THE PLEASURE OFABSENCEANDASYMMETRY

Ani Kostadinova

Issues in ContemporaryArchitecture

Word Count: 3009

Key Words:

• Minimalism

• Nature - Architecture - Humanity

• Tadao Ando

• Chichu Art Museum

Abstract:

The aim of the paper is to interrogate the response to urbanisation through the lens of Minimalism and investigate the methods pertaining to the ideology in contemporary architecture. With modern cities becoming ever so densely populated and architecture being dominant over nature in those instances, the significance of balance and space is often disregarded. The city creates an offset, which could be argued to have a negative impact on people’s lives, and architecture as the constant which mainly surrounds us could serve as more than just a shelter. We often are at our most vulnerable when engulfed within it, in a way we rely on it. Therefore, architecture could be a source of security, remedy, and harmony. With his practice, Tadao Ando delves into those matters to pose designs that aim to re-establish the connection between humans, architecture, and nature and thus restore the balance in our lives. The notion of Minimalism then is explored through the case study Chichu Art Museum to scrutinize the utilized methods in contemporary architectural interventions and consequently discuss the importance of the ideology in present times.

1. Introduction – Tadao Ando and Minimalism

The post-war period which shaped Tadao’s childhood and set the base for his architectural style saw a shattered world in need of reconstruction. The heavy industrialization influenced a counteractive response in the architect and thus inspired architecture which aimed to restore the connection with nature and impermanence. The deterioration of the urban environment urged Ando to question the aptitude of Modernity, especially the concepts of space and being. As construction projects became scarce due to a fall in the Japanese economy, the new generation of architects found themselves concerned with small-scale housing projects. This later resulted in a shift of the perspective on architecture and design to a more personal approach regardless of the nature of the building’s use. (Nussaume, 2009, p. 29) Tadao’s first spatial prototypes aimed to rediscover the fundamental emotions through chromatic minimalism, he implemented a method of simplification based on the elimination of insignificance. With them, he re-evaluates the principles of Modern architecture and sets the basis for his perusal over Minimalism.

After the War, rationalism, and functionalism became the bedrock of Japanese architecture. In 1960 the Metabolist movement arose as a form of protest against the increasing urbanisation of the coastal region around Osaka and Tokyo and to the country’s westernisation. (Schittich, 2002, p. 34) The Metabolists responded to the urbanisation with futuristic models of the city which were based on pre-fabrication. This resulted in buildings that aggressively defied their surroundings. Following that, the Postmodernism and Deconstructivism fashions as well as the thriving economy, liberated resources which thus led to an overemphasis on original forms. (Schittich, 2002, p. 39) The desire of the clients for unique trade-marks encouraged the architects to break out of a conformist society and resulted in architects further exacerbating the chaos of the city.

Opposing that, Ando has a minimalist approach that re-interpreted traditional building types and rigorously turned its back on the chaos of the city. Contemporary architecture aggravated his anguish, thus, he strived to create minimalist designs which disintegrated within nature and embodied energies of spiritual essence. Furthermore, he presented meditative perspectives through buildings whose sensuous appearance was achieved by brute materials and light. Ando responds to the urban and social situation by trying to heighten the consciousness of the mind and to allow for a genuine experience of the space through clear and simplistic geometrical forms with tension within volumes and surfaces. Inspired by Buddhist teachings, he wanted to bring internal peace and reconnect man with nature. (Nussaume, 2009, p. 164) It could be stated that his buildings are catalysts that channel and energize the spirit of the place. Therefore, the architect focuses not on the object, but the message which architecture embodies.

The ceaseless process of urbanisation continues to disturb the balance between nature, architecture and humanity. The intensity of a place, such as a metropolitan, eliminates the peace that accompanies a natural setting and thus deprives us of such rustic pleasure. However, a request for primitive architecture is not implied here, rather this essay aims to provoke an appreciation of absence and asymmetry in design and reflect on the benefits of those methods. Furthermore, this paper focuses on discussing the methodology of minimalism and scrutinizing the methods and their importance in contemporary architecture. With that aim, Chichu Art Museum is used as a case study, since Tadao Ando has devoted his life work to studying and divulging the connections between nature, architecture, and humanity. Thus, Minimalism refracted through Ando’s design is analysed in order to interrogate how a balance between nature and architecture could account for humanity to experience peace and harmony.

2. Minimalism

The term Minimalism has been generalized in its contemporary use. Thus, its meaning has become less precise. The popular aesthetic is known to be based on simplicity, the use of a monochrome pallet and cold lighting. Geometric rigour, formal restraint and conceptual purity also pertain to the popularized notion. However, the art of Minimalism finds deeper roots. Nature, as it is the foundation for the architectural forms and construction materials of Japanese buildings, plays a major role in understanding Minimalism. Despite the constant threats of natural disasters, the Japanese did not develop a hostile response to nature, their architecture is rather respectful and shows reverence to that overwhelming power. This respect for nature is at the basis of Buddhist teachings. The discipline takes the philosophical side of Indian Buddhism and refracts it through the prism of practicality. (Locher, 2010, p. 47) It consists of finding enlightenment or Satori in Japanese, which is found in our daily experiences such as drinking, eating, sleeping, etc. (Suzuki, 2018, p. 16) It is emancipation, moral, spiritual as well as intellectual, that teaches self-control to allow the mind to be unrestricted from complexities and attachments and explore the world of senses. As the background for our daily activities, architecture should embody a sense of tranquillity and harmony. A grandly constructed building then would be too obtrusive an object to keep company with the surrounding entities of nature. (Suzuki, 2018, p. 338) Such an imbalance between man-made and nature then could lead to a disbalance in human life, thus affecting one’s mind and spirituality. In Japanese Sabi, translates to ‘solitude’ or loneliness and it consists of rustic unpretentiousness or archaic imperfection. That appreciation of the artistic and yet simplistic, the seemingly effortless, is derived from Zen Buddhism.(Suzuki, 2018, p. 24) Therefore, beauty in a form of imperfection must be embodied. The asymmetry then is typical for Minimalist architecture in that sense. Such a feature is often found between the form of the building and the landscape or within the use of materials. Consequently, Minimalism takes root in the Buddhist teachings and as an aesthetic, it avoids abstract concepts. For the ‘Zen experience’ to occur there is a need for absence. The ideology shows restraint from excess and compression of form. Minimalism stems from the relationship with its immediate surroundings and materials - reflections and textures; and strives for direct personal interaction with the architecture. (Asensio Cerver, 1997, p. 9)

The Minimalist style also takes inspiration from natural phenomena and human movement. Otherwise known as feng shui, geomancy is defined as aesthetic science which deals with the spatial arrangement of a building in accordance with the hidden forces of the earth. (Locher, 2010, p. 48) Of such consistency is the direction a body of water follows naturally or the path which feels the easiest to take down a hill. Ando himself states that he did take such strolls around the island to study the natural patterns and understand the aura of the land. (Blaser, 2001, p. 9) In contemporary western architecture, one could find feng shui principles in the common responses to site and climate.

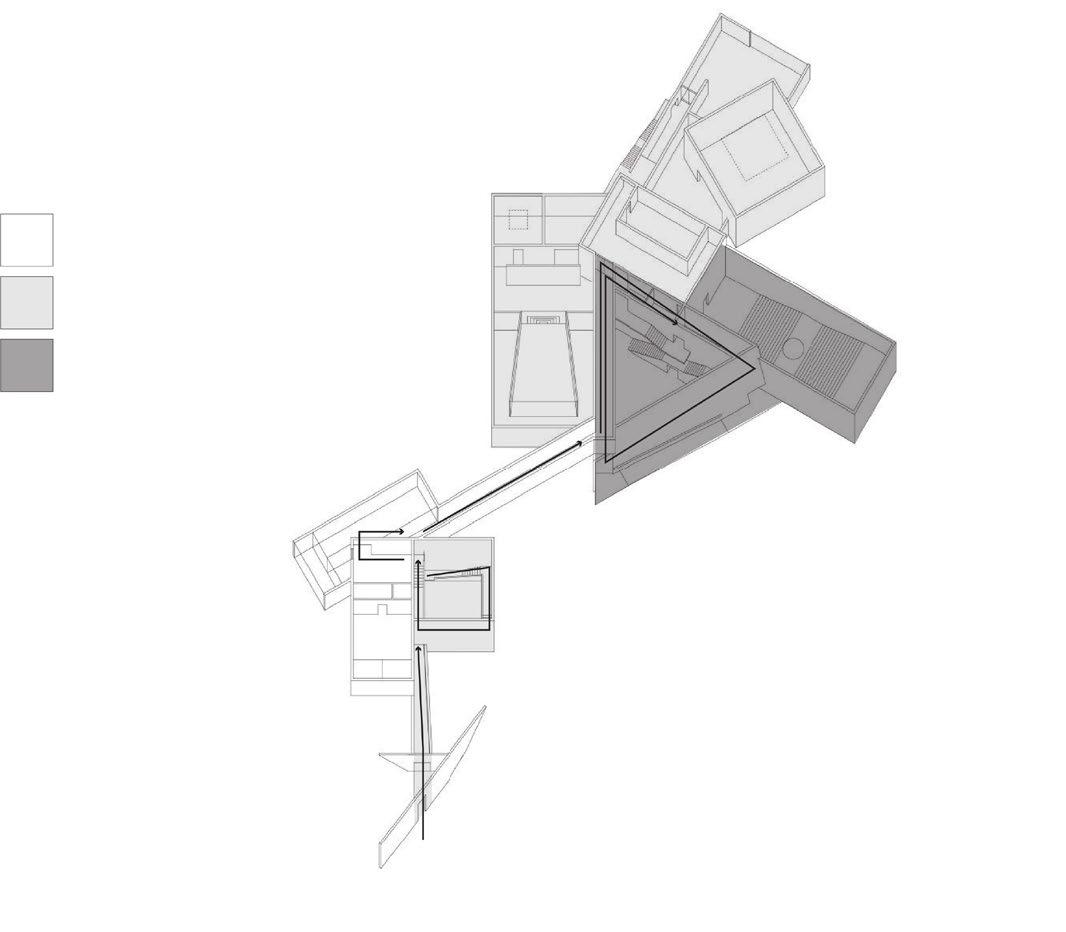

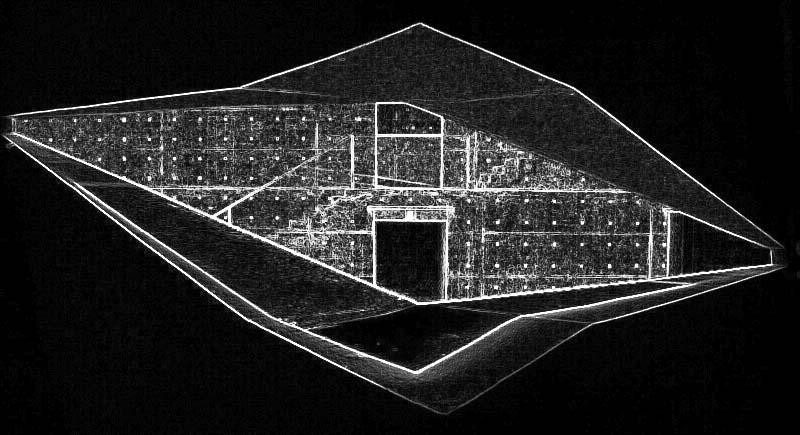

3. Chichu Art Museum

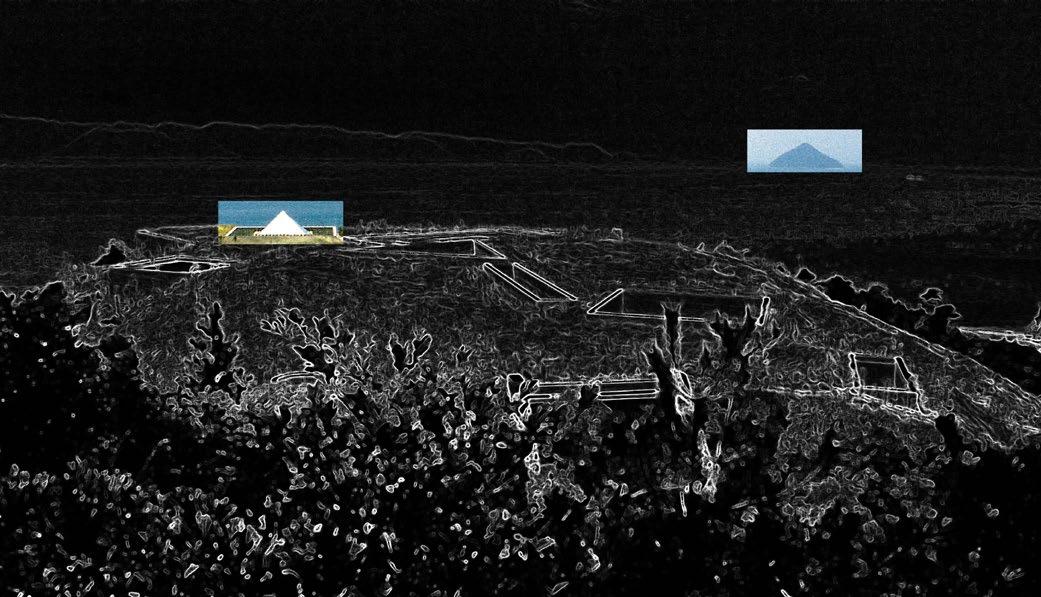

The Chichu art museum is picturesquely positioned by the sea on the island of Naoshima, Japan. However, the importance of the location runs deeper than merely being pleasant to experience. The design finds inspiration from its surroundings and mimics the neighbouring islands in its seemingly abstract pattern. The plan is based on prime geometrical forms which if seen from above seem scattered and dislocated. Consequently, it reminisces a labyrinth, which could be argued to simulate the search for enlightenment. The minimalistic shapes represent the connection between the sea and the mountains and allow for the natural flow of the site to not be disturbed, thus creating a ‘route’ for nature to move. (Nussaume, 2009, p. 163) The museum incorporates complex indirect transitions from exterior to interior through multiple turns that offer different reference frames into the architecture. Set entirely underground, the composition of geometrical forms interlinks only from within and thus denies any horizontal intrusion from the site. Diagonality and verticality dominate the design as if to channel the hidden forces of the earth and create a connection to a higher plane of existence and thus evoke a feeling of enlightenment in the visitor. One finds the diagonal transitioning to be exhilarating, whereas the visually dominating vertical axis to be directing the energy in the space. Additionally, the design begins to juxtapose the asymmetry between the immortality of nature versus the fragility of the manmade. The brute ocean surrounding the island of Naoshima has the power to reduce the museum to fragments. The use of materials in the courtyards then furthers the asymmetry between nature and architecture. Ando embodies stone and concrete to create brute minimalistic atmospheres of solemn grandeur, which oppose the softness of the earth and the fluidity of the ocean. The finishes convey a feeling of impermanence compared to the vigour of nature and thus evoke a feeling of dematerialization, which is asymmetrical to the perpetuity of the pertinent earth.

1. Figure adapted from Benesse Art Site

2.

section, figure adapted from (Dal Co, 2010, p. 376)

Ground Floor

Basement Floor 1

Basement Floor 2

3.1 Courtyards

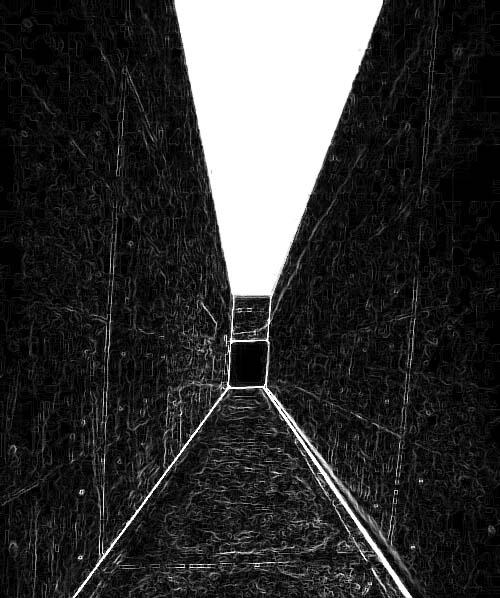

One would be easily tricked into believing a lack of natural light would prevail in the museum, for in Japanese, chichu means underground. However, all the courtyards - square; triangular; and rectangular; and exhibition spaces, even though built within the earth, utilize skylights to bring in daylight. The most evident Minimalistic design decision is the approach to the form, however, when studied the spaces divulge deeper meanings. The square courtyard serves as a recess from the dimmed underground entrance corridor. This garden space presents an antithesis to darkness, what is more, it embodies hope and brings peace for it shows that there is always light at the end of the tunnel. The design choice could be linked to the Second World War and Tadao’s aspiration that architecture would heal us from traumatic events. The following rectangular courtyard speaks of balance, for it connects the dark entrance zone with the illuminated triptych of gallery spaces. What is more, it links the idea of retaining hope with the potential of existential growth. The visually dominating form channels energy forth, thus stimulating the visitor to continue exploring, both the architecture and one’s spirituality.

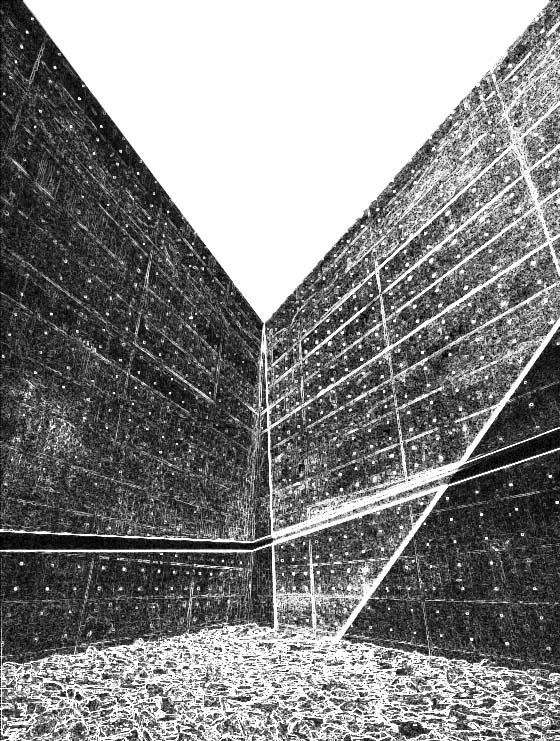

The triangular court is the central point around which all of the gallery spaces are situated and as such it reaches the maximum depth of the building. The open roof allows for the concrete corridors which surround the court to be lit through asymmetrical slits in the walls. They present an insight into the triangular courtyard and so they allow for the visitor to grasp the magnitude of the design as if watching simultaneously from within and without. The play of perspectives here suggests that Ando tries to incorporate the search for enlightenment in his design. One would need to navigate through ‘the labyrinth of life’ and appreciate different frames of reference to gain a profound spiritual insight into existential matters.

Asymmetrical slits

Triangular court

3.2 Gallery Halls

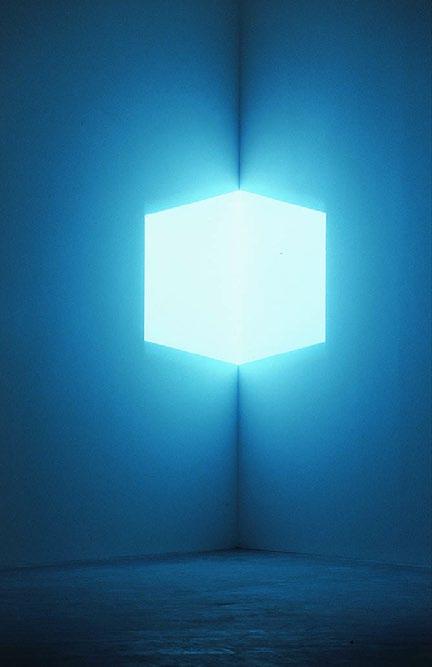

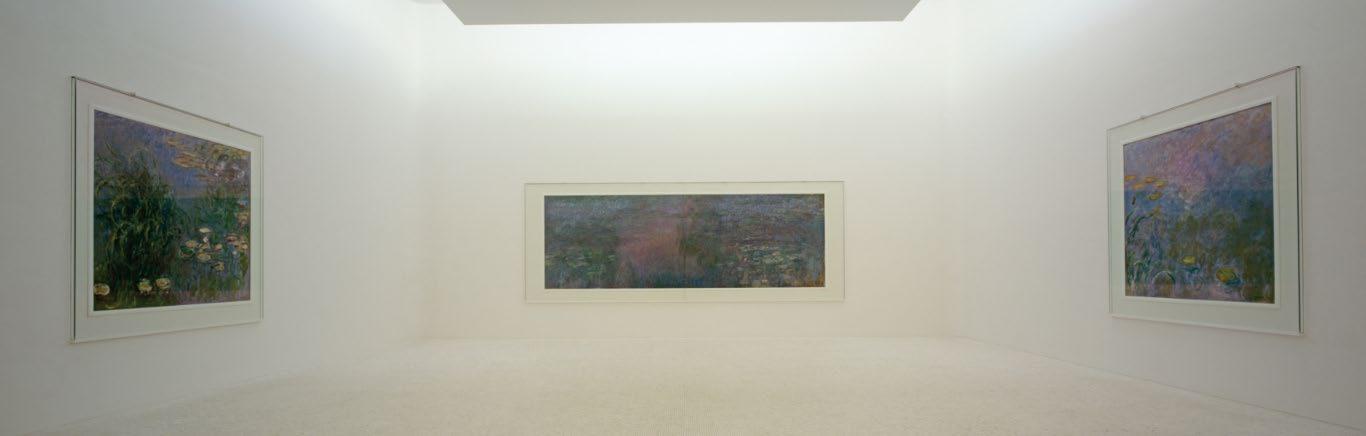

The culmination of the design are the gallery halls. Chichu art museum was explicitly planned to house the works of James Turrell’s light installations, Claude Monet – Water Lilies, and Walter de Maria’s installation Time/Timeless/No time. In the first gallery, a square rooflight shines upon a precursor space to the hall which houses James Turrell’s light installation. The exhibition space is protected from any sunlight for the art is rich in colours. It is as if to give way to different perspectives into one’s beliefs and ideas. Furthermore, Sabi is found through the minimalistic use of a white finish for the walls and the seemingly simplistic use of light as a form of art. The Claude Monet Hall is lit through all four edges of the ceiling. The rooflight takes the form of a pyramid that echoes the neighbouring island and so presents the thesis that nature sheds light on humanity. One can argue, that through this hall Ando shows his reverence to nature for he connects it with the paintings of the Water Lilies. Therefore, the architect is granting the visitor an insight into Claude Monet’s mind who also shared the fondness of nature. A rectangular skylight illuminates Walter de Maria’s installation in the largest exhibition hall. With the use of pale stone and concrete Ando creates a solemn atmosphere which is contrasted by the mammoth black granite sphere. The golden rectangles refract the natural light and illuminate the space with colour. The installation aims to provoke one’s awareness of the passage of time and thus deprive the individual of expectations. This reflects the Buddhist ideology of Satori to free the mind from complexities and attachments in order to allow for a greater sensuous experience. The theme of light is persistent throughout the chosen artworks, all of which integrate with the architecture to strengthen their statements. Consequently, art and architecture merge into one entity within the museum to serve as a window into one’s soul. The artworks present an exploration of mindfulness and spirituality.

4. Discussion on Minimalism – Absence and Asymmetry

The Chichu art museum is a monument to the architecture of absence and asymmetry, where the notion of Minimalism is embodied thoroughly. One of the most symbolic elements in Japanese architecture is the roof. As it is the dominant feature, it often expresses the wealth and social status of the owners. (Locher, 2010, p. 52) However, through the use of open roofs and skylights, Ando renounces the importance of materiality and reputation. Thus, he devotes the art museum to abstinence and humility. Truly inspired by Buddhism, the architect creates minimalist designs with a meditative aesthetic, which speak to the nature of man. (Blaser, 2001, p. 19)

Essentially, Ando gives way to sensory exploration by removing the visual excess so that one is not distracted and disoriented. Satori then is signified through employing emptiness and clean lines within the design. The aesthetic of absence is reflected in the architectural expression of restraint and thus achieving the tranquillity of monastic solitude. The building seemingly flows through the terrain for it is designed to abide by the surrounding energies of the hillside, the island and the ocean pertaining to the laws of feng shui. On account of the simplicity of forms, one finds the asymmetry between the sinuous land and angular architecture to be gentle, rather than intrusive.

Furthermore, the architect utilizes absence and restraint in the use of untreated concrete and stone. The choice of brute materials in the design creates a connection with the earth and conveys Ando’s desire to bring architecture closer to nature. He deepens those ideologies with his distinguished style which retains the traces from the connecting joints on the panels that were used to shape the concrete walls. Additionally, the notion of Sabi is also evident through that minimalistic technique. It rejects the visual excess and hence relies on rustic imperfection to evoke modesty and beauty. What is more, Ando dematerializes the space to reduce the architecture to its integral parts with the galleries serving as a triptych, which then are drawn into unity with the site. The sole cornerstone – the unity of artworks and galleries; endow the place with another plane of perspective to interpret the minimalistic approach. The triptych poses an asymmetric point to the rest of the design and takes control of the narrative of the building. On account that the museum was built for these artworks, it could be stated that Ando indeed strived to design not just a building, but rather a spiritual journey in the likeness of the Chichu art museum. Therefore, in uniting not only architecture with nature but with art as well the architect manages to achieve harmony within his design and to create a counter-point to urbanisation that serves as a touchstone for reconnecting humanity with nature and furthermore design an environment of absence and asymmetry that evokes spiritual enhancement.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that a spiritual journey and emotional balance could be derived from designing according to the methodology of Minimalism. Through the use of absence and asymmetry, brute materials and geometry Ando sways to the power of nature and builds with the mindset to integrate architecture within it. However, one could not simply disregard the hypocrisy behind the attempts to reconnect nature, architecture and humanity while simultaneously abusing concrete as a building material. This statement then emanates the question: ‘Could the same effect be achieved with a different medium?’ The sensory properties which are unique to concrete such as bruteness and coldness potentially could be imitated with other materials. The concrete relates to stone in terms of corporeal qualities. However, the finish wouldn’t be the same to the touch. What is more, it deprives the designer of the possibility to easily modify the surface, for stone is not as fluid as concrete. On the other hand, alternate mediums for building such as wood are closer to ‘nature’ and thus have less of a ‘brute’ effect. This poses another perspective on the matter and would require further investigation. Truthfully, Ando’s wish to turn his back on the chaos of the city fails in that aspect, for he rigorously incorporates the one material that is associated with new-age architecture and rapid urbanisation. However, despite the choice of materials, he thoroughly utilises them for the development of a poetic architecture that aims to oppose the chaos of the city. The design features pertaining to Minimalism are asymmetric to the unyielding urbanisation in their ideology. Through merging architecture with nature and architecture with art, Ando gives architecture the property of a physical link between nature and humanity. However, to design for balance, one must thoroughly incorporate sustainable methods of building. Thus, Ando metaphorically re-establishes the yearned balance between nature, architecture and humanity. Nevertheless, in such a way, his design still exhibits a counter-point that takes into account spiritual wellbeing and thus presents an architecture that aims to put troubled minds and souls at ease. The significance of Minimalism in contemporary architecture then attains its credit for humanity needs designs that contrast the disruption of the city and propel us forward into exploring existential matters through art and nature. Minimalist architecture, therefore, embodies more than just a cluster of building materials and aesthetics. Through the use of absence and asymmetry, one is taught to show restraint and control over themselves and to appreciate the imperfections in life. Therefore, the creation of such architecture should be nourished for the progression of humanity.

Figure List

Figure 1. Benesse Art Site Naoshima, Chichu Art Museum

Available at: https://benesse-artsite.jp/en/art/chichu.html [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Figure 2. Axonometric section, Dal Co, F. (2010) Tadao Ando, 1995-2010. London: Prestel.

Figure 3. Chichu Art Museum (2000 - 2004), Kagawa. View of the courtyard, Nussaume, Y. (2009) Tadao Ando. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Figure 4. Passage, Dal Co, F. (2010) Tadao Ando, 1995-2010. London: Prestel.

Figure 5. Scullion, M. 2008. Chichu Art Museum Triangular Courtyard - Tadao Ando

Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/29702014@N00/3113569041 [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Figure 6. Sunken court, Dal Co, F. (2010) Tadao Ando, 1995-2010. London: Prestel.

Figure 7. Turrell, J. Afrum Pale Blue

Available at: https://jamesturrell.com/work/afrum-pale-blue/ [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Figure 8. Benesse Art Site Naoshima, Claude Monet Space

Available at: https://benesse-artsite.jp/en/art/ [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Figure 9. View of the ‘burried’ structures comprising the museum with the Seto Sea in the background, Dal Co, F. (2010) Tadao Ando, 1995-2010. London: Prestel.

Figure 10. Room dedicated to Walter de Maria with the installation Time/Timeless/No Time in 2004, Dal Co, F. (2010) Tadao Ando, 1995-2010. London: Prestel.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Asensio Cerver, F. (1997) The architecture of minimalism. New York: Arco.

Blaser, W. (2001) Tadao Ando: Architecture of silence: Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Dal Co, F. (2010) Tadao Ando, 1995-2010. London: Prestel.

Locher, M. (2010) Japanese architecture: an exploration of elements & forms. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing.

Nussaume, Y. (2009) Tadao Ando. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Schittich, C. (2002) Japan: architecture, constructions, ambiances. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Suzuki, D.T. (2018) Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9780691184500. [Accessed: 18 December 2021]

Secondary Sources:

Benesse Art Site Naoshima, Chichu Art Museum

Available at: https://benesse-artsite.jp/en/art/chichu.html [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Benesse Art Site Naoshima, Claude Monet Space

Available at: https://benesse-artsite.jp/en/art/ [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Scullion, M. 2008. Chichu Art Museum Triangular Courtyard - Tadao Ando

Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/29702014@N00/3113569041 [Accessed: 27 December 2021]

Turrell, J. Afrum Pale Blue

Available at: https://jamesturrell.com/work/afrum-pale-blue/ [Accessed: 27 December 2021]