foundingeditor&co-editorinchief addie tsai

co-editorinchief

sarah sheppeck

disability&accessorganizer

sky cubacub

editor,themaneattraction

sarah sheppeck

editor,theglowup&afrodisiac

sarah sheppeck

editor,solemates&(getyour)threadinthegame jen st. jude

editor,noscrubs

jo davis-mcelligatt

editor,sewwhat¬whatitseams

jj rowan

editor,triplethread(s)

kirin khan

editor,cancel&gretel

sky cubacub

editor,features&fat+furious addie tsai

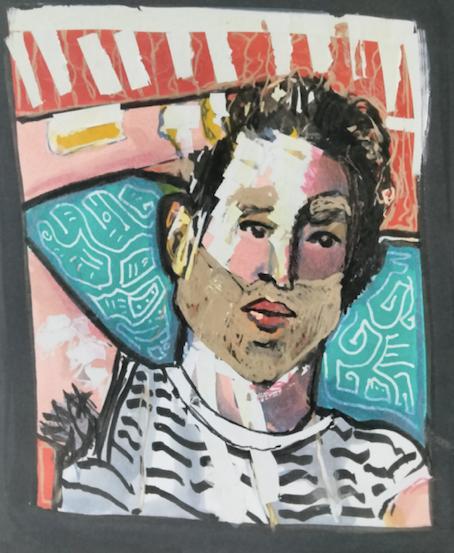

coverart

crystal vielula

issuedesigner

keet geniza

just femme & dandy is a biannual literary & arts magazine on fashion for and by queer, trans, two-spirit, nonbinary, and intersex people. We are an anti-racist, pro-Black publication and aim to centralize and celebrate work from Black and Indigenous people of color. We encourage submissions about fashion and “in”/visible disabilities, fatness, chronic illness and pain, poverty, neurodiversity, mental illness, and other forms of intersectional marginalization.

We believe in equal access to collective joy, so all art in this issue can be found on our website in plain text with image and audio descriptions and captioning. For additional access needs, please contact our disability & access organizer Sky Cubacub.

vol.05:summer2023

©2023justfemme&dandy

justfemmeanddandycom

tableofcontents letterfromtheeditor|6 anoteonaccess|7 cancel&gretel michellezacariaslosingmylegandfindingmyfooting|9 nickvanzantenmyformfits|12 marta“elena”cortez-neavelthingsstartedfallingapart|17 fat+furious sghuertacrowdedcloset:crawlingtowardsselflove|28 theglowup alisonlubarMANI-CUREforthenewlyassembledthankstovoguevoid|31 ashishkumarsinghnailpolish|32 carapleymthewayyoushouldalwayshavelovedyourself|33 aubrythrelkeldmyaunttheresa/mygiacarangi[killedherself–she visitedthreetimesaftershedied]|34 themaneattraction erikfuhrerreachoutandbrushfaith|37 afrodisiac davinmakokhacottonballsforthelonelyfloor|43 noscrubs dandy-liaccothemaskasfashionaccessory|46 ethanwoodroom448b|51

tableofcontents

sewwhat

laurensamblanetwebsspunbysmallcreatures|61 giondavisthisbarbieisaken|68

t-boyswag|71 pimhalkaglitterbeard|74 notwhatitseams

howglitterwasinvented|78 jfrausto@the.thrifted.gay|79

solemates

angelleybaicrywhenirewatchrupaul’sdragraceseason9|83 stephscottfindingmyselfinmysneakers|84

triplethread(s)

alisonlubarfemmedragon|90

j.d.gevry“canihelpyoufindanything?”:myhuntfortranstastic weddingattire|91

alexcarriganblackisthecolor|98 riverbarefootonabalustrade;beaded|99-100

maggiechirdolikebones,likeskin:agoldenshovelafterkimaddonizio; florals?forspring?groundbreaking;intricateritualsfortouch; billcunningham'sghostleadsme;selkiestatisticaloutliers|101-105

106

108

111

123

maxstone

brodyparrishcraig

features

hollygenovesetheotherside|

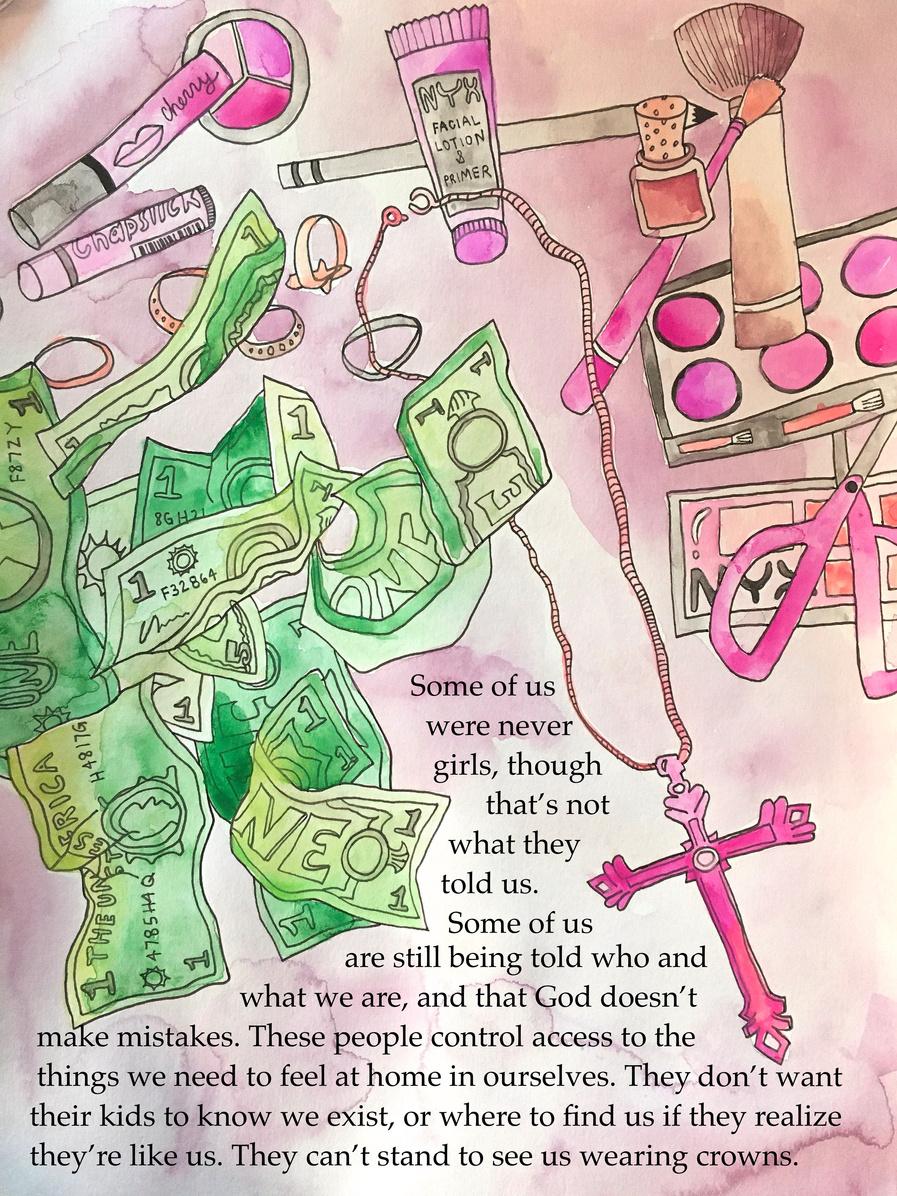

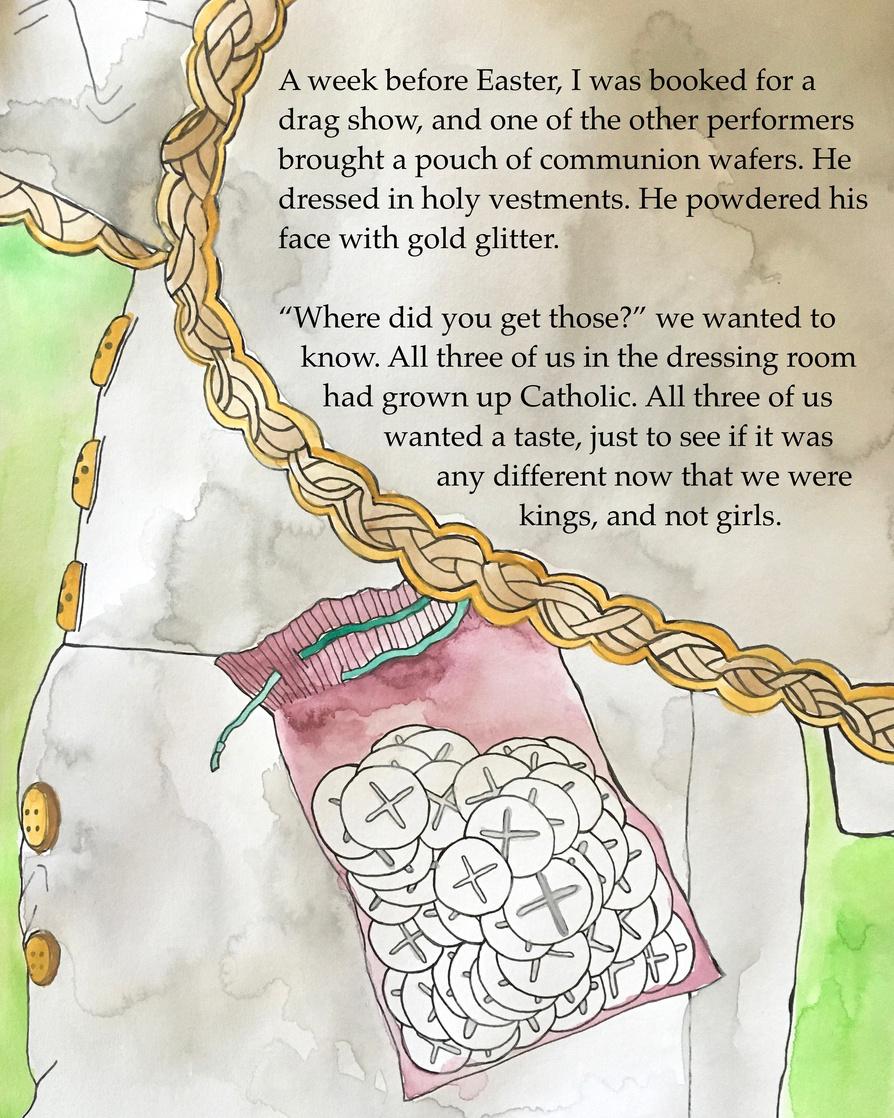

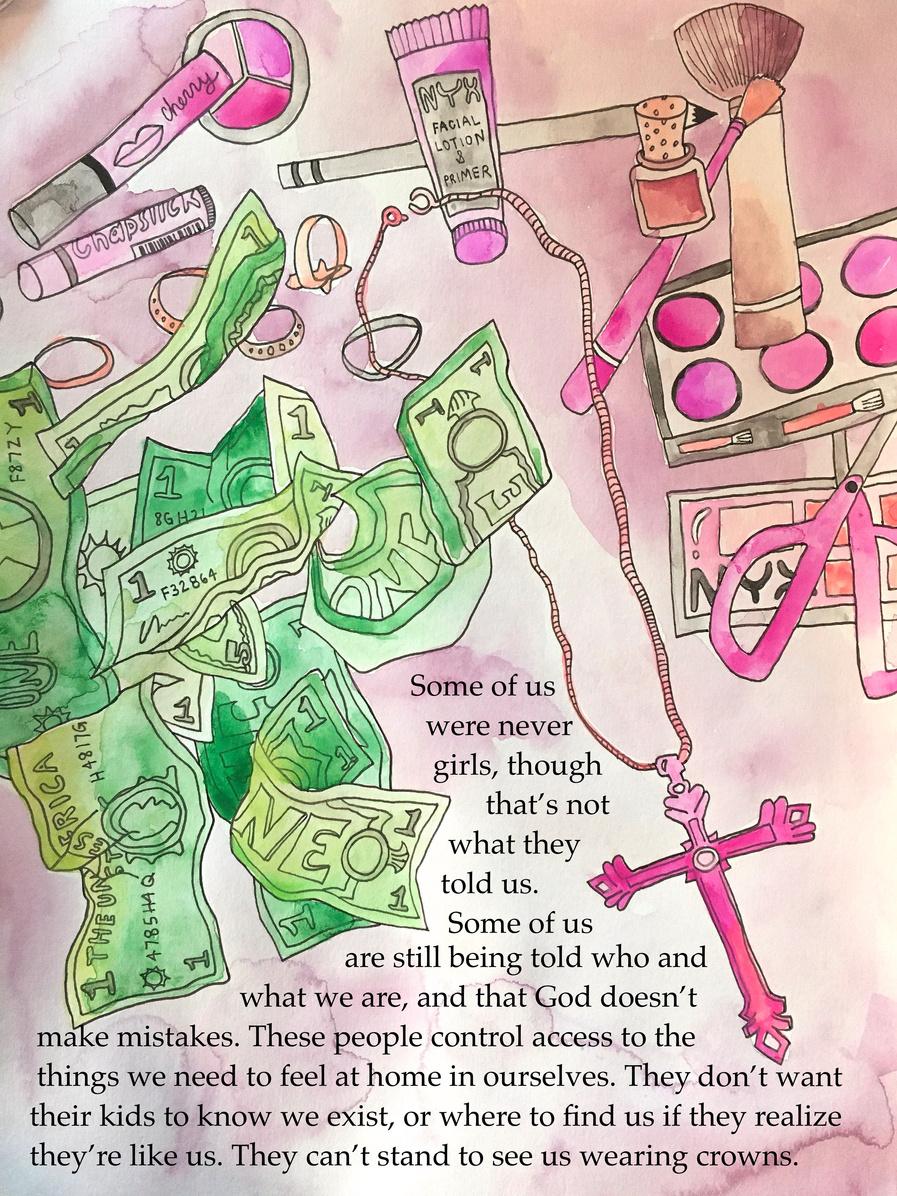

gabemontesantikingsandnotgirls|

alisonlubarthegender-affirmingcloset|

claraotto

abouttheartists|

abouttheteam|

luckygirl|114

118

letterfromtheeditor

When the late, great Nina Simone an icon in the truest sense of the word died in 2003, she left behind a legacy that met at the intersection of art, civil rights, and Black excellence. Though April marked the twentieth anniversary of her passing, her impact continues to be felt in art of all genres and mediums, as if the parts of her she chose to share with us are still brimming with life.

This volume’s theme, Resurrect, was selected in Nina’a honor. Addie and I hoped to inspire pieces about rising from ash, about building a new life from rubble, about standing up for the final round just when everyone else thought it was over. And, of course, we wanted it all captured through the lens of queer fashion.

This volume’s submissions did not disappoint, and our sections are packed with pieces that span style, format, meaning, and message, much like the work of Ms. Simone herself.

Our stellar team of editors selects each submission with love and care, and none of them are to be missed; however, there are some personal favorites that I hope you’ll spend some extra time with. This volume’s cancel & gretel section is packed with exceptional work, like Michelle Zacarias’s essay, “Losing My Leg and Finding My Footing.” afrodisiac features a striking poem about the proverbial Big Chop, by South African writer Davin Makokha. And of course, I’d be remiss not to give a special shout-out to Ethan Wood’s important piece on age gaps in relationships among gay men, which was illustrated by our own Jo Davis-McElligatt.

As you explore the issue, you’ll likely notice that things look a little different. We figured that while we were on the subject of resurrection, we’d breathe some new life into just femme & dandy with a completely new layout and design, courtesy of our incredible graphic artist Keet Geniza. We have big plans for our little passion project and are honored to have your support along the way.

We are, as always, deeply proud of this volume and the work of our contributors. We hope that as you make your way through the issue, something you once believed was long dead in you is resurrected as well.

Feeling Good,

Sarah Sheppeck Co-Editor-in-Chief

anoteonaccess

I am Sky Cubacub, the creator of Rebirth Garments, a clothing line for queer and trans disabled folx of all sizes and ages, the writer of “Radical Visibility: A QueerCrip Dress Reform Movement Manifesto” and just femme & dandy's cancel & gretel editor! I will share my identities with you all so that you understand where I’m coming from and who is in charge of accessibility for this awesome magazine! I am queer, nonbinary xenogender, and I use they/them/their and xe/xem/xyr pronouns. I’m half Filipinx-American and half white, and I am in my early thirties. I have non-apparent disabilities including lifelong anxiety, panic disorder, depression with a still undiagnosed developed stomach disorder I acquired later in life, C-PTSD (I am a survivor of DV), and newly diagnosed Chronic Fatigue Syndrome that developed after having Mono.

For this issue & going forward for all future issues, we asked contributors to write make their own image descriptions! Image descriptions and audio descriptions are always incomplete because you can endlessly describe anything. If you are interested in learning how to make internet content accessible, follow my friend Alex Chen on Instagram. You can also check out the Alt Text as Poetry project, a collaboration between artists Bojana Coklyat and Shannon Finnegan, supported by Eyebeam and the Disability Visibility Project.

Access can always be improved, so please contact us to request specific accessibility accommodations you need, and I will do my best to make it happen!

cancel&gretel

losingmylegandfindingmyfooting michellezacarias

I lost my leg when I was 9-years-old, which is honestly a terrible age to become an amputee.

Not that there is necessarily an “ideal” moment to lose a fourth of your body, but at 9years-old I was still learning so much about my “brand” and identity. Was I an alternative chick? Was I a tomboy or was I defying gender norms because I was very gay? Was I the artsy nerd who took down her ponytail and took off her glasses to then become an overnight prom queen? Could I be the beloved “hot Cheeto” girl who rocked oversized hoops and Cookie Monster pajama pants - successfully setting the bar for peak 2000’s middle school aesthetics?

I was none of that. I was an awkward pre-pubescent Latina girl who was one leg short of having a shot at being popular.

I never considered myself “fashionable” growing up. Partly because I had no sense of “style” but mostly because my disability made it impossible to find comfortable, cute and accessible brands. Nobody ever tells you that when you become disabled your clothing and shoe options become severely limited which is also the case for fat folks, trans/nonbinary folks and pretty much anyone who falls outside of fashion brand’s target demographics.

I, on the other hand, never even got to even establish how I wanted to be perceived before I was shoved into oversized jeans and black slip-on orthopedic shoes. Good shoes are imperative for lower-limb amputees; your shoes must support the entire weight of your shifting and wobbling body as you’re re-learning to walk. Shoes must withstand the wearand-tear of the impact that the prosthetic foot has on the ground. Shoes should make it easier to navigate an already ableist society.

09

I was always stuck with ugly brown or black Velcro sneakers that clashed with practically everything I wore. This was my abled-bodied mother’s way of dealing with the difficulty of working my prosthetic foot into shoes. I don’t particularly blame her sensible cute shoes were expensive. Orthopedic shoes are also necessary for various types of people, but we are hardly presented with a variety of options. I wish we were allowed to take up visual space, even if it means less money for corporations.

That’s the thing nobody talks about, although we make up about 27% of the U.S. population, disabled people are not seen as “profitable.” Instead, we are conditioned to shrink ourselves and hide our disabilities… or otherwise “pass” in society. After all, we are already “inconveniencing” people with our ACCESS NEEDS, God forbid we demand comfortable shoes that are reasonablypriced and look amazing with our various bodies.

I dressed in camouflage for many years, figuratively speaking. I wore whatever it was that made me disappear into the background. It was either blend in or get relentlessly bullied. In 7th grade I had a middle-school bully named Kyle who made my life a living hell. He wasn’t the only one, but he was definitely the ringleader of the group and I was his favorite target.

The first time that I recall having normal conversation with Kyle was when I showed up to school in Timberland boots. I asked my mom to buy me a pair because they were durable and easy to slip on my prosthetic foot. Unbeknownst to me, they also happened to be one of the most popular shoe brands out at the time (I was very sheltered lol). Timberlands had the structural makings of a combat boot but with a cool suede exterior and were being frequently worn by rappers like Jay Z, DMX, and members of the Wu-Tang Clan. Cam'Ron famously owned customized pink Timberlands and R&B singer Aaliyah (RIP) always wore the traditional beige ones.

10

Afterall,wearealready "inconveniencing"peoplewith ourACCESSNEEDS,Godforbid wedemandcomfortableshoes thatarereasonably-priced andlookamazingwithour variousbodies.

I distinctly remember arriving at school that morning, putting my backpack down on my desk and hearing Kyle from behind me ask, “Are those Timberlands?”

I was too flustered by the lack of hostility and genuineness of the question to answer right away, “Um…yeah I think so.”

He looked me up and down, calculating how to respond. Meanwhile, I held my breath.

“They’re cold.”

That was probably the first and last time we ever had a conversation that didn’t involve him berating me (although honestly fuck that kid, I hope he ended up becoming a better more empathetic adult lol). The interaction left an impression on me though it allowed me to feel seen in a world that typically made me feel so invisible. At 33-years-old I still don’t consider myself “fashionable,” but I do feel confident and affirmed in my body. I don’t shrink myself anymore.

Who knew fashion could bring out the humanity in people? ■

11

myformfits nickvanzanten

When at age 18 I left Evanston, Illinois, just outside Chicago, to go to art school in New York, I didn’t expect that I’d ever return. So years later when, feeling stuck in my art and my life, I applied to MFA programs, I was ambivalent to find that the only one that would take me was in Chicago. Convinced though I was that graduate school would be the change I needed, I was still afraid to move back. I eventually decided to go under the premise that returning to my hometown was how I would discover what it was that felt so wrong. I would take a little trip to Chicago to rectify myself so that I could come back to New York able and ready to really live. I thought of it at times as a pupation, as in how a caterpillar becomes a butterfly.

It took the better part of a decade but I actually managed to do it, or at least to start. I didn’t know consciously at the time that what I needed to do was come out as bi, kinky, and trans nonbinary. At some level, not even all that deep, I knew I was all those things, but at the time I’d thought I’d keep on pretending not to be forever. I’d been making bad art, and wrecking relationships and friendships and just generally being unhappy in New York because I’d been committed, since my teenage years, to closeting myself in almost every way that mattered, and nearly everything that I did was a lie told in service to that. The art that I applied with - which was well enough received to get me waitlisted at some fancy schools - was all about taking something and painstakingly making it look like it was something it wasn’t. Packing peanuts that are cement instead of styrofoam, that sort of thing. They must’ve seen promise in my winking at them, but worried, not unreasonably, that I was too timid to fulfill it. Over the course of my time in Chicago, though, I grew to be more honest with myself and in my art. Coming, as it did, from a place of sly reference it provided me with a way to slowly, sheepishly introduce the real me to myself and to the world, and to imagine and experience myself as I really wanted to live.

12

I started sewing right around the time that I moved, teaching myself through YouTube videos and with help from my mom and some friends who worked in fashion. I admired Leeza Meksin’s fiber work, and she inspired me and told me where to shop. I was lucky enough to live across the street from a store - Discount Textile Outlet, in Pilsen, Chicago - that had an irresistible selection of loud, garish fabrics. Not even knowing what to do with them I loaded up on shiny and iridescent lycras and vinyls. I began with underwear made out of woodprint spandex, then moved onto leggings and skirts. Despite being in an MFA program my art wasn’t nearly as exciting, so I started folding the clothes I was making into my paintings, making them partially wearable. I called these pieces Formfits, which worked on many levels but also happened to be the name of

the lingerie company that had originally occupied the building my graduate program was in. A formfit comprised a garment, which I might wear, and an abstract construction sewn of the same fabric which would receive the garment when unworn and hold it on the wall to be displayed. They were couched in language of potential, and contingency, but also privacy and exclusivity - if I wore the piece, it would come apart, and so it couldn't all be seen at once. They pointed towards my gender nonconformity without my actually living it. As time went on I became more confident and my personal fashion began to follow what I was doing with my Formfits, becoming more genderqueer. Sewing was incredibly freeing to me because I could wear vinyl skirts without having to worry about sizing or shopping in person and having to brave the women’s

13

section while being read as a man. In time I shaved my beard, grew out my hair, and started using they/them pronouns, and with each of these little steps became happier with myself until gradually something had fundamentally changed inside me, and I became aware of a sort of comfort with myself that I’d never realized I could feel so continuously and publicly.

My final Chicago Formfit, no. 24, is alternatively titled The Parental, and served as a sort of culmination of my whole time in Chicago, completed just before I left. It was as explicitly about being trans as I could get at that moment (having already made artwork incorporating dresses, bralettes, and skirts), and was designed to be shown in my childhood bedroom in Evanston. In late 2021 my parents left town for three months, giving me access to the

house I grew up in without their presencesomething I’d never had except for one time in high school, when I tried to have a party and somehow both failed and had the cops called. When I’d been debating moving back to Chicago friends had told me about the DIY gallery scene there, where people would have art shows in their garage, or on a telephone pole, and I had thought it would be fun to run a gallery (the Parental) out of my childhood bedroom in an iconic middle-class suburb where John Hughes movies had been filmed. My parents, however, had quashed the idea. When they left town I had already decided I was returning to New York in a few months, but the idea came back to me, though now it would only be a single piece, with the room retaining the few traces of my childhood that remained, rather than becoming a bare white cube. I still wasn’t sure what to make for the room, but after much deliberation I gave in to the memories of the meditations that I’d had in that room long ago, and the desires that I had felt while living there and for so long suppressed and denied.

I sewed a padded bra and gaff out of pastel pink and blue velvet, made matching bedsheets, and photographed myself on my childhood bed. I then edited the photos to fit my garment patterns, dropping out cyan in some parts and magenta in others, and sewed a short circle skirt and hooded straightjacket out of them. Wearing these and with new vinyl bedding I shot more photos in my room, which I used to make a fabric-covered foam support on which the clothes could be displayed. The top and the mannequin had straps and buckles,

14

allowing my arms to be held tight around my sides and the square mannequin to fold up, like a taco, and so hold the skirt and top. The straps also connected with attachment points that I installed in my old bedroom, so that the whole piece could hang there. About a month before leaving town I installed it, documented it, and showed it to my mom and dad. I had to pack it up after, because it isn’t my room, and hasn’t been for years. Now it hangs in my studio, a reminder of how far I’ve come, and a nice fit to put on when someone comes by and can help me with the buckles.

Later that year, when having a serious talk about my being nonbinary, my mom raised a question: what would my art be about now? For so long it had been my way of exploring gender nonconformity without

quite committing to being nonbinary. If I were to simply accept myself and live this way my art would have to change dramatically. The Formfits were how I finally found a way to indulge in dresses that folded my arms up at my shoulders and left me helpless. But at the same time, they were premised on there being a boundary between me and my art. By making these clothes as art I’d gotten to try them on, but I also kept myself from wearing them out into the street. I’d done it in part because I felt alone, and that it was the only way I could do what I wanted, but now that I was finding a community of people like me it didn’t have to be my only outlet. All along my art practice had been a reflection of my life, and had gone from being a reflection of my self-denial to a tool that I used to embrace my true spirit.

15

It wasn’t that she thought I’d have nothing to make, just that what I was making would have to be different once I accepted myself and began to live a life that was an actualization of the one I’d tried out in my artwork.

And my art has changed; my purpose in making it has shifted because what I’d captured in it isn’t solely confined to it anymore. I’m still making clothes for myself, many of them with bondage in mind, quite a few of them dresses, but for now I’ve stopped making supports to display them on. Instead of being too precious to wear and sticking them on a wall in a gallery, I’m hanging them in my closet when I’m not wearing them to other people’s art openings. I get a lot more satisfaction out of them now. It isn’t that I didn’t want to do this before, but that I wasn’t ready. I’m past hiding who I am and I don’t need to stand aside from my work as it hangs behind on the wall. My work is me and I can be in it and take it wherever I go. My transness isn’t abstract or contingent - it never really was - and so neither is my art. Rather it is a crucial part of my ongoing self-creation and fulfillment as the trans person I was all along but was too afraid to admit to being. My practice must and will change, as will I, but only for better. It helped me get to where I am now, but I still have a long way yet to go, and a lot more garments to not only make but to wear out, and wear out. ■

16

"I'mpasthidingwhoIam andIdon'tneedtostand asidefrommyworkasit hangsbehindonthewall."

thingsstartedfallingapart

martaelenacortez-neavel

Content Warning: Includes mentions of intimate partner violence

I graduated from college in 2014, with academic awards, artistic recognition, a handsome boyfriend, and a small business designing adaptive clothing and accessories for pediatric patients with medical devices. Over the next few years, my business, Abilitee, grew in size and popularity, and I was accepted into half a dozen U.S. medical schools. Everything I thought I wanted for myself was coming to fruition. My life looked fantastic. But it didn’t feel right.

Not wanting to give up my newfound passion for designing adaptive clothing just yet, I put off medical school for a year. Then another year. When I finally started school in California, it didn’t go well. I was anxious, severely depressed, and couldn’t get my mind off my creative work. Instead of studying, I was researching medically-safe materials, talking to parent support groups for medically complex kids, and sewing adaptive prototypes for families to test out. This work brought me enough joy to get me out of bed in the morning, but every time I got to campus for class, I felt like I was in prison: totally understimulated, in a bleak, sterile environment, and wearing an uncomfortable “business professional” uniform.

During this time, I also became more and more involved in the growing online disability community. I had formed friendships across the world with other neurodivergent and disabled activists, and I began to hear more and more about the near-universal experience of medical gaslighting and other medical trauma, including PTSD. I collected stories of physicians and the healthcare system repeatedly, and almost predictably, failing their most vulnerable patients. I have friends who’ve been thrown around from specialist to specialist with no physical improvement, friends who have been fired by their doctors for “being too complicated,” friends who have been denied care because they are fat. But when I inquired about what physicians are doing to address these significant issues, I found nothing. When I brought up the phrase “medical gaslighting” to my physician parents, they had never heard it before. When I looked at online medical journals to see who was researching these issues, there was next to nothing. I thought, “Why is no one listening? Why doesn’t the medical community care?”

17

I was angry and disheartened, and became increasingly disenchanted with pursuing a career in such a fucked-up system. I felt like the work I was doing through Abilitee was making a difference. It felt meaningful, impactful, and much-needed. I heard how the g-tube pads I designed were reducing the incidence of accidental tube pull-outs in babies, which prevented excessive hospital readmissions. I heard of someone’s grandpa, who smiled for the first time since his colostomy surgery, after being gifted one of our “OH SHIT”emblazoned Ostomy Covers. And after our Insulin Pump Belts were released on aerie.com, as part of their first ever collaboration with an adaptive accessories brand, I read social media comments from Type 1 Diabetics around the world stating things like “This changes everything! I never thought I would feel so seen and supported by such a big mainstream fashion brand.” By then, I knew this was what I wanted to do with my life, at least for the next few years. So, I dropped out of medical school.

And then COVID-19 struck the world, and my life, like an asteroid. At work, we took extreme precautions, requiring our 8person team to work from home, or visit the office in staggered shifts, for work like sewing or packing and shipping orders. We required masks in-office, and allowed only one or two people to be there at a time. Every time someone came and left, we asked that they sanitize all surfaces they touched in the common areas. Our team switched to meeting over zoom and by phone. It was an incredibly tough year. I was co-managing a team remotely, while working on my own projects for upwards of 80 hours per week. Years into the business, I still wasn’t taking a salary. I just wanted to get the work done, and wanted to make sure our team stayed employed. I became increasingly anxious and isolated. My

My usual routine and support systems began to fall apart, which exacerbated the chaos and upheaval, as it did for many autistic, neurodivergent, and disabled people. I was talking with friends and family less and less. My boyfriend, who worked remotely as an attorney, started visiting more frequently, staying with me for weeks at a time. Just us two and my dog, Archie, almost completely isolated from the outside world. That year is when the fighting, gaslighting, and emotional abuse began.

In the past, he had violent blowups when things didn’t go his way, but the violence was never directed at me. I remember, after college, when he received a lower LSAT score than he thought he deserved, he blew up into a fit of rage: throwing objects into the floor and walls. Crying and shouting at no one in particular. It shook me, but I didn’t feel as if I was in any real danger. Later, during COVID, that would change. There were many red flags like this throughout our ten-year relationship, but I didn’t see them, or I ignored them, or I explained them away. Now, looking back, I see them everywhere. My personal experience was invalidated and disregarded, constantly. I was pressured into being intimate, convinced it was my responsibility to make sure he was satisfied, and there was little to no consideration of my pleasure.

At the same time, a professional relationship with an older mentor figure became increasingly toxic. Though we only met in person a few times that year, we spoke on the phone often. We would argue about facts. She would use her status and degrees to demean me and diminish my skills, intelligence, and creativity. She would threaten my future, and I began to believe that she held the keys to my professional success. Many of our calls

19

ended with me on the floor, crying and pleading for the yelling to stop. I didn't understand why so many of our conversations went in this direction. To make things worse, my boyfriend grew increasingly jealous of my time spent on work, furthering my career, and speaking with friends in the online disability community. So much so, that by mid-2020 I was not allowed to bring those things up in conversation. In the evenings, if I tried to share something about work, or talk about a conversation I had with a friend that day, he would get angry with me. I began to feel, more and more, that there wasn’t – and maybe hadn’t ever been – room for my “full self” in this relationship. The only version of me that was deemed "acceptable" was the version of me that tended to his physical and emotional needs above all else.

And then, Abilitee split apart. My former business partner, who funded the operation, went their own way. They started a new brand, and I kept the Abilitee name along with all of my research, designs, and ideas. But I was in a horrible place, mentally, emotionally, relationally, and physically. I had stopped taking care of myself, in nearly every way. I was doing what I could to feel safe from further abuse. I was self-medicating to cope. I was surviving, nothing more.

And things just kept getting worse. My boyfriend and I rented our first apartment together in a sketchy neighborhood of East Los Angeles. We didn’t have a yard, and I couldn’t walk my dog around the block at night without worrying for my safety. Everything in LA was still closed down. We both worked from home. He would be on the phone all day, talking to clients, his voice echoing through the apartment for hours on end. The neighborhood was loud,

too: there was constant commotion in the apartment complex, police and fire truck sirens blaring every other hour. At least once a week, helicopters boomed through the night sky, circling the area with spotlights and looking for suspects on the run. One night, around 2am, I heard gunshots nearby. For the next two hours, I watched as our street lit up with police lights, a crime scene was taped off, neighbors would be interviewed, and an ambulance came and left. I couldn’t escape the noise. It was sensory hell.

We started fighting more. He started screaming louder. Stalking me around the apartment, looming over me while tearing me down. I grew more and more confused and disoriented in my relationship, which affected my grasp on reality and the outside world. I had many meltdowns that year. My emotions were everywhere. I was so overwhelmed. I stopped achieving any level of productivity in my work, and we missed several of target re-launch dates for Abilitee. My life felt completely out of control. I felt worthless – like I was letting everyone down, including myself. And then, towards the end of 2021, right as our apartment lease was about to expire, I got dumped, and it sent me reeling.

Confused, terrified, hopeless, helpless, traumatized, I went home to Texas. With no one left in Los Angeles, it just made sense. My dad helped me pack up my life in California. At 30 years old, I moved back into my childhood bedroom. There, for the first time, I was forced to confront everything that had been my world and my life for the past 30 years. Because, clearly, it wasn’t working. Everything had to change. And for me, the first step forward in this process of healing, was figuring out how the fuck I ended up here.

20

Butterflies&Goo

As children, we learn that caterpillars become butterflies through a transformative process known as metamorphosis. When it’s ready, a caterpillar finds a nice little spot to park itself on a twig, where it builds a protective chrysalis around its entire body. Days to weeks later, the chrysalis breaks open, and a fully-formed butterfly emerges. But only relatively recently did scientists discover what happens in-between. As a child, I believed that – over time – the caterpillar would sprout the legs, wings, antennae, and other morphological structures we observe in fully-formed butterflies. Many people thought this. But that’s not what happens at all. Before a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, its body releases enzymes into the enclosed chrysalis, which effectively digests (i.e. disintegrates) itself until the insect becomes an unrecognizable glob of goo – something slimy and gross that resembles neither a caterpillar nor a butterfly. And yet somehow, as the process continues, the molecules that make up this goo figure out how to reassemble themselves in an entirely new, incredibly beautiful way. A butterfly forms, like a phoenix rising from the ashes. It seems magical, but it’s simply part of their programming. And the most wonderful thing – I believe – is that we are like this, too.

Just like caterpillars, I believe that children possess an innate wisdom about who they are and what they can become. And with the right nutrients, environment, and support, a beautiful future can be made possible. But unfortunately, for so many of us – especially for those of us who are queer, disabled, neurodivergent, nonwhite, or from any other marginalized community – we don’t always get that support. We’re taught to suppress and

fight that inner wisdom and our understanding of our own wholeness by a society that continually, violently chooses to do the same.

Growing up, I always felt different. And others’ reactions to my tiny bursts of authentic self-expression confirmed this for me, over and over and over again. I would ask questions for clarification, when I really wanted to understand something; I would share unique takes on things, perspectives others hadn’t considered; I would wear something that felt affirming of my identity; I would come at a problem or challenge from a very different direction. And the world told me “no,” over and over. “It doesn’t work that way. Why are you making things more complicated than they need to be? Why are you asking so many questions when everyone else seems satisfied?”

So, as I got older, I learned to bypass my own internal compass. Clearly, my needs were wrong. Clearly, I didn’t know what was best for me. (/s) So I looked everywhere but inwards for validation and acceptance. Instead of trusting my own instincts, I spent an incredible amount of energy observing and analyzing everyone else. I absorbed everything everyone around me was doing – what other kids talked about, what they wore, what made them laugh, what movies they watched on weekends, what their parents put in their lunchboxes. And I tried my best to be like them. There was safety in “sameness.”

Masking became an armor for me. Every morning, from grade school through college, I put on my armor before leaving the house – carefully, intentionally, and painstakingly. I straightened my long wavy hair to look “less Mexican.” I learned to

22

camouflage my quirks – to hide any part of me that stood out “too much” in my wealthy white conservative neighborhood.

I fell in love with fashion the moment I was able to dress myself. To this day, one of my favorite activities is playing dress-up. Bright colors, soft fabrics, and beautiful shapes provide such satisfying sensory stimulation. Growing up with undiagnosed ADHD (a developmental disability) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (a chronic mental illness) meant I was constantly trying to keep up with those around me, without the proper support. I often found it difficult to express myself with words. Even when I knew what I wanted to say, social anxiety got in the way. Fashion became a tool I relied on to communicate with the world it was a language I became proficient in very early on.

I grew up with specific options for how and who to be. How and whom to love. Which careers were “worthy” of my intelligence and economic class. Boxes offered to me by distracted adults. By celebrity role models, by friends’ parents, and by the opposite sex.

I learned it was my job to satisfy men. To make men comfortable, to make them look good – but never overshadow or outshine them. It was my job to keep others’ fragile egos intact (only it really wasn’t, but how was I supposed to know?). I learned to be pretty, but silent. To be accommodating. To manage others’ emotions especially men’s.

I thought I needed to land the most lucrative job to be a valuable human. I thought I needed to be popular. I needed to be not only accepted, but praised by those around me, as a means of determining my

own worth. But that just led me to stifle my individuality. My personhood. I watered myself down to meet others’ expectations of who I was and who I could be. I let others determine who I was allowed to be.

And for those of us who are lucky – I do feel I am lucky – maybe the goo is a necessary, unavoidable, uncomfortable stage, if we are to continue transforming into who we’ve really always been. The goo is part of the transformation. For me, everything had to fall apart, in such a catastrophic way that I became so unrecognizable to myself, that I would eventually be forced to stop, take inventory of all of my pieces, and start rebuilding my life anew.

I like the idea that I’ve been incubating, germinating, thinking, considering, making connections, identifying patterns, and integrating all of that learning into developing a better understanding of myself and how I might safely and authentically live in this world.

Out of necessity and curiosity, and with guidance from queer neurodivergent friends, I began to venture down many rabbit holes. I devoured everything I could learn about abuse, autism, and compulsive heterosexuality. Piece by piece, I interrogated everything I thought I knew about myself and the world around me. I began deprogramming the “good girl” mentality, and no longer placing others’ opinions about my life above my own.

23

“IntheworldthroughwhichI travel,Iamendlesslycreating myself.”–FrantzFanon

In many ways, I feel I have come full circle by meeting and embracing my childhood self again – who I was before all of this conditioning and societal pressure crusted over me like a cocoon.

Most importantly, I believe, I made the decision to simply begin this process of evolution. To me, this resurrection wasn’t about re-emerging as someone new, all at once, with all of my trauma healed and my future life figured out. I now understand that the process of metamorphosis isn’t about a sudden, fantastical transformation. It’s an entire lengthy process of unbecoming, of sitting in all of that goo, and then making the decision to trust my innate programming, as uncomfortable as that may feel, over and over again. Lasting transformation, in this way, is necessarily slow and deliberate.

It requires questioning everything: tearing down our internal systems and constructs, breaking our lives into a million little pieces, and then creatively, fearfully, forcefully, and optimistically piecing things back together in a way that is more in line with our inner selves and what we want to see in the world. We simply must begin. Again and again, as needed. And if we’re lucky enough to have the resources and support, and we choose to put in the work, we can build a better life for ourselves each time. And if we’re loud about it, I believe –I hope – we can build a better world for others, too.

In a similar vein, I believe the purpose of a studio is to serve a safe, nourishing home for those who wish to continue evolving and improving their lives and the world around them.

Through Futurekind Studio, I’m building a creative home for myself. But hoping to build a creative home for others as well. Art heals. Community heals. Design has the power to shape people’s lives, for better or worse. I’m happiest when I’m in my studio. Unstructured creative time. Or when I’m talking with others – ideating about what could be.

Even decorating the studio has become a process about taking ownership over and responsibility for loving and cherishing my own special interests, while building potential for others to come in and do the same.

FindingMyWings(Again)

Queer fashion is healing. For me, over the past year, fashion has played an incredibly significant role in my “becoming,” and at the same time, I often feel that I have spent much of this time revisiting who I was and what I loved to wear as a child.

Growing up in Austin, and away from my Mexican relatives, I tended to identify more with my white, “gringa” family and heritage. But interestingly enough, the times I spent immersed in Mexican culture were always more salient, more memorable. Only now, as I’ve begun to explore myself, my tastes, and my passions, have I come to understand how very deeply Mexican I am. As uncomfortable as it is to say, I always thought of my caucasian-American heritage as “boring,” and my Mexican heritage as exciting: warm, welcoming, vividly colorful, and something that set me apart from my peers. Different in a good way. Something I was proud of, even as a child. I saw this part of my history as a sign of strength and perseverance against all odds. From this

24

side of my family, I witnessed a shared emphasis on the experience and exploration of being alive: feeling, loving, cooking, eating, dancing, joking, kissing, singing, painting, creating.

In recent years, I had forgotten these things were a part of me. I deprived myself of all these things perhaps as a form of selfpunishment, for failing to meet the norms and expectations of the very non-Mexican community I lived in for most of my life. I had learned in so many ways, and from so many outside sources, that the meaning, purpose, and value of my life was my ability to achieve and produce. Not to feel, enjoy, love, or create.

I have such fond memories of visiting my Abuelita where she lived near the border. My siblings and I would stay with her, usually for a week at a time, during summer break. We’d cross the border to Matamoros, Mexico and spend hours with her at the small tuxedo and formal wear shop that she owned and ran. She was a skilled seamstress, and as I got older, I learned she was a talented artist as well. I believe I have her to thank for these wonderful gifts that I seem to have inherited. And the more I remember my visits to Mexico, and my time spent in her shop, the more I recognize how much of her life and culture I absorbed.

Now, as I am rediscovering my taste for vibrant, warm, saturated colors – compared to the cool blacks and grays and neutrals I wore for much of college – I am realizing how fondly I remember those times spent in the streets and markets of Matamoros, just wandering around as child and taking everything in: excited by the bright colors of traditional Mexican art and the textures and craftsmanship of the woven textiles that were everywhere. And I have certainly noticed, over the past year or so, how

wonderful, and light, and optimistic, and free I feel when I’m wrapped in clothing that gives me that same sense of comfort and awe and excitement that I felt as a child exploring the street markets of Mexico.

I think I understood very early on how color, shape, and design can change the way we interact with the world. When used thoughtfully, it can excite and inspire us –and now is such a ripe moment for using this to our advantage. Fashion, I believe, is an incredibly effective medium for changing cultural attitudes and encouraging social and political change.

Through Abilitee and Futurekind Studio, I want to help make the disability revolution irresistible: to make it visible, powerful, effective, authentic, relatable to use fashion to push for change. If I can help someone understand the importance of having clothing that fits different bodies and different modes of self-expression, then maybe that opens up the conversation to start thinking more comprehensively about disability inclusion and accessibility in other areas. I want to be part of a future where fashion is used to encourage and promote inclusivity, rather than exclusivity, as most of the industry does now. To me, such a future sounds much more interesting, challenging, and rich, with so much more room for all kinds of people to exist freely and joyfully and colorfully. I think it’s time for us to evolve. Will you join me in making the decision to begin? Not just now, but over, and over, and over again? ■

26

Iwanttobepartofafuture wherefashionisusedto encourageandpromote inclusivity,ratherthan exclusivity,asmostofthe industrydoesnow.

fat+furious

Three binders, two white and one hot pink. One is too small to even fit both tits. One day I decided that if someone takes issue with my chest, that’s sort of their problem. I bind on my own terms, which is to say, I’m not binding in triple digit Texas weather. I wear my REAL MEN HAVE TITS shirt with orgullo, and a little bit of fear.

Button ups! Every dyke needs them, yes? A blue and white striped one from the Old Navy outlet whose buttons don’t accommodate the existence of chests. A green and pink floral one from a random store in the same outlet whose buttons don’t accommodate the existence of chests. A navy blue one from Target two days before the funeral whose buttons don’t accommodate the existence of chests. A gray Star Wars one from the Plato’s Closet in Lubbock whose buttons don’t accommodate the existence of chests.

Too many Modern Baseball hoodies to count. Every era from Sports to Holy Ghost. Every color from green to gray to black. Procured from concerts before the band’s indefinite hiatus, and from Depop after it. The ultimate Dysphoria Hoodies for any closeted tboy 14 to 24.

28

crowdedcloset:crawlingtowards selflove sghuerta

Various artists’ merch. Specifically a white Kid Cudi t-shirt featuring an illustration of the artist wearing a wedding dress, smoking a joint, and flipping off the viewer. Before I met most of my chosen familia, I was hanging around a couple who were incredibly cis and incredibly prone to racial microaggressions. Neither of them responded to my excited texts about my favorite rapper wearing a dress on national television. !!! It was a huge deal for me to see an emo Mexican American man rocking a floral dress while singing and humming along to “Sad People.” Maybe I too can be sad and Mexican American and true to myself and masculine and wear floral things all at the same time. (I’d prefer to avoid national television though how could I stay authentic with so much outside input?) I wear the t-shirt when I need some of Cudi’s confidence.

Crop tops. I used to love wearing them to combat the summer heat when I was a teenage girl and sort of underweight. Now that I’m at my healthiest and heaviest, I only wear them at home or with chosen familia. Just because I love myself doesn’t mean the whole world will. I will wear one to the outdoor coffeeshop date anyways, though.

The mustard cardigan my father bought to match mine when I was in middle school. I wore mine for years over band tees and hand-me-downs and polo shirts to teach in until the armpits were a permanent overripe banana shade and the buttons no longer closed over my growing body. His fits me so snug now. I didn’t know he still had his until I was able to look through his clothes, two years after he left this world. We look so much alike now.

29

theglowup

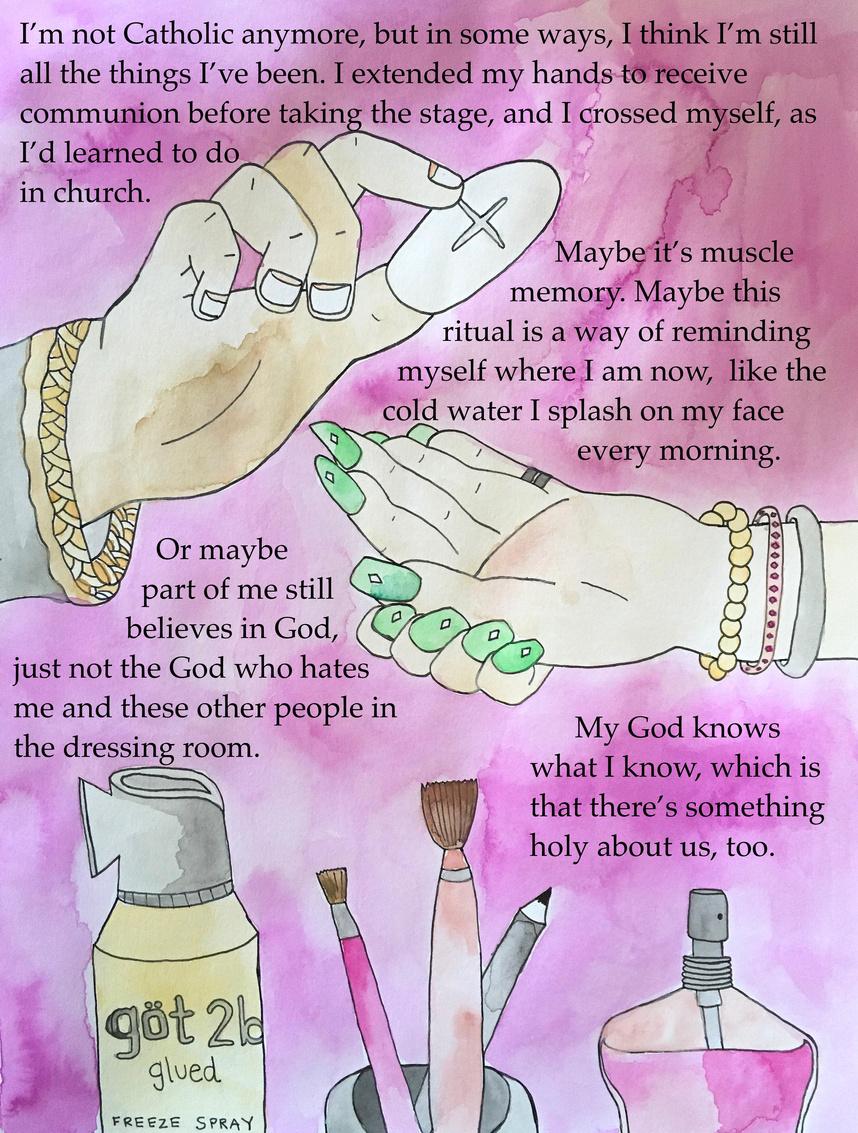

MANI-CUREforthenewlyassembled thankstovoguevoid alisonlubar

Secure an appropriate polish.* Lacquer, slick, still liquid. It will dry shiny. Do not drink. It does not taste like it looks. If your vision is monochromatic, any shade will do. Let the algorithm pick for you. Prepare the area. Refer to your assembly manual for compatible materials. Paint the tips of your appendages pink. Abalone, Bahama Sands, Cotton Candy, Skin InsideOut.

If you have one between your legs, make it blue. Cerulean, Chemtrail, Hyacinth, Robin’s Egg.

Choose any color for your tongue. Jazzberry, Ochre, Rust, Fire Engine. Wait for it to dry.

Speed up the process by heat or UV. Do not lick.**

Show it off!

Bedeck yourself with something to match. Or go naked. You have never eaten an apple to know any shame.

Let’s go, girls!***

*Not of a national origin. Not Polish. Also, “polish” is a misnomer. Do not take sandpaper to your tender metal. Buff with lambswool last. Each end is scorpion-sharp, or blunted and comforting like the end of a vintage Phillips-head. A cross to hex or bless. Anyone with nipples. Or not.

**Unless your tongue is made of light.

***As in Shania Twain. Not as in your accessories. Not as in anything physical. As in, even you have this sentience. Even if it’s binary or mere modem blips. Even the fragile carbonbased beings who will blink out even before they’ve chipped a nail. You’re alive enough to know for yourself.

1. a. b. 2. 3. a. b. 4. a. b. 5. a. b.

31

ashishkumarsingh

nailpolish

Desire was quieten by the unwanted shame and the nail polish I bought stayed for another week beneath the school books. The woman selling them looked at me as if I hadn’t asked for a product but stood soliciting sex like young girls on Red Road do. When she asked for what, I lied and said, it’s my sister’s birthday. Though I would have liked to try all the shades to see which suits my fingers the most, like my mother does each brushstroke carefully measured, I did not. In the end, I went for the red that shined with star glitters. My sister, if she were to see it, would’ve called it gaudy, red being the color that screams desperation. When walking all the way home, the bottle felt cold against the palm in the pocket of my trousers and guilt hot like the barrel of a gun pressed against the lungs. Weeks passed and it remained hidden like a stolen property until yesterday when I skipped school, settled in a corner of a park so far away it took almost an hour to get there. Tell me, what is the most daring thing a boy of 14 can do if not this stealing a moment to try to be someone else. I opened the bottle and the smell of my mother getting ready tingled my nose, her one hand extended towards me as I held a different bottle of the same colour, ready to show her the artist in me while the other near her maroon lips, blowing them to dry. I laid down, my ten digits spread on the green grass like ten red ladybirds, my face getting kissed in blotches by the afternoon sun. When getting late, I hurried, left myself asleep on the ground and like an exile finally returned home.

32

carapleym

thewayyoushouldalwayshave lovedyourself

The sharp edged feathers and cutting liner kills me.

It’s ferocity more than beauty but that’s what makes it stunning, in the truest sense of the word. It took my breath away.

I remember the first drag performance where I ended up doing improv on stage and it was so fucking freeing but I looked down at myself sadly with my twee day dresses and faded hair, what the fuck was I doing there amongst all that glamour and intoxicating glitter? The air was thick with it, embedding in my lungs like wings waiting to take flight.

It was another three years before I caught on fire, saw my skin as a canvas not for another but for a new identity. Every damn day if I wanted to.

I remember the first day I tried to leave the house with overdrawn lips and a shimmering cleavage, it’s ridiculous but I felt ashamed and small, I wasn’t big enough to pull this off. How could I dare to be loud with a voice so quiet from my trauma choked tongue? Then I watched her. Iconic, bold, unfiltered. How to be unafraid of the weight of her earrings?

Little did I know how a leaden choker could unlock my soul. How I could pour out a relentless kind of love with hair so perfectly wild, how could anyone deny her?

The first time I looked in the mirror and saw hope, it was cloaked in vicious black and harsh metallic, gothic and frantic and fucking beautiful.

I stole the ashes from my own urn and tossed them across my body, a reminder to create art from your very bones, sow your heartstrings into tapestries that play across your skin, tight and longing, the way you should have always loved yourself.

33

Content Warning: Includes mentions of suicide and gun violence

You bewitch me Theresa/Gia

That afternoon when my brother – cousin and I found red trails reconstructing – the last few moments in the kitchen – but that was not – where she shot herself in the bathroom – next to your makeup

Our love was unknown

I was a child And there was all too much abuse around us

Her powers limited but – extravagant – her tools eyelash curlers – a mirrored walk-in closet – replete with sequined gowns – Her firm knowledge of party drugs and 80's daytime television – a gunshot on Dynasty

old young Decadent! female male Who gives a shit!

She rode style for life – There was Studio 54 – beautiful but gay – a tongue – forefinger – up his ass – He’s yours! Try leather thongs – poppers – blue feather boas – pink plastic phalluses

Clip Vidal Sassoon hair advertisements – Wear v-shaped magenta dresses teased hair – rhinestones – below your breasts – a compass rose – in black and white shimmer – and red lips always red lips

on the path of interpreting post-traumatic stress disorder

34

myaunttheresa/mygiacarangi [killedherself–shevisitedthree timesaftershedied]

aubrythrelkeld

She needed blood – not suntan oil – mineral water – not predator prints just in time – for Falling – ill – It’s like it never happened – shooting – snorting up fucking your way to the top –She was on the cover of Vogue – once upon a time maybe a week – two she’ll get better – she won’t pass like this –not like this – alright – fine – She had Cosmo on the floor

After she passed she visited my bedroom three times and said everything must pass She was okay The hole in her head dark with oxidation a Kaposi’s sarcoma

35

themane attraction

reachoutandbrushfaith erikfuhrer

While shopping with my friend in a Glaswegian Salvation Army on a crisp late Spring day in 2009, I found a cute pink low-cut V-neck tunic stashed away in the electronics section of the store. The tunic reminded me of Link from The Legend of Zelda. Link was one of my og hotties and fashion faves. He knew how to walk through hearts so that the love soaked him in. And he thwapped his hair long around his shoulders. He knew the power of gold.

“You have the same fashion sense as a teenage girl,” my friend laughed when she saw me holding it against my body. I hated the shame that statements like this made me feel but a giddiness still galloped beneath Epona riding through the fire untouched while Link wore a sexy tunic unscathed, long hair flailing, unsinged. “Do you think it will fit?” I asked, too worried to bother the cashier to try it on after my friend’s reaction. She nodded, “yeah, if you want to look like a teenage girl, then sure.”

Teenage girl is a look I denied myself during my own teens. Afraid people would call me gay as I ached for bodies that looked like my own while wishing my own looked otherwise. Ultimately, it came down to hair. A lot of my life I wished I was a woman so I could float a fountain of Auburn locks down my back without having to explain them. They’d just be “normal.” Girls would braid each other’s hair in high school and I’d sit and sigh, wishing I could twirl my finger around my locks and join.

Whenever I tried to grow my hair out in high school it was viewed as “redneck.” I'd have to live in that problematic shell because living in the pearl of beauty felt too dangerous. Embarrassingly, I leaned into the “redneck” narrative and performatively eyed pick-up trucks while taking driver’s ed. I hated that I was reinforcing and propagating a stereotype but it felt safer than admitting that what I really wanted was a purple Volkswagen Cabriolet convertible so my hair could blow in the wind while I blasted Elton John on the radio.

37

I tried growing my hair long multiple times in high school. Eventually, I ended up in the chair. You don't have to be a man, I wish I could tell myself. Each fallen lock felt like dropped blood.

“It will grow back,” I’d be told. Sure, but who am I until then? “Does one day you will get to heaven” make waiting any easier for those who want to taste God? So was the Goddess within myself caught in the throat of limbo every shearing day.

Long hair didn't feel related to a gender, it felt like a resurrection. And now that it swings at my back, I am phoenixed into a new aura that spiders its light beyond a checkbox on an airwhite page, the sketch of me Pixared into a rainbow too bright to swallow.

“Long hair, like Samson!” I’d hear. That was one of the only approvals for my desire

That I'd grow into a brawny Biblical stud. But I didn't want to pull any pillars down. I wanted to soften. To ripen. And I also

wanted a beard. But only when it felt pretty. All the most beautiful fruits have some fuzz. Toss a Kiwi my way.

Listen, I’d whisper to myself, if I had another chance at my life. You can be beautiful in your own body and wear a tunic like Link. And wear a white dress like Buffy. Your body only has to ever look like your body. Whatever that looks like. Whatever that will look like. You are the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.

Let your hair down. Let it weep around you. If you drown the water will run from you and unfill your lungs. Like it did from Buffy. Like it has done many times from you when you thought you weren't going to survive.

Listen, I’d kiwi softly through my lips, these twenty years later, you are still here and your hair is long and you wear pink eyeshadow to parties and you carry your inhaler in a beautiful leather handbag.

38

Yourbodyonlyhastoever looklikeyourbody. Whateverthatlookslike. Whateverthatwilllooklike. Youarethemostbeautiful thingIhaveeverseen.

Listen, at your twenty year high school reunion you will scarf tie your way through the room and everyone will look. And this time you'll glitter out loud. Like a vampire in Twilight.

Only, my twenty year reunion is next month, and I’m not going because I know that I’d spark that room into a flame it couldn’t extinguish. Because I am now all the light that I was once eclipsed from. ***

I bought the pink tunic and wore it on a walk to my friend's house one early evening that summer. I pulled a light gray cardigan on top, despite the fact that Europe was going through a heat wave at the time. As I walked down busy Byres Road in Glasgow, I felt as if everyone was staring at me in disapproval of my shirt. Some people admittedly probably did, like my friend, hate my outfit, but my reaction obviously said a lot more about how self conscious I was in my own body than about what anyone was thinking about my outfit. I ended up buttoning up my cardigan, choosing sweat over shame.

I gave the shirt another attempt on my plane ride back to New York that September. It had been almost 9 months since I had cut my hair, and my curls and waves had started to drop closer to my shoulders than they ever had before. Even though the air conditioning on planes is always way too cold, I wore the tunic without any covering. I was Link in the tundras. I was closer to a version of myself that sparkled.

My grandmother hugged me tight at Newark Airport. Directly afterward, she frowned and said something to my mother in Swedish. My grandmother liked my hair short. “Handsome,” she’d say. I’d wince. She hated my longer hair. She tugged at it and frowned, “ you are so handsome honey, why do you make yourself look so stupid?” She was nothing if not blunt. Then she pulled at the string of my tunic and asked me whose shirt it was. “Mine,” I replied. She waved her hand in the air in disdain, “oh come on now, honey, it’s a girl’s shirt. Take it off.”

My grandmother in many ways was my real mother. My biological mother was too busy kicking me through metaphorical windows. The kicking was often not a metaphor. Only the windows. Except those I tried to escape through when she’d barricade the house from within. My mother is the reason I spent these past 3 years exercorcising onto the page trauma that could only be translated, let alone uttered, through the distance afforded by paratext and the safety of metaphor.

39

Now that my grandmother has passed, I realize that although my mother was often the one who pushed me, my grandmother was the one who kept placing me back by that goddamned window. I spent a typically violent couple of months living with my mother when I returned to New York complete with tantrums and attacks and the normal Fuhrer family fare. During that time, the tunic mysteriously disappeared from my closet. “I don’t know what shirt you are talking about,” my mom swore.

A year before my grandmother died, I started more openly identifying as nonbinary and wearing jewelry. I went to visit my family in New York that Christmas, 2019, for the last time, and my mother reluctantly gave me some of my grandmother’s costume jewelry, insisting I should be a “pretty man” rather than an “it or them or whatever.” At least she used the word pretty. I had to hold onto any positive moment or word with her. The jewelry did indeed make me feel pretty. A queen.

When I wear Mormor’s jewelry, I resurrect who I wished she was. I resurrect myself.

I have so many things to resurrect from.

I watch Michelle Pfeiffer fall out the window and get bitten by cats.

Selena, claw my face. The milk of me pours. How long until I feral my way out of this life and into the one that’s always been waiting for me?

God is there so much I am hoping she will block for me.

How many cat bites does it take to get into heaven?

Reach out and brush faith. ***

I moved to South Bend in May 2015 to attend a PhD program at The University of Notre Dame. During the interview process a few months earlier, my body positivity was high. I wore my hair in a top ponytail. It was very 80s/90s jazzercise video. Unfortunately, Notre Dame would rob me of this euphoria and I’m still rebuilding it. I did not feel comfortable wearing anything close to my pink tunic there. Within the first few days living in Indiana, I had lowered my ponytail and registered myself back into a “male” note. My long hair stayed and was actually praised but for different reasons that I desired.

“He is returning, praise God,” the clerk behind the counter at the Post Office exclaimed, her hand high in the air. Oh God, does this woman actually think I’m Jesus?

40

People had told me I looked like the iconic mass card and film versions of our apparent lord and savior before but this hysteria was a first. “Hi, I’d like to mail this to New York,” I told her. She processed the package, all while continuing to exclaim, “praise be to the lord his son has risen.”

Then, right before I left, “did anyone ever tell you you look just like Jesus? He’s coming back, you know.” I smiled, relieved that I wasn't in some nightmare version of “Revelations” and replied, “thanks, have a good day.”

I hate the Jesus reference. And most similar others I received. The first time someone said I looked like Jason Momoa, I was flattered. Now, it has also gotten old. It feels like both comments attach themselves to manliness. Perhaps that’s me adhering to a binary. Perhaps that’s me being unfair.

But I wish for once someone would say Sarah Michelle Gellar or Diane Keaton instead, or a “Girl, your hair is on point!”

Tori Amos sings, “We both know it was a girl, born in Bethlehem.” Perhaps it is her who I look like. And perhaps I just want someone to say to me, “You look like beautiful hair. You look like phoenix. You look as if Rapunzel would have tumbled down you.”

Is it a surprise that my favorite Addams family character is Cousin It? It must be soft in your world, cousin. A sauna. Total eclipse of the hair.

41

afrodisiac

Even as the sun beats down on me relentlessly, I refuse to give into the heat and enter one of the many identical barber shops I keep walking past. They all look the same. Thin, slightly faded wallpaper, one huge mirror covering half a wall (this would be impressive if they weren’t all so small), two leather chairs and calendars graced by various black celebrities spotting different haircuts. All I needed was two seconds to dismiss every barber shop I’ve refused to set foot in. I don’t want the cleanest shop, or the prettiest wallpaper. I don’t care if it’s Jamie Foxx, Obama or Will Smith on the calendars. What I need is really simple. I’m about to give up when I finally see it. The perfect barber shop for me. Empty, save for the barber and his tools of trade. I have no idea how I will react to seeing my hair fall to the floor for the first time and if for some reason my tears betray me, I’d rather the audience be limited.

The barber points to a black leather chair with tiny wheels facing a mirror. As I sit I allow myself one final glance at my hair. He wraps a clean white towel around my shoulders and asks me what I want. If I wasn’t pre-mourning my hair I’d giggle a little or at least blow air through my nose. What I want is to magically go back in time and stop myself from putting relaxer in my hair. I can’t be angry with the kinyozi for his phrasing. He couldn’t possibly have known that relaxing my hair for boarding school wouldn’t have made it any easier to take care of. What I’m here for, what I have been instructed to do, is trim my hair down to almost nothing. As I tell him, “trim it and leave only a little bit,” I can't help but notice the familiar sting of sadness starting to tap at my throat. The moment the words leave my lips I bite the flesh inside my cheeks and study my hands in my lap like my life depends on it. There are only so many knuckles and scars to look at but I’m determined to not raise my eyes until I have to.

43

davinmakokha

cottonballsforthelonelyfloor

I expected the razor to sound more awful. As my hair falls to the floor I try to imagine the Kinyozi’s face. Scrunched up in concentration or at ease performing the task mindlessly due to years of performing similar motions? The hair on the floor for now feels like a stranger’s. Too smooth, too straight, too silky. The only thing that looks familiar is the colour. So dark it puts the night and coal to shame. It’s a point of pride at this point. I hear the tinges of jealousy mixed in with admiration every time someone says, “Your hair is so black!” I have something desirable. People can look at me and find something attractive about me. “Is that short enough?” the barber pulls me back to reality. I am scared a boy will be staring back at me when I glance in the mirror. Afraid that without my hair as a shield, a distraction, my ugliness will finally be brought to everyone’s attention. But the barber doesn’t know all that and that somehow makes looking in the mirror easier. He stopped at the growth so there’s a mini afro left. My features are more prominent in a way that makes me want to curse whoever invented mirrors. I hope they are in the hotter tiers of hell. The mini afro still won’t do. “Shave off a bit more.” This time I watch. I want to say goodbye. This is hair I recognise. It's mine. I have watched hair dressers bite their lip before they even touch it and felt them warm up to it. It falls like tiny black cotton balls and I have to go back to biting the insides of my cheeks before I request to have them bagged so I can take them home. I hate my face, I hate my head, I hate how powerless I feel and I despise the entire world. When the barber is done cleaning up my head I press his money into his hand, thank him because it’s not really his fault I have turned into this ugly creature and practically flee his shop.

Logically, I know nobody cares about anyone in the streets. Unfortunately for me, however, my skin cannot stop tingling. I feel exposed and even though I am trying to convince myself otherwise, I cannot shake the feeling that everyone is staring and whispering around me. I feel that way for months. At school with other students, in church, at the market… Every time I have to go back to the barber I mourn. I grieve the loss of my beauty. My heart suffers over the thought that other girls do not consider me one of their own anymore. I torture myself over the loss of my shield. There is nothing to frame my face with. My veil is gone, leaving me feeling vulnerable and exposed. Until now my identity has been tied with my hair. Having hair made me feel like I had a right to claim femininity. I may not have been good at taking care of it but at least having it made me less awkward among girls. Without it I have very few things left to grasp at my femininity. I dwarf nearly every girl my age and my face is too sour. In the future it will be just hair but for now I grieve until I am empty.

By the time I can grow my hair again I have given up on being seen as feminine. Other than the fact that it takes too much to feel woman enough, I have forced myself to look at my face in the mirror so much I have decided it’s enough that I am just me for now and each day after. My hair’s blackness is at the bottom of my priorities as I experiment with different colours. At first, I was scared of losing my hair again but I figured then I could grow it back. Now that I have the choice I feel I could cut it without having to fight down tears. I like my bushy decent-sized afro but I have become a person who can live without it, thanks to the many times I allowed myself to grieve. Whatever version of my mane I have to live with, I am ready.■

44

noscrubs

themaskasfashionaccessory dandy-liacco

In Metro Manila, masks are no longer required in most contexts. However, as Lolita, Ouji, and Aristocrat fashion enthusiast, I still like to incorporate masks into my outfits.

Lolita is a street fashion developed in Japan, which takes inspiration from Victorian and Rococo fashion, and utilizes plenty of accessories to create detailed, coordinated looks known as “coords.”

Ouji (also known as boystyle) is the masculine counterpart to Lolita. With shorts or pants rather than the bell-shaped or A-line skirts of Lolita, Oujis dress to evoke the look of a young prince. A more mature masculine look (such as the one in black photographed above) would fall under the Aristocrat J-fashion style.

One of the most important principles in this family of styles is coordination. The colors and motifs in a coord should play well with and complement each other, such that each individual element in an outfit looks like it belongs to the greater whole.

Through this approach, the mask is another instrument I can write a part for in the symphony of my outfit. So rather than interrupting the flow of the music, the mask harmonizes with the rest of the ensemble.

46

One of the things I enjoy about Lolita and related styles is how I can build my wardrobe over time, reusing clothes and accessories in new ensembles. As I add pieces to my collection, I can return to concepts and themes from coords that I enjoyed and tackle them again with more experience and skill. When it comes to accessories in Lolita, more is more. Going “ over the top,” or OTT with accessories is a valid way to wear Lolita.

It’s also acceptable to find uses for accessories outside of their intended purpose. This mold-breaking use of accessories is such a staple in the community that designers in this space build versatility into their pieces.

For example, the rose corsage made by Filipino designer Fancy Moi has both a hair clip and a safety pin on the back. This allows me to wear it in my hair, pinned to my lapel or hat, or numerous other creative ways I may yet discover.

47

On the Metro Manila transit system, where masks are required, mask chains and mask cords are a common sight. They allow one to take off their mask without needing to stow it away.

I wanted to try incorporating mask chains into my coords. However, I couldn’t find ones that suited my aesthetic. So I decided to design my own.

I first started designing and selling jewelry back in 2015. I named my shop GleamTrove, in theme with the fantasyinspired designs of the shop’s offerings. I primarily sold my jewelry at pop-up events in Metro Manila, such as conventions and bazaars.

Since what inspired my personal fashion also inspired GleamTrove’s designs, I also found customers among my friends in the Philippine Gothic and Lolita community.

In 2020, when the pandemic began, GleamTrove went dormant. It wasn’t until conventions started happening again in 2022 that I began to revive my brand.

48

Themaskisanother instrumentIcanwritea partforinthesymphony ofmyoutfit.

These large clasps are detachable they connect to the mask chain at the smaller lobster claw clasps, and the mask chains can be used with just these smaller clasps. I also made designs in pride flag colors. As a nonbinary person myself, a mask chain in my pride flag’s colors was one of my first prototypes.

I’m hopeful about finding customers for my mask chains at the local Lolita fashion convention, Lace Up, and at Metro Manila Pride. I’m also making my mask chains available online, through GleamTrove’s Instagram (@gleamtrove).

Like a thoughtfully-chosen mask, a mask chain can add color and interest to an outfit. It can tie disparate elements together, or carry a motif. These accessories can be more than just practical necessities they can be objects of beauty, and avenues of creativity and self-expression.

49

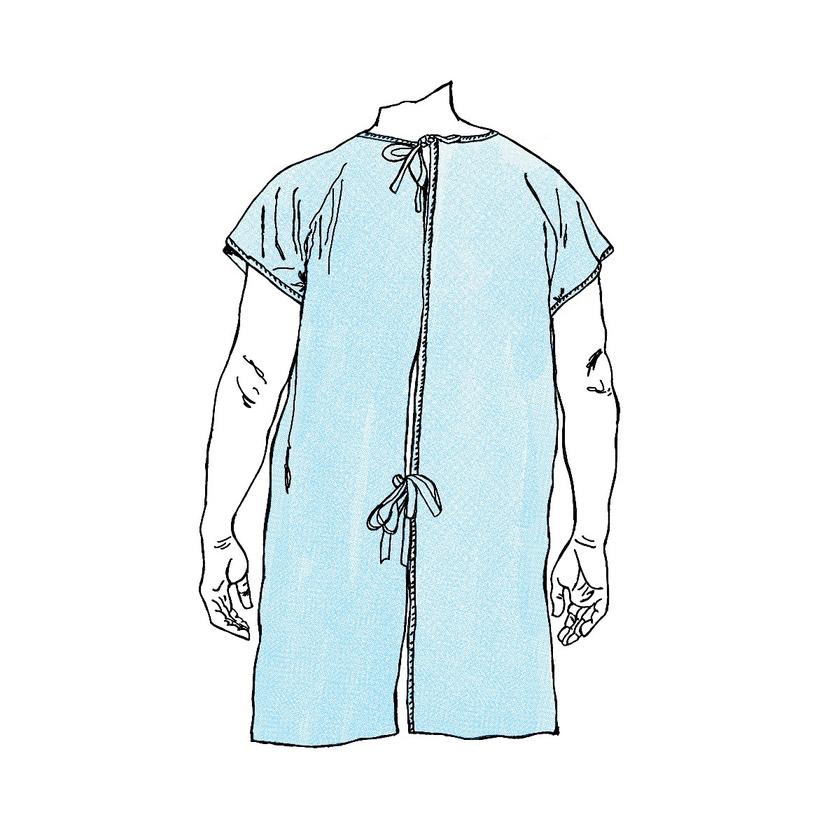

illustrationsbyjodavis-mcelligatt

room448B ethanwood

Trigger Warning: This piece makes reference to suicide and suicidality.

For a brief, final moment, my sleeping body’s only companion is the dim, orange light filtering in through the tinted wall-length window from the parking lot four floors below. It faintly illuminates the pale blue walls: the one to my right fitted with a mounted TV a black window to nowhere, and the wall in front of me, with two separate shelf-like protrusions, one of which holds the sparse amounts of zipper-less, string-less clothing I was allowed and a paperback copy of Calypso by David Sedaris. On the tile floor beside my bed, Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney rests—the cover curves slightly upward. From my peaceful corner on the left side of the room, I wasn’t able to see the large, wooden door, how it sits slightly ajar, or how it opens as three bodies enter one of them you.

Your entrance is loud enough this environment still new enough to wake me despite the 25mg of trazodone I’d been given earlier that night in a tiny, white paper cup. Two orderlies escort you in along with a rolling blood pressure monitor. My brain barely registers your stray “Don’t wanna wake him,” before one of the orderlies gently touches my shoulder, says, “We’re just bringing in your roommate. Try to go back to sleep.” They sit you on the bed, or rather, the big, blue brick bolted to the floor fitted with a thin white mattress, thin white sheets, and not-the-worst white pillows.

Framed by the fluorescent lighting forcing itself through the doorway, yet shadowed by the orderlies, your blood pressure is taken, the cuff loudly inflating, crinkling as it tightens around your arm. After a full day here, I’ve become familiar with the sound. It’s part of my new routine.

Through slit eyes, I can tell by your dark silhouette that you’re a grown-ass man. Not ideal. As the orderlies tend to you, I roll over onto my stomach, putting pressure on the shallow cuts on my left hip. They don’t sting as much as they did yesterday.

51

Thanks to the trazodone, it doesn’t take long for me to fall back to sleep. Thanks to whatever pain it is you’re feeling, it doesn’t take long for you to wake me up again when the scrubs come back in to give you some Tylenol. I fall into some semblance of slumber, but a part of me wakes every time you stir on the other side of the room. You’re a stranger in this space that was solely mine for almost 24 hours. But it’s not just your anonymity, your involuntary intrusion, that’s keeping me alert. It’s your masculinity.

When Chance, the super tall orderly with glasses, wakes me up, the sun is brightly shining through the window-wall. I look across the room to where you’re lying. Only a tuft of dark hair is visible, peeking out of the lump of white sheets. Chance crouches down and hands me two paper cups one pills, one water—as he tells me your name and asks me to notify anyone if I’m ever uncomfortable so they can make other arrangements. I nod, smile. Then he hands me a pen and paper and has me circle, between two options, what I want for breakfast, lunch, and dinner today.

After enjoying a splendid breakfast consisting of a soggy pancake, and an orange and apple juice that comes in what is essentially a pudding cup, I get my blood pressure taken and attend the first group therapy session of the day. Later, when I return to our room, hoping you’re still asleep. I push open the wooden door and step as silently as my grippy-socked feet can. I set a green folder containing papers full of exercises (identifying feelings, grounding, etc.) from group sessions on the floor beside my bed. I start to reach for the Rooney paperback but stop when I realize I need to pee. My only option is the toilet in

our poor excuse for a bathroom only a cheap, blue curtain separates it from the rest of the closet-sized space. This wouldn’t be a huge deal if it weren’t for the toilet’s ridiculously high-powered flush and the fact that I need you to stay asleep so I don’t have to interact with you. And yet: pee I must. I slip past the curtain lamenting the lack of one for the shower and piss as silently as I can, avoiding the water and hitting only the side of the bowl. Staring at the toilet, I debate whether to flush it, but instead do the next best thing and push the toilet’s handle down as slowly as I can, hoping against hope to reduce the sound. My ears are still met with a sonic expulsion of water. I hope to God you’re still unconscious.

I slip past the curtain again, and elect not to wash my hands because I’m not about to take another chance. The Rooney with its yellow cover lays on the white sheets. I’m about to grab it when you stir behind me, and the sound of your voice hits the base of my skull.

“Hey, sorry if I woke you up last night.”

My blood freezes. Not only do I now have to talk to you, I have to do so with the knowledge that you know I didn’t wash my hands after using the toilet. I grab the book and turn to see your face clearly for the first time. Your dark stubble has started to gray at your chin. You’re clutching the sheets around yourself, laying on your side, hands tucked under your chin, almost childlike. My hands thumb the pages of my book back and forth, back and forth. In the single second I look at you, I take note of your brown eyes, thick brows, and tan skin.

“Oh, don’t worry about it,” I say, eyes shifty, unable to maintain contact even in regular conversation with people I know.

52

***

You rub your face, and it’s then I see the gauze wrapped around your wrist. I avert my eyes and step to walk away, but you roll onto your back and ask, “What time is it?”

I’d check my phone and tell you exactly, but it’s sitting somewhere else in a manila envelope, along with my wallet probably in a drawer in some closet, filled with other peoples’ phones and wallets. That is, if they even had them when they came in.

“Uh, I think it’s close to like 10:30 or something.”