Production

The technology of making sancai was deeply rooted in the ceramic and metallur gical traditions that preceded the Tang dynasty. China appears to have invented the world’s oldest pottery along the Yangtze River, attested by the case of Yuchanyan Cave dated to circa 15,000–18,000 years ago. The following Neolithic period of China (ca. 10,000–2,000 BCE) witnessed the first peak of ceramic production along the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers. Underpinned by increasing population size and social complexity, as well as domestication of various animals and crops, ancient China became able to channel more social energy to expand local ceramic industries. The long-term experience with clays, minerals and high temperature processes also made China better prepared for the Bronze Age (circa 2,000–221 BCE). Whilst bronze metallurgy was very likely introduced to the Central Plains of China from the Eurasian Steppe, early Chinese dynasties chose to adopt this new technology in their own way. Instead of following techniques found in the Eurasian Steppe and Europe, such as lost-wax casting and alloying using arsenic, people in central China chose to use leaded bronze (copper+tin+lead) and piece-mould casting. Lead helped to reduce the melting point, allowing the alloying liquid to sufficiently fill the clay mould and create exquisite decorations. It was the addition of lead that distinguished China from the rest of the Old World. The use of lead exerted a far-reaching impact on the production of various materials throughout Chinese history, exemplified by the lead barium glass and lead glazed ceramics during the Han dynasty (202 BC –220 CE). It was Tang sancai that inherited all these state-of-the-art technologies from different periods of Chinese history.

8

LAM & CO UK

Tang sancai was still highly attractive to the Tang elites and outsiders regardless of local cultural differences; and was widely distributed along the ancient Silk Road, from Central Asia to Europe. Perhaps a more famous example is the discovery of the Belitung shipwreck, which carried a large quantity of Tang exports including various types of sancai, and it was supposed to return to Arabia but sank around 830 CE near Belitung Island, Indonesia. The design of Tang sancai also assimilated elements from outside China. Examples can be found in the figurines riding horses and camels, many of whom represent Sogdians, a group of Iranian merchants linking Tang China to other parts of the Silk Road. Some sancai ewers were also imitations of foreign gold and silver objects.

Production of Tang sancai required two stages of firing. The raw material for the body was almost certainly derived from local soil in the Central Plains of China, such as present-day Henan and Shaanxi provinces. The clay body underwent its first firing at temperatures usually up to around 1100℃. The subsequent step was to apply various types of glaze to the surface of the body. Because they contained lead oxide, a much lower firing temperature around 900–950 ℃ was used in this step. Various types of colours, consisting of amber, brown, green, blue, creamy white, straw, were created by the minor amounts of copper (green), iron (amber or brown) and cobalt (blue), normally around 1–5%. So far, several Tang sancai kiln sites have been discovered, including the Gongyi and Huangye kilns in Henan province, the Huangpu and the Liquanfang kilns in Shaanxi province, and the Neiqiu kiln in Hebei province, providing a tremendous amount of archaeological remains for more in-depth research.

References:

“The Tang Sancai Kiln at Huanye,” edited by The Institute of Cultural Relics at Gongyi Henan. Science Press, 2000.

So, Jenny F., Noble Riders from Pines and Deserts: The Artistic Legacy of the Qidan, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2004.

Wood, Nigel, Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

9

A sancai-glazed lotus petal jar with cover

Henan province Northern Qi dynasty (AD 550– 577) h: 12.5 cm

北齊三彩蓮瓣罐及蓋

A similar piece are found in Tokiwayama Bunko ( 常盤山文庫 ) and Henan museum ( 河南博物院 )

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection, early 2000s

10

11

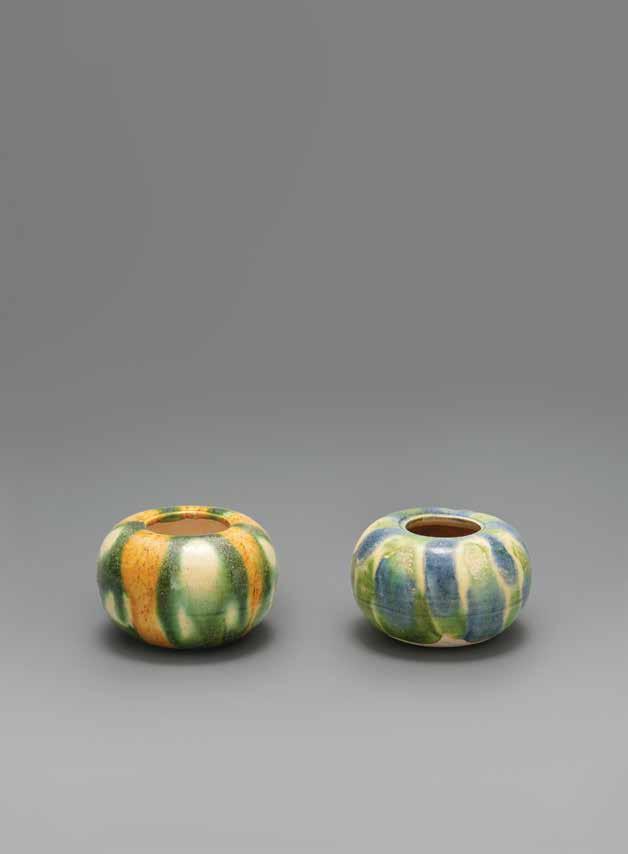

A green and russet-glazed hand warmer

Henan province Sui/Tang dynasty (6th/7th century) d: 11.5 cm 隋/唐 褐綠釉暖手爐

Of rounded shape, the sides with shaped cut-outs, covered overall with a dark russet glaze with scattered green splashes.

Provenance

The Sze Yuan Tang Collection

Sotheby’s London, 4 November, 2020

12

思源堂收藏

13

pair of sancai-glazed pottery figures of horses

Provenance

Chinese

Marilynn

Frank Caro), New York,

Imperial:

19039,

James and Marilynn Alsdorf

2, Christies New York, 24 September, 2020,

14 A

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) l: 23 cm 唐三彩陶馬一對

C. T. Loo

Art (successor

21 March, 1956 The James and

Alsdorf Collection, Chicago 盧芹齋(繼任者Frank Caro),紐約,1956年3月21日 詹姆斯及瑪麗蓮•阿爾斯多夫珍藏,芝加哥 2020 年 9月24 紐約佳士得;崇聖御寶 - 詹姆斯及瑪麗蓮•阿爾 斯多夫珍藏 ( 第二部分) Sacred and

The

Collection Part

sale

lot 898

15

A pair of sancai blue-glazed dishes

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) d: 14 cm

A similar piece is found in The Ten-views Lingbi Rock Retreat Collection.

Provenance

Susan Chen Collection, 1993

Noriyoshi Horiuchi

16

唐朝藍釉三彩盤一對

奉文堂藏

17

A sancai-glazed offering tray

North China Tang dynasty (AD

Provenance

Hong Kong

18

618– 907) d: 29 cm h: 7 cm 唐三彩淺綠寶相花承盤

private collection, 1995

黃釉相間,施以淺綠底色,黃底白點自然寫意,創作手法非常 特別,藝術性很強。唐代工匠在拉坯賦色時造化天然,先以清 麗的綠釉作為底色,復以潑彩暈化點染其上,抽象隨性的黃底 白點彷如鹿紋,營造出綠野仙境之感,獨具匠心,唯美天成。

日本永青文庫、出光美術館、法國吉美博物館及各地均有精品

與此盤相似,但圖案潑彩白點未如此盤活潑生動。

從出土資料和研究顯示,唐三彩不是大眾消費品,而是一種昂

貴的奢侈品,為皇家、貴族和高級官員青睞,常見於墓葬明

器,唐三彩隨葬之風的興起,是唐代朝廷貴族階層引領的結

果。也多見於佛教遺址,西安、成都的佛寺遺址出土資料說明

僧侶也是唐三彩的消費者。武周時期始建的陝西省臨潼慶山寺

20 此盤精美清雅,明豔潤澤,玻璃質感極強如傳世作品,盤內綠

規制極高,是一座皇家供奉的大寺院。開元29年(741),寺 內曾舉行盛大的釋迦佛祖真身舍利供奉法會。塔基中出土的三 彩均為典型的盛唐三彩,其中的三彩寶相花紋盤與此盤類似。 寶相花是我國傳統裝飾紋樣之一,主體脫胎於具有佛教象徵的 蓮花,綜合了牡丹、菊花等花卉的特徵,中間鑲嵌著形狀不 同、大小粗細有別的其它花葉組成,其造型富麗堂皇,寓有“ 寶”“仙”之意,故名“寶相花”。唐三彩中的寶相花渾然天 成,使陶器披上了燦爛奪目的盛裝,造就出獨一無二的大唐文 化符號,深深刻在中國人的文化記憶裡。 治世出精品,盛唐出華彩。此盤造型典雅大方,釉彩光潤,藝 術品味上乘,是盛唐三彩器完美的代表作品。

This sancai-glazed offering tray with a central Baoxianghua motif on a light green and amber resist-stippled ground, is exquisitely luminous, delicate, and yet vigorous. The contrasting green and amber glazes of the central portion, juxtaposed with the pale green periphery, are visually compelling and give an air of indefinable luxury. A white-onamber “deerskin pattern” appears somehow abstract yet representational, pulsing with life, art, and creativity. The Tang artisan, through his mastery of execution and tonality, has produced an extraordinary object of beauty and originality.

Pieces of comparable quality in the Eisei Bunko Museum, the Idemitsu Museum of Art, and the Musée Guimet are never theless not the equal of the present piece in its sheer vibrancy of pattern and stippling.

Ongoing research and archaeological evidence indicate that Tang Dynasty tri-color glazed wares, as well as providing burial goods for furnishing elite tombs, were also produced for the aristocracy and members of the imperial court as luxury items. They have also been found at Buddhist sites, and excavations in Xian and Chengdu show that these wares were similarly used by Buddhist monks.

Sancai pottery typical of the heyday of the Tang dynasty have been excavated from the foundations of the pagoda belonging to the Qingshan temple in Lintong, Shaanxi Province. This temple was built during the Wu Zhou period, dedicated to the imperial family, and a grand ceremony to consecrate relics of the Buddha Shakyamuni was held there in the 29th year of the Kaiyuan era (741 AD).

The tray is incised with a central Baoxianghua, a six-lobed floral medallion with interlocking petals in deep green which forms the surround for a central hexagonal green and amber floret. Around this is a resist-glazed area of cream spots on an amber ground which flares into the pale green periphery of the dish, the colour extending beyond the rim to the base which is supported by three loop feet.

The “Baoxianghua” (treasure-like flower) is a traditional decorative device popular during the Sui and Tang Dynasties, representing majesty and beauty. It is an auspicious composite motif derived from the lotus—a Buddhist symbol, combined with features of the peony and the chrysanthemum.

This tripod tray is a work of art of rare beauty that epitomises the sophistication and cultural achievements perched at the apogee of the extraordinary and glorious Tang dynasty.

21

A sancai-glazed offering tray

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618– 907) d: 24 cm 唐三彩藍釉寶相花承盤

Similar pieces are found in Regina Krahl, “A Collection of Chinese Ceramics in Berlin,” Berlin, 2000, pages 136–137, no. 108; Margaret Medley, “T’ang Pottery and Porcelain,” London, 1981, color plate C; Michael Sullivan, “Chinese Ceramics, Bronzes and Jades in the collection of Sir Alan and Lady Barlow,” London, 1963, plate 20b.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

22

23

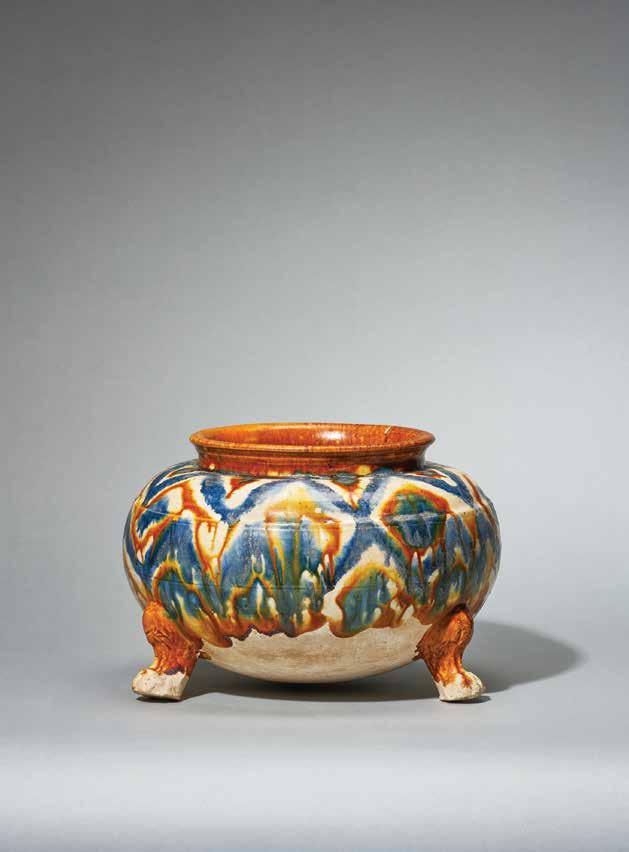

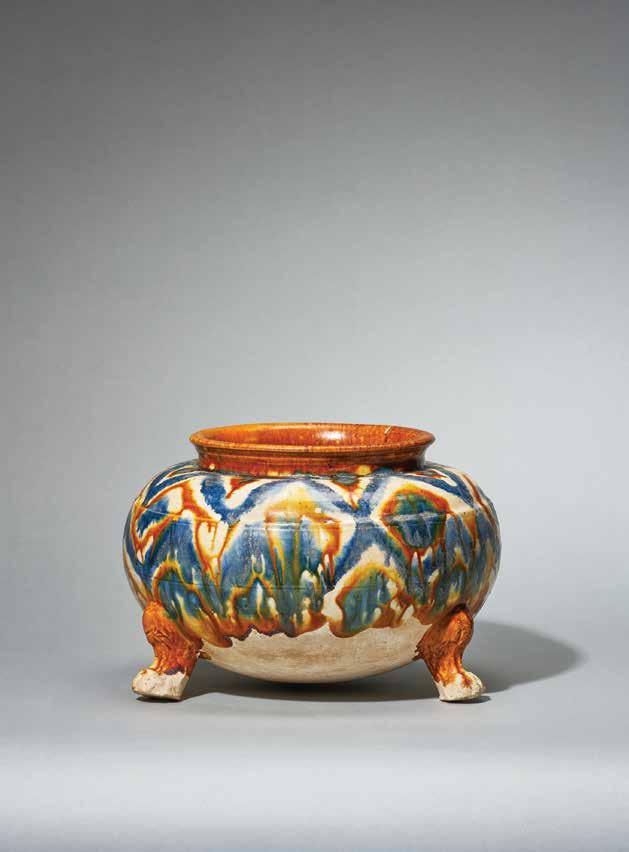

A blue and amber splashed pottery tripod

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 16 cm 唐三彩藍釉三足罐

The compressed globular body raised on three lion-paw feet, the upper body with a glaze with repeating geometric pattern in blue and amber, beneath the amber-glazed short neck and everted rim.

A similar piece is found in Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, Volume One, by Regina Krahl, no. 238.

Provenance

Iva and Flores, December 1998

Bonhams Los Angeles, December 2020

24

25

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 16.2 cm

The present tripod jar and cover is a particularly fine example, with finely-molded appliques and well-controlled splashed colors in the sancai glaze. Another finely-executed jar, also with a cover, was included in the exhibition Cina a Venezia. Dalla Dinastia Han a Marco Polo in 1986, and is illustrated in the Catalogue, Milan, 1986, p.189, no, 99. Another jar and cover of comparable quality is illustrated by Liu Liang-yu, Early Wares. Prehistoric to Tenth Century, Taipei, 1991, p. 213.

A sancai-glazed pottery tripod jar with very similar molded floral appliques, but of smaller size (13.3 cm. high), from the Dexinshuwu Collection, was included in The Special Exhibition

of Tang Tri-Colour, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1995, p. 139, and subsequently sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 4 October 2016, lot 3. A sancai-glazed tripod jar and cover with similar appliques was sold at Christie’s New York, 14–15 September 2017, lot 1107; and a sancai-glazed tripod jar and cover without appliques, from the collection of Frederick A. and Sharon L. Klingenstein, was sold as Christie’s New York, 13 September 2019, lot 834.

Provenance

The Property of a Gentleman; Christie’s New York, 22 March, 1999, lot 252 Christie’s New York, 24 September, 2022

Published

The Tsui Museum of Art, Chinese Ceramics I: Neolithic to Liao, Hong Kong, 1993, no. 130

26

A rare, finely-moulded sancai-glazed pottery globular tripod jar and cover

唐三彩貼花三足蓋罐

27

sancai blue glaze basin

28 A

Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) d: 29.5 cm 唐三彩藍釉宝相華文洗 Provenance Hong Kong private collection

29

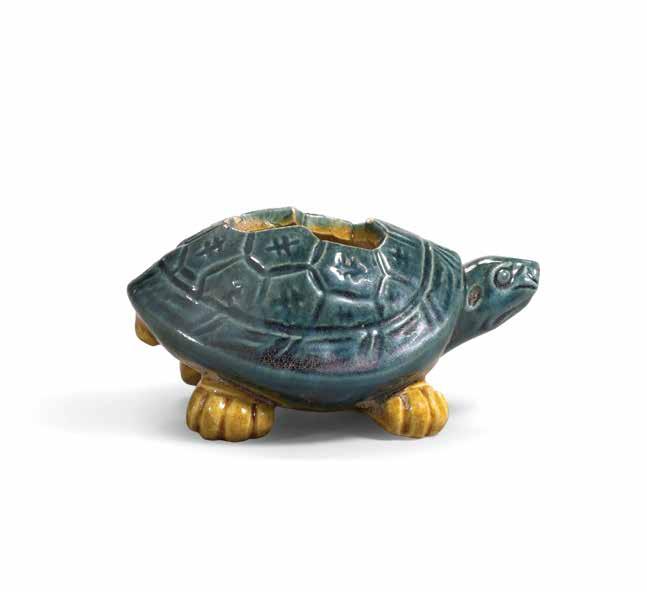

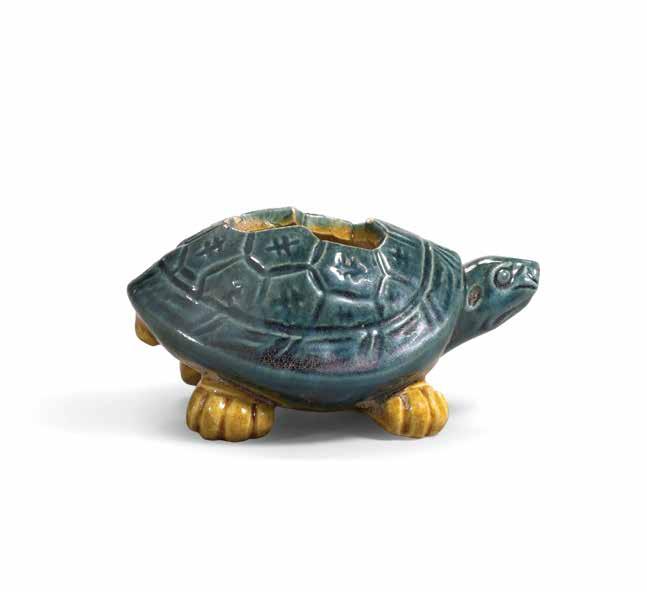

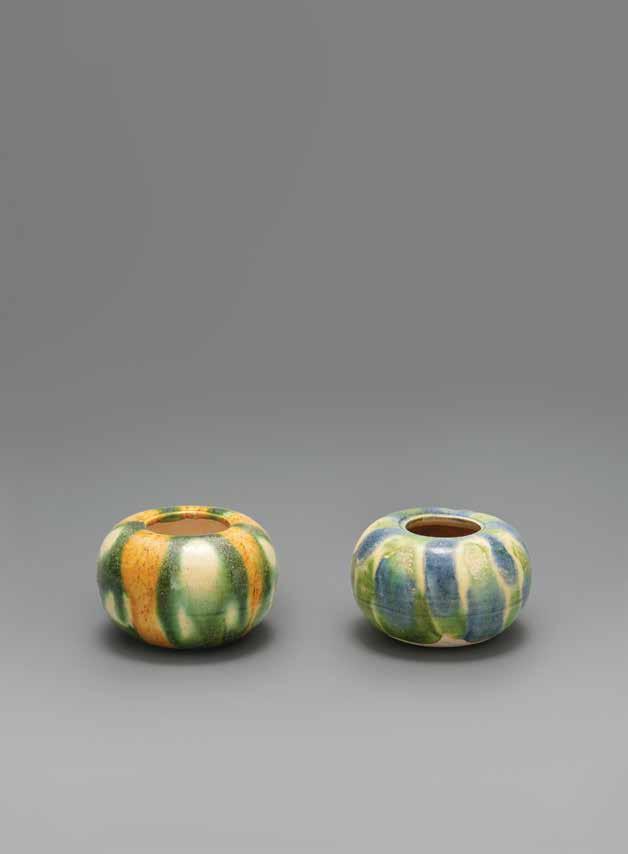

sancai blue and amber-glazed “tortoise” waterpot

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–

Provenance

The Sze Yuan Tang Collection

Sotheby’s London, November 2020 Hong Kong private collection

30 A

907) w: 8.5 cm 唐三彩藍釉龜形水注

思源堂收藏

31

A sancai and blue-glazed pottery box and cover

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) d: 6.2 cm

唐三彩加藍蓋盒

Of flattened circular form, the cover with seven cream-andamber dapples reserved against a cobalt-blue ground, the sides of the cover and box both splashed with cream and amber glazes, the interior of the box cream-glazed, the interior of the cover and the base of the box unglazed revealing the pinkish clay.

Provenance

Sotheby’s New York, September 2021

32

33

A dappled blue-and-amber-glazed box and cover

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) d: 2½ in., 6.4 cm 唐三彩加藍蓋盒

Of circular section, the exterior mottled with attractive blue and amber glaze splashes stopping just above the foot revealing the cream-colored body.

Provenance

Sotheby’s New York, September 2021

34

35

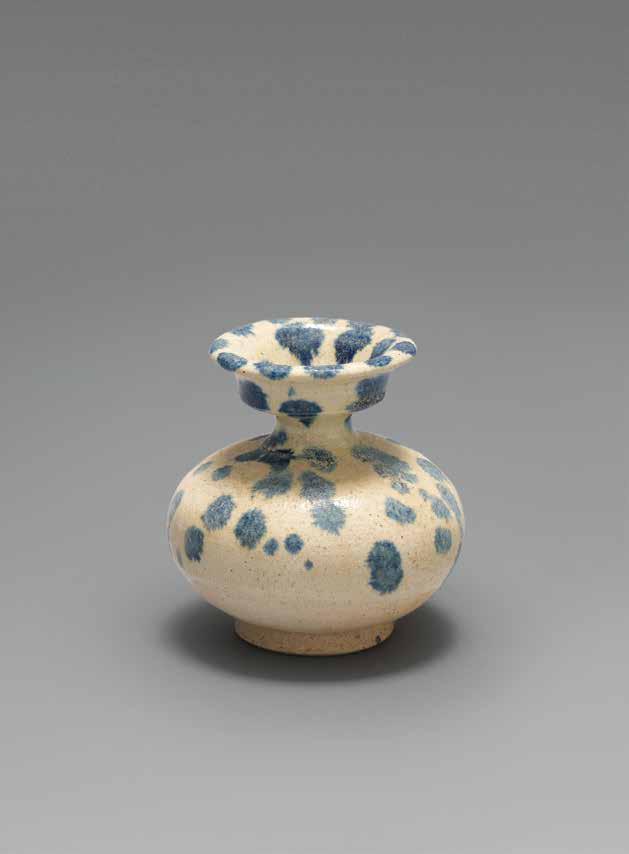

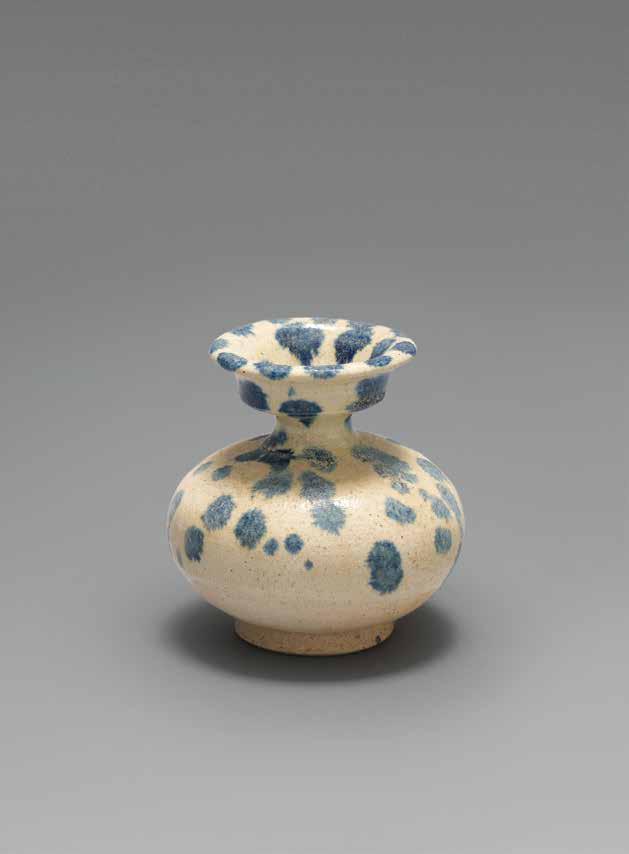

A blue-splashed vase

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 7.8 cm

唐白釉藍彩唾壺

The compressed globular body rising to a waisted neck and a upturned dish mouth, covered with a thin layer of white glaze accentuated with irregular blue splashes.

A similar piece is found in Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, Volume One, by Regina Krahl, no. 256.

Provenance

The Sze Yuan Tang Collection

36

思源堂收藏

37

A blue and sancai-glazed pottery equestrian

Shaanxi province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 27.5 cm

Provenance

Schmeider collection, Paris

Eskenazi, “Twenty five years,” London 1985

Eskenazi, Tang ceramic sculpture, New York, March 2001

Sotheby’s New York, March 2022

38

唐三彩藍釉人騎馬

A pair of sancai-glazed ferghana horses

Xi’an region, Shaanxi province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 40 cm

Molded and modeled pinkish-white earthenware covered in yellow, amber, blue, green, and cream lead-fluxed sancai glazes

Provenance

The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers by Robert D. Jacobson, PhD

42

唐朝三彩馬

舞馬千秋萬歲樂府詞(之三) 張說 遠聽明君愛逸才、玉鞭金翅引龍媒。 不因兹白人間有,定是飛黄天上来。 影弄日华相照耀,噴含雲色且徘徊。 莫言闕下桃花舞,别有河中蘭葉開。

This exquisite pair of Tang sancai horses exhibit an extremely rare combination of amber and blue glazes.

Similar in size and physiognomy, they have elegant, sleekly modelled heads turned to one side, and tails docked and tied in standard early 8th century style. Bridles and chest and crupper straps are variously hung with magnificent sets of medallions, bells, and tassels.

Their main difference lies in the treatment of the manes and the saddles:

The amber-glazed horse has a fan-shaped forelock, a hogged mane, and a large amber blanket brushed to simulate fur that completely covers its saddle, whereas the white horse has a mane combed to its left, while a resist-glazed saddle in amber and white with cobalt blue border lies on a saddle cloth patterned in blue, white, amber and green.

These magnificent Fereghan horses reveal the technical mastery and supreme artistry that epitomised ceramic sculpture at the peak of the Tang dynasty.

45 唐三彩馬一對,其造型釉色獨特,馬飾上的浮雕創作殊為罕 見。一匹通體施以嫩黃色釉,馬身點綴寶藍色的馬飾,短剪鬃 毛,鞍韉覆蓋黃釉毛氈,藍釉項帶鏤空穿過馬脖,絡頭掛藍釉 雕花二端藍釉長鬃。另一匹通體施白釉,披長浮雕鬃毛,鞍韉 蓋藍、黃、白、綠釉馬鞍。二馬攀胸垂掛浮雕鈴鐺銀花飾物, 雲珠貼藍釉浮雕花朵,馬韁上掛滿藍釉浮雕銀花,尾部絡絲 帶。唐人尚馬,皇家貴族喜豪飾愛驅,特別是在禮樂宴會與御 前舞馬,馬裝飾各盡豪奢,玉鞭金翅,華相照耀,唐馬為時代 文化精神之象徵。這一對三彩馬釉色鮮麗明亮,造型生動駿 美,神態比例無可挑剔,飾物精美華麗,是盛唐三彩馬中美學 翹楚,應是宮中汗血寶馬的形象。 翩翩白馬稱金羁,領綴银花尾曳絲, 毛色鲜明人盡愛,性靈馴善主偏知。-白居易

A sancai-glazed lady holding a bird

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618– 907) h: 40 cm

唐三彩獵裝仕女俑

Molded and modeled whitish earthenware, unglazed head painted with black and red pigments on a pinkish ground, costume covered in straw-yellow and green lead-fluxed sancai glaze.

Provenance

The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers by Robert D. Jacobson, PhD

46

A sancai blue-glazed court lady

Shaanxi province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 33 cm

Molded white earthenware with white ground, head painted in black and red pigments, costume with lead-fluxed sancai glaze in blue, light-blue, dark-amber, cream, and green colors. A similar piece is found in the Shaanxi Museum.

Provenance

The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers by Robert D. Jacobson, PhD

48

唐三彩藍釉仕女俑

A sancai blue-glazed seated lady

Luoyang region, Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 30 cm

Molded white earthenware, unglazed head painted with pink, red, and black, torso with cobalt blue, amber, and cream leadfluxed sancai glaze.

A few closely related examples with the same seated pose and hairstyle seen here have been excavated, and others are recorded in public and private collections.

A similar piece is found in The Ten-views Lingbi Rock Retreat Collection.

Provenance

The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers by Robert D. Jacobson, PhD

50

唐三彩藍釉坐鼓仕女俑

51

rare and beautifully modelled blue and amber-glazed pottery figure of a court lady North China Tang dynasty (AD 618-907) h: 26.7 cm

Provenance

A Danish private collection

Collection of Louis Foght, Copenhagen Bruun Rasmussen, April 1960, lot 892 Sotheby’s Paris, June 2021

52 A

唐三彩藍釉仕女俑

53

A pair of sancai blue-glazed foreign merchants

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) 唐三彩藍釉商人 h. 20 cm

Molded and modeled white earthenware with unglazed heads painted in red, black, and pink, with costumes covered in cobalt blue and amber lead-fluxed sancai glazes.

Provenance

The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers by Robert D. Jacobson, PhD

54

A pair of sancai blue-glazed earth spirits

Shaanxi province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h. left: 42 cm h. right: 46 cm 唐三彩藍釉鎮墓獸

Molded and modeled red earthenware covered with amber, blue, green, and white sancai lead-fluxed glazes on a white ground; unglazed faces painted with red and black pigments.

The origin of these composite tomb-guardian beasts may go back to the ancient genie/exorcist Fang Xiang, whose purpose was to drive away sickness and evil spirits. The Feng Sudong, a Han work on popular beliefs, states:

There is a vulgar superstition that the spirits of the dead roam abroad therefore the Ch’i-t’ou is made in order to keep them in one place. It is so called from its having an ugly big head. The name for it in another dialect is Ch’u-k’uang “He who abuts on the grave.”

Provenance

The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture Published Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers by Robert D. Jacobson, PhD

56

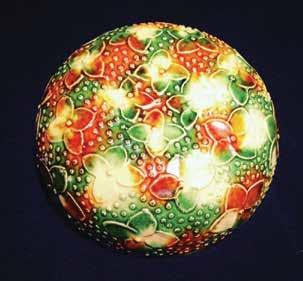

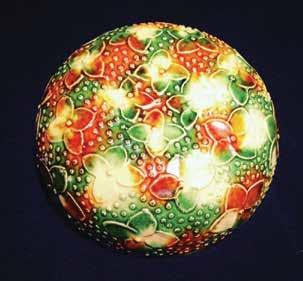

A rare sancai-glazed quatrefoil floret moulded design bowl

North China

Tang dynasty (AD 618–907)

d: 11 cm

唐三彩四瓣花印紋鉢

Provenance:

Japanese private collection

KOCHUKYO Tokyo 東京壼中居

此鉢滿釉支釘燒制,釉色分佈光亮鮮艷,杯內綠地白點,清雅

華麗,佈滿四瓣花朵,如春日的花園,万紫千红,爭艷競麗, 是非常罕見的唐三彩佳作。

四瓣花圖案於中國古代始見於庙底沟彩陶,戰漢時期的銅鏡與

漆器也常見;有柿蒂花一説,因其花紋的形狀像柿子分作四瓣

的蒂而得名。也有方花一說,认为它該叫“方花纹”。李零教

授依據戰國銅鏡銘文"方华蔓长,名此曰昌”,“ 华”与“ 花”同音,因此叫做“方花”。

This bowl with its bright and lustrous contrasting glazes is a rare masterpiece of Tang sancai ware. The interior of white spots on a green ground gives an air of luxury and elegance, while the exterior is covered with a splendid pattern of raised studs and quatrefoil florets reminiscent of a garden in springtime.

The quatrefoil flower motif first appeared in ancient China on the painted Miaodigou pottery, and is often seen decorating the bronze mirrors and lacquerware of the Warring States and Han periods.

One name given to this motif is the “Persimmon Flower”, because the shape of this floral device resembles the fourpetalled calyx of the persimmon.

An alternate designation is the “Square flower”: Professor Li Ling, based on the inscription on a Warring States bronze mirror: “方华蔓长、名此曰昌” ,and because 华 and 花 are homonymous, named it the “方花” or “Square Flower”.

58

59

Two small sancai-glazed bowl

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 3.5 cm each

唐三彩鉢

A similar piece is found in Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, Volume One, by Regina Krahl.

60

61

A sancai-glazed bowl

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 5.5 cm With Japanese box 唐三彩鉢

A similar piece is found in Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, Volume One, by Regina Krahl.

62

63

A sancai-glazed bowl

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 5.4 cm With Japanese box 唐三彩鉢

A similar piece is found in Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, Volume One, by Regina Krahl.

64

65

A blue-glazed globular jar

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618– 907) h: 6 cm

唐三彩藍釉小罐

A similar piece is found in The Ten-views Lingbi Rock Retreat Collection.

66

67

A sancai-glazed dancer flask

Henan province Tang dynasty (AD 618– 907) h: 15.7 cm

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

68

唐三彩樂舞圖扁壺

69

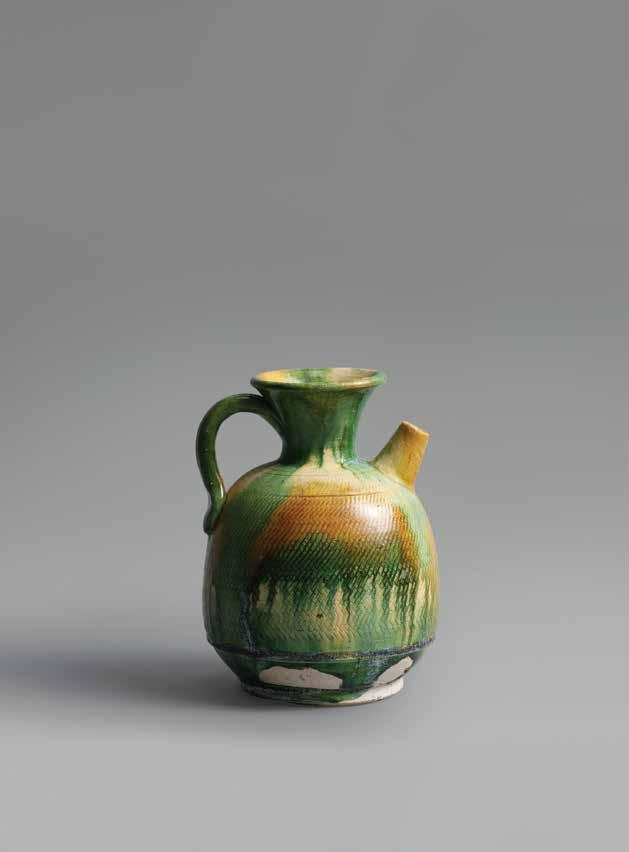

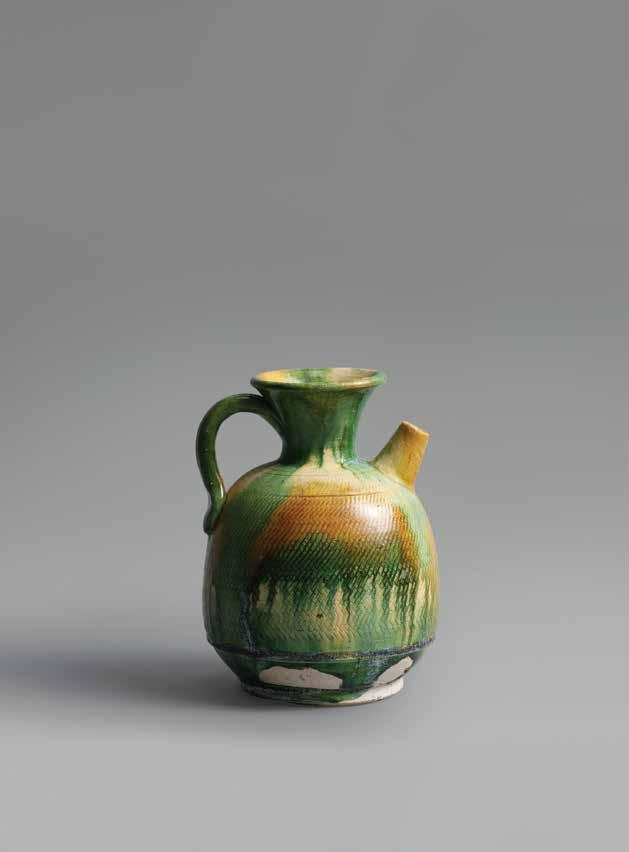

A rare sancai-glazed ewer

North China Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) h: 13 cm

唐三彩執壺

The ovoid body rising to a wide flaring neck, set with a short cylindrical spout and a high arched handle, the body with incised hatching, glazed predominantly in green with amber highlights, stopping irregularly around the base exposing the earthenware body.

Provenance

The Sze Yuan Tang Collection

70

思源堂收藏

71

A sancai lobed dish with moulded design

North China Liao dynasty (AD 907–1125) d: 14 cm

遼三彩印花花口盤

The octafoil dish molded and stamped with flower heads on each petal under a ‘combed wave’ band and central open blossom, the design picked our in amber, green and ivory glaze, the base showing the hard, buff body.

Provenance

Bonhams Los Angeles, 26 July, 2020, lot 1042

72

73

A green-glazed lobed dish with fish and lotus moulded design

North China Liao dynasty (AD 907–1125) d: 17.5

74

cm 遼代綠釉印花花口盤

75

A large amber-glazed bowl with beribboned flower pattern

North China Liao dynasty (AD 907–1125) h: 30

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection, 1990s

76

cm 遼代褐釉刻花大盌

77

Lam & Co UK

4 Mason’s Yard, London, SW1Y 6BU

Email: gallery@lamcouk.com www.lamcouk.com

Lam & Co Antiquities

2/F 151 Hollywood Road, Central, Hong Kong

Email: chrisantiquities@gmail.com

Info: gallery@lamcoantiquities.com www.lamcoantiquities.com