Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

Terminology

It is important to understand some key terms used in this plan. “Weather” refers to atmospheric conditions that occur locally over short periods of time from minutes to hours or days. For example, rain, snow, clouds, winds, floods or thunderstorms. This is different from “climate”, which refers to the longterm regional or global average of temperature, humidity and rainfall patterns over seasons, years or decades (May, 2017; NASA, 2020; USGS, n.d).

Global warming and climate change are often used interchangeably, leading to confusion and misconceptions about the implications of climate change. “Global warming” is defined as the long-term warming of the planet, made possible because of the existence of the greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect is a mechanism by which gases in Earth's atmosphere, such as carbon dioxide and water vapour, trap the Sun's heat. This process is not inherently damaging, in fact it is one of the things that makes Earth a habitable planet. However, certain processes can enhance this effect by increasing the concentration of heat trapping gases, known as “greenhouse gases” (GHG), into the atmosphere (fig. 10).

“Climate change” refers to the long-term change in the average weather patterns that define Earth’s local, regional and global climates. Climate change encompasses global warming but refers to the broader range of changes that are happening to the planet (NASA, 2020). Such changes include shifts in flower/plant blooming times, crop loss, population movements, invasive species, flooding, reduced air quality and changes to infectious diseases (Butler and Harley, 2010; NOAA, 2019).

Climate change has occurred naturally throughout history, with seven cycles of glacial advance and retreat taking place within the past 650,000 years (NASA, 2020). Simply put, climate change occurs when the total amount of energy in Earth’s atmosphere changes. Though climate change is a natural occurrence, human activities have caused rapid and unsustainable changes not previously experienced in Earth’s history. Wildlife do not have a chance to adapt to changes that occur over decades versus those occurring over centuries or millennia.

There are many natural and human factors (also called drivers) that influence the climate (fig. 11). Natural climate drivers include changes in the sun’s energy output, changes in Earth’s orbital cycle, and large volcanic eruptions that emit light-reflecting particles into the atmosphere. Human-caused, or anthropogenic climate drivers include GHG emissions, exhaust emissions, and changes in land use.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 17

Deforestation as a result of urbanization is one example of land use change, leading to a lack of vegetation available to absorb carbon dioxide from the environment (NOAA, n.d.; UCSUSA, 2017; EPA, 2017).

Anthropogenic

Solar output

Orbital shifts

Volcanic emissions

GHG emissions

Exhaust emissions

Deforestation

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 18

Figure 10. A schematic diagram of the greenhouse effect (Elder, 2019)

Figure 11. Examples of climate drivers (KEPO).

Natural

Most of the changes to Earth’s climate throughout history have been caused by small variations in Earth’s orbit that change the amount of solar energy our planet receives (NASA, 2020). The climate change we have been experiencing in recent decades, however, is almost entirely the result of human activity and is occurring at a rate that is too fast for organisms to adapt to. Documented global temperatures have been rising since the onset of the Industrial Revolution (1760), characterized by the mass combustion of fossil fuels for energy, resulting in the release of GHG’s into the atmosphere (fig. 12) (NASA, 2020). In 2018, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that human-induced global warming reached approximately 1°C above pre-industrial levels in 2017, increasing at 0.2°C per decade (Allen et al., 2018). A rise in global temperature, even by 1°C, can have major effects across the globe, such as warming oceans, shrinking ice sheets, glacial retreat, decreased snow cover, sea level rise, declining arctic sea ice, extreme weather events, and ocean acidification (NASA, 2020).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 19

Figure 12. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere as a function of time (NASA, 2020).

Background

Guided by a respectful relationship with the natural world and upholding our traditional responsibilities to ensure the cycles of life continue, Kahnawà:ke has a long history of championing community projects centered on health and wellness. Kahnawà:ke has accessed funding to implement these projects which complement and build upon past efforts. This is because as Onkwehón:we, we recognize the interconnectedness of the world around us, in that what benefits the individual elements, benefits the whole. Physical health, mental health, the culture, the language, the economy, the environment; we recognize that all of these have direct impacts on each other. As a community, we strive to move in the same direction in terms of food security, health and wellbeing, traditional responsibilities, and family time.

The Kahnawà:ke Schools Diabetes Prevention Project (KSDPP) is one example of an organization that works towards improving the health of Kahnawà:ke families. Established in 1994, their mission is to design and implement intervention activities for schools, families and the community to prevent type 2 diabetes (KSDPP n.d.). Since their mandate focuses on the health of the community, they have participated in projects involving climate change, the environment and how it impacts our health. Through funds granted from the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program South for First Nations South of 60°N, KSDPP was able to implement the Kahnawà:ke Climate Change & Health Adaptation Program in 20182019. This included hosting a Climate Change & the Environment Community Consultation where they raised awareness about how the community may be affected by climate change and how the community can engage in more mindful stewardship of the environment, and create a more comprehensive plan for how Kahnawà:ke will navigate our new environmental reality (McComber, 2020).

KEPO (est. 1987), has also led many projects within the community that work to create a healthier environment for the community, which by extension, supports healthy people. For example, KEPO has

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 20

“Humankind has not woven the web of life. We are but one thread within it. Whatever we do to the web, we do to ourselves. All things are bound together. All things connect.”

(Chief Seattle)

been hosting an annual tree giveaway for over 20 years, providing community members with indigenous trees to plant on their property, in an effort to naturalize and restore the environment. In the past, a variety of food bearing trees were also offered to community members. In 2013, KEPO implemented the Shoreline Naturalization Project (SNP), which saw 100 trees and shrubs planted at various points along the Kahnawà:ke bike path that meanders along the shoreline starting at the Onake Paddling Club (Norton, 2013a) In 2017, a Shoreline Vulnerability Assessment was conducted to determine how susceptible the natural shoreline areas in the community are to flooding and erosion, and to map the 1:100-year flood line. KEPO also mapped and characterized our wetland habitats, carried out multiple species at risk inventories throughout the years, monitors surface water and groundwater, manages and controls invasive species and their associated impacts, and restores degraded habitats

The most recent project undertaken by KEPO is the Tekakwitha Island and Bay Restoration Project, which seeks to improve the water flow in the bay, create and diversify habitats for wildlife, naturalize the shoreline to improve the landscape for wildlife and community members, and protect and enhance the existing natural wetlands (KEPO, n.d.b). KEPO is also very involved in educating the community on the various projects taking place within the community (see Box 1).

Some other projects that KEPO has undertaken in the past include measures to reduce carbon footprint in the community such as the Kanata Housing project in 2000, an MCK bike share program, waste reduction at MCK events, composting workshops, carpooling contests, and seed exchange programs. These projects play an important role in fulfilling our duties to protect, preserve, and honour all living things. Similarly, climate change cannot be left to future generations to deal with and it is our responsibility to address this issue now to protect our community and ensure the cycles of life continue. It is for this reason that KEPO developed the Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Project, funded through the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program for First Nations South of 60°N.

One major objective of the Climate Change project was to develop the Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan (KCCP) to enhance the resiliency of the community with respect to the impacts of climate change and to protect the health of current and future generations Change in world climate would influence the functioning of many ecosystems and their species and world-wide depletion of various other natural resources (e.g. soil fertility, aquifers, ocean fisheries, and biodiversity in general). Beyond the early recognition that such changes would affect economic activities, infrastructure and managed ecosystems, there is now recognition that global climate change poses risks to human health. (WHO, 2020). In response

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 21

to these risks KEPO has developed the Climate Change project where we were able to organize a community-wide tree planting event and tree giveaway to mobilize Kahnawa’kehró:non in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. We also developed this plan to capture the shared goals of Kahnawa’kehró:non by consulting with organizations, and community members, notably youth and elders.

The KCCP was built on the past work of KEPO and other organisations in the community, which provided a foundation from which to explore the topic of climate change mitigation and adaptation within the community. This plan investigates the impacts of climate change in the community to a greater degree and elaborates on the variety of steps that individuals and organizations in the community can take.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 22

Box 1. Outreach and Environmental Education

Outreach and environmental education are crucial to the work of the Kahnawà:ke Environment Protection Office (KEPO). KEPO offers environmental education lessons, resources and activities at various levels in the community to ensure that all Kahnawa’kehró:non have access to information about our unique environmental challenges and opportunities. Our goal is to raise awareness about environmental issues, including climate change impacts, in order to influence others to create positive change, garner support for KEPO’s projects and inspire the next seven generations to take action.

It is important that from a young age, our youth are provided with hands-on learning about our natural world. We work with the Kahnawà:ke Education Center (KEC) and various youth groups to provide in class lessons, outdoor activities and teacher curriculums to ensure that the environmental education being taught is relevant to the environmental reality in Kahnawà:ke. Our focus at the elementary and secondary level has been to create an awareness of human impact on the environment, the importance of biodiversity and encouraging citizen science initiatives. A major goal of environmental education at this level is to encourage hands-on learning outside of the classroom while encouraging discussion. Exploring and experiencing the environment creates an awareness of the natural world and the changes that have occurred over time.

KEPO has also been encouraging Kahnawa’kehró:non to pursue studies or training in the environmental stream of the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) disciplines. First Nations students are underrepresented in STEM fields, while at the same time traditional indigenous knowledge has been increasingly recognized in the scientific field. Our goal is to engage students in STEM disciplines while still incorporating indigenous knowledge, with the hope that students pursue higher education in these fields and become future leaders in the environmental field.

Education of adults and leadership is also crucial to effect immediate changes and influence decisionmaking. This is especially important for decisions regarding development and land use and to reduce the environmental footprint of organizations and businesses in the community.

KEPO offers environmental knowledge based on community requests or current projects and develops resources to share via social media, local media or community events. Our goal is to constantly be reaching community members at all levels and avenues of communication. It is through this education that our community will be reminded of our collective responsibility to Mother Earth and continue to learn about ways in which to protect and enhance our environment and build resiliency in the face of climate change.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 23

Rationale

Climate action, whether in the form of mitigation or adaptation, is a way Kahnawa’kehró:non can fulfill our responsibilities as outlined in the various guiding principles of the Haudenosaunee people. It is in the teachings of the Ohénton Karihwatéhkwen that we must respect, love, conserve, and protect the people, the fish, the plants, the waters, the medicines, the animals, the trees, and the birds, especially in these challenging times. We are currently in the midst of a global biodiversity crisis, with species going extinct at an alarming rate and millions of others at risk. This is attributed to human activities such as deforestation, hunting, and overfishing in addition to the spread of invasive species and diseases from human trade, as well as pollution and human-caused climate change (Greshko, 2019). Climate action also works in accordance with the seventh-generation principle by promoting more economically and environmentally sustainable practices to ensure the healthy development of our people, the land, and the wildlife for generations to come.

Although there are numerous climate change plans available online and in print, mitigation and adaptation planning is most effective at the community scale. Exposure to climate hazards, vulnerability, adaptive capacity and risk is place-based, and many of the impacts anticipated from climate change will affect the services, infrastructure, and health of the community for which local governments and organizations have the primary responsibility. Therefore, Kahnawà:ke requires its own climate change plan to reflect our unique conditions and society.

For one, Kahnawà:ke is an Indigenous community, therefore we must consider the impacts of climate change on our culture. It is also worth noting that as an indigenous community, we play a critical role in stewarding and safeguarding the world’s lands and waters. The IPCC reported that strengthening the rights of Indigenous peoples regarding land ownership is a necessary component of solving the climate crisis (2018), especially since 80% of the world’s cultural and biological diversity is held within the territories of Indigenous Peoples.

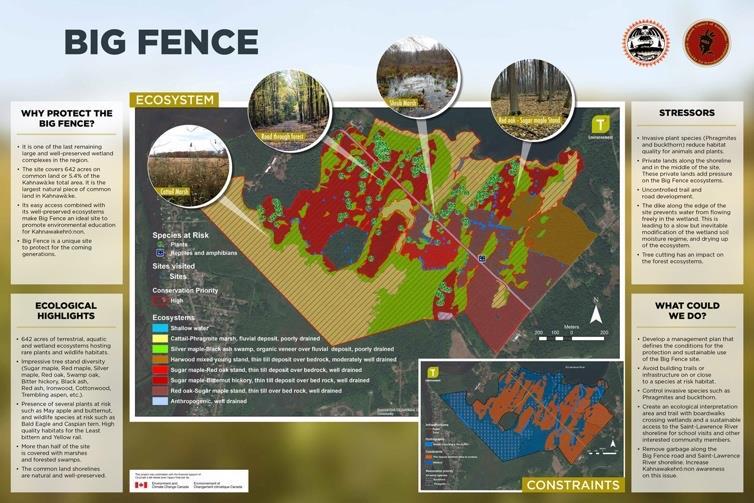

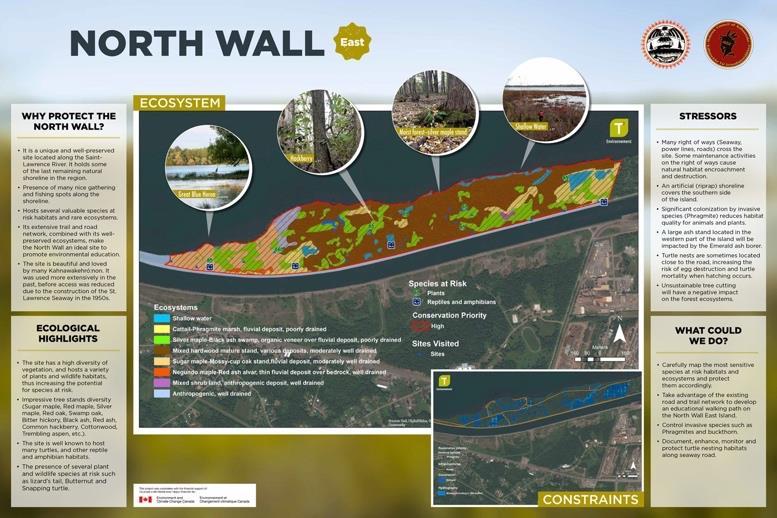

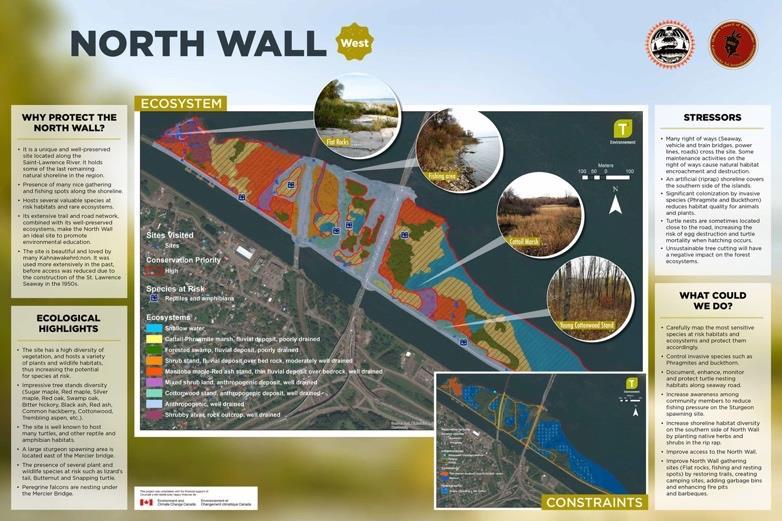

Second, we have a unique physical environment composed of mostly natural landscapes surrounded by urbanized neighboring municipalities. Within the natural lands, there is a high diversity of ecosystems and a wide range of wildlife species. Our community is also located along a major waterway system (the St. Lawrence River) and is crisscrossed with a variety of industrial infrastructure (e.g. the Mercier bridge, the St. Lawrence Seaway, railway corridors, hydro corridors).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 24

Thirdly, the health profile of Kahnawà:ke is also unique. For example, 12% of adults aged 45-64 years old have Type 2 diabetes (twice the rate of the general population of the same age), which makes them especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Lastly, Kahnawà:ke is governed by the elected band council system as well as the traditional Longhouse system, an organizational structure that is significantly different from neighboring, nonIndigenous municipalities. These characteristics, among others, warrant a climate change plan tailored to our conditions.

The KCCP emphasizes adaptation efforts because scientific evidence indicates that regardless of how successful mitigation efforts are, the impacts of climate change will be felt for a long time, possibly for the next century (NRC, 2011). Nevertheless, mitigation efforts at all levels are also covered in this plan since action at all levels is critically important to reduce our collective contributions to this global crisis. Without action, the risks imposed by climate change threaten the health of Kahnawa’kehró:non and our ability to address our goals as a community, such as those related to cultural revitalization, environmental protection, and economic prosperity.

Goals and Benefits

The main objective of the KCCP is to increase the resilience of our community (health, culture, ecosystems, infrastructure, economy, programs, and services) to anticipated local climate change impacts. To do so, there are a variety of goals that KEPO seeks to accomplish. These goals are to:

• Increase awareness of climate change and associated impacts and risks.

• Increase awareness of the relevance of climate change to Kahnawa’kehró:non and the need for action

• Inspire and mobilize the community to reduce our contributions to climate change and act for the benefit of future generations

• Develop and highlight opportunities for cooperation and collaboration between stakeholders through the development of networks and partnerships.

• Document the climate related changes locals have observed within the community.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 25

The benefits of the creation of the KCCP include:

• Building on new opportunities for awareness raising, capacity building, tools, policy, learning, and innovation.

• Reducing projected long-term impacts and costs of responding to climate hazards.

• Building the capacity and experience to support other Indigenous communities to develop and implement their own climate change plans.

Methodology

The planning process for the development of the KCCP was inspired by the process outlined in the Climate Change Adaptation Planning: A Handbook for Small Canadian Communities produced by Natural Resources Canada (2011). Below is a schematic diagram which shows the components of each step (fig. 13). A full timeline of the events can be found in Appendix 3.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 26

Anticipated

changes

Host

Community Engagement

Content analysis Surveys Interviews

Preparation of Recommendations

Getting Started

To start, a communication plan was created which included creating outreach material for social media and local media and organizing information sessions with the public. To raise public awareness for both climate change and the KCCP, promotion was done through various media and informational booths, for example: local K103.7 FM radio station on the Tetewathá:ren Party Line Talk show, the 2019 Christmas

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 27

Figure 13. Sequence of events for developing the KCCP (KEPO).

information sessions Conduct surveys Conduct interviews Research

Started

climate

Potential impacts Vulnerabilities and strengths Identify stakeholders Getting

Create communication plan Build public awareness

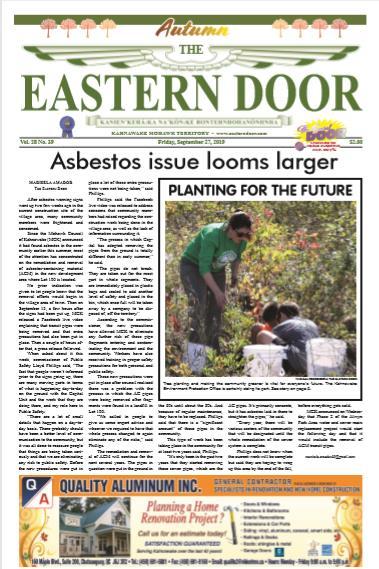

Craft Fair, the 2019 Corn Festival, in the local newspapers (Iorì:wase & The Eastern Door), and though various flyers. Most notably, the project was promoted through the organization of a community-wide tree planting event. The tree planting event served to:

1. Announce the development of the Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan (KCCP).

2. Mobilize the community to participate in climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts

3. Encourage healthy, outdoor family activity, and build a volunteer database for future projects.

4. Share planting techniques with the community.

5. Offset the effects of the Emerald Ash Borer infestation by replacing some of our community’s dead and dying ash trees.

Research

KEPO accessed Indigenous knowledge on the climatic conditions of Kahnawà:ke by conducting interviews with local elders on the changes they have observed in the community within the past few decades, and to obtain guidance on what the community should be doing to combat and adapt to climate change. KEPO determined how the observed effects may be exacerbated in the future by reviewing scientific literature specific to the region, such as the Québec Climate Change Action Plan (2012) and the Climate Change Adaptation Plan for Montréal (2014a). KEPO then explored the implications of those changes to the community. Lastly, a document review of the local Eastern Door newspaper was conducted to find records of climate-related events that had occurred in the community since 2010.

KEPO researched how Kahnawà:ke is vulnerable to the potential effects of climate change using data from the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources (CIER) to outline what major areas of risk are of concern to our community. The strengths of the community in the face of climate change were then identified through an examination of existing data on the environmental conditions of the territory and by analyzing existing services and programs offered within Kahnawà:ke. Additional input was obtained by reviewing the KSDPP Community Consultation Report (McComber, 2020) which contains the strengths of the community identified by Kahnawa’kehró:non in the context of climate change.

A fact sheet and presentation were created to be delivered to community members to raise awareness and obtain feedback, which will help to inform future plans and projects.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 28

Key stakeholders that could provide insight into the development of the KCCP were also identified by reviewing a list of community grassroots groups, organizations, and units within the MCK

Community Engagement

Elders, youth, and other key stakeholders were engaged to ensure that the KCCP reflected the needs and values of Kahnawa’kehró:non. Several information sessions were presented within the community to discuss:

• Climate change

• Expected climate-related changes coming to Kahnawà:ke

• The vulnerabilities of the community to climate change

• The implications of climate change to our culture, health, and environment

• The Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

• Individual climate change mitigation efforts

• Resources for further information

Some of the public information sessions featured a demonstration of the Enhanced Maritime Situational Awareness (EMSA) system. This web-based geographic information system has been used at KEPO for a variety of functions, and the community was shown how it can be used in climate change mitigation and adaptation planning. Some of the applications include mapping high risk flood zones in the community, monitoring weather, recording reforestation efforts, and tracking the spread of invasive species.

Following these presentations, participants were encouraged to discuss and provide input on the KCCP Participants were also asked to fill out a survey (Appendix 5) Elders and other key stakeholders were interviewed individually or in small groups

Content Analysis

All data obtained through community engagement efforts were subjected to a content analysis This consisted of coding the answers to the surveys and transcribed texts from interviews and discussions into categories for qualitative analysis to generate themes that encompassed the views of Kahnawa’kehró:non regarding climate change and its impacts on the community.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 29

Preparation of Recommendations

KEPO researched suggested adaptation actions for local governments and communities, such as the CIER report on Climate Risks and Adaptive Capacity in Aboriginal Communities (2009) and the IPCC report on Adaptation Opportunities, Constraints, and Limits in: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. KEPO also researched what other municipalities and communities are doing to prepare for climate change, such as the Climate Change Adaptation Plan for the Montréal Urban Agglomeration 2015-2020; Adaptation Measures (2014), the Climate Change Adaptation Plan for Akwesasne (2013), and the Blackfeet Nation Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2018).

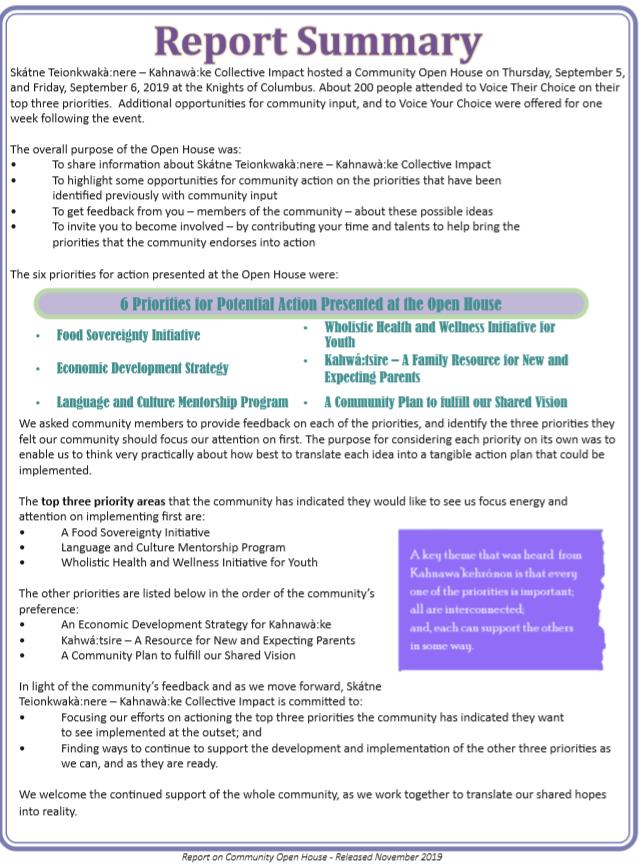

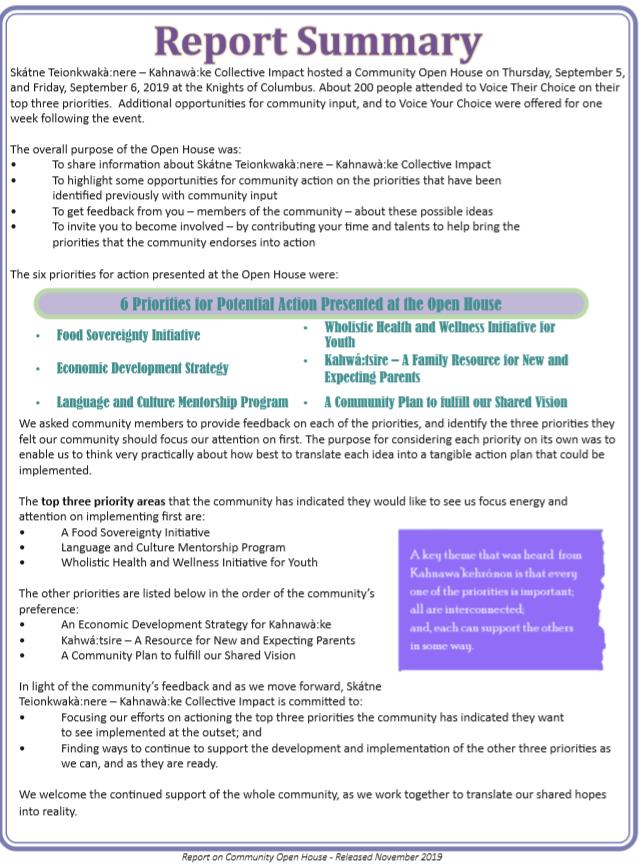

KEPO then reviewed the results of the Content Analysis from community engagement efforts and the KSDPP and KCI reports to guide the determination of priorities for adaptation actions. For example, the KSDPP community consultation indicated that Kahnawa’kehró:non are concerned about emergency preparedness, food security, health, invasive species, and survival skills (McComber, 2020). The KCI open house polled what the community would like to see: a Food Sovereignty Initiative, an Economic Development Strategy, a Language and Culture Mentorship program, a Holistic Health and Wellness Initiative for youth, and a Community Plan to fulfill a shared vision (Appendix 2)

Results Tree Planting Event

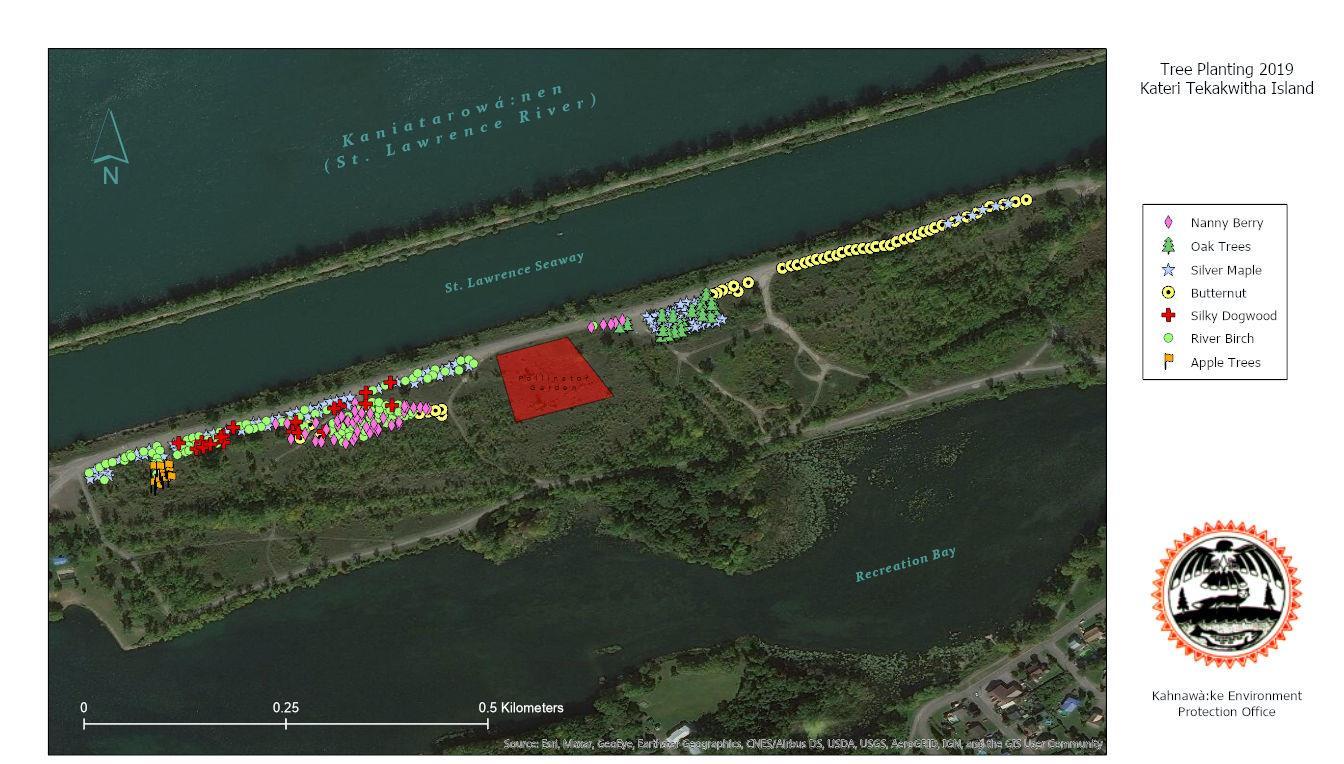

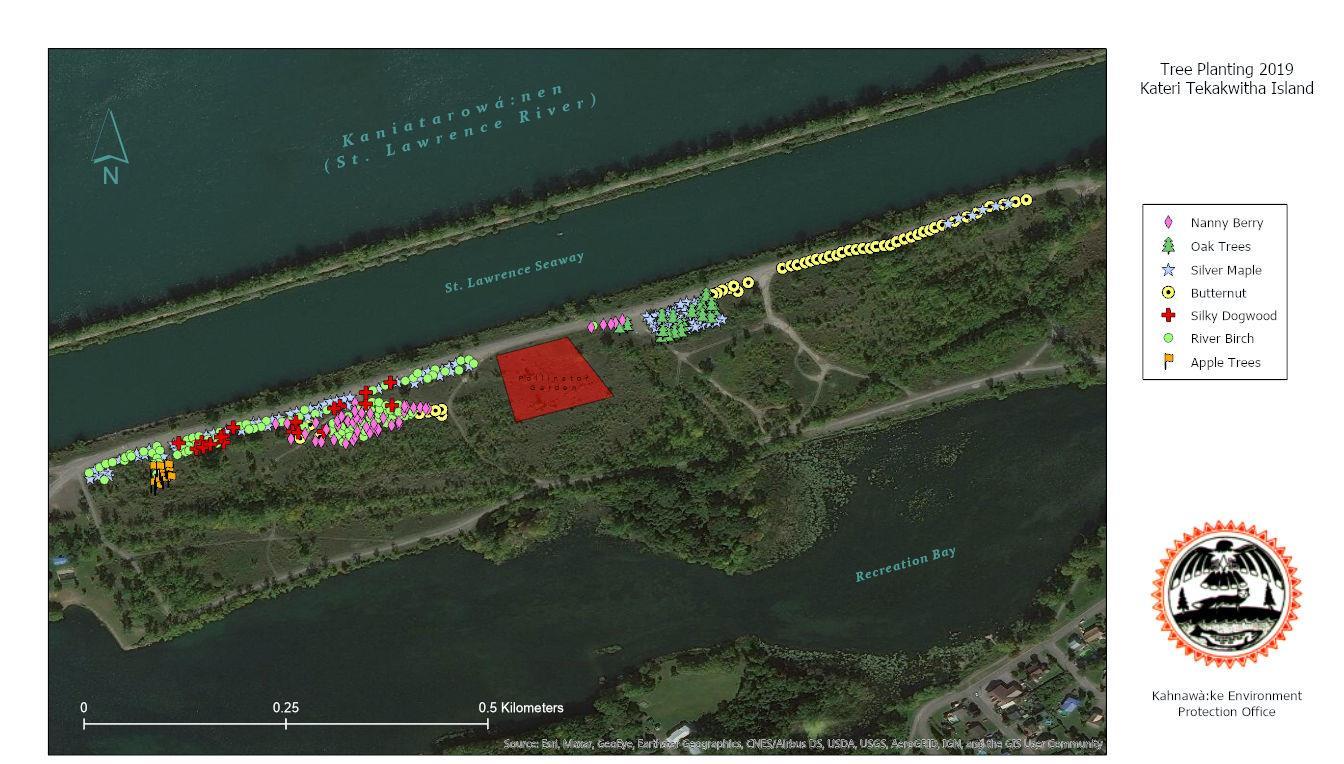

Over 250 volunteers participated in the three-day community tree planting event, which resulted in the planting of 534 trees in the community. Many of the volunteers were students from the local schools, such as Karonhianónhnha, Kateri, Ratiwennahní:rats, and the FNRAEC (See Appendix 4 for media).

Day 1 & 2 of the tree planting event took place at Kateri Tekakwitha Island (fig. 14, 15). This location was chosen because it is large, held in common, easily accessible, and low in biodiversity compared to the other ecosystems of the community. The low biodiversity of the island is a direct result of the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950’s when rocky material was piled on top of several natural islands to form one large island. To mitigate this issue, soil and mulch were added to encourage the trees to take root and survive A total of 175 volunteers planted 358 trees on the island The tree species planted in this region were selected for their tolerance to harsh conditions, such as Red Oak (Quercus rubra), White Oak (Quercus alba), Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum), Silky Dogwood (Cornus amomum), Butternut (Juglans

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 30

cinerea), Nanny Berry (Viburnum lentago), River Birch (Betula nigra), and various species of Apple and Plum trees (Malus spp)

Day 3 of the tree planting event took place at the greenspace near Orville Park (fig. 16, 17). This location was chosen because it is large, held in common, easily accessible, and is not open to development in the future. The park is a frequently used space that offers a variety of community services, such as a splash pad, walking path, lacrosse box and basketball court. In the future, the trees will offer shade during intense heatwaves and provide a place for community members to enjoy nature. The planting of the trees will also help to create a sound barrier to marine traffic on the St. Lawrence Seaway. A total of 75 volunteers planted 176 trees at this location. The tree species planted on this day were Red Oak (Q. rubra), White Oak (Q. alba), Silky Dogwood (C. amomum), Common lilac (Syringa vulgaris), Wild Rose (Rosa acicularis), Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) and Silver Maple (A. saccharinum).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 31

Figure 14. KEPO worker planting trees at Tekakwitha island (KEPO).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

Figure 15. The locations of all the trees that were planted on Tekakwitha Island (KEPO).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 33

Figure 16. The locations of all the trees that were planted near Orville park (KEPO).

Additional trees were planted in the community by Iontonhontsasheronni Delormier & Son Landscape and Design and 350 trees were given to community members to plant in their own yards. A total of 1,000 new trees have been planted in Kahnawà:ke through this project. 100 trees were offered to the Ratihontsanontstats Kanehsatà:ke Environment Office and distributed to community members in our sister community of Kanehsatà:ke.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

Figure 17. Volunteers planting trees at Orville park (KEPO).

Anticipated Climate Hazards

There are six main climate hazards that Kahnawà:ke can expect to occur more frequently in the coming years: higher average temperatures, droughts, heatwaves, destructive storms, heavy rainfall, and river floods. These hazards, as well as their associated projections, are summarized in Table 3.

1. Higher Average Temperatures

Climate projections indicate a rise in temperatures in Quebec by 2050. In southern Quebec, it is expected that there will be a greater warming in the winter (average temperature increase of 2.5 to 3.8°C) than in the summer (average temperature increase of 1.9 to 3.0°C) (CRAAQ, 2012).

For the Montreal region in particular, climate projections indicate that for the 2041-2070 period, the average temperature will increase by approximately 2 to 4 °C (Bush and Lemmen, 2019). For the 2071-2100 period, it will increase by approximately 4 to 7 °C. The duration of the freeze-up period is expected to decline by 4 to 2 weeks compared to that of today. It is estimated that the snow-cover period will be reduced by 65 to 45 days for the 2041-2070 period, compared to the historical period of 19701999. The most extreme projections suggest snow-cover periods of less than 20 days. Finally, the climate projections predict that by 2050, there will be an increase in the number of freeze-thaw cycles in the wintertime, and a decline in freeze-thaw cycles in the fall and spring (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Box 2. Local accounts of changing weather in Kahnawà:ke.

“As a young child I remember the huge snow drifts along the road where the Golden Age Club is now. The road was cleared by a large snow blower and the sheer wall of snow would be 8 feet high in some places. I also recall being able to climb onto the roof at my house via a snow pile that fell from the roof. Snow was much more abundant 30 years ago, it seemed to snow almost every week during the winter months. Of course, the melting abundance of snow helped to replenish waterways and creeks around the community”. Dorris Montour (Norton, 2013b).

2. Heat Waves

Climate models predict significant increases in the duration of heat waves and an increase in the frequency of hot nights (minimum temperature greater than 20 °C). According to the same projections, the maximum extreme temperatures in the summer will increase more than the summers’ average

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

temperatures. This suggests longer and more intense heat waves in the next few decades (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Table 1. Landmark events: Extreme heat waves in Kahnawà:ke.

June 20 - 24th, 2012

July 17-18th, 2013

June 27 - July 1st, 2014

June 18 - 20th, 2016

July 21st - July 22nd, 2016

June 11th - 12th , 2017

June 29th - July 2nd, 2018

August 5 - 6th, 2018

July 2-5th , 2019

*Weather information obtained from climate.weather.gc.ca/ (using the La Prairie weather station) and www.timeanddate.com/weather/canada/Montréal/historic

3. Drought

Most climate projections agree that by 2081-2100, there will be shorter periods of droughts (on an annual basis) in the winter (December to February), but longer periods during the summer (June to August). By 2081-2100, the projections indicate annual drier conditions for soil, which will be even more pronounced in the summer months (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

4. Destructive Storms

Changes in the intensity, frequency and magnitude of some weather events can be expected to be felt throughout Quebec (CRAAQ, 2012).The climate projections concerning destructive storms (freezing rain, heavy rainfalls, hail and strong winds), in the Montreal region specifically present some uncertainties (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). However, the trends that have already been observed and the considerable impacts that are associated with these storms, require consideration for adapted measures for Kahnawà:ke to better prepare itself to face these events in the future.

There has been an increase in the severity of storms in recent years (Table 2). In August of 2017, the public safety unit of MCK even had to put out a tornado warning, which has never happened in this

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 36

Time period Maximum temperature (°C)

35.0

34.0

33.0

35.0

33.0

34.3

37.2

33.1

34.3

region before (Lazare, 2020). Eleven tornadoes touched down in Québec on June 18, 2017, which is the most ever recorded in the province (fig. 18) (CBC, 2018a).

37

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

Figure 18. The tornado that hit the Saguenay region on Lac Kénogami on June 18th, 2017 (CBC, 2018a).

Date Type of storm Details Figure Source January 1998 Freezing rain 100 mm N/A CBC, 2013 December 16-17th, 2007 Snow 30 – 40 cm N/A CBC, 2013 February 13th, 2007 Snow 15 - 20 cm N/A ECCC, 2017 September 8th, 2012 Wind N/A 34 Norton, 2012 December 26th - 27th , 2012 Snow 30.0 cm N/A climate.weather.gc.ca/ January 5 - 6th, 2014 Freezing rain N/A N/A Vendeville, 2014 January 5th, 2015 Freezing rain N/A N/A Deer, 2015 July 14th, 2016 Thunderstorm, wind N/A 35 Rowe, 2016b March 14th, 2017 Snow 63.0 cm N/A climate.weather.gc.ca/ November 1st,2019 Wind 90km/h 36 Fedosieieva, 2019

Table 2. Landmark events: Destructive storms in Kahnawà:ke.

5. Heavy Rainfall

An increase in precipitation is also expected throughout Quebec (CRAAQ, 2012). It is estimated that by 2050, annual precipitation events (rain, snow, sleet, or hail) in the Montreal region are expected to increase by 3% to 14%, especially for rainfalls in the winter (+2% to +27%) and in the spring (+3% to +18%). A significant increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy rain episodes is also expected. By 2100, the intensity of heavy rain episodes could increase by 10% to 25% (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

6. River Floods

Kahnawà:ke lies within the St. Lawrence drainage basin or watershed (fig. 19), which is fed by the Great Lakes watershed. As the global temperature warms, the freshwater levels of the Great Lakes and the subsequent St. Lawrence River are expected to rise during spring melts following intense precipitation events, which could put our community at risk of flooding events like the one that occurred in 2017 (Perreaux, 2018) (Box 3). The shorter winter season caused by the heat will also result in an earlier spring thaw, which creates spring floods earlier in the year (Montréal, 2014a).

However, climatic modeling for this impact is uncertain in that the effect of higher average temperatures would mean less ice formation on the Great Lakes, which could lead to more evaporation and ultimately lower levels in the lakes, and by extension, the St.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 38

Lawrence river (Ouranos, 2019).

Figure 19. St. Lawrence River drainage basin (Government of Canada, 2017).

Box 3. Landmark event flooding in southern Québec.

In the spring of 2017, constant rainfall, rapid snow melt and high-water levels on the other Great Lakes flooded hundreds of private properties and public infrastructure around Lake Ontario. When combined with the very high flows from the Ottawa River, extensive flooding also occurred in Québec, where 5,371 homes were damaged or destroyed (Perreaux, 2018) (fig. 20).

Climate Hazards

Higher average temperatures

Heat waves

Drought

Destructive storms

Heavy rainfall

Projections

• Extension of the summer season.

• Shortening of winter season.

• Increased frequency of freeze-thaw episodes.

• Increased frequency and intensity.

• Increased frequency of hot nights.

• Increased duration during the summer season.

• Increased frequency of heavy snowfall and winter rainfall episodes

• Increased frequency of freezing rain events.

• Increased frequency of hail events.

• Increased frequency of strong winds.

• Increased frequency and intensity of heavy rain fall events.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 39

Figure 20. A flooded home in Saint-Andre-d’Argenteuil, 95 kilometres North-west of Kahnawà:ke on May 9th, 2017 (Perreaux, 2018).

Table 3. Top 6 anticipated climate hazards to Kahnawà:ke.

River floods

• Increased occurrence of spring floods earlier in the year.

• Reduced ice formation and lower water levels.

• Increased severity of spring floods.

* This table is based both on meteorological and hydrological observations in Montréal, and on projections for Southern Québec. The only exception is “Destructive storms” which only presents an analysis of meteorological observations in Montréal.

Potential Impacts

With the above-mentioned climate hazards come a cascade of effects that can impact a variety of sectors in the community, which are summarized in tables 4-9

1. Higher Average Temperatures

An increase in the number of freeze-thaw cycles in the winter can lead to the accelerated deterioration of infrastructure (such as the Mercier bridge, the tunnel as you enter the Eastern entrance of the community, and our roads) and can also lead to a greater presence of potholes (fig. 21) (FPE, 2015). This can lead to more car accidents and damaged vehicles in the form of cracked or bent rims and flat tires.

More damage to our roads necessitates more roadwork, which can impact the revenue of businesses in the community, such as in the summer of 2013. Major construction work along River road, a main road in the community, had significant economic impacts on local businesses. One business owner estimated losing up to 75% of their customers (Rowe, 2013). More road work also means increased cost to the community to maintain roads.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 40

Figure 21. Pothole in Kahnawà:ke (Ieteronni Beauvais, 2013).

Another potential side effect of more freeze-thaw events is the increased risk of the freezing and bursting of water pipes, which can put strain on community infrastructure.

Winter thaws in particular are a concern for farmers and planters. When it rains, a layer of ice forms on top of snow, which can smother plants and crops that are underneath (Shiab, 2019)

Box 4. Landmark event Freezing rain and quick thaw events in Kahnawà:ke.

In January of 2014, this combination of freezing rain and a quick thaw event caused a variety of issues for the community. The ice caused nine traffic accidents on the Mercier bridge due to the freezing rain. The warm temperatures following the freezing rain resulted in a rapid thaw which clogged drains across town. Many parts of town were flooded because of the stress exerted on the storm drains, such as a portion of the Old Malone Highway across from Village Variety, Dustin’s Coffee & Donuts, the United Church, the courthouse, the bridge by Eileen’s bakery, and part of the old Chateauguay road (Rowe, 2014).

Higher average temperatures can also have drastic effects on the distribution of plants. This has major implications, such as encouraging the appearance of undesirable plant species like Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and invasive plant species such as Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum). More information on invasive plant species in Kahnawà:ke can be found in box 5.

Pathogens (fungi, bacteria, viruses and nematodes) prone to causing infections in plants are also impacted by an increase in temperatures. The increase in average winter temperatures could allow for the survival of a greater number of pathogen agents and, as a result, an expansion of their distribution area (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). This means that pathogen species that cannot survive in the present conditions could eventually attack plants in the territory.

In addition, the disruption of plant lifecycles could have a major impact on agriculture in the community (EPA, 2016). Higher temperatures can lead to changes in plant hardiness zones. A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined to encompass a certain range of climatic conditions relevant to plant growth and survival. When a region changes hardiness zones, different plant species can grow there, and native plant species can get pushed out. In our area, the hardiness zone has changed from 5B to 6a since the 1960’s (NRC, 2017).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 41

Insects are also impacted by changes in temperature, both directly and indirectly. For one, the metabolisms of insects depend entirely on climate conditions. A warming of the environment can lead to an increase in the growth rate of some pest insects, like mosquitoes (Culicidae) and blackflies (Simuliidae) and multiply the number of generations in a season. This could result in an increased frequency of infestations and severity of the damages caused to plants by pests, such as aphids (Aphidoidea) and the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) (fig. 24) The geographic distribution area of insects can also be expected to change. (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

An Increase in average temperatures also means Increased opportunity for invasive species (City of Wind). More information on invasive insect species in Kahnawà:ke can be found in box 5. Hotter summer months, increased frequency of droughts, and insect attacks are some of the many challenges that the trees are facing as a result of climate change. Most insects have a population cycle of growth and decline of about 10 years, which the trees are well adapted to. As the winters are becoming shorter and hotter, more insects are able to overwinter when they would normally die off from the deep freezes that are no longer occurring. Some insect population cycles have been reduced to just 3 or 4 years, and the trees may have a hard time coping with the added stress (Bascom, 2016). Shorter winters and a quicker transition between seasons have resulted in a decline in the quality and quantity of sap produced by maple trees, which puts this business activity at risk (Bascom, 2016). Our relationship with the maple trees goes beyond just the economy. Wahta Ohses (maple syrup) is one of the most important gifts given to us by the Creator. Without it, many of our people would have suffered starvation

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 42

Figure 22. The Japanese beetle is an invasive insect from Asia that feeds on a variety of plants, such as, corn, asparagus, blueberries, and raspberries (Hodgins, 2019).

and sickness during the last few weeks of winter before the snow was no longer so deep, which rendered hunting prohibitive. To this day, it is one of the ceremonies we conduct each year, to give thanks to the leader of the trees and ensure that we are taking care of them so that they can take care of us when we are in need

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 43

Box 5. Invasive species in Kahnawà:ke.

Several invasive plant, animal, and insect species have been identified in the community by KEPO. Some of these species, if not already causing harm, have the potential to pose serious threats to our community.

These threats are varied and affect different aspects of our environment, culture and economy. These species often have characteristics that make their spread into our region particularly damaging. They are adaptable, propagate rapidly, and can outcompete native species. Climate change has a direct impact on species habitats due to changing ecological conditions. As the global climate warms, many species are moving into areas where they had not previously been. Furthermore, some of the main drivers of climate change such as trans-oceanic shipping vessels, which produce thousands of tons of greenhouse gases each year, also contribute to the spread of species between continents, as in the case of the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) (fig. 23) amongst others.

Figure 23. The emerald ash borer beetle (Ali, 2018).

The EAB was introduced to North America in the early 2000s in Windsor, Ontario by a shipping container from China that had timber material containing the insect. Since then, it has proliferated across the country devastating ash stands that it has encountered as its lifecycle causes significant damage to infected ash trees.

Immature EABs feed on ash tree leaves, forming slits in the leaves. Once sexually mature, the adults lay their eggs on the bark of the tree. Their larvae bore through the bark, feeding on the inner bark and sapwood, eventually forming flat, S-shaped galleries that eventually girdle and kill the tree (fig. 24). The larva can grow from 2 to 5 cm long and the width of the S-shaped gallery increases throughout its life span (Government of Canada, 2019). The ash trees here have no known natural defenses to this insect and the predators that feed

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 44

on the EAB larvae (woodpeckers) contribute to the damage to the dying ash. There exists an estimated 100,000 ash trees in Kahnawà:ke, which could be gone in 10-15 years because of this insect.

While the loss of the White Ash trees will be a significant blow to the national lumber industries, it is the loss of the Black Ash that Kahnawà:ke will feel much more deeply as the bark of Black ash is a traditional wood we use for our baskets, ax handles, bow and arrows, sleds and other traditional woodworks (fig. 26)

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 45

Figure 24. Damage of EAB on an ash tree (Pegler, 2018).

Figure 25. Baskets made by a local in Kahnawà:ke (Bonspiel, 2018).

It is thought that the spread of EAB is unstoppable at this point and that it is a matter of decades before all the ash trees are gone. Many efforts have already begun to preserve not only the basket making techniques but also the trees themselves. Treatment of black-ash trees, seed collection and long-term storage is a priority for KEPO so that when the threat of EAB no longer exists, we can replant the trees and restore our basketmaking tradition. Elders and knowledge keepers have been teaching the younger generations the proper ways to make baskets with what little material remains. Partnerships are being developed between communities so that their Black Ash trees can be used by basket-makers as a future store of material.

Other invasive species have been brought by trans-oceanic shipping, which has had a direct impact on Kahnawà:ke via the St. Lawrence seaway. Not only has the imposition of the St. Lawrence Seaway fragmented our community beyond repair, but it has also altered the aquatic ecosystem in ways we are only now beginning to understand. Human interventions on the landscape for convenience and industry have linked our community to the Great Lakes and beyond. This has potentially threatened us with another invasive, a group of fish known as Asian Carp. Four species of carp were brought over from Asia in the late 20th century often for aquaculture and over time escaped or were released from captivity in the south and Midwestern United States. All 4 species, (Black, Silver, Bighead and Grass Carp) have been extremely detrimental to the waters they now inhabit. They are filter feeders, devouring any source of nutrition from the bottoms of rivers, ponds and lakes including the eggs of other fish species. They can quickly out-produce and out-compete native species.

Major efforts, such as the creation of permanent barriers, have been made to prevent the carps from infiltrating the Great Lakes and eventually the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers but more work is needed (ACRCC, 2013). To date, there have been no Asian carp species reported in Kahnawà:ke but due to their destructive potential the community must remain vigilant and ready to respond if and when that day occurs.

Secondly, the advancement in the life history events for many plant species (i.e. the timing of seed emergence) can disrupt synchrony between the interacting pairs. For many insect herbivores, synchronization to plant phenology is crucial for their survival (Cornelissen, 2011). Insects play a vital role in the ecosystem by providing food to animals, such as amphibians and birds. Disruptions to insect populations due to elevated temperatures can thus have a myriad of consequences throughout the food web.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 46

A rise in temperature and humidity can also lead to the extension of the pollen production season (WHO, 2018). This is particularly concerning for allergenic plant species such as Maple trees (Acer spp.) and Common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) (fig.26). In Montréal, the pollen emission period of the latter has increased by three weeks between 1994 and 2002 (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). In certain plants like ragweed, higher temperatures make the plant produce more pollen (AAFA, 2018). Pollen is an allergen that causes seasonal rhinitis (hay fever). This allergic reaction can lead to several complications, such as chronic sinusitis, symptoms of allergic asthma (such as coughing), difficulty breathing, and wheezing (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015).

Rising temperatures can foster the displacement of populations of animals, insects and ticks that carry diseases that are transmissible to humans. In Québec, such displacement increases the number of cases of rabies, West Nile virus (WNV), and Lyme disease (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015; City of Windor, 2012).

Lyme disease and the Nile fever, caused by WNV, have increased in Québec in recent years. There have been 96 cases of Lyme disease in Québec between 2004 and 2011; 15 of those were acquired in the province, and 10 of those occurred in the Montérégie area, which surrounds Kahnawà:ke. In May of 2012, several Lyme disease cases were confirmed in dogs in Kahnawà:ke (McGregor, 2012) and in July of the same year, a local man was hospitalized after contracting Lyme disease in the community (Leborgne, 2012). Since 2011, there has been a significant increase in the number of Lyme disease cases reported to the public health authorities in Québec: 125 cases in 2014, 160 cases in 2015, 177 cases in 2016, 329 cases in 2017, and 304 cases in 2018. In addition, the proportion of cases that acquired their infection in

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 47

Figure 26 Common ragweed (Peacock, 2017).

the province has increased from around 50% in 2013 to over 70% since 2015 (Gouvernement du Québec, 2019).

Rising temperatures are currently leading to the northward migration of vector-borne pathogen animal populations (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). For animals, this will lead to the increased spread of diseases, such as Brain worm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) and Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD). CWD is a progressive, fatal nervous system disease known to infect animals within the Cervidae family (whitetailed deer, mule deer, moose, red deer, elk and reindeer). However, there are growing concerns about the potential transmission to humans from eating infected meat (CFIA, 2019), which has significant cultural implications for many Kahnawa’kehró:non who rely on deer meat for food and other cultural purposes (ie. water drums, clothing, medicine pouches). The warming temperatures can also lead to growing populations of deer, which can significantly damage ecosystems in addition to increasing the spread of CWD through northward migration to northern populations of Cervids. Large populations of deer tend to over browse new trees and destroy habitat crucial to other native plants and wildlife. Studies show that over browsed forests tend to be filled with invasive plants of little value to wildlife. Other threats of too many deer include more crop damage, more deer-vehicle collisions, and more vectorborne and zoonotic diseases that pose a threat to human health (Hewitt, 2011). There is also a possibility that these changes in temperature can increase the frequency of social conflict (Mooney, 2014).

The increase in average temperature in the winter can also reduce the ability of the community to maintain outdoor ice rinks for recreational use (City of Windsor, 2012). Kahnawà:ke has six outdoor rinks. “We’ve been struggling the last few years because it hasn't been that cold,” said Vincent Montour of the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke’s town garage (Byrnes, 2013).

Reductions in snow cover can also have major impacts to the community. Snow acts like a mirror, capable of reflecting up to 90% of incoming sunlight back into outer space. As the earth warms, less snow cover is being produced, which means more heat is being retained by the ground, resulting in snow melting faster in the spring (Shiab, 2019). This can result in low water levels in the summertime, such of that in 2012 (fig. 27). Low water levels in the community affects our environment, especially groundwater reserves and our wetlands which rely on snow to replenish its waters, and our access to clean drinking water.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 48

“When there’s a change in the amount of snow, that triggers a whole chain of events.” Ross Brown, Environment Canada scientist (Shiab, 2019).

The increase in evaporation caused by higher temperatures is expected to lead to an overall decrease in the Great Lakes and St-Lawrence System water levels. Increased evaporation is expected to occur in all seasons, particularly in the winter as a result of decreased ice cover. Canadian modelling predicts a significant lowering of lake levels by 2050 (City of Windsor, 2012).

The increase in average summer temperatures has some positive impacts, such as a lengthening of the crop growing season, an increase in the number of days offering good conditions for outdoor work, and an extension of the golf and bicycle season (FPE, 2015). However, by spending more time outdoors, people will be increasingly exposed to the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) rays. In addition, the diminishing of the ozone layer due to greenhouse gases makes the sun’s rays more potent, which can lead to sunburns, damage to eyes (such as cataracts), weakening of the immune system, and skin cancer (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015; SRMT, 2013).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 49

Figure 27. Low water table in the summer of 2012 in Kahnawà:ke (Deer,2012).

2. Heat Waves

Periods of extreme heat can induce thermal stress in people, causing dehydration, fainting and heat stroke (Gouvernement du Québec, 2019a). Extreme side effects can even include hospitalization, especially of those already vulnerable such as those suffering from certain diseases, pregnant woman, the elderly, and infants (WHO, 2018). There are over 4,000 heat-related deaths per year with 80% occurring in the elderly. The last few years in the Montérégie region, there have been more reported deaths in elderly populations due to heat exhaustion. It is also the second leading cause of death among young athletes. Those under four years old are also at increased risk (Tardif, 2011). Domesticated animals, such as cats and dogs, are also at-risk during times of high heat.

Heat waves can also produce and worsen the impacts of atmospheric pollution, resulting in poor air quality. This can aggravate symptoms of many respiratory problems and restrict the practice of outdoor activities and sports (City of Windsor, 2012).

Vegetation is also vulnerable to heat waves. Although some plants can rely on defense mechanisms to protect themselves, a heat wave can still cause issues such as leaf scorch, stem dieback, and susceptibility to pests and pathogens (fig.28). The vegetation that is impacted then requires additional care or must be replaced, increasing costs required for their upkeep and maintenance (City of Windsor, 2012).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 50

Figure 28 Leaf scorch from a heat wave (Waterworth, 2019)

Heat waves, even for a short duration, can decrease the populations of many insects. This can be beneficial regarding harmful species, but the opposite will be true for beneficial species, such as pollinators (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). This can have serious consequences for the 75% and 95% of all flowering plants whose fertilization relies on the work of pollinators (Ollerton, Winfree, and Tarrant, 2011).

The aquatic environments of Kahnawà:ke may also suffer from heat waves due to eutrophication. Eutrophication is a process that occurs in freshwater and marine ecosystems, characterized by excessive plant and algal growth due to the increased availability of one or more growth factors needed for photosynthesis, such as sunlight, carbon dioxide, and nutrients (Chislock, 2013). This process can lead to a cascade of negative effects, such as reduced water clarity, accumulations of scum on the water surface (fig. 29), unpleasant odors, and interferences with the safe use of waters for recreational activities (Government of New Brunswick, n.d.). When the plants and algae die, they sink to the bottom of the body of water where their decomposition takes up the dissolved oxygen from the water to the detriment of fish and other aquatic wildlife. These algal blooms can even produce toxins that are dangerous for humans and other animals to touch or drink (WFC, 2019). For humans, the ingestion of blue-green algae can result in symptoms such as stomach aches, diarrhea, and vomiting (Gouvernement du Québec, 2019c). For small fish and shellfish, these toxins can move up the food chain and can impact larger animals like turtles and birds. Even if some algal blooms are not toxic, they can negatively impact aquatic life by blocking out sunlight and clogging fish gills (EPA, 2019).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 51

Figure 29. Algal bloom in the summer of 2012 in the Lachine Canal (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Overall, higher average temperatures can have major effects on our natural environment, reducing animal habitats and the many ecosystem services provided by the land.

Extreme temperatures can also weaken infrastructure by impacting roadway networks. Roadways that are frequently travelled and used by heavy vehicles may deform themselves and produce ruts (fig. 30). Extreme temperatures can also cause damage to the expansion joints of structures, which is a concern for the Mercier Bridge (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Finally, heat waves can impact local operations and services. They can give rise to an increased demand for certain services (such as the Onake Paddling Club) or an extension of the ‘business’ hours of air-conditioned public buildings, such as the library and community centres, which can strain electricity services and the associated costs for these non-profit organizations (FPE, 2015). These demands will result in an increased need for workers to provide services to the population, maintain the infrastructure and deploy emergency measures, when required (City of Windsor, 2012).

3. Drought

The impacts of droughts on the territory of Kahnawà:ke are especially concerning during the summer months as this can have serious consequences to our natural ecosystems and to those in the community who farm and garden (NOAA, 2019).

Heat waves can have major effects on the bird communities of Kahnawà:ke. Spring heat waves endanger young birds in the nest, such as the Bald eagle, Peregrine falcon, and Least bittern. These

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 52

Figure 30. Rutting in asphalt pavement (Dylla and Hyman, 2018).

species are already at risk in the community, and the increased mortality rate caused by heat waves may contribute to their local extinction.

Dry soils can result in osmotic stress for plants, reducing their vitality and making them more susceptible to pests and pathogens. By impacting the vegetation, droughts reduce the many ecological services that they provide, such as the provision of food and shade (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). Periods of drought can also contribute to the increased frequency of wildfires (FPE, 2015), which is already an issue in the community (Box 6).

Brush fires often occur in the spring and summer in Kahnawà:ke. Often caused by arson, controlled burns, or abandoned bonfires, the rise in temperature coupled with increased periods of drought and high winds can exacerbate this issue. In 2009, a grassfire burned through a large swath of swamp area behind Goodleaf’s Auto, a local scrapyard, which caused nearly $1 million in damages to machinery at the business. On April 28th , 2013, another grassfire hit the same area (fig. 31). These fires are especially concerning due to the presence of factories, industries, and gas stations in many of these fire hazard areas, and because of all the overgrown dry brush, which burns quickly (Norton, 2013c).

In May, 2013, a ban on open fires was issued to residents of both Kahnawà:ke and the Tioweró:ton territory in response to an extremely high risk of wildfires all over Québec. Locals have noticed that these periods of high risk for wildfires have been getting longer and are starting earlier (Laframbroise, 2013)

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 53

Box 6. Landmark events – Bushfires in Kahnawà:ke.

Figure 31. Bushfire in Kahnawà:ke (Norton, 2013c)

During the end of April and beginning of 2016, five fire reports occurred within three weeks in Kahnawà:ke (Rowe, 2016a). More recently, in May 2019, a string of bush fires occurred in the community, with one burning dangerously close to the local high school, the Kahnawà:ke Survival School (KSS) (Deer, 2019).

The invasive Common Reed (Phragmites australis), is one plant that contributes to the spread of these fires (fig. 32). The plant, identified by its large, dense seed head and long, thin stem, can become very dry and brittle, due in part to the hollow stem. “The combination of this thin, paper-like tube with a hollow core, provides a nearly perfect environment for a fire, which can lead to the fastburning, feathery seed head at the top.” said local tree expert Chuck Barnett (Deer, 2019a). These plants have displaced the native cattails (Typha) and are seen all over the community, putting the community at risk.

Periods of droughts, accompanied by extreme heat, can affect the level of atmospheric pollutants. Under dry conditions, dust and particles (such as pollen) are more easily airborne and contribute to poorer air quality, especially in the event of a wildfire. This greater presence of airborne particles can then exacerbate the symptoms of respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses in humans (Lee et al. 2014).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 54

Figure 32. Common reed (ISAP, 2012).

In times of drought some basic food items can be hard to find. Given the increased cost of groceries, it can be difficult for some people to buy the nutritious foods needed to maintain good health. Severe droughts are also a significant source of stress for agricultural workers (fig. 33) (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015).

The increased demand for water, because of drought, could also result in too much demand on the water treatment facilities. This increased demand could impair the system in the event of a problem and cause an increase in production costs (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). However, the Kahnawà:ke water treatment facility intake pipe is located in the St. Lawrence River, which is an ideal location in case of drought (Morris, 2020).

4. Destructive Storms

Strong winds, the accumulation of freezing rain, hail and heavy snowfalls can all result in damage to our infrastructure and the environment. The severity of the damages depends on the force of the storms, measured in wind speed, the thickness of the accumulation of freezing rain or snow, and the size of the hailstones, among others. Destructive storms can result in fallen trees and branches, causing traffic, damage to infrastructure, and power outages.

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 55

Figure 33. A heat wave in June and July of 2018 caused some strawberries to ripen too quickly at Quinn farm in Île-Perrot (Navneet Pall/CBC, 2018b).

Strong wind bursts can tear up or raise certain elements of homes, compromising the integrity of buildings. Heavy snowfalls and freezing rain can overload roof structures and cause damage. These damages to homes can result in costs related to material damages and increases in insurance premiums (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). Disaster victims may also suffer from psychological trauma and the workers and volunteers may suffer from intense stress (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015). In Kahnawá:ke, the community often rallies together to organize fundraisers to support families affected by damages to their homes, whether caused by a storm or a fire, however increased needs for such supports could cause additional stress in the community

In addition, the damage done to trees caused by high winds and freezing rain can make them more vulnerable to insects and illnesses (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Box 7. Landmark events – Destructive storms in Kahnawà:ke

• On September 8th, 2012, a 100-year-old elm tree fell on a house due to a severe windstorm. The tree was one of the few elms left in town that was not killed by an outbreak of Dutch elm disease that occurred several years ago (fig. 34) (Norton, 2012).

• On July 14th, 2016, a weeping willow tree was knocked over during a thunderstorm that involved heavy winds (fig. 35) (Rowe, 2016b).

• On December 11th, 2017, a vehicle collided with a train at a level crossing near the FNRAEC after it slid on the ice and snow (Deer, 2017).

• In November of 2019, some areas of Kahnawà:ke experienced service interruptions that lasted up to 48 hours due to a storm. The basements of some homes were flooded due to heavy rainfall and some roadways were temporarily blocked by downed trees caused by the high winds (fig. 36) (Fedosieieva, 2019).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 56

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 57

Figure 34. An elm tree knocked down from a windstorm (Norton, 2012).

Figure 35. A willow tree knocked down from a storm (Rowe, 2016b).

Power outages that occur in the winter are especially concerning. Carbon monoxide poisoning can result from the reliance on gas and wood stoves for heating (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015). In all seasons, the disruption in access to medical equipment and the increase in food poisoning due to food spoilage is a major concern (City of Windsor, 2012; Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

One extreme example of the effects of destructive storms is the Ice Storm of 1998, in which ice rain demolished trees, electrical infrastructure, and caused massive power outages for millions in Québec. The storm caused thousands of trees to fall, damaged cars, and even resulted in the death of over 30 people with hundreds more injured (Pindera, L., and Steuter-Martin, M., 2018).

More destructives storms in the community would entail an increase in services required by the Public Works Unit, such as increased tree pruning, storm drain cleaning, sidewalk maintenance, and snow removal (City of Windsor, 2012) (see fig. 37). In recent years, the Public Works Unit has noticed more rain events with heavy winds during the summer and fall. In the winter, there have not been any major disruptions or changes to the services required by the Public Works Unit regarding storm clean-up, apart from the winter of 2007-2008, in which snow removal services were especially expensive (Montour, 2020b).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 58

Figure 36. Downed tree on Canadian road that was knocked over from a powerful storm (Fedosieieva, 2019).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 59

Figure 37. The clean-up for one the largest snowstorms in Kahnawà:ke took 2 days to complete (Norton, 2013d).

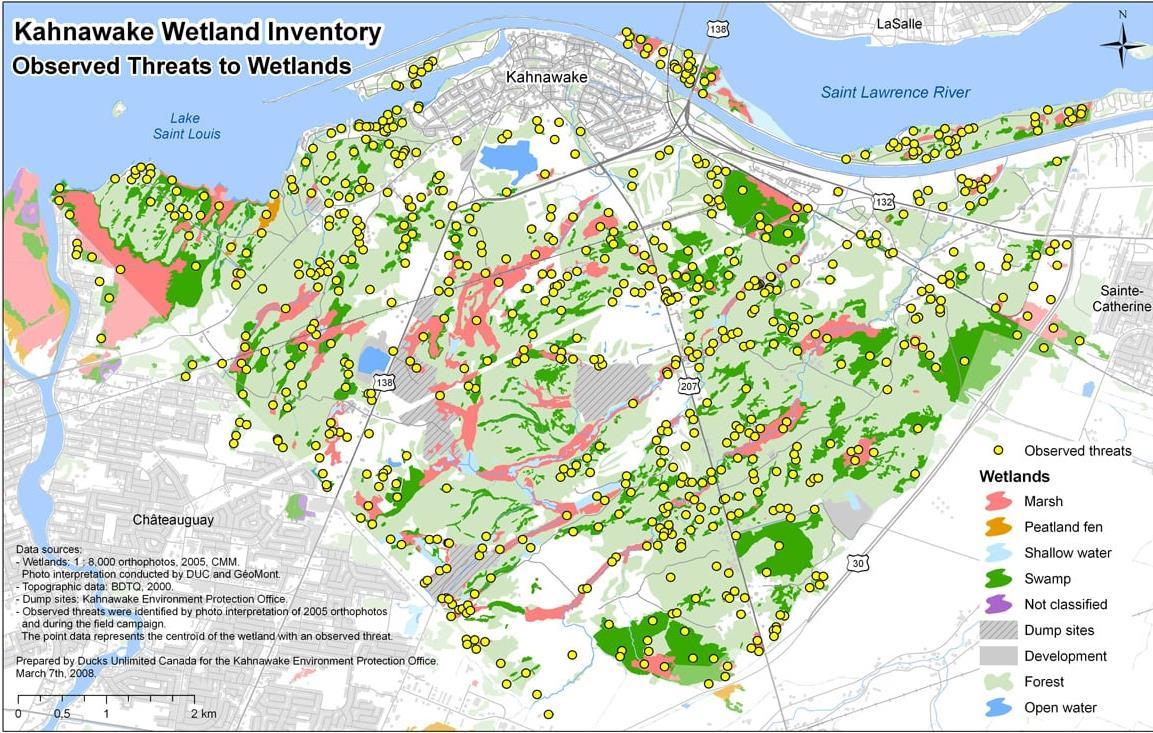

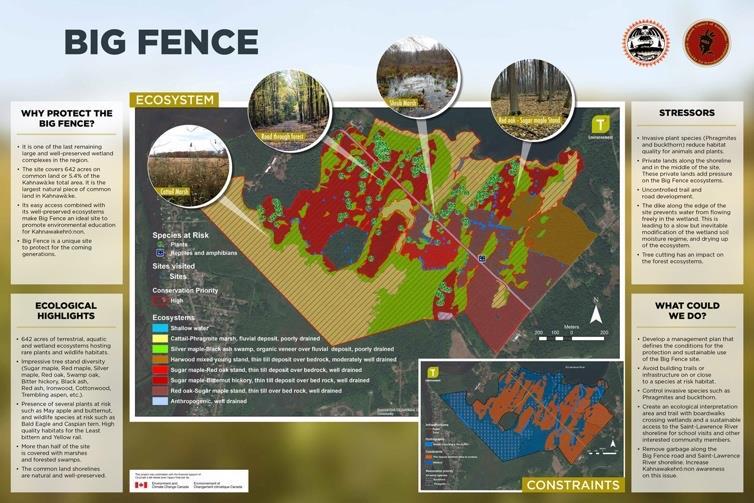

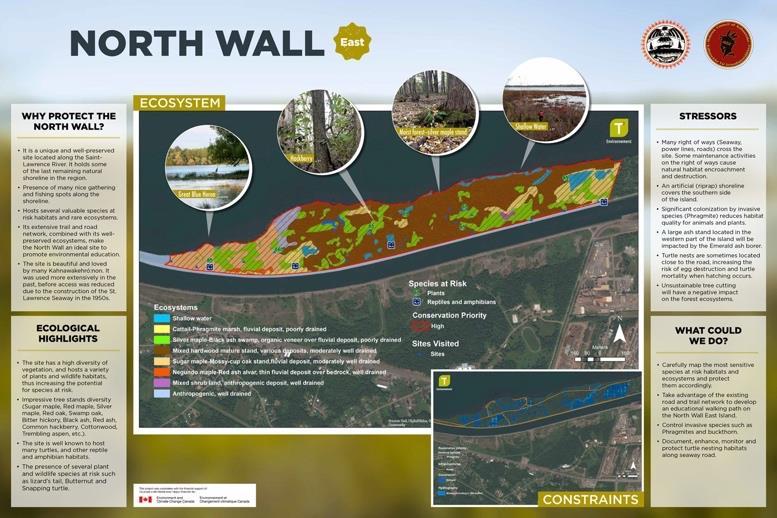

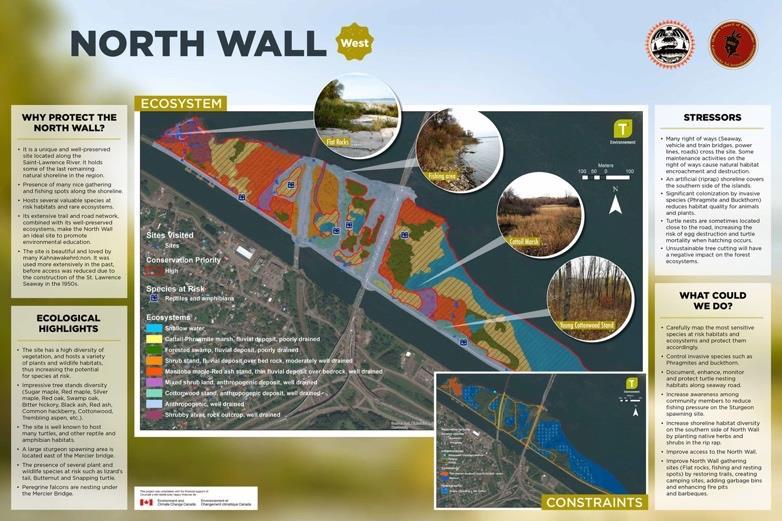

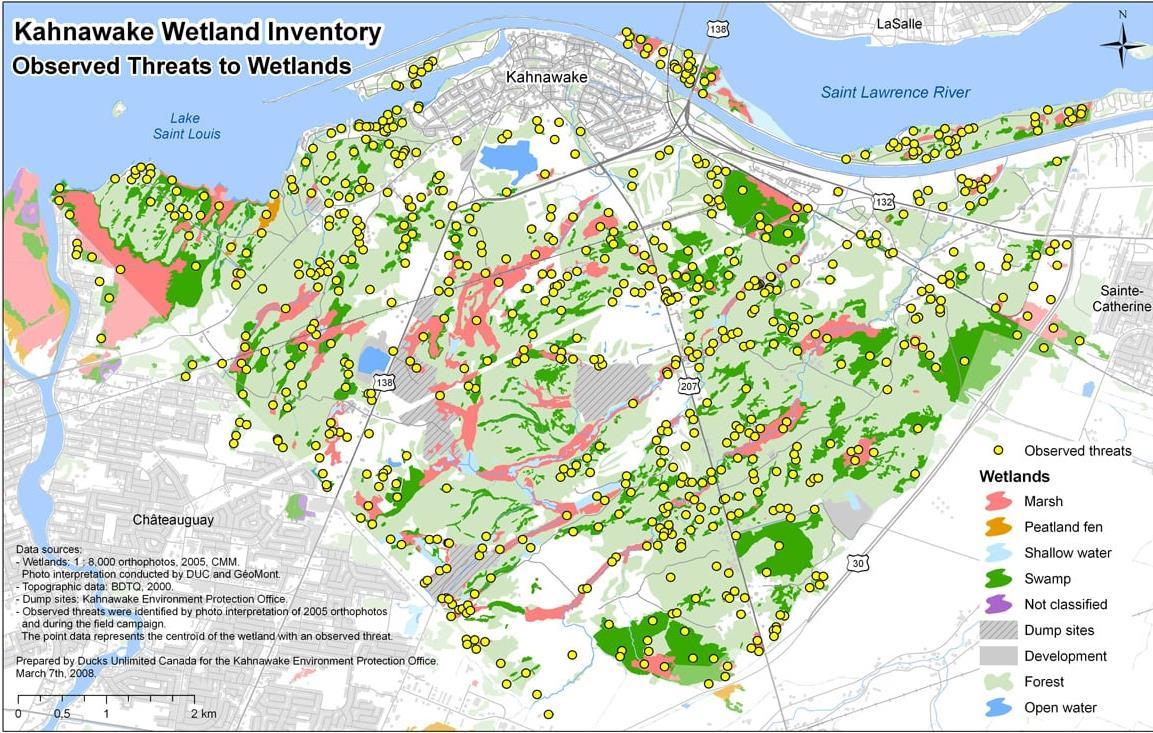

Box 8. Impacts of climate change on wetlands in Kahnawà:ke.

The wetlands of Kahnawà:ke (fig 38) are greatly threatened by the effects of climate change. Wetlands are sensitive to any changes in hydrology, as they exist between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, therefore increased flooding, drought, heatwaves, and frequency of severe storms will all have impacts on wetland functioning. Streams and small, isolated wetlands are particularly vulnerable due to changes in the timing and volumes of spring peak flows.

Over time, these changes can lead to shifts in species distributions and species communities as well as to biogeochemical changes in soil. Warming temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and changes in frequency and intensity of rainfall will alter ecological processes. Losses of native species, particularly at the southern end of their ranges, and increases in species at the northern end of their ranges, may occur. Opportunistic, easily adaptable, and invasive species, pests, and diseases will take advantage of these changes and will increase. Severe storm events may further cause structural ecological changes from which our natural communities may not rebound easily. Climate change acts with other stressors, such as urbanization, pollution, invasive species, and land use changes. Along with climate change, these stressors may disassemble existing ecosystems and lead to the emergence of new ones, further altering the benefits wetlands provide (WWA, 2018; Moomaw, 2018).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 60

Figure 38. The different wetlands of Kahnawà:ke and their observed threats (KEPO).

5. Heavy Rainfall

During a heavy rainfall episode, basements are at risk of flooding for two main reasons Many homes in the community are built on former wetlands, therefore many homes must rely on sump pumps (in some cases, running almost continuously) to avoid flooding during heavy rainfall. Flooding can thus occur as a result of overworked or faulty sump pumps. In addition, the combination of high infiltration rates into sanitary sewers from broken pipes and/or leaky connections can lead to sewage backup. Certain buildings and homes can suffer from a sewer backup during this time caused by a high-water table due to climate change. Basement flooding can also occur when the flow of stormwater in sewers increases rapidly in a short span of time.

Basements are particularly at risk to flooding if they are built on uneven ground or if a garage entrance is sloped toward the building. The flooding of buildings and homes is responsible for considerable economic losses, most notably, costs related to the destruction and damages to properties and related insurance costs (IBC, 2019). In addition, flooding can lead to indoor mould growth, which can cause a variety of respiratory problems, such as: eye, nose and throat irritation, coughing and phlegm build-up, and wheezing and shortness of breath (Health Canada, 2020). Mould growth can also lead to increased expenses in order to remove the mould, which often requires professional assistance.

To avoid flooding from combined sewers, these systems are designed to have emergency overflows that direct untreated wastewater into nearby water bodies, a situation that occurs way more than one might think. Combined sewers and sewer overflows are not usually a direct concern in Kahnawà:ke but they do impact water quality of the St. Lawrence as most adjacent communities do have combined sewers and climate change will increase the frequency of these discharges.

Flooding can have significant impacts on human health as well. These include carbon monoxide poisoning due to poor use of combustion appliances during power outages and gastroenteritis due to the consumption of contaminated food and water. Flooded buildings also have a greater risk of developing mould which can cause serious respiratory problems, especially for those with underlying health issues like asthma (Ville de Montréal, 2014a). Psychological issues are also likely to occur, such as stress for the victims of flooding and stress for the volunteers and workers who support them. In addition, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are potential side effects (Gouvernement du Québec, 2015; Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 61

Box 9. Landmark event – flooding in Kahnawà:ke.

Heavy snow throughout the winter coupled with large amounts of rain and warm temperatures caused flooding in the community on April 11th, 2014 (fig.39). The water treatment facility received complaints from community members regarding their drinking water. This was caused by an increase in the amount of chlorine that needed to be added to compensate for the increase in the turbidity of the water because of the flooding (Rowe, 2014).

Stormwater runoffs can also damage the road network (particularly culverts) and sewer system of Kahnawà:ke. This can result in service outages, such as electricity, telephone, and Internet. In addition to reducing mobility within the territory, floods can cause accidents, injuries and deaths (WHO, 2018; Ville de Montréal, 2014a). In 2011, two residents of the Mohawk community of Ganienkeh died in a flood (Lotemplio, 2011) The losses were felt throughout all Mohawk communities as our culture is very familyoriented and grief for the death of our people reverberates beyond geographic borders.

Heavy rainfalls can also result in waterlogged soil, leading to lower oxygen levels in the soil and soil compaction. These effects can exacerbate the susceptibility of plants to root diseases (SRMT, 2013), which has serious cultural implications. Corn (one of the Three Sisters) has been shown to be particularly vulnerable to increased soil moisture (Rosenzweig et al. 2002). In addition, heavier rains can increase erosion and runoff, removing agricultural topsoil and increasing the flow of pollutants into our waterways

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 62

Figure 39. Flooding caused by heavy rain and warm temperatures at the intersection of Highway 138 on the border of Kahnawà:ke and Chateauguay (Rowe, 2014).

(Climate Central, 2020). The overflow of wastewaters in waterways increases the quantity of pathogenic organisms and pollutants, increasing the risk of contamination (Ville de Montréal, 2014a).

Heavy rainfall episodes can also result in increased deployment of the MCK Public Works Unit to clear street drains from leaves and small branches to prevent flooding (Montour, 2020b).

6. River Floods

Flooding from the overflow of the St. Lawrence River can result in damages to wildlife habitat and the built environment of Kahnawà:ke, especially to buildings located in flood plains.

The impacts of a river flood are like that of a rainfall-induced flood (as mentioned above). However, they differ in that river floods can provoke the erosion and destabilization of riverbanks. This is harmful to the aquatic environment as eroded riverbanks bring sediments into the water, impairing its quality and reducing the hospitability for wildlife (Cameron & Bauer, 2014).

Spring floods can also impact the health of Kahnawa’kehró:non by bringing about gastrointestinal illnesses through direct contact with the flood waters (WHO, 2018; Denchak, 2019).

Finally, river floods require additional resources and personnel responsible for the implementation of emergency response measures.

• Increased prevalence of diseases in animals

• Early arrival of some pest insects

• Increased insect population

• More frequent insect infestations

• Risk of desynchronization between insect pests and their natural enemies

• Damage to the road network and adjacent structures

• Accelerated degradation of bridges, tunnels and overpasses leading to falling fragments

• Breaks to underground pipes

• Health problems caused by air pollution (pollen) increased exposure to UV rays

• Vector-borne and zoonotic diseases

• Stress and panic-induced conflict.

• Increased use of abrasives

• More days for construction work under better conditions

• Greater demand for resources (seasonal employees)

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan 63

Natural environment Infrastructure Socioeconomic issues MCK Operations Animals Public Health Infrastructure

Table 4. Potential impacts of a higher average temperature in Kahnawà:ke.

Park and greenspace management

Kahnawà:ke Climate Change Plan

• Increased costs and labour for green space maintenance

Plants Culture Recreational activities

• Longer pollen season

• Changes to plant phenology

• Faster plant growth

• Change to plant hardiness zones

• Increased appearance of invasive / undesirable plant species.

• Disruptions to ceremony (planting season based on the moon & stars)

• Culturally important plant species at risk (i.e maple, ash)

• Changes to growing conditions for medicines

• Demand to extend the opening season for pools, splash pads and sports fields

• Extended use season for the bicycle path

• Difficult and costly maintenance for outdoor skating rinks

Pathogens

• Larger geographical distribution area

• Higher rate of reproduction

Natural environment Infrastructure Socioeconomic issues MCK Operations Animals Public Health Drinking water

• Reduced insect populations

• Increased management of pest insects

• Changes to bird communities

• Damage to the road network

o Loss of adhesion between asphalt and bridge decks

o Premature damage to the expansion joints on civil engineering works

o “Slippage cracks” in the asphalt

• Health problems caused by air pollution (smog, fine particles, pollen)

• Illnesses caused by contaminated swimming water

• Health problems linked to body

• Higher costs for chemical products and electricity

• Increased presence of cyanobacteria in the water

• Clogged membrane filters

• Faster degradation of chlorine in the

64

Table 5. Potential impacts of more frequent heat waves in Kahnawà:ke

o Ruts formed on driving surfaces

• Damage to the sewer system caused by the increased generation of H2S, harmful to concrete infrastructure

• Thermal expansion of rails

temperature imbalances

• Health problems caused by limitations to mobility

• Increased premature death rate

system, which will increase rechlorination needs and associated operating costs