CIBINQO is indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy.

Legal Category : S1A. Marketing Authorisation Holder: Pfizer Europe MA EEIG, Boulevard de la Plaine 17, 1050 Bruxelles, Belgium. For further information on this medicine please contact: Pfizer Medical Information on 1800 633 363 or at medical.information@pfizer.com.

▼ This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification of new safety information. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions. See section 4.8 of the SmPC for how to report adverse reactions.

IN THIS ISSUE:

NEWS: 26% of Generic Medicines have ‘Disappeared’

Page 7

FEATURE: Diabetic Retinopathy

Page 14

MEDICINES: The Windsor Agreement and implications for medicines

Page 18

CPD: Atopic Dermatitis

Page 31

DERMATOLOGY

FOCUS: : Patient initiated follow-up

Page 38

DERMATOLOGY

FOCUS: Atopic Dermatitis

Page 40

UROLOGY FOCUS: Prostate Cancer

Page 57

HOSPITAL

NEWS

Hospital Professional Publication HPN June 2023 Issue 109 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE This Publication is for Healthcare Professionals Only © 2022 Pfizer Inc. All rights reserved. July 2022. PP-CIB-IRL-0036

PROFESSIONAL

IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated

NOW HSE REIMBURSED IN IRELAND!

Reimbursement is restricted to use as a subsequent line of therapy following treatment with a lower cost biological disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (bDMARD).

• In phase III studies BIMZELX demonstrated superiority vs ustekinumab (BE VIVID; p<0.0001), placebo (BE READY; p<0.0001) and adalimumab (BE SURE; p< 0.001) in achieving the co-primary endpoints PASI 90 and IGA 0/1 at week 16 with 85% (273/321), 90.8% (317/349) and 86.2% (275/319) of patients achieving PASI 90 at Week 16. At Week 4, 76.9% (247/321), 75.9% (265/349) and 76.5% (244/319) of patients achieved the secondary endpoint of PASI 75.1

• In the BE BRIGHT open label extension study, 62.7% (620/989) of patients achieved PASI 100 at Week 16 (non-responder imputation [NRI]). Of these patients, 84.4% (147/174) of patients randomised to 8 week dosing maintained PASI 100 at Week 148.2

Challenge expectations in psoriasis1,2

Visit Bimzelx.co.uk to discover more

This site contains promotional information on UCB products.

To hear about future UCB projects, educational events and to receive the latest information from UCB, please scan the QR code set your digital preferences.

BIMZELX is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy.1

Prescribing Information and Adverse Event can be found below.

Use this QR code to access Bimzelx.co.uk This site contains promotional information on UCB products.

Note: The most frequently reported adverse reactions with BIMZELX are: upper respiratory tract infections (14.5%) and oral candidiasis (7.3%).1 Other common adverse events include: Tinea infection, ear infection, Herpes simplex infections, oropharyngeal candidiasis, gastroenteritis, folliculitis, headache, dermatitis and eczema, acne, injection site reaction and fatigue.

PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

(Please consult the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing)

BIMZELX® ▼(Bimekizumab)

Active Ingredient: Bimekizumab – solution for injection in prefilled syringe or pre-filled pen: 160 mg of bimekizumab in 1 mL of solution (160mg/mL) Indications: Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy.

Dosage and Administration: Should be initiated and supervised by a physician experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of plaque psoriasis. Recommended dose: 320 mg (given as two subcutaneous injections of 160 mg each) at week 0, 4, 8, 12, 16 and every 8 weeks thereafter. For some patients with a body weight ≥ 120 kg who did not achieve complete skin clearance at week 16, 320 mg every 4 weeks after week 16 may further improve treatment response. Consider discontinuing if no improvement by 16 weeks of treatment. Renal or hepatic impairment: No dose adjustment needed. Elderly: No dose adjustment needed. Administer by subcutaneous injection to thigh, abdomen or upper arm. Rotate injection sites and do not inject into psoriatic plaques or skin that is tender, bruised, erythematous or indurated. Do not shake pre-filled syringe or pre-filled pen. Patients may be trained to self-inject.

Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to bimekizumab or any excipient; Clinically important active infections (e.g. active tuberculosis). Warnings and Precautions: Record name and batch number of administered product. Infection: Bimekizumab may increase the risk of infections e.g. upper respiratory tract infections, oral candidiasis. Caution when considering use in patients with a chronic infection or a history of recurrent infection. Must not be initiated if any clinically important active infection until infection resolves or is adequately treated. Advise patients to seek medical advice if signs or symptoms suggestive of an infection occur. If a clinically important infection develops or is not responding to standard therapy,

carefully monitor and do not administer bimekizumab until infection resolves. TB: Evaluate for TB infection prior to initiating bimekizumab – do not give if active TB. While on bimekizumab, monitor for signs and symptoms of active TB. Consider anti-TB therapy prior to bimekizumab initiation if past history of latent or active TB in whom adequate treatment course cannot be confirmed. Inflammatory bowel disease: Bimekizumab is not recommended in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cases of new or exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease have been reported. If inflammatory bowel disease signs/symptoms develop or patient experiences exacerbation of pre-existing inflammatory bowel disease, discontinue bimekizumab and initiate medical management. Hypersensitivity: Serious hypersensitivity reactions including anaphylactic reactions have been observed with IL-17 inhibitors. If a serious hypersensitivity reaction occurs, discontinue immediately and treat. Vaccinations: Complete all age appropriate immunisations prior to bimekizumab initiation. Do not give live vaccines to bimekizumab patients. Patients may receive inactivated or nonlive vaccinations. Interactions: A clinically relevant effect on CYP450 substrates with a narrow therapeutic index in which the dose is individually adjusted e.g. warfarin, cannot be excluded. Therapeutic monitoring should be considered. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Women of child-bearing potential should use an effective method of contraception during treatment and for at least 17 weeks after treatment. Avoid use of bimekizumab during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Discontinue breastfeeding or discontinue bimekizumab during breastfeeding. It is unknown whether bimekizumab is excreted in human milk, hence a risk to the newborn/infant cannot be excluded. No data available on human fertility. Driving and use of machines: No or negligible influence on ability to drive and use machines. Adverse Effects: Refer to SmPC for full information. Very Common (≥ 1/10): upper respiratory tract

References: 1. BIMZELX (bimekizumab) Summary of Product Characteristics. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/ product/12834/smpc. Accessed April 2023. 2. Strober B et al. Poster P1491 presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) meeting, September 7–10 2022; Milan, Italy.

IE-P-BK-PSO-2300066 Date of preparation: April 2023. © UCB Biopharma SRL, 2023. All rights reserved. BIMZELX® is a registered trademark of the UCB Group of Companies.

infection; Common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10): oral candidiasis, tinea infections, ear infections, herpes simplex infections, oropharyngeal candidiasis, gastroenteritis, folliculitis; headache, dermatitis and eczema, acne, injection site reactions, fatigue; Uncommon (≥ 1/1,000 to < 1/100): mucosal and cutaneous candidiasis (including oesophageal candidiasis), conjunctivitis, neutropenia, inflammatory bowel disease. Storage precautions: Store in a refrigerator (2ºC – 8ºC), do not freeze. Keep in outer carton to protect from light. Bimzelx can be kept at up to 25ºC for a single period of maximum 25 days with protection from light. Product should be discarded after this period or by the expiry date, whichever occurs first.

Legal Category: POM

Marketing Authorisation Numbers: EU/1/21/1575/002 (2 x 1

Pre-filled Syringes), EU/1/21/1575/006 (2 x 1 Pre-filled Pens)

Marketing Authorisation Holder: UCB Pharma S.A., Allée de la Recherche 60, B-1070 Brussels, Belgium. Further information is available from: UCB (Pharma) Ireland Ltd, United Drug House, Magna Drive, Magna Business Park, City West Road, Dublin 24, Ireland.

Tel: 1800-930075 Email: ucbcares.ie@ucb.com

Date of Revision: April 2022 (IE-P-BK-PSO-2200034)

Bimzelx is a registered trademark.

▼This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification ofnew safety information. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adversereactions.

Reporting forms and information can be found at www.hpra.ie/homepage/about-us/report-an-issue Adverse events should also be reported to UCB (Pharma) Ireland Ltd. Email: UCBCares.IE@ucb.com

THIS ADVERT CONTAINS PROMOTIONAL CONTENT FROM UCB AND IS INTENDED FOR HCPS IN IRELAND

Contents Foreword

Hospital pharmacy gives first impressions on revision of General Pharmaceutical Legislation P4

New Theatre opens at St James’s Hospital P5

New Medicines Working Group must Deliver Change P6

On average - 26% of all generic medicines have disappeared P7

New research on cancer-killing benefits of obesity treatment P9

Revolutionising Cerebral Palsy Care P78

REGULARS

Feature: VTE during Pregnancy P20

CPD: Atopic Dermatitis P31

Dermatology Focus: Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma P37

Dermatology Focus: Skin Cancer Prevalence P44

Urology Focus: Overactive Bladder P61

Clinical R&D: P80

Hospital Professional News is a publication for Hospital Professionals and Professional educational bodies only. All rights reserved by Hospital Professional News. All material published in Hospital Professional News is copyright and no part of this magazine may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form without written permission. IPN Communications Ltd have taken every care in compiling the magazine to ensure that it is correct at the time of going to press, however the publishers assume no responsibility for any effects from omissions or errors.

PUBLISHER

IPN Communications Ireland Ltd

Clifton House, Lower Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2 (01) 669 0562

GROUP DIRECTOR

Natalie Maginnis

n-maginnis@btconnect.com

EDITOR

Kelly Jo Eastwood

EDITORIAL

editorial@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

Editor

I one of our lead news stories this month, it is revealed that Ireland is once again one of the slowest countries in Western Europe to reimburse and make available new innovative medicines to patients. This is according to figures gathered by data analysts IQVIA for EFPIA, the European pharmaceutical industry body.

The survey of 37 European countries, including 27 in the European Union, covers the full four years between 2018 and 2021 analysing 168 innovative medicines authorised for use by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Oliver O’Connor, Chief Executive of the Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association, said, “Over the past three budgets, the Government has allocated almost ¤100 million to new medicines. The figures released today show how urgent it is now to improve the reimbursement system so that new medicines are available to patients and their doctors faster.”

Turn to page 6 for the full story.

In other medicines news, on page 7, we detail how across Europe - on average - 26% of all generic medicines have disappeared. Unsustainable pricing policies are one of the leading drivers of shortages, says Medicines for Europe. Affordable generic medicines available on the market just 10 years ago are disappearing and supply is too consolidated, according to new data shared. This rapid decline and consolidation, higher in certain therapy areas such as cancer care and antibiotics, risks creating more shortages and threatens vital access for patients.

The data showed that the whole generic medicines supply chain is under heavy pressure, with prices being pushed down to the limit of their sustainability. Strikingly, medicines supply consolidation is not just at the active ingredient level but also medicines, thereby creating risks of shortages and reducing access.

ACCOUNTS

Fiona Bothwell cs.ipn@btconnect.com

SALES EXECUTIVE

Amy Evans - amy@ipn.ie

CONTRIBUTORS

Áine Toher

Sarah Mohamed

Dr Cathal O’Connor

Claire Quigley

Eoin.R.Storan

Anna Wolinska

Claire Doyle

Dr Emma Porter

Dr Rebecca Helen

Kevin O’Hagan

James Powell

Helen Forristal

Charles O’Connor

Gregory Nason

Mohammed Hegazy

David Galvin

Theresa Lowry-Lehnen

Dr Fardod Kelly

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Ian Stoddart Design

Áine Toher, Senior Pharmacist and Sarah Mohamed, Pharmacy Intern, both with The National Maternity Hospital give a clinical overview of Low Molecular Weight Heparin for treatment and prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) during Pregnancy. Failure to recognise and/or treat personal or pregnancy specific risk factors has been identified as a significant contributing factor to maternal mortality and morbidity from VTE in pregnancy, they say. You can read more about this on page 20.

Our clinical special focus this issue is on Dermatology and Urology; these two therapeutic areas highlighting a number of excellent contributed articles across headings such as ‘Dermatology mycology diagnostics in Ireland’ and ‘Prostate cancer in Ireland.’

I hope you enjoy the issue.

3 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • JUNE 2023 June Issue Issue 109 5

7 78 HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE @HospitalProNews HospitalProfessionalNews

Fostering Cancer Care in Ireland

Pictured at the official announcement of the partnership were, left to right; Averil Power, CEO, Irish Cancer Society, Dr Linda Doyle, Provost and President of Trinity College, Professor John Kennedy, Medical Director, TJSCI, Professor Maeve Lowery, Academic Director, TSJCI and Noel Gorman, Interim CEO, St James's Hospital

I’m also glad to see that the experience of patients will be included in approaches to research, clinical trials, clinical care and education.”

The Irish Cancer Society has announced a new partnership with Trinity College Dublin and St James’s Hospital designed to develop an outstanding programme of cancer treatment and care for patients in Ireland.

The five-year collaboration will see the Society invest ¤4.5million in several specific exemplar programmes aimed at delivering a new model of cancer care for patients in Ireland.

By investing in the Trinity St James’s Cancer Institute (TSJCI) the Irish Cancer Society aims to accelerate the translation of cancer research into new treatments and better support for patients.

The partnership will integrate Irish Cancer Society services into the

hospital pathway and enhance the patient experience by ensuring better collaboration with patients across research, cancer clinical trials, clinical care, and education.

Dr Linda Doyle, Provost and President of Trinity College Dublin, said, “I want to thank the Irish Cancer Society for this investment and I’m looking forward to a fantastic partnership.

‘We have huge ambitions for cancer research in Trinity and for the Trinity St James Cancer Institute. Today’s announcement is a step towards realising those ambitions.

I particularly welcome the partnership’s goal to accelerate the translation of research into new treatments and better supports for patients.’

Mr Noel Gorman, Interim CEO, St James’s Hospital said, “The challenges posed by cancer in Ireland are such that extensive targeted investment is required to bring about the improvements in facilities, treatment, research and education that will ensure the best outcomes for our patients in the decades to come. This major investment by the ICS in TSJCI programmes for younger patients with gastrointestinal cancers is a statement of intent by both institutions to build a comprehensive collaboration which will address in a multidisciplinary fashion the myriad problems faced by patients with cancer.”

Prof John Kennedy, Medical Director, Trinity St James’s Cancer Institute said: “Today, the Irish

Hospital Pharmacy give First Impressions

The European Commission has finally released the longawaited proposal for the revision of the General Pharmaceutical Legislation, comprised of a draft Regulation and a draft Directive to improve the delivery and availability of medicines for human use in the European Union (EU).

The European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) and its members welcome the publication that also marks the start of the negotiation process for this crucial piece of EU legislation. Despite the draft Regulation and the draft Directive being very comprehensive, further amendments should be considered by the legislators, especially those:

• Guaranteeing a very high level of patient safety across Europe

• Combatting antimicrobial resistance and fostering prudent use of antibiotics

• Ensuring accessibility and addressing the root causes of medicine shortages to adequately prevent and control them

• Upholding the high level of pharmacovigilance in Europe

• Enhancing the safety of the health workforce and the environment

Reflecting on the content of the proposal EAHP President

András Süle stressed that "More ambitious measures are needed to enhance patients' access to high-quality and affordable medicinal products across the European Union. Unmet medical needs and access to medicines should be better addressed by utilising the unique compounding skills of hospital pharmacists and their expertise in pharmacology targeting the deconstruction and execution of therapies and in

medicines procurement preserving the financial sustainability of healthcare systems. In addition to advancing innovation, patient safety should be put at the centre of the legislation. Seamless transitions between the interfaces of different health settings need to be considered during the implementation of the proposal to ensure that the patient care started in hospitals can be continued in the community."

Linked to the serious threat of antibiotic resistance that jeopardises the effectiveness of standard treatments EAHP Vice-President Darija Kuruc Poje highlighted that "Arrangements need to be made to ensure that essential antibiotics are maintained on the entire European market including an increase of European production sites to lower dependency on international markets. The subscription models proposed in the UK and Sweden are an interesting approach for

Cancer Society (ICS) announced it is investing ¤4.5m to fund innovative cancer research and care at the Trinity St James’s Cancer Institute (TSJCI). The focus is on pioneering programmes that addresses an unmet need identified by the ICS and TSJCI, specifically for the increasing numbers of younger patients with gastrointestinal cancer. It fits within a Comprehensive Cancer Care model, linking medicine and science, bringing relevant research to the patient, focussing a dedicated multidisciplinary team around an unmet need, and supporting clinicians to devote their time to both patient care and research.”

Professor Maeve Lowery, Academic Director, Trinity St James’s Cancer Institute added, “At TSJCI we work to integrate scientific discovery with patient care to pioneer new ways to prevent, detect and treat cancer. The urgency of this is evidenced by a concerning rise in the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers among patients under fifty years of age. This significant investment by ICS will accelerate the delivery of innovative and comprehensive cancer services to Irish patients and facilitate a long- term partnership based on a shared mission to deliver the major improvements in cancer care that our patients deserve. “

guaranteeing availability. There are however some questions that remain. Due to national particularities, criteria for the establishment of the subscription model, which factor in national needs, must be defined. In the interest of patient care, also, reimbursement of treatment options outside the subscription model would need to be ensured. In addition, to safeguard the availability of antibiotics, also stewardship programmes need to be supported in order to encourage prudent use of them by healthcare professionals and patients."

EAHP has released an Opinion on the Revision of the General Pharmaceutical Legislation that outlines specific concerns and urges the legislators to ameliorate the proposal in the fields of patient safety, antimicrobial resistance, accessibility of medicines, including medicine shortages, pharmacovigilance and the environment.

4 JUNE 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

New Launch at St James’s Hospital

A lecture theatre dedicated to the memory of Professor Davis Coakley, Founding Director of the Mercer’s Institute for Successful Ageing, has been launched in MISA.

Davis Coakley, who died in September 2022 after a short illness, is one of Ireland’s best known physicians and medical historians.

He held a personal Chair in Medical Gerontology in Trinity College Dublin, awarded in 1996; the first such academic appointment in the country. He went on to establish the first Department of Medical Gerontology, home to many of Ireland’s PhD, MD and Master graduates in the speciality. He pioneered many national policy and service developments benefitting ageing in Ireland over a 40 year period.

Having led negotiations with the American charity, Atlantic Philanthropies and their founder,

Professor J Bernard Walsh, Mary Coakley and Professor Rose

Anne Kenny

Chuck Feeney, he secured a large philanthropic award enabling Ireland to command a leadership role in research in ageing and in a new purpose built institute for successful ageing at St James’s Hospital, known as the Mercer’s Institute for Successful Ageing (MISA). MISA was launched by President Michael D Higgins in 2016.

In addition to publishing over 150 original scientific papers, he published 18 books on medical science and on historical and literary subjects. Two of his medical books were deemed “pioneering volumes in their field”. His beautifully illustrated book “The Anatomy Lesson; Art and Medicine” informed a successful exhibition of Irish anatomical art at the National Gallery. His “Irish

Child and Youth Mental Health Lead

Masters of Medicine” collated the important historical contributions to medicine of 42 Irish medical practitioners and “The Importance of Being Irish; Oscar Wilde” –was the first ever biography to explore how Wilde’s formative years in Ireland had a significant impact on his life and writings, a concept which evolved from

Davis’ extensive knowledge of the medical cultural milieu in which Oscar spent his early years.

It is almost impossible to do justice to the essence of this great scholar and clinician, to his remarkable interpersonal skills and his ever present wit and roguish sense of humour.

Minister for Mental Health and Older People Mary Butler welcomed the opening of the recruitment process for the post of Child and Youth Mental Health Lead in the HSE. This key new role will provide leadership, operational oversight, and delegated management of all service delivery across child and youth mental health services across the country. They will also be responsible for managing and coordinating service planning activities, partnership and capacity building, the development of service plans, and setting of service standards right across child and youth mental health services in Ireland.The post holder will report to the HSE National Director for Community Operations and will be supported by a dedicated team for which funding has been provided.

This role, and the wider Child and Youth Mental Health office, will result in improved links with the National Clinical Advisor Group Lead Mental Health, which in turn will support the development of current and future youth mental healthrelated National Clinical Programmes.

Minister Butler stated, “The progression of this role has been a key priority for me over the past year, and it will play a crucial part in ensuring that integrated mental health services for young people have a more centralised and evidence-based focus within the HSE. “We will see the completed reviews and audits arising from the Maskey Report, along with the Final Report of the Mental Health Commission on CAMHS later this year, which together will give us real time data never available before to support this new post. Importantly, there will be new support staff to underpin this welcome initiative. I will ensure that the HSE also progresses as quickly as possible the new post of National Clinical Lead for Youth Mental Health as announced in the Dáil over the last week.”

Calls for Increased Collaboration

The Private Hospitals Association (PHA) has said it stands ready once again to assist the HSE in helping to reduce growing public hospital waiting lists.

PHA says it is fully committed to collaborating with the government and the HSE in order to alleviate the burden on the public system and to enhance access to timely and quality scheduled care for all citizens.

The announcement comes on back of confirmation that over 85,000 hospital appointments or procedures alone, had to be

cancelled in the first four months of 2023.

CEO of the PHA, Jim Daly, says a joint approach between public and private can bring about a more tangible solution to these challenges.

“After having seen some hopeful signs of progress in this area of late, it is regrettable to once again see public hospital waiting numbers moving upward again in April, and at a time when we traditionally should be making substantive inroads against these lists. The high number of cancelled procedures for each month this year highlights how

underlying structural challenges such as insufficient bed capacity now has an continuously negative impact on full hospital service provision across the public system. The 20 member hospitals across the island of Ireland are at all times ready to work hand-in-hand with the HSE to address this crisis, and provide added capacity as required for the patients most in need of important medical procedures.

"Based both north and south of the border, our member hospitals offer available theatre and bed capacity and clinical expertise which can be quickly called upon to help

reduce waiting times and improve patient outcomes. Our hospitals employ highly skilled healthcare professionals who are ready to contribute their resources and expertise to this collective effort.”

Mr Daly added that private hospitals are committed to optimising all resources such as operating theatres, diagnostics and specialist consultations to assist patients on public waiting lists. By sharing this capacity through collaboration with the HSE, it would help to significantly reduce the backlog of cases and improve waiting times.

5 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • JUNE 2023

News

New Medicines Working Group must Deliver Change

can make these medicines available faster to patients, as quickly as 102 days, while still managing budgets and doing value for money assessments.

Ireland is once again one of the slowest countries in Western Europe to reimburse and make available new innovative medicines to patients, according to figures gathered by data analysts IQVIA for EFPIA, the European pharmaceutical industry body.

The survey of 37 European countries, including 27 in the European Union, covers the full four years between 2018 and 2021 analysing 168 innovative medicines authorised for use by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Key points this year are:

• While it takes on average 517 days, post EMA authorisation, to make a new medicine

routinely available across European countries, in Ireland it takes 567 days.

• This time has lengthened in Ireland since 2020: up almost 100 days from 477 three years ago. This is despite the welcome allocation of new funds for new medicines by the Government.

• The number of days it takes for new cancer medicines to be made available to patients has increased to 673 post EMA authorisation for Ireland. This wait of nearly two years is far too long for cancer patients as availability of new medicines is a recognised contributor to Ireland’s improved survival rates in cancer. Many other countries

• Only six of 37 European countries take longer than Ireland to reimburse orphan medicines for rare diseases, of which 95% do not have a recognised medical treatment. It currently takes on average 877 days from EMA market authorisation of orphan medicines for them to become available to Irish patients. The number of days taken depends both on the timing of companies’ applications and the decision-making processes of health authorities. In Ireland, the figures suggest that between 25% and 30% of the timing is attributable to IPHA member companies’ timing of applications for the reimbursement of a medicine to the HSE after the product has been granted EMA market authorisation. The bulk of the timing is taken by the State’s assessment and decision-making process, which typically includes price negotiations with companies.

Longer timelines to availability mean a lower standard of care than could be available for Irish patients, and thus poorer patient outcomes than otherwise could be achieved. The experience of other countries demonstrates that improved partnerships between health authorities and pharmaceutical companies are possible and should become a policy priority in Ireland.

IPHA is keen to work with Government and State bodies to improve the process. We have

welcomed the publication by Minister Donnelly of the Mazars Report in February, and we are looking forward to engaging with the Department of Health Working Group, established to reform the reimbursement system and to report back to the Minister within six months.

Oliver O’Connor, Chief Executive of the Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association, said, “Over the past three budgets, the Government has allocated almost ¤100 million to new medicines. The figures released today show how urgent it is now to improve the reimbursement system so that new medicines are available to patients and their doctors faster. Process reform has to go alongside new funding. That’s why we have welcomed the Minister’s new Working Group to build out recommendations from and beyond the Mazars report. We have welcomed the recommendations on transparency already approved by the Minister and look forward to working on further improvements.

“The lengthening timelines demonstrate that there is a significant job to be done to make innovative medicines available faster to Irish patients. In particular, there is a serious issue with the timelines in relation to orphan medicines and medicines for cancer care. We have six months to agree new practical steps and then start implementing. IPHA member companies are ready to collaborate with all stakeholders through the Working Group to ensure this happens sooner rather than later.”

6 JUNE 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Click Here to Register Digital Version Only

26% of Generic Medicines have ‘Disappeared’

Medicines for Europe Director General Adrian

Across Europe - on average26% of all generic medicines have disappeared. Unsustainable pricing policies are one of the leading drivers of shortages, says Medicines for Europe.

Affordable generic medicines available on the market just 10 years ago are disappearing and supply is too consolidated, according to new data shared recently. This rapid decline and consolidation, higher in certain therapy areas such as cancer care and antibiotics, risks creating more shortages and threatens vital access for patients.

The data showed that the whole generic medicines supply chain is under heavy pressure, with prices being pushed down to the limit of their sustainability. Strikingly, medicines supply consolidation is not just at the active ingredient level but also medicines, thereby creating risks of shortages and reducing access.

The system is broken and must be fixed.

Key Data:

• Of all the generic medicines available 10 years ago, 26% of generic medicines, 33% of antibiotics and 40% of cancer medicines have disappeared from European markets, on average.

• More than two-thirds (69%) of EU generic medicines on the market now have just one or two suppliers. If one manufacturer has a problem, there will likely be a medicine shortage causing disruption and possible harm for health care practitioners and for patients.

• 20 years ago, Europe used to make about half of the ingredients needed to make its medicines – now it’s down to about a fifth.

Policymakers at the national level need to change their policy approach to pricing of medicines with:

• Dynamic market rules to maintain more suppliers active in the market.

• Multi-criteria, multi winner tenders, beyond lowest price only.

• An inflation-linked-pricing adjustment mechanism.

• Open dialogue between suppliers and the medicines agency to rapidly address supply bottlenecks.

At the EU level, the focus needs to be on a streamlined policy framework with:

• Regulatory optimisation and digitalisation, including security of supply provisions in the revision of the pharmaceutical legislation.

• Security of supply safeguarded in all policies including in environmental legislation.

• Legal guidance on multi-winner and multi-criteria tenders in procurement which is requested by both industry, procurers, hospitals, and healthcare practitioners.

• An industrial policy that supports medicines manufacturing in Europe notably with efficient and competitive funding mechanisms.

Philippe Drechsle, Chair of Medicines for Europe manufacturing committee and Executive Committee member (Teva Pharmaceuticals Europe), said “This research made a health check of Europe’s essential medicine cabinet. We found increasingly empty shelves and a limited variety of essential medicines. Many of these now have just one manufacturer.

“The solutions are there to be implemented both at European and national levels. In the case of pricing, national laws tend to award drug suppliers based on the lowest generic price alone –and ignore important issues like sustainability, which swiftly leads to a less resilient industry, less robust supply chains and worse patient outcomes. This needs to be fixed. The EU has its role to play by adopting legislation that considers the impact of any new additional requirement on medicines availability across Europe. Our regulatory system is too costly, and the environmental obligations should deliver a winwin for the planet and patients’ access to medicines”.

Medicines for Europe Director General Adrian van den Hoven adds, “Antibiotic shortages this winter were a sad example of the policy gaps that make the supply of essential medicines so fragile. For years, generic medicine policies have been based on the lowest price only, with restrictive tender or reference pricing rules. These policies have fuelled market consolidation which make it difficult to respond to sudden demand surges. We are also working with the EU to improve disease forecasting in Europe to better plan manufacturing ahead of infectious seasons. These issues must be addressed in the revision of the EU pharmaceutical legislation.”

7 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • JUNE 2023

News

van den Hoven

“For years, generic medicine policies have been based on the lowest price only, with restrictive tender or reference pricing rules. These policies have fuelled market consolidation which make it difficult to respond to sudden demand surges. These issues must be addressed in the revision of the EU pharmaceutical legislation”

Boosting Lung Cancer Screening in Ireland and Beyond

The first pilot programmes will be held in 10 EU countries (Croatia, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Greece). Many of these serve remote communities far from a hospital. So SOLACE will help provide transportation or mobile screening units.

Marie-Pierre Revel, from Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris (APHP), describes how a programme in France is planning to use “media coverage, including local newspapers and flyers, and sending women invitations for lung cancer screening along with their annual invitations er with invitation letters for breast cancer screening.”

A pioneering EU4Health project – under Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan – is launching a programme to expand lung cancer screening in countries throughout Europe.

This new initiative, called SOLACE, will break down barriers to screening so that people across all social and economic groups can access it.

Almost 2,700 people are diagnosed with lung cancer each year in Ireland. The 5-year survival rate tells you what percent of people live at least 5 years after the cancer is found. Presently it’s approximated at 24%.Not surprisingly, lung cancer has the lowest 5-year survival rate of the other most common cancers: only 24%, versus prostate at 99%; breast at 89%; and colorectal at 65%.

Lung cancer is the fourth most common cancer in Ireland after prostate, breast and colorectal.

More than a quarter million people in Europe die from lung cancer each year, according to the European Network of Cancer Registries. That's more than from any other cancer. However, like any other cancer, the disease is more treatable when caught early.

Low-Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) is a safe, simple, and effective way of screening for lung cancer. Multiple trials in the USA and Europe have shown that LDCT can reduce deaths from lung cancer by 20%. The new EU-funded project will support Member States by providing a personalised toolbox to national and regional centres to facilitate lung-cancer screening programmes, with a particular focus on groups that are at higher risk due to health inequalities.

“This project will provide a comprehensive guideline for initiating lung cancer screening programmes with state-of-the-

art quality and high participation rates. Typical mistakes can then be avoided, and life expectancy increased,” says Hans-Ulrich Kauczor, the project's scientific coordinator.

Many individuals at high risk are currently not accessing lung cancer screening – often because of historical inequalities that exist with marginalised and vulnerable communities. Smoking can also be more prevalent in these groups, further compounding their risk of lung cancer.

Ivica Belina, a member of the European Lung Foundation Lung Cancer Patient Advisory Group, said, “One of the main problems with lung cancer is stigma. We need a change how we relate to people suffering from lung cancer, from a societal point of view. The SOLACE project can really change that and lift the stigma for patients.”

This three-year project is coordinated by the European Institute for Biomedical Imaging Research (EIBIR) and will be implemented by the SOLACE consortium under the scientific leadership of experts appointed by the European Society of Radiology and the European Respiratory Society. Patient-led organisations, European Lung Foundation, and Lung Cancer Europe will provide patient input.

The SOLACE consortium includes 33 entities, including academic and research institutions, university hospitals, national health authorities, organisations and associations representing patients and health care professionals. The European Cancer Organisation is supporting the project’s dissemination, and policy impact. In the long term, the project will provide valuable insights on how best to implement a cost-effective screening programme for lung cancer and the best techniques for reaching out to those groups that are at particularly high risk.

8 JUNE 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

See ALK+ aNSCLC, Think Brain Metastases, Choose ALUNBRIG (brigatinib)

FIRST-LINE ESMO RECOMMENDATION2

NOW APPROVED FOR ONCE-DAILY FIRST-LINE TREATMENT OF ALK+ aNSCLC3

A lunbr ig is indic ate d as monother apy for the treatment of adul t patient s wi th A L K+ aNS CLC previously: 3

- not treate d wi th an A L K inhibi tor, or, - previously treate d wi th cr izotinib

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; aNSCLC, advanced non-small cell lung cancer; ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology.

References:

1. Camidge DR, et al. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:2091-2108;

2. Planchard

D, et al. Annals Oncol. 2018;29(S4): iv192–237 - Updated version published 15 September 2020. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/3853nnnu. Accessed June 2022.

3. Alunbrig (brigatinib) Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at: https://www.medicines.ie/medicines/alunbrig-34655/ Accessed June 2022.

ALUNBRIG®t(brigatinib) PRESCRIBING INFORMATION FOR REPUBLIC OF IRELAND

Refer to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing

Presentation: Brigatinib 180 mg, 90 mg and 30 mg film-coated tablets. Indications: As monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) previously not treated with an ALK inhibitor. As monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC previously treated with crizotinib. Dosage and administration: Recommended starting dose is 90 mg once daily for the first 7 days, then 180 mg once daily. If ALUNBRIG is interrupted for 14 days or longer for reasons other than adverse reactions, treatment should be resumed at 90 mg once daily for 7 days before increasing to the previously tolerated dose. If a dose is missed or vomiting occurs after taking a dose, an additional dose should not be administered and the next dose should be taken at the scheduled time. Treatment should continue as long as clinical benefit is observed. Dosing interruption and/or dose reduction may be required. Refer to SmPC for full dose adjustments. Paediatric population: No data are available. Elderly patients: Dose adjustment is not required. No available data on patients aged > 85 years. Hepatic impairment: A reduced starting dose of 60 mg once daily for the first 7 days, then 120 mg once daily is recommended for patients with severe hepatic impairment (ChildPugh class C). Renal impairment: A reduced starting dose of 60 mg once daily for the first 7 days, then 90 mg once daily is recommended for patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min). Patients with severe renal impairment should be closely monitored for new or worsening respiratory symptoms (e.g., dyspnoea, cough, etc.) particularly in the first week. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients. Warnings and precautions: Refer to SmPC for recommended dose modifications. Pulmonary adverse reactions: Most occurred within the first 7 days of treatment, but they can occur later in treatment. Patients should be monitored for new or worsening respiratory symptoms (e.g., dyspnoea, cough, etc.), particularly in the first week of treatment. If interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis is suspected, the dose of ALUNBRIG should be withheld, and the patient evaluated for other causes of symptoms (e.g., pulmonary embolism, tumour progression, and infectious pneumonia). Dose modification may be required. Hypertension: Heart rate and blood pressure should be monitored regularly. Hypertension should be treated according to standard guidelines. Heart rate should be monitored more frequently in patients if concomitant use of a medicinal product known to cause bradycardia cannot be avoided. Withhold ALUNBRIG in patients with severe hypertension (≥ Grade 3) until hypertension has recovered to Grade 1 or to baseline. Modify dose accordingly. Bradycardia: Caution should be exercised when administering ALUNBRIG in combination with other agents known to cause bradycardia. If symptomatic bradycardia occurs, treatment with ALUNBRIG should be withheld and concomitant medicinal products known to cause bradycardia should be evaluated. Upon recovery, the dose should be modified according to SmPC. In case of life-threatening bradycardia, if no contributing concomitant medication is identified or in case of recurrence, treatment with ALUNBRIG should be discontinued. Visual disturbance: Advise

patients to report any visual symptoms. Consider ophthalmologic evaluation/dose reduction for new or worsening severe symptoms. Creatine phosphokinase (CPK) elevation: Patients should be advised to report any unexplained muscle pain, tenderness, or weakness. CPK levels should be monitored regularly during ALUNBRIG treatment. Based on the severity of the CPK elevation, and if associated with muscle pain or weakness, treatment with ALUNBRIG should be withheld, and the dose modified. Elevations of pancreatic enzymes: Lipase and amylase should be monitored regularly during treatment with ALUNBRIG. Based on the severity of the laboratory abnormalities, treatment with ALUNBRIG should be withheld, and the dose modified. Hepatotoxicity: Liver function, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin should be assessed prior to the initiation of ALUNBRIG and then every 2 weeks during the first 3 months of treatment. Thereafter, monitoring should be performed periodically. Based on the severity of the laboratory abnormalities, treatment should be withheld, and the dose modified. Hyperglycaemia: Fasting serum glucose should be assessed prior to initiation of ALUNBRIG and monitored periodically thereafter. Antihyperglycaemic medications should be initiated or optimised as needed. If adequate hyperglycaemic control cannot be achieved with optimal medical management, ALUNBRIG should be withheld until adequate hyperglycaemic control is achieved; upon recovery, dose reduce ALUNBRIG as per the SmPC or permanent discontinuation may be considered. Photosensitivity and photodermatosis: Photosensitivity to sunlight has occurred in patients treated with ALUNBRIG. Patients should be advised to avoid prolonged sun exposure while taking ALUNBRIG and for at least 5 days after discontinuation of treatment. When outdoors, advise patients to wear a hat and protective clothing and to use a broad-spectrum Ultraviolet A/B sunscreen and lip balm (SPF≥30). For severe photosensitivity reactions (≥Grade 3) withhold ALUNBRIG until recovery to baseline. The dose should be modified accordingly. Lactose: ALUNBRIG contains lactose monohydrate. Patients with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, total lactase deficiency, or glucose-galactose malabsorption should not take ALUNBRIG. Sodium: ALUNBRIG is essentially ‘sodium-free’ containing less than 1 mmol sodium (23 mg) per tablet. Interactions: Avoid use with strong CYP3A inhibitors. Avoid use with strong and moderate CYP3A inducers. Please refer to SmPC for further information and guidance for situations where use cannot be avoided. Grapefruit or grapefruit juice should be avoided. Coadministration of ALUNBRIG with CYP3A substrates with a narrow therapeutic index should be avoided as ALUNBRIG may reduce their effectiveness. Coadministration of ALUNBRIG with substrates of P-glycoprotein, breast cancer resistance protein, organic cation transporter 1, multidrug and toxin extrusion protein (MATE) 1 and 2K may increase their plasma concentrations. Patients should be closely monitored when ALUNBRIG is co-administered with substrates of these transporters with a narrow therapeutic index. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Women of reproductive potential should be advised not to become pregnant and to use effective non-hormonal

contraception during treatment with ALUNBRIG and for at least 4 months following the final dose. Men should be advised not to father a child during ALUNBRIG treatment. Men with female partners of reproductive potential should be advised to use effective contraception during and for at least 3 months after the last ALUNBRIG treatment. No clinical data on the use of ALUNBRIG in pregnant women. ALUNBRIG should not be used during pregnancy unless the clinical condition of the mother requires treatment. Breastfeeding should be stopped during treatment with ALUNBRIG. No human data are available on the effect of ALUNBRIG on fertility. Undesirable effects: Very common (≥1/10): Pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection, anaemia, lymphocyte count decreased, APTT increased, white blood cell count decreased, neutrophil count decreased, hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinaemia, hypophosphataemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypercalcaemia, hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia, decreased appetite, headache, peripheral neuropathy, dizziness, visual disturbance, hypertension, cough, dyspnoea, lipase increased, diarrhoea, amylase increased, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, stomatitis, AST increased, ALT increased, alkaline phosphatase increased, rash, pruritus, blood CPK increased, myalgia, arthralgia, blood creatinine increased, fatigue, oedema, pyrexia. Common (≥1/100 to <1/10): Decreased platelet count, insomnia, memory impairment, dysgeusia, bradycardia, electrocardiogram QT prolonged, tachycardia, palpitations, pneumonitis, dry mouth, dyspepsia, flatulence, blood lactate dehydrogenase increased, hyperbilirubinaemia, dry skin, photosensitivity reaction, musculoskeletal chest pain, pain in extremity, musculoskeletal stiffness, non-cardiac chest pain, chest discomfort, pain, blood cholesterol increased, weight decreased. Other serious undesirable effects: Uncommon: (≥1/1,000 to <1/100): Pancreatitis. Refer to the SmPC for details on full side effect profile and interactions. Legal classification: POM. Marketing authorisation (MA) numbers: EU/1/18/1264/011, EU/1/18/1264/008, EU/1/18/1264/010, EU/1/18/1264/012. Name and address of MA holder: Takeda Pharma A/S, Delta Park 45, 2665 Vallensbaek Strand, Denmark. Additional information is available on request at: medinfoemea@takeda.com. PI approval code: pi-01842. Date of Preparation: January 2022.

tThis medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring.

Adverse Events should be reported to the Pharmacovigilance Unit at the Health Products Regulatory Authority. Reporting forms and information can be found at: www.hpra.ie. Adverse events should also be reported to Takeda at: AE.GBR-IRL@takeda.com

1

C-APROM/IE/ALUN/0051. Date of preparation: June 2022 Takeda Oncology, and ALUNBRIG are registered trademarks of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. ©2022 Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. All rights reserved.

Bed Shortages will ‘Worsen’ – says IMO

The Irish Medical Organisation (IMO) has warned that investment in additional hospital beds is not keeping pace with population growth and that the current dire situation will worsen unless rapid action is taken.

The warning comes after it emerged that over 700 patients around the country were waiting on a hospital bed today (Tuesday).

It also described recent revelations that just 162 new beds would be added to the Irish public hospital system this year as “shocking”.

The IMO said that being unable to move admitted patients to a ward bed in a timely manner is leading to poorer health outcomes for

patients and intolerable conditions for those trying to treat them in an appropriate setting.

It added that, although senior decision-makers were working and available on weekends, discharge pathways and support services are not in place to enable patients to be transferred to appropriate care. Speaking today, Professor Matthew Sadlier, Chair of the Consultant Committee of the IMO, said, “There is an acute need for 5,000 additional beds if we are to provide adequate care for the population. The dire shortage of beds adds to overcrowding in hospitals and EDs, longer waiting lists and poorer patient outcomes.

“It is unacceptable that over 700 patients are currently waiting on a hospital bed after the May bank holiday and emphasises that this is a year-round crisis.

“The idea that just 162 additional beds will be added to the stock this year is shocking and confirms that a long-standing bed shortage will get worse this year not better.”

The IMO cited international figures which highlight how far behind Ireland is in terms of bed capacity compared to other European countries. The average in Europe is 3.87 acute beds per 1,000 people whereas in Ireland the figure is just 2.7 beds per 1,000 of the population.

Mater Private Network invests ¤3m

The IMO has previously called for the use of modular builds to provide additional capacity at hospitals which are under particular pressure.

Professor Sadlier said: “We have to go beyond tinkering with the beds issue. We need urgent action to alleviate crisis points and we need a commitment to a meaningful increase in the number of additional – not replacement –beds. This crisis will persist until we have sufficient beds and doctors to meet the needs of growth in our population and address the complexity of care required.”

Mater Private Network continues to pave the way for the future of healthcare through consistent investment in leading technology across its network of facilities here in Ireland.

Today, Mater Private Network celebrates the commissioning of a new CT scanner in its Radiology Department on Eccles St. This new state-of-the-art equipment, produced by Siemens, is a core element of a significant radiology investment programme to the value of ¤3 million.

Until now, Mater Private Network’s diagnostic imaging services in Dublin has been performing 300-350 CT scans per week; this new CT scanner will deliver a two-fold capacity increase for CT scanning, with waiting lists virtually eliminated as a result. Patients will also benefit from the cutting-edge technology, which gives excellent image quality and reduces the radiation dose to the lowest possible level. With the opening hours for radiology services now extended into the late evening and running seven days a week across

the three Mater Private Network Dublin facilities, this also helps to address the challenge of long waiting lists that exists nationally, and greatly improves access for patients for diagnostic imaging. This transformational project has been supported by a robust, and highly successful recruitment campaign which has seen the Mater Private Network Radiology team increase by 30% and bringing a range of international expertise across the Dublin facilities.

Celebrating the commissioning of the new CT scanner, Prof. Peter J MacMahon, Director of Radiology at Mater Private Network in Dublin, commented, “I am particularly excited about this development and what it means for our patients. Thanks to this new CT scanner, we will be able to diagnose and treat more patients than ever before with our multidisciplinary team of highly skilled of professionals. This is a fantastic step forward for Mater Private Network. We are committed to staying at the forefront of medical technology so that we can continue to deliver the best possible care to those who trust us with their health”.

Bernard Bonroy, Radiology Services Manager, Mater Private Network, has said, “We are proud to be able to offer an enhanced service from our Radiology Department here in Dublin.

Recruiting the right team to ensure we could provide this enhanced service was our north star when working on this project, and I am delighted to share that this has led to a 30% increase in radiography staff across our Dublin sites. Our team at Eccles St. is best in class and we strive to ensure seamless patient care for those who pass through our doors”.

10 JUNE 2023 • HPN |

Report

HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

Back row - Bernard Bonroy, Professor Peter MacMahon, Dr. Daragh Murphy, Front row - Ciara Newell, Bahia Raffie, Theresa Gleeson, Deirdre Lynch photographed with the new CT Scanner at Mater Private Network Radiology Department, Eccles St., Dublin

New research reveals cancer-killing benefits of popular obesity treatment

Maynooth University’s Kathleen Londsdale Institute for Human Health Research has just published ground-breaking research into the benefits of the popular obesity treatment drug, GLP-1. Previous research has found that people with obesity are at a greater risk of developing cancer, in part due to their anticancer immune cell -- better known as the ‘Natural Killer (NK)’ cell -- being rendered useless due to their disease.

New Health Research Board (HRB) funded research carried out by Dr Andrew Hogan and his team in the Londsdale Health Institute at Maynooth University, has found that the popular, and gold-standard pharmacological treatment for obesity, Glucagonlike peptide (GLP-1) analogues, can actually restore the NK cell function in the body including its ability to kill cancerous cells.

Currently, one in four Irish adults are living with obesity, a disease linked to up to 40% of all cancers.

The research, published in Obesity, the Obesity Society’s Research Journal, one of the world’s leading peer-reviewed obesity journals, also shows that the restored cancer-killing effect of the NK cells is independent of the GLP-1’s main weight loss function so it appears the treatment is directly kick-starting the NK cells’ engine.

Dr Andy Hogan

Dr Andrew E. Hogan, Associate Professor & Principal Investigator, Lonsdale Human Health Institute in Maynooth University discussed the findings stating, “My team and I are very excited by these new findings in relation to the effects of the GLP-1 treatment on people with obesity and it appears to result in real tangible benefits for those currently on the drug.

“While these findings will understandably be welcomed by those living with obesity and looking for safe and effective treatments, it must be noted that unfortunately, these treatments are not fully covered by the Government’s Drug Payment Scheme. With the findings of this research, it’s more important than ever that the HSE work with the Government to ensure the benefits of this treatment become available to as many individuals as possible and as soon as possible.

“Secondly, given the recent spike in popularity related to the benefits of the GLP-1 treatment with global and high-profile celebrities commenting on its success, global demand has increased and resulted in a worldwide shortage of the drug.

“Again, I hope this is something that is brought under control to ensure as many people as possible living with obesity can start their own treatment of this beneficial drug.”

Conor de Barra, PhD student in immunology at Maynooth University and Irish Research Council Scholar, who led the work in Dr Hogan’s lab on this particular research said: “People with obesity can develop a variety of health problems like type 2 diabetes, sleep apnoea and cancer. These can have very negative impacts on their quality of life. This research and other promising findings on improvements in cardiovascular health after GLP-1 therapy indicate

Honorary Fellowship for Professor Clarke

Professor Graeme Clark AC – pioneer of the bionic ear, or multi-channel cochlear implant –has been awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI).

The Honorary Fellowship of RCSI is the highest distinction the College bestows, recognising outstanding clinical achievements and humanitarians that include Nelson Mandela, Mother Teresa of Calcutta and President Jimmy Carter.

The multichannel implant developed by the team led by Professor Clark, in association with the Australian firm Cochlear Limited, is the world’s first device to restore a human sense and allow severely-to-profoundly deaf people to understand speech. It has been the world leader for 40

years and has the dominant share of the one million people now implanted in over 120 countries. Professor Clark’s achievements have been recognised globally. His numerous prestigious awards include Australia’s highest civil honor, a Companion of the Order of Australia, for services to medicine in 2004, and Senior Australian of the Year in 2001 and many international honors, including the Lasker DeBakey Award, considered the American Nobel in Clinical Medical Research.

He is a Laureate Professor at the University of Melbourne and a member of The Graeme Clark Institute for Biomedical Engineering, which was named in his honour and seeks to transform healthcare with biomedical engineering.

potential benefits in addition to weight-loss.”

Prof Donal O’Shea, HSE National Lead for Obesity & Principal Investigator, added, “We are finally reaching the point where medical treatments for the disease of obesity are being shown to prevent the complications of having obesity. The current findings represent very positive news for people living with obesity on GLP-1 therapy and suggest the benefits of this family of treatments may extend to a reduction in cancer risk.”

Dr Hogan presented these findings at the 30th European Congress on Obesity, which was held in Dublin on 20th of May.

11 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • JUNE 2023

News

Professor Graeme Clark AC pictured with Professor Laura Viani, RCSI President

Diabetes during Pregnancy in HIV on the Rise

at the British HIV Association conference recently in Gateshead. The study also found that the proportion of women diagnosed with high blood pressure during pregnancy has not risen.

Blood sugar levels can rise during pregnancy, leading to the development of diabetes. Women are at higher risk of gestational diabetes if they are overweight or have obesity, have a South Asian, Black or African Caribbean or Middle Eastern background, or if a close family member has had diabetes. Having HIV does not raise the risk of developing gestational diabetes, but protease inhibitorbased antiretroviral treatment may raise the risk if it is started early in pregnancy.

lower risk of developing high blood pressure during pregnancy than women without HIV.

The UK study looked at the prevalence of diabetes and high blood pressure during pregnancy in women with HIV in the United Kingdom and Ireland between January 2010 and December 2020. The study also looked at the relationship between gestational diabetes and hypertension and adverse pregnancy outcomes including stillbirth, pre-term birth and low birth weight.

The study evaluated 10,401 pregnancies in 8998 women with HIV; 1104 pregnancies were excluded from the analysis either because HIV was diagnosed during pregnancy or because delivery occurred prior to 24 weeks (either miscarriage or very pre-term birth). The annual number of pregnancies in women with HIV halved between 2010 and 2020, from just under 1300 a year to approximately 600 a year in 2020.

history of diabetes, or belonged to a minority ethnic group with a high prevalence of diabetes.

Gestational diabetes was diagnosed during 554 pregnancies in 503 women; in 511 cases this was defined as gestational diabetes.

High blood pressure was diagnosed during 511 pregnancies in 458 women. In three out of four cases (383 pregnancies), high blood pressure was associated with a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, a serious complication of pregnancy. Pre-eclampsia is usually detected by the presence of high levels of protein in the urine and high blood pressure. Pre-eclampsia affects transfer of oxygen across the placenta, affecting foetal growth and raising the risk of stillbirth and premature birth. In severe cases, preeclampsia may lead to fits or liver or kidney failure in the mother.

The frequency of diabetes during pregnancy is rising in women with HIV in Ireland and the UK, in line with trends in the rest of the population, Laurette Bukasa of University College London reported

A recently published study of pregnancies in South Africa’s Western Cape province found that women with HIV on antiretroviral treatment before conceiving had a

Women were screened for gestational diabetes between weeks 24 and 28 of pregnancy if they had a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or above, a previous baby with a high birth weight, a family

The prevalence of high blood pressure did not change significantly between 2010 and 2020 (3.9% in 2010, 5.8% in 2020). Both diabetes and high blood pressure were diagnosed during 46 pregnancies in 43 women.

Latest Figures on Sexually Transmitted Infections

There has been “at least” a 100% increase in teenagers getting diagnosed with STIs this year, a consultant in sexual health has said.

Figures from the HSE have revealed that 783 teenagers in Ireland have been diagnosed with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in 2023.

The figures included two children who are under 14 years of age.

The most common STI in Ireland this year was chlamydia with 4,311 cases, followed by gonorrhoea with 2,326 cases.

The news come after it was revealed earlier this year that HIV rates more than doubled in Ireland over the last year, according to statistics published by the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC).

The body responsible for tracking rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has reported that for the first 51 weeks of the year, cases across nine disease types had risen by 56 per cent.

The upward trend follows concerns that Covid-19 restrictions had hampered testing services and the ability of people to present themselves for testing.

Consultant of sexual health and HIV care in genitourinary medicine at St. James Hospital Dr

Aisling Loy said the data “definitely is alarming.”

“It's preliminary data so it gets cleaned up at the end of the year … before it's cleaned up it still is indicative that we are seeing a big rise,” she said.

Dr Loy said last year’s cleaned-up data revealed a total of 950 STI diagnoses among teenagers. “We're already on track to see maybe at least a 100% increase this year,” she said. “We’re a third way through the year and we’re at 700.

“Even when you take out some duplicate cases … there will be a slight drop, but not a huge drop.”

Dr Loy said that within the group of 15- to 19-year-olds, gonorrhoea diagnoses are driving the numbers.

“Traditionally in that age category, it was chlamydia, but actually that had gone down 6% in females, I think around 9% in young men,” she said.

“There's been a huge increase in gonorrhoea in that group.

“Traditionally we thought of these as being sexually transmitted by say penis to vagina, and that it would be traditional sexual routes of transmission.

56 Recommendations for ‘More Inclusive’ Ireland

Fine Gael LGBTQ+ launched Building on Progress: An Inclusive Ireland, a policy document designed to guide officials toward developing a more equal society. It makes 56 recommendations across seven government departments, namely Education, Equality, Foreign Affairs, Health, Housing & Local Government, Justice and Sport.

In the publication, the group outlines over 20 pressing issues that LGBTQ+ people face in Ireland today. These include HIV transmissions, transgender healthcare, hate crimes, safety in schools, conversion therapy, surrogacy, participation in sport, global rights, homelessness and more.

The document was created independently by Fine Gael LGBTQ+, a voluntary organisation made up of party members, staff and Oireachtas officials. While it has been submitted to Fine Gael for consideration, it has not been officially adopted as policy.

On Wednesday, May 3, parliamentary members of the party held a briefing to have a “constructive and positive conversation” on LGBTQ+ issues.

12 JUNE 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE HIV News

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic Retinopathy in Ireland

“By identifying TRPV2 as a key protein involved in diabetesrelated vision loss, we have a new target and opportunity to develop treatments that halt the advancement of diabetic retinopathy.”

The study was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Department for the Economy Postgraduate Studentship scheme. Diabetic retinopathy risk factors:

• Blood sugar levels

The control of blood sugar levels is of immense importance. Lower blood sugar levels can delay the onset and slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy

• Blood pressure

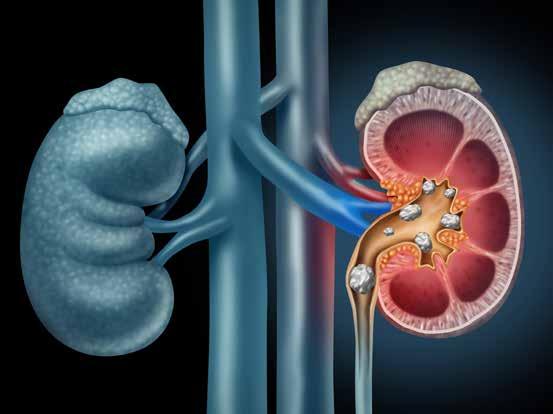

Diabetic retinopathy is a common complication of diabetes and occurs when high blood sugar levels damage the cells at the back of the eye, known as the retina. There are no current treatments that prevent the advancement of diabetic retinopathy from its early to late stages, beyond the careful management of diabetes itself. As a result, a significant proportion of people with diabetes still progress to the vision-threatening complications of the disease.

As the number of people with diabetes continues to increase globally, there is an urgent need for new treatment strategies, particularly those that target the early stages of the disease to prevent vision loss.

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of blindness in working age individuals' in Ireland, at the present time. It is estimated that there are approximately 190,000 people in Ireland with diabetes and 10 per cent of them are at risk of sight threatening retinopathy.

Diabetic RetinaScreen commenced its national population-based diabetic retinopathy screening programme at the end of February 2013 and this is being introduced on a phased basis to ensure quality and safety.

Diabetic RetinaScreen will deliver great benefits to men and women with diabetes in Ireland who are at risk of sight threatening retinopathy, enhancing quality of

life and preserving sight for longer. Of the population screened and treated, it is expected that six per cent will be prevented from going blind within a year of treatment and 34 per cent within ten years of treatment.

The test looks for early warning signs of diabetic retinopathy, a complication of diabetes caused by high blood glucose (sugar) levels damaging the back of the eye (retina). If left undiagnosed and untreated diabetic retinopathy may lead to blindness. However, if diabetic eye disease is found early, treatment can reduce or prevent damage to your sight.

Diabetic RetinaScreen Programme Manager, Helen Kavanagh says, “If left undiagnosed and untreated diabetic retinopathy can deprive people of their sight, but it usually takes many years to reach that stage. This free eye screening test offers people with diabetes an opportunity to detect problems early, which can lead to more successful treatment and better outcomes. The longer you have diabetes the higher the risk, that’s why we’re encouraging everyone aged 12 years and older to be registered with Diabetic RetinaScreen today.”

Latest Research

Last year, researchers at Queen’s University in Belfast uncovered a key process that contributes to vision loss and blindness in those with diabetes.

The retina demands a high oxygen and nutrient supply to function properly. This is met by an elaborate network of blood vessels that maintain a constant flow of blood even during daily fluctuations in blood and eye pressure. The ability of the blood vessels to maintain blood flow at a steady level is called blood flow autoregulation. The disruption of this process is one of the earliest effects of diabetes in the retina.

The breakthrough made by researchers at Queen’s University Belfast pinpoints the cause of these early changes to the retina. The study, has discovered that the loss of blood flow autoregulation during diabetes is caused by the disruption of a protein called TRPV2. Furthermore, they show that disruption of blood flow autoregulation even in the absence of diabetes causes damage closely resembling that seen in diabetic retinopathy. The research team are hopeful that these findings will be used to inform the development of new treatments that preserve vision in people with diabetes.

Professor Tim Curtis, Deputy Director at the Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine at Queen’s and corresponding author, explains, “We are excited about the new insights that this study provides, which explain how the retina is damaged during the early stages of diabetes.

High blood pressure damages blood vessels, raising the chances for eye problems. Effective control of blood pressure reduces the risk of retinopathy progression and visual acuity deterioration

• Duration of diabetes

The risk of diabetic retinopathy developing or progressing increases over time. After 15 years, 80 per cent of Type 1 patients will have diabetic retinopathy. After 19 years, up to 84 per cent of patients with Type 2 diabetes will have diabetic retinopathy

• Blood lipid levels (cholesterol and triglycerides)

Elevated blood lipid levels can lead to greater accumulation of exudates, protein deposits that leak into the retina. This condition is associated with a higher risk of moderate visual loss

• Pregnancy

Women who have diabetes and become pregnant have an increased risk of developing retinopathy. If they already have diabetic retinopathy, it may progress

Symptoms

1. Gradually worsening vision

2. Sudden vision loss

3. Shapes floating in your field of vision (floaters)

4. Blurred or patchy vision

5. Eye pain or redness

14 JUNE 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication

HIT BACK A

RINVOQ® (UPADACITINIB) IS NOW INDICATED IN

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

PRESCRIBING INFORMATION (PI). RINVOQ®▼ (upadacitinib) 15 mg prolonged release tablets; 30mg prolonged-release tablets; 45 mg prolonged-release tablets. Refer to Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for full prescribing information. PRESENTATION: Each tablet contains upadacitinib hemihydrate, equivalent to 15mg of upadacitinib in the 15mg tablet, 30mg in the 30mg tablet and 45mg in the 45mg tablet. INDICATION: Treatment of moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in adult patients who have responded inadequately to, or who are intolerant to one or more disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). RINVOQ may be used as monotherapy or in combination with methotrexate. Treatment of active nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) in adult patients with objective signs of inflammation as indicated by elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), who have responded inadequately to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in adult patients who have responded inadequately to conventional therapy.