Chair Programs

Treasurer Membership

Editor Communications Meetup

Instagram Outings Outings

Chair Programs

Treasurer Membership

Editor Communications Meetup

Instagram Outings Outings

Joe Doherty

Susan Manley

Ed Ogawa

Joan Schipper

Joe Doherty

Velda Ruddock

Ed Ogawa

Joan Schipper

Joan Schipper

Alison Boyle

joedohertyphotography@gmail.com

SSNManley@yahoo.com

Ed5ogawa@angeles.sierraclub.org

JoanSchipper@ix.netcom.com

joedohertyphotography@gmail.com

vruddock.sccc@gmail.com

Ed5ogawa@angeles.sierraclub.org

JoanSchipper@ix.netcom.com

JoanSchipper@ix.netcom.com

AlisoniBoyle@icloud.com

Focal Points Magazine is a publication of the Sierra Club Camera Committee, Angeles Chapter. The Camera Committee is an activity group within the Angeles Chapter, which we support through the medium of photography. Our membership is not just from Southern California but is increasingly international.

Our goal is to show the natural beauty of our world, as well as areas of conservation concerns and social justice. We do this through sharing and promoting our photography and by helping and inspiring our members through presentations, demonstration, discussion, and outings.

We have members across the United States and overseas. For information about membership and/or to contribute to the magazine, please contact the editors or the membership chair listed above. Membership dues are $15 per year, and checks (payable to SCCC) can be mailed to: SCCC-Joan Schipper, 6100 Cashio Street, Los Angeles, CA 90035, or Venmo @CashioStreet, and be sure to include your name and contact info so Joan can reach you.

The magazine is published every other month. A call for submissions will be made one-month in advance via email, although submissions and proposals are welcome at any time. Member photographs should be resized to 3300 pixels, at a high export quality. They should also be jpg, in the sRGB color space.

Cover articles and features should be between 1000-2500 words, with 4-10 accompanying photographs. Reviews of shows, workshops, books, etc., should be between 500-1500 words.

Copyright: All photographs and writings in this magazine are owned by the photographers and writers who created them. They hold the copyrights and control all rights of reproduction and use. If you desire to license one, or to have a print made, contact the editor at joedohertyphotography@gmail.com, who will pass on your request, or see the author’s contact information in the Contributors section at the back of this issue.

https://angeles.sierraclub.org/camera_committee

https://www.instagram.com/sccameracommittee/

January/February 2025

A pact was made to stop the car at any time when one of the three friends wanted to take a shot. There would be no regrets about missing an opportunity to make a photograph on this trip.

By John Nilsson

Archival practices for the digital age are different than those for analog photography.

By Peter Bennett

25 Trip Report: Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve

By Joe Doherty

The fires of January 2025 incinerated my childhood. The church I grew up in, the canyons I hiked, the houses of my friends, and a library that had a very thin photography section all burned during the night of January 7-8. Our family had moved out in 1986, so we suffered no direct losses. The indirect losses were devastating, though.

The Palisades of my youth was an insular place, a village of families where there was never more than two degrees of separation between you and anyone you met on the street. Those ties became attenuated over time, but rarely broken. So it was unsurprising that many of us congregated on social media during the fire and in its aftermath. Many old friends were reunited.

I bring this up because, while we gathered online to share news, we stayed for the memories. And the memories with the most engagement were photographs from that earlier time.

During the COVID lockdown I occupied my time by digitizing film I shot from 1972 onward. I was using a flatbed scanner, and since it was as easy to scan six negatives as to scan one, I was indiscriminate. This was fortunate, because if I had stopped to consider the aesthetic, cultural, and technical value of each image I would have ignored most of them. To put this in darkroom terms, my scans were proofsheets, not prints.

Consequently, when the Palisades burned down, I was able to share a lot of images that held our spirits up. What I found remarkable is how a mundane photograph can spark so many memories of a place. It was, like the madeleine in Proust’s “À la recherche du temps perdu,” a trigger of buried memories. Yes, we lost many things to the fire, but the experiences we had are still within reach.

In this issue of the magazine we explore this idea twice. In the cover story, “The No Regrets Colorado Color Trip,” John Nilsson and friends return to the state where John grew up to photograph the seasonal changes of southwest Colorado. Some things were gone. The “quaint burg of granola-heads” that was once Telluride is now an enclave of wealth. But the surrounding landscape has remained the fascinating and everchanging land of his memories, and still worthy of taking out the camera.

Peter Bennett’s column is about the images of the old times. You might not have the backlog of film that I do, but most photographers I know have an archive of images from their youth, their family’s history, or their professional work. Well, what do we do with those now? Peter explains his very direct and focused approach.

If you are asking yourself, “why should I make an archive?” I offer my recent experience as case study number one. I picked up a camera because it was the best way for me to communicate my thoughts and ideas to others. That did not mean that they were ready to receive the message. What my recent experience tells me is that we never know when that time will come. That time did come for my hometown, and people I knew and people I have never met were receptive to a story that I was trying to tell 50 years ago.

In closing, January 2025 has been the longest and most stressful month in memory. I hope you are making connections with people who help you pull through it like I have.

Joe Doherty

February 13th at 7pm via

Pairing his fascination with wildlife and his passion for exploring wild places with others, Tim Irvin founded Wildlife Journeys – a wildlife tour company specializing in bears and wolves of the Great Bear Rainforest. Wildlife Journeys is proud to collaborate with Marven Robinson of the Gitga’ at First Nation.

Tim has worked as a wildlife guide and naturalist in British Columbia, Alaska and Manitoba. He is certified as a Level 3 bear viewing guide by the Commercial Bear Viewing Association of British Columbia. His expertise as a guide and natural history educator has helped three companies earn distinction as one of the “Best Adventure Travel Companies on Earth,” as named by National Geographic Adventure. His work with coastal grizzly bears has appeared on television in Terres d’Exploration, The Knowledge Network, and the award-winning series Michaela’s Wild Challenge.

Please register for this presentation at https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/ghDk6tahQcSeAxLYdzwb7A

Text

by John Nilsson

Photographs by Mike Caley, John Fisanotti, and John Nilsson

I grew up and lived in the Colorado mountains for over 60 years. During that time, I often found myself witnessing and inspired by the natural beauty of the state –especially the spectacular mountains and enchanting towns around Ouray.

One day last summer John Fisanotti and Michael Caley and I discussed going on a fall color road trip together. We are all SCCC members and fellow aficionados of aspen leaves in the fall. We had all been to the

Eastern Sierras for fall colors on several occasions and the question was raised:

Why not go to Southern Colorado this year? Enthusiasm ran rampant. The trip was planned to come off the first week in October.

My experience told me that we should use the small town of Ridgway as our home base due to its central location within an hour of some the most storied aspen enclaves in the state and less than one-half hour from Ouray. We were excited about shooting the colorful vistas

around the Dallas Divide, Owl Creek Pass and the back roads of the Uncompahgre National Forest. Silverton was a little over one hour away over the Million Dollar Highway and Telluride was the same on the other side of the Dallas Divide.

So on October 1 I rented a 4Runner from Enterprise, collected John and Michael in the La Canada/Flintridge area, and took off down the 210 with an eye at making the South Rim of the Grand Canyon by sunset.

A pact was made: There will be No Regrets on this trip. If any of us saw a worthy shot anywhere at any time, we would stop and shoot it. The pledge was meant to guarantee we would never find ourselves regretting “that we didn’t take that shot” – something that happens every photo trip. The pact was followed religiously.

As we pulled into the South Rim it became evident that we should have left LA an hour earlier as we were rapidly running out of daylight. This resulted in a very hurried, almost panicked attempt at finding a parking space in one of the first South Rim parking lots and rushing to the overlook – just in time.

Except in my rush to set up my camera and tripod I neglected to be certain the tripod connection was secure and my Sony a1 and brand new 50-400 lens hit the concrete walkway with a thud. One piece became two. Both were totaled before I had even taken a shot. After sufficiently deriding myself, I was able to get one shot off with my iPhone before the light was gone. Luckily John and Michael were able to add some beautiful sunsets to their portfolios.

Forrest Gump Point. Famous Monument Valley hilltop made famous by the movie Forrest Gump. Be careful when driving over the hill top, expect zoned-out photographers in the middle of the highway! © John Nilsson

When it became too dark to shoot. we inquired inside the park for a room for the night and were met with humorous, blank stares. “Tonight? There isn’t a room within 30 miles of here.” So off into the darkness we went, finally finding the last available room at Tuba City, AZ (83 miles away). Two single beds and a roll-away accommodated us and a laughably noisy air conditioner made the night seem longer than it should have! In addition, we discovered there was not a good meal to be begged in the Cameron area.

The next morning found us in Monument Valley at the View Hotel. I was rapidly getting back into the swing of long distance driving which I love. I’d much rather drive than ride. Both of my cohorts were approved to drive the 4Runner by the rental agency but I ended up driving most of the trip until the

last few days. The 4Runner proved well equipped for comfortable highway travel and amazed us on the 4-wheel drive sections we found with its unstoppable agility. This vehicle must be the perfect photo shoot ride –except for the 16 MPG!

The sky was flat and boring, so we spent only an hour or so in the area and took off for Ridgway – a good six hours away. We arrived just before sunset and got ourselves situated in our basecamp at the Palomino Motel for a 4night stay. The lodging was comfortable but a bit unusual, and the local food offerings, though limited, proved to be exceptional.

Early the next morning we were on our way up the Dallas Divide Highway (State Highway 62) to photograph the sunrise from ‘the iconic spot’ overlooking Ralph Lauren’s

Aspen Sunrise. Waiting for the sun to rise in near freezing temperature takes determination. We joined many dozens of other determined photographers that first morning. It was worth the wait and only motivated us more to drive up the county dirt roads for more color. © Mike Caley

ranch. As is the case since Instagram, we were joined by hundreds of our closest friends jockeying to get a vantage point.

It was immediately evident that we were about a week late in our quest. While the foliage that remained from the overlook was stunning, there were patches of bare aspens which a week before would have been in full glory. All three of us felt we had missed the absolute peak of color when the aspens display a mixture of green and gold and are still holding on resolutely to their host trees. Bare aspens are a shade less appealing (sorry for the pun). Also, the previous week added a skimming of snow on the higher peaks, always

a nice accent, that was now gone. We wished we had the variety of light created by partly cloudy skies which always makes the aspen color pop. Our skies were absolute “Blue Bird” but….there were No Regrets with what we all captured.

As the sunrise passed into morning, we left the crowd and began investigating the side roads off 62. County Road (CR) 5, 7 and 9 are famous for Colorado Color shots in the Ridgway area and we had lots of company on the turnouts along all three roads. The dirt roads are public rights-of-way into and through the magnificent Ralph Lauren, Double RL Ranch which has been in the

County Road With Aspen. We actually pulled over for the shot of a distant peak through an opening in the late afternoon aspen. Not "seeing" what I had hoped for from the car I turned around and instead found a seductive curve in the road framed by the golden aspen. © Mike Caley

Aspen Glory. We headed up one of the county dirt roads into the mountains chasing the color. It kept getting better and better the further we drove until we came across this meadow. There was a simultaneous and unanimous "STOP". This road pretty well summed up the whole wonderful trip for all of us in Aspen Glory! © Mike Caley

Ouray. From Highway 550 heading south out of town, a turnout provides an aerial view of Ouray, Colorado. © John Fisanotti

Ralph Lauren family for over 40 years, and spans 17,000 acres of the most beautiful part of South-Western Colorado. We were grateful for the opportunity to share and shoot this superb subject!

Starting on CR9, we worked our way to CR7 and then CR5 over several days. We were not disappointed and found many exciting views to the southwest up canyons to spectacular peaks. Every frame seemed to be dominated by 14,000+ foot Mt. Sneffles, one of my favorite Colorado mountain subjects. I wish I knew the names of the surrounding peaks – as I once did – but time has erased that knowledge.

On the morning we visited CR 5 we found many dramatic “keepers”. While each of the CR’s had very special vantage points we all thought CR5 yielded the premium compositions. Michael and John were filling their cards with memorable shots of rugged peaks, blue sky, and valleys and meadows of aspen and scrub oak exploding with color.

I was relegated to my iPhone and one black and white camera as a result of my personal equipment disaster. I was finding a new respect for the abilities of the Apple iPhone 14 and I found myself amazed at the quality I was getting from my shots. I used the Lightroom mobile app on my iPhone to

No Aurora On October 5, 2024, we drove out to a dark location on Last Dollar Road and watched for an hour. This view is looking due north, was taken in hopes of capturing an aurora. If the aurora did appear, it wasn’t during our hour. © John Fisanotti

record the photos in Raw. While I prefer to use Lightroom Classic to process my photos, I have found it is useful to capture photos in the Lightroom mobile app which automatically records each photo to the Adobe Cloud, thereby protecting my work while in the field from potential loss. Photos that are in the Adobe Cloud are then easy to transfer to Lightroom Classic when I arrive home to my desktop setup. I’ve never felt the need to process photos on my iPhone in the field, but that procedure is available (although somewhat clunky) if you are so inclined. There were no regrets.

Each day we rose at 5:00 AM and retired at close to 11:00 PM. We enjoyed the fact that our centralized base in Ridgway allowed us to reach our first location every morning before sunrise. On all mornings we were within a ½

hour drive of our first set-up of the day, and it was a quick trip to get back to the motel for a meal and a quick nap when the light became harsh, before heading out for the afternoon/ evening shoot.

We were fortunate to meet up with Wiebe and Teri Gortmaker, fellow SCCC members who had trailered their Airstream to Ouray the second day of our visit. We combined experiences and photographic location knowledge to everyone’s benefit. In addition, we enjoyed some tremendous culinary experiences at the Gortmaker’s favorite watering holes and eateries in Ouray.

One evening, after a wonderful dinner at a local Ouray pub we shot some beautiful night photos of the town from an overlook on the Million Dollar Highway. We had heard that

Bookmatched Aspen. "No Regrets" meant we made a number of stops on the road and turned around for a photo someone saw. This pond on the side of the road was a perfect example. © Mike Caley

© John Fisanotti

Overlook. It is amazing how humans are drawn to precarious perches on the edge of high cliffs – like moths to a candle! An enthusiastic tourist demonstrates her bravery at the Horseshoe Bend Overlook. © John Nilsson

it might be possible to see the Aurora Borealis that evening so we also relocated to a high and lonely spot just off 62 and waited late into the night for it appearance. No luck - but we did get some spectacular dark sky shots to make it all worthwhile.

A highlight of the second day was a quick trip to Chimney Rock up Owl Creek Pass. This location has been the set for several famous western movies and offered an awesome view of the rock formation and delightful aspen meadows at its base. The entire Ouray/ Ridgway area is prominent in the John Wayne version of the movie True Grit, and the meadow below Chimney Rock is the location of the famous final gunfight on horseback.

On our third day we trekked down the Last Dollar Highway, a gravel and dirt road that leads to Telluride. We were treated to spectacular aspen views and inspiring vistas to the west and south. The town of Telluride, however, was a distinct disappointment. I had remembered it as a charming and quaint burg of granola-heads from my previous visits in the 80s and 90s. Today it is a rather nauseating display of ostentatious wealth and privilege. We decided it is not worth a return trip. So back to Ouray for more great food and a trip to the top of the Million Dollar Highway (also known as Red Mountain Pass) and several extreme off-road adventures with Wiebe and Teri.

Antelope Canyon On a visit to Lower Antelope Canyon, with local guides, it was rare to get a picture without people in the view. Tripods aren’t allowed so one must shoot hand held at high ISO then clean up the noise. © John Fisanotti

“Lady of the Wind.” Fabulous formation in Lower Antelope Canyon. There are many such formations in the sandstone that have been named by canyon guides. © John Nilsson

Having been smitten by the beauty of Red Mountain Pass, we decided on our last day to complete the entire trip along Million Dollar Highway to the old mining town of Silverton. On the downside of the pass, and remembering our No Regrets pledge, we pulled over to the side of the road to find out why so many cars had stopped on the apron. A breathless tourist from Kansas told us that “there was a huge elk in the meadow!”

The elk turned out to be a massive bull moose who ambled through our camera lenses for almost an hour going who knows where. This was the biggest moose I have ever witnessed, a real treat that made me wish for the 500mm lens that lay smashed in my camera bag. Silverton turned out to be a rare treat. The town has remained much like it has always been, spurning the influence of money that

has ruined Telluride. The magnificent fall afternoon weather was a great accent for a couple of beers on Main Street and a walk through Colorado mountain yesteryear. We all agreed that we would go back to Silverton in an instant!

It had unfortunately become time to head back home. Once again, our No Regrets pledge commanded that we hit Lower Antelope Canyon and Horseshoe Bend near Page, Arizona, and do it all in one day. We enjoyed an early afternoon tour of Antelope Canyon and made the quick trip to the Horseshoe Bend Overlook just in time for sunset. Both experiences were outrageously memorable. Many great photos were added to our portfolios. The experience was a great cap to a wonderful trip and upon pulling into LA we all agreed that there had been No Regrets.

If you're like me, you've probably spent some time thinking about—or even worrying about—how to preserve your photo archive, essentially your life's work.

Over the past few years, I’ve worked with families to help them preserve and archive their photos and family history. As a photographer concerned with my own professional legacy, it occurred to me that others might have similar questions about preserving their professional or artistic photographic archives.

If you are of a certain age, your photographic career probably spans both analog and digital capture. Archiving prints, negatives, and other analog media has pretty set and specific guidelines that have been in place for years. The materials are readily available, and the biggest job is actually sorting through all your analog assets, editing them down, and then placing them in archival containers.

Digital archiving, however, presents new and uncertain challenges. Digital preservation is still in its infancy, with no universally accepted guidelines, raising many questions about how to safeguard your digital assets effectively.

Photographers are great at taking countless pictures but notoriously bad at organizing and preserving them. Consider Vivian Maier, whose work was discovered only after her death, languishing in boxes. It makes one wonder how many other photographers’ archives remain undiscovered and are lost forever. The first step to avoid this fate is committing to a consistent and dedicated

preservation process.

The first step in the preservation process is assessing your photo collection. What do you want your legacy to be?

It may not be realistic to think you can pass on your entire photographic archive in equal measure, but this is something you will need to decide. Unless you are a renowned photographer with an established body of collectible work, it may be best to take a more humble approach and decide what of your life’s work you wish to preserve and make available to others.

Ask yourself:

• What subjects or projects in your collection have enduring value?

• What might be of historical, educational, or personal interest?

• What represents your career and vision most effectively?

A well-curated collection that tells stories or highlights specific subjects of interest is more likely to endure, than a hodgepodge of work unified only by the fact that one person took all the photos. This doesn’t mean discarding everything outside these curated collections; you can pass on all your assets to a family member or legacy contact, as we’ll discuss later. However, prioritizing specific bodies of work increases opportunities for sharing, showcasing, and even placing them in historical archives.

I began my professional photography career in the 1980s, returning to my hometown of New York City and bartending at a neighborhood bar in the East Village/Lower East Side. This venue was a fairly notorious establishment that was on its way to becoming a kind of trendy meeting place in the middle of the burgeoning music/art/punk scene. I had a front row seat to a very interesting menagerie of clientele, and it afforded me the opportunity to work at night and photograph these same neighborhood and offbeat denizens by day, mostly on Kodachrome slide film. Decades later, these vibrant images have garnered significant interest, such as gallery shows, and have been requested for use in books, articles, and films. They are also in the process of being preserved

in one, possibly two historical archives in New York City.

That was over 40 years ago, but starting in 2008 I began photographing the Los Angeles River, something that was never intended to be the long-term project it ended up being. I've taken thousands of photos documenting the recent history of the LA River, and those images have always been in demand for a variety of uses. As a body of work they made for a successful book in 2020 and they have started to make their way into a historical archive at a local renowned university.

I tell my photo students that it can be very hard to be aware of the historical context and importance that some of the photos we take at various points in our life and career may have, and that was certainly the case with me. It is often only through hindsight, and

beginning the archival process that we see the greater value in some of the work we did.

The point is these two bodies of work make up a small percentage of my greater body of work, but I deemed them to have some of the most value out of everything I've photographed. So they're finding homes and sparking interest, and as a photographer there's a great satisfaction in knowing people want to see my work and having them endure in the public arena.

Here are steps I suggest:

1. Collecting

• Create a list of all potential storage locations.

• Gather all your work from the various locations: boxes, file cabinets, computers, external hard drives, and cloud platforms.

2. Digitizing

• Scan your negatives, slides, and prints. Begin with specific projects or bodies of work with the most archival value.

3. Curating

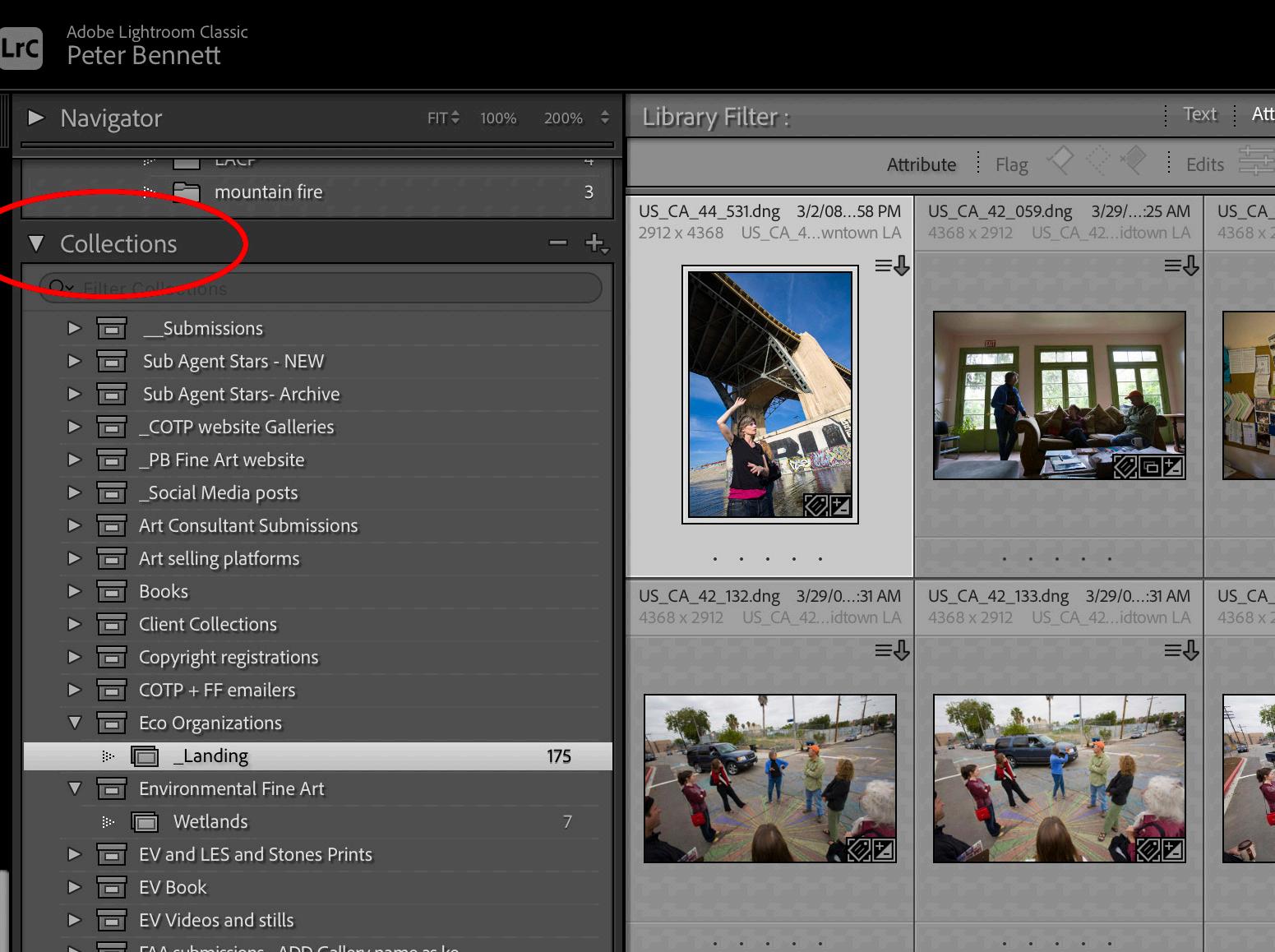

• Use catalog software like Lightroom to organize and curate your images. Create virtual Collections or Albums to help sort and refine your work without altering original file locations.

• Focus on creating identifiable bodies of work that tell cohesive stories or highlight key subjects.

4. Creating

• Create different ways of showcasing these curated bodies of work, such as books, shows, or other mediums.

5. Archiving

• Use archival-quality materials for analog assets and ensure digital files are stored redundantly (e.g., multiple hard drives and cloud storage).

6. Succession

• Identify a legacy contact or family member to help manage your archive. Consider placing significant works in historical or institutional archives.

Collecting all your work can either be a big task or a relatively easy one, depending on how organized you’ve been up to this point. Let’s assume, like many of us, your materials are scattered across boxes, hard drives, and perhaps even storage units. This state of disarray often contributes to the anxiety we feel when contemplating this process. However, taking small steps will help to alleviate that anxiety and clarify your path forward.

Start by making a list of all the potential locations where your work might be stored. Your analog assets could include negatives, slides, and prints. For now, we’ll focus solely on still photography and leave video and film out of the discussion.

You might find some of your analog work stored in non-archival containers. While it’s fine to leave them in their current state for now, prioritize moving any materials at immediate risk into safer storage.

Most of your digital files will likely be on your computer and external hard drives.

Other images may reside on old SD cards or cloud platforms where you previously uploaded them. Don’t forget about images on your phone, as well as older phones, hard drives, or computers you no longer use. Accessing these older devices may require specific cables or adapters, so plan accordingly.

Organizing a digital collection is never a simple thing, there can be a lot of steps to it such as de-duping and organizing folders, way too much to get into for this short article. I would say your best bet is to import all your digital assets and whatever folders they are in, into a catalog such as Lightroom or whatever else you're comfortable with or currently using.

The desktop version of Apple Photos can work, it has a cloud component but also local versions of your files. But make sure you understand how to work with the program, as it is more designed for personal photo use as opposed the professional needs we require. You do want local access to all your full resolution images for this process, so I would stay away from Google Photos or Amazon Photos, which only have a cloud component to it, no local access.

Scanning and digitizing negatives, slides, and prints is a long-term project, so it’s not necessary to finish this process before beginning your preservation and archiving work. Instead, perhaps focus first on digitizing specific projects or bodies of work that you consider most valuable or significant.

As you digitize your analog materials, add them to your larger digital collection and curate them into specific collections or series.

What you ultimately archive and pass on may mirror your existing photo catalog or library—or it may be a differently organized collection. For example, you might currently organize your images chronologically, by photography jobs, or by trips and locations. While these methods work for your current needs, they might not be ideal for an archive intended for others to understand.

Archiving requires that your work be organized in a way that future viewers can easily interpret. Organizing your images into identifiable bodies of work with clear explanations will help ensure their value and accessibility.

Use your catalog’s …Collections” or …Albums” features to help curate your images. These tools let you work with virtual copies, preserving your original files and folder structures. Later, you can choose whether to physically reorganize or export these images into different folders. For now, virtual copies offer the most efficient way to curate, cull, and organize your archive.

In the next article, we’ll explore the archiving and preservation process, including options for placing your work in existing historical archives or creating one yourself.

By Joe Doherty

On December 28th, 2024 fourteen photographers and birders joined a SCCC outing at the Sepulveda Basin Wilflife Reserve in Encino, CA. We gathered at 6am in total darkness for a three hour, three mile photowalk through the Reserve and the adjacent Los Angeles River.

A typical late-December morning on the pond would blanketed by a heavy fog, with the rising sun adding color to the sky before appearing as an orb on the horizon. On this day the weather was unusually warm and overcast. We saw little color, but as the sky brightened the shapes on the pond began to resolve themselves, and the activity of the birds increased. A light fog rose from the pond, adding some visual drama to the scene.

We observed a variety of birds at the pond, including Canada geese, egrets, great blue heron, night heron, green heron, cormorants, coots, and ducks of several types. Some of them were close enough to the shore to be photographs with short telephoto lenses, while others required a long reach. The Canada geese flew out in waves as the morning light grew brighter, pre-announcing lift-off with their incessant honking.

We walked past the pond and under Burbank Boulevard to the Los Angeles River, within view of the Sepulveda Dam Spillway. Upon our arrival a flight of Canada geese were on a path to land in the river, but a coyote burst from the bank in pursuit which required them to abort.

The black oaks near the summit of Liebre Mountain in the Angeles National Forest are noted for striking displays of fall color. I took these photos on a November 14 day hike.

Joe Doherty

Sunrise Sentinel on New Year’s Day in the Merced NationalWildlife Reserve.

After shooting fall color in Maine last October, we took the train back to Los Angeles with a four-day layover in Chicago. I experimented with slow shutter speeds and camera movement, including using a zoom, things I hadn’t tried much since the 1980s. My goal was to capture Chicago without distinct clues that it was Chicago.

Goosenecks of the San Juan: This is a Utah State Park, just north of Monument Valley. The image is a panoramic image stitched from two

Opposite page: Cacti and Oak. Detail in a side canyon in Navajo National Monument on an autumn morning. Valley of the Gods: This is a part of Bears Ears National Monument and, in places, rivals Monument Valley.

Navajo National Monument: Another panoramic image looking down canyon and across at the large ancestral cliff dwelling under the arch.

Fisher Towers: This formation is outside of Moab, Utah. The view is from the banks of the Colorado River.

The following images are from Highway 395 on a recent trip from Los Angeles up to Lake Tahoe and back. They were shot as in camera double exposures while my husband was driving. The camera was a Fuji XT2.

Happy New Year

In the quiet of morning

The first notes of day

Born and raised in New York City, Peter picked up his first camera and took his first darkroom class at the age of twelve.

Peter spent many years working as a travel photographer, and in 2000 started his own photo agency, Ambient Images. In 2015 he formed Citizen of the Planet, LLC, devoted exclusively to the distribution of his stories and photographs that focus on a variety of environmental subjects.

Peter’s editorial work has appeared in many publications including the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, Sunset Magazine, Los Angeles Magazine, and New York Magazine.

His prints hang in the California State Capitol, California Science Center’s permanent Ecosystem exhibit, and many other museums, private institutions, and collector’s homes.

He has also worked with a numerous local environmental organizations over the years including FoLAR (Friends of the LA River), The Sierra Club, Greenpeace, Heal the Bay, 5 Gyres Institute, Algalita Marine Research Foundation, Communities for a Better Environment, and the LA Conservation Corps.

Peter has been an instructor for over fifteen years at the Los Angeles Center of Photography, and for years led their Los Angeles River Photo Adventure tour.

Bonnie Blake is a fine art photographer based in Los Angeles with roots in Louisville, Kentucky and New York City. In contrast to her years collaborating as a motion picture camera operator on television, features and the TED talks, her still photography expresses her own observations about what, as Robert Adams wrote, “astonishes” her in the beauty of the natural world.

She uses a documentary approach as well as intentional camera movement to create traditional images as well as conceptual collages. Her belief that beauty can be an agent of change inspires her to express her concern about the destruction of these lands from climate change. She hopes to use her photography to propel action toward preserving these treasured places.

Her work has been exhibited at the Photo Place Gallery in Middlebury, Vermont, the Praxis Gallery in Minneapolis and the Duncan Miller Online

Gallery. She was awarded honorable mention in the 2020 Creative Portrait Exhibit at the Los Angeles Center of Photography. Currently she has a photograph in the Unbound12! Exhibit at the Candela Gallery in Richmond, Virginia.

Michael Caley was drawn to photography as a teenager, during backpacking trips to Yosemite, where he was inspired by the work of Ansel Adams. Today Michael’s dramatic landscape and wildlife photography are a natural extension of his long career as an architect and his many trips to the Eastern Sierras, Joshua Tree NP, the western United States and five trips to Africa. His work has been exhibited in several different venues including a 2010 solo exhibit at The G2 Gallery in Venice, CA. He can be reached at mcaleyaia@aol.com

Thomas Cloutier has been with SCCC since 2001, and he has been contributing to Focal Points Magazine since that time.

Cloutier’s interest in photography coincides with his interest in travel and giving representation to nature landscapes. His formal education in photography comes from CSU Long Beach. At present Cloutier is a volunteer at CSU, Long Beach where he taught Water Colors and Drawing at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI), designed for Seniors over 45. He also is a docent at Kleefield Contemporary Museum CSU Long Beach. He is Liaison for the Art And Design Departments for a scholarship program for students at CSU Long Beach, Fine Arts Affiliates, FineArtsAffiliates.org. Cloutier at cde45@verizon.net

Joe grew up in Los Angeles and developed his first roll of film in 1972. He has been a visual communicator ever since.

He spent his teens and twenties working in photography, most of it behind a camera as a freelance editorial shooter.

Joe switched careers when his son was born, earning a PhD in Political Science from UCLA. This led to an opportunity to run a research center at UCLA Law.

After retiring from UCLA in 2016, Joe did some consulting, but now he and his wife, Velda Ruddock, spend much of their time in the field, across the West, capturing the landscape. www.joedohertyphotography.com

John was a photography major in his first three years of college. He has used 35mm, 2-1/4 medium format and 4x5 view cameras. He worked briefly in a commercial photo laboratory.

In 1980, John pivoted from photography and began his 32-year career in public service. He worked for Redevelopment Agencies at four different Southern California cities.

After retiring from public service in 2012, John continued his photographic interests. He concentrates on outdoors, landscape, travel and astronomical images. Since 2018, he expanded his repertoire to include architectural and real estate photography.

John lives in La Crescenta and can be contacted at either: jfisanotti@sbcglobal.net or fisanottifotos@gmail.com

http://www.johnfisanottiphotography.com

http://www.architecturalphotosbyfisanotti.com

Larry used his first SLR camera in 1985 to document hikes in the local mountains. In fact, his first Sierra Club Camera Committee outing was a wildflower photo shoot in the Santa Monica Mountains led by Steve Cohen in 1991. Since then the SCCC has introduced him to many other scenic destinations, including the Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, the Gorman Hills, and Saddleback Butte State Park.

Larry’s own photography trips gradually expanded in scope over the years to include most of the western National Parks and National Monuments, with the Colorado Plateau becoming a personal favorite.

Photography took a backseat to Miller’s career during the 32+ years that he worked as a radar

systems engineer at Hughes Aircraft/Raytheon Company. Since retiring in 2013, he has been able to devote more time to developing his photographic skills. Experiencing and sharing the beauty of nature continues to be Larry’s primary motivation.

lemiller49@gmail.com

Bob grew up in Northern Orange County when there were more orange trees than people. He graduated from Cal State Fullerton in 1972 and Loyola Law School in 1975. In addition to his busy professional career, Bob is a Sierra Club outings leader with an M-rating and serves as the LTC Navigation Chair among positions.

John has a fond memory of his father dragging him to the Denver Museum of Natural History on a winter Sunday afternoon. His father had just purchased a Bosely 35mm camera and he had decided he desperately wanted to photograph one of the dioramas of several Seal Lions in a beautiful blue half-light of the Arctic winter. The photo required a tricky long exposure and the transparency his father showed him several weeks later was spectacular and mysterious to John’s young eyes. Although the demands of Medical School made this photo one of the first and last John’s Dad shot, at five years old the son was hooked.

The arrival of the digital age brought photography back to John as a conscious endeavor - first as a pastime enjoyed with friends who were also afflicted, and then as a practitioner of real estate and architectural photography during his 40 years as a real estate broker.

Since retiring and moving to Los Angeles, John continued his hobby as a nature and landscape photographer through active membership in the Sierra Club Angeles Chapter Camera Committee, as well as his vocation as a real estate photographer through his company Oz Images LA. The camera is now a tool for adventure!

www.OzImagesLA.com

Velda Ruddock

Creativity has always been important to Velda. She received her first Brownie camera for her twelfth birthday and can’t remember a time she’s been without a camera close at hand.

Velda studied social sciences and art, and later earned a Masters degree in Information and Library Science degree from San Jose State University. All of her jobs allowed her to be creative, entrepreneurial, and innovative. For the last 22 years of her research career she was Director of Intelligence for a global advertising and marketing agency. TBWA\Chiat\Day helped clients such as Apple, Nissan, Pepsi, Gatorade, Energizer, and many more, and she was considered a leader in her field.

During their time off, she and her husband, Joe Doherty, would travel, photographing family, events and locations. However, in 2011 they traveled to the Eastern Sierra for the fall colors, and although they didn’t realize it at the time, when the sun came up over Lake Sabrina, it was the start of them changing their careers. By 2016 Velda and Joe had both left their “day jobs,” and started traveling and shooting nature – big and small – extensively. Their four-wheeldrive popup camper allows them to go to areas a regular car can’t go and they were – and are –always looking for their next adventure. www.veldaruddock.com

VeldaRuddockPhotography@gmail.com

Rebecca Wilks

Photography has always been some kind of magic for Rebecca, from the alchemy of the darkroom in her teens… to the revelation of her first digital camera (a Sony Mavica, whose maximum file size was about 70KB)… to the new possibilities that come from her “tall tripod” (drone.)

Many years later, the camera still leads Rebecca to unique viewpoints and a meditative way to interact with nature, people, color, and emotion. The magic remains.

The natural world is Rebecca’s favorite subject, but she loves to experiment and to do cultural and portrait photography when she travels. Rebecca volunteers with Through Each Other’s Eyes, a nonprofit which creates cultural exchanges through photography, and enjoys

working with other favorite nonprofits, including her local Meals on Wheels program and Cooperative for Education, supporting literacy in Guatemala.

Rebecca’s work has been published in Arizona Highways Magazine, calendars, and books, as well as Budget Travel, Cowboys and Indians, Rotarian Magazines, and even Popular Woodworking.

She’s an MD, retired from the practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medical Acupuncture. She lives in the mountains of central Arizona with my husband and Gypsy, the Wonder Dog.