Lynn Pratt

Recently, I had a conversation with a new member of the OH community. They excitedly shared how their colleagues were encouraging them to pursue formal OH qualifications and how they were immensely enjoying OH challenges. Hearing their enthusiasm reminded me of my own journey in occupational health, starting fresh as a practice nurse for an airline without any OH qualifications and feeling very overwhelmed. Thanks to the support and inspiration from my colleagues, I pursued further education, which allowed me to advance into case management, advisory roles, and management positions across various industries. Each industry brought its own set of challenges and learning experiences, enriched by the guidance of remarkable role models.

Our career experiences can shape us profoundly, especially in the early stages. The iOH team recognises that not all OH professionals receive the necessary support to flourish. Through our role modelling network of members, we can inspire the next generation to achieve excellence in our field, wherever they are on their journey. iOH are here to support in choosing educational providers, offering small grants for short courses to alleviate financial burdens, providing educational materials, peer support and facilitating networking opportunities.

The forthcoming Health & Wellbing at Work Conference on March 11th & 12th at the NEC is a highlight in our calendar. The iOH team are busy finalising preparations for our conference presenters and our exhibition stand located at 56B where we will be showcasing what iOH has to offer and future plans. We encourage members to book their tickets and use the discount code IOH15 for extra savings.

After a busy day at the conference, why not chill out the iOH Ruth Alston Memorial Lecture and Dinner on March 11th. This year's lecture, delivered by Kevin Bampton is entitled "Occupational Health: Time for a 21st Century Upgrade?". It promises an evening of fun, networking, learning, and entertainment.

Through such initiatives, we strive to inspire all OH professionals to achieve excellence. By fostering support, and creating opportunities for growth, we can ensure that our field continues to thrive and adapt to the ever-changing demands of the workplace.

Lyndsey, passed away peacefully on 2nd January 2025, surrounded by her family. As the Founder and Director of Phoenix Occupational Health Ltd, she was a devoted advocate for Occupational Health.

Lyndsey had a distinguished career, starting as a Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nurse in the Royal Navy before transitioning to occupational health. Her contributions to the field were significant, and she was recognised for her dedication and leadership. Her leadership included involvement with iOH as a former iOH Board Member between 2014 and 2016. She was actively involved in various special projects and developing relationships with sponsors. Her efforts helped enhance our resources and support for occupational health professionals.

Lyndsey was also recognised for her outstanding contributions to the field, receiving a special mention and SOM Lifetime Achievement Award in 2024. Her dedication and leadership within iOH, FOHN and the broader occupational health community left a lasting impact.

She will be greatly missed. Our thoughts are with her family at this difficult time. If anyone would like to make a charitable donation on behalf of Lyndsey, this can be made online: www.windsmillscharity.org.uk Acute bereavement support for children and young people.

By Charlene Mhangami, V-core Senior Product Specialist, Vitalograph

The flow-volume loop is a graphical plot that provides airflow. The graph is created during a spirometry expiratory volumes. These measurements are of air that can be exhaled from the lungs from full inhalation. interpretation.

Traditionally, spirometry focused on measuring exhalation in lung function testing, with the focus being on enhancing Standardization of Spirometry. The current ATS/ERS inspiratory and expiratory measurements during spirometry

provides key insights into lung function by showing the relationship between lung volume and spirometry test, capturing information during inhalation and exhalation to calculate inspiratory and are formed during the Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) manoeuver which measures the maximum volume inhalation. The FVC alongside the Vital Capacity (VC) manoeuvres are crucial in spirometry

exhalation only, with the test ending when the subject has fully exhaled as shown in figure 1. Advances enhancing the precision and accuracy of spirometry results led to an update ATS/ERS 2005

ATS/ERS 2019 Standardization of Spirometry standards, emphasise the importance of incorporating both spirometry testing to create the flow-volume loop.

Figure 1. Flow-volume loop with expiration only.

Historically, some spirometers and spirometry software only measured expiration, as well as the use of one-way valve mouth pieces. As a result, many departments routinely performed exhalation-only manoeuvres. However, new insights discussed within this article suggest that measuring inspiratory flow alongside expiration can improve test quality.

The 2005 ATS/ERS spirometry standardization outlined three main steps to obtain an FVC. Firstly, maximal inspiration, followed by a strong exhalation (blast), and finally, complete exhalation. A separate test sequence was discussed briefly for inspiration, referred to as the “Maximal Expiratory Flow Volume Loop” MFVL. In this test sequence, the subject is asked to take a rapid full inspiration to total lung capacity (TLC) from room air through the mouth, insert the mouthpiece and, without hesitation, perform an expiration with maximum force until no more gas can be expelled, followed by a quick maximum inspiration. At this point, the manoeuvre is finished, completing the loop in a single manoeuvre.

By contrast, the 2019 guidelines prioritise both inspiration and expiration within a single FVC manoeuvre. This is broken into four steps:

1. Maximal inspiration

2. A forceful exhalation

3. Complete exhalation and

4. An inspiratory manoeuvre back to total lung capacity (TLC).

This revised approach places greater importance on inspiration, as the 2019 ATS/ERS guidelines mention the parameter forced inspiratory vital capacity (FIVC), which is measured at end expiration with inhalation back to TLC. The guidelines state comparing the FVC and FIVC is key for assessing the technical acceptability of spirometry results. Only when both inspiratory and expiratory manoeuvres are performed can this comparison be made, ensuring accurate testing.

Figure 2. A well-formed flow-volume loop reflects healthy lung function. The curve shows the relationship between airflow (vertical axis) and lung volume (horizontal axis). For a normal result, the curve begins at TLC and features a peak during forceful exhalation, which gradually diminishes as lung volume decreases. The loop then curves upwards as the patient inhales back to TLC. The highest flow rate occurs at the beginning of exhalation and is effort dependent. After approximately one-third of the exhale, airflow becomes less effort-dependent and more influenced by lung pressure and airway resistance.

Figure 2.

Flow-volume loop in a healthy subject with expiration and inspiratory volumes.

The shape of the flow-volume loop can also reveal patterns of lung disease. For example, in obstructive lung diseases like asthma or COPD, there is a reduction in maximal expiratory flow which causes the characteristic “scooping” or concave shape in the loop. This occurs because the airway collapses during forceful exhalation, reducing the airflow despite maximum effort. The severity of obstruction can be assessed by depth of the scoop as shown in figure 3 and 4.

Figure 3

Flow-volume loop with mild airflow obstruction.

Figure 4

Flow-volume loop with severe airflow obstruction.

Lung diseases that restrict lung expansion such as chest wall abnormalities or space-occupying lesions such as tumors can lead to restrictive lung disease. In these cases, the flow-volume loop will show reduced lung volumes and shorter exhalation times as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Flow-volume loop with a mild restrictive defect.

Figure 6

Flow-volume loop with a severe restrictive defect.

One of the key advantages of measuring inspiration during spirometry is the ability to capture the FIVC. Without the inspiratory maneuver FIVC cannot be obtained. FIVC can be compared with FVC to assess whether the test began at TLC. According to ATS/ERS guidelines, if the FIVC exceeds the FVC by more than 0.100 L or 5% of the FVC, it indicates that the test did not start from TLC, making the result unreliable for certain measurements such as FEV1. However, the FVC may still be acceptable. Most modern spirometers have the FIVC parameter within the parameter list and some software can offer real-time feedback on this comparison, helping operators ensure the test is conducted correctly. The comparison of FIVC and FVC can also be observed on the flow-volume loop if FIVC is obtained is bigger than FVC as shown in Figure 7.

Flow-volume loop showing initial suboptimal inhalation before exhalation, confirmed by the second inhalation back to TLC.

Spirometry: Performance and Interpretation A Guide for General Practitioners. (2005). Available at: https://irishthoracicsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SpirometryGuidelinespdf.pdf

Spirometry: Performance and Interpretation A Guide for General Practitioners. (2005). Available at: https://irishthoracicsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SpirometryGuidelinespdf.pdf

Graham, B.L., Steenbruggen, I., Miller, M.R., Barjaktarevic, I.Z., Cooper, B.G., Hall, G.L., Hallstrand, T.S., Kaminsky, D.A., McCarthy, K., McCormack, M.C., Oropez, C.E., Rosenfeld, M., Stanojevic, S., Swanney, M.P. and Thompson, B.R. (2019b). Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, [online] 200(8), pp.e70 e88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/ rccm.201908

Vitalograph Spirotrac 6 software.

By Jane Manders

Introduction

The term empowerment when used in a healthcare setting usually refers to how staff can empower their patients. This can be seen as upskilling them on their diagnosis, so that treatment goals can be defined and allow them to take responsibility (Varekamp et al., 2009). In the occupational health (OH) setting Ekeberg et al. (1997) defines empowerment as a process whereby the OH nurse helps a person to take control over issues that affect their lives. This viewpoint is held similarly by Puetz (1988) whereby sharing power with others enables them to achieve their goals. However, this article is focused on empowerment from a quality management perspective with reference to my own research study in 2023.

The role and benefits of employee empowerment

Employee engagement is about an employee's emotional commitment and motivation towards their work and organisation, driven by leadership support and a positive culture. Employee empowerment involves giving employees the autonomy, resources, and authority to make decisions and take ownership of their work, enabling them to act independently and contribute to success.

Employee empowerment is crucial for quality management. By giving employees ownership, listening to their ideas, and implementing them, creativity and innovation increase, boosting organisational performance (Goetsch & Davis, 2016). Empowered employees care about their work, leading to continuous improvement and as Hemag et al. (2022) highlight that empowered employees are vital to organisational success.

In healthcare settings research has shown that implementing quality programmes alone is not enough. To truly enhance clinical care, it is essential to empower employees alongside these initiatives.

In Maynard et al.’s (2012) literature review, they cited several sources when defining employee empowerment with two elements identified, namely structural and psychological

empowerment. Structural empowerment focuses on organisational conditions such as:

Access to information: Employees need relevant knowledge to perform effectively.

Support: Guidance and feedback from leaders enhance confidence and decision -making.

Resources and tools: Availability of necessary materials and technology.

Opportunities for growth: Training, career development, and participation in decision-making.

Psychological empowerment focuses on the individual, their perception of controlling work and their motivational processes. It also includes:

Meaning: Employees see their work as valuable and aligned with personal and organisational goals.

Competence: Confidence in their skills and abilities to perform well.

Autonomy: Freedom to make decisions and solve problems independently.

Impact: Belief that their contributions make a difference in the organisation.

Employee empowerment impacts workplace mental health positively. Laschinger and Havens (1997) found that nurses' perception of structural empowerment improved their mental health and effectiveness. Laschinger et al. (2013) linked reduced burnout to authentic nurse leaders, highlighting balanced processing and self-awareness as key factors. Their study showed similar outcomes for both recent graduates and experienced nurses. Senior leaders should note that selfaware leaders who practice balanced processing enhance structural

empowerment, regardless of employees' experience levels.

Chandler created the Conditions for Workplace Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ) in 1986, based on Kanter's employee empowerment theory. It was later improved to CWEQ II , recognised as reliable and valid. CWEQ II has six subscales: Opportunity, Information, Support, Resources, Formal Power, and Informal Power (Western University Canada, 2023).

The CWEQII was distributed within the OH sector, yielding 92 anonymous responses. No personal data was collected. The results showed that total structural empowerment scores range from 6 to 30; scores of 6-13 represent low empowerment, 14-22 moderate, and 23-30 high.

Figure 1 displays the total structural empowerment by profession. Operations roles had high structural empowerment, while nurses, doctors, and technicians had moderate levels.

The CWEQII uses a global measure of empowerment as a validation index. The global empowerment score was 3.53, indicating a moderate level.

OH nurses were the largest group of respondents, with 70 completing the survey. Additional input from other professions will be necessary for more comprehensive results in the future. Figure 2 provides an overview of the number of respondents by sector.

Figure 3 shows the scores for each empowerment subscale, ranging from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate better access.

OH nurses had moderate scores across all subscales. The highest score was in Opportunity, indicating career development and innovation in problem-solving, while the lowest was in Support, indicating a lack of constructive feedback from managers and colleagues, which may affect their empowerment.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) states that effective nursing practice requires providing and seeking feedback from colleagues and stakeholders. Feedback is crucial for professional development, helping nurses to reflect and improve. In this survey, 36.9% of respondents said they rarely or never received specific improvement comments, while 41% indicated receiving them sometimes.

Demographics on the work sector were also captured (figure 4). It was found that individuals working in the public sector had the lowest total structural empowerment score. In contrast, self-employed individuals or business owners had the highest empowerment scores.

Total empowerment score by sector

This research identified barriers to workplace empowerment, including employee readiness, contextual setting, and resistance by various groups (Goetsch & Davis, 2016). Line managers are essential for effective empowerment, with coaching and training needed to upskill all management levels. They also play a critical role in providing employees with the necessary information to perform effectively.

This research survey relied on self-reporting by individuals, and their responses may be influenced by their daily mood. The cross-sectional design of the survey is another limitation; a longitudinal design could address this issue. The voluntary nature of participation introduces selection bias, which may limit the ability to generalise the findings to the entire OH population. Consequently, it should not be assumed that the views of non-respondents are the same as those who participated.

There are several benefits to employee empowerment including improved productivity, performance, job satisfaction, and innovation, all leading to successful organisations. In healthcare settings, similar benefits are noted, such as improved nurse performance, better clinical care, compliance to standards and job satisfaction. Better mental health, including lower burnout, is also a benefit. Line managers play a key role in employee empowerment.

This research focuses on OH nurses, but future studies should include other roles in the sector, such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists, to get a comprehensive view.

There is a decline in OH expertise (Tindle et al, 2020) and given the government's recognition of their value and importance, if OH practitioners are dissatisfied and perform poorly due to lack of empowerment, the future of this workforce could be harmed. Targeted programs must be improved by senior leaders and management.

Jane Manders, MSc,

Jane is an Occupational Health Business Partner at Mitie. This article was based on Jane’s research for an MSc in Strategic Quality Management in 2023. Jane also holds a BA in Occupational Health Practice.

The 2025 EOPH conference took place in Birmingham on 14th February. Themed ’Putting Health back into Health Surveillance’ it saw over 80 delegates, speakers and exhibitors come together for a day of talks, networking and learning. Speakers covered different aspects of how occupational health professionals prevent ill health and injury through effective health surveillance in the workplace.

It was an informative and valuable day, enabling those who attended to think more broadly than the processes and towards the outcomes that all of us working in occupational health want to achieve.

For those who couldn’t attend, we’ve summarised the takeaways from each talk, along with any resources mentioned. We hope you’ll find this helpful.

Want to know more about EOPH and our courses?

Wherever you are in your career, we can support the next stage in your professional development. Visit our site for the latest training for occupational health professionals, our free knowledge hub and much more: https:// eoph.co.uk/

The EOPH Conference will be back in 2026! Dates and programme to be announced later this year.

Dr Robin Cordell covered how the 2023 SEQOHS standards enable occupational health services to demonstrate how they identify occupational health needs for their client organisations. He also discussed how they ensure quality of processes and the competence of those undertaking health surveillance as required by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

Dr Cordell’s message was that standards are important as they give assurance that we, as OH professionals, are doing things right. And that we are also striving for better, i.e. assuring that services are ‘good enough’ and then moving from ‘good’ to ‘great’. It’s a combination of assurance, continuous quality improvement and demonstrating value.

He referred to the latest version of the SEQOHS quality standards and their emphasis on outputs and outcomes. Providers can now demonstrate with clarity the breadth of value they bring to commissioners/purchasers of services, to their employees, and to themselves through benchmarking. Find out more about the latest standards at: https://www.seqohs.org/CMS/Page.aspx?PageId=77

Dr Robin Cordell is in clinical practice as an accredited specialist in occupational medicine and is the current President of the Faculty of Occupational Health.

Dr Steve Forman started his session by stating that while the UK is one of the best countries in terms of workplace safety, we still saw 138 workers killed in work-related accidents in 2023/24 - and that’s 138 too many. What’s more, that 1.7 million people are suffering from workrelated ill health. - either new or long standing. Therefore, health surveillance and the early identification of work ill health to manage risk is of strategic importance to a fit and healthy workplace.

Dr Forman covered the regulations that require health surveillance which include the control of hazardous substances, hand-arm vibration and noise as well as those requiring an appointed doctor which include managing and working with asbestos, control of lead at work and working with ionising radiation. Guidance on all regulations are available from the HSE here: https://www.hse.gov.uk/

On a cautionary note, health surveillance can go wrong when not performed by the employer or when performed inadequately by an OH provider which may be due to poor testing or failure to recognise abnormal results amongst other issues. Poor communication between the OH provider and the employer, or the employer not acting on results are additional risks.

In summary, Dr Forman’s talk concluded that health surveillance allows early identification of work-related ill health so employers can manage risk (both at individual and group levels), it’s part of a system of health risk management an important process that needs to be performed correctly.

Dr Steve Forman leads the OH team in the Health and Work branch of the HSE.

Using a practical and entertaining example, based on handling goods in a ‘bath bomb’ shop, Dr Katrin Alden covered the hazards and conditions causing hand eczema relevant to skin surveillance. As she explained, skin is affected on a common basis and skin surveillance is relevant as a strategy or method to detect and assess the adverse effects of work, or workplace exposures, on the skin health of workers.

Her example of ingredients affecting skin helped demonstrate what happens when an employer fails on the minimum legal requirement that they must do under the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 - i.e. to identify hazards, determine the level and severity of risks and take action to eliminate the hazard, or if not possible, to control those risks.

During her talk, Dr Alden also covered visual skin assessments and skin management using emollients and steroids. She also referred delegates to her work with SOM on the publication ‘Managing Skin Health at Work’. Available here: https://www.som.org.uk/managing-skinhealth-work-new-som-guidance

Dr Alden is an occupational health physician and speciality doctor in dermatology with an interest in work-related skin problems and lead clinician for the skin surveillance programme of a large NHS Trust.

Using case studies, Professor Jo Szram outlined the common contemporary issues in occupational lung disease, focusing on the conditions and presentations that a modern day occupational health practitioner is likely to encounter.

She remarked that we are increasingly seeing cases of hypersensitivity and silicosis, with the dangers of inhalation of crystalline silica dust found in the artificial stone used in the manufacture of kitchen worktops being in the news. Discussing workplace asthma, Professor Szram shared that of the 4 million people in the UK receiving treatment for asthma, around 10% of this number is attributable to workplace conditions.

Her take home messages were that respiratory symptoms can be caused or worsened by occupational exposure, so awareness of specific workplace exposures is useful. Taking a complete occupational history and establishing the respiratory pathology are also key. Visit www.lungsatwork.org.uk for more information and resources.

Professor Szram is a consultant in occupational lung disease and asthma based at Royal Brompton Hospital.

Dr Dan Ashdown and Dr CJ Grobler jointly covered an update on guidance for diagnosis and management of disorders related to hand-held vibrating tools, prevention of HAVS and best practice for health surveillance for HAVS.

Dr Ashdown started with an overview of HAVS, being caused by prolonged exposure to hand-transmitted vibration (HTV) which is associated with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Dupuytren's Disease. It primarily affects the blood vessels, nerves, and joints of the hand, wrist, and arm and is often associated with the use of vibrating tools in occupations such as extraction, construction and manufacturing.

Dr Ashdown mentioned the HAVS resources available from the SOM Special Interest Group, including a Delphi Study available here: https://www.som.org.uk/sites/ som.org.uk/files/ SOM_HAVS_SIG_Delphi_Study_Jan24.pdf

Dr Grobler gave an update on health surveillance policy for HAVS and prevention of HAVS. Using the hierarchy of control measures model, Dr Grobler shared advice for employers with elimination of risk being most effective using examples of automation and remote controlled equipment. He also shared a continuous prevention model focused on health surveillance policies of Plan, Do, Check and Act.

Both Dr Ashdown and Dr Grobler are members of the UK Society of Occupational Medicine’s HAVS Special Interest Group and have published research on HAVS.

Dr Finola Ryan explored the best practices in occupational hearing health surveillance. She explained how occupational health professionals can support employers in identifying noise hazards, managing exposure levels using reliable monitoring systems and recognising vulnerable worker groups.

Some of these hazards come from low frequency noise from ventilation and heavy machinery, mid-frequency noise from typical industrial processes, high-frequency noise from compressed air and metal work and impact noise which can span multiple frequencies. Understanding these different sources helps us interpret our noise surveys more effectively. But there are a number of approaches to noise measurement, each giving different but complementary information. Dr Ryan demonstrated that measurements may tell us one thing, but health surveillance can tell us another - which is why we need to think carefully when interpreting our tests.

Her take home messages included realising there are challenges of using diagnostic tools for surveillance with different populations with different needs. We are trying to look for pre-clinical changes and there is a need for early interventions. Some of the realities include no consensus on surveillance criteria and that threshold shifts mean that damage has already been done. Moving forward, she advised considering pattern recognition, looking at multiple frequencies, the value of early indicators and using trend analysis.

Dr Ryan is a Consultant Occupational Health Physician with a special interest in Performing Arts Medicine. She is also an Honorary lecturer at University College London.

This guide describes simple steps to writing a meaningful policy relating to your organisational context.

Classifications helps to identify the different dimensions and purposes of policies within organisations and governments.

➢ Public/Government policies:

- Substantive (societal) policies

- Regulatory policies are formulated to impose controls and restrictions on specific activities or behaviours.

- Distributive policies enable the government to provide useful goods and services to most citizens, paid for by the taxpayers

- Redistributive policies reallocate wealth, property, political or civil rights, or something else of value for the benefit of class-based groups

➢ Organisation: These are overarching written policies that guide the overall goals and direction of an organisation.

➢ Specific e.g. Insurance: Detailed policies formulated for particular issues or scenarios.

➢ Functional (Departmental): These are specific to different organisation functions, such as HR, finance, or marketing.

It is very easy to dive straight into improving processes and conducting assurance activities. However, take a step back and look at the strategy you will take to achieve the ultimate outcome. What is your content? What goals are you trying to achieve? Here is where having a clear policy in place helps and involving all relevant stakeholders in policy writing is likely to bring you an increased collaboration and effectiveness in your policy.

The best way to structure writing a policy is to take your reader through the learning funnel process. Starting from the wider remit narrowing it down to the relevant detail.

It is a journey, which is best illustrated when organisations are talking about ways to create effective learning materials for their staff.

By Victoria Tait and Hilary Winch

Taken from Superb Learning: The Learning Funnel, (2024)

Writing your policy. What are the main points you wish to communicate?

Use the 10 pillars approach. Ask your business questions about each of the 10 areas and your policy is formed.

10 Pillars for writing a policy

1. Policy Scope

2. Policy Objective

3. Governance 4. Definitions

5. Responsibilities

6. High-level implementation guidelines

7. Communication guidelines

8. Qualifications and Training where relevant

9. Reviewing and Monitoring

10.Administration and approval

The scope of a policy defines the boundaries and applicability of the policy. It outlines who and what the policy applies to, whether it is limited to certain departments, locations, or specific situations. It should come at the start. There is no point in someone reading about this policy if it does not apply to them or their job role. Clearly defining the scope helps prevent confusion and ensures consistent application of the policy throughout the organisation. It should also be clear as to who or what this policy will not cover. There has to be a clear synergy between the policy scope and objective.

This policy applies to all employees of {insert organisation name}, including contractors and casual staff.

The objective of a policy is to clearly state the purpose and goals that the policy aims to achieve. It provides a concise explanation of why the policy exists and what it intends to accomplish. This helps ensure that everyone understands the policy’s importance and aligns their actions with its intended outcomes. This is the first touch point on whether the policy is aligned with the overall business strategy. Try to include no more than 3 key points.

a. Health and Safety Policy:

Objective: To ensure a safe and healthy working environment for all employees by identifying and mitigating potential hazards, promoting health and safety awareness, and complying with relevant legislation.

b. Data Privacy Policy:

To protect the personal data of customers and employees by implementing robust general data protection regulation measures, ensuring compliance with UK data privacy laws, and fostering a culture of privacy within the organisation.

c. Equal Employment Opportunity Policy:

To promote a diverse and inclusive workplace by ensuring fair treatment in hiring, promotion, and other employment practices, and by preventing discrimination based on race, gender, age, disability, or other protected characteristics.

d. IT Security Policy:

To safeguard the organisation’s information systems and data from unauthorized access, breaches, and other security threats by implementing comprehensive security measures and promoting cybersecurity awareness among employees.

What are the legislations, regulations and standards you need to meet? These are interconnected but serve different purposes. Ask, what the risks and or consequences of non-compliance with each are. Also include any details about Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in line with the Equality Act 2015 and Equality

Acronyms and terminology may be specific to your organisation, another organisation or society. It is therefore good to document which definition you have chosen to align with.

Legislation refers to laws that have been enacted by a governing body, such as a parliament. These laws are legally binding and must be followed by individuals and organisations within the jurisdiction.

Example

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 in the UK.

Regulations are detailed rules or directives made by an authority to implement and enforce legislation. They provide specific instructions on how the laws will be applied and enforced.

Example

The UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a regulation that works alongside the Data Protection Act 2018 and privacy for individuals in the UK.

Standards are established norms or criteria that provide a basis for consistent and quality practices. They can be national or international and are often used to ensure safety, reliability, and efficiency.

Example

ISO 9001 is an international standard for quality management systems. SEQOHS is a standard for Safe Effective Quality Occupational Health Services

Mental health: Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to her or his community.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental wellbeing as a state in which an individual realises their abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, and can contribute to their community.

Think about your organisation's structure. Be specific about who does what.

Include the company responsibilities, directors, managers, employees and anyone else who has a responsibility to uphold the directives in this policy.

This is when you tell your reader how you will implement this policy.

However, a policy is not a procedure. Procedures deal with the step-by-step details of “how” to follow the policy.

Policy

Organisation ‘rules’, ‘standards’, ‘principles’, ‘guidelines’ to follow

Explain why exist, when to apply and who it covers

Ensure individuals aware of their responsibilities/ consequences

Ensure safe / best and consistent practice is understood by the organisation

Link between organisational values, strategy and policy content

Procedure

Step by step – how to follow the rules

Practical details. Must be tangible, precise, exact, specific, factual, auditable

Links to forms to complete

Visuals are often easier to understand, e.g. flowcharts, lists, screenshots, photographs

Aim: To create a supportive workplace culture, tackle factors that may harm mental health, and ensure managers have the right skills to support staff

Policy actions:

• Give employees information on mental health issues to help raise awareness

• Deliver non-judgemental support to any staff member experiencing a mental health issue

• Consider mental health first aid training for teams, or ensure the business has mental health first aiders who can support staff with mental ill health

• Give all staff access to the mental health policy

• Deliver a thorough induction for all new starters, providing an outline of the organisation, the policies and the role they are expected to play

This is the meatiest section in your policy. The third layer in the learning funnel as shared above.

An action must accompany each objective. When you map your thought process of what is achievable, you can then tidy up your objectives section accordingly. Choose policy actions that suit your workplace and make them SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-specific). High-level steps, stages, or gateways that are recognisable within the evidence or process, and in use anywhere the scope is covered, must be evident.

If you are implementing a specific policy i.e. not a business-wide company policy, follow the same approach but narrow the funnel down further.

• Provide ways for staff to support their own mental wellbeing, for example through stress-buster activities, lunchtime activities and social events

• Offer employees flexible working hours

• Set realistic targets and deadlines for staff to prevent long working hours

• Deal with any conflict quickly and make sure the workplace is free from bullying, harassment, racism or discrimination

• Ensure all staff have clear job descriptions, objectives and responsibilities, as well as the training to do their job well

• Ensure good communication between managers, staff and teams

If you have timeframes associated with some of the implementations, then surface them, especially if they are key to the outcome delivered. Here is a diagram that illustrates all these pillars.

If your policy does not have any information to communicate with stakeholders, you have an ill-fitting policy. You need to go back to the drawing board. Remember, a solid governance framework operates in line with an organisation's context. This context has to be at the front of your policy’s output and outcome.

What will I communicate, with who, and when do they need this information by?

If you answer the question above and consider all your stakeholders, you have got your section populated.

1. All employees will be made aware of the {insert policy name} policy and the resources that are available to them.

2. The {insert policy name} policy will be included in the employee handbook.

3. Employees receive a copy of this policy during the induction process

4. This policy is easily accessible by all members of the organisation will be available to download from the staff intranet or shared drives and servers.

5. Employees are informed when a particular activity aligns with this policy

6. Employees are empowered to actively contribute and provide feedback to this policy

7. Employees are notified of all changes to this policy.

This section is an optional one, used only where applicable and commonly seen in policies that are skill-specific. For example, a policy on audit will include a section that explains who is authorised to conduct the work and what training or qualifications they require.

Put yourself in the reader's shoes. Is it communicating what it needs to? Is it easily understood? Get a peer to review it. Involve people in the development process, get ideas and feedback and the workplace talking about the policy details. The commitment and participation of your employees is essential to creating a supportive, responsive and productive working environment that benefits everyone. Regular reviews and monitoring are important for checking the effectiveness.

The document should contain a document title, a unique document identifier, version number, Issue Date, Review Date, Author and Review/Approved with names and job titles (and e-signature). ISO has guidance on creating and updating policies: ISO-ts-9002-2016

Author Mickey Mouse

Reviewed and approved by Minnie Mouse

Your policy should now be at a stage to be reviewed for final sign-off. Once you have finalised your policy and it has been approved by senior management, ensure a communication strategy is in place, circulate the approved policy to all current employees, provide any training required on the policy and incorporate the policy into any new employee induction processes. Ensure any procedural documents or tool kits associated with the policy are ready to launch as well.

In conclusion, remember, a policy is a position statement and the “who”, the “what” and the “why” needs to be clear. A clear decision starts a good policy. Remember the reader, meet their needs and enhance understanding, keep it short and without jargon. Be transparent in communicating and ensure clarity i.e. Write in an active voice vs a passive, e.g. all employees must adhere to these steps. And last of all remember, a policy is not a procedure.

Victoria Tait, CQP FCQI is a Chartered Quality Professional and a Fellow of the Chartered Quality Institute working as a Quality Assurance Specialist in the field of Occupational Health (QualitaitTM)

Hilary is the past Chair of NHS Health at Work Network. Associate Director- Workplace Health, Safety & Wellbeing, Norfolk & Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

By Michelle Moorst

As an occupational health specialist nurse, I was looking to find a course to further enhance my skills in health, safety and the environment. My preference for a flexible, self-paced learning approach led me to research various providers before enrolling in The National Examination Board in Occupational Safety and Health (NEBOSH) Certificate. NEBOSH stands as a global leader in providing health, safety, and environmental qualifications.

Among their respected offerings, the NEBOSH National General Certificate in Occupational Health and Safety delivers practical insights for effectively managing workplace health and safety. This comprehensive course covers critical areas such as risk assessment, recognising common workplace hazards, implementing control measures, and ensuring legal compliance.

The NEBOSH qualification journey can be both challenging and immensely rewarding. I

embarked on this path in October 2024, opting for a full self-study online course. The chosen platform was intuitive and well-structured, making it easy to navigate through the course materials. The resources provided were clear and concise, featuring video tutorials, interactive exercises, and practice assessments that reinforced key concepts. The advantage of studying at my own pace was particularly beneficial. I scheduled my examinations through the provider, with the examination dates available on the NEBOSH website. The exams comprised two parts: an open-book written examination and a risk assessment submission. Additionally, the provider offered webinars to support exam preparation closer to the exam dates. While the course materials on the platform were thorough, I supplemented them with an extra textbook from NEBOSH to deepen my understanding of the subject matter.

The course has significantly enhanced my role as an occupational health advisor. It has equipped me to better identify and address workplace hazards, ensuring compliance and reducing risks. Moreover, the qualification has improved my ability to manage cases, provide advice on work-related health issues, and educate others on health and safety practices, all of which contribute to creating a safer work environment.

I highly recommend the NEBOSH qualification, particularly through an online platform provider if you value the flexibility of studying at your own pace. Overall, it is a practical and worthwhile course that has equipped me with invaluable skills for my daily work. If you are considering a similar path, my advice is to go for it make sure to choose the right course provider, gather the necessary resources, and develop a solid plan to maximize your selfstudy experience.

Michelle is an Occupational Health Specialist Nurse.

iOH offers small educational grants to iOH members subject to criteria. Log onto the members area for more information on applying for an iOH Educational Grant

The ageing population of Occupational Health Advisors (OHAs) and a historical lack of investment in their training have led to a skills shortage and wage inflation in the sector (DWP, 2021). To address this, many Occupational Health (OH) organisations have developed in-house training programs. For these programs to be effective, it is crucial to clearly define roles and responsibilities within the organisation through a Learning and Development (L&D) responsibility matrix.

A responsibility matrix outlines roles to ensure that L&D are optimised. Effective L&D programs help develop the skills and knowledge necessary for delivering highquality OH services, thereby contributing to the organisation's success. Good quality L&D inspires employees to perform at their best, enhancing their contributions to organisational goals. In times of talent scarcity, developing existing employees is more costeffective (Organization Development: A Practitioner's Guide). To ensure success, learning responsibilities must be clearly allocated among the employer, employee, and the L&D department.

(Source: Adapted from Nick van Dam, 25 Best Practices in Learning & Talent Development, 2nd edition, Lulu Press, 2008)

Seek and reflect on feedback.

Assess personal skills and knowledge to identify areas for improvement.

Actively pursue opportunities to address skill and knowledge gaps.

Apply new knowledge in practice.

Share learning and insights with the team to foster continuous improvement.

Role model a learning culture by actively engaging in their own learning and development.

Set clear expectations and goals for their team. Including defining job responsibilities, performance targets, and the skills and behaviours needed to achieve them.

Provide constructive feedback and coaching to foster both individual and team growth. Contribute to the team’s understanding of how they contribute to the organisation’s goals.

Through regular performance reviews and 1-1s actively support development by identifying skills gaps and facilitating personalised learning opportunities. This includes arranging observation sessions, mentoring and competency checking, with formal training.

Integrate learning into daily work activities by encouraging problemsolving and sharing of best practices.

Observe and document behaviour change following training to feedback to the L&D department. This data is essential to assess learning transfer and identify areas for improvement.

Plan and review induction programmes to help new employees integrate

smoothly into their new roles.

Collaborate with the L & D department and Clinical Governance (CG) when onboarding new services to identify and plan how L&D needs will be met.

Conducting a learning needs analysis (LNA) with the L&D department when gaps are identified ensures the learning environment, processes and procedures are considered when

Collaborate with operations and CG when onboarding new clients or services to identify and plan training needs.

Conduct an LNA to determine skills and knowledge gaps.

Differentiate between learning, process, and environmental needs to design appropriate training solutions.

Set clear learning objectives and use evidence-based practices to develop training programs.

Deliver training through various methods, including remote, in-person, e -learning, and blended approaches. Conduct learning transfer analysis posttraining to assess the effectiveness of learning outcomes.

Report on L&D functions to senior management to ensure alignment with organisational goals.

Recognise that the quality of service is determined primarily through clinician efforts.

Emphasise core values and behaviours during regular appraisals.

Facilitate access to training and development through in-house and external training.

Support apprenticeships where feasible.

Consider financial support for higher education or professional qualifications.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the roles and responsibilities necessary for an effective L&D strategy within an organisation. By clearly defining these roles, OH organisations can ensure that their L&D programs are successful and contribute to overall business goals.

Not all organisations have separate L&D, CG and operational departments; however, this can be a good guide to map within organisations.

This article was provided by PAM Academy, the L&D department of PAM Group.

By Claire Glynn

Introduction

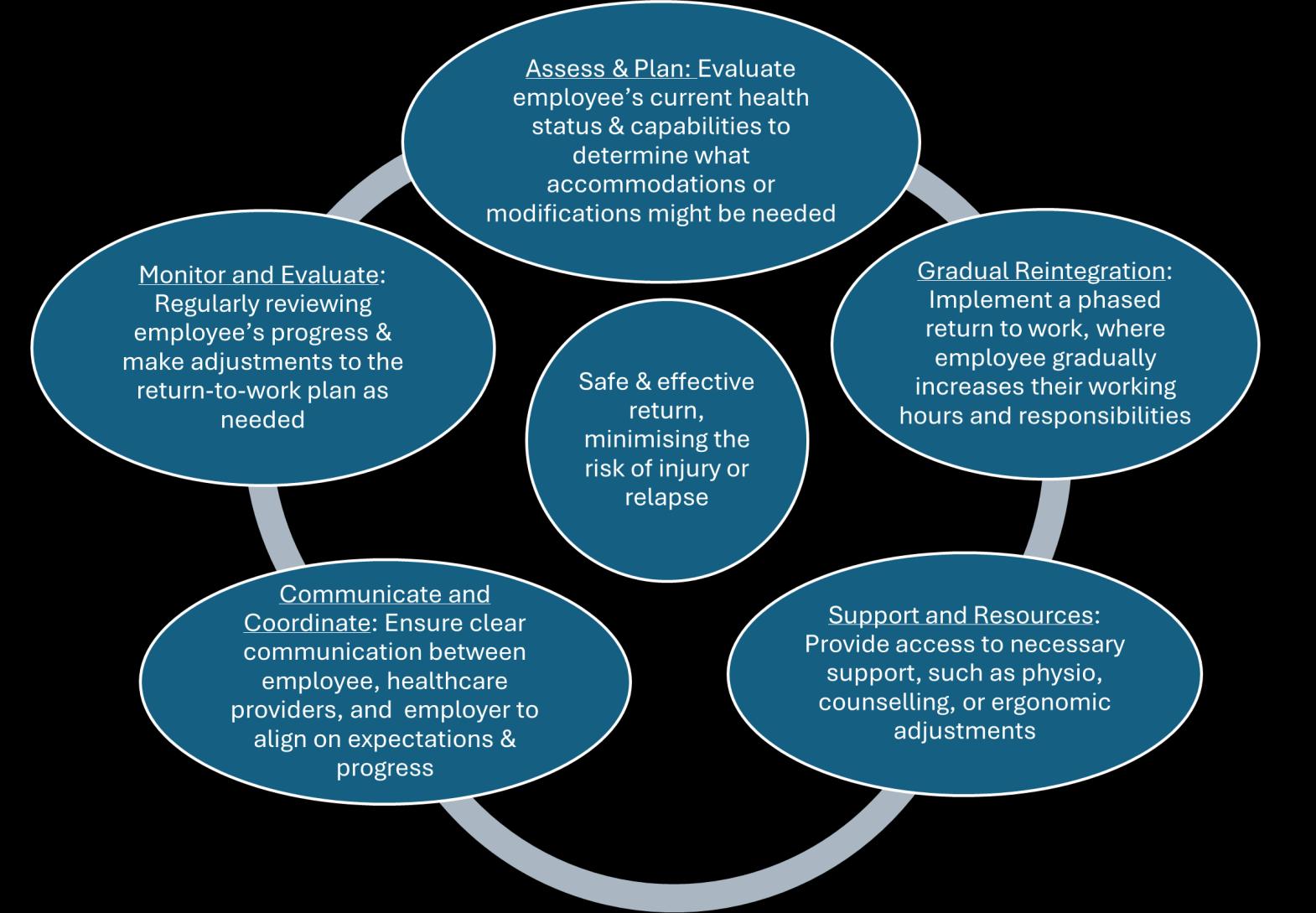

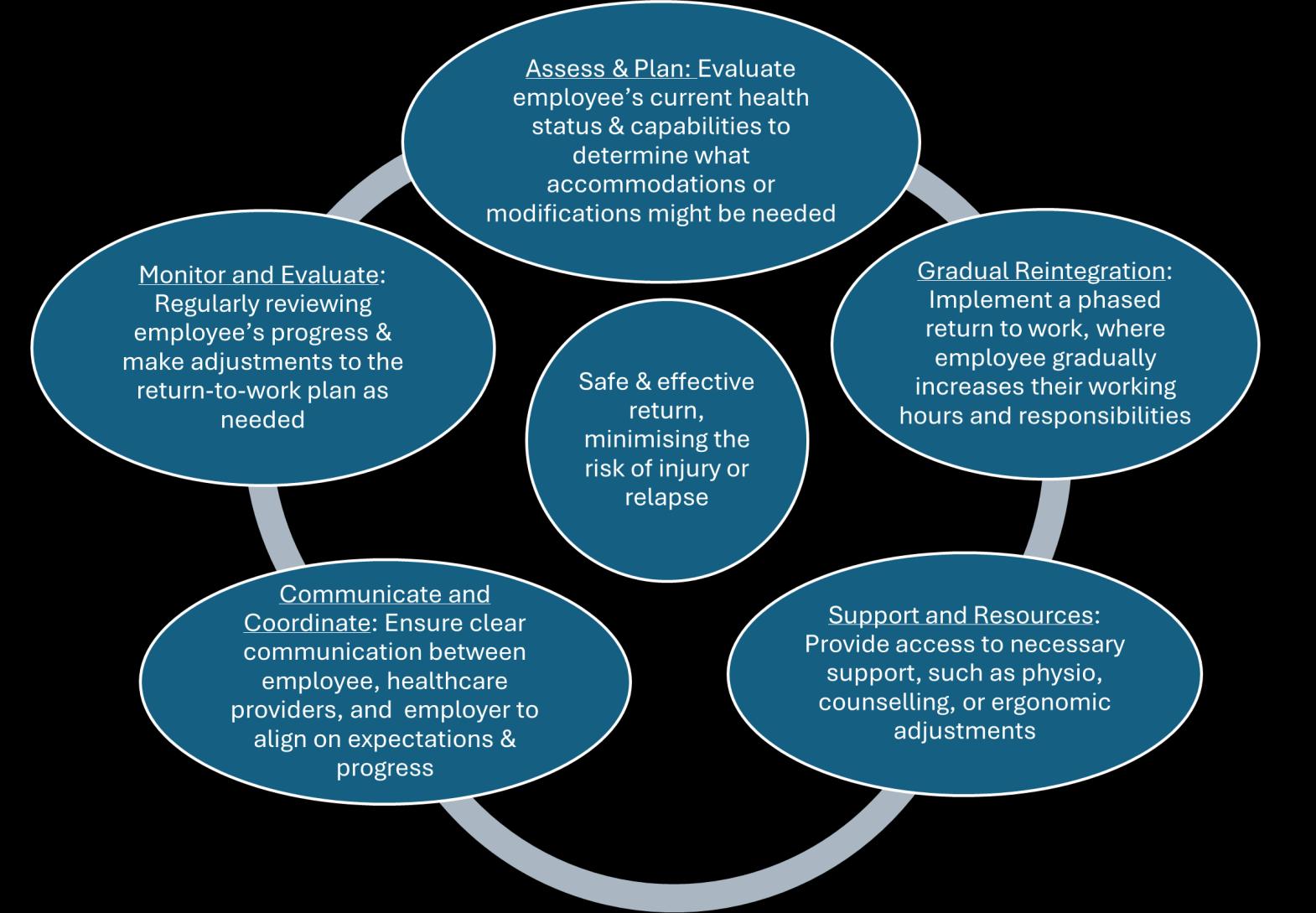

Returning to work (RTW) after a prolonged absence due to illness or injury can be challenging.

Rehabilitation and work hardening programmes are essential to ensure a safe and effective reintegration into the workplace. This article guides the consideration and implementation of measures or processes, emphasising the importance of individualised plans and the role of biopsychosocial factors.

Return to work is defined as the process of helping employees transition back to their job role(s) after an absence due to illness, injury, or other reasons (Office for Equality and Opportunity (OEO), 2023).

Measures can be considered in all circumstances, not only returning following sickness absence, but after career breaks or maternity leave, for example.

Work hardening is a specific rehabilitation programme tailored to the needs of both the employee and the job, assisting individuals in returning to work after an illness or injury, or other absence. Interventions are carefully planned and have clear goals to ensure individuals regain their strength, confidence, and ability to perform tasks safely and effectively.

Generally, rehabilitation and work hardening involve increasing an individual's work duties, hours, and pacing to their maximal capacity. The goal is to facilitate the workplace reintegration of individuals who have experienced a reduction in work capacity or capability.

Incorporating work-based activities into rehabilitation plans and health and wellbeing strategies offers several key benefits. This approach aligns with the biopsychosocial model of rehabilitation, which has been shown to lead to more comprehensive recovery outcomes. Research indicates that addressing the whole person, including psychological barriers like anxiety and fear of reinjury, and integrating psychological and social support with physical

rehabilitation, reduces the need for long-term medical These activities help physical recovery and address There is much to consider when designing a RTW may be ideally suited to plan and support. The number required of the day and is commensurate with the commuting to work, possible homeworking and

medical care and improves return-to-work rates, (Bae, M., 2024, International Association for the Study of Pain, 2010). address psychological and social aspects, contributing to a holistic rehabilitation process. RTW plan. Use of specialists within a multi-disciplinary Occupational Health (OH) or Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) teams number of hours and days to initiate as the starting point of the RTW is determined by the physical and mental demands the length and/or reasons for absence. Consideration of the type of shift pattern and work is also essential. The effects of hybrid working should also be considered.

1. Physical/Functional Conditioning: Work hardening programmes focus on improving strength, endurance, flexibility, and coordination. They often include simulation of jobspecific tasks to replicate and increase capacity to meet the physical demands of the workplace. Establishing the individual's current physical condition and job demands is the starting point.

2. Psychological Support: Work hardening should address any psychological aspects of returning to work, such as confidence building and/or managing anxiety related to re-injury.

3. Multidisciplinary Approach: Workhardening programmes can be designed by a team of healthcare professionals, including OH nurses trained in rehabilitation, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, Vocational rehabilitation and mental health specialists.

4. Emotional State: The psychological impact of their condition and readiness to return to work will determine whether a rapid or gradual return is more appropriate.

5. Symptoms and Conditions: Symptoms and any aggravating factors will affect their ability to work. Research promotes a return to work despite symptoms, but specific tasks that may cause aggravation should be cautiously integrated.

Desensitisation may be required if an absence has been prolonged, and the individual has a significant loss of self-

confidence or self-esteem. Simple activities such as shopping in a busy town, building up general exercise for stamina, and socialising can help prepare the individual for returning to work. Social prescribing is an innovative approach in healthcare that connects people to non-medical services and activities within their community to improve their overall health and wellbeing. Social prescribing recognises that health is influenced by a range of social, economic, and environmental factors and aims to address these by connecting individuals to community resources. Link workers spend time understanding what matters to and individual and assist them in accessing relevant community services, such as activities including volunteering, arts and crafts, group learning, gardening, befriending, cookery classes, physical activities, and more. Social prescribing is particularly beneficial for people with long-term conditions, those needing support with mental health issues, individuals who are lonely or isolated, and those with complex social needs, particularly those who may be anxious about returning to a working environment with any of these issues, (NHS England, 2023, Gov.uk, 2022, Buck, D. and Ewbank, L, 2020)

1. Increasing Hours of Work: Increasing work hours from the initial start can be completed by increasing the number of days in a week worked or increasing the number of hours in a day. With each increment all biopsychosocial and workplace factors need to be considered. Included needs to be the response to the previous increment and the

magnitude of the next increment. This can help them adjust, ensures they do not overexert themselves and therefore help ensure a smooth transition back to full duties.

2. Endurance Capacity: The ability to handle the physical and mental demands of their job must be considered. Some individuals may perform better at different times of the day.

3. Reduced Days of Work: Normal rehabilitation may involve returning to normal shift durations at an agreed point but providing a bigger break than normal between work periods to allow for better recovery. This strategy is useful for roles where shorter working hours cannot be accommodated and helps build confidence, stamina, and resilience.

4. Incremental Increases in Duties: The initiation of RTW depends on the length of absence and extent of incapacity. A staged approach can help ensure a smooth transition, with regular reviews and adjustments to the plan to ensure its effectiveness. The duration of stages can be advised by appropriate OH professionals. The overall duration of a phased return to work can range from a few weeks to a couple of months, depending on the individual’s progress and the complexity of their job.

5. Temporary Restrictions: Some aspects of the role may need to be avoided, mitigated, or reduced if the employee has a temporary incapability or reduced capacity to undertake certain tasks. A Physical/ Functional Capacity Assessment/

Evaluation can help determine these modifications. Temporary redeployment to alternate roles may also be considered.

1. Work Task Redesign: If the employer or OH service has access to a specialist ergonomic team, they can work with the employee and manager to redesign tasks or advise on alternate techniques for task performance. This can help employees undertake tasks with less risk to their underlying health issues and regain physical stamina.

2. Targets and Supernumerary Roles: Setting measurable targets and reducing these can be as effective as a phased return in hours. Supernumerary roles, where the employee is accompanied by a colleague, can help build tolerance, confidence, and stamina.

3. Compliance with Treatment: Those receiving or nearing the end of interventions are likely to make a more successful and efficient RTW.

4. Financial Considerations: The financial implications for the individual, including pay during a phased return can affect progress. Consider government schemes like Employment Support Allowance (ESA) for those returning after a prolonged absence.

5. Home Working: Home working and hybrid working can help avoid travel fatigue and provide flexibility. However, it is essential to ensure workstations are set up appropriately and that the employee remains integrated into the workplace.

1. Job Role: The specific requirements and duties of the job need to be clear to all parties. Discussions with managers and colleagues can help address barriers to RTW.

2. Hours of Work: Understanding and agreeing on the feasibility and expectation of the individual's work hours, including shifts and overtime. Financial situations may also influence the ability to work overtime.

3. Psychosocial Flags: psychosocial factors play a significant role in the success of RTW programmes. These factors are categorised into yellow, blue, and black flags: (Gray, 2011; Shaw, 2009; Nicholas, 2002

4. Commuting and Access to Work: For some employees, concerns around commuting during peak hours may need to be addressed. Advice regarding travel outside peak hours can help alleviate fears of re-injury and anxiety. Consider "Access to Work" for transport support and assistance from colleagues or management.

1. Progression: Regularly reviewing the employee’s progress and adjusting the return-to-work plan as needed is crucial.

2. Planning: Setting clear objectives and agreeing on actions with anticipated timescales is crucial (Agimal, 2022). The RTW plan should be flexible and adaptable to the individual's progress and the needs of the business. Regular reviews and

adjustments to the plan may be necessary to ensure its effectiveness.

The primary purpose of a personcentred RTW or work hardening programme is to facilitate a smooth and successful transition back to work, ensuring that the individual is fully

prepared to safely meet the demands of their job, without risking relapse or injury, and improving the overall quality of life, (NHS England, 2025). These programmes aim to restore the employee to 100% of their role unless otherwise agreed.

Evidence shows that supporting temporary modifications to work roles, duties, or hours can be effective and cost -efficient when goal oriented. Such adjustments, often temporary, can facilitate staying at or returning to work and are typically easy to implement with little or no additional cost to employers, (Council for Work & Health, 2019).

Substantial evidence supports the efficacy of physical conditioning programmes that incorporate a cognitive-behavioural approach and intensive physical training, supervised by appropriate healthcare professionals or a multidisciplinary team. These programmes, which deliver a biopsychosocial model of healthcare, significantly enhance vitality, improve overall health outcomes, and reduce the number of sick days lost, (Jakobsen et al, 2017; Miki et al, 2021; Ibrahim et al, 2019).

Conclusion

Rehabilitation and work hardening programmes are vital for the successful reintegration of employees into the workplace. By considering the individual's physical, emotional, and psychosocial needs, and by setting clear, achievable goals, these programmes can help employees return to work safely and effectively.

ACC, (2004). New Zealand Acute Low Back Pain Guide: incorporating the Guide to Assessing Psychosocial Yellow Flags in Acute Low Back Pain. Wellington, New Zealand: ACC.

Equality Act, (2010). Chapter 15. Available:

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ ukpga/2010/15/pdfs/ ukpga_20100015_en.pdf. Last accessed 20th February 2017

Carvalho, A, (2007). How useful are flags for identifying the origins of pain and barriers to rehabilitation? Frontline. 13 (17).

International Association for the Study of Pain, (2010). Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Treatment of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. (2010). Available at: https://aped-dor.org/images/ FactSheets/DorMusculoEsqueletica/en/ Biopsychosocial.pdf [Accessed 26 Feb. 2025].

IOSH, (2015). A healthy return. Good practice guide to rehabilitating people at work. IOSH: Leicestershire.

Kendall, NAS, Burton AK, Main CJ, Watson, PJ, (2009). Tackling Musculoskeletal Problems: A Guide for Clinic and Workplace – Identifying Obstacles Using the Psychosocial Flags Framework. London: The Stationery Office.

Kendall, NAS, Linton, SJ and Main, CJ, (1997). Guide to Assessing Psycho-social Yellow Flags in Acute Low Back Pain: Risk Factors for Long-Term Disability and Work Loss. Accident Compensation Corporation and the New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington, New

Zealand. (Oct, 2004 Edition).

Lechner DE, (1994). Work Hardening and Work Conditioning Interventions: Do They Affect Disability? Physical Therapy. 74 (5). p471-493.

The Cochrane Collaboration, (2009). Work conditioning, work hardening and functional restoration for workers with back and neck pain (Review). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

The European Agency of Safety and Health at Work, (2016). Rehabilitation and return to work: analysis report on EU policies, strategies and programmes. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. p3.

Waddell G and Burton AK, (2006). Is work good for your health and wellbeing? Norwich: The Stationery Office.

Claire is the Operations Manager for the ‘Project Your Health’ initiative at the University of Central Lancashire. This project supports students in delivering quality preventative healthcare services to local community employers. Claire has 15 years of experience as a specialist occupational health clinician, specialising in occupational health and ergonomics, and over 20 years of experience in the field of physiotherapy. She is also a qualified teacher. Claire is a member of several professional organisations, including the CSP, HCPC, ACPOHE, VRA, iOH, and SOM.

Claire is passionate about supporting workplaces to help their colleagues and staff achieve an enhanced quality of life and improved health goals. She believes that a healthy workforce is the foundation of a productive and thriving organisation. Through her work, Claire focuses on implementing effective health and wellness programmes, ergonomic solutions, and preventative measures to reduce workplace injuries and promote overall wellbeing. She is dedicated to educating and empowering employees to take charge of their health, fostering a culture of wellness within the workplace.

By Dan Williams, Visualise Training and

Hearing loss can affect every aspect of a person’s life, but it’s particularly challenging in the workplace. Whether it’s missing out on important information in meetings or struggling with phone calls, hearing loss can create barriers that hinder both professional growth and day-to-day productivity.

What many people don’t realise is that hearing loss is often invisible. While someone might have difficulty hearing, they may not show any obvious signs. This can lead to misunderstandings, especially when colleagues or managers don’t acknowledge the challenges faced by people with hearing loss. The assumption may be that hearing loss doesn’t impact work unless it’s extremely severe, but even mild to moderate hearing loss can create significant difficulties.

Meetings are often where hearing loss becomes most apparent. Imagine sitting in a room full of colleagues discussing strategies and objectives, but the discussion becomes muffled or hard to follow. The challenge is that people with hearing loss might not always speak up to ask for clarification, especially if they fear being judged or interrupting the flow of conversation.

This can lead to the perception that they aren’t contributing or engaging with the

conversation when, in fact, they’re struggling to keep up. A few simple workplace adjustments, like using a microphone in meetings or providing meeting agendas and summaries, can make a significant difference in ensuring clear communication and reducing misunderstandings.

Employers have a legal and moral responsibility to accommodate employees with hearing loss. This could mean offering assistive technology like captioning services or ensuring that meetings are accessible with written follow-ups. But it also requires a cultural shift within the workplace, where the value of inclusive communication and the understanding of hearing loss are prioritised.

• Awareness: Employers and colleagues need to be educated about the challenges faced by employees with hearing loss and understand that it’s not just a “personal” issue; it impacts performance, morale, and success.

• Flexibility: Allowing employees to have access to meetings in formats that work for them whether it’s through captions, transcripts, or sign language interpreters creates a more inclusive environment.

• Compassion: Creating a workplace culture where people are encouraged to discuss their challenges without fear of

judgment is key to making sure everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed.

There are many misconceptions about hearing loss that have persisted for years, often preventing people from seeking the support they need or perpetuating stigma. Let’s bust some of these myths and look at the truths behind them.

While age-related hearing loss is common, hearing loss can affect people of all ages; more than 5% of the world’s population approximately 430 million people suffer from hearing loss. Causes can range from genetics and injury to exposure to loud noises or certain medical conditions. So, don’t assume that hearing loss only happens in later life. It can occur at any stage.

Hearing aids can help amplify sound, but they’re not a magical fix-all. They don’t restore hearing to normal levels and may not work equally well for everyone. Many people with hearing loss also struggle with background noise, distorted sounds, or hearing in difficult environments, which hearing aids alone can’t always solve. People with hearing loss might also need additional support,

Employers have a responsibility to accommodate employees with hearing

a legal and moral accommodate hearing loss.

like captioning, lip reading coaching, or assistive listening devices.

3: “People with Hearing Loss Can’t Participate in Conversations”

It’s easy to assume that someone with hearing loss is disconnected from social situations, but many people with hearing loss are perfectly capable of engaging in conversations. With the right tools and strategies, like lip reading or assistive technology, they can follow along and actively participate. The key is communication finding ways to ensure that the person with hearing loss feels included and understood.

4: “People with Hearing Loss Are Just Being Rude When They Ask You to Repeat Yourself”

People with hearing loss are often afraid to ask others to repeat themselves because it can feel awkward or frustrating. However, it’s not about being rude; it’s about the need for clarity. People with hearing loss may find it difficult to understand speech in noisy environments or when there’s background chatter. Instead of feeling impatient, be patient and supportive when someone asks for repetition or clarification.

“Turn It Up! The Frustration of Watching TV When You Can’t Hear It”

We’ve all been there sitting down to watch your favourite show after a long day, but something’s just not right. The dialogue’s unclear, the background music is too loud, or the sound effects

are drowning out the voices. For people with hearing loss, this is an all-toofamiliar frustration.

TV shows and movies are created with sound as a vital part of the experience, but for those with hearing loss, that’s often where the problem begins. Whether it’s the booming action sequences that overpower dialogue or the unclear speech due to poor sound mixing, watching TV can be a battle of frustration.

While subtitles are a helpful tool, they’re not always available or perfectly accurate. Often, they’re delayed, missing, or simply don’t capture the nuances of conversations. For people who rely on subtitles, a poorly synced or incomplete version can make a show or film feel unwatchable.

The good news is that the entertainment industry is beginning to recognise the importance of accessibility for people with hearing loss. Streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ have made huge strides in offering highquality closed captions and even options for descriptive audio. Some new TV shows and films are even created with accessibility in mind, offering clearer audio mixes that make speech more prominent.

For the home setup, many people with hearing loss invest in technologies like

hearing aid-compatible TV speakers, or even smart speakers that allow for clearer sound. Simple changes, like using subtitles, adjusting the volume, or investing in specialised tech, can drastically improve the TV-watching experience.

Hearing loss isn’t just about “bad ears.” It’s about the barriers created by society that make it harder for people with hearing loss to engage fully in life. This is where the Social Model of Disability comes in. Instead of seeing hearing loss as a personal deficiency, this model views it as a result of the way society is structured.

The Social Model of Disability focuses on changing the environment rather than “fixing” the individual. It emphasises the idea that people with hearing loss are disabled not because of their condition, but because of how society doesn’t accommodate them. In this context, hearing loss is not the problem the problem is the lack of accessible communication, spaces, and services.

In a world where spoken communication is dominant, people with hearing loss face unique challenges. However, these challenges

can be overcome with better access to information, such as captioning in media, better public announcement systems, or more inclusive social spaces. The Social Model stresses that the problem lies in the design of our environments, not the people who navigate them.

The key to an inclusive society is making small changes that benefit everyone. For example, having captions at public events, offering sign language interpreters at conferences, and ensuring workplaces have appropriate accommodations can level the playing field for those with hearing loss. As we move towards a more accessible world, the Social Model of Disability helps shift focus away from what individuals can’t do to what society can do to help everyone thrive.

To find out more about making your organisation more accessible for deaf colleagues and those with hearing loss, visit https:// visualisetrainingandconsultancy.com/ workplace-assessments/hearing-lossworkplace-assessment

To ensure your team is equipped to interact confidently and respectfully with colleagues and individuals who have hearing impairments, visit https:// visualisetrainingandconsultancy.com/training/ deaf-and-hearing-loss-awareness-e-learning

Last year, a colleague saved a life at work. It was a routine day of audiometry, spirometry, and skin surveillance on a customer’s site. My colleague “Jim”, carefully explained to an employee/client that the blue trace represented the left ear and the red the right; the top of the trace was quiet, like a leaf blowing in the wind while the bottom of the trace was loud like a jet engine; the left side of the trace is like the low notes of a piano and the right side of the trace, the high notes of the piano that the client had heard.

Jim noted that whilst the client’s right ear was as expected for his age, his left ear was not. Jim emphasised that although this was a screening audiometry test rather than a diagnostic test, the results required further investigation. Jim strongly recommended that the client take his audiometry trace along with a standardised letter to his GP, who would likely refer him for specialist assessments at the hospital.

Due to debate and discussion, has been moved to a possible to View the post

Jim later found out from the Health and Safety Manager that the client had been diagnosed with a brain tumour. Surgery to remove it had been successful, but without the audiometry test, the tumour might not have been detected until it was too late. The Health and Safety Manager confirmed the client’s comments that without Jim’s clear explanation of the results, they would not have sought medical advice at all.

It may seem unusual to get job satisfaction from a client’s traumatic experience, but Jim did because he knew that he had made a difference. As his manager, I was even more proud of not only Jim’s actions that day but also, the level of knowledge, skills, and

behaviours he consistently demonstrates at work.

Author: Anonymous

Jim is an Occupational Health Technician (OHT). He has a Degree in Sports and Exercise Science, is on the Perform and Interpret Spirometry Register with the Association of Respiratory Technology and Physiology (ARTP), and has successfully completed the British Society of Audiology’s (BSA) Screening Audiometry course, designed to enable attendees to ‘Interpret results and findings’ (British Society of Audiology, 2023). In addition, he has

workplace to promote compliance with prescribed asthma medication and support escalation processes in respiratory surveillance demonstrates not only his technical competence but also his commitment to improving occupational health practice.

discussion, this article blog, as this makes it comment.

completed 3 months of direct supervision, a portfolio of evidence of his knowledge, and a final assessment by a Registered Nurse, SCPHN(OH), and Practice Teacher to confirm that he has met the required standards of skills, knowledge and behaviours of an Occupational Health Technician. He has also worked with a GORD Specialist to understand OASYS scores, create referral criteria, and interpret serial peak flow readings. His proposal to introduce FeNO testing into the

Despite his expertise and being an enhanced technician, Jim has been told he is not competent to interpret and report on health surveillance results. Following comments from the HSE and recent HSE improvement notices, it is felt he cannot use face-to-face interactions with clients to motivate them to take proactive actions to promote their health, safety and wellbeing. This decision has undermined his self-worth and removed his career pathway. How long we can retain such a talented, passionate professional in Occupational Health, as a result, is now uncertain.

As for me, a SCPHN(OH), spending 4 hours per day reviewing health surveillance results which have a 100% accuracy rate is also demoralising. How long I will stay in Occupational Health under these conditions is also unknown.

No one can tell how many workers require health surveillance per year in the UK. To calculate approximate numbers, figures from the Office of National Statistics (ONS, 2024) were used.

The number of workers in Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing; Mining, Energy and Water Supply; and Manufacturing; Construction total 2,813,985,000 workers. This includes office and management workers who may not be exposed to health hazards at work and

those not requiring health surveillance but does not include those that do from other industries, suggesting that the figures may equal out. Based on organisational clinical standards, which require one hour per worker to perform and explain audiometry, spirometry, skin and HAVS2 surveillance, as well as provide health, safety, and wellbeing advice, the total health surveillance time for all these workers equates to 401,997,857 workdays per year. This does not include driver’s medicals, safety-critical medicals, drugs and alcohol tests, DNA rates, or escalation processes etc.

The Society of Occupational Medicine’s OH Workforce Paper (Society of Occupational Medicine, 2018) informs us that we have:

• 571 Specialists in Occupational Health (FFOM, MFOM, AFOM, DOccMeds)

• 216 Training Registrars

admin, travel, cleaning, and calibration), the direct cost of OHT time at £179 per day would amount to £71.96 billion per year.

A qualified OHA reviewing this work adds another £6.73 billion (£45,000 annual salary + employer costs = £54,000 per OHA per annum) to the annual bill. Nearly 3 times the MOD’s cost of operations and peacekeeping in 2023/2024 (Ministry of Defence, 2024) and a significant cost to UK industry.

‘Competence is the ability for every director, manager and worker to recognise the risks in operational activities and then apply the right measures to control and manage those risks.' Judith Hackitt, HSE Chair cited in (Health and Safety Executive, N.D.).

• 3200 SCPHN (OH) accredited OH nurses (data from 2015)

Additional from a freedom of information request from 2023, we have 2941 NMC accredited OH nurses (73% over the age of 50; and 23% over the age of 60)

If it takes 4 minutes per employee to review health surveillance activities check results, and release reports to employers, it will take those qualified OH nurses 26,799,858 days to complete the annual health surveillance checks. Practically speaking, that’s an additional 6172 qualified OHAs needed to review the required health surveillance. This assumes that qualified OH nurses are full-time and assuming recruitment into a profession which requires long hours checking test results of competent Occupational Health Technicians.

Consideration of training and salary would be an essential consideration and may preclude providers from delivering this type of service.

Competent Occupational Health Technicians (OHTs) delivering these services would take 42 weeks per year (allowing for annual leave and downtime), based on 4 days per week (to account for

The risk to life from a lack of competent health surveillance is recognised. However, restricting the interpretation of health surveillance solely to Registered Nurses with qualifications in Occupational Health also creates a significant workforce and service capacity gap.