et.al.

1 2 3 4

1 Rudolf von Laban Neigung rechts 5A-Skala [Tilt right 5A scale] (above), Neigung 2-(e) , (r0) aus der B-Skala [Tilt 2 -(e), (r0 ) from the B scale] (below), undated, photographer unknown [L] 2 No title, Jenny Gertz estate, undated, photogra pher unknown [L] 3 Poster advertising 2nd Dancer Congress of 1928 in Essen. Max Burchartz, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009 [L] 4 No information given [L]

»I praise the dance, for it frees people from the heaviness of matter and binds the isolated to community. I praise the dance, which demands everything: health and a clear spirit and a buoy ant soul. O man, learn to dance, or else the angels in heaven will not know what to do with you.« We do not know whether St. Augustine, theologian, philosopher of late antiquity, and one of the most influential fathers of the Church, was referring to his personal experience with dance. Yet amazingly enough, St. Au gustine grasped an essential aspect of dance that still holds true today. At least this is what the articles in this special dance issue seem to say. Freed from the heaviness of matter in his literary essay Foreplay , Michael Kleeberg describes the incred ible lightness of dancing in his first erotic encounters on the dance floor. Dorion Weickmann portrays the hubris with which we praise dance as the miracle drug for physical and men tal fitness. Gabriele Brandstetter considers the commu nity-building and culturally-connecting power of dance, while Christina Deloglu wonders why dance films are cult and why they’re especially appealing to teenagers. In selecting pieces for this dance issue, we wanted to show our readers that dancing is not only relevant to experts. In daily life and at special occa sions, dancing is more popular and widespread in society than many other artistic forms of expression. Could it be that our rela tionship to dance is rudimentary because we know less about it and its history than about literature, theatre, film and the fine arts? Could it be that dance struggles to gain public recognition for its cultural significance because we are simply too poorly trained in understanding the language of dance?

With this issue we »praise the dance«, knowing well that dance lives in the shadows of its more illustrious relatives as far as public perception goes. Of course, the Dance Plan Germany , initiated by the Federal Cultural Foundation, has done much to improve the national structures of contemporary dance for the long term. However, when the massive funding measures conclude in 2010, there will still be a lot of work to do. We are confident that the dance scene has gained valuable experience from the support of the past five years which will continue to strengthen its educational efforts and help cultural policymak ers secure new funding in the future. The Dance Plan is coordi nating its second major dance congress, which will take place in Hamburg from 5 to 8 November 2009. It has invited dance ex perts from the practical and scientific fields to work on solving the problems facing dance in Germany in the future and develop strategies for anchoring dance in cultural politics. And it also offers us an occasion to produce a dance issue, for which we scoured an enormous amount of photo material in the dance ar chives in Cologne and Leipzig. We are grateful to Thomas Tho rausch and Bettina Hesse (Cologne) and Dr. Janine Schulz (Leip zig) for their extensive help and support. With their special com bination of passion and precision, Daniela Haufe and Detlef Fiedler (cyan, Berlin) selected the photo material for this issue. Although space is limited, these photos exemplify the incredible wealth of our dance heritage.

As always we have provided our readers with an overview of the projects which we are currently funding, and insights into the work of our larger programmes. With regard to the KUR

Programme for the Conservation of Moveable Cultural Assets, Stefan Koldehoff reveals fundamental problems with pre serving our cultural heritage indefinitely. Regina Bittner examines the legacy of the Moravian city Zlín, one of the only planned cities in Europe, where the shoe manufacturer Bata built his vision of a utopia of modernity . This was also the title of an international conference, part of the ZIPP GermanCzech Cultural Projects , which commemorated and investigated the lessons of this legacy. In her report on the fate of Home Game theatre projects, Michaela Schlagen werth describes how theatre artists collaborated with residents of their city to research and produce plays with locally-specific themes in unusual ways. And finally, we conclude our literary series Fathers & Sons with a short story by the Polish writer Wojciech Kuczok, titled How we failed to over throw Communism . In commemoration of the 20th anniver sary of European unity, we asked young writers from Central and Eastern European countries to write about their personal memories and describe how the social and political upheaval in fluenced the relationships between fathers and their sons.

dance michael kleeberg foreplay 6 interview with hortensia völckers »we can only change things through experience« 13 dorion weickmann ultraslim and supersmart? 21 gabriele brandstetter nomadic dance 24 christina deloglu a dream come true 32

fathers and sons wojciech kuczok

how we failed to overthrow communism 35 kur stefan koldehoff sisyphus at the museum 38 zipp regina bittner rise to the ovation 44 home game michaela schlagenwerth the audience loves it 46

news 49 projects 50 committees 55

The photos in this issue are among the many treasures stored in the dance archives in Cologne and Leipzig. Although this issue is awash with images from these archives, we were only able to show you the tip of the iceberg. Making the right choice was an agoniz ing task. We constantly asked ourselves which pictures had made a mark on the cultural memory of dance, and which were missing? The Federal Cultural Foundation does not only support contemporary dance with its Dance Plan Germany , but is also com mitted to documenting the history of dance and having it publicly recognized as an integral element of our cultural heritage. The transient art of dance faces special challenges if it wishes to preserve its own history and use it for current and future develop ments. This is why the Dance Plan also included the dance archives in its funding catalogue. The pictures from the archives shown here were selected based on the wish to create a panorama of dance that extends beyond the art of contemporary dance and establishes it as a comprehensive cultural practice. /// The captions correspond to the descriptions found on the reverse side of the photos. In some cases, we were unable to determine the photographer despite extensive research. Therefore, we publish these photos, understanding that entitlements and copyrights can be claimed by their rightful owners. [C] = Cologne [L] = Leipzig

foreplay

by michael kleebergFor a long time, I considered dance nothing more than the neces sary foreplay to the sexual act.

Of course, in my young teenage years, the act was never consummated, but was a possibility in theory and fantasy. It was as close to sex as I could get. Dancing was the only legitimate way of touching a girl, coming in close physical contact, so close to evoke that unbelievable and unfamiliar feeling of excitement. The fact that you had to keep moving the whole time was a neces sary evil. And by closing your eyes, you could easily imagine away the clothes you were both wearing. For most boys like me between fourteen and twenty-four, dancing was the means to an end. A ploy, because in those years the 1970s a boy could not expect that a girl wanted this same kind of intimate contact. Actually, it was inconceivable. Therefore, we had to outsmart them, and practically the only way we had of doing this was to dance with them.

But can we really call what we did, dancing? Because what we boys were waiting so impatiently for at school parties, private get-togethers, community dances, etc., were the few slow dances that a sympathetic disc jockey would toss in after every fifteen or twenty songs what we used to appropriately call the stand ing blues in my hometown in Swabia. No one in their right mind would have called standing blues dancing. It was ob vious that it was nothing more than a concession to us teen-age, hormone-crazy boys.

I remember there were two types of male dancers at those gettogethers. There were the guys who flirted during the normally fast songs when there was no touching. Sometimes it wasn’t even clear who was dancing with whom. They’d show off like rutting pigeons with fluffed necks and plumes and fanned tails, strutting back and forth in front of the females, cutting off their path of retreat, wiggling their butts and cooing ridiculously.

Then there were the boys who made no attempt to hide their in tentions, waited out the fast songs and immediately pounced on the girls on the dance floor as soon as the slow song began. As if they were at the amusement park, rushing to grab a free bumper car before the siren sounded.

As for myself, I belonged to the group of compromisers who put on a brave face, fidgeted and jerked around on the dance floor just so we’d be ready and close to our partners when Child in Time by Deep Purple came on. You have to remember, we were in Böblingen, and nothing was as crushing to a boy’s reputation as unmanly, exalted, girlish behaviour and John Travolta and Michael Jackson weren’t around yet.

My generation was probably the first in the 20th century to no longer cultivate the traditional partner dance, the ballroom dance, which most likely disappeared from youngsters’ lives be tween Rock’n’Roll and the Twist. A loss of culture, in my opin ion, looking back on it today. Because even if the male teenag-

ers of previous generations shared my opinion of dance and pur sued similar goals as we did (women dance for completely different reasons), the choreography of their dances, from the waltz to the foxtrot, forced young men to exercise restraint and disci pline, which was totally lost on us as we rubbed ourselves against our female dance partners like animals.

I believe dance, like some parts of society, is returning to a period of tribalization and barbarism, for which the loss of complex rules and forms of etiquette is only an example. We can also see this in the tendency to dance by and for oneself, a form of exhibi tionism, autism, a celebration of one’s body as a unique artwork with all its piercings, tattoos, fake fingernails, pumped muscles and an aura of the hermaphroditic. Such a third sex no longer needs a dancing partner, just an audience doesn’t need sex, just Facebook

The triumphant arrival of discos, later called clubs, began in my youth, but what a difference there was between the harmless Seestudio in Böblingen which, at age 15, I went to after a classmate told me that’s where I could get a certain girl I liked to notice me, and the bright, white Bhagwan Discotheque in HamburgPöseldorf, to which I took a model friend of mine ten years later to present myself as modern and trendy in a new, post-apoca lyptic world of pleasure that was just beginning in the early eight ies. And how different that was compared to the techno disco I went to with a group of colleagues while on a business trip in London at the end of the nineties. The infernal noise took my breath away, and since then, it has become my image of hell. If there truly is as Dante would say a personal hell for every one, then that is what mine would look like, although I believe I could afford to expand my list of sins a little before I’d have to descend into that hell.

I am not all too ashamed to admit that the basis of my relation ship to dance was for the most part sexually driven. After all, in its infancy in early civilizations, dance was nothing more than either a choreographed religious or fertility ritual both of which quite often overlapped. Over the course of thousands of years, it spawned numerous forms of high culture church wor ship, tragedies, operas, sports and porno films.

Early in my life, even before puberty, I became a person of words, that is, someone who creates, justifies and defends his identity and position in groups and society with words, and not with the body. Growing up in Swabia, that made me a minority and an outsider, as reputations were formed by the body and its achieve ments. Dance was communication that occurred exclusively through the body. It seemed strange and suspicious to me very early on, it was territory I had no desire to explore, and as a result, I had to begin playing it down. A disco the place where it’s too loud to communicate with words has always been a hostile environment for me.

However, when I was sixteen and attended a graduation party for the senior class, I discovered that I had been fooling myself dur ing puberty, instrumentalizing dance for the purpose of initiat ing a sexual relationship. Something utterly embarrassing hap pened to me, and perhaps that’s why I remember it as if it was yesterday. I was wearing my usual party attire white jeans that were so tight that it took me forever to put them on and even longer to peel them off like a sausage skin, so tight that you could see whatever I was feeling through them, which in my youthful naiveté, I thought to be especially attractive and seduc tive. It was the night it finally happened the one and only thing I had always fantasized about. As I pressed myself up closely to one of the graduating girls, she actually took the bone of contention in her hand and said something similiar to Mae West’s famous line »Is that a gun in your pocket are you just happy to see me?« at which point she invited me to follow her into one of the many empty classrooms.

It was too much for me. Too much, too concrete, too suddenly Rhodos, that I didn’t dare take the leap. This confirmation of my tactics, this straightforward proof of my theory that dance only represented foreplay was shocking to me. Like Joseph before Mut-em-enet, Potiphar’s wife, I felt transformed into an ass, flee ing from her with rambling explanations and excuses, each one more ridiculous and flimsy than the next. The fact that I was able to keep my shirt on was only a small consolation.

Years later, as I began leading a normal, adult love-life, no longer warped by chronic shyness, cowardice and clumsiness, dancing didn’t play much of a role in my life. It was no longer necessary.

But how did it all begin? What are my earliest memories of dance? My parents used to tell me about the lavish balls they attended when they were young, and later about the dance orchestras and swing music of the early post-war years. But I only saw them dance once or twice a year in the festival tent at our town fair. My mother told me she’d taken dance classes and had been an avid dancer, especially when her partner could also dance well. This was incomprehensible to my father who admitted that he had felt jealous when other men danced with her. For my father, if dancing with another man was fun to her, how could he not be a competitor? And for my mother, she couldn’t understand what the one thing had to do with the other.

Whenever I watched them dance as a child, they danced the two dances that were sufficient for every occasion the waltz and a makeshift dance for all songs in four-four time, a dance our family vividly described as the slide.

And so the stiff-necked, heavy-footed couples would slide across the wooden floorboards of the beer tent, joined by a few fops who were known around town as passionate dancers. With Bril liantine in their hair, they’d thrust their right elbows out, heads cocked over their right shoulders as if they were parking a car,

1 Susanne Linke in Schritte Verfolgen [Following Steps], solo dance performance in collaboration with VA Wölfl, 1985, photo: gert-weigelt.de [C] 2 Valeska Gert in Ca naille , undated, photo: Lily Baruch [C] 3 Constanza Carrys, named The Little Pavlova Postcard, Iris Verlag, photo: »Gertrud«, Vienna [C]

pumping their partner’s right hand up and down in time with the music, as if they alone were responsible for providing the town’s water supply.

It was not a pretty sight for children’s eyes, but rather a bizarre performance for eight or nine-year-olds, for whom nothing is more important than that their parent’s preserve their dignity, or what they believed was dignity (which often implied not hav ing fun).

Thanks to Hollywood films, I became aware that there were dif ferences, aesthetic differences in the way one moves dancing or otherwise and that these were differences of life. It was my first encounter with dance as an art form.

The first films with Fred Astaire and his ever-changing partners, mainly Ginger Rogers, of course, were a revelation to me. For the first time in my life, I witnessed grace. For the first time, I wit nessed elegance. And when Fred Astaire was joined by Gene Kelly, the further evolution of the athletic-plebeian man who defies the laws of gravity and deconstructs the myth that man is a lump of clay, I witnessed the impossible. It was the solution of the dilemma, rooted in outdated male role models which I grew up with and the Swabian code of behaviour, of which I was a victim, namely, how one could be both elegant and athletic, a dancer and a man, how one could unite sophistication (which I desired) and physical consciousness (which I didn’t possess) with artistic beauty. Only in theory, of course.

With Gene Kelly, the unattainable (for us mortals) became reali ty. With Fred Astaire, the indescribable became an indisputable fact. Until that point, my role model for grace had been Henry Fonda as Wyatt Earp in John Ford’s My Darling Clemen tine . How he tipped back in his chair on the veranda in Tomb stone with perfect balance, gazing at the far-off mountain tops of Monument Valley, how he reluctantly agreed to dance at the church fair and executed a perfect square dance with the absolute dignity of a man whose balance was unshakeable that’s the kind of man I aspired to become, admired by the ladies and feared by the villains.

But Astaire and Kelly took it one step further. When moving normally or demonstrating superhuman elegance and breath taking expression in dance, they no longer had to overcome an inner reluctance. The bodies of these gods spoke a language more clearly and artistically than words. And what were they speaking of? At the time, I couldn’t decipher or understand it, but now I know it was, of course, sexuality.

What did they say about the dream couple Astaire/Rogers in the 1930s? »He gives her class and she gives him sex.«

Certainly, the overwhelming success of the musicals of the thir ties and forties was also due in part to the Hayes Code Holly wood’s attempt at self-censorship which forbade, for example, a scene of a woman on a bed unless both her feet were touching the floor. When I was young, I didn’t realize that every dance scene was actually a metaphor for sexual intercourse a fact I’ve only come to appreciate since movies began showing explicit sex scenes which don’t even come close to the erotic force evoked by the big musical numbers. And the passing of musicals oc curred almost simultaneously with the liberalization of moral standards in American movies.

Later on, I kept on dancing the standing blues — not only because of the unconscious lesson these musical numbers taught me (an eternal amateur and klutz in comparison), but also because of what I learned from An American in Paris and Singin’ in the Rain , a lesson I didn’t quite understand at first and couldn’t yet put into practice. At certain moments of sheer elation, dance could catapult one beyond the arena of fore play and become a unique celebration of oneself, of one’s body, in an oblivious, incredibly expressive show of the joy of being. It wasn’t necessary to have a partner (or one of the opposite sex), but simply to explore the space of one’s body without any explicit purpose.

Gene Kelly’s unforgettable night-time dance through the pud dles of Paris, Donald O’Connor’s breathtaking choreography in Make ’em Laugh , and both of them in Fit as a Fiddle and Moses Supposes , were examples of the homo ludens, the human being unfettered by the bonds of functionality and so cial conventions. That was art. That was the kind of art that slaps you in the face like the words of a Zen master, or that particular painting or musical composition that declares: You must change your life.

The fact that this experience wasn’t elicited by Cranko during my childhood in Stuttgart, or Neumeier as a young adult in Hamburg, or Nureyev, Sylvie Guillem or Karin Saporta while I lived in Paris, but rather by Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire is probably a sociological phenomenon. There are certain social classes that go to the cinema and not to the ballet or opera house and what Hans didn’t learn as a child, he may never learn as an adult. I did find my way to opera as I grew older, but not to ballet. Do I regret it? To a degree.

Years later I lived in France and hadn’t danced anymore, except at weddings, yet I became acquainted with another dimension of dance that I had not seen or understood before. Dance as a community-building phenomenon, as a display of good will, an expression of not only being tolerated by others (also by stran gers), but to be assimilated by them for a certain period of time. As Goethe would say: Here I am Man, here dare it to be! I’m referring to the bals des pompiers , the popular dance parties organized by the fire departments in all quarters of Paris on the night before the 14th of July, the national public holiday. As parties, they were not high-class events some had a band, some had a small ratty-tatty orchestra, the rooms smelled like Merguez and soured rosé wine, but that didn’t dampen anyone’s spirits. Children danced with children, old women with old women, daring young lovers danced the salsa even if the music didn’t fit. If a stranger asked your wife to dance, you’d raise your glass good-naturedly, and you wouldn’t discriminate either and dance with any woman regardless of her age, scent or girth. Of course, I was initially distrustful of the seemingly phony and forced party mood until I realized that everyone there was genu inely happy to feel that sense of belonging and community at a time when people rarely have an opportunity to do so. Remem bering the supposedly or truly great moments of history like 1789 or 1944 when the French felt like one people, the partygoers cele brated that feeling once again in this innocent, but not meaning less revival.

So in the end, dance showed me the kind of person I was to quote Jean Paul Sartre someone »made of the stuff of all peo ple, and as valuable as everyone, and as valuable as anyone«.

Michael Kleeberg , born in Stuttgart in 1959, is a writer and literary translator of such authors as Marcel Proust, Joris-Karl Huysmans and John Dos Passos. After extended stays in Rome and Amsterdam, he moved to Paris where he lived for twelve years. Today he is a resident of Berlin. Kleeberg has received numerous literary awards, including the Anna Seghers Prize , the Lion Feuchtwanger Prize and most recently, the ›Mainzer Stadt schreiber 2008‹ literary award. As part of the project West Eastern Divan , funded by the Federal Cultural Foundation, Kleeberg wrote the Leba nese travel diary Das Tier , das weint [The Animal That Cries] ( DVA , Mu nich 2004), in which he describes and reflects on his impressions of Beirut and his meetings with the writer Abbas Beydoun during his four-week stay there. Kleeberg’s most recent novel is titled Karlmann , published by DVA in Mu nich in 2007

1

1 2 3

1 Standard dance, undated, photo: Schirner Ber lin [C] 2 Postcard, Blohm Rostock 1908, photographer unknown [C] 3 Reinhild Hoffmann in Solo mit Sofa [Solo with sofa], 1980, photo: gert-weigelt.de [C]

»we can only change things through exper ence

Petra Kohse: Ms Völckers, the Federal Cultural Foundation is currently the most important funding institution for the field of dance in Germany. And the Dance Plan , which the Foundation initiated in 2005, is one of its most massive funding programmes. In your position on the Executive Board, do you see dance as a top priority?

Hortensia Völckers: We have to make it one. In comparison to other fields of high culture, dance is under-represented. Although over 70 municipally funded dance companies exist in Germany and their performances are well at tended, the performers themselves work under poor conditions at most venues. They require larger budgets to hire good dancers and have to engage guest choreographers, so that audiences don’t get bored with a style they’ve seen for the last five years.

Kohse: Why is dance funding so limited?

Völckers: In contrast to theatres with their elo quent, self-assertive theatre directors, dance has no lobby. Dance artists are not accustomed to representing their interests. And this is not be cause they generally use their bodies instead of words or because the majority of them are for eigners and didn’t learn German as native speak ers. It’s because there’s no one who represents their interests in committees and lobbies for more money when funding is distributed. There are mainly choreographers, dance companies and occasionally dance dramaturges, all of whom have their hands full with artistic work. Ideally, they’d need a dance director or dance managing director to be in charge of funding acquisition. Like in Berlin where Christiane Theobald, the current managing director and representative of Vladimir Malakhov, played an integral role in putting the Staatsballett Ber lin on sound financial footing, thereby ensur ing its artistic autonomy.

Kohse: Where should we begin in order to im prove the situation?

Völckers: Municipalities are essentially responsi ble for their theatres. The head of cultural af fairs in one city can have quite an impact, as we’ve seen in the past. I’m thinking of Hilmar Hoffmann whose massive support of the head dramaturge Klaus Zehelein in the mid-1980s attracted William Forsythe to Frankfurt. He stood firm by his decision, though subscrip tions were cancelled and the opera played to al most empty houses in the beginning. He was convinced that Forsythe was the best, and there fore, the ideal choice for his city. Eventually, Forsythe’s international acclaim proved him right. It was similar with Pina Bausch in Wup pertal ten years earlier.

On the whole, it takes massive pressure from au diences to make theatre budge an inch for the sake of dance. And the dance community has to become active to create this pressure. The dance artists, too, have to be stronger and force them selves to raise their voices. The performances have to have better quality, attract larger audi ences and receive much more attention from the press. The cultural section in newspapers hardly contains any features on dance.

Kohse: Which we cannot only attribute to the editors’ ignorance, but also the truly difficult task of writing about dance in such a way that interests a large portion of the readership.

Völckers: Writing about music is also difficult, but no one has to justify it! Because in our society, music in contrast to dance is regard ed as an educational asset. Almost everyone has a musical style they grew up and can whistle its melodies. This is the kind of literacy that dance should also aim to achieve. And it won’t be easy because there is hardly a repertory which one can learn. In ballet, yes. But not in modern dance works. And definitely not in Germany. There’s no Wigman here that you can see, no Limón, no Cunningham nothing from which ultimately everything in this area origi nates. And the problem is far more serious for dancers than for the viewers. That’s why improv ing dance literacy in Germany is an extremely urgent issue.

Kohse: There are musical scores for classical bal let. Why not modern dance? Are the choreogra phies so specific to certain companies that the works can no longer be interpreted differently when removed from the artists?

Völckers: I don’t know why so little is passed on to other dancers. Pina Bausch always wanted to have her works performed by her own dancers with the exception of two pieces she developed for the opera in Paris. Anne Teresa De Keers maeker doesn’t give anything away, either. The same goes for Meg Stuart…

William Forsythe, on the other hand, is current ly developing a system of dance notation to al low other choreographers to stage an existing choreography. In a pilot project titled Syn chronous Objects , he recorded his com pany’s performance of One Flat Thing , reproduced from 2000 with multiple cam eras from various angles. As each dancer is marked with a specific colour, the lines of move ment are precisely depicted on film, creating a complex, but understandable portrayal of the performance. Other choreographers can make practical use of this system of notation for their own works as well. The goal is to create a digital archive or Motion Bank

«

an interview with hortensia völckers on the need for dance literacy

Forsythe wants to preserve his other works in the same way, so that young dancers and future audiences can access them in the future. In this way, they’ll know what they have to be aware of, and not always leave the performances, saying »I don’t know what really happened in there.«

Kohse: But even if we know what we must be aware of does that mean we really understand the work better? Do we know what it’s about? Völckers: When you listen to a piece by Luigi No no, do you necessarily know what it’s about? Feelings and associations are the first things that take shape when we perceive abstract art! Modern dance, on the other hand, actually pos sesses a rich history of very concrete social refer ences. It started with the female dancers at the beginning of the 20th century who took off their ballet outfits, danced barefoot and expressed a feeling of life through the feeling of the body! Independent women like Isadora Duncan also led private lives which were socially unacceptable at the time. She had children out of wed lock and danced in nature wearing transparent clothes! And then came the expressive dances of Mary Wigman these were clearly emotion ally loaded statements the Witch Dance and The Seven Dances of Life In Germany, in particular, theatrical forms have played a larger role in dance. Including the obvi ously politically-oriented choreographies based on Frida Kahlo or Baader-Meinhof by Johann Kresnik. Pina Bausch addressed the role of women, the structure of relationships and the issue of age when she worked with dancers who were over 65 in her piece Kontakthof in 2000 However, the reason why dance remains on the margins of high culture has nothing to do with the inability to communicate through dance, but rather the lack of access to dance. And to make dance more accessible, we not only have to improve the institutions, but also and most importantly at least in my opinion intro duce it to children.

Kohse: Teaching children at school how to un derstand dance?

Völckers: Yes whereby understanding comes with experience. And with experience comes the desire for more later in life. If every child in Berlin gained enough experience with dance and movement so that they could build a natu ral relationship to the genre, they would also watch dance as adults and bring up their chil dren in the same way. And that’s how we could integrate this issue into our culture. It doesn’t happen with festivals or newspapers, but only when an entire generation has gained positive experience with it. We can only change things through experience.

Kohse: And it wouldn’t only be beneficial to dance, but to children, as well.

Völckers: Absolutely. I don’t want to instrumen talize dance by saying it would make school children better at maths. But dance and music can help children from different cultural back grounds find common ground with one another more easily than say, reading a work of Schill er together. Not to speak of getting a better sense of their bodies. As we know, our society is fixated on the body we have to be slim, goodlooking…

Kohse: …and we’re totally paralyzed! We try to emulate the images we make for ourselves. And as soon as someone begins moving, we’re em barrassed.

Völckers: That’s about right. We can even observe how ten-year-olds store limitations and general ly negative experiences in their bodies. With adults, it’s especially striking how clearly their posture and gait suggest the baggage they carry around with them. And they’d rather not show their bodies at all, if possible. Small children dance without inhibition but as soon as they realize that it might make them look ridiculous, they stop. And I believe, if we guided them to dance at an early stage, children would like their bodies more. If our experience with the body is positively influenced, we can appear more selfconfident in any situation.

Kohse: Dance in school doesn’t Berlin have that already? Perhaps not as a subject in itself, but as workshops for school children, offered by choreographers?

Völckers: Yes, that’s the TanzZeit project, ini tiated by the dancer Livia Patrizi in 2005, which has proved extremely successful. Looking back at the past decades, very little has happened in Germany on the whole. For the simple reason that the dance field has hardly any infrastruc ture to speak of. There’s also no regular dance training at the university level as there is for music, for example. Of course, there are ballet schools. But we’re not talking about the dance en pointe. We’re talking about having a sufficient number of dance educators who regularly teach sequences of movement at schools and can initi ate an aesthetic discussion about them, as well. We have to create a system of distribution that provides comprehensive coverage to all schools. The Dance Plan in Munich is working on it, the Berliners have established a rather good programme thanks to TanzZeit , the work in Düsseldorf has been intensified through the Dance Plan , and in Frankfurt/Main, they are just starting out. Of course, each city has its own method. However, an association has just been established the National Association

of Dance in Schools which will serve as their network and represent their interests. And now the goal is to develop curricula, start pilot projects, introduce new degree programmes at uni versities…

Kohse: …which the Dance Plan in Frankfurt has already achieved, for example!

Völckers: When the Federal Cultural Foundation started the Dance Plan Germany , went to the cities and told them we’d give them money if they could raise the same amount to jointly get something off the ground that would help dance on the whole, the first things they created were local educational programmes. For danc ers in Berlin, where an interdisciplinary univer sity dance centre was established at the Univer sity of the Arts. Or in Dresden where the Palucca School, the Semperoper ballet and the Euro pean Centre for the Arts Hellerau collaborated to get young dancers working with experi enced choreographers. In Potsdam and Ham burg, choreographer-in-residence programmes were created. As I’ve mentioned before, dance education programmes for school children were developed in Munich and Düsseldorf. And in Frankfurt and Giessen, master’s degree pro grammes in Dance Education, Choreography and Performance were introduced. Dance schol ars are developing new teaching models in Essen, and in Bremen, the North German Dance Conference invited numerous dance companies in the municipal and state theatres to network with one another.

Kohse: What will happen to all these projects when the Foundation’s funding programmes wind down at the end of next year?

Völckers: The dance artists in the Dance Plan cities have already begun lobbying. They’ve learned that they’re capable of achieving their goals and obtaining financing when they work together. When we step back, we’ll see how and to what extent they’ll make use of these skills. If it all dissipates, then we have no choice but to admit that the measures failed. But if something remains or something new develops from them, then we can say they were successful.

Kohse: So after this period of intensive impetus and development, the Federal Cultural Founda tion is leaving dance to fend for itself on the free municipal subsidy market?

Völckers: Not entirely. I’ve gotten the impression that our trustees and board members have be come more accustomed to the idea that we have to promote dance. But nevertheless, I’d like to consolidate dance to such an extent that there’s no going back. Establishing a network, as the Dance Plan has, represents an important step in this direction. Furthermore, it’s obvi ously very important to support the independ ent scenes, because we need their artistic impuls es. We’re still doing too little in this area, per haps because we in Germany have a well-func tioning institutional infrastructure in compari son to other nations. In addition to the dance ensembles at theatres, there is a large pool of artists who wish to work freelance, but require reliable financing nonetheless.

Kohse: Are there any dance institutions in other countries which you find exemplary?

Völckers: The ballet at the Paris Opera is sensa tional. They have the Corps de Ballet with over 150 dancers in a venue of their own the Palais Garnier. The director Brigitte Lefèvre has culti vated the enormously large cultural heritage of dance and developed a kind of repertory. At the same time, she invites contemporary pioneers like Jerôme Bel, Merce Cunningham and Sasha Waltz, all of whom have developed choreogra phies for the ensemble. This means they have a sufficient number of artists, because they spe

cialize in entirely different movements and styles. In Paris, you can view all of dance history, from the past to the present; it is like strolling through a museum. There’s also the Centre Nationale de la Danse , the main contact for all matters in dance, and the decentralized Centres Choréographiques . It’s just fantastic.

Kohse: Is this what you mean when you say you’d like to consolidate dance?

Völckers: I cannot yet say whether what we’re de veloping for dance right now will be what we should invest in over the long term. What I can say is that our work will focus more on the art, on the history of dance and its repertory. We should never forget our traditions! And I also think it’s regrettable that the areas of ballet and New Dance are so institutionally separated. In my opinion, cultural policymakers should work in a meaningful way to create connections be tween the two.

Kohse: The Dance Plan has already set the stage for this with the Dance Education

Biennial Völckers: Yes, it was really difficult to get the uni versity biennial off the ground! But last year, the graduating classes of all ten dance schools in Germany finally got together in Ber lin. And these ten schools are very different, ranging from the most gruelling ballet training in Munich to the complete openness of the new degree programme at the University of the Arts.

And for several days, all these young dancers, who would soon be entering the German dance market, met, talked about dance and performed together. Marvellous! Next year, the biennial will take place in Essen.

And then there’s the Dance Plan project that will virtually combine all the dance archives in to one. There’s the second Dance Congress coming up the first of which we organized ourselves which continues the tradition of the historic dancer congresses of the 1920s and early 30s. And there’s the transition study which examines how dancers can enter new oc cupations at the end of their dancing career.

Kohse: I can see you’re sorry that the Dance Plan is coming to an end.

Völckers: Yes! It will mean one less support centre for dance. Many people who want to learn something about dance in Germany call up the Dance Plan first. It collects a wide range of information, provides funding, offers small scholarships, etcetera. It’s really too bad that it’s ending. But, unfortunately, the Federal Cultur al Foundation is not a national dance agency.

Kohse: And where would you say German dance is positioned internationally?

Völckers: Right at the top. It has a strong expressive dance tradition. And just ask the Goethe-Institut and they’ll tell you that Pina Bausch, William Forsythe, who works in Germany and whom I consider German now, and Sasha Waltz are truly successful exports. Everyone wants to see their works. And in a globalised world, dance is the form of expression par excellence as local and international influences combine in innovative ways which will benefit everyone in the future. If dance artists took this to heart once and for all, they’d be much more self-confident.

current dance projects

dance congress 2009 No Step without Movement! is the motto of the Dance Congress 2009 which will take place at Kampnagel in Hamburg from 5 to 8 November. This year’s congress will examine current issues concern ing the state of contemporary dance. For example, how can we improve the production conditions, funding structures and marketing strategies for dance in the long term? How can we more strongly anchor dance in our edu cational canon and research efforts? How is dance history being written to day and what will dance archives look like in the future? An event funded by the Federal Cultural Foundation in cooperation with Kampnagel, K3 — Centre for Choreography Dance Plan Hamburg and the Centre for Performance Studies at the University of Hamburg. Supported in part by the Hamburg State Ministry for Culture, Sports and Media and the German Research Foundation ( DFG ). www.tanzkongress.de

choreographing you Art and dance of the last 50 years Choreograph ing You is the first exhibition that examines the interplay between art and dance in terms of choreography – of inventing and shaping motion. The cho reographic concept is to make the visitors’ motions an intrinsic component of the works, without which their intention could not be realized. The exhibition will display a wide range of works, beginning with Bruce Nauman’s corridor pieces from the 1960s to recent works like Scattered Crowd (2002) by William Forsythe. Artistic directors: Stephanie Rosenthal, Nicky Molloy, André Lepecki FR / Artists: Jerôme Bel FR , Pablo Bronstein UK , Trisha Brown US ), Alain Buffard, Rosemary Butcher UK , Boris Charmatz ( FR , Gustovo Ciriacs, Marie Cool FR ) and Fabio Balducci I , Vincent Du pont, William Forsythe US , Simone Forti US ), Allan Kaprow US ), Latifa Laâbissi FR ), Thomas Leh men, Marcela Levi BR , Kate Mcintosh ( NZ , Ohad Meromi IL , Mathilde Monnier FR , Robert Morris ( US , Jennifer Nelson US , Miguel Pereira AR ), Robin Rhode ZA , Xavier le Roy FR , Peter Welz, Franz West AT / Kunsthalle Hamburg, starts May 2010 followed by an exhibition at The Hayward, Southbank Center, London GB www.haywardgallery.org.uk

oedipus rex International dance project With her upcoming production of the operatic oratory Oedipe Roi by Igor Stravinsky and Jean Cocteau, the Argentinean Constanza Macras ventures into new artistic territory. In her version of this modern classic, Macras will apply tools of modern dance thea tre while retaining the original principles of the piece, i.e., rejection of stage realism and psychological interpretation. Oedipus Rex is a co-production by the European Center for the Arts in Hellerau, the Teatro Comunale di Ferrara and the MESS Sarajevo festival. Artistic director: Constanza Macras AR / Musical direc tor: Max Renne JP Dance: Chiharua Shiota JP ) / 19 21 Nov. 2009 European Center for the Arts, Hellerau, Dresden www.dorkypark.org

le bal. allemagne A German-German history

This dance theatre project adapts an idea first dramatized in the now legendary theatre piece Le Bal des Théâtre du Campagnol from the 1980s. Arranged in chronological order, the episodic scenes feature people in a ballroom, each of whom represent a different generation as expressed by their personal stories, their clothing and the music, to which they dance. The original French version has been in ternationally adapted many times. This new adaptation by Nurkan Erpulat and Tunçay Kulaog˘lu will present the complete German history on stage, starting from the early post-war years of German division to the Peaceful Revolution of 1989 Artistic director: Shermin Langhoff / Director: Nurkan Erpulat TR / Composer: Enis Rotthoff / Author/dramaturge: Tunçay Kulaog˘lu ( TR / 1 30 Mar. 2010, Ballhaus Naunynstraße, Berlin www.ballhausnaunynstrasse.de

colombia festival Theatre festival and lectures In 2010, when the next presidential election coincides with the 200th anniversary of the country’s declaration of independence, Colombians will surely make world headlines as they take to the streets to celebrate and protest. To mark this occasion, the Theater Hebbel am Ufer has asked Colombian artists whether they see any reason to celebrate. Two dance companies and three theatre groups will increase public awareness with performances that reflect the perspec tive of artists who critically view the socio-political reality of their country and articulate the hopes and fears of its inhabitants. Artistic directors: Gustavo Liano CO ) , Kirsten Hehmeyer / Artists: Manuel Orjuela Cortés CO ), Rolf & Heidi Abderhalden CO , Tino Fernandez CO ) and others / 19 Apr.– 2 May 2010, Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin www.hebbel-am-ufer.de

choreographic captures 2009 2011 Combining choreography with art films in commercial clips In 2008 an international competition called on choreographers, film and media artists to submit Choreographic Cap tures – a new short film format that explores various forms of representation and realization of choreography and art film. The project Choreographic Captures 2009 2011 will continue developing this successful prototype for three more years. In addition to holding an annual professional competition, the project’s website will be expanded into a multilingual, interactive platform for choreographic short films from around the world. Artistic director: Walter Heun / Jury members: Andreas Ströhl, Thierry de Mey B , Frédéric Mazelly F / Film screenings throughout Europe and interactive online presentation, 16 June 2009 –Nov. 2011 www.choreographiccaptures.org

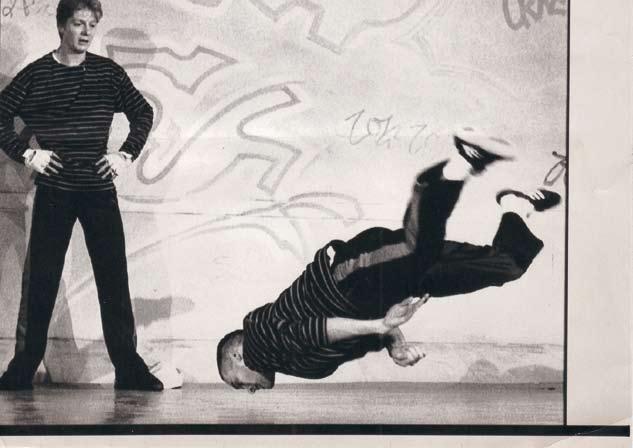

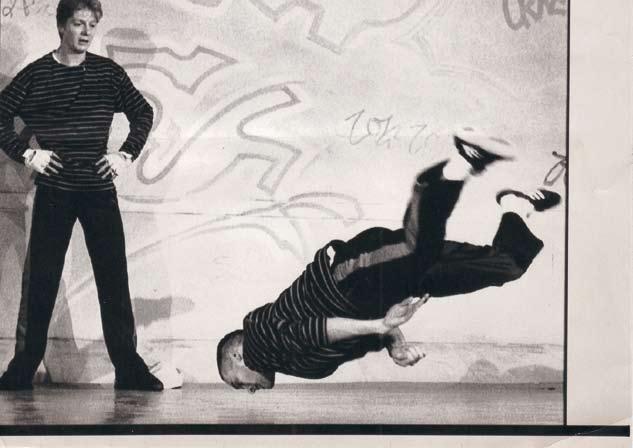

1 The Jivers 1984, photo: Gabriel Weismann [C] 2 Break Dancer, undated, photographer unknown [C]

3 Flamenco Los Molineros, undated, photo: Regina and Angel Martinez [C] 4 no information given [C]

5 Tap Dance, undated, photographer unknown [C] 6 Dorothee Parker and Ramon, undated, photo: Sieg

1 The Jivers 1984, photo: Gabriel Weismann [C] 2 Break Dancer, undated, photographer unknown [C]

3 Flamenco Los Molineros, undated, photo: Regina and Angel Martinez [C] 4 no information given [C]

5 Tap Dance, undated, photographer unknown [C] 6 Dorothee Parker and Ramon, undated, photo: Sieg

1 Die Pleiße Dohlen in Myrthen , undated, photo: Andreas Birkigt [C]

1 Die Pleiße Dohlen in Myrthen , undated, photo: Andreas Birkigt [C]

ultraslim and supersmar t ?

dance as body, brain and social doping

with all the risks and side effects

After his tragic death, everything was suddenly forgotten. The scandalous escapades faded in the posthumous halo of the iconic entertainer who wrote several legendary songs, catapulted a dozen mega-sellers into the top forty and filled entire stadiums. But above all, he had been a phenomenal performer, a dancing humanoid with breathtaking body control.

In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. He had tried everything to conquer his body, to wrestle it down and redesign it to an ideal image. Michael Jackson became a victim of that cosmetic eye (Martina Pippal) that keeps correcting nature until there is nothing left. Instead of enhancing, the King of Pop radically erased his background, his original contours, and in the end, himself.

It is quite revealing that Jackson turned out to be a brilliant dancer and that no obituary failed to mention his legendary physical agility. Since dance descended from the divine heights of its sacred past into the low-lands of everyday life and established it self as a majestic nimbus and school of plebeian etiquette, its most elegant business has focussed on controlling human nature (Rudolf zur Lippe). Dancing supposedly make us bet ter people well-mannered, morally decent and of pure mind because it frees our bodies of obscene instincts. This was the teaching of Renaissance-period dance masters, and despite libidinous temptations, we have proven to be worthy followers of this line of thought today. According to a long-held belief, those who dance keep in shape, stay healthy, are more intelligent (as their motor skills are better trained) and are more socially com patible (as they are community-tested).

This would give us reason to be happy if it weren’t for the dance elite who know more about dance because it’s either their profes sion or they deal with it on a professional basis. This group has no desire to sing the praises of dance in unison along with brain researchers, body sociologists, educational scientists and social pedagogues. Some have expressed a suspicion that dance is being exploited, crossing the fine line between art and commerce, as if they fear their own dethronement. Those who work with amateurs, whether they be school classes, patients of dance ther apy or tango fanatics, are clearly in the second row, far behind the artists and their PR agents who insist on the autonomy of dance art. Apart from a handful of ballet companies in Germany which work with amateurs in theatre and adventure-based educational projects, most of the dance scene has reacted to this trend with capricious mistrust.

This insistence on professionalism is a symptom of weakness.

On one hand, it reveals that the self-regard of dance artists re mains underdeveloped, and on the other, indicates long-term damaging professional blindness. If we take a look at dance train ing schools and their graduates, we discover that most of Europe, half of America and Asia are churning out more young

dancers than Germany. This is not something to lose sleep over, but it does speak volumes about the fact that dance in Germany, like classical and music theatre have made great strides toward becoming recognized independent genres, but are far from achieving equality with their sister arts.

The dance community has remained relatively small due in part to its exclusive airs. Apparently word has not yet gotten out that the performing arts rely on an expert audience, one familiar with its codes and traditions. While most in school have learned about Goethe, Schiller, Benn and Beethoven, only the inner circle grosso modo are familiar with Mary Wigman, Rudolf von Laban, Vaslav Nijinsky and George Balanchine. This is surprising as dance has been a part of the educational canon for centuries. The courtiers of Versailles were as familiar with dance as the German bourgeois of the 19th century. Furthermore, ballet and ballroom dance grew from the same abso lutistic roots and were closely related for a long time in terms of their language of movement. People who witnessed a spectacle dansé 150 years ago were usually able to figure out its structure through experience alone future housewives were required to study simple pirouettes along with piano playing, and their spouses were not only expected to demonstrate academic and business prowess, but had to fence in duel for their honour and dance in the ballroom for their reputation.

Thank God this fortress of education has fallen. Thank God, be cause it represented the desire for distinction in an aristocratic social architecture which extended the class-conscious bourgeoi sie for its own benefit. Secondly, it reduced dance to one particu lar aspect its social-technological value. Everyone’s personali ty underwent development that was forced to adapt to the order of the day, and dance played a particularly important role as it promised to tame the one anarchical element in society, namely the human body.

This is where contemporary critics deliver their strongest argu ment against expanding the dance zone. Forcing the dancing individual into a social corset would be a triumph of social doping over the aura of art dance reduced to an educational tool. Its argumentative spirit would be extinguished and its independent mission within the matrix of economy, power and culture (Max Weber) would be diluted so far as to be unrecognizable. Which strategy makes sense then if we wish to avoid making dance a means to an end, yet also expand its field of impact for no other purpose than for the sheer will of self-preservation? Per haps it would be helpful to discuss several working hypotheses based on three examples body, society and education, exam ine the meaning of dance and the questions which we hope dance can answer for us.

The fundamental phenomenon which dance has always dealt with is the human body. Beyond the temple districts of antiqui-

ty, dance has always been about the art of discipline, inserting oneself into pre-determined, choreographed forms. Since the absolutistic pomp fizzled, Die Arbeit am eigenen Körper [Working on One’s Body] (Martina Pippal/Bernadette Wegenstein) has become increasingly significant, and Projekt Körper [The Body Project] (Waltraud Posch) has made the present day a maxim for everyone. Whoever is self-confident, takes cares of his appearance and assesses himself in anticipation of how one’s environment will judge him. »Self-develop ment is a must« (Posch), yet the inner voice is just one of many. Like on stage, the external view is a decisive factor that deter mines the success or failure of one’s (self) presentation.

Unlike the 18th and 19th century, our view not only scans the fa cade, i.e., one’s clothing and behaviour, but focuses on the body itself. The beauty cult has created an ideal which despite sup posed tolerance toward other forms of appearance and lifestyles is strongly judgemental. Those who wish to be successful in social circles should appear slender, agile and seemingly ageless. Indeed, the popular ideal has grown increasingly similar to the requirements that have long been a fact of life for dancers. Forty-year-old performers retire, cellulite in tights is a no-go, and weight problems prematurely end the most promising young ca reers.

In a way, dance is a kind of permissible body doping, but comes with the price of poor visibility natural processes of life, aging, fluctuations and loss of physical strength are simply blocked out. This lack of perspective has become a way of life among professionals and has affected their social disposition. If all you see are very young, attractive people on stage who, in fact, are the product of a selection principle you will eventual ly regard such people as the norm. If dance truly wants to avoid being exploited, come across as subversive and overturn aesthet ic conventions, it will also have to be put to the test for better or worse. Is it true that dancers always have to be young and flawlessly beautiful, or could it be that with age they find new ways of expressing themselves, and that by distancing ourselves from the athletic type, we might discover untapped creative po tential?

Dancers like the hunchbacked Raimund Hoghe, whose appear ance starkly contrasts the mainstream, shows us that dance, like all art forms, does not strive to be mainstream, but to be unique, to break with the conventions of perception and rattle our usual viewing patterns. As far as the issue of age is concerned, the discontinuation of a company that consciously worked with dancers over forty namely Jirˇí Kylián’s Nederlands Dans Theater III sheds a revealing light on the dance scene. Instead of taking advantage of the life and performance experience of older dancers, the scene recycles them after a short time, and thus, pays tribute to the ever-spreading post-industrial

mania of replacing older employees with younger ones. What’s possible in art can’t be wrong in business. A more critical reflec tion on its actions and usual market mechanisms would do dance more good than simply allowing its well-oiled machinery to con tinue running as usual.

For the body, dancing is certainly one of the most recommended activities (as long as one doesn’t push oneself to top perform ances levels, which requires absolute caution to prevent injury). Dance strengthens the muscular and cardiovascular systems, en hances one’s state of mind and coordination, and provides ex pression to the joy of moving. This was common knowledge to the ancient Greeks, and modern-day writers haven’t grown tired of disseminating this knowledge among the reading public. However, this does not necessarily refer to a person’s body as such, but rather the socially and economically adaptable body apparatus. Its applicability remains the measure of all things. However, dancing as a way of consciously controlling one’s body which modern-day discourse describes as authenticity was not intended in this scenario.

The Swiss journalist Christina Thurner recently argued that the pressure for dance to adapt was lifted for only one moment in dance history at the dawn of classicism. Everything that hap pened before and after referred to an ideal, influenced by the im age of the social formation of the time. It was never the emanci pation or delimitation of the ego, but rather the restraint of in stinct, the aspiration to achieve and self-control that have always advanced the process of civilization.

This trinity is what makes the dancing body so unique and seductive be it at the theatre or disco and when bundled, forms the noble contrast to sex, drugs and Rock’n’Roll. One stays clean regardless of how lasciviously one dances. It’s like adminis tering clinically pure social doping, so to speak. The paramount example of such a dancer is none other than Michael Jackson. No matter how many times the moonwalker grabbed his crotch and loaded every gesture with predatory eroticism, his entire ap pearance remained nonetheless asexual and aseptic, and in the end, cannibalized his flesh. For as Jackson dissected his every movement into its individual parts on stage, he dissected himself behind the scenes, patched up a new silhouette of himself with

the help of plastic charlatans until he had deformed his appearance to such a degree he could finally recognize himself.

Jackson created himself a truly self-made man and dance became a language that in many ways communicated the same message: Noli me tangere. He drove the human aspect out of his dancing and simultaneously raised his body to superhu man-unhuman heights, making himself, in effect, untouchable. This steely untouchability, protected by the armour of his sin ewy-looking costumes, illustrates the risks and side effects of the health and self-realization ideology of modern times. Where na ture fails to deliver, the pharmaceutical industry and celebrity surgeons are ready to step into the breach. After all, nothing is more valuable than body capital which is the starting point of »passionate self-modelling« (Posch) along the lines of »show me your body and how it moves, and I’ll tell you who you are!« This representative sell-off contradicts the dignity of every art and therefore, collides with how dance sees itself. But how can it counter this? First, by critically examining its own capitalizing tendencies and turbo maximization, or in other words, its fascination with physical feats and intoxicating speed. In terms of technique, timing and precision, contemporary dance has reached a level that simply overwhelms us. But no longer pro vokes us. What we see astonishes us to the utmost, although or perhaps because we can keep it a safe distance away from us. It’s not without reason that the person who significantly influenced this development has meanwhile slammed the brakes. William Forsythe, the doyen of postmodern dance, has turned away from the expansion of the body cult. Instead of endlessly increasing his arsenal of the arabesque, he arranges splinters of thought in succession which fill themselves with fibres of movement and not the other way around. The effect is that, beyond biomechanical virtuosity, we witness the sudden spark of humanity and not in an anecdotal sense, but rather an anthropological sense. This metamorphosis is a result of what we can briefly sum up as critical awareness and aesthetic education. In current education al debates, dance has begun to play an increasingly important role as a community-builder and neuro-activator. According to human scientific research, every rhythmic movement helps cali brate the mind, and dance classes in school help invoke team spirit which later keeps the economic wheel rolling. Despite the

fact that cost-benefit calculations are being used here as if to say, the school administration will only pay for what is useful the dance world should ask itself what role it can play in educa tion and the community. And even this isn’t enough to turn things around.

If it’s true that motor skill is pure brain doping, then young future dancers are true wunderkinder. The dance profession hardly takes advantage of this fact, however, and has failed to provide sufficient general education or professional opportunities out side its scope of activity for dancers before or after their career. This constriction, which is often concealed by the cute euphe mism not a profession, but a calling, takes its revenge both on the individual and the image of the entire branch. Those, who believe they are called to the dance profession, need not care an iota about their reputation. And so they keep company among themselves in a dreamy hortus conclusus of art.

This is fine for as long as times are idyllic and no clouds of crisis darken the horizon. As soon as the vultures start circling above the empty municipal coffers, the first thing they devour as we’ve seen in past decades is dance, which is and has always been the weakest link in the German theatre world. The only way to prevent this is to tear down the picket fence and use the guer rilla tactics of underground networks. Art rebellion or no in stead of dying in beauty, dance will have to join all those who call the tune in the society of knowledge. And by this, I not only refer to the usual suspects, like dance experts, designers and thea tre pedagogues, but also mathematicians, linguists, doctors and biologists who have just begun to recognize the knowledge con tained within the field of dance. Obviously the sister arts are deeply rooted in the educational terrain, and the only way for dance to catch up is to put down new roots over a wide area. Sec ondly, dance must go hunting outside its back yard and pounce on every aesthetic and existential issue that is crucial to society. Exclusion, migration, the demographic pyramid, environmental collapse and the digital revolution those who prefer their peaceful slumber will probably fall into a coma and end up like Michael Jackson a zombie with ultraslim legs.

nomadic dance

moving between the cultures

by gabriele brandstetter

the universal language of dance?

We’ve long become accustomed to those annual festivals which present the newest productions by dance companies around the world to enthusiastic audiences. Dance and performances seem to have effortlessly embraced the role of the ambassador moving across boundaries in a globalised festival culture. They receive sup port from national cultural institutes, like the Goethe-Institut. This has more to do with the fact that promoting dance performances in co operation and exchange is much easier than learning a foreign language. Does this mean that dance is a language we understand no matter where it comes from? The tendency to regard dance as a universal language is old and has been supported by philosophical and anthro pological arguments in writings since the 18th century. But wait until a European audience watches a performance of a traditional Japanese Nô dance, and it’s suddenly obvious that the movement and gestures of the body are any thing but universally interpreted and under stood. We have nothing to gain by simply trans ferring the patterns of perception from our dance culture onto another. Perhaps what is most enriching and challenging is the experi ence of difference in our encounter with other dance cultures. Dance, in its diversity, embod ies the knowledge of a culture in a specific way non-verbally as a movement of the body that shapes space and time artistic or sacred, ritu alistic or athletic, soloistic or collective. Dance alters its form during the process of cultural transfer, in that it practically and literally crosses borders.

Pina Bausch, whose productions with the Tanz theater Wuppertal toured countless cities and festivals worldwide, had always played on her experiences with other cultures and incorporat ed them into her choreography, for example, the melancholy the saudade of Fado, the ges ture of the embrace in tango, or the atmosphere of southern Italy in Palermo , Palermo Conversely, the older dancers in Pina Bausch’s Kontakthof remarked at how differently audiences from other countries reacted to the performances. »What makes the French, Dutch or Italians laugh, what touches them or how they show their joy« is not the same.

Because dance performances are not based on universal forms, but are transported by histori cal and culturally specific local attitudes concerning the body, interaction and rhythmic move

ment, they have the potential for transforma tion. It’s also true that globalisation promotes processes of interactive metamorphosis, result ing in more and more dance hybrids which incor porate the movement and performance tradi tions of different cultural contexts. A tango is a tango, but in Helsinki it’s a slightly different tango than in Buenos Aires. The same, but dif ferent.

Such hybridisations are not merely the result of more recent economic, touristic or media-based networks in our global village. We can find ex amples of interweaving in early colonization movements, such as the integration of exotic Asian trends in European dance around 1900, and most recently, the body techniques of mar tial arts in contemporary Western dance. Trans fer also occurs in the other direction; the trans formation of German expressive dance influ enced the development of the Japanese Butoh dance theatre. Dance is a nomad that leaves a trail which others follow or brush away.

dance is a nomad

Its nomadic migration in Europe was already underway during the Renaissance when the basse danse, which had been circulating among the royal courts of northern Italy and Burgundy, became more refined and its expressive forms more sophisticated, after which time it moved on to England. Dances like the allemande, for example, with a name that reveals its national provenance, changed in its new environments and spawned regionally specific performance methods and dance forms. The discourse re garding the foreign and the familiar, hybridisation and globalisation, doesn’t fully apply here because it remains rooted in the ques tion of origin and authenticity, and disregards its own complexities. Dance would have never developed its nomadic character if ballet mas ters, choreographers and dancers hadn’t been willing or naturally inclined to lead a nomadic life. Looking back at history, it was perhaps co incidence or even necessity that caused dance the art of movement to move ever further outward, crossing territorial, cultural, artistic and social boundaries. Jean Georges Noverre, one of the founders of dramatic dance in the 18th century, worked as a choreographer and in structor in Lyon, Stuttgart, Vienna, Paris and St. Petersburg. Carlo Blasis, the inventor of today’s dance system of (classical) ballet, travelled back

and forth between Milan and London. And Marius Petipa, the choreographer of such clas sics as Swan Lake and Nutcracker , left the Opéra in Paris to work at the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg. And the dance star Fanny Elssler performed at all the major thea tres in Europe and went on tour through Ameri ca in the first half of the 19th century. Although that was quite exceptional, travelling was a ne cessity and fact of life for most dancers in the 20th century. The nomadic life, characterized by living and working in foreign places and cultur al environments of one’s own personal choos ing, also came to include the experience of emi gration and exile during the 20th century. The brilliance and aesthetic innovations of dance groups like Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russ es was contrasted by the other group of emi grants, the best dancers and artists of the Mari insky Theater, who were forced to cut off all ties with their home country, and discovered (or in vented) the familiar on the stages of the world in never-ending tours and guest performances. We notice the nomadic aspect of dance in its continual movement between local and cultur al spaces. Yet its transformational potential is also evident in its movement between social classes and spheres. It is capable of shaking up socially divided areas and erasing the divi sions that separate the generations. For example, in response to an aging society, opinion poll sters, economists, insurance experts and politi cians address the problem of generational fairness with appeals for solidarity. And then there are those well-meant events for senior citizens and youth clubs which actually do more to contribute to than dismantle generational segregation in society. But certain forms of dance, such as the popular dance tango or Pina Bausch’s choreographed performance of Kon takthof , have demonstrated a different, re laxed and fun way to get the young and old to interact. Dance offers us an alternative the possibility of encounter without the hierar chism and discrimination of social measures.

dancing together kontakthof

The huge, long-lasting success of Kontakthof can be attributed to the fact that this con vincing artistic event shows us something that could never happen in normal life. Developed in 1978, the choreography premiered in 2000 and continued running for several years on tour

in a version with amateur dancers over 65. Ac cording to Bausch, it was her wish to entrust older women and men with a great deal of life experience with such a theme. And what is the theme? Kontakthof is a place of encounter, »where people meet to find con tact. To show themselves, to refuse each other. With fears. With desires, disappointments. Frustration. First experiences. First tries. Tender moments and what can come of them.« This is how Pina Bausch described the theme in her own words. And in 2008, thirty years after its inception, she introduced a new version of Kon takthof with teenagers over 14. The piece, the scenes and the composition are all the same, but change as it crosses the generations, because young and old have very different experiences to communicate. The piece is primarily about dealing with the possibilities and limits of one’s body which the dancers experience and experi ment with, in joint effort, in moving dialogue with others and in the encounter with one’s de sires mirrored by others. A process that is both frustrating and comical, tedious and delightful. A piece like Kontakthof is capable of heightening our awareness that it’s possible to find other categories of beauty and agility not the show of mastery, not the perfectly sculpted bodies with their promise of age lessness, not the corrective surgery or phar maceutical optimisation. Contrary to politics and society, it doesn’t promote the concept of compensation or sharing the burden equally among the generations, but rather acceptance and the lightness of being with no age limit.

tango as a way of life

You could perform Kontakthof all night long, Pina Bausch said shortly after it premiered. In the same way Kontakthof established its success as a spectacular evening performance, tango is celebrated as a popular way of life. Tan go dance evenings, called milongas, seldom be gin in Buenos Aires before midnight and last until 4 am all night long, couples mov ing together in close embrace. In the wood-pan elled, decadent rooms of the Confíteria Ideal under golden chandeliers, or in the base ment of La Viruta where beginners and ad vanced dancers intermingle, or in the gymnasi um-like Sunderland club where long-time milongueros celebrate the traditional tango, it’s amazing how tango has established itself as a

place of contact for both young and old, accept ed by 20 -year-olds and octogenarians alike. At the Baile de Campeones tango competi tion at Salón Canning, a young couple, slender and taut, step onto the dance floor. The woman, like many female tango dancers, is clearly trained in ballet. It is a pleasure to watch the cou ple dance, aesthetically, musically with sweep ing figures and flourishes. They are followed by a couple, both of whom are well over seventy and more corpulent. The moment they take their position in the tango embrace and find their rhythm together, one immediately senses an extreme intensity that lasts the whole three minutes of the dance dancing for personal and mutual pleasure nothing spectacular, no prepared choreography in their sequence of steps, just a simple connection to one another, united and absorbed in the music. Tango is a dance of endless and unpredictable possibilities an improvised dance, the form of which is determined by the couple’s combination and sequence of steps at the moment they begin dancing, and then evolves further according to their needs and possibilities. This unpredictabil ity is what makes tango so fascinating. And the intimacy of the bodies in embrace makes it a dance of the heart.

Not only does the emotional aspect of touch in tango create a connection between generations and social cultures. »Tango is a hybrid dance for a hybrid mass of people,« explains the Argen tinean researcher Horacio Salas. Historically speaking, this popular dance was an amalgam of different forms of music and movements from various European, African and South Ameri can cultures which the immigrants in the Rio de la Plata region combined at the end of the 19th century. Its nomadic heritage enabled tango to transform, yet preserve its identity as it mi grated from Buenos Aires to the major cities of the world and back again.

Enrique Santos Discépolo, one of the most influential tango poets, once said that tango comes from the street. That was why he liked to walk the streets of Buenos Aires and listen to the soul of the city. This is also a journey through the urban spaces of loneliness, feeling uprooted, saying goodbye, the struggle, the end of love, all of which is expressed in tango.

Tango is a memory bank of feelings and experi ences which model social reality in a very spe cific way. It can offer traditional gender roles a

new way of understanding the concept of lead ing and following. Or it can be the joy of experimenting in Tango Nuevo, or the fascina tion with the unconventional ZEN Tango, or perhaps the Contact Tango which brings the in compatible together. These transformations are made possible through the use of tango’s cul tural characteristics, which, in view of cultural differences, become all the clearer. Because tan go is more than merely an artistic sequence of steps and can only be tango when it conveys the feelings and experiences of life, it takes on a unique appearance when danced in Berlin, in New York, Tokyo or Helsinki. In Wuppertal with Pina Bausch, it’s perhaps at its most unem bellished.

»what are the benefits of tango?«

In her piece Bandoneón , which premiered after the Tanztheater Wuppertal completed a South American tour, Pina Bausch transferred the atmosphere of tango into the scenarios of her choreographic work based on the questions: »What are the benefits of tango?« and »At what point can we begin dancing it?« In the latter, she wasn’t referring to the prescribed steps and forms of a dance, but rather those inexplicable moments when movements take shape and tell us something about people’s feelings. Return ing from the tour with a myriad of new impres sions, Raimund Hoghe (dramaturge under Pina Bausch at the time) remembered how some thing had broken open and become uncertain with regard to one’s dreams and reality in life. In this sense, tango was not the theme, but the impetus for examining what is foreign and strange in one’s own life. Not a single tango is danced in Bandoneón in order to respect the special character of the other culture and to avoid the cliché of performing exotic pseudo tangos which could become the dance hits of the piece. Instead, the piece featured tango music from the era of Carlos Gardel, played by a live band, and the melancholy sound of the bandoneón an instrument, invented by a German, which found its purpose and meaning in life in Argentinean tango.

Pina Bausch’s choreography makes tango the medium. It examines the rituals of closeness and distance and searches for those moments when habitual posing ceases and a feeling of to getherness arises scenes in which the dancers

simply stand in position to tango, or wait an en tire tango before reading a poem aloud to the audience. Or a »tango« in altered poses which also reveal pain and inadequacy, for example, when couples meet in a tango embrace, but shuf fle across the floor on their knees. In the back ground, the male dancer Dominique Mercy, dressed in a ballerina tutu, executes perfect pliés (knee bends) over and over. Images of the loneliness of dance training and the difficulties for a couple to move together in unison blend to gether and create an overlap of two dance cul tures ballet and tango. »What are the benefits of tango?« Pina Bausch’s dance theatre and tan go as a popular dance form show us how move ment reacts to cultural and social contexts and simultaneously overcomes its reality-forming power. And though it’s the same, it can also be different. A conundrum, if dance were a univer sal language.

1 2

3 4

previous page Berlin’s highest bar. On the roof of the Eden Hotel, undated, photo: Keystone [C] 1 46th Street Jam from the film Fame 1980, photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer [C] 2 Revue scene, un dated, photographer unknown [C] 3 Exercises 1910, photo: Rud. Gentsch [C] 4 Corps de Ballett in »Giselle« by Heinz Spoerli, Basler Theater, photo: Peter Stöckli [C]

a dream come true is it the story

dancing or the stars? the popularity of dance films