ABSTRACT

Throughout history, architectural ornamentation has evolved in many ways. The use of what was once, historically, considered ornamentation has transformed into various discreet and indiscreet modern uses. However, this does not limit modern architecture from pertaining aspects of architectural ornaments, nor does it make modern structures duller. Rather, the revival of ornaments in modern architecture has made structures lead more innovative and invigorating directions.

Key Words: ornaments, decoration, modernism, façade

INTRODUCTION

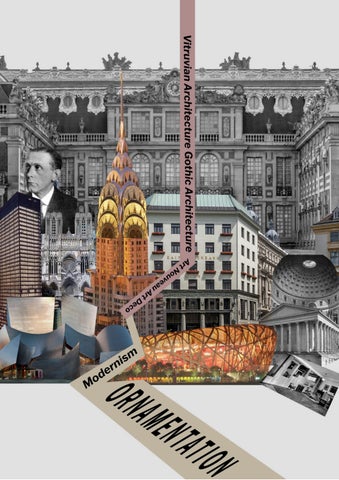

The use of ornaments in historical and modern architecture has been a topic of dispute among various architects and thinkers following the end of the 19th century. The discussion involving ornaments is not one to be categorised as a simple architectural dispute, as it is a conundrum that cannot simply be solved by comparing different scholastic opinions. Notions about ornaments in architecture have ranged from commending them (Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament) (Image 1) to condemning them (Adolf Loos’ Ornament and Crime) (Image 2). For an early 19th century script, Owen Jones’ take on ornamentation was suitable for the era he lived in, where ornamentation was celebrated in all architectural works.

Ornamentation is a waste of labour and material!

Ornaments are vital parts of architecture

However, Adolf Loos’ 1908 essay forms a great part of the discussion, in relation to modern day architecture, where he regards the use of ornaments as an element of old architecture and should be a phase that is outgrown by modern society. He quotes “We have fought our way through to freedom from ornament ” (p 20) Despite strong arguments against the use of ornaments from various architects and thinkers, it is an element that is still prevalent in modern architecture. This dissertation will be categorised into chapters each of which will be looking at an aspect of ornamentation from pre to post 20th century It will explore the use of ornaments by comparing and contrasting old and new arguments on the use of ornamentation. It also aims to explore the modern uses of ornaments in architecture by highlighting the National Stadium (Bird’s Nest) in Beijing, China as the primary case study for modern use of ornaments and contrasting it with ornaments used in historical architecture and how they have evolved. Finally, this essay aims to clarify the dispute over the use of ornaments in architecture by providing the necessary evidence to support both arguments and provide a summary to conclude the presented arguments.

SECTION I: Historical and Post-modern Perspectives on Ornamentation

Before discussing the polemic over ornamentation, it is important to understand a few things first: What are ornaments? Are ornaments and aesthetic the same idea? Are ornaments even crucial to architecture? Firstly, ornament in the English language is, as referred to in Cambridge Dictionary, “an object that is beautiful rather than useful”. It is an adornment, an embellishment, a decoration, and an additive that beautifies the subject that it is used on These definitions then, do illude to the idea that ornaments are aesthetical additions. However, if ornaments are only futile additives, are they crucial elements to architecture?

But, if ornaments are only futile additives, are they then crucial elements to and relevant to architecture?

To respond to this, I would like to use a quote from, Islamic Art specialist, Oleg Grabar’s 1992 book The Mediation of Ornament where he argues that ‘architecture is a true ornament (...). Without it, life loses its quality Architecture makes life complete, but it is neither life nor art ’ (p.193).

However, ornamentation has not always been considered as such, and has been regarded in different manners throughout the centuries As advancements in architecture occurred, trends in ornamentation have changed, with each era having certain characteristics that pertain to it.

Owen Jones (1856) claims that, ornamentation in architecture reflects every era and culture’s identity. Jones’ stance on ornamentation is one that was widely accepted during and before the early 19th century. He argues that, developing a historically devoid ornamental style in order to cater to modern architecture’s needs is not the best solution to create refinement in modern ornamentation

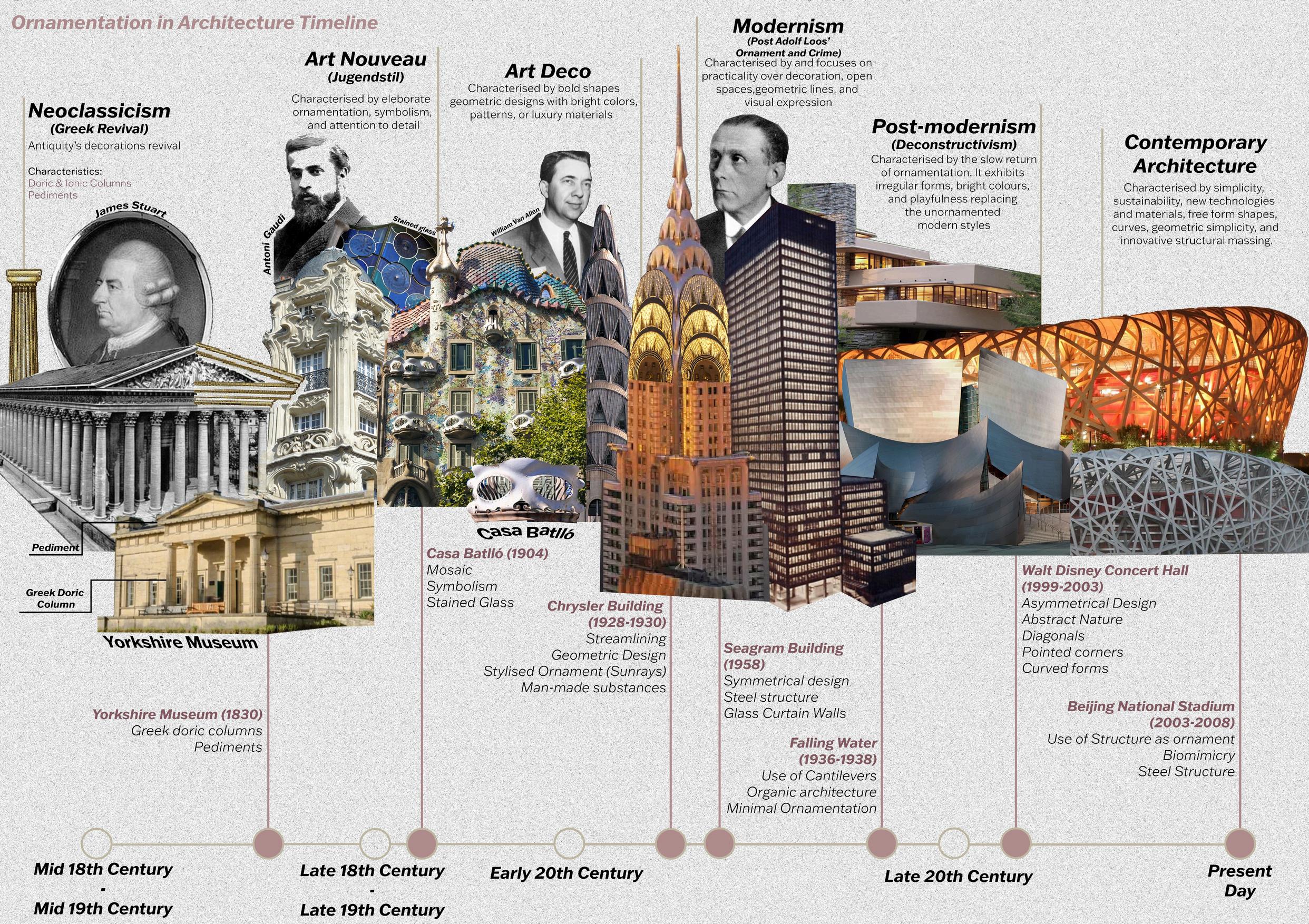

To introduce the several architectural styles, I have created a timeline that categorises each era to its relative characteristics (timeline in page 7).

During the mid-18th to mid-19th century, ornamentation revival was evident as Neo-classicism (Greek Revival) surfaced: one of the main aspects of that era was antiquity’s decorations revival and the prevalence of Doric and Ionic columns and pediments (which were condemned by modernists).

Following this came Art Nouveau which was characterised by elaborate ornamentation, symbolism, and attention to detail, with Antoni Gaudi’s Casa Batlló and Victor Horta’s Hotel Tassel pioneered this architectural style. However, this style, which appeared heavily ornamented to some, was criticised, and mocked as “noodle architecture”.

Art Deco followed shortly after and was one of the starting points for the 20th century architecture, with Claud Beelman’s Eastern Columbia Lofts and William van Allen’s Chrysler Building, both showcasing the architectural style’s main elements: geometric design, patterns, stylised ornaments (in this case sunrays), and luxury materials.

This architectural movement was the closest to the modernist movement, whose one of its main advocates was Adolf Loos. Modernism rejects superfluous ornamentation and rather encourages practicality over decoration, open spaces, geometric lines, and visual expression (Loos, 1908).

One primary example of modernist architecture, though it has been a topic of dispute for its integrity, is Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building

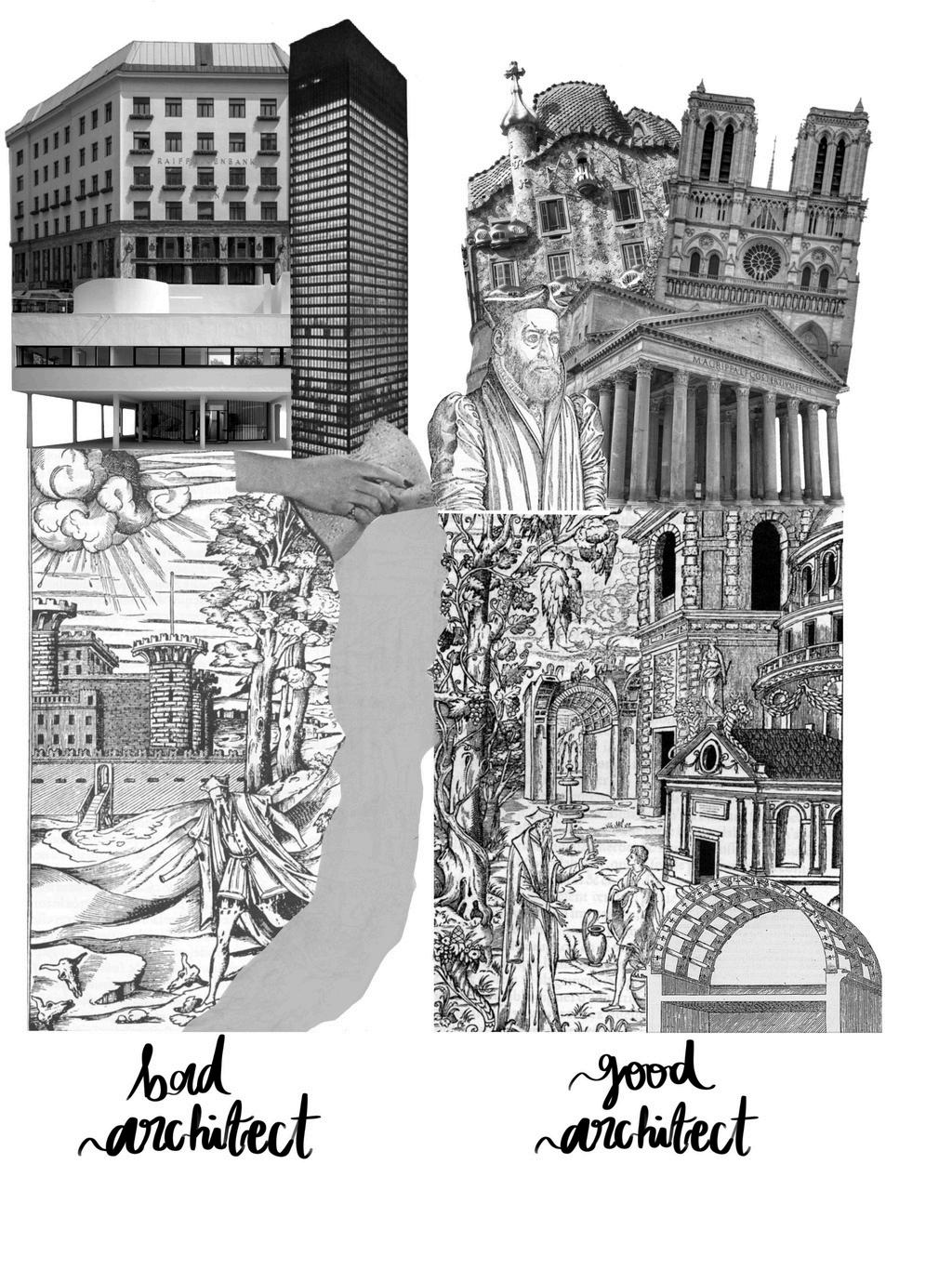

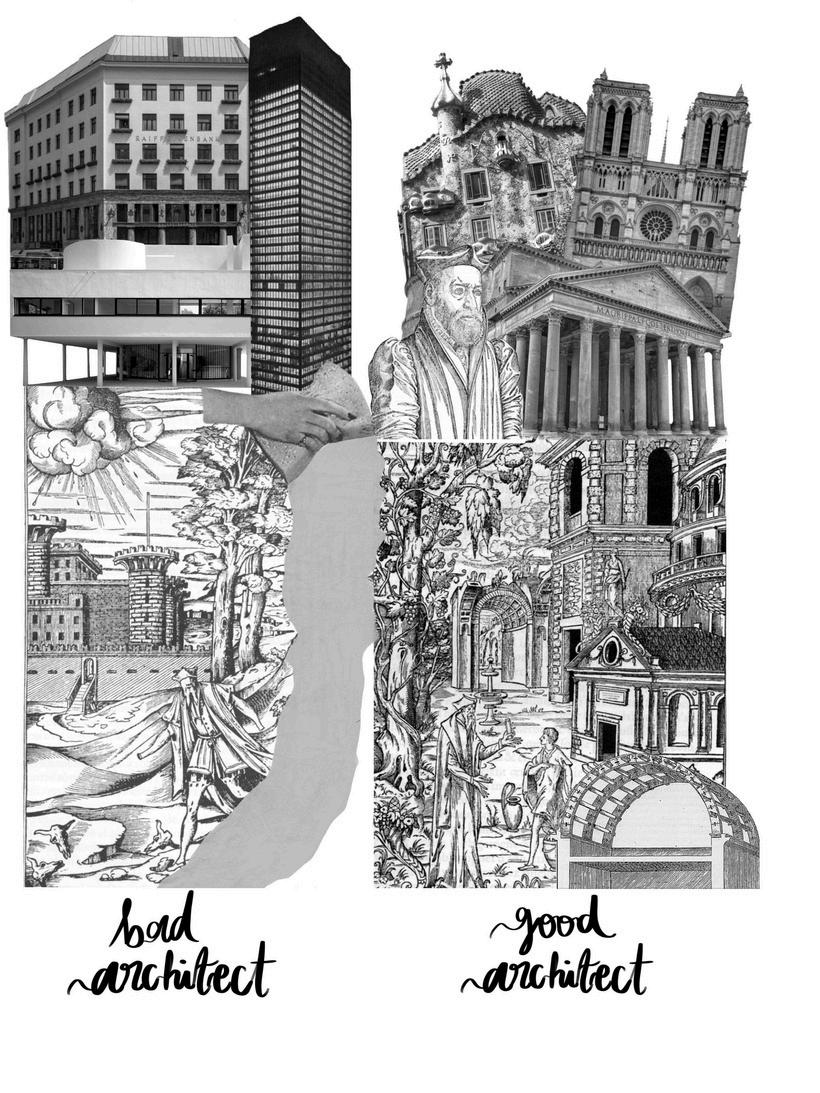

Analysing these architectural eras and their characteristics made me highlight the question of: has ornamentation disappeared from modern architecture? To answer that I first analysed texts that clarify how ornamentation was regarded in the past. A discussion that Antoine Picon (2013) mentions in his book regarding Philibert de L’Orme classification of the ‘bad’ and ‘good’ architect piqued my interest. De L’Orme classifies the “bad architect” as a wanderer in barren landscape surrounded by a medieval, gloomy castle, while the “good architect” is seen relishing the joy of being in a garden surrounded by beautiful, ornamented buildings from all sides. De L’Orme therefore classified the ‘bad architect’ as one that does not use ornaments, while the good architect is enjoying his surroundings as a result of incorporating ornaments in his work. Therefore, until the emergence of modernism, a key indication that sets apart good architects as geniuses to everyone else is the implementation of ornaments in their work (Picon, 2013) This was a key aspect that was carried on from the Vitruvian era, where excessive, arguably unnecessary, ornamentation was used in architecture.

DISCUSSION:

This chapter tried to clarify the different arguments on ornamentation in architecture; however, one cannot argue that a certain argument is the correct answer to the topic. In addition, several architectural styles throughout the centuries have been and still are regarded with awe from people outside of and in the field of architecture

These styles include:

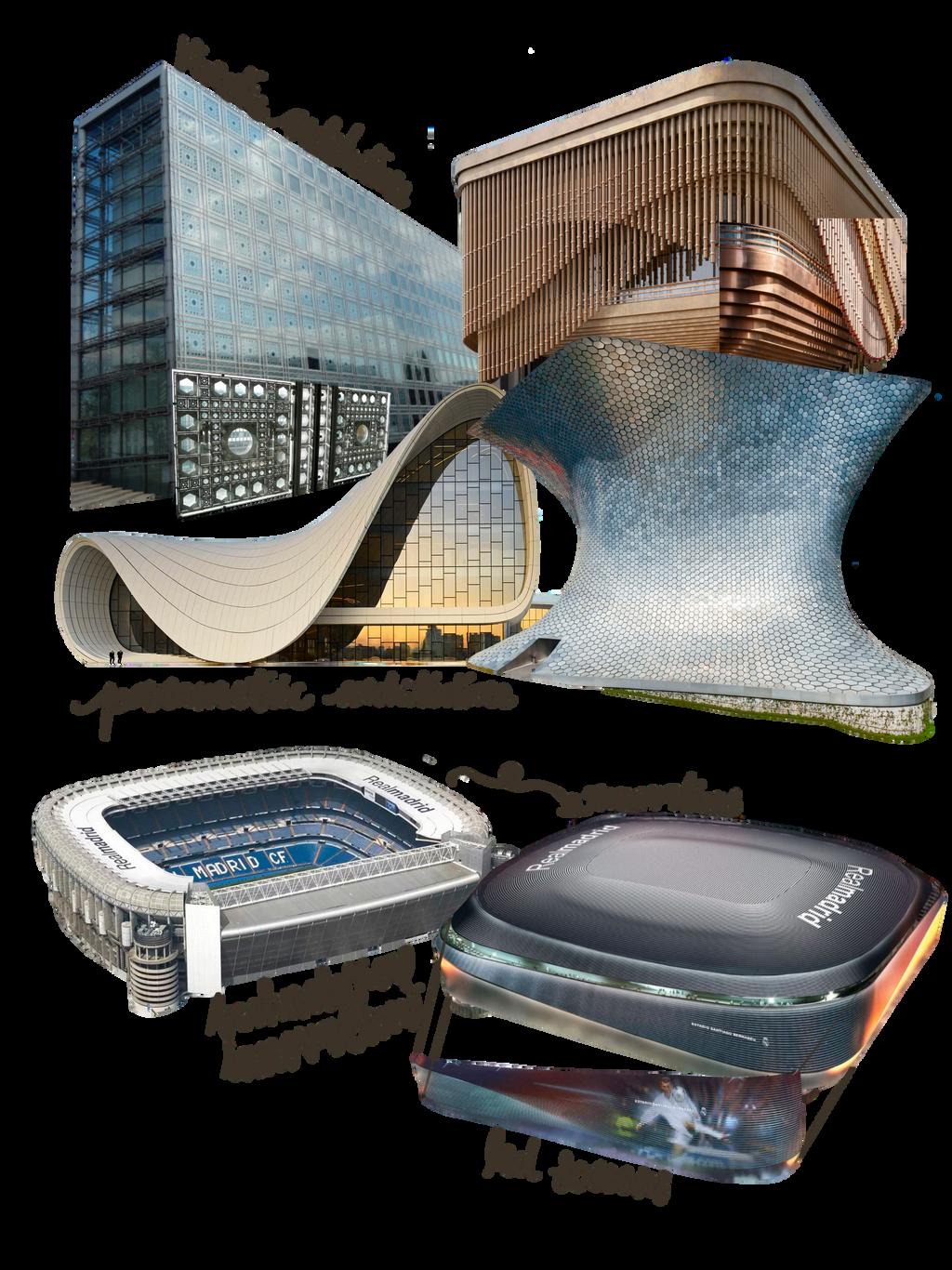

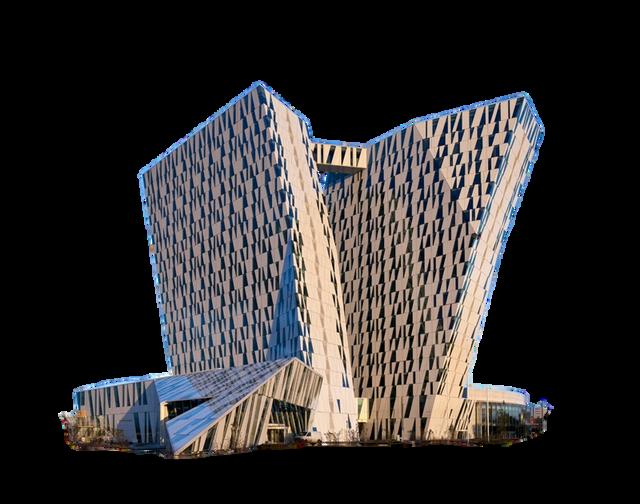

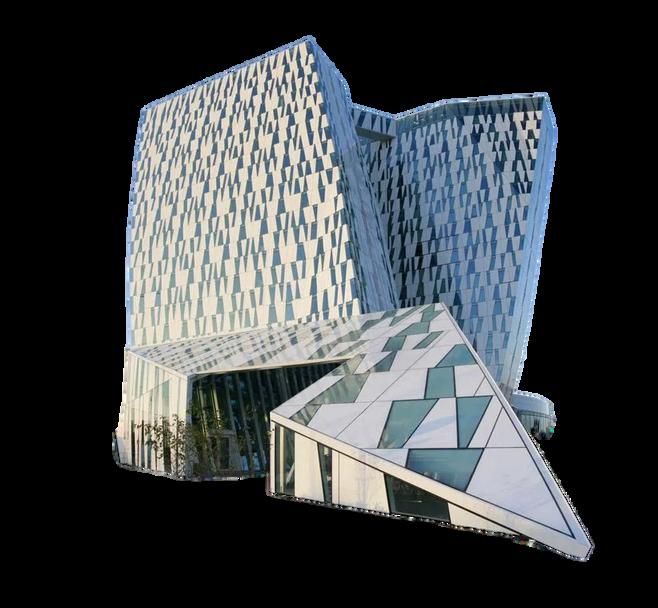

Modern and pre-modern buildings included in this collage depict what would be considered as a work of a ‘bad architect’ and a ‘good architect’ according to Philibert De L’Orme’s argument.

Personally, these architectural styles, are quite impressive due to the structure and the feeling of grandeur these buildings emit. However, to argue that architecture should have continued following the same ornamentation style would be a faulty argument, since the architecture field constantly tries to improve on the mistakes of previous eras by developing newer approaches. Therefore, changing the route followed in relation to ornamentation and developing new techniques and styles does not result into the loss of grandeur, aestheticism, or merit of the building.

SECTION II: Conflicting viewpoints on Ornamentation

Straying away from historical and traditional ornaments has provided innovative ways by which contemporary architecture could enhance and create its own ornamental styles (Pyrtek, n.d.). The modernist movement has aided in such development, where architectonic designs are not the only way one can experiment with and implement ornaments. This realisation was aided by several modernism pioneers, including Adolf Loos, Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and several others. Even though, to some, Loos’ viewpoints could have been very jarring regarding the dismissal of ornamentation, his book Ornament and Crime did not demand the outright elimination of ornaments in modern architecture Loos was rather calling forthe reinterpretation of the way ornaments are used, and regenerating ornaments to suit current modern-age requirements (Miller, 2011). What he dismisses is the typical use of ornaments that focuses on integrating additional elements with the aim of beautifying either for cultural significance or for aesthetic purposes (Loos, 1908).

Post-modernism, instead of viewing ornaments as a futile appliqué, views ornaments as an integrated and functional building elements that have a concrete motif, whether that is correlated with lighting, aperture, enclosure, or even empowerment to the visual vigour of a building (Miller, 2011). This indicates that, for contemporary architecture, as long as it is not an additive which the building could flourishing without, and is justifiable, ornamentation is permitted. As Loos (1908) argues “I don’t accept the objection that ornament heightens a cultivated person’s joy in life, don’t accept the objection contained in the words: ‘But if the ornament is beautiful!’ Ornament does not heighten my joy in life or the joy in life of any cultivated person” (p.21). He also compares ornamentation to gingerbread, and he mentions that he would prefer to have a smooth minimalistic piece rather than a gingerbread symbolising something and is fully covered in ornaments (i.e., icing and sprinkles). He then claims that the man of the fifteenth century would fail to comprehend this, but modern people would be in accordance with him

in support of ornamentation, Owen Jones (1856) argues: “Although ornament is most properly only an accessory to architecture and should never be allowed to usurp the place of structural features, or to overload or to disguise them, it is in all cases the very soul of an architectural monument.” (p.470). This is a stance that modernists would not be fully in accordance with due to the mention of ornament being “the very soul of architectural monument”. It has become clear over time that modernism pushes the idea that ornament is not a vital part of architecture, rather it is a component that, when incorporated in the correct and suitable manners, strengthens architecture.

SECTION III: Present day Use of Ornaments – Case Study

When it comes to modern and post-modern use of ornamentation in architecture, one could wonder about the reason of how and why ornamentation has come this far. Peter Collins proposes a series of questions, in his 1965 book Challenging Ideals in Modern Architecture 1750-1950, where he tries to understand the reasons as to why ornaments have evolved and developed the way they did He argues that there has been persistent demand since midnineteenth century to introduce new architectural styles, techniques, and systems. He also questions this emerging need and demand of ‘new architecture’ by arguing that it could be due to the hope of developing cheaper or newer construction methods, the public’s call for new and original architecture, or due to abstract reasons which are only relevant solely to architects and people in the field of the built environment (Collins, 1965). Ornamentation has developed and continues to do so in ways that utilise the development, resources, and the needs of the current world.

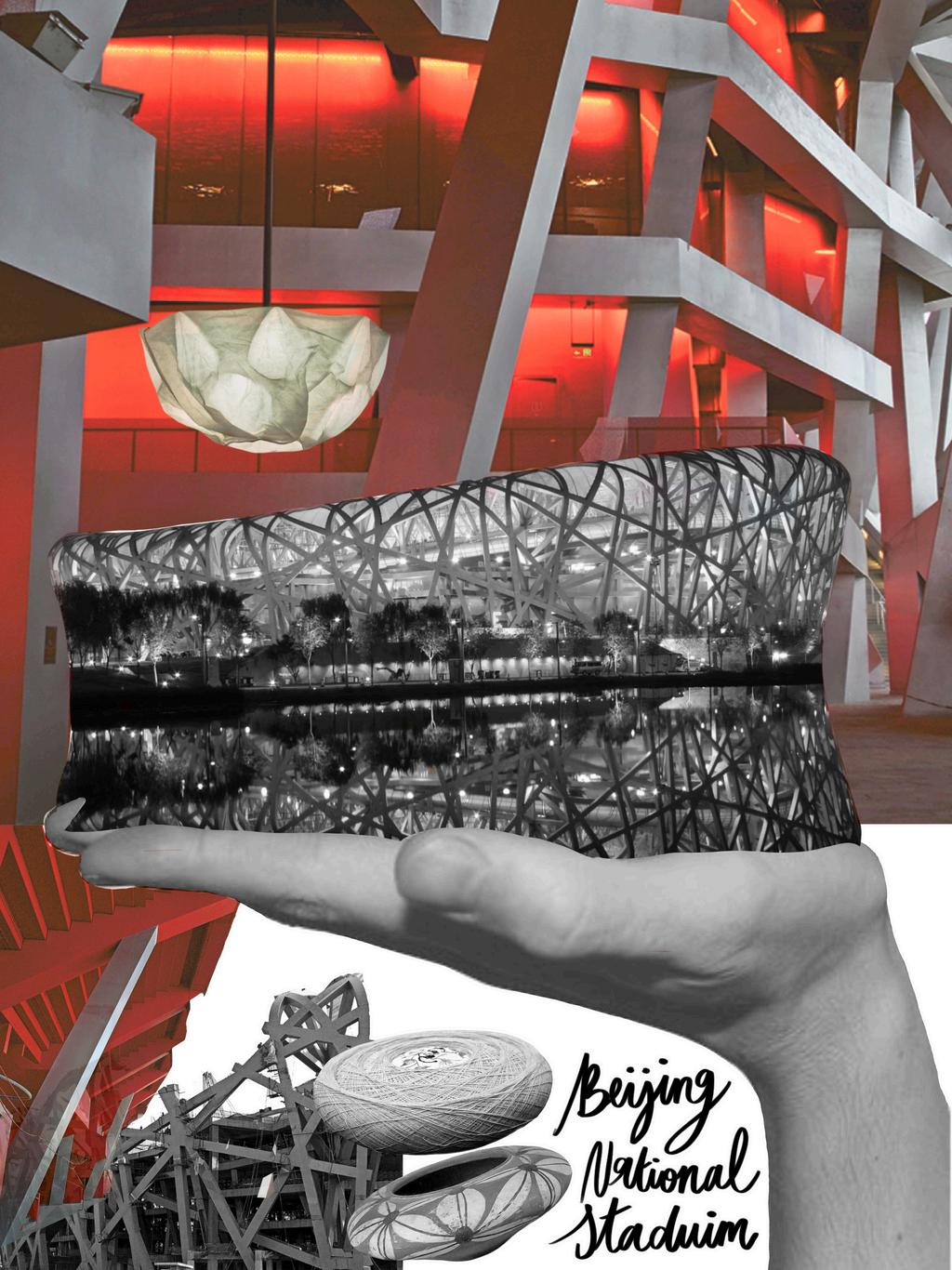

Innovation in ornamentation is derived from the invention of new techniques and producing new ornamentation styles that are different from the traditional ones (Picon, 2013). Innovation in modern and post-modern architectural ornamentation takes place in various forms, including the use of lighting, structure, technology, and geometry One of the main examples of postmodern architecture that utilises both light and structure as ornaments, and defies the postmodern ornamentations’ habitual patterns, is the National Olympic Stadium (renowned as the Bird’s Nest) in Beijing, China. The infamous Olympic stadium, completed in 2008, built by architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, had a main objective: there shall be no distinction between the ornamental and structural aspects of the arena, since its main aim is to transcend this one-dimensional classification.

Ornamental Elements:

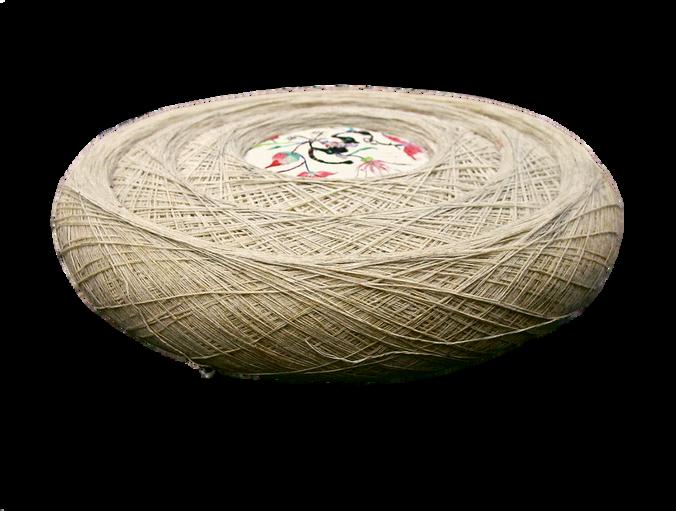

The form of the stadium follows several traditional Chinese cultural elements as well as mimicking the form of a round bowl

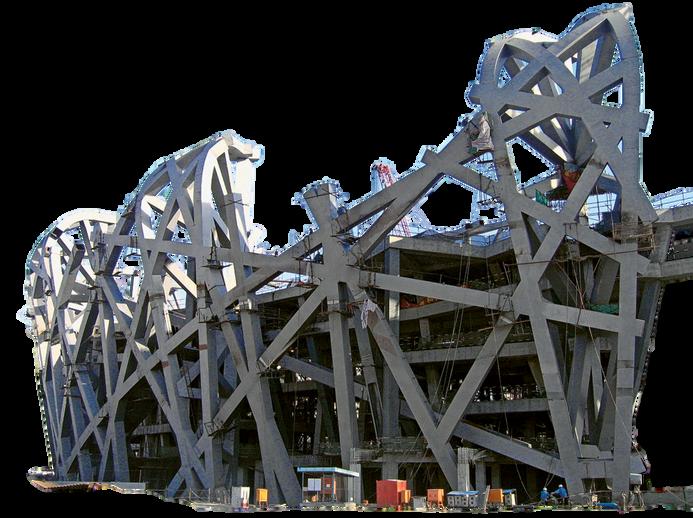

Its structure also plays an important role in the uniqueness of the building, where the roof’s structural support system, composed of diagonal and vertical braces and a mesh of columns, creates an architectural statement (H&dM, n.d.). Trussed columns, a mixture of computerbased and analogue techniques, and prefabricated steel columns are all factors that contribute to the form of the building, serving as modern forms of ornamentation.

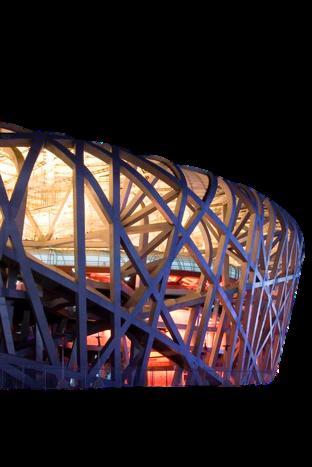

The interior of the stadium contains red steel frames, which contribute to the red hue that is projected on the exterior when the interior of the stadium is illuminated.

Red is also a symbolic colour for Chinese culture, which is an addition to the considerations taken while constructing the stadium, in relation to culture and tradition

Another element that contributes to the ornamentation included in the stadium is the individual lamps adorning both the exterior and interior of the building, providing unique light patterns during the night.

The Beijing National Stadium is one of the primary examples of modern-day use of ornamentation due to all the aforementioned characteristics. To modernists, such use of ornamentation could arguably be accepted, since the ornamentation included is, simply, of use For example, the reason why the stadium does not follow the typical stadiums’ enclosed façade is to enable the space to experience natural ventilation (H&dM, n.d.). The structure also allows both the exterior and interior to flow together, creating an inviting atmosphere. This brings us back to the point that, modernism does not essentially reject the use of ornamentation, rather it rejects or accepts the reasoning and functionality behind them. Even though the stadium could have just been built in a typical manner like other stadiums, it follows a unique structure, uses biomimicry and is adorned by colourful lighting.

The Bejing National Stadium, along with numerous modern and post-modern structures exhibit the revival of ornamentation taking place since the mid-20th century until the present day. Décor and adornment remain elements that enable us to view essential architectural elements in unique ways (Picon, 2013) However, to modernists, only a certain level of personal expression is allowed while integrating ornamentation in architecture, which results in a discord between what is deemed as futile and what is essential. Despite that, post-modernist architecture continues to find the balance between integrating ornamentation in manners that are not detrimental to the honesty and quality of the buildings. Therefore, ornamentation could not be as ‘criminal’ as early 20th century architects deemed it to be In addition, the evolution of adornments and décor continues as technological advancements now play a vital role in the construction and designing of buildings.

InteriorLighting ConstructionPhase

DISCUSSION:

Ornamentation has developed in different ways according to the needs of each architectural era, where ornaments, in modern architecture, are used in ways that maximise the use of the building and are not futile additions to buildings that, as Loos argues, would be a loss of labour and material (Loos, 1908)

SECTION IV: Current and Future Trends in Ornamentation

The ability of ornamentation to integrate aestheticism, power, hierarchy, and prestige creates a medium for self-defining one’s work In modern and post-modern architecture, pattern, particularly, emerges as a means of innovation in architectural ornamentation (Necipoğlu & Payne, 2016).

Innovative Methods of Ornamentation Include:

two-way folding sun-shading panels

Technological Advancements

Ornamentation in architecture is a discussion that would differ depending on the era it is being used in. Thus, when determining what is appropriate and what is not in regard to the use of ornaments, it would be biased to argue that certain eras could have dealt with ornaments differently. This is due to the certain styles and necessities of each era, and according to that is the basis on what form of ornamentation is appropriate. In the post-modern era of architecture, we experience a shift in traditional ornamentation and are gravitating towards innovative techniques. For example, artificial intelligence, nowadays, is one of the means that aid and enable designing with expressiveness that transcends the historical approach towards ornamentation (Shaw, 2024).

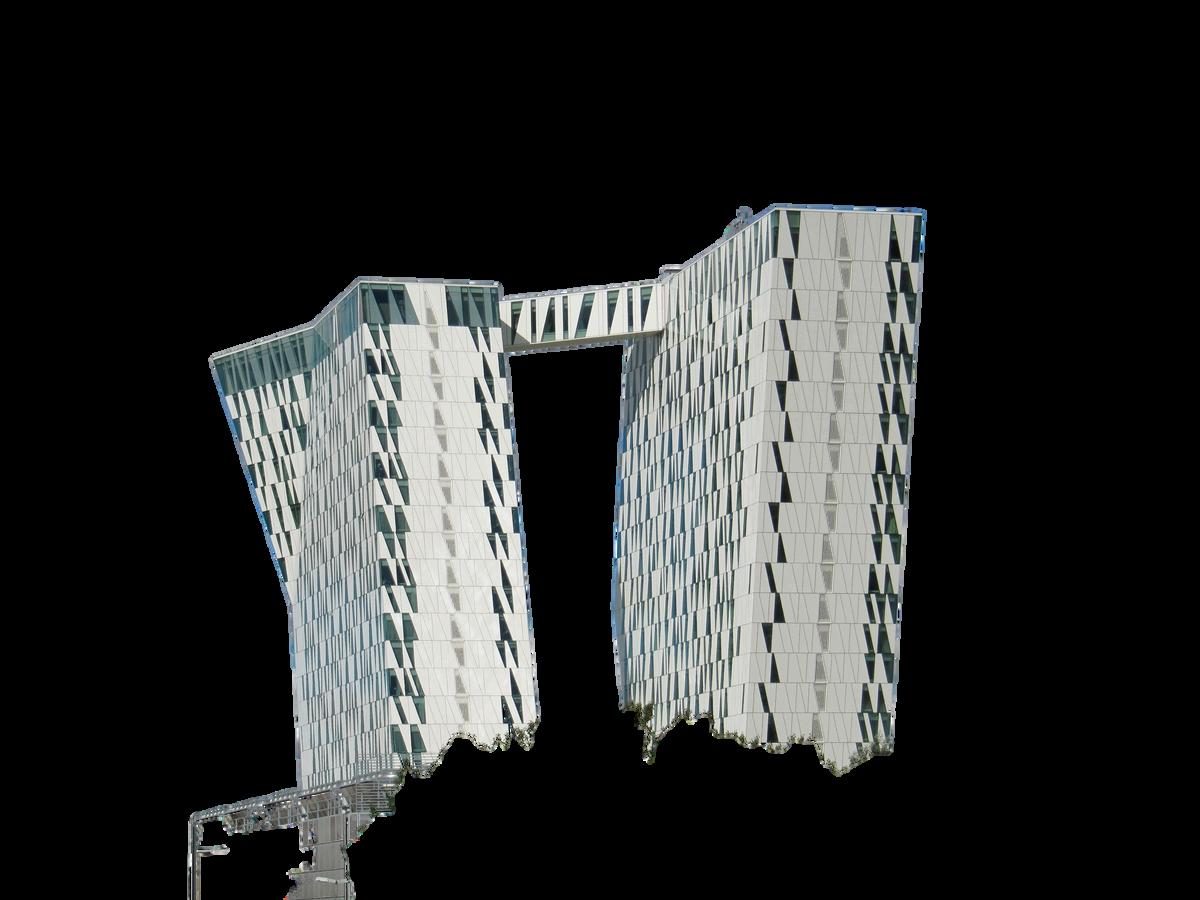

Technological advancements and renovation also shape post-modern architecture. The incorporation of technology in building is an attempt to find the balance between aesthetic and building composition in modern architecture, by integrating contemporary ornaments (Pyrtek, n.d.). A more recent example of a technologically-based renovation is the Santiago Bernabéu stadium in Madrid, Spain.

The stadium’s new appearance imitates a ‘sparkling jewel’ with LED lights illuminating the façade at night, and in the future, video displays of the football matches will adorn the façade, providing passers-by with a preview of the internal content of the stadium.

Parametric designing also contributes to the rapidly developing methods of ornamentation In the case of parametricism, it could be argued that it depends on aesthetic more than ornamentation; however, aesthetic does play a crucial role in ornamentation, and parametric designs are arguably extensively ornaments on the ground.

Such renovation has utilised several ornamentation, and technological orn coordinated stadium. This example fu pp g , y g set of ornamentation styles that works only for its designated time Forcing architecture to follow a certain style will only result in failure of utilising ornamentation efficiently and would prove modernists’ views to be true: ornamentation is futile and should be outgrown by society. However, such use of ornamentation would possibly not be rejected by modernists, since it is not futile and thoughtless; rather, modern and post-modern ornamentation maximise the use of elements that would contribute to a cohesive and functional structure

CONCLUSION

FINDINGS, IMPLICATIONS, & FUTURE RESEARCH

CONCLUSION

The significance of ornamentation in architecture has been a dilemma that transcends generations of architects, thinkers, and designers, with no one argument conclusive enough to put an end to such dispute. When it comes to post-modernity, it is more of an architectural theory stemming from the idea that everything is finite. Every idea, every era, and every concept has an end, an expiry date. When architectural designs, ornaments, or ideas come to an end it signifies that there is development occurring in the field, in this case modernism, which opens an opportunity for improvements and functionality to take over (Borch, 2014). Ornamentation, essentially, is not entirely ineffective, but the way it is used is what determines so. As a society, we have moved on from historical-style ornaments and diverted to use more innovative, functional, and essential décors. Ornamentation in modern architecture mainly follows this concept: if without it the building does not lose any of it is structure, function, or essence then it shall not be included However, even if it is a purely aesthetic addition to buildings, as long as it contributes something to the building, whether it is in a stylistic, technical, or functional manner, it is deemed as an acceptable form of ornamentation.

This dissertation has attempted to clarify all arguments regarding ornamentation; however, it is difficult to firmly conclude how ornamentation will progress since it is an everchanging subject that is dependent on the characteristic of each era. However, ornaments have always occupied and still occupy an essential position in the identity and composition of architecture in pre-modern, modern, and post-modern architecture

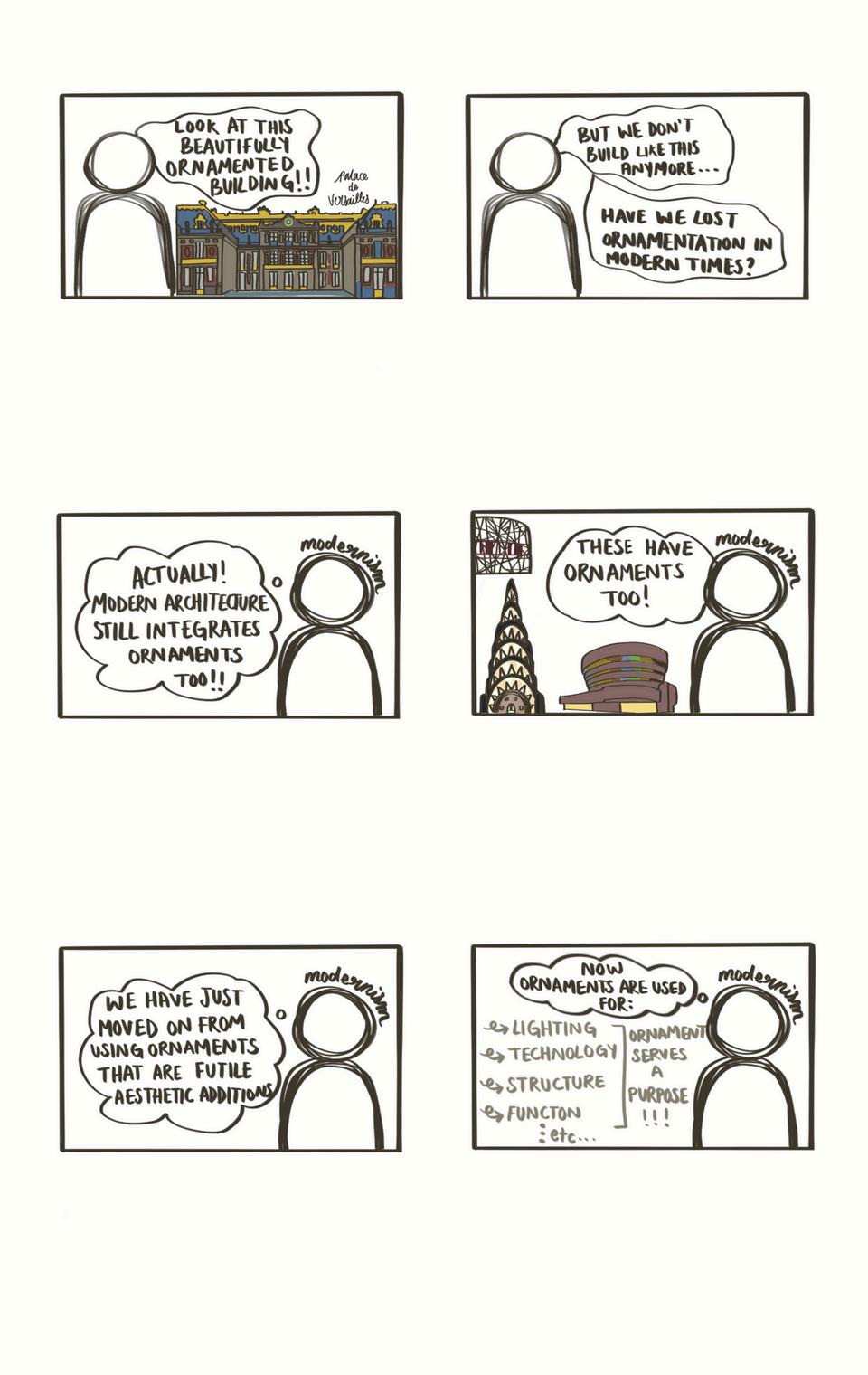

COMIC

REFERENCE LIST

226 National Stadium. (n.d.). Herzog & de Meuron. https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/projects/226-national-stadium/

Borch, C. (2014). Architectural atmospheres: On the experience and politics of architecture. Birkhäuser.

Cambridge University Press. (n.d.). Ornament. In Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus. Retrieved 3 December, 2024, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/ornament

Collins, P. (1998). Changing ideals in modern architecture 1750-1950 (2nd Edition, pp. 128 - 146). Mcgill-Queen’s University Press. (Original work published 1965)

Grabar, O. (1992). The Mediation of Ornament. (pp. 155 – 194). Princeton University Press.

Jones, O. (1856). The Grammar of ornament. (pp. 469 – 476). Day and Son.

Loos, A. (1908). Ornament and crime. (pp.19 - 24). Penguin Modern Classics.

Miller, K. M. (2011). Organized crime: The role of ornament in contemporary architecture. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA). 67-73. https://doi.org/10.52842/conf.acadia.2011.x.n3s

Necipoğlu, G., & Payne, A. (2016). Histories of ornaments: from global to local (pp. 1 - 6). Princeton University Press.

Picon, A. (2013). Ornament: the politics of architecture and subjectivity (pp. 9 - 72). Wiley.

Pyrtek, P. (n.d.). The House façade in the urban space on the example of Berlin. 35 - 42. https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/25598/file/suwFiles/PyrtekP HouseFacade.pdf

Roche, D. J. (2024). Real Madrid CF’s Bernabéu Stadium renovation by gmp, L35 Arquitectos, and Ribas & Ribas Arquitectos finishes in Spain. The Architect’s Newspaper. https://www.archpaper.com/2024/06/real-madrid-cf-bernabeu-stadium-renovation-gmp-l35-arquitectos-ribas-ribas-arquitectos/

Shaw, A. (2024). Techno Deco: AI and the revival of ornamentation in architecture. Building Design. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/techno-deco-ai-andthe-revival-of-ornamentation-in-architecture/5130141.article

IMAGES SOURCE LIST

Image 1: Jones, O. (1856). The Grammar of Ornament [Book]. In Day and Son.

Image 2: Loos, A. (1908). Ornament and Crime [Book]. In Penguin Modern Classics.

Image 3: Uoaei1. (2018). Pipe organ at Wilhering Abbey Church [Photograph]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74973005

Image 4: Princeton University Press. (n.d.). The San Matteo crypt in the 1085 Salerno Cathedral by Italian architect Domenico Fontana in Salerno, Italy. In The Architect’s Newspaper. Retrieved 2016, from https://www.archpaper.com/2016/12/histories-of-ornament-princeton-press/

Image 5: Stafford, S. (2007). Jefferson Memorial, front exterior - stock photo [Photo]. In Getty Images. https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/photo/washington-dcjefferson-memorial-front-exterior-royalty-free-image/200493349-001

Image 6: Diana. (2019). [Photo]. In Diana De Lorenzi. https://dianadelorenzi.com/casa-batllo-all-you-need-to-know-about-antoni-gaudis-masterpiece/?lang=en

Image 7: Gauthier, Y. (2014). Immeuble (1905), Architecte Alfred Wagon - 24 place Etienne-Pernet, Paris XVe [Photograph]. In Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/51366740@N07/15202378700

Image 8: Silvia. (2021). The Pantheon [Photograph]. In Linvisible. https://linvisibile.com/news/exploring-classical-architecture-materials-shapes-significance/

Image 9: Descouens. (2017). Basilique Saint-Sernin de Toulouse [Photograph]. In Wikimedia. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7f/Basilique Saint-Sernin de Toulouse - exposition ouest-1-.jpg

Image 10: Ahmed, J. (2024) Westminster Abbey. [Photograph]. Personal Photograph.

Image 11: Ahmed, J. (2024) Westminster Palace and Big Ben. [Photograph]. Personal Photograph.

Images on Pages 10 - 12: H&dM. (n.d.). 226 National Stadium [Image]. In Herzondemeuron.com. https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/projects/226-national-stadium

Image 12: Gamo, R. (n.d.). Soumaya Museum [Photograph]. In Archdaily. https://www.archdaily.com/452226/museo-soumaya-fr-ee-fernando-romeroenterprise/529542d3e8e44ead2a000016-museo-soumaya-fr-ee-fernando-romero-enterprise-photo

Image 13: Hufton & Crown. (n.d.). Heydar Aliyev Center [Image]. In Archello. https://archello.com/story/22050/attachments/photos-videos/1

Image 14: Mørk, A. (2017). Harbin Opera House [Photograph]. In Area. https://www.area-arch.it/en/harbin-opera-house/

Image 15: Phang, J. (2023). Old Santiago Bernabéu [Image]. In James Phang Blog. https://www.jamesphang.co.uk/blog/2023/9/8/real-madrid-revamp-santiagobernabeu-stadium

Image 16: Real Madrid. (2018). Santiago Bernabéu [Image]. In Real Madrid FC. https://www.realmadrid.com/en-US/news/football/first-team/special-features/thesantiago-bernabeu-of-the-21st-century