An ethic or an aesthetic?

The use of materials and poetics in the Brutalist architecture.

Topic: Autonomy and Agency – Brutalism

Ani Kostadinova

Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University;

Tutor: Irini Barbero

Research Question: The Brutalist movement: ethical, aesthetical or both?

Abstract: This research explores the ideologies connected to the post-war term and architectural style ‘The New Brutalism’. The purpose of this work is to determine whether Brutalist architecture pertains to ethics, aesthetics or both. Their sub-topics of truth to materials, mass production and poetics are reviewed in order to define the answer. As frame of reference are used the ideas of the architects Alison and Peter Smithson, Aldo van Eyck and the critic Reyner Banham. Their theories are then applied to the case study of the Amsterdam Orphanage. Essentially, the essay presents the profound connection between ethics and architecture, which is found in everyday buildings, such as an orphanage. Lastly, this article advocates in favour of Brutalism being both ethical and aesthetical, with the appropriate context and design.

Word Count: 2719

Keywords: The New Brutalism; Poetics; Ethics; Aesthetics; Truth to materials; Smithson-Banham; Aldo van Eyck; Amsterdam Orphanage;

1. Introduction

The interdependence between the socio-cultural context of the twentieth century and a group of architects, called Team 10, stimulated a correlated development that defined the century. Aldo van Eyck, Alison and Peter Smithson, along with Georges Candilis, Giancarlo De Carlo, Jaap Bakema, and Shadrach Woods, formed the Core Group. They scrutinized upon architectural ideas and helped shape the fundamental values of the XXth century. The Core Group was inspired by vernacular society and culture. Their concepts relied on spontaneity and innovation; hence they majorly ameliorated the methodologies of the time. The changes upon architecture were focused toward designing for greater diversity and stronger relationships with climatic, social, economic, and political conditions, thus, promoting an architecture which was closely linked to its context. (Campos Uribe et al. 2020, pp.2–3)

The post-war culture is known for rebelling against the well-established norms. On account of the long shadow of war, which was cast over the world, the mass cultures: music, art, and literature; were promoting an uncompromising expression of the perspective on everyday life. (Grindrod 2018, p.23) In the architectural field, the brut aesthetics had taken root and a new movement – Brutalism, emerged and became the manifestation of the era. Its appeal emanated from the general frame of post-war mindset and was strengthened by the mass cultural tendencies. The visual effects of strength and gloom that concrete conveyed, echoed the monotonic everyday life of the average citizen.

However, there are controversial opinions on whether there is more to Brutalism, than merely aesthetics Alison and Peter Smithson and Reyner Banham argue extensively whether Brutalism is an ethic, or an aesthetic. This essay explores both sides of the argument, as well as the topics of truth to materials, mass production and poetics, embedded in the term. Additionally, the work takes into account the ideas of the architect Aldo van Eyck, regarding the duality of space, and scrutinizes upon one of his projects – the Amsterdam Orphanage. The case study would be explored with reference to the two contrasting standpoints, regarding Brutalism, and would be utilized in answering the question: Is Brutalism ethical, aesthetical or both?

2. Literature review

During the nineteen-fifties a rather peculiar occurrence had found itself at the centre of the architectural field. Usually, for an architecture term to be coined, there must have been a massive movement, one that had left a physical mark of its existence and had progressed over time. However, when it comes to the term ‘The New Brutalism’ that is not the case. Interestingly enough, the principles of the term were coined before the existence of such an architectural monument. What is more, the bizarre circumstances then resulted in the need of alterations of the essence in the long run as Banham (Banham 1966, p.10) asserts. However, it could be argued, that the need of re-appropriation is a natural consequence to the development of an architectural movement.

The popularization of the term owes much to the ‘Smithson-Banham axis’. The dynamic between the architects Peter and Alison Smithson and critic Reyner Banham is often described as a falling-out between friends, as van den Heuvel (van den Heuvel 2015, p.297) presents. Their different interpretations divide the Brutalist movement into two theories. One side

asserts that ‘The new brutalism’ has the ability to make a moral stand about architecture, while the other argues that it is nothing more than an aesthetic.

2.1. ‘The New Brutalism’ by the Smithsons

Initially, the definition of ’The New Brutalism’ is described by the Smithsons as a ‘warehouse’ aesthetic, that focuses on the material’s character and the exhibit of the structure. (van den Heuvel 2015, p.299). In their work, they strongly emphasize the importance of the materials, regarding their raw qualities and poetical meaning, and often discredit the other architectural components of the design. With time, their concept alternated as the Smithsons’ shifted their subject of interest from the artistic point of view, to the urban one and thus, substituted the architectural and the material for the urban and the mobile. Nevertheless, the key issues have always gravitated towards the ethics of architecture. Eventually, they redefined their style by combining both materiality and urban planning, in order to create ‘‘purely sensorial environments, of ‘built-places’ (and not buildings) that go beyond the sheer visual.’’ (van den Heuvel 2015, p.300)

2.2. ‘The New Brutalism’ by Banham

On the other hand, according to Banham (Banham 1966, p.127) Brutalism has always been defined by:

1. the building as an unified visual image, clear and memorable

2. the clear exhibition of its structure

3. a high valuation of raw untreated materials

Banham’s definitions would cover patterns and clusters, geometries and textures, processes, traces and remembrancers. They were pursuing structures or systems beyond the singular image or the ‘sheer visual’ . (van den Heuvel 2015, p.303) The significance is that although there are precise descriptions, all of the points consider the Brutalist architecture only from the visual aspect. Banham dismisses the theory of architecture making a moral stand.

2.3. Truth to Materials

What can clearly be understood is that the truth to materials and visibility of the structure are key to the concept of ‘New Brutalism’ on both sides. Originally, the reverence towards the natural world in Japanese architecture was what had enthralled the architects of the early twentieth century. From that derived the acclaim of the materials in the built world. The essence is that the admiration of materials creates a nurturing relationship between man and architecture1. However, it is key that according to the Smithsons, the appraisal is not with regard to the craftsmanship, but to the intellectual meaning of the materials. (Smithson and Crosby 1955, cited in Banham 1966, pp.45–46) This is where Smithsons’ and Banham’s ideologies differ. Banham supports the orthodox sense of appreciation towards the aesthetic mastery of the materials that Frank Lloyd Wright used

2.4. Mass Production

Nonetheless, Banham still acknowledges the Smithsons’ attempt to see architecture being autonomous from politics or prefabricated aesthetic preferences. ‘’Any discussion of Brutalism will miss the point if it does not take into account Brutalism’s attempt to be objective about

reality … Brutalism tries to face up to a mass production society.’’(Architectural Design 1957, cited in Banham 1966, p.47) Ironically enough, nowadays, the main material associated with Brutalism, that is concrete, reigns over the mass production industry. However, in the past Brutalism was an original way of thinking and concrete, being shapeless and relatively new, effortlessly became the manifestation of creativity. The material freed architects, to an extent, of the gravitational restrictions. What is more, the outstanding physical performance of the material granted confidence in experiments and relieved some of the financial problems in construction. The Smithsons, as members of team 10, were involved with tackling the established norms Naturally, they were immensely absorbed with the notion of Brutalism and concrete was one of their main shaping tools while defining the social ethics of a built space ‘’It is in everyday application that brutalism finds both its soul and its ethical dimension.’’(Grindrod 2018, p.25) In consequence, the Smithsons combined the meaning of materials and built spaces in order to create their ethical ideology of Brutalism.

2.5. Poetics

The poetics in Brutalism link back to the Smithsons’ belief in the intellectual and poetical meaning of the material. The poetics are brutally exposed as they are embodied in the visibility of the building’s fabric. Revealed parts of the structure, plumbing or wiring convey candidness and, in that nourishing relationship between man and architecture1, the architecture evokes honesty in man. In Brutalism there is not only truth to materials and structure, but there is also truth to oneself. However, in colloquial language one might use the term Brutalist to describe something that is coarse and strong. Something that stands despite it all. When taking into account the general post-war psychological mindset, the intrigue in concrete is granted meaning if one considers that the visual and physical properties of the material stimulate emotional and psychological comfort in people. If one was to experience that day and age, the overwhelming gloom, it becomes evident why people were discovering consolation in the roughness of concrete.

3. Case-studies

Between 1955 and 1960, Aldo van Eyck designed one of the most prominent examples of Brutalist architecture. The Amsterdam Orphanage is not only a statement about the essence of

architecture, but is also a key example of the architect’s theories of ‘’dual phenomena’’ (Grafe et al. 2018, p.16) Through the Amsterdam Orphanage van Eyck presents the idea that architecture is able to heal the psychological damage that had been inflicted upon people. By means of architecture he tries to mend the children, in order for them to return to society as functioning members. (Grafe et al. 2018, p.15) The architectural composition then acts as a social condenser and represents the architecture of reconciliation.

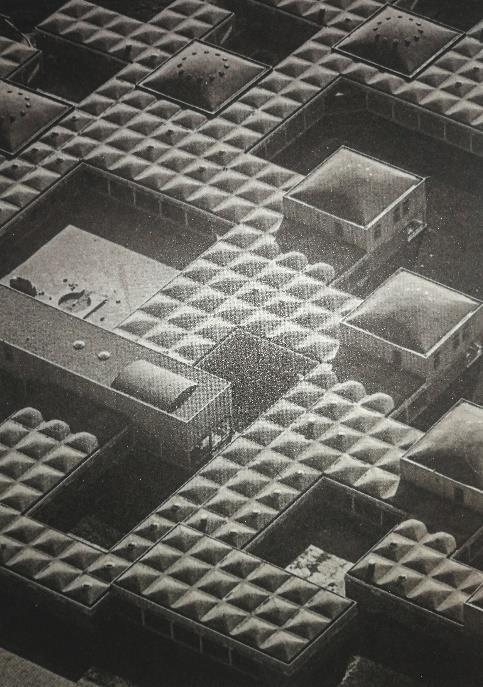

Symmetry and fragmentation of the plan define the building. Figure 1 Orphanage Layout (Grafe et al. 2018, p.46) The architect skilfully combines centralized aspects with decentralized ones as contrast. The domed roofs create a moment of centrality that is opposed to the nonaxial diagonal planning. (Grafe et al. 2018, p.16) The terrace scheme varies with the different children’s sections, in order to indicate the importance of the correlation between the internal and external. Figure 2 Amsterdam Orphanage (Fracalossi 2019) Nevertheless, the connection between places is strengthened by the vast use of glass and reappearing grid patterns.

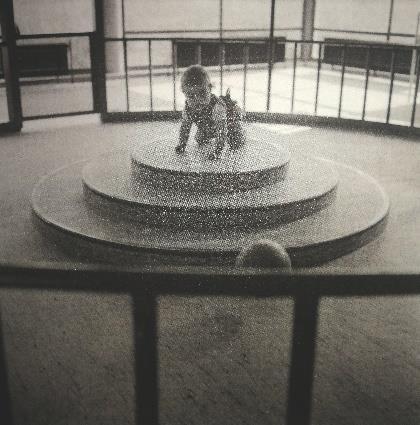

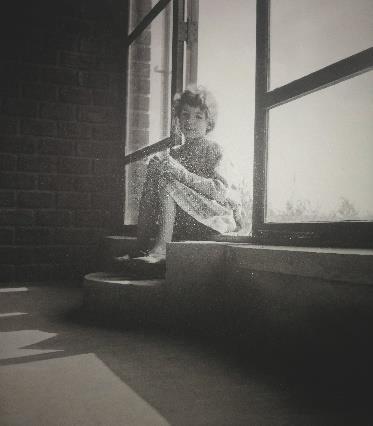

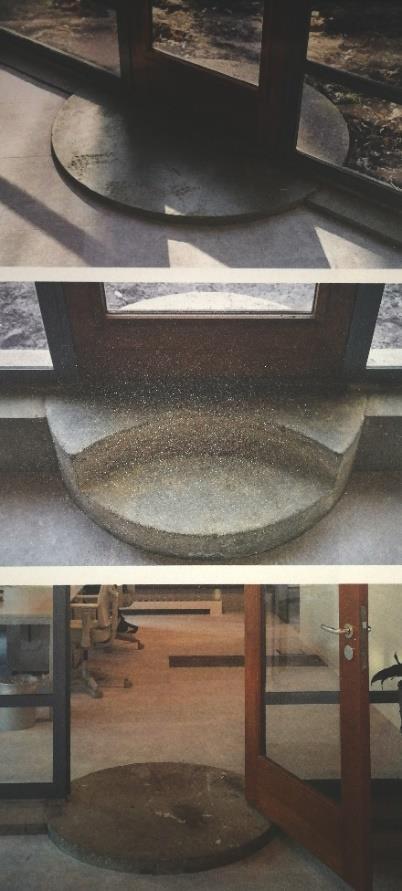

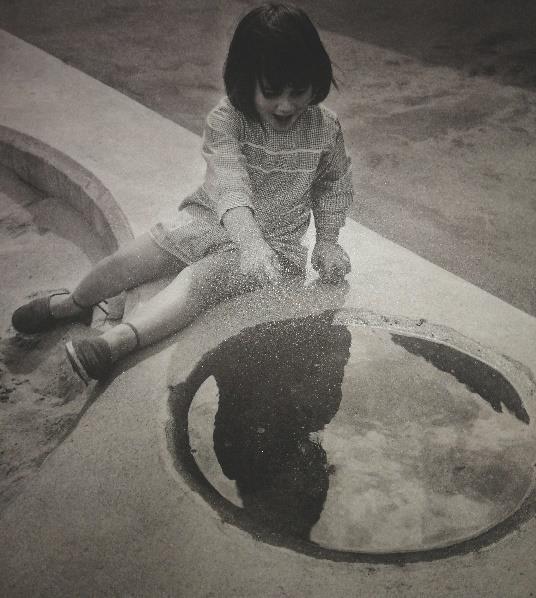

Van Eyck uses geometry to define the character and function of spaces. Space is the primary place for humans to gather and as such the playgrounds become the most essential instance of the social condenser idea in the Amsterdam Orphanage. The playgrounds as well as thresholds leading to them, such as steps or doorsteps, were indicated with circular forms. Examples: Figure 3 Baby House (Grafe et al. 2018, p.102) and Figure 5 Threshold Doorstep2 (Grafe et al. 2018, p.58). The seating areas were either made out of wood or concrete accompanied with coloured glass. Figure 4 Sitting Area (Grafe et al. 2018, p.66)

The dominant colours in the palette are the earthy tones of brickwork, concrete and natural stone, which are opposed to the brightly coloured wall finishes and decorative elements. Van Eyck differentiates the exterior and the interior corridors, by keeping the first rough and natural and by making the latter smooth and colourful. Figure 6 Collage of Materials (Grafe et al. 2018, p.85) In between these realms of

public and private, the threshold is embodied by wooden doors. Figure 7 Wooden Thresholds - Doors (Grafe et al. 2018, p.59) The smooth and unpainted surfaces, with yet warm hues, cover qualities of the materiality from both realms. Thus, they account for a natural transition between spaces (Grafe et al. 2018, p.73)

4. Discussion

In order to comprehend the Amsterdam Orphanage, one must firstly apprehend Aldo van Eyck’s ideology regarding the ‘’dual phenomena’’. Architectural spaces are shaped following the image of man and the duality of man suggests that a place should have the same quality. According to van Eyck, therefore architecture must mimic the anthropomorphic pairings, e.g., breathing in and breathing out. (Georges Teyssot 2008, p.37) He maintains that architecture should be giving and receiving. Similarly, like his colleagues - the Smithsons, he shares the same belief of ethics in Brutalism.

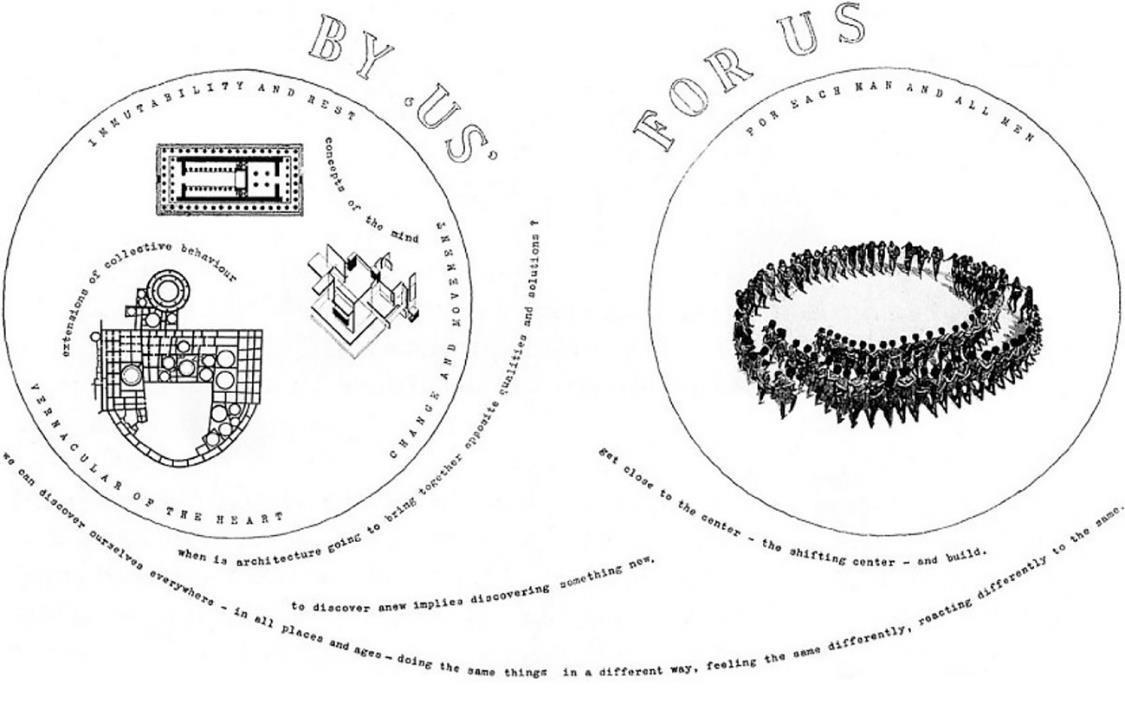

In Figure 8 Otterlo Circles, 1962 (Campos Uribe et al. 2020, p.12) van Eyck explains these pairings with a diagram. He states that new aspects could be found in old ideas, as long as they are re-examined rigorously, and that human beings and their needs must be understood more thoroughly, in order for architecture to keep progressing.

4.1. Aesthetics - Architecture of Reconciliation

The Brutalist’s idea of truth to materials is evident in the design of the Amsterdam orphanage. The untreated external surfaces of concrete, brickwork and natural stone serve as a connection to the primitive and evoke a feeling of reverence towards nature. One is humbled and brought back to simpler days. On the other hand, the interior spaces, which the children and staff inhabit, have treated and painted surfaces. This refinement on the rawness of nature, colour, is used to define the character of the building. The blend of clear blue, purple, red and yellow, pink and dark blue conveys compelling and cheerful emotions. The colours evoke a powerful visual stimulation in the observer that aims to distract from the monotonous days

and to create a gratifying environment. Through the juxtaposition between the different materials and colours van Eyck highlights the contrast of public and private spaces. The threshold in between those realms is represented by wooden doors, because they possess qualities pertaining to both sides - rawness and colour Van Eyck represents such architectural moments, thresholds, as an intersection point between the opposing aspects. Similar example is the doorstep that connects the playground and the internal space.2

4.2. Ethics and Poetics – The Social Condenser

There is an occurring and poetical connection to the sky in the Orphanage. One example is found in the sandpit, where circular distorting mirrors are placed so that they would reflect the sky. On Figure 9 Sandpit Mirror (Grafe et al. 2018, p.57) we see a child experiencing the architecture of that connection. Another instance throughout the building is the pattern found in the roof, which either has one circular rooflight per smaller dome or a grouping of them on the bigger ones Figure 10 Roof lights (Fracalossi 2019) What stands out is the meaning that van Eyck embeds in the circular shapes. It could be stated that he links them to childhood dreams, which are represented by the sky, and games - connected to the ground. This beautiful synergy embodies his hopes that the children will find happiness in the orphanage and will develop as healthy grounded beings, yet full with dreams.

5. Conclusions

Essentially, the Brutalist movement was shaped differently from any other architectural style. The co-dependent relationship between the socio-cultural context and the architectural community stimulated rigorous analysis and synthesis. Brutalist representatives did not fail to deliver ideas and projects that should be approached with serious consideration. Such one is Aldo van Eyck and his Otterlo Circles. His concept meticulously describes that co-dependent relationship ‘’By us, for us’’Error! Bookmark not defined. The community shapes architecture and architecture shapes the community.

In closing, between the Smithsons’ and Banham’s definitions regarding Brutalism, the first is the most sumptuous one. Banham argues that their notion is incoherent and inconsistent, because they persistently try to expand and develop it For Banham Brutalism embodies the aesthetics of truth to materials and construction, i.e., the quality of the materials and evident structural fragments as part of the design. However, just like people, architectural movements

must undergo changes in order to improve and thus alterations with ethical regard should be endorsed, not condemned or condescended. This is underpinned on Aldo van Eyck’s ideas of connection between the architecture and the anthropomorphic, and further – on the duality of man and therefore of space Humans are two people simultaneously: who they were and who they will be. The now is eluding a clear definition, as it is nothing more than a transition from the past to the future, a threshold if you will. Architecture is based on the same principle, there are never clear timestamps where a certain movement had begun or ended.

The most notable development of the twentieth century was the Brutalist’s movement proposition that it is possible to make a moral stand regarding design. While the aesthetics of asymmetry and beton brut may now be outmoded, the insightful idea that behind the creation of an everyday architecture (e.g., Hospitals, Orphanages, Schools, etc.) there is an ethical standpoint, is what lives on. The poetics and ethics in creating a social condenser, would never cease to inspire the thoughtful minds. Thus, the profound belief in moral projects remains pertinent to contemporary architecture. What is more, Brutalism urges architects to design with materials that are true to their nature, thus to design in the wider social, economic and climatic context. This research demonstrates that Brutalism could be both ethical and aesthetical.

6. References

Banham, R. 1966. The New Brutalism. London: Architectural Press.

Campos Uribe, A. et al. 2020. Multiculturalism in Post-War architecture: Aldo van Eyck and the Otterlo Circles. ACE: Architecture, City and Environment 14(42). doi: 10.5821/ace.14.42.7033.

Fracalossi, I. 2019. AD Classics: Amsterdam Orphanage / Aldo van Eyck.

Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/151566/ad-classics-amsterdam-orphanage-aldo-van-eyck

[Accessed 28 January 2021]

Georges Teyssot 2008. Aldo van Eyck’s Threshold: The Story of an Idea. Anyone Corporation, pp. 33–48. Grafe, C. et al. 2018. Aldo van Eyck Orphanage Amsterdam Building and Playgrounds. Amsterdam: Architectura & Natura.

Grindrod, J. 2018. How to Love Brutalism. London: Batsford. van den Heuvel, D. 2015. Between Brutalists. The Banham Hypothesis and the Smithson Way of Life. The Journal of Architecture 20(2). doi: 10.1080/13602365.2015.1027721.