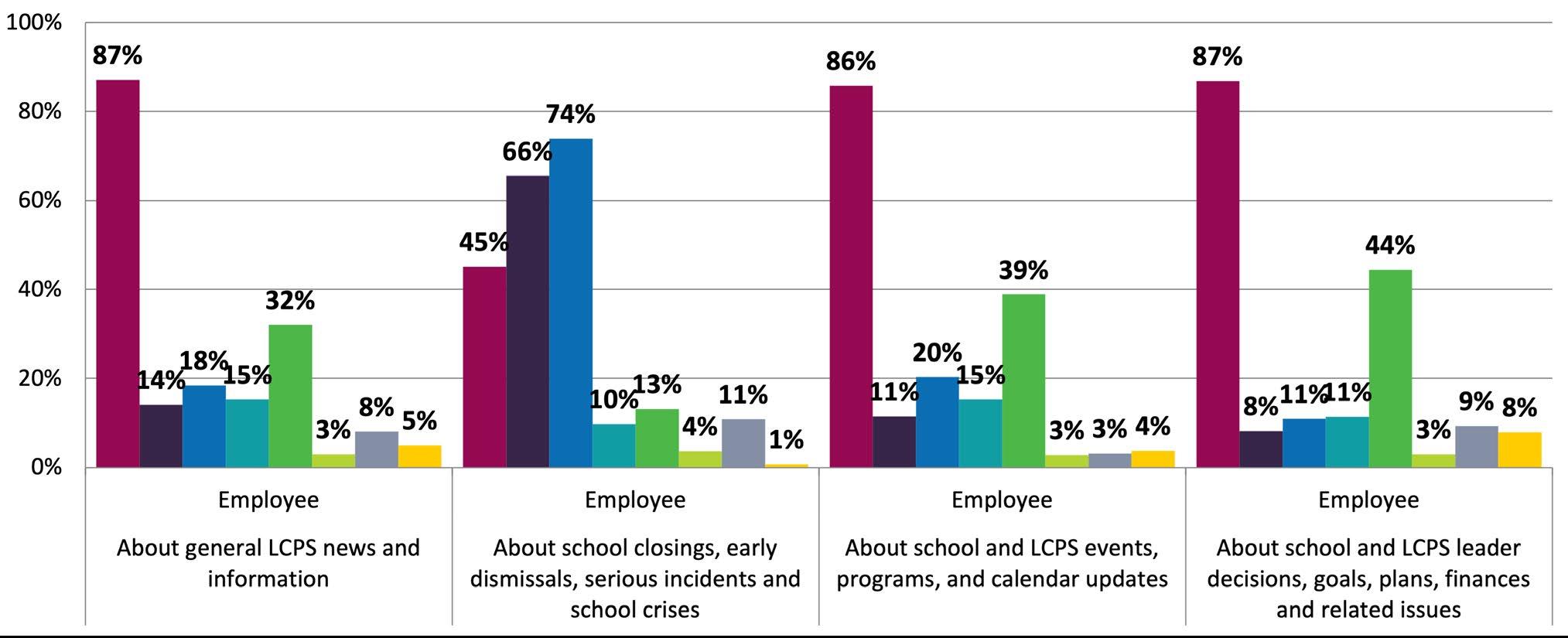

y When parents and staff were asked to rate how informed they are on eight different topics, both groups gave the highest marks to information about school safety (including school closings, serious incidents and school crises), with 54 percent of parents and 52 percent of staff saying they felt extremely or very informed, as shown on pages 22-23.

Employees were more informed about division successes and achievements, with 87 percent indicating they are at least moderately informed in this area.

Parents feel more informed about student successes and achievements, with 78 percent indicating they are at least moderately informed in this area.

How Informed in Key Areas - Parents

How Informed in Areas Specific to Parents

How Informed in Key Areas - Employees

How Informed in Key Areas - Parents

How Informed in Areas Specific to Parents

How Informed in Key Areas - Employees

y When parents were asked to rate how informed they feel on topics pertaining to their role as a parent, the highest ratings were for “about PTA/PTO Activities” and “about my child’s progress in school,” as shown on the previous page.

y When staff were asked to rate how informed they feel on topics pertaining to their role as an employee, the highest ratings were for “about how to best perform my duties” and “about how I can support student achievement.”

y Parents and employees were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements related to the quality of communication in key areas on the SCOPE Survey, as shown on pages 26-27.

Both groups had high levels of agreement with statements that “communications are easy for me to understand,” “I know where and how I can direct a question, complaint or concern,” and “information is accurate.”

They had lower levels of agreement in areas related to the division’s relationships with stakeholders, such as, “I trust the communication I receive,” “my involvement is welcome and valued,” “communications are open and transparent,” and “my input and opinion are welcome and valued,” which ranked sixth to ninth out of nine areas for both groups.

For the trustworthiness of information from the division, LCPS scored lower than the national average but in line with other similarly large school systems.

y The LCPS Department of Communications and Community Engagement (DCE) was lauded by many employee focus group participants for its professionalism, expertise and commitment to service. A department director said, “[The communications team] is phenomenal. They always come through for me.”

y Numerous employee focus group participants, especially those in senior management positions, commented on the challenges of communicating effectively in an environment of heightened scrutiny due to the national profile of LCPS. Auditors heard empathy and appreciation from employees and parents alike for the difficult jobs being done by members of the communications team.

y Parents and employees in focus groups balanced criticisms of division communication with a general acknowledgment that the division is in a leadership transition and efforts to improve communication are already underway. Even those who were critical of past communications often commented that they are seeing signs of improvement.

y Feedback from parents and employees reflect a perception that there are too many channels for receiving information. Participants in all focus groups and on the SCOPE Survey commented that the sheer volume of communication coming from multiple people and a variety of sources is overwhelming. Parents and employees both reported that it is challenging to process, absorb and act on all the information they receive.

A principal shared, “The more information tools we add on, the more options there are for communicating.” There was agreement in the group that an excess of channels used contributes to confusion and information fatigue.

A parent comment on the SCOPE Survey was typical and echoed by many in the focus groups: “There are too many ways of receiving communication from school teachers and principals. Remind, texts, emails, the LCPS app, ParentVUE, etc. It is too confusing. Keep it simple.”

y Stakeholders in both internal and external focus groups also shared that there appear to be no standard practices for the format used to share information, how often it is disseminated and who is responsible for providing it.

A focus group participant shared, “Parents prefer the longer post with one update versus dribs and drabs of information trickled out across the week.”

Principals shared that there have been recent attempts to standardize, with most principals now sending a weekly school newsletter using a platform called S’more that is visually simple and easy to scroll.

y Comments by parents in the SCOPE Survey expressed a desire for more concise and straightforward communication that is focused on essential academic and safety issues. Comments such as these were typical:

“The communication is too wordy with a lot of information that is very overwhelming to understand. The important information is lost among other non-important/marketing information and it’s very easy to miss key information.”

“Communication should be focused on relevant and immediate concerns, such as details about curriculum, lunch menus and testing schedules.”

Perceptions Related to the Quality of CommunicationsParents

Loudoun County Public Schools

Perceptions Related to the Quality of CommunicationsEmployees

Perceptions Related to the Quality of CommunicationsParents

Perceptions Related to the Quality of CommunicationsEmployees

“The division and schools should reduce the amount of non-essential information.”

“Schools and the division should deliver clear, direct messages.”

y Although parents and employees were aware of the fine line between sharing information and violating the privacy rights of students and staff, a common theme in both focus groups and SCOPE Survey comments was the need for greater transparency and accountability in communications, particularly regarding incidents affecting student safety and well-being.

Some expressed the idea that there is a disparity between how the division and parents define transparency. A parent put it this way: “The whole division is doing a better job of providing information, but it’s not coming across as transparency to regular parents like me.”

Many comments centered around frustration about the vagueness of messaging. Following are representative statements from focus group and SCOPE Survey participants:

▫ “There’s a serious lack of transparency, with vague communications that raise more questions, particularly during threats of incidents.”

▫ “Language like ‘does not reflect school values’ or ‘an incident occurred’ can mean anything from a child saying a racial slur to a child assaulting someone physically, to a child making a gun threat.”

▫ ”Don’t be afraid to tell parents the truth, don’t sugarcoat things.”

▫ “Communications seem to be protecting against litigation rather than prioritizing students.”

Some parents and employees expressed the perception that the division’s or school’s fear of causing offense is the reason for what they described as bland, vague communications.

Others pointed to what they see as inconsistency in messaging around serious incidents. “On the one hand, it seems as though these mass emails make mountains out of molehills, and on the other hand, they sweep very troubling information under the rug.”

Parents shared that the messages on sensitive subjects should always be accompanied by guidance on where to address questions.

y Employees, especially those at the director, managerial and site administration level, attributed many of the communication challenges faced by the division to structural weakness in how communication flows internally and externally.

Employees from various departments in the central office, as well school-based administrators and division partners such as law enforcement public information officers, pointed to a lack of systems and standard operating procedures for communications as making it more complicated to frame messages positively and to release news efficiently.

Employees expressed frustration about the volume of communications they receive from multiple departments on a wide variety of topics. Following are some illustrative comments:

▫ “I feel inundated with the amount of communication I receive. It’s challenging to keep up and there are instances of duplicate messages.”

▫ “I frequently find myself with five or six newsletters in my inbox from different departments, each with its own agenda and numerous links. Reviewing these can be a full-time job.”

Several school-level administrators said they feel they are “at the end of an information fire hose” with confusing and sometimes contradictory messages from the central office. They attribute this to departments not working together and operating in silos.

y Parents and employees at all levels expressed frustration that they do not have input into division decision-making.

Focus group participants explained that input is often gathered, but it is not shared back. Many employees and parents shared a desire for more feedback loops that make a connection between the input they provide and the decision that is made.

Auditors also heard that stakeholders are weary of completing surveys. Parents and employees want to provide information, but in ways besides surveys.

Central office directors/supervisors say they often feel overlooked in the decision-making process and when major news/changes/policy decisions are announced.

y Without exception, participants in every focus group expressed a longing for “good news” stories. Their desire for an increase in positive stories went beyond district communication tools to include school-level tools and the public news media. Illustrative comments include:

“There needs to be more outreach to build a positive relationship with reporters so they’ll tell the good news and wonderful stories. They’re always looking for great stories to tell, and they aren’t mind readers, so we need to bring the story to them.”

A parent said, “All the good stuff that’s happening with students is being distributed districtwide, but the division office needs to train the folks who do the newsletters at each school to do that at a local-level to effectively communicate both the good news and the challenging news.”

Division/School Websites

y A complete redesign of the LCPS websites began in December 2023, with plans to launch the new website in time for the 2024-25 school year. Because of that, the auditors did not undertake an extensive analysis of the current division’s or schools’ websites. As part of that transformation, responsibility for the website will move to DCE, which aligns well with the primary role of a website as a tool for online communications, marketing and engagement.

y As development of the new websites progresses, the auditors offer a few considerations based on the focus groups feedback and SCOPE Survey comments:

The auditors heard in both employee and parent focus groups that the current division website is hard to use, difficult to navigate, requires too much scrolling and has an ineffective search function.

The auditors also heard from employees in several focus groups that the current intranet is minimally useful. One teacher said she had not used it in years. Another said he finds it easier to call someone in HR to get what he needs.

There are wide differences in the quality of individual school websites, and the need to standardize the user experience across the division was a frequent comment.

▫ As one assistant principal said, “It would be nice if there were expectations of what schools should place on their website. What the pages should look like. Fonts, formatting, length of content, bullets vs. sentences, etc.”

▫ Another assistant principal put it this way. “It’s a general rule that whoever maintains a school calendar also updates the website; I would also love for this responsibility to belong to a communications professional or, at the very least, provide some more guidance/expectations about what needs to go on the website.”

y LCPS has a broad social media presence, with official, verified division accounts on Facebook, X/Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn as well as on the video hosting site Vimeo. The Department of Communications and Community Engagement (DCE) uses Facebook, X and Instagram as the “foundation of its social media strategy” and uses LinkedIn for Human Resources and Talent Development (HRTD) announcements as well as for thought leadership opportunities. At the time of the writing of this report:

The division’s Facebook account has about 48,000 followers. There are about one to four posts per weekday, and posts are generally about division events, programs for students and families, student and staff accomplishments, school board meetings, community partnerships, holiday and weather-related announcements, and acknowledgments of employee awards and recognition weeks. Links to division webpages with more information are frequently included.

The division’s X/Twitter account has about 216,000 followers. There are about one to three posts per weekday, and posts are generally about programs for students and families, student and staff accomplishments, school board meetings, community partnerships, holiday and weather-related announcements, and school-level news retweets. All posts are accompanied by images, with some featuring photos and others featuring graphics and text. Links to division webpages with more information are frequently included. There is occasional use of hashtags and regular tagging of related school and community organization accounts.

The division’s Instagram account has more than 7,000 followers; DCE reports that the amount of followers has increased by 49 percent from the previous year. There are about one to three posts/reels per school week, and posts are generally about programs for students, student accomplishments, staff recognition days, and holiday and weatherrelated announcements. All posts include images, as Instagram requires, with some featuring photos and others featuring graphics and text. Photo captions tend to be lengthy, and hashtag use is limited except for an athletic sportsmanship series featuring #WeAreOneLCPS #WeAreOneCompetingTogether.

The division’s LinkedIn account has more than 10,000 followers and at least 6,300 linked employees; DCE reports that the amount of followers has increased by 20 percent from the previous year. There are about one to three posts per school week, and posts are generally about job fairs, employment opportunities, messages of thanks to community partner organizations, acknowledgments of employee awards and recognition weeks, and spotlights on training programs. There is occasional use of hashtags, particularly for #ThankAPartner posts, and regular tagging of related community organization pages.

As spotlighted in DCE’s annual communications report, some notable division social media campaigns in 2022-23 included a special education series with videos on assistive technology, Unified Sports and United Sound; the award-winning Black History is My Story series; promotions of a Mental Health and Wellness Conference that saw a 41 percent increase in attendance; a Teacher Cadet series; the “We are LOUDoun” recruitment series; and the Thankful Thursday school-business partnership series of posts.

y Numerous schools, clubs and division departments have their own social media pages. Most high schools have 2-3 social media accounts, typically on Facebook, X/Twitter and/or Instagram. While many middle schools have accounts on Facebook and X/Twitter, some have not been updated in two to three years.

y Auditors reflected on LCPS social media in part based on DCE’s half-yearly and year-end communications reports, which include internal data about their social media platforms and campaigns, and in part based on industry formulas for determining engagement rates through publicly available post data (e.g., reactions/likes, comments, shares).

DCE reports that in 2022 it began using paid social media advertising, in addition to its organic posts, on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn to target specific county populations with relevant events, messaging and program opportunities, and to boost recruitment for open staff positions. Its 2022-23 communications report shared results of several paid ad campaigns, including one for dual language immersion on Facebook and Instagram that had a reach of 6,732 in English and 5,570 in Spanish, a “We are One LCPS” college grads series on LinkedIn with 88 web clicks, and an HRTD recruitment ad on Facebook and Instagram with 442 web clicks.

Public data during a school week of posts from December 11-15, 2023, suggests that average engagement for posts on LCPS’ Facebook and Instagram pages are at or above the 2022 average engagement rate across all industries.

y The division has Social Media Guidelines posted in the Communications and Community Engagement section of the division website. Each of LCPS’ social media channels also include a link to the social media guidelines (under “privacy and legal info” on Facebook, in the page

bios on X and Instagram). LCPS also has a division-level Social Media Communications Protocol with a content rubric on what and what not to post, community moderation guidelines and instructions for dealing with unanticipated issues.

y In DCE’s regular communications reports to the LCPS School Board, it includes updates on the department’s major social media campaigns and its post/ad analytics such as engagement, reach and click-through rates. A draft of the Division Strategic Communication Roadmap for 2023-2024 did not contain objectives related to the division’s various social media channels, but social media use is often part of the

Social Media Platforms Used for School- or Division-related Information strategies and tactics for achieving a communication objective.

y The SCOPE Survey found that 76 percent of parents and 78 percent of employees use Facebook and 28 percent of parents and 20 percent of employees use Instagram either daily or weekly to get school or division information, as shown in the chart above.

y During a focus group of community partners, a perception was shared that the division uses social media to publicize awards and achievements but doesn’t use it for difficult messages or negative news.

y DCE has an in-house production team, and that unit is branded as LCPS-TV.

y The team earned two NSPRA Golden Achievement Awards in 2022, for its “School is...” video series and its “Mental Health Awareness” alumni video series. Their work also earned multiple Telly Awards for excellence in video and two Emmy Awards from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences: National Capital Chesapeake Bay Chapter for short form video content and video essay.

y LCPS-TV provides programming on a Vimeo page, on Comcast channel 18 and Verizon FIOS channel 43, and on the division’s website. The videos are also often featured on other division social media channels.

y The division website footer includes, among its social media links, a link to the division’s Vimeo account, which has 580 followers and more than 1,100 videos posted. DCE reports

that the Vimeo page is primarily used to house videos and is not intended as a place to drive audiences. Instead, audience engagement with LCPS videos primarily happens when the videos are posted on the division’s other social media platforms. The Vimeo page doesn’t offer playlists or another easily searchable organizational structure, and there is no public indication of how many times videos are viewed, liked or shared.

y Videos fall into a variety of categories and topics such as superintendent messages, spotlights on educational programs and student services, spotlights on school facilities and renovations, staff recognition weeks/months, “making an impact” community member interviews, staff training modules, and student and alumni interviews.

y LCPS streams school board meetings live and archives them. The recordings are housed in the Meeting Agendas & Documents (aka, BoardDocs) section of the website. Finding the recordings can be confusing, as it requires seven clicks from the website’s home page to reach them.

As part of this communication audit, NSPRA conducted the online School Communication Performance Evaluation (SCOPE) Survey to collect feedback from three stakeholder groups: parents and families, employees (instructional, support and administrative staff) and community members. This data was used by the auditors to identify strengths and weaknesses of LCPS’ communication program, and many of these key data points are included in the Key Findings section of this report.

An additional value the SCOPE Survey brings to our clients is the ability to compare their SCOPE Survey results on issues that matter most in school communication with the results of the more than 100 surveys conducted by districts and educational service agencies, large and small, across the United States since 2015. This data is presented in the SCOPE Scorecard on the following page.

The rating numbers provided for each question, on a 1-5 scale, correlate to the following descriptions as applicable for the type of question to which participants were responding:

1. When participants were asked to rate how informed they feel on specific topics, they responded using the following scale:

5 = Extremely informed

4 = Very informed

3 = Moderately Informed

2 = Slightly informed

1 = Not at all informed

2. When participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with specific statements, they responded using the following scale:

5 = Strongly agree

4 = Agree

3 = Undecided

2 = Disagree

1 = Strongly disagree

3. When participants were asked to provide ratings about their perceptions of the division and their overall satisfaction with communications, they responded using the following scale:

5 = Excellent

4 = Above average

3 = Average

2 = Below average

1 = Very poor

In reviewing the SCOPE Scorecard for LCPS, keep in mind that the division exceeded confidence interval targets for both parent/ family responses and employee responses to the SCOPE Survey. There is a high level of confidence in the survey results.

Perceptions

In 2011, the National School Public Relations Association (NSPRA) embarked on a major undertaking to create a benchmarking framework for school public relations practice that members can use to assess their programs. To accomplish this, NSPRA sought to identify the characteristics that define a district’s communication program as “emerging,” “established” or “exemplary” in seven critical function areas.

As of June 2023, rubrics have been completed for the following critical function areas:

1. Comprehensive Professional Communication Program

2. Internal communications

3. Parent/Family Communications

4. Marketing/Branding Communications

5. Crisis Communication

6. Bond/Finance Election Plans and Campaigns

7. Diverse, Equitable and Inclusive Communications

Within each critical function area (CFA), research teams of award-winning, accredited association members identified top performers in school systems across the United States and Canada. Top performers’ best practices— as demonstrated through essential program components identified for each area—provide a benchmarking framework for school communicators to assess whether their communication programs are emerging, established or exemplary.

Benchmarking against the Rubrics of Practice and Suggested Measures© - Fifth Edition differs from other parts of the communication audit

process in that it is not measuring and making recommendations based on survey results, what an auditor heard in focus groups and interviews, or discovered in district materials. Instead, it addresses how LCPS’ communication program compares to national, benchmarked standards of excellence in school public relations.

CFA 1: Comprehensive Professional Communication Program is the basis for all communications deployed from a school district and is rooted in the communications function residing at the executive management level. Communications are systematic, transparent, two-way and comprehensive. They align with and support the district’s goals and objectives. Ultimately, the foster dialogue, collaboration, understanding, engagement and trust to support student achievement.

CFA 2: Internal Communications recognizes the invaluable role of all personnel as representatives of the district. It includes having a proactive program for providing staff with the skills, information and resources they need to effectively serve as ambassadors.

CFA 3: Parent/Family Communications recognizes the relationship between family involvement/engagement and student success. It includes a proactive communications program to keep parents/families informed about and involved in their children’s education with the ultimate goal of building collaboration and trust to support student learning.

CFA 4: Marketing/Branding Communications acknowledges that increased competition, declining resources, changing demographics, news media scrutiny and the importance of public perceptions are just a few of the reasons districts need an effective marketing program. Having a well-defined and authentically experienced brand promise as part of the marketing strategy helps position a district in the community and supports the district vision.

CFA 5: Crisis Communication demonstrates that no better opportunity exists for districts to show the effectiveness of their leadership and communication than during a crisis. All eyes attention are focused on how a district handles and responds to crises at hand.

CFA 6: Bond-Finance Election Plans and Campaigns addresses specific instances in which districts must receive voter approval before spending the district’s existing funds and/or levying a tax to raise funds for specific purposes. Before residents vote, there are foundational steps for building informed consent through communications on a district’s operating budget, capital project proposal, millage increase or other bond/finance election campaign.

CFA 7: Diverse, Equitable and Inclusive

Communications recognizes that implementing effective, equitable communications and engagement strategies—for daily communication efforts as well as for formal diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives— creates a respectful, inclusive culture that encourages individuals to share their thoughts and experiences without fear of backlash.

As noted previously, each benchmarked area is assessed on a progressive scale:

y Emerging. The program is in the early stages of development and largely responsive to immediate needs or problems, with minimal proactive planning. Goals, if articulated, are loosely defined with minimal alignment with district goals and objectives.

y Established. The program includes a series of defined approaches based on some research. Strategies, tactics and goals are defined. The program aligns with district goals and objectives. Some evaluation may occur.

y Exemplary. The program is conducted according to an articulated plan following the four-step strategic public relations planning process, a model of communications known by the acronym RPIE (Research, Plan, Implement, Evaluate). The program is aligned with and integrated into district strategic plans. It is supported through policy, training and resources. Ongoing evaluation to improve progress is embedded into operations.

When considering the LCPS communication program in light of this benchmarking scale and the essential program components of each benchmarked area, as detailed in the Rubrics of Practice, auditors found the division to be well-established in CFA 4, established in CFA 1 and CFAs 6-7, nearly established in CFA 3, and emerging in CFA 5.

The Recommendations in this report provide insight and advice that will help the LCPS communication program continue to enhance its efforts in each benchmarked area. However, making comparisons against national benchmarks is something that DCE staff can engage in themselves regularly using the Rubrics of Practice. That might involve including self-assessment via the rubrics as an evaluation measure in DCE’s strategic communications roadmap for example.

For more details on the national benchmarks established in the Rubrics of Practice, visit https://www.nspra.org/PR-Resources/Booksand-Publications-Online-Store/Product-Info/ productcd/RUBRICS-2023

The auditors have identified the following items as specific internal strengths (S) and weaknesses (W) and external opportunities (O) and threats (T)—known as a SWOT analysis—affecting the ability of LCPS to achieve its communication goals. Each item is addressed, either as something to build on or try to mitigate, in the recommendations of this report.

y LCPS has long been considered an academically excellent division that offers strong preparation for students as they prepare for college and career with the support and guidance of highly-qualified, dedicated and caring teachers and employees.

y LCPS is a well-resourced district that has been able to build state-of-the-art schools as the division has grown thanks to steady support from the local community.

y New division leadership committed to open and transparent communication offers the opportunity for a reset after several years of disruption due to COVID-19 and highprofile incidents.

y LCPS has a highly competent Department of Communications and Community Engagement with skilled staff who bring a wide range of knowledge, experiences and abilities to the division’s communication program.

y LCPS has a chief communications officer with experience serving in a large district. She is a trusted advisor to the superintendent and has a seat at the leadership table.

y LCPS is located in one of the wealthiest counties in the United States, offering a strong base of highly educated residents who are willing to invest tax dollars to provide highquality schools.

y An increasingly diverse student and staff population widens the array of perspectives on public school education and creates the possibility of new, innovative ideas for serving students and families.

y Recent high-profile events and ongoing media coverage has created a fearful atmosphere among division and site administrators. Afraid of making a mistake and inviting more media attention, they are cautious and slow to respond. Compounding these issues are concerns about protecting student privacy. Together, these factors have produced inconsistent and seemingly incomplete responses, making the division appear less than transparent.

y Responding to higher-than-typical and often negative media coverage requires significant time from communications staff and creates barriers to delivering more positive stories.

y The infrastructure and defined functions of the Department of Communications and Community Engagement staff has not kept up with the demands created by the rapid growth of students and schools in the division, leading to a lack of effective systems and protocols.

y A fragmented approach to the dissemination of information is contributing to confusion and information overload among parents and frustration among teachers and administrators.

y Despite a concerted effort to gather feedback and input from stakeholders, lack of a specific family engagement strategy and a gap in feedback mechanisms for all stakeholders creates an impression that input is not heard or heeded and leads to a lack of understanding about district successes and priorities.

y The division’s proximity to the nation’s capital increases the odds that decisions and crises in LCPS will be subject to high-profile attention that is sometimes politically motivated.

y Local population growth and changing community demographics have increased the challenge of keeping external stakeholders informed of and satisfied with division decisions.

y As in many school systems today, social, cultural and political conflicts in the wider community and nationwide are amplifying some internal and external stakeholders’ sense of division within the LCPS school community.

y The continued prevalence of social media use gives all stakeholders a public platform to share negative perceptions, experiences and misinformation.

LCPS is at a turning point in its efforts to communicate effectively with parents, employees and the community. With new division leadership that is committed to open and transparent communication that engages the community in authentic ways, and as the COVID-19 pandemic and high-profile incidents recede with time, the division has an opportunity to strengthen its stakeholder relationships through strategic communications.

Interviews with school board members, the superintendent, division leaders and members of the Department of Communications and Community Engagement revealed a sincere desire to build on the division’s communications strengths and improve in areas of challenge. LCPS is fortunate to have a talented and highly experienced team in place with the variety of skills needed to implement the recommendations included in this report. While the Department of Communications and Community Engagement plays a fundamental role in ensuring the smooth outflow of accurate, transparent information, it is critical to note that all departments and staff have a responsibility to ensure that LCPS continues to build trusted relationships with its stakeholders. As the

division considers and begins to implement these recommendations, it will be important to involve staff beyond the Department of Communications and Community Engagement.

The following recommendations, which were developed to address specific areas of challenge identified in the audit team’s thorough review of district materials, SCOPE Survey data and focus groups with stakeholders, are listed in a suggested order of priority and are accompanied by action steps that provide tactical ideas for how these recommendations might be accomplished. However, the division may choose to address these recommendations through tactics other than those outlined here.

Some of these recommendations can be implemented immediately, and others may take several years. Generally speaking, a district should not try to address more than two to three recommendations each school year, while also continuing to deliver existing programs and services. This is a long-term effort, and new communication components will need to be introduced as budget, resources and staff capacity allow.

1. Expand the LCPS Strategic Communications Roadmap into a comprehensive communication plan.

2. Leverage new leadership to rebuild trust and confidence.

3. Improve communication infrastructure by developing and consistently implementing communication processes and procedures.

4. Combat misinformation and disinformation.

5. Develop a stronger, more proactive media relations plan that contains a social media component.

6. Strengthen the two-way communications culture in LCPS.

7. Implement tactics to engage local residents with no personal connections to the schools.

The audit team commends LCPS for its commitment to strategic communication and for creating both a Communications Plan Summary for the 2022-23 school year and a more explicit roadmap for the 2023-24 school year. Following are some primary components of an effective strategic communication plan that are already present in the roadmap:

y Target audiences are identified.

y Channels to be used to deliver key messages are prescribed.

y Messages that align with the goals of the division’s strategic plan (One LCPS) have been developed.

y Strategies to support the stated objective of the division’s strategic plan are articulated.

y Specific action steps are incorporated along with a matrix identifying who is responsible for each task.

This plan provides an excellent structure to build upon. In addition, the audit team learned that the Department of Communications and Community Engagement recently held a departmental retreat in which they further refined the mission, strategic direction and goals of their department. At the time of the audit, the communication team leaders had not yet formalized the findings of their retreat but shared the themes that emerged with the auditors. The auditors agree with and support the direction and ideas developed during the retreat and encourage the Communications and

Community Engagement team to incorporate them into an even more comprehensive communication plan along with the findings, recommendations and action steps provided in this audit. This will take LCPS to the next level in strengthening relationships, increasing understanding, building trust and solidifying support for the core values articulated in the division’s strategic plan.

Team members from the Department of Communications and Community Engagement conveyed to the auditors a strong desire and intention to implement a highly strategic communication plan focused on the division’s broad goals. Rising above reactive, tactical communication in a division as large and complex as LCPS can be challenging even for experienced practitioners who are strategically oriented. To address this challenge, the audit team recommends following a planning process that:

y Sets specific measurable objectives to help achieve communication goals;

y Builds upon and expands the existing strategies, action steps, target audiences, key messages, timelines and staff member assignments in the existing roadmap; and

y Sets the evaluation criteria that will be used to measure success.

The audit team is aware that the highly experienced Department of Communications and Community Engagement team already

understands the core components of a strategic communication plan, and the auditors acknowledge that a variety of styles and formats are used by organizations in drafting strategic communication plans. For NSPRA, however, the gold standard is the four-step strategic communication planning model, often referred to by the acronym RPIE (research, plan, implement, evaluate). This planning model is foundational to strategic communications and to earning accreditation in public relations as well as to earning NSPRA’s Gold Medallion and Golden Achievement awards.

The action steps that follow describe components of the RPIE process that can be added to enhance the effectiveness of LCPS’ strategic communication plan.

Highly effective communications are grounded in research, so in a comprehensive, strategic communication plan, it is helpful to begin by detailing the key research findings that led to the identification of priorities for the communication program. The NSPRA Communication Audit Report, including the SCOPE Survey data, provides a wealth of information about the perceptions of LCPS and its communications, which should inform the selection of at least some of the challenges to be tackled or opportunities to be seized by communications staff in their plan. When revising the Communications Roadmap, add a section on research that summarizes key data informing the plan goals and objectives.

Following are additional data sources to consider when developing the research portion of the plan, as they can also help with identifying priorities for communications:

Expand the LCPS Strategic Communications Roadmap into a comprehensive communications plan.