“If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.”

- Mother Teresa

“If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.”

- Mother Teresa

Tuesday, 6 August 2024

9:30 AM Registration

Inauguration of the Event- Welcome by Elizabeth Neuville

Introduction to the Course and Faculty

Tea/Coffee Break

PART 1 : The Wounding Life Experiences

Presentation: Social Devaluation through Negative Roles

1:30 PM Lunch

Plenary Session: The Wounding Life Experiences (cont’d)

Tea/Coffee Break

Plenary Session: The Wounding Life Experiences (cont’d)

Small Group Discussion: Devaluation and its Consequences

6:00 PM End of Course Day

7:30 PM - 10:00 PM Dinner

Wednesday, 7 August 2024

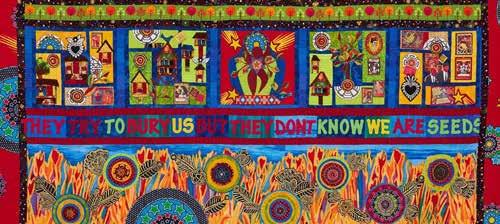

9:00 AM Two Group Reflections on Devaluation: “My Favorite Devalued People” and “The Universality of Oppression”

Start of the Day: Morning Reflection; Burning Issues

PART 2: Social Role Valorization

A “Bird’s Eye View” of SRV: E. Neuville

Tea/Coffee Break

Some Positive Examples: G. Mondol and E. Neuville

Introduction to the Themes of SRV: The Red Thread of the CVA

1:00 PM Lunch

Unconsciousness

Tea/Coffee Break

Unconsciousness Small Group Session Part 2

The Conservatism Corollary (presentation and discussion)

Program Close

7:30 PM - 10:00 PM Dinner

Evening Discussion (Optional)

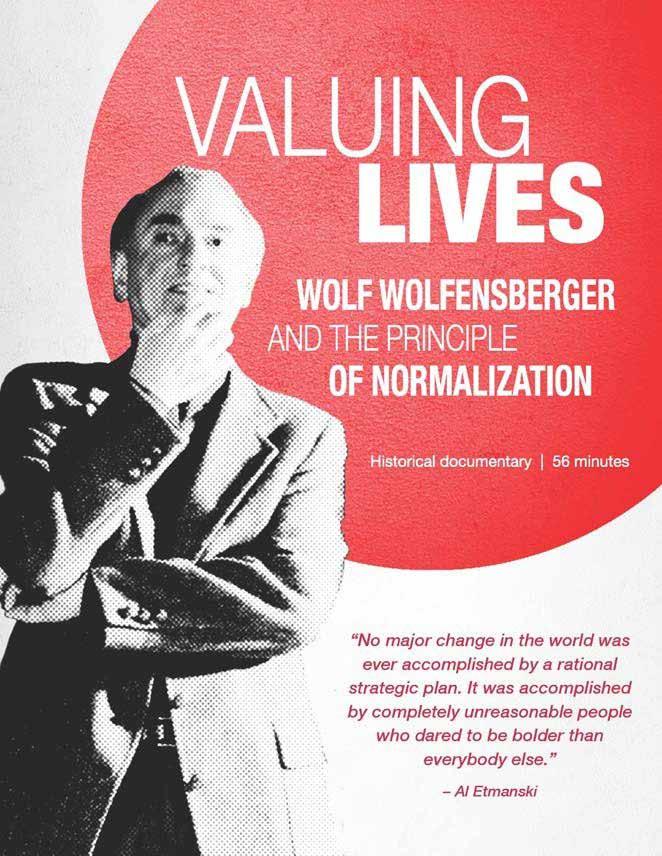

“Film Screening- Valuing Lives: Wolf Wolfensberger and the Principle of Normalization”

Thursday, 8 August 2024

9:00 AM Program Start

Prevent, Reduce and Compensate small group work (All Faculty)

The Dynamics of Interpersonal Identification (Presentation and Discussion)

Tea/Coffee break

The Power of Mindsets

The Dynamics of Role Circularity (presentation and discussion)

1:00 PM Lunch

Symbolism and Imagery Use (presentation and discussion)

Tea/Coffee Break

Model Coherency (presentation and discussion)

Personal Competency Enhancement and The Developmental Model (Presentation and Video)

7:30 PM - 10:00 PM Dinner

Evening Discussion (Optional): SRV Implementation in the Indian Experience

Friday, 9 August 2024

9:00 AM

Program Start

The Power of Imitation (Presentation and Discussion)

Tea/Coffee Break

Personal Social Integration and Valued Social Integration (Presentation, discussion and video)

PART 3: Implementation of SRV

1:00 PM Lunch

Preparation for the Implementation of SRV: Small Group Session Evaluation

Tea/Coffee Break

Where do we go from here? India’s Inclusive Future, Presentation of Certificates, Vote of Thanks and Concluding Video

5:00 PM Program Close

Dear Course Participants,

On behalf of the Keystone Institute India, the All-India SRV Association and our sponsoring organizations and collaborating partners at The Rural India Supporting Trust, we extend a warm welcome to you. It is our hope and expectation that the next four days are ones full of deep reflection on your commitment, your direction, and your own work in assisting people with disabilities to take their full place in society. We are pleased to offer this workshop as a continued expression of our commitment in support of services which are truly responsive to the needs of the people who are served. It is our hope that you will join many others over the years for whom this event has been a pivotal one – one which shapes our understanding and demands that we commit to listening more carefully and learning more deeply.

We have a carefully-developed participant group formed from leaders across India, and it is our intention that this course will strengthen your foundation, build your strength, connect you with others, and fuel the movement across India towards a society where all people, including those with disabilities, belong and are truly valued. We are all on the leading edge of change in India, and we will strengthen each other’s work.

We are so fortunate to have skilled presenters and group leaders for this workshop. Our workshop faculty members are experienced in SRV theory and implementation and have made significant commitments to learning and growing in this area. We are grateful for their time and experience. They serve as resources and connections for you, so please do share information, talk with them, and connect.

We are glad that you put aside the time to invest in this demanding and rigorous learning event, and we hope that you will leave this course with a passion to learn more. There is a broad range of opportunities for people wishing to pursue development and implementation of Social Role Valorization. We are excited about working in partnership with you in your personal and professional development, as well as serving as a resource to you in making a difference in the lives of the people you support. This event promises to be a landmark of sorts in the work towards creating a society that works for everyone, and we are glad to be sharing this experience with you.

Elizabeth Neuville Executive Director Keystone Institute India

The materials in this manual, and those presented in the workshop, are offered with deep appreciation to the major developer, Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger, as well as those who have contributed to the teaching and development over the past decades. Please respect the work and do not copy or disseminate further. All materials are taught with permission from the developers.

This is an invitational residential course offered to selected applicants nominated by the collaborating partners and past program graduates. Collaborating partners are The Rural India Supporting Trust, and Keystone Institute India (KII)

Course Organizer: Keystone Institute India

Prashansa Pandey, Project Leader-Events and Workshops ppandey@khs.org +919779754828

This is a residential course, with participants arriving 5th evening. Because of the long hours and rigorous focus required, all invitees are requested to stay overnight at the hotel if possible. The course will conclude by close of day on 9th August. Participants will check out of the hotel that morning and should make arrangements to depart in the evening, after the close of the session, or as organized by the Course Organizer.

Participation in this course will be by invitation to apply only. Nominations selection was based on perceived leadership qualities, likelihood of influence in shaping policy and practice in disability services, and openness to change and critique of standard service models. Invitees include family members, professionals, and people with disability.

All nominees must have a firm and fluent ability to communicate in English. Translation into other languages unfortunately is not possible for this intensive course in this four-day timeframe, however, accommodations will be made by all in informal assistance with accent differences and understanding from our diverse national and international attendees and faculty.

The workshop will be limited to selected participants, with most coming from geographic areas outside Delhi. Travel costs are provided for those attending from outside of Delhi, and accommodation costs are included for all participants. A certificate will be given to all those who successfully complete the course. Implementation project support and leadership development (i.e., “train the trainer”) will be offered by KII as a follow-up to this workshop for selected participants. All successful participants will join the All -India SRV Leadership Network, with access to national SRV experts and practitioners across India.

The theory of Social Role Valorization (SRV) and its predecessor idea, the Principle of Normalization, was first developed in North America in the early 1970s by Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger. At the time, inhumane conditions prevailed in North American institutions, where many thousands of people with disabilities were segregated, congregated, abused and imprisoned. Normalization, and later Social Role Valorization, informed and impassioned a generation of architects of the community system as they envisioned a society in which people with disabilities could experience freedom, dignity and the opportunity to experience ”the good things in life.”

SRV is a social theory that examines and helps us understand the process of social devaluation – how do people come to be at the bottom of the social ladder, and what are the predictable “bad things” likely to come their way once they lose value within the society? These “bad things” have been descriptively called the “wounds” of social devaluation and are inflicted on devalued people relentlessly, systematically and often unconsciously. They include such experiences as being profoundly rejected, being thrust into negatives roles such as “eternal child” or “menace” or “object of pity,” being stigmatized by the attachment of devastating imagery, being distanced and segregated from society, and many other hurtful and damaging experiences. SRV states that the good things in life that we all strive to have, such as freely-given relationships, belonging, a good reputation, contribution and personal growth, tend to come to people who have many positively valued social roles, such as neighbor, student, citizen, family member, etc. If we can assist people to move into valued roles, we increase the likelihood that people will have access to these good things. Today, Social Role Valorization remains highly relevant and useful within all fields working to make things better for marginalized and oppressed people. Understanding the societal forces of devaluation and how to effectively work towards a full, rich meaningful life alongside affected people equips us to work for real change in the world.

The training is an intensive four-day theory workshop which presents the idea of assisting people with disabilities and other devalued conditions to have positive social roles as a productive and helpful response to those wounding life experiences. This foundational material is essential to those wishing to serve others in meaningful ways, and who are impassioned to make a difference in the lives of others.

The framework of Social Role Valorization is taught through the elaboration of ten themes:

! The Power of Unconsciousness

! Imagery

! Positive Compensation for Disadvantage

! Role Circularity

! The Developmental Model

! Service Model Coherency

! Social Integration

! Identification

! Imitation

! Mindsets

This course will include multi-media presentation, small and large group reflection and discussion, and resource materials. Participants should be prepared for significant segments of presentation as well

as group work. As well, participants are reminded that this is a serious-minded workshop for seriousminded people who are interested in real change. The format is rigorous, the expectations are high for full investment by all participants, and the opportunities for joining a community of committed change agents within India and around the world is high.

Although focused on theory, the structure of this introductory course allows for participants to discuss and challenge each other through multiple small group experiences lead by experienced group leaders interspersed throughout the four days.

The principles and ideas you will be learning about will be much more impactful when you can see how they have affected the life of a person you are connected to in your own life. Additionally, learning about Social Role Valorization is most enriching and meaningful when you come to the workshop prepared. This includes spending some time with a person who is vulnerable or devalued, perhaps a person you have met through your work who experiences a disability or impairment. In preparation for the Social Role Valorization workshop, please:

Familiarize yourself with the information pertaining to the life story of someone you know who lives with a devalued identity or condition. This will be your “focus person” for the material. The more fully you prepare this assignment, the more you will be able to personalize the material and draw guidance from it. Try to find out the following information about the person:

1. What relationships with family and friends does this person have, and what are the attributes of these relationships?

2. What type of residence does the person live in?

3. What type of day program, school, or work does the person have?

4. What is a typical day in the life of this person?

5. What does the person want in terms of their lifestyle and future?

6. What do others see in the future for this person?

7. What are the person’s strengths and gifts?

8. Are there other relevant details?

Please remember that all of this is confidential and for your learning only. It would be a good idea to ask the person you are writing about for their permission to use the information. Please invest time into preparing this information, as the more you invest in it, the richer your learning experience will be.

Thank you!

Elizabeth Neuville serves dual roles as Executive Director of the Keystone Institute, a US-based educational Institute, and Director of Keystone Institute India. She has nearly 40 years of experience within Keystone Human Services as a human service worker, administrator, agency director, evaluator, educator, and personal advocate, as well as extensive experience in designing and developing supports for very vulnerable people, meaningful quality measurements, and extraordinary employee development programs.

Betsy has worked extensively with the ideas of Normalization and Social Role Valorization, and provides training and consultation internationally, with extensive experience in Central and Eastern Europe, and, in recent years, India. She is fully accredited by the North American Social Role Valorization Council as a senior trainer of SRV, and co-founded the International SRV Association in 2015. She has led SRV and person directed practice initiatives in Canada, across the United States, India, Republic of Moldova and other countries across the World.

She studied under the mentorship of Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger, the developer and foremost proponent of SRV, and has, in turn, mentored and supported a generation of people committed to personal human service to others. Elizabeth is a founding member of the International SRV Association, and has written and presented extensively on the subject.

She began involvement with using the tools and techniques of PersonCentered Planning in 1992 as a means to move people towards better lives, and has extensively studied and used the work of Beth Mount in Personal Futures Planning and Jack Pearpoint in PATH and MAPS. She has taught person centered planning techniques across North America, India, Romania, the republic of Moldova, and Azerbaijan. She has developed techniques which merge the use of traditional PC planning with Social Role Valorization and Model Coherency, increasing the likelihood that such processes will involve identifying and meeting true needs, as well as incorporating the use of valued social roles.

Betsy divides her time equally between India and the US. She holds a Master of Science in Disability Advocacy and Leadership, and a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology and English from Bucknell University.

Ms. Geeta Mondol serves as Director of Community Programs, providing consultation and education in our many programs and events. Geeta has decades of experience in working with, and being with, people with disabilities, and is also a parent of two young men, one of whom experiences autism.

Geeta leads programmatic aspects of a pilot project which assists women with developmental disability who have been abandoned in institutions to reestablish themselves as valued and contributing members of their communities, as well as heads up a highly successful program to re-unify institutionalized people with disabilities with their families.

She has been involved in conducting training on inclusion and integration of people with disabilities with many organizations in various parts of the country and abroad. Her early years involved working in a mainstream school helping include those with disabilities in the mainstream classrooms. Currently, she works within KII to create exit paths from government institutions so that some of society’s most rejected people can experience genuine community life.

Geeta was a pioneer by completing the inaugural Social Role Valorization (SRV) 1.0 training course in 2016, and assists to implement SRV within organizations and in the life of her family. She has participated in pilot projects using person-centered planning, and served as a member of multiple planning circles, both in training simulations and in bona fide planning sessions. She attended PASSING SRV Service Assessment training in the United States in 2019.

Leela Raj is the Project Leader for multiple change initiatives within Keystone Institute India. Leela has a passion for education and change agentry, and is committed to collaborative work building capacity and awareness. She first connected with the ideas of Social Role Valorization during her Masters work in Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Kentucky, and has been working closely with us since her return to her home city of Mumbai. Her portfolio at KII includes developing high quality curriculum for the development and formation of direct service workers as a developing role in India and leading the Supported Employment initiative in India.

Leela brings a great deal of experience and commitment with her, as a mentor, counselor, advocate, and activist working alongside young adults with developmental disability and their families.

Ranjana Chakraborty brings experience and deep commitment to her teaching and facilitation in Social Role Valorization and inclusive practice. A founding member of the All-India SRV Leadership Network, Ranjana joins the team of Associate Faculty for KII, working together across India for change. She is an experienced implementor of ideas related to SRV, and has particular expertise in evaluating service practices. Her role as a Board Member at Autism Society West Bengal, one of the leading organizations promoting the ideas of Social Role Valorization in India, as well as being a qualified special educator and family member of a person experiencing disability, bring both perspective and experience to bear as we move toward a different way to think about disability. From Kolkata, West Bengal, Ranjana’s background in microbiology brings diversity of thinking and rigor to her approach. As well, Ranjana’s advanced training in Social Role Valorization in US and India are supplemented by her passion for change.

Dr. Manisha Bhattacharya is a Clinical Psychologist from Kolkata, India, where she uses SRV-informed strategies to assist people with autism and their families to lead full, meaningful lives. A firm supporter of inclusive practices, she has completed advanced training in Social Role Valorization in India and in the United States, with experience in service evaluation. She teaches SRV in both English and Bengali, and has pioneered the advancement of SRV to Bengali and Bangla speakers in India and Bangladesh. Dr. Bhattacharya also has experience in person-centered planning facilitation, using methods which include Personal Futures Planning, PATH, and others.

Bringing over a decade of experience to the field, she provides early intervention support to young children, as well as counseling for teenagers and adults with an eye towards preserving their psychological and general wellbeing through achieving meaningful life experiences.

With specialized training in Social Role Valorization (SRV) and PASSING from Keystone Institute, USA, Dr. Bhattacharya embeds these ideas in her practice so that each individual with any disability can move toward a valued, fulfilling, and meaningful life, and has taken leadership within the All-India SRV Leadership Network, with a special focus on program evaluation.

Dr. Bhattacharya completed her Ph.D. in Psychology from the University of Calcutta. She is also a certified Narrative Practitioner, exploring alternative ways of seeing disability and searching for ways that people with disability themselves can name, define, and address difficulties they are facing. She has been integrally engaged with Keystone Institute India as a partner and colleague for well over five years.

Aparna Das is the Founder and Director of Arunima: A Project for People with Autism. A special educator with over three decades of experience, Aparna started her career at AADI (formerly called the Spastics Society of Northern India.) She then went on to work at Woodstock School, an international boarding school in Mussoorie, where she set up and headed the Learning Assistance Program for a number of years. While she was at Woodstock, Aparna reflected on the needs of her younger sibling, Arunima, who is on the Autism Spectrum, realizing that she too needed a life that was focused on her and a support community that would be there for her when Aparna was no longer around. Thus, Project Arunima, a program offering residential services and opportunities to build skills, was born in 2011. It is a one-of-a-kind program that aims at providing opportunities for a life of independence and dignity for people who are differently abled. What makes it one-of-a-kind? In a nutshell—the recognition that different is not less, but equal! Aparna is passionate about creating these opportunities for a good life to ensure that each person is a valued member of the community.

Sudha S. Nair is passionate about the work she does alongside people with disabilities She has been in the field of Special Education for the last 27 years, the last 17 years especially in Inclusive Education. She has had the responsibilities of setting up an Autism Unit in a Special Needs Centre as well as a Learning Support Unit in a Mainstream School during her employment in Dubai. As a self-employed professional in India, she has been actively involved in working side by side with parents as well as school educators and counselors to work for and champion her neurodiverse students. Her introduction and further exploration of the themes of SRV has added a valuable dimension to her commitment and thinking, especially while designing programmes for her students.

She has recently founded the SuDhi Learning Centre which aims to be a training hub as well as to co-create shared spaces for belonging and interpersonal identification in the community. She attended Social Role Valorization 3.0 in 2019, and has been an active member of the All -India SRV Association since its inception. She has had a great deal of experience incorporating SRV thinking into her work, and has introduced many others to the ideas.

She loves reading (or should we say, collecting books!), pottering around her little garden, playing with her two adorable pets, dabbles in sketching, when she isn’t working or being brought up by the two young ladies, she gave birth to.

Grace Daniel joined Keystone Institute India as the program lead for inclusion and communication.

Professionally Grace is a Special Educator with over two decades of experience. She is passionate about inclusive schooling. She serves as the Founding Director of I Care Rehabilitation Center, an inclusive NGO that works with children and adults with disabilities and provides educational opportunities for underprivileged girls and people who did not complete school or college.

Grace is a creative and artistic person who serves as graphic facilitator with Keystone Institute India. She has an excellent ability to take words and thoughts and organize them to create a beautiful visual expression of the process of discussion, a visual treasure.

After completing the comprehensive Social Role Valorization (SRV) course in 2017, Grace has been actively involved in implementing the concepts of Social Role Valorization in the various areas of her work. Grace has been working closely with the KII team and Betsy in the PATH planning process for individuals and organizations and also in taking up training workshops for educators and people involved with community services. Grace had initially also been involved in translation of the SRV teaching material from English to Hindi. Certified by Keystone Institute India, Grace is also a master trainer for the Foundations of Direct Support Practitioners (FDS).

Having a vision of making our educational system a better place for children with disabilities and as an inclusion activist, Grace has also been involved in teaching and training educators across schools and colleges on the concepts of SRV and practical inclusion.

Shabnam Rahman is a consultant Rehabilitation Psychologist and Special Educator. Her work includes consulting with individuals experiencing intellectual and developmental disabilities, children, young persons, caregivers and families in responding to a range of issues related to mental health and school related challenges. She loves to co-create emotional safe spaces for people to explore preferred identities. Her clinical approach focus is on Narrative practices and Ideas.

Presently Shabnam is working as a consultant Rehabilitation Psychologist and Special Educator at Crystal Minds, Kolkata and also pursuing a Ph.D. in Applied Psychology from University of Calcutta.

She uses SRV informed strategies in my workspace to enhance the competency and identity of the person to lead a dignified and meaningful life.

She believes in co-creating emotional safe spaces with people to explore preferred identities, possibilities and hope through meaningful experiences. Shabnam also believes that SRV is the “HOPEFUL MAP” that brings possibilities and changes within the lives of devalued people by engaging them in valued social roles to experience the good things in life that are available in their community.

Keystone Institute India is a programme launched by Keystone Human Services International, USA and it provides extensive consultation and education around developing responsive, effective, and inclusive supports to help move toward belonging, acceptance, and a rich community life, especially for people with developmental and psychosocial disability and their families. Together with forward-thinking allies across the country, we are working to develop an inclusive society, where all people belong and are invited to participate in all the community has to offer. We believe that diverse and welcoming communities experience the gifts of all their members, and that such communities have much to teach us about how to live in harmony together.

We hold important values when it comes to assisting people with disability to lead dignified lives marked by belonging, freely given relationships, personal growth and richness. This commitment, shared with our partner the Rural India Supporting Trust, led to the launch of Keystone Institute India in 2016, a valuesbased national training institute to facilitate broad-based approaches to elevating the possibilities for people with developmental and psychosocial disability to lead full and rich lives.

9 We develop and prepare emerging leaders to work toward integrated community development instead of segregation.

9 We offer intensive workshops and presentations on promising practices and ideas, consultation, and guidance in implementation strategies.

9 We connect organizations and people throughout India and the world who are doing promising work to assist people with disability to take their place in society.

9 We conceptualize and help design responsive service models based on a model coherency framework and stakeholder collaboration.

We strive to serve as a catalyst for developing a service system in India that better safeguards vulnerable people, respects the voices and perspectives of people with disability and their families, and facilitates India’s movement toward a society where all people can explore their possibilities and reach their potential. From our deep experience, we know that inclusion benefits everyone. We have a vision of an inclusive world where all people belong, and each person can shape their own life according to their personal goals. Choice matters. Dignity of risk makes a difference. We do our job best when we listen to people’s voices and add our voice to the growing movement for inclusion for all people:

9 We offer access to world-class and national experts on inclusive practices and idea sets which support and promote a full community life for all people.

9 We seek those across India with passion and know-how to join together towards change.

9 We mentor and develop next-generation leadership to take the ideas forward and put them to good use.

9 We promote full citizenship and voice for people with disability and their families to experience full, rich, included lives.

Keystone has purposefully kept our own staff small, as our strategy has been to build strength and competency across India through the development of Communities of Practice. Mentoring and coaching to develop masterful teachers in idea sets, as well as masterful implementation, has led to both a strong national collaboration of leaders as well as a regional and state collectivity committed to working together and separately for change. a CoMMItMent to CoMMunIty

We have a passionate belief that the institutionalization of people with disabilities in segregated facilities must be resisted, and that communitybased services must be developed in conjunction with public and private organizations which share that commitment. Besides providing consultation and training across India on creating high quality residential service, Keystone has joined with service not only to the women, but to the community that has been enriched by their presence.

Keystone makes sure that the ideas are translated into action, on the societal level, the community level, the organizational level and the family/individual level. After all, we teach powerful idea sets which people need support to interpret and use.

We believe that everything must contribute towards building capacity and effecting lasting change. This goes well beyond just training. Partnerships with government are a part of strengthening the fabric of the support network across India to elevate and safeguard the lives and wellbeing of people with disability.

Leadership development is another important strategy to develop lasting change, and we focus a great deal on cultivating leaders and master trainers across the country. As well, strong collaborative relationships have been developed amongst the networks of leaders.

Keystone Institute India takes the work of developing a more inclusive Indian society as a serious responsibility and holds that responsibility with great care. We share a belief that people with disability have a great deal to teach society about how the world can ‘work’ for everyone.

Face-to-face events are held across the country, and our complete schedule can be found on our website. Join the national conversation around Social Role Valorization, person-centered support, tools for inclusive practice, customized and supported employment, and best practices in residential support.

Virtual on-line events and study groups are another way to connect with our network.

See Jhalak, an online compendium of the small but potent changes that people and organizations have put the ideas we promote into practice.

Ms. eLIzabeth “betsy” NeuvILLe Executive Director eneuville@khs.org

Ms. Geeta MoNDoL Director of Community Programs gmondol@khs.org

DR. IMRaN aLI Director of Administration mali@khs.org

Ms. LeeLa Raj Project Leader Curriculum Design, Customized Employment and Advocacy lraj@khs.org

“Community is much more than belonging to something; it’s about doing something together that makes belonging matter.”

- Brian Solis

The enablement, establishment, enhancement, maintenance, and defense of valued social roles for people –particularly those at value-risk by using, as much as possible, culturally valued means

Home

School

Work Relationships Recreation/Leisure Spiritual

The attribution of low, or even no, value to a person or group

By another person or group

On the basis of some characteristic

12. Loss of natural, freely-given relationships and substitution of artificial “paid” ones 13. De-individualization 14. Involuntary material poverty

15. Impoverishment of experience, especially that of the typical, valued world

16. Exclusion from participation in higher-order value systems 17. Having one’s life wasted

18. Brutalization and “Death-making”

19. Awareness of being a source of anguish to those who love one

20. Awareness of being an alien in the valued world, deep personal insecurity

The attribution of low, or even no, value to a person or group

By another person or group

On the basis of some characteristic (usually a difference)

Devaluation is not the same as:

Being rude, impolite, discourteous

Disliking a person

Making demands upon a person

Wealth, material prosperity, material goods

Health & Beauty of body

Youth, newness

Competence, independence, intelligence

Productivity, achievement

Individualism & unrestrained choice

Hedonistic / sensualistic pleasure

Wealth, material prosperity, material goods

Health & Beauty of body

Youth, newness

Competence, independence, intelligence

Productivity, achievement

(Adult) individualism & unrestrained choice

Hedonistic / sensualistic pleasure

Non-Human A. Not Yet Human

B. No Longer Human

C. Sub-Human: Animal, Vegetable, Object D. “Other”, Alien

VirtueSin / Diabolicness / Evil

Irresponsibility

Criminality / Corruption

Pity / Charity

Attractiveness

Ugliness / Disorder

Darkness / Blackness / Shadow

LifeRelated Illness / Death

Incapacity/Impairment/Weakness

Cold

Old

Decay

Subhumanity

Incompleteness / Brokenness

Quality/ Place Poverty

Dirty

Bottom / Down / Low

Back Left Last, End Out

Worthlessness / Discardable

Virtue / Angelicness / Divinity

Responsibility

Lawfulness / Morality

Respect / Entitlement

Beauty / Order

Light / White / Bright

Health / Vitality

Strength / Power

Warm

New / Youth

Growth

Humanity

Wholeness / Completeness

Wealth

Clean

Top / Up / High

Front / Forward

Right

First, Beginning In Value

Institution for people with mental illness

Day Care Center for children with developmental disabilities

Home for neglected or abused youth

Children’s treatment facility

Hospital for children

Rehabilitation Group Home

Drop-in/ Day Center for people who are elderly

Alcoholism Clinic

High rise for the elderly

Regional center for People with mental illness

Submarine sandwich shop staffed by people with developmental disabilities

Name

Battey State Hospital

Looney Day Care

Whipper Home

Dysfunctioning Child Center

St. Jude’s Hospital

Last Chance House

Bleak House

Bahr Treatment Center

Toomey-Abbot Towers

Madden Zone Center

The Subnormal Sandwich Shop

Home for newborns and children with disabilitiesHoly Innocents, Inc.

1. Using value-tainted locations and facilities

2. Grouping devalued people in image-impairing ways to each other

3. Applying value-impairing methods, activities and structures to devalued people

4. Giving devalued people comical, bizarre or negative names and labels

5. Giving comical, bizarre, names and logos to agencies and services to devalued people

6. Neglecting the personal appearance of people

7. Funding services to devalued people with image-tainted monies or devaluing appeals

1. Being scapegoated for anything bad that has happened

2. Being suspected of belonging to more than one devalued group

3. Being cast into more than one deviancy role

4. Being treated worse for an offense than are valued people

5. Upon being vindicated, receiving less restitution

A. Physical Exclusion

B. Physical Segregation: Separate Facilities and Groupings, Institutions, Ghettos, Reservations

C. Physical Confinement: Prisons, some Institutions and Nursing Homes

D. Physical Ejection: Banishment, Expulsion

E. Physical Destruction: Deadly Assault, Capital Punishment, Abortion, “Euthanasia”, Genocide

A. Avoidance of Interactions

B. Using Language and Negative Imagery for Social Degradation:

1. Age Degradation

2. Status-Degradation

1. Being made/ kept in dependency to Individuals, Agencies, or the Service Structure generally 2. Having to Deal With, and Report to, Offices, Agencies, Authorities

Having to Fill Out Forms –often without being able to cope with such

1. Often, the cause of a devalued person’s physical discontinuity is rejection by those in control of the person

2. Devalued people get moved around much more often even within the same locale, agency, and facility

3. Devalued people frequently get moved:

A. Against their will and without their consent

B. With little or no prior notice

C. As “punishment”

4. Devalued people commonly get moved in ways and for reasons which are chaotic or bizarre, but which are almost always interpreted as being “for their own good”

5. As a result of a discontinuity, a devalued person’s situation is more likely to worsen than improve

6. Devalued people have few possessions to connect them with the places where they have been, and/or are often unable to bring possessions with them when they are moved

7. Devalued people often do not have the resources and competencies of valued people to cope with discontinuities, and to maintain contact with places where they have been, and with people in those places

Disorientation, confusion, and therefore, lowered performance

Insecurity

Loss of possessions

Relationship Loss

Stress, often leading to illness and death

1. Widespread negative societal attitudes towards poor and otherwise devalued people

2. Oppression and exploitation of devalued, weak, powerless, poor, and disabled people by powerful and wealthy interests

3. Exclusion of devalued people from societal participation and benefits, in good part via segregation and congregation

4. Unemployment built into the economy in order to keep it stable

5. Teaching and reinforcement of dependence and low competence in devalued people by society and human services

6. Systematic societal patterns of transferring wealth from the lower to the upper social strata

1. Systematic Medicalized Abortion of Impaired Unborns 2. Active or Passive MedicalizedKilling of Impaired Newborns 3. Increasing Move Toward Withholding / Withdrawing of Medical Supports from Long-Term Medically Dependent People 4. Systematic Withdrawal of Healthcare from the Poor

5. Systematic and Large-Scale Placement of Devalued People on Prescription Psychoactive Drugs

6. The Abandonment of the Ghetto Populations to Street Drugs

7. “Dumping” of Disabled People into Unsupported and Abandoned Community Living, where Such Persons can End Up on the Street, in Jail, and Victims of Violence

8. Systematic Promotion and Facilitation of Suicide by Troubled and Dependent People

Searching for the abandoner

Fantasy & inventions about positive relationships that do not exist

Seeking physical contact, perhaps insatiably

Testing of the genuineness of personal & social relationships

Withdrawing from human contact, perhaps even from reality

Turning the hurt into resentment/hatred

Rage, perhaps violence, at the world or self

A sapping of energy –both physical & mental

1. Some wounds are struck by nature, but all can be inflicted by people

2. Being devalued places one at highest risk of suffering any or all the other wounds

3. Not all wounded people get devalued

4. There is much universality about the wounding process & its transaction

5. There is a predictability about the sequence of wounds

6. Few people are conscious of the wounding dynamics and their consequences

7. People do not appreciate the role of human services in wounding

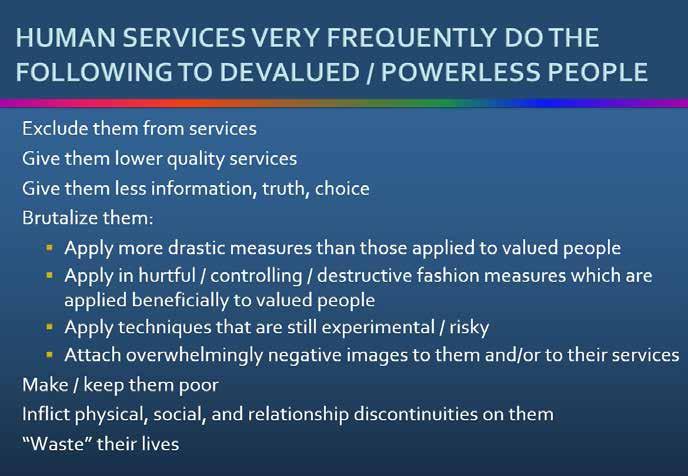

A. Being devalued often puts one into human services

B. Human services play a huge role in inflicting wounding experiences

C. There is vast unconsciousness & denial in human services about the wounds and the human service contribution to them

D. The public often sees the wounds differently than people in human services

8. The cycle of wounding also damages society and the wounders

9. Wounds must be deeply understood in order to take action on them.

1. An entire class in society is systematically and severely mistreated by the majority or ruling class

2. The mistreatment virtually always involves:

a. Impoverishment

b. Denial / Diminishment of political voice and power

3. Over the long run, most members of the class at issue experience a quality of life that is much below that of those who are not mistreated

1. To change perceptions of perceiver so positive social judgments will be made

2. To assist people with a devalued status to have a full and meaningful life –“The good life”

A social role may be defined as a socially expected pattern of behaviors, responsibilities, expectations, and privileges

Observer, deeply influenced by various factors

Observer’s own characteristics & experiences, including expectation from previous contacts with observed person/group

Characteristics of observer’s physical environment (e.g., deprivation, stress)

Characteristics of observer’s social environment (e.g., values, expectations, norms, conventions)

Person/ Group observed

What is actually observed (i.e., another person’s/group’s “appearance”or behavior

Image in eyes of others –status and reputation

Image in own eyes –self-image

Acceptance and belonging

Associations and relationships

Autonomy and freedom

Personal growth and development

Opportunities

Material side of life

Lifestyle

The enablement, establishment, enhancement, maintenance, and defense of valued social roles for people by using, as much as possible, culturally valued means

The application of empirical knowledge to the shaping of the current or potential social roles of a party (i.e., person, group, or class)

primarily by means of enhancement of the party’s competencies & image

so that these roles are, as much as possible, positively valued in the eyes of the perceivers.

Culture-appropriateness / Cultureinappropriateness

Age-appropriateness / Age-inappropriateness

A. Which can be encountered with reasonable frequency in the valued sector of society.

B. With which most members of society would be familiar.

C. Of which most members of the society would hold most positive expectations.

In other words, “What happens for people who have a societally valued status?”

(From Wolfensbergerand Thomas, 1983)

Level 1: The individual

Level 2: The primary group: family, communality, any small close-knit group

Level 3: Secondary social systems: neighborhood, local community, service agency

Level 4: The society, either as a whole, or at least in broad cross section

1. Conflicts between higher ideals and baser drives result in repression into unconsciousness of impulses and beliefs judged as “unworthy”

2. Much learning is unconscious

3. Gradual attrition over “generations” in the conscious interpretation and affirmation of rationales for practices

4. The more complex a phenomenon is the less intelligible it is to humans

5. The natural tendency of formal organizational processes is toward lowered consciousness

6. Systematic modeling, even exaltation, of unconsciousness and systematic extinction / punishment of consciousness

A. To human nature:

1. Fear of the unknown

2. As part of “tribalisms” that support internal cohesion at the cost of defining outsiders as deviant

3. As part of the social stratification encountered in all societies

B. The price of social order rests on negative interpretation of people who violate others and the law

I. Need for attainment of identity and security by defining and defending the self in terms of what constitutes:

A. Humanness

B. Worth

C. The social boundaries of society and social groupings and what lies beyond

II. Stratification, status, and privilege, especially in the realm of:

A. Economics, which commonly means that some people must be made / kept poor to assure that:

▪ Rich can stay rich

▪ Poor will perform necessary but unpleasant chores

▪ Livelihood of “deviancy makers” is assured

B. Class, status and power enhancement, regardless of economic advantages

III. Need for tension release, especially in times of stress, by:

A. Explaining phenomena that are complex, and possibly otherwise unintelligible, as having been caused by “deviant” people

B. Legitimizing mistreatment of those blamed, thereby releasing frustration

II. Many religious and socio-political ideals to which people assent prohibit the devaluations that flow inevitably from the negative interpretations

III. This leads to a clash between people’s ideals and their true feelings and actions

IV. In order to resolve this clash, devaluing sentiments judged unworthy by the idealized conscience are driven “into hiding” in the unconscious

V. Unconscious repressed feelings ceaselessly press for release

VI. If not expressed directly, they inevitably emerge indirectly (e.g., symbolically) BAD

A proposition that follows from another that has already been proved; an inference or deduction; anything that follows as a normal result

Making available the most valued option on behalf of a person who has a devalued status

I. Most people have at least some wounding experiences in their lives.

II. However, there are some crucial differences between valued people and devalued people

A. Devalued people exist in a state of “heightened vulnerability”

1.They may be members of a group or class that is collectively, stereotypically devalued

2.Many have experienced long-standing wounding and degradation

3.They may have never been accorded valued status or class

4.They are more likely to suffer multiple wounds and stressful lives

5.They are likely to continue to be subjected to relentless, repeated wounding, to the point of deathmaking

B. Wounds inflicted on vulnerable parties have much more serious, long-term, pervasive impact than the same wounds inflicted on a relatively non-vulnerable party

C. Some practices that are normative (or even enhancing) to people of the valued culture may be harmful if engaged in by a devalued / vulnerable party because the measure in some way further heightens that party’s initial vulnerability

1. The more vulnerable a person is, the greater is the need for, and the positive impact of:

A. Preventingadditional wounds

B. Reducingexisting devaluation, impairment, or other vulnerability

C. Compensate –even “bending over backwards” –to balance off the vulnerability or devaluation

2. When there is a range of options for enhancing social image or personal competency (or alleviating vulnerability) the more valued and least “risky” measure is the adaptive one.

LESS COMMON, AND NEGATIVELY VALUED

STATISTICALLY COMMON

TYPICAL PREVALENT

LESS COMMON, BUT HIGHLY VALUED

1. The most valued option may not be feasible

2. Valued measures for valued people can sometimes become devaluing when applied to already devalued / marginalized people

3. The value attached to certain measures sometimes varies according to context

4. Some measures may conflict with each other in certain situations

People who identify with others will generally:

Want good things for the others

Want to be with the others

Communicate good things about the others

Want to please the others; do what they ask

Possibly want to be like them

1. Getting privileged people to see themselves in people who are devalued or at risk

2. Getting devalued people to identify with persons of adaptive identity, and look to them as models

1. Improving the approachability of each party by the other

2. Improving the likelihood that when contact occurs, it is positive

3. Finding and emphasizing commonalities shared by the parties

4. Engaging each party in experiences will help them see the world through one another’s eyes

5. Fostering each party’s sense of responsibility for one another

6. Engaging in shared experiences, particularly intense shared experiences

First Impressions

Experienced early in life

Intense

Confirming of earlier stereotypes

Dramatically counter to expectations

1. Help people at risk of devaluation avoid becoming trappedin negative role circularities

2. Embed persons at risk into positive role circularities

3. Help people who are trapped in negative role feedback loops to break out of these

4. Help such people to enter positive role circularities

1. A person is in a new/ unfamiliar situation

2. There are positive role models in the environment

3. The people giving the role expectancy messages do so with authority and expertise

1. Imposing inconsistent roles on a person

a. Within a service

b. Between or among services

2. Taking away devalued people’s meaningful and positive roles

3. Imposing roles mainly to benefit

a. Other people

b. The service

4. Imposing destructive roles

5. Inappropriately taking roles away from people that they may be afraid to give up

1. The devalued person’s role models are likely to be mostly devalued / negative ones

2. Almost all environments for devalued people convey negative role expectancies

3. The devalued person is apt to receive negative role messages from almost all the people s/he encounters

4. Devalued people have usually been socialized into negative roles over a long period of time

5. The devalued person may feel very insecure in any other role other than a familiar (negative) one

1. Practice consciousness of the meaning and use of role communicators

2. To the degree that a person has been role-diminished, try to bestow positive roles or role elements

3. In new situations:

a. Immediately impose positive, demanding expectancies

b. Have positive role models in place

4. Associate persons who have been role-diminished with people in high-status roles

5. Choose and support roles which confirm a person’s positive / special identities, talents, gifts

6. Add value to roles by Clarifying and recognizing positive elements in each person’s role(s)

7. Construct roles and role communicators of / for service workers

1. An image message enlarges or reinforces a pre-existing mind-set, stereotype, expectancy

2. It is conveyed by multiple communication channels

3. It impacts on the unconscious of receivers

4. It is sent out relentlessly

Characteristics of the Physical Setting:

Internal &/or external appearance aspects:

▪ Harmony with neighborhood

▪ Consistency with culturally valued analogue

▪ Beauty, upkeep, & seasonal appointments

▪ Age-appropriateness

Location / Proximity

History

Social Juxtapositions, Associations, & Groupings:

People served, perhaps as clients

Paid or unpaid servers: staff, volunteers, others

Personal Imagery:

Appearance

Possessions

Autonomy and Rights

Language:

Personal names and labels

Service names and labels

Setting and location names

Activities, Time Use, & Rhythms:

Types of activities and services

Combination / Separation of functions

Schedules and routines

Miscellaneous Service Aspects

Administration and law

Funding

Symbols and logos

Cultural expectations & stereotypes 3-WAY MATCH

The age of a person or group

The activities & activity timing of a person or group

1. There is a great deal of unconsciousness, and relatively little consciousness, in all human endeavors

2. Symbolic communication is very “primitive” behavior, with many symbols deeply rooted in the “collective unconscious”

3. Totality of what symbols used to mean and therefore the messages they still carry, is often unknown or forgotten

4. Inconsistency in beliefs or values leads to repression of less “noble” belief of value; whatever is repressed in unconsciousness seeks expression, usually symbolically

5. Symbolic communication is often directed towards the receiver’s unconscious

6. Even when they impact strongly, symbolic communications are difficult to decode (in part because of all the above) and are therefore

1. Expresses social devaluation largely in the realm of the unconscious

2. Teaches that a group should be devalued:

a. Massively, to many people

b. Over generations

c. In a way that can still allow people to continue to give lip service and token obedience to higher ideals

3. Ensures that devaluation will never be fully recognized and rooted out, even within any one individual

4. Confirms devalued status of victim(s) in their own eyes and those of society

5. Legitimizes Distantiationand segregation

6. Freezes devalued people into negatively valued and competencydiminishing roles

7. Legitimizes, and even invites, brutalization, even genocide, of negatively-imaged persons / groups

8. Enables real social policies of devaluation, hatred and oppression to be perpetrated, despite recurring efforts to remediate the victims’ plight

9. Raises a lot of money

1. Image issue doesn’t exist; negative juxtapositions are coincidental or selectively publicized

2. People do not notice images

3. People do not respond to imagery

4. People should not notice or respond to (negative) imagery, and therefore, imagery need not be addressed

5. Image enhancement of devalued people is “merely cosmetic” and thus lacks reality or import, or is even phony

6. There is no connection between deviancy imagery and other devaluations of devalued people

7. Benefits of some negative images far outweigh the cost (e.g., in fund raising)

I. Fundamental, often unconscious assumptions and theories about:

A. The nature of the world and the meaning(s) of life

B. The nature of human nature

C. Problem parameters

1. Definition

2. Cause(s)

3. “Solutions”

II. The people receiving the service

III. The program “content” (i.e., what is given or done to the people)

IV. The program “processes” (i.e., how the content is rendered):

A. Methods used, including setting

B. Language adopted and used in and about the service and to and about the people

C. How people are grouped to receive the content

D. Identity of the servers (i.e., the “workers”)

Who are the people to be served;

What do they need;

And how should what they need be delivered:

Using what methods,

In what settings,

In what kind of grouping,

By what servers,

& how should all of this be talked about?

Dir ections of Coher ency

Methods Gr ouping

Wor kers Langua ge Setting Identity & Needs

1. Relevance: Precise matching of service content to recipient’s needs

A. Major issues and needs are correctly identified and addressed

B. Wherever a measure tries to address the needs of more than 1 person, relevant focus for each person is preserved

2. Potency:

A. The most effective processes are used for conveying a content

B. A recipient’s time is used with intensity and efficiency

Relevance:

What Do Recipients Need?

What Do They Need More than Other Things?

Are They Getting It?

Potency:

What Are the Most Powerful Ways of Delivering the Content?

1. Relevance: Precise matching of service content to recipient’s needs

A. Major issues and needs are correctly identified and addressed

B. Wherever a measure tries to address the needs of more than 1 person, relevant focus for each person is preserved

2. Potency:

A. The most effective processes are used for conveying a content

B. A recipient’s time is used with intensity and efficiency

3. In implementation, no avoidable harm is inflicted

Bodily integrity & health, and the capacity to protect & maintain these

Bodily competence: strength, agility, stamina

Self-help skills

Capacity to project a positive personal appearance

Communication

Intellectual ability, skills, habits & disciplines

Motivation, initiative, and drive

Competent & responsible exercise of personal autonomy & control

Adequate volitional control over one’s impulses & movements

Confidence, self-possession

Social & relationship competency

Unfolding & expression of self, individuality

I. Humans achieve greater well-being via consciousness, activity and engagement, than via idleness, incoherency, alienation

II. Human being have vastly more growth potential than is:

A. Realized by most people

B. Elicited by many role definitions and expectation and by most human services

C. Apparent in a specific individual: The full growth potential of a person cannot be predicted; it only becomes apparent when the person’s life and growth conditions are optimized

1. Challenge, not mindless, endless pleasure

2. Work, not idleness

3. Work that can be understood

4. Meaningful relationship to

a. One’s origins, belongingness, sense of continuity about one’s life

b. Stable primary groups, not transient alliances

c. The larger culture

5. Natural consciousness of self and social processes, not a drugsustained consciousness or unconsciousness

6. Inspired commitment to society

1. Generally, a suitable service is potentially more impactful:

a. The earlier in life it is begun

b. The sooner after onset of an impairment or vulnerability it is begun

c. On people who are severely impaired, more so than mildly impaired

2. If relieved from fears, insecurity, anxieties, and other personality constrictions, people with disabilities can show dramatic gains, even in measured intelligence, anytime during their lives

3. People should be afforded the least restrictive service (i.e., neither more services nor restrictions should be imposed than that person needs)

4. Vastly more knowledge and technology exists about how to advance people toward their potential than is known by, or utilized in, any one service; therefore, no matter how good any service / agency is there exists a better way

1. The assumptions and implications of the developmental model are of universal relevance to:

a. People of all ages and degrees of ability

b. All types of services: educational, habilitation, residential, medical, correctional, etc.

2. Because developmental potential is more often underestimated than overestimated, one should always be aggressive in one’s expectations of what a person can learn, achieve, become

3. Next to sheer maintenance of life, a developmental approach / model is probably the most important requirement of a human service

4. Social Role Valorization is one of a number of embodiments of the developmental model and is probably the most systematic of these

1. Learning or Acquisition: Acquiring new skills & competencies 2. Performance: Utilizing the skills & competencies already possessed 3. Knowledge: Cognition, understanding 4. Skill: Ability to use knowledge one possesses

5. Habits & Disciplines: Things one does routinely, customarily

1. Reducing obstacles to an expanded behavioral repertoire:

a. In the physical environment

b. In the social environment

c. In/of the body

a. Directly

b. Indirectly, via prostheses and orthotics

d. In the mind: mindset, motivation, etc.

2. Actual facilitation of functionality through

a. The physical environment

b. The social environment

c. Other teaching practices

C. Use of competency-enhancing personal material supports and equipment

D. Physical setting features (as applicable) that promote person’s growth:

1. Easily accessible setting

2. Located amidst resources that provide opportunities for competency development

3. Physically comfortable

4. Competency-challenging environment that is neither over-nor under-protective

E. Promotion of establishment of culturally valued:

1. Autonomy and rights

2. Interpersonal interactions

3. Socio-sexual identity

MODEL / DEMONSTRATOR IDENTITY

One or more persons who can / will perform desired behaviors

Has characteristics that learner admires, valued, aspires to,identifies with

Actually, perhaps habitually, performs behaviors

Models, or “facsimiles” thereof, present in sufficient numbers in learner’s environment

Models / facsimiles perform behaviors, perhaps repeatedly, habitually, or exaggeratedly, while learner is attending

If necessary, learner is prompted to imitate

Learner is reinforced for ever closer approximations of demonstrated behaviors

Models may also be reinforced

Learner “rehearses” behaviors

Capacity to imitate, at least in approximation

Opportunity to imitate

Awareness of: environment; others & their behaviors; own behaviors

Open / susceptible to learning new / alternate behaviors

Positive view of, identification with love for the model

A. Failure to recognize the power of imitation:

1. Substituting an inferior pedagogy

2. Failure to recognize its power in reference to a specific group

B. Acknowledgement of its power with a specific group, but explicit rejection of its use

1. For ideology-related reasons

a. “Because the world is full of bad models”

b. Perverted individualism and relativism: “Everyone should do their own thing”

c. “It will bring competency-impaired learners to frustration, anger, or poorer self-image”

2. For management reasons: “It costs too much, is too inconvenient”, etc.

C. Perverted applications of imitation strategies

1. Presenting negative models, whether intentionally or not

2. Mistakenly reinforcing negative imitating

3. Encouraging the practice of fixating a person on the superficial imitation of an admired model

4. Abdicating all other pedagogies after bringing in good models

1. Know its power

2. Be mindful of the contributions and inspiration received from great models

3. Identify what to model

4. Interpret to relevant others what should be modeled

5. Discern good models

6. Surround others, especially vulnerable persons, with good models

7. As much as possible, protect devalued / vulnerable persons from exposure to bad models

8. In situations that are new or equivocal to the learner, have positive models in place from the start

9. Promote people’s sense of identification with persons who are good models

10. Reinforce positive imitation

11. Be a good model oneself to devalued persons, service workers, advocates, families, and the public

1. Helps eliminate life-wasting of devalued persons

a. Helping to thwart life-defining and externally imposed role stereotypes

b. Facilitating transmission of common widely-known experiences

c. Helping the acquisition of vital, life-sustaining skills

2. Enables a devalued person to perform in more valued ways

3. Natural, powerful process and thus:

a. A fairly painless way to learn

b. Generally inconspicuous and not image-tainted

Adaptive participation by a (devalued) person, In a culturally normative quantity of contacts, interactions, & positive relationships, With ordinary citizens, In normative shared activities, that are part of recognizable roles, and Carried out in valued (or at least ordinary) physical & social settings.

A. Terms with multiple meanings

B. Perversions of personal social integration

1. “Dumping” a devalued person into society

a. When the person lacks adequate abilities to cope

b. Without support systems

c. Into community areas already saturated with other (services to) devalued people

2. Denying people needed special services

3. Serving a wide variety of devalued people within the same setting

C. Concepts, which are possibly valid, but not the same as, personal social integration

1. Coordination of agencies, administrative departments, etc.

2. Co-locating of various services to devalued people

3. Locating programs for devalued people within the community

4. Using generic services non-integratively

I.Benefits to integrated (devalued) person:

(1)A.Protection of person’s welfare / safety, in that hurtful practices thrive more commonly in segregated settings for devalued people

(2)B.Enhancement of (devalued) person’s competencies

1.Services in open settings are more likely to be of higher quality

2.Greater opportunities in open settings to: a.Learn or perform, because:

(3) i.Integrated physical settings are more likely to be normative and to elicit normative behavior

(4) ii.People are likely to hold normative expectancies for those whom they encounter in more normative settings, which in turn elicits more normative behaviors

(5) iii.People respond positively to normative behavior, which is thus reinforced and strengthened (6) iv.Greater access to valued (peer) models / modeling, making appropriate imitation more likely (7) v.Typically, integrated settings afford a greater variety of experiences (8) b.Exercise autonomy, choice, freedom, and citizenship privileges (9) c.Meet a wider range of people, and form mutually satisfying relationships

C.Enhancement of (Devalued) person’s social image, via greater likelihood that: (10)1.The image of valued actors in a setting will transfer / generalize to an integrated (devalued) one (11)2.Services are more likely to be based on right rather than pity / charity

(12)D.Strengthened self-image

I.Benefits to other interested parties:

A.Benefits to person’s family and other close supportive relationships, if any

(13)1.Reduced motivation to be ashamed, to deny the person’s existence or one’s relationship to the person (14)2.Via person’s enhanced competencies and image, opportunity for more normatively inclusive (family) events and celebrations (e. g., weddings, holidays)

(15)3.Greater likelihood that the family will develop contacts with families of the non-disabled/ non-devalued assimilators

(16)1.Greater likelihood that the devalued person will contribute to society

2.With proper modeling, interpretation, and supports, integration with disabled / devalued people: (17) a.Gentles people (18) b.Broadens society tolerance of differentness (19)3.Often (but not always) cheaper than segregated settings / services

1. Idealized values of every major faith tradition(e.g., acceptance, compassion, mutual assistance, selfsacrifice, mutual submission)

2. Basic idealized socio-political values of equality and civic participation

Setting / Facility Appearance:

FACILITATOR OF PSI/VSP

1.Facility & ground sizeNormative

2.Match with neighborhoodAppearance harmonizes with neighborhood

3.Match with appearances of valued settings for conducting analogous functions

4.Physical features

5.Aesthetics

6.Appropriateness to ages of people being served

Service match with neighborhood:

Appearance congruent with that of valued analogues

OBSTACLE TO PSI/VSP

Non-normative, usually too large

Appearance clashes with neighborhood

Appearance does not match that of valued analogues

Positively imagedNegatively imaged

Beautiful, comfortableUgly, unattractive, barren

Age-appropriate design & décor

Service type harmonizes with neighborhood character

Age-inappropriate design & décor, usually too young for people served

Service type clashes with neighborhood character

Settings:

Access, surroundings, resources

Appearance, history, aesthetics

Groupings:

Size, congregation

Composition

Images (messages):

Personal appearancesWorkers

Names, labels

Activities

Symbols

Do they help or hinder social integration?

Do they invite acceptanceor rejectionby other people?

I. Address characteristics and conditions of devalued persons which are apt to elicit rejection from others, and therefore to prevent / inhibit integration

A. Reduce anxiety-and rejection-provoking personal characteristics of devalued persons

B. Encourage, develop and instill valued social habits

C. Disperse devalued people and services throughout the community and neighborhood

D. Surround with positive images

E. Foster valued social roles for devalued people

II. Help potential integrators to identify with devalued persons

A. Find and emphasize backgrounds, interests, activities and involvements that devalued person and potential integrators share

B. Pair up devalued and valued person in cooperative tasks, at which the chances of success are relatively good (e.g., board / committee work, school projects, neighborhood clean-up)

C. Request / elicit / structure satisfying, direct, personal, helping involvements by valued person with devalued persons (e.g., citizen advocacy)

III. Reward and reinforce any integrative gestures or acts by valued persons (e.g., private commendations, comments to significant others)

Large Institution

Nursing Home

Regional Center

Large Group

Residence

Small Group

Residence

Apt. Complex

Sheltered Apt.

Foster Home

Boarding Home

Own Home

Independent

Apt.

Segregated building in segregated site

Segregated building in integrated site

Several special classes in regular school

Segregated work station in industry / business

1 or 2 special classes in regular school

Integrated work station in industry / business

Generic early education

Regular class

On-the-job training

Open employment

Large segregated groups only

Segregated facilities

Small groups, segregated in generic facilities

Large group vacations

Small groups, non-segregated generic facilities

Small group vacations

Individual hobbies

Speical integrated social clubs

Individual vacations

Generic social clubs

Individual integrated activities

Special segregated transportation only

Community shopping, but only in deviancy groups

Small deviancy group

public transport

Public transport only

Individual worship in generic church

Frequent integrated community shopping

1. Person’s competencies

2. Available supports (e.g., necessary services, consultants, people)

3. Likelihood of success (e.g., are potential integration facilitators in place)

4. Likely advantages of:

a. The person

b. Assimilators

c. Other (future?) devalued persons

d. Others (e.g., family)

5. Costs to:

a. The person

b. Assimilators

c. Agency

d. Society

We are for difference: for respecting difference, for allowing difference, for encouraging difference, until difference no longer makes a difference.

Valorization of the positive roles already held by a person

Averting a person’s entry into (additional) devalued roles

Assisting a person’s entry into new valued roles or to regain previous valued roles

Helping a person to escape devalued roles

Reducing the negative roles already held by the person

Exchanging devalued roles already held by the person for less devalued new roles

1. The terms “norm” or “normative” may refer both to what is typical and what is valued

2. Each theme of SRV is, and all of its imp lications are, interrelated and mutually reinforcing

3. SRV is a psycho-social scientific theory, with strong roots both in empiricism and in positive values, that is universally applicable to human services

4. SRV is a scientifically “elegant” theory

5. Two constraints to scope and utility of SRV are:

a. It is a secular theory of empirical domain

b. Potential benefits of SRV are deeply dependent upon positivenessof cultural values

6. SRV is not the same as normalization, nor is it the same as what others say normalization is

7. Normalization, and to a lesser extent SRV, has been subject to innumerable misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and outright perversions

I.Misinterpreting SRV:

A.SRV only shapes the environment, never tries to normalize the person, and therefore does not deal with clinical services to the individual

B.SRV only / primarily shapes the person rather than:

1. The larger service context

2. Society

C.Persons who are devalued must become “normal”

D.As long as a person’s image is positive, competency enhancement is unimportant

E.As long as a person possesses competencies, image enhancement is unimportant

II.Taking one SRV element out of context, or over-emphasizing one to the exclusion of others, perhaps because of a previous misinterpretation:

A.Any behavior on the part of the devalued person, any appearance, or activity, etc. is accepted because free choice and individual differences “are normal”

B.Freedom of choice is the epitome of SRV

C.Anything can be applied to devalued people as long as it is normative for / among valued people

D.Devalued people are permitted –even encouraged –to participate in the perversions of the larger culture (drug use, sexual promiscuity, etc.)

E.Total immersion of person into all aspects of typical community life, without thoughtful regard for individual capacities or available supports

F.Tortuous avoidance of language that describes or denotes that a person or group has an impairment or devalued condition

G.Failure to recognize / utilize multiplicity of Social Role Valorizing options

III. Miscellaneous:

A.Devalued people are not devalued, or at least, one should pretend they are not

B.SRV is only another name for normalization; the 2 are the same

“Where there is passion, there is hope.”

- Wolf Wolfensberger

Our purpose is to provide national leadership for the teaching, study and use of Social Role Valorization as a unifying idea set among stakeholders across India who are seeking a more just and unified society for all people, particularly people experiencing disability.

All of those people from India and neighboring south Asian countries who have completed advanced training courses in Social Role Valorization (of at least 28 hours duration) in India taught by a senior trainer are considered members of AISRV Network. Active members will have many ways to interact and participate with the Network. Others may simply keep informed of what is happening across India and contribute as they can. Many members have a particular interest in the well-being and uplifting of people with developmental and psycho-social disability, but we welcome SRV graduates who are focused on cross-disability issues and other marginalized peoples.

! We serve as the core team of SRV Leadership across India and within south Asia

! We share information across our network about upcoming events and opportunities

! We “talent-spot” for emerging and promising new leaders

! We structure opportunities to take on activities including

y Writing and research about SRV and its use

y Developing training content together

y Learning to teach SRV

y Participate in SRV-focused program evaluation

y Forming regional or local communities of practice

y Translating SRV materials into regional languages

Collaboration: We will work together to form the leading edge of SRV teaching and use across India, using our energies to build something important together. We will consider collaborating rather than competing as a way to put our values into practice.

Role Modeling: We will strive to be excellent role models for those we mentor and lead across India

Building Developmental Capacity: We will build the capacities of a new generation of change agents across India by identifying, mentoring, cross-training, and supporting a cadre of emerging SRV leaders

who will help grow the movement. We will keep our eyes open for those who will join our work, and promote their growth and learning.

Commitment to Safeguarding SRV: We will protect the materials and their use by

! Making sure our focus within the Network is on SRV principles, and the connection to Social Role Valorization is explicit and named

! Properly attributing and citing all materials used in training or publication

! Work alongside, communicate, and share with senior trainers when SRV materials are adapted for use