Take advantage of our best banking offer tailored to your profession You and your partner could save up to $1,688 a year*

nbc.ca/architect Discover our offer at

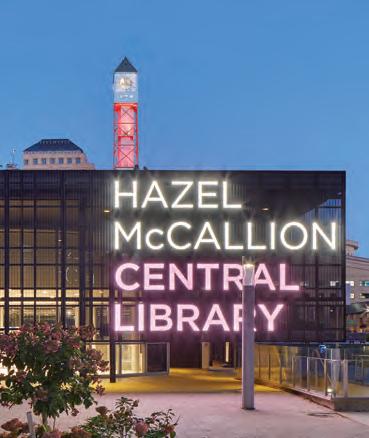

RSHP and Adamson Associates realize a 15-year vision for a downtown Toronto marketplace and courthouse. TEXT Pamela Young

MDO’s civic complex in Quebec’s Saguenay region elevates small-town architecture with contemporary flair. TEXT Peter Sealy

1x1 architecture’s design of meeting spaces for the G7 Summit in Kananaskis showcases Canadian design .

New documents reinforce that Ontario Science Centre closure was not supported by engineers; OAQ Awards; FXCollaborative partners with Lemay.

RAIC Climate Action Plan; Records of Protest ; Truth and Reconciliation Task Force.

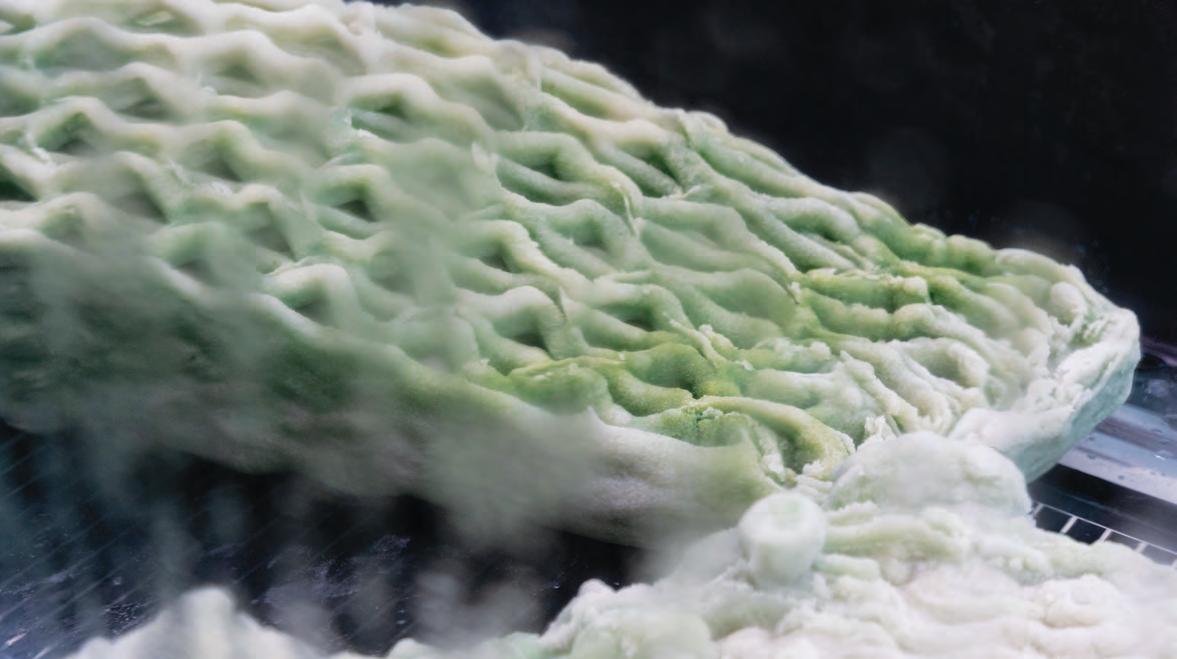

Lawrence Bird visits Picoplanktonics at the Venice Biennale.

44

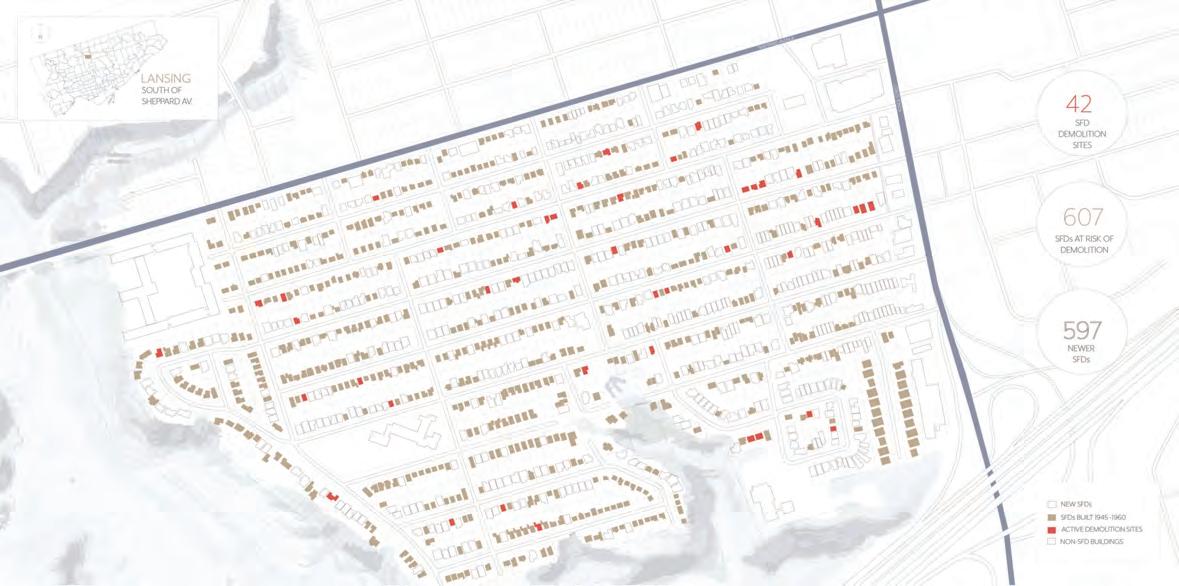

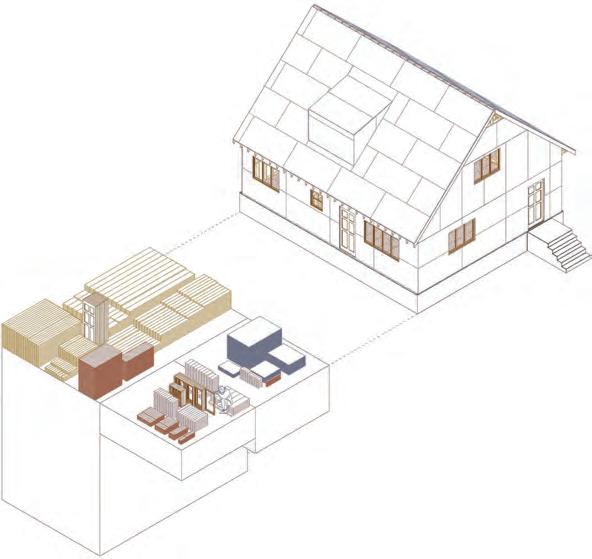

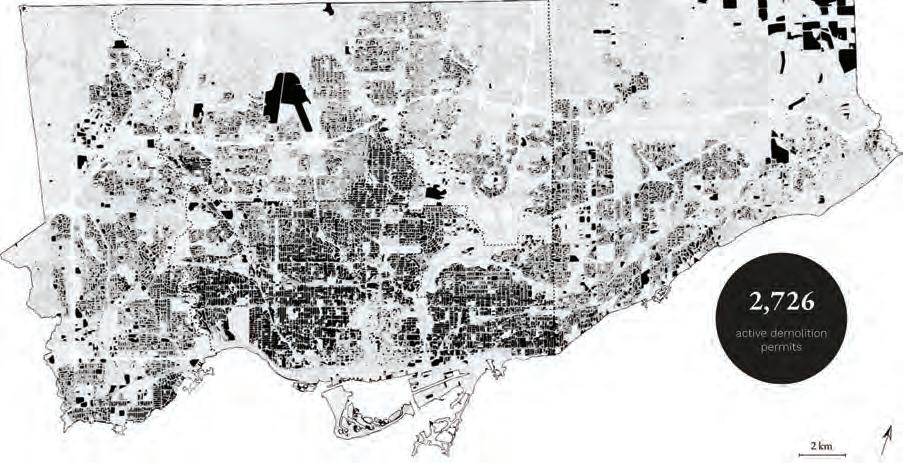

Ha/f Climate Design’s Juliette Cook and Rashmi Sirkar examine the possibilities and barriers to a circular economy for residential building materials.

47

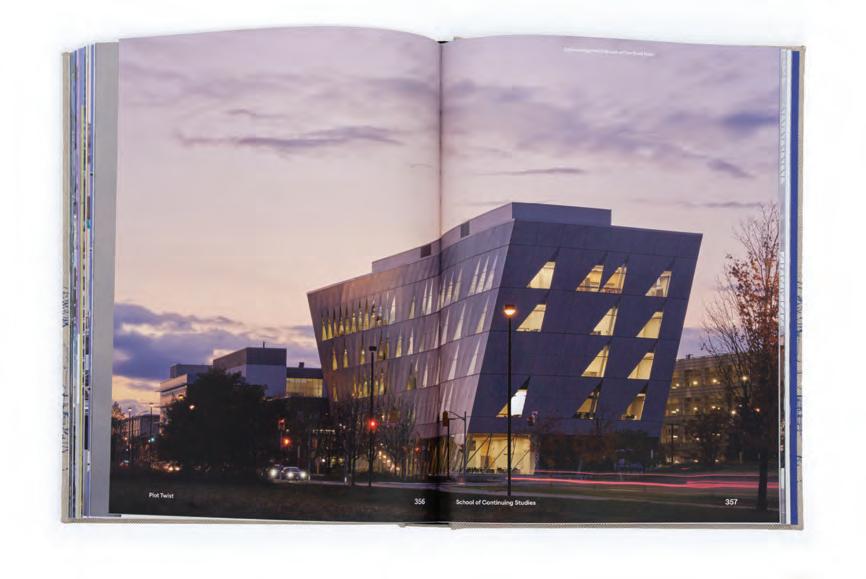

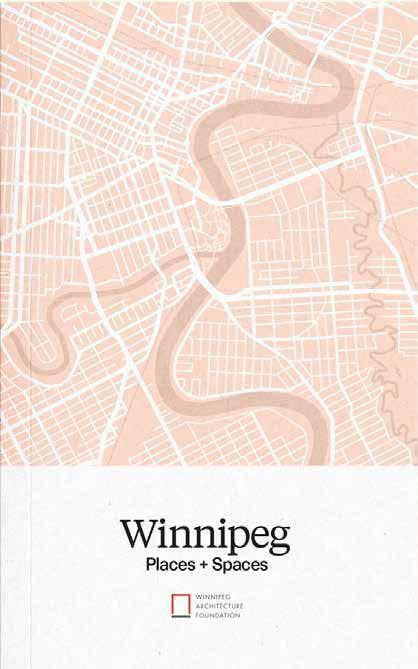

A new architectural guide to Winnipeg, and a monograph/memoir by Perkins&Will’s Andrew Frontini.

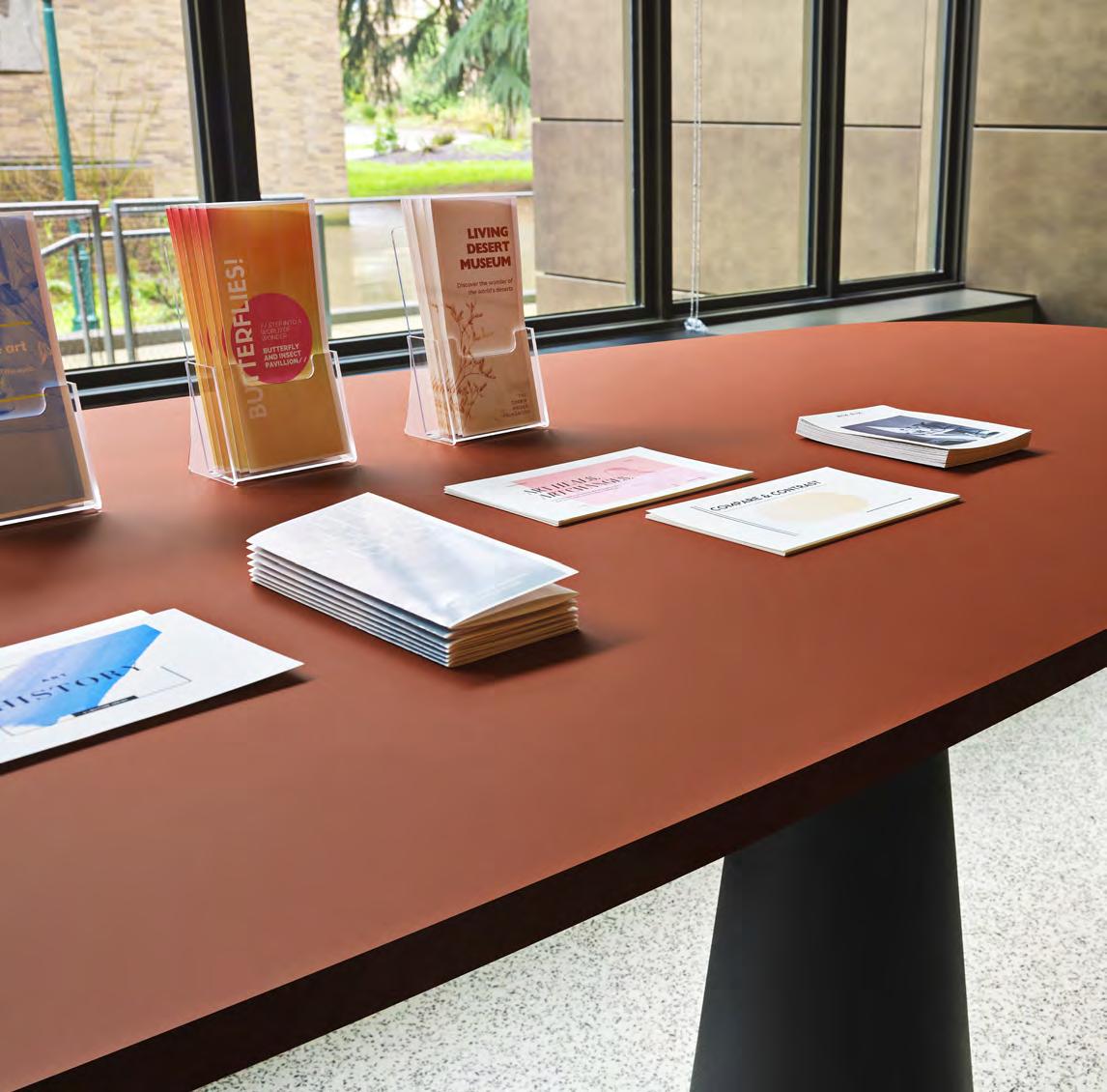

A strategic renovation by RDH Architects gives a modern makeover to a 1990s library. TEXT Elsa Lam

Woodrise and CTBUH conferences come to Canada.

Atelier Pierre Thibault re-envisions the place and potential of the historic smokehouses of Île Verte, Quebec.

COVER St. Lawrence Market North in Toronto, by RSHP and Adamson Associates Architects. Photo by Nic Lehoux

Winnipeg-based 1x1 architecture is one of a handful of firms on a Federal Standing Offer list for the Province of Alberta. While this work usually focuses on pragmatic contracts, last fall, the job list turned up a glamorous exception: the design of a set of meeting spaces for the G7 Summit in Kananaskis. Canada has hosted a half-dozen G7 Summits since the group’s formation in 1977. Those past summits usually took place in historic European-style hotels, with meetings in old-fashioned ballrooms with velvet-curtained windows. But this time around, the team at Global Affairs Canada was determined to realize a different vision: a setting that was decidedly contemporary, sustainably delivered, and proudly Canadian.

Working within the existing conference area of the 1988 Pomeroy Mountain Lodge, 1x1 was tasked with creating and fitting out a series of key spaces. These included the Outreach Room where the seven leaders would meet with the leaders of other nations, and the Bilateral Rooms that hosted one-on-one meetings, such as Prime Minister Carney’s meeting with President Trump. The work was completed on what 1x1 interior design lead Ashley Jull describes as a “fairly aggressive” schedule: after being hired in November, the team prepared drawings for contractor tendering at the end of January, and the build took place over two intense weeks in late May.

1x1 began by lining the walls with custommilled fir panelling. They shaped the ceiling of the Outreach Room to angle towards the centre of the room, nodding to the peaks of the nearby Canadian Rockies and bringing a more intimate scale to the space.

To mask an existing curtain wall with an irregular rhythm, they hung a screen of 16-foot-tall live-edge timbers, collected from

LEFT The design and furnishings for the G7 Summit’s meeting spaces in Kananaskis, Alberta, showcased Canadian design talent.

trees felled as part of a nearby firebreak. “It tells the story of both our softwood lumber exports and climate change,” says architecture lead Travis Cooke. Engaging the principle that biophilic design might make for better decision-making, the move also extended views from the room “right out into the adjacent forest,” says Cooke.

In order to meet Global Affairs’ mandate of showcasing as much Canadian talent as possible, 1x1 rounded up a dream team of craftspeople and manufacturers to realize their vision. Local cabinetry shop Camantra created the wood walls, and the lobby and bilateral rooms were graced with Indigenous designer Destiny Seymour’s drum stools and Winnipeg-born designer Thom Fougere’s Tyndall Stone tables. The layout also featured Patkau Architects’ Maitake coffee table and side chairs by Calgary-based design-manufacturer Mobiüs Objects. Pieces by larger Canadian design brands Teknion, Keilhauer, Nienkämper, and Bensen also found their way into the design.

All of the materials were installed in a way that they could be easily removed and reused in the future. Cooke notes that the hotel is considering purchasing the fir panels, currently in storage, for use in a longer-term renovation of the ballroom, while the government is eyeing the reuse of the furniture at embassy sites.

The project was conceived before talk of tariffs. And yet, it became an apt showcase of the country’s design talent. “It was to showcase Canadian identity, what we’re capable of,” says Jull. The result? A bespoke environment where global decisions could unfold against a backdrop of Canadian design excellence.

EDITOR

ELSA LAM, FRAIC, HON. OAA

ART DIRECTOR

ROY GAIOT

CONTRIBUTING

EDITORS

ANNMARIE ADAMS, FRAIC

ODILE HÉNAULT

LISA LANDRUM, MAA, AIA, FRAIC

DOUGLAS MACLEOD, NCARB FRAIC

ADELE WEDER, FRAIC

ONLINE EDITOR

LUCY MAZZUCCO

SUSTAINABILITY ADVISOR

ANNE LISSETT, ARCHITECT AIBC, LEED BD+C

VICE PRESIDENT & SENIOR PUBLISHER

STEVE WILSON 416-441-2085 x3

SWILSON@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

FARIA AHMED 416 441-2085 x5

FAHMED@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM CIRCULATION

Allies and Morrison, SLA to design urban realm of Ookwemin Minising

Global professional services company GHD, Danish-based design studio SLA, and UK-based Allies and Morrison have been awarded phase one of the infrastructure and streetscape design for Ookwemin Minising, formerly known as Villiers Island, in Toronto.

The new island is planned to be home to more than 15,000 people. The area’s parks, adjoining the renaturalized Don River estuary, opened earlier this summer, and the first residents are expected to move in by 2031.

For the project, GHD, the prime consultant and technical lead, and SLA, design lead for urban realm and landscape, will deliver a new urban environment that aims to honour the legacy of the Don River through an approach rooted in resilient infrastructure, cultural memory and deep ecological integration. The team, which includes architects Allies and Morrison, will integrate design for streetscapes and public realm with a review of the density and built form on the island, building on years of planning to realize this new neighbourhood.

“Tri-government investment unlocked the potential of the Port Lands, allowing us to create a brand new island,” says Chris Glaisek, chief planning and design officer at Waterfront Toronto. “Now, renewed investment in waterfront revitalization means this new island is ready to launch. By integrating design for streets and public realm with a review of built form on the island, this team can build on the planning done by the City of Toronto, Waterfront Toronto and CreateTO to deliver as much new housing as possible, while building a truly world-class neighbourhood.” waterfrontoronto.ca

Stantec wins competition to rebuild State Tax University of Ukraine

Stantec has been selected as the winner of an international competition to redesign the State Tax University, which was partially destroyed in the early phases of the regional conflict.

Located in Irpin, 20 kilometres from Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv, the university prepares students for degrees in public finance, law, and accounting and is the only Ukrainian university chartered by the Ministry of Finance.

The STU International Architectural Competition was sponsored by the US-based nonprofit Center for Innovation, in partnership with the State Tax University (STU) of Ukraine, the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, and Ukrainian NGO “Dobrobat,” a volunteer construction organization that assists with the restoration of housing and social infrastructure.

The international competition received 49 entries from 18 countries and was juried by Ukrainian, European, and American architects seeking entries that achieved broad ranging goals, including sustainability, equity, and accessibility. stantec.com

The Ordre des architectes du Québec (OAQ) has announced the winners of its 2025 Awards of Excellence in Architecture. A total of eleven projects were recognized at a gala hosted by Jean-René Dufort at Espace St-Denis in Montreal.

The Grand Prix d’excellence en architecture was awarded to the restoration of Montreal City Hall, a major project led by Beaupré

ABOVE Coop Milieu de l’île, designed by Pivot: Coopérative d’architecture, was the winner of the People’s Choice Award in the OAQ Awards of Excellence program.

Michaud et Associés, Architectes, and MU Architecture. The People’s Choice Award was presented to the Coop Milieu de l’île, designed by Pivot: Coopérative d’architecture.

Awards of Excellence were also given to the following projects: Habitat Sélénite by _naturehumaine, École secondaire du Bosquet by ABCP | Menkès Shooner Dagenais LeTourneux | Bilodeau Baril Leeming Architectes, Bibliothèque Gabrielle-Roy by Saucier + Perrotte Architectes and GLCRM Architectes, Maison A by Atelier Pierre Thibault, Nouvel Hôtel de Ville de La Pêche by BGLA Architecture et Design Urbain, École du Zénith by Pelletier de Fontenay + Leclerc, Le Paquebot by_naturehumaine, Coopérative funéraire la Seigneurie by ultralocal architectes, and Site d’observation des bélugas Putep’t-awt by atelier5 + mainstudio.

“The projects we evaluated this year were truly remarkable in their richness and diversity. The jury found in them everything that makes Quebec architecture so strong and unique: rigor, attention to detail, and respect for the context and built heritage. All [of the winning projects], in their own way, highlighted the powerful impact of built quality on our living environments,” said Gabrielle Nadeau of Copenhagenbased COBE , chair of the jury. The jury also included architects Marianne Charbonneau of Agence Spatiale, Maxime-Alexis Frappier of ACDF, and Guillaume Martel-Trudel of Provencher_Roy. oaq.com

The Canada Council has announced the 2025 winners of its Prix de Rome and Ronald J. Thom Awards.

This year’s winner of the Prix de Rome – Professional is Vancouverbased D’Arcy Jones Architects (DJA). DJA’s work focuses on arts, residential and commercial projects. The prize supports the recipient in travelling abroad to develop their creative practice, and in strengthening their international position.

The winner of the Prix de Rome in Architecture – Emerging Practitioners is Daniel Wong, currently an intern architect at AAmp Studio in Toronto. The prize enables Wong to carry out an internship at an international architectural firm.

The Ronald J. Thom Award for Early Design Achievement was awarded to Toronto-based Odami, led by Arancha González Bernardo and Michael Fohring. canadacouncil.ca

New documents reinforce that Ontario Science Centre closure was not supported by engineers

New documents, obtained by Canadian Architect through a freedom of information request, appear to indicate that Rimkus the structural engineers hired to assess the Ontario Science Centre’s roof before the building’s closure did not support closing the Centre for public safety reasons.

The draft versions of the report instead recommend routine maintenance and a continuation of regular scheduled roof replacements over the course of the coming 20 years.

When read in conjunction with correspondence preceding the closure obtained by Global News, it seems likely that the engineers were pressured by the government to produce a report that would support the shuttering of the Ontario Science Centre. However, such a recommendation was not supported by their research and expertise.

Canadian Architect obtained draft versions of parts of the Rimkus report from March, April, and May of 2024. The report, whose final version is dated June 18, 2024, was commissioned to assess the condition of the Science Centre’s reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) roof panels, an outdated form of construction that can pose problems over time if not properly maintained. The report was based on on-site investigations conducted by Rimkus from December 2023 to March 2024.

tion to address all 2024 RAAC panel repair (amber risk) locations as a single project. As such, it is our opinion that the most cost effective strategy would be a consistent repair approach. Panel replacement rather than reinforcement is feasible at all areas, and presented in Table 7.”

The government seems to have pushed the engineers to go further, asking how the RAAC risk could be entirely eliminated. The May version adds the sentences: “It is recommended that RAAC panels should be replaced at the time of the next scheduled roof replacement, to completely eliminate the RAAC panel risk. Recommended timelines for complete roof assembly and RAAC panel (where applicable) replacements, and budgetary costs, by roof area are shown in Table 8.”

In the March, April, and May versions of the report, there is no provision for declining to do the repairs simply because roof repairs are a relatively routine, straightforward undertaking. RAAC panels at the Science Centre had been routinely replaced in the past. At the time of the inspection, a half dozen panels were identified as being in critical condition, and were already being replaced while the report was completed. A building permit was in progress to repair a section of the roof over the rainforest room. The cost of the immediate repairs needed would amount to around $500,000 or just over $7 million, if coupled with replacing, repairing, and maintaining larger sections of the Science Centre’s roofs that year.

And yet, the language apparently wasn’t strong enough for the Ontario government, whose communications staffers aimed to justify the closure of the entire facility as a public safety issue. For the final version of the report, government officials seem to have pressed the engineers to answer the question: what if we just don’t do the repairs? Wouldn’t the only totally safe option, in that case, be to close the building?

In a key section on RAAC Panel Recommendations, the March and April versions of the report clearly recommend to proceed with repairs to a set of panels identified as “high risk” less than 2.5% of the Science Centre’s roofs over the summer. It reads: “It is Rimkus’ recommenda25_007007_Canadian_Architect_AUG_CN

11:14

Protect your precious cargo! From peanuts to padding, Uline has hundreds of cushioning items to fill your void. Order by 6 PM for same day shipping. Best service and selection –experience the difference. Call 1-800-295-5510 or visit uline.ca

As a result, the final version of the report included the following passage: “Where replacement or reinforcement cannot be completed within the recommended time frame, then one of the following supplemental risk mitigation options is recommended and should be implemented in conjunction with the snow/load monitoring program:

Option 1: Restricted access or full closure to prevent any persons from walking in areas where high risk panels are present.

Option 2: Installation of temporary shoring (reinforcement) supporting the underside of RAAC panels.

Options 3: If shoring is not possible, installation of horizontal hoarding near the underside of hard ceiling levels, or other building interferences (sprinkler mains/process piping etc.)

The above three recommended options are listed in order of preference, with option 1 completing [sic] eliminating the risk to public or staff.”

As I have written before, while a quick reading of this passage may seem to suggest “full closure” of the Science Centre, a closer look shows that access would only need to be restricted at the areas “where high risk panels are present.” The high-risk panels represent a miniscule portion of the Science Centre’s roof, almost entirely in non-exhibition areas.

Text messages between Infrastructure Ontario CEO Michael Lindsay and the agency’s top communications staffer, from the run-up to the closure announcement, suggest that the agency was working closely with Rimkus and pressing executives to tailor its language before the report was submitted. “The executives at Rimkus look like survivors of the apocalypse. [laugh/cry emoji],” one of the texts reads. The presence of a typo in the report’s added section also suggests a rushed addition.

When the final report was sent, a member of Rimkus’s team seems to have also referenced conversations that took place between the two

parties. “Please refer to revised final summary report (R2) attached, with updated notes/paragraphs, as discussed,” they wrote on June 18.

While some back-and-forth between consultants and public clients is expected, it is unusual that this contact would be with the Ministry’s top brass particularly for a routine, technical report. Also notable is that while the Rimkus report released to the public by Infrastructure Ontario was signed by the engineers, it was not stamped an indication that the engineers may not have felt entirely comfortable with how the report landed, and were unwilling to be professionally liable for it.

In an email to top Ministry of Infrastructure and Infrastructure Ontario officials after the closure announcement, an Ontario Ministry director of communications shares a few questions that may arise. One is: “Q: Is this [closure] just a convenient excuse to move [the Ontario Science Centre] to Ont Place?” He suggests the reply: “This is a health and safety issue. Full stop.”

But for the engineers that actually inspected the roof, closure should never have been on the table: the roof issue could and should have been addressed with routine repairs.

Massive parking garage planned at Ontario Place; no decision on temporary Ontario Science Centre location

Ontario has not made any decisions on a temporary science centre while a new one is being built at Ontario Place, the infrastructure minister said on June 24, despite previously indicating one would be operating by Jan. 1, 2026. The future of two science centre pop-up exhibits in Toronto has also not been decided, said Infrastructure Minister Kinga Surma.

The province abruptly closed the science centre a year ago, saying the roof needed urgent repairs a claim workers and critics do not agree with. Soon after the closure, the government issued a request for proposals for a temporary location to operate until the Ontario Place site opens. It said it was working “expeditiously” to find an interim site and wanted it to open no later than Jan. 1, 2026.

But now, Surma says the science centre is “looking at what programming will look like” and no decisions have been made on the pop-ups or a more temporary science centre site in the meantime.

A new permanent location for the Ontario Science Centre is expected to open at Ontario Place in 2029, according to the Province. The design is currently in a P3 process, with WZMH providing PDC services and three teams shortlisted, including architectural firms Hariri Pontarini with Snøhetta, Quadrangle with Belvedere Architecture, and Cumulus Architects with Daoust Lestage Lizotte Stecker.

Surma’s comments came at a press conference where Premier Doug Ford unveiled final designs for the revamped Ontario Place, including a public realm designed by LANDinc and an eight-acre Therme spa and waterpark designed by Diamond Schmitt.

Ontario Place will include a five-storey, 3,500-spot parking garage that Ford says will cost taxpayers $400 million, but will have a great return on investment from parking fees. “We are going to see revenues at minimum of $60 million (annually),” he said. The government issued a Request for Proposals for the design and construction of the parking structure following the announcement.

According to Infrastructure Ontario’s own analysis of parking options, included in the Auditor General’s 2024 report, a 1,812-spot aboveground parking structure at Exhibition Place one of Infrastructure Ontario’s recommended options at that time would cost $400 million to construct, and would take 35 years to break even. This suggests that a parking garage with double that capacity could be considerably more expensive to build.

Ford also said the large parking garage, which is approximately 300 metres in length, “will be blended into the surrounding area with a landscape berm.” A one-storey berm is shown in renderings released by the Province, with the bulk of the building above. Ford added: “You’ll barely even see a parking lot. We’ll have stuff like, maybe, a fountain.”

In an interview on CBC ’s Here and Now, Globe and Mail architecture critic Alex Bozikovic commented that the proposed parking garage is, by his calculations, 80% of the size of Toronto’s Eaton’s Centre, and that it will be “very, very” visible. Its positioning on the waterfront obscures the existing entrance to Trillium Park and creates a “wall” between the city and planned public areas on Ontario Place’s East Island.

The site plan released by the Province shows a parking structure that will be about four times the volume of the proposed new Ontario Science Centre pavilion.

Earlier Provincial plans had envisioned sinking the parking underground or moving it to Exhibition Place, in order to preserve connections and access between the city and its waterfront.

The Province has passed legislation that removes the need for municipal permitting on work at Ontario Place, as well as removing the development from the Environmental Bill of Rights. This means that the placement, size, and design of the proposed parking structure will be exempt from standard zoning regulations and approvals processes. While infrastructural work and construction activities affecting the environment normally need to be reported to the public and opened to public commentary, work at Ontario Place has been legally exempted from this requirement as well.

–Elsa Lam, with files from The Canadian Press

New York-based FXCollaborative is joining forces with Montreal-headquartered architecture and design firm Lemay. “We are thrilled to welcome FXCollaborative into the Lemay collective,” said Louis T. Lemay, president of Lemay. “This relationship aligns with our vision of strategic growth and design excellence. FXC ollaborative’s remarkable portfolio and design philosophy complement our own, and together, we will create transformative and sustainable projects that positively impact communities across North America and beyond.”

Both firms will continue to operate under their existing leadership and brand identities.

lemay.com

Credit where it’s due

I read with great interest Adele Weder’s article on Bing Thom’s Butterfly (CA, April 2025) and her insightful critique of its architecture. I say Bing Thom’s Butterfly because it was designed when the firm was Bing Thom Architects and Bing was still alive. Venelin Kokalov certainly had a major role in giving it form, but Bing contributed the big ideas. I must say, I am a little disappointed that Bing was not given more credit. I was the original architect that rezoned the site with the church to allow the eventual development, so I am a little more familiar with the history of this project.

–James K.M. Cheng

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news

ACO. we care for water

Suitable for heavy duty areas

May be used on waterproofed terrasses

2026 RAIC Conference on Architecture

Save the date for the 2026 RAIC Conference on Architecture, taking place at the Sheraton Vancouver Wall Centre from May 5-8. Registration opens in January 2026. Details will be posted here: conference.raic.org

Notez bien la date de la Conférence sur l’architecture de l’IRAC 2026

Notez bien la date de la Conférence sur l’architecture de l’IRAC 2026, au Sheraton Vancouver Wall Centre, du 5 au 8 mai. L’inscription ouvrira en janvier 2026. Les détails seront affichés ici : conference.raic.org/fr/

2026 RAIC Awards Submissions

Want recognition for a project, career or an emerging talent? Submit an entry this fall for the prestigious RAIC Awards, which include our annual awards, Governor General Medals in Architecture, and the National Urban Design Awards. raic.org

Candidatures aux Prix de l’IRAC 2026

Vous aimeriez qu’un projet, une carrière ou un talent émergent soit récompensé? Présentez une candidature cet automne aux prestigieux Prix de l’IRAC, qui comprennent nos prix annuels, les Médailles du gouverneur général en architecture et les Prix nationaux de design urbain. raic.org/fr

Have you checked out our live courses happening this fall? Learn from seasoned experts at our live and hybrid courses tailored to architects: Human Resource Essentials for Architects, Financial Management for Architects, and Project Management for Architects. raic.org/foundations

Obtenez vos heures de formation continue cet automne

Avez-vous consulté notre offre de cours en direct pour cet automne? Apprenez auprès d’experts chevronnés dans le cadre de nos cours en direct et en format hybride conçus pour les architectes : les Essentiels des ressources humaines pour les architectes, Gestion financière pour les architectes et Gestion de projets pour les architectes. raic.org/fr/bases

The RAIC’s Community Survey is open through September 15, 2025. tinyurl. com/8d9ds87x

Le sondage de l’IRAC est ouverte jusqu’au 15 septembre 2025. tinyurl. com/8d9ds87x

Charting a New Path Forward for the RAIC Tracer une nouvelle voie

Giovanna Boniface Chief Commercial Officer Chef de la direction commerciale

This month, we invite you to shape the future of the RAIC by completing our Community Survey, now open through September 15. This is not an ordinary survey; this forms a critical part of our 2025-2027 Strategic Plan, which aims to chart a new path forward for the RAIC. Your insights will help redesign our membership model and guide future programs and services. It takes under five minutes and you could win day passes or an All-Access pass to the RAIC 2026 Conference on Architecture.

Ce mois-ci, nous vous invitons à façonner l’avenir de l’IRAC en participant à notre Sondage auprès de la communauté, ouvert jusqu’au 15 septembre. Ce sondage n’est pas ordinaire, car il est un élément essentiel de notre Plan stratégique 2025-2027 qui vise à tracer une nouvelle voie pour l’IRAC. Vos réponses nous aideront à redéfinir notre modèle d’adhésion et à orienter nos prochains programmes et services. Il vous faudra moins de cinq minutes pour y répondre et vous pourriez gagner un laissezpasser d’une journée ou un laissez-passer complet pour la Conférence sur l’architecture de l’IRAC 2026.

The RAIC is the leading voice for excellence in the built environment in Canada, demonstrating how design enhances the quality of life, while addressing important issues of society through responsible architecture. www.raic.org

L’IRAC est le principal porte-parole en faveur de l’excellence du cadre bâti au Canada. Il démontre comment la conception améliore la qualité de vie tout en tenant compte d’importants enjeux sociétaux par la voie d’une architecture responsable. www.raic.org/fr

This issue also highlights key developments across our community: the launch of the RAIC Climate Action Plan, a leadership update from the Truth and Reconciliation Task Force, and an insightful article on equity in architectural practice by Graeme Bristol.

We’re in a moment of transformation, and your voice is vital. Thank you for reading and for helping us build a more inclusive, responsive, and forward-looking RAIC.

Nous vous présentons également des nouvelles importantes au sein de notre communauté : le lancement du Plan d’action climatique de l’IRAC, un compte rendu sur la présidence du Groupe de travail sur la vérité et la réconciliation, ainsi qu’un article fort intéressant de Graeme Bristol sur l’équité dans la pratique de l’architecture.

Nous sommes à un moment de transformation et votre avis est essentiel. Merci de nous lire et de nous aider à bâtir un IRAC plus inclusif, sensible aux besoins et tourné vers l’avenir.

Mona Lemoine FRAIC

Joanne Perdue FRAIC

Giovanna Boniface Chief Commercial Officer Chef de la direction commerciale

On June 5, as the world marked Environment Day, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada released a groundbreaking strategy that challenges the architectural community to take a leadership role in the global climate movement. The Climate Action Plan –A Framework for Engagement and Enablement offers a vision for how Canadian architects can mobilize their expertise, creativity, and influence to address the interconnected crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

This is not just a plan—it’s a call to redefine the purpose and practice of architecture in an era of escalating planetary risk. The CAP recognizes that built environments are both a source of emissions and a platform for profound positive change. In response, the RAIC sets out a bold agenda to support the transition toward regenerative design and climateresponsive practice across the profession.

Nationally

The Climate Action Plan draws on an extensive national dialogue involving over 800 voices—practitioners, educators, Indigenous knowledge holders, policy experts, and youth. This inclusive process has resulted in a living framework grounded in scientific

ing architects are equipped and enabled to lead within a fast-evolving regulatory and climate context.

3. Building Stronger Alliances Across Sectors

Addressing climate change cannot happen in silos. The CAP commits to fostering crosssector collaboration and shared leadership. A national roundtable will bring together stakeholders from across the construction and design ecosystem, encouraging integrative solutions informed by regional needs and global best practices. The RAIC will also expand its knowledge-sharing infrastructure to amplify innovation and collective learning.

4.

Haikou Meishe River Restoration, Haikou, China, by Turenscape, recipient of the 2025 RAIC International Prize.

consensus and Indigenous worldviews, aligning with Canada’s commitments under the Paris Agreement and the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Structured around four central priorities, the CAP aims to integrate climate action at every level of architectural practice—within studios, communities, policies, and pedagogy.

1. Transforming Practice for Regenerative Outcomes

The first priority focuses on reshaping how architecture is practiced. It moves beyond conventional sustainability and introduces regenerative design principles that restore ecological systems and promote health equity. The RAIC will release tools, case studies, and technical resources to support firms of all sizes in embedding low-carbon, circular, and adaptive strategies into their work. A key part of this shift includes centering youth and emerging professionals in the process of change.

2. Elevating the Role of Architects in Advocacy

Architects are often underrepresented in policy spaces where the future of the built environment is decided. The RAIC seeks to change that by strengthening the voice of the profession at local, national, and global levels. The Plan advocates for policy incentives, differentiated insurance mechanisms for resilient buildings, and mandatory climate education as part of licensure—ensur-

Education is both a pathway and a lever for transformation. The RAIC will expand its continuing education offerings to include specialized microcredentials in regenerative design and climate-responsive development. Efforts will be made to uplift Indigenous knowledge systems through partnerships with the RAIC Indigenous Task Force and to create mentorship programs for students and recent graduates. In addition, the plan prioritizes public education—so that clients, governments, and communities better understand the role architecture plays in achieving climate goals.

Climate change impacts are not felt equally. The CAP explicitly acknowledges the disproportionate harm faced by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples and equity-deserving communities. It centres reconciliation and intergenerational justice as non-negotiable principles for climate leadership in architecture. Through “Two-Eyed Seeing,” the RAIC seeks to bridge Indigenous and Western knowledge systems to enrich how we understand land, place, and design.

The built environment sector is responsible for a significant portion of emissions and biodiversity impacts, but it also holds some of the greatest opportunities for transformation. As the RAIC notes, “The choices we make now will shape the future of life on Earth.” The Plan offers more than technical solutions—it calls on architects to embrace their civic, ethical, and cultural roles in addressing today’s most pressing challenges.

With annual reporting, stakeholder engagement, and clear science-based targets, the CAP is designed to be actionable, accountable, and adaptable. The RAIC recognizes that climate action is an ongoing journey—

Restauration de la rivière Haikou Meishe, Haikou, Chine, par Turenscape, lauréat du Prix international de l’IRAC 2025

and invites the entire architectural community to walk that path together.

The RAIC Climate Action Plan is an invitation to recommit to design as a public good. It is a framework for working differently, thinking holistically, and designing with care. The message is simple but urgent: the climate crisis demands nothing less than transformative change—and architects must lead.

Learn more and access the full Climate Action Plan at raic.org/climate-action

Le 5 juin dernier, Journée mondiale de l’environnement, l’Institut royal d’architecture du Canada (IRAC) a publié une stratégie d’avantgarde qui met la communauté architecturale au défi de jouer un rôle de premier plan dans le mouvement climatique mondial. Le Plan d’action climatique – Un cadre pour l’engagement et l’habilitation présente une vision de ce que les architectes peuvent réaliser en mobilisant leur expertise, leur créativité et leur influence pour faire face aux crises interdépendantes du changement climatique et de la perte de biodiversité.

Ce plan n’est pas seulement un plan. Il est un appel à redéfinir l’objectif et la pratique de l’architecture à une époque où les risques planétaires s’intensifient. Le Plan d’action reconnaît que les environnements bâtis sont à la fois une source d’émissions et une plateforme pour une véritable transformation. Cette reconnaissance amène l’IRAC à établir un programme audacieux pour favoriser la transition vers une conception régénérative et des pratiques adaptées au climat dans l’ensemble de la profession.

Une stratégie élaborée à l’échelle de la profession, à la grandeur du pays Le Plan d’action climatique s’appuie sur un vaste dialogue national auquel ont participé plus de 800 personnes, notamment des praticiens, des éducateurs, des détenteurs de savoirs autochtones, des experts des politiques et des jeunes. Ce processus inclusif s’est traduit par un cadre vivant fondé sur un consensus scientifique et sur les visions du monde autochtones, en phase avec les engagements pris par le Canada en signant l’Accord de Paris et en adoptant le Cadre mondial de la biodiversité.

Le Plan d’action s’articule autour de quatre priorités et vise à intégrer l’action climatique à tous les niveaux de la pratique architecturale – dans les firmes, les collectivités, les orientations stratégiques et la formation.

1. Transformer la pratique pour des résultats régénératifs

La première de ces priorités consiste à revoir comment s’exerce l’architecture, à aller au-delà de la durabilité conventionnelle et à introduire les principes de la conception régénérative qui restaure les systèmes écologiques et promeut l’équité en santé. L’IRAC offrira des outils, des études de cas et des ressources techniques pour aider les firmes de toutes dimensions à intégrer des stratégies sobres en carbone, circulaires et adaptatives à leurs projets. Un volet clé de ce virage est de placer les jeunes et les professionnels de la relève au centre du processus de changement.

2. Renforcer le rôle des architectes dans la défense des intérêts

Les architectes sont souvent sous-représentés dans les sphères politiques où se décide l’avenir de l’environnement bâti. L’IRAC cherche à changer cette situation en renforçant la voix de la profession aux niveaux local, national et mondial. Le Plan d’action plaide en faveur de mesures incitatives, de mécanismes d’assurance différenciés pour les bâtiments résilients et d’une formation obligatoire sur le climat comme condition de délivrance de permis, afin que les architectes aient les outils nécessaires et qu’ils soient habilités à jouer un rôle de premier plan dans un contexte réglementaire et climatique en évolution rapide.

3. Renforcer les alliances intersectorielles La lutte contre le changement climatique ne peut se faire isolément. Le Plan d’action s’engage à favoriser la collaboration intersectorielle et le partage du leadership. Une table ronde réunira les parties prenantes de l’ensemble de l’écosystème de la construction et de la conception afin d’encourager l’adoption de solutions intégratives guidées par les besoins régionaux et les meilleures pratiques mondiales. L’IRAC élargira la portée de son infrastructure de partage des connaissances afin de stimuler l’innovation et l’apprentissage collectif.

4. Investir dans l’éducation et la mobilisation des connaissances L’éducation est à la fois une voie et un levier de transformation. L’IRAC élargira son offre de formation continue pour offrir un programme de micro-certification en conception régénérative et développement sensible au climat. Il s’efforcera également de valoriser les systèmes de savoirs autochtones dans le cadre de partenariats avec son Groupe de travail autochtone et soutiendra la création de programmes de mentorat à l’intention des étudiants et des

diplômés récents. De plus, le Plan d’action priorise la sensibilisation du public afin que les clients, les pouvoirs publics et les collectivités puissent mieux comprendre le rôle de l’architecture dans l’atteinte des objectifs climatiques.

Fonder l’action sur la réconciliation et l’équité

Les impacts du changement climatique ne sont pas les mêmes pour tous. Le Plan d’action reconnaît explicitement les préjudices disproportionnés subis par les Premières Nations, les Inuits et les Métis ainsi que par les communautés en quête d’équité. Il place la réconciliation et la justice intergénérationnelle au cœur des principes non négociables du leadership climatique en architecture. En intégrant la « vision à deux yeux », l’IRAC cherche à établir des ponts entre les systèmes des savoirs autochtones et occidentaux afin d’enrichir notre compréhension de la terre, du lieu et du design.

Pourquoi ce plan est-il important

Le secteur de l’environnement bâti est responsable d’une part importante des émissions et des impacts sur la biodiversité, mais il recèle également les plus grandes occasions de transformation. Comme le souligne l’IRAC, « les choix que nous faisons aujourd’hui détermineront l’avenir de la vie sur Terre ». Le Plan d’action offre plus que des solutions techniques. Il invite les architectes à assumer leurs rôles civiques, éthiques et culturels dans la résolution des défis les plus pressants d’aujourd’hui.

Avec ses exigences de déclarations annuelles, la participation des parties prenantes et les cibles claires fondées sur la science, le Plan d’action est conçu pour être réalisable, responsable et adaptable.

L’IRAC reconnaît que l’action climatique est un processus continu et il invite toute la communauté architecturale à s’engager dans cette voie.

Un appel à la communauté du design

Le Plan d’action climatique de l’IRAC est une invitation à réaffirmer l’engagement envers le design en tant que bien public. Il est un cadre qui nous encourage à travailler différemment, à penser de manière holistique et à concevoir avec soin. Le message est simple, mais urgent : la crise climatique n’exige rien de moins qu’un changement transformateur et les architectes doivent montrer la voie.

Pour en savoir plus et consulter le Plan d’action climatique : raic.org/fr/raic/plan-daction-climatique

Downtown Toronto residents lobbied fiercely against the Spadina Expressway plans in the late 1960s.

Les résidents du centre-ville ont exercé une forte pression contre les projets de l’autoroute Spadina à la fin des années 1960.

Graeme Bristol

Executive Director, Centre for Architecture and Human Rights (CAHR)

Directeur général, Centre for Architecture and Human Rights (CAHR)

Until the end of November, the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) is exhibiting Records of Protest, a compelling exploration of how architects have engaged with the crises of their time. Drawing from the CCA’s collection, the exhibit surfaces narratives often neglected in mainstream professional discourse. These are narratives of resistance, justice, and alternative practice.

As someone whose life in architecture benefited from this history, I’m grateful to the CCA and to curators Lisa Belabed and Auden Young Tura for assembling this important record. It is especially meaningful for the next generation of architects, who will be called upon to navigate everdeepening inequities and injustices. Recognition of this work is not merely retrospective; it affirms a lineage of architects, planners, and engineers still operating at the profession’s margins.

It is critical, especially for students, to understand a few contextual truths:

• There are meaningful alternatives to traditional architectural practice.

• These alternatives are frequently marginalized, omitted from curricula, and sidelined by representative institutions.

• The crises we face, including social, economic, and ecological, are escalating in urgency. They will not be solved by “business as usual.”

• The work of protest and progress continues and is not confined to history books or gallery walls.

This is not simply a “record of protest.” It is a record of advocacy for justice, for equity, and for a better future.

The spirit of this movement gained momentum in the 1960s, alongside the civil rights movement, most famously symbolized by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech during the 1963 March on Washington. Soon followed the free speech movement at UC Berkeley, catalyzed by Mario Savio and culminating in the People’s Park protests of 1969. These were mirrored

globally by the anti-war movement, with voices like Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and Phil Ochs scoring the soundtrack to mass civic engagement.

But how does this relate to architecture? At the American Institute of Architects’ 1968 convention, Whitney Young Jr., then head of the Urban League, addressed the profession’s role in social unrest across Detroit, Newark, Watts, and other cities. His words were direct and scathing: “You are most distinguished by your thunderous silence and your complete irrelevance.” That critique landed heavily on a profession often seen as disconnected from the people it serves.

In contrast, youth around the world were taking to the streets, exploring how architecture could be reimagined to serve justice and equity. Architect Max Bond Jr. channelled this energy into the Architects Renewal Committee of Harlem, founded in 1963. That movement continues today through Community Design Centers across the United States, supported by the Association for Community Design. In the United Kingdom, similar efforts emerged as “Technical Aid” initiatives.

For many of us seeking alternative directions, inspiration came from other sources too. The first Habitat conference, hosted in Vancouver while I was still a student at the University of British Columbia, was a pivotal experience. It sparked interest in new paradigms of practice, further fuelled by two influential books: Freedom to Build by John F.C. Turner (1972) and Architecture for the Poor by Hassan Fathy (1969).

The passing of John F.C. Turner in 2023 prompted a global tribute, a moment of reflection and recommitment. During that memorial, Kirtee Shah asked a vital question: has Turner’s work meaningfully influenced today’s generation? The Records of Protest exhibit is part of the answer. But the more powerful response lies not in archives, but on the street.

Many of us are not content to be archived. The struggle continues in the work of organizations like:

• A rchitects, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), which

evolved into Arc-Peace International in 1989.

• Architecture Sans Frontières International (ASF), particularly ASF Québec, whose field work continues to inspire.

• Habitat International Coalition (HIC), born at the first Habitat Forum in 1976, and still advocating for housing rights and equitable urban development.

These are not relics of a bygone era. They are active movements addressing today’s challenges and continuing to respond to Whitney Young Jr.’s call for professional responsibility in defending human rights and social justice.

This is not only a history lesson. As the late Sam Mockbee urged, what we need now are “Citizen Architects.” These are professionals who design not just buildings, but better societies. The record of protest is ongoing, and it demands our attention, imagination, and action.

Le Centre Canadien d’architecture (CCA) présente jusqu’à la fin de novembre l’exposition Traces de contestation, qui explore les attitudes adoptées par les architectes dans le passé en réaction aux crises de leur temps. Issus de la collection du CCA, les objets sélectionnés mettent en lumière des récits souvent négligés dans le discours professionnel dominant. Ce sont des récits de résistance, de justice et de pratique alternative.

Ayant mené une carrière en architecture qui a bénéficié de cette histoire, je suis reconnaissant au CCA et aux conservatrices Lisa Belabed et Auden Young Tura d’avoir rassemblé ces documents importants. Cette exposition revêt un sens particulier pour la prochaine génération d’architectes, qui sera appelée à exercer dans un contexte où les inégalités et des injustices s’aggraveront. La reconnaissance de ce travail n’est pas seulement rétrospective; elle confirme l’existence d’une lignée d’architectes, d’urbanistes et d’ingénieurs qui continuent d’exercer à la marge de leur profession.

Il est essentiel, en particulier pour les étudiants, de comprendre quelques vérités contextuelles :

• l y a d’importantes alternatives à la pratique traditionnelle de l’architecture.

• Ces alternatives sont souvent marginalisées, absentes des programmes d’études et écartées par les institutions représentatives.

• Il devient de plus en plus urgent de s’attaquer aux crises auxquelles nous sommes confrontés, y compris les crises sociale, économique et écologique. Ces crises ne pourront être résolues si le statu quo est maintenu.

• Le travail de contestation et de progrès se poursuit et n’est pas confiné aux livres d’histoire et aux murs des musées.

Il ne s’agit pas d’une simple « question de contestation ». Il s’agit d’un plaidoyer en faveur de la justice, de l’équité et d’un avenir meilleur.

L’esprit de ce mouvement a pris de l’ampleur dans les années 1960, en parallèle avec le mouvement de lutte pour les droits civiques, dont le symbole le plus célèbre est le discours « I Have a Dream » prononcé par Martin Luther King Jr. lors de la marche sur Washington en 1963. Peu après, le mouvement pour la liberté d’expression a vu le jour à l’UC Berkeley, sous l’impulsion de Mario Savio, et a culminé avec les manifestations du People’s Park en 1969. Ces événements ont trouvé un écho dans le monde entier avec le mouvement antiguerre, et des personnalités comme Joan Baez, Bob Dylan et Phil Ochs ont été la trame sonore de la mobilisation citoyenne massive. Mais quel est le lien avec l’architecture?

Au congrès de 1968 de l’American Institute of Architects, Whitney Young Jr., alors à la tête de l’Urban League, a prononcé un discours sur le rôle de la profession par rapport à l’agitation sociale qui régnait à Détroit, à Newark, à Watts et dans bien d’autres villes. Dans son propos direct et cinglant, il a signifié aux architectes qu’ils se distinguaient par leur silence assourdissant et leur manque total de pertinence. Cette critique a durement touché une profession souvent perçue comme déconnectée des personnes qu’elle sert.

À l’opposé, des jeunes du monde entier descendaient dans les rues pour examiner comment l’architecture pouvait être repensée au service de la justice et de l’équité. L’architecte Max Bond Jr. a canalisé cette énergie en fondant l’Architects Renewal Committee of Harlem, en 1963. Ce mouvement existe encore aujourd’hui à travers les centres de conception communautaire répartis aux États-Unis, soutenus par l’Association for Community Design. Au Royaume-Uni, des initiatives similaires ont vu le jour sous le nom de « Technical Aid ».

Pour plusieurs d’entre nous qui cherchons d’autres voies, l’inspiration est également

venue d’ailleurs. La première conférence Habitat, tenue à Vancouver alors que j’étais encore étudiant à l’Université de la Colombie-Britannique, a été une expérience déterminante. Elle a éveillé mon intérêt pour de nouveaux paradigmes de pratique, un intérêt par la suite renforcé par la lecture de deux ouvrages influents : Freedom to Build, de John F. C. Turner (1972) et Architecture for the Poor de Hassan Fathy (1969).

Le décès de John F. C. Turner en 2023 a donné lieu à un hommage mondial, à un moment de réflexion et de réengagement. Lors de cette cérémonie commémorative, Kirtee Shah a posé une question essentielle : le travail de Turner a-t-il eu une influence significative sur la génération actuelle?

L’exposition « Traces de contestation » apporte une partie de la réponse. Mais la réponse la plus puissante ne se trouve pas dans les archives, mais sur le terrain.

Bon nombre d’entre nous ne se contentent pas de figurer dans les archives. La lutte se poursuit dans le travail de diverses organisations, notamment :

• Architects, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), qui est devenue Arc-Peace International en 1989.

• Architecture sans frontières international (ASF), et particulièrement ASF Québec, dont le travail sur le terrain continue d’inspirer.

• Habitat International Coalition (HIC), créée lors du premier Forum Habitat, en 1976, continue de plaider en faveur du droit au logement et d’un développement urbain équitable.

Ce ne sont pas des vestiges d’une époque révolue. Ce sont des mouvements actifs qui s’efforcent de relever les défis actuels et qui continuent de répondre à l’appel de Whitney Young Jr. en faveur de la responsabilité professionnelle dans la défense des droits de la personne et de la justice sociale.

Il ne s’agit pas seulement d’une leçon d’histoire. Comme le disait feu Sam Mockbee, ce dont nous avons besoin aujourd’hui, ce sont des « architectes citoyens », c’est-àdire des professionnels qui ne se limitent pas à concevoir des bâtiments, mais qui conçoivent aussi de meilleures sociétés. Les traces de contestation sont encore présentes et elles exigent notre attention, notre imagination et notre action.

l’avenir

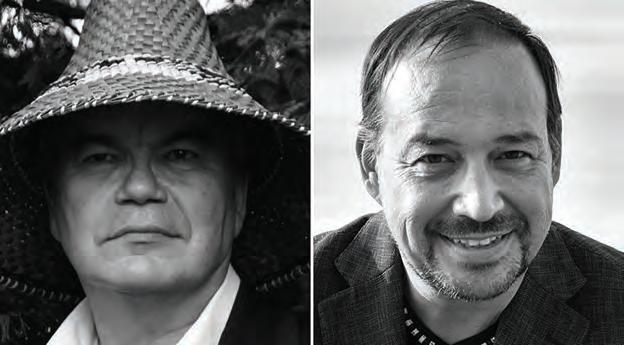

Since its formation in 2020, the RAIC Truth and Reconciliation Task Force (TRTF) has played a vital role in guiding the architectural profession toward meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Anchored in foundational frameworks like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC], 2015), the Reclaiming Power and Place: Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls [MMIWG], 2019), and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (United Nations [UN], 2007), the TRTF has worked to build sustainable, long-term change in the field of architecture across Canada.

This year marks a significant transition for the TRTF as we extend our heartfelt gratitude to outgoing co-chairs Alfred Waugh (Status Indian and part of Treaty 8), FRAIC, and Sim’oogit Ksi-Baxhlkw | Dr. Patrick Stewart (Nisga’a), PhD, FRAIC, whose vision, advocacy, and leadership helped lay the groundwork for cultural transformation within the profession.

Under their guidance, the TRTF helped the RAIC formally adopt UNDRIP in 2021 and launched educational initiatives to commemorate the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Their work emphasized the importance of Indigenous knowledge systems, cultural safety, and mentorship opportunities for Indigenous architects, interns and students.

“It has been an honour to serve as co-chair of the TRTF,” says Alfred Waugh. “Reconcili-

ation in architecture must be more than symbolic—it must shape how we design, plan, and teach. I am proud of what we’ve begun and excited to see the next generation carry this work forward.”

“Truth comes before reconciliation,” adds Dr. Patrick Stewart. “This Task Force has been a platform for sharing hard truths and advocating for systemic change. My hope is that the profession continues to move toward a place of respect, accountability, and real partnership with Indigenous Peoples.”

As we thank Alfred and Patrick for their service, we are proud to welcome Darian McKinney, MRAIC and Jennifer Cutbill, FRAIC, as the new co-chairs of the Truth and Reconciliation Task Force.

Darian McKinney, an Anishinaabe member of Swan Lake First Nation, brings a deep commitment to community-based design and Indigenous sovereignty in the built environment, while Jennifer Cutbill, a settler of mixed European descent, brings long-standing advocacy for eco-social justice, ethical regenerative practice, and commitment to systems transformation rooted in respect for Indigenous rights.

“I’m honoured to help carry this important work forward,” says Darian McKinney. “The TRTF is a space for listening, learning, and acting—and I look forward to building on the foundation set by Alfred and Patrick.”

“Reconciliation is an ongoing responsibility requiring deep work” says Jennifer Cutbill. “Our role is to support the architectural community in understanding and implementing UNDRIP—not just in principle, but in everyday practice. This means co-creating “Ethical Space” for Indigenous leadership and knowledge systems in all we do, building on the vital foundations Patrick and Alfred have established.”

The TRTF continues to call on all members of the profession—architects, interns, students, educators, and regulators—to adopt and implement UNDRIP in meaningful ways. With this leadership transition, the RAIC

reaffirms its commitment to reconciliation through action, accountability, and Indigenous-led change.

To learn more or get involved, visit raic.org/ truth-and-reconciliation-task-force.

Depuis sa création en 2020, le Groupe de travail sur la vérité et la réconciliation (GTVR) de l’IRAC joue un rôle essentiel pour guider la profession architecturale vers une réconciliation significative avec les peuples autochtones. S’appuyant sur des cadres fondamentaux, notamment le Rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation (Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada [CVR], 2015); Réclamer notre pouvoir et notre place : Rapport final de l’Enquête nationale sur les femmes et les filles autochtones disparues et assassinées (Enquête nationale sur les femmes et les filles autochtones disparues et assassinées [ENFFADA], 2019) et la Déclaration des Nations Unies sur les droits des peuples autochtones (DNUDPA) (Nations Unies [ONU], 2007), le GTVR s’efforce d’apporter des changements durables et à long terme dans le domaine de l’architecture à la grandeur du Canada.

Cette année marque une transition importante pour le GCVR, alors que nous exprimons notre sincère gratitude aux coprésidents sortants Alfred Waugh (Indien inscrit et membre du Traité n° 8), FRAIC, et Sim’oogit Ksi-Baxhlkw | Patrick Stewart (Nisga’a), Ph. D., FRAIC, dont la vision, le plaidoyer et le leadership ont contribué à jeter les bases d’une transformation culturelle au sein de la profession.

Sous leur direction, le GTVR a aidé l’IRAC à adopter officiellement la DNUDPA en 2021 et a lancé diverses initiatives de sensibilisation pour commémorer la Journée nationale de la vérité et de la réconciliation. Ils ont mis l’accent sur l’importance des systèmes de savoirs autochtones, de la sécurité culturelle et des possibilités de mentorat pour les architectes, les stagiaires et les étudiants autochtones.

« Ce fut un réel honneur de coprésider le Groupe de travail sur la vérité et la réconciliation », a déclaré Alfred Waugh. « La réconciliation en architecture doit être plus que symbolique – elle doit orienter nos façons de concevoir, de planifier et d’enseigner. Je suis fier de ce que nous avons commencé et je me réjouis de voir la prochaine génération prendre le relais. » « La vérité précède la réconciliation », a

ajouté Patrick Stewart, Ph. D. « Ce Groupe de travail a été une plateforme de partage des dures vérités et de plaidoyer en faveur d’un changement systémique. J’espère que la profession continuera d’évoluer vers le respect, la responsabilisation et un véritable partenariat avec les peuples autochtones. »

Tout en exprimant notre reconnaissance à Alfred et à Patrick, nous sommes heureux d’accueillir les nouveaux coprésidents, Darian McKinney, MRAIC, et Jennifer Cutbill, FRAIC.

Darian McKinney, un membre Anishinaabe de la Première Nation de Swan Lake, apporte son engagement profond envers la conception basée sur la communauté et la souveraineté autochtone dans l’environnement bâti, alors que Jennifer Cutbill, une colonisatrice d’ascendance européenne mixte, apporte son plaidoyer de longue date en faveur de la justice écosociale, des pratiques régénératives éthiques et d’une transformation des systèmes enracinée dans le respect des droits des Autochtones.

« Je suis honoré de contribuer à la poursuite de cet important travail », a déclaré Darian McKinney. « Ce Groupe de travail est un lieu d’écoute, d’apprentissage et d’action, et je me réjouis de pouvoir m’appuyer sur les bases établies par Alfred et Patrick. »

« La réconciliation est une responsabilité permanente qui nécessite un travail en profondeur », a ajouté Jennifer Cutbill. « Notre rôle consiste à aider la communauté architecturale à comprendre et à mettre en œuvre la DNUDPA, non seulement en théorie, mais aussi dans la pratique quotidienne. Cela suppose de cocréer un espace éthique [1] pour les systèmes de leadership et de savoirs autochtones dans toutes nos activités, en nous appuyant sur les fondements essentiels établis par Patrick et Alfred. »

Le Groupe de travail sur la vérité et la réconciliation continue d’inviter tous les membres de la profession – architectes, stagiaires, étudiants, enseignants ou organismes de réglementation – à adopter la DNUDPA et à la mettre en œuvre de manière significative. Cette transition à la présidence du Groupe de travail sur la vérité et la réconciliation permet à l’IRAC de réaffirmer son engagement envers la réconciliation par l’action, la responsabilisation et le changement mené par les Autochtones.

Pour en savoir plus ou pour vous impliquer, visitez raic.org/truth-and-reconciliationtask-force.

The International Architectural Roundtable at The Buildings Show 2025: Strategies for MixedUse Environments La Table ronde internationale d’architecture au The Buildings Show 2025 : Stratégies pour les environnements à usage mixte

The Rise of Mixed-Use Developments

As urban populations surge worldwide, mixed-use developments have emerged as powerful solutions to complex challenges. The Buildings Show’s 24th Annual International Architectural Roundtable returns on December 3, 2025, bringing together visionary architects to explore innovative strategies for creating integrated environments that combine various building types.

Shifting Industry Paradigms

“The industry is experiencing a fundamental shift in how spaces are conceptualized and utilized,” notes The Buildings Show director, Glen Reynolds. “Properties that can serve multiple purposes not only maximize efficiency but also create more vibrant, sustainable communities.” This evolution reflects broader societal changes: remote work blurring home and office boundaries, e-commerce transforming retail needs, and urban dwellers seeking comprehensive lifestyle solutions within walking distance.

Investment Opportunities in Convergence

For investors and developers, this convergence represents significant opportunity. Properties that successfully integrate multiple uses often demonstrate enhanced resilience during market fluctuations while attracting diverse tenant bases. As part of the Canadian Real Estate and Construction Week, The Buildings Show will highlight emerging financial models supporting these

hybrid developments and connect capital with innovative projects that balance economic viability with community needs.

While developers are increasingly capitalizing on the convergence of product types to achieve significant returns, architects face the challenge of designing cohesive and innovative mixed-use environments. This year’s roundtable features an exceptional panel of international experts at the forefront of mixed-use environments including Dimitra Tsachrelia of Steven Holl Architects, Michael Sørensen from Henning Larsen Architects, and David Pontarini of Hariri Pontarini Architects. Additional panellists will be announced closer to the event date, and the session will be moderated by renowned architectural critic and writer Adele Weder. Attendees can expect case studies of successful implementations and practical frameworks for addressing common mixed-use environment challenges.

Join the Conversation

Don’t miss this opportunity to engage with leading voices shaping our built environment. RAIC members members receive complimentary attendance to the roundtable and The Buildings Show expo hall. Attendees to The Buildings Show will gain practical insights through:

• Expert-delivered sessions and panel discussions

• Networking opportunities with industry pioneers

• Access to cutting-edge technology solutions enabling flexible space utilization

To register visit www.thebuildingsshow.com.

L’Essor des développements à usage mixte Alors que les populations urbaines augmentent dans le monde entier, les développements à usage mixte sont apparus comme des solutions puissantes face à des défis complexes. La 24e Table ronde internationale d’architecture annuelle du The Buildings Show retourne le 3 décembre 2025, réunissant des architectes visionnaires pour explorer des stratégies innovantes visant à créer des environnements intégrés qui combinent divers types de bâtiments.

Changement de paradigmes dans l’industrie “L’industrie connaît un changement fondamental dans la façon dont les espaces sont conceptualisés et utilisés,” note le directeur du The Buildings Show, Glen Reynolds. “Les propriétés qui peuvent servir à des fins multiples non seulement maximisent l’efficacité mais créent également des communautés plus dynamiques et durables.” Cette évolution reflète des changements sociétaux plus larges : le travail à distance brouillant les frontières entre domicile et bureau, le commerce électronique transformant les besoins de vente au détail, et les citadins recherchant des solutions de style de vie complètes à distance de marche.

Convergence des opportunités d’investissement

Pour les investisseurs et les promoteurs, cette convergence représente une opportunité significative. Les propriétés qui intègrent avec succès plusieurs usages démontrent souvent une résilience accrue pendant les fluctuations du marché tout en attirant des bases de locataires diversifiées. Dans le cadre de la Semaine canadienne de l’immobilier et de la construction, The Buildings Show mettra en lumière les modèles financiers émergents soutenant ces développements hybrides et connectera le capital avec des projets innovants qui équilibrent viabilité économique et besoins communautaires.

Expertise et innovation

Alors que les promoteurs capitalisent de plus en plus sur la convergence des types de produits pour obtenir des rendements significatifs, les architectes font face au défi de concevoir des environnements à usage mixte cohérents et innovants. Cette année, la table ronde présente un panel exceptionnel d’experts internationaux à l’avant-garde des environnements à usage mixte, notamment Dimitra Tsachrelia de Steven Holl Architects, Michael Sørensen de Henning Larsen Architects, et David Pontarini de Hariri Pontarini Architects. D’autres panélistes seront annoncés à l’approche de l’événement. Modérée par la célèbre critique d’architecture et écrivaine Adele Weder, les participants peuvent s’attendre à des études de cas de mises en œuvre réussies et des cadres pratiques pour aborder les défis courants des environnements à usage mixte.

Rejoignez la conversation

Ne manquez pas cette opportunité d’échanger avec des voix influentes qui façonnent notre environnement bâti. Les membres de l’IRAC bénéficient d’une entrée gratuite à la table ronde et au hall d’exposition du The Buildings Show. Les participants au The Buildings Show obtiendront des perspectives pratiques grâce à :

• Des séances animées par des experts et des discussions en panel

• Des opportunités de réseautage avec des pionniers de l’industrie

• L’accès à des solutions technologiques de pointe permettant une utilisation flexible de l’espace

Pour vous inscrire, visitez www.thebuildingsshow.com.

AFTER 15 YEARS IN THE MAKING, ST. LAWRENCE MARKET NORTH IS A MUCH-WELCOME PUBLIC HUB IN THE HEART OF DOWNTOWN TORONTO.

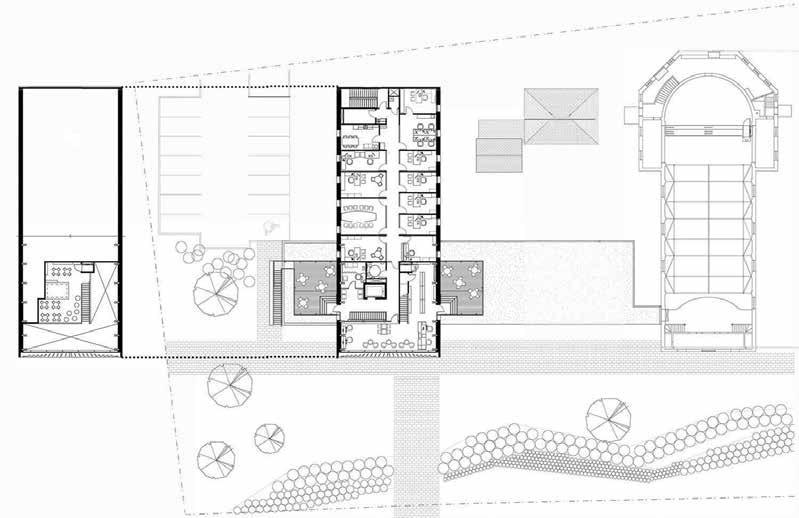

PROJECT St. Lawrence Market North Building

ARCHITECTS RSHP and Adamson Associates Architects

TEXT Pamela Young

PHOTOS Nic Lehoux

Richard Rogers often told the story of being in Paris near the Centre Pompidou, in the late 1970s. It was raining, and a woman offered him space under her umbrella as they stood gazing at the old city’s defiantly new, guts-on-the-outside art gallery. She asked him what he thought of it. “Stupidly, I said that I designed it,” the British architect recalled. “She hit me on the head with the umbrella.”

In May 2025, Toronto’s St. Lawrence Market North finally opened, fifteen long years after Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (now RSHP) and Adamson Associates Architects won the competition to design it.

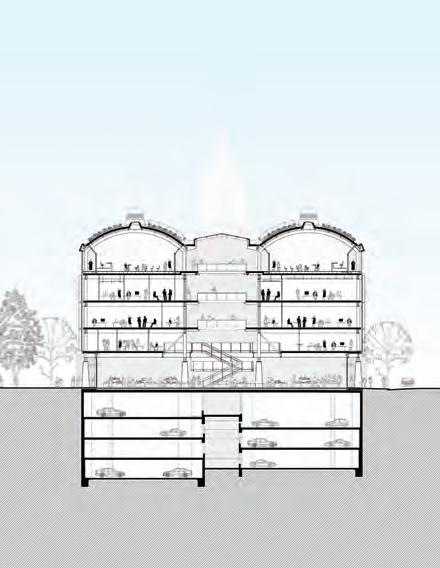

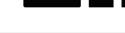

LEFT St. Lawrence Market North combines courtrooms, court services administrative space, and a market hall. The building’s central concourse creates an axial connection between the South Market Hall and the historic St. Lawrence Hall to the north.

RSHP ’s first building in Canada stacks two levels of public market, community space and Court Services wickets overtop of four underground parking levels, and caps the building with three floors housing courtrooms and administrative space for the City, some provincial functions, and Toronto Police Service.

No one is outraged by this building’s appearance. No one has decried it an insensitive addition to the St. Lawrence Market heritage district. But it has generated controversy, on more than an umbrella-whacking scale. Delayed by everything from an archaeological excavation to a global pandemic, a building that had a $76-million budget at its design competition stage now has a $128-million-plus pricetag. The project’s general contractors, Buttcon Ltd. and Atlas Corporation in joint venture, are suing the City for $83 million, alleging that they have not been fully paid for labour, materials, and other expenditures, and they’re seeking an additional $9.3 million, in part for Covid-generated cost escalations and changes. The lawsuit claims the updated contract price should be $203 million a doubling from the original contract.

Jiwan Thapar, CEO of JTE Claims Consultants, told the Toronto Star that even in an era of high construction inflation and related litigation, it’s “very abnormal” for a contractor to make a claim this large.

Despite St. Lawrence Market North’s messy origin story, in pure design terms, it’s a building that gets a lot right even if it took some value engineering hits during its long realization.

Since 1803, one market after another has occupied the northwest corner of what is now Front Street and Jarvis Street. At the midpoint of the 19th century, on the north end of the block, raw, young Toronto erected its first truly cosmopolitan building: St. Lawrence Hall. Palladian, richly ornamented, and topped with a copper-domed town-clock cupola, St. Lawrence Hall hosted balls and lectures, and was directly connected to the open-air market behind it, with its nearby docks. Around 1900, St. Lawrence Market South was constructed on the southwest King and Jarvis corner. A vast, capable brick barn, to this day it teems with sellers and buyers of comestibles and souvenirs, six days a week.

The North Market’s immediate predecessor was a bunkerish, singlestorey 1960s building, built on the cheap on the half-block between St. Lawrence Hall and St. Lawrence Market South, severing views between the two. The new building, in contrast, handsomely connects these heritage landmarks. On all four levels above the market’s open expanse, a skylit atrium cleaves the building into equal, parallel oblong volumes. The atrium aligns with the cupola of St. Lawrence Hall, which pops into view as you pass through the Front Street main entry, facing north. Facing south, you get magnificent views of the older market a structure RSHP Senior Director Ivan Harbour calls “the lovely shed.” Glass-walled bridges supported by orange-painted steel beams span the North building’s atrium on all levels above the market floor, offering additional heritage vistas. In the warmer months, roll-up glass doors on the side walls phys-

ABOVE The market area is maximized to create a flexible, permeable space with roll-up glass doors on the ground floor that, when opened, allow the market to spill out into the adjacent street to the east and plaza to the west.

ically connect the market level to Jarvis Street to the east and to Market Lane Park to the west. (The latter is a scruffy promenade soon to get its long-promised, much-needed redesign.) The building incorporates a geothermal system, and its partial reliance on natural ventilation will reduce overall operational energy consumption.

In functional terms, in the words of City of Toronto Senior Project Manager Alexander Lackovic, who joined the project team in 2017, the North Market still “needs to grow into itself.” On every farmers-market Saturday, it’s already a buzzing hive. But the Sunday antiques market hasn’t as yet returned to the site, and on weekdays the market areas are locked up and vacant. A leasable retail space–likely a future café–at the northwest corner is still merely shelled in, as is yet-to-be-programmed community space on the west side of Level Two. (That floor’s east side houses the Toronto Court Services counter.) And although a Level Two bridge connecting St. Lawrence Market North to the rear of St. Lawrence Hall will eventually enhance the event-venue viability of both buildings, the 1850 structure needs renovations prior to the link’s activation.

Planned historical interpretation is still largely pending: an 1831 drain uncovered during the archaeological excavation that followed the 1960s market’s demolition is showcased under a glass-topped plinth (designed to double, handily, as a speaker’s podium), and metal insets in the market’s polished concrete floor trace former sewer lines, but interpretive panels and artefact displays aren’t yet installed.

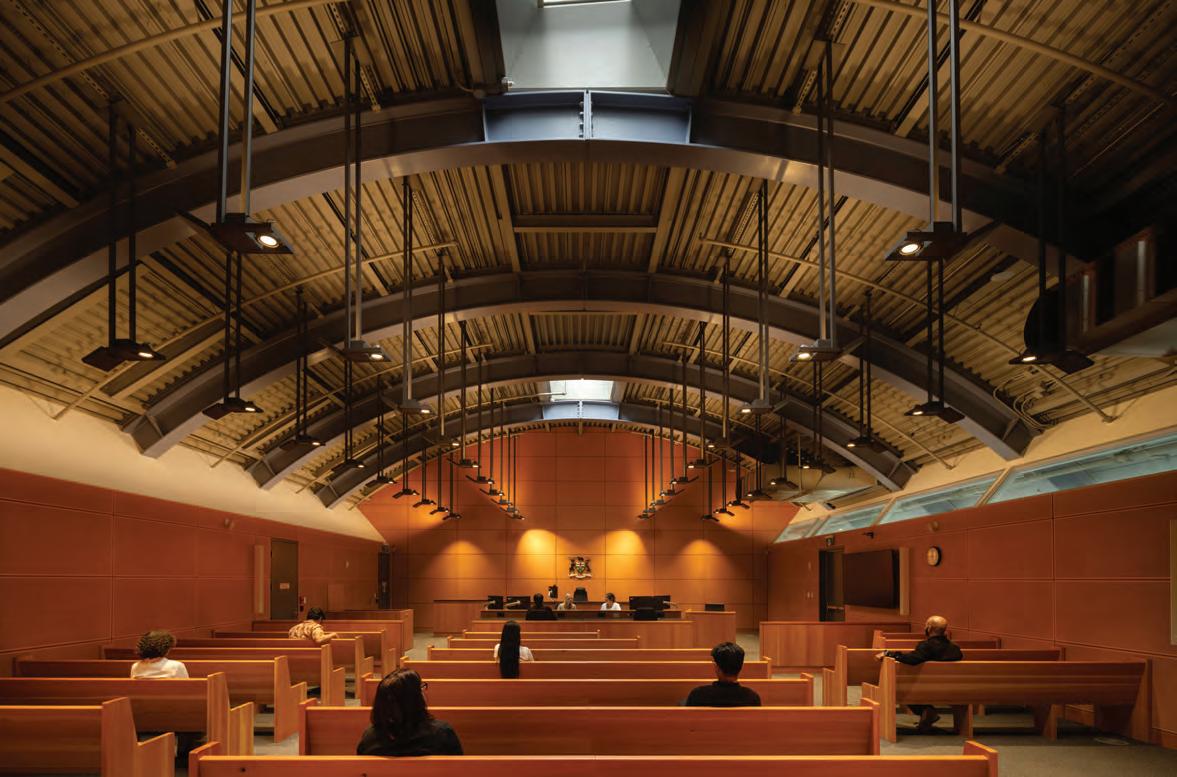

The courthouse floors are fully operational, and they are commendable: lots of quiet (kudos to the acousticians), open-plan Court Services office space on Level 3, with an agreeable amount of natural light

streaming in through fritted glass and exterior brise-soleil fins; wellappointed but not ostentatious Justice of the Peace suites on Level 4. The majority of the courtroom space is on the top floor, under the building’s exposed, barrel-vaulted ceilings and angled bands of atriumbordering skylights. Courthouses require three separate, secure circulation systems: public, judicial, and one for individuals in custody. This building successfully performs this feat with a counterpoint of controlled access and intuitive visual clarity.

The top-floor highlight, the Ceremonial Court, is situated near the southwest corner, behind a glass wall that fronts onto the main public waiting area. It’s intended for celebratory occasions, such as citizenship ceremonies, while also useful for routine affairs such as traffic court. Subtly and appropriately, the book-matched Douglas fir panelling behind the judge’s bench is more refined than the pew-like public seating, in random-matched Douglas fir. Nothing in this dignified space looks too fussy or fine for a market building.

The public waiting area immediately south of this courtroom offers the building’s finest city views. “If you’re in a courthouse, something has gone wrong,” says Harbour. “You should not have to feel that you’re being judged by the building. Although there’s a level of dignity, it shouldn’t feel oppressive. We wanted to make the spaces where people have to wait the best spaces in the building.”

Two significant changes that occurred between the competition-winning design and the built design are good changes. St. Lawrence Market North shrank from six storeys to five storeys lower is better in this heritage context and due to a Toronto green-roof bylaw introduced

CAST CONNEX ® custom steel castingsallow for projects previously unachievable by conventional fabrication methods.

Innovative steel castings reduce construction time and costs, and provide enhanced connection strength, ductility, and fatigue resistance.

Freeform castings allow for flexible building and bridge geometry, enabling architects and engineers to realize their design ambitions.

ST LAWRENCE MARKET NORTH, ON

Architects: RSHP | Adamson Associates

Structural Engineers: Entuitive

Steel Fabricator: Steel 2000 Inc

Custom Cast Solutions simplify complex and repetitive connections and are ideal for architecturally exposed applications.

Steel Erector: E.S. Fox

Photography by Karl Hipolito

after the design competition, the building’s paired, atrium-flanking volumes were capped with simple, shallow, barrel vaults, in place of the competition scheme’s more elaborate pitched roofs, which had skylights running the length of each peak. Although green roofs provide insulation and help retain stormwater, few of those legislated into existence in Toronto have much street presence. Here, however, the sedum gets seen. That’s partly due to the barrel vault curves, and partly to the slight jog Front Street takes a block east of the Jarvis corner, which makes this building very visible from the east for several blocks.

A less successful change was the switch from the competition scheme’s timber lattice overlay to perforated, orange-painted aluminum fins as the main sun-shading strategy for a building with floor-to-ceiling glazing on three sides. Harbour says this was a practical move: there was concern that the timber screen proposed by London-based RSHP would be no match for Toronto’s freeze-thaw cycle.

Exposed structure and bold colour are the hallmarks of RSHP ’s style, and they’re much in evidence on this project. On the choice of orange for the external fins and the decks of the internal bridges, Harbour says, “We wanted a warm colour on the solid parts so that the building sat comfortably with its neighbours.” Sounding very much like his firm’s founder, he adds, “If you go for a shade of such and such, it will be fashionable for a moment and then grossly unfashionable most of its life. The lovely thing about a bold colour is that it’s probably unfashionable from the outset.” To my eye, the orange works, but the scale of the fins does not: they look too dainty on the building’s substantial form.

Although the brise-soleil substitution occurred long before construction start, this project’s overall execution especially at market level and on the exterior bears signs of budget cuts. The main entry looks

flimsy and under-scaled; the steel guards encircling the ground floor’s torpedo-tapered concrete pillars look dent-able.

Such value engineering moves strained to offset the cost of countless changes that overtook the project during its fifteen-year gestation. During Covid, various court proceedings shifted partially and then permanently into the virtual realm; this necessitated extensive technological retrofits on an in-construction building. The City of Toronto changed its workplace space standards; charging stations for electric vehicles had to be added to the parking garage. And so on. Dropped ceilings are anathema to exposed-structure-espousing RSHP, which meant that the much-revised mechanical and electrical systems had to be threaded through structural steel.

St. Lawrence Market North’s one lucky break is that it was completed before the President of the United States launched a global tariff war. If this project illustrates the challenges of reconciling the agendas of clients, architects, and contractors in tumultuous times, we should all be fastening our seatbelts.

VIRDO (MRAIC), DAVID JANSEN (MRAIC), CLAUDINA SULA, ROBERT SULA, MARTIN DOLAN (MRAIC), JACK CUSIMANO, SCOTT CRESSMAN (MRAIC), SARAH GILBERT, LEANNA KNIGHT, ANNA SATCHKOVA, GEORGE GEORGES (MRAIC), KARLA CALVELO, JEANNINE DAO | STRUCTURAL & BUILDING ENVELOPE ENTUITIVE MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL

PROJECT Espace Péribonka, Péribonka, Quebec

ARCHITECT Les Maîtres d’Oeuvre Architectes (MDO)

TEXT Peter Sealy

PHOTOS Stéphane Groleau