Supporting Occupational Health Professionals for 30 Years

Supporting Occupational Health Professionals for 30 Years

Welcome to the Autumn 2022 Edition of OH Today.

This month iOH celebrated it’s 30th Anniversary. My writing this time will focus on this milestone but please enjoy the wonderful articles in this wonderful edition.

On the 1st October 1992 The Association of Occupational Health Nurse Practitioners was born. Originally set up to develop and promote the professional leadership in the practice of OH Nursing.

The founding values:

Promote – to actively represent and promote the practice of Occupational Health nursing

Influence – to support and influence the learning and development of occupational health nursing through participation in curriculum development and occupational health standards.

Support – to support and promote continuing professional development of Occupational health nurses.

Benchmark – to work in association with other relevant agencies to benchmark and research occupational health nursing practice.

Network – to provide a network of professional expertise and support.

From humble beginnings and still with a handful of volunteers we still focus on all the founding principles as well as a much bigger emphasis on the continuing professional development of our members.

On the initial setting up of the Association, critics initially suggested that the specialism was too small to have more than one voice representing its views. Founding AOHNP president, Carol Cholerton, spoke to Helen Kogan in 1993 and argued that the more voices that shout, the louder the noise (Cholerton, 1994). And with this positive message to focus our enthusiasm we have progressed from having a handful to almost 750 current active members. A loud noise indeed!

In comparison with our previous and current vision, mission and values it is clear as to the progress and focus that has become the bedrock of our success.

Confident Occupational Health Professionals empowered to participate in and influence the health and wellbeing of the working age population of the UK and beyond.

Mission

Supporting Occupational Health and wellbeing professionals through their career and personal development through practice education and training

Values

• We value integrity, honesty and recognise our unique contribution

• We welcome all Occupational Health Professionals equally

• We value accountability and promote quality through continued reflection and improvement

• We use a person centred approach, realising individual potential

Aim 1:

To provide a responsive, supportive and innovative service

Objectives

• Deliver and expand a variety and range of training to meet identified need

• Increase opportunities of professional and personal development through the provision of support services

• Increase access to services and service effectiveness through strategic promotion, networking and collaboration

• Provide a safe, secure fit for purpose learning/working environment

Aim 2:

To be a catalyst for Occupational Health community development

Objectives

• Seek opportunities to maintain and develop intra and inter community interaction

• Engage with existing and develop strategic networks and opportunities for collaborative working

• Promote and share Occupational Health and Wellbeing best practice with relevant employer bodies, voluntary and statutory sectors

Aim 3:

To grow and sustain an effective organisation

Objectives

• Build sustainable revenue through a variety of restricted and unrestricted income streams

• Develop and implement support services and continuing professional development services

• Ensure sound organisational governance through an appropriately skilled Board of Directors

• Recognise and value staff and volunteer expertise and provide opportunities for continued professional development

• Maintain and promote iOH as a recognised quality evidence-based organisation

• Maximise organisational effectiveness through actively seeking collaborative working opportunities

In order to achieve what we have over the last 4 years we have had to refocus and develop our unique selling point as well as restructure what services and benefits we can deliver as an Association that is staffed purely by volunteers. This ensures that we are fit for purpose and listening to our membership to provide the best value for money.

The immediate past president and my personal mentor, Lucy Kenyon has said this of what has been achieved over the last 4 years:

“I can only sit back in admiration of how Neil & Lynn have reinvigorated the professional membership model since 2018 following our somewhat brave decision to focus entirely on professional resources and support rather than membership subscriptions. In my opinion, they have catapulted the membership experience and reputation of iOH onto a research and development footing.”

Our Founding President said this to me in a recent phone call, “iOH’s recent success is down to standing up and being heard. Team iOH has done a wonderful job” .

iOH’s recent success is down to standing up and being heard. Team iOH has done a wonderful job

Carol’s lifetime Mantra has always been “No one should suffer any kind of illness as a result of the job they need to do to earn a living”.

Past Presidents, that are certainly worthy of a mention here, of AOHNP / iOH are:

1. Carol Cholerton – Founding President

2. Gail Cotton

3. Elizabeth Hughes (deceased)

4. Judy Cooke

5. Kim Boggins

6. Jeremy Smith

7. Christina Butterworth

8. Diane Romano-Woodward

9. Lucy Kenyon

The recent highlight for me as 10th President was to be able to lead and introduce 21 for 2021! A series of 24 webinars of the highest quality to the membership and indeed to the wider OH Community. 1500 bookings were made to attend those webinars which ranged from Introduction to British Sign Language, Critical Reflection, Writing at Masters level, Spirometry, Menopause, Prostate Cancer and IT accessibility, to name just a few. All recordings are still available at our YouTube Channel. I am drawn also to write about OH Today and how big a journey we have been on in comparison to the first edition newsletter. The journey is a testament to the many authors over the years that have made such an impact on the profession as a whole. It is also a testament to the recent hard work and

dedication of the Editorial Team, Lynn Pratt and Janet O’Neill. Under their watch it has become a Journal and attracts worldwide recognition.

Finally, I am honoured to be the 10th President of iOH. During my Presidency we have seen the sharpest rise and biggest number in membership in the 30 year history of the Association. We have also devised and succeeded in the biggest transformation in terms of our identity and aspirations for the future of our Association. Widening membership eligibility and encouraging collaboration of the wider Occupational Health & Wellbeing team. This has been a massive undertaking and is down to the members for their belief in the values that we have displayed to ensuring the continued success of the iOH. For that, I humbly thank you.

To reiterate Cholerton’ s (1994), wise words, “the more voices that shout, the louder the noise!”

Neil Loach President, iOH

References:

Cholerton C. (1994) “The more voices, the louder the noise?. Interview by Helen Kogan.” Occup Health (Lond). 46(3):93-4. PMID: 8028838.

iOH, The Association of Occupational Health & Wellbeing Professionals, (2022) Corporate Aims and Objectives. Available at: https://ioh.org.uk/about/corporate-aims-and -objectives/ (Accessed: 03 October 2022)

This article is a shout-out for growing Occupational Health and Wellbeing (OHWB). We must broadcast the narrative to our teams, networks, and peers. There is nothing more powerful than people spreading the word. As Carol Chorleton said 30 + years ago when starting OH Today, “the more voices that shout, the louder the noise!”

What is it all about and why on earth does it matter?

Dr Anne De Bono put the “Why” very simply in her recent talk on Growing OHWB at the Trent Occupational Medicine Conference (October 2022) as being

1.not enough OH professionals,

2.key drivers

3.evidence of OH effectiveness

What does this mean?

Point 1. OH, has been a shrinking speciality (DWP 2019) for some years now due to an ageing workforce but also because OH is not part of the NHS. This means OH is funded by employers as opposed to the government (compared to all other healthcare), therefore falling outside of the usual pathways of training in most cases. OH is not part of the general Doctor, Nurse and Associated Health Professional (AHP) (e.g. physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy) undergraduate education and consequently, awareness of OH as a potential career option has been small, with most people falling into OH as opposed to deliberately choosing it as a career.

Point 2. What are the key drivers for this move to Grow OHWB? At some point, it was noticed that hundreds of thousands of people were moving into worklessness each year and on to

benefits! Several publications demonstrated the positive effects of good work on health, culminating in the DWP 2013 evidence and research. This focused attention on the need for a healthy and safe work environment for all individuals, including those with health conditions; how could they be enabled to remain in work? Creating a more equitable society, enabling those with differing abilities (DWP 2016) to access and remain in work, reducing health inequalities (Marmot 2010) and supporting those who become ill, to return to work timely, were major factors. All evidence points to a 90% chance of worklessness after a year of absence. In 2019, a consensus statement on health and work was published (CWH) supporting the need for healthy and safe working environments for individual health and the well-being of colleagues, as well as work as a health outcome.

There is nothing like a pandemic to highlight the importance of health at work and those who protect it! We don’t need to go into the detail of the bearing the pandemic had on people and the work arena, especially frontline workers, as we all know the effects were substantial. Mental health, general health, well-being, and chronic health conditions became significant workplace concerns, not forgetting the risks within the workplace. We’ve always been aware of workplace health risks, but COVID brought these to the top of everyone’s thinking. People were, and are still to

some extent bruised and dented, with a new way of life being experienced by many.

Point 3. Those of us working in Occupational Health have always had a conviction that the service we deliver is essential for people, organisations, and wider society, including the economy. Workplace health and well-being, including the influence of OH, had been a strong topic in Dame Carol Black’s 2008 “Working for a healthier tomorrow” and the “Boorman review 2009”, driving health and wellbeing. After all, OH looks after the holistic health of people in the workplace, “how health affects work and work affects health”, alongside population and public health. We can be the whole package, especially with the use of a multidisciplinary team, a positive consideration for preventative workplace health, identified as far back as 2001 (Kopias). The business case for OH was made quite clear in SOM’s The Value Proposition 2017 and substantiated within 31 mentions in the DWP 2019 “Health is everyone’s business” report, the government proposal to reduce ill-health-related job loss where we were identified as a key driver in reducing sickness absence.

Pre-pandemic OH had been identified as a key part of “expert-led, impartial advice to help employers provide workplace support to employees”. Postpandemic, it gives us an enormous sense of pride when OH is cited as having

played a critical role in supporting the COVID-19 response. OH excelled, devising, and delivering new and appropriate services at record speeds, working with highlighted risks like ethnicity, and chronic illness and not forgetting the social aspects of vulnerable family members, like never before. Flexible, agile, responsive, and providing independent and impartial advice, OH demonstrated leadership and strategy that we know organisations appreciated and, in some instances, (anecdotal) saved millions. We have demonstrated our worth and this has been recognised.

The ONS report that 75.4% of the population aged 16 to 64 are in work, with a significant rise in the number of those aged over 65 also working. Covid risk assessments, undertaken by OH during the pandemic, identified individuals still working in their 90s! That is a lot of people within a large range of the population, demonstrating the potential impact OH could have! However, evidence suggests (SOM 2021) that only 30 to 37% of those in work have access to OH support via their employer, a figure, the government in their 2021 response to the “Health is everyone’s business report”, wishes to address. They realise that employers who invest in the health and well-being of their employees have fewer sickness absences, increased productivity, and a lower staff turnover. OH support employers and management with a preventative approach, healthier

workplaces and individualised care.

OH has brought about a wealth of good to organisations and people, especially notable over the COVID period. We need to ensure the momentum persists to expand the workforce and ensure quality and leadership development. Early in the pandemic (Personnel Today 2020), it was identified that there was a need to promote the value of OH and invest in training. Fortunately, this was picked up in the Government response to Health is everyone’s business (2021).

The NHS is the biggest employer in Europe and was probably the hardest hit in the pandemic for obvious reasons. Improving performance and capability alongside an improved experience for patients (NHS Long-term plan) is, therefore, a priority. Steve Boorman in 2009 put NHS people at the forefront of achieving these objectives, backed up by the 2022 People plan, Health and wellbeing framework In July this year, MP’s in a 2021 report cited understaffing as being a serious risk to patient safety. The obvious answer is to train and employ more staff, but NHS England’s People plan saw beyond that. They could see that investing in health and wellbeing would go a long way to retaining staff, improving productivity and morale, and therefore improving patient safety. Taking the long view, they prioritised

• “Looking after our people with quality

health and well-being support for everyone”

• “in a compassionate and inclusive culture by building on the motivation at the heart of our NHS to look after and value our people, create a sense of belonging and promote a more inclusive service and workplace so that our people will want to stay”.

The NHS England’s Growing Occupational Health and Wellbeing

Together Strategy (June 2022) supporting the NHS People Plan and People Promise of ‘we are safe and healthy, sets out a united vision and areas for action that can be achieved together based on four strategic drivers:

• Growing the strategic identity of OHWB

• Growing our OHWB services across systems

• Growing our OHWB people

• Growing OHWB impact and evidencebased practice

“This is an important moment for us as NHS OHWB professionals, as it:

• Unites us as a multi-professional family supporting the health and wellbeing of our NHS people, to enable them to pass good care onto patients

• Sets the national direction of travel for us as a profession, co-designed with

us, and puts us in the driving seat to grow our services

• Acts as a strategic lever to encourage investment and collaborative action in us as a community and the services we lead”

This very much supports the importance of a healthy and safe working environment, advocated by the 2019 consensus statement and the Growing a Healthier Tomorrow with its overriding message of utilising Occupational health (OH) and health and wellbeing (HWB) in providing excellent support to health care staff so they can provide excellent support to patients.

To achieve this, NHS Health Education England (HEE) 2019 advocated occupational health be prioritised as a frontline clinical function with appropriate funding to provide ‘proactive, responsive support to all NHS staff’. The Growing OHWB Together strategy unites occupational health and wellbeing as a multiprofessional family of job roles and services that collaborate to improve the health and well-being of our NHS workforce

This is all great work but if we look at the time lag between the Boorman report in 2009 to now, we know that we cannot just deliver a great document and leave it there. Short-term limelight can fade into the sunset. We must keep the momentum going and this means a strategy! July 2022 saw the publication of a roadmap to growing OH&WB, not

only to shout out the message of OH&WB as an integrated, multiprofessional family with a strong voice in organisational decision-making relating to health and wellbeing but to build on this with 4 key points: Let’s look at these individually:Growing the strategic identity of OHWB is shouting out about who OHWB are, building on the momentum of the pandemic, and encouraging people to sit up and listen by becoming a trademark of employee health and wellbeing. Investing and uniting the multidisciplinary team looking after NHS employees into one integrated team, will enable us to be one, reliable voice who is listened to.

Growing OHWB services across systems is inspiring and fundamental in caring for the carers! It supports an inclusive service that is driven by need, is well staffed, has joined-up, collaborative services with clear pathways for access encourages quality and innovation and maximises the use of technology including digital ways of working.

Growing our OHWB people is incredibly exciting as this supports the development of a multidisciplinary workforce with attractive career pathways, recognising and encouraging talent. Made possible with accessible training, good quality education and leadership development. Leading in health and wellbeing includes upskilling all NHS managers to support the health

and well-being of their teams. If anyone is interested in the NHS education and training opportunities within the Growing OHWB programme, please contact: growing.ohwb@nhs.net

Growing OHWB impact and evidencebased practice looks at data and research to drive quality and practice, demonstrate the impact and value of OHWB and therefore increase trust and confidence in the service but also drive the OHWB market.

In a nutshell, this is about being a multiprofessional service that is trusted by all employees and NHS leaders by having attractive career pathways, credible education and training and empowering our OH and wellbeing leaders with the wider workforce to move from transactional to transformational with a voice at board level (Dr A Turner, Personnel Today 2022)

NSOH is part of Higher Education England (HEE), the education subsection of the NHS, but is also a collaboration with the Faculty of Occupational Medicine (FOM) a different way of working to other schools because OH is unique in the world of health and not funded by the NHS. The school is headed up by Dr Ali Hashtroudi and has a vision which supports the training of the OH workforce, i.e., the multidisciplinary

team, to have the “capability and capacity to optimise the workability of the working-age population”. A significant focus is the quality of OH education and training, working with partners like Higher Education Institutions. As you can tell this vision fits in well with all the drivers we have already talked about, however, instead of just focusing on one sector, the school covers all sectors of OH delivery. For those who aren’t aware, OH, is delivered in two ways; - in-house provision i.e., paid for and supported by the employer and privately via OH providers. Some in-house OH departments also deliver privately externally such as in the NHS but also some private providers deliver to the NHS, local councils, and the private sector.

The school covers all OH delivery, as part of the 2021 Government response to Health is everyone’s business, including the need to grow the capacity of OH, i.e., workforce planning. This is an exciting time for the school, working as a strategic partner with the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) Work and Health Unit (WHU) and other stakeholders such as the Growing OHWB together team, FOHN, SOM, Council of Work and Health, COHPA and ACPOHE, to meet the need of future workforce planning, not only to grow the OH workforce but to grow awareness of OH as a future career.

One initiative is the development of

shadow opportunities for those interested in the inner workings of OH, facilitated by the Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) (please email admin@som.org.uk for more information), as well as the development of placements for Nurse and Allied health professional undergraduate students within OH departments and organisations. We are actively seeking placement opportunities so if anyone is reading or listening to this and would like more

information on what this involves, please contact Janet.Oneill@hee.nhs.uk.

The benefits of having a placement are numerous and include an opportunity to teach and supervise; upskill with exposure to best practice, knowledge, and skills; as well as obtain assistance with projects, audits, and service delivery. There is a small placement tariff that can be claimed for each student.

Janet O’Neill, Deputy Head National School Occupational Health (NSOH) (HEE) and Clinical Education Director, PAM Group

Victoria Small, Senior Project Manager Growing Occupational Health and Wellbeing, People Directorate NHS England

Janet O’Neill, Deputy Head National School Occupational Health (NSOH) (HEE) and Clinical Education Director, PAM Group

Victoria Small, Senior Project Manager Growing Occupational Health and Wellbeing, People Directorate NHS England

It has been evident more and more referred to Occupational over the past year post or LC (Long covid)

Long Covid (LC) is to define post-covid longer than 12 weeks. new, recurring, and that present following infection. The main with LC are fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, neuropsychiatric conditions memory and mood

Although the prevalence

Introduction

evident in my practice that more individuals are being Occupational Health (OH) (2021-2022) due to covid) symptoms.

an umbrella term used covid symptoms lasting weeks. It refers to several and ongoing symptoms following initial covid main symptoms associated fatigue, breathlessness, dysfunction, and conditions such as mood (Raveendran, 2021).

prevalence of LC within the

UK is not fully established, The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has estimated that 1in 10 people are affected by LC, within the UK alone. Due to the debilitating and fluctuating nature of LC, the evidence suggests that the effects will have negative implications on an individual’s daily functioning and their ability to remain at work and/or sustain a successful return to work. This poses challenges for both the individual and society (Rayner and Campbell, 2021).

The aim of undertaking this literature review was to understand the part OH practitioners (OHP’s) could play in the rehabilitation and recovery of individuals with suspected or confirmed LC. When searching, it was evident that, due to the recency of the condition, the literature surrounding LC and work is limited. The most widely available literature focuses on the definition of LC and its impact on individuals’ daily functioning, with only some research centred around its impact on work/employment. Additionally, very little research was found on the role that OH plays in the recovery/rehabilitation of individuals experiencing symptoms of LC. Therefore, the focus became the effects of LC in the workplace to make recommendations for practice based on the limited research available and in comparison, to other long-term

debilitating / fluctuating conditions (Wong and Weitzer, 2021).

Recent studies investigating the effects of LC concluded that the most prominent symptoms, 6 months postinfection, were fatigue, post-exertional malaise, and cognitive dysfunction with a substantial impact on daily life and work (Davis et al., 2021 C. Huang et al., 2021; L. Huang et al., 2021; Righi et al., 2022).

Two Scandinavian registry-based studies highlighted high-risk groups for long-term sickness absence (LTW) and emphasised how sick leave can be used as an indicator of well-being in the working population. They went on to provide insight into the burden of LC on the workforce by examining return to work trends and predictors of longterm sick leave (Jacobsen et al., 2022; Westerlind et al., 2021). The evidence available so far suggests that older age, severe Covid-19 illness (requiring hospitalisation), female gender and comorbidity were indicators of a reduced likelihood of returning to work within 6 months of infection. Jacobsen et al., (2022) hypothesised that due to the long-term health consequences of

LC, those who remained absent for more than 6 months were more vulnerable to early retirement and/or unemployment.

Although there is evidence of individuals reporting a wide variety of symptoms including but not limited to; fatigue, myalgia, breathlessness, cardiac/ gastrointestinal distress and cognitive deficits, the true burden of LC remains unclear (Datta, Talwar and Lee, 2020). The studies above highlighted that even if a small proportion of the millions of people infected with covid-19 go on to develop LC, the scale will have significant implications for public and global health. The main challenges that LC will present clinically are the need for long-term treatment and occupationally are thought to be long-term-term absences, presenteeism or early retirement (Michelen et al., 2020 Rayner and Campbell, 2021; Mathew, 2022). It is therefore imperative for OHPs to gain further understanding of disease presentation, prevalence, and proposed treatments for LC.

Recommendations for Practice:

OH, specialists are well versed in conditions that adversely affect individuals’ daily functioning, ability to work or ‘work well’, and conditions that require multiple interventions for treatment/management purposes (Puchner et al., 2021).

Despite the recency of the condition, OHPs could play a key role in the support and management of employees experiencing LC for varying reasons: -

• OHPs use well-validated assessment tools, clinical guidelines, and a comprehensive approach during OH assessments, to provide clinically

sound, beneficial advice to the employee and management.

• The comprehensive approach used in each assessment enables OHPs to examine employees’ biological, psychological, and social circumstances, matching this to their daily functioning and work.

All the above enables OHPs to aptly advise and signpost the employee experiencing LC symptoms to personalised rehabilitation interventions (Carter et al., 2015; Barnes and Sax, 2020; Godeau et al., 2021) which could include a personalised multi-disciplinary rehabilitation approach. Evidence available highlights that treatment and management of LC focused on improving physical capabilities. i.e., breathing and mobilisation rehabilitation interventions. In addition, psychological interventions such as CBT and complementary behavioural modification are likely to improve long-covid patients’ well-being and mental health (Yong, 2021). As previously cited, fatigue appears to be the most widely reported LC symptom and therefore OHPs may benefit from looking for guidance of fatigue-related conditions such as ME/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). The gold standard treatment management advice for this is pacing, graded exercises and when warranted, CBT (NICE, 2021). OHPs are commonly able to refer and/or signpost patients to specialist services as highlighted above due to previous knowledge of other longterm condition management with symptoms that mirror long-covid (Rogers et al., 2014).

Advising and supporting a safe and sustainable return to work is a key aspect of OH services. The HSE (Health and Safety Executive) and CIPD (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development)

have published reports to inform appropriate guidance for employers and health professionals in supporting employees returning to work following absences due to long-covid. The main guidance provided is supporting the employees in the management and selfcare of their condition. This includes ensuring employees have been adequately signposted to dietary, physical, and psychological resources whether online, in-house or via their GP. They also highlight that access to work adjustments and flexibility i.e., phased return to work, initial reduction to caseload and allowance to attend medical appointments, would allow for symptom management and the likelihood of a sustained return to work. LC is likely to have negative implications on the workforce. However as highlighted above,

OHPs and services are well equipped in supporting and managing employees’ health needs at work. This can be achieved by utilising emerging scientific evidence and previous knowledge and expertise relating to relapsing and remitting long-term conditions with similar manifestations (Burdorf, Porru and Rugulies, 2020; Sinclair et al., 2020). This research topic was of particular interest, as it is evident in the authors’ place of practice that more and more individuals are being referred to OH over the past year (2021-2022) due to post or long covid symptoms. Symptoms are as described and impact the ability to return to work as noted in this research. The advice to support individuals is consistent with business as usual for OHP’s when dealing with chronic multi-symptom conditions.

Phina is an experienced nurse who is currently studying for a specialist community public health nursing qualification, focusing on Occupational health. She is particularly passionate about community health and is a trustee of a charity centred on tackling mental ill-health within the African / Caribbean communitiesBaba Yangu foundation. She works for PAM group which she says has been instrumental in her growth as an OH practitioner.

By Hardev Singh Agimal,

By Hardev Singh Agimal,

We may not realise it, but we set goals most days. Our goals can look very different depending on our lifestyles, values, needs, and our own definitions of success. The more classic understanding and definitions around goal setting is simple: it’s the process of identifying something we want to accomplish and achieve and establishing a method and process to achieve it, and a timeframe in which we wish to achieve it by (Robbins, 2021). We do this most days for ourselves. We think about something we want to achieve, how to achieve it, and when to achieve it. These can be smaller-scale tasks like cooking dinner or larger-scale DIY projects: so why is goal setting with and for our patients so difficult? We know that a collaborative approach to goal setting, and setting regular short-term targets and goals often leads to greater success (Cambridge University Press, 2021 & Robbins, 2021), yet goal setting seems to be something that can be overlooked in Occupational Health.

• We should regularly review the goals we set

• We could use a set schedule to review short-term and long-term goals – this can highlight any goals which may become unattainable and if there are any obstacles to achieving the goals

• Stay flexible when setting and reviewing goals

• Make changes to our goals were necessary

A “SMART” approach to goals will help us when we are working with our service -users. SMART goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Timely (HealthStream, 2018 & NHS

Greater Glasgow and Clyde, 2021), and there are some points to think about below then looking at each of these sections:

Specific:

What are we going to do?

How are you going to do it?

Where are you going to do it?

When are you going to do it?

With whom are you going to do it with?

Measurable:

Making the goal specific, using some of the above prompts, measures that it should be easier to measure whether or not the goal has been achieved

Achievable:

Set goals that are within reach. Failing to achieve goals can have a negative impact on motivation and compliance to work towards a goal, so it is important to set a realistic goal that both challenges an individual, but is not so far out of reach that achieving the goal is seen as an obstacle or hindrance.

Relevant:

Do you believe the goals are relevant to you or the service-user? It is important for an individual to see a clear link between the goal and how this will impact the aspects of their health and wellbeing that are important to them.

Timely:

Is it the right time for this particular goal?

Always set a timeframe for a goal

Setting mini-goals can help an individual achieve ‘small wins’ to keep them motivated and helps them take steps to a more ambitious goal

SIt is important to work with individuals to help establish what is important for them right now, what is important for their future, what do they want to achieve, and what are their strengths. Our needs, our goals will be different. Some of us may wish to have goals start a family, or return to work, or learn a new hobby. When we are looking at goals in Occupational Health, we can use these to improve physical, social, and psychosocial health. We can set goals for an employee to meet a friend or replicate a work task at home. This could help someone feel less isolated and we are in a prime position to create an action plan to help people achieve these goals (Department of Health, 2011).

ARMGetting individuals to think about goals is hard. It often means we have to think about change, either within ourselves or our lifestyle and this has several barriers. Again, this puts us as healthcare providers in Occupational Health in a prime position. We can work collaboratively with individuals and get to think about change and goals in their own words. This will help with two things: 1) it helps individuals be more motivated with their goals, and 2) it helps take the emphasis away from us in setting those goals and offers a more person-centred approach and allows an individual to have greater responsibility over their care (Department of Health, 2011).

TMany individuals will have already set goals but are unaware. It is important to understand what an individual is doing to see how we can build on this. Having long-term goals is very common; however, short-term goals can often be missing. It can be important to use short -term goals over days or weeks to help

individuals achieve small steps to help work towards a bigger target (Department of Health, 2011).

Goal setting is at the heart of every organisation; we all have something that we are trying to achieve. We are in a unique position where we can work collaboratively with other employees and ensure our SMART goals are functional and this will help to aid recovery and their employers organisational goals. We are also in a position to prevent occupational accidents (Krstev, 2008) and reduce the risk of injury (Schaufeli et al., 2008) by ensuring our goals are tailored to each individual and their needs. A secondary benefit from this, is that employees may become more engaged and motivated in the workplace which can lead to improved performance (Bakker & Van Woerkomm, 2018).

Helping to set the right goals for each individual allows them to focus on their strong points, improve their weaker areas, feel engaged with their rehabilitation and recovery, and these can have lasting impacts in the workplace with increased motivation, self-worth, and psychological health (Van Den Broeck, 2008). Naturally, individuals will focus on the negatives. It is far easier to focus on what is not going well in our work and personal life; however, if we can help set the right goals through our rehabilitation pathways to encourage people to goals to overcome these negatives and create more positive environments for them to thrive in (Bakker & Derks, 2012).

• Goal setting is vital because it helps an individual decide and focus on what is really important and matters to them

• Effective, collaborative goal setting lets individuals measure progress, overcome procrastination, and achieve their goals

• Goals keeps the individual accountable. Whether it is in the workplace, your personal life, or your health, telling others about your goals make you more accountable and more likely to take the appropriate steps to achieve those goals

• Removing and resolving ambivalence is a key factor in motivating people to change. At Occupational Health, we can inform and advise, but ultimately it is the individual who decides whether to change or not

• We won’t always achieve our goals, or it make take longer than we think. We shouldn’t see this as a failure; particularly when it comes to those we support through Occupational Health. We are in a position where we should support the efforts achievements made, even if the overall goal has not been achieved.

• If our goals focus solely on output quantity, this can lead to lower quality and this can increase the risk of injury (Goerg, 2015). This can also lead to disengagement from the goal, because that output serves benefit to somebody else rather than the individual trying to achieve the goal.

• If the goals are not realistic and they are overly ambitious, then we can often take great risk in trying to achieve them.

• Failing to achieve and meet goals can lead to dissatisfaction and reduced motivation (Latham & Locke, 2006).

• If an individual lacks the understanding and knowledge to achieve their goal, individuals can use sheer effort and persistence which can result in a good performance but this can often be misplaced or misdirected so we don’t achieve our goals.

At Occupational Health, again we find ourselves in a unique position where setting goals can benefit the employer and the employee. If we set the right goals, and appropriate goals, and the risk of injury can be reduced this reduces the cost the employer as they require fewer Occupational Health referrals, and provides a more effective and efficient rehabilitation process to the employee.

Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012) “Occupational Health Psychology” Chapter 7: Positive Occupational Health Psychology

Bakker, A. B., & Van Woerkom, M. (2018) “Strengths Use in Organisations: A Positive Approach of Occupational Health.” Canadian Psychology 59(1), pages: 38-46

Cambridge University Press. 2021 “Goal Setting” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/goal-setting

Accessed: 31/03/2021

Department of Health. 2011 “Goal Setting and Action Planning As Part of Personalised Care Planning” Improving Care for People with Long Term Conditions https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/215951/dh_124053.pdf Accessed: 08/04/2021

Goerg, S. J. (2015) “Goal Setting and Worker Motivation” IZA World of Labour 178(1), pages: 1-10

HealthStream. 2018 “Healthcare Management & Administration Blog” Organisational Goal Setting in Healthcare: Best Practices https://www.healthstream.com/resources/blog/blog/2018/02/16/organizational-goal-setting-in-healthcare-bestpractices Accessed: 10/04/2021

Krstev, S. 2008 “Occupational Health Objectives.” Encyclopedia of Public Health 978 (1), pages: 5614-5617

Latham, G. & Locke, E. (2006) “Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting” Organisational Dynamics 35(4), pages: 332-340

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. 2021 “Goals and Action Plans” https://www.nhsggc.org.uk/about-us/professionalsupport-sites/cdm-local-enhanced-services/health-determinants/setting-goals/goals-and-action-plans/# Accessed: 05/04/2021

Robbins, T. 2021 “How Can I Create A Compelling Future?” https://www.tonyrobbins.com/ask-tony/can-createcompelling-future/ Accessed: 29/03/2021

Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M. & Taris, T. (2008) “Work Engagement: An Emerging Concept in Occupational Health Psychology.” An International Journal of Work, Health & Organisations 22(3), pages: 187-200

Van Den Broeck, A. (2008) “Self-Determination Theory: A Theoretical and Empirical Overview in Occupational Health Psychology.” Ku Leuven 82(2), pages: 63-88

Mindshift is proud to announce the launch of a brand-new book, aimed at Occupational Health Practitioners, but highly insightful for those working within HR, H & S and Management.

It will be selling for £34, and available via

https://mindshiftconsultancy.co.uk/ 5% of any profits will be shared between MIND and Nurse Lifeline

My aim within this book is to fill any knowledge-gaps you may have around the subject of mental distress and to increase your confidence and competence…

This book is packed with helpful information including :

• risk factors for and signs of mental distress

• supporting someone experiencing anxiety, depression, self-harming or suicidal behaviour, an eating disorder or psychosis

• tips on getting the most of your assessment

• useful phrases to use in your report

• templates for your notes and your report

• adjustments to support a recovery

• case studies

• detailed stress risk assessment and action plan

• recommendations on wider reading

• signposting to key resources

“Hi mate, how are you getting on?” “Really well mate, pain-free” “Oh, that’s brilliant. How’s your return to full duties been?” “Oh, I can’t do that. Doing that job is what put me here so I’m never doing those movements again it will break me. I need to take it easy”.

My daily consultations put me through a rollercoaster of emotions when listening to people talk about pain.

Pain is a complex issue that is multi-factorial and involves social, contextual, physical, and psychological factors; yet a large approach to the treatment frequently provided by musculoskeletal clinicians is focused on simply reducing the sensation of pain (Wainright 2019). This is an approach that is also favoured by patients as a study by Setchell et al. in 2019 demonstrated that people with persistent pain view passive modalities such as ice, heat, and manual therapy

By Luke Griffiths PAM Group

By Luke Griffiths PAM Group

more than active modalities such as exercise (Setchell 2019). While not validating an individual’s experience and never focusing on reducing pain would be reductionist and unhelpful, there is an argument that solely focusing on reducing pain with passive modalities, could be dualistic and not address the multi-factorial nature of pain. I ask during this article whether an approach that solely focuses on reducing pain is sufficient and truly peoplecentred. My aim is to open up a discussion that suggests potentially

more appropriate ways we can aim for a full recovery, beyond a reduction in sensation.

Pain is having a significant economical, societal, and individual effect on governments, employers, and individuals (Becker 2019). Pain is extremely distressing and statistics show a strong correlation with suicide, long-term sickness absence, and unemployment (Becker 2019) further shining the light on how pain worms its way into an individual’s life and spreads until it impacts all factors of well-being. Interesting research has shown that it is not just the sensation that causes people to feel down, depressed and isolated, it is the perceived limitation that comes with the experience of being in pain, shaped by thoughts, beliefs, memories, and self-efficacy (Boutevillain 2017). While I appreciate focusing on desensitization in the short term is essential for an individual’s lifestyle and overall well-being, I would argue that the passive modalities and some frequently used strategies for communication are not beneficial for long-term health, potentially contributing to the perceived limitations of sufferers as they fail to address the physical, psychological, and contextual barriers that are posed by full rounded recovery, especially in cases where a long-term history of pain is present (Belavy 2021).

In an attempt to explain the limitations of these approaches I use a phrase with my patients “the worst thing about rest is that it works!”. When the desired effect is solely to reduce the sensation of

pain, rest is perfect. The individual will find a comfortable position and the symptoms will reduce over time. As a result, this approach seems marvellous. It’s only when we start to consider other factors that influence recovery, such as deconditioning and fear avoidance, we realise that this approach falls desperately short (Borisovskaya 2020). Now let’s use heat intervention vs a graded exposure intervention to explain this concept further:

Initially, an individual presents with shoulder pain and following assessment, the clinician provides some advice and education to support continuing with all activities by reducing the load to a more manageable level. For an unspecified reason, this approach does not provide instant relief and the patient’s symptoms continue to worsen. During this time they start to notice specific movements that replicate their symptoms and as this happens more frequently thoughts and feelings towards these movements develop such as “I know my shoulder will be painful when I work overhead” or “doing the overhead movement is really bad for my shoulder which shows something is seriously wrong”. As more time passes, these thoughts and feelings are reinforced every time their symptoms increase, so “doing anything overhead is bad for my shoulder so I should never ever under any circumstances do overhead activities and this job is the sole reason I’m struggling now” becomes deeply imbedded and absolutely true. On the flip side, the individual is advised to try heat to reduce the discomfort so a hot wheat bag is placed on the affected area. As they relax with the nice feeling of the heat on their shoulder, the pain reduces

almost instantly. Thoughts such as “heat is really good and really helped to reduce my pain”. Over time, a similar reward process is created, resulting in “heat is the best thing since sliced bread” (Risvi 2021).

The complexity of this is that the heat has failed to address any of the beliefs about the movements required to fulfil the demands of their role, and the context alongside the implementation of these attempts to reduce discomfort is forgotten; even though the amount the person enjoys their job could be a nocebo, and the comfortable environment with the heat application could be a placebo (Rossettini 2021). This can be problematic as the thoughts, feelings, memories, and beliefs of the patient may eventually influence their future employment and overall wellbeing (Becker 2019). We can see the negative impact and shortcomings of solely focusing on pain as an outcome in this short example alone.

Especially as the issue isn’t that nothing works to reduce pain, the issue is that the research shows that most things work for reducing pain we just don’t know why they work (French 2006). As humans in general we have strong beliefs about the causal effect (DundarCoecke 2022), and as clinicians, this is reinforced through University as we are told to be detectives and find the route of the pain, then fix it. This is great initially as we can seemingly help people directly and get lots of praise for this, but this approach can make some into guru-like healers that provide outdated treatments and advice filled with confirmation bias and posthoc reasoning, rarely addressing the complexity of the situation (Caniero 2020). Challengingly, this approach also

fits in with patient expectations and the beliefs of the family members and friends of the patient (Beasley 2017), but I refer back to my previous point, does an approach that simplifies an individual’s struggle to a single factor that only you as a clinician can fix really help restore function in the heterogenous population we are exposed to in Occupational Health? Does person-centred care offer a menu for people to select their preferred treatment without evidence-based education? Ultimately, we do not know, and may never fully understand exactly why an onset of pain happens, or why specific treatments work (DundarCoecke 2022), but it is unlikely to be as simple as only posture, lifting technique, a lack of strength, or tight muscles (Powell 2021).

This is where our job as clinicians is so important! We have the opportunity to open up a person’s viewpoint. I believe that as a clinician we should provide a plan to people with short and long-term goals that reassure and builds confidence to reduce the reliance on specific modalities and increase selfefficacy to ensure the individual that they are strong, capable, and robust (Bernal-Urtrera 2020). Individuals do not have to be pain-free to return to work or live their lives (Shaw 2018). How often is the amount of anxiety we feel actually the amount of danger we’re in? The amount of hunger we feel replicative of the necessity for us to eat? There is a discrepancy between what our body tells us and reality; this also applies to pain. As musculoskeletal clinicians, we are blessed that we have more time with patients than most

health professionals, especially in private practice and occupational health. This valuable time can allow a patient to be heard so we can work towards suitable goals. Can we use this time to build meaningful relationships and provide essential education? From my experience, here are a few ways we can maximise our clinical time:

• Explain the non-physical benefits of the treatments that we choose

• Alter the contextual factors of pain where possible through positive communication

• Modify hobbies and work tasks to create new, more positive experiences

• Encourage individuals that pain does not mean that they are broken

Ultimately, the reason I’m writing this article is because of the frustration I feel with people who have been given advice

in the past that contributes to fear around returning to activities they enjoy due to reinforcing perceived weakness and fragility. I believe that our experiences in life are the most important thing. As musculoskeletal clinicians, we have a real opportunity to promote health and well-being, and support individuals in creating positive experiences. So, in summary:

• Provide short and long-term goals during your treatment

• Inspire people to continue with the things that they enjoy

• Listen and be empathetic to a person’s experience of being in pain, beyond the sensation

I hope that this article has given you some food for thought!

Luke Griffiths is an MSK Clinician at PAM Group

The world of work is changing, and for those at the frontline of occupational health today, there are significant challenges to managing worker health.

Occupational Hygienists, with expertise in early workplace risk identification and management, jointly navigate workplace health challenges that arise from a variety of sources, for example chemicals, fumes, noise, vibration, manual handling and more.

Proactively armed with scientific evidence, the advice and awareness we provide, supports future health protection and disease prevention. In other words, we can reduce illness and injuries before long-lasting detrimental health effects take hold.

In this article I examine the role of occupational hygienists, the workplace risks we must consider, and how we can work collaboratively to empower employers and those in occupational health, together creating complementary, informed, and effective multi-disciplinary teams.

An Occupational Hygienist is a science professional at the centre of exposure risk management. Our work aims to protect and enhance worker health by identifying potential hazards in the form of chemical, biological, physical, or ergonomic. We then identify and advise on what controls are required to minimise any risk to employees. This not only helps to protect employees, improve and enhance workplace conditions, but also ensures employers are legally compliant. Their responsibilities are divided into three categories:

1.To anticipate and identify hazards

– Often unaware of employees’ risk exposure, an employer may not realise that it is taking place or the levels to which it is.

Through a workplace risk assessment, we will determine what roles and work areas present a problem in terms of the potential health risk.

We will look at risks which include but are not limited to; chemicals under Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH); noise; hand-arm vibration; whole-body vibration; heat; asbestos; mould; legionella; and airborne contaminants such as dust and respirable crystalline silica.

Exposure to these even for a short period, if not controlled, can result in serious and in some cases, possibly fatal health consequences for the individual concerned.

2.Quantify and evaluate the risks from identifiable hazards – Once identified, expert measuring of risk takes place using a range of inperson and technological methods to determine the requirement of intervention. This ranges from personal exposure sampling and monitoring such as wearable technologies, Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV) testing, air quality sensors measuring Carbon Monoxide, humidity, CO², gases and temperature, blood or urine sampling and analysis, and background sensors.

3.Control the risk

– Using the hierarchy of hazard control, we advise and provide practical and cost-effective solutions to help eliminate, substitute and reduce exposure to the hazard. For example replacing isocyanate based paint sprays with alternative, nonisocyanate versions to reduce the risk of skin irritation and occupational asthma.

If elimination or substitution cannot take place, then the next step is technical or engineering controls such as modifying equipment or introducing ventilation. Adding or modifying LEV’s is a simple way to reduce airborne exposure. In one case we found that attaching an on-tool extraction system had a dramatic impact on the level of work related dust exposure. We were able to quanitify this with measurements.

Alongside this, we look at administrative controls in terms of changing the duration, frequency, and

intensity of a task. Finally, we ensure the correct and consistent use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and Respiratory Protective Equipment (RPE); Face Fit Testing respirators if required and managing PPE/RPE use.

How can occupational hygienists empower those in occupational health?

Both Occupational Hygienists and Occupational Health Practitioners (OHP’s) have the same goals which are to improve worker health, make employees’ lives better and support employers in meeting their moral and legislative responsibilities; yet with visibility of different parts of the workforce’s health journey we often work independently.

If we were to work together, this greater collaboration and a timelier sharing of knowledge would lead to proactive, rather than reactive, decisions around cause and effect, with long-term benefits.

For example, we could improve the health screening process by ensuring the OHP has advance knowledge of an individual’s potential exposure levels prior to a consultation. In turn OHP feedback on health outcomes would help to improve workplace controls.

In revisiting today’s public health challenges and the continued high statistics as noted by HSE in their 2020/21 key figures around worker illhealth, occupational health and hygiene specialists must strengthen their partnership. By realising their shared purpose people and organisations

everywhere will benefit from the improved management of worker health.

Ross Clark is Head of The Institute of Occupational Medicine’s (IOM) Workplace Protection team, which uses a mix of Ventilation and Occupational Hygiene services to protect hospital patients and workplace employees’ health. A veteran Occupational Hygienist, Ross Clark has been practising for over 20 years with an indepth working knowledge of industry issues and has led from the front during COVID -19.

Alongside IOM, more information on Occupational Hygiene can be found at the British Occupational Hygiene Society https:// www.bohs.org/

By Charlene Mhangami, Vitalograph

By Charlene Mhangami, Vitalograph

Occupational Asthma (OA) is a type of asthma caused by inhaling hazardous substances or irritants at work. It is important to distinguish between occupational asthma and aggravation of pre-existing asthma, as management and compensation can differ. There are two main forms of OA first described is sensitizer-induced OA caused by IgE-mediated or other immune responses to specific workplace agents i.e. high molecular weight sensitizers (animal proteins, flour, or natural rubber latex) and low-molecular-weight chemicals such as (diisocyanates, colophony). This type of OA develops after a latency period between the first exposure and the onset of symptoms. Secondly, is irritant-induced OA including reactive airway dysfunction syndrome which is caused by non-immunological stimuli which occur after accidental exposure to a very high concentration of a workplace irritant. Once a person has been sensitized to one of the materials, exposure in low quantities will exacerbate asthma1

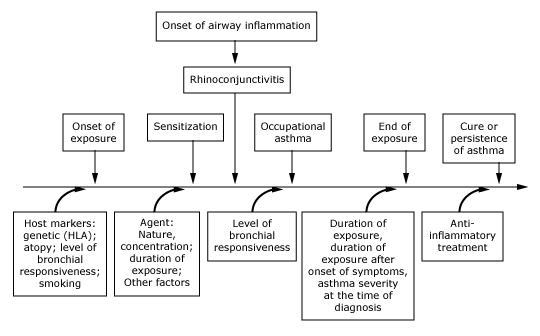

Figure 1 : Natural history of the development of sensitization and OA. Steps are in boxes above the horizontal line, whereas modulating factors are listed below2

According to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Health Surveillance ‘is a risk-based scheme of repeated health checks for the early identification of ill-health caused by work.’ In their latest documents on OA

‘Health Surveillance for occupational asthma’ they list the main causes of occupational asthma are; Isocyanates (e.g. two -pack spray paints), flour dust, grain dust, wood dust, latex, rosin-based solder flux fume, laboratory animals, cleaning products, enzymes, stainless-steel welding, aldehydes, glues, and resins3 .

They also list a group of high-risk occupational groups which include bakeries, food manufacturing, beauty industry, cleaning services, healthcare workers, spray painters, repairers (including electronics), welders, woodworkers (including forestry), workers exposed to metal working fluids, seafood processing, laboratory work, and detergent manufacturing3 .

exposure to the main causes of occupational asthma (above) or substances and processes where occupational asthma is a known problem;

exposure to substances labelled: – H334 ‘May cause allergy or asthma symptoms or breathing difficulties if inhaled.’

reliance on Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in workers exposed to substances which may cause OA;

a confirmed case of OA in your workers

People who get OA may have been healthy before and never had asthma or they may have had asthma as a child, and it returned. If the worker already has asthma, it may be worsened by being exposed to certain substances at work. Workers might be in a workplace for a while before symptoms are noticed because it takes a while for your immune system to become sensitive to workplace triggers. Once sensitization takes place it can trigger asthma symptoms the next time the worker encounters the trigger even in small amounts. Common symptoms are highlighted in figure 3. However, it is important to note people with a family history of allergies are more likely to develop occupational asthma, particularly to some substances such as flour, animals, and latex. But even if you don’t have a history, you can still develop this disease if you’re exposed to conditions to induce it. Also, if you smoke, you’re at a greater risk of developing asthma. If symptoms are detected early and exposure has been modified the risk of developing long-term asthma is reduced.

Recurring sore or watering eyes

Recurring blocked or running nose

Bouts of coughing

chest tightness

shortness of breath

wheezing

any persistent chest problems

if any symptoms experienced improve at weekends or during holidays

Initial diagnosis of OA involves a consultation with a doctor, to go over the prevalence of symptoms when they occur, type of work, and medical history, example questions are highlighted in table 3.

Did your asthma symptoms start as an adult?

Have your childhood asthma symptoms come back since you started working?

Do your symptoms get better on days you’re not at work or when you’re on holiday?

Do your symptoms get worse after work or disturb your sleep after a work day?

Do you have a history of allergies which could increase your risk of allergies at work?

Do you smoke, which increases your risk of being sensitive to work triggers?

Do you have rhinitis? Occupational rhinitis is an early warning sign for occupational asthma

However, a diagnosis of occupational asthma should not be made based on a positive history alone, diagnostic tests performed in secondary care are highly valuable in aiding the diagnosis, the tests include:

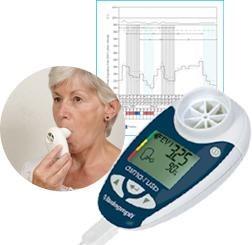

Spirometry test - This is a lung function test where a person will need to take a deep breath and blow air out into the spirometer forcibly. Spirometry is measuring the breathing capacity and airways cross-sectional areas of the lungs. It is particularly useful in determining the presence or absence of obstructive lung disease among workers. Tests should include the 1- second forced expiratory volume FEV1, the forced vital capacity FVC and the ratio of these two measurements. Quality spirometers must be used for annual spirometry testing because charting the annual decline of lung function over the employment period will be impossible without accurate measurements. A decline of 30mL per year is normal; over 100mL a year is abnormal. As these levels of change are relatively small, it is essential that the spirometers used for testing are not just highly accurate but are consistently so over time. Those performing spirometry testing need to be confident that the test results and year-on-year comparisons can be relied upon.

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test—The FeNO test measures the amount of nitric oxide present in the breath, which can determine the presence of inflammation in the airways, which might indicate asthma5 .

Peak Expiratory flow (PEF) – The worker is provided with a peak flow meter and is instructed to provide serial measurements of peak flow at and away from work. For the readings to be useful at least four readings a day should be obtained for three weeks. A serial record of PEF is suggestive of work -related asthma where is a consistent fall in values and/or increased in variability on days at work with recovery on days away from work. However Serial peak flow measurement is only useful when the worker is still working in a job where they are exposed to the suspected agent5

Allergy test or Skin prick test – This test involves using various allergens to assess whether the worker has a reaction to the allergens used which could be linked to their occupational asthma, however, if symptoms are caused by irritants instead of allergens there will be no visible reaction on the test5

Challenge test – This test involves the worker inhaling the known or thought to be causing the symptoms, to see if any trigger asthma symptoms. This is quite a difficult test and is performed in specialist centers where the worker can be closely monitored5 .

If OA is detected early sometimes symptoms can be stopped, as long as the OA is diagnosed quickly, the cause is identified and exposure to the trigger is stopped. When symptoms will stop will vary, for some workers, it may be straight and for others take longer. Even if symptoms do go away, the substance that set them off will always be a trigger for the worker, so they will need to avoid it, this may mean avoiding similar workplaces. The best way to prevent occupational asthma is to control exposure to chemicals and other substances that the workers may be sensitive to or that are irritating. Workplaces can implement better control methods to prevent exposures, use less harmful substances and provide personal protective equipment (PPE) for workers6. Medications may help relieve symptoms and control inflammation associated with occupational asthma. As well as changes of lifestyle factors contributing to the OA can be made for example if the worker smokes they should quit as being smoke-free may help prevent or lessen symptoms of OA or if the worker is obese, losing weight can help improve symptoms and lung function. Employers must also make the effort to keep workers safe and provide the workers with relevant material such as a safety data sheet for each hazardous chemical used in the workplace and share this information with the workers.

1. Occupational asthma: an approach to diagnosis and management Susan M. Tarlo, Gary M. Liss CMAJ Apr 2003, 168 (7) 867-871;

2. Malo, J. and Chan-Yeung, M., 2001. Occupational asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 108(3), pp.317-328.

3. https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/guidance/g402.pdf

4. Asthma + Lung UK. 2022. Occupational asthma and work aggravated asthma | Asthma UK. [online] Available at: <https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/understanding-asthma/types/occupational-asthma/ #:~:text=Occupational%20asthma%20is%20caused%20by,while%20before%20you%20notice%20symptoms.> [Accessed 27 September 2022].

5. Nicholson, P., Cullinan, P. and Burge, S., 2012. Concise guidance: diagnosis, management and prevention of occupational asthma. Clinical Medicine, 12(2), pp.156-159.

6. Mayo Clinic. 2022. Occupational asthma - Symptoms and causes. [online] Available at: <https:// www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/occupational-asthma/symptoms-causes/syc-20375772> [Accessed 27 September 2022].

OH Today is delighted to be interviewing Health and Wellbeing at Work’s Event Director, Lauren Sterling. Lauren has been championing health and wellbeing since the event’s inception in 2007 and has developed the event to become the UK’s leading platform for sharing best practice and innovation for improving the health, wellbeing and culture of today’s workforce.

iOH: Where did the idea for the event first come from?

LS: We’ve been organising healthcare events for over 30 years now and back in 2007 we were starting to sense a real move towards organisations becoming more responsible for employee health and wellbeing together with a greater realisation of the impact this could have on performance and productivity. We launched the event just before the Government announced the creation of their own dedicated work stream and so were able to really pioneer a forum that celebrated best practice and dealt with key issues that would enable the health and wellbeing movement to take flight. It was so gratifying to see over 2000 occupational health, HR, healthcare and health and safety professionals attend our initial event. For some, it was the first time they had been to any live event addressing their area of work and this is really what propelled us forward

LS: Firstly, content is absolutely key to us and we have sought to develop a programme that is founded on good research, evidence and best practice. The fundamentals have always been the same, dealing with issues such as mental health, disability, musculoskeletal disorders, but as our working environments have evolved, so have our priorities. Sleep, women’s health, neurodiversity, suicide, psychological safety, resilience and an ageing workforce have all climbed up the agenda. We have seen a seismic shift towards areas that were not initially aligned with occupational health but are rapidly being recognised as intrinsically linked, including culture, diversity, climate change, sustainability, employee engagement and experience. Gone are the days of OH working independently. The new world of work demands that we work hand in

hand with HR and other professionals and we have ensured that the event really reflects this.

LS: That’s a difficult one because we have worked with over 2500 presenters since the event’s inception, but I’m a big advocate of storytelling so anyone who has had the courage to share their personal experiences with our delegates really stand out. Whilst I appreciate that evidence, theory and practice all have their role to play in educating our audience, there is nothing better than learning from the lived experience. Ian Puleston-Davies who played builder Owen Armstrong in five years of Coronation Street highlighted the challenges on and off screen of working with OCD. Olympic hockey gold medalist Helen Richardson-Walsh MBE had delegates queuing out the door when she spoke about her own mental health and how employers can create working environments that allow people with mental health conditions to thrive. And the first female RAF paramedic to serve on the front line in Afghanistan, Michelle Partington was totally inspiring discussing her journey from PTSD to representing Team GB in the Invictus Games. If the pandemic has taught us nothing else, it is the need to put the human element back into the

workplace. I think that those who have shared their personal stories over the years have reminded us of the importance of compassion, humility and resilience.

LS: There are a few. I’m a great believer in positivity and resilience and I have certainly needed these in my years of organising events. But there are definitely some relatively new kids on the block. Diversity and inclusion is intrinsically linked with health and wellbeing and whilst EDI has been on corporate agendas for a while now, its impact on emotional wellbeing and also recruitment and retention has not. People that I have interviewed such as Network Rail’s Loraine Martins OBE (now at Nichols) who have totally transformed workplace cultures to become more open, inclusive and diverse are so completely inspiring and innovative. Women’s health has risen steadily up the agenda and whilst much of this has been around menopause, it is gratifying to see more employers taking other issues such as endometriosis and IVF more seriously. Our Women’s Health programme at this year’s event was by far the most popular. And finally, whilst I wouldn’t advocate this appears on everyone’s agenda, close to my heart is dogs and wellbeing. Some

may say I’ve become slightly insane, especially if you’ve been on a zoom with me to the sound of barking dogs in the background as the amazon delivery arrives, but there is certainly something to be said for championing the impact that dogs can have in the workplace and their calming and therapeutic effects well most of the time! In fact, I confess that it was after listening to Nestle’s head of wellbeing speak at our conference about dogs in the workplace that I decided this was exactly what our office needed amid the stressful world of organising events.

LS: Although I’m sure there have been many challenges we’ve had to contend with (it’s the events industry after all!), like everyone else, it had to be the pandemic. I’m a bit of a technophobe, so the prospect of creating an online as opposed to live event was extremely daunting. Our approach was to start with a totally blank canvas and design an event that was as interactive as possible, given all the constraints. Designing and delivering a week-long conference with 80 sessions, five daily parallel programmes, 25 exhibitors and sponsors, 160 speakers, 2000+ delegates, yoga classes and an interactive workplace choir sent stress levels into overdrive! As many who have attended our events will know, we are perfectionists, so we were adamant about ironing out everything that could possibly go wrong before we went live. The only problem was we had absolutely no idea of what it was that could go wrong in this new virtual world. Just too many unknown territories. Over the many months of planning, every Monday became a ‘Manic Monday’, every piece of new technology was faced with intrepidation,

and every dilemma required creativity, new skills and a lot of thinking outside of the box. Judging from the fantastic feedback we received following the event, our efforts certainly paid off. My weekly mantra of ‘never let me do this again’ rapidly transformed into a belief that our virtual Health and Wellbeing at Work event was probably one of the most rewarding things I have done in my long career. That digging deep into the pockets of resilience, developing new skills and embracing technology have become integral in transforming how we work moving forward.

LS: There is certainly a need for change. What visitors wanted from a live event pre-Covid seems very different from what they expect now. Whether we have become used to immersing ourselves in a world behind closed doors where virtual has become the norm or our roles have become so pressurised that we are having to justify every spare minute we spend, times are changing. So we’ve taken time over the summer to really listen to what delegates want and to reflect over the past 16 years of running the event. Alongside our usual CPD conference programmes, we are adding in a dedicated Men’s Health stream, working with the Men and Boys Coalition and International Men’s Day UK. We will be addressing some really hard-hitting issues, including male suicide prevention, fatherhood, supporting male victims of domestic abuse, working with cancer and most importantly, getting men to actually open up and discuss their health and wellbeing. We are also really excited about some new feature areas that will add greater value and enable a more hands-on

experience. Our new Spotlight on Health Conditions workshop will offer a clinical perspective on several health conditions that employees contend with whilst remaining in work and how these can be best supported by employers and OH professionals. Round table sessions will enable delegates to work in small groups with leading experts to address the myriad of issues faced, including mental health, fit notes, report writing and ensuring OH

moves up the corporate agenda. There will also be the opportunity to improve skills such as spirometry, managing sleep, mindfulness and health screening. We have really valued the role that occupational health nurses and other OH professionals have played in shaping the conference, and we are delighted once again to be working with iOH to deliver this year’s event.

Health and Wellbeing at Work takes place at Birmingham’s NEC 14-15 March 2023. Registration opens on the 1st November. The Organisers are delighted to offer OH Today readers up to 15% off the delegate rate by using the discount code IOH1. Visit www.healthwellbeingwork.co.uk for further details.

The Resuscitation Council UK have produced a QR code that opens a 2 minute video explaining what to do if a person collapses. The QR code leads to a video explaining how to check a person who has collapsed and what to do. You should shout for help, assess for normal breathing, call 999 and start cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

The best chance a person has of surviving a cardiac arrest is if a bystander gets help, starts CPR and uses an advisory external defibrillator if there is one available. Everyone can do this, not just health professionals or health students, so please scan the 'CPQR' code or go to the website and learn now what to do if a person near you collapses, because there won't be time when it does.

How would you define occupational epidemiology?

At its simplest, it’s the study of the pattern and causes of occupational diseases in workers.

How did you get into Occupational Epidemiology?

After obtaining my Masters in Statistics from the University of Sheffield, I joined the British Nuclear Fuels Limited’s inhouse medical statistics unit. This was because I was mainly interested in the utilisation of statistics to answer health problems. I was initially involved in studying the health of a nuclear industry workforce before later becoming involved in environmental matters, specifically those relating to childhood leukaemia clusters around nuclear installations.

What are your research interests?

I’m interested in the effects of work on all aspects of human health, in cancer,

neurological diseases, ageing workers, and mental health. Although I still have soft spot for ionising radiation-related diseases as they are what got me into my line of work in the first place.

What are you currently working on?

As ever, I am working on a number of projects relating to work and health. In collaboration with Neil Pearce and Valentina Gallo, I am examining the effect on cognition (as an early marker of dementia) of concussions in former elite rugby players and concussions and headers in former professional footballers. I am also working on an European exposure project (measure of all the exposures of an individual in a lifetime and how those exposures relate to health) focussing on cancer, neurological diseases, and work participation. In addition, I am doing some work to support the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council to enable them to make updated recommendations about prescribed diseases for respiratory cancers and chronic obstructive lung diseases. Recently, I’ve also been involved in

projects working with Martie van Tongeren at the University of Manchester on a review of man-made mineral fibres and respiratory diseases, a review of respiratory health surveillance, establishing the feasibility of an occupational exposure control intelligence system to provide intelligence on leading indicators for work-related respiratory diseases and some COVID-19-related projects examining the role of occupation in the risk of COVID-19.