Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication

IN THIS ISSUE:

NEWS: Revised Pay for Hospital Pharmacists

Page 6

REPORT:

Medicines Shortages reaching ‘Critical’ Point Page 9

CONFERENCE: 58th IACR Annual Conference

Page 14

Med. 2020;382(6):514-524.

4. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Breast Cancer V.4.2022. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2021. All rights reserved. Published June 21, 2022. Accessed July 29, 2022. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

ABBREVIATED PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

Please refer to Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing.

Kisqali (ribociclib) 200 mg film-coated tablets

Presentation: Film coated tablets (FCT) containing 200 mg of ribociclib and 0.344 mg soya lecithin.

Indications: Kisqali is indicated for the treatment of women with hormone receptor (HR) positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with an aromatase inhibitor or fulvestrant as initial endocrine-based therapy, or in women who have received prior endocrine therapy

In pre or perimenopausal women, the endocrine therapy should be combined with a luteinising hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist.

Dosage and administration:

Adults: The recommended dose is 600 mg (3 x 200 mg FCT) taken orally, once daily for 21 consecutive days followed by 7 days off treatment, resulting in a complete cycle of 28 days.

Kisqali should be used together with 2.5 mg letrozole or another aromatase inhibitor or with 500 mg fulvestrant.

When Kisqali is used in combination with an aromatase inhibitor, the aromatase inhibitor should be taken orally once daily continuously throughout the 28 day cycle. Please refer to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) of the aromatase inhibitor for additional details.

When Kisqali is used in combination with fulvestrant, fulvestrant is administered intramuscularly on days 1, 15 and 29, and once monthly thereafter. Please refer to the SmPC of fulvestrant for additional details.

Treatment of pre and perimenopausal women with the approved Kisqali combinations should also include an LHRH agonist in accordance with local clinical practice.

Management of severe or intolerable adverse reactions (ARs) may require temporary dose interruption, reduction or discontinuation of Kisqali. Please see section 4.2 of SmPC for recommended dose modification guidelines.

renal impairment. Caution should be used in patients with severe renal impairment with close monitoring for signs of toxicity. ♦Hepatic impairment: Mild: No dose adjustment is necessary. Moderate or severe: Dose adjustment is required, and the starting dose of 400 mg once daily is recommended. ♦Elderly (>65 years): No dose adjustment is required. ♦Pediatrics(<18 years): Safety and efficacy have not been established. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to peanut, soya or any of the excipients.

Warnings/Precautions: ♦Neutropenia was most frequently reported AR. A complete blood count (CBC) should be performed before initiating treatment. CBC should be monitored every 2 weeks for the first 2 cycles, at the beginning of each of the subsequent 4 cycles, then as clinically indicated. Febrile neutropenia was reported in 1.4% of patients exposed to Kisqali in the phase III clinical studies. Patients should be instructed to report any fever promptly.Based on the severity of the neutropenia, Kisqali may require dose interruption, reduction, or discontinuation.

♦Hepatobiliary toxicity - increases in

transaminases have been reported. Liver function tests (LFTs) should be performed before initiating treatment. LFTs should be monitored every 2 weeks for the first 2 cycles, at the beginning of each of the subsequent 4 cycles, then as clinically indicated. If grade ≥ 2 abnormalities are noted, more frequent monitoring is recommended. Recommendations for patients who have elevated AST/ALT grade ≥ 3 at baseline have not been established. Based on the severity of transaminase elevations, Kisqali may require dose interruption, reduction, or discontinuation. ♦QT interval prolongation has been reported with Kisqali. The use of Kisqali should be avoided in patients who have already or who are at significant risk of developing QTc prolongation. The ECG should be assessed prior to initiation of treatment. Treatment with Kisqali should be initiated only in patients with QTcF values <450 msec. The ECG should be repeated at approximately Day 14 of the first cycle and at the beginning of the second cycle, then as clinically indicated. In case of QTcF prolongation during treatment, more frequent ECG monitoring is recommended Appropriate monitoring of serum electrolytes (including potassium, calcium, phosphorous, and magnesium) should be performed prior to initiation of treatment, at the beginning of the first 6 cycles, and then as clinically indicated. Any abnormality should be corrected before the start of Kisqali treatment. Based on the observed QT prolongation during treatment, Kisqali may require dose interruption, reduction, or discontinuation. Based on the E2301 study QTcF interval data, Kisqali is not recommended for use in combination with tamoxifen. ♦Critical visceral disease. The efficacy and safety of ribociclib have not been studied in patients with critical visceral disease. ♦Severe cutaneous reactions Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) has been reported with Kisqali treatment. If signs and symptoms suggestive of severe cutaneous reactions (e.g. progressive widespread skin rash often with blisters or mucosal lesions) appear, Kisqali should be discontinued immediately. ♦Interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis ILD/pneumonitis has been reported with CDK4/6 inhibitors including Kisqali. Based on the severity of the ILD/pneumonitis, which may be fatal, Kisqali may require dose interruption, reduction or discontinuation as described in SmPC. Patients should be monitored for pulmonary symptoms indicative of ILD/pneumonitis which may include hypoxia, cough and dyspnoea and dose modifications should be managed in accordance with Table 5 (see section 4.2)

♦Blood creatinine increase ribociclib may cause blood creatinine increase – if this occurs it is recommended that further assessment of the renal function be performed to exclude renal impairment.

♦CYP3A4 substrates. ribociclib may interact with medicinal products which are metabolised via CYP3A4, which may lead to increased serum concentrations of CYP3A4 substrates (see section 4.5). Caution is recommended in case of concomitant use with sensitive CYP3A4 substrates with a narrow therapeutic index and the SmPC of the other product should be consulted for the recommendations regarding co administration with CYP3A4 inhibitors.

Pregnancy, Fertility and Lacation

♦Pregnancy: Pregnancy status should be verified prior to starting treatment as Kisqali can cause foetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman.

♦Women of childbearing potential who are receiving Kisqali should use effective contraception (e.g. double-barrier contraception) during therapy and for at least 21 days after stopping treatment with Kisqali. ♦Breast feeding: Patients receiving Kisqali should not breast feed for at least 21 days after the last dose. ♦Fertility: There are no clinical data available regarding effects of ribociclib on fertility. Based on animal studies, ribociclib may impair fertility in males of reproductive potential.

♦Effects on ability to drive and use machines Patients should be advised to be cautious when driving or using machines in case they experience fatigue, dizziness or vertigo during treatment with Kisqali.

Interactions: ♦Concomitant use of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors should be avoided, including, but not limited to, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, ketoconazole, lopinavir, ritonavir, nefazodone, nelfinavir, posaconazole, saquinavir, telaprevir, telithromycin, verapamil, and voriconazole. Alternative concomitant medicinal products with less potential to inhibit CYP3A4 should be considered. Patients should be monitored for ARs. If concomitant use of a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor cannot be avoided, the dose of Kisqali should be reduced (see section 4.2 of SmPC). ♦Grapefruit or grapefruit juice should be avoided. ♦Concomitant use of strong CYP3A4 inducers should be avoided, including, but not limited to, phenytoin, rifampicin, carbamazepine and St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum). An alternative medicinal product with no or minimal potential to induce CYP3A4 should be considered. ♦Caution is recommended when Kisqali is administered with sensitive CYP3A4 substrates with narrow therapeutic index (including, but not limited to, alfentanil, ciclosporin, everolimus, fentanyl, sirolimus, and tacrolimus), and their dose may need to be reduced. ♦Concomitant administration of Kisqali at the 600 mg dose with the following CYP3A4 substrates should be avoided: alfuzosin, amiodarone, cisapride, pimozide, quinidine, ergotamine, dihydroergotamine, quetiapine, lovastatin, simvastatin, sildenafil, midazolam, triazolam. ♦Caution and monitoring for toxicity are advised during concomitant treatment with sensitive substrates of drug transporters P-gp, BCRP, OATP1B1/1B3, OCT1, OCT2, MATE1 and BSEP which exhibit a narrow therapeutic index, including but not limited to digoxin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin and metformin. ♦Co-administration of Kisqali with medicinal products with known potential to prolong the QT interval should be avoided such as anti-arrhythmic medicinal products (including, but not limited to, amiodarone, disopyramide, procainamide, quinidine and sotalol) and other medicinal products known to prolong the QT interval including, but not limited to, chloroquine, halofantrine, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, azithromycin, haloperidol, methadone, moxifloxacin, bepridil, pimozide and intravenous ondansetron. Kisqali is not recommended for use in combination with tamoxifen.

Adverse reactions: ♦Very common: Infections, neutropenia, leukopenia, anaemia lymphopenia, decreased appetite, headache, dizziness, dyspnoea, cough, nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, constipation, stomatitis, abdominal pain, dyspepsia alopecia, rash, pruritus, back pain, fatigue, peripheral oedema, asthenia, pyrexia, abnormal liver function tests. ♦Common:, thrombocytopenia, febrile neutropenia, hypocalcaemia, hypokalaemia, hypophosphataemia, vertigo, lacrimation increased, dry eye, syncope, dysgeusia, , hepatotoxicity, erythema, dry skin, vitiligo, dry mouth, oropharyngeal pain, blood creatinine increased, electrocardiogram

FEATURE: Potential New Treatment for Asthma

Page 18

CPD: Post-Biologic Treatment for Psoriasis

Page 31

ONCOLOGY FOCUS: Radionuclide Therapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer

Page 36

ONCOLOGY FOCUS: Cancer Associated Venous Thromboembolism

Page 48

HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS

IRELAND

HPN February 2023 Issue 105 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE This Publication is for Healthcare Professionals Only

Special populations: ♦Renal impairment: Mild or moderate: No dose adjustment is necessary. Severe: A starting dose of 200 mg is recommended in patients with severe renal impairment. Kisqali has not been studied in breast cancer patients with severe

Kisqali can be taken with or without food (see section 4.5).The tablets should be swallowed whole and should not be chewed, crushed or split prior to swallowing.

for a

of adverse reactions. Legal Category: POM Pack sizes: Unit packs containing 21, 42 or 63 FCTs. Not all pack sizes may be marketed. Marketing Authorisation Holder: Novartis Europharm Limited Vista Building, Elm Park, Merrion Road, Dublin 4 Ireland Marketing Authorisation Numbers: EU/1/17/1221/003 & 005. Full prescribing information is available on request from Novartis Ireland Ltd, Vista Building, Elm Park Business Park, Dublin 4. Tel: 01 2601255 or at www.medicines.ie Prescribing information last revised: April 2022 November 2022 | IE253121 © 2022 Novartis Novartis Ireland Ltd, Vista Building, Elm Park Business Park, Merrion Road, Dublin 4, D04 A9N6 REFERENCES: 1. Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Overall survival results from the phase III MONALEESA-2 trial of postmenopausal patients with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer treated with endocrine therapy ± ribociclib. Presented at: European Society of Medical Oncology; September 16-21, 2021. 2. Im S-A, Lu Y-S, Bardia A, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):307-316. 3. Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J

QT prolonged. ♦Please refer to SmPC

full list

KISQALI is not indicated for concomitant use with tamoxifen4 1L, first line; 2L, second line; ET, endocrine therapy; LHRH, luteinizing hormonereleasing hormone, aBC, advanced breast cancer. ESMO - European society of medical oncology SABC - San Antonio Breast Cancer Conference ASCO - American Society of Clinical Oncology Reporting suspected adverse reactions of the medicinal product is important to Novartis and the HPRA. It allows continued monitoring of the benefit/risk profile of the medicinal product. All suspected adverse reactions should be reported via HPRA Pharmacovigilance, website www.hpra.ie. Adverse events could also be reported to Novartis preferably via www.report.novartis.com or by email: drugsafety.dublin@novartis.com or by calling 01 2080 612. National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) now recognizes ribociclib (KISQALI®) + ET, a Category 1 preferred treatment option, for showing an OS BENEFIT IN 1L PATIENTS with HR+/HER2- mBC4 NCCN RECOMMENDED KISQALI—the only CDK4/6 inhibitor with statistically significant overall survival across all 3 phase III trials1–3

TO LIVE WELL WITH HIV

DEVELOPED WITH THE HIV COMMUNITY, FOR THE HIV COMMUNITY

For information and resources to support those living with HIV to live well visit www.hivfindyourfour.ie

Find Your Four is a campaign developed and funded by Gilead Sciences, in collaboration with the HIV community.

UK-UNB-3430 | January 2023

Government must answer ‘999’ call P4

Capacity in Irish Hospitals reaches breaking point P5

Hospital Pharmacists finally receive commitment to pay revision P6

Medicines Shortage Index provides worrying insights P9

New Platform launched to tackle Obesity P12

Robotic First at Galway University Hospital P17

REGULARS

Feature: Precision Medicine for COPD P26

CPD: Psoriasis P31

Oncology Focus: Triple Negative Breast Cancer P40

Oncology Focus: Lung Cancer P52

Feature: Ulcerative Colitis P77

P80

Hospital Professional News is a publication for Hospital Professionals and Professional educational bodies only. All rights reserved by Hospital Professional News. All material published in Hospital Professional News is copyright and no part of this magazine may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form without written permission. IPN Communications Ltd have taken every care in compiling the magazine to ensure that it is correct at the time of going to press, however the publishers assume no responsibility for any effects from omissions or errors.

PUBLISHER

IPN Communications Ireland Ltd Clifton House, Lower Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2 (01) 669 0562

GROUP DIRECTOR

Natalie Maginnis n-maginnis@btconnect.com

EDITOR

Kelly Jo Eastwood

DIGITAL MARKETING & EDITORIAL EXECUTIVE

Emilia Bayliss

emilia@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

EDITORIAL editorial@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

ACCOUNTS

Rachel Wilson cs.ipn@btconnect.com

SALES EXECUTIVE

Aoife Tremere aoife.t@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

CONTRIBUTORS

N Tangney | DM Murphy

Tomás P. Carroll | Ronan C. Heeney

Geraldine Kelly | Gerry McElvaney

Dr Jonathan Briody | Mr Richard Walsh

Professor Kilian Walsh | Amina Babar

Mary N. O’Reilly | Michaela J. Higgins

Lucy Norris | Theresa Lowry Lehnen

Síle Griffin | Fiona Griffin

Tatiana Larmak | Naoise Irwin

Professor Joe M. O’Sullivan

Yasmina E. Hernandez Santana

Patrick T. Walsh

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Ian Stoddart Design

Editor

As 2023 and a New Year gets underway, unfortunately some lingering issues from the past remain. Notably medicine shortages and the pressures being faced by Ireland’s hospitals.

On page 4, we detail how the Irish Hospital Consultants Association (IHCA) has urged the Government to treat the growing crisis in the health service as an ‘emergency 999 call’, given that almost 900,000 people are on some form of NTPF waiting list, a record 931 admitted patients were treated on trolleys last week, and 918 permanent Consultant posts nationally are either vacant or filled on a temporary or agency basis.

IHCA President Professor Robert Landers said: “This is a lifethreatening situation for patients seeking care in our hospitals and requires a ‘999- like’ emergency response from Government.”

The Medicines Shortage Index, prepared by Azure Pharmaceuticals, has found that there are 224 medicines currently unavailable, an increase of 12 medicines in seven days (at 11 January). Among the additional medicines to go out-of-stock in the past weeks are Phenytoin which is used to treat epilepsy.

Analysis by the group found that 40% of the medicines currently out of stock are provided to the Irish market by a single supply. Furthermore, the survey has shown that medicine manufacturers, including companies producing medicines domestically, are getting paid up to four times as much for their products abroad than in Ireland.

The EU is preparing to stockpile drugs and oblige manufacturers to guarantee supplies in efforts to tackle the on-going medicines shortages.

The European Commission will also try to reduce reliance on China and increase domestic production capacity, the commission told the Financial Times — which reported the news. In a written response to the Greek government, EU health commissioner Stella Kyriakides outlined the plan. The commission will intervene to ensure “strategic autonomy” in basic medicines through a “systemic industrial policy”.

You can read more about this in our Report starting on page 9 of this issue.

Our Special Focus this month is on Oncology, tying in with World Cancer Day on Saturday, 4th February. We have some excellent clinically contributed content, including Triple Negative Breast Cancer: A Background and Cost in Ireland; Common Urological Side effects of Radiotherapy, and Biomarkers for Cancer

Associated Venous Thromboembolism.

I hope you enjoy the issue.

3 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • FEBRUARY 2023 February Issue Issue 105 4

Contents Foreword

Clinical R&D:

12 6 17 HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE @HospitalProNews HospitalProfessionalNews

Government must answer ‘999’ Call

The Irish Hospital Consultants Association (IHCA) has urged the Government to treat the growing crisis in the health service as an ‘emergency 999 call’, given that almost 900,000 people are on some form of NTPF waiting list, a record 931 admitted patients were treated on trolleys last week, and 918 permanent Consultant posts nationally are either vacant or filled on a temporary or agency basis.

The appeal from Consultants for an emergency response from Government comes as the latest figures from the National Treatment Purchase Fund (NTPF) released today reveal that 870,000 people were on some form of NTFP waiting list at the end of December – a reduction of just 9,000 compared with the start of 2022.

Minister for Health Stephen Donnelly launched the Government’s ¤350 million Waiting List Action Plan for 2022 last February2 which committed to reducing active waiting lists for acute scheduled care by 18% (more than 132,00) by the end of 2022.

Before leaving office, former HSE CEO Paul Reid said that the HSE could not forecast whether a reduction in the waiting lists of 18%, 15% or even 10% could be achieved by the end of 2022.3 In fact, today’s NTPF figures confirm the three main waiting lists

covered by the plan decreased by just 29,800 or 4%. This decrease takes account of 71,000 people who were removed from the waiting lists without any treatment in the first nine months of 2022 through an NTPF ‘validation programme’.

Growth in a number of pre-admit, planned and suspension lists not widely publicised means that overall NTPF waiting lists reduced by just 9,180 in 2022, and have risen by a staggering 286,500 (49%) since the publication of Sláintecare in 2017. Including the additional 243,000 people on waiting lists for CTs, MRIs or ultrasounds nationally5 sees the total number of people awaiting hospital care now amount to over 1.1 million.

New analysis from the IHCA shows that the HSE is 102,500 outpatient appointments and procedures away from meeting the 18% reduction target for the end of 2022, including almost 97,000 outpatient appointments and around 5,500 inpatient/day case procedures and GI scopes.

Last month, the number of patients awaiting inpatient/day case treatment increased for the fourth month in a row, and at 81,568 are at the highest level since the peak of the pandemic in April 2020. Consultants have raised their concerns that the combination

of the unprecedented spike in hospital overcrowding, the longstanding deficits in hospital capacity and the record vacant Consultant posts could see the number of people on hospital waiting lists reach new record highs in the months ahead, due to the continued cancellation of essential scheduled care across the country.

Commenting on today’s waiting lists, IHCA President Professor Robert Landers said:

“This is a life-threatening situation for patients seeking care in our hospitals and requires a ‘999like’ emergency response from Government. With almost 900,000 people on waiting lists, over 900 vacant Consultant posts and 900 admitted patients treated on a chair or trolley on a single day last week, the numbers paint a stark picture of the crisis facing the health service.

“But we cannot forget that the vast waiting lists represent individual adults or children who could be experiencing pain, suffering or the psychological distress at not knowing when they will be able to receive the hospital treatment they need. This is a wholly unacceptable situation.

“Regrettably, in the short-term, waiting lists are likely to deteriorate further due to the cancellation of many outpatient appointments,

inpatient admissions, and day case procedures, including chemotherapy and dialysis.

“The Government needs to urgently put in place a credible plan to provide care to the 1.1 million people awaiting essential hospital assessment and treatment. This can only be achieved by addressing the twin deficits of a shortage of Consultants and a lack of sufficient public hospital capacity.

“The fact that 918 permanent Consultant posts, 23% of the total number approved, cannot be filled as needed is a shocking signal to Government and health service management that the current conditions in our public hospitals are not up to the standard required by skilled medical and surgical specialists to practise effectively. This in turn is driving our highly trained specialists abroad to pursue their careers in countries where they work in collaborative and supportive health services.”

4 FEBRUARY 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Professor Robert Landers, President, IHCA

“The Government needs to urgently put in place a credible plan to provide care to the 1.1 million people awaiting essential hospital assessment and treatment”

Hospital Capacity hits new Heights

The Irish Hospital Consultants Association (IHCA) has expressed its concern over the continued pressures being faced by Ireland’s acute hospital services as extreme levels of overcrowding in our emergency departments and un-safe capacity limits hit record new highs.

Commenting, a spokesperson for the IHCA said, “The Irish health service is once again the focus of public, political and media attention. The level of coverage of individual and collective experiences from within our hospitals over the past number of weeks is only comparable to that of the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. It is not inconceivable that we could see 1,000 admitted patients being

treated on trolleys on a single day in the weeks ahead.

“Public hospital staff are working tirelessly attempting to provide appropriate levels of care to patients. Consultants are on call 24/7, often practising over and above recommended levels, but the reality is there simply aren’t enough of us to meet increased demand. We are still working with 40% less Consultant staffing in Ireland, compared to the EU average.

“What compounds this further is the failure of Government to put in place bed and staffing commitments dating back years. When Consultants do eventually get to see patients, we face restricted care flows

due to inadequate bed and theatre capacity, and required staffing levels.

“The Winter Plan 2022/23 committed to appointing 51 additional Emergency Medicine Consultants, yet as we hit the peak of winter illness, none of these have been appointed as yet on a permanent basis, with just approximately 20 locum Consultants in place. This is not surprising given that it took on average 9 months to fill a vacant Consultant post in 2022.

“In addition, the Department of Health has no credible plan to urgently put in place the 1,400 additional public hospital beds that need to be opened more speedily

than anticipated in what is an outof-date 2018 Capacity Review.

“As a result, those of us on the ground in hospitals and delivering care in the community are consistently left to firefight for ourselves with the limited and overstretched resources we have.

“The HSE’s National Service Plan 2023 is now due and must be published as soon as possible, taking all this into consideration. To move away from this constant wheel of crises, the Government must put in place the capacity expansion that is needed and the HSE must empower hospitals and community services to make decisions and take the actions needed to provide timely and safe care to their patients.”

Nominations open for Medical Council Election

The Medical Council has announced the procedures for the election of the six directly elected members of the Medical Council.

The Medical Council, which is the regulatory body for doctors, has a statutory role in protecting the public by promoting the highest professional standards amongst doctors practising in Ireland, and is made up of 25 members, with a majority of 13 non-medical members and 12 medical members. Members are appointed through a mixture of elections, nominations by a

number of bodies and through the public appointments system.

In order to be eligible for nomination for election to the Medical Council, a medical professional must be on the register of medical practitioners, and must be practising medicine in the State (but excluding any visiting EEA practitioner) on 15th February 2023, the day before nominations close. They must be nominated for election by 10 registered medical practitioners practising medicine in the State.

An independent Returning Officer has been appointed and, in accordance with the provisions of section 17(1) and (8) of the Medical Practitioners Act 2007, will conduct the election process. The Medical Council is encouraging all interested and eligible doctors to consider running for election.

The closing date for receipt of nomination papers is Thursday, 16th February 2023 at 1pm. The independent Returning Officer will attend at the offices of the

Medical Council to receive nomination papers, which can be submitted via post or in person on 16th February, 2023 between the hours of 10am – 1pm.

Nomination papers and other information, including information on the roles and responsibilities of Council members, which is included in the Medical Council’s Corporate Governance Framework regarding the election, are available on the Medical Council website www.medicalcouncil.ie/elections

5 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • FEBRUARY 2023

News

Revised Pay and New Posts for Hospital Pharmacists

Forsa National Secretary Linda Kelly

The circular activates the recommendations contained in the 2017 McLoughlin Report and subsequent negotiations. It confirms improvements to the basic grade pharmacist salary scale, while increment dates remain unchanged.

The Department of Health and HSE have issued circulars confirming the implementation of a revised pay scale and revised management posts for hospital pharmacists, agreed with Fórsa and the HPAI following the Building Momentum review last year.

The new pay scale sees the removal of the first three points of the existing scale and will result in an adjustment to salary for most, while the old salary scale will be maintained in the Department of Health consolidated salary scales for pension purposes.

The introduction of the new pharmacy executive services manager post is also confirmed by the circular and takes effect from the same date. Details of how existing postholders will be designated to those posts are also outlined in the circular.

National secretary Linda Kelly said the circular’s confirmation of new scales and agreed management posts marked the conclusion of a lengthy union campaign to ensure the recommendations of the McLoughlin report were activated: “Despite a long drawn-out negotiation, our hospital pharmacist members were determined to achieve what has now been confirmed in this circular.

“A clause in the review of Building Momentum last year provided the

New Study on Parkinson’s Disease

The activity of multiple genes in the brain varies according to sex among people with Parkinson’s disease, a new study reports.

These differences may contribute to discrepancies in how Parkinson’s tends to affect men and women. “While males have a higher age-adjusted disease incidence and are more frequently affected by muscle rigidity, females present more often with disabling tremors,” its researchers noted.

The reasons for these sex-based differences are poorly understood. To learn more, a trio of researchers in Luxembourg conducted a metaanalysis, a type of study where scientists pool and collectively analyze data from multiple studies. Specifically, this work focused on datasets of gene expression in samples of brain tissue collected after death from people with Parkinson’s and matched adults without the disease as controls.

Gene expression refers to how much individual genes are “turned on or off” in terms of their activity. They assessed nearly 12,000 genes, looking for those whose activity levels were significantly altered in patients versus controls according to sex. They identified 1,146 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in men with Parkinson’s and 118 DEGs in female patients.

Partly, the higher number of DEGs in men could be due to the larger number of male samples included in the analysis, allowing greater statistical power to identify significantly altered gene activity, the researchers noted.

However, analyses involving a subset of the men also generally yielded higher numbers of genes with altered activity. As such, “the lower number of significant DEGs in females may at least partly reflect a different disease manifestation and progression,” the team wrote.

The scientists divided the DEGs into three categories: 36 were female specific, meaning

significant activity changes were detected in women only, while 539 were male specific. Another 37 DEGs were sex dimorphic, meaning they showed opposite trends between sexes (higher levels in women but lower levels in men, or vice versa).Many of the genes identified in these analyses “are involved in cellular processes and organelles previously described to display pathological [disease-driving] alterations in PD [Parkinson’s disease],” the researchers wrote.

For example, several of these genes are involved in the production of dopamine or the function of mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses, and lysosomes, the cell’s recycling centers. Dopamine is the major brain chemical messenger that’s progressively lost in Parkinson’s, while mitochondrial damage and lysosomal impairment have been implicated in the disease.

Further analyses were conducted to assess the biochemical pathways most affected by these gene activity changes. Results indicated that malespecific and sex-dimorphic DEGs were commonly involved in mitochondrial function and cellular energy metabolism, while femalespecific DEGs more commonly associated with inflammation.

necessary negotiating opportunity to ensure these measures were introduced, and we were able to confirm the outcome to pharmacist members last November.

“The new HSE circular confirms that all the necessary arrangements are now in place, and I want to acknowledge the great work of our hospital pharmacist representatives throughout this process. It demonstrates, yet again, the real power of trade union membership and collective bargaining.

“Implementation discussions on the remaining recommendations related to the deputy pharmacy executive services manager posts and the creation of advanced specialists posts will now commence,” she said.

“No significant overlap was observed between the pathways with female DEGs and male DEGs, suggesting that instead of affecting different genes in the same pathways, sex-specific changes tend to affect diverse pathways,” the team wrote.

While many of the DEGs have known functions in Parkinson’srelated pathways, most have not been specifically linked to Parkinson’s before.

Notably, one exception was the NR4A2 gene, whose activity was generally lower in Parkinson’s patients relative to controls, but the effect was much more pronounced in men.

This gene has a “key regulatory role in the maintenance of dopamine metabolism and inflammatory gene expression,” the researchers wrote, and its reduced activity has been linked to brain aging and increased production of the alpha-synuclein protein, a hallmark of Parkinson’s.

Preclinical work has implicated NR4A2 activity changes in Parkinson’s and suggested that the protein it encodes may be a useful treatment target.

Two other sex-dependent DEGs of interest with Parkinson’sassociated regulatory functions were CA2 and EFNA1

6 FEBRUARY 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

“No significant overlap was observed between the pathways with female DEGs and male DEGs, suggesting that instead of affecting different genes in the same pathways, sex-specific changes tend to affect diverse pathways”

Standard LCIG*

... a reduced levodopa dose can be given

*Levodopa-Carbidopa Intestinal Gel 1. Lecigon Summary of Product Characteristics, 2021.

The same effective and stable plasma levodopa levels are achieved

ABBREVIATED PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. Lecigon 20 mg/ml + 5 mg/ml + 20 mg/ml intestinal gel. 1 ml contains 20 mg levodopa, 5 mg carbidopa monohydrate and 20 mg entacapone. Presentation: Yellow or yellowish-red opaque viscous gel. Indications: Treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease with severe motor fluctuations and hyperkinesia or dyskinesia when available oral combinations of Parkinson medicinal products have not given satisfactory results. Dosage and administration: Adults/Elderly: Administration by a portable infusion pump directly into the duodenum or upper jejunum via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy(PEG) tube or radiological gastrojejunostony tube. Please consult Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for further information. Only pump Crono LECIG (CE 0476) may be used for the administration of Lecigon. The dose should be titrated to achieve the optimal clinical response in the individual patient, which involves maximising the functional ON-time during the day by minimising the number and duration of OFF episodes (bradykinesia) and minimising ON-time with disabling dyskinesia. Total dose/day of Lecigon is composed of three individually adjusted doses: the morning bolus dose, the continuous maintenance dose, and extra bolus doses. Treatment is usually limited to the patient’s awake period. If medically justified, Lecigon can be administered up to 24 hours/day. The maximum recommended daily dose is 100 ml (2000 mg levodopa, 500 mg carbidopa monohydrate and 2000 mg entacapone. Please consult SmPC for further information. Total morning dose is usually 5–10 ml (100–200 mg levodopa) but not exceeding 15 ml (300 mg levodopa). Continuous maintenance dose is usually 0.7–5.0 ml/hour (15–100 mg levodopa/hour). Extra bolus doses are given if the patient becomes hypokinetic and are normally less than 3ml. An increase in the continuous maintenance dose should be considered if the need for extra doses exceeds 5 doses per day. Please consult SmPC for further information. After initial titration, the morning dose and maintenance dose are fine-tuned over the course of a few weeks. Lecigon is initially given as monotherapy. If needed, other anti-Parkinsonian medicinal products can be taken concurrently. If treatment with other anti-Parkinsonian medicinal products is discontinued or changed, it may be necessary to adjust the doses of Lecigon. Sudden deterioration in response with recurring motor fluctuations may indicate that the tube has dislocated to the stomach. This needs confirmation by X-ray and may require repositioning. Please consult SmPC for further information. The cartridge is for single use only and should not be used for more than 24 hours. Children: There is no relevant indication for use in children and adolescents. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substances or any of the excipients, narrow-angle glaucoma, severe heart failure, severe cardiac arrhythmia, acute stroke, severe hepatic impairment. Non-selective MAO-inhibitors and selective MAO type A inhibitors are contraindicated and should be discontinued at least two weeks prior to initiating therapy with Lecigon. Conditions in which adrenergics are contraindicated. Previous neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and/or non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Suspected undiagnosed skin lesions or a history of melanoma. Please consult SmPC for further information. Warnings and precautions: Not recommended for the treatment of drug-induced extrapyramidal reactions. Caution in ischaemic heart disease, severe cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, renal, hepatic or endocrine disease, or history of peptic ulcer disease or of convulsions, past or current psychosis, chronic wide-angle glaucoma, concomitant administration of antipsychotics with dopamine receptor blocking properties or with medicines which may cause orthostatic hypotension. In patients with a history of myocardial infarction who have residual atrial nodal or ventricular arrhythmias, cardiac function should be monitored with particular care during the period of initial dosage adjustments. Monitor all patients for mental changes, depression with suicidal tendencies, and other serious mental changes. Neuroleptic malignant like syndrome with secondary rhabdomyolysis may occur on abrupt dose reduction/discontinuation of Lecigon. Patients should be monitored for the development of impulse control disorders and review of treatment is recommended if such symptoms develop. Patients and caregivers are advised to monitor for melanomas on a regular basis when using Lecigon. Dose may need to be adjusted downwards to avoid levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Periodically evaluate hepatic, haematopoietic, cardiovascular and renal function during extended therapy. Lecigon contains hydrazine, a degradation product of carbidopa that can be genotoxic and possibly carcinogenic. Reported complications for levodopa/carbidopa in clinical studies include bezoar, ileus, implant site erosion/ulcer, intestinal haemorrhage, intestinal ischaemia, intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, intussusception, pancreatitis, peritonitis, pneumoperitoneum and post-operative wound infection. Sudden or gradual worsening of bradykinesia may indicate an obstruction in the tubing system and should be investigated. Weight loss has been associated with the active substances contained in Lecigon, and caregivers should therefore be aware of weight loss. Monitoring of weight is recommended to avoid severe weight loss. Prolonged or persistent diarrhoea that appears during use of entacapone could be a sign of colitis. In case of prolonged or persistent diarrhoea, treatment with the medicinal product should be discontinued and other appropriate medical treatment and investigation considered. Replacement of Lecigon with either levodopa and a DDC inhibitor without entacapone or other dopaminergic therapy may be necessary and should be done slowly. For patients who experience progressive anorexia, asthenia and weight loss within a relatively short period of time, a general medical evaluation including liver function assessment should be considered. Please consult SmPC for further information. Interactions: Antihypertensives, antidepressants, anticholinergics, dopamine receptor antagonists, benzodiazepines, isoniazide, phenytoin, papaverine, sympathicomimetrics , iron, protein-rich diet, amantadine and dopamine agonists (e.g. piribedil) may increase levodopa-related adverse events. Lecigon dose adjustment may be needed when used with these medicines. Lecigon can be taken with MAO type B inhibitors (e.g. selegiline) although serious orthostatic hypotension may occur and the dose of levodopa may need to be reduced. Lecigon may affect metabolism of medicinal products such as S-warfarin and patients should be monitored during initiation with Lecigon therapy when used with this medicine. Please consult SmPC for further information. Pregnancy and lactation: Lecigon is not recommended during pregnancy or in women of childbearing potential not using contraception unless the benefits for the mother outweigh the possible risks to the foetus. It is unknown whether carbidopa and entacapone or their metabolites are excreted in human milk. Breastfeeding should be avoided during treatment with Lecigon. Driving and operation of machinery: Caution; Lecigon can have a major influence on the ability to drive and use machines. Refrain if somnolence and/or sudden sleep episodes occur. Undesirable effects: Weight loss, anxiety, depression, insomnia, dyskinesia, Parkinson’s disease /exacerbation of parkinsonism (e.g. bradykinesia), orthostatic hypotension, nausea, constipation, diarrhoea, pain in muscles and tissues, musculoskeletal pain, chromaturia, fall. Complications of the device and surgery: Postoperative wound infection, abdominal pain, excessive granulation tissue, complication of device insertion, incision site erythema, post-procedural discharge, procedural pain, procedural site reaction. Refer to SmPC for other undesirable effects. Adverse events should be reported via HPRA Pharmacovigilance, website: www.hpra.ie. Special precautions for storage: Store in a refrigerator 2°C - 8°C. Do not freeze. Store in the original package in order to protect from light. For storage instructions after first opening of the medicinal product, refer to the summary of product characteristics. Pack size: 7 x 47 ml cartridges. Marketing authorisation holder: LobSor Pharmaceuticals AB, Kålsängsgränd 10 D, SE-753 19 Uppsala, Sweden. Distributed by Clonmel Healthcare Ltd, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. Marketing authorisation number: PA23144/001/001. Medicinal product subject to medical prescription. A copy of the summary of product characteristics is available upon request or alternatively please go to: www.clonmelhealthcare.ie Last revision date: March 2022. Date of Preparation: October 2022. 2022/ADV/LEC/268H

A combination of three effective Parkinson’s therapies in one convenient gel formulation for intestinal infusion1

Levodopa (20 mg/ml) Carbidopa monohydrate (5 mg/ml) Entacapone (20 mg/ml) Increased levodopa bioavailability with LECIGON®

Highest Recorded Figure of Newly Notified Cases of HIV

HIV Ireland has called for increased investment in nationwide sexual health services, including personnel and resources, to ensure Ireland can meet its global commitment to end new HIV transmissions. Statistics published weekly by the Health Protection Surveillance Centre indicate that more 750 cases of HIV have been notified in 2022, more than double the number for the same period in 2021. However, despite the increase in notifications, falling rates of new transmissions occurring within Ireland give cause for optimism.

The HPSC records newly notified case as those who have recently acquired the virus together with people already living with the virus and transferring their care to Ireland.

“Under diagnosis of HIV remains a concern. The European Centre

for Disease Prevention and Control has said that an estimated 1 in 8 people living with HIV in the EU/ EEA area remain undiagnosed,” said Stephen O’Hare Executive, Director of HIV Ireland.

“In order to decrease the number of undiagnosed cases,” continued Mr O’Hare, “timely access to early testing and subsequent linkage to care is vital.”

“While treatment for HIV is available free at the point of use in the public health system in Ireland, barriers to accessing testing persists,” he added.

This year, UNAIDS has called on the world to unite to end the inequalities that underpin and perpetuate HIV transmission, including increasing investment in new strategies and user-friendly approaches to more widely available HIV testing, treatment

and prevention to improve early diagnosis, end new HIV transmissions, and end AIDSrelated deaths.

The stigma and exclusion faced by people living with HIV and marginalised populations remains a significant barrier to accessing testing, treatment uptake, adherence to medication and seeking support.

HIV-related stigma still persists including among health care professionals. Research conducted this year by Dr Elena Vaughan of NUI Galway and supported by HIV Ireland found that among healthcare workers who were not HIV specialists, 83% claimed knowledge of ‘Undetectable = Untransmittable’ (U=U) and treatment as prevention. However, 40% said they would still be nervous about drawing blood from

Body Clock effect on Respiratory Conditions

a person living with HIV leading to unnecessary ‘extra’ precautions, e.g., excessive use of PPE.

This year, HIV Ireland is once again promoting its Glow Red for World AIDS Day campaign to shine a light on the impact of HIV-related stigma. Over 40 buildings and landmarks around Ireland will light up in red to show their support and to mark 40 years since the first reports of HIV and AIDS on our shores.

HIV stigma is real and ending HIV stigma is a real possibility. As internationally renowned Irish HIV activist and ambassador of this year’s Glow Red campaign, Rebecca Tallon de Havilland, has said, “We can end stigma by strengthening the voices of people living with HIV. Using my voice has empowered me to overcome selfstigma and live my best life.”

usual function to recruit other immune cells to the lungs. More cells than are needed are brought to the lungs, resulting in damaging inflammation.

This could have implications for individuals such as shift workers or people with erratic sleeping/eating patterns in that they are more likely to experience more severe respiratory infections.

This study pinpoints lung fibroblasts as a potential target in the treatment of lung diseases that display this kind of inflammation, a change in approach from most current therapeutic options which focus on easing symptoms rather than treating the cause.

Researchers at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences have discovered how disruption of the circadian clock can lead to increased inflammation in the lungs, which may have negative effects on chronic lung diseases and respiratory infections.

The paper, published in The FASEB Journal, looked at the molecular clock in fibroblasts, a cell type which is abundant in the lung. When the regular rhythm of the fibroblast clock was lost, it resulted in an increased inflammatory response and therefore, worse symptoms.

Lead author Shannon Cox, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences at RCSI, said, “This study links together previous knowledge to confirm the importance of lung fibroblasts in inflammation and highlights the negative consequences of disruption to our circadian clock, such as poor night-time sleep, in lung disease. We can apply this understanding when developing therapies and interventions for patients.”

Disturbing the circadian clock in lung fibroblasts impacts their

The majority of this study was supported through funding provided to Professor Annie Curtis by the Science Foundation Ireland Career Development Award (CDA) programme and by the Irish Research Council through a Laureate Award.

Further support was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant, a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds travel grant and an RCSI School of Postgraduate Studies International Secondment Award.

The PMI’s Annual Pharma Summit will be held on March 30th, 2023 at Croke Park

Our theme for the day is “Partnering to Improve Human Health” and we will be exploring this theme throughout the day from four vantage points: Technology, Government, Cross Company and Intra Company.

The day will be highly interactive with a mix of keynote speakers and panel discussions with plenty of opportunities to catch up with industry colleagues and make new connections.

Further details regarding speakers will be revealed over the coming weeks.

8 FEBRUARY 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Professor Annie Curtis

Medicine Shortages Reaching EU Level and ‘Critical’ Point

Medicines shortages are not a new phenomenon. Certainly since the advent of Covid-19, Brexit and the Northern Ireland protocol, the issue is becoming more critical.

The mainstream media has been increasingly reporting on the situation during the start of this new year, as a severe shortage of OTC cough syrups for adults and children has alarmed parents and caregivers. Sprays for sore throats, dissolvable paracetamol powder and soluble aspirin are also widely unavailable.

The Medicines Shortage Index, prepared by Azure Pharmaceuticals, has found that there are 224 medicines currently unavailable, an increase of 12 medicines in seven days (at 11 January). Among the additional medicines to go out-of-stock in the past week are Phenytoin which is used to treat epilepsy.

There is a major shortage of over-the-counter cough syrups for adults and children. Sprays for sore throats, dissolvable paracetamol powder and soluble aspirin are also widely unavailable.

Antibiotics used to treat bacterial and respiratory infections, including Amoxicillin, Penicillin and Cefalexin, are also in scarce supply.

Analysis by the group found that 40% of the medicines currently out of stock are provided to the Irish market by a single supply.

Furthermore, the survey has shown that medicine manufacturers, including companies producing medicines domestically, are getting paid up to four times as much for their products abroad than in Ireland.

The authors of the Medicine Shortages Index, also identified that medicine shortages have further worsened.

Azure has analysed the average prices paid for 10 essential mainstream medicines by Irish, UK and European governments.

Its analysis shows that, on average, the UK and EU member governments are paying twice as much to manufacturers than the comparative prices that the Irish government/industry agreement allows. Some countries are paying up to four times more than Ireland, giving rise to serious shortages for patients

here as manufacturers choose to maximise returns through supplying higher price markets.

Azure is currently not supplying any of the above medicines to the Irish market.

The UK government and the majority of the 27 EU member state governments have taken specific measures in response to the escalating medicine shortage issue. This includes, changes to medicine pricing rules, stockpiling of key products, the introduction of an export ban of key drugs, and provision of additional powers to pharmacists. To date, the Department of Health is yet to meaningfully respond to this deepening challenge.

Commenting, Sandra Gannon, General Manager, Azure Pharmaceuticals said:

“In less than a decade, we have gone full circle on what we pay for mainstream medicines with Ireland now paying substantially less than neighbouring countries for a range of medicines. As a result, manufacturers are choosing

to supply their medicines to those countries who will pay better prices. This in turn gives rise to growing medicines shortages and discontinuations here with patients unable to source the medicines they need. We are paying the price for not paying the price.

“The government appears to be at best misinformed and at worst, in denial about the root cause of this worsening problem. Changing legislation to give extra powers to pharmacists should form a key part of a package of solutions, but that alone will not resolve matters. The price we pay, and a medicines pricing agreement that is no longer fit-for-purpose, is at the heart of this issue.

“The HPRA has a co-ordinating role to manage shortages but is can only respond with regulatory measures, as it acknowledged itself in a statement this week. This issue requires a mix of actions by the Department of Health. To date, that has been lacking.”

40% of the medicines out of stock this month in Ireland have

just a single supplier, leaving pharmacists without licensed alternatives for patients. It also leaves Ireland out of sync with the rest of Europe, with a recently published European Commission report showing the EU wide singled-sourced average standing at 25%.

Heed Warnings

Medicines for Ireland (MFI) are also urging Government to heed recent warnings from GPs and pharmacists nationwide on the growing risk of medicines shortages as inflation, energy and transport costs continue to rise, and global supply chain disruptions persist.

Medicines for Ireland members are the suppliers of the majority of medicine in Ireland to the HSE and patients directly and played a pivotal role in a new Framework Agreement on the supply and pricing of non-originator, generic, biosimilar, and hybrid medicines, announced by Government last year.

9 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • FEBRUARY 2023

Report

Medicine Strength Pack Size IE € UK € EU Average € Treatment For Paracetamol 500 mg tablet 100 pack 1.73 3.05 7.35 Pain Amoxicillin 500mg capsule 100 pack 16.15 31.75 24.46 Infection Lorazepam 1g tablet 100 pack 3.77 7.63 11.43 Anixety Prednisolone 5mg tablet 98 pack 3.06 4.2 7.49 Inflammation/Asthma Nitrofurantoin 100mg Caps 30 pack 6.73 13.03 11.91 Urinary tract infection Amisulpride 200mg 60 pack 31.68 39.08 60.99 Schizophrenia Clonazepam 0.5mg 100 pack 4.33 35.46 13.59 Epilepsy Co-Amoxiclav 125/31mg/5ml 100 pack 1.38 6.25 4.12 Infection Tamoxifen 20mg tabs 30 pack 4.58 3.16 9.11 Breast Cancer Ipratropium Nebules 250mg/ml x 2ml 20 pack 4.5 7.46 7.95 COPD

Sandra Gannon, General Manager, Azure Pharmaceuticals

Commenting on increasing medicine shortages, Medicines for Ireland Chairperson, Padraic O’Brien has said “In Ireland and throughout Europe, soaring energy costs, inflation and supply chain disturbances have contributed to thousands of generic medicines disappearing from the European and Irish market.”

“MFI members are willing to work directly with Government to help tackle this serious issue and prevent potential medicines shortages. Our aim is to deliver industry insights and extend our expertise to help improve the development of medicinal pricing

and procurement policies in Ireland and safeguard the supply of medicines to Ireland.”

According to the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) website there are currently 187 medicines in short supply in Ireland. Without intervention this situation has the potential to significantly worsen.

Mr O’Brien added, “As a small market Ireland is more likely to be badly impacted by inflationary pressure and as costs continue to rise, market conditions will become increasingly unviable for companies supplying generic medicines to Irish hospitals and

pharmacies. Additionally, in some cases, our reimbursement prices for certain medicines are too low compared to other EU countries”.

“Price adjustments in Ireland are historically downward only, where other European countries employ flexible pricing mechanisms that allows reimbursement prices to rise for medicines that are in short supply. Ireland does not have such a mechanism and is therefore further disadvantaged.”

A recent MFI members survey found that 91% of MFI members experienced increased costs associated with import and/or manufacturing of pharmaceutical

and medical products for the Irish market in 2022. While all MFI member companies envisage increases in transportation costs over the next 12 to 24 months.

“Our main focus is to help Government ensure market conditions in Ireland remain sustainable in order to retain and secure access to reliable and affordable treatment for Irish patients. We believe it is time for us to revisit our work with Government and the HSE on the Framework Agreement on Supply and Pricing and develop improvements to mitigate against supply risks.” concluded Mr O’Brien.

10 FEBRUARY 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE Report

HPRA Statement

The Healthcare Products Regulatory Authority said in a statement, “Due to a combination of factors, including the level of respiratory illnesses in the community, a significant increase in demand for medicines used to treat seasonal conditions such as colds and flus has been observed over recent weeks. In some cases, this demand has been 2-3 times the normal level seen during the same period in previous years. From discussions with suppliers and regulators in other countries, the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) understands that similar trends have been observed

in other European countries who have experienced significant increases in demand.

“The HPRA has been engaging with all stakeholders, including suppliers, with a view to ensuring a coordinated response to this increased demand. The key focus at all times has been to ensure that suitable medicines remain available to treat all patients.

“In the case of medicines used most often in Ireland, there are typically multiple forms, strengths, brands, and generic medicines available from various sources. Where some individual medicines are in short supply, alternative options such as alternative

strengths, brands, and generic medicines remain available to ensure continuity of treatment. In some cases where the medicine initially prescribed for the patient is unavailable, patients may be switched to a suitable therapeutic alternative following appropriate consultation with a healthcare professional. This approach is also consistent with national antimicrobial prescribing guidelines. “Suitable medicines continue to be available to treat respiratory illnesses and their symptoms in both adults and children. Taking into account the wide range of available medicines to treat respiratory illnesses, there is no need for healthcare professionals to order extra quantities of medicines, or for doctors to issue additional prescriptions. Similarly, patients and the general public are asked not to seek supplies of medicines over and above their normal requirements. Doing so will

disrupt existing stock levels and hamper the supply of medicines for others.

“Further to the HPRA’s regular and ongoing engagement with industry, we have been informed that in a number of instances suppliers have increased production and sourced additional stock to respond to this recent increase in demand. Although the HPRA has no role in procuring medicines, we continue to engage with the suppliers to obtain updates and remains open to expediting regulatory procedures to enable supply of additional stock, where possible.

“The HPRA fulfils a coordinating role in Ireland’s response to managing medicine shortages when they occur. In each case, the HPRA works with relevant stakeholders as necessary, to coordinate an effective approach to the management of a confirmed product shortage.”

The EU is preparing to stockpile drugs and oblige manufacturers to guarantee supplies in efforts to tackle the on-going medicines shortages.

The European Commission will also try to reduce reliance on China and increase domestic production capacity, the commission told the Financial Times — which reported the news. In a written response to the Greek government, EU health commissioner Stella Kyriakides outlined the plan.

The commission will intervene to ensure “strategic autonomy” in basic medicines through a “systemic industrial policy”.

It plans to propose legislation to “secure access to medicines for all patients in need and to avoid any market disruption of medicines”.

This would require “stronger obligations for supply, earlier notification of shortages and withdrawals and enhanced transparency of stocks”, the commission said.

This follows moves by the Greek health minister last week to bring in changes to address shortages there of inhalers and antibiotics. Greece is putting an export ban in place, but the Financial Times reports this is not being considered by the EU for now.

Greece is also listing alternatives to drugs which are in short supply, as is done in Britain.

This is something the Irish Pharmacy Union has repeatedly called for under the title of a “Serious Shortage Protocol” including calls made in early December when shortages became apparent.

Ms Kyriakides said in a written statement the commission was suspending some regulations and working with EU companies to increase capacity.

“Discussions with industry have already taken place and they are aware that they must rapidly step up production of these medicines,” she said.

Responding to the crisis, the International Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Association (IGBA), a Brussels-based industry group, told the FT that doctors are prescribing antibiotics more often.

It called on governments to share more information about their disease forecasts and loosen trade restrictions to allow drugs and raw materials to move more freely to countries with shortages.

They should also force wholesalers, pharmacies and hospitals to stop stockpiling antibiotics, according to the IGBA.

11

HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • FEBRUARY 2023

Warning signs of sudden cardiac arrest provide opportunity

Primary care visits rise sharply in the weeks immediately preceding a sudden cardiac arrest, according to results from the ESCAPE-NET project. The project is backed by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Resuscitation Council (ERC).

“Contrary to the general assumption, sudden cardiac arrest does not strike entirely unheralded, as ESCAPE-NET data have shown that patients attend primary care more often in the run up to an arrest compared to usual,” said Dr. Hanno Tan, ESCAPE-NET project leader and cardiologist, Amsterdam University Medical Centre AMC, the Netherlands.

“This insight may provide a lead for efforts to identify individuals at imminent risk of sudden cardiac arrest so that it can be prevented.”

Sudden cardiac arrest causes one in five deaths in industrialised countries. Most sudden cardiac arrests occur in the community in people not known to be at risk. A cardiac arrhythmia, called

ventricular fibrillation, causes the heart to stop pumping and blood flow ceases. If blood flow is not restored quickly, the individual passes out and dies within 10 to 20 minutes.

ESCAPE-NET was set up to improve both prevention and treatment. During the five-year EU Horizon 2020-funded scientific project, which concludes on 1 January 2023, scientists have investigated the causes of ventricular fibrillation so that it can be prevented and have examined resuscitation strategies in an effort to improve survival rates.

Developing effective prevention and treatment approaches required information on genetic and environmental risk factors from large study cohorts of sudden cardiac arrest patients – which were previously unavailable. The 16 ESCAPE-NET scientific partners joined forces to create a shared harmonised database of more than 100,000 sudden cardiac arrest victims. Dr. Tan said: “This resource can be used by scientists across

the world, including researchers outside of the ESCAPE-NET consortium, to conduct studies on sudden cardiac arrest. This should accelerate knowledge gathering on this condition and ultimately reduce the societal burden of sudden cardiac arrest.”

A biobank with DNA samples from 10,000 well-phenotyped sudden cardiac arrest victims has also been created. “This biobank will serve to increase our understanding of the genetic causes of sudden cardiac arrest,” said Dr. Tan.

More than 100 ESCAPE-NET research papers have been published in peer reviewed journals. Among them are European Heart Journal, Circulation, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Journal of the American Heart Association, Nature Genetics, The Lancet Public Health, Resuscitation, and EP Europace. Scientific discoveries include the finding that citizen-rescuers

provide less rapid resuscitation care to women than to men, and that women consequently have lower survival chances than men. Dr. Tan said: “This eye-opener must lead to public awareness campaigns aimed at narrowing the gender gap in sudden cardiac arrest management.”

Novel data have been collected on the sudden cardiac arrest risk associated with the use of various commonly used, noncardiac drugs in different European countries.4 Dr. Tan said: “This information may lead to the safer use of these drugs.”

He concluded: “Sudden cardiac arrest is a pressing public health problem that has so far been extremely hard to solve, largely because of the lack of difficult to obtain detailed clinical data and biological samples. ESCAPE-NET has made important steps by establishing a database, biobank and knowledge base that may be used in future studies to solve this problem.”

New Medically Led Platform to Tackle Obesity

and product designer Peter Lumley with support from senior team members including world-leading obesity scientists and clinicians, Professor Carel Le Roux and Dr Werd Al-Najim, UCD School of Medicine and UCD Conway Institute and Professor Alex Miras, Ulster University.

Beyondbmi, a University College

Dublin (UCD) HealthTech spin-out company supported by NovaUCD, has announced closing a ¤525,000 pre-seed funding round, advised by CKS Finance.

Beyondbmi has developed a 12-month weight management programme, designed by the leading medical weight management experts, to enable clients achieve long-term weight loss and health gain in a sustainable way. Beyondbmi uses the latest scientific research and therapies to create individually

tailored treatment plans which includes detailed assessments, medication, dietary plan, and behavioural health adjustments.

The funding will be used by the company to launch its proprietary Beyondbmi platform and demonstrate medical outcomes by giving people living with excess body fat access to doctorprescribed weight loss medication, nutritional therapy and one-to-one accountability coaching.

A UCD School of Medicine spinout Beyondbmi was founded by medical doctor Dr Harriet Treacy

Dr Harriet Treacy, co-founder, Beyondbmi said, “As a practising doctor, I have treated 100’s of patients who are experiencing health conditions they are not aware are a direct result of excess body fat. Conditions such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, anxiety and depression and increasingly, female health challenges like PCOS and infertility. Until now, I have had few medically-proven solutions I can point them towards to manage weight issues. This led me to spend time with global obesity experts to understand how we could design a solution which was based on the science of obesity.”

She added, “According to the World Health Organization it is now estimated that over 60% of the population are living with overweight or obesity with a staggering 220 health complications directly linked to these. Our mission at Beyondbmi is to provide a scientificallybased alternative to the outdated approach of ‘eat less, move more’ which, research has shown, is an ineffective long-term approach to weight management. For too long, the symptom of hunger associated with excess fat accumulation has been treated as an issue of willpower which causes untold harm to people who often internalise the failure of the treatment as a personal or moral failure.”

“Thankfully, we now have more effective solutions in the form of new medical drug treatments, combined with nutritional therapy and behavioural support which targets the underlying biology responsible for the feeling of hunger. This results in, on average, 15% weight loss over little more than a year as demonstrated in the STEP trials, and we are excited that Beyondbmi will provide a solution that aims to deliver these results in a real world setting.”

12 FEBRUARY 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

Professor Alex Miras, Dr Harriet Treacy, Professor Carel Le Roux and Dr Werd Al-Najim.

News

Credit: Maura Hickey

SUSPECT ATTR-CM

(TRANSTHYRETIN AMYLOID CARDIOMYOPATHY)

A LIFE-THREATENING DISEASE THAT CAN GO UNDETECTED

Life-threatening, underrecognized, and underdiagnosed, ATTR-CM is a rare condition found in mostly older patients in which misfolded transthyretin proteins deposit in the heart.1-7 It is vital to recognize the diagnostic clues so you can identify this disease.

CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING CLINICAL CLUES, ESPECIALLY IN COMBINATION, TO RAISE SUSPICION FOR ATTR-CM AND THE NEED FOR FURTHER TESTING

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in patients typically over 60 years old5-7

to standard heart failure therapies (ACEi, ARBs, and beta blockers)8-10

between QRS voltage and left ventricular (LV) wall thickness11-13

of carpal tunnel syndrome or lumbar spinal stenosis3,8,14-20

showing increased LV wall thickness6,13,16,21,22

H FpEF I NTOLERANCE DISCORDANCE DIAGNOSIS E CHO N ERVOUS SYSTEM

LEARN HOW TO RECOGNIZE THE CLUES OF ATTR-CM AT:

—autonomic nervous system dysfunction-including gastrointestinal complaints or unexplained weight loss6,16,23,24

3. Connors LH, Sam F, Skinner M, et al. Heart failure due to age-related cardiac amyloid disease associated with wild-type transthyretin: a prospective, observational cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133(3):282-290. 4. Pinney JH, Whelan CJ, Petrie A, et al. Senile systemic amyloidosis: clinical features at presentation and outcome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000098. 5. Mohammed SF, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, et al. Left ventricular amyloid deposition in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(2):113-122. 6. Maurer MS, Hanna M, Grogan M, et al. Genotype and phenotype of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: THAOS (Transthyretin Amyloid Outcome Survey). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(2):161-172.

7. González-López E, Gallego-Delgado M, Guzzo-Merello G, et al. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(38):2585-2594. 8. Narotsky DL, Castano A, Weinsaft JW, Bokhari S, Maurer MS. Wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: novel insights from advanced imaging. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(9):1166.e1-1166.e10. 9. Brunjes DL, Castano A, Clemons A, Rubin J, Maurer MS. Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in older Americans. J Card Fail. 2016;22(12):996-1003. 10. Castaño A, Drach BM, Judge D, Maurer MS. Natural history and therapy of TTR-cardiac amyloidosis: emerging disease-modifying therapies from organ transplantation to stabilizer and silencer drugs. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20(2):163-178.

11. Carroll JD, Gaasch WH, McAdam KP. Amyloid cardiomyopathy: characterization by a distinctive voltage/mass relation. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:9-13. 12. Cyrille NB, Goldsmith J, Alvarez J, Maurer MS. Prevalence and prognostic significance of low QRS voltage among the three main types of cardiac amyloidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(7):1089-1093. 13. Quarta CC, Solomon D, Uraizee I, et al. Left ventricular structure and function in transthyretin-related versus light-chain cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2014;129(18):1840-1849. 14. Connors LH, Prokaeva T, Lim A, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis in African Americans: Comparison of clinical and laboratory features of transthyretin V122I amyloidosis and immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4):607-614. 15. Nakagawa M, Sekijima Y, Yazaki M, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome: a common initial symptom of systemic wild-type ATTR (ATTRwt) amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2016;23(1):58-63. 16. Rapezzi C, Merlini G, Quarta CC, et al. Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: disease profiles and clinical courses of the 3 main types. Circulation. 2009;120(13):1203-1212. 17. Sperry BW, Reyes BA, Ikram A, et al. Tenosynovial and cardiac amyloidosis in patients undergoing carpal tunnel release. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(17): 2040-2050. 18. Westermark P, Westermark GT, Suhr OB, Berg S. Transthyretin-derived amyloidosis: probably a common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis. Ups J Med Sci. 2014;119(3):223-228. 19. Yanagisawa A, Ueda M, Sueyoshi T, et al. Amyloid deposits derived from transthyretin in the ligamentum flavum as related to lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(2):201-207. 20. Sueyoshi T, Ueda M, Jono H, et al. Wild-type transthyretin-derived amyloidosis in various ligaments and tendons. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(9):1259-1264. 21. Phelan D, Collier P, Thavendiranathan P, et al. Relative apical sparing of longitudinal strain using two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. Heart. 2012;98(19):1442-1448. 22. Ternacle J, Bodez D, Guellich A, et al. Causes and consequences of longitudinal LV dysfunction assessed by 2D strain echocardiography in cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9(2):126-138. 23. Coelho T, Maurer MS, Suhr OB. THAOS - The Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey: initial report on clinical manifestations in patients with hereditary and wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(1):63-76. 24. Swiecicki PL, Zhen DB, Mauermann ML, et al. Hereditary ATTR amyloidosis: a single-institution experience with 266 patients. Amyloid. 2015;22(2):123-131.

The health information contained in this ad is provided for educational purposes only. Date of Preparation: February 2021 GCMA code: PP-RDP-IRL-0105

References 1. Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, et al. Amyloid fibril proteins and amyloidosis: chemical identification and clinical classification International Society of Amyloidosis 2016 Nomenclature Guidelines. Amyloid. 2016;23(4):209-213.

2. Maurer MS, Elliott P, Comenzo R, Semigran M, Rapezzi C. Addressing common questions encountered in the diagnosis and management of cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2017;135(14):1357-1377.

S U S P E C T A N D D E T E C T . I E

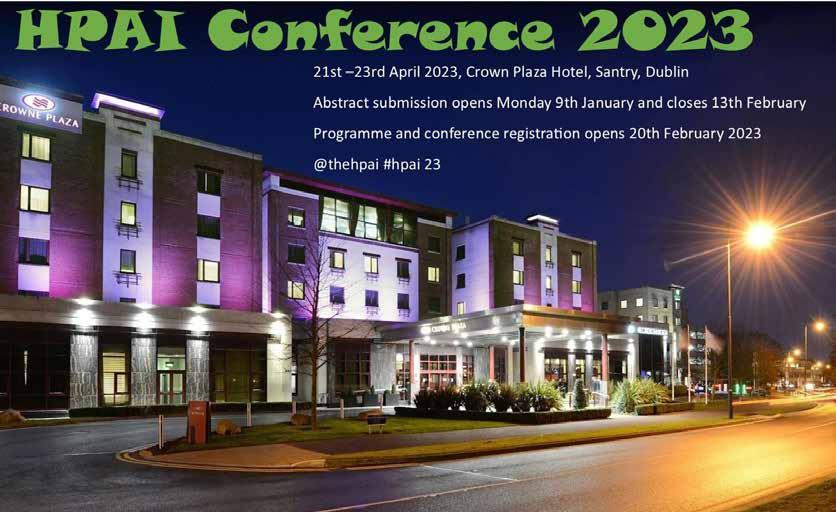

Precision Medicine and Novel Therapeutic Strategies in Detection and Treatment of Cancer: Highlights from the 58th IACR Annual Conference

Written by: Sean P. Kennedy1,*,Oliver Treacy2, Emma H. Allott3,4, Alex J. Eustace5, Niamh Lynam-Lennon6, Niamh Buckley7 and Tracy Robson8

1School of Biological, Health and Sports Sciences, Technological University Dublin, D07 ADY7 Dublin, Ireland

2Discipline of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Galway, H91 TK33 Galway, Ireland

3Patrick G. Johnston Centre for Cancer Research, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7AE, UK

4Department of Histopathology and Morbid Anatomy, Trinity Translational Medicine Institute, Trinity College Dublin, D08 HD53 Dublin, Ireland

5National Institute for Cellular Biotechnology, Dublin City University, D09 NR58 Dublin, Ireland

6Department of Surgery, Trinity St James’s Cancer Institute, Trinity Translational Medicine Institute, St James’s Hospital, Trinity College Dublin, D02 PN40 Dublin, Ireland

7School of Pharmacy, Queen’s University Belfast, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 7AE, UK

8School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, Royal College of Surgeons Ireland, D02 YN77 Dublin, Ireland

The Irish Association for Cancer Research (IACR) held its 58th annual conference from the 30th of March to the 1st of April 2022, in Cork, Ireland. The following article is a report of knowledge conveyed at the conference. There was a focus on cancer prevention in both “Early Detection” and “Cancer Vaccines” sessions, and cancer treatment in “Novel Therapeutics” and “Breakthrough Research” sessions. The research presented at this conference highlighted the interplay of both prevention and treatment, as many speakers focused on the same cancer but at different times in the treatment process. There was a push for more non-invasive early detection techniques, the current impact of cancer vaccines and new ways of further stratifying selection criteria for easier identification of high-risk individuals. This was coupled with novel treatment strategies and identification of new therapeutic targets.