KATIE MUELLER

Master of Architecture Candidate

Harvard Graduate School of Design

Master of Architecture Candidate

Harvard Graduate School of Design

GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

Aug 2017 - Dec 2021 | GPA: 3.89; Bachelor of Science in Industrial and Systems Engineering; Concentration in Supply Chain Engineering; Minor in Architecture

GEORGIA TECH TOUR GUIDE

Jan 2018 - May 2021 | Provided tours for prospective students and informed their decisions to attend Georgia Tech

GEORGIA TECH AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERS PRESIDENT & TREASURER

May 2018 - Sep 2019 | Registered 500+ members and promoted member engagement; Organized the chemical engineering career fair and weekly recruiting lunches; Allocated funds from sponsorships, invoiced companies, and managed ~$60k budget

DOW CHEMICAL COMPANY PROCESS ENGINEERING INTERN

May 2018 - Jul 2018 | Analyzed and presented data to reduce the time a product spends in the tank; Developed an instructional batch sheet for operators when assembling recycled ion exchange canisters

TECH THE HALLS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & EVENTS DIRECTOR

Jan 2019 - May 2021 | Led rebranding/restructuring effort to transform the organization from a semester-long to a year-round program; Planned and executed event involving ~150 students from Georgia Tech and ~70 children from Boys and Girls Club

EXXONMOBIL CRUDE OIL DISTILLATION INTERN

Jan 2019 - May 2019 | Scoped and budgeted a proposal for a new line of piping for a distillation tower; Optimized heat transfer fluid rate for a furnace air preheater system; Increased margin on dewaxed oil product

INSTITUTE OF INDUSTRIAL AND SYSTEMS ENGINEERING PROFESSION PLANNER

Jan 2020 - May 2021 | Helped plan and manage professional recruiting events; Led scholarship selection committee

EXXONMOBIL GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN INTERN

Jun 2020 - Aug 2020 | Analyzed third-party trucking data and created future analysis plan; Performed a cost analysis of various packaging types for Vistamaxx product

EAST ATLANTA ENGINEERING FOR KIDS

Jan 2021 - May 2021 | Taught engineering courses to children in Pre-K through 5th grade; Served as an administrative assistant for the program

DELTA AIR LINES

Jan 2022 - Jul 2022 | Created future service pattern for Caribbean flights; Developed timeline and action plan for servicing new terminal in LAX

HARVARD GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN

Aug 2022 - Present | Master in Architecture I

SKILL: MATLAB

ABROAD: Monte Cristi, Dominican Republic, one-week teaching trip

SKILL: Microsoft Office Suite

AWARD: American Institute of Chemical Engineers Freshman Recognition Award

ABROAD: Lorraine, France, threemonth study abroad

DECISION: Change of major from chemical engineering to industrial and systems engineering

SKILL: Python

SKILL: Simio

SKILL: SQL

AWARD: Semmes Memorial Scholarship

SKILL: RStudio

SKILL: Adobe Creative Suite

SKILL: Rhino

DECISION: Apply to Master in Architecture programs

AWARD: Highest Honors

instructor: agustina labarca 2021

During my time in Harvard’s Design Discovery Virtual program, I became acquainted with a variety of design programs and philosophies. Using programs such as Rhino, Photoshop, and Illustrator, I explored the areas of public spaces (publics), social justice, and climate change through the lenses of one urban setting, one housing complex, and one landscape. I selected Tiong Bahru, Singapore, the single-loaded bar, and the large urban park as my urban setting, housing complex, and landscape, respectively. These selections were made based on their similarities to spaces from my own experiences and the challenges that I wished to address. The Design Discovery program provided me with base plans, sections, and axononmetric projections of these different settings, which I then altered to express the ideas that I had about these settings based on readings, discussions, and independent research. Throughout the program, I primarily focused on how peoples’ biases impact their use of space, how alterations in space can impact social interactions, and how to adapt spaces to prepare for climate change.

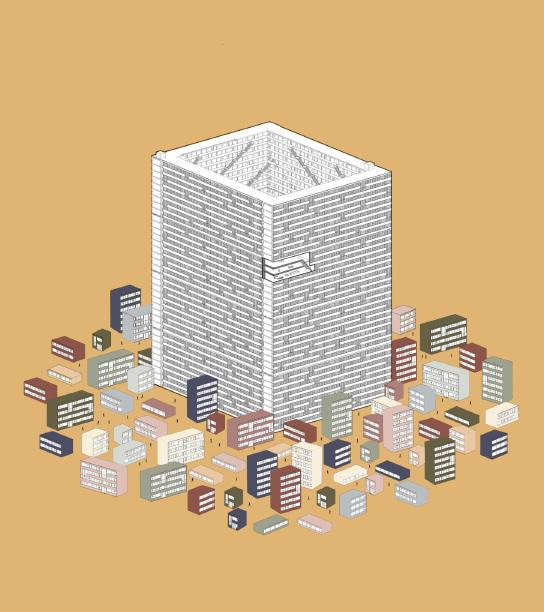

Tiong Bahru, Singapore:

Selected because of its history with gentrification, Tiong Bahru was the original public housing district in Singapore. It has since had many expensive, private complexes pop up, creating a divide between old and new. I explored how this divide has been and can be shaped by design.

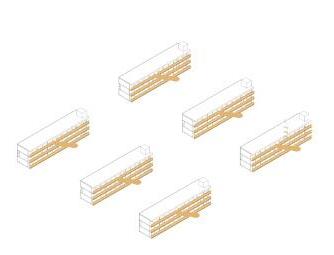

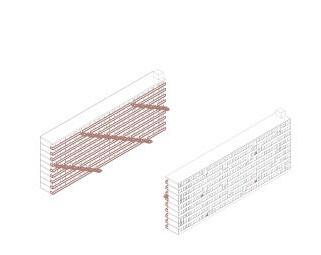

Selected because of its unique layout and ability to house many, the singleloaded bar typically consists of multi-story apartments accessible from one external corridor for each floor. I considered how the space could be altered to adapt to and create a variety of conditions.

Selected because of its similarity to Piedmont Park in Atlanta, the large urban park often serves as the primary means of outdoor access for city dwellers. Throughout the program, I explored how the landscape might be impacted by changing climate conditions over time.

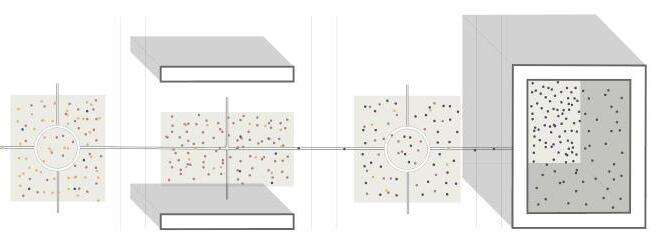

During the Black Lives Matter protests of the summer of 2020, I became increasingly aware of the white privilege surrounding my own life and the lives of so many around me. I saw firsthand how easy it was for some to ignore the struggles of those around them. To express this phenomenon, I created the collage below to represent the idea that someone can be living in the midst of a crisis yet still be able to turn a blind eye to it. I then used this collage as inspiration for the image to the right, which depicts the idea that even though two groups may occupy the same space, the existences of those groups can be very different.

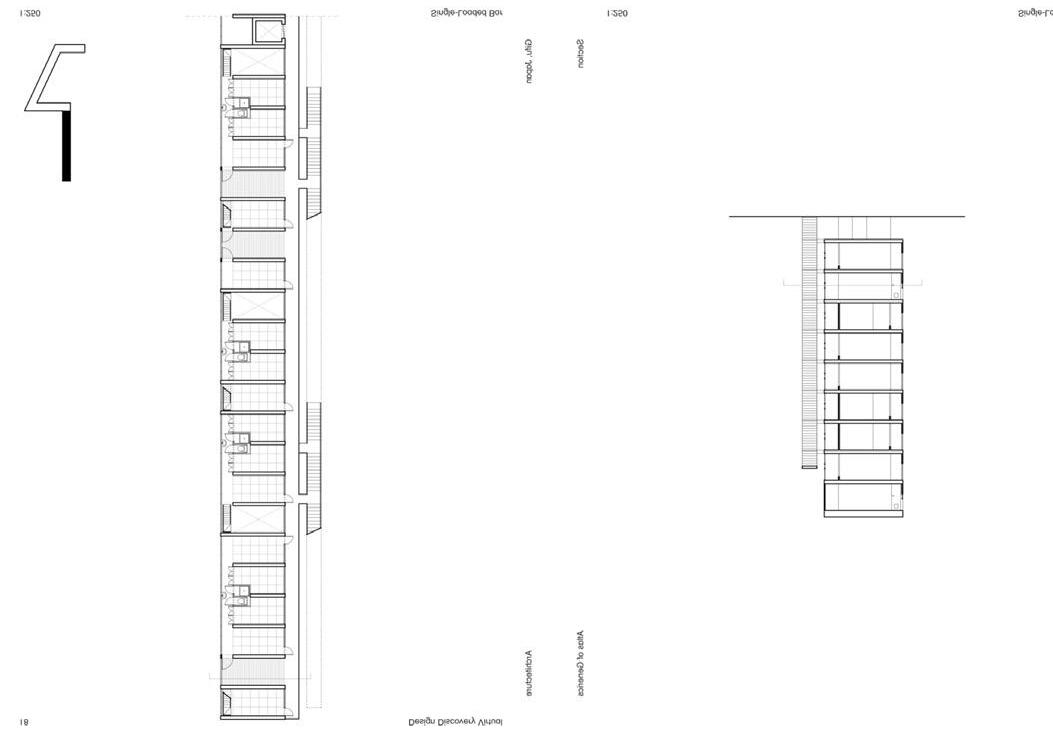

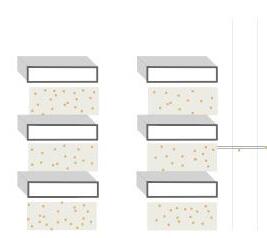

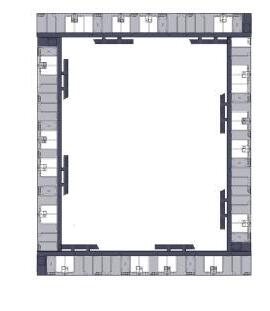

Throughout the program, I was fascinated with how space can impact social conditions. To explore this theme, I created a “Single-Loaded City” that consists of three different housing complexes, all constructed using a base model of a singleloaded bar complex. At the city level, I used dots to represent how these complexes impact the locations of social interactions between residents of the different complexes. At the complex level, I used thickness of colored lines to represent the density of interactions between residents of the same complex. At the floor level, I used darkness of color to represent shared spaces.

CLIMATE CHANGE

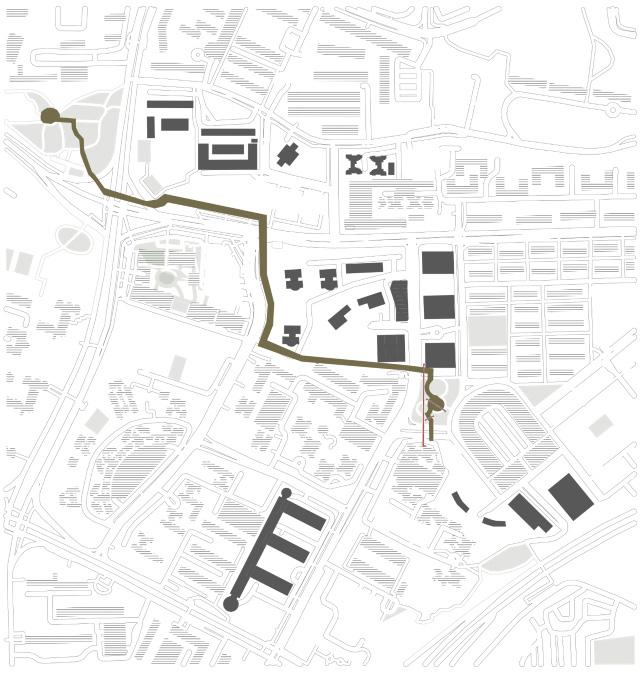

Throughout my investigation into Tiong Bahru, I focused on gentrification and increased rainfall. To address these challenges, I wanted to create a space within the city to connect people to nature and to each other regardless of the outdoor weather conditions. To do this, I created a covered, outdoor pathway that connects two parks on opposite ends of the city. This pathway runs between a set of public and private apartment complexes and will be accessible to those with a variety of socioeconomic statuses. This pathway is also two levels to allow for use during different weather conditions. The roof at the top level can be used for rain protection, and the trees at the bottom level can be used for shade. In addition, two covered garden spaces will allow for usable community areas during any weather condition.

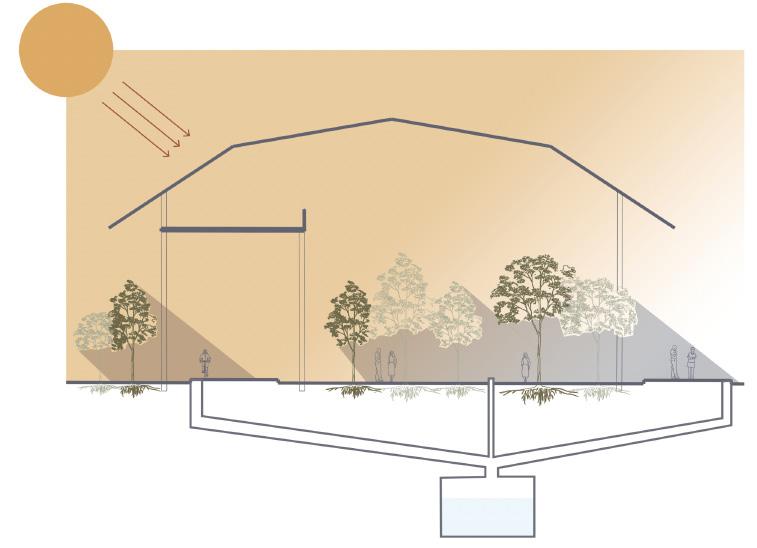

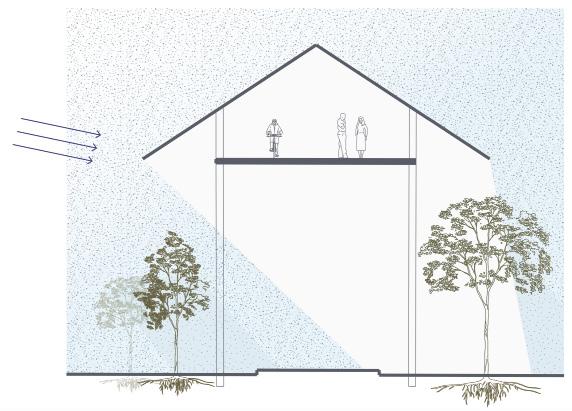

1 Polycarbonate Roof: The polycarbonate roof allows light to enter the upper level and people to see out. This level is good for rainy days but likely will not be used as frequently on hot, sunny days.

2 Walkway Shade: Since the roof of the pathway does not provide any shade, trees along the path will be used to provide shade for pedestrians.

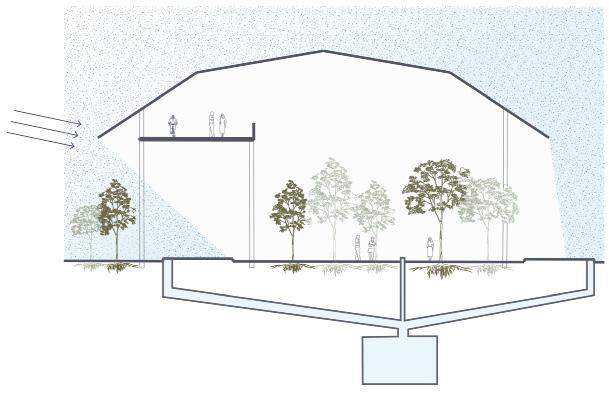

3 Garden Shade: The polycarbonate roof of the covered garden will allow light in. Therefore, the trees will function as the main source of shade within the garden.

4 Air Flow: The large, open sides of the covered garden allow for air flow. This prevents discomfort on days when it is not raining and will allow pedestrians to take advantage of the garden as a community space even when they do not need cover from rain.

5 Wind Direction:

Wind blowing during monsoon season may cause rain direction to change. The sloped roof of the upper level of the pathway prevents rain from penetrating the upper path.

6 Roof Opening:

The opening between the roof and the floor allows air to pass into the upper level, preventing the feeling of stuffiness.

7 Pathway Connection: The covered garden is connected to the pathway and can be accessed from the upper level via a set of stairs.

8 Sprinkler System: Since the plants in the covered garden will not have direct access to rainwater, the rainwater outside of the garden will be collected and sent upward into a sprinkler system that will run at night to keep the plants alive and healthy.

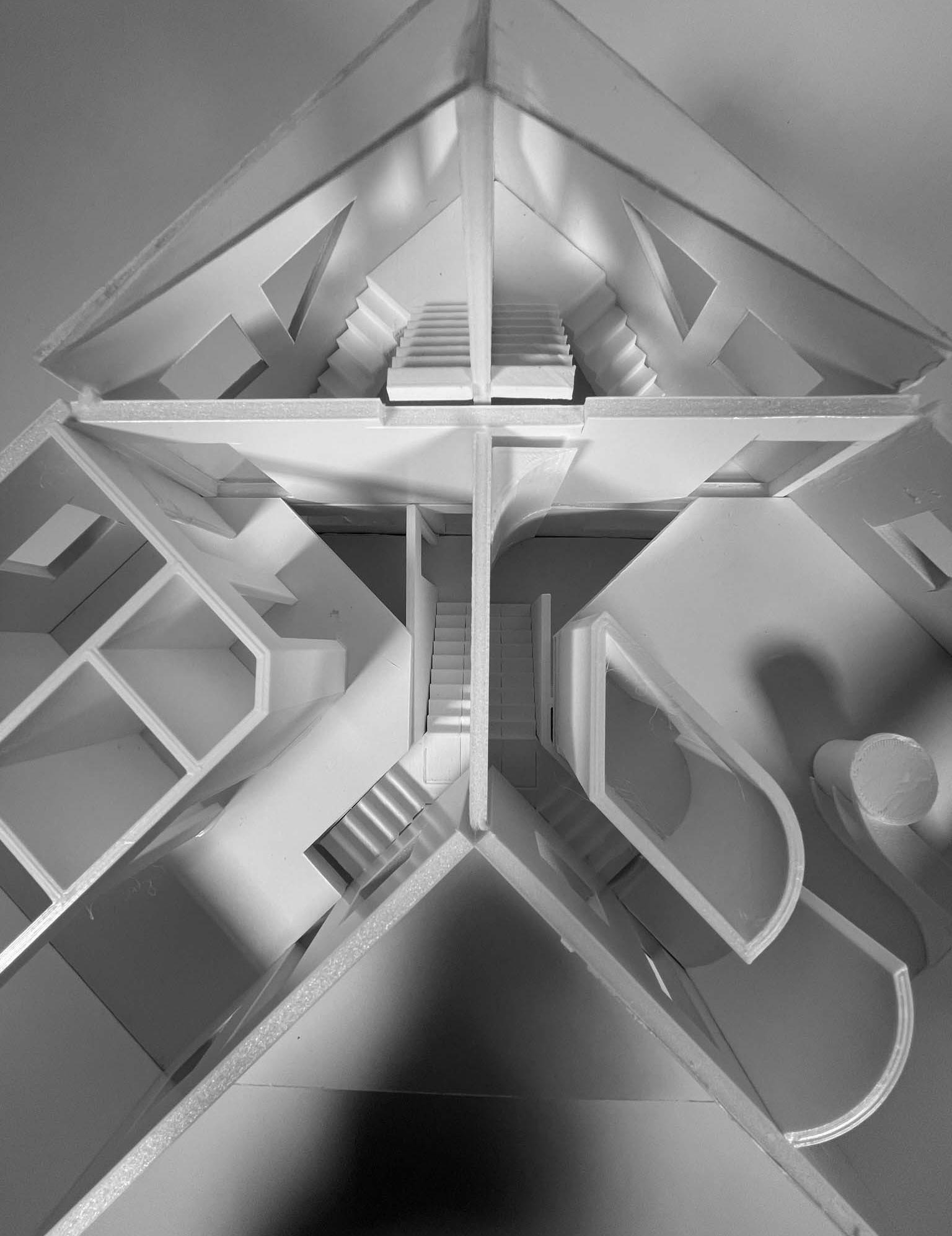

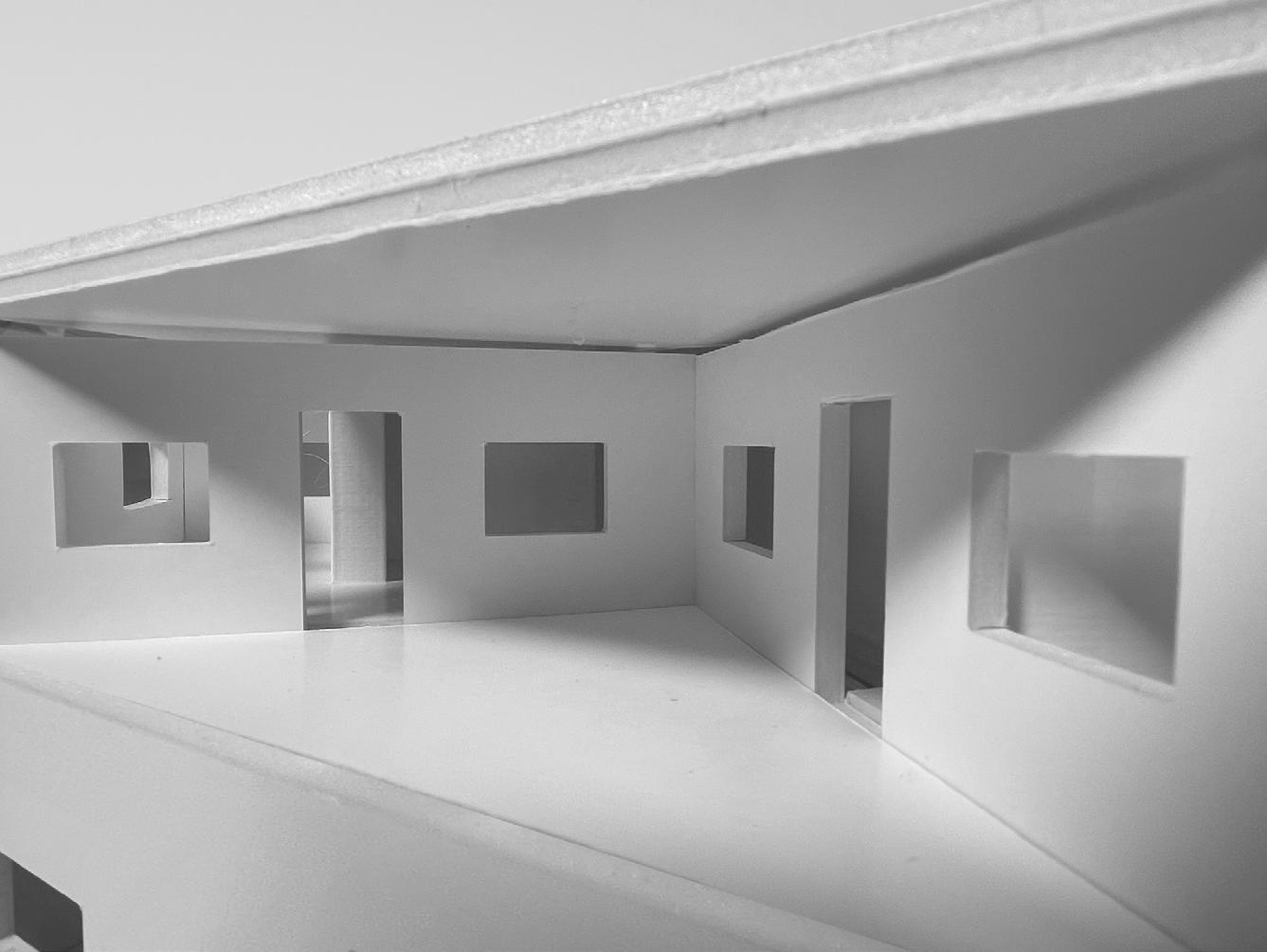

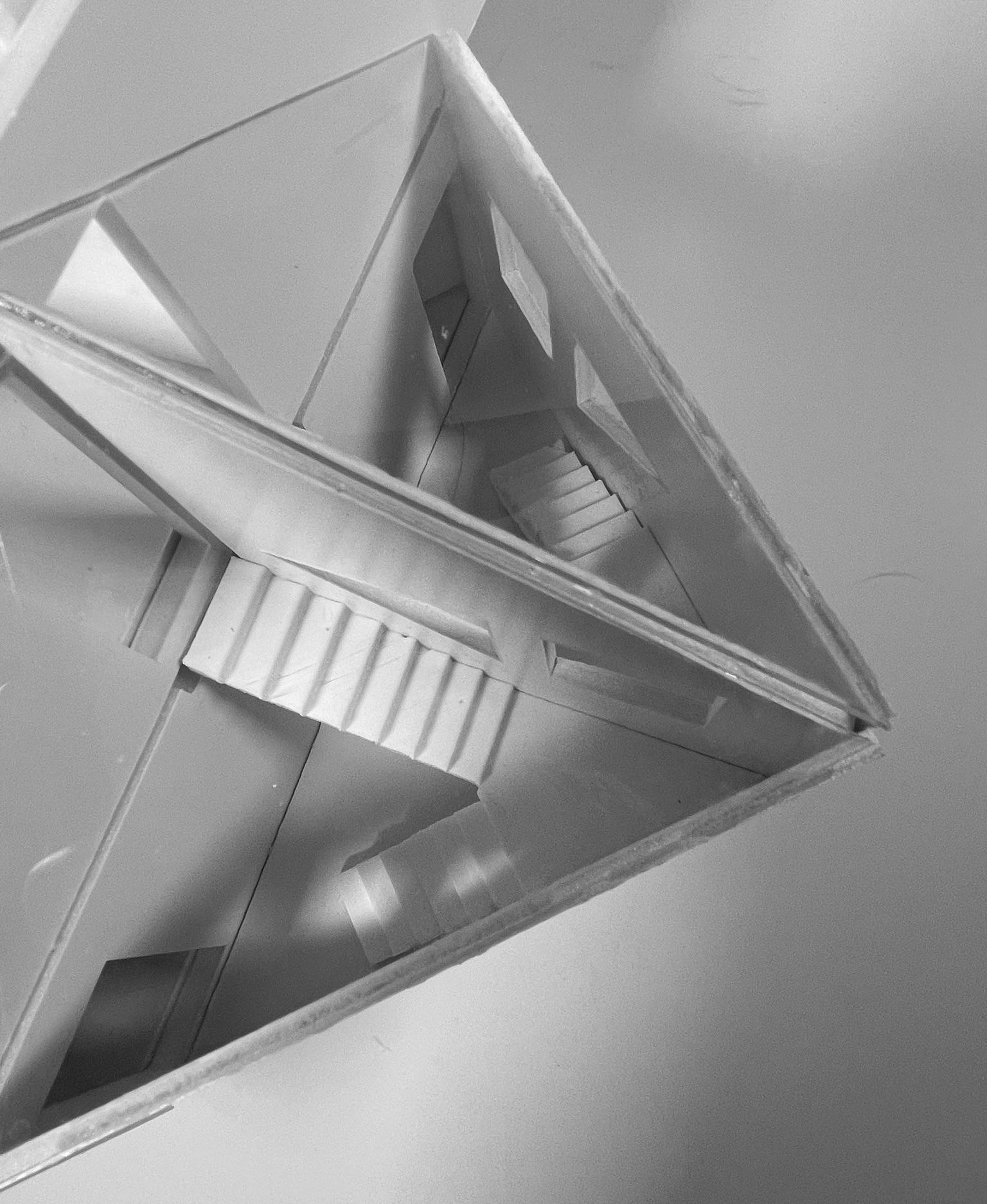

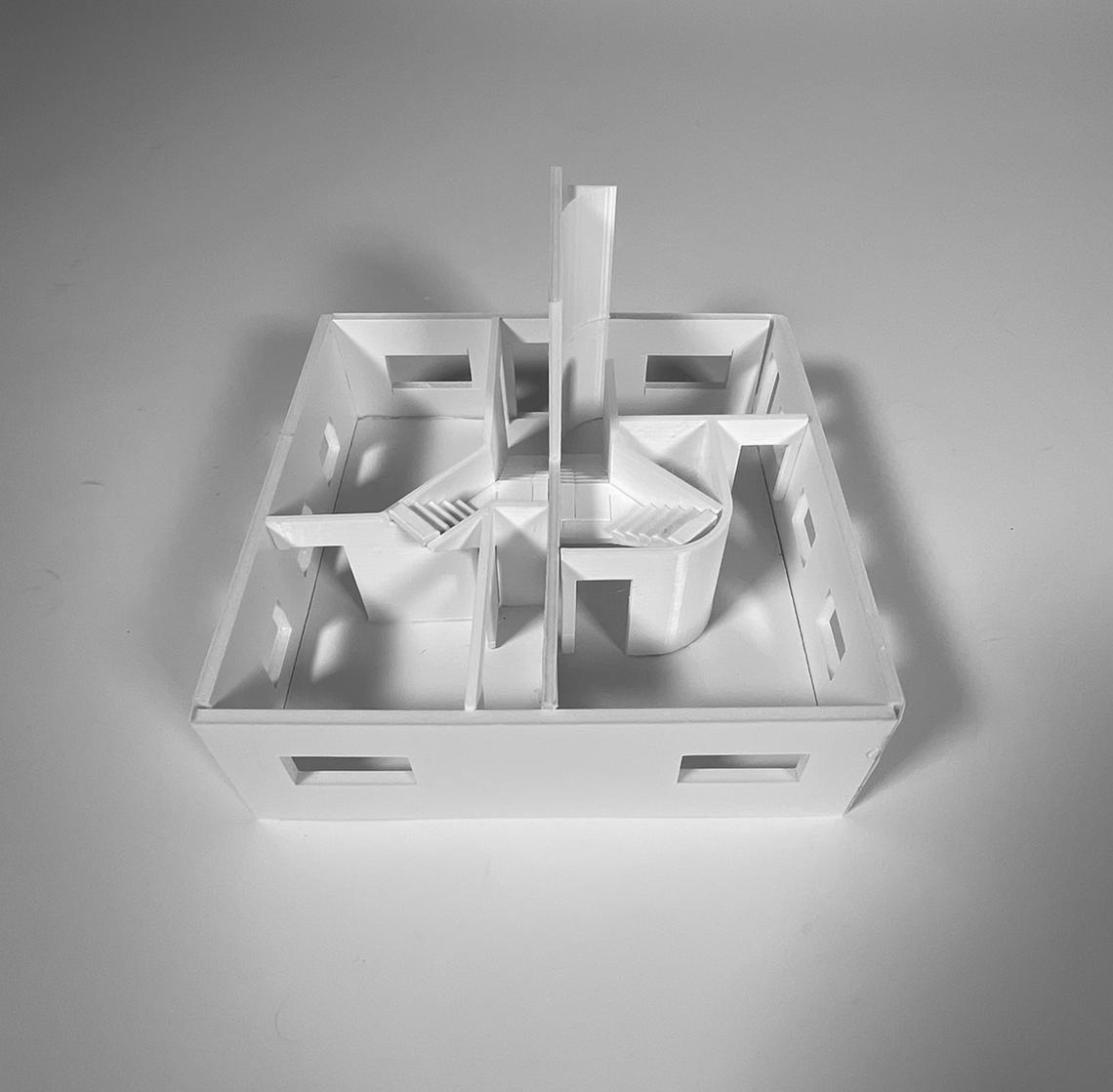

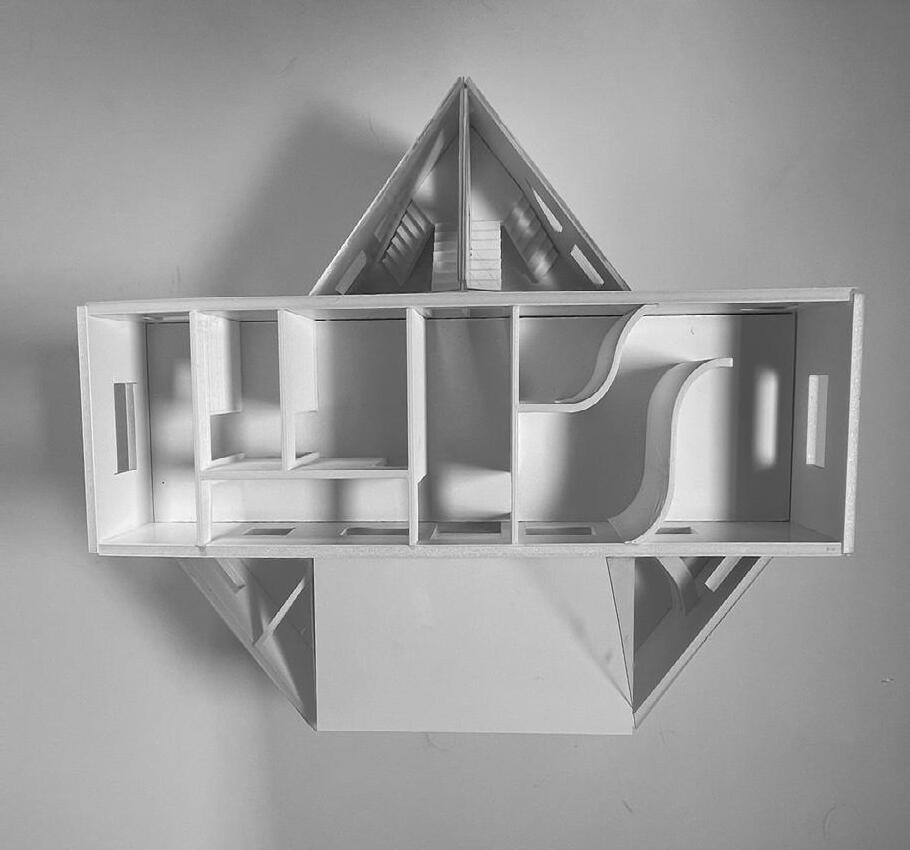

CORE I: LIVING SINGLE, LIVING TOGETHER

instructor: helen han 2022

This Core I project entailed creating a duplex with two private homes and a required amount of shared space based off of a given plan for one of the floors. In order to create the shared space, I used the logic of a zipper to create a shared porch that enlarges as you move up the different levels. In addition, I used this project to explore how a building reads in plan. I used the juxtaposition between curved walls and rectilinear ones to show an explicit example of how these two different languages can be perceived in plan, and through photography I showed how those same differences appear in three dimensions.

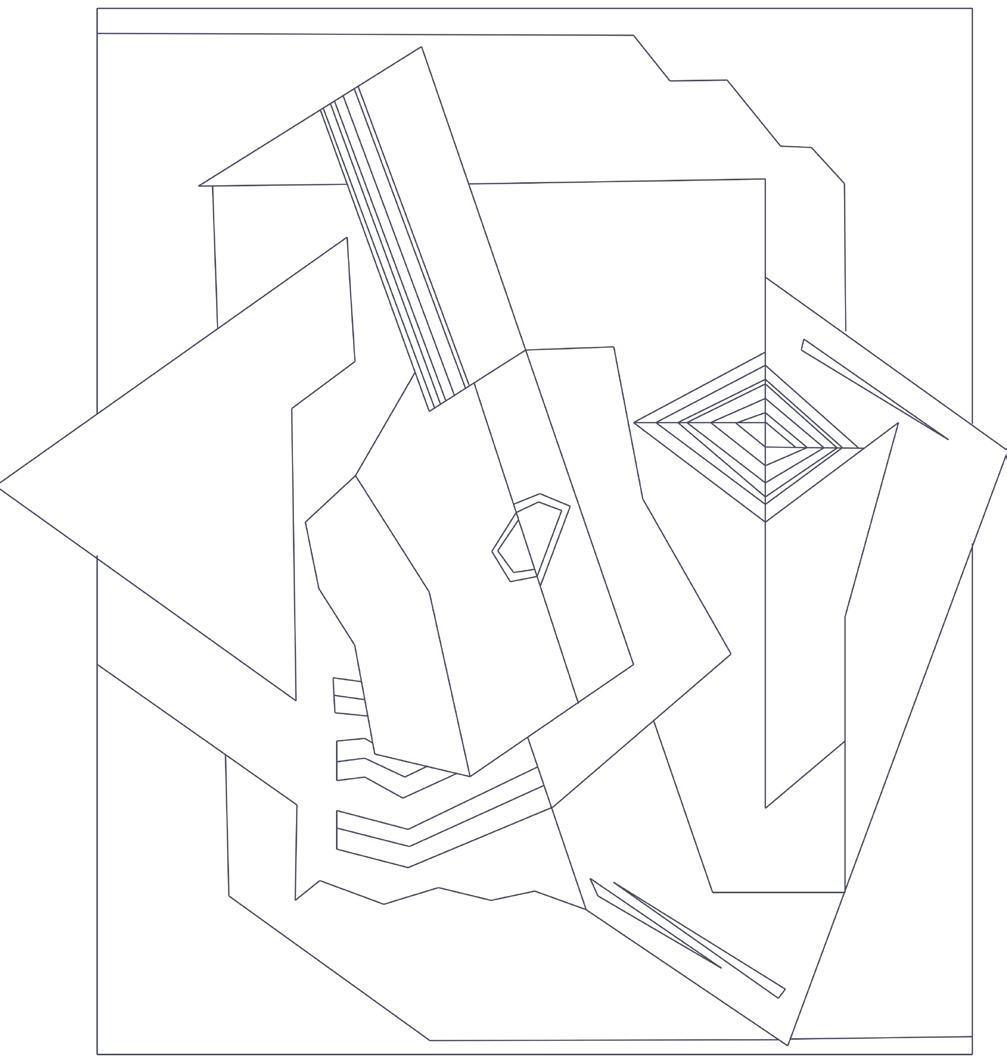

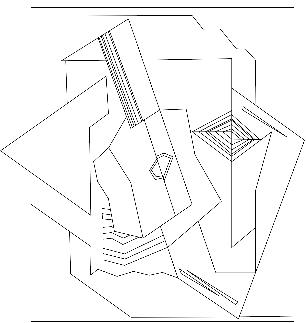

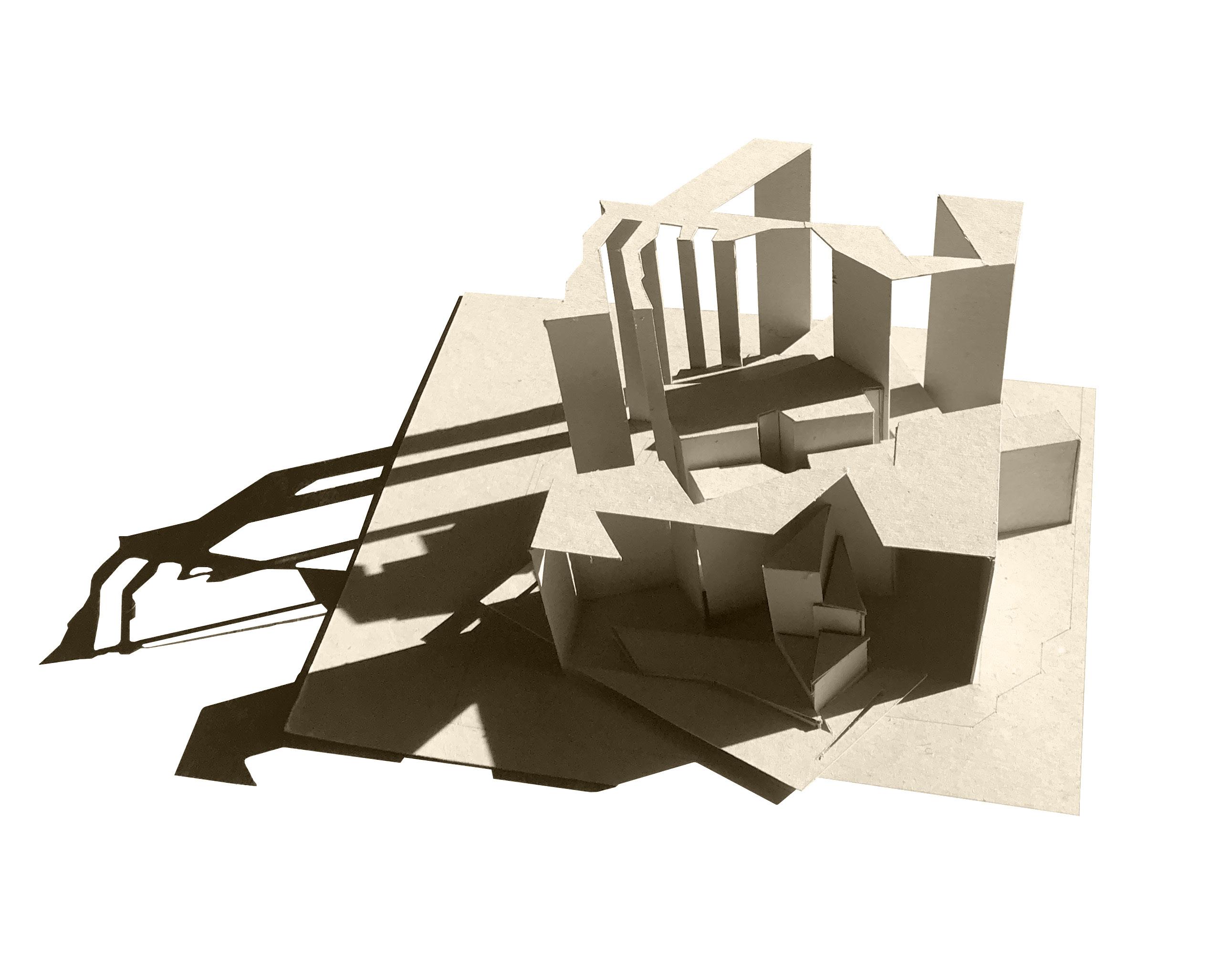

MODERN ARCHITECTURE AND ART WORKSHOP

instructor: harris dimitropolous

2018

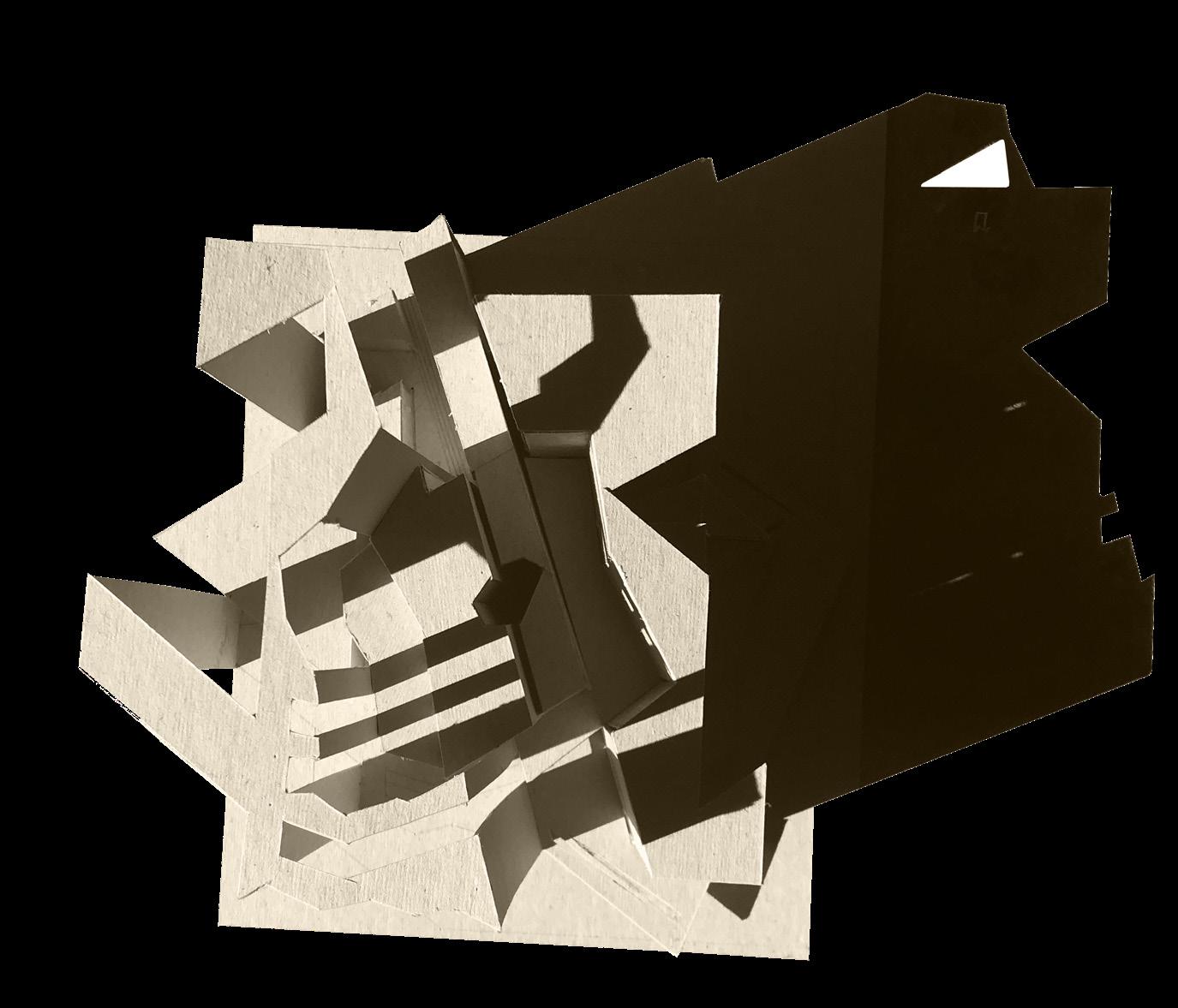

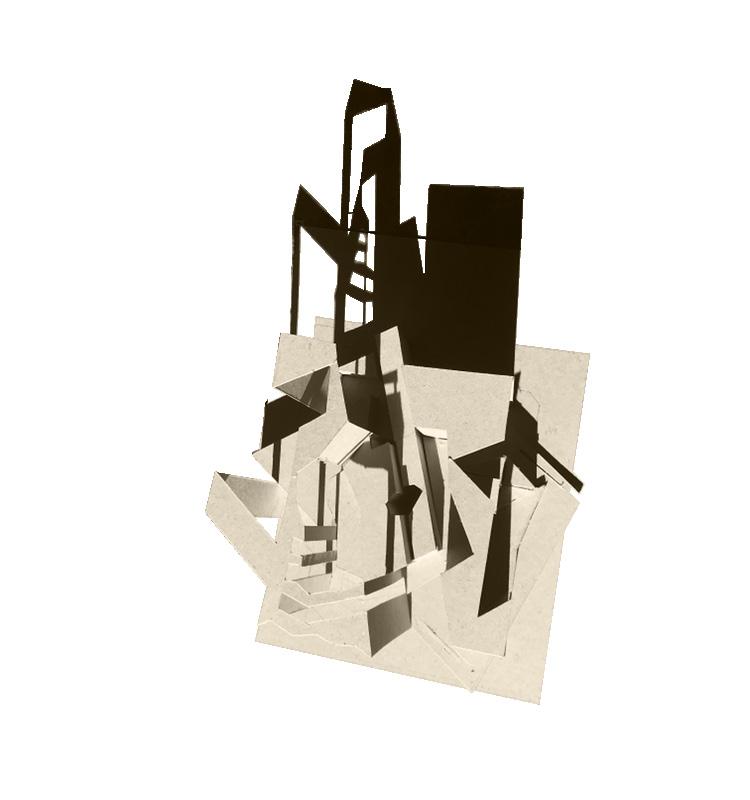

As the first project in an introductory architecture course, this project was designed to help students gain an understanding of the Cubism movement and to introduce students to the idea of designing in three dimensions. I began the project by selecting a piece of art created by Juan Gris. I then simplified this image in Adobe Illustrator and transferred it to a cardboard base. Finally, I created a threedimensional model by raising different sections of the painting to various heights. I then photographed the model, giving me a better understanding of how angles and shadows impact perception.

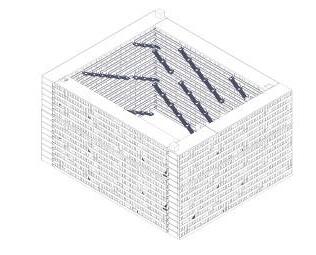

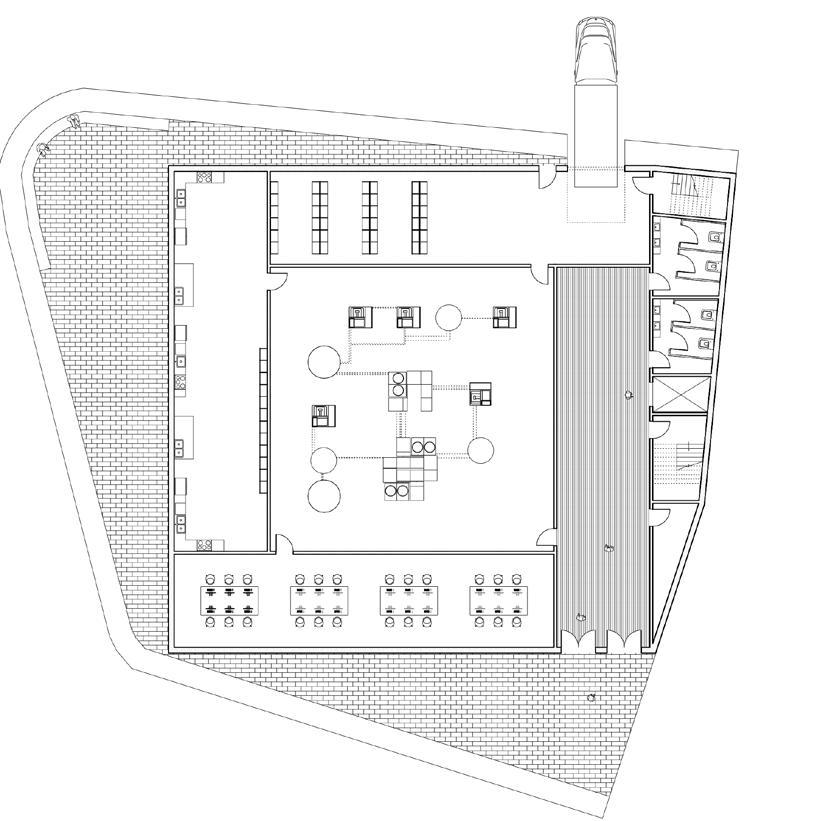

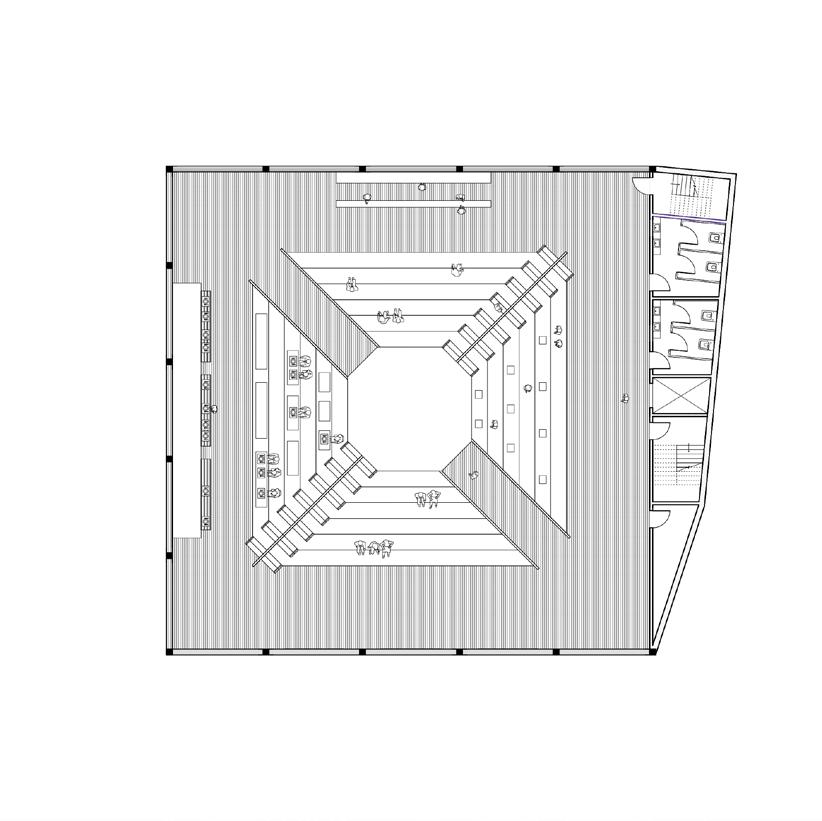

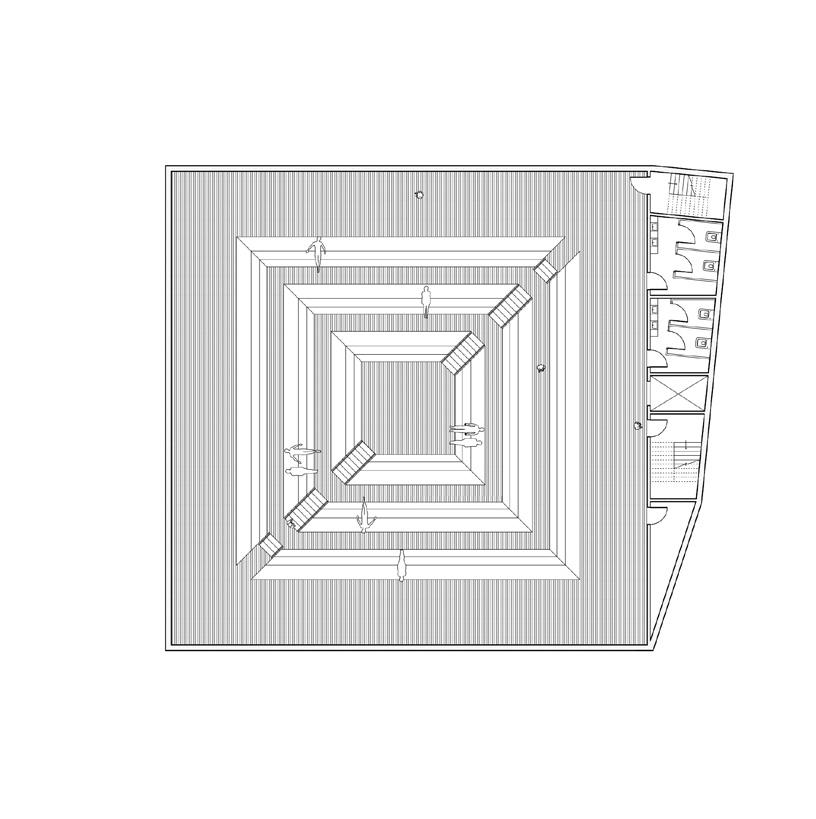

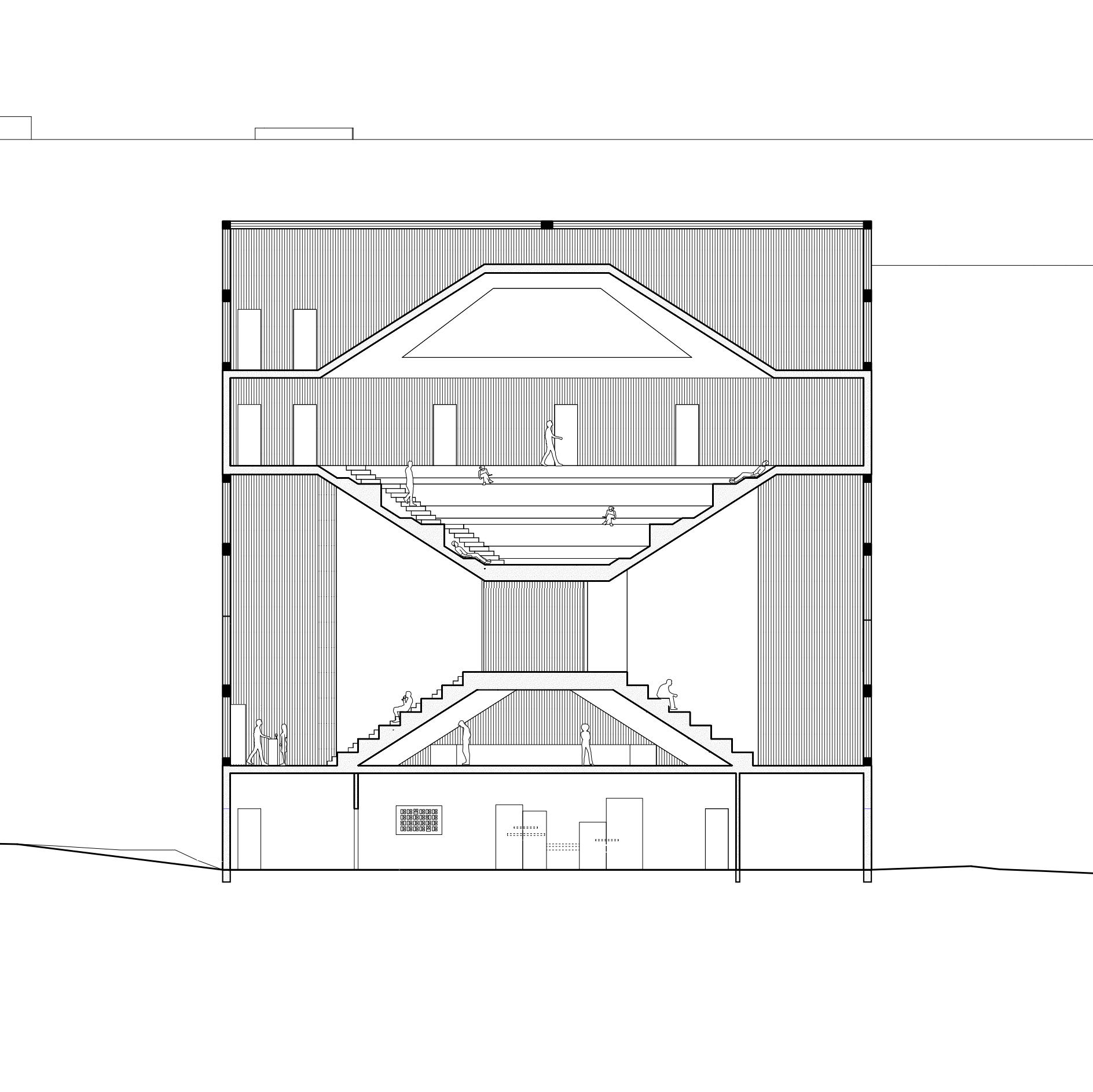

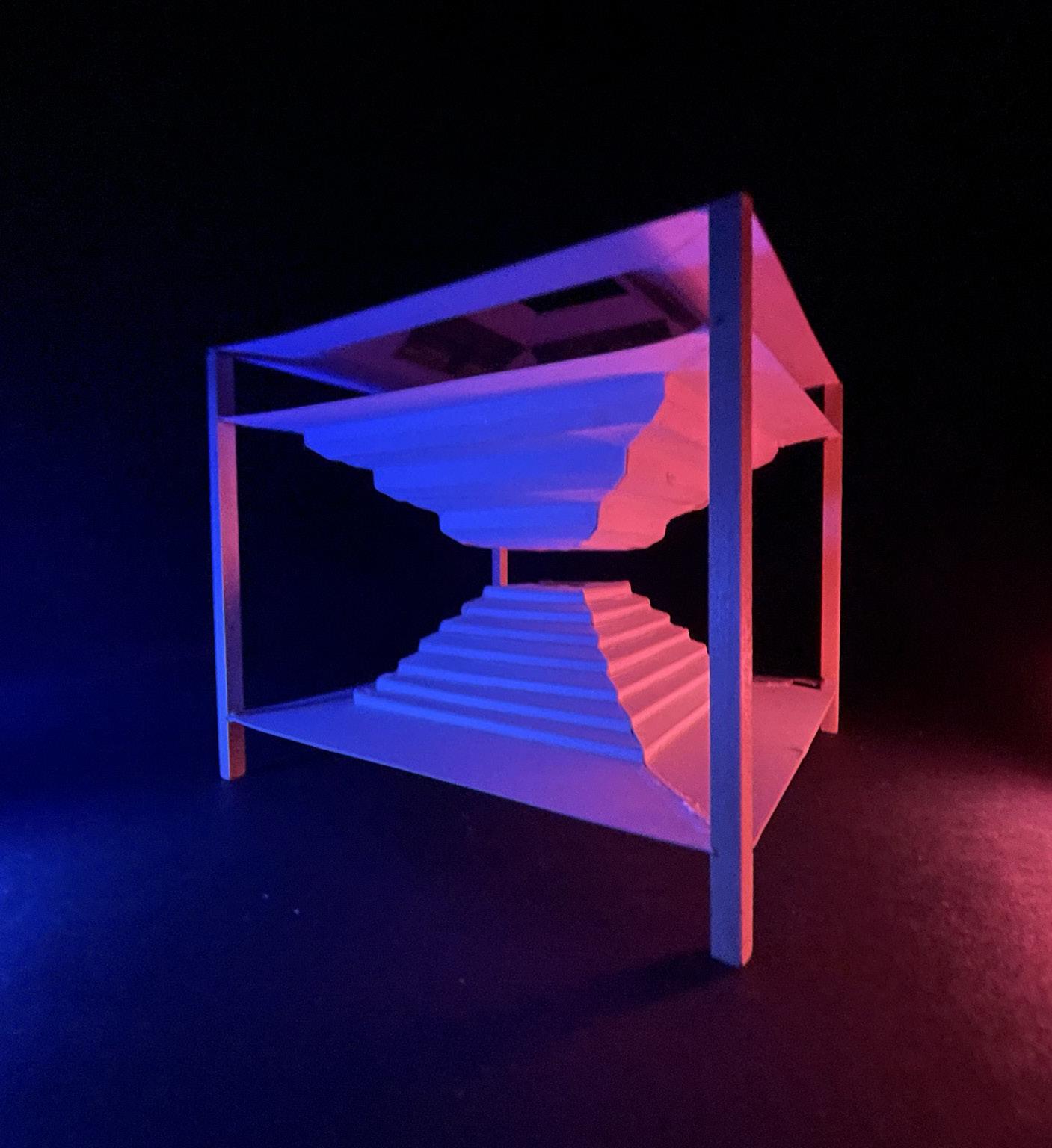

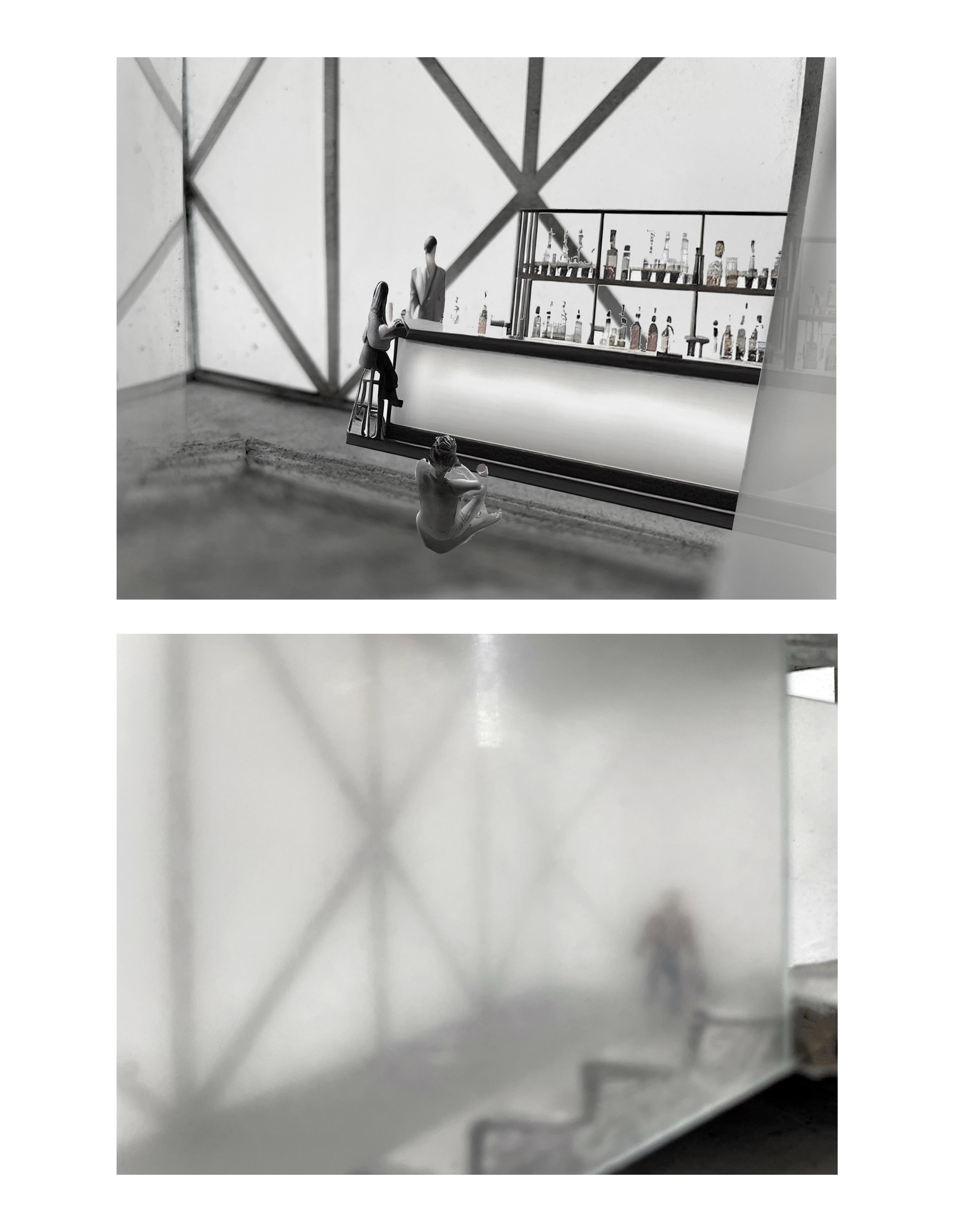

In this assignment, I was tasked with creating a site-specific picture house with a program that included a kitchen, lounge, exhibition, back-ofhouse, and, most importantly, a theater. I drew inspiration from the movie “We Need to Talk About Kevin,” taking notes from the way it hints at the conclusion in bits and pieces before all is made clear in the final scenes. On the outside, this building is a nondescript cube, offering little insight into what’s housed within. Upon entrance, smaller programs hint at the layout of the larger structure. However, it is not until attendess ascend to the inverted theater on the top floor that they truly understand how this building works.

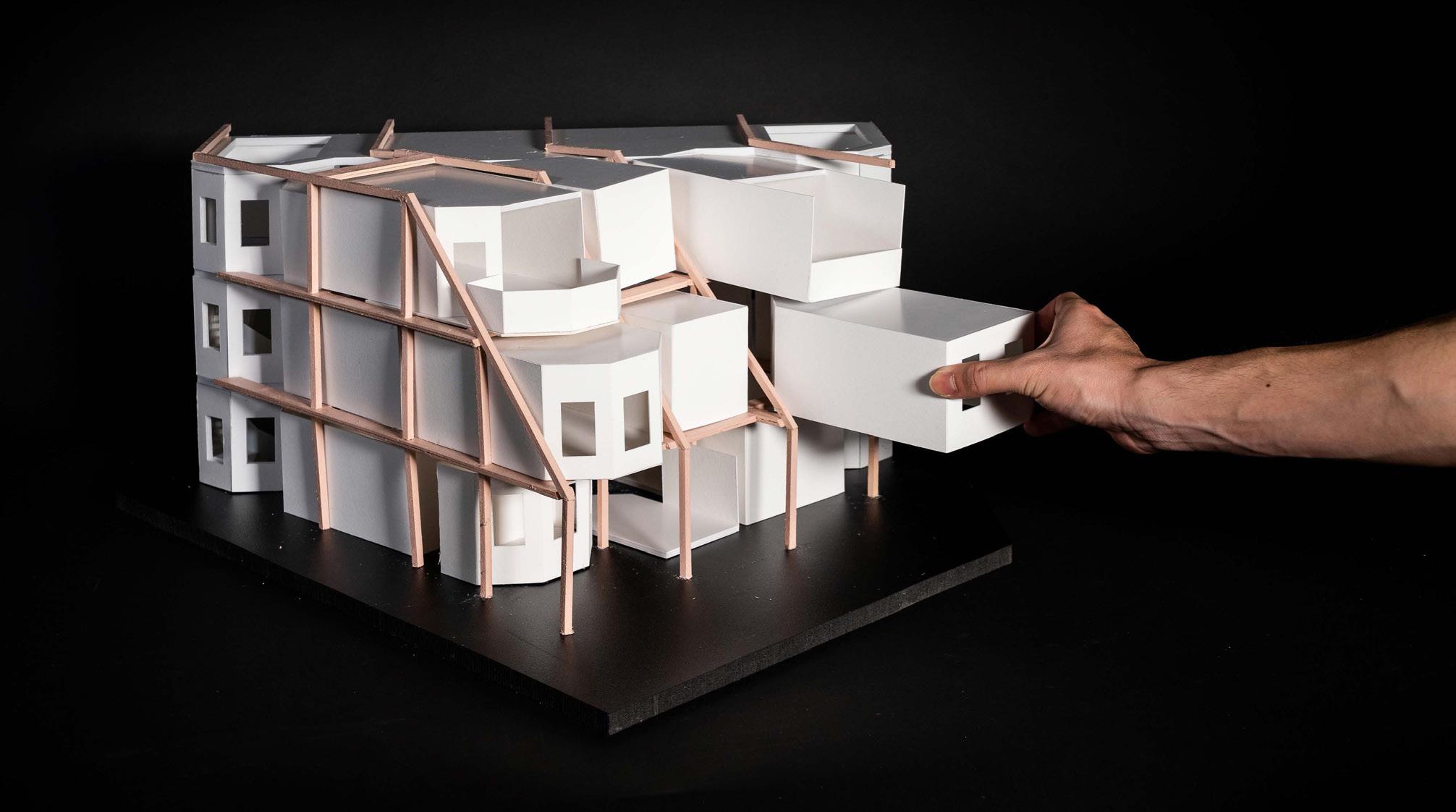

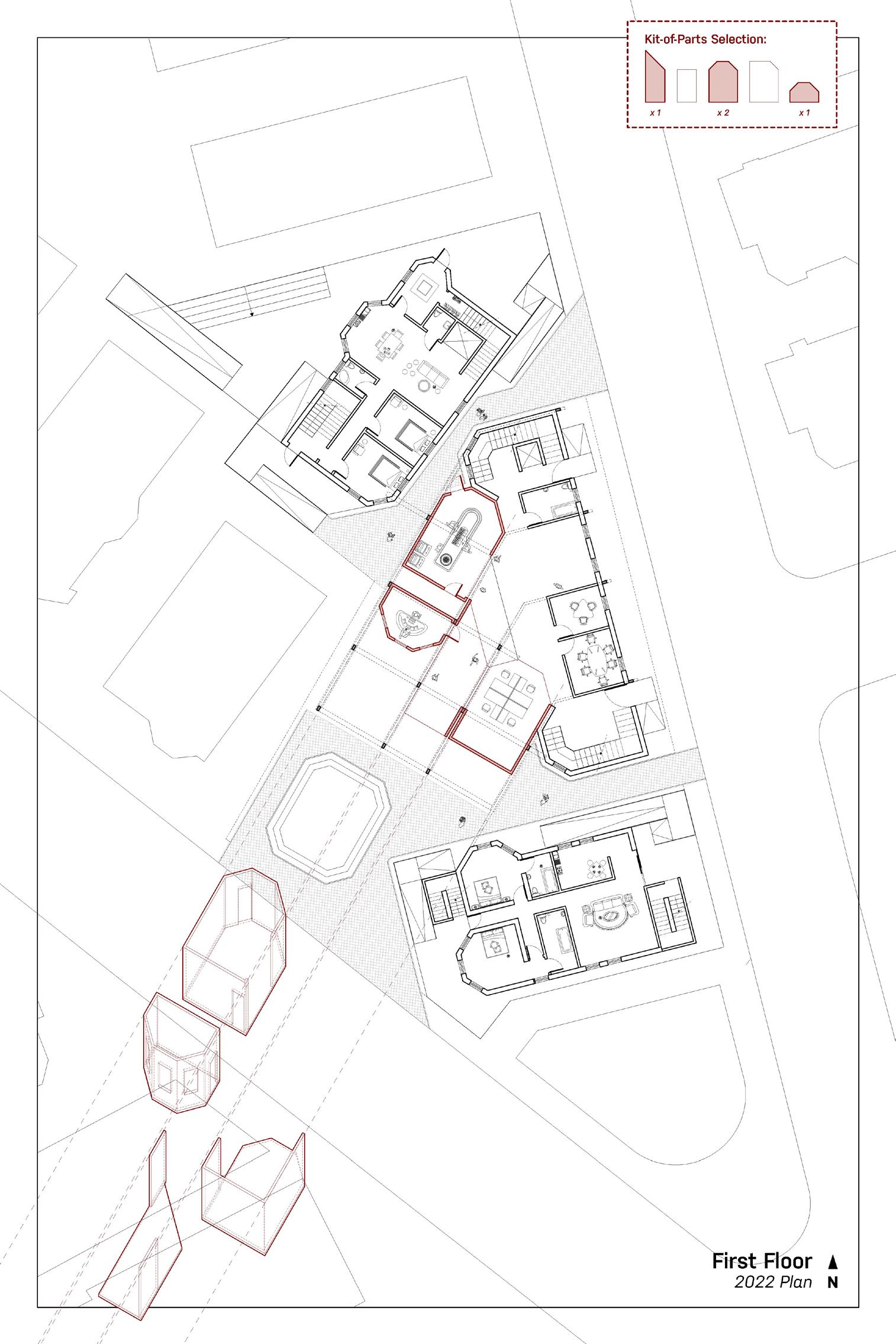

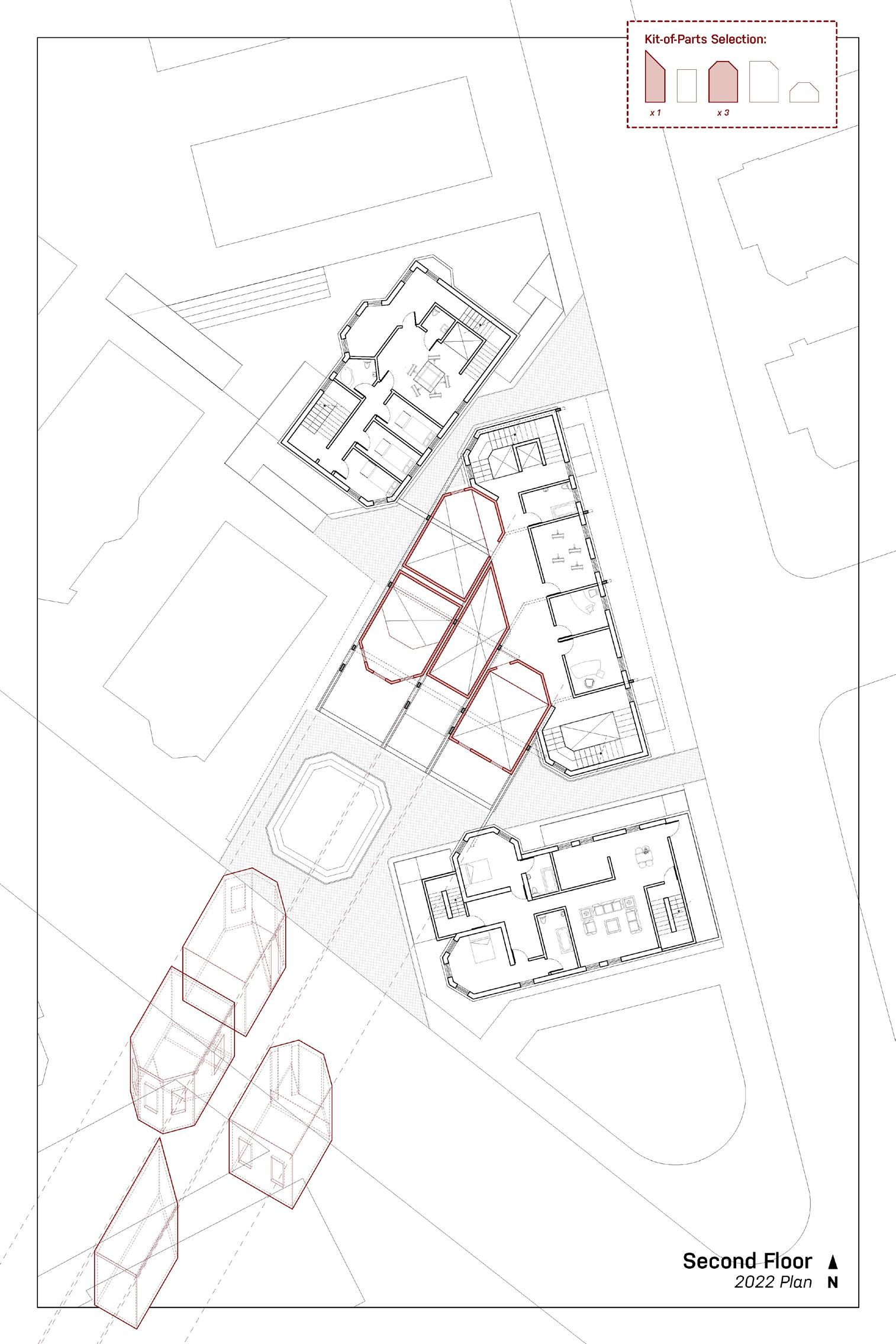

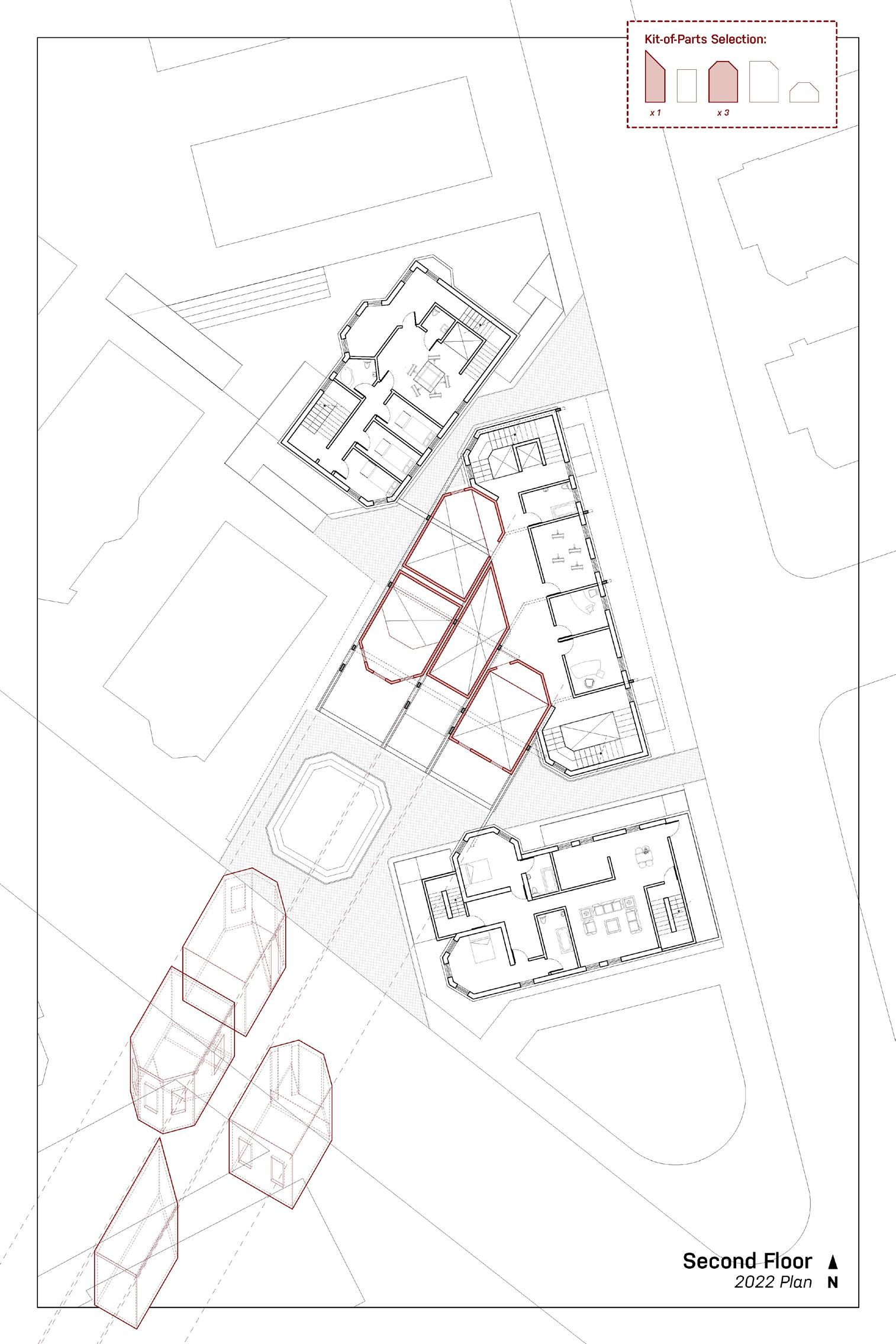

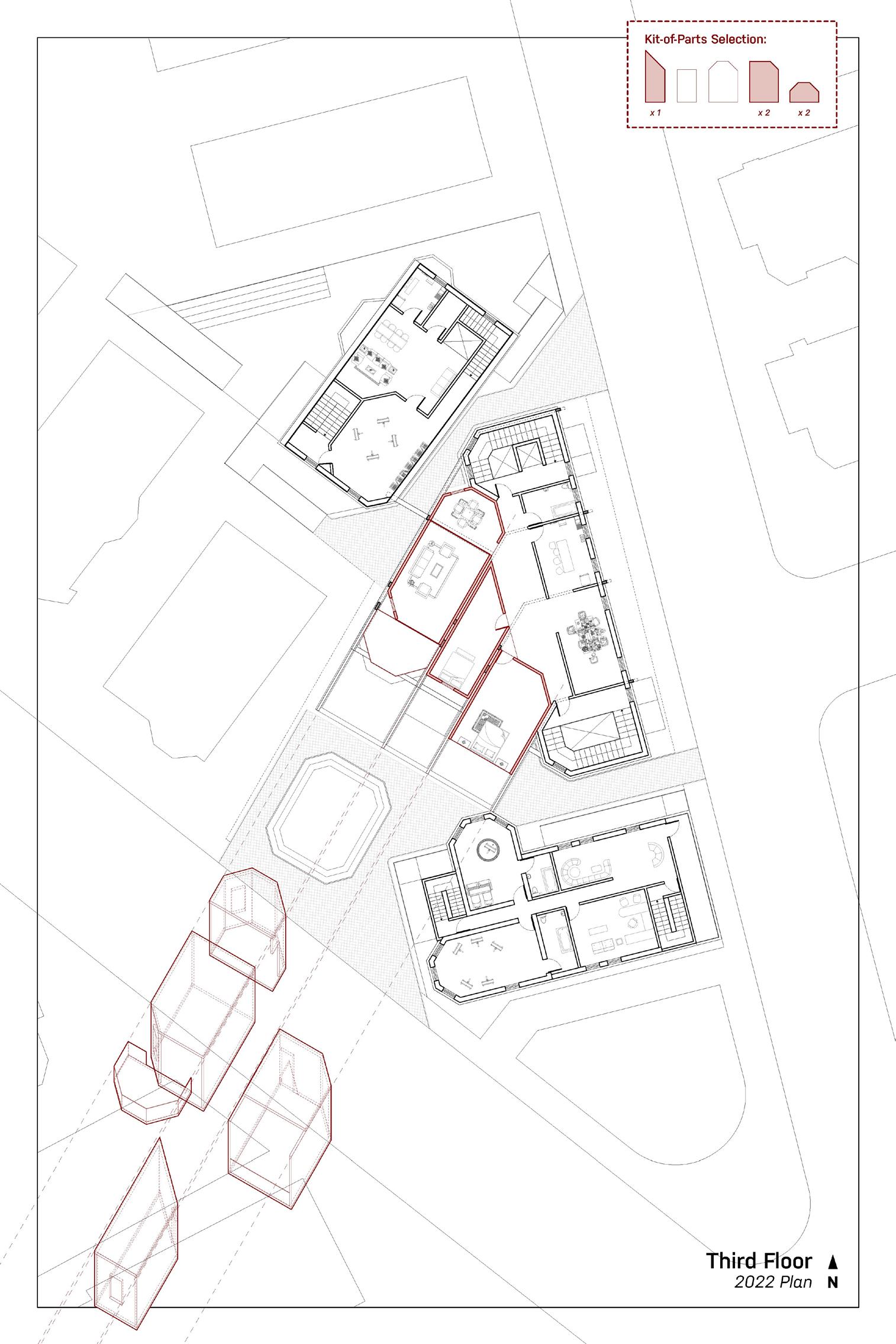

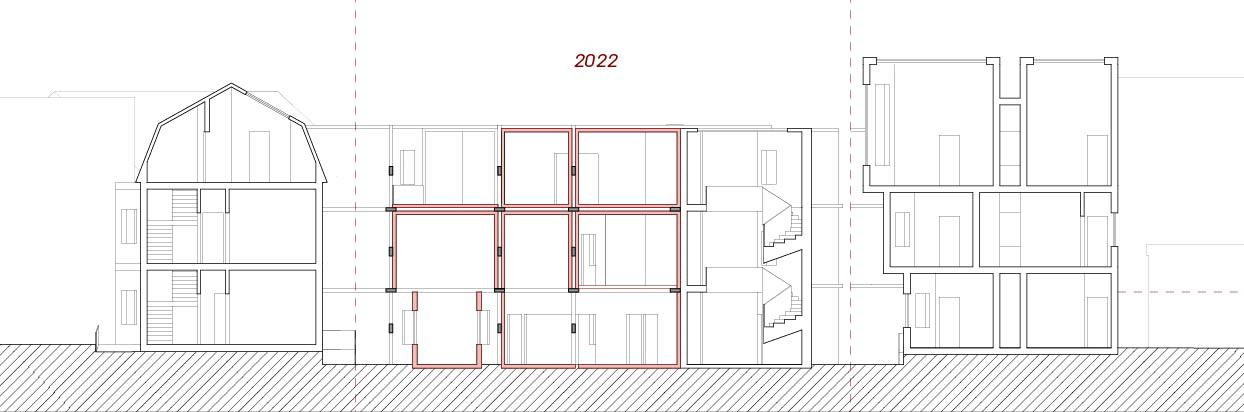

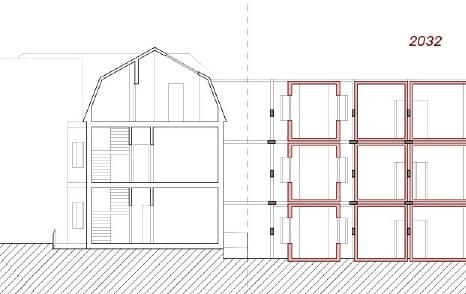

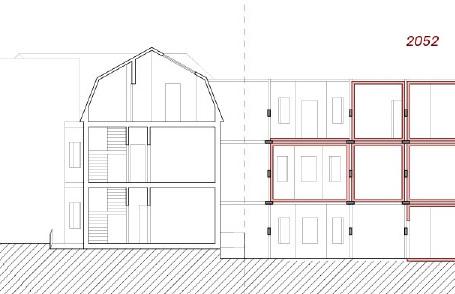

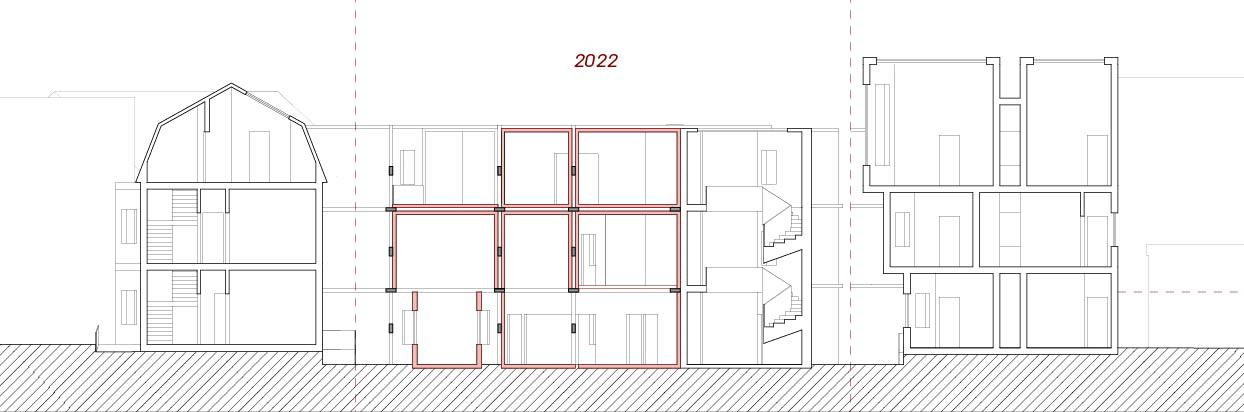

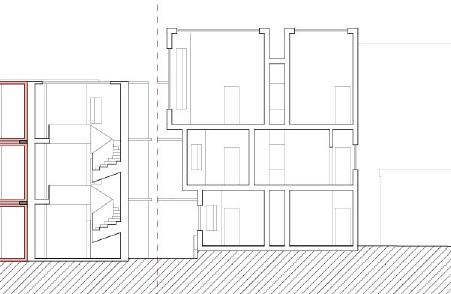

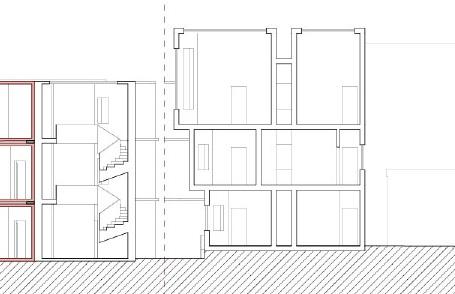

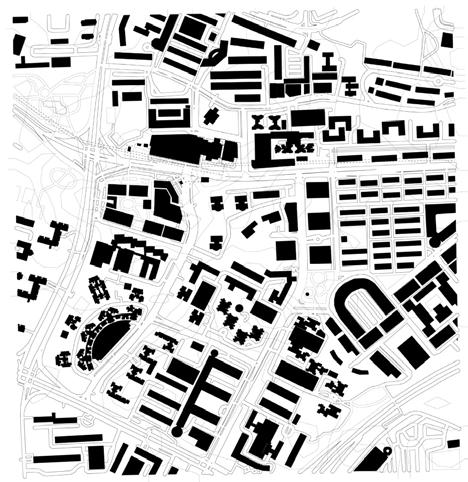

CORE I: ORDINARY, EXCEPT partners: keane chua and nana aba turkson instructor: helen han 2022

This project explored both the triple decker typology and a specific site in Dorchester, MA. The brief involved adding three triple deckers to the site to create a combination of artist residency and family housing within the existing neighborhood. To address this challenge, my team created a three act play, with each building serving as an act. The building to the left in the image below internalized the bay window form, the building to the right externalized it, and the central building used a modular kit of parts that can be added and removed to an anchored building in order to allow the structure to adapt to the needs of the community throughout time. Three proposed configurations were created for 2022, 2032, and 2052 as the central building transforms from residency to community exhibition space to community market and housing.

Personal Contributions: Sections, Models (pictured top and bottom right), Other Models (collaborative)