Meriem Bennani

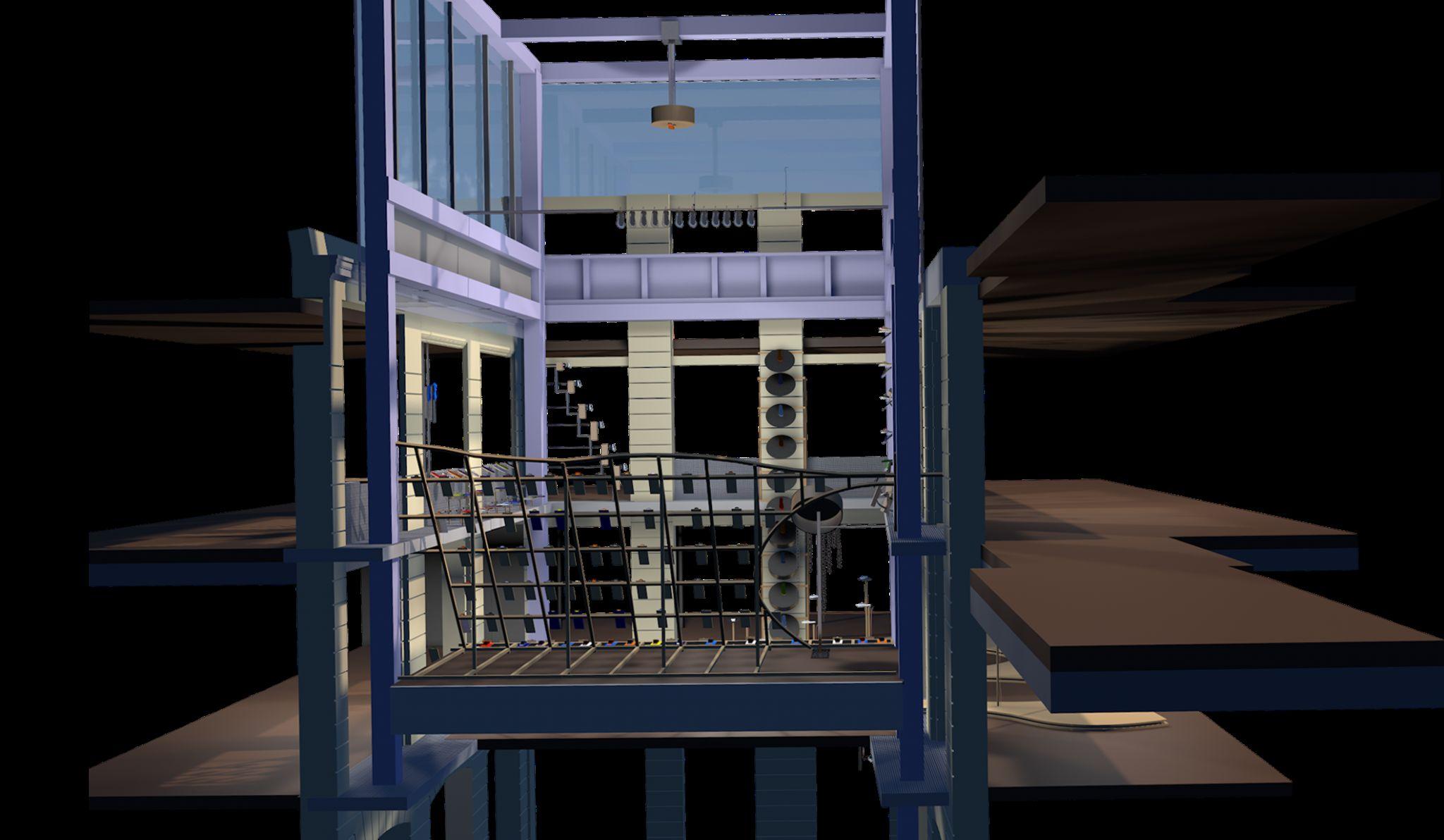

Avec Sole crushing, l’artiste Meriem Bennani propose une installation qui explore le vivre ensemble et la place de l’individu dans la collectivité. L’œuvre qui se déploie sur toute la hauteur de la Fondation, met en scène près de 200 tongs animées par un système pneumatique et suit une partition composée en collaboration avec le musicien Reda Senhaji (aka Cheb Runner).

Ces tongs incarnent une multitude de personnalités et évoquent les instants de communion où les rythmes des pas, des chants et des revendications politiques fédèrent les corps, à l’image d’une manifestation, d’un stade de football ou d’une cérémonie musicale. Fascinée par ces énergies collectives contagieuses, l’artiste s’inspire également de la dakka marrakchia, un rituel marocain dans lequel les participant·e·s jouent de la musique jusqu’à atteindre un sommet d'intensité spirituelle. Elle convoque aussi la notion de duende, cette force mystérieuse décrite par le poète espagnol Federico García Lorca dans les années 1930 pour qualifier la fougue qui s’empare des corps des danseur·euse·s de flamenco et son effet sur les spectateur·ice·s.

Le titre joue sur l’expression soul-crushing qui en anglais désigne une activité abrutissante, « écrasante pour l’âme ». Remplaçant le mot « soul » (âme) par « sole » (semelle) ce jeu de mot se réfère aux sandales qui battent la mesure et s’unissent en rythme avec une puissance sonore parfois écrasante.

Présentée initialement à la Fondazione Prada à Milan en 2024, Sole crushing a été entièrement réadaptée à Lafayette Anticipations avec de nouveaux instruments et une nouvelle composition musicale. Meriem Bennani invite les visiteur·euse·s à déambuler dans les espaces et vivre une expérience imaginée comme un instant de liesse ou de soulèvement.

With Sole crushing, the artist Meriem Bennani proposes an installation that explores the notion of being together and the individual’s place in the community. Unfolding across the full height of the Foundation, the work stages some 200 flip-flops that are animated by a pneumatic system, performing a score composed in collaboration with the musician Reda Senhaji (aka Cheb Runner).

These flip-flops embody a multitude of characters and evoke collective moments where bodies are united by the rhythms of footsteps, songs, or political uprisings —whether at a protest, football stadium, or musical ceremonies. Fascinated by such contagious collective energies, the artist takes further cues from dakka marrakchia, a Moroccan ritual in which participants play music while reaching a peak of spiritual intensity. She likewise refers to the notion of duende: a mysterious force, described by the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca in the 1930s, that seizes the bodies of flamenco dancers, with a concomitant hold on their spectators.

The work’s title plays off the expression “soulcrushing” with the materiality of the sandals’ soles, which both keep time and rhythmically sync up with what can become an overwhelming sonic power.

First exhibited at the Fondazione Prada in Milan in 2024–25, Sole crushing has been completely readapted for Lafayette Anticipations with new instruments and a new musical composition composition. Meriem Bennani invites visitors to wander through the space, absorbing an experience of collective joy or uprising.

pas de penser que si je réussissais à investir un espace si grand, si intimidant et si beau, à partir de quelque chose d’aussi simple qu’une tong, qui se trouve tout en bas de la chaîne de production de la mode, ça représenterait un challenge intéressant. À nouveau, c’était juste une intuition. Puis je me suis dit qu’une tong n’était rien mais que mille tongs pourraient me permettre de produire quelque chose qui serait presque émotionnel. Si elles se mettaient à taper du pied et à faire trembler le sol, ça pourrait devenir impressionnant ou créer quelque chose. Et dans mes expositions, ça m’intéresse toujours davantage de provoquer une sorte de réponse émotionnelle plutôt que des réponses intellectuelles. C’est plus intéressant pour moi de créer un sentiment qui va nous amener à parler d’autres choses que l’on va pouvoir intellectualiser. Et cette intuition d’utiliser beaucoup de tongs, je pense que ça me faisait penser à une foule. Puis j’ai réfléchi à tous ces moments où un grand nombre de gens se réunissent pour des raisons différentes. En plus, en termes d’« animation », les tongs sont faites en gomme et elles paraissent déjà être vraiment animées, dans un sens. Elles ont cette matière élastique et j’ai toujours été intéressée par les choses spongieuses qui se déforment. Elles sont polymorphes, elles peuvent changer de forme et devenir autre chose. D’une certaine façon, elles échappent à la rigidité de l’autorité et des règles. Ces caractéristiques ont alors commencé à faire sens par rapport à la thématique des gens qui se regroupent contre les régimes autoritaires.

[E.C.] Contrairement à la plupart de tes œuvres précédentes, Sole crushing semble dénuée de narration. Pourtant, chaque tong que tu as choisie, parfois accessoirisée, représente un personnage. Quelles histoires incarnent-elles ?

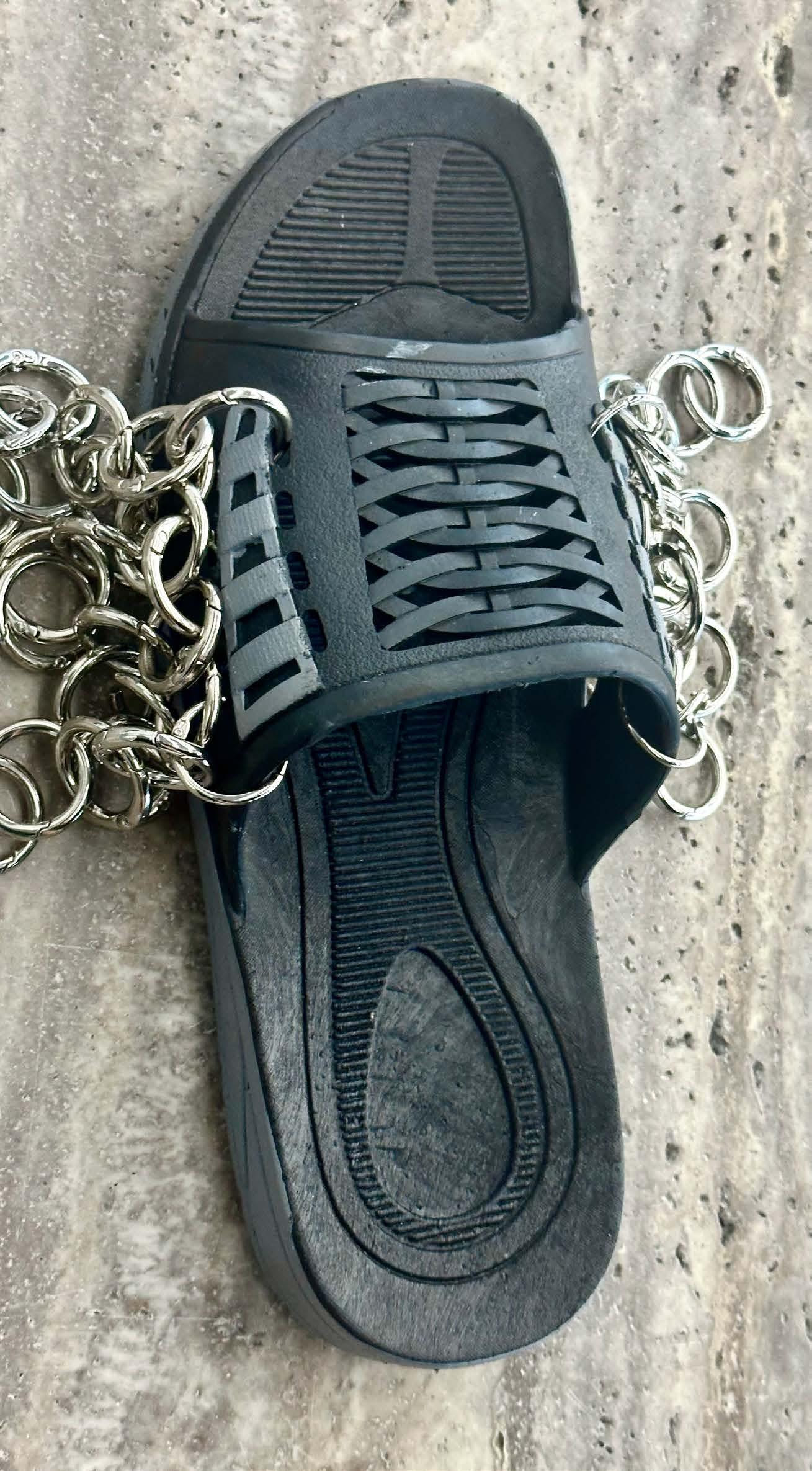

[M.B.] La mode regorge de signifiants, qu’ils soient des vecteurs du genre, de la classe sociale ou d’un style. Pour ce qui est des tongs, elles évoquent un certain style de vie : healthy, néolibéral, et Californien ; certaines sont vraiment

féminines. Je les ai en fait récupérées au Maroc, pas dans une boutique officielle mais dans un marché qui les vend en gros à celleux qui les revendent sur les marchés. Ce sont toutes des contrefaçons. Bref, même le design des tongs peut permettre d’imiter un certain style de vie ou une manière de se présenter aux autres. Mais ces tongs-là sont des imitations de cette imitation, parce qu’elles ressemblent à certaines marques. J’essaie parfois de prendre ça en considération quand je les dispose dans l’espace — celles qui devraient se trouver au centre, ou celles qui vont jouer la basse.

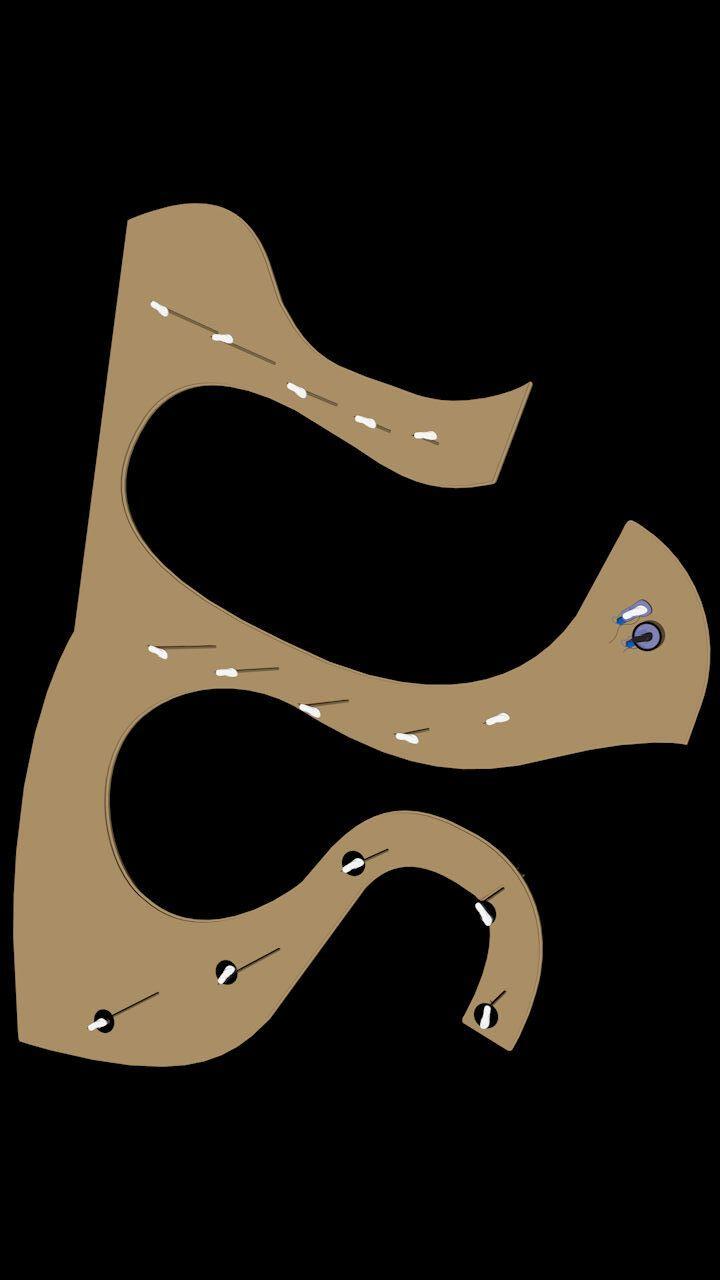

J’aime aussi l’idée qu’elles puissent toujours changer. L’un des aspects que je préfère dans la manière dont la dakka marrakchia fonctionne, en opposition au canon de l’orchestre symphonique européen dans lequel le chef d’orchestre guide le mouvement avec un pouvoir très centralisé, c’est qu’il y a quelqu’un qu’on appelle le maâlem, ce qui signifie « celui qui sait », qui est aussi un guide, il agit en fait comme un métronome. Je l’imagine plutôt comme un battement de cœur qu’un cerveau. Même si dans Sole crushing la structure possède un îlot central, j’aime l’idée qu’il y ait deux tongs qui servent presque de métronome, et qui lancent la structure d’appel et réponse de l’installation. J’ai aussi suspendu ce grand tambourin de basse au-dessus. Dans cet orchestre, les choses changent tout le temps. Celleux qui jouent les rôles principaux peuvent devenir secondaires dans d’autres circonstances. Dans Sole crushing, il y a aussi deux échelles que j’appelle « les militaires », parce qu’elles exécutent comme une parade. Peu importe leur apparence, mais leur musique et la façon dont elles s’organisent leur prêtent un élément presque fasciste.

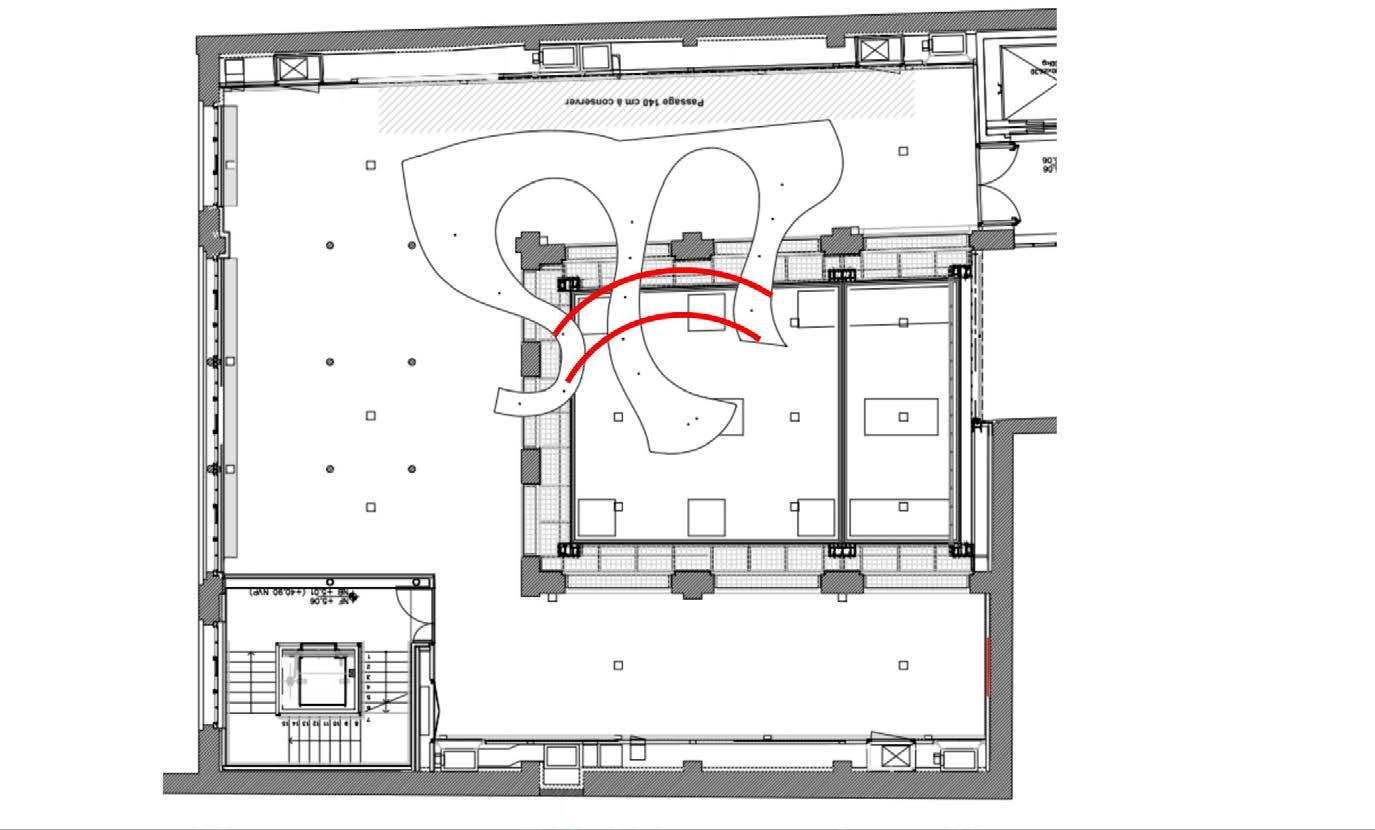

[E.C.] À Lafayette Anticipations tu as redessiné l’installation, plaçant le public au centre, dominé par la hauteur des instruments. Comment l’œuvre a-t-elle évolué pour cette seconde itération ?

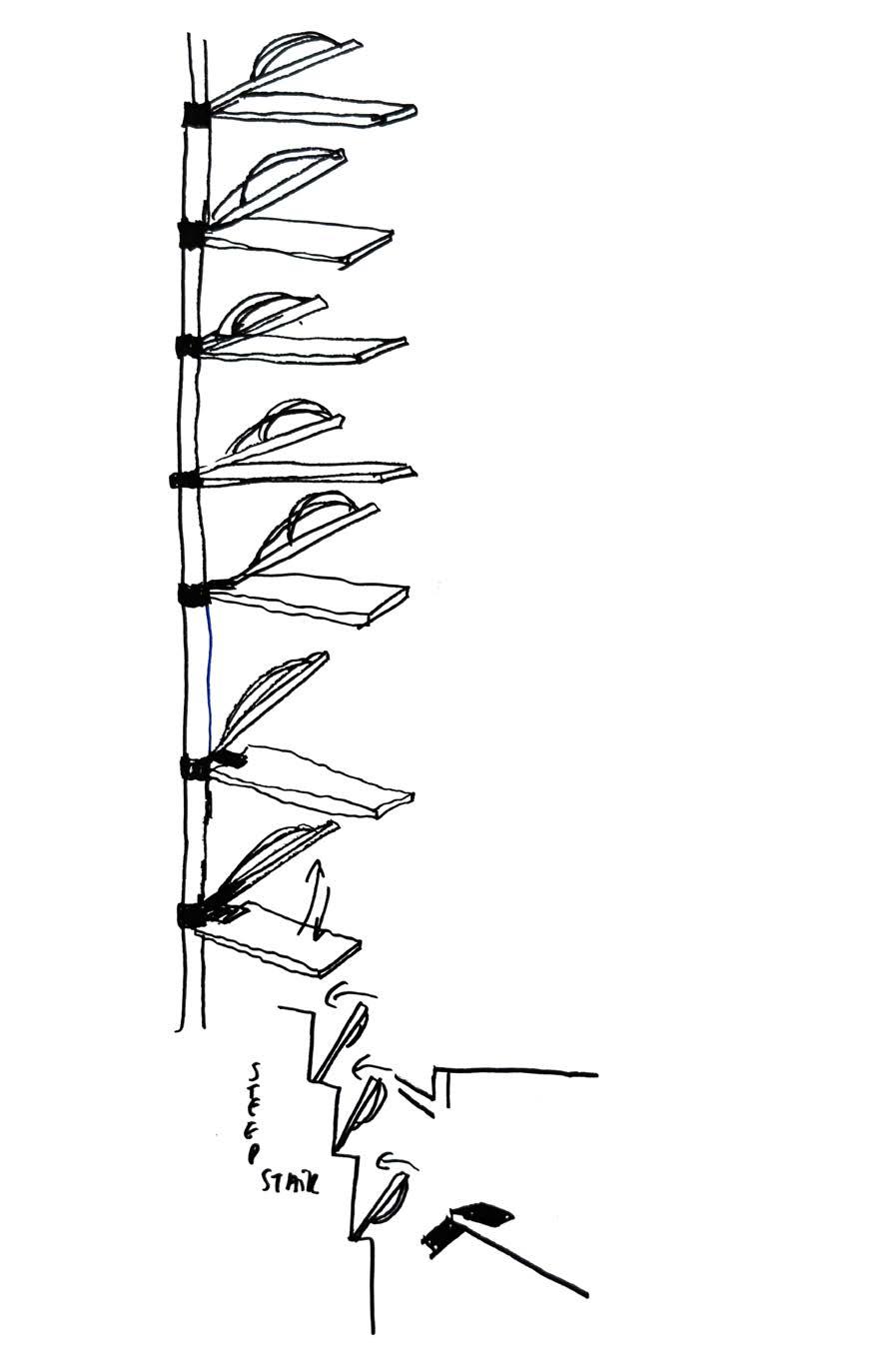

[M.B.] Je savais depuis le début que je voulais quelque chose de plus vertical, qui utilise aussi ce grand espace vide

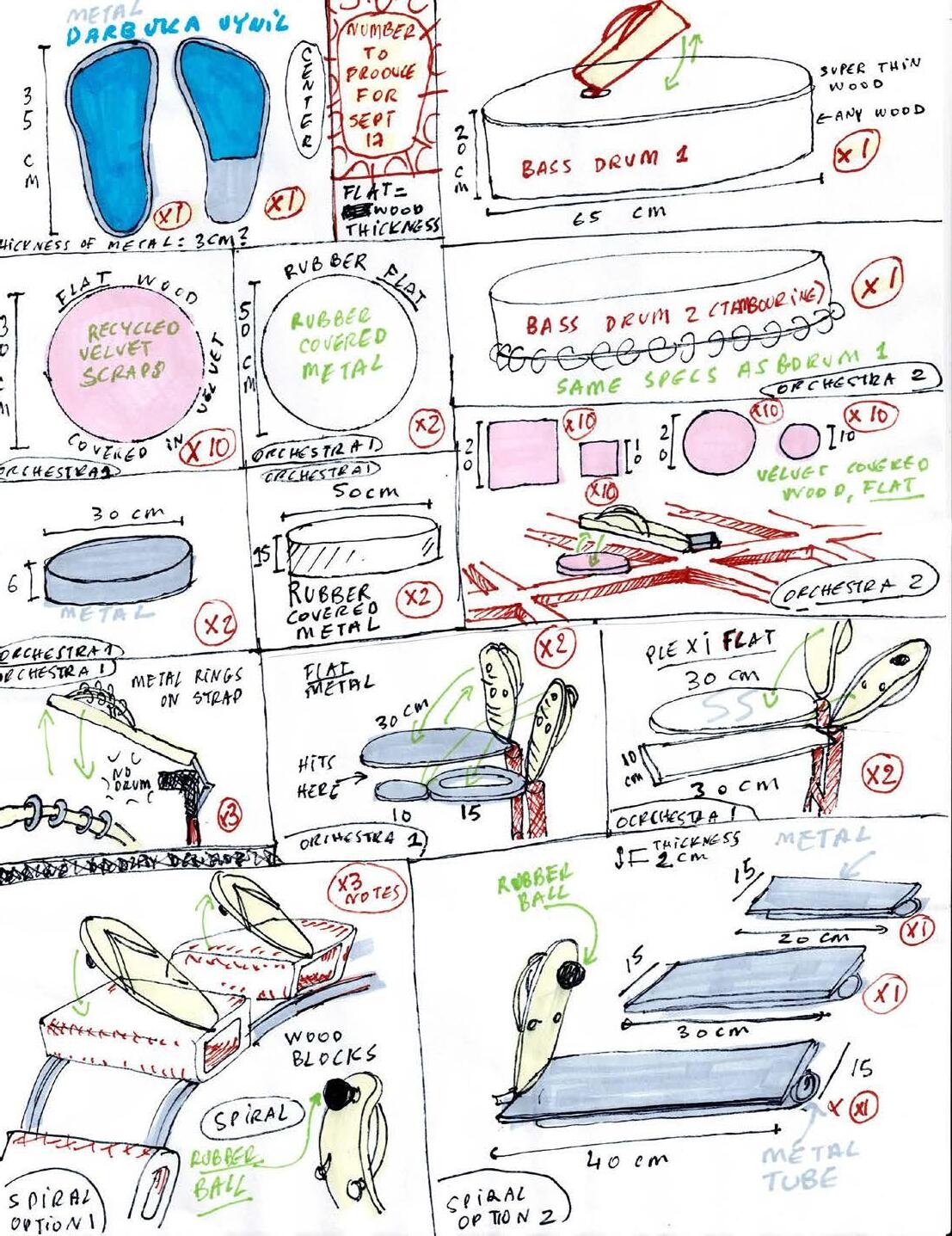

au milieu du bâtiment. Parce que j’aime l’idée que ce soit une seule installation dans son ensemble, qu’il y ait un point de vue par lequel on entre et à partir duquel on puisse tout voir et tout ressentir. Ce n’est pas forcément nécessaire de se balader, mais ensuite c’est possible pour voir les choses de plus près. J’ai commencé par prendre chaque instrument de la première version, puis je les ai placés à des endroits différents. Mais ce sont en fait les mêmes instruments, les mêmes notes. À la Fondazione Prada, il y avait deux spirales. À Lafayette Anticipations, il n’y en a qu’une, mais j’ai transformé la deuxième en un escalier de blocs de bois, en résonance avec l’architecture verticale du bâtiment. Ici, on trouve un nouvel instrument : un orgue. J’ai regardé beaucoup de vidéos de gens qui frappent des tongs contre des tubes en bambou, ce qui produit un son très beau. J’ai aussi vu pour la première fois un véritable orgue lors de ma dernière visite à Paris, et j’ai trouvé ça tellement beau. Donc j’en ai fait un nouvel instrument.

[E.C.] Pourquoi t’être tournée tout particulièrement vers les percussions ?

[M.B.] Les tongs sont percussives, donc je les ai utilisées. J’ai toujours aimé la musique à percussion. La percussion, c’est la seule chose que tu puisses utiliser quand il ne te reste plus rien — à part ta voix.

[E.C.] Comment as-tu travaillé avec Reda Senhaji sur le développement de ces deux versions ? Comment penses-tu qu’il ait influencé la composition de cette pièce ?

[M.B.] J’ai d’abord choisi de travailler avec Reda parce que je savais qu’il connaissait bien non seulement de nombreuses traditions musicales du Maroc, mais aussi celles d'autres pays d'Afrique du nord. Il avait déjà collaboré avec des musiciens de singeli de Tanzanie et des producteurs au Mali. Il a une connaissance approfondie des rythmes, et c’est ce qui m’intéressait le plus. Il a aussi développé

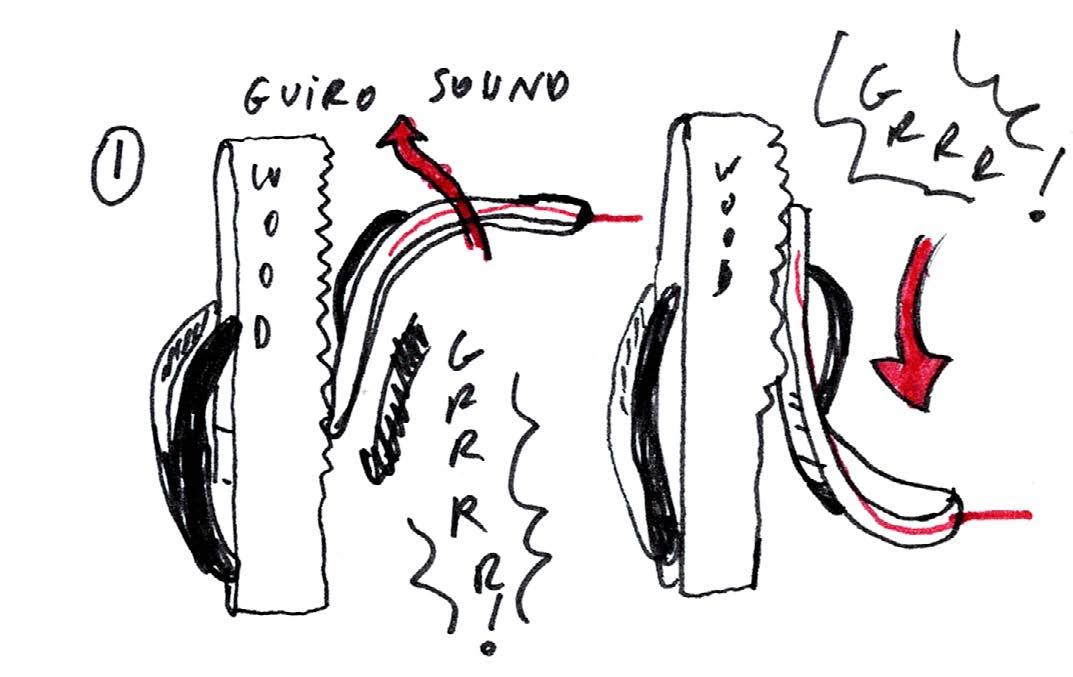

un projet via lequel il digitalise de nombreuses musiques traditionnelles marocaines et crée des boucles prêtes à l’emploi pour les musiciens. C’est un excellent musicien. Il peut tout faire. Il arrive très bien à comprendre comment les instruments fonctionnent physiquement parce qu’il joue de ces instruments. Quand on était en train de construire les blocs de bois pour les instruments en spirale de la Fondazione Prada, il a suggéré de les découper d’une certaine manière pour produire plus de bruit. Il a eu l’idée de rajouter des anneaux sur certains instruments pour créer des sons différents. Il a une bonne compréhension des choses matérielles et de la façon dont on peut les convertir en informatique, pour travailler ensuite avec un programmeur. En amont de la composition pour Prada, je lui avais envoyé des playlists YouTube avec des références variées, du chaâbi marocain à la Clapping Music de Steve Reich, et beaucoup d’autres types de musique en lien avec les percussions, comme le flamenco. On a beaucoup écouté ces références, en essayant de voir ce qu’on pourrait recréer, ou comment fabriquer notre propre version de certaines choses. Pendant l’installation de Sole crushing, Reda a commencé à se familiariser avec les instruments et à improviser. Quand on entendait quelque chose qui nous plaisait, il l’enregistrait et le gardait pour plus tard. Ensuite, on s’est retrouvé avec tous ces segments musicaux qu’on a commencé à organiser pour créer une longue composition, interrompue par des moments qui sonnaient comme des piétinements, des clappements, des émeutes, ou des conversations théâtrales entre les différents personnages. C’était presque comme un jeu. Puis on a trouvé des manières de les connecter les uns avec les autres en un ensemble.

[E.C.] J’aimerais qu’on parle du système qui actionne l’œuvre grâce à de l’air. Les câbles bleus et rouges me font penser au système cardiovasculaire, les instruments prennent vie quand l’air circule, et les rythmes des tongs évoquent les pulsations du cœur. Sole crushing paraît à la fois célébrer des moments de proximité avec d’autres corps, mais aussi faire

écho à la mort. Y a-t-il un lien entre les instants collectifs d’être-ensemble que l’œuvre reflète, et la période durant laquelle tu as commencé à la développer, peu après le Covid-19 et ses confinements ?

[M.B.] C’est drôle, je n’avais pas fait le lien avec le Covid. Quand nous avons commencé à développer la technologie du système, on nous a dit qu’il y avait beaucoup de façons de procéder. On aurait pu le faire avec un système mécanique ou électronique. Mais ensuite, on nous a parlé d’un système pneumatique. J’ai trouvé ça vraiment cool parce que j’adore l’idée de « l’air » comme quelque chose de très simple, mais allié à un système compliqué. Ce qui se passe, c’est que l’air qui le traverse est compressé si intensément que ça peut faire bouger les tubes. J’ai commencé à penser au système respiratoire. J’aimais l’idée d’une sorte de sculpture qui respire, comme si c’était un grand organisme. Une fois que l’air est aspiré d’un côté, il disparaît de l’autre. J'ai l'impression qu’à chaque fois que je dis ça, c’est une manière simpliste de décrire la société ou la politique, mais c’est lié au partage des ressources. Parce que l’idée d’être ensemble et du collectif est au centre de ce projet, mais aussi celle de ne pas savoir comment fonctionner ensemble, ni comment être ensemble, ou d’être divisé·e·s — qui est aussi importante.

[E.C.] Parler de l’importance de l’air m’amène à la dimension magique de cette pièce. Tu fais souvent référence au film d’animation Fantasia, et je pense à la scène de l’apprenti sorcier qui tente de s’émanciper de son maître. Il ensorcèle d’abord joyeusement un balai, mais échoue à le dompter et perd finalement son contrôle : le balai se démultiplie et devient une armée menaçante. Je vois un parallèle avec la tension que tu as décrite entre le caractère comique et mignon de la tong, et son potentiel de violence. Comment abordes-tu cette tension ?

[M.B.] C’est intéressant parce que Fantasia est vraiment magique, mais c’était aussi une démonstration de

prouesses techniques. Le film devait présenter ces chefsd’œuvre de la musique classique européenne ainsi que les progrès de l’époque en termes d’animation. Eisenstein était complètement obsédé par Disney, et il parle de l’aspect « plasmatique » de l’animation. Je pense qu’il a même inventé le concept du personnage animé comme un protoplasme qui peut prendre n’importe quelle forme et devenir n’importe quoi. La manière dont l’animation le matérialise grâce à la magie de la technique. Pour lui, ça représentait toujours quelque chose de très élusif et de très rebelle ; c’est pour ça que c’était si important dans le contexte de la vie banale et standardisée des banlieues américaines, où tout était parfait. C’est presque amusant parce que c’est tout à fait la façon dont Disney fonctionne en réalité. Pour pouvoir faire de l’animation à un niveau industriel, les choses devaient être extrêmement réglementées, et les conditions de travail étaient terribles. On trouve toujours cette tension dans les films d’animation de cette période, même dans Fantasia, ou encore aujourd’hui. Dans le cas de la tong, c’est le cliché de l’objet disciplinaire, celle de ta mère qui se retourne vers toi, celui de ta mère qui te gronde. C’est même devenu un mème populaire dans le Sud Global. Ma mère ne m’a jamais jeté de tongc dessus, mais c’est ce à quoi les gens pensent immédiatement. En plus, ces dernières années, on a vu passer tellement d’images de tongs jetées sur Netanyahu, ou sur d’autres dirigeant·e·s politiques, contre lesquel·le·s les gens se révoltent. Au cours de l’histoire, beaucoup de chaussures ont été jetées au visage de figures politiques, comme George Bush. Une sculpture monumentale est même dédiée en Irak à cet événement. Je pense qu’il y a une connexion entre tous ces éléments.

[E.C.] Puisque nous avons parlé d’animation et de son pouvoir invisible qui donne vie à des choses inertes, je voulais te demander quels sont les autres pouvoirs invisibles que ta pratique invoque. Tu as mentionné le duende, la catharsis ou la transe collective. Vois-tu également ces énergies comme quelque chose de magique ?

Il y a d’un côté la véritable énergie qui traverse les œuvres, et de l’autre la simulation de celle-ci. En animation par exemple, et c’est de là que je viens, on doit maintenir une illusion de vie sur la durée d’une œuvre basée sur le temps. Il faut que les spectateur·ice·s croient qu’une chose est vivante et qu’elle ne s’arrête jamais de respirer. À propos du duende, je me suis intéressée au texte de Federico García Lorca parce qu’il décrit cette sorte de force vivante, cette énergie théâtrale qui vient du pied, et qui a aussi un lien avec la mort. Elle va à l’encontre de l’idée d’être manipulé·e par le haut, comme une marionnette. Même si certaines marionnettes sont viscérales parce qu’on les contrôle à partir de leur ventre. Ça touche aux thèmes de l’origine de la vie et du contrôle de celle-ci. J’aime l’idée du pied et de quelque chose qui viendrait d’en dessous. Enfant, j’accompagnais ma mère et ma grand- mère à des cérémonies d’invocation d’esprits, les cérémonies Gnawa. On disait toujours qu'il fallait enlever ses chaussures pour que les esprits puissent pénétrer par les pieds. Je ne le faisais en fait jamais parce que j’avais trop peur. J’ai aussi toujours aimé l’idée qu’on puisse être électrocuté·e par les pieds sans les prises de terre. Tu vois ce que je veux dire ? J’ai toujours imaginé qu’une chose effrayante viendrait t’envahir par le bas. Et par la suite, ça a été tout à fait logique d’utiliser des tongs, je suppose.

[E.C.] En découvrant l’installation, on ressent quelque chose d’exaltant. Mais, les tongs accrochées à leurs structures, contrôlées par une force externe, évoquent aussi des personnes qui ne sont pas libres de se mouvoir. Malgré sa force célébratoire, Sole crushing est-elle une œuvre dystopique ?

[M.B.] Cette pièce est, dans un sens, une utopie des moments qui fonctionnent bien. Parce que tous les éléments de l’installation sont intégrés à un système qui tourne sans accrocs, qui les aide à produire de la musique ensemble. Pas tout le temps ; parfois, ça s’arrête. Mais je pense que le besoin de créer un tel espace utopique répond à la période dystopique du moment.

[E.C.] Est-ce la première exposition dans laquelle tu n’inclues aucune vidéo ?

[M.B.] J’ai déjà produit des pièces qui n’étaient que des sculptures, mais je suppose que oui, ça fait du bien. Je n’en peux plus des ordinateurs !

Behind the Scenes

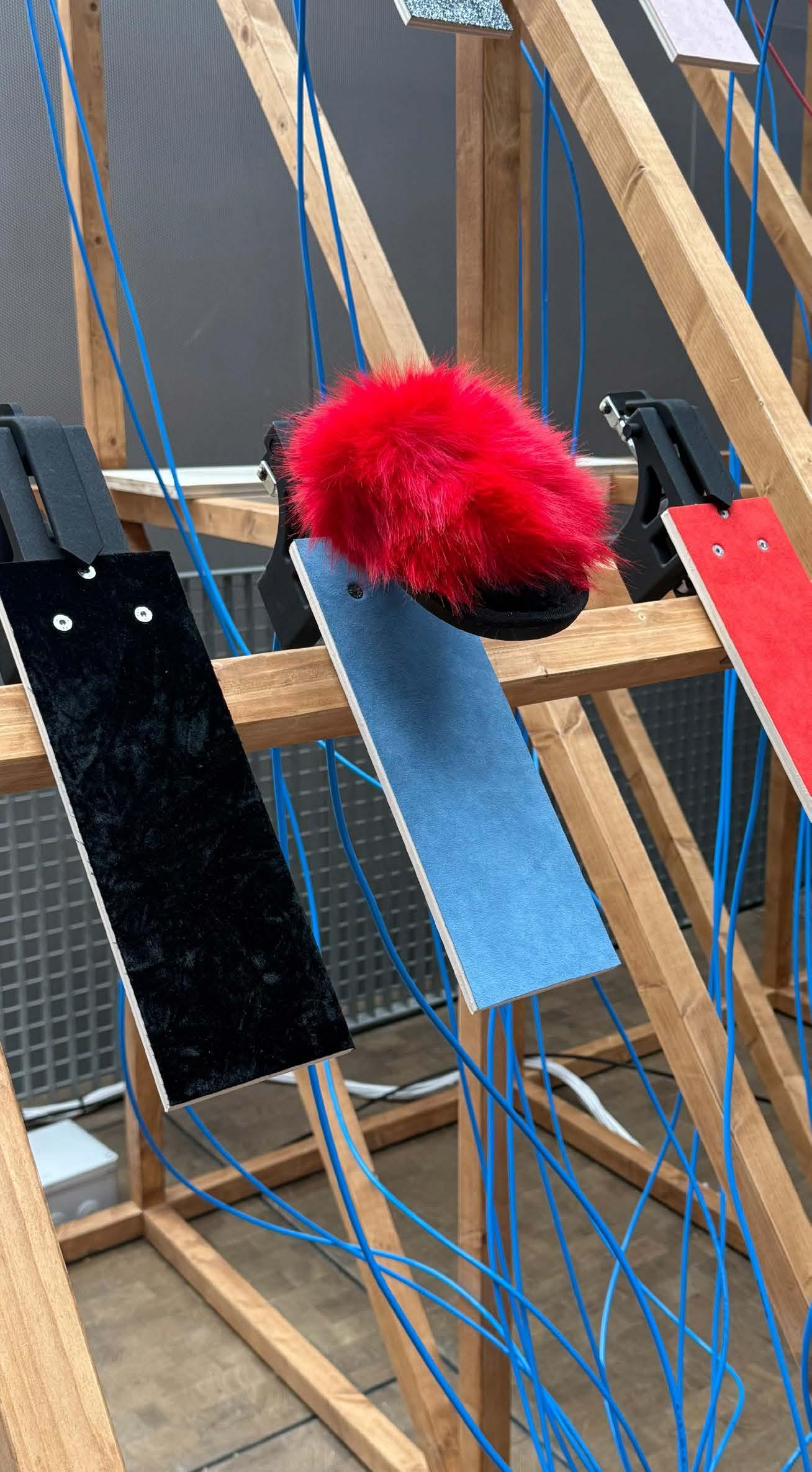

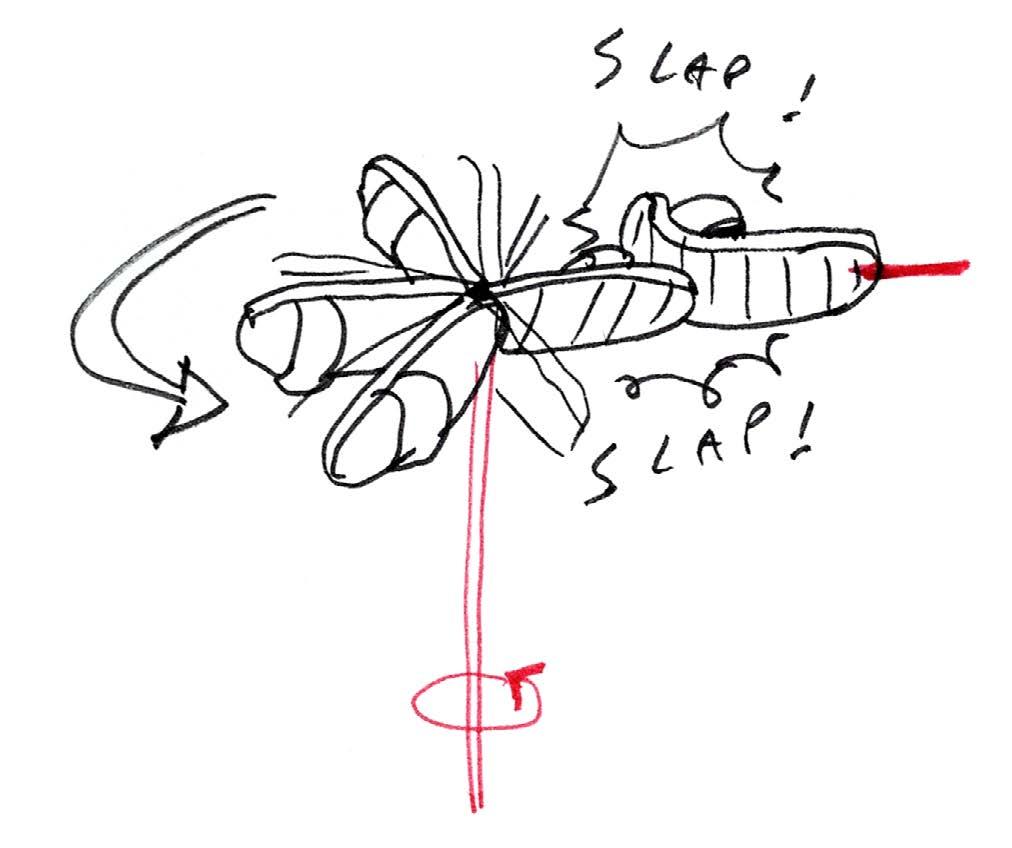

Sole crushing est composée de 201 tongs, chacune reliée à un système pneumatique par deux tubes : l’un reçoit de l’air et enclenche le mouvement de la chaussure, l’autre le récupère et arrête le mouvement.

Cet air anime l’œuvre tel un organisme vivant ou un vaste instrument à vent.

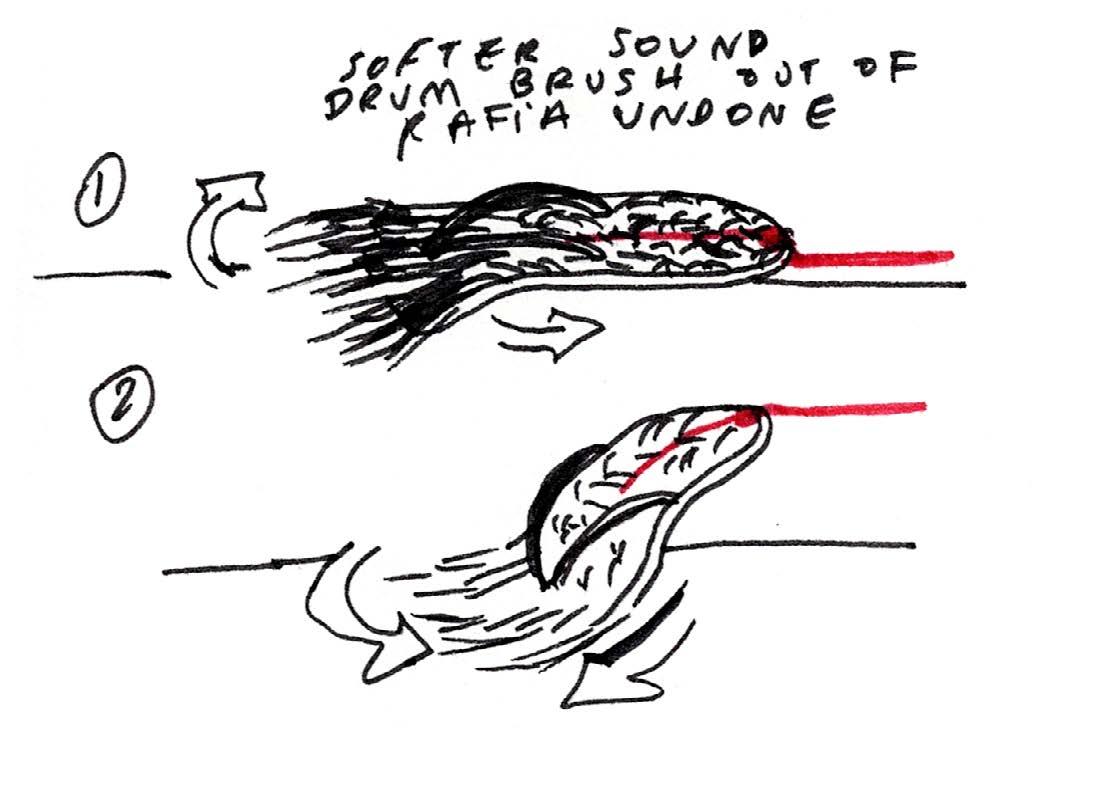

Les frappes des tongs sont programmées et coordonnées suivant une partition musicale originale composée sur un clavier de piano relié à un ordinateur. Selon leurs accessoires, leurs supports (bois, métal, plexiglas ou velours) ou la taille des caisses de résonance, elles émettent un son particulier.

Puisant dans le répertoire de la musique traditionnelle nord-africaine et dans celui de l’orchestre symphonique, Meriem Bennani s’inspire de différents types de percussions tels que les tambours, tambourins et wood-blocks, et imagine un nouvel instrument à tubes qui évoque à la fois un orgue, un marimba et un carillon.

L’artiste choisit la tong pour sa malléabilité et son universalité. Déjà présente il y a 4000 ans dans l’Égypte ancienne, portée dans le monde entier, elle prend ici une nouvelle dimension.

Sole crushing is composed of 201 flip-flops, each connected to a pneumatic system by two tubes: one that receives air and kickstarts a sandal’s movement, the other of which completes the circuit and halts the movement. This air breathes life into the work, like a living organism or a vast wind instrument. The sandals’ claps are programmed and sequenced following an original musical score, composed with an electric keyboard connected to a computer. Based on their accessories, supports (wood, metal, plexiglass, or velvet), and the size of their sound boxes, each shoe emits a particular sound. Drawing on the repertoire of traditional North African music as well as that of symphony orchestras, Meriem Bennani takes inspiration from varied types of percussion such as drums, tambourines, and wood-blocks —in this case imagining a new tubular instrument that simultaneously evokes an organ, a marimba, and a carillon.

The artist chose the sandal for its malleability and ubiquity alike. Already present some 4,000 years ago in Ancient Egypt and today worn around the world, here it steps into an entirely new dimension.

something which is almost emotional. If they’re stomping and making the ground shake, it might become overwhelming or create something. And in my exhibitions, I’m always more interested in provoking some kind of emotional response than intellectual responses. I’m more interested in creating a feeling in order to talk eventually about other things that you can intellectualise. So that intuition I had about using many flip-flops, I think it reminded me of when you have a crowd. Then I started thinking about all those moments where there are a lot of people together for different reasons. Also, on an “animation” level, flip-flops are made out of rubber, and they feel so animated, in a way. They feel very elastic and I have been interested in things that stretch and that are squishy. They are polymorphic, they can change their shape and become something else. In a way, they evade the rigidity of authority and rules. These characteristics then start making sense with the theme of people gathering against authoritarian rule.

[E.C.] Unlike most of your previous works, Sole crushing doesn't seem to rely on narration. However, each flip-flop that you chose and, for some, customised, represents a character. Which stories do they embody?

[M.B.] Fashion is so charged with signifiers, whether they have to convey gender, class, or style. Style is also about class and social norms. Associated with flip-flops, there’s the idea of a certain lifestyle, a neoliberal healthy Californian one; some of them are really girly. I actually got them in Morocco, not in an official store but in a market selling wholesale to other people who then go sell them in markets. All of them are bootleg. Anyway, even flip-flops, as a design, help to emulate a certain kind of lifestyle or a way that you want to present yourself. But these flip-flops are an emulation of the emulation, because they look like some brands. Sometimes I try to take that into consideration when I position them in the space: which ones should be the central ones, or which ones play the bass. I also like the idea that they can always change. Something I really

like about the way that dakka marrakchia works, in opposition to a canonical European symphonic orchestra, where you have the conductor who is guiding with a very centralised power, is that even if there is someone who is called maâlem, which means knowledgeable, who is also a guide, he is actually more like a metronome. I feel like he is more of a heartbeat than a brain. I like this idea that even though in Sole crushing I have a structure with a central island, I have these two flip-flops that act almost as a metronome, and that start the call and response structure of the work. And I have this big bass tambourine hanging above them. In this orchestra, things change all the time. Sometimes, people who play main roles can become secondary in other circumstances. In Sole crushing, there are also two ladders which I call the “military ones”, because they perform this march. It doesn’t matter how they look, but the music and the way they’re organising starts having this almost fascist element to them.

[E.C.] At Lafayette Anticipations you have reimagined the work, putting the audience at the centre, dominated by the height of the instruments. How did the work evolve for this second iteration?

[M.B.] I knew from the beginning that I wanted to do something more vertical and use the big hollow space in the middle of the building. Because I like the idea that it’s one whole installation, that there’s one vantage point where you enter from which you can see everything and experience it all. You don’t necessarily have to walk around. And then you can do that eventually to see things more closely. What I initially did was to take each instrument from the first iteration and then place it somewhere else. But it’s actually all the same instruments, the same notes.

At Fondazione Prada, there were two spirals. Here at Lafayette Anticipations, there is only one, but the second one, I made it into a stairway of wood blocks, to address the vertical architecture of the building. Here, we have a new instrument, which is an organ. I was watching a lot of videos of people using actual flip-flops on bamboo

tubes, which creates a very beautiful sound. I also saw a real organ for the first time, last time I was in Paris, and I thought it was such a beautiful thing. So that’s the new instrument.

[E.C.] What drew you specifically to percussion instruments?

[M.B.] The flip-flops are percussive, so I worked with them. I’ve always liked percussive music. Percussion is the one thing you can do even when you have nothing left—except for your voice.

[E.C.] How did you work with Reda Senhaji on the development of the two iterations? How do you think he may have influenced the composition of the piece?

[M.B.] I first chose to work with Reda because I knew that he was familiar with a lot of musical traditions in Morocco, but also those of other North African countries. He has also collaborated with Singeli music artists from Tanzania and music producers in Mali. So he has an excellent knowledge of rhythms, and that was what I wanted most. He’s also done this project of digitalising a lot of Moroccan musical traditions and making loops available for musicians to use. He’s a really good musician as well. He can do anything. He’s very good at physically understanding how instruments work, because he plays them. When we were making the wooden blocks for the spiral instruments at Fondazione Prada, he suggested that we should cut them to create more sound. He suggested putting up some rings on some instruments to create different sounds. He has a good understanding of physical things and how to translate them into a computer, to then work with the programmer. Ahead of starting the composition for Prada, I sent him playlists on YouTube of different references that range from Moroccan Chaabi to Steve Reich’s clapping music, and many other musical options that have to do with percussion, like flamenco. We listened to those references a lot, trying to

see what we could recreate, or how we could do our own version of certain things. During the installation of Sole crushing, Reda started by familiarizing himself with the instruments and improvising. When we would hear something we liked, he would record it and save it for later. So then we had all these musical segments and we worked on putting them together into one long composition, interrupted by moments that felt more like stomps, claps, riots, or theatrical conversations between the different characters. It was almost like a game. And then we found ways of connecting it all together.

[E.C.] I would like to talk about the system that animates the work with air. The blue and red cables remind me of the blood system, the instruments come to life when there is air circulating, and the rhythms of the flip-flops evoke a heartbeat. Sole crushing seems to me to celebrate moments of proximity with other bodies, as well as evoking death. Is there a link between the collective moments of being together depicted by the work, and the period in which you started working on it, after Covid-19 and its lockdowns?

[M.B.] It’s funny, I didn’t think about the connection to Covid. When we started developing the engineering for the system, we were told that there were many ways to go. It could have been done with a mechanical or an electronic system. And then they brought up the pneumatic system. And I thought that was really cool because I loved the idea of “air” as something so simple, but the system is also complicated. What it means is that the air pushing through is compressed so hard that it can make the tubes move. I started to think of the respiratory system. I liked the idea of a kind of breathing sculpture, as if it’s one big organism, a repetition. Once the air is taken from one side, it’s missing from the other. I feel that every time I say this, it’s a simplistic way of describing society or politics, but there is something about sharing resources. Because the idea of being together and of the collective is at the

centre of this project, but also the idea of not knowing how to work together, not knowing how to be together, and being divided is also important.

[E.C.] Talking about the importance of air in the work brings up the magical. You often mention the animation film Fantasia as a reference, and I think of the scene of the sorcerer’s apprentice, trying to emancipate from his master, at first joyfully taking control of a broom, and failing to tame it, eventually losing control: the broom multiplies and becomes a threatening army of brooms. I see a parallel with what you have described as a tension between the cute and comical aspect of the flipflop and its potential for violence. What is your take on this tension?

[M.B.] It’s interesting because Fantasia is so magical but it was also a demonstration of technical prowess. It was to show all these masterworks of European classical music and all this progress in animation that was made. Eisenstein is really obsessed with Disney, and the “plasmatic” aspect of animation is something he talks about. I think he even invented it, the idea that the animated character is like a protoplasm that can take any shape and become anything. How animation makes that happen through the magic of technique. In his mind, it’s always something that is so evasive and so rebellious; that’s why it was so important in that context of cookie-cutter, suburban American life, where everything seemed so perfect. It’s kind of funny because that’s very much what Disney actually is. To make animation on an industrial level, things had to be extremely regimented, and the conditions of work were crazy. There’s always that tension in the animation of that era, even in Fantasia, or even from today. In the case of the flip-flop, there’s the trope of the disciplinarian object, that of your mom turning to you. At this point, it’s even a big meme in the Global South. My mom never did this to me, but it’s something that people think of right away. Also, there have been so many images emerging in the past years of

flip-flops being thrown at Netanyahu, or other political leaders, that people are protesting against. Historically, there have been a lot of shoes thrown at political figures, like George Bush. There is even a monumental sculpture in Iraq of this moment. I think there’s a connection between all those elements together.

[E.C.] Since we talked about animation and its invisible power to make inanimate things alive, I wanted to ask you about those other invisible powers that your work calls upon. You talked about the duende, about collective catharsis or trance. Do you see those energies as magical as well?

[M.B.] There’s the actual energy that goes through the work, and there’s the simulation of it. In animation, and that’s where I come from, you have to sustain the illusion of life through the length of a time-based piece, right? You have to make people believe that something is alive and never stops breathing. Concerning the duende, I was interested in Federico García Lorca’s text because it talks about this kind of lively force, this tragic marrow coming from the feet, something that has to do with death. It goes against the idea of being manipulated from the top, like a puppet. Even though some puppets are visceral because you control them from their stomach. There’s something about where life comes from and where it is controlled from. I like this idea of the feet and of something coming from below. I grew up going with my mom and my grandmother to these ceremonies about spirits, Gnawa ceremonies. They would always tell me to take my shoes off so that the spirits could come into my feet. I actually wouldn’t because I was scared. And then, I also always liked this idea that you could get electrocuted from the feet, without an earthed socket. Do you know what I mean? I always thought that there was this scary thing coming from the bottom, taking you over. And then it made complete sense with the flip-flops, I guess.

[E.C.] There is a feeling of exaltation when discovering the installation. However, the flip-flops, tied to their structures and controlled by an external force, also evoke people who are not free to move. Despite its celebratory force, is Sole crushing a dystopian work?

[M.B.] The work is, in a sense, a utopia of functional moments. Because all the elements of the installation are in a system that works smoothly, that helps them make music together. Not always; sometimes, it goes off. But I think that the need for creating such a utopic space comes from being in a dystopic moment.

[E.C.] Is this the first exhibition in which you don’t include any video work?

[M.B.] I have done pieces that are only sculptures, but yes, I guess so, it’s nice. I’m tired of computers!

Meriem Bennani est née en 1988 au Maroc et vit à New York. Dans ses sculptures, ses installations ou ses vidéos, elle explore les possibilités de la narration en sublimant la réalité grâce à une approche qui mêle réalisme magique et humour.

Elle est titulaire d’un BFA de la Cooper Union à New York et d’un master de l’École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs à Paris. Son œuvre a fait l’objet d’expositions monographiques à la Fondazione Prada, Milan (2024-25) ; la Fondation Kamel Lazaar, Tunis (2023) ; le Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2022) ; The High Line, New York (2022) ; The Renaissance Society à l’Université de Chicago, Chicago (2022) ; Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham (2022) ; Kunstverein Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden (2021) ; François Ghebaly, Los Angeles (2021) ; Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin (2020) ; Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (2019) ; et MoMA PS1, Queens (2016). Son travail a été présenté à la Biennale Whitney 2019, à la Biennale des images en mouvement 2018 et à la Biennale de Shanghai 2016. Meriem Bennani a participé au dernier Festival international du film de Toronto avec son long métrage d’animation Bouchra, co-réalisé avec Orian Barki.

Ses œuvres ont rejoint les collections du Guggenheim Museum, New York ; du Museum of Modern Art, New York ; du Whitney Museum of American Art, New York ; de la fondation Kadist, Paris ; du Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris et de Lafayette Anticipations, Paris.

Meriem Bennani was born in 1988 in Morocco and lives in New York. In her sculptures, installations, and videos, she explores the potential of storytelling while amplifying reality through a strategy of magical realism and humour.

She earned her BFA from Cooper Union in New York and her MFA at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Recent solo presentations include Fondazione Prada, Milan (2024–25); Fondation Kamel Lazaar, Tunis (2023); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2022); The High Line, New York (2022); The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, Chicago (2022); Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham (2022); Kunstverein Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden (2021); François Ghebaly, Los Angeles (2021); Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin (2020); Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (2019); and MoMA PS1, New York (2016). Her work was featured in the 2019 Whitney Biennial, the 2018 Biennial of Moving Images, and the 2016 Shanghai Biennale. Bennani participated in the most recent Toronto International Film Festival with her feature-length animated film Bouchra, co-directed with Orian Barki.

Her work is held in the collections of the Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Fondation Kadist, Paris; the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris; and Lafayette Anticipations, Paris.

Lafayette Anticipations

Créée à l’initiative du Groupe Galeries Lafayette, Lafayette

Anticipations est un lieu d’exposition et d’échanges consacré aux arts visuels et vivants. Située au cœur de Paris dans le Marais, la Fondation invite à découvrir d’autres manières de voir, sentir et écouter le monde d’aujourd’hui pour mieux imaginer, grâce aux artistes, celui de demain.

Created on the initiative of the Galeries Lafayette group, Lafayette Anticipations is a place of exhibition and sharing dedicated to the visual and performing arts. Located in the heart of Paris in the Marais district, the Fondation invites visitors to discover other ways of seeing, feeling, and listening to today’s world in order to better imagine, thanks to artists, the world of tomorrow.

L’équipe de Lafayette Anticipations / Lafayette Anticipations team

Lisa Audureau, Marie Bernard, Étienne Blanchot, Géraldine

Breuil, Ysé Collomb, Elsa Coustou, Clélia Dehon, Camille

Drouet, Cécile Dugat, Delphine Eyffert, Annabelle Floriant, Lourdes Garcia, Anatoli Gilbert, Mehdi Görbüz, Coralie Goyard, Cécile Hadj-Hassan, Heloïse Hamon, Guillaume Houzé, Jan Kusnierak, Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel, Jade Larrat, Helena Lyon-Santamaria, Aurélie Madile, Chloé Magdelaine, Olivier Magnier, Matthieu Maytraud, Elisa Normand, Lise Petulla, Madeleine Planeix-Crocker, Bettina Puchault, Pierre de Quelen, Raphaël Raynaud, Alexandre Rondeau, Yulia Sakun, Antonine Scali Ringwald, Lounès

Senelet-Maïté, Simona Skristapaviciute, Julia Stankiewicz, Sara Vieira Vasques, Émilie Vincent, Éloïse Yapo

Cet ouvrage paraît à l’occasion de l’exposition

Sole crushing de Meriem Bennani à Lafayette Anticipations, du 22.10.2025 au 08.02.2026

This book was published on the occasion of the exhibition Sole crushing by Meriem Bennani at Lafayette Anticipations, from 22.10.2025 to 08.02.2026

Éditions

Lafayette Anticipations

Sous la direction de Directed by Guillaume Houzé, et / and Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel

Direction éditoriale

Editorial direction

Meriem Bennani

Elsa Coustou et / and Antonine Scali Ringwald

Traduction et relecture

Translation and proofreading

Emmanuel Pierre

Chris Marie Tyan

Conception graphique

Graphic design

Studio Charles Villa

Impression Indigo

Indigo printing

Avenir Numérique

Papiers / Papers

Symbol Fusion

Symbol Freelife Gloss

Typographie / Font

Aperçu Pro

Crédits photo / Photo credits

Couverture / Cover et p. 26–32 / and pp. 26–32 : © Théophile Mottelet Toutes les autres images / All other images : © Meriem Bennani

ISBN : 978-2-490862-60-3

Dépôt légal : octobre 2025 © 2025 Lafayette Anticipations