The Inya Institute Quarterly Newsletter

Winter 2026

Myanmar is in the midst of its first general elections since the 2021 coup and will see the third and final phase held on January 25, 2026. Described by many, domestically and internationally, as sham elections, they will undoubtedly confirm the military regime’s renewed administrative and political grasp on the central parts of the country. Yet, what the elections mean for the whole country and the townships located in the regions and states where armed resistance has been raging for five years and where elections are not held remains to be determined.

Our team consulted with people through casual encounters and asked them about their views of these elections, as well as their experiences. While the feedback garnered by the team certainly does not claim to offer a representative image of the public’s view of these elections, it nevertheless offers a glimpse of how the military junta’s extensive coercion of the citizenry through fear continues to register in their minds. It also confirms how poorly the planning of the elections and establishment of voters’ lists was handled by the Union Election Commission, lending strong legitimacy to the claims that these elections are sham elections. Read our account on p. 9.

Also in the newsletter, 2025 CAORC-INYA Fellow Courtney Wittekind discusses the transnational fundraising activities purporting to support the pro-democracy movement that use social media tactics which, else-

In this issue

www.inyainstitute.org

where, have been decried as leading to anti-democratic outcomes. Focusing on Myanmar communities now exiled in Mae Sot, Thailand, Katherine Pulaski, another 2025 CAORC-INYA Fellow, explores first how resilience is cultivated among these communities through care practices and informal networks, and second the influence that imagined futures of a federal democracy have on community building and identity formation.

Following the success of its first edition held in 2024 in hybrid format at Chulalongkorn University, the institute together with Cornell University’s Southeast Asia Program (SEAP) and its Southeast Asia-based partners are now preparing for the 2026 International Interdisciplinary Conference on Myanmar’s Borderlands (2026 IICMB). The new edition will be held entirely online, and will offer, we hope, more scholars an ideal platform to compare their research findings and start or further pursue collaborative work before we go back to a hybrid format in 2028. Alternating between conference venues in Myanmar’s neighboring countries—in a format that encourages exchange and community-building—and fully online formats that allows for a broader reach and inclusivity seems like a good model to sustain a scholarly pulse and cultivate a more engaged community. See the conference announcement on p. 3!

The Inya Institute team in Yangon

Announcement 3 2026 International Interdisciplinary Conference on Myanmar’s Borderlands (2026 IICMB)

Reflections from the Field 4 Dilemmas of Digital Fundraising in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution, by C. Wittekind

Reflections from the Field 6 Resilience and Care at the Thai–Burma Border, by K. Pulaski

Testimony 9 Casting a Vote for Myanmar’s 2025 General Elections: Between Rejection and Coercion - Part 1

Ongoing Activities 12

Upcoming Events 13

New Books on Myanmar 16

Address in Myanmar:

50 B-1 Thirimingala Street (2)

8th Ward

Kamayut Township Yangon, Myanmar

+95(0)17537884

Address in the U.S.: c/o Center for Burma Studies

101 Pottenger House

520 College View Court

Northern Illinois University DeKalb, IL 60115 USA

+1 815-753-0512

Director of Publication:

Dr. François Tainturier

Administrative Assistant: Thin Thin Thar

Digital Resources and Info Assistant:

Shun Lai Pyae Sone

Education and Training Manager: Pyae Phyoe Myint

U.S. Liaison Officer: Carmin Berchiolly

Contact us: contact@inyainstitute.org

Visit us on Facebook: facebook.com/inyainstitute.org

Library: It currently holds a little more than 900 titles and offers free access to scholarly works on Myanmar Studies published overseas that are not readily available in the country. It also has original works published on neighboring Southeast Asian countries and textbooks on various fields of social sciences and humanities. Optic fiber wifi connection is also provided without any charge.

Library digital catalog: Access here.

Working hours: 9am–5pm (Mon–Fri)

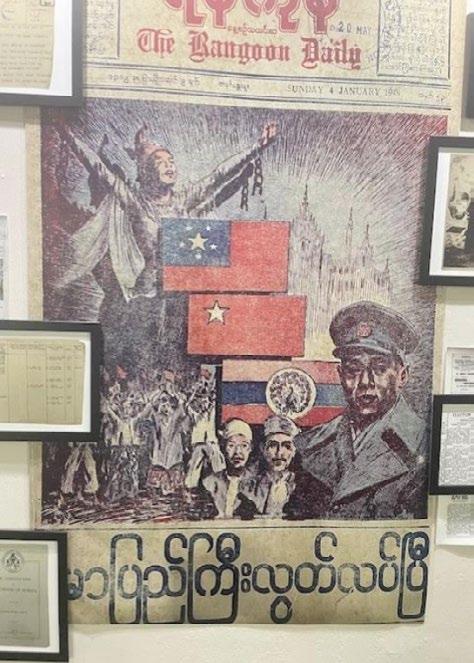

Digital archive: It features objects, manuscripts, books, paintings, and photographs identified, preserved, and digitized during research projects undertaken by the institute throughout Myanmar and its diverse states and regions. The collections featured here reflect the country’s religious, cultural, and ethnic diversity and the various time periods covered by the institute’s projects developed in collaboration with local partners.

Digital archive: Access here

The Inya Institute is a member center of the Council of American Research Centers (CAORC). It is funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act (2024-2028).

Institutional

Members

Center for Burma Studies

Center for Asian Research Southeast Asia Program

Northern Illinois University Arizon State University Cornell University

Center for Southeast Asian Studies Carolina Asia Center York Asia Center for Reseearch Northern Illinois University University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill York University

Academic Board

Maxime Boutry, Centre Asie du Sud-Est, Paris

Jane Ferguson, Australian National University

Lilian Handlin, Harvard University

Bod Hudson, Sydney University

Mathias Jenny, Chiang Mai University

Ni Ni Khet, University Paris 1-Sorbonne Alexey Kirichenko, Moscow State University

Christian Lammerts, Rutgers University

Mandy Sadan, University of Warwick

San San Hnin Tun, INALCO, Paris

Juliane Schober, Arizona State University

Nicola Tannebaum, Lehigh University (retd)

Alicia Turner, York University, Toronto

U Thaw Kaung, Yangon Universities’ Central Library (retd)

Board of Directors

President: Catherine Raymond (Northern Illinois University)(retd)

Treasurer: Alicia Turner (York University, Toronto)

Secretary: François Tainturier

Jane Ferguson (Australian National University)

Lilian Handlin (Harvard University)

Nicola Tannenbaum (Lehigh University)(retd)

Thamora Fishel (Cornell University)

Aurore Candier (Northern Illinois University)

Reflections from the Field

Dilemmas of Digital Fundraising in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution

Dr. Courtney Wittekind, an Assistant Professor at Purdue University, was one of our 2025 CAORC-INYA Scholars Fellows. Her project is entitled: “Influencing the Revolution: Social Media and Digital Fundraising in the Myanmar Diaspora.” Amid a global uptake of new technologies, a contentious debate has asked if social media is contributing to democracy’s decline. While social media was once considered a “liberation technology” able to undermine authoritarian governments, journalists have since detailed platforms’ role in increasing polarization and enabling election interference across the globe. “Influencing the Revolution” intervenes in this debate by examining the social media fundraising campaigns sustaining Myanmar’s “Spring Revolution.” The project argues that, while transnational fundraising aims to support democratic activism in Myanmar, fundraisers’ digital tactics depend on the very profit-generating mechanisms that make social media susceptible to undemocratic outcomes. The CAORC-INYA fellowships are funded by CAORC through a grant from the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs at the U.S. State Department.

“Even if you can’t fight on the front lines, even if you can’t make sacrifices directly, please support however you can from behind. Donate if you can. Click if you can. This isn’t just your duty as a citizen while the revolution continues. It’s part of fighting for your own future, isn’t it?”

In recent years, digital technologies have become central to the organizing and funding of resistance movements across the globe. In Myanmar, following the 2021 military coup, supporters of the Spring Revolution turned to online platforms to sustain their revolutionary efforts. These efforts have included mass protests, strikes, work stoppages, and eventually, armed resistance led by People’s Defense Forces and ethnic armed organizations. One of the most notable developments in the postcoup period was the emergence of fundraising campaigns that leveraged social media platforms, digital advertising networks, and even mobile applications to generate funds for revolutionary causes. As the quote that opens this reflection highlights, fundraising campaigns carried out through social media have enabled widespread participation in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution. This is true even for those who are unable to contribute their limited financial resources or unwilling to expose themselves to bodily harm. Yet, the same digital platforms that underlie revolutionary fundraising also raise significant challenges for actors in Myanmar and its diaspora. Revolutionary supporters confront not only the military’s surveillance network and its increasing control over new technologies. Campaign organizers and supporters also face an array of other constraints—technical, political, and ethical—imposed by the same digital platforms that facilitate fundraising efforts.

From May to July 2025, I expanded upon an existing ethnographic and digital research project that traces the evolution of online fundraising campaigns supporting Myanmar’s Spring Revolution. Much of my research on this topic has taken place in digital space through the archiving of thousands of public social media posts. But, as a CAORC-Inya Fellow, I was able to

travel to Thailand and conduct in-person fieldwork in Thailand. I also used my research period as a chance to reconnect with former students and junior scholars from Myanmar, some of whom joined this project as collaborators. Visiting both Chiang Mai and Mae Sot enabled me to observe fundraising initiatives first-hand. I also interviewed campaign organizers, participants, influencers, and “behind the scenes” actors such as web developers and programmers.

When I began this research following the coup, I was drawn to the ingenuity of fundraising campaigns that transformed everyday digital engagement into assets for the revolution. Click campaigns, in particular, stood out. These initiatives invited users to visit ad-saturated websites, refresh these pages, and interact with content in ways that generate advertising revenue. For many campaign participants, "clicking" was a form of defiance accessible to those with limited financial means: as one influencer told me, “to click, all you need is time!” Such campaigns were widely promoted as a form of digital solidarity, and their early popularity in 2021 suggested a broad base of support within and beyond Myanmar.

But, as I have conducted interviews with organizers and donors, my early impression of such campaigns has been challenged by facts on the ground. My initial curiosity about the creative, insurgent use of social media platforms to sustain resistance has deepened into a more complex understanding of the dilemmas these campaigns face. Digital fundraising is not only a site of creative reappropriation of new technologies but also a site of struggle, compromise, and constraint. Organizers I interviewed in June and July 2025 spoke candidly about the challenges of sustaining click campaigns over time, and not only because of the actions of Myanmar's military. Many also described how platform restrictions—such as account suspensions, throttled visibility, and monetization limits—have disrupted their organizing work. On platforms like Facebook, these constraints were often imposed suddenly, and their terms were difficult for users to understand. Often, campaign organ-

izers were given no opportunities for communication with the platform and very narrow avenues for appeal. One wellknown promoter of fundraising campaigns I met described the dynamic as a “cat and mouse game,” explaining to me that: “We try something new, and the platforms expand their policies to stop us.”

This comment, shared during an interview in Mae Sot, captured a sentiment echoed by many others: that fundraising efforts were constantly adapting to platform policies and community standards that shifted without warning or explanation. When paired with my digital ethnography of content posted on social media sites, these comments revealed a persistent tension. The same platforms that enabled digital fundraising also imposed limits that could undermine campaigns or even meaningfully shift their goals. Over the course of the summer, I began to see the imposition of platform constraints not as a series of isolated incidents, but as a broader pattern that underlay platforms’ policing of user activity deemed illegitimate or, even more commonly, unprofitable. Digital platforms, while offering tools for organizing and outreach, also operate according to commercial logics that routinely conflict with the goals of the revolutionary movements.

This realization was reinforced by social media archiving work I have completed since 2021. This archiving has involved collecting thousands of public posts from large Spring Revolution fundraising groups. In analyzing these posts, I saw shifts in messaging, changes in platform use, and increasing caution in how organizers framed appeals. Posts that once amplified direct calls to action or graphic images of military atrocities became more subdued over time, avoiding keywords that might trigger account suspensions or flagged content reviews. In interviews, influencers explained that they had learned to self-censor when they posted material related to their revolutionary aims. But this was not only out of fear of the military; they also hoped to avoid being penalized by the platforms that increasingly held them, and their audiences, captive.

These experiences have led me to reflect more deeply on the ethical and political dimensions of digital fundraising. What does it mean to monetize social media engagement in the service of a revolution? How do organizers navigate the trade-offs

between cultivating a broad (and therefore lucrative) reach and the risks that come with a large audience? And what happens when the very same platforms that facilitate fundraising also act as gatekeepers, shaping what is seen, shared, and financially rewarded in real-time?

Importantly, these questions are not unique to Spring Revolution fundraising campaigns. Similar dynamics are playing out in other contexts where activists rely on digital platforms to raise financial support, including in Gaza. What makes Myanmar’s case particularly striking, however, is the intensity of the digital repression carried out by the military, alongside the centrality of digital space to the Spring Revolution. With physical organizing dangerous in Myanmar and rendered impossible by distance for many in the diaspora, social media platforms have become essential. Yet the limitations of these platforms are acutely felt. Even more critical is the fact that, in Myanmar, platforms’ policies and their sudden imposition can have life-and-death consequences, especially for campaigns ensuring populations’ access to necessities like food and humanitarian aid.

As I continue this research, I remain interested in how fundraising campaigns evolve in response to pressures from both Myanmar's military and global digital platforms. I plan to explore how platform incentives shape not only fundraising methods but also the messaging strategies, emotional appeals, and political narratives that circulate globally, both on- and offline.

Ultimately, my fieldwork as a CAORC-Inya Fellow reinforced a belief that digital fundraising is both a powerful tool and a site of struggle for political actors in Myanmar and in other contexts across the globe. Digital platforms offer new avenues for political participation and solidarity-building across space and time, but they also demand constant and often contentious negotiation with a range of powerful actors. For campaign organizers and supporters alike, the work of sustaining a revolution through online fundraising is not only reliant on creativity and commitment but also on campaigns' ability to navigate commercial constraints. Reckoning with this fact is the first step in thinking more critically about the politics of digital resistance broadly.

Pic. 1: A Photo of Chiang Mai from Doi Suthep

Reflections from the Field

Resilience and Care at the Thai–Burma

Border:

Community and Organizational Networks in Mae Sot

Katherine Pulaski, a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at University of Wisconsin-Madison, was one of your 2025 CAORC-INYA Short-term Fellows. She describes her project entitled “Border Spaces and Familiar Faces: Hope and Resilience Among Burmese Migrants in Mae Sot, Thailand” as follows: “This project focuses on the connections and relationships forged among refugees from Myanmar currently residing in Mae Sot, Thailand. Border spaces, as areas both highly regulated and simultaneously ignored by the state, create zones of exception in which the constant presence of fear, anxiety, and homesickness comingles with hope and resistance. Using ethnographic research methods, this project will trace the connections that form among formal and informal organizations that work to support Burmese refugees. Katherine will focus on joyful moments that disrupt persistent trauma from war and loss and allow for different ways to navigate life.” The CAORC-INYA fellowships are funded by CAORC through a grant from the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs at the U.S. State Department.

Overview

This short-term, pre-dissertation project explores organizational and community approaches to healing and resilience in Mae Sot, Thailand. It focuses on the programs, practices, and collaborations that emerge through both organizational programming and personal relationships, with the hypothesis that such networks play a vital role in navigating identity, belonging, and daily life in a borderland context. By employing ethnographic methods, including semi-structure conversational interviews and participant observation, this research aims to develop a preliminary understanding of the networks that sustain individual and collective resilience in Mae Sot. For this preliminary research, I focused on two key questions: (1) How resilience is cultivated among Burmese communities living in Mae Sot, Thailand and the roles that organizations, care practices, and informal networks play in supporting this resilience; and (2) The influence that imagined futures of a federal democracy have on community building and identity formation in Mae Sot, Thailand.

Ethnographic research, or the practice of interviewing, participating, and observing various elements of life within a specific cultural context, comes with many obstacles. Anthropologists have worked to redefine anthropological codes of ethics and research techniques to address the colonial histories that accompany legacies of ethnography. In addition to cautious navigation of true informed consent, trauma informed interview techniques, and recognizing of the researcher’s own positionality, research in Mae Sot includes additional dynamics to remain aware of. The Burmese population in Mae Sot are often impacted by multiple factors, including the ongoing civil war in Myanmar, socioeconomic precarity, tensions surrounding documentation in Thailand, and an overall lack of resources to continue learning, working, and living in a second country. Further, due to Mae Sot’s long history as a zone for border trade, a destination for migrant workers, and a safe haven for those fleeing the violence of the Myanmar military junta, many researchers have gone to work and learn more from the communities living there. This has caused what some scholars call “research fatigue,” in which communities feel frustrated with scholars conducting research with little to no change in their overall situation.

Painted wall in Mae Sot

Methods

Given these complexities, I felt uncertain about starting my preliminary dissertation work in this town. Despite concerns about being perceived as an “extractive” graduate student, I was very lucky to be welcomed into the home of many reporters working to share on-the-ground information about the ongoing conflict in Myanmar. Similar to many new-comers, I likely often fell short on fulfilling certain roles, such as cooking good meals and navigating the local market. However, my hosts were kind and generous, allowing me to assist with food preparation and cleaning, while sharing elements of their everyday life. While I did not officially record and take field notes about this space, due to concerns about privacy and intmacies that extend wellbeyond research. However, the opportunity to live, chat, and develop friendships with these individuals greatly influenced by experience, as these relationships helped me to learn more about wider community dynamics, ongoing events, and important places to visit during my stay in Mae Sot.

Beyond the connections made possible through these relationships, the most effective way to connect with other organizations and community members was a mixture of formal requests for interviews and site visits, along with the willingness to “say yes” to most opportunities that arose. “Showing up” or simply being present at the different workshops, conferences, or public events that often spring up around Mae Sot helped me to better integrate into the local fabric of the community and start to get a sense of the extensive and entangled relationships networks that hold this town together. As sometimes more formal email introductions were lost in the business of everyday life, informal and in-person chance meetings worked well to establish myself as an invested and committed researcher.

Site Visits

Throughout the summer, I conducted eight site visits and six formal interviews. The purpose of a “site visit” was mainly to engage in participant observation and get a better sense of the environment and emotions that make up organizational spaces. Often, organizations that served as a meeting point for Burmese communities to engage in activities or networking were well removed from town. While presenting obstacles

for those who have no access to inexpensive transportation, these settings effectively “carved out” a safe space for Burmese communities. While these places were intentionally organizationed and often registered with the Thai government either through a Thai CEO or a collaborating umbrella organization, informal meeting spaces also formed more organically throughout town. These areas, however, were more vulnerable to police raids and drawing the attention of other Thai community members who may resent Burmese presence in Thailand. Thus, this element of research served to help better understand the importance of geographical space in Mae Sot.

Interviews

The interviews conducted over the span of this research often lasted about one hour and were almost exclusively with NGO employees or founders. Most interviews were conducted in English, and provided diverse perspectives regarding education, health, and community development. Interviewees included a mix of those who identified as European, Thai, and Burmese, providing additional layers of complexity to this study. No interviews were recorded, though I took extensive field notes and typed up interview transcripts after the initial conversations. Though several open-ended questions were prepared to give the interview direction, many individuals diverged to tell me more about what they found was most important to them. Participants generally agreed on the major issues facing Burmese populations, focusing on themes such as access to quality education, issues with documentation, financial struggles, and concerns about physical and mental health.

Discussion

Organizational Relationships

I found that a mixture of organizational and personal networks plays a large role in determining care practices for Burmese communities living in Mae Sot, depending on individual positionalities. For instance, many of the non-profits support the younger members of the Burmese community through financially supporting Migrant Learning Centers (MLCs), organizing opportunities for children to play sports, or providing community classes for painting, dancing, or playing music. Other organizations target young adults through supporting

Graduate Education Development (GED) prepration courses, English language courses, mental health programs, and other opporuntities for continuing education. Finally, some organizations are directed at supporting migrant laborers, advocating for fair employment practices, providing education courses about sexual haressment and gender discrimination, and providing medical services for those injured while working. While these services often cross demographics (adults can take community art classes, young mothers can use health services, etc.), these systems of care remain relatively removed from the mundane threads of everyday life in Mae Sot. In other words, while addressing critical gaps in social services available to migrants, the metaphorical and physical “removedness” of these spaces sometimes do not permeate the systems of care needed to survive daily life.

Personal Networks

An additional dimension of care arises through personal relationships, either preexisting before movement into Mae Sot or formed through necessity once arriving to Thailand. While organizationally organized spaces provided nexuses for networking and relationship building, personal relationships and introductions resulted in more intimate forms of connection. For instance, while professional or more collegial relations formed from workshops or conferences, elements of friendship or filial dynamics appeared outside of formally structured events. Dynamics of care at this level often appear more as obligations or expectations due to the shared experiences with the systematic

violence Burmese communities living in Mae Sot experienced. For instance, cooking and sharing food, assisting with housing, providing job references, aiding others with interactions with the authorities, and other daily takes are not viewed as “care” but as necessarily shared activities for survival. However, these small extra tasks often build up to overwhelming levels, where large portions of one’s day are filled with hours volunteering one’s time toward both physical and emotional labor.

While such expectations are largely tied to necessity and shared experiences, sentiments of solidarity in the name of resisting the tyranny of the Myanmar military junta also shape forms and expectaions of care. Thus, the sentiment that “others have it worse” rings throughout discussions as people commit to serve others within the community who share he common goal of eventually returning to a free and federalized Burma. At the same time, as the civil war continues to stretch on, many indivdiuals have shifted visions of the future to one that entertains assimilation into Thailand. Therefore, many services, activities, and educational courses are focused on providing paths toward acclimating to Thai society. This includes an emphasis on learning Thai language, developing skills to contribute to Thailand’s economy, and finding new methods of securing more permanent documentation. Thus, while the vision of a federal democratic Burma still pervades dominant discourses about the future, organizational and personal networks have shifted toward preparation staying in Thailand on a longer-term basis. Thus, this preliminary work has provided a glimpse into the political, economic, social, and cultural elements shape systems of care and visions of the future within Burmese communities in Mae Sot, Thailand.

4: Rohingya Exhibit Pic. 5: Bangkok Office

Testimony

Casting Votes for Myanmar’s 2025 General Elections: Between Rejection and Coercion - Part 1

Myanmar is in the midst of a campaign for general elections that has received some international media coverage and the results of the first and second phases were recently made public by the military junta. Without any surprise, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the junta’s proxy party, was declared winners for most seats at the two national parliaments (Amyotha Hluttaw and Pyi-thu Hluttaw), and the regional parliaments (Daing-dethagyi Hluttaws) amidst a participation turnout of 52% (1st phase). A third and final phase of the elections will take place on January 25, 2026. In this context, our team in Yangon reports on the experience and perspectives that people are willing to share in a context not conducive to openly expressing one’s views. Our account is based on anecdotal evidence collected from people met during casual encounters and residing in the Yangon, Ayeyarwaddy, and Sagain regions, and the Shan State. It is structured around the following themes: (1) public awareness of the election, individuals’ perceptions and sentiments toward it; (2) their plan in relation to the vote; and (3) events that occurred in their community before and during the election.

People’s awareness and knowledge about the 2025 elections

Generally, the general elections are not a popular topic discussed by people consulted for this piece. A 45-year-old housewife from Mawlamyine said the following,

“My family hardly talks about the election because my husband does not like talking about this at home.”

In places like Taunggyi and, even more so, Kale, where tensions between military and resistance forces are still high, more than the lack of interest, these are the security concerns and the fear of being overheard by people close to the administration that explain people’s reluctance to discuss the topic. Our contacts based in these two cities have typically refrained from discussing this topic with their family members openly or on the phone. A Yangon-based 34-year old former female teacher echoed this by saying,

“My family members said that people do not discuss this [election]. They are very careful not to discuss this as the ward officers are partners with the soldiers and they are afraid that they will inform them when he hears our discussion.”

Combined with a reluctance to discuss them, the people approached for

this account had also a very basic and vague awareness of the 2025 elections. The source of their knowledge is mostly through the Facebook pages of such media like BBC Burmese, Irrawaddy News, and Khit Thit Media. Also included in people’s sources of information are the media accounts of social influencers on TikTok and other platforms. Most people approached do not know the total number of parties involved or their respective names. They only know of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), People Pioneer Party (PPP), and People’s Party (PP)—the three parties that seem to be the most visible on social media and signboards planted in the public space. Only a few of the people approached would know the names of some representatives from the People's Party: no one would know the names of representatives from other parties. Also, only a few know of ethnic parties, for instance, Pa-O National Organisation (PNO).

Pic. 1: A signboard in front of Yangon’s City Hall (Getty)

Most participants could not point to specific websites or sources useful for identifying all the parties and their representatives. This underscored how little interest most people approached for this piece had for these elections. A 27-year-old female engineer from Kale confirmed,

“I do not know where to check [for this kind of information]. But, even if I know the websites useful for checking the parties and parties' candidates involved in the 2025 election, I will not do it for sure.”

A 34-year-old former female teacher in Yangon, said: “I saw a few representatives featured on road side boards but I do not remember anything [the name of the party and its representative].” Another 33-year-old female former teacher in Yangon added: “I heard that there are around 50 parties in the list but am not interested in learning about them.”

As earlier mentioned, this 2025 election will be held over three phases. Despite official public announcements, most of the people approached for this account only mentioned the two first phases. A 45-year-old male daily wage worker from Pathein, explained to us how he understands the process,

“I have to vote on December 28. But I heard that, in the second phase, the people who are not listed in the voters’ list and who haven’t voted in the first phase have to vote.”

Most of the people approached could not confirm where they had to cast their vote. One exception, however, was a 50-year-old housewife from a ward in Pathein explaining that,

“They invited people to check the voters’ list at least two times; first in October and second in early December. Our ward has a polling station, so we already knew where to go to cast our vote.”

A major issue that has caused public skepticism even before the start of the elections has been the availability of voters’ lists in townships where elections are planned and how they were compiled. A Kale-based 26-year old female engineer noted,

“I think the election will be held around December 20; therefore, my

region will also hold it at that time. But, my village is in the list of areas where the election will not be held since the military regime cannot rule completely and the tension between military and armed [resistance] forces is also very strong. So no civil servants dare to go there and collect the population data for preparing the list of voters.”

Even in the Ayeyarwaddy Region, which is often perceived as the region with the lowest level of conflict, the Union Election Commission (UEC) announced through an official notification (164/2025), as reported by local news outlets, that elections would not be held in two villages after the minimum requirements set by the UEC were not met there.

Even though the campaign has seen parties’ representatives and and their proponents sharing videos through social media platforms like Facebook and TikTok, most of the people approached do not remember any motto or slogans. The Kale-based female engineer noted only the USDP’s slogan shown on the signboards: “[For] a stronger Myanmar (

And a Yangon-based 23-year-old female student mentioned U Pike Htwe’s slogan, USDP representative, “We must be better than the previous people (taken to mean ‘previous government’ (

).”

In Shan State, the public events organized for the different parties were noted by a Taunggyi-based 26-year old female freelance teacher who said,

“I saw once that they blocked the road for 20 minutes and distrib-

uted pamphlets to the pedestrians. Then, they played the election songs loudly on the street and in procession. Honestly, I am not interested at all in whatever they do. I do not want to see them, hear their voices, and know about them.”

Attendance to campaign events is sometimes required as was the case in a ward in Pathein. The ward officers summoned the residents to attend a meeting about ward affairs at a school. However, when the meeting started, it turned out that it was solely for the purpose of listening to the promotion of USDP.

Requirements to cast a vote

Since September, the public has been flooded by SMS messages from the UEC inviting them to check voters’ lists placed at ward offices. People have also been encouraged to inform their ward office if names were missing.

Closer to the election, in October, more proactive methods were used by ward officers to push people to check the voters’ lists. In Pathein, for instance, a farmer in his mid-50s approached for this piece explained that,

“Some officers visit every household in their quarter and invite people to check the voters’ list. They expect people to inform them if a family member’s name is missing. So we have to do it and if a name is missing, the identity card must be given so that his/ her name is added to the list.”

The situation in Yangon is different. For the first phase, the ward officers were

Pic. 2: Polling station officers (AFP)

not very active and not making many announcements about the elections. This, however, changed before the second phase. Despite all the flood of the SMS messages, most people approached have not shown any interest in checking their names. A 55-year-old male small shop owner, originally from Rakhine State, mentioned that,

“As we [he and his family] have to extend the stay permit as guests here [Yangon], I know that they have our names. Whatever decision I take regarding checking the voters’ list, I think we all have to cast a vote here. It is so obvious.’’

On the other hand, a Yangon-based 54-year-old male home store owner from Yangon willing to check the names shared the following concern,

“I need to go and check the voters’ list in the ward office but I haven't done it yet. There are groups of thuggishlooking guys [hired by the ward office]

who stand at the entrance of the office. So, nobody dares to go and check the list.”

Within the Yangon migrant communities, the rumor mill has been buzzing with unverified announcements that, for casting their vote, Yangon-based migrants

Ongoing Activities

would need to show some documents such as an identification card, household registration list, and proof that they have been living in the current place for at least three months.

To be continued in the next issue!

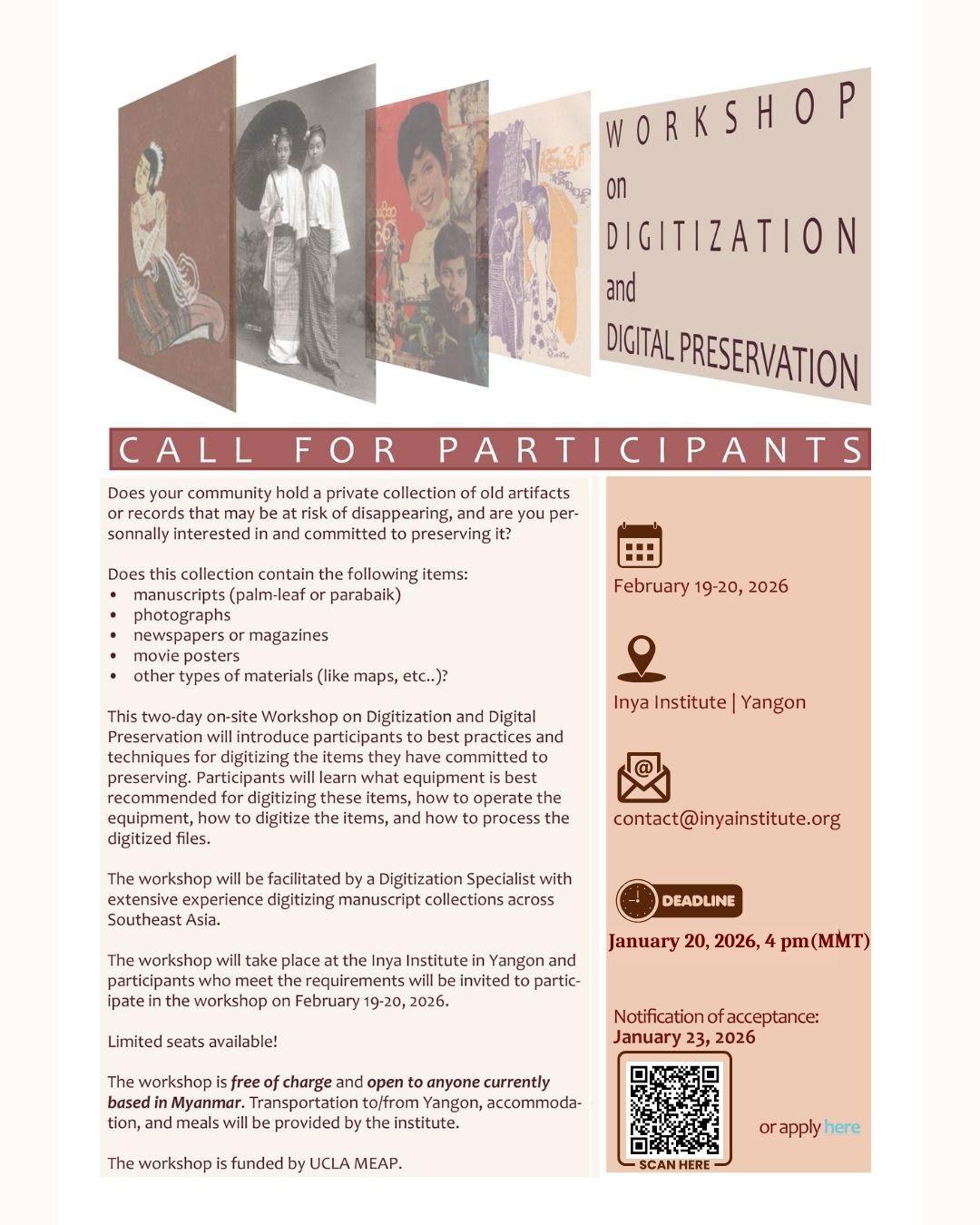

Training of Language Teachers specializing in the Languages of Myanmar - Part 2 (Aug. 2025-Feb. 2026)

Following the success of our Training of Language Teachers specializing in the Languages of Myanmar - Part 1 held online on June 13-15, 2025 (see report here), Part 2 of the training started on August 2025, marking the next step of our collaboration with University of North Carolina’s Carolina Asia Center and Cornell University’s Southeast Asia Program (SEAP).

Part 2 involves the training of a selected cohort of Part 1 participants under the supervision of Yu Yu Khaing, Myanmar/ Burmese language instructor at Cornell University, and Ehtalow Zar, Karen language instructor at the Saint Paul Public School Systems (SPPS, MN).

Part 2 language teachers have been introduced to a new language teaching approach inspired by backward design methodology and relying on unit learning

target forms before creating the content of unit materials. This new teaching approach has been met with some difficulty by our language teachers who have had some hard time to define the objectives of their units first. However, in the long run, the training will prove of great benefit for them and the development of their pedagogical skills.

Part 2 also offers the language teachers affiliated to the Inya Institute a great opportunity to create an advanced beginners’ level course for Karen, Kachin, and Shan languages that will come in addition to the beginners’ level organized by the institute every year. Stay tuned for our announcements!

Pic. 3: Voters at a polling station in Yangon (AFP)

Pic. 1: Screenshot of Part 2 Trainers’ lecture held on December 17

2025-26 Myanmar’s Borderlands Research & Mentoring Program - Online Workshop Series

Our six groups of Junior Researchers have made significant progress over the past few months moving from the research design stage to questionnaire design and testing, and to the data collection stage. Dr. Kimberly Roberts, the 2025-26 Research Fellow and Mentor of our Myanmar’s Borderlands Program, led a series of online workshop starting with an All-group session on October 2. This session ensured that all groups developed a shared understanding of how to prepare for this data collection stage. One-on-one sessions with each group then followed. During these sessions, Kimberly addressed the group’s questions and discussed possible concerns. Most groups planned for online data collection due to logistical constraints. Some, however, were able to travel to their field sites (see pictures show below).

Groups 3 (Ze Nyoi and Seng Mai Maran) working on “Post-coup economic and livelihood changes along

the Kachin—China borderlands” and Group 6 (Lin Thiha, Bulla Muhe, and Mohamed Faisel) on “Education access in conflict-affected areas and marginalizedcommunities in Northern Rakhine and Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh” showed great progress in their work. Both needed only few adjustments to their questionnaires.

Group 1 (Peter Lin Mang and Nyein Min Soe) working on “Basic needs of Chin refugees along the India—Myanmar border” and Group 4 (Aike Sam, Su Nandar Htet, and Naw Teresa Shalom) on “Challenges and struggles faced by Wa ethnic minority groups in preserving Wa language” had some difficulty breaking down their main research questions into more manageable subquestions. Revisions were done and Group 2 (Naw Gay Ler Say, Oo Myar, and Alexander Par Reh) on “Challenges to access to inclusive secondary education among Karenni youth along

the Thai Myanmar border” had to better align interview questions with their core themes. Their revisions were promising.

Group 5 (Yadanar Oo, Su Mon Oo, Naw Thae Lay Wah, and Par Zing) on “Psychosocial challenges and support systems among youth in refugee camps in Thailand and Mizoram” have addressed sensitive concerns very compellingly and their revisions are excellent.

A new series of online worshop on data analysis is about to start in early Februar. It will also provide all participants to discuss the lessons learned from the data collection phase. A third and final series held in late April will focus on reporting research findings.

All groups will present their 10 month-long research work at a final workshop organized in conjunction with the 2026 International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Myanmar’s Borderlands held online on July 24-26.

Upcoming Event

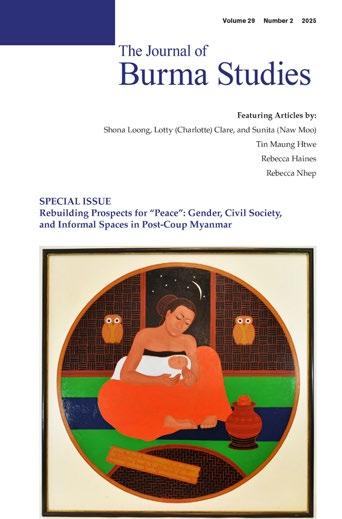

Journal of Burma Studies |

Center for Burma Studies

Northern Illinois University

SPECIAL ISSUE NOW AVAILABLE HERE!

Volume 29, Number 2, December 2025

Table of Contents

• General Editor’s Note

Aurore Candier

• Special Issue Introduction: Rebuilding Prospects for ‘Peace’: Gender, Civil Society, and Informal Spaces in Post-Coup Myanmar

Julia Palmiano Federer, Aye Myat Su Wai, Laura O’Connor, Mariana Savka

• Tending to Territories of Life: Indigeneity, Gender, and Peacebuilding in the Salween Peace Park

Shona Loong, Lotty (Charlotte) Clare, Sunita (Naw Moo)

• Feminist and Marxist Perspectives on Women’s Labor Leadership in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution

Tin Maung Htwe

• Women’s Principled Tactical Pluralism: Understanding the Cases of Sisters2Sisters and the Spouses of People’s Soldiers

Rebecca Haines

• Clientelism in Myanmar Residential Care Facilities

Rebecca Nhep

Annual Membership

Membership of the Inya Institute is now available for Institutions as well as Individuals!

Despite Myanmar’s current multidimensional crisis, the Inya Institute continues to operate in Yangon providing educational and training opportunities to Myanmar students, supporting scholarship by Myanmar and International researchers in Myanmar and in third countries, and offering language learning opportunities for those interested in Myanmar’s linguistic diversity. It is also one of the few libraries currently open to the public in Yangon. Interconnectedness between Myanmar, the U.S., the Myanmar diaspora in the U.S. and elsewhere is more important than ever and the institute is keen to support this value as shown by the activities presented in this newsletter. You can be part of this so please consider becoming a member of the Inya Institute! Contact us at: contact@inyainstitute.org

I NSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Any recognized academic or educational institution in the United States or Canada may become an Institutional Member of the institute. If a representative of an institutional member chooses to send a delegate to serve on the board of directors, he/she has an opportunity to shape the institute’s programs and activities.

Other benefits include: (1) Recognition of institutional member status in the institute’s quarterly newsletter; (2) Publishing of members’ scholarly events in the institute’s quarterly newsletter; (3) Invitation to join online events, including conferences and webinars, organized by the institute.

Annual institutional membership dues are $400.

I NDIVIDUAL MEMBERSHIP

Anyone may become an Individual Member of the institute, upon application and acceptance by the institute.

Benefits: (1) Inclusion in the institute’s listserv of those institutions and individuals receiving the quarterly’s newsletter; (2) Invitation to join online events, including conferences or webinars, organized by the institute; (3) Reduced fees for the language learning opportunities developed by the institute.

Annual individual membership dues are $25.

Upcoming Events On Myanmar

January Event

1. Water in Myanmar: Linking Environmental Issues with Policy Solutions

Location: University of Michigan

Date: January 16, 12:00 -1:00 PM (ET)

Speaker: Saw Yu May

This presentation examines Myanmar’s water challenges, from pollution and overuse to climate and governance pressures. It links research-based on water issues and community livelihoods with national policy efforts, highlighting the gap between environmental needs and implementation of the 2015 National Water Policy. The talk underlines the importance of integrated, participatory approaches for sustainable water management in Myanmar.

More info here

February Event

1. Film Screening: Thabyay: Creative Resistance in Myanmar

Location: University of California, Berkeley

Date: February 6, 5 PM (PT)

Director: Jeanne Hallacy

Producer: Gregg Butensky

Total Running Time: 62 minutes Myanmar is one of the deadliest conflict areas in the world, yet there is little international attention paid to the ongoing brutal oppression there, and to the courageous resistance to it.

Thabyay: Creative Resistance in Myanmar follows four democracy revolutionaries who are finding creative means to fight against the military junta. Some take up arms while struggling to stay true to their commitment to non-violence, while others engage in “artivism,” using music, poetry, and art to bring about a peaceful, free, democratic, and truly inclusive future for all people in Myanmar.

More info here

March Event

1. Nations, DissemiNation, ImagiNation and its people: Internal Exiles in post-coup Burma

Location: University of Michigan

Date: March 20, 12:00 -1:00 PM (ICT)

Speaker: Ei Thin Zar

While the nationalizing of education—in which the very idea of nation is disseminated—makes a certain kind of citizen that the nation requires, in a double gesture of hope and fear, it also produces forms of exclusion. The desire to be included in the very thing that excludes creates ‘internal exiles’ with lost identities—individuals who are ‘a stranger to one’s own country, language, sex and identity.’ In the case of Burma, the education system fashions the desired type of citizen, specifically the Burmese-speaking, Buddhist Burman. At the same time, this process establishes the constituted outside as Others (non-Burman or nonBuddhist). However, in the aftermath of the 2021 coup, a distinctive educational space arose, enabling its participants to imagine new forms of social belonging. Drawing from Homi Bhabha’s two distinct forms of nation—the pedagogic and the performative—this presentation explores how the nation’s people are made in a double narration: one as the objects of nationalist pedagogy in the fixed discourse of the nation, and the other as the. subjects of the processes that erase those discursive fixations.

More info here

April Event

1. Socialist Meaning-Making Through Rice and the 1967 Rice Riots in Burma/Myanmar

Location: The London School of Economics and Political Science

Date: April 1, 12:00 - 1:15 PM (GMT)

Speaker: Tharaphi Than During Burma’s Socialist Era (1962–1988), rice was not just a staple — it was a symbol of state power and everyday resistance. Declared property of the state, rice production was tightly controlled through a web of permits and quotas. Yet farmers subverted this system, withholding highquality grain for personal use or the black market while supplying inferior rice to the government. These quiet acts of defiance turned rice into a contested site of negotiation between state and society. In August 1967, simmering tensions erupted into

rice riots across the country, culminating in a brutal crackdown in Sittwe, where dozens were killed. This talk explores how rice became central to socialist meaningmaking, resistance, and the politics of survival in Burma.

More info here

New Books On Myanmar

InterAsian Intimacies across Race, Religion, and Colonialism

Chie Ikeya

Cornell University Press, 2025

In InterAsian Intimacies across Race, Religion, and Colonialism, Chie Ikeya asks how interAsian marriage, conversion, and collaboration in Burma under British colonial rule became the subject of political agitation, legislative activism, and collective violence. Over the course of the twentieth century relations between Burmese Muslims, SinoBurmese, Indo-Burmese, and other mixed families and communities became flashpoints for far-reaching legal reforms and Buddhist revivalist, feminist, and nationalist campaigns aimed at consigning minority Asians to subordinate status and regulating women’s conjugal and reproductive choices. Out of these efforts emerged understandings of religion, race, and nation that continue to vex Burma and its neighbors today.

Re-Examining the Five-Point Consensus and ASEAN’s Response to the Myanmar Crisis

Tang Siew Mun

ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2025

The Five-Point Consensus (5PC) encapsulates ASEAN’s response to the Myanmar crisis precipitated by the military’s seizure of power on 1 February 2021. As criticism about the effectiveness of ASEAN continue to mount, the current chair of the association has proposed the appointment of a “permanent” special envoy by extending its term beyond one year. In addition to revisiting its tenure, ASEAN should also consider providing the special envoy with the necessary political backing, adequate funding and efficient administrative support. More importantly, ASEAN needs to expand its mandate from an exclusive focus on conflict management to conflict resolution. The 5PC is by no means a perfect framework. It lacks a clear “end game” beyond the advocacy for dialogue. From a strategic perspective, ASEAN made few attempts to leverage on “carrots and sticks” and relied heavily on persuading a disinterested Myanmar leadership on the implementation of the 5PC.

Myanmar’s Uncharted Territories: Pitfalls and Prospects in Emergent Forms of Governance

Ardeth Thawnghmung & Gwen Robinson

ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2025

An escalation of violence in Myanmar has led to a significant loss of territories by the Myanmar junta and reconfigured the country’s political terrain. The territories can presently be characterized broadly into Junta-controlled areas with low resistance, junta-controlled areas with high resistance, active armed conflict areas, areas controlled by highly vulnerable non-state armed groups, areas controlled by non-state armed groups that are not as vulnerable, and border

areas sheltering internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees.

Each of these are evolving on a weekly or monthly basis, igniting both optimistic and pessimistic responses from Myanmar civilians and policy/scholar communities. Negative concerns originated from the proliferation of armed actors and a growing conflict among non-state armed actors and inter- and intra-communal hostilities, while positive responses are drawn from emerging bottom-up local governing practices.

Narrating Democracy in Myanmar: The Struggle Between Activists, Democratic Leaders and Aid Workers

Tamas Wells Routledge, 2025

This book analyses what Myanmar’s struggle for democracy has signified to Burmese activists and democratic leaders, and to their international allies. In doing so, it explores how understanding contested meanings of democracy helps make sense of the country’s tortuous path since Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy won historic elections in 2015. Using Burmese and English language sources, Narrating Democracy in Myanmar reveals how the country’s ongoing struggles for democracy exist not only in opposition to Burmese military elites, but also within networks of local activists and democratic leaders, and international aid workers.