Outcomes Measurement Report

From Custodial Ins tu ons to Community Lives – Are the People Be er Off? November 2023

Background

Community Lives is one of the first small‐scale deinstitutionalization efforts in India to pilot small community homes to support up to 8 women with intellectual disabilities to lead inclusive lives in everyday homes in the community. Six women left the government shelter home/institution in 2019. Prior to leaving the institution, seven scales measuring Quality of Life were taken to obtain baseline data. The same data scales were repeated at semi‐regular intervals: 6 months, 18 months, 34 months by the independent evaluators, to track progress, and now at 4 years.

One expected outcome of Community Lives is that the women living there will experience a higher quality of life in an integrated setting and with high quality developmental support.

In order to know if this is the case, the program design includes a component to measure aspects of the lives of each of the women before they move, and at intervals afterwards.

We used the Personal Quality Life Protocol (Conroy, 2017) consisting of 6 of the 9 scales, designed by Dr. James Conroy, specifically developed over 40 years for use in de‐institutionalization outcomes measurements, and used in many countries.

The instrument was used for each of the women we serve prior to leaving the institution, six months post‐placement, at about 18 months, 32 months, and 4 years.

Dr. Nidhi Singhal, Psychologist and Director of Research at Action for Autism in Delhi, has served as an independent evaluator for each of the data collection periods, with two trained assistants. Respondents included the women themselves, and the staff who know them best.

The Protocol was adapted for the Indian context by Dr. Nidhi Singhal and Dr. James Conroy.

The scales are as follows: Most are only a page long and are simple to complete.

1. Bock Developmental Scale (Independent Behaviour)

2. Challenges (Behavioural challenges)

3. Quality of Life Perceptions

4. Person Centred Planning Processes

5. Integrative Activities Scale

6. Decision Control Inventory

This Report

We are pleased to share the data showing the impact of community life for the original six women after four years in the community. In late 2021, two additional women moved into the Community Lives program, joining the six women already served in two homes. For this report, we share the same outcomes data for these two groups in separate graphs, showing the changes in their lives separately. The graphs below create a picture of growth in every way we have measured since the days of their institutionalization.

1

1. Autonomy and Choice

Honouring the personal autonomy and individual choice‐making of people with disability is enshrined in Indian law and international treaties such as the UNCRPD. One of the crucial tasks across India is to move away from highly controlling segregated models, towards those which afford as much freedom as possible to the people served. Within Community Lives, we have an obligation to assist people to exercise their choices and have as much control over their lives as possible. This scale, the Decision Control Inventory, examines 36 different ratings of the extent to which minor and major life decisions are made by paid staff versus the focus person. The rating scale is as follows:

Legend:

Level 5: Decisions made en rely by focus person

Level 4: Decisions mostly made by focus person

Level 3: Decisions shared equally with staff

Level 2: Decisions mostly made by staff

Level 1: Decisions en rely made by staff

The report for the ini al cohort of 6 women shows a con nuous and steady increase of their overall autonomy in the areas measured. The Community Lives model itself has certain restric ons of choice built in. For example, decisions about what to eat for meals are typically household decisions, with input by the staff. As well, indicators about whether they have chosen the specific house they live in remains sta c, as the op ons was given to move 4 years ago, and there were not mul ple places to move to. A binary choice was offered to move or to remain at the ins tu on. Overall, this data shows a gradual increase in the amount of choice and autonomy the six women exercise over their day‐to‐day lives. For Ms. S and Ms. V, who moved in later, we see similar outcomes in their level of control over their lives. This data shows a similar leap in autonomy in the first 6 months, with a modest increase over the ensuing year.

Page | 2

2

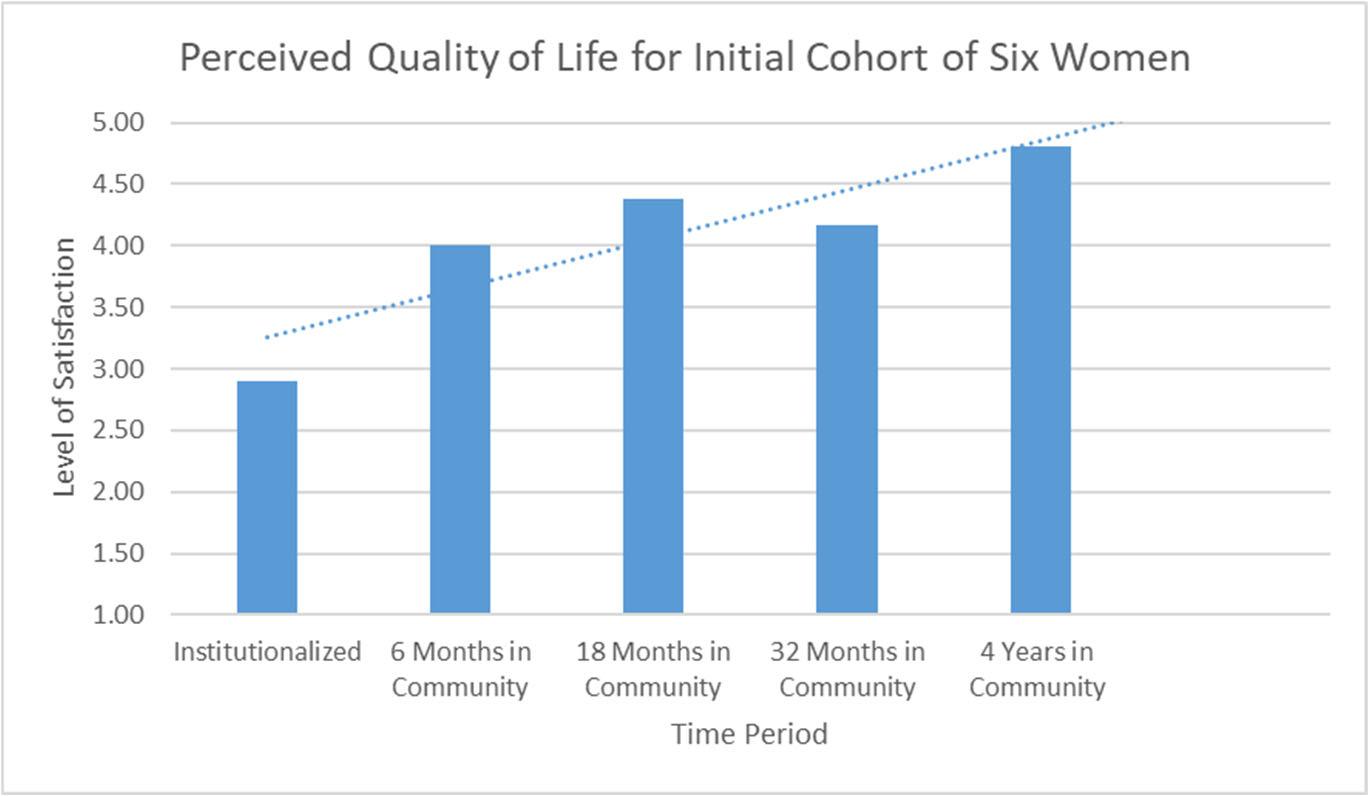

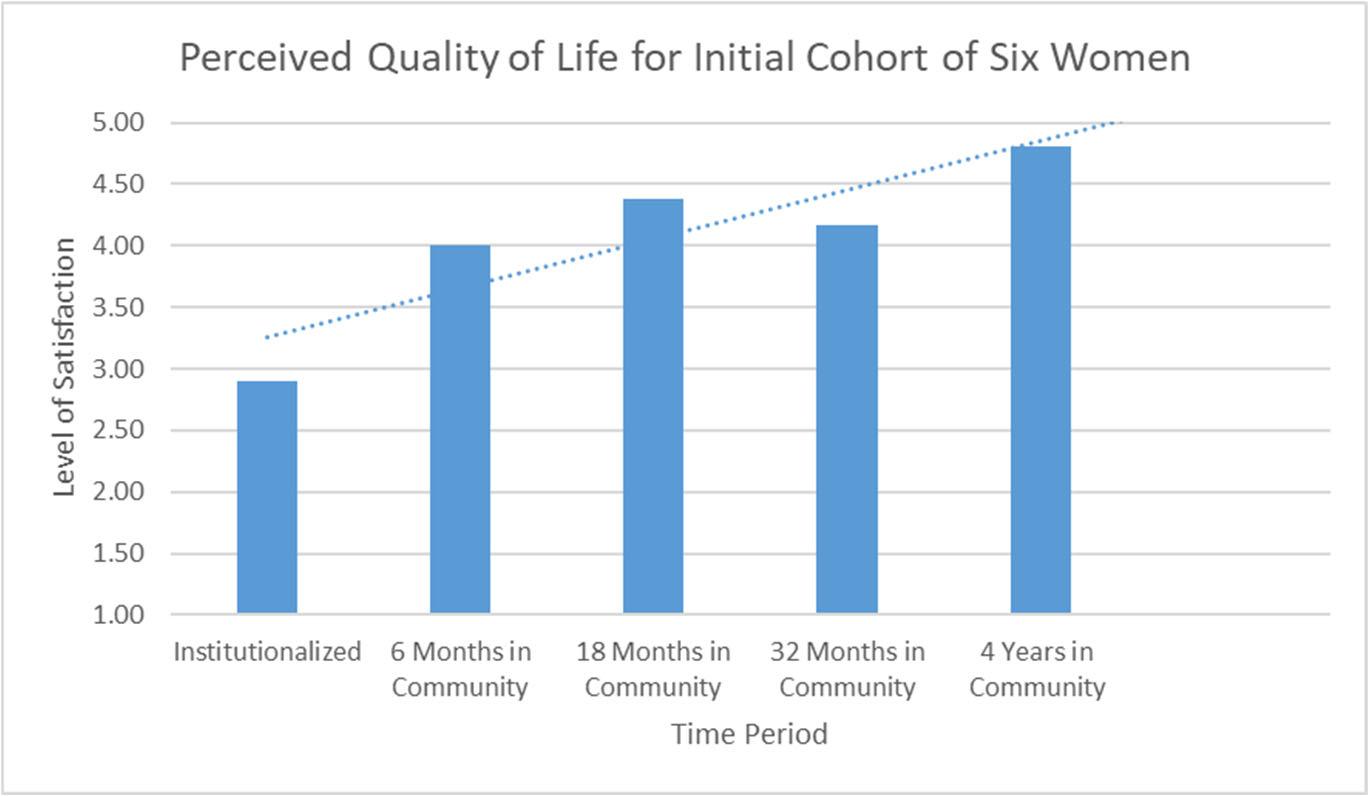

2. Perceived Quality of

Life

This measurement answers the essen al ques on, “Are the women more sa sfied with their lives than they were when they were in the ins tu on?”. The self‐percep on of quality of life is measured using the Quality‐of‐Life Percep ons Scale (Conroy, 2017), which measures 14 areas of life, in which the focus person rates their sa sfac on with each aspect of life on a scale of 1‐5 as follows:

5: Very Good

4: Good

3: In Between

2: Bad

1: Very Bad

The self‐percep on of quality of life has clearly shi ed drama cally, overall, the women see themselves as much be er off For Ms. S. and Ms. V., who le the ins tu on later, a similar trend can be seen.

3. Elements of Person‐Centred Planning

This area measures 15 different aspects of individualised and person‐centred practices. It presents a series of positive statements, with the individual and her allies rating them on a five‐point scale ranging from “not true at all” to “completely true”. This is the one measurement in the series which measures service processes rather than outcomes in people’s lives. This is important to note, as our own performance in using person‐centred methods is at issue.

This data shows a decrease in use of person‐centered elements from prior years. Review of the 15 aspects reveals that the collector at 34 months likely interpreted several specific ques ons differently than Dr. Nidhi Singhal, who personally collected the data at the 4 other me periods. If this is the case, then the data is virtually unchanged between the period of 18

Page | 3

3

months and at 4 years. This has face‐validity, as the planning processes used have not been significantly changed over the course of the four years since the Community Lives program was launched.

These results are echoed in the results of the two women who moved in later. It should be noted that the areas which showed lowered performance are flexibility of mee ng mes, planning process selected by support team, and who has the final word in disagreements. These areas need to be shored up, even if the collector may have had some different interpreta ons of the scale elements.

4. Adap ve Skills (Independence in Daily Living)

This measurement examines level of independence in 80 different areas of everyday adaptive skills. The instrument has adapted for the Indian context from the Bock Developmental Scale by Dr. Nidhi Singhal and Dr. James Conroy. Areas such as cooking, cleaning, self‐care, literacy, money management, and others are scored on a 0‐3 scale as follows:

0= Needs Total Support to Accomplish

1= Needs Major Support to Accomplish

2=Needs Minor Support to Accomplish

3=Needs no Support to Accomplish (Independent)

This data shows the gradually increasing independence of the women in the measured life areas. Over me, this instrument has its limita ons because the 80 items cannot capture all the areas of growth in skills, and we are currently inves ga ng other instruments which may be more comprehensive over

Page | 4

4

me. However, the Bock Developmental Scale has served us well thus far to be able to see the developmental progress and learning. Due to the nature of their disabili es, each of the women will likely con nue to need some, and even significant, assistance and support over the course of their lives. The capacity for growth and change is clear, and we are seeing this growth in innumerable ways.

The changes in independence of the two women who joined the others in 2021 is drama c, and this is echoed by the staff, who have seen tremendous growth and change – both of these women could live more independently in the future if they choose to. This could never have been predicted when we first met them in the Nari Niketan in Dehradun.

5. Challenging Behaviour

This scale examines 20 different areas of “challenging behaviour”, with a severity scale of 1‐4 for each. The severity is calculated by comparing the “most severe” possible behavioral level of all 20 areas with the actual total number scored. Clearly, there were few noted problema c issues named by the ins tu onal staff, and in both situa ons, those very minor issues have decreased. Interes ngly, the rates of challenging behaviour increased when the six people we serve moved from the ins tu on, likely due to the stress of transi on as well as increased freedoms and less power‐based management of behaviour. One can see that the women were seen as having very few problema c behaviors pre‐and post‐ placement, and at four years in the community, most of the women have no severe behavioural challenges. This is echoed in the data for the two women who moved in later, and they have experienced no escala on of behavior at all.

Page | 5

5

6. Integra ve Ac vi es

One of the promises of living in the community is that people with disabili es will have many more opportuni es to live a more integrated life and spend me in non‐segregated places. This scale captures a raw count of how many mes each person par cipated in an ac vity outside the home in non‐segregated places such as banks, market, restaurants, places of workshop, visi ng with friends, or traveling in public transporta on. The data collector looks at the 4 weeks prior to the visit to count the number of mes as in the records, then an average is calculated. This graph below shows the stark difference between the insular life in a custodial care ins tu on and each of the woman as they engage more and more in the community where they live. Friendships, work, and recrea on expansion has bloomed in transforma ve ways. Of course, the pandemic limited travel and community ac vity of the women to some degree, which is one reason for the drama c increase, but in addi on the engagement of all the women we serve in community is clear.

Conclusion

This report demonstrates without a doubt the posi ve impact of a community life, and creates a compelling argument to create exit pathways for all of the persons housed in India’s custodial ins tu ons across the country. It is heartening that a er decades of ins tu onaliza on (well over 50 years, combined) these resilient people are able to move forward in life so well. The transi on to community was not without challenges, mistakes made, and difficult mes in the lives of each of these 8 women and the organiza on that serves them, but the benefits of community life appear clear.

Submi ed by: Elizabeth Neuville and Geeta Mondol

Page | 6

6