ARTIST STATEMENT

BY KONSTANTINA

PAINTING IS A WAY to understand my ancestry as an Aboriginal woman in a modern and often very confounding world. For me, to understand something is to deconstruct an idea and rebuild it into a digestible tableau. It takes a lot of imagination to scroll back through 250 years of colonisation and reconstruct a place in one’s mind that is very different to the one we live in today.

For three years now, I have been fortunate to be afforded much time in the British Museum archives. The majority of this time has been spent working on a self-driven project, ‘Gadigal: Yilabara Wala’ (‘Gadigal: Now and Then’). My intention is to recode myself with the physical skills and traditional knowledge brought about by employing the original methodologies of working with natural materials to create the archival treasures held at the Museum. These skills are not something I possessed at the beginning of the project, but are now slowly being fashioned as I re-imagine the making of items. I have spent much time photographing, measuring and then physically creating treasures such as a traditional possum skin cloak, a necklace made from reed, and a dilly bag made entirely of hand spun cordage from the bark of a native hibiscus tree.

To remake these tangible objects is the first phase of the work, but to reimagine them is where the true joy lies. “Country cannot speak for itself, so art must speak for Country” (Neale & Kelly, Songlines: The Power and Promise , 2020).

RE: Imagined is the first body of works on linen, a meditation on the natural materials used for these beautiful treasures. It is a safe place where my hands can explore a new world re-imagined and inspired by their making.

These works are therefore a blueprint for the next evolution of my work with the British Museum, where my own artistic interpretation of the past becomes the future.

This work is deeply personal to me. It allows me to feel a sense of joy by looking into our past whilst using my own hands to re-imagine my future.

AN EXHIBITION OF WORKS BY PROUD GADIGAL WOMAN OF THE EORA NATION, KONSTANTINA

JGM GALLERY PRESENTS RE: Imagined an exhibition of works by proud Gadigal woman of the Eora Nation, Konstantina, inspired by her three-year research project with the British Museum.

Konstantina’s practice spans archival research, writing, social practice and small-scale sculpture, installation, film, and painting. Her engagement with each of these disciplines, however, began with a more singular directive in mind: the reassertion and recognition of her Gadigal heritage in opposition to its historic erasure. Konstantina reclaims and shares her story and family history, presenting connections to her Aboriginality which have been whitewashed since her great-grandmother’s generation. Her work documents a personal journey of rediscovery, exploring her identity and reintegrating Gadigal culture and language back into her own family’s customs.

During her ongoing research project with the British Museum (2023 − present) Konstantina examines First Nations Australian objects which are currently part of the Museum’s collection. These objects number over 6,000 items and many have never been displayed since they were taken from Indigenous communities in various collecting contexts often without consent and sometimes in circumstances of extreme violence during the project of colonisation in Australia. Konstantina’s research explores the materials from which these objects were made, as well as the techniques used to make them. From her home and studio on Bundjalung Country (Byron Bay), Konstantina enters the second phase of her project, remaking these objects using traditional materials, such as river reeds, possum skin, bark and shells, and Gadigal skill sets, including bag weaving, making and adorning possum skin cloaks, and necklace design. After this phase, Konstantina re-imagines these objects through nontraditional mediums and making processes, including beading and embroidery, creating a new ‘roadmap’ for contemporary manifestations of Gadigal material culture.

RE: Imagined showcases the results of the most recent phase of Konstantina’s project: paintings inspired by the raw materials which the Gadigal used to fashion the objects housed in the British Museum, and the original environments from which these materials were sourced. Her paintings are titled with the Gadigal

word for either the material, or the item of clothing or accessory which it is used to make. Narang Barraba , for example, is the Gadigal word for a small reed or bulrush from which the Gadigal make necklaces, waistlets and chaplets. Konstantina interprets the young plant as if through its distorted reflection in the water it is commonly found growing beside, or as a dark silhouette set against glaring sunlight. In the upper right of the painting, radials of white dots emanate from a central point, which suggest a ripple or the sun’s halo. These radials are broken by less dense lines of gold dots creating darker recesses, which resemble the elongated forms of reeds. Through this treatment, Konstantina depicts the material in its early stages of growth, within its natural environment, before the mature plant is harvested and dried.

Konstantina frames the reed and ripple or sun motifs with an irregular white border which sections them from an earthen backdrop, as if they are specimens of study suspended in a lantern slide. This composition references the practice of collecting and examining botanical specimens from ‘exotic’ outposts like Australia, during the “great colonial voyages” of Nicolas Baudin and Matthew Flinders, and the interpretation of these specimens through drawing and watercolour, as in the work of Joseph Banks, James Cook and Sydney Parkinson. By alluding to her subject’s life within this manner of composition, Konstantina’s work suggests that materials and so-called ‘artefacts’ from First Nations communities held by museums and institutions are not inert, but objects with living histories which have contemporary social, spiritual and practical uses in the communities where they are from.

Konstantina’s wider work is marked by observations and analysis of this nature; almost everything she encounters in her investigation of culture, colonialism, language and lore, she documents through a visual medium, accompanied by text in the form of fragments, reflections or aphorisms. Often, she will work with a particular theme in mind. Her series, Raining on Eora (2021−22), for example, took locations in the Sydney area as starting points from which to tell stories about their significance in First Nations culture through painting and writing. RE: Imagined follows this course of both revivifying Gadigal cultural memory and imagining a future for traditional practices.

DR. JULIE ADAMS IS THE INTERIM KEEPER FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF AFRICA, OCEANA AND THE AMERICAS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM IN LONDON. HER RESEARCH PROJECTS INCLUDE ‘ REIMAGINING A TAHITIAN MOURNER S COSTUME’ (2018 –ONGOING) . SHE HAS WRITTEN EXTENSIVELY ON THE HISTORIES OF THE PACIFIC REGION AND ITS MATERIAL CULTURES IN EUROPEAN MUSEUMS.

FROM 2011–2015, ADAMS WAS SENIOR RESEARCH FELLOW AT THE MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY IN CAMBRIDGE. SHE HAS AUTHORED AND EDITED NUMEROUS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDING MUSEUM, MAGIC, MEMORY: CURATING PAUL DENYS MONTAGUE (2021) .

FOREWORD

BY DR. JULIE ADAMS

MUSEUM STORAGE SPACES are often imagined as quiet and dusty, places where objects lie undisturbed, only rarely being interrupted by studious researchers and curators. The Oceania collection stores at the British Museum, however, do not fit this tired stereotype. Frequently filled with visitors who have travelled great distances to spend time with collections they have deep connections to, these stores are some of the most dynamic and emotionallycharged spaces in the whole Museum. Last year alone, our team welcomed behind the scenes 224 visitors from Australia and the Pacific Islands. While each visitor brings new experiences, desires, and opportunities for learning, I can honestly say that I had no idea how impactful the arrival of Kate Constantine (Konstantina) would turn out to be.

Following an initial scoping visit to the Museum, organised by her Parisian gallerist, Stéphane Jacob, in early 2023 Kate was quick to recognise the potential of the collections in storage and realised that she needed to return. Multiple follow-up visits over the last three years have given Kate unprecedented access to the collections and forged close relationships between her and British Museum staff. From the beginning, Kate’s research had clear parameters. While she was interested to learn something about the history of the British Museum’s holdings from across Australia, she was specifically focused on identifying objects that could be associated with the Sydney region and, therefore, have meaning for Gadigal people. From amongst those collections, she carefully set aside any items that she felt it was culturally inappropriate for her to engage with. What was left was only a handful of pieces, but these treasures have inspired a wealth of learning and creativity.

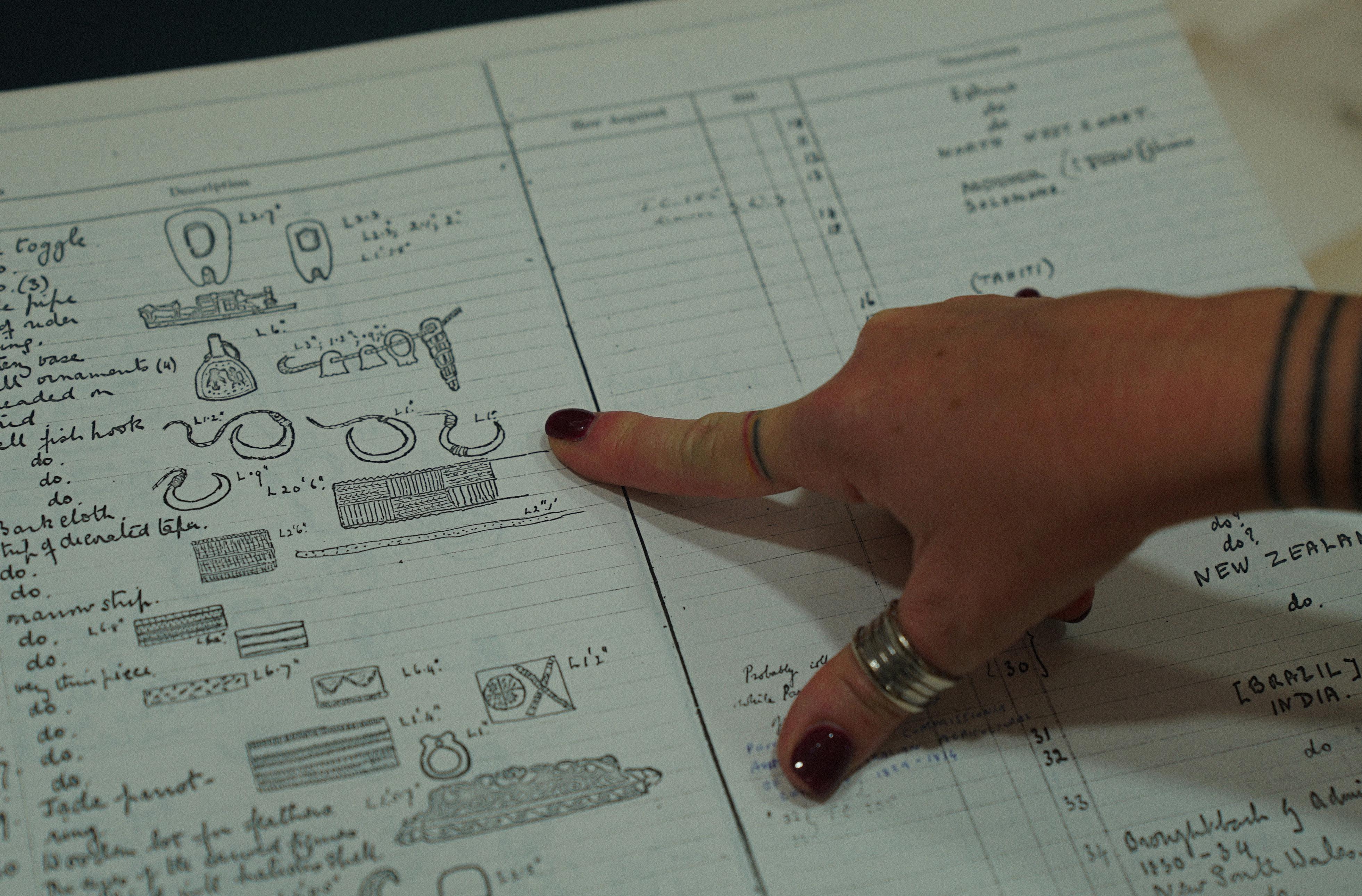

Kate’s deep engagement with the collections has been appreciated by staff across the Museum. In particular, she has found natural allies among our conservation team who love nothing more than looking at objects to learn what they can tell us about the past. Together, Kate and conservation colleagues examined reed necklaces using a Hirox digital microscope, in a bid to understand their construction and intricate decoration. On another

occasion, a group of us came together to examine what is described in our records as a ‘basket’. This simple looking object, made from a folded leaf with a stick pierced through the ends to create a handle, nevertheless revealed a multitude of complex stories. The microscope helped us to see the structure of the leaf and identify its species, while close examination of the interior revealed some small circular purplish stains, probably the result of berries that had once been transported inside. It took us some time to come to the realisation that a small square of European cloth on one side of the leaf was not a repair, but most likely a sign of ownership – a quick way for the person it belonged to to identify it as theirs. Kate explained that in the early days of the Port Jackson settlement, Europeans struggled to find drinking water. This leaf container would have been a valuable means of holding and carrying water and, as such, a possession that could literally save your life. Perhaps made by a Gadigal person, before later belonging to a European, its significance for each is literally embedded in its material form. These experiences of shared conversations and mutual learning were transformative for all those involved, and have changed the way this humble but significant piece is presented on the Museum’s public database.

On subsequent visits to the Museum, Kate painstakingly counted the number of reeds on a necklace, sketched the pattern from a section of a possum skin cloak and practiced the technique used to twist the fibre cords of a fishing line. Back home in Australia, all of this translated into a huge amount of work, as she set about harvesting and gathering materials and experimenting with the techniques used by her ancestors. I have enjoyed the WhatsApp photos that regularly appear on my phone first thing in the morning: crates of possum skins, bundles of cords made from hibiscus, and ochres ready to be ground up into pigments. More recently, she has shared some of the amazing paintings featured in this exhibition. Aptly named RE: Imagined , the exhibition showcases Kate’s first creative responses to her experiences at the British Museum. The collaboration continues, however, and I am so excited to be accompanying her on this journey and to see where it takes her next.

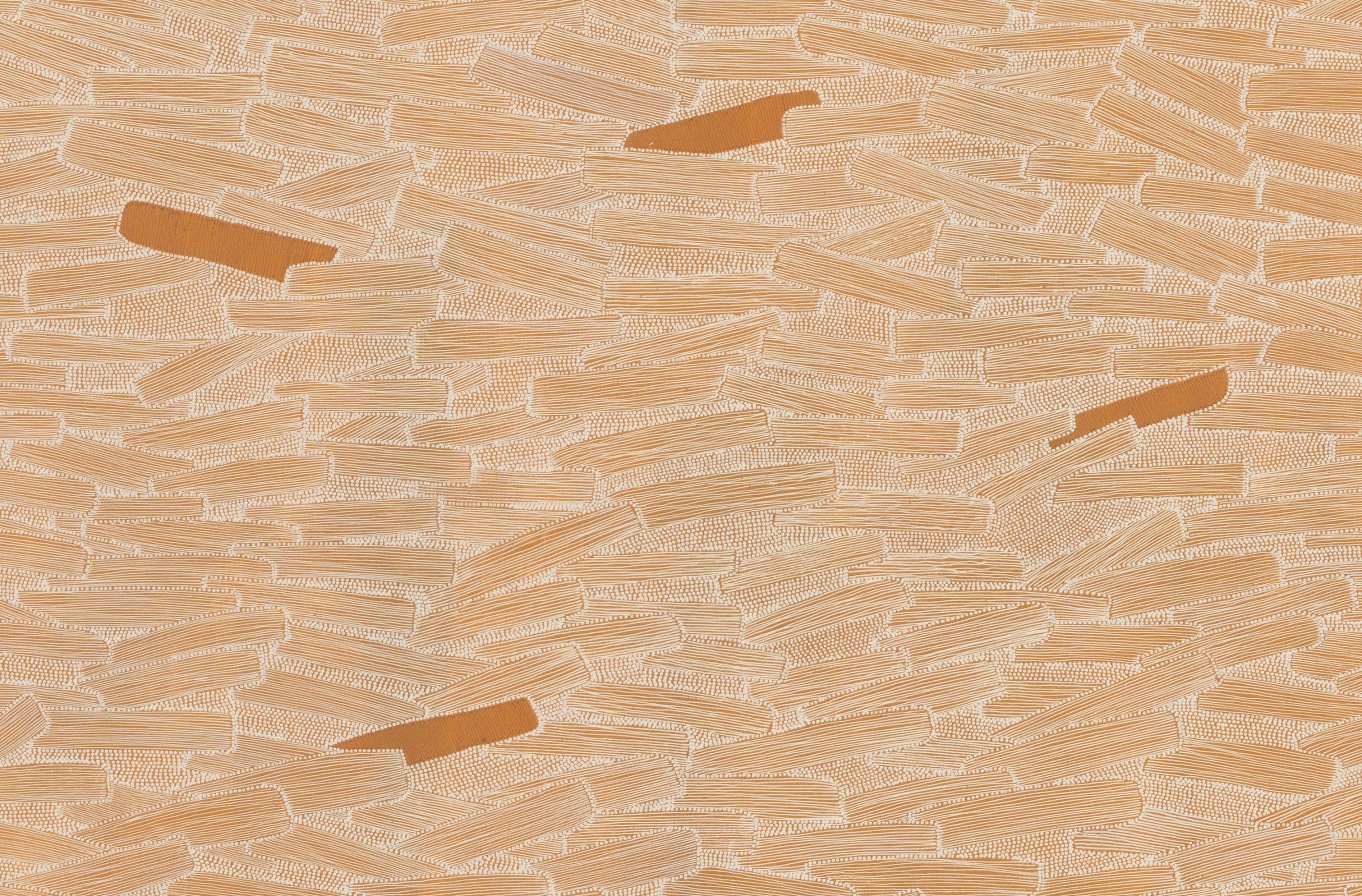

Konstantina, Ngara III (detail), 2025,ochre on linen, 91cm x 90cm. Image courtesy of Sergey Novikov.

ESSAY BY PROFESSOR LISA JACKSON PULVER

PROFESSOR LISA JACKSON PULVER IS A FIRST NATIONS AUSTRALIAN PUBLIC HEALTH EPIDEMIOLOGIST AND DEPUTY VICE CHANCELLOR, INDIGENOUS STRATEGY AND SERVICES, AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY, WHERE SHE LED THE SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND ADOPTION OF THE INDIGENOUS STRATEGY, ‘ONE SYDNEY, MANY PEOPLE’ (2021–2024)

JACKSON PULVER IS A LEADING COMMENTATOR ON EDUCATION AND INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA, HAVING MADE GUEST APPEARANCES ON THE DRUM (AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION) AND VARIOUS PODCASTS. SHE IS THE DIRECTOR OF THE AUSTRALIAN MEDICAL COUNCIL AND A GROUP CAPTAIN IN THE ROYAL AUSTRALIAN AIR FORCE SPECIALIST RESERVE.

ALL PARTS OF the Gadi are valuable. The flowers are used to sweeten water and make fermented drinks, and upon displaying themselves reveal direction, opening first on the warmer northern side of the flower shaft before blossoming fulsomely. This shaft in turn was then dried to make spears while the softer base was used for generating fire using the hand drill method.

The toxic leaves were eaten once treated properly, used as knives, binds and woven cords. Medicine was made from other parts of this plant while the resin was used for tools, waterproofing of watercraft and as a general adhesive and sealant. The methods of harvesting sustained the plants for hundreds of seasons.

In the early days of the colony the Gadi resin was ‘discovered’, and was used for a multitude of purposes including varnish, boat maintenance, pole coating, soap, fragrance, gramophone records and as church incense.

The colonial endeavour was not kind to the flora of this place. Sustainable methods were not used to harvest the resin and accounted for the loss of large numbers of plants, some of which being hundreds of years in age.

The Xanthorrhoea were – in the early 1800’s – the third most important export for the fledgling colony. The destruction of the mass of Gadi can’t be described.

Today, the remaining Gadi in and around Sydney can date to over 300 years, with some further away ageing magnificently to 700 years or more. These plants, and many others, live in the context of the lands, waterways, and skies of Gadi Country which itself have never been ceded or sold. Aboriginal peoples, Gadigal, are the traditional custodians of the lands that are now known as Sydney; this includes all the places where contemporary Australian society flourishes.

THE 28 SPECIES OF THE XANTHORRHOEA GENUS ARE ENDEMIC ACROSS AUSTRALIA. THESE ICONIC PLANTS ONLY OCCUR IN AUSTRALIA AND HAVE INHABITED THE INNER SYDNEY AREA FOR TENS OF THOUSANDS OF YEARS. LOCALLY, THEY ARE CALLED GADI FROM WHICH THE PEOPLE OF THE AREA, THE GADIGAL, NAME THEMSELVES.

When we acknowledge this history, we take up in earnest the opportunity to institute the relationships and sustainable practices that will heal and strengthen our collective character as a nation of many peoples.

Throughout mainland Australia, Aboriginal peoples host the oldest continuing culture in the world. The lands, waters, and skies of this continent have been known, loved and managed for tens of thousands of years. Despite the unique centrality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in this nation, significant challenges to the practice of culture and the recognition of sovereignty fundamentally remains.

This recognition relies on the simple truth that Australia has a history of custodianship and leadership that stretches back millennia. Archaeological evidence suggests that this continent has been the home of Aboriginal people for upwards of 60,000 years; the evidence further suggests that Torres Strait Islander peoples have been caring for the northern islands for over 9,000 years. This history is one of long sovereignty as expressed in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Recent history includes the fight for the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as people and for land rights since colonisation.

A full reckoning remains to be had in modern Australia regarding the acts that transformed this continent from one of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander custodianship to a penal colony in service to the British crown, and then to the federated states and territories of the Commonwealth of

Australia that remain in place today – where sovereignty was never ceded.

A pathway towards that reckoning is to centre Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices, knowledges and belonging in contemporary polity. This would be an active engagement in practical reconciliation and in keeping with an honest approach to self-determination.

There are an infinite number of ways of Aboriginal knowledge and of doing and of being, which include extraordinary things; science, medicine, astronomy, engineering, agricultural practises and land management, mapping and navigation, dance, ceremony, song, art, storytelling and most importantly – belonging.

For us, information and knowledge is transmitted from one person to the next, down the generations, and there are people in Australia today that have this type of knowledge from generations that number in the thousands.

And there is something to be said about living on a land, about loving a land, about calling a land home that has been just that – a home for tens of thousands of years. Being able to access that persistent and ancient knowledge of this land so that you can remain well, strong and knowledgeable throughout life and pass that on to future generations for the next tens of thousands of years is a real gift to the nation, and one that should be acknowledged and cherished.

"...THERE IS SOMETHING TO BE SAID ABOUT LIVING ON A LAND, ABOUT LOVING A LAND, ABOUT CALLING A LAND HOME THAT HAS BEEN JUST THAT – A HOME FOR TENS OF THOUSANDS OF YEARS..."

Then, BC (Before Cook), all the people knew who they were, what their names were, who they were connected to, and where they belonged. Today, like many of the world’s First Peoples, some Aboriginal people don’t know who they are, which families they are connected to, what language to use, or how to belong.

One thing many people don’t realise is that there were anywhere between 750,000 and 1.5 million people here when the British arrived in 1788. That was a reasonably large population who thrived and was sustained by this continent. Today we’ve got 25 million people, with way less than 1 million identifying as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent.

Today, many of us have different skin tones, some of us are born in the cities away from our ancestral lands, while many are reared in out-ofhome care. Many of us have blended families, with relations from all over the nation and from all over the world.

And yet we are still here. Aboriginal people – we continue.

- LISA JACKSON PULVER, 2025

KONSTANTINA & ANTONIA CRICHTONBROWN IN CONVERSATION

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING RE: IMAGINED KONSTANTINA SAT DOWN WITH ANTONIA CRICHTONBROWN (WRITER & RESEARCHER AT JGM GALLERY) FOR A DISCUSSION ABOUT THE UPCOMING EXHIBITION.

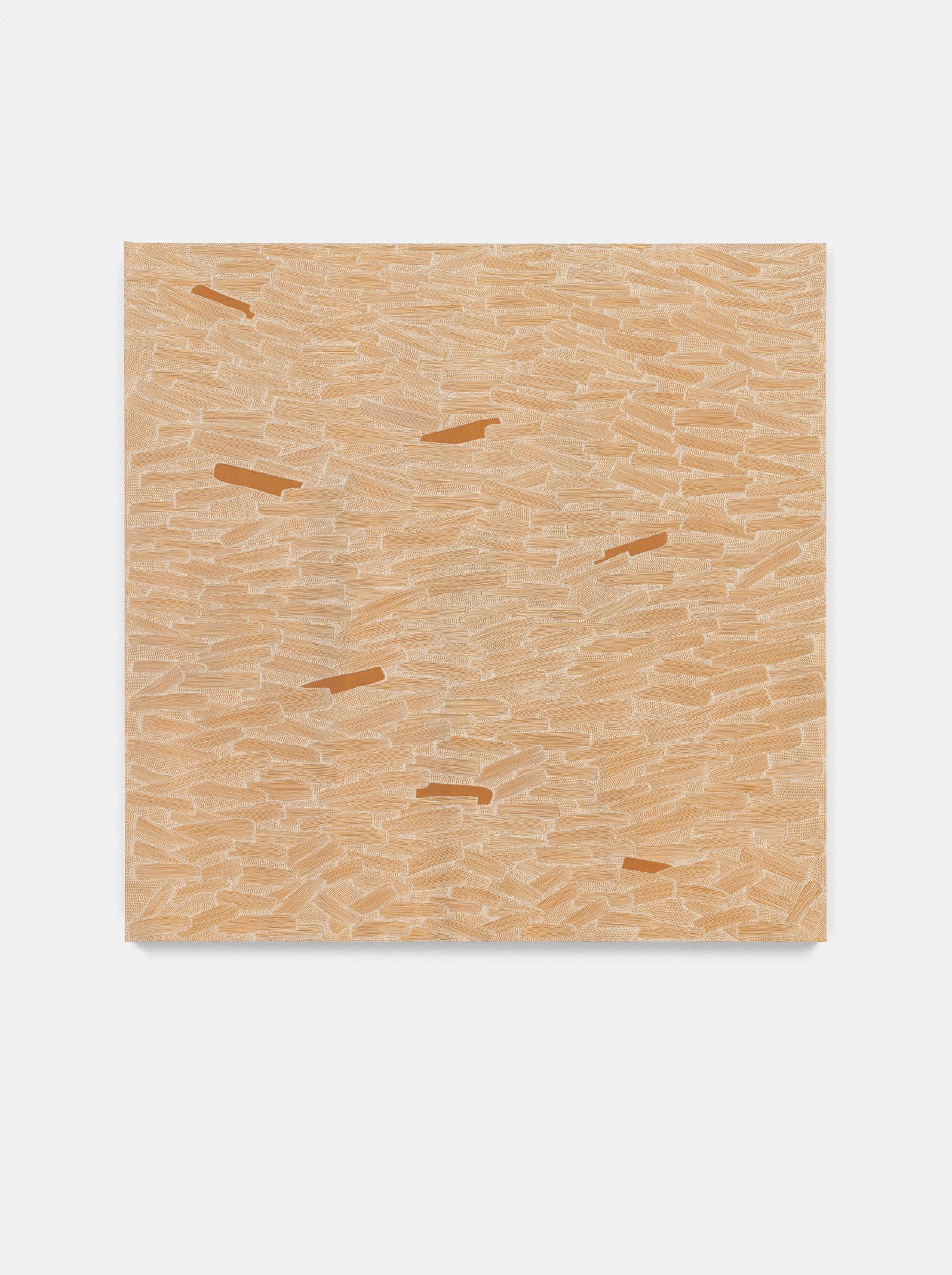

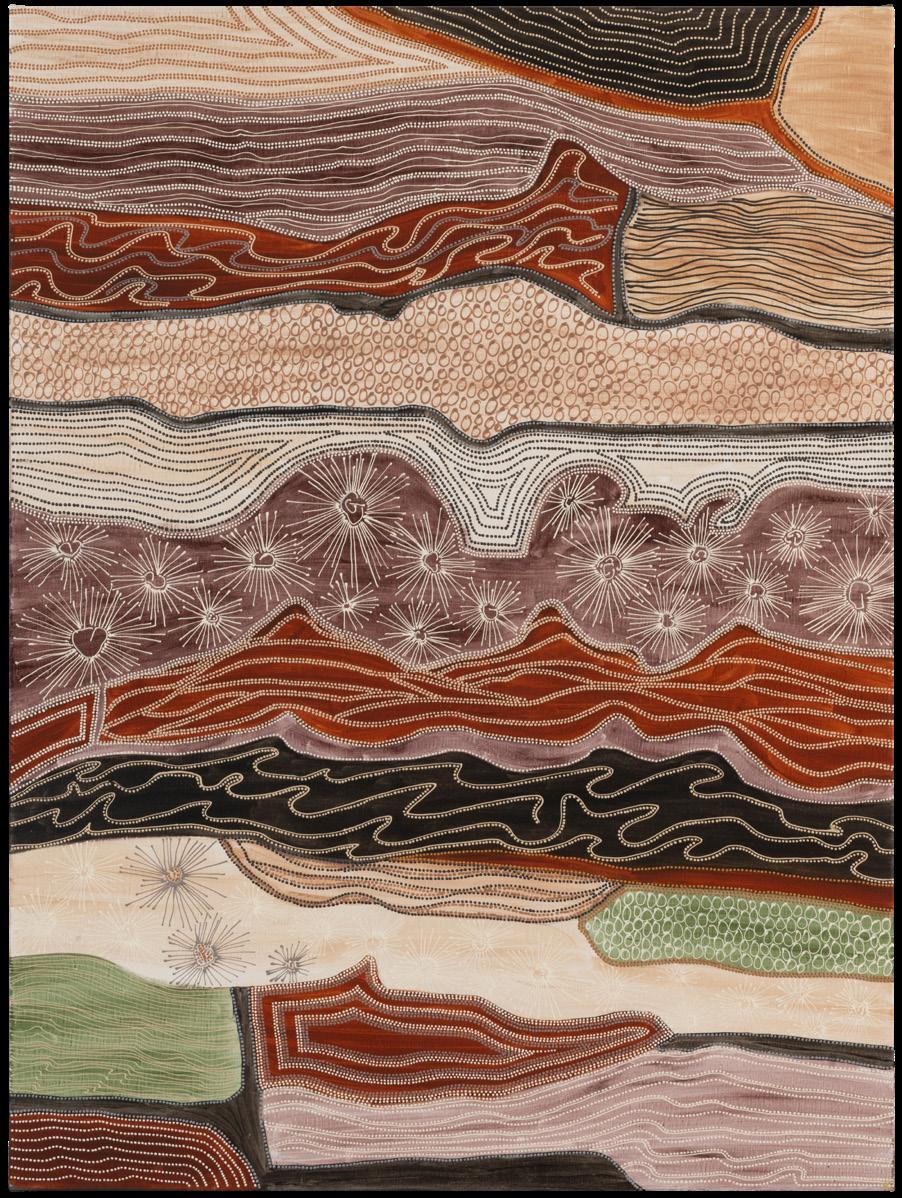

Opposite: Konstantina, Mari Budbili , 2025, ochre on linen, 140cm x 139cm.

Image courtesy of Sergey Novikov.

ANTONIA CRICHTON-BROWN Kate, RE: Imagined will be your first London-based showcase and for it you are presenting a suite of works inspired by objects in the British Museum’s Oceania collection which you examined during your ongoing research project with them. Can you tell me a little about how this project came about and what the central themes and concepts are for this series of works?

KONSTANTINA The project is rooted in my insatiable need to understand myself. I’m a proud Gadigal woman of the Eora Nation in Sydney and as such, my need to understand the identity of our community and my kin prior to colonisation has been the bedrock of my making for the last ten years. A few years ago, I was afforded the opportunity to go to the British Museum and ask questions, observe, touch and feel the treasures of the people that I am descended from in those archives. It was there that the research project came to light. For me, everything that I commit to canvas or that I make is an opportunity to discuss my people that only usually are whispers in the margins of history. Sydney was ‘ground zero’ for colonisation, and as such is represented by the huge amount of artefacts (as they are called by museums, but I call them treasures).

The British Museum have this huge amount of Gadigal and further afield – Eora, Sydney basin mob’s – artefacts as their treasures, but they don’t have accompanying stories. For me, these treasures are very beautiful and I understand the story of some of them, but it’s often one-dimensional in a museum context because there isn’t a huge amount left of the storytelling that 235 years between the dawn of the colony and today has erased. My need for wanting to understand ‘us’ – the Gadigal people – pre-colony is not to repatriate the physical treasures – although that would be lovely –but the knowledge, wisdom and Cultural understanding of materiality and creation which the treasures hold. RE: Imagined is the really joyful space within this very long research project run. It’s kind of the halfway point of my re-imagining the processes and understanding the making of the treasures from a practical and traditional perspective, and then casting my own post-colonised DNA, soul and heart, learning and understanding into re-making them. For me, this exhibition is the part of the project that is

ACB I wanted to ask for our audience in London, who are perhaps not so well versed with knowledge of what happened to Indigenous material cultures during the course of colonisation in Australia, whether you could speak a little to what you learnt about the history of the Gadigal through the course of your research, and how their culture specifically was affected by colonisation. Were there any discoveries you made which surprised you?

K Good question. The Gadigal are arguably one of the most noted within documentation. Gadigal land is the city of Sydney. The metropolis of Sydney is literally my Country. When people think of Aboriginal clan groups or Aboriginal tribes, everybody thinks of the desert. That’s the fait accompli – you think of people in big open plains with mulga trees and red dirt. My Aboriginal clan, the Gadigal, were literally at Sydney cove. Our extension was from Rozelle/Glebe, which is just outside the city, to Surry Hills and down to where the Opera House and the Harbour Bridge is. It’s really interesting when you start opening up the archives and you see the changes in language and descriptions used towards Aboriginal people over time. It’s very interesting to look at the betrayal of humanity in the descriptions of the colonial journals. That’s not just by the English, also Nicolas Baudin [French] did an enormous “discovery” endeavour to Australia in 1801 and collected many artefacts which are now at Le Havre in Normandy as well as across the continent. At the beginning, on discovering Australia, all the way through to the early colony, we were considered this ‘noble savage’, and ‘ savage ’ is obviously very derogatory, regardless of how you use it. It conjures ideas in your mind of people that will hurt you. Some of the descriptions are of straight-backed, good-looking, well-nourished Aboriginal people. There are more references to our great teeth than I can even tell you. Things started to get hard in the colony and the Second and Third Fleet didn’t arrive on time with resupplies. There was no food. At one stage, there were over 120 people dying a day from malnutrition and scurvy. And it was actually the Gadigal that kept the colony alive. To our long-term detriment, but also because

of our gracefulness and our sympathy and empathy for the human need, we kept the British alive. We kept the officers alive as well as the convicts. There are quite extensive journal entries where women particularly would take the other women out to show them how to forage for greens, because they had bleeding gums and scurvy, and the women knew what that was. Then, once the need state crosses over and the colony is no longer reliant on this let’s-help-each-other-to-survive dynamic, the colony’s language becomes, “they’re savages, they’re cannibals, they’re drunken morons.” Even if you look at the lithographs that are held by some of the French museums and also in the British Museum, there are some really beautiful renditions from the time of Nicolas Baudin, that is, the French adventurer. He took an army of artists with him, so his journey was mainly about botany and art as opposed to finding new land. But it’s even the way that those drawings change. They go from being these really beautifully detailed ink and watercolour sketches of people who have muscular bodies and are suited to the terrain, to this drunken, miserable revelry. That coincides with things like the smallpox epidemic. There are many academics who write that they think that the Gadigal as a clan group got down to only three people once the smallpox epidemic went through just before 1800, and I think – whether that is actually accurate or not – what it does is it displays to you how fragile we became within a colony that we helped to survive.

ACB How has encountering this knowledge informed your understanding of your culture, your people and yourself, and how has it affected the work that you do? How can we see this influence in RE: Imagined in particular?

K We live in a contemporary, fast, consumable, commercial world, which is unfortunate, I think, for all of us as human beings. A lot of our materiality that we used in the adornment and making we had been practicing for 65,000 years, so we had actually got it right. For example, the resource-rich materials that we could use to make useful items that we needed to carry water from place to place, or to keep a baby warm once they were born, or to birth children without having septicaemia or other birthing issues. For me, that’s been my ‘a-ha’ moment. Aboriginal people, and certainly my family – my kids, myself and my husband – live by the rules of reciprocity, not necessarily just with other humans but with Country. You only take what you can use today. There’s no stockpiling. There’s no refrigerator with seventeen weeks’ worth of meals in it. You fish this morning, so that you can eat for lunch. You harvest the lomandra, or you harvest the possum skins that you need because your baby’s cold today. You do what is needed and required for the moment. I think that sort of living, a lot of farming, a lot of art has come from that way of being. I think that people who are makers understand that with a lot more ease than perhaps someone who works in an office environment. For me, one of the big callouts with this project with the British Museum has been realising that it’s key to understand what you need, how much of it you need, knowing exactly the number and knowing exactly when it’s in harvest. It’s understanding seasons, it’s understanding ecology, it’s understanding geography,

it’s understanding the cycles of plant life, but it’s also understanding what the end goal is and what you need materials for. I think we miss out on that. In a disposable lifestyle, which we all have to some degree, we are reliant on things coming to us in that fast-moving, consumer goods way. But slowing down has shown me that I couldn’t rush it. I’d really hoped that this project in its entirety would have been done in two years, and for me, looking down the barrel at five is actually okay, because it’s needed me to take five years to get there.

ACB You’ve touched on the various phases you’ve gone through to realise the end goal, which – correct me if I am wrong – is remaking the objects that you researched in the British Museum and re-imagining them through a very contemporary lens using modern as well as traditional materials. Can you tell me a little more about your work with the British Museum?

" FOR ME, THE REASON WHY A PROJECT LIKE THIS IS SO EXCITING IS BECAUSE THIS IS THE BEGINNING OF THE DOOR BEING OPENED. "

- KONSTANTINA, 2025

K Okay, to start with, why did I do it? At the end of Covid-19 lockdown, I had been having a conversation with the Sidney Nolan Trust about a show that they wanted to put on. It was a First Nations show, and they wanted to show a collection of artworks from what I would call ‘traditional’ – mainly desert, APY Lands and Balgo artists – all the way to my brand of art, which is obviously at the very contemporary end. We were discussing that as an out-of-lockdownmoment when that would happen. I did a three month residency over there. Most of the time I was at the Sidney Nolan Trust in Wales, and the rest of the time I was in France. And I stumbled across a document that was a particularly horrible piece of Senate Inquiry legislation that I hadn’t been able to find anywhere else because it wasn’t in creative commons yet or available for general public use. I also couldn’t get it because I wasn’t a British citizen and, because Australia wasn’t its own country until 1901, I wasn’t able to get it from the UK government. I found it in Sidney Nolan’s library, and it was the original Senate Inquiry and Witness Reports from 1836, and then the final report in 1937 which became, for us, legislation and was the ‘Protections Act for Aborigines’. It is why my identity is such a crucial part of my painting, because my greatgrandmother was part of the Stolen Generation. She was taken from her family at a very, very young age and rehomed, and therefore didn’t grow up in her Culture, which is another way colonialism had a huge impact on all Australian Aboriginal people, not just Gadigal people. So, it’s not light reading – it is horrendous. And it broke my heart. It’s a few thousand pages and I read it in four nights with a couple of bottles of wine, and it tripped my nervous system into needing to understand why. Why other humans could be so brutal, and why it broke us in many ways. It didn’t destroy us, but it broke us. I think Aboriginal people’s faith in humanity – other than

themselves – has been really tested in the 235 years of colonisation. That started my conversation with the British Museum, who at first didn’t want to know me. I then got properly introduced by a gallerist friend of mine who looks after me in Paris. So, I jumped on a train and I went over and I met with the curatorial team that look after Oceania, which the Australian collection sits within. And we made fast friends. What I had expected and what I turned up to were two really different things. What I expected in the humans that were looking after these things, or were the custodians of our treasures, was that they would be very guarded, very standoffish, not very friendly and not acquiesce to any of my requests. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Even the way that they describe themselves is as ‘temporary custodians’ over the treasures that would one day make their way back to where they belong. I think that is a really beautiful way for my people to feel like somebody – if it’s not us and not our kin – has stewardship over these things. I think that their reverence and respect for the collection is something that I was quite surprised by.

ACB It’s interesting to hear that museum conservationists and specialists describe themselves as ‘temporary custodians’ in relation to the objects that are entrusted into their care. I think it really speaks to the kinds of contemporary approaches institutions are now adopting towards the objects in their collections. What are your thoughts on the ways the British Museum and institutions more broadly have dealt and are dealing with objects taken from Indigenous communities through colonisation? Should more traditional methods of care be integrated on an institutional level, perhaps those which respond more closely to Culturally relevant methods of care?

K At the end of the day – to use the British Museum as an example –it’s not even a place where repatriation is possible currently because of the way that it is set up. The British would have to go to a referendum to have

the British Museum sanctioned away from the monarchy, because it’s – to my understanding – the King’s collection, it’s not the British people’s collection. You would have to go through these billions of dollars of upheaval. Is that possible in the future? I think it probably is. But – to backtrack to the earlier part of your question – the ideal scenario is that all the treasures from all the places around the world go back to where they came from, and people who want to travel to a place, visit the treasures from that place in that place. But that isn’t the case. So, we have to work with what we’ve got. And unfortunately, that system is way more challenging to unpick the seams of than it is to talk about best practice methods. Historically, at all museums – and I have visited and researched at many of them, but obviously mainly at the British Museum – there have been some questionable practices, which I’m quite sure they will tell you themselves. Was it best practice at that time? I don’t know. I wasn’t there in the 1800s. A lot of things were sealed with arsenic, so even today some things have labels like, “Do not touch this without gloves.” All of our treasures are made from natural materials so it would either be to get bugs out of them or so that they don’t disintegrate. Some things are varnished with oil varnish because that was considered the best way to keep the treasure in its best state at that time. We know a lot more about conservation now. We know that those practices are completely obsolete the world over. The other question I get asked a lot is – and it’s obviously quite controversial – if they weren’t taken and they hadn’t been preserved, would they still exist? Because what we now consider as treasures, at a moment in time for us were our useful tools of existence. They weren’t treasures, so they weren’t kept in a cool, dry, dark place. They were used. The only reason we made them was because they were useful. Now today, given what we know has happened with 20/20 hindsight, of course they’re treasures. Of course we want them in our own personal collections, or in our own Aboriginal-lead collections. Of course we want them cared for by our kin and community. But there is also this long tail question of resources. So, this changes the lens, and it

makes the question impossible to answer.

ACB It’s a good question. I suppose, obviously institutions like the British Museum have the funding to deliver on expertise and that’s often because of the objects in the collections. It’s partially because of these objects that institutions have income. So, in a utopian sense…

K *Laughs* in Nirvana.

ACB …if these objects were in Indigenous-led organisations in Australia, there would be funding available for training and for education to receive the necessary qualifications to care for these objects and, what’s more, perhaps in a more Culturally relevant way.

K But therein lies the opportunity. For me, the reason a project like this is so exciting is because this is the beginning of the door being opened. There hasn’t been a lot of consultation with the original peoples of the collections, and this isn’t just Australian Aboriginal people, this is Indigenous people the world over. A project like this really shows the willingness on both sides to get to a place where there is a really meaty conversation to be had. I will back that up by giving you the real-life example of what was supposed to be a two-year research project with no necessary full artistic outcome which has turned into a five year project with three exhibitions, seven trips overseas with my Gadigal elders coming over to view the collection paid for. One of my elders is starting his own research project on the male items because that door has been opened. It looks like there’ll be the publication of a book. You can’t be it if you can’t see it. How do I encourage my niece who is just starting her first year of archaeology at Sydney University to be the person that is going into these museums and galleries and having these yarns about custodianship and kinship and the ways of viewing things from a really academic and well-rigoured perspective if she

can’t see me breaking down the walls. So again, RE: Imagined isn’t just reimagining the artefacts, it’s re-imagining the system. The whole system.

ACB What I’d like to ask you next is about this relationship between ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ arts that you raise when you talk about your work in comparison to ‘desert’ painters. In the Indigenous contemporary arts field, there is a huge debate about the use of these terms. What is your perspective on what makes ‘traditional’ versus ‘contemporary’ practices for Indigenous artists?

K Look, that’s an interesting one in itself. For us, art was about communication, it was a form of language. I think traditional art making practices are more about communication styles. They talk to mapping, they talk to aerial geography of places, because that’s what traditionally our artwork was for. Traditionally our artwork was saying, “whales are over there,” or “the mullets run that way,” or “this is a ceremony place,” or they were telling communication stories. ‘Desert painters’ as a general rule, and I talk about ‘desert’ – that’s a homogenisation of the tribal groups of which there are many within the interior of Australia and were the last colonised because it was such hard land and such a hard place for the colony to get to and to reach – they have continued in their arts practice of using their visual symbolism as a form of communication tool. It’s like an extra language. We don’t have a phonetic (written) language, we only have an oral language as Aboriginal people and a visual language. So, their visual

language remained really strong because they weren’t colonised until much later. If you have a look at the odd 2000 rock engravings on Eora Country, which is where I am from in the city of Sydney, of which a few hundred still exist, you will see a similar visual language to the visual language of ‘desert painters’. I find it really interesting when there’s a big debate about eastern seaboard – that is, Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria –artists using dots, because there are an enormous collection of archival, but also living, rock engravings that show that the people that I come from have also dot painted for millennia. It’s just that our practice, or that conduit to our practice, was disrupted a lot earlier and for a lot longer and in a much more violent way than the peoples of other parts of the country that were left alone, some up until the early 1900s. We had an extra 150 years of colonisation of not just our oral language, but of our visual language. So, when you look at artists from places that were colonised much later, which is usually the interior as a general rule and Western Australia, they held onto that traditional practice of mark making as a communication language for much longer, which has transferred from rock or sand or body to canvas very seamlessly. For me, in terms of the difference between what is considered in some regions, ‘tribal’ or ‘traditional’ Aboriginal art versus what you see coming out of a contemporary zeitgeist of Aboriginal Australia, which is mainly down the eastern seaboard, is a difference in colonial construct, but it’s also a difference in lived experience. I can tell where somebody is from by their paintings and I think that most Aboriginal people can. It’s a language unto itself because it’s a really beautiful blend of your identity. I would be being really inauthentic and insincere if I tried to paint like someone from the desert. I have never lived in the desert. I was born in Camperdown, which is in the city of Sydney. It’s my aunty that gave me the nom de plume ‘concrete Koori’. I’m a concrete Koori. I went to a university. I drove a car at sixteen. I didn’t live in the bush. I didn’t have the opportunity to even participate in things like bush food until I was in my 20s. I think, as an artist, authenticity is the key to being able to formulate and to create a visual language that is true to your experience, regardless of Aboriginality or being non-Aboriginal. I think every artist’s existence and their influences – whether they are environmental or human – that’s what shapes you, that’s what shapes your language. But it also shapes your intention with what you want to say. So, I think that the big distinction between ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ is not about how black you are, it’s also not about where geographically you come from. I think the interpretation is how long you’ve been colonised for in some ways. And that change is quite evident in practicality.

for four years in which precision and geometry were important. I’ve got a marketing degree and a Masters in business administration. My lived experience has been ‘be precise, be accurate’, so my work is never going to be smudgy or really loose and flowing. I haven’t been trained with the fluidity of painting by a river bank. I was in university labs looking at how to create things. My lived experiences are being integrated into Western society and having those experiences as much as I did my Cultural experiences, and that blend is what you see.

ACB In what ways does your work respond to the current political climate in Australia?

"IN THE AUSTRALIAN LANDSCAPE POST-COLONY, JUST MAKING PAINTINGS, WHETHER THEY ARE BEAUTIFUL OR NOT, IS AN ACT OF REBELLION. "

K I think that we’re in a really bad place. I’ll be really honest. Post the Voice Referendum not getting up a couple of years ago, it’s actually given creative license to people who are really uneducated. It’s given them the opportunity to be really loud and proud about their racist ideologies and their views on Aboriginal people. I think that it’s very safe to say that the racial tensions in Australia are much worse than they were, say, five years ago. I do think, however, that there is a really deadly, brave, courageous amount of artists that are coming through the ranks that are really stepping out and hard. They don’t care about being politically incorrect, they don’t care if they tread on toes. We (urban-based artists) live in a zeitgeist of ‘Other’ whereas I think a lot of traditional painters still live in a zeitgeist of ‘community’. We live as the Other in big urban metropolises, not just of white people but of immigrants from all over the world. So it’s almost like a rebellion against the system that this big, up-and-coming, deadly crew of people with voices – but also with amazing intent and integrity in their practice – are pushing those political boundaries and are using materiality in a really different way that is non-traditional. They are still Aboriginal artists who are keen and proud of who they are traditionally and where they come from, but use the means and the substrate to push against this Otherness.

ACB Your thoughts on Otherness remind me of a quote from Gordon Bennett: “‘Aboriginalism’ has been categorised by an overarching relationship of power between coloniser and colonised… Aboriginalism essentialises its objects of study: Aborigines are manufactured in ontological or foundational terms as an essence which exists in binary opposition to non-Aborigines, and which is not subject to historical change” (Bennett, 1996). Can you speak a little to that quote and how it relates to Indigenous contemporary artists like yourself?

ACB Stylistically, then, how does your lived experience transmit into your work? What can we see that makes your work different from the ‘desert painters’, for example?

K I think materiality choices. Even stylistically I have a really precise idea of what I want to create before I hit the canvas. I studied architecture

K I love that quote. I’ve actually used that quote in an essay previously. I think it’s curatorial clickbait in a lot of ways because it’s argumentative and thought-provoking. Aboriginalism only exists when there is something to push it up against, something for it to be compared to. You can only have black if you have white. But what is grey, and what does

grey look like, and who occupies grey space? Grey space is, for me, this really beautiful whirlwind of artists that have really significant intention and sincerity that are trying to rewrite their own identities – but also their kin’s identities – back into a landscape that kicked them out, that removed them – physically removed them from their parents, physically removed them from political systems, physically changed the landscape of Aboriginal people. Now, there is this huge ground swell for rhetoric like, “We don’t need permission to play in this landscape, we’ll play anyway.” In the Australian landscape post-colony, most modern and contemporary art – all the way from Emily Kam Kngwarray, all the way through to Tony Albert, Dan Boyd, Kaylene Whiskey, Aretha Brown, and many, many others – is an act of sheer rebellion. Just making the paintings, whether they are beautiful or not, is an act of rebellion. In 1837, there was an Act passed by the British government that said any Aboriginal person that looked white or had any amount of white blood, was to be removed for their own good and taken to a mission where they would be broken. You could not speak any other language other than English and you were trained for domestic service. I would say roughly 80 – 90% of Aboriginal people today come from those humans that were broken, that were removed from their mothers, that were removed from their Country, that have so much generational trauma from being considered the Other when in actual fact this country – this physical country, but also the spiritual manifestation of Country – was ours to begin with. It’s not just a dislocation of family, it’s a dislocation of being able to talk to each other. If you were ten and removed, and you only have one language, and you end up with thousands of other kids in a mission, and they all speak different Aboriginal languages, and the missionaries say, “You can only speak English,” how do you speak to each other? You don’t know the language. You’re isolated. You’re broken. You don’t have family. You don’t have love. And then, you’re sent to be a maid or a janitor or work on a cattle station. We come from that trauma. We live in that sphere. The people that we are directly descended from come from that trauma. So, the fact that we can wear a nice dress, or wear a good suit, and put on our red lipstick, and make art that makes people pay attention to our stories is an intentional act of rebellion in its essence.

ACB I’d like to ask you a question about how you manage to channel all the pain you just described and find ways to create this avenue for joyfulness and Cultural integrity in your work. With the weight of all of this trauma, how do you use your work to transform it?

K There’s a really good saying that says, “You don’t tell horrible stories to children, because you’ll make them horrible adults,” and for me, as a mum and as an artist and as somebody who is making in the Aboriginal world, I want always for my children to show up proud of who they are, more proud than I could be as a young person, and even prouder when they get to be my age. I cannot produce that effect in those little humans without showing them something amazing, because they still believe in Santa Claus, and they still believe in fairy tales, and so I have to make our Culture as joyful as those things to participate in in order for them to come on the ride. I probably hold a lot of the burden of trying to work out as a mum how to communicate things to them, and my arts practice is something that allows me to do that. It gives me the space, the mental fortitude, the meditation while I’m painting – the deep, deep meditation on how horrible a lot of this is – to try to turn that into stories that in their lived experience will become their fairytales that they tell their girlfriends or boyfriends as they grow up, and that they tell their children. I call my youngest son Baby Bird because his totem is a magpie. He walks around everywhere and goes, “I’m the magpie, I’m the boss.” I think that all human beings – if we strip away all of the crap that the world puts on us and all the responsibility that modern life puts on us – we want to believe in that beautiful fairytale. What I try to capture in the paintings is the beautiful essence of the story that hasn’t changed since time immemorial. And yes, it might be pretty for a wall, but it is also something that has a beautiful, fulfilling story that you can keep with you forever.

ARTWORK PLATES & DESCRIPTIONS

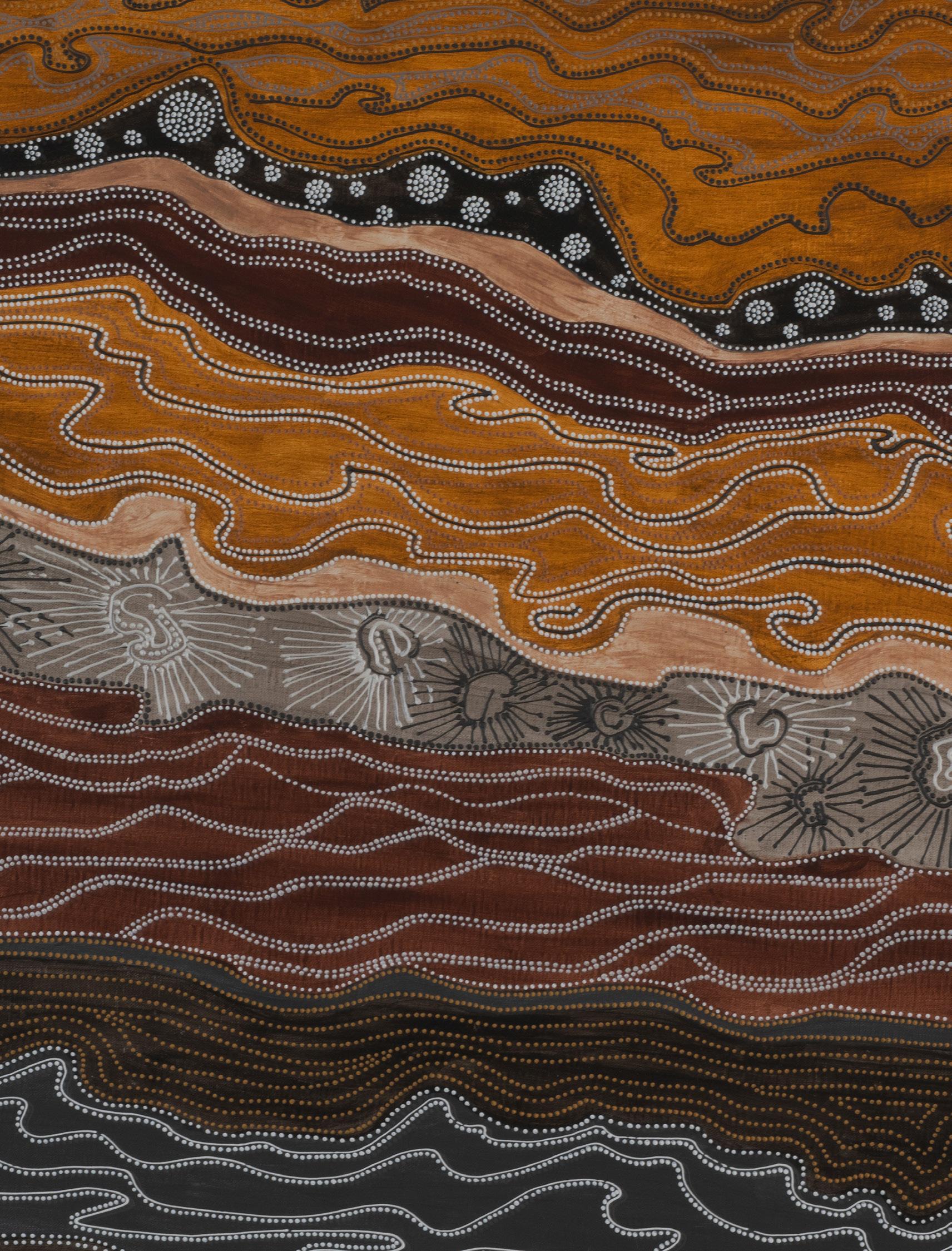

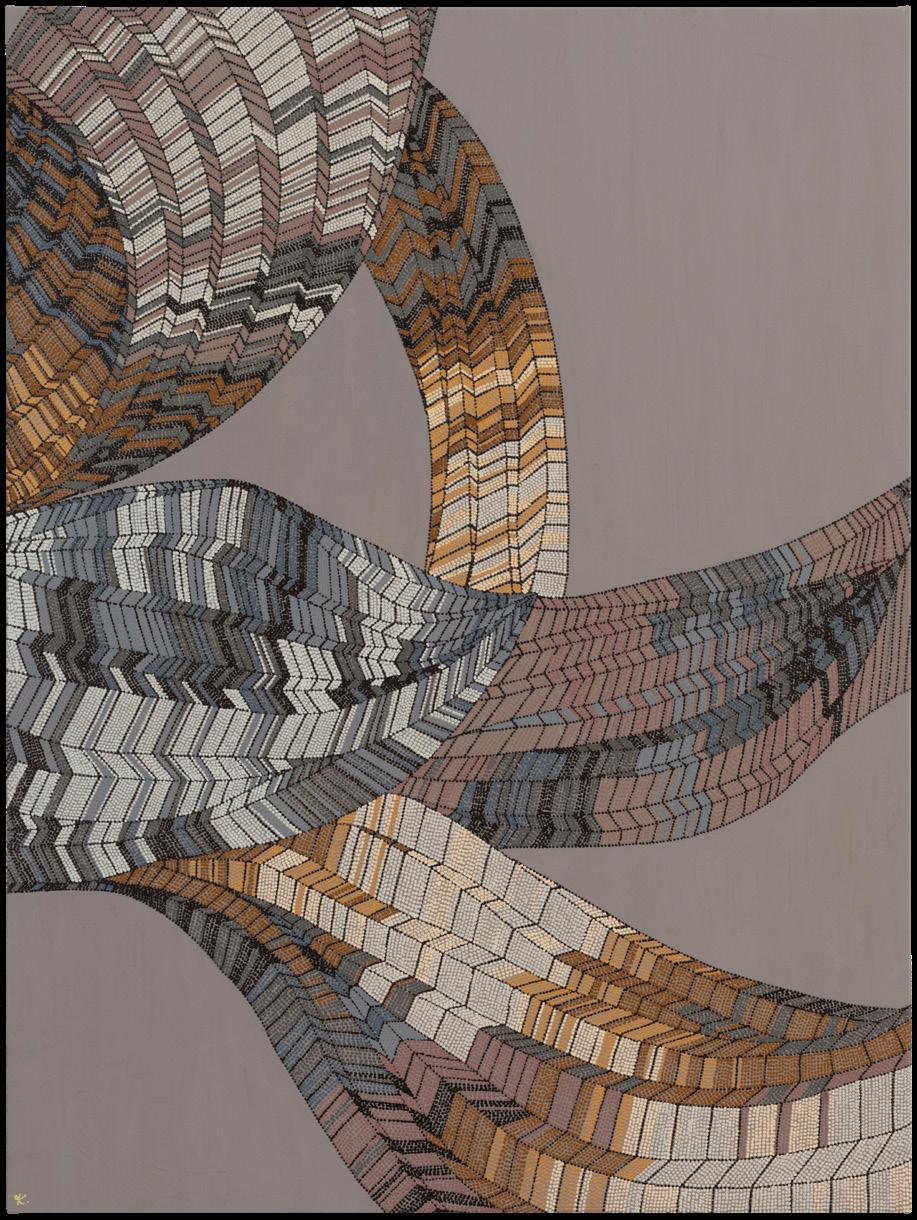

Konstantina, Murrira I (detail), 2025, acrylic on linen, 151cm x 100.5cm. Image courtesy of Sergey Novikov.

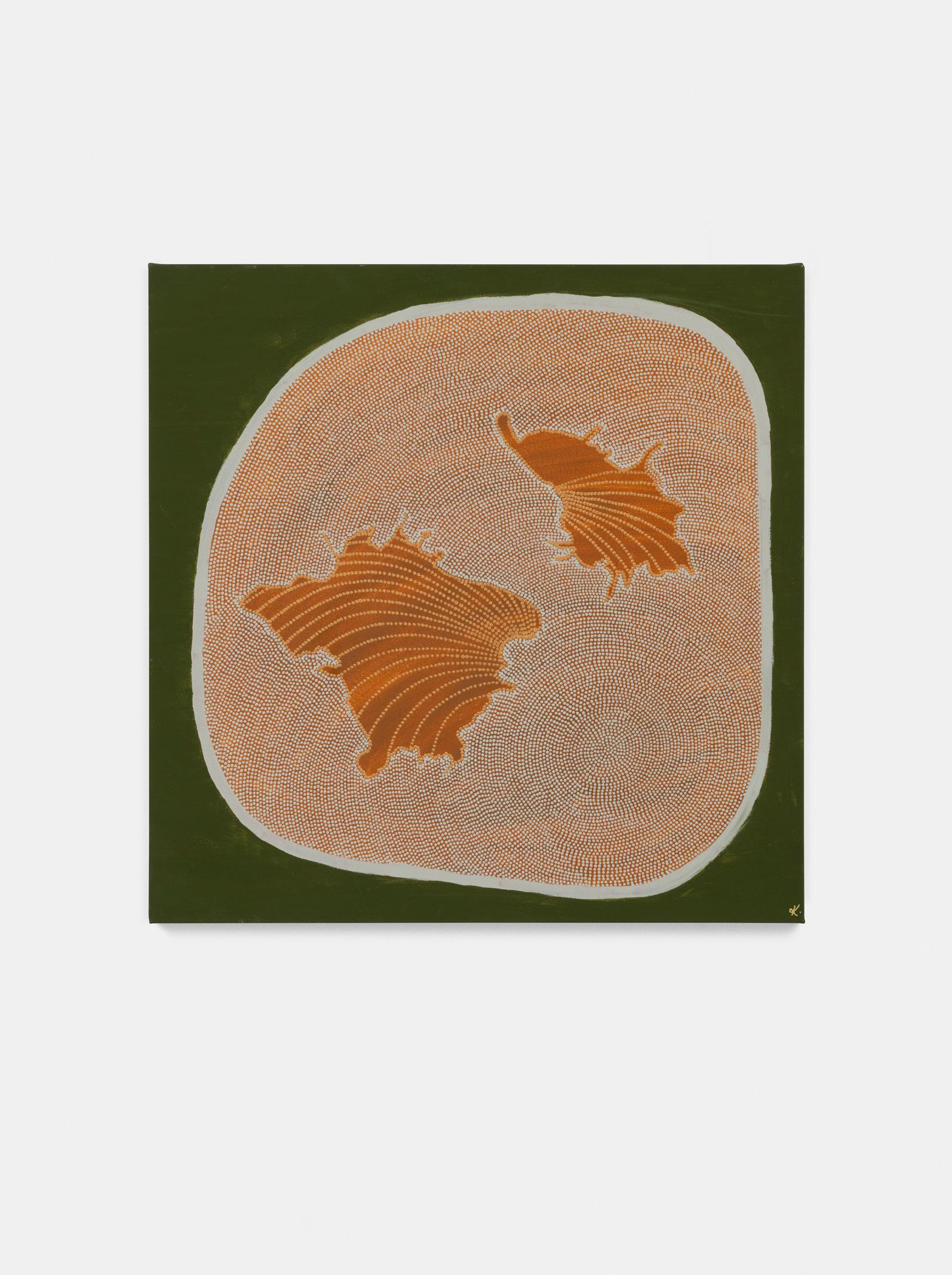

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: TO SEE, THINK AND FEEL.

Literally to sit in space and dwell on the slowness and deep knowledge it takes to turn a natural element into something useful for human purpose.

NGARA

[na·ra] v.

Konstantina, Ngara I, 2025, acrylic on linen, 75cm x 75cm

Konstantina, Ngara III, 2025, ochre on linen, 91cm x 90cm

Konstantina, Ngara II, 2025, acrylic on linen, 151cm x 100.5cm

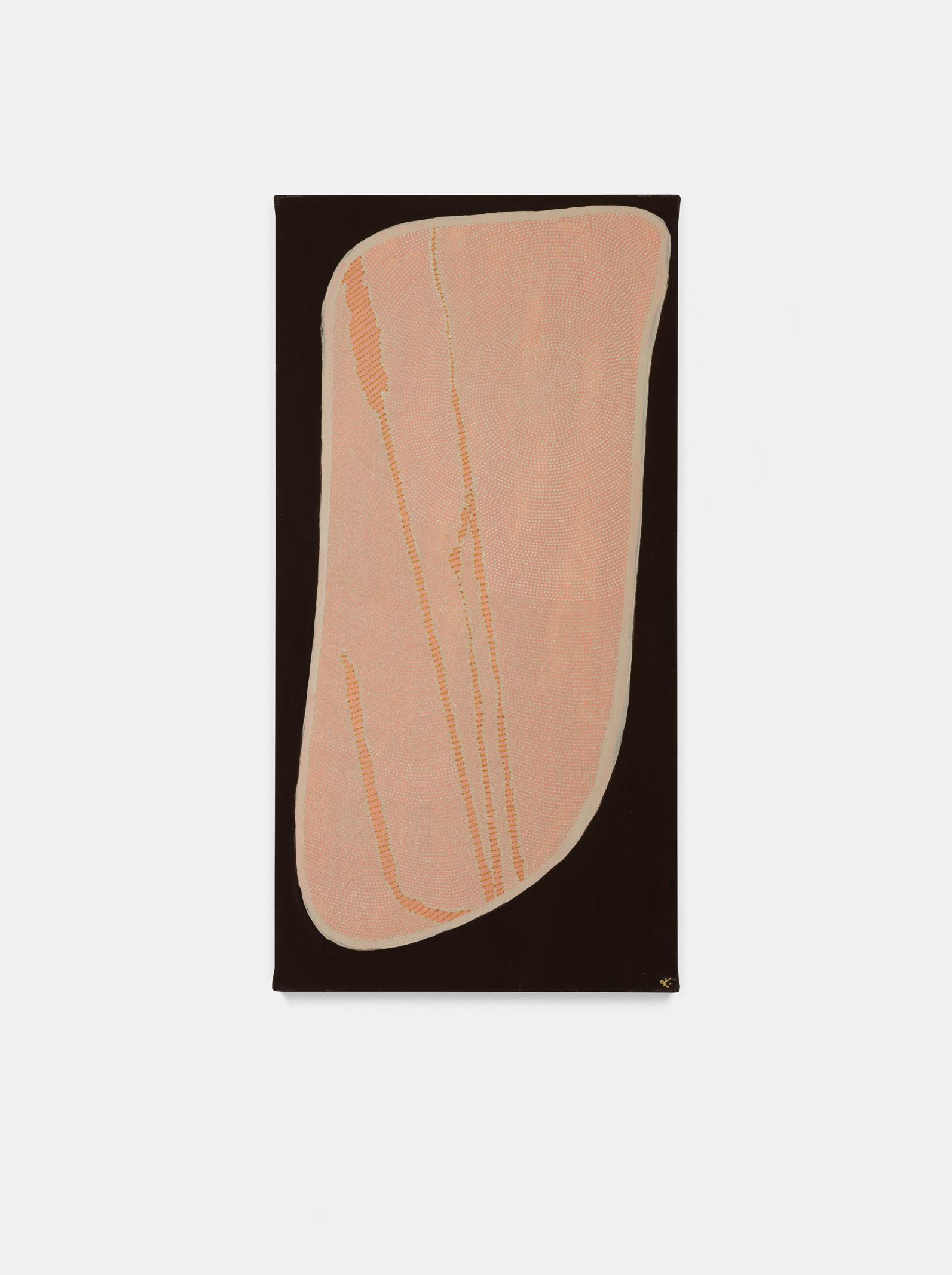

NARANG BARRABA

[na·rung bar·aba ] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: SMALL REED.

Gadigal word for the reed or bulrush from which we make our beautiful necklaces, waistlets and chaplets. Harvesting these has been tricky, as they are seasonal, and take six months to dry out ready to be used in this ornamental way. A practice in patience, time and consideration, as well as in unadulterated beauty.

Konstantina, Narang Barraba, 2025, acrylic on linen, 79.5cm x 40cm

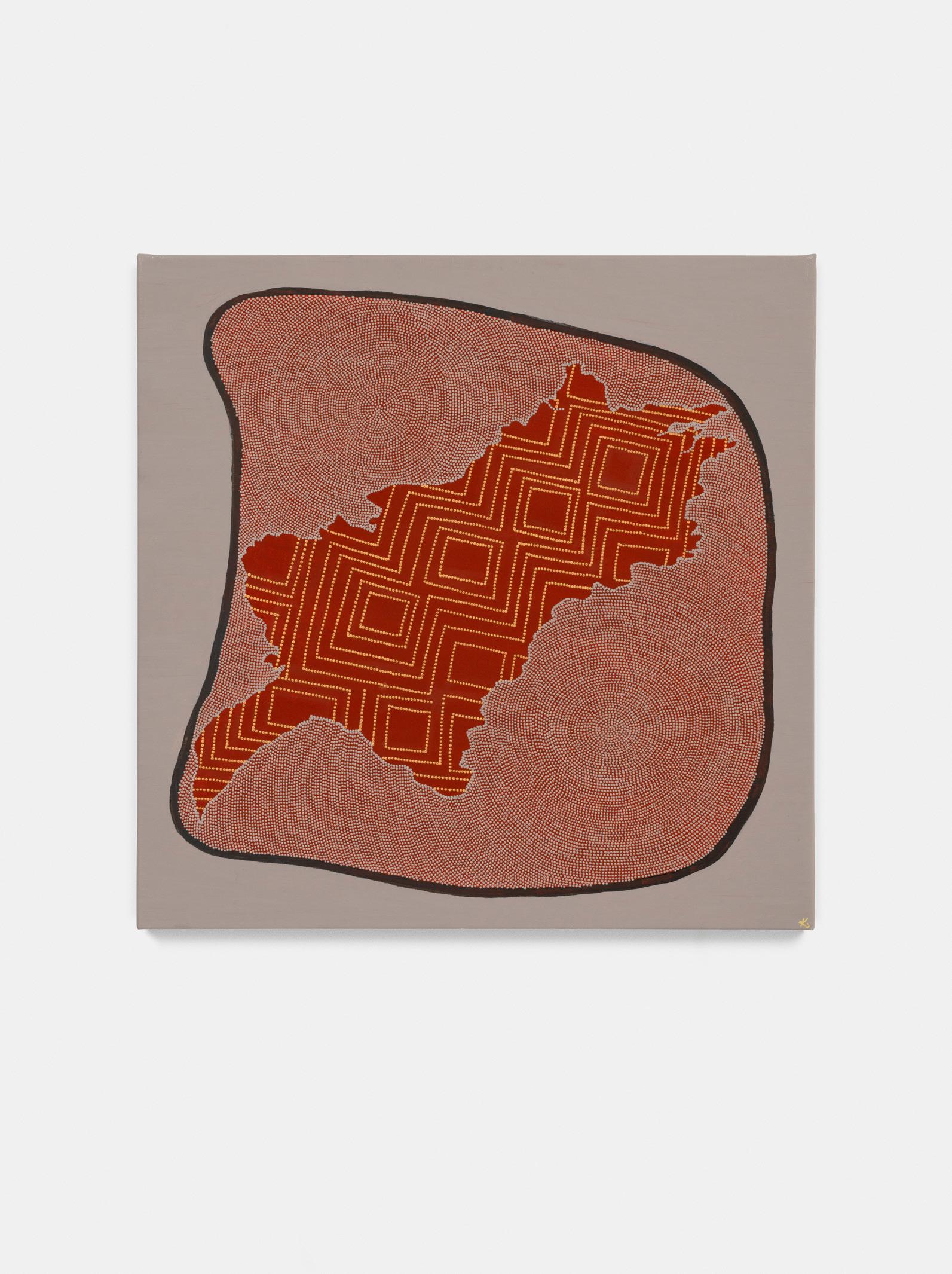

[bar·aba] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: REED OR BULRUSH.

Gadigal word for the reed or bulrush from which we make our beautiful necklaces, waistlets and chaplets. Harvesting these has been tricky, as they are seasonal, and take six months to dry out ready to be used in this ornamental way. A practice in patience, time and consideration, as well as in unadulterated beauty.

Konstantina, Barraba, 2025, acrylic on linen, 121cm x 121cm

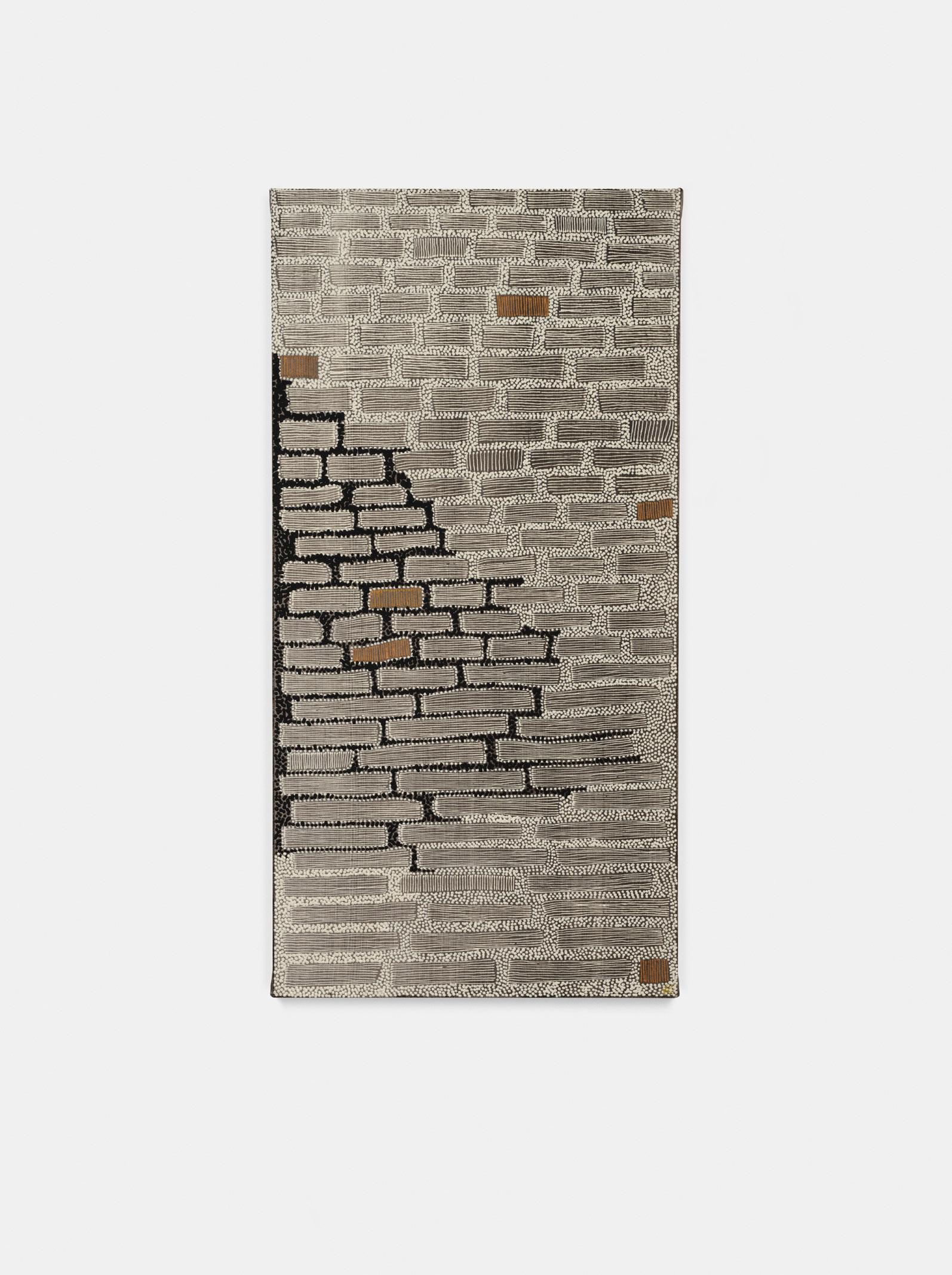

BARRABA

[bum·al] n.

Bamal has been used in the creation of paint for ceremony and celebration and is well known for both. It has also been used to create a waterproof method of sustaining fire in Nuwi (bark canoe), for rock painting, and for the adornment of possum cloaks. Bamal in a contemporary context has been used for the archaeological carbon dating of middens which allow us to know the length of time particular sites and camps were used by our people.

The physical earth, its pigment and its decay are such an important part of our bigger Cultural story.

Konstantina, Bamal I, 2025, acrylic on linen, 90.5cm x 75cm

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: SOIL, EARTH, CLAY OR OCHRE.

BAMAL

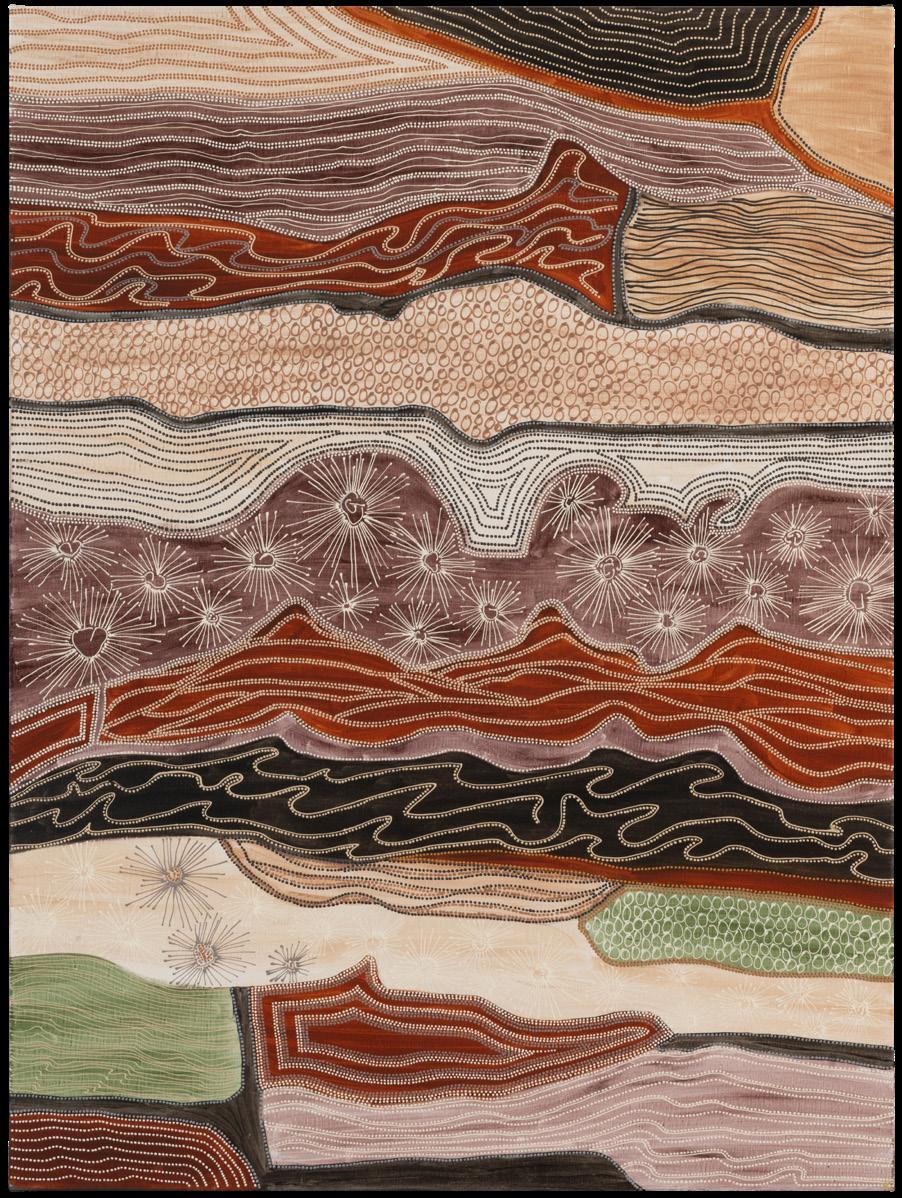

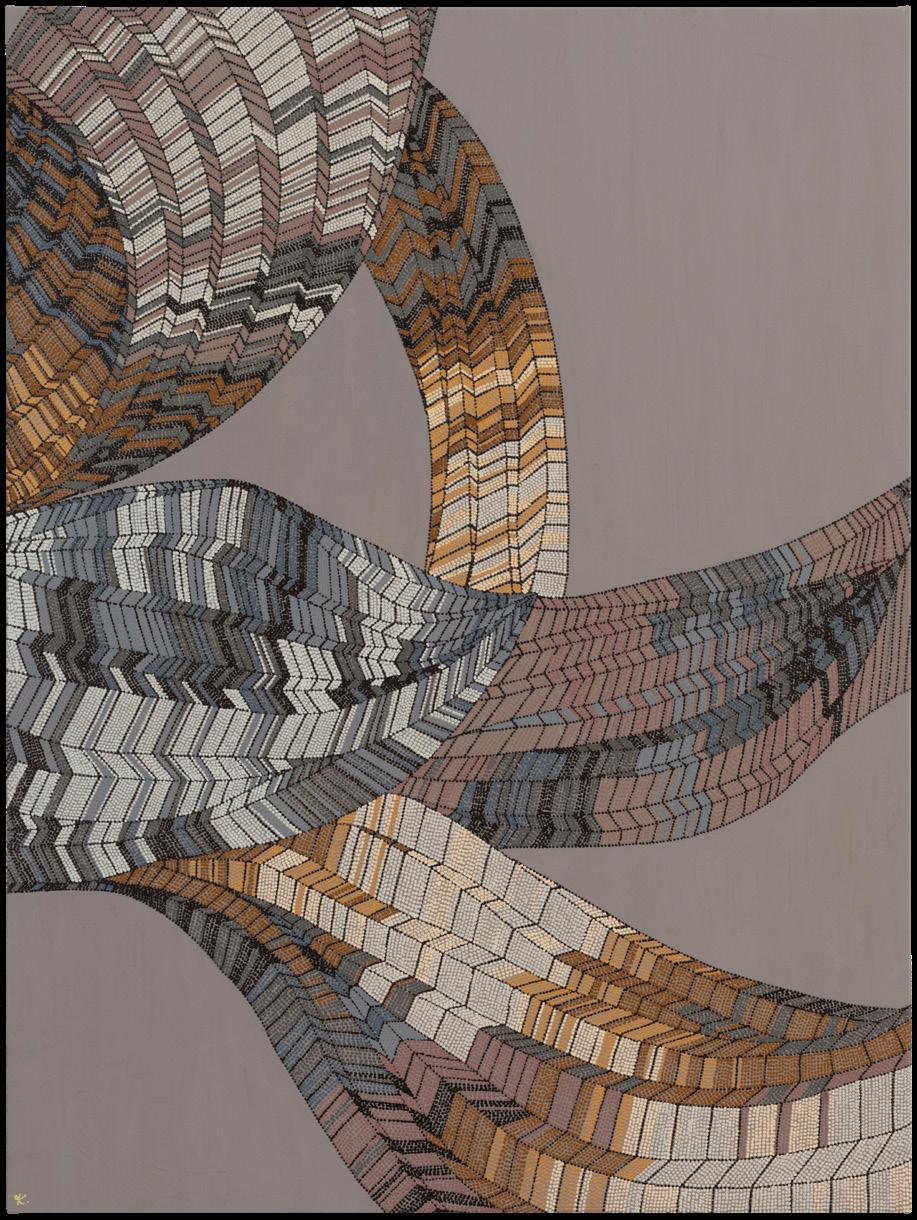

Konstantina, Guwirang I (detail), 2025, acrylic on linen, 139.5cm x 139cm. Image courtesy of Sergey Novoikov.

Konstantina, Bamal II, 2025, acrylic on linen, 121cm x 90.5cm

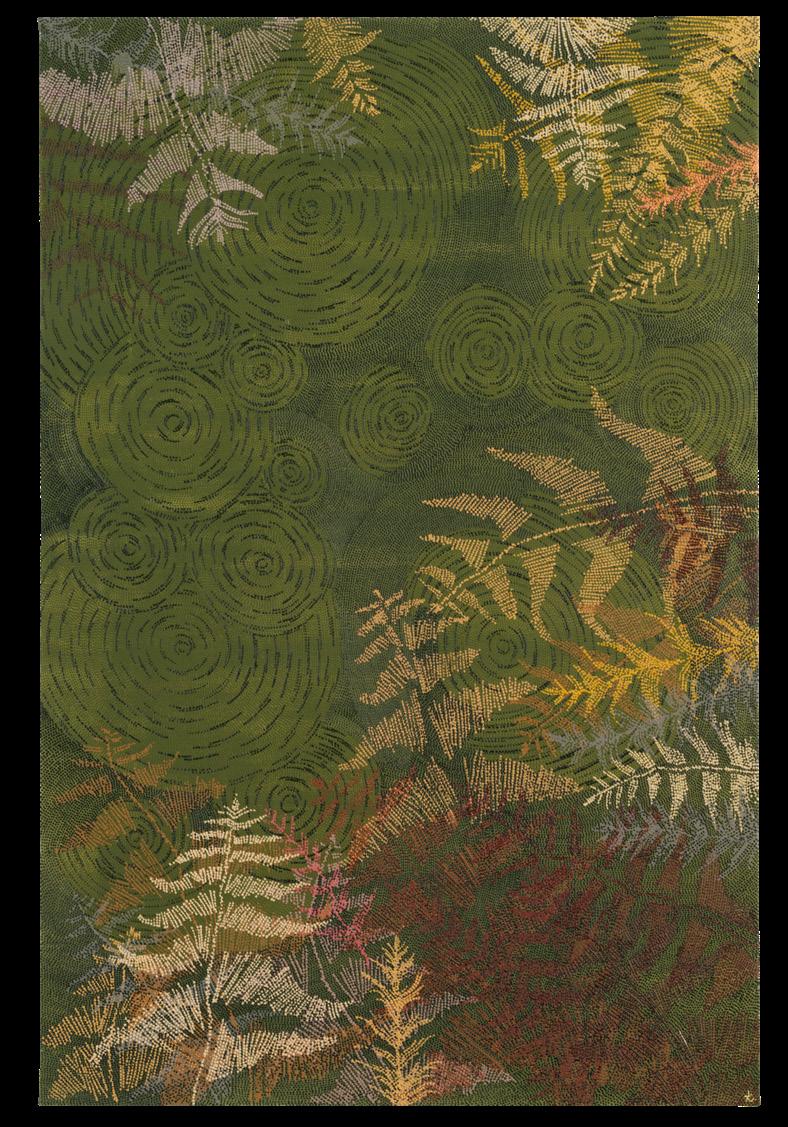

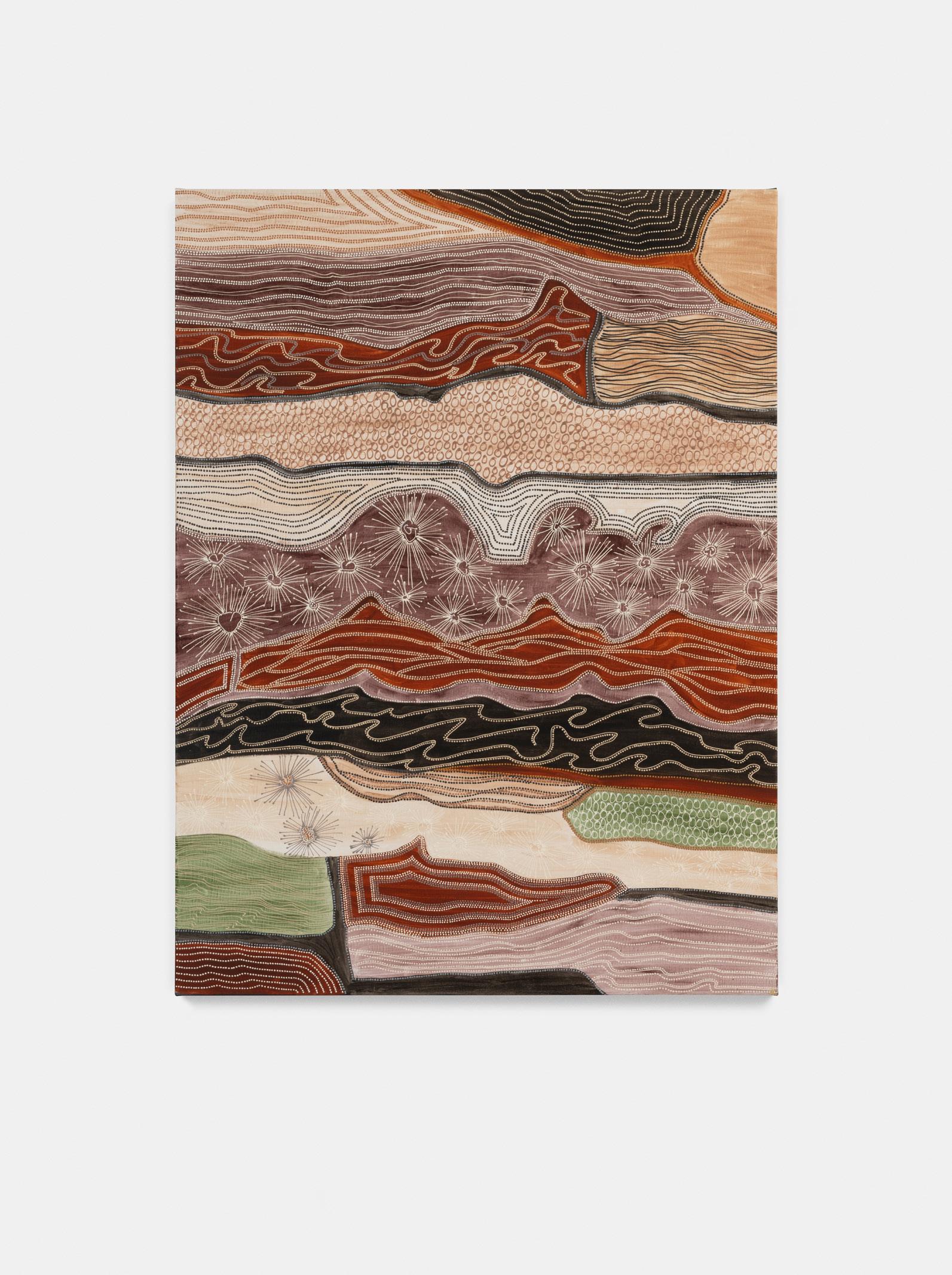

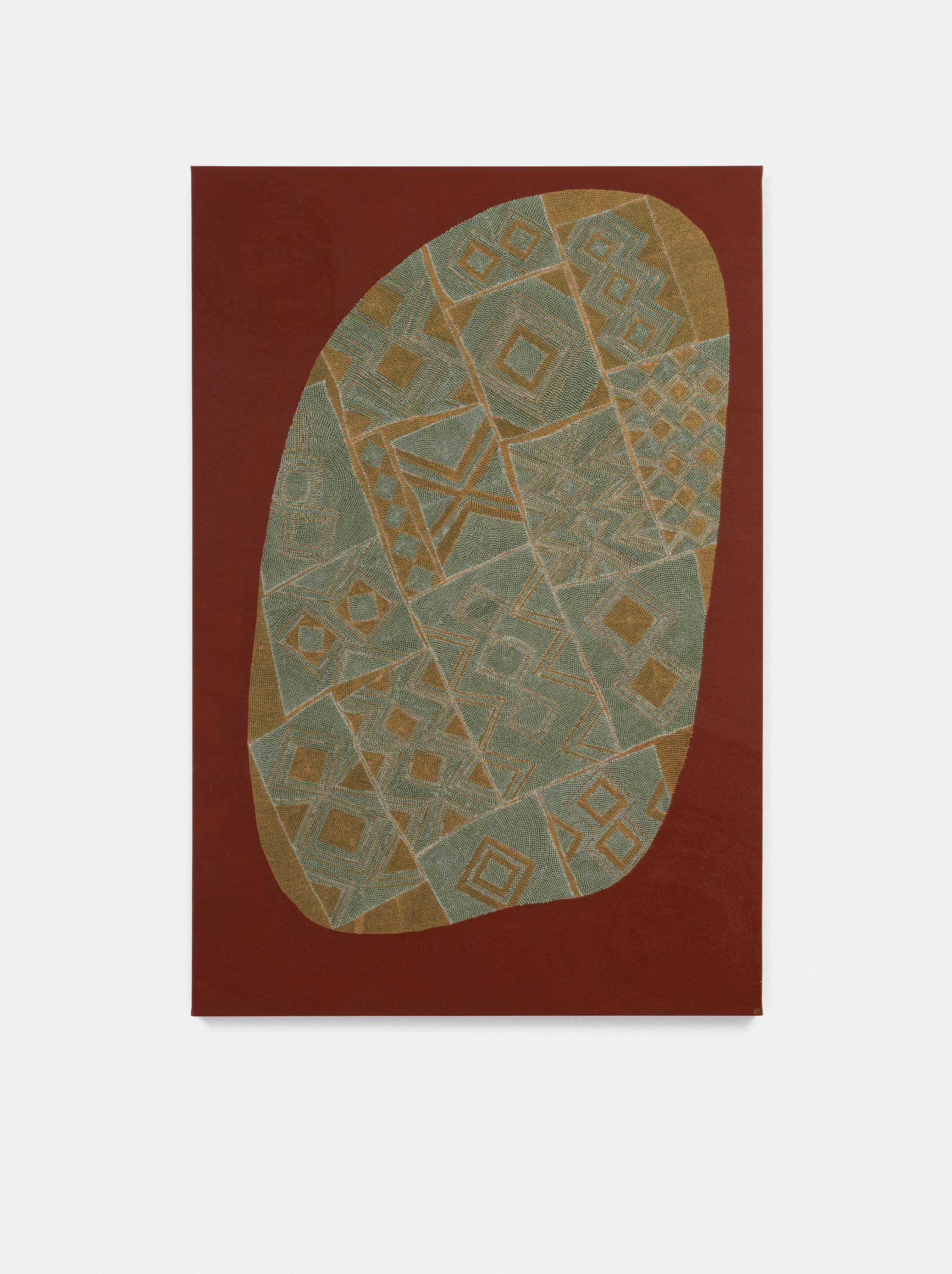

Konstantina, Guwirang I, 2025, acrylic on linen, 139.5cm x 139cm

GUWIRANG

[goh·i ·rung ] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: REED ORNAMENTS STRUNG AROUND THE WAIST OR NECK.

These beautiful pieces are only created to be ornamental, to adorn the body, to increase the beauty of the wearer. They are a painstakingly fiddly treasure to recreate using both Barraba (reed) and Murrira (cordage or line made from bark) and hundreds of sections. It is this practice of slow beauty that has really touched my soul.

Konstantina, Guwirang II, 2025, ochre on linen, 50cm x 50cm

Konstantina, Guwirang III, 2025, ochre on linen, 50cm x 50cm

Konstantina, Guwirang IV, 2025, ochre on linen, 79.5cm x 40cm

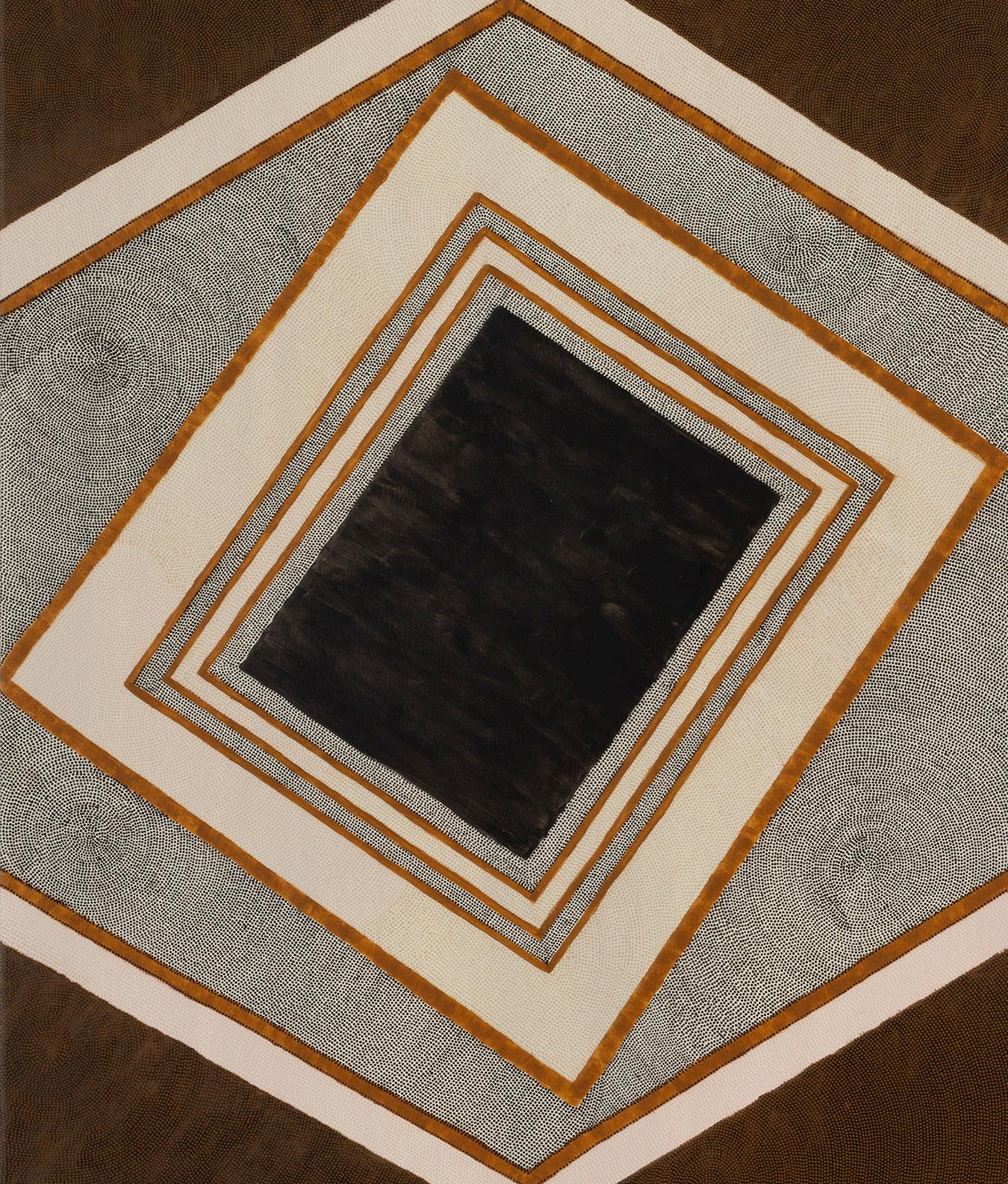

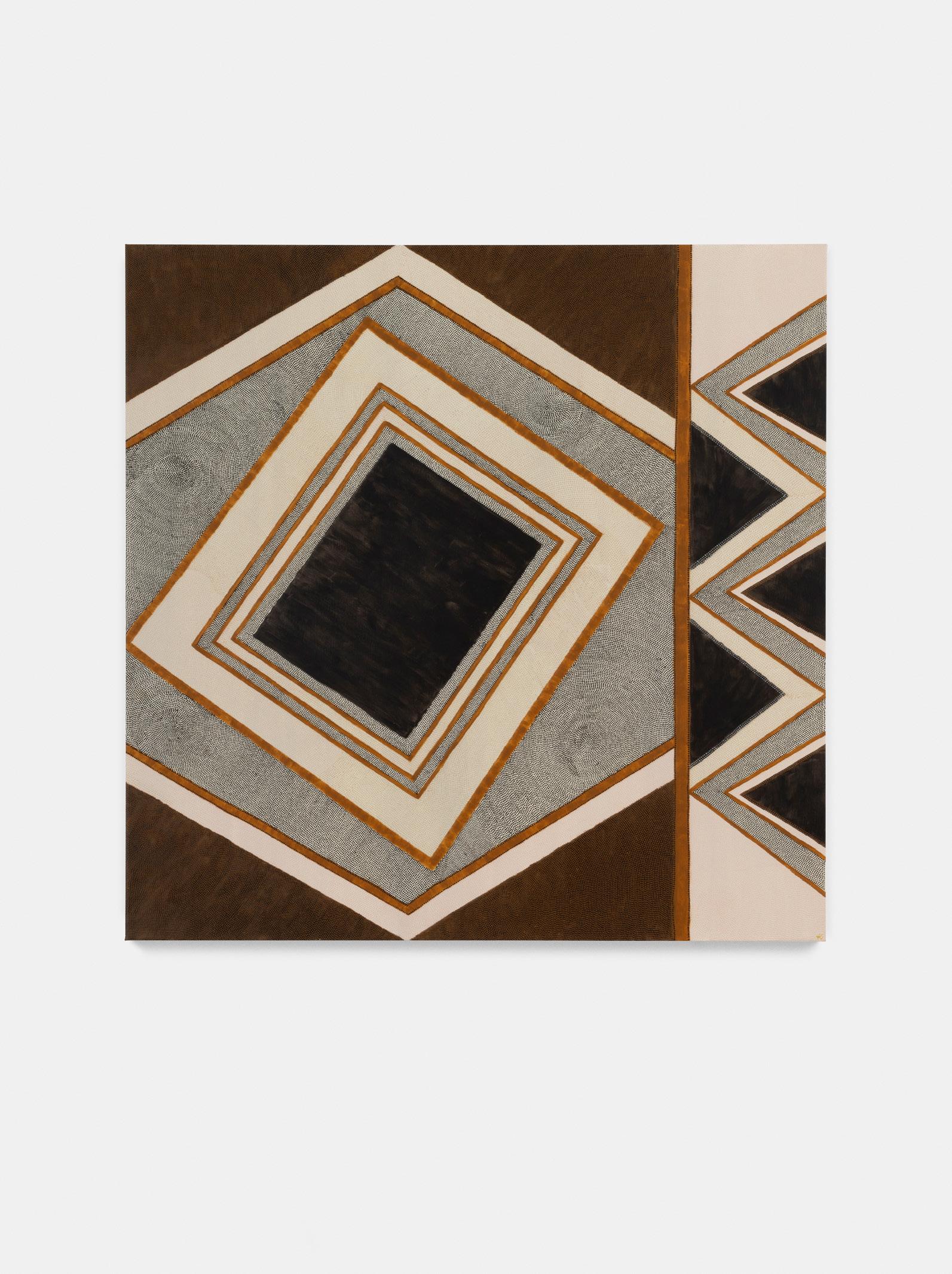

WALI

[wah·li] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: THE GENERIC NAME FOR A POSSUM.

Possums come in many species and sizes, but the generic name for the collective is Wali . Wali skins were used up much of the Eastern coastline to make possum skin cloaks which would be continually added to as one grew physically. These were adorned by burning insignia to the leather side and colouring patterns, which told stories using ochres and natural earth pigments.

Konstantina, Wali, 2025, acrylic on linen, 75.5cm x 75.5cm

BUDBILI

[bood·billy] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: POSSUM RUG OR COAT.

This is a different name to ‘possum’ ( Wali ) as it denotes the actual item which the possum is created into, the possum skin rug or coat. Wali skins were used up much of the eastern coastline to make possum skin cloaks, which would be continually added to as one grew physically. These were adorned by burning insignia to the leather side and colouring patterns, which told stories using ochres and natural earth pigments.

Konstantina, Budbili, 2025, acrylic on linen, 151cm x 100.5cm

Konstantina re-imagining a possum skin panel, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist’s studio.

MARI BUDBILI

[mah·ri bood·billy ] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: BIG POSSUM RUG OR COAT.

This is a different name to ‘possum’ ( Wali ) as it denotes the actual item which the possum iscreated into, the possum skin rug or coat. Wali skins were used up much of the eastern coastline to make possum skin cloaks, which would be continually added to as one grew physically. These were adorned by burning insignia to the leather side and colouring patterns which told stories using ochres and natural earth pigments.

Konstantina, Mari Budbili I, 2025, ochre on linen, 140cm x 139cm

Konstantina, Mari Budbili II, 2025, acrylic on linen, 199cm x 139cm

Konstantina, Murrira I, 2025, acrylic on linen, 151cm x 100.5cm

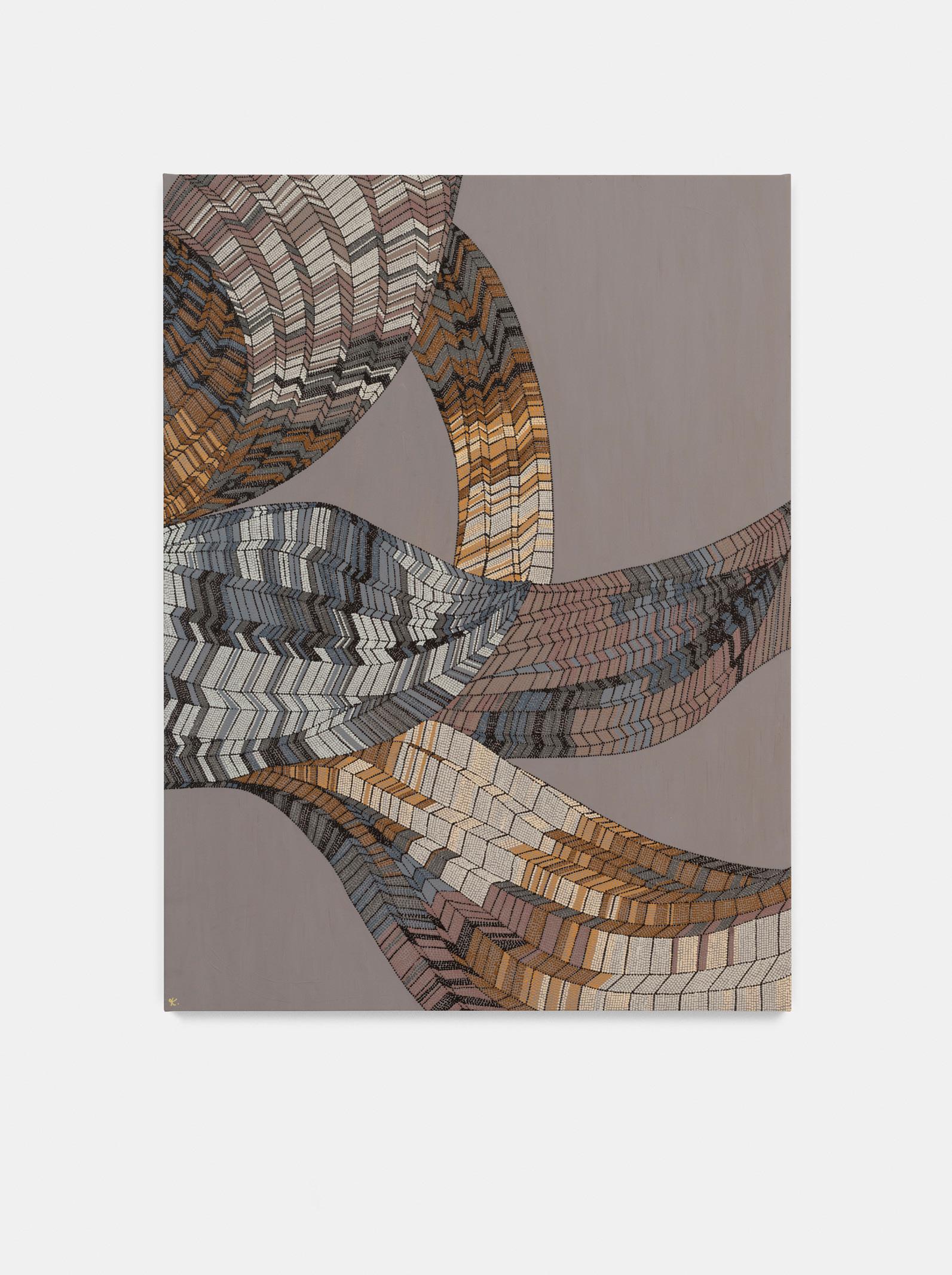

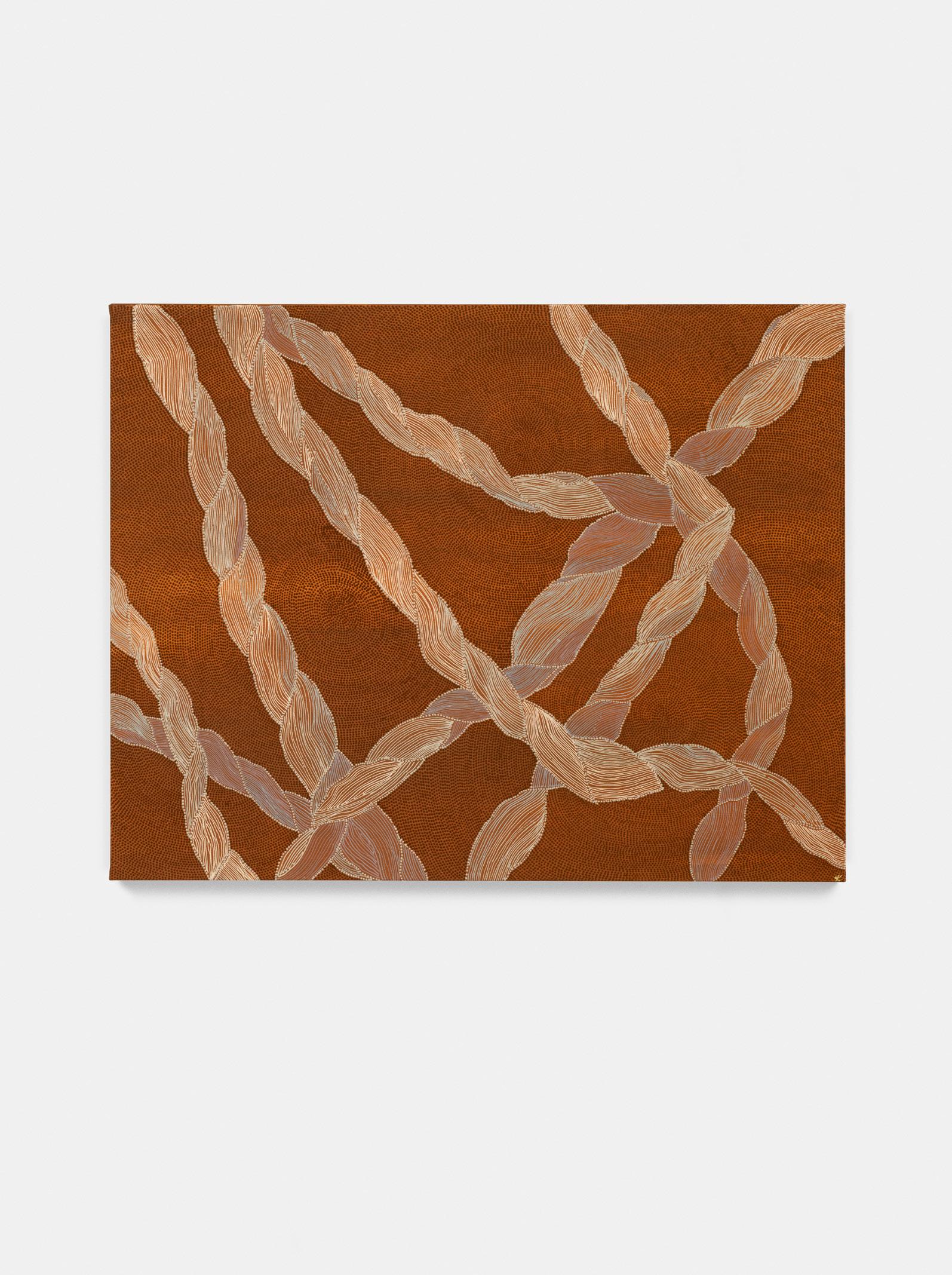

MURRIRA

[mor·ia] n.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: LINE OR CORDED STRING USUALLY MADE FROM NATIVE HIBISCUS OR KURRAJONG BARK.

This work is inspired by the re-making of our original Gadigal practices based on a multi-year project with the British Museum. The artwork is made at the same time as I learn to make the original traditional cord and so contains the ancient practice and wisdom of the Culture of my people. It is a physical annotation, a remembering of this Culture and therefore a conduit to the past from the present.

Konstantina, Murrira II 2025, acrylic on linen, 121cm x 90cm

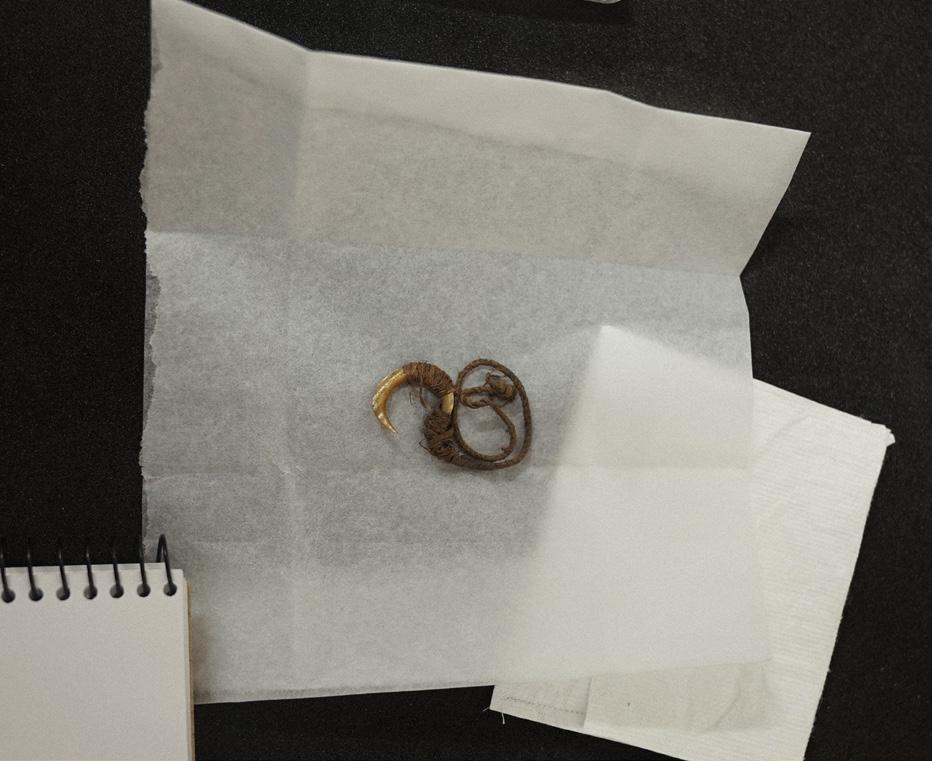

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: THE SHELL USED TO MAKE A FISH HOOK.

The making of Bara (fish hooks) traditionally used the turban shell, a once endemic species to the Sydney Harbour. The shell was heated up, broken and shaped by hand and grinding stone to fashion into a hook that was affixed to a length of hand spun cordage made from tree bark.

BARAGU

[bara·gu] n.

Konstantina, Baragu, 2025, acrylic on linen, 60cm x 60cm

Below: Konstantina carrying

[bun·ga] v.

GADIGAL TRANSLATION: TO MAKE.

In response to the sublime images taken on the Hirox microscope with the British Museum conservation team when viewing the cordage of an original Gadigal fishing hook dated to 1788 in the archival collection.

Konstantina, Banga I, 2025, acrylic on linen, 75cm x 75.5cm

BANGA

Konstantina, Banga II, 2025, acrylic on linen, 79cm x 100cm

Konstantina in her studio, 2024. Image courtesy of Sabine Bannard.

Front cover:

I (detail, darkened), 2025, ochre and acrylic on linen, 75cm x 90.5cm. Image courtesy of Sergey

Back cover: Konstantina mixing paints. Image courtesy of the artist’s studio. Editorial design: Antonia Crichton-Brown. Photography: Shae Constantine, the British Museum, Sabine Bannard and Lisa Jackson Pulver.

Konstantina, Bamal

Novikov.