IN THIS ISSUE:

NEWS: Hospital Pharmacy Shortages Survey Page 4

MEDICINES: Mazars Report welcomed by pharmaceutical industry Page 7

CONFERENCE: History of Urology Page 10

FEATURE: Ovarian Cancer Page 17

CPD: Diabetes and Insulin Prescribing Page 31

GASTROENTEROLOGY FOCUS: Colon Capsule Endoscopy Page 36

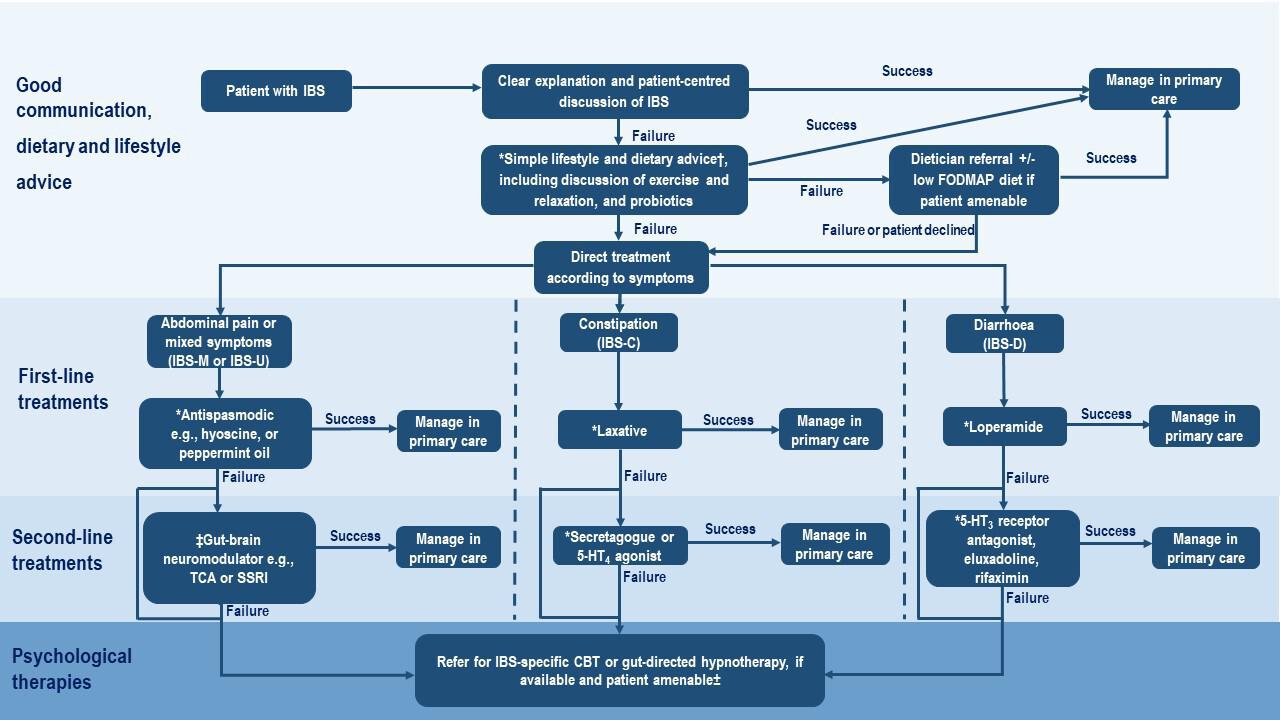

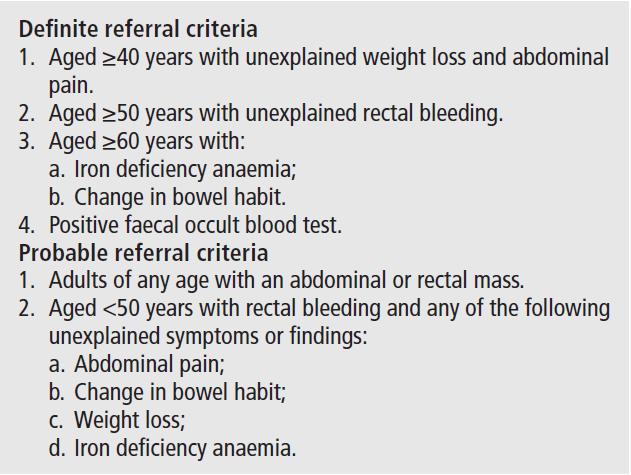

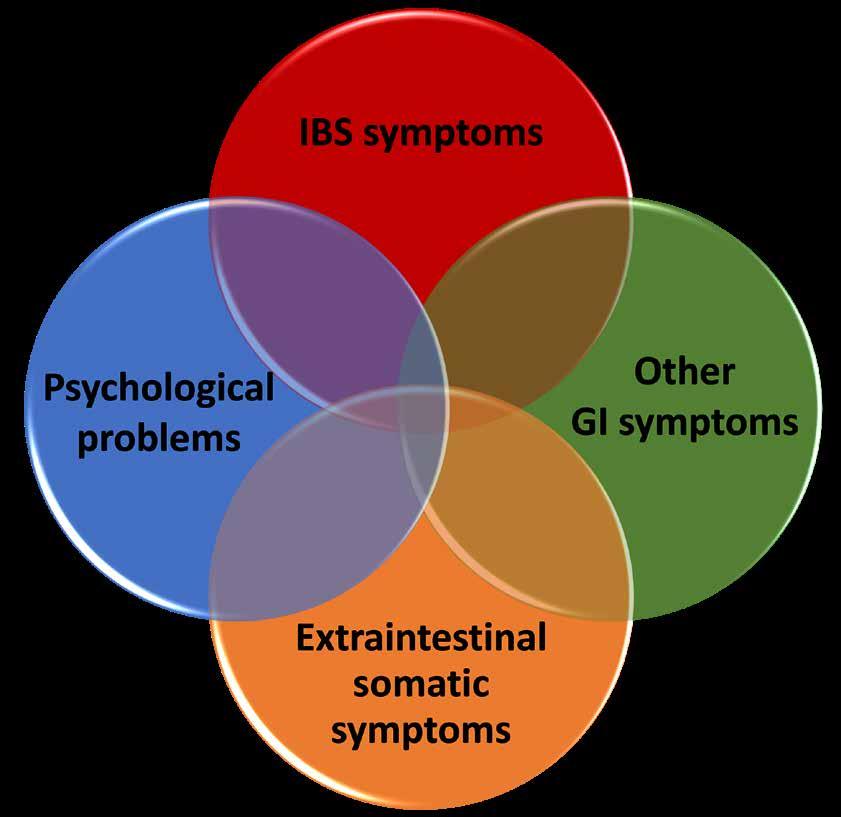

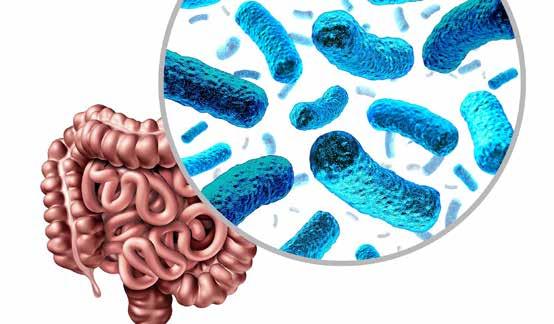

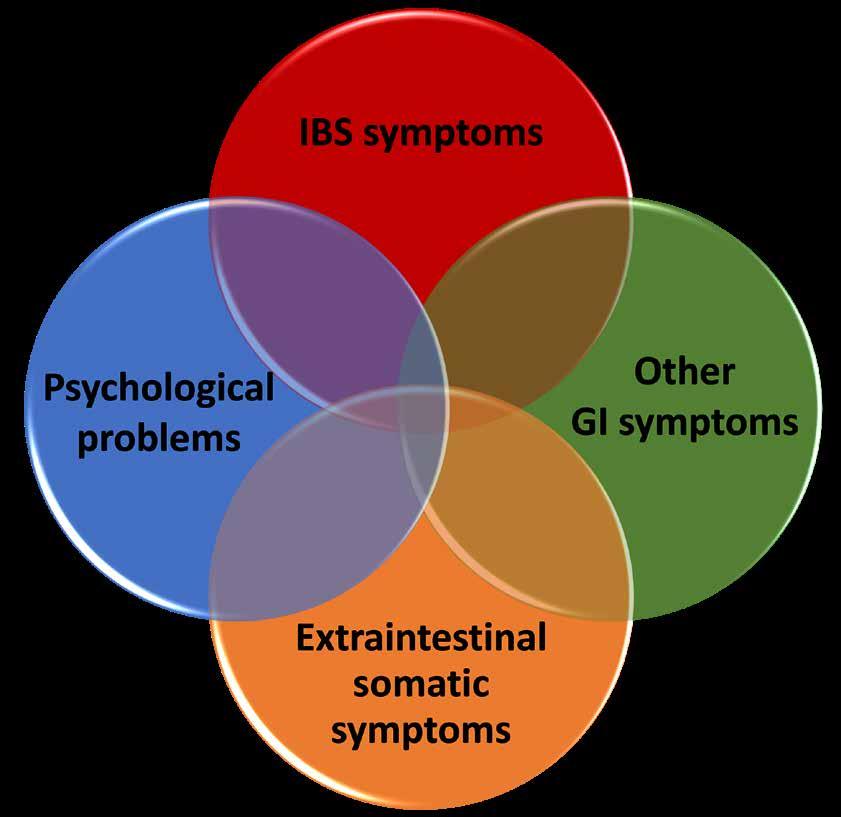

ENDOCRINOLOGY FOCUS: Personalised approaches to IBS Page 43

HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication HPN March 2023 Issue 106 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE This Publication is for Healthcare Professionals Only NOW RINVOQ® (upadacitinib) INDICATED FOR ADULTS WITH MODERATE TO SEVERELY ACTIVE ULCERATIVE COLITIS1 *RINVOQ® is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis who have had an inadequate response, lost response or were intolerant to either conventional therapy or a biologic agent.1 AbbVie® is a registered trademark of AbbVie Inc. RINVOQ® and its design are registered trademarks of AbbVie Inc. REFERENCES: 1. RINVOQ® summary of product characteristics, available at www.medicines.ie. JAK: Janus kinase; UC: ulcerative colitis. Further information is available from AbbVie Limited, 14 Riverwalk, Citywest Business Campus, Dublin 24, Ireland. Legal Classification: POM(S1A). IE-RNQG-220007 August 2022 Full Summary of Product Characteristics is available at medicines.ie ▼ This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification of new safety information. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions via HPRA Pharmacovigilance; website: www.hpra.ie. Reporting suspected adverse reactions after authorisation of the medicinal product is important. It allows continued monitoring of the benefit/risk balance of the medicinal product.

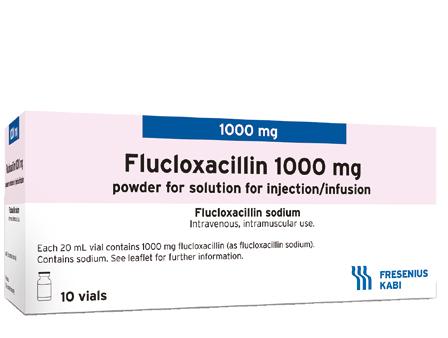

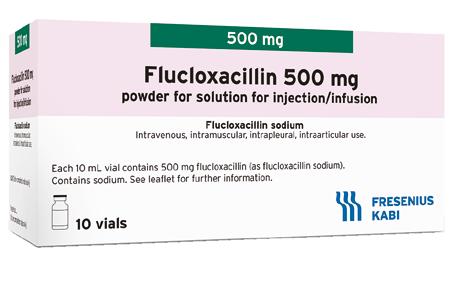

Flucloxacillin Powder for solution for injection/infusion

PRESCRIBING INFORMATION: Consult the Summary of Product Characteristics for further information. Additional information is available upon request. Flucloxacillin 500mg, 1000mg and 2000mg powder for solution for injection/infusion. Active ingredients: As flucloxacillin sodium, each 10mL vial contains 500mg flucloxacillin (25.5mg sodium approximately), 20mL vial contains 1000mg flucloxacillin (51mg sodium approximately), 50mL vial contains 2000mg flucloxacillin (102mg sodium approximately). Indications: For the treatment of the following infections due to beta-lactamase producing staphylococci and other sensitive Gram-positive organisms such as streptococci – skin and soft tissue infections (like abscesses, cellulitis, infected burns, impetigo), upper respiratory tract infections (like pharyngitis, tonsillitis, sinusitis), lower respiratory tract infections (like pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, pulmonary abscess), bone and joint infections (like osteomyelitis and arthritis), endocarditis. Prophylaxis in cardiovascular surgery (valve prostheses, artery prostheses) and orthopedic surgery (arthroplasty, osteosynthesis and arthrotomy). Consideration should be given to official guidance on appropriate use of antibacterial agents. Posology and method of administration: Parenteral therapy is indicated if oral route impracticable or unsuitable as in the case of severe diarrhoea or vomiting and particularly for urgent treatment of severe infection. Routes of administration: 500mg vial - Intramuscular (im), intravenous (iv), intrapleural and intraarticular. 1000mg vial and 2000mg vial – intramuscular and intravenous routes only. Intravenous injection/ infusion should be administered slowly. Dosage depends on age, weight and renal function as well as the severity and nature of the infection. Adults and adolescents ≥ 12 years – Total daily dosage of 1g to 4g, administered in three to four divided doses, by iv or im injection. Severe infections: up to 8g per day administered in four infusions (over 20 to 30 min). No single bolus injection or infusion should exceed 2g. Maximum dose of 12g per day should not be exceeded. In surgical prophylaxis: 2g iv (bolus or infusion) upon induction of anesthesia, to be repeated every 6h for 24h in vascular and orthopedic surgery, and for 48h in cardiac or coronary surgery. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Endocarditis: 2g every 6h, increasing to 2g every 4h in patients weighing >85kg. Children under 12 years of age – In mild to moderate infections: 25 to 50mg/kg/24 hours administered in three to four equally divided doses by im or iv injection. Severe infections: Up to 100mg/kg/24 hours in three to four divided doses. No single bolus injection or infusion should exceed 33mg/kg. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Endocarditis: 200mg/kg/24 hours in three to four divided doses. Premature infants, neonates, sucklings and infants – Risk of kernicterus; only use in premature infants and neonates after rigorous risk-benefit assessment. Treatment is generally with 25mg to 50mg/kg/24 hours divided into three or four equal doses.

Maximum daily dose 100mg/kg/24 hours. Abnormal renal function – Renal excretion slowed in patients with renal insufficiency. In severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <10ml/min) consider dose reduction or extension of dose interval. Maximum recommended dose in adults is 1g every 8 to 12 hours. In anuric patients maximum dosage is 1g every 12 h. Flucloxacillin not significantly removed by dialysis hence no supplementary dosages need be administered either during or at end of dialysis period. Hepatic impairment – Dose reduction not necessary. Intrapleural and intraarticular – Usual dose is 250mg to 500mg once daily. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or excipients, should not be given to patients with history of hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibiotics, patients with previous history of flucloxacillin-associated jaundice/hepatic dysfunction. Not suitable for ocular or subconjunctival administration or intrathecal injection. Special warnings and precautions for use: Before initiating therapy with flucloxacillin check patient history concerning previous hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactams. Cross sensitivity between penicillins and cephalosporins is well documented. Serious and

occasionally fatal hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in patients receiving beta-lactam antibiotics, occurrence more frequent with parenteral compared to oral therapy. Reactions more likely to occur in patients with history of beta-lactam hypersensitivity. If allergic reaction occurs discontinue flucloxacillin and institute appropriate therapy. Feverish generalized erythema associated with pustula occurring at treatment initiation may be a symptom of acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP); in case of AGEP diagnosis discontinue flucloxacillin and subsequent administration is contraindicated. Use with caution in patients with evidence of hepatic dysfunction, patients ≥50 years of age and those with serious underlying disease; hepatic events may be severe and in extremely rare circumstances deaths have been reported. Flucloxacillin solutions reconstituted with local anesthetics (lidocaine) should not be given by iv administration. Adjust dose in renal impairment. Special caution essential in newborns due to risk of hyperbilirubinaemia and potential for high serum levels of flucloxacillin due to reduced rate of renal excretion. Regular monitoring of blood count, hepatic and renal function recommended during prolonged treatment. Pseudomembranous colitis can occur; if this develops discontinue flucloxacillin and initiate appropriate therapy. Prolonged use may occasionally result in overgrowth of nonsusceptible organisms. Caution when administered concomitantly with paracetamol due to increased risk of high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA). High risk of HAGMA particularly in patients with severe renal impairment, sepsis or malnutrition especially if maximum daily doses of paracetamol used. Following co-administration close monitoring recommended to detect the appearance of HAGMA (including testing for urinary 5-oxoproline). If flucloxacillin is continued after paracetamol cessation, it is advisable to ensure no HAGMA signals. Particular caution with drug-induced liver injury in patients with HLA-B*5701 haplotype; frequency of these disorders increasing in HIV-infected patients who may be at increased risk of exposure to flucloxacillin. Hypokalaemia (potentially life threatening) can occur especially at high doses and may be resistant to potassium supplementation. Regularly measure potassium levels during high dose flucloxacillin therapy. Attention warranted when combining flucloxacillin with hypokalaemia inducing diuretics or when other risk factors for development of hypokalaemia present. Contains sodium, consider in patients on a sodium controlled diet. Undesirable effects: Common (>1/100 to <1/10): Minor gastrointestinal disturbances. Uncommon (>1/1000 to <1/100): Rash, urticaria, purpura. Very rare (<1/10,000): Neutropenia (including agranulocytosis), thrombocytopenia, eosinophilia, haemolytic anaemia, anaphylactic shock, angioneurotic oedema, high anion gap metabolic acidosis, pseudomembranous colitis, neurological disorders with convulsions possible with high dose iv injection in patients with renal failure, hepatitis, cholestatic jaundice, changes in liver function laboratory test results, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, arthralgia, myalgia, interstitial nephritis, fever sometimes develops more than 48 hours after start of treatment. Frequency not known: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, phlebitis. Legal Category: POM Marketing Authorisation Numbers: PA2059/069/001, PA2059/069/002, PA2059/069/003. Marketing Authorisation Holder: Fresenius Kabi Deutschland GmbH, Else-Kroener Strasse 1, Bad Homburg v.d.H 61352, Germany Further Information: See the SmPC for further details. Adverse events should be reported. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions via HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Earlsfort Terrace, IRL - Dublin 2, Tel: +353 1 6764971, Fax: +353 1 6762517. Website: www.hpra.ie, E-mail: medsafety@hpra.ie. Adverse events should also be reported to Fresenius Kabi Limited via email Pharmacovigilance.GB@Fresenius-Kabi.com. Date of Preparation: August 2021 IE-IVF-2100004

of Prep: August 2021

500mg 1000mg 2000mg Fresenius Kabi Limited Fresenius Kabi Ireland Unit 3B Fingal Bay, Balbriggan, Co. Dublin, Ireland Website: www.fresenius-kabi.com/ie/ Email: FK-enquiries.ireland@fresenius-kabi.com Phone: +353 (0)1 841 3030

Date

Ref: IE-IVF-2100007

Pharmacy Departments

renew Memorandum of

Understanding P5

Medicine shortages index standing at 247 P6

Mazars Report welcomed by pharmaceutical industry P7

Advances in the field of HIV P20

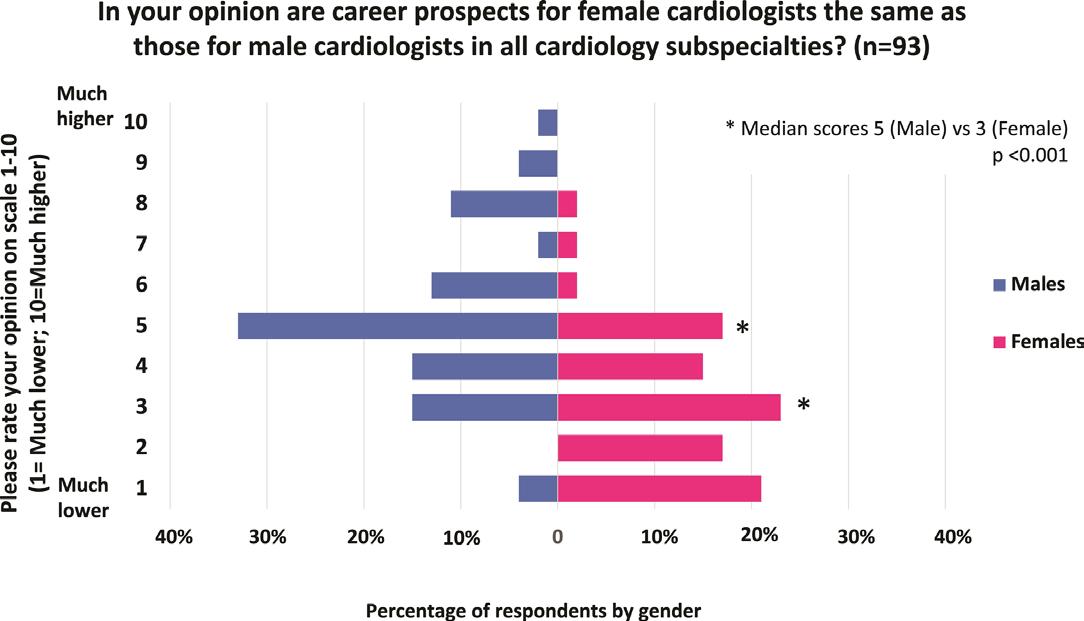

Promoting equality and diversity in Gender orientation

sexual health P23

Women in Surgery Fellowship for Dr Murphy P29

REGULARS

CPD: Insulin Prescribing P31

Endocrinology Focus: Liver Disease and Pregnancy P39

Endocrinology Focus: Pancreatic Cancer P50

Endocrinology Focus: Diabetes P56

Feature: Lipid Guidelines for clinical practice P72

Clinical R&D: P80

Hospital Professional News is a publication for Hospital Professionals and Professional educational bodies only. All rights reserved by Hospital Professional News. All material published in Hospital Professional News is copyright and no part of this magazine may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form without written permission. IPN Communications Ltd have taken every care in compiling the magazine to ensure that it is correct at the time of going to press, however the publishers assume no responsibility for any effects from omissions or errors.

PUBLISHER

IPN Communications Ireland Ltd Clifton House, Lower Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2 (01) 669 0562

GROUP DIRECTOR

Natalie Maginnis n-maginnis@btconnect.com

EDITOR

Kelly Jo Eastwood

EDITORIAL

editorial@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

ACCOUNTS

Rachel Wilson cs.ipn@btconnect.com

SALES EXECUTIVE

Aoife Tremere aoife.t@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

CONTRIBUTORS

Bernadette Carter | Ann Piercy

Dr Ken Patterson | Niall Davis

Diana Hogan-Murphy | Eimear Gibbons

Dr OB Kelly | Barry Hall

Samantha Vega | Cassandra Herron

Omar Elsherif | Ms Rand Al-Najim

Professor Humphrey J O’Connor

Jemma Henry | Theresa Lowry-Lehnen

Tatiana Iamak | Dr Jonathan Briody

Dr Kate McCann | Dr Werd Al-Najim

Professor Alex Miras | Aideen Stack

Professor Fiona Lyon

Professor Mary Higgins

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Ian Stoddart Design

Editor

Healthcare workforce shortages are not a new phenomenon triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. They were simply exacerbated by it. Shortages of nurses or physicians in hospitals, particularly in rural areas are frequently featured in news outlets across Europe.

However, not only these professions are affected but also the pharmacy workforce, including pharmacists, technicians and others. Especially those working in hospitals have to cope with staffing which is insufficient to meet patients' needs. To address the problem of pharmacy workforce shortages, the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) and its members started an in-depth analysis of the situation in Europe.

A workshop conducted with delegates from EAHP's member countries in June last year was followed by an Investigation of the Hospital Pharmacy Profession in Europe that closed in the first quarter of 2023. “High-quality education in all European countries is of utmost importance for addressing the workforce problems of pharmacists to ensure that the profession remains an integral part of healthcare,” says EAHP. You can read more about this on page 5 of this issue.

In other news, the decision by Minister for Health, Stephen Donnelly T.D. to publish the Mazars Report has been welcomed by the Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association as a positive step towards providing Irish patients with faster access to lifechanging new medicines. Turn to page 7 for the full details.

In one of your leading clinical features this month, Professor Fiona Lyon discusses recent advances in the field of HIV. Professor Lyon is Medical Director/Clinical Lead in Sexual Health, HSE Sexual Health and Crisis Pregnancy Programme and Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, GUIDE Clinic, St. James’s Hospital.

“Four decades since the first reports of HIV and AIDS in Ireland, massive advances have been made in the field of HIV medicine such that in 2023 individuals newly diagnosed with HIV have the potential for life expectancy similar to that of the general population and new HIV infections could be prevented,” says Professor Lyon.

“In 2023, there is a vast range of HIV treatment and prevention options available. It is critical that our health system and broader society is responsive and adaptable to ensure the best possible outcomes for people living with HIV (PLWH) and those at risk of acquiring HIV.” You can read the full article on page 20.

Meanwhile, our special focus for March is on Gastroenterology/ Endocrinology & Nutrition and we have some excellent contributed content, including personalised approaches to IBS, Pancreatic cancer and diabetes care in Ireland.

I hope you enjoy the issue.

3 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • MARCH 2023 March Issue Issue 106 7

Contents Foreword

23 9 29 HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE @HospitalProNews HospitalProfessionalNews

Health service has ‘eye off the ball’

A leading Professor at the University of Limerick has said that the continued trend towards imposing a corporate model in our public health system is compounding the service’s inability to deliver care to patients.

Speaking in a New Video as part of the Irish Hospital Consultants Association’s (IHCA) Care Can’t Wait campaign, Professor Orla Muldoon says too much emphasis is being placed on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and not enough on providing the capacity and resources required for treating patients.

The Professor of Psychology explains how this in turn has created a ‘management class’ in the public health service of which many decision-makers are not medical professionals.

She questions why the medical and surgical specialists and leaders in hospitals are not “trusted to manage the system” or the people they care for on a daily basis.

Commenting, she said, “We have this paradox where patients, once they get into the system, feel the quality of care is good. Yet, we don’t really believe the people providing that care can take

Support Award for Ashley

leadership roles in the delivery of the service.”

Recent studies show almost 8 in every 10 Consultants are screening positive for burnout as they struggle to cope in an overstretched public hospital system where demand has outstripped supply.

Professor Muldoon says that this is the case across the entire health system as “those who we have tasked with caring for our most vulnerable” increasingly describe the management structure and use of performance indicators as “frustrating”.

Professor Muldoon says this also shows that far too much focus is being placed on counting performance indicators rather than on providing the capacity and resources for the delivery of essential services to patients.

“This model of using KPIs to identify areas of improvement works in the private, corporate sector, because those entities are given all sorts of resources to help achieve their targets. But in the public health system you have more people counting performance indicators, but no extra resources allocated to the actual care.”

New Hospital Pharmacy Medicine Shortage Survey

Medicines availability in the new year started very much as it ended in 2022. News outlets across Europe reported the increase in respiratory infections, in particular in children, leading to shortages of vital treatment options, including antibiotics. At the same time, healthcare professionals, patient representatives and notified bodies were ringing the alarm bells due to increasing concerns about medical device shortages.

Congratulations to Ashley Bazin, Team Leader on the Oncology & Haematology Clinical Trials with Tallaght University Hospital (TUH) who has been awarded the Irish Cancer Society Support Staff of the Year Award for 2023, in recognition of her contribution to driving forward Clinical Trials in TUH.

The Support staff of the Year Award recognises an individual who on a daily basis goes above and beyond the call of duty to support the cancer research being carried out across the country.

The PMI’s Annual Pharma Summit will be held on March 30th, 2023 at Croke Park

Five years passed since the last comprehensive investigation by the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) into the problem of medicine shortages. Since new data is vital – especially ahead of the upcoming revision of the general pharmaceutical legislation – EAHP has decided to launch a new Shortage Survey, this time looking at both the shortage of medicines and medical devices in the hospital environment.

The 2023 Shortage Survey, focused on medicinal products and medical devices, seeks to investigate the

reasons and impacts of shortages on patients in European hospitals as well as possible solutions. Besides hospital pharmacists, EAHP’s Survey targets other healthcare professionals working in hospitals, like nurses and physicians, as well as patients and their carers that have experienced medicine shortages during their hospital stay.

EAHP has been advocating on the issue of medicines shortages for more than a decade. Five surveys were conducted by EAHP in 2013, 2014, 2018, 2019 and 2020, with the last one focusing also on the pandemic preparedness of pharmacists. The results of these surveys have provided an overview of the severity of the problem as well as its impact on overall patient care.

Healthcare professionals and patients impacted by a medicine shortage during their treatment in a hospital are invited to provide feedback until 30 April 2023.

The theme for the day is “Partnering to Improve Human Health” and the event will be exploring this theme throughout the day from four vantage points: Technology, Government, Cross Company and Intra Company. The day will be highly interactive with a mix of keynote speakers and panel discussions with plenty of opportunities to catch up with industry colleagues and make new connections. Visit www.thepmi.com for further information.

4 MARCH 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Pharmacy Renews Memorandum of Understanding

Pictured are representatives from Beacon Hospital Pharmacy Department and the School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Science, RCSI as they renewed a Memorandum of Understanding

Last month, representatives renewed the Memorandum of Understanding between Beacon Hospital’s Pharmacy Department and RCSI School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences. Through collaboration and cooperation, Beacon Hospital and RCSI are mutually committed to the on-going development, delivery and promotion of a person-centred model of care for Pharmacy Practice in accordance with international best practice. The continued success of this collaborative partnership is based on the engagement, co-operation, good-will and mutual respect demonstrated by both Beacon Hospital Pharmacy Department and RCSI School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences. Both have effectively collaborated together previously and are committed to continuing this arrangement into the future.

Renewed Memorandum of Understanding

This agreement will provide for RCSI undergraduate pharmacy students to receive placementbased pharmacy education at Beacon Hospital to facilitate the development of clinical pharmacy knowledge.

Additionally the RCSI School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences will facilitate the

development of educational content and training programmes which will support the education of Pharmacy Staff Members in Beacon Hospital.

Similarly, through this agreement there will be opportunities for collaborative research between RCSI and Beacon Hospital. In particular this research will be directed at improving patient outcomes and experience, through enhancing the

underpinning pharmacy services at Beacon Hospital.

Academic Appointments

Catherine Nugent reappointed as Honorary Clinical Associate Professor at RCSI.

Keira Hall reappointed as Honorary Senior Lecturer at RCSI. Seamus Dunne and Hilary Ward new appointments as Honorary Clinical Lecturers at RCSI.

Future-Proofing the hospital pharmacy workforce

Healthcare workforce shortages are not a new phenomenon triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. They were simply exacerbated by it. Shortages of nurses or physicians in hospitals, particularly in rural areas are frequently featured in news outlets across Europe. However, not only these professions are affected but also the pharmacy workforce, including pharmacists, technicians and others. Especially those working in hospitals have to cope with staffing which is insufficient to meet patients' needs.

To address the problem of pharmacy workforce shortages, the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) and its members started an in-depth analysis of the situation in Europe. A workshop conducted with delegates from EAHP's member countries in June last year was followed by an Investigation of the Hospital Pharmacy Profession in Europe that closed in the first quarter of 2023. Touching

on the state-of-the-art of the profession and specifically on the European Statements of Hospital Pharmacy, the investigation collected information on their implementation, the size of the profession and other pharmacyspecific practice areas.

Scientific achievements for example in the field of advanced therapy medicinal products are leading to increasingly complex medication-related problems, specific handling and preparations and related issues. In addition, new competencies and tasks widened the scope of engagement of hospital pharmacists in multi-professional teams in the hospital setting and beyond. Medicines reconciliation, medication optimisation, bedside counselling or being part of the antimicrobial stewardship team are just a few of the clinical pharmacy services that should be provided to all patients across Europe by hospital pharmacists as part of the multidisciplinary care

team. To ensure the availability of these vital services a resilient workforce is required.

Other aspects requiring a futureproof pharmacy workforce are the increasing individualisation of care, growing medicine shortage problems requiring interventions by hospital pharmacists and supporting personnel, and rising healthcare costs. The latter can be addressed with the help of pharmacy expertise linked to the procurement of medicines and medical devices and health technology assessments (HTAs) but is also associated with a larger need for the workforce to handle often very specific needs of the patients. Another very important chapter for optimal patient outcomes and safety is the interface of care. Thus, the need for highly educated and specialised professionals in medication and medication-related processes that can ensure the seamless transfer of patients between healthcare settings is growing.

High-quality education in all European countries is of utmost importance for addressing the workforce problems of pharmacists to ensure that the profession remains an integral part of healthcare. Education needs to go hand in hand with hiring enough pharmacy personnel, including support staff, and finding the appropriate balance of training a sufficient number of students each year to robustly grow the pharmacy profession in each country.

For EAHP it is clearly time to act for patients in all countries around Europe. Concrete action that ensures a resilient and futureproof pharmacy profession by for example training an adequate number of students to fill the growing number of vacancies in clinical, community, hospital and industrial pharmacies is urgently needed. To address the workforce gaps, EAHP plans to put forward a new position paper on the hospital pharmacy workforce that proposes short and long-term measures.

5 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • MARCH 2023

News

Medicine Shortages Index at 247

“There’s an awareness in other European countries that market related factors need to be tackled. Medicines shortages are not just winter specific, and shortages are not only occurring as a result of exceptional circumstances. There are systemic factors that need resolution”

Medicine shortages in Ireland continue to persist with 247 different medicines used by Irish patients currently out-of-stock, as a new trend affecting supply develops, according to the latest Medicine Shortage Index.

The latest figures show the number of medicine shortages in Ireland up an additional 19 medicines in short supply since the end of last month, and a 38% increase since the Index began in October.

Of the 247 medicines currently unavailable, 13 are listed on the World Medical Organisation’s (WHO) ‘critical medicines’ list.

The latest shortages analysis indicates a new trend of medicines that are stored or delivered using plastic components now increasingly in short supply. These medicines include nasal sprays, inhalers for the treatment of asthma and 11 different eye drop products.

Other medicines still in short supply across multiple suppliers in the past week include those that treat epilepsy, and medicines used for the treatment of high blood pressure.

Many antibiotics like Amoxicillin and Penicillin and commonly used over-the-counter medicines like Benylin ™ and Dioralyte ™ are still difficult for patients to source.

The Medicine Shortage Index, prepared by industry experts, Azure Pharmaceuticals, analyses data made publicly available by the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA).

Other European countries have already taken specific policy measures to date in response to the escalating medicine shortage issue. Portugal, the UK, Germany, and Switzerland have all taken a range of price related policy measures in response to the problem, including price increases for lower priced medicines.

While, Sweden, Denmark and Malta, which all use tenders to set reimbursement prices, have all experienced price increases

due to lack of supply of core medicines. To date, the Irish Department of Health is yet to meaningfully respond to this deepening challenge.

Medicine shortages will continue grow incrementally unless political will is shown in Ireland to take measures, like those carried out by other EU nations, to meaningfully tackle the issue, Sandra Gannon, Azure CEO, said:

“One of the means we have to protect our domestic supply of stock, to prevent these important medicines from running out, is through pricing. Other European countries have already recognised this fact and taken measures to mitigate against situations where their stocks run out. For example, Portugal recently raised its pricing by up to 5% for cheap medicines.

“Weaknesses in the supply chain alone highlight the imperative of revisiting the pricing framework for medicines to protect supply of stock and protect Irish patients.”

Doctors encouraged to train in Ireland

Irish postgraduate medical colleges were in Dubai recently to discuss the large range of medical training opportunities in Ireland for doctors from the United Arab Emirates and the wider Gulf region. A new website www. postgraduatemedicaltraining.ie was launched by Her Excellency Ambassador Alison Milton, Irish Ambassador to the UAE, detailing Ireland’s clinical postgraduate training opportunities for doctors from across the GCC. It also shares information on relocation support and benefits of training in Ireland.

The clinical residency and fellowship programmes provided by Irish medical colleges are internationally recognised and fully certified. They offer handson supervised training, as well as opportunities for clinical research. Doctors from the UAE will have the opportunity to move to Ireland and learn from leading experts to develop the medical, communication, management and interpersonal skills required to provide world-class care and enhance the clinical environments in which they operate.

“The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland has strong links with the United Arab Emirates, partnering with healthcare organisations in the UAE to provide postgraduate medical training opportunities since 2013. These partnerships are highly valued by the College,” Professor Mary Horgan, President of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland said.

“Medical graduates from the United Arab Emirates make significant contributions to our medical teams. Graduates report

Commenting on the perception that medicine shortages are a result of exceptional circumstances and are a one-off situation, Ms Gannon pointed to the level of EU activity on the topic, as well as the focus of the European Medicines regulator (EMA) on medicine shortages as evidence that this problem is not going away without serious intervention and planning.

“There’s an awareness in other European countries that market related factors need to be tackled. Medicines shortages are not just winter specific, and shortages are not only occurring as a result of exceptional circumstances. There are systemic factors that need resolution.

“Each patient has different needs and reducing the problem down to exceptional circumstances alone diminishes the quality of life impact that each patient experiences with their illness.”

Medicine shortages experts from Europe and Ireland recently said in Dublin, at a panel discussion examining medicine shortages, that the situation will continue to worsen without the political will to implement measures that put the needs of patients first.

a very positive experience and, upon returning home to the UAE, they are in a strong position to advance their medical careers and contribute to the development of healthcare in the UAE. There are a growing number of fantastic opportunities for doctors from the UAE to come to Ireland for transformative postgraduate medical training across many specialties and this new website is a comprehensive resource for doctors to explore what’s available,” Prof Horgan said.

6 MARCH 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Positive Step to Faster Medicines Access

The decision by Minister for Health, Stephen Donnelly T.D. to publish the Mazars Report has been welcomed by the Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association as a positive step towards providing Irish patients with faster access to life-changing new medicines.

IPHA, which represents the major international biopharmaceutical companies in Ireland, commended the Minister’s decision to publish the report and to establish a Working Group to review and improve the reimbursement system for new medicines.

The organisation recognised that the initiative is the first of its kind since the passage of the Health (Pricing and Supply of Medical Goods) Act 2013, describing it as a valuable opportunity for key stakeholders, including industry and patient groups, to contribute to improved patient care and health outcomes.

IPHA said the Working Group’s role in reviewing and improving the reimbursement process was especially important considering

the many new advances in science and the potential to raise standards of patient care through faster access to newer and better medicines and treatments.

It applauded the Minister’s decision to act immediately to enhance transparency in the reimbursement system through the introduction of a tracker system and indicative timelines, stating that it would result in better planning and management of applications for medicine reimbursement.

IPHA said it welcomed the opportunity to engage in the Working Group, to present its own reform proposals and to hear the view of other stakeholders. It stated, “We will put forward ideas in good faith and will also listen to what is asked of us. Our members are very conscious of industry’s responsibilities to improve the process in a collaborative way.

We will:

• Bring forward proposals to support the further development of national medicines policy.

Child and Youth Mental Health Lead

• Present the case for an increase in personnel and IT resourcing for the HSE’s Corporate Pharmaceutical Unit, the HSE Drugs Group and the National CPE.

• Explore ways for earlier reimbursement for certain treatments, such as early access schemes, as is done in other countries. IPHA companies are ready with some rare disease, cancer and end-of-life treatments that can be pathfinders for this new approach in 2023 and 2024.

• Advocate for an increase in the HSE’s decision authority table thresholds and more generally for a well-structured commercial framework, as exists in other countries.”

IPHA said there were “many other practical steps that can be taken to improve the processes that

fully respect the HSE’s obligations under the 2013 Health Act. We will study the Mazars Report carefully and provide any observations arising from it to the Minister.”

Michael O’Connell, IPHA President said: “Over the past three budgets, the Government has allocated almost ¤100 million to new medicines. The announcement today is a further indication of the Minister’s continued commitment to ensure that patients have faster access to new, innovative medicines. I thank the Minister for driving this reform and bringing all stakeholders together in doing so”.

Minister for Mental Health and Older People Mary Butler welcomed the opening of the recruitment process for the post of Child and Youth Mental Health Lead in the HSE. This key new role will provide leadership, operational oversight, and delegated management of all service delivery across child and youth mental health services across the country. They will also be responsible for managing and coordinating service planning activities, partnership and capacity building, the development of service plans, and setting of service standards right across child and youth mental health services in Ireland.The post holder will report to the HSE National Director for Community Operations and will be supported by a dedicated team for which funding has been provided.

This role, and the wider Child and Youth Mental Health office, will result in improved links with the National Clinical Advisor Group Lead Mental Health, which in turn will support the development of current and future youth mental healthrelated National Clinical Programmes.

Minister Butler stated, “The progression of this role has been a key priority for me over the past year, and it will play a crucial part in ensuring that integrated mental health services for young people have a more centralised and evidence-based focus within the HSE. “We will see the completed reviews and audits arising from the Maskey Report, along with the Final Report of the Mental Health Commission on CAMHS later this year, which together will give us real time data never available before to support this new post. Importantly, there will be new support staff to underpin this welcome initiative. I will ensure that the HSE also progresses as quickly as possible the new post of National Clinical Lead for Youth Mental Health as announced in the Dáil over the last week.”

Pharmacy Role in Hygiene

Advice on hygiene given by pharmacies has widened from oral care to infection control measures, according to a report by the FIP Global Pharmaceutical Observatory (GPO) published last month.

A literature review found educating people on hygiene measures such as handwashing and disinfection to be a novel community pharmacy service during the pandemic. The FIP GPO also conducted a cross-country survey through five FIP member organisations (n=60).

More than half of the respondents reported that avoidance of respiratory, viral, communicable, and food and water borne infections were the most common “germ concerns” expressed to them by the public. The study also looked into current and future learning needs of pharmacy teams.

The findings from the literature review showed that the concept of providing hygiene care advice has been differently shaped preand post-COVID times. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the

area of focus was limited to oral hygiene. All studies reviewed in the literature reinforced the vital role of community pharmacists as the public’s first choice of healthcare provider in mitigating the spread of the disease as well as their prominent contribution to overall emergency management.

There was also an unequivocal need to support, train and educate community pharmacists and their teams to improve their knowledge because the concept of increasing personal hygiene awareness

is a focus area of community pharmacists in developed and developing countries.

The report states, “As evidenced throughout this report, community pharmacists and their teams can play a leading role in providing reliable recommendations and educating patients on health hygiene, engaging and empowering patients in self-care, and minimising the spread of contagious diseases, ultimately contributing to improving our communities’ overall health.”

7 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • MARCH 2023

News

IPHA President Michael O’Connell

Blood Pressure Monitoring outside Hospital

The European Union has awarded a European consortium ¤4.4million for the SMARTSHAPE project to focus on developing an implantable medical device for continuous blood pressure monitoring.

Hypertension is the leading global contributor to premature death, accounting for more than 9 million deaths a year. Elevated blood pressure is a chronic lifetime risk factor that can lead to serious cardiovascular events if undiagnosed or poorly controlled. Many high-risk patients require long-term monitoring to tailor drug treatments and improve healthcare outcomes, but there is no clinically accepted method of continuous beat-to-beat blood pressure

monitoring that patients can use outside of the hospital setting.

The SMARTSHAPE consortium is led by Professor William Wijns, a Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) funded Research Professor in Interventional Cardiology at University of Galway’s College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences.

According to Professor Wijns, “The best innovations start with a clinical need. Patients who require monitoring are better off in their own homes rather than in a hospital setting. There is a huge market opportunity for a medicalgrade, user-friendly, and minimally invasive solution for continuous blood pressure monitoring.”

Professor Wijns is also a Funded Investigator at CÚRAM, the SFI research centre for medical devices based at University of Galway which focuses on developing biomedical implants, therapeutic and diagnostic devices that address the needs of patients living with chronic illness.

Dr Atif Shahzad, joint director of the Smart Sensors Lab at the University of Galway and a research fellow at the Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research at the University of Birmingham, said: “Our SMARTSHAPE consortium has developed an IP-protected technologically disruptive sensor for continuous

pressure measurement. There are challenges related to biocompatibility, longevity, and delivery to the target tissue, and these need to be overcome to deliver the sensor to the market.”

Dr Shahzad added: “This project will address these challenges by formulating an innovative biomaterial: a novel temperaturedependent shape memory polymer (SMP). SMPs will enable the development of a microsensor that can be curled up, introduced into the body through a minimally invasive procedure, and ‘opened up’ when placed at body temperature to take a predefined shape.”

Experts Call for National Life Sciences Strategy to Improve Irish Patient Care

Michael O’Connell, Country Director, Biogen, Mairead McCaul, MSD, Michael O’Connell, IPHA, Brenda Dooley, AXIS Consulting, and Matt Moran, BioPharmaChem, shared key insight on ongoing trends in the pharmaceutical sector

Technology Assessments (HTA) to be made on new medicines; much longer than in other jurisdictions such as Scotland, which is between 6 and 12 months.

Panel of Guaranteed Irish pharmaceutical experts call on Government and key stakeholders to collaborate to achieve more timely access to medicines for Irish patients.

The Annual Guaranteed Irish Pharmaceutical Forum, hosted by Guaranteed Irish featured an industry leading line-up within the pharmaceutical sector. The panel discussion featured industry thought leaders Mairead McCaul Managing Director of MSD Ireland Human Health, Matt Moran Director of BioPharmaChem Ireland, Ibec, Brenda Dooley CEO AXIS Consulting and Michael O’Connell Country Director of Biogen and President of the Irish Pharmaceutical Healthcare Association (IPHA). The attendees included more than 100 registrations from pharmaceutical businesses across the country.

Industry Successes to Date

The panel outlined Ireland’s position as a major global player in pharmaceutical production, employing over 30,000 people in Ireland directly, and a further 30,000 indirectly, with Irish exports exceeding ¤100 billion. Ireland is now the largest net exporter of pharmaceuticals in the EU accounting for over 50% of all exports from the country and is one of the main hubs of manufacturing pharmaceuticals and biopharmaceuticals in the world, with 24 of the 25 global leaders in the industry based in Ireland.

Current Industry Challenges

While Ireland is a global leader in the pharmaceutical industry, timely access to medicines in Ireland is a concern. Periods of up to 2.5 years are the norm for full Health

Resourcing, and the availability of resources to evaluate medicines is a factor in the delayed reimbursement of medicines. As we move to an era of ever-more complex medicines, innovations, Gene & Cell Therapy (GCT) and potential cures; without regular and important conversations between Government, key stakeholders and industry leaders, Ireland is likely to be left behind on the global stage, as will patients. A robust system is needed to ensure the cost effectiveness of new innovations are affordable to both the state and the consumers. The panel of experts also highlighted the challenges facing the industry including talent retention and building a workforce for the future of pharma in Ireland, including tackling the ever-present problem of training educators to help them prepare the next generation for skillsets which may not exist yet.

Future Industry Opportunities

The panel also discussed the need for a life sciences strategy

for Government, stating that 18 of the 20 biggest life sciences manufacturers in the world operate here in Ireland, and that some of these companies in the reimbursement process are finding it difficult to get their innovations to patients in reasonable timeframes. Timely patient access to medicines should be a primary goal of any Government and Health Minister, regardless of political stance or party allegiance. As of January 2023, there is no firm life sciences strategy from Government which incorporates medicines and patient access to medicines.

Panel Call to Government

1. Timely patient access

2. Commitment to development of life sciences strategy

3. Providing additional resources to evaluate and reimburse medicines quickly

4. Attract R&D and clinical trials to Ireland as a boutique destination with experience in the pharmaceutical industry

Finally, Mairéad McCaul, Managing Director of MSD Ireland Human Health, praised Guaranteed Irish, acknowledging the role the organization plays in promoting Ireland and facilitating networking opportunities for likeminded industry experts and leaders to share ideas and create new key relationships, and position Ireland as an ideal location for further pharmaceutical investment.

8 MARCH 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Sharing Visions in Stroke Care

The first in-person conference to focus on ‘The vision for a comprehensive stroke care pathway in Ireland’ was hosted by the iPASTAR (Improving Pathways for Acute Stroke and Rehabilitation) programme at the RCSI Education and Research Centre, Beaumont Hospital.

iPASTAR is a collaborative doctoral training award funded by the Health Research Board Collaborative Doctoral Awards Programme, and hosted by RCSI and UCD.

The conference brought together healthcare professionals, academics, Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) partners and key stakeholders to celebrate the European Stroke Organisation (ESO) accreditation of the Stroke Service at Beaumont Hospital as a comprehensive stroke centre and present iPASTAR team’s vision for comprehensive stroke care pathway in Ireland.

The new Beaumont stroke unit is the first in Ireland and the UK to be awarded the prestigious ESO accreditation.

Commenting on the success of the event, Professor Frances Horgan, iPASTAR lead and Professor at the School of Physiotherapy, RCSI, said, “The discussions at the symposium today have encompassed the collaborative, co-designed approach that iPASTAR aims to achieve. Bringing clinicians, academics and patients together to address the challenges and opportunities in stroke care will enable us to make positive, evidence-based changes, optimising the patient pathway.”

A ‘design sprint’ workshop preceded the conference where

participants heard from the PPI partners in the project, including the perspectives from a stroke survivor on their experience of life after stroke and being involved in iPASTAR and discussed an ‘ideal’ stroke pathway, from acute care,

Date for your Diary

transition to home to living well and healthy after stroke.

During the symposium, iPASTAR PhD research scholars Dr Deirdre McCartan, Geraldine O’Callaghan, Patricia Hall and Clare Fitzgerald

RCSI Centre for Professionalism in Medicine and Health Sciences, supported by the Bon Secours Health System (Lead Sponsor) and Medical Protection Society are delighted to announce the date for their annual conference:

Professionalism: The Cost of Caring

Join them on the 28th April 2023 for a day of exciting talks and presentations. This year they are delighted to host a hybrid (online and in person) event which gives you the opportunity to participate and engage with our conference, no matter where you are in the world.

presented an update on their PhD projects, which focus on delivery of integrated stroke care for patients, from the hospital, to rehabilitation in the community, and living well after stroke.

The event focuses on Medical Professionalism and promises to be a great day of exciting talks and presentations from an international panel of speakers from Canada, USA, Australia, UK, UAE and Ireland! Joined by colleagues such as Johanna Westbrook from University of Sydney, Colin West from the Mayo Clinic and Yvonne Steinert from McGill, Dr Henry Marsh of “Do No

Registration for the online event is FREE! Please note there is a nominal fee to attend in person 5 CPD points.

Registration Link - https://bit.ly/MedProf23Registration

Put the date in your diary and register now. Don’t forget to follow on Twitter and use #MedProf23

9 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • MARCH 2023

News

Ian Carter, CEO, RCSI Hospital’s Group; Prof. Fergal O’Brien, Deputy Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation, RCSI; Prof. Frances Horgan, Profesith

Harm” fame, amongst many others.

Urology Congress

History Congress to offer ‘Inspiration and Perspective’

EAU23 will be held in Milan March 10th-13th, 2023

“For a fresh perspective, several non-urologists will be participating including the prolific Belgian author Kristien Hemmerechts. The role of women in urology and the EAU in particular is of course a very current debate. The number of female urologists is increasing, but their involvement in the EAU’s offices and boards is still lacking. We think it’s very important to focus on role of women in urology and by extension the EAU and we think Mrs. Hemmerechts can provide a feministic point of view on the challenges for women in medicine or professional organisations.

The EAU History Office is hosting another edition of the International Congress on the History of Urology to coincide with EAU23 and to mark the end of the EAU’s 50th Anniversary year. On 10 March 2023, the first day of EAU23 in Milan, there will be a full-day programme subtitled ‘Paradigm Shifts in Urology: 50 Years of Major Developments’. The History Congress will examine some highlights in urology that coincide with the EAU’s five decades of excellence. The selected speakers are experts in their respective fields, including medical pioneers and key figures from EAU history.

The two chairs of the Congress, History Office chairman Prof. Philip Van Kerrebroeck (Antwerp, BE) and his predecessor Prof. Dirk Schultheiss (Giessen, DE) give a preview of some of the themes and topics that will be covered.

Celebrating uniqueness of urology

The EAU conference organisers state, “It’s important to realise that urology is one of the few subspecialties within surgery that was able to retain diagnostics and the conservative part of treatment. Most other fields within surgery have an equivalent within internal medicine. Gastroenterological surgeons, have gastroenterologists, cardiac surgeons have the cardiologists, and so on. Within the field of urology, this has never been the case. This has historical reasons: the development of specific techniques like endoscopy that urologists always kept for themselves.

“If you talk to younger colleagues about why they want to become urologists, this is one reason they give: urology is not only dealing with surgical aspects but also the conservative and diagnostic aspects in terms of therapy. You see a patient from diagnostics to therapy and often beyond.

A half-century

“The general theme of the History Congress is the development of urology over the last 50 years, divided by subspecialty. First of all, this congress marks the end of the EAU’s anniversary celebrations that started at EAU22 and we wanted to highlight what happened in urology in the EAU’s lifetime. Secondly, we wanted to illustrate how much has changed in our field in only 50 years. It’s amazing: if you look how urologists worked, in case of diagnostics and therapies, it’s completely different. Some elements have persisted but there are so many more new modalities or older modalities that have been transformed.

“All medical specialties have had huge developments since the early 1970s, but in urology perhaps there were more dramatic changes. Even over the course of our careers, the amount of open surgery for kidney stones, or for instance cases of horseshoe kidney, have now almost completely been eradicated. The advent of laparoscopic and robotic techniques have even more reduced the need for open surgery and this trend was adopted particularly quickly in urology. Urodynamics

has become digitalized and computerised. Urology can also be seen as a pioneer in the development of prosthetics, for instance in sphincter and penile prostheses, and in the development of neuromodulation in functional problems.

“Reviewing 50 years is not only a review of what we achieved, but also of what was not achieved, or still problematic, or even new problems we created. Looking at sexual reassignment surgery, what was completely normal only 20 years ago is already considered outdated or ridiculous.

A chance to meet pioneers

“Because the programme is focused on the past 50 years, it also allows us to invite people who ‘wrote history’ in this period. Prof. Patrick Walsh is joining us from the United States to talk about his role in the discovery of nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. His work in the 1970s and 1980s caused a shift in the thinking around radical prostatectomy. Another big name from the history of our field is Prof. Tony Mundy, leading expert in urethral strictures who will undoubtedly share a great historic overview of his expertise.

“The programme is organised around a variety of important subspecialties and feature some provocative and conversationstarting sessions. It will be chaired by members of the EAU History Office and also the EAU Board. The programme will be unique in that we will have four of the EAU’s (former) Secretary Generals taking part in some capacity. We will have speakers from all across the world, young and old.

Inspiration and perspective

“We always hope that participants take away a new consideration for their work. History can be humbling! We also think the programme and speakers will offer inspiration that will help our colleagues in their daily practice from the next day on. That’s what sets us apart from other professions: medicine requires an inspiration: empathy, individual contact, psychological aspects at every level, and the focus on the patient. That’s what a congress like ours can offer.”

The International Congress on the History of Urology is free to attend for all EAU23 delegates and requires no separate registration. It replaces the History Office’s usual “Special Session” but its Poster Session will be held as usual.

10 MARCH 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

50mgs once daily

BETMIGA 25 mg prolonged-release tablets & BETMIGA 50 mg prolonged-release tablets.

Prescribing Information: BETMIGA™ (mirabegron)

For full prescribing information, refer to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC). Name: BETMIGA 25 mg prolonged-release tablets & BETMIGA 50 mg prolonged-release tablets. Presentation: Prolongedrelease tablets containing 25 mg or 50 mg mirabegron. Indication: Symptomatic treatment of urgency, increased micturition frequency and/or urgency incontinence as may occur in adult patients with overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome. Posology and administration: The recommended dose is 50 mg orally once daily in adults (including elderly patients). Mirabegron should not be used in paediatrics for OAB. A reduced dose of 25 mg once daily is recommended for special populations (please see the full SPC for information on special populations). The tablet should be taken with liquids, swallowed whole and is not to be chewed, divided, or crushed. The tablet may be taken with or without food. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients listed in section 6.1 of the SPC. Severe uncontrolled hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 180 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 110 mm Hg. Warnings and Precautions: Renal impairment: BETMIGA has not been studied in patients with end stage renal disease (eGFR < 15 ml/min/1.73 m2 or patients requiring haemodialysis) and, therefore, it is not recommended for use in this patient population. Data are limited in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR 15 to 29 ml/min/1.73 m2); based on a pharmacokinetic study (see section 5.2 of the SPC) a dose of 25 mg once daily is recommended in this population. This medicinal product is not recommended for use in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR 15 to 29 ml/min/1.73 m2) concomitantly receiving strong CYP3A inhibitors (see section 4.5 of the SPC).

Hepatic impairment: BETMIGA has not been studied in patients with severe hepatic impairment (ChildPugh Class C) and, therefore, it is not recommended for use in this patient population. This medicinal product is not recommended for use in patients with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh B) concomitantly receiving strong CYP3A inhibitors (see section 4.5 of the SPC). Hypertension: Mirabegron can increase blood pressure. Blood pressure should be measured at baseline and periodically during treatment with mirabegron, especially in hypertensive patients. Data are limited in patients with stage 2 hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mm Hg). Patients with congenital or acquired QT prolongation: BETMIGA, at therapeutic doses, has not demonstrated clinically relevant QT prolongation in clinical studies (see section 5.1 of the SPC). However, since patients with a known history of QT prolongation or patients who are taking medicinal products known to prolong the QT interval were not included in these studies, the effects of mirabegron in these patients is unknown.

Caution should be exercised when administering mirabegron in these patients. Patients with bladder outlet obstruction and patients taking antimuscarinics medicinal products for OAB: Urinary retention in patients with bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and in patients taking antimuscarinic medicinal products for the treatment of OAB has been reported in postmarketing experience in patients taking mirabegron. A

controlled clinical safety study in patients with BOO did not demonstrate increased urinary retention in patients treated with BETMIGA; however, BETMIGA should be administered with caution to patients with clinically significant BOO. BETMIGA should also be administered with caution to patients taking antimuscarinic medicinal products for the treatment of OAB. Interactions: Caution is advised if mirabegron is co-administered with medicinal products with a narrow therapeutic index and significantly metabolised by CYP2D6. Caution is also advised if mirabegron is co-administered with CYP2D6 substrates that are individually dose titrated. In patients with mild to moderate renal impairment or mild hepatic impairment, concomitantly receiving strong CYP3A inhibitors, the recommended dose is 25 mg once daily. For patients who are initiating a combination of mirabegron and digoxin (P-gp substrate), the lowest dose for digoxin should be prescribed initially (see the SPC for full prescribing information). The potential for inhibition of P-gp by mirabegron should be considered when BETMIGA is combined with sensitive P-gp substrates. Increases in mirabegron exposure due to drug-drug interactions may be associated with increases in pulse rate. Pregnancy and lactation: BETMIGA is not recommended in women of childbearing potential not using contraception. This medicinal product is not recommended during pregnancy. BETMIGA should not be administered during breast-feeding. Undesirable effects: Summary of the safety profile: The safety of BETMIGA was evaluated in 8433 adult patients with OAB, of which 5648 received at least one dose of mirabegron in the phase 2/3 clinical program, and 622 patients received BETMIGA for at least 1 year (365 days). In the three 12-week phase 3 double blind, placebo controlled studies, 88% of the patients completed treatment with this medicinal product, and 4% of the patients discontinued due to adverse events. Most adverse reactions were mild to moderate in severity. The most common adverse reactions reported for adult patients treated with BETMIGA 50 mg during the three 12-week phase 3 double blind, placebo controlled studies are tachycardia and urinary tract infections. The frequency of tachycardia was 1.2% in patients receiving BETMIGA 50 mg. Tachycardia led to discontinuation in 0.1% patients receiving BETMIGA 50 mg. The frequency of urinary tract infections was 2.9% in patients receiving BETMIGA 50 mg. Urinary tract infections led to discontinuation in none of the patients receiving BETMIGA 50 mg. Serious adverse reactions included atrial fibrillation (0.2%). Adverse reactions observed during the 1-year (long term) active controlled (muscarinic antagonist) study were similar in type and severity to those observed in the three 12-week phase 3 double blind, placebo controlled studies. Adverse reactions: The following list reflects the adverse reactions observed with mirabegron in adults with OAB in the three 12-week phase 3 double blind, placebo controlled studies. The frequency of adverse reactions is defined as follows: very common (≥ 1/10); common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10); uncommon (≥ 1/1,000 to < 1/100); rare (≥ 1/10,000 to < 1/1,000); very rare (< 1/10,000) and not known (cannot be established from the available data). Within each frequency grouping, adverse reactions are presented in order of decreasing seriousness. The adverse events are grouped by MedDRA system organ class. Infections and infestations:

Common: Urinary tract infection, Uncommon: Vaginal infection, Cystitis. Psychiatric disorders: Not known (cannot be estimated from the available data): Insomnia*, Confusional state*. Nervous system disorders:

Common: Headache*, Dizziness*. Eye disorders: Rare: Eyelid oedema. Cardiac disorders: Common: Tachycardia, Uncommon: Palpitation, Atrial fibrillation. Vascular disorders: Very rare: Hypertensive crisis*. Gastrointestinal disorders: Common: Nausea*, Constipation*, Diarrhoea*, Uncommon: Dyspepsia, Gastritis, Rare: Lip oedema. Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders: Uncommon: Urticaria, Rash, Rash macular, Rash papular, Pruritus, Rare: Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, Purpura, Angioedema*. Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders: Uncommon: Joint swelling. Renal and urinary disorders: Rare: Urinary retention*. Reproductive system and breast disorders: Uncommon: Vulvovaginal pruritus. Investigations: Uncommon: Blood pressure increased, GGT increased, AST increased, ALT increased. * signifies adverse reactions observed during post-marketing experience. Prescribers should consult the SPC in relation to other adverse reactions. Overdose: Treatment for overdose should be symptomatic and supportive. In the event of overdose, pulse rate, blood pressure, and ECG monitoring is recommended. Basic NHS Cost: Great Britain (GB)/Northern Ireland(NI): BETMIGA 50 mg x 30 = £29, BETMIGA 25 mg x 30 tablets = £29. Ireland (IE): POA. Legal classification: POM. Marketing Authorisation number(s): (GB): PLGB 00166/0415-0416. NI/IE: EU/1/12/809/001-006, EU/1/12/809/008-013, EU/1/12/809/015018. Marketing Authorisation Holder: GB: Astellas Pharma Ltd., 300 Dashwood Lang Road, Bourne Business Park, Addlestone, United Kingdom, KT15 2NX. NI/IE: Astellas Pharma Europe B.V. Sylviusweg 62, 2333 BE Leiden, The Netherlands. Date of Preparation of Prescribing information: January 2023. Job bag number: MAT-IE-BET-2023-00001. Further information available from: GB/NI: Astellas Pharma Ltd, Medical Information: 0800 783 5018. IE: Astellas Pharma Co. Ltd., Tel.: +353 1 467 1555. For full prescribing information, please see the Summary of Product Characteristics, which may be found at: GB: www.medicines.org.uk; NI: https://www.emcmedicines.com/en-GB/northernireland/; IE: www.medicines.ie.

United Kingdom (GB/NI)

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store. Adverse events should also be reported to Astellas Pharma Ltd. on 0800 783 5018. Ireland

Adverse events should be reported. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions via: HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Website: www.hpra.ie or Astellas Pharma Co. Ltd. Tel: +353 1 467 1555, E-mail: irishdrugsafety@astellas.com.

Date of preparation: January 2023 References: 1. Freeman R, et al. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2017.1419170. MAT-IE-BET-2023-00003

His 14th walk in the park since the day he started BETMIGA1

First ‘Incisionless’ surgery for Achalasia

Galway University Hospitals (GUH) has become the first hospital in Ireland to introduce an ‘incisionless’ minimally invasive surgery to help correct blockages of the oesophagus.

Achalasia is a rare condition which causes a blockage in the muscles of the lower oesophagus causing dysphagia or difficulty in swallowing, including in pronounced cases, liquids.

The procedure was carried out by Mr Paul Carroll, Consultant Oesophagogastric and General Surgeon, specialising in minimally invasive surgery and endoscopic

surgery for oesophago-gastric cancer and benign disease.

Traditionally, treatment of Achalasia involves procedures to repeatedly dilate/open the oesophagus or, alternatively, requires laparoscopic surgery. The traditional surgery divides the muscles of the lower oesophagus through several small incisions in the abdomen.

However, surgeons in GUH have now undertaken an incisionless procedure using Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM). POEM uses an endoscope, a narrow flexible tube with a

camera, to breach the lining of the oesophagus. The endoscope is inserted through the mouth and can be positioned into the space between the oesophageal lining and the muscles, allowing it to divide these muscles internally. The breach is then closed with special clips.

One of the significant benefits of this procedure is the ability to treat a subtype of achalasia with chest pain. This requires a longer division of the muscles along the length of the oesophagus, which is traditionally challenging to treat with standard surgery. POEM can also be used as a

Cross Border Network for Rare Diseases

University College Dublin (UCD), Queen’s University Belfast, and 33 partners launched the All-Ireland Rare Disease Interdisciplinary Research Network (RAiN).

Individual rare diseases may be rare but collectively impact more than 400,000 people across the island of Ireland. There are as many people living with rare diseases across Ireland as live with diabetes, yet rare diseases receive much less recognition and support.

Many people living with a rare disease experience chronic debilitating illness, with more than 30 percent of children with rare diseases dying before their fifth birthday. RAiN will help evaluate the quality of life and management of people living with

rare diseases on the island of Ireland and internationally.

Co-lead of RAiN for UCD, Associate Professor Suja Somanadhan said, “This all-Island interdisciplinary rare disease research network will serve as a hub to support collaboration and connection between members across the Island, which includes researchers, early career investigators, industrial partners and Public and Patient Involvement expert groups.”

Co-lead of RAiN for QUB, Professor Amy Jayne McKnight added, “I’m delighted that so many individuals in our local rare disease community have come together to establish this network and look forward to working in partnership with those working, often on a shoestring budget, to improve the lives of people living with rare diseases.”

Officially launching the network, Vice President for Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion at UCD Professor Colin Scott said: “People living with rare disorders face significant health and social inequalities. The All-Island interdisciplinary rare disease research network helps ‘level up’ the rare disease community across Ireland. I am delighted to launch this unprecedented collaborative approach led by UCD and QUB with government, local authority, charity, patient and caregiver partners across Ireland.”

RAiN is funded by the Department of the Taoiseach from the Shared Island strand of Irish Research Council’s ‘New Foundations’ awards. The network builds on established

rescue or second line intervention where other treatments have failed. Patients are discharged the following morning without pain and with resolution of symptoms. The introduction of this procedure has added to the expanding Minimally Invasive Upper GI programme in Galway and the Saolta University Health Care Group, which also provides endoscopic surgical interventions for early oesophageal and gastric cancers. GUH is one of only two centres in Ireland with this capability.

Mr Paul Carroll, Consultant Oesophagogastric and General Surgeon at Galway University Hospitals thanked his team for their support in bringing the procedure to Irish patients. “I am personally delighted that I have been able to introduce this procedure into Ireland for treatment of this disease process. It would not have been possible without the support and training I received whilst on fellowship in the University of Toronto and finally without the unwavering support of the late Marie Farragher, Clinical Nurse Manager in theatre and her team of nurses for pushing boundaries with me,” he added.

north-south research partnerships between UCD and Queen’s*. By fostering collaboration among researchers, practitioners, policymakers, patients and families working on rare diseases, RAiN will advance health service developments, leverage funding, and facilitate internationally excellent translational rare disease research.

Monthly seminars will discuss research that addresses the significant unmet health, social, psychological, and educational needs of children, young people affected by rare disease and their families. Nurtured research partnerships will inspire and empower early career researchers as emerging leaders for interdisciplinary rare disease research.

12 MARCH 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

News

From Left, Máire Cooper, Theatre Staff Nurse; Noreen Keelan, Senior Anaesthetic Staff Nurse; Paul Carroll, Consultant Oesophagogastric and General Surgeon; Ashitosh Waidande, CNM 2, GI Theatre; and Deirdre Hoade, Senior Staff Nurse, Theatre

Liver Cancer

Primary liver cancers with a focus on Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Written by

Written by

Introduction

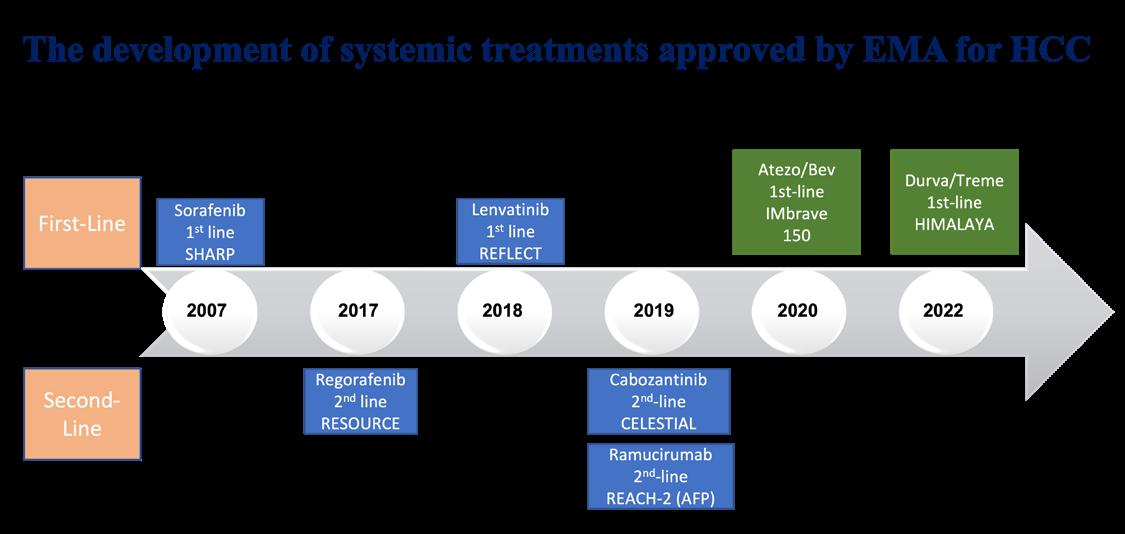

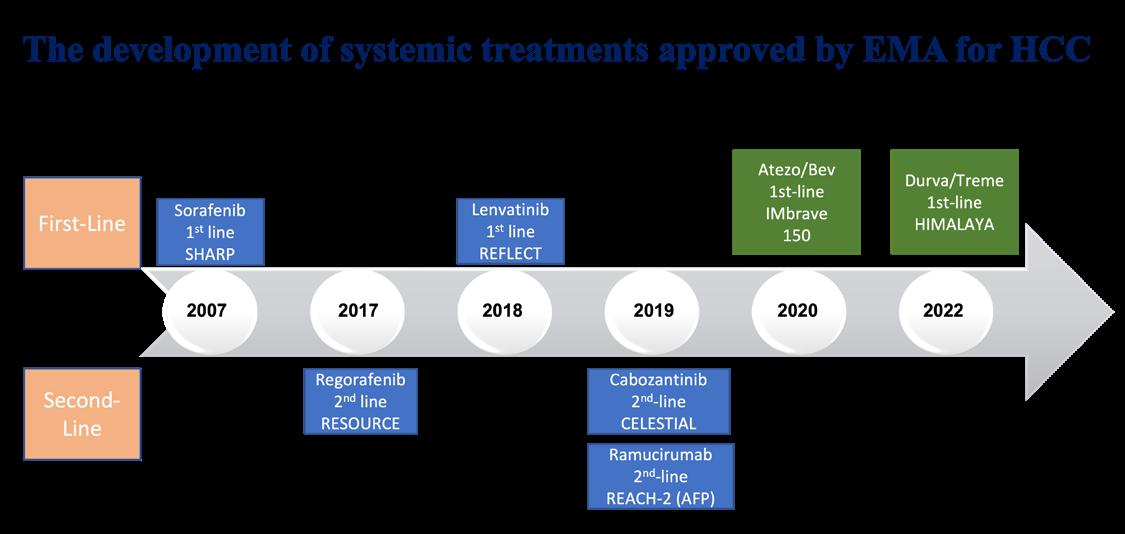

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma represent the most common forms of liver cancer with the former accounting for over 80% of cases1 . Cholangiocarcinomas arise from the bile ducts and will not be discussed in this article however should be highlighted as a rising cause of liver cancer. Indeed the numbers of new cases and deaths from liver cancer are expected to increase by more than 55% by 20401. This highlights the urgent need for national strategies and international collaboration to deal with this impending disease burden. The management of HCC has seen remarkable changes in the past 5 years. Up until 2017 sorafenib was the only drug available to patients with advanced HCC. We now have two new standard immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) combinations in the first line setting, demonstrating superiority over sorafenib while lenvatinib represents a further oral therapy. A number of additional oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors have shown benefit in the second line setting. It is now inevitable that these agents will be integrated earlier in the management of HCC, with trials in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting ongoing. How countries will cope with the cost of these new therapies has not been addressed and highlights continued global disparities in cancer care.

Epidemiology

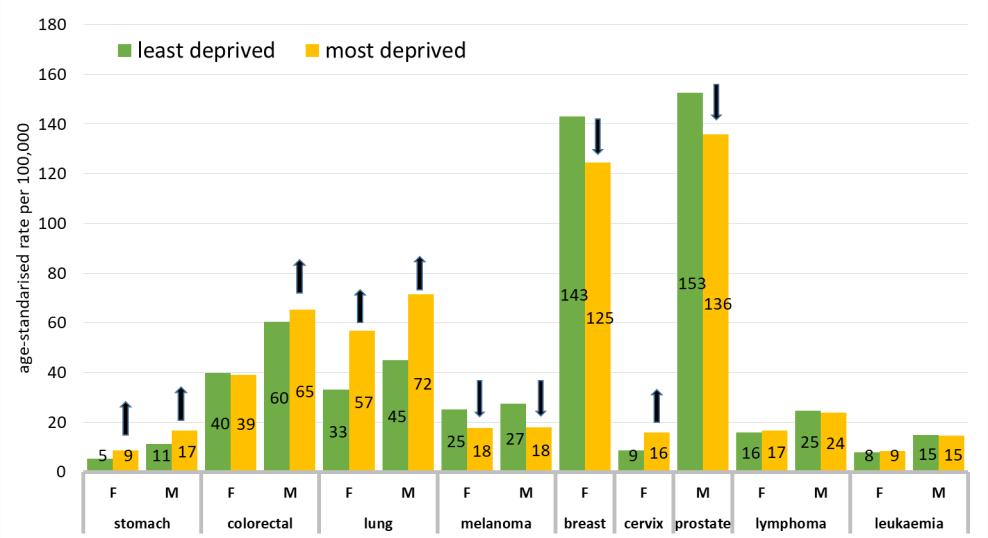

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the 3rd most common cause of cancer related mortality world-wide with an estimated 5 year survival rate of 18%. The majority of HCC arise on a background of chronic liver disease with 80-90% of patients having underlying liver cirrhosis. HCC most commonly occurs in the 6th decade and occurs more frequently in males. The spectrum of underlying liver disease varies globally with a predominance of hepatitis B and C in Asia while alcohol and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) dominate in Western Societies. Less common causes of HCC include haemochromatosis, alpha-1antitrypsin deficiency and drug induced liver injury.

Notably there has been a rise in the incidence of HCC in Ireland and Europe due to obesity and the prevalence of fatty liver

disease while levels of alcohol consumption remain high 2. Europe has the highest levels of alcohol intake in the world3, while NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are predicted to become the leading cause of end stage liver disease 4. Excessive alcohol use, obesity and diabetes are risk factors for HCC that require urgent public health strategies.

Prevention and screening

Globally, the advent of hepatitis B vaccination, has together with the development of antivirals agents for hepatitis C resulted in a decline in viral associated HCC highlighting effective prevention strategies. NAFLD and progression to NASH is inextricably linked to obesity and diabetes and is largely due to modern Western diets enriched in excess sugars and fats together with a more sedentary lifestyle. Smoking may contribute to HCC risk particularly in the presence of other risk factors while aspirin and coffee have been found to be protective5 6. The risks of alcohol and liver cirrhosis are well known , however tackling the issues of obesity and excessive alcohol consumption will require significant cultural changes and government intervention. The EASL-Lancet liver commission have provided recommendations on achieving healthier livers for all Europeans underscoring the need for multi-disciplinary input and national policies 7 The prevention of chronic liver disease will represent one of the most effective ways in reducing mortality from HCC.

Earlier detection of HCC is further critical, particularly as management strategies evolve. International guidelines and liver societies recommend surveillance of high risk populations using ultrasound with or without alpha fetoprotein (AFP)8. Its noteworthy that not everyone with liver disease or indeed cirrhosis will develop HCC. Nevertheless HCC when detected early is highly curable. Ultrasound screening in the presence of obesity can be challenging and the role of AFP in screening has been controversial. Novel strategies such as a liquid biopsy or a blood test to evaluate cell free circulating tumour DNA will likely become part of screening protocols in the future.9

Making a Diagnosis and staging HCC

HCC is unusual compared to other cancers in that a diagnosis can be made without a biopsy confirming histology. Liver imaging with a CT or MRI in the setting of chronic liver disease reveals characteristic features of tumour enhancement which is specific for HCC. However not all HCC will have such obvious characteristics on CT or MRI and as such the liver imaging reporting and data system (LI-RADS, LR) was developed for radiology reporting without need for a biopsy. This is an important point so that registries adequately capture the burden of HCC that exists if pathology has not been obtained. The role of biopsy of early lesions has been controversial because of concerns with regard to seeding. Biopsy however is increasingly being employed especially as systemic therapies are being used before surgery or transplant. Furthermore it has been demonstrated that imaging alone wrongly calls 9% of cases labelled as HCC in the advanced setting. This would mean inappropriate treatments in those patients10

The staging of HCC is integral to prognosis and management and the Barcelona Clinic Liver Criteria (BCLC) staging system is the most widely used. While the tumour burden and presence of portal vein invasion and or extrahepatic disease is critical to staging, equally important is the assessment of liver function and the consideration of patient

performance status11. BCLC classifies HCC into very early stage (BCLC 0), early stage (BCLC A), intermediate stage (BCLC B), advanced stage (BCLC C) and terminal stage (BCLC D).

Curative options BCLC 0, A and B

BCLC 0 and A HCC should be considered for curative options including surgical resection, transplant and ablation. Resection is ideal for single lesions where liver function is preserved. In patients where there is multifocal disease or where there is decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant is a potential option. Surgical considerations in the presence of cirrhosis are complex and all eligible patients should be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting at a high volume centre. Liver transplantation in eligible patients has a 5 year survival rate of 75-80%12. Liver transplantation has the advantage of treating underlying liver cirrhosis while providing the widest possible surgical margin. Most commonly the Milan Criteria13 are used to select patients considered eligible for liver transplant. These criteria (one lesion ≥ 2 cm and ≤ 5 cm, or up to 3 lesions, each ≥ 1 cm and ≤ 3 cm, with no evidence of vascular invasion or extra-hepatic metastases) are today in many centres considered too restrictive and downstaging protocols will seek to employ locoregional or systemic therapies to render patients beyond Milan criteria eligible. This accepts that tumour biology is superior to size