Chaos, Animals, Creativity

Chaos is perilous, as evidenced by historical events. Examples include the upheaval caused by the belligerent Five Barbarians resulted in significant casualties among the Han populace. The downfall of the Tang dynasty following the An Lushan rebellion precipitated widespread terror and chaos, characterised by social turmoil and territorial fragmentation. At times, as shown by the Qing dynasty, chaos brewed for years before erupting, leading to catastrophic weakening and signalling the death knell for the dynasty, after which a new cycle began.

Humans, descended from the Sahelanthropus tchadensis around seven million years ago, have evolved and gradually come to dominate the planet from other vertebrates, partly due to the favourable conditions of the Holocene. Throughout this time, however, they have also been curious about the origins of the world, the stochastic nature of their surroundings, and the void that preceded creation, for the cost of ignorance is beyond comprehension. Creation myths from around the world often start similarly: with only darkness and murkiness. The universe was neither dead nor alive, day nor night, sky nor earth (The Hymn of the Dark Beginning, from the Hindu Rigveda, c. 1500 BCE); all was obscure and dark, formless and shapeless before there was Heaven and Earth Huainanzi, c. 139 BCE); dark and nebulous Chu Silk Manuscript, c. 305 BCE). Such a state of primal chaos, known as Hundun in Chinese, was later mythicised in Han dynasty (206BCE–220CE) as a lifeless creature shrouded in darkness on Kunlun Mountain.

Each religion or school of thought has its own thinking of what constitutes a harmonious state to stave off chaos. The Confucius sought to restore human moral compass through rituals, as advocated by Xunzi (313–238 BCE) in his Discourse on Ritual, whereas the Daoist would perceive the presence of chaos as the natural rearrangement of existing things, merely the Dao flowing in its countless forms in the protean and dynamic universe. The idea of constant mingling of Yin and Yang, where each struggle for dominance but relies on the other for balance, indicates the importance of achieving

harmony from within to reduce Heraclitean uncertainty, as chaos in any form can be potentially lethal. And it is through exploring different ways of containing uncertainty in our interactions with the environment that we accumulate knowledge and wisdom, establish law and order, foster creativity and construct sophisticated civilisations.

The perennial question of what constitutes creativity continues to provoke debate. During military upheavals in the past, individuals striving for survival developed novel strategic thinking, which influenced the creation of seminal works such as The Art of War. Our interest in the order of nature led to the creation of Ching and principles of Feng Shui. The spread of influence of the religious beliefs and schools of thought in China, notably Daoism (pantheistic and protean), Confucianism (agnostic and fastidious), and Buddhism (imported and esoteric), contributed to the creation of many objects that encapsulate their ideologies. The development of various ritual practices commemorated local heroes, honoured ancestors, showcased filial piety and marked the beginning of a rich cultural tradition.

Agriculture, in particular the development of irrigation, was a major step forward in leading us to an agrarian society, freeing us from the nomadic lifestyle, and providing the soil from which hierarchies and creativity sprout. Skilled craftsmen in ancient China made notable contributions across various artistic fields, including architecture, sculpture, and crafts, with their work encompassing elaborate jade amulets, bronze instruments, pottery, ceramics, porcelain, and ritual objects. These creations symbolised the progress of a civilisation, fostering connection among its subjects and allowing them to enjoy collectively the blessing of heaven. Creativity also extends beyond craftsmanship. For instance, Research on Archaeology with Drawings (Kao Gu Tu) by Lu Dalin (1042–1092), compiled in response to the popular antiquarianism during the Song dynasty, a period renowned for its rich diversity and artistic achievements, buoyed by economic prosperity and the thriving ceramics industries. Similarly, the seventeenth century

v

encyclopaedia The Exploitation of the Works of Nature (Tiangong Kaiwu) by Song Yingxing (1587–1666) exemplifies how the compilation and synthesis of earlier works and anecdotes can lead to the creation of something comprehensive and novel. Those with a repertoire of vocabulary, satirical ideas, and fantasies, went on to create some of the best-selling novels, tales and legends that are still celebrated today.

Both wild and domesticated animals such as dogs and oxen (pp.16–19) have always been an inseparable element of human life and have served as subjects for philosophical discussions. Some Confucians thinkers such as Dong Zhongshu (c. 179–104 BCE) pondered how the human body, with its 360 joints corresponding to the number of heavens, held a higher place among creatures. They claimed that only humans could cultivate and realise virtue through deliberate practice. It’s interesting how humans and many other mammalian species display the same reaction when frightened, but this did not concern philosophers of the time—not everyone would go cuckoo like Nietzsche after witnessing a horse being whipped. Therefore, the doctrine of right livelihood in Buddhism—the idea that humans and animals were all capable of moral standards—was attacked by officials such as He Chengtian (370–447), but not rejected in its entirety. Rather than being merely a noble quest for morality debated by the privileged few, interactions with animals also spark creativity in myth. For instance, Fuxi was inspired to invent fishing after observing a spider weaving its web. Similarly, Suirenshi had an epiphany and learned to make fire by rubbing two twigs together in quick succession, inspired by the actions of woodpeckers.

One could deduce from these accounts that creativity is, to some extent, spurred or accompanied by the presence of chaos and animals. Nevertheless, all these subtle emotions, artworks, literature and poems, each resonating deeply with us, would not be possible in the absence of mind and the brain.

Many prominent historical figures, in their attempts to decipher human nature, believed that the heart to be the origin, a view supported by the philosopher Guan Zhong (c. 720–645 BCE), who considered it the centre of the body, encompassing all its functions and senses. In the grand scheme of things, the heart and the brain hold equal survival value (whether you’re a fan of Plato or David Hume), despite the ongoing strife between them. After all, humans, miraculously endowed through encephalization with more neocortex and potent computational power than other animals, permitting us to “make infinite use of finite means,” as noted by Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), though with brains sometimes goofy and irrational. Yet, these “madness” traits can sometimes lead to creativity. According to Simonton’s table in Greatness: Who Makes History and Why (1994), Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt, Kandinsky, Francisco Goya, and Toulouse-Lautrec are speculated to have suffered from schizophrenia, while Michelangelo, Raphael, Rothko, and Van Gogh are thought to have had affective disorders. Even Socrates was said to have had a hallucinatory “demon” as an inner adviser. The predictive value of Aristotle’s observation that “There was never a genius without a tincture of madness” is perhaps still relevant today. Though, it could be that they simply had their imagination and creativity unfettered by the constraints of reason, unless one was feigning madness like the painter Zhu Da (1625–1705), a.k.a Bada Shanren.

Being in thrall to the brain allows us to perceive light and, consequently, colour through the eyes, which transmit information at a rate of 10 million bits per second. Without the brain and its functions working in concert, we would be unable to appreciate the beauty of the Han figurines (pp. 10–15) or the sublime vitrification of the colourful ceramics such as Longquan, Jun, Ding, Cizhou, Jizhou, and Qingbai, beginning on page 28 of this catalogue. Colours, traversing the interplay between light and shadow, have become integral part of our lives through which we express our emotions and creativity,

be it in art or other domains. As Paul Cézanne put it, “colour is the place where our brain meets the universe.” The world would have been so much different if humans, by default, were monochromats like dolphins and whales.

Regardless of how the future unfolds, the brain will remain as the source of creativity. Though some may emphasise the hijacking role of gut bacteria, microbes or even parasites in our body in shaping our creative minds (another story). Did the cruel supplicant, descended from the Gandhamadana Mountain, simply demand the head of the benevolent and handsome King Candraprabha to test the king’s resolve? If so, then he should have been satisfied with the jewelled heads prepared by the minister Mahacandra. However, he valued authenticity, thus the king gave up his head at the supplicant’s behest. How sad that the king lacked the regenerative ability of the planarian worm. The pages that follow showcase a selection of exceptional Chinese works of art, where each glint of light and shadow on these artifacts reflects the cultural opulence of Imperial China and the creativity of those from the distant past. Despite the potters’ harsh living conditions—vividly portrayed by Mei Yaochen in his poem The Potter (1036)—they managed to create many aesthetically pleasing artworks for us to be inspired in the present. Each new technique acquired by the potters, building on their mastery of the existing methods, paved the way for more creative stylistic approaches, resulting in more intricate pieces to be fired to meet the evolving tastes of their patrons. Such a rich legacy of artistic evolution and transition, stretching back long periods of time, ought to detach your mind momentarily from the hurly-burly of daily life. Whether you have the same aesthetic taste as Qianlong emperor’s extravagance, Xue Baochai’s modesty and minimalism, or the Song people’s emphasis on delicate expression and spatial harmony, welcome to the world of Chinese art.

Lam & Co UK October 2024

Bibliography

Bostrom, N. Superintelligence: paths, dangers, strategies Oxford University Press, 2016

Cobb, M. The Idea of the Brain. Profile Books, 2020

Fox, J. The World According to Colour. Penguin Books, 2023

Gregg, J. If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal Hodder & Stoughton, 2024

Grovier, K. The Art of Colour. Thames & Hudson, 2023

Hung, W. Chinese Art and Dynastic Time. Princeton University Press, 2022

Kerr, R., Wood, N., Cai, M., & Zhang, F. Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part XII: Ceramic Technology Cambridge University Press, 2004

Klaas, B. Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters John Murray Press, 2024

Liu, T. T. The Chinese Myths: A Guide to the Gods and Legends Thames & Hudson, 2022

Lopez, D. Buddhist Scriptures. Penguin Classics, 2004

Ni, X. C. Chinese Myths. Amber Books Ltd, 2023

Simonton, D. K. Greatness: Who Makes History and Why Guilford Press, 1994

Sterckx, R., Siebert, M., & Schäfer, D. Animals Through Chinese History: Earliest Times to 1911 Cambridge University Press, 2019

Wilhelm, R., & Martens, F. H. Chinese Fairy Tales and Legends. Bloomsbury China, 2019

Rare black pottery “egg-shell” vessel

Neolithic period, Longshan culture, 3rd millennium BC h: 11.5 cm

新石器時代 龍山文化蛋殼黑陶壺

Exceptionally fine for its even potting in a carinated profile and features paper-thin walls with concentric lines and distinct perforated holes. It has a wide mouth that rises from a splayed foot and exhibits a glossy sheen throughout. The use of the potter’s wheel, a technological breakthrough from the Dawenkou culture, was pivotal during this period. Combined with refined clays and high-fire kilns, it enabled the creation of technically advanced Neolithic wares. The Longshan culture of northern and northeastern China, originating in Shandong, is renowned for its eggshell-thin, hard, black-burnished pottery.

Provenance

The Collection of Julias (Julius) Eberhardt

奧地利著名建築師、中國藝術品收藏家:朱利思. 艾伯哈特 珍藏

Published Regina Krahl, Sammlung Julius Eberhardt Early Chinese Art, Vol. 1, p. 62.

Similar Example

For a similar beaker, see Wu Shichi’s Zhonguo Yuanshi Yishu Beijing 1996, p. 34, fig. 6.

類似器形請參見吳詩池著,《中國原始藝術》,1996年北京 版,第34頁,圖6。

Gilt bronze and turquoise belt-hook (daigou)

Eastern Zhou dynasty (c. 771–221 BC)

l: 13.5 cm

東周 鎏金嵌松石長臂猿青銅帶鈎

The Chinese revered the gibbon as “the aristocrat among apes and monkeys,” also regarded as positive moral exemplars embodying virtuous filial Confucian values, and metaphorically comparable to the recluse (yinshì 隠士). Their long limbs were believed to assist in Daoist practices for cultivating qi, associated with longevity, and they were thought to possess mystical powers. This made gibbons popular pets among the literati. In Liu Zongyuan’s essay “Zeng Wangsun Wen” 憎王 孫文 (Essay on the Hateful Monkey Breed), the macaque is portrayed as the “bad monkey,” while the gibbon is considered the “good monkey.” This gilt bronze belt hook, inlaid with turquoise, is exceptionally well-preserved, shaped like a gibbon with one arm extended forward and the other pointing in a different direction.

“Last night beneath Mount Wu, the cries of the gibbons echoed long in my dreams.”

—Li Bai

昨夜巫山下,猿聲夢裡長。

——李白《宿巫山下》

該件非常罕見的猿形青銅鎏金帶鉤,鑲嵌的松石保存得特 別完好,猿猴呈跳躍攀援回首狀,猿側身前視,單臂前伸,雙 目炯炯有神,鉤體是長臂猿的身體,鉤頸與鉤首是伸出的手 臂,帶鉤的設計極其巧妙,形象生動,活靈活現,表現了極為 豐富的想像力,反映出當時工匠無可挑剔的技藝和東周貴族極 高的審美觀念。

中國人將長臂猿尊為猿與猴的貴族,也被視為積極的道德 典範,體現了美德孝順的儒家價值觀,並隱喻了可與隱士相媲 美。他們長長的四肢被認為有助於道家修氣,與長壽有關,因 而被認為擁有神秘的力量。這使得長臂猿備受文人推崇,在劉 宗元的《憎王孫文》中,獼猴是被描繪成“壞猴子”,而長臂 猿被認為是“好猴子”。

Provenance Eskenazi Ltd, London

Japanese private collection

Hong Kong private collection

Published

Giuseppe Eskenazi and Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand: The Chinese Art World Through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi, 2012.

Scabbard slidewith stylized chi-dragon

Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD)

d: 5 cm

漢 淺浮雕螭虎紋劍璏

In white nephrite with slightincrustations of rust, the surface of this slide is finely polished over its low-reliefsurface, with an orthodox decoration of what is often now referred to as “clouds” and a “beast face”, its eyes protruding on one end. In fact, it illustrates a chi-dragon, representing bravery. On this piece, the otherwise standard design has a unique addition: the furry tail of the dragon incised on its back end.

白玉,稍帶紅沁,表面用淺浮雕技法裝飾,抛光精細,似 有使用痕跡。漢代劍璏上此類紋飾常為稱爲「獸面紋」,特點 是上端有一對從抽象雲紋中突出的眼睛,其實這類紋飾仍然是 螭紋,而螭代表勇武是當時裝飾劍器的正統紋飾。這件精彩的 作品的特點是用陰綫在末端刻畫了螭虎的尾巴。

Provenance

American private collection

Sword pommel with petal pattern in low-relief

Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD)

d: 5 cm

漢 柿蒂紋劍首

This hefty pommel was made of a hard celadon jade which is now covered in a surface calcification, yet retains a glossypolish. Inside its elegant funnel-shaped top, four persimmon petals are carved in shallow relief and slightly overlap the surrounding interlocking grain patternthat reinterprets a Spring and Autumn period motif. The bottom is pierced with an ox-nose hole for fixing it to a sword hilt.

青玉,通體薄沁,器表色澤光潤。用精彩的淺浮雕技法構 成的四瓣柿蒂自然延申至周邊的勾連穀紋,正面是優美的抛 物形曲面,器型相當考究,反映出當時當代高超的審美水平。

Provenance

American private collection

Bronze dragon/loong

Six Dynasties period, 6th century l: 28 cm

六朝 銅走龍

This bronze solid-cast dragon is a striking embodiment of both grace and power. Meticulously sculpted, it features a formidable head with a long, branched horn, open jaws revealing sharp teeth, and a distinct tongue. Wisps of hair frame its head, which sits on a sinuous neck connected to the straight ridged body covered in finely engraved scales. The dragon’s dynamic stance is accentuated by its forward stride on four robust legs, each joint adorned with tufts and ending in a paw with three sharp claws. Its tail curves elegantly behind. The figure is covered in a natural green patina with much of the original red pigment still visible inside the ears and mouth.

這青銅實心鑄龍是優雅和力量的體現。雕刻精美,具有令 人敬畏的高昂的頭部,長而分叉的角,張口吟吼,長舌前伸如 劍,上吻較長。頭頂雙角向後平伸,角上飾有凸結,眼神凌厲 直視前方。頸部高挺,身體修長,長尾如刺,尾尖上卷,背鰭 突起延至尾部。右腿前伸,左腿後蹬作行進狀,四肢上部及龍 身飾有鱗片。銅走龍體態輕盈矯捷,身形修長舒展,如行雲流 水,四肢壯碩剛勁,極富張力,每個關節都有飾物凸起,爪子 鋒利,尾巴優雅彎曲。該龍覆蓋著自然的綠色銅綠,耳朵和嘴 巴內仍然保存有原來朱紅色顏料。

龍在中國自古是為吉祥與神聖的存在,乃正氣浩然、至大 至剛之神獸,可以興風致雨,具有無邊的威力,龍又被認為是 皇權天子的象徵,中國神話更視青龍與白虎、朱雀、玄武四靈 獸為四象,各鎮東、西、南、北一方,分掌四季,以保福泰永 年。此龍量罕質精,製作工藝上乘,流傳有緒,為存世稀珍, 其強大的藝術生命力完美地呈現了龍在中國文化中的特殊地 位。

Provenance

Eskenazi Limited, London Norman A. Kurland, U.S.A.

Exhibited

London, 1996, Eskenazi Limited Princeton, New Jersey, 1996, Princeton University Art Museum

Published

Eskenazi Limited, Sculpture and Ornament in Early Chinese Art, London, 1996, number 21.

Similar Examples

Michael Sullivan, The Arts of China, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1999, page 117, figure 6.27, for a smaller striding dragon in the Fogg Art Museum.

Wang Changqi et al., “Jieshao Xi’anshi cang zhengui wenwu”, (“The precious Historical Relics Collected in the City of Xi’an”), Kaogu yu wenwu, 1989, number 5, plate 2, figure 5, for a smaller gilt-bronze striding dragon attributed to the Tang period.

Jean-Pierre Dubosc, Mostra d’Arte Cinese (Exhibition of Chinese Art), Venice, 1954, page 55, number 159 for a smaller gilt-bronze example; also, Christie’s London, The Frederick M. Mayer Collection of Chinese Art, 24–25 June 1974, number 143; also, Annette L. Juliano, Art of the Six Dynasties, Centuries of Change and Innovation, New York, 1975, number 37.

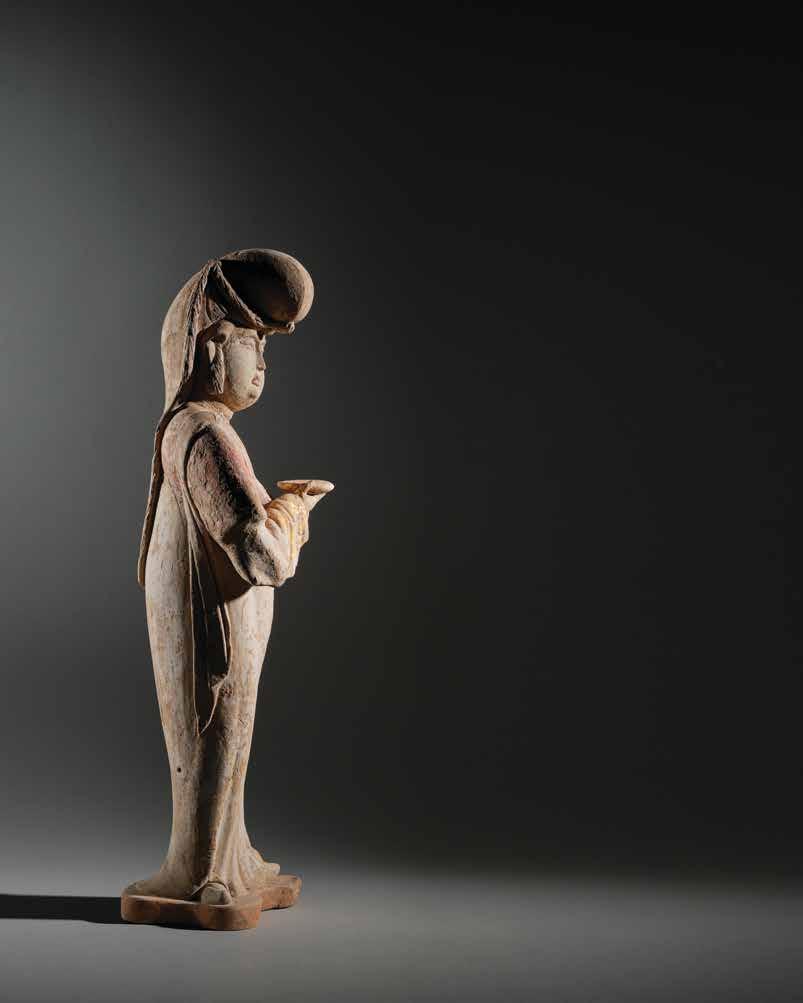

Painted pottery figurine of a female musician

Western Han dynasty (206 BC–9 AD)

h: 40 cm

西漢 彩繪陶樂唱俑

This Western Han dynasty figurine portrays a female musician in a kneeling pose, adorned in a deep robe with a rightover-left collar. Her hands, clasped within pleated sleeves, partially shield her face as her upper body leans slightly forward, radiating a serene and graceful aura. Her hairstyle is elegantly parted at the forehead, with long hair gathered into a gently drooping bun at the back with strands flowing freely beneath. The face, highlighted by a delicate nose, exudes a subtle charm.

西漢塑衣式跽坐拱手樂唱俑,女俑髮式前額中分,長髮後 攏於項背挽成垂髻,髻下青絲披垂,身穿右衽交領曲裙深衣, 席地跽坐,上身微傾,雙手拱於袖中,並以長袖微微遮面, 朱唇微啓歌唱,其面龐豐潤,鼻樑小巧,溫柔俊美。

Provenance

American private collection

On loan to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2007–2022, L2007.136.2

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture, Robert D. Jacobsen, PhD, p. 42–45.

Similar Example

A similar example is found in the Eskenazi Limited catalogue, Ceramic sculpture from Han and Tang China, 1997, p. 20.

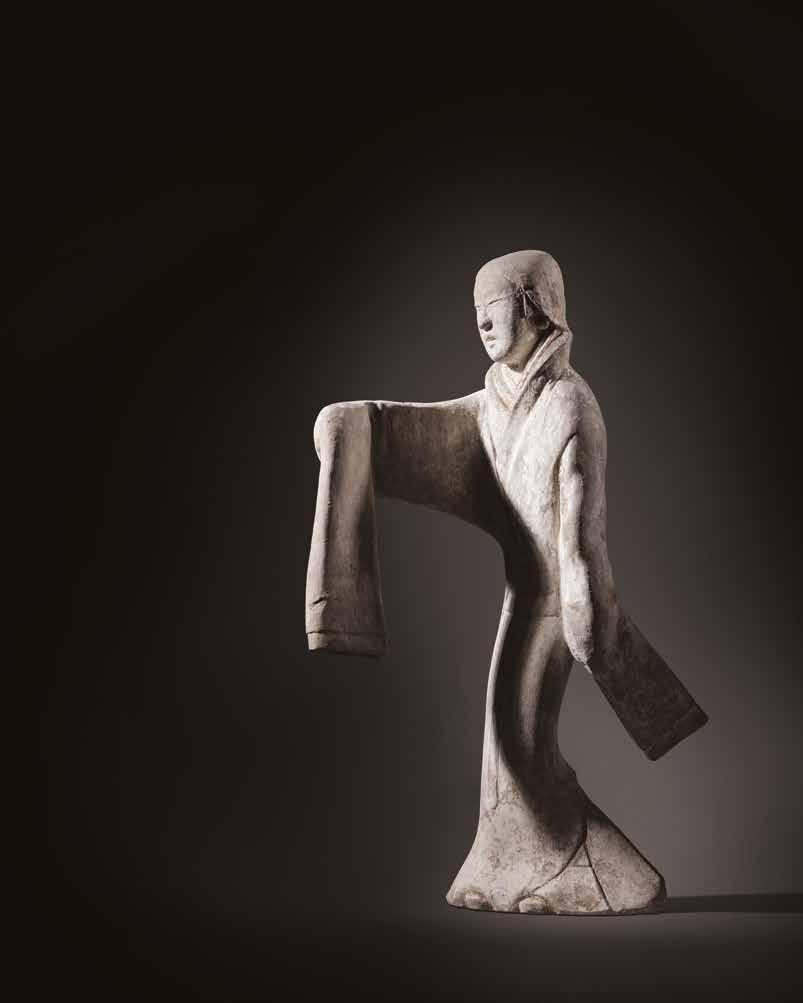

Painted pottery figurine of a female dancer

Western Han dynasty (206 BC–9 AD)

h: 57 cm

西漢 彩繪陶舞俑

Of delicate features and dressed in a wrap-style trailing robe with a curving front, the long-haired female dancer parts her lips possibly to sing. Her knees are slightly bent and her upper body leaning a little forward. While one arm is hanging down at her side, the other is raised forward to level with her shoulder. The flowing sleeves, lithe body, graceful posture and impassive face bring to mind the figurine’s early Western Han counterparts.

During the Han dynasty, which was blessed with power and prosperity, China witnessed ethnic groups mingling with one another and in turn a boom in both dance and music, which became integral to Han rites and rituals. Developed from the pre-Qin tradition that stressed realism and relevance of the time, Han dance and music further incorporated foreign cultural features to arrive at a distinct character of their own. They were performed during rituals, ceremonies and banquets to entertain gods and men alike. A dance typical of the time was the long-sleeve dance, which originated in the Chu state during the Warring States period and remained highly popular throughout the Han and well into the Wei–Jin period. Characterized by the Chu people’s flamboyance, it was commonly performed during court and clan banquets as well as religious rituals as a kind of social dance with dancers keeping themselves apart using their sleeves.

Unusually long by design, these sleeves of the Han costume served very much as extensions of the dancers’ arms for enhanced expressiveness and dynamism. As seen in surviving Han literature, discussions of dance and mhusic abounded at the time. In particular, Fu Yi dedicated a fu-rhapsody, namely “Wu Fu” or “Rhapsody on Dance”, to the art form. In it, dancing is described in relation to how the robes sway in the breeze, the long sleeves tangle and twine, and the dancers flit around the dance movements compared to bending, stretching, flying, walking, standing or falling; and the dancers’ minds discerned to be relaxed, wandering or contemplative. This poetic piece was followed by Zhang Heng’s work of the same title, which compares robe fronts to darting swallows and sleeves to swirling snow as the Han pursued longevity and eternity through dancing.

Few pottery dancer figurines have survived to this day. Painstakingly conceived and effected whether in shape, description or colouring, this splendid figurine before us manifests the music culture of the Han dynasty and is of great importance to the study of Western Han history, culture and art.

Provenance

American private collection

On loan to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2007–2022, L2007.136.1

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture, Robert D. Jacobsen, PhD, p. 42–45.

Similar Example

A similar example is found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

西漢 彩繪陶舞俑

曲裾深衣陶舞俑,舞女長髮下垂,眉目清秀,臉龐含蓄嘴 微開如在歌唱,身著曳地長袍,腿部微微前屈,上體前傾,一 臂自然垂於體側,一臂平舉,長長的衣袖瀑布般垂落,體態 嬌柔,舞姿輕盈舒緩。舞俑神態典雅含蓄,造型瀟灑飄逸, 雲舒袖舞。

漢代經濟發達,國力強盛,各民族交往頻繁,樂舞藝術空 前繁榮,成為漢王朝禮樂體系的重要組成部分。漢代樂舞秉承 先秦樂舞寫實的風格和反映世風的特徵,還吸收了外來的文化 元素,形成了獨具特色的西漢樂舞藝術,在祭祀、禮儀、宴享 場景中,兼具娛人和娛神等功能。其中“長袖舞”亦稱“巾 舞”,是漢代比較典型的舞蹈之一,源於戰國時期的楚國,曾 風靡兩漢直至魏晉,體現了楚風的浪漫不羈和個性張揚。舞者 以袖隔之,以舞相屬,在宮廷、豪強大族的宴飲和祭祀活動中 廣為流行。舞者利用漢服特殊的長袖,延伸手臂的長度,增加 了肢體的表現力賦予了意境的抒情性,舞姿柔美又不失力量。

漢代歷史文獻中保存有大量有關音樂舞蹈的文字記載,甚 至出現東漢傅毅《舞賦》這樣討論舞蹈的專門作品。《舞賦》 描述了“羅衣從風,長袖交橫,駱驛飛散,颯擖合併”“若俯 若仰,若來若往……若翔若行,若悚若傾”的飄逸舞姿,和舞 者“舒意自廣,遊心無限,遠思長想”的內心境界;此後張衡 也撰《舞賦》描述長袖舞“裾似飛燕,袖如回雪”,水袖羅紗 翩然起舞,表達了漢人對長生和永恆的追求。

西漢陶長袖舞俑殊為少見,此跳舞俑造型生動傳神,體表 敷施彩繪,無論是舞者的舞姿、表情還是服飾細節,雕塑姿 態,都經過精心雕琢,展現出極高的藝術水準,是漢代樂教 文化的直觀反映,更是研究西漢歷史、文化、藝術等方面的 重要實物資料。另一例相似的西漢長袖舞俑見於美國紐約大 都會博物館。

Painted pottery ox

Northern Wei period (386–535)

h: 14 cm

北魏 彩繪陶牛

A finely crafted pottery figure of an ox, standing solidly on a rectangular base. This robust sculpture features a plump body, prominent hump, short tail, and projecting ears, all characteristic of the breed. The figure is further enhanced by an intricately detailed harness made of straps and roundels.

Provenance

American private collection

On loan to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2011–2024, L2011.61.3a

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture, Robert D. Jacobsen, PhD, p. 42–45.

Pair of painted pottery dogs

Northern Wei dynasty (386–535)

l: 18 cm and 20 cm

北魏 灰陶狗

A pair of painted grey earthenware recumbent dogs, meticulously crafted to resemble mastiffs, depicted in an alert yet relaxed pose. Each dog is shown lying with its front legs outstretched, floppy ears, and a slightly open mouth revealing two prominent front teeth. The pointed snout and finely incised lines accentuate the musculature. The tail curls to one side, while the rear left leg is tucked underneath. Traces of white pigment highlight the details of these lifelike sculptures.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

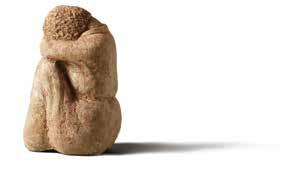

Fine earthenware youth figure

Northern Wei period (386–535)

h: 10 cm

北魏 彩繪陶童俑

An exceptional earthenware piece depicting a youth curled up in a naturalistic form, either sleeping or ruminating (I’ll exclude the option of weeping, as we’re too tough for that). This figure, physically vulnerable yet aesthetically powerful, is seated with his knees drawn up, his left arm resting above his right arm and knees, supporting his drooped head and concealing his face, which accentuates his distinctive curly hair. He is clad in a belted tunic and loose trousers, with only the tips of his shoes visible.

Provenance

American private collection

On loan to Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2005–2022, L2005.56.12

Published Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture, Robert D. Jacobsen, PhD, p. 190–191. 21

Exquisite painted dancers and musicians

Tang dynasty (618–907)

h: 21 cm

唐 彩繪陶女跳舞樂伎俑一組

Naturalistic and graceful, the figures exhibit youthful expressions, with vermilion lips and dark hair styled into two elegant topknots. The dancers are adorned in sophisticated red robes featuring a high bodice and long, flowing sleeves, embellished with black stripes arranged in triple bands that cascade down to the base. They are depicted half-kneeling and leaning forward, captured mid-dance in a dynamic, flying motion, embodying a sense of fluidity and grace. In contrast, the seated musicians are focused on their instruments— one holding a lute (pipa) and the other a bowed harp (konghou 箜篌). Provenance Sotheby’s New

Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David

12件。其中兩件是舞俑,其餘是樂俑,頭梳 雙髻,粉面朱唇,身著半臂衫,長裙鋪地,表情專注,共同 組成一場別開生面的小型宴樂演出。在樂者的伴奏下,兩名 舞者翩翩起舞,她們穿著精緻的紅色長袍,上面有緊身胸衣 和飄逸的長袖,飾有黑色條紋排列成三帶,向下層疊到基部。 身體略略前傾,其舞姿則一臂上舉,一臂下伸,腰肢纖細, 體態婀娜,體現出一種流暢和優雅的感覺。相比之下,坐著 的音樂家們則專注於手持的樂器,有琵琶、箜篌、排簫和笙 等。

一件文物背後,是一個王朝的縮影。唐代舞蹈與音樂結合 緊密,特別是從絲路傳來的少數民族樂舞,更是深受皇親貴 族的喜愛。唐代樂舞氣勢磅礴,場面壯觀,集詩詞歌賦於吹 奏彈唱,融鐘鼓琴瑟於輕歌曼舞,著名詩人白居易的《霓裳 羽衣》即為盛唐樂舞的代表。

此組俑胎質細膩堅硬,粉白色胎體,雖經千年時光,俑身

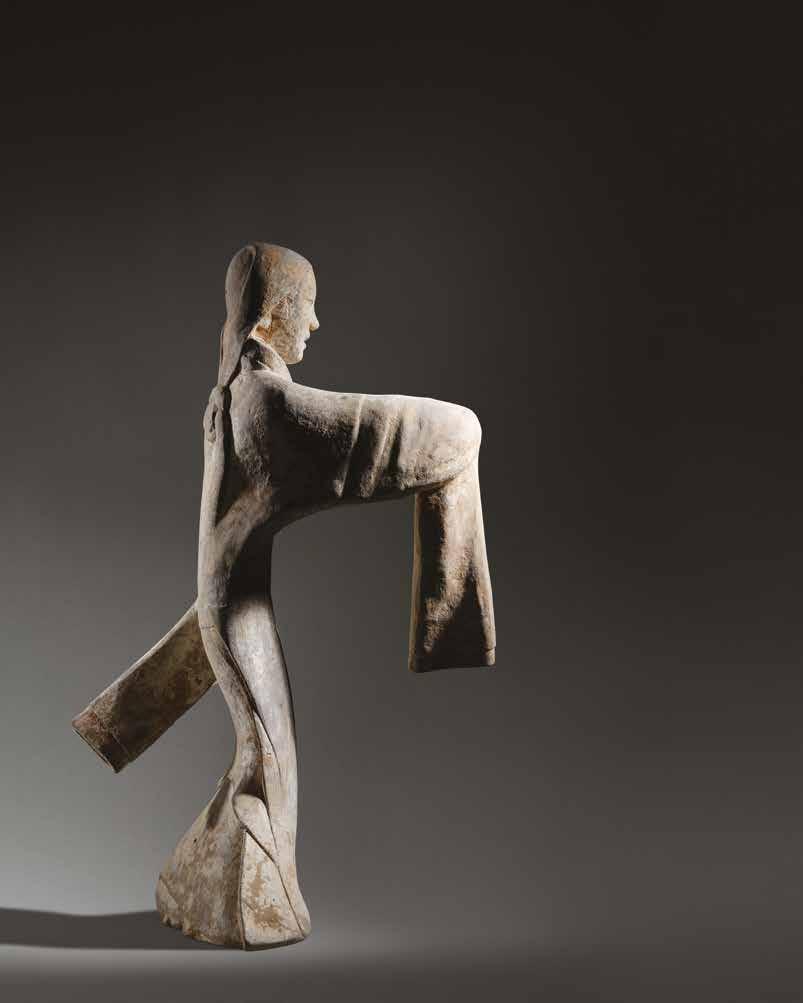

Court lady holding a plate

Tang dynasty (618–907)

h: 45 cm

唐 彩繪灰陶仕女俑

This rare grey pottery figure of a court lady from the High Tang period is crafted from solid grey clay. The artisan skillfully sculpted the piece, fired it at a high temperature, and then applied coloured pigments. The figure stands upright, her head held high, with her hair arranged under a cloth headdress. Her narrow, slit eyes gaze forward, and her highbridged nose and small mouth are accentuated by painted red lips. Her lively expression and distinctive hairstyle frame her round face and full cheeks, together exuding an elegance and beauty unmatched by others. She stands proudly in a fulllength robe, its drapery cascading to the ground in fluid lines reminiscent of spontaneous ink brushstrokes, with just the tips of her shoes peeking out. Her arms, beneath loose-fitting sleeves embellished with gilt, are raised to her chest, with a plate held in her hands.

Every detail—from her hairstyle and clothing to her posture and expression—is meticulously crafted, making this piece a rare and quintessential example of Tang dynasty pottery figurines. High Tang women admired a fuller, healthier beauty and a confident demeanour, an ideal rarely seen in other periods. She perfectly embodies the dignified aesthetics of “elaborate coiffure and flowing robes” and a “full and plump physique.” This aesthetic trend persisted through the late Tang and Five Dynasties periods. Such grey pottery figurines of court ladies are exceptionally rare.

此件罕見盛唐灰陶仕女俑,實心灰胎,工匠以灰陶雕刻, 高溫燒制再施以彩繪,女俑昂首端立,長目小口,目光溫和, 神態靈活生動,盡顯雍容嫻雅之美。其髪式較為特別,烘托 出滿月般豐潤的面龐。身體微傾站定,雙臂寬袖抬於胸前, 身著寬鬆長裙,領口較低,衣紋流暢飄逸,裙擺曳地,如潑 墨簡筆的瀟灑自在,鞋尖微露。女俑造型比例準確,以額寬、 臉圓、豐滿、自然為特徵,其衣著亦華麗典雅,具有典型的 盛唐貴族人物風格,充分表現「大髻寬衣」、「豐厚為體」 的端莊形象,髮型、服飾、體態、神情、動作更是各盡其妙, 乃盛唐仕女俑的珍品範本。盛唐女子崇尚豐腴之美,健康自信 的神采,為其它時期所罕見,其風氣直到晚唐、五代仍不衰。 此類灰陶仕女俑特別罕見,另一例見於日本美秀美術館。

Provenance

American private collection

On loan to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2005–2024, L2005.26.5

Published

Celestial Horses & Long Sleeve Dancers: The David W. Dewey Collection of Ancient Chinese Tomb Sculpture, Robert D. Jacobsen, PhD, p. 190–191.

Similar Example

A similar example is currently housed in the Miho Museum, Japan.

Fine court lady

Tang dynasty (618–907)

h: 39 cm

唐 彩繪仕女俑

Standing elegantly, this plump court lady is a stunning depiction of timeless beauty. Her elaborate coiffure is meticulously styled, complementing her graceful posture. She wears upturned, pointed shoes, while her hands are clasped at the waist, discreetly concealed within her long sleeves. This piece captures the refined elegance and sophistication of courtly life.

Hong Kong private collection

British private collection

Provenance

d: 18 cm

唐 白瓷鉢

Provenance

Japanese private collection

White glazed bowl

Tang dynasty (618–907)

Black glazed pillow with leaf design

Late Tang dynasty (618–907)

l: 17 cm

h: 9.2 cm

晚唐 黑釉葉文枕

Provenance

Idemitsu Museum of Arts collection

出光美術館舊藏

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo

繭山龍泉堂

Exhibited

Tang Pottery And Porcelain, Nezu Institute of Fine Arts, Tokyo, 1988, No. 32

根津美術館「唐磁 白磁•青磁•三彩」1988年, 32號

Published

Tsuguo Mikami, Chugoku Kodai, Vol. 5 from the series, Toki Koza, 1982, pl. 143.

Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Chinese Ceramics in The Idemitsu Collection, 1987, pl. 64.

Hiroko Nishida & Sarah Sato, Temmoku, Vol. 6 from the series, Heibonsha’s Chinese Ceramics, Heibonsha, 1999, pl. 18.

三上次男「陶器講座 第5卷 中国I 古代」1982年, 図版143

出光美術館「出光美術館蔵品図録 中国陶磁」1987年, 図版64

西出宏子, 佐藤サアラ「平凡社版 中国の陶磁6 天目」1999

年, 図版18

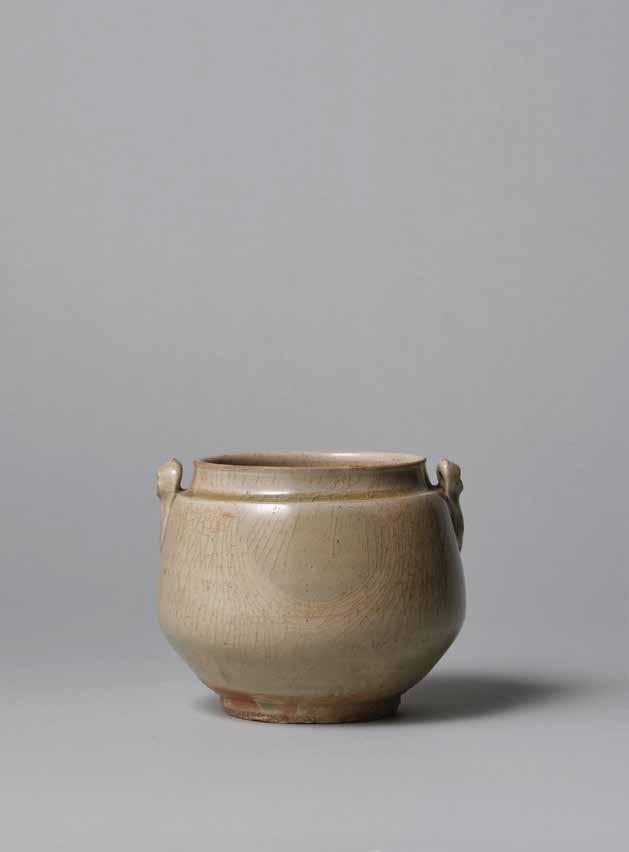

Fine celadon jar with two lugs

Late Tang dynasty (618–907)

h: 8.7 cm

w: 10.5 cm

晚唐 越州青瓷雙耳壺

Provenance

G. F. Giaquili Ferrini collection Mayuyama & Co., Ltd., Tokyo

繭山龍泉堂

Yaozhou ware celadon bowl

Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

d: 13.5 cm

北宋 耀州窯青磁碗

Provenance

Old Japanese collection

Kusaka Shogado, Tokyo

日下尚雅堂, 東京

Similar Example

Hasebe Gakuji, “On the Celadon Bowl Called Dong Ware,” MUSEUM, vol. 426, 1986, p. 29, pl. 3.

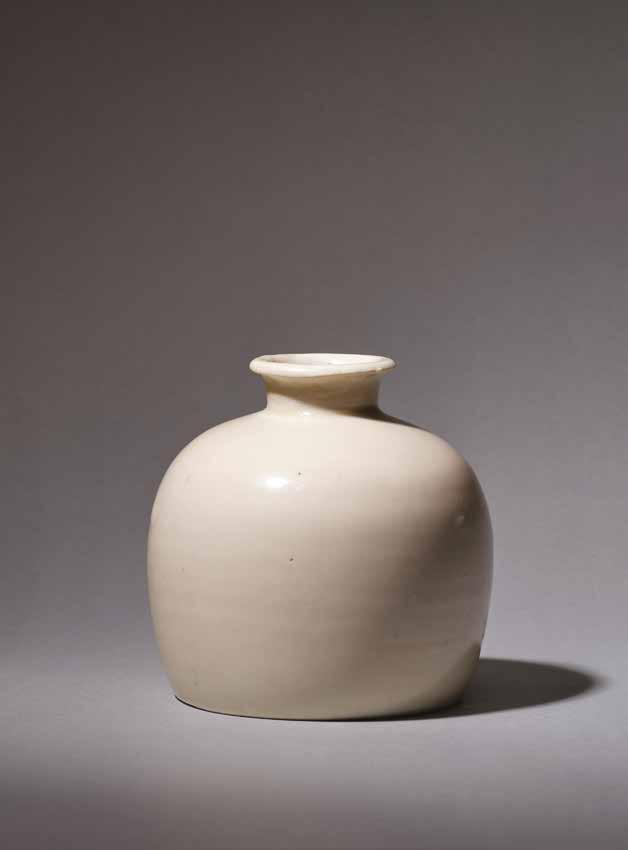

Rare ding ware “tulu” vase

Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

h: 10.6 cm

北宋 定窑白釉嘟噜瓶

The jar features a compact, domed body rising from a flat base to gracefully rounded shoulders, transitioning into a narrow neck that gently flares out towards a lipped rim. It is finished with a translucent glaze tinged with ivory, while the unglazed base reveals the pure white ceramic body.

Provenance

Sotheby’s New York, 21 September 2021, lot 182

紐約蘇富比,2021年9月21日

Fine Ding ware foliate rim bowl

Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

d: 13.6 cm

北宋 定窯白釉花口盌

The bowl is elegantly crafted with thin, rounded sides that flare gently to a lobed rim. It is covered in a lustrous pale ivorytoned glaze, both inside and out, with the base left unglazed to reveal the fine, white body beneath.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Christie’s Hong Kong, 29 November 2022, lot 2906

佳士得香港,2022年11月29日 編號2906

Fine Ding ware white porcelain vase, yuhuchunping

Northern Song/Jin dynasties (960–1234)

h: 21 cm

北宋/金 定窯白釉玉壺春瓶

The elegantly potted vase, or yuhuchunping, features a tapering ovoid body that rises to a tall, slender neck and a flared mouth rim. It is covered in a pale ivory-white glaze that stops above the splayed foot.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Christie’s Hong Kong, 3 December 2021, lot 2973

香港私人收藏

佳士得香港,2021年12月3日 編號2973

Ding ware “peony scroll” bowl

Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

金 定窯白釉模印纏枝牡丹紋盌

d: 15 cm

Of conical form rising to a wide mouth from a small base, covered overall in an ivory-white glaze. The moulded ornament inside includes a rosette with spiral petals at the centre and a broad band of peony scrolls along the side.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Exceptional Jun ware purple-splashed “bubble” bowl

Song/Jin dynasties (960–1234)

d: 6.2 cm

宋/金 鈞窰紫斑盌

Exceptionally potted with steep, rounded sides that rise from a short foot to a gently incurved rim, this piece is coated in a sky-blue glaze, leaving the foot exposed. The glaze fades to a mottled mushroom tone at the rim and pools just above the foot, while the lustrous surface is highlighted with vibrant, variegated purple splashes.

Provenance

Mayuyama & Co., Ltd, Japan

日本繭山龍泉堂

Old Swedish collection

Old Japanese collection

Exquisite Qingbai dragon/loong ewer and cover

Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province Song dynasty (960–1279)

H: 26 cm

宋 景德鎮青白釉雕龍執壺

Finely potted, this is an extremely rare white-glazed Qingbai ewer that boasts a plump, translucent globular body with an icy blue-tinged hue. Qingbai literally means “bluish white”. It features a heavy splayed foot and a plain cylindrical neck, concealed under a fitted cover upon which rests a few thin, horizontal discs reminiscent, to some degree, of chatras— one of the eight emblems in Buddhism. The use of pure white kaolin clay contributes to its unique elegance and timeless beauty, coming closest to pure porcelain among the variety of notable wares manufactured during the renaissance-like Song period. The sides are adorned with a spout, intricately modelled in the form of a three-clawed dragon with protruding eyes, a long snout, and an open mouth as though roaring and belching plumes of smoke. Two horns point back toward its sinuous body, forming a high-arched handle.

Qingbai was praised as being “meticulously beautiful”. The famous Southern Song (AD1127–1279) historian Jiang Qi 蒋祈 in his Tao Ji (Ceramic Records) described the Qingbai wares produced in Jingdezhen as “flawless, exquisite and pure white…being known as Jade of Rao”. Raozhou was the name of the region in which the Jingdezhen kilns were located.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Similar Example

Ye Zhemin (2011), 中国陶瓷史Zhong Guo Tao Ci Shi (History of Chinese Pottery and Porcelain), p. 312 – 3.

Fine carved Qingbai “boys” bowl

Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)

d: 21.7 cm

南宋 青白釉刻嬰戲紋盌

Beautifully potted in a conical shape, this piece showcases a finely carved interior featuring a pair of boys and a pair of leaves arranged on opposite sides to form a tidy square. The design is set against a feathery scroll and wave background, and the entire piece is covered in a pale icy blue-green glaze. The rim is elegantly wrapped with a graceful silver band. Qingbai bowls featuring the popular “boys” motif are wellrepresented in major museums and private collections. Although the present bowl is slightly smaller than typical examples, giving it a more delicate appearance, it aligns with this admired design. For comparison, consider the following:

A larger bowl with boys among vines is illustrated in Basil Gray’s Sung Porcelain and Stoneware (London, 1984, pl. 124) and can be found in the Seattle Art Museum.

Two examples excavated from the Hutian kiln site in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, are published in Chai Kiln and Hutian Kiln (Nanning, 2004, pp. 94 and 95).

A fourth bowl is in the Avery Brundage Collection at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and illustrated in Stacey Pierson (ed.), Qingbai Ware: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties (London, 2002, pl. 7).

A bowl of this design, excavated from a tomb in Yihuang County, Jiangxi province, dated to 1201 AD, is preserved in the Jiangxi Provincial Museum and illustrated in Peng Shifan (ed.), Dated Qingbai Wares of the Song and Yuan Dynasties (Hong Kong, 1998, pl. 65). Another example is in the Palace Museum, Beijing, as published in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Porcelain of the Song Dynasty (II) (Hong Kong, 1996, pl. 182).

Provenance

Sotheby’s New York, 19 March 2007, lot 406

紐約蘇富比

Qingbai floral-lobed cup and stand

Song dynasty (960–1279)

宋 青白釉葵瓣盃配盞托

Exquisitely crafted, this cup features elegantly lobed sides that rise from a short pedestal foot to an everted rim, notched into six petal-like lobes, enhancing its delicate appearance. The cup stands on a circular foot and is accompanied by a broad, slightly elevated stand. Both pieces are finished with a translucent pale blue “qingbai” glaze, with the exception of the base.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Rare Qingbai tea caddy

Song dynasty (960–1279)

h: 9 cm

宋 青白釉茶罐

A fine porcelain of cylindrical form rising from a recessed base to a stepped, incurved mouth, covered in a pale bluish “qingbai” glaze. The straight-sided cover is topped with an unusual double-pointed finial.

Hong Kong private collection

Provenance

Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

h: 9 cm

北宋 黑釉小茶罐

Provenance

Japanese private collection

Black glazed tea caddy

Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

h: 9 cm

北宋 白釉小茶罐

Provenance

Japanese private collection

White glazed tea caddy

Black-glazed bowl with white rim decoration

Northern Song dynasty (960–1127)

d. 12 cm

北宋 黑釉白覆輪柳斗鉢

White rim decoration is commonly seen on teacups, but this particular piece, shaped like a “Liudou” bowl, is exceptionally rare. It likely has connections to religious activities of the time, as black and white were symbolic colours representing monks and laypeople in Buddhism. The bowl’s simple yet sturdy design, combined with the black and white glaze, exudes a unique sense of Zen.

The creation of such a distinct black-and-white vessel involved a complex process. First, the entire piece was coated with black glaze. Then, the black glaze around the rim was carefully scraped off and replaced with a layer of white slip. Finally, a transparent glaze was applied over the entire piece before it was fired in the kiln.

白覆輪即鑲邊之意,一般通體施加黑釉,其器物以製作工 藝的複雜性、黑白釉的對比以及精美細膩的表面質感而聞名, 是極具視覺衝擊力的裝飾方法,體現了宋代陶瓷的極簡之美。

白覆輪多見於盞類,此件為柳鬥鉢造型,結合了白覆輪和柳 鬥紋兩種裝飾手法,特為罕見,應當與當時的宗教活動有關 聯。在佛教中,黑白是僧、俗指代,鉢式造型搭配黑白釉色, 造型樸實,穩重,別具禪意。白覆輪器物製作工藝繁覆,先 在拉好的坯體上通體施加黑釉,刮除口沿的一圈黑釉,再刷一 層白色化妝土,最後施加透明釉,入窯燒制而成。

Provenance Hong Kong private collection

Fine marbled bowl

Northern Song/Jin dynasties (960–1234)

d: 13 cm

北宋/金 絞胎盌

The bowl features a rounded shape, meticulously crafted from marbled dark-brown and cream-colored clay. The clay is artfully twisted into irregular swirls, forming a distinctive pattern that is enhanced by its compression into uneven rows. These intricate textures and colors are preserved under a lustrous clear glaze, giving the bowl a striking and unique appearance.

Provenance

J. J. Lally & Co., New York, no. 2925.

藍理捷, 紐約, 編號2925

Christie’s New York, 23 March 2023, lot 840

紐約佳士得 2023年3月23日 編號840

Small “oil spot” black glazed tea bowl

Song/Jin dynasty (960–1234)

d: 9 cm

宋/金 懷仁窑黑釉油滴小盞

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Jizhou “papercut” teabowl with running deer decoration

Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)

d: 12.5 cm

宋 吉州剪紙貼花鹿紋碗

This bowl has steep, flaring sides that gracefully rise to a narrow, delicate rim. The interior is adorned with a rich, variegated tan-brown glaze that exhibits a warm, earthy tone. The glaze is highlighted by three evenly spaced dark brown silhouettes of running deer, each meticulously rendered with outstretched legs, all facing forward in full stride, creating a dynamic sense of motion and pursuit. The glaze deepens in colour towards the rim, creating a subtle gradient that accentuates the bowl’s curvature. The exterior is equally wellcrafted, with a smooth surface that complements the intricate design within, highlighting the bowl as a harmonious blend of beauty and utility.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Similar Example

J. J. Lally & Co., New York, Early Chinese Ceramic, An American Private Collection, Spring 2005, p. 27.

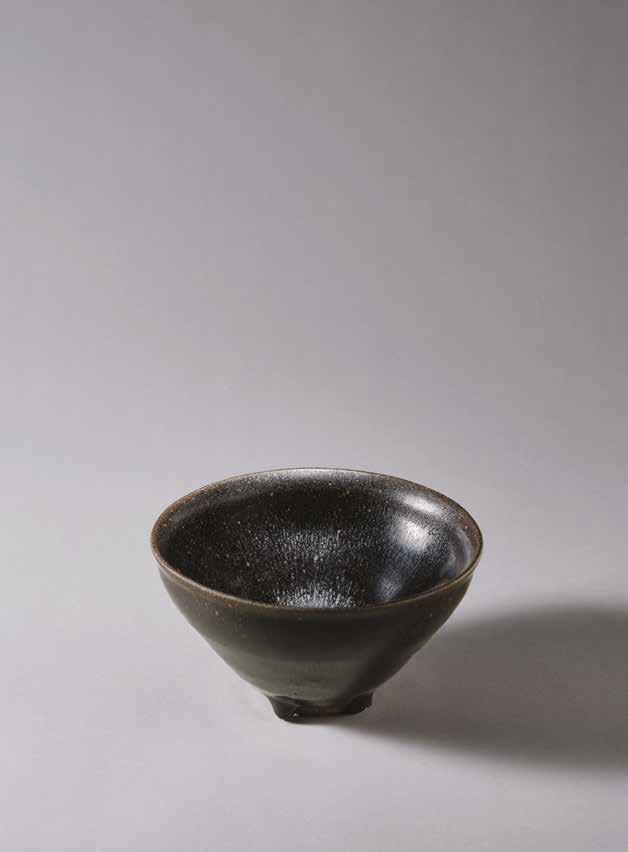

Rare Jian “oil spot” tenmoku bowl

Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)

d: 12.5 cm

南宋 建窰「油滴天目」茶盞

An exceptional piece of art in a deep conical form, featuring a groove below the lip and a shallow, straight foot. Its glossy surface is coated in a thick, lustrous black glaze, with the interior accentuated by fine, irregular silvery “oil-spots” against the iridescent dark background, creating a striking contrast with the white froth of whipped tea.

Provenance

Hong Kong private collection

Longquan guan-type celadon vase

Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)

h: 14.3 cm

南宋 龍泉仿官窯瓶

The pear-shaped body rises from a thin, straight foot ring to a wide, cylindrical neck topped with a cup-shaped mouth rim. The bulbous body is covered in a crackled pale bluish-green celadon glaze, which extends across the surface, leaving the unglazed foot ring to reveal the dark grey body beneath.

Provenance

American private collection

Eric Zetterquist, New York, 2014

Christie’s Hong Kong, 3 December 2021, lot 2968

佳士得香港,2021年12月3日 編號2968

Similar Example

For a similar example, see Celadons from Longquan Kilns, Beijing, 1998, pl. 109. Another comparable piece is published in Chinese Ceramics from the Carl Kempe Collection, pl. 97.

Rare Longquan celadon glazed melon-shaped teapot

Southern Song/Yuan dynasty (1127–1368)

南宋 /元 龍泉窰青釉瓜棱式壺

L: 13.3 cm

Provenance

Collection of George Eumorfopoulos (1863–1939)

Sotheby’s London, 28 May 1940, lot 91

Bluett & Sons Ltd., London

Collection of Charles Russell (1866–1960)

Sotheby’s London, 12 July 1960, lot 129

William Clayton Ltd., London, 31 December 1971

Collection of Dr Kenneth Lawley (1937–2023)

喬治・尤莫夫泊洛斯(1863–1939年)收藏

倫敦蘇富比1940年5月28日,編號91

Bluett & Sons Ltd.,倫敦

Charles Russell(1866–1960年)收藏

倫敦蘇富比1960年7月12日,編號129

William Clayton Ltd.,倫敦,1971年12月31日

Kenneth Lawley(1937–2023年)博士收藏

Published

R.L. Hobson, The Catalogue of the George Eumorfopoulos Collection of Chinese, Corean, and Persian Pottery and Porcelain, vol II, London, 1925–28, pl. 32.

霍布森,《The Catalogue of the George Eumorfopoulos

Collection of Chinese, Corean, and Persian Pottery and Porcelain, vol II》,倫敦,1925至28年,圖版32

Exhibited

Kinesiska Utsallningen, Stockholm, 1914, cat. no. 325/216

Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 1937, cat. no. 454

東方博物館,瑞典,1914年,編號325/216

橘園美術館,巴黎,1937年,編號454

Cizhou ware white glazed Meiping with calligraphy “Shi”

Song/Jin dynasties (960–1234)

h: 40 cm

宋/金 磁州窯白釉“士"字梅瓶

Provenance

Japanese private collection

Lam & Co UK

4 Mason’s Yard, London, SW1Y 6BU

Email: gallery@lamcouk.com www.lamcouk.com

Lam & Co Antiquities

2/F 151 Hollywood Road, Central, Hong Kong

Email: chrisantiquities@gmail.com

Info: gallery@lamcoantiquities.com www.lamcoantiquities.com

“Art

is chaos taking shape.”

—Pablo Picasso