2021-2024

a

DESIGN STUDIO

Design Studio 3GB Vertical

Design Studio 3GA Vertical

Design Studio 2GB

Design Studio 2GA

Design Studio 1GB

Design Studio 1GA

Visual Studies Pleats Please

Visual Studies Grin

Visual Studies Wallpaper

Visual Studies III

Visual Studies II

Visual Studies I

Introduction to Autodesk Revit

Advanced Embodied Carbon

Advanced Project Delivery

Practice Environments

Design Development

Environmental Systems

Materials & Tectonics

History of the Commons

History of Architecture & Urbanism II

History of Architecture & Urbanism I

Intro to Contemporary Architecture

Statement

At SCI-Arc, my architectural endeavors are propelled by a commitment to fostering meaningful dialogue and addressing pertinent social and cultural inquiries. During the initial two years of my projects, my focus centered on materiality and the nuanced articulation of material behavior across various mediums, with a dedicated emphasis on the immersive 1:1 human experience. These projects compelled me to navigate the boundaries between distinct mediums—digital, drawing, and physical— and to contemplate the implications of this intersection on architecture, as the edges blurred across different modes of representation and scales.

While retaining my initial interests, I have recently broadened my perspective to examine the broader impacts that diverse materials and architectural processes have on the world, encompassing social, political, environmental, and economic dimensions. Looking ahead, my aspiration is to delve deeper into these thematic considerations, employing them as a conceptual lens to scrutinize material processes, social infrastructure, and the possibilities of adaptive reuse within architectural practice.

Kristen

Design Studio

Design Studio 3GB Vertical |

SPRING 2024

DAVID ESKENAZI

Architecture both leads and follows. It expresses culture and social groups while also shaping them. Buildings often aim to endure, preserving their values over time. However, some forms of architecture are temporary, such as event tents, pavilions, or movable huts, which may leave lasting impacts despite their short-lived nature. These temporary structures often accompany a moment or event, fostering new social groups that dissolve when the architecture is removed. This studio explores both permanent and temporary architecture, examining their potential social effects and how they can work together.

The studio project involves designing two side-byside buildings: a temporary event platform and a bathhouse. Using paper and 3D-printed models, we explore analogous materiality, emphasizing the relationship between the two structures and their material assemblies. Seven key studio propositions will guide the work, aimed at creating an architecture that fosters empathy in a new aesthetic and political context.

Provisional Everything: Embracing temporary assemblies, weak materials, and flexible systems that anticipate eventual dismantling and reuse. Experimentation with techniques like bundling, taping, stacking, and wrapping to create dynamic formal and social arrangements.

Queer and Modern: Starting from modernist principles like orthography and minimal aesthetics, we’ll explore queer aesthetics, asking if a

Something Permanent and Something Temporary

ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR

ADOBE PHOTOSHOP

subtle form of queer minimalism can operate in architecture.

Live Models: All models will be active participants, brought to life through live performances and videos that infuse humor, seduction, and emotion into the architectural process.

Appearing Twice (and Not): Exploration of the contrasts between temporary and permanent, flexible and rigid, singular and multiple, field and figure, through architectural doppelgangers and mirror-like inversions.

The House-Bath: Using the Hollywood Spa, a defunct gay men’s bathhouse, as a site, a proposal for a new form of bathhouse that blends public utility, community resources, and temporary housing, addressing the needs of the unhoused population and other subcultures.

Crude Images: Embracing quick, rough, and inexpensive aesthetics to describe texture, color, light, and material, using crude renderings to express how architecture organizes life.

Just Redo It: Instead of creating entirely new designs, remodeling, relocating, resurrecting existing forms, employing kit parts, architectural diagrams, and collective authorship to propose looser, more adaptable architecture.

Hollywood Sento

This project explores the interplay between temporary and permanent architectural elements through the lens of heat, humidity, steam, and comfort. Inspired by the concept of wrapping and cleansing, the design focuses on creating a flexible, movable bathhouse environment that balances rigidity with adaptability.

The midterm phase involves designing movable boxes that embody wrapping actions, where flaps lift and the ground plane shifts between wrapped and unwrapped states. This introduces a binary between stiff and flexible, appearing twice throughout the design. The final phase features a removable enclosure with panels that offer both visual and auditory privacy, creating a dynamic interplay between exposure and concealment.

The program is based on a Japanese Sento-style bathhouse, featuring multiple baths and pools, a sauna, a café, and an event space. The design will explore temperature changes and flexibility in the spatial organization, with the viewer able to look down into the pools, creating a dialogue between the viewed and the viewer.

The project also emphasizes the effects vs. performance, focusing on abstracted elements like heat packets and carpet wrapping. Videos document actions like wrapping, squishing, and even frustration with the models, bringing the physical processes and emotions into the design narrative.

14 WEEKS

3GB.DS.U Final Elevation Render. 3GB.DS.V Final Model: Detail.

3GB.DS.W Final Model: Detail.

3GB.DS.X *On following page* Final Model.

Design Studio 3GA Vertical | Competition x2

FALL 2023

JOHN ENRIGHT

ANDREA SANCHEZ MOCTEZUMA

This studio focuses on Architectural Competitions as a foundation for developing diverse architectural strategies across scale, location, and program. Engaging in two seven-week competitions, the studio explores the value and various approaches to architectural competitions, connecting work across both as related, progressive investigations. The two-part project breakdown offers flexibility for refining and redoing earlier versions of form, strategy, and approach. The studio challenges the pedagogical norm of a 15-week singular project semester.

The Architectural competition, with a history spanning 2,500 years, has produced iconic buildings like the Acropolis and Disney Concert Hall. While some criticize competitions as an abusive method that undermines thoughtful architect selection, potentially exploiting labor and raising concerns about professional relevance, it’s evident that architectural competitions are enduring. The Guggenheim Helsinki competition, with its 1,700 entries, underscores the enduring interest competitions generate.

However, the creative realm inherently involves competition. We constantly compete in various ways, acknowledging that our ideas, concepts, and work are naturally compared, debated, and ultimately judged against each other. Embracing the belief that healthy and fair competition is a positive pursuit, this studio approaches the two projects with this spirit.

Competition 1: Labyrinthe de Pensées

Competition 2: Mývatn Beer + Spa

Labyrinthe de Pensées | Maze of Thought

This proposal for the forecourt to the Natural History Museum of Paris proposes to create spaces of contemplation and respite, formed by both natural plants and human made materials, offering visitors a maze-like series of spaces to pause and consider our relationship between nature and architecture.

The Museum’s literature describes the Natural History Museum of Paris as “an active research institution studying the evolution of life on this planet and its occupants,” a place where tradition and innovation merge. The forecourt space becomes a physical manifestation of the intersection of this planet’s human and non-human organisms that exist on the grounds of this institution, the confluence of the study of humans, animals, and plants in the middle of a bustling urban environment. Thus, the themes of order and chaos and the delicate balance between nature and human intervention can be reasoned. This project

proposal explores those themes and introduces additional topics of contemplation through a maze-like assembly in that forecourt space. Mazes and labyrinths have existed throughout history for centuries, and while there are various intentions for their presence, they often share the goal of shifting perspectives.

The maze becomes a convergence of the known and the unknown, and the occupants must relinquish the orientation of both their bodies in space and their perspectives of the built world. The manipulation of vegetation and building materials into a maze-like structure, in both plan and section, alters the typical understanding of one’s surroundings. The maze typology is reoriented from a two-dimensional study into a three-dimensional spacemaking assembly. Additionally, the proposal seeks to spatially reorient the hedge typology. Regional typologies of spacemaking plants begin to fly

COMPETITION 1 7 WEEKS

overhead or stick out in ways that are not typical. The hedge and maze don’t exist if humans are not intervening. The proposal seeks to initiate the reconsideration of one’s relationship to a human intervention that is familiar; if the gardener doesn’t come to manicure the hedge, then the plant itself starts to break the boundary or intervention of the human to interject its internal logic. Furthermore, an inherent slowness within the maze and a removal from the frenetic pace of the city occurs. The chaotic urban environment recedes into the background, and the occupants’ relationship with the city is reconsidered.

Buildner

Mývatn Beer + Spa

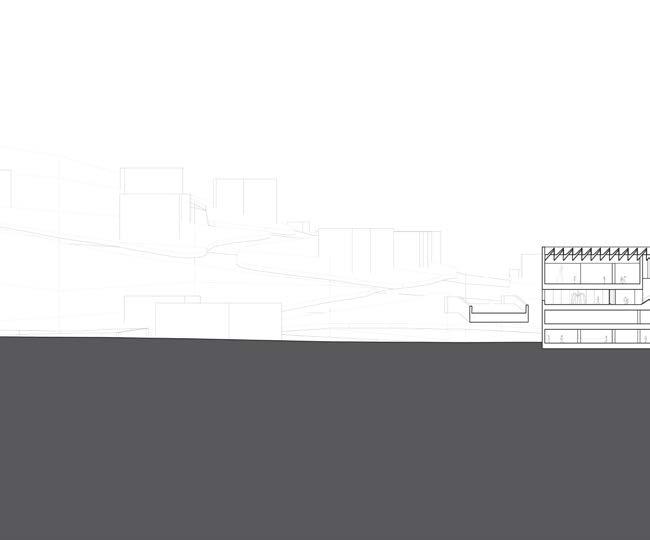

This proposal aims to seamlessly integrate the rich natural and cultural heritages of the captivating Mývatn region in Northern Iceland. To accomplish this, the project incorporates a double-glazed façade that simultaneously maximizes views of the surrounding landscape and creates a sustainable enclosure that moderates thermal heat loss and gain. The brewery equipment is arranged vertically and is celebrated as a focal point for visitors both from the interior and exterior.

Surrounded by the stark beauty of the lava fields and positioned to overlook the reflective expanse of Lake Mývatn, the site provides an exceptional canvas for the project. The presence of the Skútustaðagígar craters further enhances the narrative, serving as a testament to the earth’s power and history. The challenge is not merely to occupy this space but to become an integral part of the breathtaking panorama, striking a delicate equilibrium between the serene beauty of the environment and the functional demands of the brewery and spa.

Acknowledging the relatively recent embrace of beer culture in Iceland, the project pays homage to this cultural shift. The lifting of the ban on selling beer in 1989 became a pivotal point of inspiration in terms of the spatial organization of the brewery. The multi-level design allows for a gradual procession through the program, allowing visitors to traverse the various stages of the brewing process, each level offering a nuanced perspective on the artistry behind beermaking.

Visitors are immersed in an experience that extends beyond the architectural boundaries. Panoramic views of the surrounding landscape become an intrinsic part of the design, fostering a profound connection with nature. From the distinct geological formations at ground level to the ethereal dance of the Northern Lights in the night sky, the project invites guests to partake in the marvels of the Mývatn region. Additionally, outdoor spaces great for birdwatching provide an opportunity for guests to engage

COMPETITION 2 7 WEEKS

with the local fauna, appreciating the region’s diverse avian life.

The project’s success will be measured not only by its functionality but also by its ability to provide a platform for guests to immerse themselves in the unique cultural and natural tapestry of Northern Iceland. The project is envisioned not merely as a structure but as a dynamic participant in the narrative of the Mývatn region, the Sel Hotel, and its evolving cultural identity.

METAL ROOF

FERMENTATION TANK BRITE TANK

FINISH FLOOR

CONCRETE FLOOR TOPPER

CLT FLOOR ASSEMBLY

GLULAM BEAM

GLULAM COLUMN

BREW KETTLE WHIRLPOOL HOPBACK

ROTATING WOOD LOUVERS GRIST MILL MASH TUN LAUTER TUN

LOW-E GLASS CURTAIN WALL WITH LOW-CARBON ALUMINUM

Design Studio 2GB | Architecture as Urban Design

SPRING 2023

JOHN ENRIGHT

DAVID FREELAND

DARIN JOHNSTONE

MELISSA SHIN

LEILA KHODADAD

This studio explores the intricate relationship between architecture and the city, aiming to enhance students’ comprehension of how architecture can influence and be influenced by the urban context it engages with. Through thoroughly examining relevant examples and site research, the studio considers and applies models involving formal, infrastructural, and ecological approaches to the interaction between architecture and cities. Students are tasked with proposing designs for a significantly large, condensed urban campus project, emphasizing the importance of integrating their designs into existing urban conditions while understanding the dynamic interplay of economics, planning, ecology, politics, and infrastructure that have shaped the contemporary city. The studio contends that embracing bigness is crucial both in form and substance. Large buildings and generic urban structures can fulfill the need for new forms of urban density, leading to innovative architectural solutions. Rejecting urban agnosticism, very large architecture must now accommodate diverse programs and respond to the complex demands of the urban fabric and the city skyline. It is expected to be grounded yet aspire to reach the sky.

College of Design and Art (CDA)

Containers of Bigness

“The project narrative imagines a merger between a fictitious Mexico City University and a contemporary College of Design and Art to create a standalone school and campus ‘megabuilding’ situated within Mexico City. ... At approximately half a million gross square feet of area, the program consists of twenty art and design oriented academic programs with shared support spaces, including larger scale galleries, library and auditoria, as well as housing, administrative and support spaces.” - Studio Brief

This project, first and foremost, looks at the concept of bigness, particularly in relation to the vertical understanding of a campus. With this understanding, the project is inherently “big” in that it takes all the components of a horizontally oriented campus and re-orients them in a vertical container. Additionally, campuses can often be read as their own city that is situated within a larger city or context. The fragmentation, while a product of the formal operations of the design process, also looks at cities’ progression and dynamic nature. Pieces and parts

can be added or changed over time, much like how cities change and shift over time with the introduction of scalar or density shifts.

The pyramid remains at the “core” of the project, an unchanging volume holding all public programming.

The architecture embraces the idea of time and change while simultaneously rejecting it by concealing the fragmentation with a veil, with openings appearing to re-engage the context at key points.

This project also seeks to challenge traditional expectations of materials and space by way of the cube/ pyramid, sky/ground false dialectic. In doing so, there is an exploration of unexpected inversions of mass and void which involve challenging normal material expectations. Glass appears massive and mass appears as if it is floating. In dialogue with this, the project is

14 WEEKS

situated within Venturi’s notion that a building can be more than one thing at once; looking at creating perceptual shifts and alterations of “reality.” In doing so, pyramids become skies on the ground, cubes become grounds in the sky, and they exist simultaneously.

2GB.DS.I Program Diagram: Program diagram from midterm showing basic programmatic understanding. *Note: some program arrangements did change*

2GB.DS.J Level 7 Plan: Floor plan of level 7 depicting academic programming in a ring typology.

FLOOR 7 // RING

2GB.DS.O Worm’s Eye Axonometric.

2GB.DS.P North Elevation.

2GB.DS.Q South Elevation.

Design Studio 2GA

FALL 2022

MARCELO SPINA

RUSSELL THOMSEN

PETER TRUMMER

DEVYN WEISER

PAIGE DAVIDSON

JULIA MCCONNELL

JAMES PICCONE

The second-year core M.Arch I sequence commences with a focus on enhancing students’ understanding of the discipline and knowledge of architectural production. The studio emphasizes the development of projects in accordance with Integrative Design principles. It is structured to elevate awareness of the intricacies of designing sophisticated architectural projects. Fundamental spatial structures and organizational systems are seen as outcomes shaped by various factors such as site conditions, program distribution, structural systems, building envelope systems, environmental elements, and building regulations. These influences are recognized as both physical and virtual, enduring and transient, situational and circumstantial. The studio encourages the exploration of site-related qualities, contextual situations, environmental factors, and cultural contexts as potential tools to challenge conventional approaches to architectural design.

The 2GA studio in architecture aims for a radical re-engagement with the ground, considering both literal and conceptual aspects. It delves into the disciplinary, professional, environmental, and social dimensions of architecture. Focused on the theme “Architecture Culture: New Museums for Social Change,” the studio explores the historical significance of museums as

RHINO

ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR

ADOBE PHOTOSHOP

CINEMA 4D OCTANE

contributors to architectural and cultural value globally, citing the transformative “Bilbao Effect” of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum. In the context of current social, environmental, and cultural challenges, the studio addresses the evolving expectations for art production and cultural identity. It examines the role of museums in making cultural, artistic, and political impacts without compromising their missions. The studio poses questions about the role of architecture in museums, emphasizing its potential as an active agent for social change and its role in creating sustainable cultural identities for institutions and cities.

Exploration of challenges related to progress, exclusion, gentrification, and the interplay between architecture and institutional identity is integral. The studio grapples with how architecture can navigate its engagement with images in a culture concentrated on aesthetics. Additionally, it questions the alignment of a museum’s constructed identity with that of the art and artists, shaping the cultural mission of contemporary institutions. The studio encourages projects to present well-informed arguments, offering intelligent, relevant, albeit provisional, and speculative responses to the intricate questions facing contemporary architecture.

MASS MoCA

The Gap: A Split Kunsthalle

Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, USA

Program: Art Gallery, Blackbox Theatre, Artist Studios, Cafe

Size: 154,070.06 sq. ft.

Height: Approx. 82 ft.

In 2017, MASS MoCA (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art) achieved the status of being the largest museum for contemporary art globally, a remarkable transformation considering that just thirty years earlier, its expansive brick buildings were abandoned remnants of a closed factory. The Studio proposes using MASSMoCA as a conceptual ground to envision a large, urban, and transformative adaptive-reuse project for North Adams, a small-town exemplar of white-collar Rural America situated in the Berkshires region of Northeastern Massachusetts.

Currently encompassing 19 buildings, 12 of which are converted into exhibition spaces, artist studios, and workshops, MASS MoCA spans 1 million

square feet and includes both indoor galleries suitable for large art installations and outdoor areas with a river, bridges, and remnants of machinery. Despite its ambitious scale and drawing 160,000 visitors annually, MASS MoCA considers itself an integral part of the community, aiming to impact the community and economy in a complex, mutually beneficial way.

The Gap: A Split Kunsthalle is an addition to the MASS MoCA campus in North Adams, MA.

The project centers on the programmatic conditions of a kunsthalle or “art shed,” which is a noncollecting institution that presents art on loan from other institutions or individuals. Reengaging the local community is a key driver for the project and is reflected in the programmatic additions beyond just an art gallery. Additionally, the

IN COLLABORATION WITH INDIA CHAND

introduction of a “split” or “gap” creates flexible community programming in the center of the building that allows patrons to experience MASS MoCA from a new perspective.

The building form starts from the basic museum typology of the box and works to create a porous perimeter without destroying the iconography of that box. The split elevates the art gallery above the raised highway and allows for open community space below that is visually linked to the horizon of the city.

The goal of the material choices is to be visually linked to the context while utilizing more carbon friendly options. This is achieved through color and textural choices that relate to the primary use of brick in the city and on the MASS MoCA campus directly.

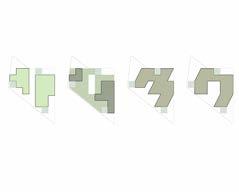

2GA.DS.E Diagram: Plan diagram showing formal moves using a puzzle based on the studio brief.

2GA.DS.F Final Model: Image showing final model split in two, demonstrating the diagram has been maintained.

TYPICAL KUNSTHALLE

Design Studio 1GB

SPRING 2022

MATTHEW AU

DAVID FREELAND

ANNA NEIMARK

ANDREW ZAGO

KAITA SAITO

This design studio continues to build upon fundamental architectural representation techniques. With an emphasis on interiority, typology, program, circulation, and landscape, this studio explores the development of a multiprogrammed municipal building in Van Nuys, a Los Angeles, California suburb. The studio introduces the complexities of community, equity, and sustainability and the cultural and ecological concerns those bring. The studio is broken up into areas of focus; those being site & context, building & ground, program & circulation, and finally material & detail. The site & context portion of the studio is implemented as a larger group with the remaining areas being individual. This studio is completed under specific direction from two faculty members: a main instructor, and an assistant teacher.

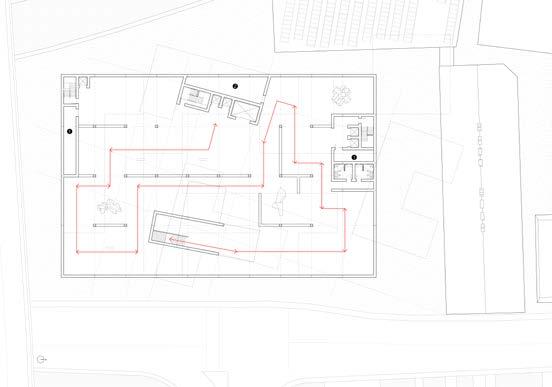

Van Nuys Municipal Building

Comprised of the Van Nuys branch Registrar-Recorder, County Clerk, LA Public Library, and a Civic Child and Development Care Center, this building negotiates the complexities of a collection of programs that have vastly different organizational requirements in terms of access and circulation. The organization of public and private spaces is essential for the security of the wide range of occupants. Documentation becomes a major theme in the articulation and understanding of the project both for the building and the landscape. The municipal building where documents are stored is the starting point for the project. These buildings are a remnant of a 20th-century way of life, where most of our lives have now transitioned to digital formats. The design of these office buildings throughout history is representative of civic life and citizen participation, however, there became a turning point where offices have failed to evoke a sense of civic pride. The planning of these buildings is purely functional. The goal of this project is to bring the public back into the building. Two strong organizational aspects of this project have to do with

a courtyard and ramping floor plates. This project includes a central courtyard surrounded by two different intertwining ramping systems. Each floorplate is comprised of two parts: the programmed occupied floorplates, that fold up to form walls, placed on top of the corrugated system. The corrugated floorplates are accessible but not programmed and they extend to the boundary of the building site. This intertwining of two ramping systems offers areas where the inner and outer programs can interact and areas where they are separate. The library and archive are placed in the center ramping system and the placement is informed by the article: The Power of the Archive and its Limits by Achille Mbembe. The center placement of the library and archive allow the complete access of it to all programs to bring knowledge and information to the people. The occupiable floorplates, slightly offset from floor to floor also relate to the notion

14 WEEKS

of transparency of knowledge. Material articulation is also a key aspect of the project. The corrugated floorplates are a strong identifying feature. The corrugation evolved from a diagrammatic articulation of the courtyard pushing into the building, the public pushing into the private. It also relates to the ornamentation of municipal buildings in history. On one side of the site sits a 20thcentury municipal building and on the other a 21st-century parking structure. This project seeks to merge the macro and micro scales of each, and the articulation of corrugation allows the building to move in that direction. The corrugation moves to the landscape at a different scale and merges with native California foliage.

1GB.DS.C Generic Courtyard

Diagram. 1GB.DS.D Courtyard

Diagrams: Diagrams of courtyard case study buildings showing the courtyard as mass that pushes into the buildings openings in a Rachel Whiteread-esq way (Done in collaboration with Sukanya Mukherjee).

CONSTITUENT

LA POLICE DEPARTMENT

1GB.DS.S

1GB.DS.T Final Model: Depicting building model with roof placed on plaster landscape model with both placed in milled high-density foam site model (Site model was a class collaboration).

1GB.DS.U Process Photo: Final model pieces; copper 3D print.

1GB.DS.V Process Photo: Final model pieces; black paper.

1GB.DS.W Final Model:

Depicting building model with roof placed on plaster landscape model with both placed in milled high-density foam site model (Site model was a class collaboration).

1GB.DS.X Section.

Design Studio 1GA

FALL 2021

MATTHEW AU

KRISTY BALLIET

JENNIFER CHEN

DAVID ESKENAZI

This design studio is broken into three projects that have an intention to develop a foundation for a visual language that is to the standard of SCI-Arc and can become uniquely individual. This is achieved through the practice of drawing, rendering, and modeling. The three projects are completed in succession and focus on the same main themes. The first project is completed with direction from all faculty members. The second and third projects are completed with main direction from one faculty member with additional feedback provided by the remaining faculty members. The final project is a culmination of the themes of the studio into a building design.

Project 1: The Line

Project 2: A Figure

Project 3: The Building

The Line

Project 1 focuses on the notion of a line as an introduction to form and space. The project is formed from a series of phases: Survey & Construct, Transformation, Edit, and finally, Grain & Scale. The project begins with surveying the regulating geometry of the Santa Fe Freight Depot, the shell of which SCI-Arc currently lives, and moves into how the concrete shell can be read like an outline. That idea is used to confront ideas of volume and thickness. The result is an abstraction of SCI-Arc through a series of drawings and a model of a single continuous line. Looking at how the line can be reconfigured and how it confronts constraints becomes important in the development of the project. The length of the line, the bounding box given, and the strategies developed individually for corner conditions all become constraints that determine the outcome of the project. The line folds within the edges of the bounding box and leads to the formation of strategies for how to articulate each of the folded corner

conditions. Material transition and the dialogue between grain and the line follow; choosing to project, challenge, or follow. The folding strategies become an identifying quality of the project with the goal that in one elevation the project reads in one way, the line extending to the bounding box in two directions, and then in a second elevation, it reads in another way, the line meeting the extents of the box in just one direction. The resulting line then displays two different readings of the same line: Compression and Extension. The subtlety of the grain is another identifying quality and the articulation of that grain at the corners is important. The project negotiates what happens when two different grain directions meet, when one overrules the other.

Model Misbehavior

Project 2 focuses on the development of a figure and how a model of architecture engages material forms. The terms real, stand-ins, abstractions, and simulations are driving concepts that lead to the idea of the simulation of material and the relationship between geometry and material. The project starts with a compilation of various sheet materials. Physical tests, digital models, and physical simulations are conducted on these sheet materials. The goal of which relates to the idea of slippery connections between mediums to construct new forms. Clarity and ambiguity become strong themes within the project. Part one of the project shows the documentation of the sheet materials using strip shapes, props, photographs, and tracings. Part two yields a compiled composition of a combination of material properties, by combining single figures made of single parts that intersect. Digitally modeled papers and intersections of pieces are products of this part. Part three looks at projective

interiority in relation to three types: a fully enclosed interior, an implied interior, and an interior within another interior. This creates a variety of spatial qualities and formal properties. Scaling, grain, hollowing, and posture become additionally important at this stage of the project. The model and ideas from this project directly translate to a building in the final project.

Single-faced corrugated cardboard is the main characteristic material quality of this project. The articulation of the cardboard in the first stage of the project determines the direction of the formation of the figure. The project is looking at how corrugation can be represented at different scales and in different mediums and how those representations can move between realms to create clarity and ambiguity.

PROJECT 2: A FIGURE 3 WEEKS

1GA.DS.2.C Sheet Material

Documentation: Photograph, tracing, digital model. Showing the effects of gravity on open face corrugated cardboard at two different scales and with three different strip shape variations

1GA.DS.2.D Strip Shape Composition 1. 1GA.DS.2.E Strip Shape Composition 2.

1GA.DS.2.F Plan: Drawing showing Model Misbehavior figure with grain articulation and projective interiority. 1GA.DS.2.G Elevation: Drawing of Model Misbehavior figure showing grain articulation, posture, and projective interiority. 1GA.DS.2.H 90° Elevation

Oblique: Model Misbehavior elevational render depicting posture and figure. 1GA.DS.2.I Compiled Composition 1: Rendered image showing Strip Shape Composition 1 with a digitally modeled corrugated cardboard.

Midterm Model: Photograph of Model Misbehavior paper model displaying scale, grain, projective interiority, projective three dimensionality, posture, and color. 1GA.DS.2.K Compiled Composition 1: Photograph of Strip Shape Composition 1 paper model with original sheet material open face corrugated cardboard. 1GA.DS.2.L Compiled Composition 2: Photograph of Strip Shape Composition 2 paper model with abstracted cardboard articulated through surface grain.

Boys and Girls Club of Metro Los Angeles

Project 3 deals with the formation of a building. It asks the question: How do we gather? The goal of the building is to serve a dual purpose of a point of engagement/education and of community gathering. The project explores ideas of cultural, social, and political aspects of the city of Los Angeles; pushing the idea that a building can act as an agent for inclusion. The project focuses on the negotiation of inside and outside taking into consideration the organization of thresholds, circulation, and occupation. The building serves as a location for the Boys and Girls Club of Metro Los Angeles which is a privately funded organization that works in conjunction with schools and neighborhoods to provide afterschool and summer programs. The building is approximately 15,000 square feet located on a 50,000 square foot site in the Venice area of Los Angeles, California. 2/3 of the building program fits within 2 large volumes and 1/3 fits within small and medium support

areas, developed through the idea of poche. The project also negotiates the conflict in having a secure facility for children with the programmatic areas that deal with a larger community population. Security becomes a driving factor in the organization of the program.

This project takes the figure from Project 2 and adapts it to a building by rotating it, editing it by removing or altering volumes, and negotiating its relationship to the ground. The removal of one of the three volumes from the figure becomes essential to the formation of the figure into a functional building. The articulation of varying degrees of enclosure creates a project with depth and interesting light and spatial qualities. Volumetric variety is also a key aspect of the project that can be seen in the final section model of the building. Continuing from Project 2, the material representation of the corrugated cardboard informs the material and spatial qualities of the project.

PROJECT 3: THE BUILDING 6.5 WEEKS

For a broad spatial understanding in terms of the program:

1/3: Service (amenities and services that support the club and community)

1/3: Academic (providing classrooms and learning resources)

1/3: Recreation (providing health and recreation

Exterior Render.

Final Model: Detail photograph of final section model showing light and shadow conditions within interior volumes. 1GA.DS.3.J Final Model: Perspective photograph showing building overhang and grid facade. 1GA.DS.3.K Final Model: Detail photograph. 1GA.DS.3.L Final Model: Detail photograph showing exterior surface grain, and perforated paper facade.

Visual Studies

Visual Studies Pleats Please

SUMMER 2024

DAVID ESKENAZI

Issey Miyake pleats a T-shirt. Frank Gehry corrugates a Dutch-colonial house. Ed Ruscha paints a ribbon. Each act represents a radically new interpretation of what’s possible in a discipline through unconventional material manipulation. This course builds on such innovations by exploring techniques that stiffen or relax geometric and formal constructs. Over the semester, lectures and readings will analyze historical case studies alongside contemporary examples in fashion, architecture, and art. We will examine commercial applications like pleating techniques and tent construction to uncover parallels between reinforcing weak materials and softening rigid geometries.

An expanded toolkit will introduce both digital and physical techniques, from simulated pleating to 3D-printed fabrics. Rhino and CLO3D will be the main digital tools for geometric development, material simulation, and rendering. Additionally, drawings and video simulations will test each assembly.

Pleats

Beginning with the research and design of simple pleats and progressing to complex pleats, these projects examine the simplicity of pleating and its impact on the material behavior of paper. The final phase explores the concept of “poor modeling” in relation to a strong architectural figure: the pyramid. The pyramid, a form known for its heavy base and lightweight apex, is reimagined through the use of weak materials and stiffening techniques like pleating and corrugating. The goal is to challenge the conventional weight-to-sky relationship by reconstructing the pyramid using non-traditional materials.

The final project focuses on two key approaches: Material Pleats and Assembled Pleats. We’ll expand the material palette to include 3D-printed fabric and pleated unconventional materials. The project will culminate in a collection of models, drawings, and renderings that reflect these explorations.

Two specific strategies are explored: the Hide Strategy and the Fold-up Strategy. The Hide Strategy draws inspiration from the concept of separating skin from flesh, using rigid body forms to differentiate geometry from materiality, referencing Jason Payne’s Rawhide and Piet Blom’s Kubuswoningen. The Fold-up Strategy employs minimal pleating to create drooping effects and uses overlapping techniques to increase rigidity, referencing Craig Green’s CG Scuba Stan and First Office’s Josephine, Strawberry, and Wilson.

12 WEEKS

IN COLLABORATION WITH SEVAG

VS.PP.I Flexible TPU 3D printed ‘fabric’ and ‘rigid’ solid bodies.

VS.PP.J Hide Model: Flexible TPU 3D printed ‘fabric’ and ‘rigid’ solid bodies arranged in a pyramidal form. VS.PP.K Complex Pleat Pattern 02.

VS.PP.L Flexible TPU 3D printed ‘fabric’ and ‘rigid’ solid bodies. VS.PP.M CLO3D Simulation: Scan the QR code to watch. VS.PP.N CLO3D Render: Hide Pyramid. VS.PP.O Hide Model.

Visual Studies Grin

SPRING 2024

WILLIAM VIRGIL

This course delves into the evolving role of grillz in expressing the complex layers of the Black American experience, drawing on the themes of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask.” Grillz are explored not just as fashion items but as symbols of identity, resilience, and resistance to societal expectations. The seminar traces the history of grillz, from their ancient origins to their influence on modern urban and hip-hop culture, highlighting their role in navigating themes of visibility, concealment, and cultural expression, much like the dualities present in Dunbar’s work.

Students will engage with zBrush design, gaining hands-on experience in creating grillz while reflecting on the social, economic, and racial narratives these objects embody. The course emphasizes the connection between art, identity, and societal commentary, prompting critical discussions about the deeper meanings behind grillz. Final projects will not only demonstrate technical skills but also reveal an understanding of how these symbolic accessories tell intricate stories of struggle, identity, and defiance—mirroring the powerful metaphor of the mask in Dunbar’s poetry.

Grillz

The first project focuses on learning the basic techniques and workflow of the software. Using simple sculpting moves, we create an elegant design with flowing curves. This project emphasizes gaining control over zBrush’s tools while allowing space for creative expression through smooth, organic forms. It’s a chance to get comfortable with the software while exploring clean, fluid design concepts.

We selected a U.S. President (George W. Bush) from a provided list and received a 3D model of that president’s head, split between the facial half and the skull. Drawing on the lectures and discussions from the class, we conducted research on a significant event (Hurricane Katrina) from the president’s tenure, focusing on issues related to sex, race, identity, or gender. This event serves as the inspiration for a Grill design that encapsulates the essence of the story or historical moment.

The Contrast Between Appearances and Reality:

Hurricane Katrina, one of the deadliest and most destructive hurricanes in U.S. history, disproportionately affected African American communities in New Orleans and other Gulf Coast areas. The slow and inadequate response led to widespread criticism of the Bush administration and undermined public trust in government institutions, sparking debates about systemic racism and social inequality in America.

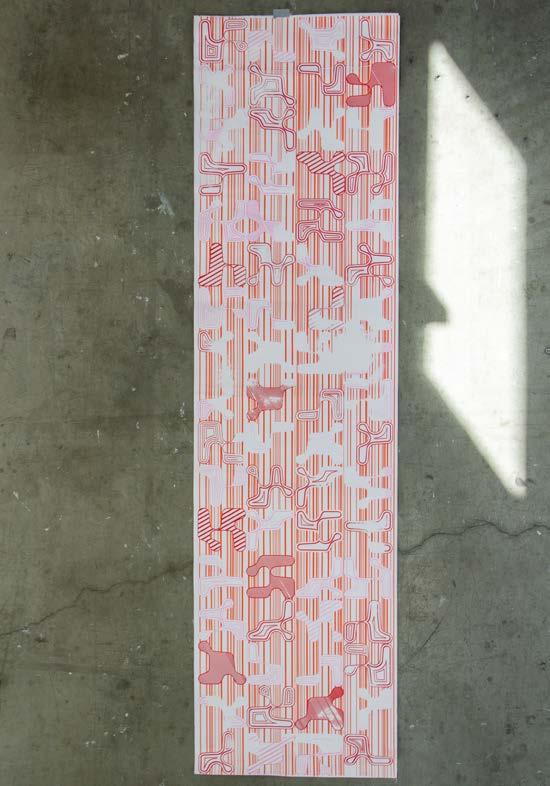

Visual Studies Wallpaper

SPRING 2023

FLORENCIA PITA

This course will center around the concept of Wallpaper as a landscape setting, a form of drawing, and patterns that mimic nature. The initial phase involves examining forms and translating them into drawings. These drawings will then be converted into outlines, which will be redrawn using a CNC milling machine equipped with a Sharpie marker, resulting in a wallpaper outlined with Sharpie lines. In the latter part of the semester, students will progress by developing their drawings further, transforming the lines into surfaces.

In parallel to traditional plaster wall moldings, the class will explore ornamental features, utilizing CNC milling to create plaster decorations that can be applied to the wallpaper. Examining both 2D and 3D geometries, the course delves into the concepts of ornamentation and nature.

The students will approach the work conceptually, initially working with abstract diagrams defined by procedural steps and later evolving to define their own drawing strategies. The creative process will always commence with a referent that establishes core ideas, leading to the development of drawings, diagrams, and material studies that define the conceptual path.

ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR

A key focus of the course is on the idea of abstraction and the potential for abstract diagrams and drawings to manifest as material effects. The central question driving the class is: How can a drawing transform into a material? All explorations and case studies revolve around the fundamental notion that material is not fixed but can always be recreated and reinvented. The objective is to invent a new material that is flat, artificial, and colorful.

Lucky Strike

Informed by Armin Hofmann’s Graphic Design Manual and drawing inspiration from the Paneled Rooms of the Art Nouveau movement, our project unfolds through a dynamic exploration of drawings, diagrams, and patterns. This creative journey commences with the creation of drawings, which serve as a foundation for analyzing textured materiality. Transitioning from the digital realm to the physical, we employ a CNC milling machine equipped with a marker, seamlessly merging the graphic and material realms and giving rise to captivating surface effects.

Building on the concepts of surface effects and embracing imperfections, we extend our exploration to the development of ornaments. These ornaments transcend the boundaries between the digital and physical worlds, blurring the lines between precision and imprecision. Throughout this process, we wholeheartedly embrace the imperfections as an integral part

of our creative journey. Color and textural variation emerge as significant outcomes of this exploration, influenced not only by the process itself but also within the broader context of the history of graphic design and wallpaper design. This project celebrates the interplay of imperfections, offering a nuanced perspective on the rich tapestry of color and texture resulting from the creative process. In doing so, we honor the legacy of graphic design while contributing to the ongoing dialogue in the realm of contemporary design.

14 WEEKS

IN COLLABORATION WITH

Visual Studies III

FALL 2022

MARCELO SPINA JAMES PICCONE

Visual Studies III offers an overview of modeling, advanced projection, composite drawing, and photorealistic rendering techniques. The seminar is designed to align with the representational narrative and analytical discourse of the 2GA Design Studio.

The course aims to familiarize students with methods of comprehending, representing, analyzing, dissecting, and transforming architectural entities, including buildings and projects, within a cultural context. It seeks to equip students with both a rigorous and disciplinary approach to analyze and understand significant architectural projects, as well as the technical, projective, and speculative resources needed to utilize them as foundations for the creation of contemporary and culturally relevant work.

Through a series of interconnected exercises, students will engage in researching, modeling, analyzing, dissecting, projecting, and transforming existing architectural precedents. The objective is to generate new objects that, while retaining a vague resemblance to the original, incorporate novel formal features and aesthetic attributes. This process encourages the creation of newly constructed objects that are simultaneously familiar and strange.

Textured Objects in the Virtual Realm

Precedent: Kadokawa Museum

by Kengo Kuma

This project revolves around harnessing the artistic potential of photography as a catalyst for inspiration. The construction of fictional narratives through the unique lens of architecture is a central challenge. By leveraging rendering and texture-mapping techniques drawn from original precedent sources, the creation and speculation of new composite objects are undertaken. These objects are carefully crafted to embody a dual nature— simultaneously oblique and photorealistic, abstract, and entirely real. The creative process serves as a testament to the harmonious convergence of imaginative storytelling and architectural visualization. Expanding upon the groundwork laid in the initial project, a venture into the realm of animated storytelling is undertaken, exploring the intricate material connections between architecture, space, and time within fictional environments. The focal point is the entanglement and infusion

of elements from reality into models situated on new sites, where the very ground beneath them is perceived as provisional and contingent. Throughout this exploration, the integration of atmospheric effects and nuanced lighting conditions aims to conjure an alternative yet entirely plausible world, enriching the narrative tapestry woven throughout the exploration.

14 WEEKS

IN COLLABORATION WITH INDIA CHAND

Visual Studies II

SPRING 2022

MATTHEW AU ZEINA KOREITEM

This seminar course expands upon knowledge attained in Visual Studies I that deals with architectural representation techniques specifically relating to projected line traditions of plans, elevations, etc. The projects in this course, rather than working with vectors and lines, deal with images and surfaces. The discussion of the difference between two forms of architectural representation that connect architecture to culture becomes important: by looking at documentary and experimental modes of articulation. Recording, tracing, remeshing, and building (digitally and physically) are major themes of this course in addition to representational methods of disruption like the manipulation of computational color image structures. As a supplemental portion of this course, the portfolio development section becomes essential to the progression of the degree program. The portfolio portion introduces the culture of publishing and printing in architecture. It offers exposure to visual trends within architecture and design in general. Additionally, the portfolio focus offers a chance to develop an understanding of fundamental graphic concepts and techniques for effective visual communication.

Kitchen Experiments

This project is a compilation of images, drawings, and models that deal with the notion of recipes. Recipes and receipts were interchangeable terms in the 15th century placing recipes as a source of value. They act as evidence, a record, or a document. They organize, transfer, and index information. The main themes within the project are recipes & records, precision & fidelity, and accidents & errors. The project looks at the idea of precision within making, degrees of replicability, and to what extent information is lost in the process. Starting from a documented Cuneiform tablet, various abstractions and replications are enacted. What results is a combination of images that represent the movement between digital and physical articulation. What information is lost or gained from the constant remaking of an image?

VS.2.H RGB Color Remapping 1. VS.2.I RGB Color Remapping 2. VS.2.J Color Remapping 3.

Visual Studies I

FALL 2021

MATTHEW AU KRISTY BALLIET

This seminar course focuses on developing a graphic and visual language through drawing and digital & physical modeling. The projects work on formulating a skillset to utilize in other courses and projects. The first project for this course is the same as the first 1GA Design Studio project. The second and third projects are joined together working with the same theme but with each displaying different visual techniques. The second project is a model and the third is a set of drawings that represent that model.

A Corner of SCI-Arc

These projects deal with the abstraction of SCI-Arc. Moving from the folded line of SCIArc from 1GA Design Studio Project 1, these projects look at a single fold within that model. Assembly, specification, and material qualities are important aspects of the development. The resulting is a plaster cast model of the interior volume of the said corner and a set of drawings that articulate that corner.

The plaster & 3D print model deals with themes of contrast both materially and visually. The white plaster cast has a handmade natural quality that contrasts with the black plastic 3D print representing a machinelike quality. This model looks at the boundaries that exist between physical and digital methods of production. The drawings focus on material representation and the subtle articulation of such. The drawings offer a level of detail that changes from the distance of the reading, i.e., the closer it is read, the more information is revealed. The model and drawings together introduce a conversation about methods of material representation.

PROJECT 2 & 3 9 WEEKS

Applied Studies

Introduction to Autodesk Revit

SUMMER 2024

JOE D’ORIA

This course focuses on Autodesk Revit and its role in a professional office setting. The principles of Building Information Modeling (BIM) will be introduced and applied through a series of exercises involving both 3D modeling and documentation using Revit. Topics will cover the basics of Autodesk Revit, including file creation, modeling, and documentation. In addition to learning how to use the software, the course will explore when and why it is favored in the industry over other tools. External add-ins that can assist with day-to-day tasks in Revit will also be discussed.

Artist Retreat

Project Scope:

Design an ideal creative space for yourself. This space can be either in an urban environment or in a remote location. The idea for this space is a space that you as a designer can use to go and create. The program of the house should consist of a creative working space, a living space, a place to eat and sleep.

Project Description:

Discover the ultimate getaway with this exquisite single-family waterfront vacation home, nestled on a serene lakefront property in North Carolina. This 2-bedroom, 2-bathroom retreat blends modern luxury with sustainable living, offering an unparalleled escape into nature. Crafted with wood construction and straw bale insulation, the home is both beautiful and ecofriendly, ensuring comfort and sustainability. Large windows and outdoor living spaces enhance your connection with the scenic surroundings, creating a seamless indoor-outdoor experience.

Location: North Carolina

Site: ≈ 46,000 sq. ft.

Program: Residential

Number of Stories: 2

Type of Construction: Concrete,

Wood with Straw Bale Insulation

WEEKS

G

Advanced Embodied Carbon

FALL 2023

SOPHIE PENNETIER

The undeniable role and responsibility of Architects in the realm of mitigating global warming is emphasized in this course. According to the United Nations (as conveyed by the Carbon Leadership Forum), buildings contribute to 40% of worldwide emissions. These emissions include operational (e.g., electricity, fuel, repairs) and upfront, also known as “embodied carbon,” encompassing upstream emissions in the procurement, transportation, and manufacturing of construction materials.

Similar to the Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions of any entity (e.g., a Corporation, a School, etc.), buildings exhibit direct, upfront, and indirect emissions. Architects’ choices, advocacy, and education impact some of the world’s most significant emissions and constitute a professional liability.

This course provides essential tools to enhance the understanding of the carbon assessment of major construction materials and building operations. As an advanced course, it is highly recommended to be taken concurrently or subsequently with other carbon-centered courses offered at SCI-Arc, such as Environmental Studies I and II and the Carbon-Informed Design layer of the Design Development project.

The development of an individual project is involved. Similar to a mini-thesis, this assignment involves formulating and addressing a specific question, accompanied by documentation, related to the impacts of global warming on the Built Environment.

Mývatn Beer + Spa

In my individual project, I extended my exploration of material carbon impacts within the built environment by delving into the details of my 3GA studio project. The focus of this endeavor was the development of a beer spa in northern Iceland. From the initial stages of the design process, I took the initiative to conduct a comprehensive carbon assessment, specifically evaluating different building materials, particularly those related to the structure. To enhance the project further, I applied knowledge acquired from the course and engaged in insightful conversations with two Icelandic engineers. Their expertise played a crucial role in informing and influencing the design decisions. As a result, the project addressed the creation of a beer spa and provided valuable insights into conducting carbon assessments and life cycle analyses within the context of a small-scale building project.

Location: Mývatn region, Northern Iceland

Site: ≈ 423 sq. m.

Client: Owner’s of the Sel Hotel

Program: Brewery, Beer Spa, Souvenir Shop

Square Meters: ≈1,268 sq. m.

7 WEEKS

SITE

Q+A

IN CONVERSATION WITH DR. THOMAS HENRIKSEN & STURLAUGER ARON ÓMARSSON

Dr. Thomas Henrikson is the Founder & Director of Henrikson Studio. Thomas has a Doctorate in Architectural Engineering from TUDelft and over 20 years specialised experience in structural and facade engineering across a range of energy efficient buildings and infrastructure projects worldwide. Previous roles include Global Facade Leader at Mott MacDonald Ltd, Technical Director at Waagner-Biro Stahlbau AG and Technical Director at Seele Austria GmbH. He was also a Project Manager for ÍAV hf., also known as IPC (Iceland Prime Contractors), and Senior Structural Facade Engineer at Ove Arup Ltd.

Sturlaugur Aron Ómarsson is a Civil Engineer, M.Sc. and Managing Director at NNE Verkfræðistofa. His expertise includes Project Management APME, General Structural Design, Steel Design, Concrete Design, Earthquake Engineering Design, Design of Timber Structures, Tender Documents and Project Specifications, and CFRP Reinforcement.

When comparing Timber and Steel structural solutions for the building, the A1-A3 carbon isn’t significantly different at that scale. That was calculated by using US values and discounting transportation, since at the GWP levels we have, freight would range within a small percentage, which is irrelevant at concept stage. Do you have access to Icelandic GWP baselines or do you have any recommendations?

TH: I do not, Iceland mainly import all material from Europe/China. Except for Aluminum, however to my knowledge they do not extrude or powder coat.

What are the low carbon concrete options in Iceland? Is concrete the most common construction material for low/mid rise?

TH: Not sure, however most likely they would have to import the Cement from Denmark (Aalborg Portland). In terms of low rise buildings always concrete due to earthquake.

SAO: Concrete is the most common building material here in Iceland. All cement is imported, there is a low concrete option available where quantity of cement is reduced and replaced by adding fly ash (flugaska) and silica fume (kísilryk). The Nordic eco label requires this low carbon concrete to be used in at least two structural components in order for the building to get the eco label. Often contractors use this concrete in foundations and parapets. Some contractors claim its not as easy to “work with” this low carbon concrete.

What proportion of structural steel is imported, in your experience?

TH: 100%

SAO: All building material is imported except for insulation.

Looking at local materials, I was curious about the use of lava rock, do you know precedents related to Icelandic lava rock aggregates for concrete?

TH: That is a good question, I am not sure, however I think that they import most of the aggregates, as well.

My design includes a double skin façade which is aluminum intense. Following your recommendation, I will look into it and swapping from US-baselines Aluminum to Icelandic aluminum might yield about 15% carbon reduction at core and shell level. Yet how prevalent is the use of overseas vs domestic aluminum, for complex facades in Iceland? What about glass?

TH: All main materials are imported. They do assembly glass in Iceland, however large quantities are imported.

Denmark is certainly leading the charge in terms of decarbonization, how doe s it compare to the Icelandic market and policies?

TH: Iceland is following this, however they have a full green electric supply, district heating as well. So they are less concerned in some ways. However they have to transport all main material via sea.

Do green roof make any sense in those climates?

TH: not really they just blow off, they mainly do steel corrugated roofs, that is fixed against wind and can take the snow.

Do you have any other pointers?

TH: Not sure, I hope it helps. Iceland is a interesting place, they do have extreme weather conditions (Wind and Snow) and frequent earth quakes, daily at the moment.

SAO: One floor industrial buildings are often steel frame buildings cladded with steel sandwich panels. Multistorey commercial buildings are usually done in concrete, sometimes the staircase/ elevator shaft is in concrete for horizontal stability and steel columns/beams to support the slabs. In multistorey buildings made in structural timber/massive timer elements, sound and fire protection requirements are hard to fulfill/ expensive. There is one such building here in Iceland that I know of. Some areas on Northern shore have earthquake up to 0.5g. Meaning ca. 50% of building total weight must be applied horizontally in structural design.

CARBON COMPARISON

Taking the overall areas from different aspects of my project and the baseline GWP’s for those materials, I calculated the CO2 equivalent for two structural systems. I compared the results of a timber structural assembly and a typical steel and concrete assembly. My results yielded a surprising result; showing that the A1-A3 carbon isn’t significantly different at this scale.

*GWP Data from CLF 2023 & US facades trends amended with Icelandic Aluminum

CARBON REDUCTION STRATEGIES

APPLIED + POTENTIAL STRATEGIES

PROCESS STRATEGIES

Identify embodied carbon as a priority

• In crafting the architecture for this project, the unique challenges and opportunities presented by Iceland’s native material and geological identities take center stage.

• The fact that Iceland traditionally relies on imports for most materials lands the project at a sustainable crossroads.

MATERIAL + SYSTEM SELECTION STRATEGIES

Selection of carbon-storing structural, envelope, insulation, & finish materials

• Bio-based materials typically have lower upfront embodied carbon than conventional non-bio-based products and have the potential to store carbon over the life of the building.

• Bio-based materials like mass timber are significantly lighter than their alternatives, reducing the load and size of supporting structural members.

• Alternative insulation materials have been considered, with a strong push towards potentially using hemp instead of the standard fiberglass or mineral wool.

Select salvaged materials

• Work with the building owner to reuse materials on-site.

Select finishes carefully

• Minimize finishes where not required for functional performance.

• Select low-carbon finishes where available.

• Many areas of the design do not require additional finishes beyond the structural members. Where finishes are required, low-carbon finishes were utilized or considered.

• The utilization of locally abundant basalt rock for the beer baths and the tile in the spa area introduces a regional material alternative.

SPECIFICATIONS + PROCUREMENT STRATEGIES

Optimize concrete specification & mix design

• Minimizing the volume of portland cement by replacing cement with Type 1L cement, fly ash, slag, and other supplementary cementitious materials.

• All concrete in the project is required to be a low-carbon option.

• The Nordic Eco-Label mandates the integration of low-carbon concrete in at least two structural components for accreditation.

• The overall reduction of concrete in the project and the use of low-carbon alternatives will contribute to the global effort to combat the 8% of emissions stemming from concrete production.

Source sustainable wood

• The full life cycle of embodied carbon impacts and benefits of wood are often difficult to quantify because of complex supply chains and differing methods for calculating carbon benefits.

• Current procurement strategies include using reclaimed wood, asking for chain of custody certificates or other supply chain transparency information, and asking for sustainable forest management certificates (FSC).

• Utilizing mass timber members that have been sourced from responsibly managed forests, specifically those certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is critical and can contribute to wood’s overall carbon impact for the project.

Source low-carbon aluminum

• The project looks to embrace Iceland’s recent aluminum production, which aims for a 15% carbon reduction at the core and shell levels.

Advanced Project Delivery

FALL 2023

PAVEL GETOV KERENZA HARRIS

JOE D’ORIA

This course focuses on advanced methods of project delivery and construction documentation, integrating digital technologies (Revit) and investigating innovative models for linking design and construction processes. It introduces Building Information Modeling (BIM) as a tool for realigning traditional relationships among project stakeholders. Detailed 3D digital models and a set of 2D construction documents tailored to the project’s design challenges are generated through the analysis and development of a mixed-use program on an urban lot in Los Angeles. Lectures further acquaint participants with technical documentation methods for projects operating at the forefront of current design and construction technologies.

14 WEEKS IN COLLABORATION WITH CHRISTIAN FILIP

JILLIAN LEEDY

YEH-TING LI

AUSTIN NEUMANN

EXCLUSIVE OF VENT SHAFTS AND COURTS, WITHOUT DEDUCTION FOR CORRIDORS, STAIRWAYS, RAMS, CLOSETS, THE THICKNESS OF INTERIOR WALLS, COLUMNS OR OTHER FEATURES. THE FLOOR AREA OF A BUILDING, OR PORTION THEREOF, NOT PROVIDED WITH SURROUNDING EXTERIOR WALLS SHALL BE THE USABLE AREA UNDER THE HORIZONTAL PROJECTION OF THE ROOF OR FLOOR ABOVE, THE GROSS FLOOR AREA

SHALL NOT INCLUDE SHAFTS WITH NO OPENINGS OR INTERIOR COURTS.

2. ZONING CODE 1203 - FLOOR AREA THE AREA IN SQUARE FEET CONFINED WITHIN THE EXTERIOR WALLS OF A BUILDING, BUT NOT INCLUDING THE AREA OF TEH FOLLOWING: EXTERIOR WALLS, STAIRWAYS, SHAFTS, ROOMS HOUSING BUILDING-OPERATING EQUIPMENT OR MACHINERY, PARKING AREAS WITH ASSOCIATED DRIVEWAYS AND RAMPS.

J. ADDRESS AND LEGAL INFORMATION

PROJECT ADDRESS 405 2nd Street Los Angeles, CA 90012

LOT AREA 17,888.9 SF APN 5161018007

TRACT SUBDIVISION OF BLOCK A OF J.M. DAVIES TRACT MAP REFERENCE M R 66-97 BLOCKS NONE LOT 8

ZONING [Q]C2-3D-O-CDO

Practice Environments

FALL 2023

MICHAEL FOLONIS

This course critically examines the impact of professional architectural practices on the development and orientation of architectural design, production, and education. It involves a comprehensive exploration of the architectural profession, encompassing licensing, legal requirements, adherence to codes and budgets, and its position in relation to competing professions and financial interests. The course aims to enhance understanding of registration law, building codes, professional service contracts, zoning and subdivision ordinances, environmental regulations, and other licensure-related considerations.

Insights into the administrative role of architects are provided, covering aspects such as securing commissions, selecting and coordinating consultants, negotiating contracts, project management, egress considerations, code compliance, and principles of life safety. There is an emphasis on developing effective communication skills for engaging with clients and user groups. Additionally, the course analyzes trends like

globalization and outsourcing, assessing their potential impact on the architectural practice. The Emerging Professionals Companion and updated information on the Intern Development Program (IDP) are provided.

Key topics covered encompass human factors, planning, scheduling, cost control, risk management, design and construction management, as well as the latest advancements in information technology for project management. The course delves into inquiries such as the criteria for clients when selecting architects, strategies architects employ to secure commissions, the processes involved in publicizing and publishing projects, the steps to obtain and uphold licensure, and the crucial aspects of collaboration with engineers, consultants, and contractors. Additionally, it offers insights into initiating an independent practice and collaborating with owners, contractors, and developers.

IN COLLABORATION WITH TARA AFSARI

CHRISTIAN FILIP

JOHARATULMAJD RAAIQ

CHUEN WU 14 WEEKS

S TUDIO FLOW

S TUDIO FLOW

PROJECT PROPOSAL

Our team at Studio Flow understands the importance of selecting a team of designers that will be able to make your vision for your property at 837 6th Street in Santa Monica a reality. Therefore, our team is enthusiastic to submit ourselves for consideration as the project’s primary architecture firm.

Our experiences and skillsets both individually and as a team of architects and designers make us a great candidate for your project. Our portfolio of work contains examples of similar scale built projects which showcase our abilities to create a project for you that resembles your vision. Studio Flow's approach to every project is rooted in creativity and we believe that a well-designed space can significantly impact people's lives and the environment.

The site and project sparked the interest of our team of designers, and we are excited to explore the myriad of possibilities that the site offers. The charming neighborhood embodies key elements of a project we aspire to create. With its abundance of vegetation and its close proximity to many amenities, the location offers ideal conditions for a duplex property. Given the current housing demands in LA County, there is a strong indication of a promising return on investment, paving the way for the establishment of a project that seamlessly combines beauty and profitability. Our team wants to assure you that we are dedicated to not only meeting but exceeding your expectations.

We would be delighted to engage in a more in-depth discussion about your project and to explore ways in which we can turn your vision into a reality. Please do not hesitate to contact me to arrange a meeting at your convenience.

Thank you for considering our proposal. We look forward to the possibility of collaborating on this exciting architectural project. Together, we can create a space that inspires, fulfills, and leaves a lasting impact.

2GB Design Development

SPRING 2023

HERWIG BAUMGARTNER

SCOTT URIU

MATTHEW MELNYK

JAMEY LYZUN SOPHIE PENNETIER

This course delves into aspects concerning the execution of design, encompassing technology, material utilization, systems integration, and fundamental analytical approaches such as force, order, and character. It encompasses a thorough examination of both basic and advanced construction techniques, the scrutiny of building codes, the design of Structural and Mechanical systems, Environmental systems, and Buildings service systems. The course also addresses the development of building materials and the integration of building components and systems. The primary goal is to foster a comprehensive understanding of how architects convey intricate building systems within the built environment, demonstrating proficiency in documenting a comprehensive architectural project and exercising environmental stewardship.

RHINO GRASSHOPPER

ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR

ADOBE INDESIGN

ADOBE AFTER EFFECTS

CINEMA 4D

OCTANE

The method for design development goes beyond mere technical progress for the project; it is also a disciplinary advancement. In this context, the course aims to question conventional representation methods and seek relevance in a time when the documentation of design and manufacturing is undergoing changes, relying more on threedimensional live data. While Building Information Modeling (BIM) represents a significant step forward, the objective is to reconsider how we can imagine and convey design through innovative approaches that go beyond the design object itself.

The Gap by SSAKKI

Working from my and India Chand’s 2GA Studio project, my group and I were dedicated to enhancing the technical aspects of the project. We focused on making essential improvements while upholding the overarching design goals established during the initial design phase. This involved meticulously examining structural considerations, particularly addressing the challenges related to the “gap” floor. Additionally, we carefully considered refining the facade’s aesthetic appearance. Moreover, we were conscientious about the environmental impact of our material selections, aiming to minimize the carbon footprint associated with the construction materials chosen for the project.

14 WEEKS

IN COLLABORATION WITH INDIA CHAND ATHENE HO KYLE JENSEN SEVAG KOUROUNIAN

EMBODIED CARBON

Strategies to reduce embodied carbon footprint:

- Our biggest impact comes from the structural steel (Which is 1033,250 kg CO2eq/m3.) An Alternative Would be Cross Laminated Timber -77,688 kg CO2eq/m3.

- Originally we chose spruce as our flooring which we keep The same at an output of -164,830 kg CO2eq/m3.

- We would swap our EPS insulation Graphite 80 (1,111.0 kg CO2eq/m3.) For hemp insulation at the result of 490.4 kg CO2eq/m3. -The aluminum framed windows which are currently at a GWP rate of 50,426.1 kg CO2eq/m3. Can be replaced With. Wood-aluminum framed windows with an embodied carbon Of 32,791 kg CO2eq/m3.

TOTAL 2,621,275.5 KG C02 eq DRAWN

Environmental Systems

FALL 2022

RUSSELL FORTMEYER

ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR

ADOBE INDESIGN

The course emphasizes the pivotal role architecture plays in responding to sustainability, climate change, and resilience. It shifts the focus from aesthetic and cultural criteria to the performance of architecture in terms of energy and resource modulation, creating comfortable spaces, and actively addressing environmental challenges. Beginning with an exploration of climate constraints and the human body’s response, the course delves into site analysis, considering urban context, historic fabric, ecology, and climate. Subsequent lectures examine how architecture has evolved in response to these constraints, with a specific focus on environmental systems design, heating and cooling, ventilation, lighting, facades, and various building systems. The class culminates in exploring integrated design for buildings and cities within the broader ecological context of climate change and sustainable design, highlighting the generative potential of integrated environmental systems in architectural projects while considering social and cultural values. Strategies such as Zero Net Carbon (ZNC) buildings and the circular economy will also be explored.

In the initial phase of the semester, Project 1 is centered on a distinct public space in Los Angeles. The focus is on analyzing the site’s environmental conditions and vulnerabilities concerning pedestrians. Through a precedent study exploring global best practices in microclimate and public space design, Project 1 culminates in a design proposal. The proposal aims to enhance site conditions with specific, measurable outcomes related to climate considerations and environmental quality, including air quality and site acoustics.

Project 2 focuses on a museum in Southern California as a case study and develops a retrofit approach for decarbonization. The goal is to investigate various systems, including the façade, energy, mechanical, water, and materials. Project 2 proposes a design intervention aimed at reducing or eliminating the museum’s carbon footprint while enhancing the building’s overall human experience.

14 WEEKS

IN COLLABORATION WITH MICHAEL BOLDT

JILLIAN LEEDY

ARAM RADFAR

RUITING XU

SITE + CLIMATE

INTERVENTION

Plants

CASE STUDY

CONTEMPORARY @ MOCA

CALENVIROSCREEN + MYHAZARDS

Significant Environmental Effects for the Geffen site under Pollution Burden include:

Solid Waste: 94%

This indicator is calculated by considering the number of solid waste facilities including illegal sites, the weight of each, and the distance to the census tract.

Hazardous Waste: 92%

This indicator is calculated by considering the number of permitted Treatment, Storage and Disposal Facilities (TSDFs), generators of hazardous waste or chrome plating facilities, the weight of each generator or site, and the distance to the census tract.

Cleanups: 86%

This indicator is calculated by considering the number of cleanup sites including Superfund sites on the National Priorities List, the weight of each site, and the distance to the census tract.

“Pollution Burden represents the potential exposures to pollutants and the adverse environmental conditions caused by pollution.”

Population Characteristics Percentile: 88%

“Population Characteristics represent physiological traits, health status, or community characteristics that can result in increased vulnerability to pollution.”

MyHazards

Earthquake - High hazard warning, specifically high ground shaking Near a liquefaction zone area Flood - Low hazard warning Outside of fire and tsunami hazard zones

Significant Exposures for the Geffen site under Pollution Burden include: Diesel Particulate Matter (PM): 96%

Sources of diesel PM in this census tract and nearby emit 0.722 tons per year.

Drinking Water Contaminants: 93%

The drinking water contaminant score for the census tract containing the site of the Geffen is 788. This is the sum of the contaminant and violation percentiles.

*This indicator does not assess whether your water is safe to drink.

PM2.5: 92%

The census tract that contains the site of the Geffen has a concentration of 12.71 micrograms per meter cubed.

California PM2.5 concentrations range between 1.9-16.4 micrograms per meter cubed.

Toxic Releases: 81%

This indicator takes the air concentration and toxicity of the chemical to determine the toxic release score.

The toxic release indicator scores range from 0 to 96,985.

The score for this census tract is 2,161.45.

Ozone: 54%

This census tract has a summed concentration of 0.048 parts per million (ppm).

Ozone concentrations in California range between 0.03 - 0.07 ppm.

These exposures deal with a variety of particle, chemical, and bacterial impacts to the air and water around the Geffen. Each exposure has specific sources for the contaminant and those sources make sense as to why the Geffen would have such higher percentiles in the categories. The Geffen is surrounded by rail yards, freeways, factories, and construction sites. The site is also impacted by sewage and runoff.

Exposure to these chemicals and bacterias are harmful to health and can lead to chronic illnesses including heart and lung diseases, cancer, and blood disorders.

Impaired Waters: 67% When water bodies are contaminated by pollutants, they are considered impaired. This indicator is calculated by considering the

Materials & Tectonics

FALL 2021