LOVE LETTERS TO THE EARTH GENDER INCLUSIVE EQUIPMENT FROM HEALTHCARE TO HUMAN FACTORS

LOVE LETTERS TO THE EARTH GENDER INCLUSIVE EQUIPMENT FROM HEALTHCARE TO HUMAN FACTORS

Welcome to the inaugural issue of SIDEBAR, a multidisciplinary magazine dedicated to breaking down the design silos we commonly find ourselves in. The diversity of budding expertise that brings this magazine to life reflects the collective interests, criticism, and design ethos taking shape across the University of Minnesota’s College of Design. Together, we’ll dive into a range of perspectives, from processing ecological grief as a community and learning how the flight patterns of pelicans can inform leadership policy to exposing the ethical shortcomings in graphic design and sharing tips on how design students can foster a creative workflow.

For every aspiring designer who wishes there was a little more wiggle room in the curriculum to dabble in other design disciplines, you’re not alone. Though the sentiment is as old as the Bauhaus, the demand for multidisciplinary collaboration and learning as a cornerstone of design education has never been more relevant. Designers wear many hats in practice, often acting as both specialist and generalist, researcher and storyteller, problem solver and rule breaker. It’s only natural that our curriculum and tools for design change with the benchmarks of sustainability and call for collective action. Whether you’re an architecture student interested in regenerative design, a product designer investigating circularity, or an apparel designer experimenting with virtual reality, we can all feel the tectonic shift within our industry, challenging the canon of good design. Driving this movement is an interdisciplinary search for synergies between ethics, scalability, aesthetics, and environmental impact.

Thanks to the cross-disciplinary activities hosted by the Kusske Design Initiative (KDI), design students from across the College of Design now have the opportunity to share ideas and investigate design strategies as a collective. Multidisciplinary workshops centered on biomimicry and material life cycles offer design students the chance to work alongside people outside their program. Biweekly discussions make space for informal dialogue between students, faculty, and guest speakers. This magazine is a direct result of these activities, laying the groundwork for students from different design programs to collaborate in ways we never have before.

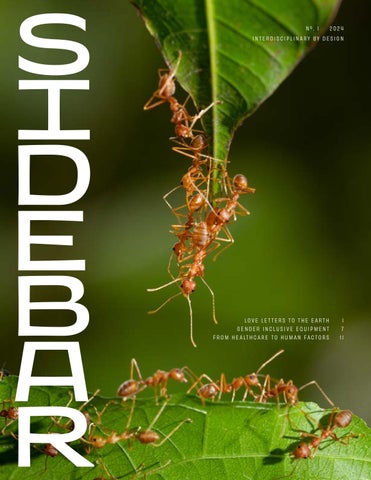

In the spirit of biomimicry, the theme of this past year’s KDI activities, we look to the ingenuity of ants as the honorary cover of this groundbreaking issue. Ants, with their intricate social structures and remarkable teamwork, offer a profound lesson in collaboration. They epitomize the idea that by working together harmoniously, even the smallest individuals can accomplish extraordinary feats.

Jacob DommerExecutive Editor

Production Team

Joseph Hillenbrand

Audra Sims

A Social Art Practice in Dissolving Ideas of Separateness

GENDER INCLUSIVE EQUIPMENT

Made for Watering the Bushes WINGS OF CHANGE

Writers

Jacob Dommer Architecture

Nicolas Donoso

Product Design

Torey Erin

Landscape Architecture

Christine Flauta

Landscape Architecture

Joseph Hillenbrand

Graphic Design

Tse-Hsun Kuo

Human Factors and Ergonomics

Vanessa Segura Duque

Human Factors and Ergonomics

Milo Tacheny

Product Design

Yiling Zhang

Apparel Studies

Special thanks to Manitou Fund for their continued support in fostering interdisciplinary design collaboration at the University of Minnesota College of Design through KDI.

Leadership Lessons from Birds

INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PEOPLE AND PLACE

Embracing Ecosystemic Connections FROM HEALTHCARE TO HUMAN FACTORS

Multi-disciplinary Career Moves

CREATIVE EXPLOITATION

Ethics Education in the College of Design

WHAT IS PLAY?

Unlocking the Essence of Play

CREATIVE CONDITIONING

Setting the Scene for Your Creative Flow

ALCOVE

Located at Rapson Hall Architecture Library

Along with many others, I often feel a great amount of hopelessness when facing the global climate crisis and the threatened continuity of habitat and species on earth.

Global warming, fear of sea-level rise, refugees fleeing uninhabitable spaces, unbreathable air, cities drowning, ocean acidification, permafrost melting, wildfires, disappearing coastlines— an uninhabitable earth for humankind.

The Intergovernmental SciencePolicy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) reports that nearly one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction.1 Nature is in a dangerous decline, and we are unable to look away from the fact that the planet’s average surface temperature has risen 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) since the late 19th century amidst an increase in human-generatedcarbon dioxide emissions. Credentialed scientists are informing us that “no plausible program of emissions reductions alone can prevent climate disaster.”2 The pace of development has

only intensified, and global exploitation of people and place continues to cause dread, anxiety, and despair.

The earth cries as the delusion of our separateness perpetuates. As you are reading this, you may start to feel a sense of tightening in your shoulders, or are holding your breath with an uneasy tension. This information is difficult to process and respond to. I want to invite you to take a moment to connect with yourself and notice what is happening in your own system, energetically and emotionally.

Feeling overwhelmed when digesting this information is understandable. Allow it. Mourning the loss of ecosystems and species is likely to become more prevalent around the world. Grief is a universal and natural response to loss and includes a range of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral reactions.

My project, Love Letters to the Earth, engages participants with a platform to acknowledge and process “ecological grief,” which is a response to loss or anticipated loss due to chronic environmental change. Love Letters

to Earth participants have spoken about their own habitat loss and displacement. Worries transform into a voice, a voice written onto seed paper, seed paper into a flower, a flower into a feeling garden that is in support of wholeness.

WORRIES TRANSFORM INTO A VOICE, A VOICE WRITTEN ONTO SEED PAPER, SEED PAPER INTO A FLOWER, A FLOWER INTO A FEELING GARDEN THAT IS IN SUPPORT OF WHOLENESS.

Below: participants write and draw onto handmade seed paper. Opposite: participants plant their seeded letters into the soil at Rabanus Park.

Photos: Ann Arbor Miller

Together we have written poems to earth, made drawings, and written promises and fears on seed paper and gently covered them with soil. Allowing and sharing ecological grief can form a connection with the greater web of life. These actions can grow and inspire gestures toward caring for earth and climate activism.

The Love Letters to Earth project has been inspired by spiritualists, ecologists, scientists, Indigenous wisdom, eastern philosophy, systems thinkers, and artists. It is a method of finding a way to transform despair into action and healing by turning toward suffering and dissolving ideas of the separation of mind and body, subject and object, human and nature.

During the development of Love Letters to Earth, I was in my first semester of my graduate program in landscape architecture. I was learning about systems thinking and ecology for my classes and reading spiritual teachings in my spare time. I was overwhelmed studying the state of the global climate crisis and deep in the doom and gloom of our shared reality. I found nourishment reading about the invisible heart felt connection to the greater whole and came across mystic Llewellyn Vaughn Lee’s work, Spiritual Ecology: The Cry Of Earth, which prompts us to reassess our underlying attitudes and beliefs about the Earth and wake up to the spiritual and physical responsibilities we have to take care of this planet.

Vaughn Lee wrote, “The world is not a problem to be solved; it is a living being to which we belong. The world is part of our own self and we are a part of its suffering wholeness. Until we go to the root of our image of separateness, there can be no healing. And the deepest part of our separateness from creation lies in our forgetfulness of its sacred nature, which is also our own sacred nature.”3

In the world today, wherever we look we find evolution, diversification, and instability. Cause and effect. We are not separate from the echinacea flower that provides us with carbon dioxide and oxygen, or the earthworms that sift and enrich the soil to promote growth.

While studying ecological systems, I was elated to discover that systems thinkers and scientists were researching spiritual ecology and interconnectivity with a Western approach, describing complex systems that are constantly evolving and interacting with each other: atoms, molecules, cells, organs, bodies, families, societies, and ecosystems.

Ever since Descartes, Western society has embraced a destructive dualistic philosophy that the body and mind are two distinct entities. This separation of mind and body, human and nature, promotes individualism by ignoring the embodied mind. Philosophers and spiritual teachers have argued against this concept and modern day neuroscience provides evidence to support that biological properties and cognitions are linked through behavior.

In other words, the observer (you), must use your own biologically based cognitive system, which is part of a larger system (atmosphere, nutrients from plants, light from the sun, and so on…), and therefore is not independent of biological, social, and cultural contexts.4

Understanding the ways in which systems are interconnected and how they behave is perhaps our best hope for making lasting change. The basis of systems theory is a relationship between structure and behavior, and ultimately transcends disciplines and addresses the many environmental, political, social, and economic challenges that we face globally. Elements, interconnections, which purposes within systems are essential and each have their part.

THE WAYS IN WHICH SYSTEMS ARE INTERCONNECTED AND HOW THEY BEHAVE IS PERHAPS OUR BEST HOPE FOR MAKING LASTING CHANGE.

Systems theorist Donella Meadows eloquently writes that systems rarely have real boundaries. Everything, as they say, is connected to everything else, and not neatly. There is no clearly determinable boundary between the sea and the land, between sociology and anthropology, between an automobile’s exhaust and your nose. There are only boundaries of the word, thought, perception, and social agreement—artificial, mental-model boundaries. The greatest complexities arise at boundaries. There are Czechs

on the German side of the border and Germans on the Czech side. Forest species extend beyond the edge of the forest into the field; field species penetrate partway into the forest. Disorderly, mixed-up borders are sources of diversity and creativity.5

Systems theory in contemporary science resonates with mindfulness and Sufism, Indigenous wisdom, and in particular, Buddhism, which teaches that there is no abstract “knower” of experience separate from the experience itself. Experiences include forms, feeling-sensations, perceptions, impulses, habitual patterns, and awareness. The Buddha described the pattern of life as a never-ending circular journey in which nothing arises independently, but always arises in relation to other phenomena: “We are not separate, we are interdependent.”6 Or as American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer wrote, “All things are delicately interconnected.”7

Whatever your religious or spiritual beliefs are, there are threads of wholeness and connectedness that lead us to our deeper selves and the sacred wonder and joy of life that is our heritage. One of the first steps to sustainability for all creation is to recognize that we have been sold a story that is destroying our ecosystem. To see through the idea that materialism will not fulfill us, but has left us spiritually starved, unfulfilled, and in a mode of extractive damage to our ecosystem.

The Love Letters garden is an expression of tending and interconnectivity. We planted our fruitful intentions into the ground, where they will eventually blossom into temporary fragrant beings in support of an ecosystem of insects and bird species. We observe the garden’s beauty and care for the garden. The garden will eventually fade with the seasons, and we observe the impermanence of life itself.

With the support of Franconia Sculpture Park 4Ground Midwest Land Art Biennial and the Plains Art Museum (specifically the help of Emma

“GARDENING IS A REVOLUTIONARY ACT.”

-JULIAN RAXWORTHY.

Tomb), we found the perfect home for the Love Letters garden at World Garden Commons in Rabanus Park, a community park project developed by ecological artist Jackie Brookner that includes wildlife, wandering paths, a storm water basin, a community orchard, and art.

Smooth blue aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), stiff goldenrod (Solidago rigida), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), blazing stars (Liatris), and snowdrop anemone (Anemonoides sylvestris) were a few of the species used to create perennial seed paper. I worked with my dear friend and master paper maker Kerri Sandve at Minnesota Center for Book Arts in Minneapolis to make over 100 sheets of paper on the evening of the lunar eclipse. The paper was gorgeous, with dried flower

petals to give it a celebratory sense.

I traveled to Fargo to prepare the site with my team, Kyle Thurston and Henry McGlasson, who are both landscape architects and have experience in planting and working with the earth. We hauled compost over to our circular site and spent the afternoon planting plugs and organizing where to plant the seed paper. As we planted in the sun, I was reminded that “gardening is a revolutionary act.”8 It benefits our physical bodies through vitamin D exposure, exercise, and reduced stress levels. It adds beauty, observation, and biodiversity generation. We made the Love Letters garden into a 25 foot diameter circle. The circular form of the garden represents wholeness. Planting in the circle together, weaving in and out, felt like walking a labyrinth. As I worked with the red clay soil, I reconnected to the earth’s offering of

balance and relief. I was brought back home.

The Love Letters to the Earth planting event was held on June 4, 2022. 45 mile per hour winds swept across the fields, making the invisible visible in fluttering aspen tree leaves and tall yellow prairie grasses. More than 30 people attended the Love Letters event that day. I embraced the wind as a participant itself. I have a soft voice and needed a microphone to facilitate over the vibrant wind, and I was worried that the group wouldn’t want to speak into the microphone, but many people shared their experiences and love of nature.

People shared their memories of moose sightings, shooting stars, family puppies, paddling the river, experiencing the redwood forest, and listening to the rain. They shared their fears and worries about drought, water supply, rainforest extraction, COVID-19, and global food supply shortages. We connected to the earth by choosing to see our love and pain for it. Within that, we found openness and connection to ourselves and each other.

Below: participants discuss ecological grief. Opposite: garden prepared with the help of Henry McGlasson and Kyle Thurston.

Iwas in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA) of Northern Minnesota on day five of the canoe trip of a lifetime. My thighs strangely hurt the most, not my core or arms after hours of paddling and portaging, but instead, everything from the rear down is taking the gold medal for ouch. I soon realized I had been logging countless rods of land-side portaging pottying, time spent expertly aiming acrobatic canoepaddling piddles. Plus, I pregamed the trip with a five-hour drive with only roadside pit stops—all in the squat

position. I’ve spent my whole life peeing in the bush, but never on the bush. It was this BWCA trip that made me want to change that.

As a non-binary product designer specializing in gender-inclusive outdoor equipment, my quest to discover gear that cultivates confidence and comfort in outdoor settings has become both a personal passion and a professional mission. I often grapple with the outdoor gear industry as I strive to find products that empower me to excel in outdoor pursuits. Interestingly enough, I’ve discovered a surprising

source of confidence in two pieces of gear that reside at the far end of the conventional gender spectrum. These items address practical needs, such as solving my squatting challenges, and symbolize a broader journey towards inclusivity in outdoor gear design. Those two pieces of gear are the Kula Cloth reusable pee cloth and the Pibella stand-to-pee (STP) device.

For those unfamiliar, STPs or pee funnels are devices primarily marketed towards women, designed to facilitate urination while standing. They’re particularly popular for outdoor

activities like camping, backpacking, and sports events where restroom facilities may be limited. Pibella is promoted as an STP that allows females to urinate comfortably, safely, and discreetly while remaining in a standing position. Like many other STPs, Pibella is marketed with vibrant feminine branding.

Despite Pibella’s gendered pitch, it has garnered a devoted following within the queer community, who appreciate its compact size and color options for STPs beyond just pink. It’s not uncommon for outdoor gear products to find unexpeted popularity among communities for whom the weren’t initially designed. This phenomenon underscores the need for a broader shift in outdoor equipment design to accomodate the diverse needs of all users. Until then, stories like Pibella’s resonance with the queer community serve as a reminder of the ongoing need for inclusivity in outdoor gear design.

If you’ve never used a pee funnel before, be prepared for some technical challenges. Pee funnels come in various designs, either inserting slightly into or cupping around the user. Each brand and style tends to have mixed reviews online. But with a lot of practice and some good luck, there are whispered promises of little need to drop trow to ankle town while using a pee funnel. The first time I used a pee funnel (successfully) I felt like Julie Andrews mid-spin on a hilltop, with the wind at my back and a song in my heart. But I quickly learned that there was still a need for some post-use freshening up.

For those who aren’t keen on airdrying, coupling a reusable pee cloth with your funnel is essential. That’s where the Kula Cloth comes in. It’s eco-friendly, odor-resistant, promotes good hygiene, and kicks the drip-dry method to the curb. No more packing out toilet paper. No more stinky classic cotton hanky. The inside of the cloth is made of an absorbent silverinfused fabric that’s antibacterial and

nontoxic. The absorbent side is black, preventing urine or other stains from showing. A snap also allows the cloth to be folded in half for privacy while it’s out in the world to dry off.

Unlike Pibella and many other urination-adjacent devices on the market, Kula Cloth has taken a gender-inclusive approach to its marketing. Where pee funnels are highly personalized, the Kula Cloth is a one-size-fits-all game-changer that mops the floor with the other contenders. The Kula Cloth boasts that it was “designed for anybody who squats when they pee (or uses a pee-funnel)!”

For an added cool factor, Kula Cloth partners with artists and organizations—rad people who do

good in the world—to make neat patterns and designs for their pee cloth exteriors. I dig the design I picked so much that I take Kula Cloth’s recommendation on their website and snap my cloth to the outside of my backpack to wear like a flag of pride while it dries. Pairing the Pibella with the Kula Cloth creates a powerhouse dream team that empowers you to go anywhere with confidence and zero waste.

It’s inspiring to see brands like Kula taking proactive steps toward creating a more gender-inclusive outdoor world that embraces all stakeholders. While the Pibella maintains a heavily gendered marketing strategy, its efforts to offer a broader spectrum of colors are a step in the right direction.

Ihave always loved birds; they are unique, resilient, and beautiful creatures. It’s astonishing to consider how such a fragile, lightweight creature can endure hours and even days of continuous flight. The bar-tailed godwit, for example, holds the record for the longest recorded flight. A fivemonth-old specimen of this species traveled 13,560 kilometers from Alaska to the island of Tasmania in 11 consecutive days. A research team of scientists from the US Geological Survey, the Max Planck Institute, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, verified that despite having opportunities to rest or feed, the bird decided to continue its way. Can we ever achieve such efficiency?

At an engineering level, we have attempted to replicate these lengthy journeys. The longest current flight connects New York with Singapore, spanning 15,343 kilometers and lasting approximately 18 hours and 40 minutes. However, the environmental impact of this flight does not compare to that of the bar-tailed godwit. A one-way trip between New York and Singapore emits around 5.5 tons of carbon dioxide (tCO2) per passenger, approximately a third of the average CO2 emissions for a person in the US. It’s essential to remember that, during the Paris Agreement, it was estimated that individuals must have a yearly budget of 1.6 metric tons of CO2e emissions to limit global warming to a relatively safe 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Frankly, we will never match nature’s efficiency. Technology has brought us closer, but as long as our energy sources continue to rely on non-renewable fossil resources, our attempts to emulate birds in flight will continue to be just that—attempts. Nevertheless, there are many other things to learn from birds, from designing aerodynamic shapes for our vehicles to using pigments for color formation, and even taking inspiration from nests in architectural design.

One particularly captivating strategy from these fascinating animals has inspired a significant project in my life. According to a 2001 study published in the journal Nature,

the V-formation flight of great white pelicans conserves the energy of each bird by utilizing the aerodynamic advantage of the activation field created by the wings of the bird in front of it. Weimerskirch and his team verified that flying in a V formation allows white pelicans to reduce their energy expenditure while maintaining a similar speed. What’s remarkable about this evolutionary strategy is that birds consistently shift their positions to optimize energy consumption, forming a rotating V shape and preventing fatigue for those leading the formation.

We can combine the strategies of these two birds and apply them as inspiration in our daily lives. While we may not engage in an activity for 11 consecutive days without stopping like the bar-tailed godwit, working in a team and adopting a rotating leadership structure, as the white pelicans do, can make any objective achievable. This philosophy has been a cornerstone of my company for over a decade. In 2013, when I joined what is now my company, one of my partners completed five years as CEO and was suffering from stress and fatigue. Running a small business is demanding. It means juggling many roles simultaneously: directing, producing, and dispatching orders. Leading for five consecutive years is not easy; it is tiring and has consequences. At that time, I was studying biomimicry, and the Nature article crossed my mind. I knew immediately what we should do: fly like white pelicans! Since then, we have implemented a leadership rotation policy among the three partners, requiring us to switch positions every two years, even if we don’t want to.

This policy has achieved positive results for the company on a productive level and for the partners on a personal level. Our collaborators have benefited from our diverse knowledge and leadership styles, and we, in turn, have gained time to achieve other study and personal goals, such as having a family or pursuing a doctorate. After all these years, we have learned that flying in a group is more efficient and yields better results. The three of us know that we can’t fly alone forever, but together, we’ve been able to stay aloft for 11 years.

Since the earliest days of humankind, humans have been intricately intertwined with the natural environment—actively shaping, altering, adapting, and developing ways to inhabit diverse regional landscapes. The influences of the natural environment resonate through cultural beliefs, values, institutions, knowledge systems, languages, and practices, indicating that the relationship between humans and the environment are not one of parallel existence, but rather a deep interconnection.9

At the start of the Industrial Revolution, the perception of taming wild landscapes became popular, and the mental, physical, and spiritual shift from interrelationship to exploitation began. The bleeding of the Earth’s natural resources has severely altered ecological systems, leading designers to take a step back and look to fundamentally understand the connection of people and place.

Nature-based solutions “are actions to address societal challenges through the protection, sustainable management, and restoration of

ecosystems, benefiting people and nature at the same time.”10 It’s a term that is being used to describe the reconstruction of place-based socialecological systems. But designers do not have to start from nothing; traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) holds many nature-based solutions. Although colonialism has suppressed indigenous knowledge, it does not mean it was completely lost. The only truly sustainable way forward is fostering both TEK and western science to create functional and meaningful landscapes for people and place.

A social-ecological system describes the dynamic interrelationship between people and the natural environment, illustrating the reciprocal impact of ecological and social systems, manifesting in either positive or negative outcomes. According to Berkes, ecological systems can be characterized as self-regulating communities of organisms interacting with each other and the environment. Meanwhile, social systems encompass the human governance of property, use of natural resources, and world views.11

BIODIVERSITY

Ecosystem, species & genetic richness

CULTURAL DIVERSITY

Within the framework of a socialecological system, we can learn more about how cultures or societies adapt to environmental changes. Questions naturally arise: How do people adapt to life in the desert or on an island? What unique relationships do people establish with the natural world based on the specific environmental systems at play?

The balancing act of the three planes of existence (mental, physical, and spiritual) teeter on the dynamic relationship of a social-ecological system because we share this unforeseen bond between sentient and non-sentient beings.12 This is also known as energy, and as Albert Einstein once said, “Energy cannot be created

Above: relationship between global/regional/ national correlation of cultural and biological diversity and casual relationships between cultures and biodiversity at the local level. (Maffi and Woodley 2012, 5)

Opposite: Taro fields in Hanalei Valley, Kauai.

or destroyed, it can only be changed from one form to another.”

Biocultural diversity is a comprehensive concept defined as “the diversity of life in all of its manifestations— biological, cultural, and linguistic —which are interrelated (and likely co-evolved) within a complex socioecological adaptive system.”13 This term encapsulates the interrelationship between humans and the natural world, originating from the convergence of various disciplines and knowledge systems, such as anthropology, ethnobiology, conservation biology, ecology, and indigenous knowledge.

The essence of biocultural diversity lies in understanding how ecological systems play a fundamental role in shaping culture, ethics, values, and language. Many languages, for instance, are born from the land, using socialecological relationships to articulate one’s connection to place—a way of life that adapts harmoniously to the environmental system from which cultural diversity is born. Local and TEK is a cumulative body of knowledge that evolved with the land through generations.14,15

Cultural diversity, manifesting in many forms, is evident in Hawai`i where it is expressed through mele, oli, hula, mo`olelo, agriculture, kapu systems, and land divisions. These diverse cultural expressions serve as tangible reflections of the deep interdependence between human societies and local ecologies, illustrating how local traditions and practices are intricately interwoven into the fabric of the natural world. As the body of knowledge grew through generations, adapting, researching, testing, and analyzing, the abundance for life has flourished ,creating a substantial culturally and biologically diverse space.

The moku system was developed to manage the Hawaiian social-ecological system.16 It is a land division that is based on ecological zones, and its boundaries align with ecoregions running from mauka to makai (mountain to the sea). This system was able to support the human population, while providing a bio-rich landscape for all life.17 While Hawaiians had to live within a moku system, it did not mean they couldn’t live abundantly. Maintenance was a huge factor in ensuring a bio-rich landscape and was dependent on the biophysical properties of the land and sea.18,19

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS PLAY A FUNDAMENTAL ROLE IN SHAPING CULTURE, ETHICS, VALUES, AND LANGUAGE.

Disturbance regimes were a way to manage landscapes in Hawai`i such as forests, streams, wetlands, and reefs.20,21 In a Hawaiian socialecological system, people finetuned their understanding of landscapes and focused their crop production in transitional zones. These transitional zones created additional environmental niches, which helped increase biodiversity because species that evolved in disturbed habitats evolved to thrive.22

Wetland systems adjacent to streams are examples of transitional zones. Since this type of zone floods often, it shifts sediment and nutrients around, creating disturbance patches that make viable agriculture landscapes.23 Crops like kalo, uala, and fish were produced in transitional zones where the natural environment could still function and Hawaiians could cultivate food production in a sustainable manner.

In western science, the notion that ecology should exclude humans and social sciences should disregard environmental factors has resulted in a dichotomy between culture and the environment.24 This mentality further severed the stewardship of ecosystems—local, regional and global—to create negative feedback that pushed our globalized society into a climate crisis. As greed pushes us to commodify every ounce of the Earth’s natural resource, we are left with our own destruction. This type of biocultural relationship is toxic, disruptive, and can not sustain life in all its manifestations.25 This is known as biocultural homogenization, involving the extensive replacement of native biota and cultural diversity by globalized species, language, and cultures. Consequently, it disrupts the interrelationships between humans and local ecologies.26

Deforestation of a green pine forest to expand agricultural fields is an example of biocultural homogenization which manages the landscape as a commodity to provide and provide alone. This reflects a globalized mentality, amplifying the notion of “a few winners replacing the many losers.”27 This dynamic perpetuates the division between culture and the environment, fostering a globalized society’s belief that only the strongest should survive. We see this homogenization in agriculture, architecture, landscape architecture, and fashion.

Biocultural homogenization goes beyond the physical and creates a toxic relationship in the mental and physical spirit of being. Global standards were formed through homogenization, making people believe that this is the superior way to live, not knowing the entirety of the self-annihilation we do onto ourselves, and the creation of our own geological epoch known as the Anthropocene.

The moku system, a single social-ecological region, showing the vertical and horizontal breakdown of the biocultural resource management framework.31

The terrestrial social-ecological zones.32

As designers, we face profound questions within our ever-changing environment. Our work involves delving into research, analysis, and synthesis of ideas that we aspire to see manifest from the digital realm into the tangible world. We seek to understand the nuanced nature of space—a boundless, three-dimensional domain where objects and events unfold with relativity to position and direction. We strive to unravel how humans and other living organisms not only navigate but also contribute to the shaping of space,

delving into the interactions within it. As social-ecological relationships start to become evident, we see a gravitation towards human-centric designs, often prioritizing the human experience while neglecting the ecological connections surrounding us.

The human-centric approach has historical roots, notably in Western thought during the Industrial Revolution when agricultural landscapes were popularly admired for their beauty, “a living masterpiece created by human hands,” affirming human technological superiority over primal forces.28 But in turn, this

human-centric practice of taming wild landscapes led to the collapse of ecological processes, both worldwide and locally.

AS GREED PUSHES US TO COMMODIFY EVERY OUNCE OF THE EARTH’S NATURAL RESOURCES, WE ARE LEFT WITH OUR OWN DESTRUCTION.

Entering the twenty-first century, designers confront ecological challenges that cannot be fixed overnight. Issues such as climate change, flooding, biodiversity loss, and shifting temperate zones reflect altered ecological processes resulting from human overconsumption and pollution. The repercussions extend beyond the environment, affecting human health directly and indirectly— manifesting as the urban heat island effect, increased natural disasters, reduced life expectancy, waterway pollution, diminished water and food resources, and heightened heatstroke deaths among the elderly.

As our understanding of biocultural diversity deepens and sheds light on the interrelationships between biodiversity and cultural diversity, the concept of biocultural restoration continues to evolve. According to the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, biocultural restoration is “the science and practice of restoring not only ecosystems but also human and cultural relationships to place, such that cultures are strengthened and revitalized alongside the lands with which they are inextricably linked.”29 This evolving perspective emphasizes the inseparable link between the health of ecosystems and the well-being of human cultures, encouraging a holistic approach to restoration efforts.

available that extends beyond the dichotomy of Western science. In order to truly understand indigenous knowledge and practice biocultural restoration, we have to learn it, believe it, and live it. Indigenous knowledge reaches far beyond the mental, physical, and spiritual embodiment of being.

Biocultural restoration supports a way of life and a state of being that has been suppressed by the colonial mentality and homogenization. I encourage you to learn about the landscape you call home and learn its name. A name in itself holds an abundance of knowledge.

In this context, biocultural restoration emerges as a tangible application of the idea that preserving and revitalizing life’s necessitates is protected through conservation efforts for both biodiversity and culture. Recognizing the interrelated and mutually supportive nature 5 the pivotal question arises: What role can designers play in fostering symbiotic relationships between human activities, environmental sustainability, and cultural diversity?

Designers play a critical role in biocultural restoration because our job is never linear, but fluid. As we ground ourselves with the land, it is important to keep in mind that the Earth is never static. It will forever be changing, adapting, and evolving, and we should evolve with it. I challenge my fellow designers to dive deeper into understanding our existence and what it means to pass on our legacy to the next generation. How do we ensure the next generation can evolve the designs we put in place today?

With even a small glimmer of hope, we can change the human-centric perception and the outcome of our future. Although designers have many challenges in understanding sustainability, we have knowledge

What place do you call home? Why was it given that name? If you call Minnesota your home, is its name Minnesota, the land of 10,000 lakes, or Mni Sóta, the land where the water reflects the skies?30

THIS EVOLVING PERSPECTIVE EMPHASIZES THE INSEPARABLE LINK BETWEEN THE HEALTH OF ECOSYSTEMS AND THE WELL-BEING OF HUMAN CULTURES, ENCOURAGING A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO RESTORATION EFFORTS.

Left:

deforestation of a green pine forest for agriculture. Photo: Envatoelements

I’m Tse-Hsun, a former physical therapist in Taiwan, a country known for having one of the most accessible healthcare services in the world. In my career journey from healthcare to human factors and ergonomics, I aim to address the challenges faced by both patients and clinicians due to the overwhelming patient loads in the medical field.

In Taiwan, healthcare providers, including physical therapists, face a demanding influx of patients, which can result in a compromised quality of service. On average, outpatient patients visiting medical centers only have ten minutes to talk to the doctor and 30 minutes to receive treatment by the therapist, limiting clinicians’ ability to help. As musculoskeletal specialists, therapists have to intervene with an average of 35 patients per day, equivalent to 4.4 people per hour, causing exhaustion for both patients and clinicians.

Motivated by these experiences, I shifted my career ambition to integrate human research and design to solve healthcare issues for both patients and clinicians. During a year-long clerkship in a medical center, my experience with short-staffing led me to brainstorm how preventive and monitoring devices could improve the quality of service for patients and the quality of administration for therapists. Pursuing an MS in human factors and ergonomics, a discipline investigating the relationship between the user, product, and system, I aspire to create healthcare products by coupling new technologies and human-centered development methods.

The shift from medical practice to human factors has tested my adaptability, moving from patient-centric

care to a broader perspective that constantly oscillates between human and system scales. When collecting data, interviewing participants, and conducting usability testing, I zoom in to scrutinize the details while simultaneously zooming out to grasp a holistic view of the entire process, system, and user population. Adopting a dynamic, multiscale perspective allows me to gain deeper insights into the interaction between users and the environment. Despite the differences, both physical therapy and human factors involve learning from people, uncovering dysfunctions related to the human body, and analyzing data from users.

To enhance my adaptability, I find great value in actively listening to and learning from the experiences of others. Much like human factors engineers who actively engage with users, gather feedback, and refine product design through iterative processes, I embrace a similar approach as a cross-disciplinary active learner. Fortunately, throughout my two-year master’s program, I have been involved in the Kusske Design Initiative (KDI), a collaborative cohort comprised of designers from diverse fields such as apparel, graphics, product design, architecture, and more.

Within this dynamic group of designers, I engage in conversations with individuals from diverse backgrounds, sparking appreciation for their creativity and social awareness. Each interaction enriches my understanding of people and social dynamics, thereby enhancing my research endeavors. As I transition beyond my master’s program, I remain committed to this approach, actively seeking out conversations with individuals from diverse backgrounds. Embracing varied perspectives will continue to shape my understanding and fuel my ongoing research endeavors.

For first-year graphic design (GDes) students at the University of Minnesota, the portfolio review is a looming threat. It embodies the everpresent fear that their time and effort won’t be enough to pass the bar and that they’ll be relegated to the existential void of an undecided major.

In order to stay afloat in GDes, students must present a competent body of work that justifies their presence within the major. When it eventually comes time to prepare their portfolios, students toil away, hoping to prove their fears unfounded and secure a place in the program. But what if it’s not enough? It’s an idea that permeates the mind of most PreMajors in the program, setting in motion a search for legitimacy in the form of work to pad the portfolio.

In 2020, my first year of pursuing graphic design education, my phone lit up with an email from the UMN GDes program’s American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) chapter. AIGA describes itself as the “oldest and largest professional membership organization for design—with more than 70 chapters and more than 15,000 members.” The email’s subject line read, “Exciting opportunity enclosed: read me!” I opened it with excitement and curiosity.

“Join us for an hour-long Zoom, in which you will take the time to sketch out, draft, or jump straight into designing the logo for [the company]. The client will then deliberate on the drafts and select who they would like to work

with for the remainder of the project later this year or at the start of [the coming year]. Upon completion you will receive $400 (!!!) for your hard work! The benefits: real world portfolio work, solid resume experience, and $400! What could be better than that?”

This is an excerpt from an actual email sent to all pre-majors in the graphic design program in December 2020. When it hit my inbox, I had many of the aforementioned feelings about building up a selection of quality work, so the email piqued my interest beyond pure curiosity. For a moment, I considered the opportunity a blessing. The feeling was fleeting. Despite being new to the program, I was also aware of AIGA as an organization. I had developed an early understanding of typical best practices for a working graphic designer (after all, I was looking for clients). The exploitative nature of the

email started to become clear.

In retrospect, I’m even more appalled by this email now than I was in 2020. At best, it’s a way to get cheap work for a company connected to the University. At worst, it’s a predatory grab at students, who are in a stage of their career that’s riddled with desperation for work samples and a need for cash as young adults fresh out of their parents’ homes.

Even worse is the fact that it came from the University’s chapter of the AIGA, the closest thing graphic designers have to a union in the United States. It’s an organization founded in 1914 that continually seeks to educate designers, hold events dedicated to best practices, and in their own words, “empower designers.” The trio of exclamation points after the petty sum of $400 was disclosed is the icing

on the rotten, demeaning cake of an email invitation, and this email was only the first of many that came after, each promoting an identical event.

Soon after receiving the email, I looked into the AIGA’s official comments on spec work. Spec work is the umbrella term for what the email was promoting—any work done for free, without guarantee that it will be selected, with the eventual promise that, if selected, the designer will be monetarily (or otherwise) awarded. It’s a kind of work entirely based in exploitation and incomparable to anything considered fair in a noncreative industry. It’s challenging to imagine professional dog trainers, for example, lining up to give you advice on how to get your dog to stop barking and only one of them being awarded payment when deemed worthy. This is what the AIGA website had to say about spec work:

“AIGA, the nation’s largest and oldest professional association for design, strongly discourages the practice of requesting that design work be produced and submitted on a speculative basis in order to be considered for acceptance on a project.”

AIGA goes on to say that spec work has inherent risks, including clients’ risk of “compromised quality” and “designers’ risk of being taken advantage of.” Why would the University of Minnesota’s graphic design program promote this to its students, who have little to no experience and are likely, experiencing a client project for the first time? It begs the question of whether those in the program who facilitated this were more interested in acquiring a cheap logo than providing a wholesome educational experience for students within the program.

I spoke to a representative of the AIGA (the national organization, not the state or university chapter) about this in 2021 after seeing this practice occur several times at the University. I had expected them to tell me that

they’d look into the issue, and that hopefully these events would stop happening afterward. It was three months before I got a response. What I heard from them was a shock, to say the least. They informed me that after an internal investigation, AIGA does not have a recognized student group at the University of Minnesota, and they were completely unaware that the group here even existed. Suddenly it made more sense why the UMN chapter was organizing events that went against the AIGA principles—they weren’t bound by any actual obligation to follow those principles in the first place. The UMN chapter was, and likely still is, wholly unaffiliated with AIGA.

With some trepidation, I later spoke to 2021’s student president of the UMN AIGA chapter, and they were unaware of the issue regarding their official status. To be clear, the AIGA chapter at UMN is student-run, but is overseen by faculty within the University’s graphic design program. Student members are primarily responsible for organizing events and engaging with the student body, not interfacing directly with the national or state AIGA. If the UMN chapter’s official status was misrepresented, it was not perpetrated by students.

As this story was being written I reached out to the 2024 AIGA student president at UMN. Much like the president in 2021, they were

unaware of the issue. I later found that the AIGA website says that any university chapter must retain ten members in order to be recognized. The current UMN chapter has just seven. The spec work fiasco and the case of the University of Minnesota’s AIGA chapter represent a vast void in the graphic design program’s training in professional ethics. In my four years as a part of the College of Graphic Design, I received no education regarding ethical practice. The moral implications of taking on certain clients, red flags to look out for when starting new projects, the overwhelming negatives of free pitching, and other critical issues that every graphic designer should be aware of haven’t been mentioned once in a lecture. These aren’t fringe topics, they are essential to being a successful working graphic designer in the United States.

I don’t blame any of my professors. In fact, I’m not writing this to place blame on any party but rather the program as a whole. The cost of this institutional ignorance will fall on graduating students who begin their careers either as in-house, agency, or freelance workers. When they face an ethically challenging situation, they’ll have no prior knowledge to fall back on other than what they’ve taken the initiative to learn themselves. Likely, the best education will be what students learn from preventable mistakes.

UNLOCKING THE ESSENCE OF PLAY: A DEEP DIVE INTO EVERYDAY ACTIVITIES

YILING ZHANG

Consider the myriad activities woven into the fabric of everyday life: daydreaming, dancing, joking, making bets with friends, skateboarding, singing, shopping, partying, and watching horror movies. Surprisingly, these seemingly disparate activities share a common thread—they all exemplify play. But how do we defind play based on these shared features?

The word “play,” much like other seemingly simple concepts such as culture, identity, and self, proves to be a complex enigma. It functions as an enormous umbrella concept, capturing many activities that Wittgenstein aptly describes as “family resemblances.”33 These activities share features within the group, yet none are exactly the same.

Historian Johan Huizinga contributes the most quoted definition of play in his seminal work Homo Ludens. According to Huizinga, play is a free activity consciously standing outside ordinary life.34 It is simultaneously “not serious” and absorbs the player intensely. Play is an activity connected with no material interest or profit, operating within fixed rules and boundaries of time and space. It encourages the formation of social groupings that often cloak themselves in secrecy and emphasize their difference from the common world through disguise or other means.

This definition resonated strongly with me when I first delved into Play studies, aligning with the popular understanding of play. However, Caillois offers a critique, asserting that the definition over-emphasizes “contest” at the expense of other forms of play, such as chance, vertigo, and mimicry.35 As we reconsider this definition, the question arises: What other definitions of play might exist?

In exploring this inquiry, we navigate the realm of possibilities and constraints inherent in everyday life. According to Csikszentmihalyi and Bennett, play is a state of experience where an actor’s potential balances the possibilities allowed by the environment.36 The dynamic interplay between potential and possibilities often leaves a gap, leading to either anxiety or boredom. For instance, an assignment’s difficulty level can induce anxiety, while an overly easy assignment triggers immediate boredom. It is only in the sweet spot of optimal difficulty that work becomes exciting and rewarding. Play uniquely unifies people and their environment, aligning desires with offerings. In contrast, reality’s dualism between self and environment, laden with ambiguous meanings, necessitates negotiating actions and perspectives with others, inducing anxiety and boredom.

D.W. Winnicott introduces the concept of play as a transitional phenomenon between external and internal worlds.37 The earliest forms of play in a person’s life involve interactions with soft textiles like napkins, blankets, and teddy bears, symbolically representing the mother. This transitional phase allows infants to gain self-assurance in controlling the external world to respond to their fantasies. Moreover, playing establishes a direct connection with cultural experiences, influencing a person’s ability to participate in diverse cultures throughout their lifetime.

A captivating perspective emerges when play is viewed as a paradoxical frame, as proposed by Bateson.38 Bateson’s observations of monkeys playing in a zoo reveal interactions akin to a compact, yet the participants acknowledge the difference. The interactions communicate and are framed by the message “this is play”: a nip denotes a bite, but it does not denote what would be denoted by the bite. This idea of frame extends beyond play, shaping Goffman’s understanding of social situations39 and Gombrich’s definition of artwork.40 The frame, whether in artwork or an art gallery, evokes attitudes that treat it as art.41

Concluding this exploration is Gadamer’s striking definition, asserting that the subject of play is play itself. Gadamer rejects forming the definition based on players’ subjective experiences.42 Inspired by the play of waves and sound, he characterizes play as an autonomous and self-generating to-and-fro movement. Gadamer underscores the centrality and power of play in its domain, and play has its own spirit. This notion resonates with our experience of being absorbed into play, unable to resist its pull, and losing ourselves to it. It can also be recognized as a feeling that a game is spoiled by cheating. Good players, in essence, sustain the movement and the perpetual dance of play.

Unravelling the essence of play within everyday activities reveals a profound tapestry of experiences that transcend mere recreation. Play, in its myriad forms, becomes a dynamic force shaping human interactions, cultural appreciation, and the very fabric of our existence.

Students often encounter design blocks when they start a new project, feeling unsure about where to start or how to find inspiration. Each of us uses personal strategies to get our creative juices flowing. I’ll share key methods for curating an environment that fosters creativity and valuable insights from my peers.

Establishing an optimal work environment is crucial for fostering productivity. Natural light and physical comfort play a pivotal role in our ability to spend long periods of time on a single project. Personally, I find myself drawn to large windows and sunlit spots, like the Rapson courtyard in the afternoon.

The importance of physical comfort in a creative workspace cannot be overstated. Lilly Kuiken, a third-year product design student, shared her challenges with her less-than-ideal home setup, stating, “I will be at my desk, but the lack of comfort keeps me from sitting there for a long time.” Seeking a more comfortable setting, Lilly often ventures to other parts of campus, favoring Lind Hall for its warm aesthetics, adjustable seating, and overall cozy vibes that lead to a great work environment. However, she notes that projects requiring numerous materials limit location options.

Accessibility to supplies is crucial for seamlessly transitioning into creative projects. Skye MacCoon, a second-year art student, underscores the importance of material access in his work process. He emphasizes the significance of being in proximity to materials, with easy access being a priority. For Lilly, preparing materials the night before enables her to jump straight into her

work the next day, overcoming the challenges of organizing materials in the midst of her creative flow.

Music is an integral part of most students’ workflow. Whether you prefer a lo-fi study playlist or a random mix of your favorite tracks, music is a great way to stimulate the mind during project work. Lately, I’ve started tailoring the genre of music I play to align with my desired design style. When working on something with a fast and active aesthetic, I play music associated with those feelings. The same goes for designing products with soft or aggressive form factors.

For instance, last semester, I worked on a design of a shoe that was very layered and had a wavy form factor. As I drew sketch ideas for this shoe I listened to music that was very

textured and had synths that felt like waves layering on top of each other. I found myself drawing curves that matched the flow of the synths in the songs I listened to. This led me to push myself to explore creating forms that resembled different wavelengths that were something I might not have usually thought of.

Even after you’ve found the right location and vibe to start working, initiating a large and intimidating project can be daunting. If you find yourself struggling with this hurdle, consider these insightful tips from Lilly: “Usually I start with the smaller tasks. I am an avid list maker. All my tasks are divided into lists and organized on Google Calendar. The most challenging aspect for me is not knowing how to kickstart my project. I start by outlining all the necessary steps to

begin. I then organize these steps and, once I have a task that is small enough and straightforward, I dive into it. Having a clear, direct task to start off with, like go to CVS to pick up [blank] thing, rather than a vague go find materials, Is very helpful.”

At the same time, Lilly warns us of the potential double-edged nature of this approach, as breaking down tasks can lead to an endless list if not managed carefully. Despite this caveat, Lilly emphasizes the overall effectiveness of this method in breaking down and initiating a large project. Her advice on being specific about how tasks break down is something I intend to implement into my own workflow.

Pulling inspiration for projects is another valuable strategy for lowering the barrier toof entry and initiating a big project. This phase helps us transform concepts into visual form. Platforms such as Pinterest and Behance are great websites to find inspirational images and projects. Using tools like Miro or PureRef allows you to organize and arrange all your inspiration images in one place. Inspiration for design projects extends beyond drawing ideas from similar design work. A unique approach shared by Lilly explores using other interests as lenses through which to develop design projects. “I love exploring other disciplines or projects I’m involved in to inspire my product design work. For instance, contemplating math during the creative process steers me towards a more structured, numerical, and ordered design approach. I ask myself, ‘If I were to add math to this what would it do?’ On the other hand, examining my project through an event planning lens offers a different framework for approaching my product design work.”

Sketching is a key part of the design process for many design students. Recently, I’ve enjoyed drawing inspiration from my surroundings relying on only a 4.5”x8” sketchbook, two Pigma Micron pens, and three cool grey Copic markers for jotting down quick form studies while I’m on the go. When selecting a product to sketch, I like to reflect on the intended user, how the design’s form influences its use, and potential points of contention within the design.

To diversify my drawing styles, I like to give myself a variety of drawing exercises. My current favorite is trying to represent an object purely through its shadows, using just one or two markers. This exercise sharpens my perception of light and shadow, offering insight into how light behaves. A fun way to build off of this exercise is to then transform the original shadow into a new object. I highly recommend trying this technique, all you need is paper and a black and/or grey marker.

The choice of medium significantly influences the appearance of your design. My drawing approach varies considerably between analog and digital sketching. A great way to generate diverse ideas for a project is to experiment with different media. For digital projects, try creating thumbnail drawings using pencils, markers, or charcoal. Allow the medium to generate different styles and inspire new forms. Skye shares a similar perspective on using different mediums to generate project ideas, stating, “I come up with different ideas based on the material or medium I use. For a digital project, I make sure I grab a sketchbook, pencils, or pens, and sketch it out.” The next time you’re feeling uninspired, free up your mind by going on a short walk with a small sketchbook and your favorite writing utensils.

Every designer experiences feeling stuck during different phases of the design process. When you hit those roadblocks, reaching out to others and discussing your project can be a game-changer for pinpointing issues and working towards a solution. Skye shares his approach to working through project ideas with others. “I love thinking through my ideas out loud. I often discuss ideas with my friends, exchanging thoughts and working through them verbally. Oftentimes I need someone who I can talk things out with and perhaps not use their ideas directly, but use their thoughts to inspire my own ideas. Verbalizing my mental processes helps me establish a starting point. It’s important to learn how to articulate ideas in a way that’s understandable to those not familiar with the art medium, using emotional and abstract concepts to translate music or art into something tangible.” Many of the best ideas don’t emerge in isolation; they evolve through discussions with others. Gaining fresh perspectives and insights is invaluable in the creative process.

I hope these strategies for creative conditioning prove helpful as you set up your working environment and embark on your projects. Learning about what other design students take inspiration from is fascinating, so please reach out and share what inspires you in your design process!

JACOB DOMMER

Next time you’re researching potential materials for an upcoming design project, whether it be furniture upholstery that supports high indoor air quality or architectural finishes that prioritize circularity, check out the KDI Materials Alcove in Rapson Hall’s Architecture & Landscape Architecture Library for inspiration.

The Kusske Design Initiative (KDI) has started a collection of hundreds of biobased and ecologically concientious materials as part of a larger mission to promote biomaterial awareness and experimentation on campus.

The alcove features a variety of product samples for soft goods and hard surfaces: recycled post-consumer paper and plastic, biophilic finishes, and healthy alternatives to common building materials.

The next phase of the Biomaterials Lab project will include a maker space for students to explore and experiment with biomaterials using technology like 3D clay printers and mycelium molds.

MATERIAL COLLECTION CATALOGUE

XOREL METEOR CARNEGIE

XOREL METEOR CARNEGIE

MATERIAL REQUEST FORM

Unlike vinyl, it’s woven from polyethylene and is free of chlorine, PVC, and other red-list chemicals.

Use: acoustic panels, wall coverings, furniture

NORTHWEST PAPER COMPOSITE

RICHLITE

100% recycled (post--consumer) paper content.

Use: cladding, millwork

BROWNS POINT

RICHLITE

100% recycled (post-consumer) paper content.

Use: cladding, millwork

RICHLITE

100% recycled (post-consumer) paper content.

Use: cladding, millwork

GROWN AT COLLEGE OF DESIGN

Mycelium is the root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae.

Use: insulation, packaging, leather, acoustic panels, wall coverings

3FORM: VARIA COLLECTION

Incorporates 40% pre-consumer recycled content. GREENGUARD® Indoor Air Quality Certified.

Use: partitions, wall covering

3FORM: VARIA COLLECTION

Incorporates 40% pre-consumer recycled content. GREENGUARD® Indoor Air Quality Certified. Use: partitions, wall covering

3FORM: CHROME RESIN

Contains 40% pre-consumer recycled content. Qualifies for company’s Reclaim Program. Use: lighting, interiors, signage

3FORM

Engineered post processed resin panel made from post-consumer recycled High Density Polyethylene (HDPE).

Use: countertop

3FORM: VARIA COLLECTION

Incorporates 40% pre-consumer recycled content. GREENGUARD® Indoor Air Quality Certified. Use: partitions, wall covering

3FORM: CHROME RESIN

Contains 40% pre-consumer recycled content. Qualifies for company’s Reclaim Program.

Use: lighting, interiors, signage

3FORM: STRUTTURA

Lightweight honeycomb polycarbonate paneling. Provides both light transmission and privacy. Use: interior and exterior wall, ceiling, and floor applications

3FORM: VARIA COLLECTION

Incorporates 40% pre-consumer recycled content. GREENGUARD® Indoor Air Quality Certified. Use: partitions, wall covering

TORZO SURFACES

Produced by infusing renewable and 50% pre-consumer recycled sorghum straw with acrylic resin. Use: interior architectural surfaces

FABRIC

WOLFGORDON

Cork is stripped from the bark of a “live” cork oak trees then air dried, boiled, and shaved into fine sheets.

Use: furniture, upholstery, interiors

WOLFGORDON

100% Wool fabric upholstery. Colors: Basil, Lumine, Cloud.

Use: furniture, upholstery, interiors

WOLFGORDON

Wallpapers that are comprised of mica chips, a mineral formed from a chemical reaction between quartz and granite. Use: wall covering

CORK UPHOLSTERY SOFT MICA

KIREI BAMBOO

KIREI

Manufactured from the fast-growing trunks of the Moso bamboo grass. Strong, dense, and no added urea-formaldehyde.

Use: furniture, flooring, cabinetry, wall covering, architectural millwork

KIREI BOARD COMPOSITE

KIREI

Evironmentally friendly substitute for wood. Manufactured from reclaimed sorghum straw, using a water based polymer-isocyanate adhesive.

Use: furniture, flooring, cabinetry, wall covering, architectural millwork

KIREI WHEATBOARD

KIREI

MDF product made of rapidly renewable resource, recyled content, and non-toxic adhesive. Zero VOC product contributes to healthy indoor air quality.

Use: furniture, flooring, cabinetry, wall covering, architectural millwork

1. Huizinga, J. (2014). Humo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Martino Publishing. Caillois, R. (2001). Man, play, and games. University of Illinois Press.

2. Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Bennett, S. (1971). An exploratory model of play. American Anthropologist, 73(1), pp.45-58. Gadamer, H. (1999). Truth and method (2nd ed.). Continuum.

3. “UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’ - United Nations Sustainable Development.” United Nations, United Nations, https://www.un-.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprec-edented-report/.

4. Wallace-Wells, David. “When Will the Planet Be Too Hot for Humans? Much,

Much Sooner than You Imagine.” Intelligencer, 10 July 2017, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/07/climate-changeearth-too-hot-for-humans.html?regwall-newslet-tersignup=true.

5. Vaughan-Lee, Llewellyn. Spiritual Ecology - the Cry of the Earth. The Golden Sufi Centre, 2017.

6. Shen, Chao Ying, and Gerald Midgley.“Toward a Buddhist Systems Methodology 1: Comparisons between Buddhism and Systems Theory - Systemic Practice and Action Research.” SpringerLink, Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers, 15 Mar. 2007, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11213006-9058-9.

7. Meadows, Donella H., and Diana Wright. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015. ers-Plenum Publishers, 15 Mar. 2007, https://link.springer.

8. Kornfield, Jack. Bringing Home the Dharma: Awakening Right Where You Are. Shambhala, 2012.

9. Holzer, Jenny: Truisms: All Things Are Delicately Interconnected, 2020. Hauser & Wirth, New York City, NY

10. Raxworthy, Julian. “Overgrown Practices Between Landscape Architecture and Gardening”. The MIT Press, Cambridge Mass. 2018.

11. Maffi, Luisa, and Ellen Woodley. Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook. Routledge, 2012. 12. MPR News. “How to Pronounce ‘Mni Sóta Makoce,’ the Dakota Phrase That Will Be on the New State Seal,” December 15, 2023. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2023/12/15/how-topronounce-mni-sta-makoce-the-dakota-phrase-that-will-beon-the-new-state-seal.

13. Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke. “NAVIGATING SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change.” Cambridge University Press, 2009.

14. Branca, Guido. “3 Planes of Existence.” Medium (blog), June 19, 2022. https://medium.com/@GuidoBranca/3-planes-ofexistence-1cced1c99c7d.

15. Maffi, Luisa, and Ellen Woodley. Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook. Routledge, 2012.

16. Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke. “NAVIGATING SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change.” Cambridge University Press, 2009.

17. Maffi, Luisa, and Ellen Woodley. Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook. Routledge, 2012.

18. Winter, Kawika B., Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Mehana Blaich Vaughan, Alan M. Friedlander, Mike H. Kido, A. Nāmaka Whitehead, Malia K. H. Akutagawa, Natalie Kurashima, Matthew Paul Lucas, and Ben Nyberg. “The Moku System: Managing Biocultural Resources for Abundance within Social-Ecological Regions in Hawaiʻi.” Sustainability 10, no. 10 (October 2018): 3554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103554.

19. Van Looy, Kris, Jonathan D. Tonkin, Mathieu Floury, Catherine Leigh, Janne Soininen, Stefano Larsen, Jani Heino, et al. “The Three Rs of River Ecosystem Resilience: Resources, Recruitment, and Refugia.” River Research and Applications 35,

no. 2 (2019): 107–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3396.

20. Winter, Kawika B., Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Mehana Blaich Vaughan, Alan M. Friedlander, Mike H. Kido, A. Nāmaka Whitehead, Malia K. H. Akutagawa, Natalie Kurashima, Matthew Paul Lucas, and Ben Nyberg. “The Moku System: Managing Biocultural Resources for Abundance within Social-Ecological Regions in Hawaii.” Sustainability 10, no. 10 (October 2018): 3554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103554.

21. Winter, Kawika B., and Matthew Lucas. “Spatial Modeling of Social-Ecological Management Zones of the Ali‘i Era on the Island of Kaua‘i with Implications for Large-Scale Biocultural Conservation and Forest Restoration Efforts in Hawai‘i.” Pacific Science 71, no. 4 (October 2017): 457–77. https://doi. org/10.2984/71.4.5.

22. Connell, Joseph H. “Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs.” Science 199, no. 4335 (1978): 1302–10.

23. Van Looy, Kris, Jonathan D. Tonkin, Mathieu Floury, Catherine Leigh, Janne Soininen, Stefano Larsen, Jani Heino, et al. “The Three Rs of River Ecosystem Resilience: Resources, Recruitment, and Refugia.” River Research and Applications 35, no. 2 (2019): 107–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3396.

24. Connell, Joseph H. “Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs.” Science 199, no. 4335 (1978): 1302–10.

25. Van Looy, Kris, Jonathan D. Tonkin, Mathieu Floury, Catherine Leigh, Janne Soininen, Stefano Larsen, Jani Heino, et al. “The Three Rs of River Ecosystem Resilience: Resources, Recruitment, and Refugia.” River Research and Applications 35, no. 2 (2019): 107–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3396.

26. Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke. “NAVIGATING SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change.” Cambridge University Press, 2009.

27. Caillon, Sophie, Georgina Cullman, Bas Verschuuren, and Eleanor J. Sterling. “Moving beyond the Human–Nature Dichotomy through Biocultural Approaches: Including Ecological Well-Being in Resilience Indicators.” Ecology and Society 22, no. 4 (2017). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26799021.

28. Rozzi, Ricardo, Roy H. May, F. Stuart Chapin Iii, Francisca Massardo, Michael C. Gavin, Irene J. Klaver, Aníbal Pauchard, Martin A. Nuñez, and Daniel Simberloff, eds. From Biocultural Homogenization to Biocultural Conservation. Vol. 3. Ecology and Ethics. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99513-7.

29. McKinney, Michael L, and Julie L Lockwood. “Biotic Homogenization: A Few Winners Replacing Many Losers in the next Mass Extinction.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 14, no. 11 (November 1, 1999): 450–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S01695347(99)01679-1.

30. Connell, Joseph H. “Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs.” Science 199, no. 4335 (1978): 1302–10.

31. “Biocultural Restoration.” Accessed March 16, 2024. https://www.esf.edu/research/restorationscience/biocultural.php.

32. Wittgenstein, L. (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell.

33. Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Playing and Reality. Tavistock Publications.

34. Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York Ballantine Books.

35. Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harper & Row.

36. Gombrich, E. (1979). The sense of order. Phaidon Press.

37. Miller, D. (2010). Stuff. Polity Press.

38. Gómez-Pompa, Arturo, and Andrea Kaus. “Taming the Wilderness Myth.” BioScience 42, no. 4 (1992): 271–79. https://doi. org/10.2307/1311675.