Focal Points

Decades’ Dream

Wyoming’s Cirque of the Towers

Chair Programs

Treasurer Membership

Editor Communications Meetup

Instagram Outings Outings

Wyoming’s Cirque of the Towers

Chair Programs

Treasurer Membership

Editor Communications Meetup

Instagram Outings Outings

Joe Doherty

Susan Manley

Ed Ogawa

Joan Schipper

Joe Doherty

Velda Ruddock

Ed Ogawa

Joan Schipper

Joan Schipper

Alison Boyle

joedohertyphotography@gmail.com

SSNManley@yahoo.com

Ed5ogawa@angeles.sierraclub.org

JoanSchipper@ix.netcom.com

joedohertyphotography@gmail.com

vruddock.sccc@gmail.com

Ed5ogawa@angeles.sierraclub.org

JoanSchipper@ix.netcom.com

JoanSchipper@ix.netcom.com

AlisoniBoyle@icloud.com

Focal Points Magazine is a publication of the Sierra Club Camera Committee, Angeles Chapter. The Camera Committee is an activity group within the Angeles Chapter, which we support through the medium of photography. Our membership is not just from Southern California but is increasingly international.

Our goal is to show the natural beauty of our world, as well as areas of conservation concerns and social justice. We do this through sharing and promoting our photography and by helping and inspiring our members through presentations, demonstration, discussion, and outings.

We have members across the United States and overseas. For information about membership and/or to contribute to the magazine, please contact the editors or the membership chair listed above. Membership dues are $15 per year, and checks (payable to SCCC) can be mailed to: SCCC-Joan Schipper, 6100 Cashio Street, Los Angeles, CA 90035, or Venmo @CashioStreet, and be sure to include your name and contact info so Joan can reach you.

The magazine is published every other month. A call for submissions will be made one-month in advance via email, although submissions and proposals are welcome at any time. Member photographs should be resized to 3300 pixels, at a high export quality. They should also be jpg, in the sRGB color space.

Cover articles and features should be between 1000-2500 words, with 4-10 accompanying photographs. Reviews of shows, workshops, books, etc., should be between 500-1500 words.

Copyright: All photographs and writings in this magazine are owned by the photographers and writers who created them. They hold the copyrights and control all rights of reproduction and use. If you desire to license one, or to have a print made, contact the editor at joedohertyphotography@gmail.com, who will pass on your request, or see the author’s contact information in the Contributors section at the back of this issue.

https://angeles.sierraclub.org/camera_committee

https://www.instagram.com/sccameracommittee/

My initial fascination with photography came from the magic of it. From loading the film to drying the print there was a world of possibility and variation. I strove for consistency but I also winged it a lot, experimenting with whatever technique was published in the latest issue of Petersen’s Photographic.

It also gave me an opportunity to see with greater clarity than I could without a camera. For many people the camera is a barrier between them and the world. I am fortunate that, for me, the camera is a portal. It heightens my experiences of encounters, events, and relationships, and then freezes them in silver on film or digits on my computer.

And photography gave me access to people, places, and events that were otherwise off-limits. My long-expired press credentials got me into the Olympics, past police lines, and into disaster areas. And my skills brought me into contact with a lot of interesting people, from writers to actors to politicians.

When I closed my business in 1990 I thought that was the end of it, but none of this is in the past. I’m still enthralled by the magic of photography. The camera is still a portal to the world. And I have all the access I need to my subjects, which are mostly public lands in remote areas.

All of these are present on the pages of this magazine. It is one thing to love a place, to put it on your bucket list, to spend years making repeat visits or just going one time. It is another

to witness it so lovingly that your photographs reflect the time and attention you think it deserves. Through our photographs others can witness these places as well. We create the narrative lens through which they experience it.

These are narratives. Thomas Loucks, in his cover story on the Cirque of the Towers, explains how his youthful love of hiking and camping led him to this place many decades later. His explanations would be less powerful in the absence of his photographs. One can feel the grandeur of the place, but also the work of the wranglers and the sense of time and travel.

John Fisanotti and Rebeccas Wilks bring us completely different narratives about the same corner of the world, the Grand Canyon. In the final installment of his Colorado River series, John tells us the importance of “know[ing] where to stand,” a mantra that assumes the photographer is taking a stance on what they see. Rebecca’s timely essay is about her lengthy personal relationship with the North Rim. Damaged by the massive and ongoing Dragon Bravo Fire, she laments that the lodge and the forests may not recover in her lifetime.

Peter Bennett brings us back to some of the basic mechanics of accessing your images in order to create your narrative. Where we once had file drawers of slide sheets, we now have Lightroom, the de facto database software for image storage. If you have ever misfiled anything, you know how important Peter’s five mistakes article can be.

August 14, 2025 at 7pm

Are your landscape photographs falling flat? While humans see the world in three dimensions, a photographer renders an image of a scene through our camera in only two. Not only do our cameras "see" differently than our eyes and brains do, but also our own eyes can deceive us: what we see and what we think we see doesn't always line up. If we understand how humans see depth, we can consciously create a sense of shape and dimension in our compositions. Join outdoor photographer/writer Colleen Miniuk for this insightful presentation to learn how to mindfully incorporate the three L’s (lines, layers, and light)—and even optical illusions!—that can help transform uninspiring arrangements into engaging expressive photographs. https://www.colleenminiuk.com/

Register here:

https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/xzh5CQe_ROOZZCrm65U9UQ

The author realizes a 60-year quest to see and hike in the Cirque of the Towers

Text and Photographs by Thomas Loucks

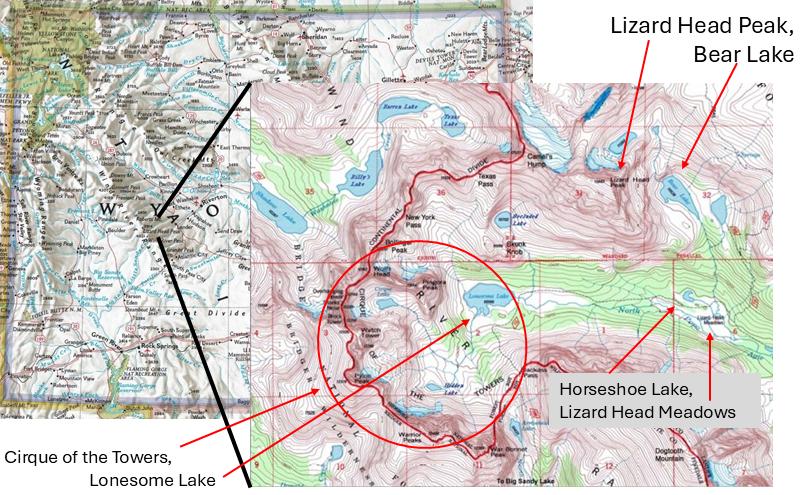

For decades, I have been an active hiker/ climber. As a younger man, I spent years climbing and mountaineering, with ascents in British Columbia, the Tetons, and the French Alps, not to mention many years of climbing East Coast rock-climbing haunts where I had grown up. But one place had fallen through the cracks – the Cirque of the Towers in Wyoming’s Wind River Range – a small but stunning array of jagged, 12,000-foot peaks surrounding a tarn in the middle of a remote and rugged, montane landscape.

As a boy, I enjoyed photography, yet only in retirement did I plunge into acquiring skills in landscape and wildlife photography. Readers

of Focal Points know from my contributions (e.g. on the Pyrenees or on Colorado’s high peaks), that my favorite avocation is landscape photography in alpine settings.

While still young, I had married and we moved west, living in such gorgeous states as Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. Early on, we discovered David Muench’s stunning “coffee table” books of photos, celebrating these states and the National Parks. My wife and I collected his books and used them to inspire our vacations.

My hiking days had started with trips offered by a summer camp. One of the camp counselors – Joe Kelsey – would go on to

become Wyoming’s Wind Rivers’ biggest advocate. He authored the Falcon Guide to the Wind Rivers as well as other books and “coffee table” books on the Winds. Also, two friends from the 1960s climbed Pingora Peak in the Cirque and regaled me with stories of how remote yet stunning such a special place could be. My appetite was whetted, yet decades would pass before satiation!

That’s the 60-year back-story. Imagine my recent surprise to learn that Muench Workshops was offering a landscape workshop specifically to the Cirque of the Towers! Marc Muench (David’s son) had picked up his multi-generational family photography baton and became one of the three founders of Muench Workshops. Muench trips today offer all-inclusive workshops in gorgeous destinations. Even more important to me is that they also offer trips to non-iconic yet stunning locations –such as Cirque of the Towers sited in the Popo

Agie Wilderness. It suddenly came together: The stars aligned, and I was going!

That was the good news. Reading further about the workshop, I discovered that to get there I would need to ride 15 miles one way on horseback and camp just below tree line for four nights. The workshop would include three full days in the Cirque, a full day to ride in and another to ride out, and a final morning at the ranch for a photo review session. Of course, the workshop would require a day’s travel each way before and after. So, that was a full week for the workshop and five days off the grid and without electricity. Considerable thought would be needed to prepare for horseback riding, camping, hiking, and photography while minimizing gear and keeping camera batteries charged.

Allen’s Diamond 4 Ranch would be our outfitter. It is the highest altitude wilderness guest ranch in Wyoming and offers alpine

trail riding, fly fishing, wilderness pack trips, and hunting and photography trips in the Shoshone National Forest. The surrounding Wind River Range boasts the largest active glaciers in the lower 48 states and hundreds of alpine lakes, and the unique setting of the Ranch provides easy access. Four brothers founded the Ranch in 1973, and today the family business is run by Jessie Allen, daughter of one of the four founders.

As the trip drew near, I focused on preparing my gear.

Clothing first: I needed clothes for the drive from Denver; clothes for horseback riding;

clothes for camping at 10,000 feet and hiking and shooting at over 10,600 feet. I would be able to leave much of this in the car at the ranch, but all the rest would be worn or stuffed into small bags to be carried by packhorse in paniers.

Next was technology: We would take computers for a post-workshop review, but we’d leave those in the cars while camping. I took two full-sensor cameras and my kit lens (28-300mm) in lieu of a telephoto. My main lenses would be 16-35mm and 24-70mm. I had my iPhone for more informal images, and I needed my tripod plus polarizing and a range of neutral density filters.

I would be away from electricity for five days, so I had two power banks for batteries – and I had spare batteries which were already charged. I estimated how many images I might take and planned accordingly for sufficient memory cards to suit.

July 2023: I drove to Lander from Denver and spent the night. The next day, I stopped at the Wind River Indian Reservation office to obtain a permit for access, then drove across the Reservation and into Shoshone National Forest on a dirt and gravel road to the Ranch. In July of 2023, there was still no Wi-Fi at the Ranch, so farewell emails and phone calls had been made from Lander.

The Muench workshop provided two guides (Joseph Roybal and David Rosenthal), and

there would only be five clients. When I arrived at the Ranch mid-afternoon, David greeted me with disheartening news: we might have to cancel the workshop! Spring snowmelt was heavy, and the streams might be too swollen for us to make the three crossings required to gain access to the Cirque. Joseph had departed earlier in the day on horseback with Ian, the head wrangler, to scout a different cirque as an alternative. Facing this dilemma without phones or WiFi, I was impressed to see that David was in contact with Muench headquarters, discussing alternatives by linking his cell phone to his inReach® two-way satellite communicator.

When dinner time was upon us, we were still undecided on the morrow. Joseph and Ian

Sunset on the North Popo Agie as seen from

had returned, and they informed us that an alternative cirque was a possibility. During dinner, the owner, Jessie Allen, announced her plan for the morning: We were to wake up and assume that our trip was a Go. She would accompany us, and SHE would decide about the crossings and what the horses could bear. There were several concerns. Rocky stream bottoms in fast moving water meant tricky footing for the horses. It was important to allow the horses all leeway to make their own decisions about where to wade. Also, our camera gear would be hanging in paniers on the sides of the packhorses – so, while the gear would be packed in waterproof bags, we did not want to tempt fate by soaking the bags if the crossings were too deep. Finally, if we made two crossings but not the third, we would

need to retrace much of our route – plus those crossings – before even starting the alternative route. Jessie would make the call. We retired to our cabins to give batteries one more charge and to prepare for horseback in the morning, although our destination remained unknown.

The morning brought blue skies. We chowed down breakfast and met at the corral for riding lessons, tack-fitting, and loading the packhorses. The Diamond 4 wranglers fitted each of us to our saddle and adjusted our stirrup length so that our weight would correctly balance between rump on the saddle and feet in the stirrups. My knees would be slightly flexed for the entire journey, built-in shock absorbers.

The wranglers packed the horses into trailers for the two-mile drive to Dickinson Park from where we’d ride 15 miles to our campsite on the North Popo Agie River, a mile below the Cirque of the Towers. Several times along the way, we dismounted and walked beside our horses, giving them – and ourselves – a break, but never stopping. There was no lunch stop. We munched on snacks from our saddle bags and drank water from our water bottles, but the horses always kept moving, and WE either rode or walked beside them. As to the weather, our blue-sky dawn betrayed us. Never mind the usual afternoon rain squalls – two hailstorms hit us soon after we had set out – so we did pause to don rain gear.

Jessie rode ahead of us and led two packhorses as she anticipated the river crossings. The first was shallow, so the water was fast, but “shallow” the horses could handle. The second crossing was deeper and slower, but the horses could still manage, and the paniers remained high and dry. The third crossing would be the crux that determined whether we could attain the Cirque – it was the deepest. Jessie halted the packtrain at the water’s edge and studied the river’s depth. Judging that it appeared doable, she dispatched one of the wranglers to cross to observe how he fared and how high the water rose against the horse’s legs and body. The rest of us watched anxiously and were tuned into where the water came against the horse’s

belly. We knew that the paniers with our camera gear did not hang as low as the belly, so if the belly was clear, our gear should be safe.

The lone wrangler picked his way across the stream, and his horse’s belly only tickled the water. Jessie declared our trip a Go, and we were off to the Cirque! She stayed long enough at the crossing to see everyone safely across, and then we were on our way.

Late in the afternoon, when we reached our campsite, the skies broke open again. Now the heavens really poured. The wranglers hung a large tarp between the trees so we the clients could shelter from the downpour, and then set about helping the cook set up camp.

The storm didn’t last long, and soon we were each given a two-man tent to set up on our own. Having a two-man tent meant that we could keep our gear inside and under cover in case of weather.

While daylight remained, each of us prepared for an early morning shoot: hiking gear, camera packs, water bottles, tripods, possibly backup batteries and memory cards, and certainly headlamps.

While we were tending to such preparations, the wranglers gathered the horses, remounted, and headed back to the ranch with an additional 7-8 hour ride before them. Yes, horses can see in the dark!.

We were camping just below tree line, adjacent to Horseshoe Lake and alpine meadows on the North Popo Agie River, sourced by waters from Lonesome Lake, the tarn located just a mile above us in the Cirque. With a quick dinner behind us, we still had time that first evening to scout the meadows for a sunset shot.

Our daily rhythm now shifted to more of a routine. There was an early morning rise, hiking, shooting, returning to camp for breakfast, sorting gear, recharging batteries, napping, a light lunch, scouting nearby shoots, early dinner, evening hiking and shoots, and back to bed. As we settled into

this routine, our two guides were also ensuring that we acclimatized by prioritizing our shoots by difficulty. Two of us were from Colorado and accustomed to hiking at altitude, but three of us were coming from sea level. The workshop had been advertised as strenuous, and it certainly was.

Each morning – one of which started at 3:45 – we were greeted by our cook who had already built a fire, made coffee, and coffee cake. She was there for us all day with snacks, hydration drinks, lunch, dinner, and dessert. Making all that happen was transparent to us. There was always firewood and abundant drinking water for refilling our water bottles.

The Cirque’s War Bonnet and Warrior Peaks I and II bask in early morning light behind Lonesome Lake, a dramatic reminder of why we had sought out such a destination.

Our surroundings offered plenty to keep us occupied when not out on extended hikes into the Cirque or alternatively into a hanging valley at Bear Lake. Our images showed gorgeous landscapes in flattering light, and we delighted in witnessing what we had come for.

The final evening in camp brought an unanticipated treat. The wranglers brought the horses up the night before our pack trip out, and, after an early dinner, some of us descended with Joseph to spend time with the horses and wranglers in the waning light. These were remarkable moments, as the horses were wandering the meadows and feeding on newly grown grasses, and the wranglers prepared them for the night out. It was special to observe the wranglers tending to their horses.

In the morning, the wranglers delayed the ride out to allow us time for one last shoot at Horseshoe Lake, and we lingered to savor our final moments and views of the Cirque. That done, we gathered our belongings and helped the wranglers load the horses.

The pack trip out was uneventful. We remarked how much the stream crossings had fallen even in four days. There was little conversation. Each of us was lost in personal reverie as we distilled how unique the past few days had been.

Then it was over. We entered Dickinson Park, the trucks were waiting for us, and the trip was ending. For me, the successful workshop answered decades of wondering just how sublime the Cirque of the Towers might be.

photographs by John Fisanotti

In the preceding installments, I’ve tried to give a good sense of what to expect on a trip down the river and through the Grand Canyon. I’ll conclude the series of articles by telling the story about some of the photos I took on the trip.

“Knowing where to stand” is a concept in photography, much like, “the decisive moment” and for me, the phrase, “He knows where to stand” often comes to mind when I’m looking for a location to shoot from. A good example came on the third day of the trip.

Near mile 32, we pulled in to a beach for lunch and exploration at South Canyon, a tributary to the Colorado River. South Canyon provides access to the river from the North Rim and has been used by indigenous peoples. We set out on a short hike up the steep hillside above the river to find rock art, and some archaeological ruins. It was evident that this part of the canyon was occupied by native peoples perhaps 1,000 years ago. As we approached the remains of the rock walls forming the structure, our backs were generally to the river, and the view beyond the structure was that of the steep hillside.

Everyone in our group, as they came upon the structure, photographed it just as they came upon it with their backs to the river. But I looked at it and realized, if I just walk around to the other side, I can get a photo of the archaeological ruins, with the river in the background – a view providing far more context than a photo with simply a bunch of dirt in the background. After taking my shot, I pointed out the advantages of this point of view to the others and many followed suit, by taking their

own shot of the ruins from this opposing point of view. This comes from studying the subject and looking around before picking up the camera. One of the photos presented in the first installment of this series, (in the March/April 2024 issue of Focal Points) has this point of view I’ve described showing the rock art, which was near the ruins, with the river beyond.

We visited a number of waterfalls in tributary canyons during the trip. Often, they were deeply recessed in shady and narrow slot canyons. The resulting open shade facilitated taking long exposure shots of the flowing water, and kept the contrast manageable. But on the tenth day, at Deer Creek Falls, (Mile 137) it looked like my luck had run out.

Deer Creek Falls is a well-known landmark with a waterfall that is easily visible from the river. We got there around mid-day and the falls and everything around it was in full, harsh sunlight. I took an obligatory photo of the falls, and then joined the group on a hike. The trail led up around the falls, and into a narrower canyon, whose floor was bisected by an even narrower slot canyon. Peering over the edge into the darkness of the slot, I could see Deer Creek making its way towards the riverside waterfall.

To get into this narrower slot, Deer Creek tumbled over another waterfall, at the upstream end of the slot, above which the creek was at even elevation with the trail we were on. We stopped just above the upper falls, where the canyon widened and the creek was at our feet. It was hot and we all lounged about in the shady side of the canyon.

Opposite page: Mile 121. Blacktail Canyon

Trying to find a compelling image in this landscape was a challenge. The lighting was harsh, and the most photogenic subject – the upper falls – appeared inaccessible in the slot. From where I stood, I could only look down the face of the falls from above. Also, it was tough to find an angle without a bunch of resting hikers lounging on the rocks looking like they had all just passed out.

Then, I saw that on the opposite bank, a cactus with yellow blossoms was perched at the edge of the slot and, if I could get to the opposite side, I could get a shot looking back at the front of the waterfall, with the foreground cactus framing the waterfall and the expanse of the canyon in the background. But getting to this spot looked a little tricky. After thinking about this image, I approached Marieke, the lead guide and group leader of our trip, with a request. To take the

photo, there were three issues, I needed to solve for: 1) permission to get into position; 2) delaying the shot as long as possible to improve the lighting; and 3) avoiding having a bunch of lazy looking hikers populating the shot.

Crossing the creek above the falls was easy, but the trail to get in position above the slot part of the canyon looked a little sketchy with some exposure. A fall there would likely send me to the bottom of the slot, about 20-25 feet below. Knowing that our guides are responsible for our safety, I knew I would have to ask permission, before venturing off on the risky path. After I explained the photo I wanted to take to Marieke, I then asked that when it came time to leave for the boats, that I be allowed to stay behind to take the shot. In this way, it eliminated the people and, I hoped, the later time would bring more shade to the canyon.

Opposite Page: Mile 137. Upper Deer Creek. Above: Mile 152. A young bighorn sheep near Ledges camp

She agreed with my request with the stipulation that I be back at the boats no later than a half hour after the group leaves the canyon, and she assigned Vladimir, one of the guides, to remain behind with me. I was thrilled that she agreed with my request.

The photo of Upper Deer Creek Falls is the result of this visualization and figuring out where to stand.

If knowing where to stand is important, then staying on your feet is even more so. I brought two cameras on the trip. My main camera was a mirrorless Nikon Z6II. The other camera was a waterproof point and shoot, a Nikon W300. Since the Z6II isn’t waterproof, it was protected in a Pelican case strapped to one of the boats

when we were on the move. Generally, I had access to this camera only when in camp in the mornings and evenings. However, when we stopped for a hike, I often requested the Pelican case and took the Z6II with me to shoot before returning it to its secure location when we resumed the raft trip.

On the twelfth day, we put in at Matkatamiba Canyon (Mile 148) and began gathering our stuff to take on a hike up this intriguing side canyon. It was here that I had a rather amusing incident. The lower part of the canyon narrows to the point where there is room enough only for the creek, so our route upwards required walking upstream in sometimes waist high water.

At this point, my camera was in my backpack to free up my hands. We reached an obstacle. It was a roundish boulder placed like a chockstone in the middle of the canyon. We would have to crawl over it. When it was my turn, I hauled myself out of the deeper pool that formed below the rock and gained purchase on the smooth rock. I was almost over it when my wet shoes slipped off the smooth boulder and I lost my balance, falling backwards into the deep pool below.

With a splash I was completely submerged backpack and all. When I surfaced, all I could hear was a chorus of voices exclaiming, “THE CAMERA!” It was then that I realized that to my companions, my personal welfare was of only secondary importance!

But the photo gods shined down on me that day. For whatever reason, earlier when I was in the boat and gathering my stuff for the hike, I decided to leave the Z6II behind and instead packed the waterproof camera with me for this hike. During the trip, this was the only time I took the waterproof camera with me on a hike, instead of the Z6II. It’s funny how things can sometimes work out without our realizing it.

On the next to the last night, our leader, Marieke, announced we would be having a

farewell dinner to celebrate a successful trip and to let our hair down. Our guides broke out costumes, which were packed in the rafts for just this occasion. There were laughs and good times shared by the group, bonded by traveling more than 200 river miles through unmatched scenery.

By this night, my reputation as a photographer, resulted in my being asked to take the group photo for the trip. The Farewell Dinner Party Photo shows the group, costumes and all seated around the dinner table. Here again, I had to figure where to stand. It seemed no matter where I stood around the table, I couldn’t get a clear view of everyone – someone’s head was always being blocked by someone else’s. With so many people seated around the table, I needed an elevated point of view to clearly see each person. Fortunately, I found a small sandy hummock nearby that gave me the elevation I needed.

This concludes the series of articles I have presented to share my photos and stories of a trip down the Colorado River from Lee’s Ferry to Diamond Beach. It is a trip I would recommend everyone should do if they can.

Mile 199. Confluence of Parashant Wash (canyon to the left) in the morning.

Article

photographs by Peter Bennett

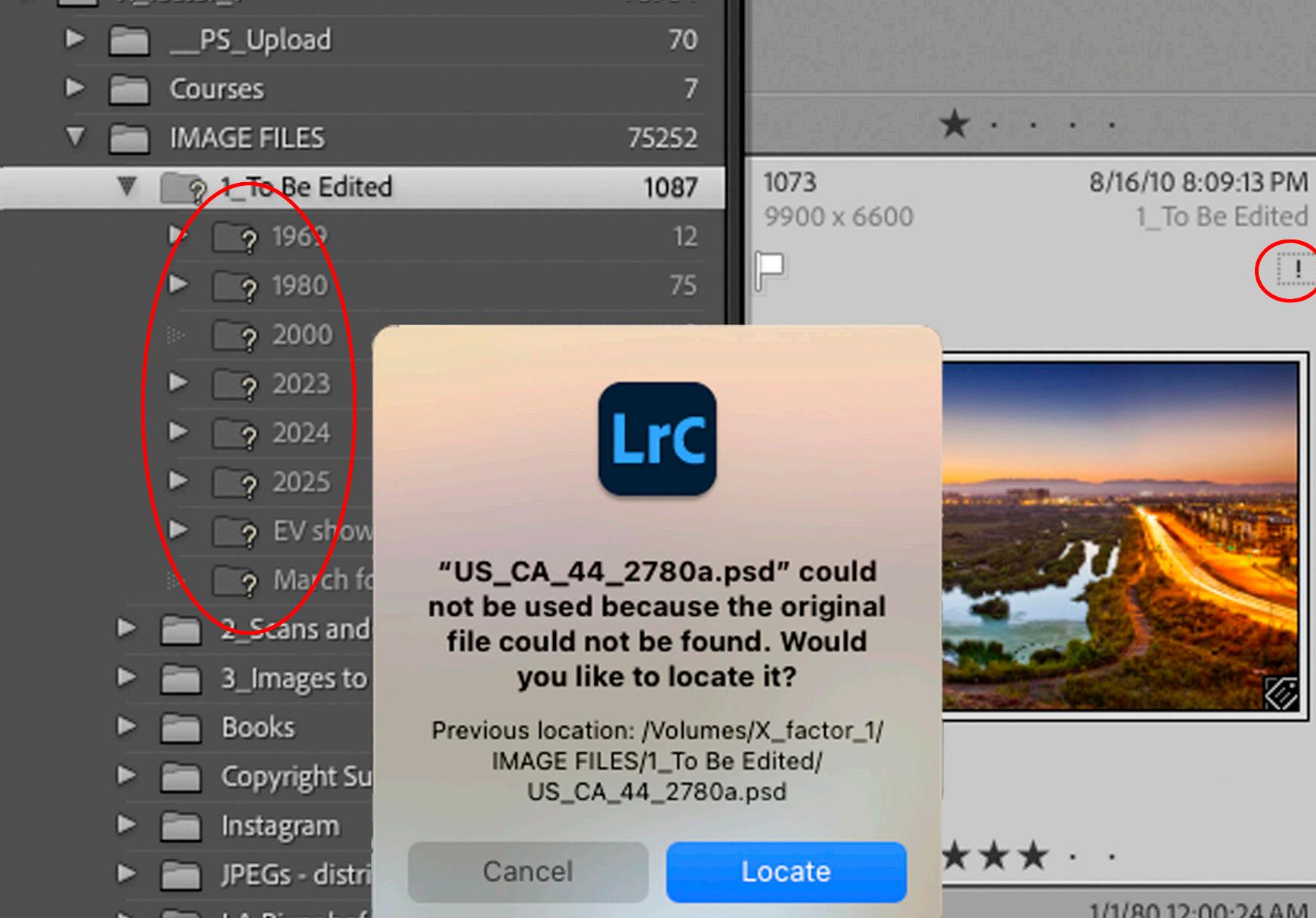

So, I'm the guy people call when their Lightroom Classic catalog is a mess. Unfortunately—or fortunately—people keep making the same mistakes, which leads to a lot of the situations that cause them to reach out to me. I actually have a long list of things I see people do wrong in Lightroom, but I thought I’d tell you about five of the biggest and most common ones, and the kinds of problems they can cause.

The best definition of an unhealthy Lightroom catalog is this: you can’t find the images you’re looking for. And isn’t that the whole point of having a catalog—to be able to find things? Common problems include unlinked images marked as “Missing,” too many duplicates, and a folder system that feels out of control and disorganized.

There can be various reasons behind these issues. Sometimes, with a bit of detective work, you can figure out what caused them.

But often there’s no single explanation—it’s a combination of things that led to the mess. Instead, it’s better to learn how to do things correctly from the start—and most importantly, to do them consistently. Inconsistency always leads to chaos.

I’ve found that even when I show clients the right way to do things, they often forget— especially if they don’t apply what they’ve learned regularly (there’s that inconsistency again). But when I point out the mistakes they’ve been making, it often sticks better. They start to recognize the things they did wrong and avoid repeating them.

Hence the title of this article—so you can spot some of the things you might be doing that are causing problems in your Lightroom catalog. So here we go:

1. You change things in Finder or File Explorer after importing into Lightroom

This is by far the biggest mistake people make. It causes more problems than anything else because it breaks the link between the Lightroom catalog and the actual files on your hard drive. You’ll see exclamation points on image thumbnails and won’t be able to edit them in the Develop module. If a folder is unlinked, you’ll see a question mark next to it.

So, a basic understanding of how Lightroom works is crucial. When you import images into Lightroom, two things happen: a preview is created (what you see in Lightroom), and a link is made to the original image on your hard drive.

If you change the name of a folder or move files using Finder (Mac) or File Explorer (Windows), you are going to break that link and Lightroom can’t automatically update

it—it has no idea what you did. The result? Missing files and folders.

Rule #1: Never make changes outside of Lightroom to the folders or files you’ve imported. Use Lightroom to move or rename folders and files. Everything you can do in Finder or File Explorer, you can do inside Lightroom.

Remember: What happens in Lightroom, stays in Lightroom.

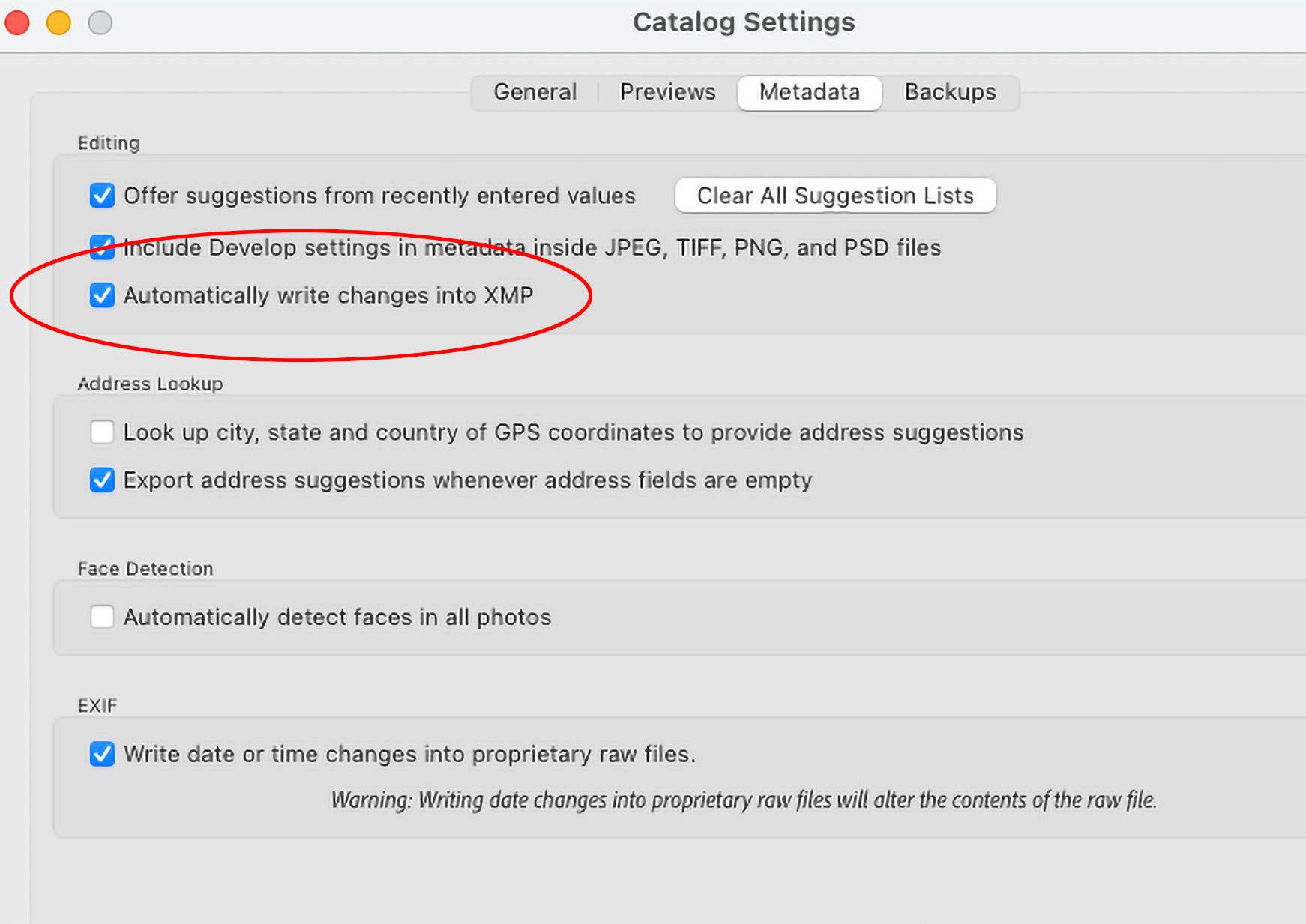

2. You don’t save Metadata to File

When you make edits in the Develop module or add metadata, like captions or keywords, to RAW or DNG files, those edits exist only in the Lightroom catalog. They aren’t actually saved to the image file unless you export the image, or use the Save Metadata to File command (under the Metadata drop down menu). This embeds the edits directly into the file or creates a sidecar file with the extension .XMP.

After editing, I always save metadata to file— either using the drop down menu, or using the keyboard shortcut Command+S on Mac or Ctrl+S on Windows.

If you find it hard to remember, you can set Lightroom to do this automatically in Catalog Settings → Metadata tab → check Automatically write changes into XMP. I don’t use this setting personally, because autosaving can slow things down if you're editing a large batch of images. But whether you do it manually or automatically—just make sure it's done.

Why is this important? If you have a lot of missing files and folders, or your catalog becomes corrupted or you lose access to it, your only option may be to re-import those images back into an existing, or a new

Lightroom catalog. But if your Develop edits and metadata were never saved to the image files—you will lose those edits.

Saving metadata ensures your Develop edits and IPTC metadata are stored with the images themselves, not just in the catalog.

It is important to understand that this only applies to RAW and DNG files. You cannot save and embed Develop edits into JPEGs, TIFFs, PSDs, or any other rasterized file. However, you can save IPTC metadata (like keywords and captions) to those files.

Note: In case you don’t know, Preferences are global settings for all your Lightroom Catalogs, and Catalog Settings, which you’ll find under the same drop-down menu (Lightroom on Mac, Edit in Windows) are settings specifically for that catalog. So, you

will have to make the Catalog Setting for each Lightroom Catalog you use.

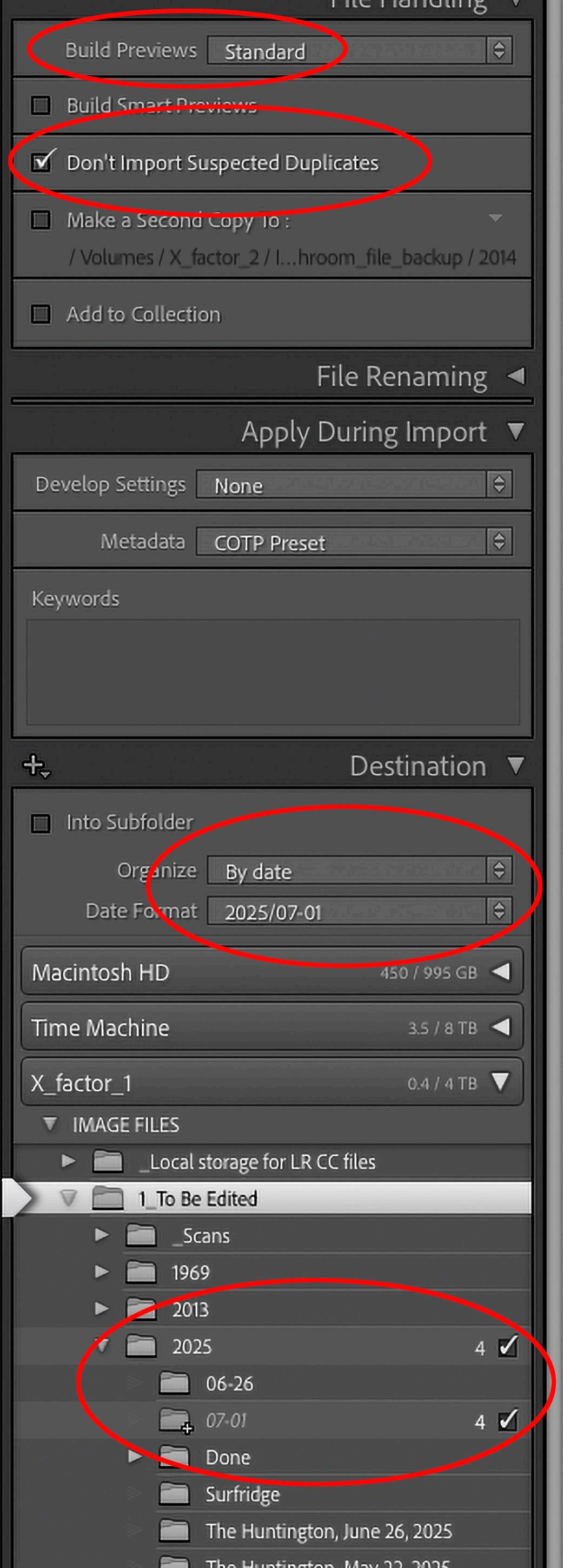

3. You don’t use import presets when importing from SD or CF cards

The import process is one of the most confusing aspects of Lightroom for many people. They often don’t know where their images are going.

You have three import options: Add, Move, and Copy.

• Use Add or Move when the images are already on your hard drive. Lightroom just links to them.

• Use Copy when importing from temporary media like an SD or CF card. You need to copy the images to your hard drive—

otherwise, Lightroom will be linked to a card that’s going to be removed.

When using Copy, there are several settings to manage:

• File Handling: I choose Standard Previews and check Don’t Import Suspected Duplicates.

• File Renaming: I don’t rename on import; I do that later.

• Apply During Import: I use a Metadata preset that includes my contact info.

• Destination: I organize by date using the format 2025/07-01.

I like to use a landing folder so all my new imports go into a folder called To Be Edited, and Lightroom automatically creates subfolders based on the import year and date. I edit everything there, then move finished files into my main archive.

Import Presets let you save all these settings. Once saved, all you have to do is select the source (your memory card), choose your import preset, and hit Import. This ensures consistency and saves time.

To create a preset: set up all your import options, then go to the Import Preset menu at the bottom center of the import dialog, click the arrows, and choose Save Current Settings as New Preset. Name it something like Import from Card Preset.

Rule #2: Always remember to choose the import preset, it does not automatically load the preset every time you do an import.

4. You back up the catalog on quitting (when you don’t need to)

This isn’t exactly a “mistake,” but it can be unnecessary and wastes storage space if you already back up your entire computer and/or external hard drives (and you should, ideally both locally and offsite). In light of the recent fires we had here in LA, not having offsite back up is potentially a disaster waiting to happen.

Each time Lightroom backs up the catalog on quitting, it can add gigabytes of storage to your hard drive. I've also seen people accidentally start using one of their backup catalogs instead of the main one—which often creates a ton of confusion.

To avoid this, go to Catalog Settings → Backups tab → and set Back up catalog to Never.

Only make this change if you are currently backing up your computer and hard drives

You’ll find your old backups in your Lightroom folder. Feel free to delete them, again, if you're confident in your regular backup system.

5. You don’t turn on View Options

Nine times out of ten, when I open a new client’s catalog and look at the Grid view, I see the image thumbnails displaying only the index number—which is pretty useless. That just shows the order in which the thumbnails are being displayed.

I want to see meaningful information at a glance. Lightroom gives you that ability—you just need to turn it on.

In Library mode, go to the View menu → View Options. You'll see two tabs: Grid View and Loupe View.

• Under Grid View, choose Expanded Cells from the Show Grid Extras dropdown.

• Then customize the four labels you want displayed. I usually choose File Name, Cropped Dimensions, Capture Date/ Time, and Folder.

• Under Loupe View, check Show Info Overlay and select the labels you'd like to display.

Once this is done, check your thumbnails and I guarantee you that you've just made your Lightroom life a lot easier. For example, I can see the File Name clearly displayed instead of that useless index number. I also see the Cropped Dimensions, which is helpful if I have multiple versions of the same image at different sizes. Seeing the Capture Date and Folder name helps me quickly understand what I’m looking at.

Again, format for whatever you think is going to be the most helpful to you.

In Summary:

So, to sum it up, these are just five things you can do to make working in Lightroom more efficient and organized for you. Saving time and doing things correctly frees you up to do the fun things, because let's face it, a lot of the organizing and workflow stuff is not terribly exciting, but it is necessary. Good luck and have fun.

Article

photographs by Rebecca Wilks

Many of us have our special places in nature. I certainly do. Secret dunes in the Mojave, Along the Upper Provo River in Northern Utah, Fish Lake in Utah. None of these can compare to the connection I feel to Grand Canyon’s North Rim and the adjacent North Kaibab National Forest. I’ve spent more than 150 nights there.

Driving south on Highway 67 from Jacob Lake always feels like a homecoming, especially when the aspen groves start to show off in the autumn.

I have a long connection with this place, going back 35 years to my first rim-to-rim hike. I was introduced to the spectacular opportunities for photography there during

I was 28 years old when I embarked on my first rim-to-rim backpack from the North Kaibab Trailhead.

a 2009 photo workshop with Pete Ensenberger, former photo editor for Arizona Highways Magazine. He exposed me to the viewpoints on the Canyon from the Kaibab Forest, which became my obsession for years.

A few years later, during my quest to visit as many viewpoints as possible I met Ranger Jess, who generously gave me location tips and encouragement and became a friend. When I visited, we would often have a meal or a celebratory beverage at the lodge or at

her house. She’d generously let me driveway-camp on those nights, so I could avoid the need to look for a spot in the forest after dark. The campground inside the park, you see, was always full.

At this writing, the Dragon Bravo Fire, started by lightning July 4, is still reported as 0% contained. It was managed with the “let burn” philosophy and got out of hand, much like the Yarnell Hill Fire which devastated my hometown in 2013. Reports are coming in about the destruction of as

many as 80 buildings, including the main lodge, rebuilt on the edge of the canyon in the 1930s after another fire in 1932. Timely evacuations of almost 900 guests and staff ensured that no lives were lost, including those of the Grand Canyon Mules.

The lodge was designed byGilbert Stanley Underwood, who designed a number of other hotels in national parks. Constructed in the organic style of nativeKaibab Limestoneand timber, the lodge complemented the surrounding forest and geology. The buildings were the last complete surviving lodge and cabin complex in thenational parks of the United States.

The main lodge building had two verandas, where I often watched weather moving

through the canyon, photographed sunrise and sunset, and joined the annual star party, learning from a delightful assortment of astro-geeks. The central room in the lodge was known as the Sunroom.

Downstairs from the Sunroom was an openair space unofficially known as the Moon Room. This was my favorite place to read and contemplate, especially on a hot day. It was 15° F cooler down there, and most tourists either took a quick look and did a U-turn or didn’t bother with it at all. I spent hours there, enjoying the quiet.

Craig Childs, my favorite Southwest writer, wrote “The Grand Canyon Lodge is our Notre Dame, our vaulted holy architecture. It will return. It must.” I agree, though

private funding may be required in today’s political climate.

The lodge is a huge loss, and there’s more.

Robert Stieve, the Editor of Arizona Highways Magazine, lists the Widforss Trail (named after landscape painter Gunnar Widforss, 1879-1934) as one of his favorites. I agree. I used to get the one (per night) backcountry permit for that sector and backpack to the point, or to the head of Transept Canyon, for some spectacular scenery and unparalleled solitude. I believe that most of the 5-mile trail has burned. Though the stunning forest there will

recover, I fear I won’t live long enough to see it.

The Transept Trail connected employee housing with the lodge and allowed lovely views of the eponymous canyon. I fear these vistas are marred as well.

I had photographic plans for this summer, some of which I’ll now never be able to pursue, and others will have to wait at least

until next spring. The North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park will be closed until then, at least. I suspect that when it does open, it will be available for day use only for quite a while.

Yes, destructive fires are part of life, especially in the wilderness of the Southwest US, but that doesn’t mean I have to like them. Grief takes many forms.

Photos from my trip in May to the Northern Cape area of South Africa in the Kalahari Desert.

A cheetah on a hunt at sunrise uses the height of a sand dune to scan for prey.

Opposite page: A meerkat watches over a couple of youngsters at the edge of their burrow.

All in a days work! A dung beetle struggles to push a large ball of dung up a steep part of sand. Flies are attracted by the smell and swarm around, and even hitchhike on the beetle’s back as he determinedly moves the ball.

Kalahari daisies are one of the wildflowers that briefly fill the landscape in winter, especially after a late rainy season. Some zebras wandered through them as they search for fresh shoots of grass.

Darkness over Kalahari with the Milky Way across the sky. Another vehicle driving in the distance briefly backlit the dead tree in the landscape.

Afternoon stroll on the dunes

Desiccated Milk Thistle, Paramount Ranch, Santa Monica Mountains

Opposite Page: Shaw Agave, Theodore Payne Foundation Garden, Sun Valley

The saguaro cactus bloom in the Sonoran Desert this May was spectacular. It was a nice consolation, since the annuals did not show up in March.

Opposite page: Ponderosa trunks on a background of spring aspens, Kaibab National Forest, Arizona.

June at 9000’ on the Kaibab Plateau (Arizona) is early spring. Some aspen clones were just starting to leaf out.

The Fishlake Forest in Utah has gotten more rain than we did at home in Arizona. The lupines were looking healthy.

Opposite page: Channeling Velda, I appreciate a faded beauty now and then. Fishlake National Forest, Utah.

Top-down drone image of our delightful, dispersed campsite, deep in the tall aspens. Fishlake National Forest, Utah.

Opposite page: Asters beside the Upper Provo River in the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, Utah.

Mammatus Skies (above) Brooding Light (below)

Opposite page: The Giant

A float plane landing on the Taku River (above). A caribou in Denali NP

These two pages are from our May-June trip to Alaska.

A moose with her weeks-old calf. According to our guide, the calf was probably a twin. The mother is only able to defend one calf when predators attack.

The Caltech Owens Valley Radio Observatory, near Big Pine, is a remarkably interesting and accessible place.

Opposite page: Bristlecone pines are incredibly resilient. This specimen had considerable fire damage at its base and up the trunk, but was still quite healthy.

In July I started working on images for my 2026 calendar. This is a selection of my favorites.

Born and raised in New York City, Peter picked up his first camera and took his first darkroom class at the age of twelve.

Peter spent many years working as a travel photographer, and in 2000 started his own photo agency, Ambient Images. In 2015 he formed Citizen of the Planet, LLC, devoted exclusively to the distribution of his stories and photographs that focus on a variety of environmental subjects.

Peter’s editorial work has appeared in many publications including the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, Sunset Magazine, Los Angeles Magazine, and New York Magazine. His prints hang in the California State Capitol, California Science Center’s permanent Ecosystem exhibit, and many other museums, private institutions, and collector’s homes.

He has also worked with a numerous local environmental organizations over the years including FoLAR (Friends of the LA River), The Sierra Club, Greenpeace, Heal the Bay, 5 Gyres Institute, Algalita Marine Research Foundation, Communities for a Better Environment, and the LA Conservation Corps.

Peter has been an instructor for over fifteen years at the Los Angeles Center of Photography, and for years led their Los Angeles River Photo Adventure tour.

Michael Caley was drawn to photography as a teenager, during backpacking trips to Yosemite, where he was inspired by the work of Ansel Adams. Today Michael’s dramatic landscape and wildlife photography are a natural extension of his long career as an architect and his many trips to the Eastern Sierras, Joshua Tree NP, the western United States and five trips to Africa. His work has been exhibited in several different venues including a 2010 solo exhibit at The G2 Gallery in Venice, CA. He can be reached at mcaleyaia@aol.com

John Clement began his career in photography in the early 70’s after graduating from Central Washington University with a double major in Geology and Geography. Since then he has earned a Masters of Photography from the Professional Photographers of America. He has received over 65 regional, national and international awards for his pictorial and commercial work. His photographs grace the walls of many businesses in the Northwest and has been published in numerous calendars and coffee table books.

Clement has provided photographs for Country Music Magazine and Northwest Travel Magazine. He has supplied murals for the Seattle Seahawks Stadium and images for The Carousel of Dreams in Kennewick, WA.

Current projects include 17 – 4x8 foot glass panels featuring his landscapes in Eastern Washington for the Pasco Airport Remodel. Last year he finished a major project for the Othello Medical Clinic where almost 200 images were used to decorate the facilities.

www.johnclementgallery.com

John Clement Photography (Face Book)Allied Arts Gallery in Richland, WA.

Joe grew up in Los Angeles and developed his first roll of film in 1972. He has been a visual communicator ever since.

He spent his teens and twenties working in photography, most of it behind a camera as a freelance editorial shooter.

Joe switched careers when his son was born, earning a PhD in Political Science from UCLA. This led to an opportunity to run a research center at UCLA Law.

After retiring from UCLA in 2016, Joe did some consulting, but now he and his wife, Velda Ruddock, spend much of their time in the field across the West, capturing the landscape. www. joedohertyphotography.com

John was a photography major in his first three years of college. He has used 35mm, 2-1/4 medium format and 4x5 view cameras. He worked briefly in a commercial photo laboratory.

In 1980, John pivoted from photography and began his 32-year career in public service. He worked for Redevelopment Agencies at four different Southern California cities.

After retiring from public service in 2012, John continued his photographic interests. He concentrates on outdoors, landscape, travel and astronomical images. Since 2018, he expanded his repertoire to include architectural and real estate photography.

John lives in La Crescenta and can be contacted at either: jfisanotti@sbcglobal.net or fisanottifotos@gmail.com http://www.johnfisanottiphotography.com http://www.architecturalphotosbyfisanotti.com

Beverly Houwing loves traveling and photography, which has taken her to 80 countries and every continent. Most often she visits Africa since she loves spending time in remote wilderness locations where there is lots of wildlife and unique landscapes. Her images have been featured in numerous Africa Geographic articles, as well as in Smithsonian and the Annenberg Space for Photography exhibits. Her photographs have also been used for promoting conservation by many non-profit organizations, including National Wildlife Federation, National Parks Conservation Association, Crane Trust, National Audubon Society and Department of the Interior. Beverly is an Adobe Certified Instructor, so when she’s not out on a photography adventure she conducts training on their software programs and does freelance graphic design and production work.

Tom Loucks has been a longstanding amateur photographer, dating back to the late 1960s. Only in recent years has he been able to devote serious time to the hobby. He garnered first place in National Audubon’s 2004 Nature’s Odyssey contest and has placed well in several contests by Nature’s Best, Share the View, and the Merrimack Valley’s George W. Glennie Nature Contest. He has two images of “Alumni Adventurers” on permanent display at Dartmouth College and has published images in Vermont Life and Utah Life magazines. Tom is a recent Past President of Denver’s Mile High Wildlife Photo Club.

His photographic interests are landscape, wildlife, and travel photography, though his favorite subjects are alpine landscapes. Recently retired, Tom is looking forward to spending more time on photography and other outdoor activities.

Larry used his first SLR camera in 1985 to document hikes in the local mountains. In fact, his first Sierra Club Camera Committee outing was a wildflower photo shoot in the Santa Monica Mountains led by Steve Cohen in 1991. Since then the SCCC has introduced him to many other scenic destinations, including the Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve, the Gorman Hills, and Saddleback Butte State Park.

Larry’s own photography trips gradually expanded in scope over the years to include most of the western National Parks and National Monuments, with the Colorado Plateau becoming a personal favorite.

Photography took a backseat to Miller’s career during the 32+ years that he worked as a radar systems engineer at Hughes Aircraft/Raytheon Company. Since retiring in 2013, he has been able to devote more time to developing his photographic skills. Experiencing and sharing the beauty of nature continues to be Larry’s primary motivation. lemiller49@gmail.com

Velda Ruddock

Creativity has always been important to Velda. She received her first Brownie camera for her twelfth birthday and can’t remember a time she’s been without a camera close at hand.

Velda studied social sciences and art, and later earned a Masters degree in Information and Library Science degree from San Jose State University. All of her jobs allowed her to be creative, entrepreneurial, and innovative. For the last 22 years of her research career she was Director of Intelligence for a global advertising and marketing agency. TBWA\Chiat\Day helped clients such as Apple, Nissan, Pepsi, Gatorade, Energizer, and many more, and she was considered a leader in her field.

During their time off, she and her husband, Joe Doherty, would travel, photographing family, events and locations. However, in 2011 they traveled to the Eastern Sierra for the fall colors, and although they didn’t realize it at the time, when the sun came up over Lake Sabrina, it was the start of them changing their careers.

By 2016 Velda and Joe had both left their “day jobs,” and started traveling and shooting nature – big and small – extensively. Their four-wheeldrive popup camper allows them to go to areas a regular car can’t go and they were – and are –always looking for their next adventure. www.veldaruddock.com VeldaRuddockPhotography@gmail.com

Rebecca Wilks

Photography has always been some kind of magic for Rebecca, from the alchemy of the darkroom in her teens… to the revelation of her first digital camera (a Sony Mavica, whose maximum file size was about 70KB)… to the new possibilities that come from her “tall tripod” (drone.)

Many years later, the camera still leads Rebecca to unique viewpoints and a meditative way to interact with nature, people, color, and emotion. The magic remains.

The natural world is Rebecca’s favorite subject, but she loves to experiment and to do cultural and portrait photography when she travels. Rebecca volunteers with Through Each Other’s Eyes, a nonprofit which creates cultural exchanges through photography, and enjoys working with other favorite nonprofits, including her local Meals on Wheels program and Cooperative for Education, supporting literacy in Guatemala.

Rebecca’s work has been published in Arizona Highways Magazine, calendars, and books, as well as Budget Travel, Cowboys and Indians, Rotarian Magazines, and even Popular Woodworking.

She’s an MD, retired from the practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medical Acupuncture. She lives in the mountains of central Arizona with my husband and Gypsy, the Wonder Dog.