ELIO CROCE

Comboni Missionary Brother

To Edo, poet of fidelity.

To Vito and Anna, who offered everything with joy. Friends who mysteriously and unexpectedly preceded us to the Father’s house.

This book belongs to ____________________________________

Filippo Ciantia

ELIO CROCE

Comboni Missionary Brother

Preface by Giulio Albanese

Publishing means bringing things to life.

Our aim is to highlight words that accompany people through their lives.

This is our responsibility as publishers.

Books as travelling companions.

In the Telemaco series

Filippo Ciantia

Father Tiboni “one of the holiest men we have”

Silvia Fasana

Eight hours of eternity

Giacomo’s story

Marta Bellavista I want it all

Filippo Ciantia

Elio Croce Comboni Missionary Brother www.itacaedizioni.it/elio-croce-comboni-missionary-brother

Original title: Elio Croce fratello missionario comboniano

Translation: Neil Bartholomew

First Edition (English): July 2025

© 2025 Itaca srl, Castel Bolognese

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-88-526-0806-3

Images cover

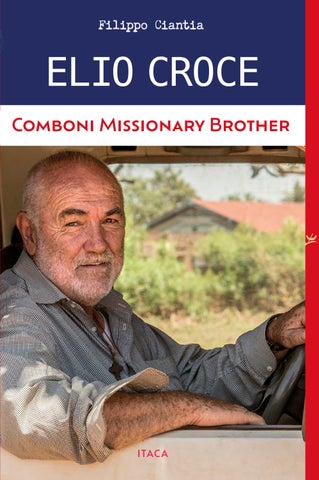

Elio Croce at the wheel, Gulu 2016 (photo by Mauro Fermariello).

With the children and educators of the St. Jude Children’s Home, Kitgum 1972 (photo by Maria Croce).

Map of Uganda by Sofia Crosta.

Printed in Italy by Modulgrafica Forlivese, Forlì (FC)

Follow us on

Preface

The logic connected with becoming inevitably brings memory with it. Perhaps never before has it been so necessary to reflect on the past in order to address the many anxieties of our time. In this way we are enheartened by the knowledge our ancestors had. They understood that everything we have lived through – which means everything that is now past – always manifests itself in personal and collective memory, no matter what we do, and it is manifested in what remains of faces, of people whom Providence has entrusted, in the course of their lives, with the task of offering their testimony to us. For this reason, I warmly recommend the reading of this biography by my friend Filippo Ciantia, which could be described as a kind of missionary breviary.

The pages that follow are, in fact, an outline and, in a certain sense a factual account of the events that, for those who had the good fortune to know him, marked the existence of Brother Elio Croce, an authentic “myth of universal evangelisation”. The author of this preface therefore asks for a dispensation if he too feels the instinctive need to remember this great missionary with a few brief references.

He was an extraordinary person whom I met by chance at the beginning of the eighties in the office of the Comboni Missionaries in Mbuya, a parish on what was then the outskirts of the Ugandan capital, Kampala, before it expanded. I remember that Saturday afternoon as if it were today. I had just returned from a fishing trip on Lake Victoria. Food of all kinds was scarce in the city because of the war, and this was the only way to ensure healthy food for our theology seminarians. I had a pick-up truck full of Nile perch, all of them big, that had been caught in those

waters in abundance. At the time, Brother Elio was working as the technical manager at St Joseph’s Hospital in Kitgum, East Acholi. We immediately became friends.

He told me that he had been there since 1971, so he already had twelve years of missionary work behind him. I was struck not only by his nobility of spirit, but also by his absolutely remarkable affection for the Acholi people he had been called to serve in northern Uganda. As we talked, I noticed that he kept staring out of the corner of his eye at the fish I had in the back of the car. “A wonderful catch today!” he exclaimed. I knew immediately that he would like to take some back to the mission in Kitgum, and I couldn’t help but comply with his request. “God bless you,” he said, pointing out that he would pay me back for the fish by praying a holy rosary for me and my community. To tell the truth, the miraculous catch was his and I can guarantee that it lasted until the day Brother Elio returned to His Father’s house, on 11th November, 2020.

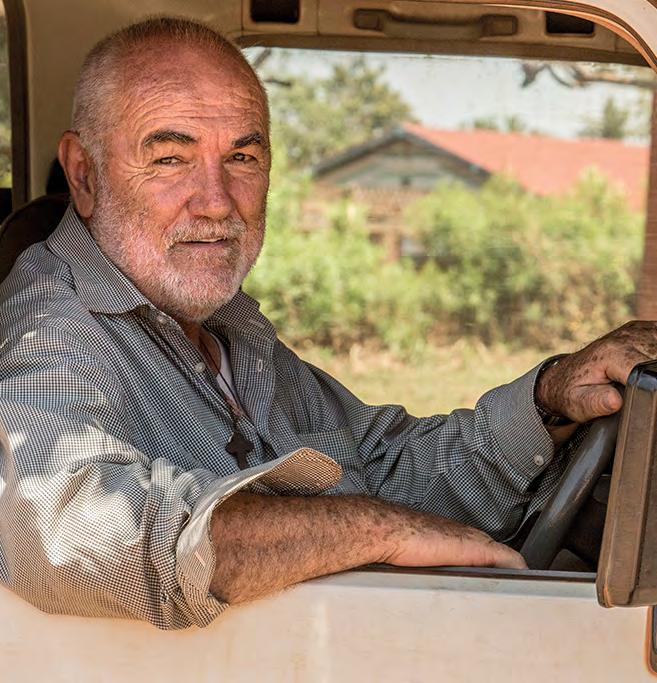

Many have rightly described him as a “Good Samaritan”, always ready to come to the aid of anyone in need: the destitute, the homeless, the orphans, the wounded, the malnourished, the maimed, the sick… There was never a moment in his life when he was not involved in the evangelical practice of charity. This writer can testify to this, having seen him, for example, suddenly stop his old Toyota Land Cruiser and park it on the side of a dusty road so that he could bury, at the risk to his own safety, the bodies of the many civilians killed by the savage soldiers who had ravaged northern Uganda for more than two decades.

I will never forget the day, 29th August, 2002, when he came to collect me and two other confreres (Fathers Tarcisio Pazzaglia and Carlos Rodriguez Soto) from the Gulu barracks in his own 4x4 vehicle, after a bad adventure with the rebels that had culminated in our arrest by government forces. We were exhausted and one of us, Carlos, had a badly burned arm. He immediately took us to the hospital in Lacor for medical tests before offering us a hot meal and hospitality for the night.

A man of prayer, but also a man of action, Brother Elio was

never idle: he was a prodigious worker. He built schools, chapels, orphanages, irrigation systems, flour mills, not to mention his speciality: the construction and maintenance of hospital wards. In half a century of tireless missionary service, he was first the technical director of St Joseph’s Hospital in Kitgum, where he also had the good fortune to meet some young doctors from Communion and Liberation; then, in 1985, he moved to Gulu, to the hospital in Lacor, where he practically lived until his death.

On one of my last visits to Uganda, I came across a local newspaper that mentioned him. The journalist used the same metaphor of the Good Samaritan in connection with the Land Cruiser to describe Brother Elio, with whom he had spent several days, perhaps a whole week. He had hit the nail on the head, for he had realised that this vehicle was used as a hearse, as an ambulance, to transport materials of all kinds, but also as a school bus for the orphans of the St. Jude Children’s Home in Gulu. This vehicle bore the many marks that testified to the numerous activities carried out daily by a man with a big and generous heart.

Maurizio Vitali, who wrote a piece in his memory for clonline.org, wrote that his favourite saying was: “He who does not live to serve does not serve to live.” He did not consider any undertaking or work as his own, but as the work of Providence. With a very simple method of verification: if the work is of Providence, it will continue; if not, it will cease.

One thing is certain: in his many years as a missionary, Brother Elio saw it all: from the catastrophe of the civil war to the Ebola plague and the Covid-19 pandemic that put an end to his earthly existence at the age of seventy-four. Looking at his photograph (there are many on the Internet), apart from the details – a fatigue cap on his head and a rosary in his breast pocket – he looked like Sean Connery’s twin brother.

But beyond these personal considerations, and returning to the author of this biography, Filippo Ciantia, it is worth remembering that everything he has meticulously collected in these pages is largely the result of his strong bond with Brother Elio in Africa. It is therefore a narrative with a deep experiential value,

from which the spirituality of the protagonist, which for him meant living according to the Spirit, emerges.

Ciantia is to be praised for managing to convey the Comboni charisma of the protagonist, that versatile elasticity of the soul that we all need so much at this moment in time, so plagued by inequalities. Or in other words, to realise, according to the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth, that in life “We derive more joy from giving than from receiving” (Acts 20:35).

I wish you a good journey with this book that pays tribute to and enables us to share Brother Elio’s life.

Acknowledgements

The English translation of this book was made possible by Neil Bartholomew’s generous and talented contribution. All my gratitude goes to him because, thanks to his commitment, the life of Brother Elio is now becoming available in Uganda, where he donated his whole missionary life. Vick Ssali, George William Pariyo and Andrea Breen were also kind enough to revise the text and did so with great passion and involvement.

In 1906, an Italian expedition led by the Duke of the Abruzzi, Luigi Amedeo di Savoia, reached the heart of Africa to explore and climb the Ruwenzori Massif, or “Snow Mountains” in the Lukonzo language spoken by the inhabitants of these lands in the heart of Africa, on the western border of Uganda with the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo.

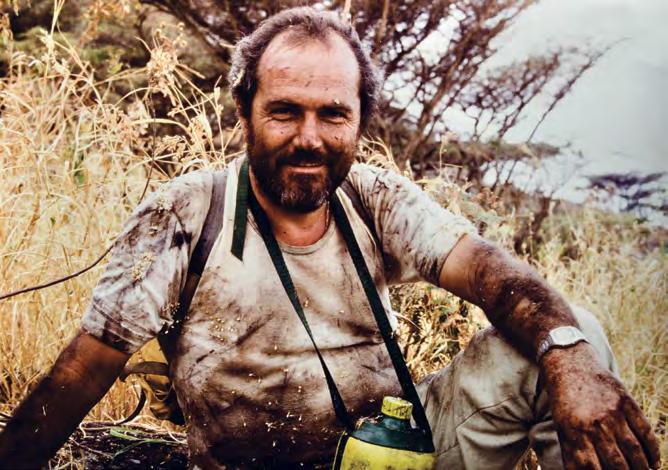

Comboni Brother Elio Croce, born in Moena, the Fairy of the Dolomites, missionary in Uganda from 1971 until his death, could not resist his passion for the peaks and the snow. In February, 1975, with a group of doctors and religious men, he climbed the Margherita Peak, the top of the massif, named by the Duke of the Abruzzi in honour of the beloved and popular Queen of Italy, celebrated by great poets for her grace, majesty, religiosity and smile.

The long preparation for the climb, with several ascents of the Lagoro and Lotuturo mountains north of the Kitgum mission, that served as training, cemented Elio’s friendship with the doctors Giorgio Salandini and Enrico Frontini, two of his companions on the adventurous climb. Those were difficult years, especially because of Amin’s cruel dictatorship. And yet, in those first years in Africa, Brother Elio was able to enjoy the last big game

expeditions in the country where the Nile originates, known as the Pearl of Africa for its natural beauty, fertile soil and smart and capable people.

It was the beginning of an adventurous and fascinating life, epic in some respects, which, in order to be followed and fully appreciated, required the inclusion of a map, skilfully drawn by the young artist Sofia Crosta.

One of Elio’s sisters, Maria, told me that at the beginning of 2019, a few months before her brother’s unexpected and tragic death from Covid-19 pneumonia, he had told her of his wish to write the story of his vocation. His untimely death prevented him from fulfilling his wish! I was provoked and impressed. Unable to resist the fascination of the life of this great missionary, I set out to tell the story of his human and Christian journey, and of his original and exemplary response to the vocation that he felt called to from a very young age.

Writing this book has been an arduous task for me. In the same way as when you climb a mountain, I have experienced fatigue. Between the Ebola epidemic and the civil wars in Uganda, I collected numerous testimonies, read many articles and consulted several books, two of them from his diaries. There are many videos of his testimonies on YouTube. I had known him well during his lifetime, first when we worked together at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Kitgum, then seeing him on a regular basis for work, friendship and shared faith. The growing understanding of his stature, as I researched more and more deeply, took on the truly imposing dimensions of a steep and demanding climb.

As in a challenging climb, however, there are times when the awe and wonder of unexpected landscapes outweigh all fatigue and difficulty. In this way, even in “writing about Elio”, fatigue became a very light burden, leaving room for joyful gratitude for having met a true man of God.

The story of his vocation was made possible thanks to his family, especially his sister Maria, his brother Nino, his nephews and many of his fellow villagers. You will find the encounters that filled his beautiful life. I would especially like to thank the

Comboni confreres and Comboni nuns who have participated in this work with joy and enthusiasm. Elio’s life was rich in friendships: among the most beloved were Piero and Lucille Corti, and Dr Matthew Lukwiya, the people he joined in heaven, to complete the quartet that led Lacor Hospital in its dramatic and glorious years. I wanted to preserve in the text the spontaneity of the stories and narratives of the many witnesses who followed in Elio’s footsteps. I have not been able to mention everyone, but it was almost inevitable. Among the first interviews, I remember the dialogue with Maresa Perenchio, one of the protagonists of the history of St. Jude’s Children’s Home, when she showed me the summit of Monviso from her beautiful house on the morainic hill near Ivrea, and spoke to me about Elio with emotion, gratitude and wise irony. Then the many messages from Giovanna Rondoni, with memories of Kitgum in the early 1980s and of adventurous journeys to Karamoja and Kidepo Park. I will not forget the touching details confided in me by Dr Bruno Corrado, one of the principal people behind the development of Lacor Hospital, who, shortly before his death, learned from his wife that Brother Elio used to fast once a week just for him and his conversion! Finally, perhaps the last interview, the long conversation with Maurizio Surian that enabled me to clarify many details of the Elio’s daily life and spirituality.

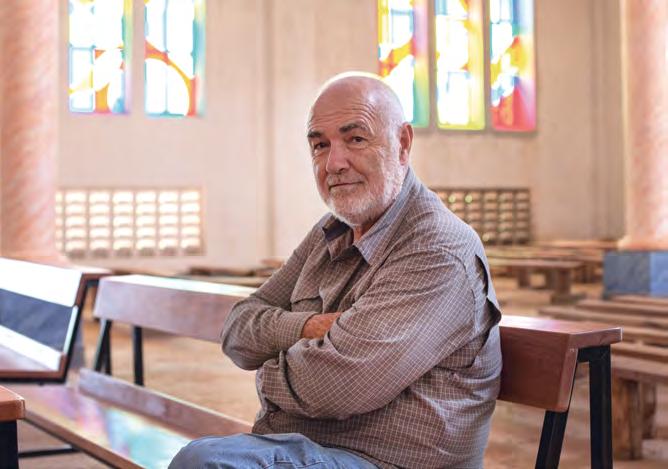

To Maria Teresa Battilana, who through “grace” began to write icons in 1999, I owe the “gracious gift” of the masterly description of the Church of St. Daniel Comboni, Elio’s last truly great work.

Not everything has been reported, both because of the abundance of facts, events and news, and because of the need for more careful verification. Many witnesses, for example, reported Elio’s participation in the destruction of the bridge over the Aswa River by Amin’s opposition partisans in 1979. Several bystanders confirmed that Elio himself boasted of having taken part in and even planned the partisan action that, after the fall of Kampala, prevented the dictator’s troops from fleeing north and crossing the Aswa River in order to reach Kitgum, thus preventing further

suffering to innocent civilians. I imagine him, vigilant and at the same time active, proudly leading a “commando of his workers and partisans”, systematically and cunningly removing the concrete blocks with which the bridge had been built to make it inaccessible to heavy trucks, lorries, tanks and armoured vehicles.

The true protagonists of the book are the many Ugandan and Italian doctors and social and health workers who have worked in Northern Uganda, in the hospitals, in the missions, in St. Jude Children’s Home, for which I thank all the staff and guests.

There is one last aspect that should be remembered and highlighted. Elio was not only appreciated, loved and admired by the Brothers and religious with whom he lived, but he, too, had a deep respect for all of them, especially for the diocesan priests.

His room has remained the same since the day he was transferred to Mulago National Hospital in Kampala, where his earthly journey ended. In an apparent disorder whose secrets were known only to him, among spare parts, working or broken computers, boxes of equipment, wires, electronic circuits and tools, the shelves full of books stand out. Not just equipment catalogues and industrial manuals. The readings that fed his nights and periods of silence and nourished his mind and heart are surprisingly well-ordered and catalogued. The whole of the top shelf is devoted to the Bible, the Gospels and the liturgical lectionaries. Moving down, you find ‘Spirituality’, ‘Saints and Martyrs’, ‘Novels and Classics’ and ‘Prayers, Education, Spiritual Exercises’. Alongside the great Popes of recent decades, texts by Messori and Giussani stand out.

Then, on the bottom shelf, resting on a brown folder, we find a handwritten sheet. It reads: “Fr. Ambrogio. My life…”. It is a brief account of the long missionary life of Father Giacomo Ambrogio from Lusernetta, a small village in the Pellice Valley, Diocese of Pinerolo, Province of Turin: fifty years in Uganda! After so much service to the Church and to the poor, Father Giacomo was given hospitality by the Comboni community in the hospital of Lacor, in the house of Brothers Elio and Carlo. Here many priests were welcomed and cared for, including the dear

Acknowledgements 189

Pietro Tiboni, who “enjoyed” the charity and devotion of his lay brothers, younger than him, but aware that they definitely belong to the great history of the Church in Uganda, Pearl of Africa, but also and above all, land of martyrs and witnesses of God’s blessing on these peoples. Finally, special thanks to Dominique Corti, her husband, Contardo Vergani, and the Corti Foundation for so many insights, contacts, tips and, above all, many and beautiful photos.

Let us begin, brothers, to serve the Lord God, for, so far, we have made little or no profit!

St. Francis of Assisi

“Comboni Missionary Brother”: this is what Elio Croce, who lived in northern Uganda for fifty years at the service of the Acholi people, used to call himself.

Brother Elio Croce, an authentic "myth of universal evangelisation", a "Good Samaritan", always ready to come to the aid of anyone in need: the destitute, the homeless, the orphans, the wounded, the malnourished, the maimed, the sick…

He was a man of prayer, but also of action. He built schools, chapels, orphanages, irrigation systems, flour mills, not to mention his speciality: the construction and maintenance of hospital wards.

Maurizio Vitali wrote that his favourite saying was: “He who does not live to serve does not serve to live”. He did not consider any undertaking or work as his own, but as the work of Providence. With a very simple method of verification: if the work is the fruit of Providence it will continue; if not, it will cease”.

Father Giulio Albanese mccj

Filippo Ciantia lived for thirty years in Uganda with his wife and eight children, working first as a medical doctor for NGOs such as Cuamm and Avsi, then as CEO of the Dr. Ambrosoli Memorial Hospital. He has written La montagna del vento. Lettere dall’Uganda (The Wind Mountain. Letters from Uganda); Il divino nascosto. Storie di eroico quotidiano (The Hidden Divine. Stories of heroic everyday life); Father Tiboni “one of the holiest men we have” and Bobo Torchiana. L'amore non fa male al prossimo (Bobo Torchiana. Love never hurts your neighbor).

16.90