The Inya Institute Quarterly Newsletter

Fall 2025

Almostfive years into the coup, the first phase of general elections planned for late December 2025 offers the junta further opportunities to strengthen ties with China and India by seeking broader support and backing from the two countries. It also explains all the counteroffensives currently being conducted in strategic locations across the country that predominantly rely on fighter jet bombings and drone attacks, with the civilian population — as usual — paying a heavy toll. In recent weeks, ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) and people defence forces (PDFs) have had to retreat from some places. But overall they have held steady.

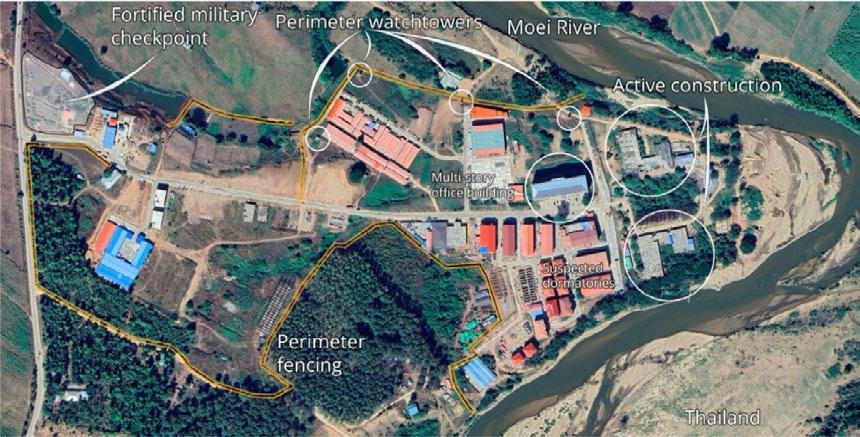

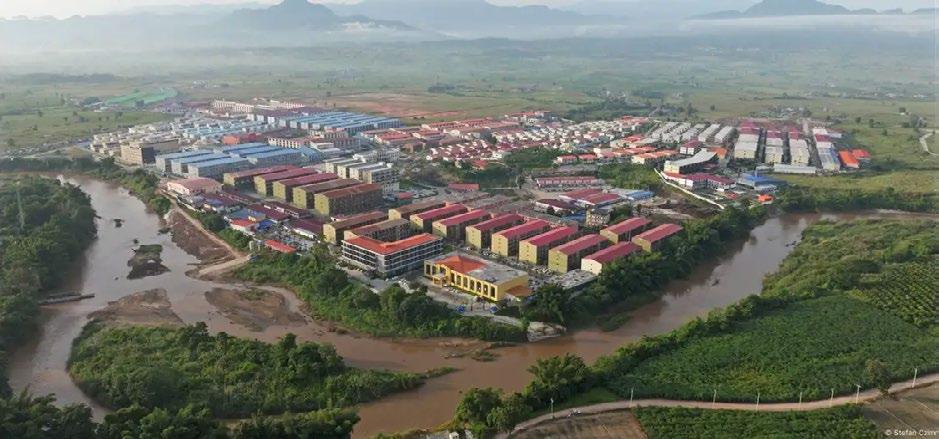

In this issue, Amanda tells us that most young people in her small town of Mong Pawn (Shan State) have chosen to work at online scam centers built by Chinese criminal syndicates along the Thai–Myanmar border with the support of border guard forces. Much of the media coverage about these online scam centers focuses on the myriad of jobseekers from around the world that are tricked into going to Thailand with the promise of high-paying jobs. Once there, they are forced to defraud clients in North America or Europe. By contrast, our interview with Amanda on p. 3 also shows the reality of hordes of young people in Myanmar accepting this kind of work due to the lack of education and economic opportunities in Shan State and the entire country.

www.inyainstitute.org

In the final contribution to a three-part series on the impact of USAID funding cuts for Rohingya communities in the refugee camps of Bangladesh, Mohammed Mirza Nu covers the latest developments that he and his community have been experiencing over the past three months. In recent weeks, various conferences and funding appeals have highlighted the emergence of a catastrophic situation. Mirza Nu tells us p. 6 what this situation is now like on the ground.

The Inya Institute is delighted to welcome three new interns: Thet Hnin Sint, Htoo Thet Khit, and Zeyar Ye Yint, who started their tenure in August and will work with us until the end of January 2026. The interns are investigating how searching for a job in a very crippled market is further complicated by the mismatch between the skills of jobseekers and employers’ expectation and requirements. We hope their findings will help us inform our programming for the short-term training course the institute regularly offers. More about our three new interns on p. 13!

Lastly, we are happy to share the good news that the institute was awarded a second grant from UCLA’s Modern Endangered Archives Program for the digitization and cataloging of monastic collections in the Greater Shan Country. More on this on p. 12!

The Inya Institute team in Yangon

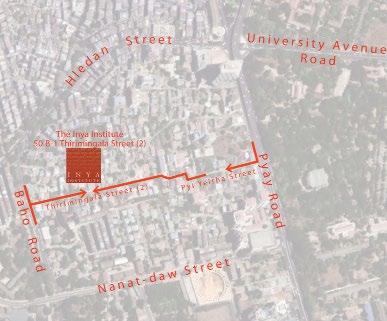

Address in Myanmar:

50 B-1 Thirimingala Street (2)

8th Ward

Kamayut Township Yangon, Myanmar

+95(0)17537884

Address in the U.S.: c/o Center for Burma Studies

101 Pottenger House

520 College View Court

Northern Illinois University

DeKalb, IL 60115 USA

+1 815-753-0512

Director of Publication:

Dr. François Tainturier

Administrative Assistant: Thin Thin Thar

Digital Resources and Info Assistant: Shun Lai Pyae Sone

Education and Training Manager: Pyae Phyoe Myint

U.S. Liaison Officer: Carmin Berchiolly

Contact us: contact@inyainstitute.org

Visit us on Facebook: facebook.com/inyainstitute.org

Library: It currently holds a little more than 900 titles and offers free access to scholarly works on Myanmar Studies published overseas that are not readily available in the country. It also has original works published on neighboring Southeast Asian countries and textbooks on various fields of social sciences and humanities. Optic fiber wifi connection is also provided without any charge.

Library digital catalog: Access here.

Working hours: 9am–5pm (Mon–Fri)

Digital archive: It features objects, manuscripts, books, paintings, and photographs identified, preserved, and digitized during research projects undertaken by the institute throughout Myanmar and its diverse states and regions. The collections featured here reflect the country’s religious, cultural, and ethnic diversity and the various time periods covered by the institute’s projects developed in collaboration with local partners.

Digital archive: Access here

The Inya Institute is a member center of the Council of American Research Centers (CAORC). It is funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act (2024-2028).

Institutional Members

Center for Burma Studies

Center for Asian Research

Southeast Asia Program

Northern Illinois University Arizon State University Cornell University

Center for Southeast Asian Studies Carolina Asia Center York Asia Center for Reseearch

Northern Illinois University University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill York University

Academic Board

Maxime Boutry, Centre Asie du Sud-Est, Paris

Jane Ferguson, Australian National University

Lilian Handlin, Harvard University

Bod Hudson, Sydney University

Mathias Jenny, Chiang Mai University

Ni Ni Khet, University Paris 1-Sorbonne

Alexey Kirichenko, Moscow State University

Christian Lammerts, Rutgers University

Mandy Sadan, University of Warwick

San San Hnin Tun, INALCO, Paris

Juliane Schober, Arizona State University

Nicola Tannebaum, Lehigh University (retd)

Alicia Turner, York University, Toronto

U Thaw Kaung, Yangon Universities’ Central Library (retd)

Board of Directors

President: Catherine Raymond (Northern Illinois University)(retd)

Treasurer: Alicia Turner (York University, Toronto)

Secretary: François Tainturier

Jane Ferguson (Australian National University)

Lilian Handlin (Harvard University)

Nicola Tannenbaum (Lehigh University)(retd)

Thamora Fishel (Cornell University)

Aurore Candier (Northern Illinois University)

Online Scam Industry and its Temptations: A Perspective from within Myanmar

Amanda, the pseudonym of a young Shan woman, is a former participant in one of our training courses on manuscript documentation and preservation. A native from Mong Pawn, Shan State, she shares insights into how the online scam industry and its illegal compounds built along the Thai –Myanmar border are attracting hordes of young people who knowingly accept the working conditions and the nature and purpose of their jobs. Her account complements the recent media coverage of the industry by Reuters or the ASPI report , among other sources, which document the industry’s booming expansion and feature testimonies from individuals who escaped after being trapped and tortured in these compounds for months.

Inya: Amanda, can you describe your village including its geography and demography, economy, education, etc., and what are the typical job opportunities for young people?

Amanda: My village is Mong Pawn, Southern Shan State. It is surrounded by mountains and farmlands, and the majority of people work in agriculture such as rice, corn, and seasonal crops. The population is small, and most families know each other. Education is limited—basic schools are available but many students cannot continue higher education due to financial problems. The local economy mainly relies on farming and small trading. Typical job opportunities for young people are farming, small trading, construction, teaching at local schools, or migrating to Thailand for labor jobs.

Inya: When was the first time that you heard about people in your village being involved in online operations along the Thai-Myanmar border?

Amanda: I first heard about people being involved around 2020–2021.

Inya: When did those operations start recruiting people in your village and how?

Amanda: Recruitment started around the same time, in 2021. Agents came through personal networks, relatives, and friends to introduce the jobs.

Inya: At that time, what was the knowledge of villagers about these online operations?

Amanda: Villagers had very little knowledge. Most thought it was just online office work like customer service or typing jobs.

Inya: At that time, how did the recruitment process work?

Amanda: The process was simple: agents contacted youths directly or through family members and offered jobs with the promise of high pay, free housing, and meals.

Inya: How did the agents persuade people (especially youths) to work there? Were they deceived by the agents who convinced them with a well-paid job or a certain type of skills needed? If so, which skills were looked for by these agents?

Amanda: Agents persuaded people by promising high salaries rangin from 300,000 to 600,000 MMK per month [$75-$150 at the current market rate], free housing, and food. They often said no skills were needed, but having some computer knowledge or Chinese/English skills was a bonus. Many youths were deceived because they thought it was a legal and safe job.

Inya: Early on, do you remember how many people were recruited?

Amanda: At first, only a small number— maybe 3–4 youths for every 10 people.

Inya: Did they voluntarily agree to work there or were people forced to work there?

Amanda: Most agreed voluntarily, but later some were pressured by their family or friends.

Inya: Which kinds of job positions did they offer?

Amanda: They offered positions like

online customer service, chatting/typing operators, marketing staff, and game promotion staff.

Inya: What were the Myanmar-language terms used within your community to designate these online operations early on?

Amanda: At first, people called it ‘online kaung sa yar’ (အွန်လိုင်းေကာင်းစာယာ) or ‘online games’. Later, the word ‘kyar phyant’ (ကျားြဖန် ) became common.

Inya: How did they introduce the job and did the agents explain the job descriptions at that time?

Amanda: Agents introduced these jobs as easy online work. The job description was vague and agents mostly highlighted the salary and benefits rather than the real duties.

Inya: When did you first hear about the word ‘kyar phyant’ and in what context?

Amanda: I first heard the word ‘kyar phyant’ in 2021, when people started saying that these jobs were connected to scams.

Inya: When did you realize kyar phyant were illegal and fraudulent activities run by the Chinese mafia?

Amanda: By 2022, it became clear through news and word of mouth that these operations were illegal and linked to Chinese mafia groups.

Inya: When has kyar phyant online scamming become more and more popular among young people in your town? How long has it been now and explain us why and how this has happened?

Amanda: It became more popular between 2021–2022 when the local economy worsened. Young people saw it as easy money compared to farming or migrating abroad.

Inya: Were there any changes in the recruitment process which explain why it has become more and more popular?

Amanda: Yes. Agents started offering higher salaries, used social media, and made the jobs look more professional.

Inya: Are they still offering the same amount of salary to workers as before?

Amanda: Yes, but sometimes slightly higher to attract more people.

Inya: What would you say are the main waves of recruitment process in Mong Pawn since you first heard about kyar phyant online scamming?

Amanda: During the years 2020–2021, the recruitment was small with only a few joining. In 2022, recruitment increased as the economy worsened. During 2023–2024, a large wave occurred as a majority of young people was targeted.

Inya: Can you describe the increased number approximately?

Amanda: In 2021, about 3–4 out of 10 young people worked there. By 2023–2024, it grew to 6–7 out of 10. These are rough estimates.

Inya: Do you have any experience of being persuaded by the agents or anyone else in your town? If yes, how did they approach you? What are the incentives/ offers they gave to you? If you or your

friends did not accept the offer, what made you or your friends refuse working there?

Amanda: Yes, I was approached. They offered high salary, housing, and meals. I refused because I was suspicious about the legality of these activities and worried about my safety. Some friends refused because their families discouraged them.

Inya: After kyar phyant became popular among the young people of your town, is the number of people who are willing to work there accelerating? If yes, what type of benefits makes them choose to work in kyar phyant operations?

Amanda: Yes, the number has increased. Most chose it for financial benefits—quick income, free housing, and avoiding hard farm labor.

Inya: After kyar phyant became popular among the young people of your town, have you heard about any youths or people being forced to work there by family members or friends due to the perceived benefits mentioned above? If yes, why and how were they forced?

Amanda: Yes. Some families pressured their children to join because of the attractive salary and lack of other job opportunities.

Inya: From the first time you heard about it up to now, have you heard about people in your town being trafficked into working for kyar phyant online scamming without their consent? If so, is the number of such cases increasing or decreasing? If yes, how does it happen?

Amanda: Yes, I heard about some being trafficked or deceived. The number has slightly increased. Usually, they were promised one type of job but ended up trapped in scam operations.

Inya: Is there anyone in your village who escaped from that work space? If yes, why and how did they try to escape?

Amanda: Yes, some escaped because they found it dangerous or stressful. Some ran away secretly; others left with the help of family or contacts.

Inya: Do you know if those who go and work there voluntarily have a chance to come back? If yes, are they allowed to share their work experience?

Amanda: Yes, some come back voluntarily, but they usually avoid sharing details because of fear or shame.

Inya: Do they also persuade the fellow villagers to work there?

Amanda: Yes, many who worked there tried to persuade their friends or relatives to join.

Inya: Do you hear or know whether there is any social pressure or stigma back in your town around individuals who are working/have been working in these scam operations? Are there any differences between the younger and elder segments of the population in the way they perceive young people working in these scam operations?

Amanda: Yes, there is stigma. Elders see it as shameful and dangerous. Young people are more accepting since they focus on money.

Inya: How does the people’s knowledge about kyar phyant change after it has become popular among the young people in your town?

Amanda: One category of people are like some of my neighbors who are happy to allow family members to work there because of the money. Another category is people who refuse because they see it as illegal and unsafe.

Inya: Are you still in contact with people who now work in the scam operations? If yes, can you/they contact them? How? Do they share the kind of challenges they have been facing including mental health?

Amanda: Yes, I am still in contact with some friends. We communicate through phone and social media. They sometimes share that they face stress, fear, and long working hours.

Inya: Until now, what facts have made you still reluctant to accept to work in these operations like other people in your town even though this work has become prevalent in your community?

Amanda: Because I know it is illegal, unsafe, and harmful to long-term life.

Inya: Are there any youths like you in your town not going to work at kyar Phyant online scamming? How many?

Amanda: Yes, maybe about 3 out of 10 youths still refuse to join.

Inya: Did you try to discourage any friends or family relatives from joining? How did they respond?

Amanda: Yes, I tried. Some listened, but others ignored because they wanted fast money.

Inya: What are the negative or positive impacts on the villagers’ livelihood, economy, security, or inherited career of the family?

Amanda: One positive aspect is that it may improve the finances of families, at least temporarily. Negative aspects include the dependence on illegal income, decline of farming/traditional work, increased insecurity, and broken career paths for youths.

Inya: Do you think that the booming of this online scam industry relates to the economic conditions of your town and area somehow in the past few years? To what extent does it influence the local economy and in what ways?

Amanda: Yes, it is directly connected. Because farming activities and migration-related works are not profitable enough, online scamming became attractive. It strongly influences the local economy—many families now depend on money from kyar phyant rather than traditional work.

Life in Rohingya Refugee Camps Seven Months into the USAID Funding Cuts

Mohammed Mirza Nu is a Rohingya researcher, human rights defender, interpreter, and documentary videographer with experience in humanitarian, qualitative, quantitative, and ethnographic research in the Rohingya refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. He has contributed to various projects related to health systems, cross-border trade, and refugee experiences. He has also facilitated participatory workshops and supported effective communication between researchers and communities. His work focuses on amplifying marginalized voices and enhancing the quality of humanitarian responses through research and interpretation.

Mirza Nu’s testimony is the final contribution to a three-part series documenting the consequences of the USAID funding cuts for Rohingya communities in Bangladesh’ refugee camps. Recent international mobilization—seen through conferences in Bangladesh and at the UN General Assembly—made it possible to raise some emergency funding.

When USAID-funded NGO jobs were terminated, some volunteers engaged in informal camp-based small business such as general shops, tea stalls, bakeries, etc. Additionally, some volunteers engaged in limited projects, short-term jobs in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH), infrastructure and research. While working outside the camp is strictly restricted and risky, a few NGO workers work in private schools to support their family even though the salary is meagre. Among those who lost their jobs, a few went as far as doing online gambling with their

smartphones but, in most cases, they were left in high debt and much stress.

Rising informality of jobs

The Bangladesh government has established strict controls around the Rohingya refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, including barbed-wire fences and checkpoints. Rohingya refugees are legally restricted to the camps and cannot move freely or take formal jobs outside, as they do not have Bangladeshi IDs or work permits. In

practice, however, some refugees do slip out to earn money through informal and difficult labor. The kinds of work they take are usually low-skilled and physically demanding, such as construction, farming, fishing, processing dry fish, or helping in small shops and households. Because they lack legal status, they are paid less than Bangladeshi workers—often just a few hundred taka a day [100 BDT = 0.82 USD]. These jobs require no official documents, but working outside the camps carries risks: police may detain them, businesses can be shut down, and refugees are vulnerable to exploitation or wage theft since they have no legal protection.

The same is true for overseas work opportunities available outside Bangladesh. Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are not legally eligible to be recruited by bluecollar agencies because they don't have citizenship, work permits, and travel documents. This means they cannot formally access overseas labor migration channels that recruit workers for construction, domestic work, or industrial jobs abroad.

Because of the aid cuts and loss of NGO-funded jobs, many Rohingya families have turned to opening small private shops inside the camps as a survival strategy. The road stalls typically include everyday goods like tea, snacks, vegetables, groceries, or phone credit, and some families run tailoring services or barber

shops from their shelters. These are some of the few ways people can try to earn cash now that formal volunteer or cashfor-work opportunities are shrinking. However, these shops are informal and, in principle, not allowed under camp regulations. Camp authorities sometimes remove shops, confiscate goods, or fine shop owners, which makes the business risky. Despite that, families continue to open them because they have few alternatives. Internal gang groups often loot the shops in the camp.

From July to September 2025, there has been an increase in informal market activity. In many blocks, it's common to see a row of several new stalls or grocery corners that weren't there earlier this year. In my area, a dozen new shops have opened in 10 blocks, with families relying on them heavily to cope with reduced rations and lost jobs.

Since USAID funding cuts, refugee families have had to adopt tougher coping mechanisms to survive the growing hardship in the camps. Child labor has become more visible, with children helping in small stalls, doing odd jobs inside the camp, or even doing informal day labor outside. Child labor has become more widespread in the camp in the past few months. Many children left their schools, madrashs and got engaged in informal labour. My classmate in Grade 11 has now stopped school due to financial problems. Early marriage has decreased now.

Rohingya girls have been offered training in home-based projects such as poultry farming, crop cultivation, sewing, mushroom production, and similar trades through vocational education called Competency-Based Learning Materials (CBLM). While the training helps develop useful skills, most girls are not able to turn those skills into steady income. Limited access to markets, weak raw materials available, not having a suitable environment and restriction on working outside the camp, all prevent them from turning these trades into reliable livelihoods. Some girls do smallscale tailoring from home for neighbors, or sell soap, eggs, or vegetables informally to neighbors, but the earnings are minimal.

In these three months (July-September 2025), WFP has been providing $12 per person per month. When USAID dropped its foreign funding, we were provided with $6 per person per month. However, following a letter of Chief Advisor Dr. Muhammad Yunus to the

President of the United States, the US supported some millions.

Many of the Rohingya people who live in the US, Canada, Turkiye, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, can give a little money to their family or relatives living in the Bangladesh camps. However, Rohingya families in the camps usually experience challenges in receiving money from their overseas relatives as they have no access to registered financial transactions. Rohingya families often have to deal with some local host community members for that kind of transfer.

Human trafficking, gambling, drug dealing and other illegal activities have been experienced by displaced people in the camp, from the very beginning to the current situation. Documented cases include not only forced labor and sexual exploitation within the camps but also young Rohingya girls being trafficked abroad, particularly to countries like Malaysia, where they are pushed into forced marriage or other exploitative situations. A lot of young women fled the camp to marry in Malaysia. While traveling illegally to Malaysia, many girls are subject to sexual abuse and hunger. One big issue is kidnapping and the ransom money demanded in return, which, if not answered, may lead to severe abuse or even killing. Cases of kidnapping seem to have slightly declined in my camp compared to earlier times. But there's a risk of worsening when food or employment become scarce.

In the camp during these days of economic hardship, many people are thinking about their future. When they discuss about their homeland, Arakan,

they are aware that there is a second wave of genocide ongoing on the remaining Rohingya innocent civilians by Arakan Army (AA) after [what was earlier perpetrated by] the Myanmar military. They cannot find a way to find peace. In my neighborhood, a lot of people describe the Arakan Army as a threat to their life. A lot of people worry about being caught between armed groups and the military, or facing new discrimination. The risks of return are severe: AA and the Myanmar military forcibly recruited Rohingya youths and pushed them to the frontline in fighting and also placed restrictions on movement for Rohingya people. Returnees also face the danger of statelessness, as they still lack citizenship and legal protection in Myanmar. For most people, they are dying to return to their own home in Arakan to rebuild their lives, but, going back without dignified repatriation reflects desperation since returning now would likely expose them to another cycle of violence and persecution.

Critical shortages in medicine and reduced health care provision

The World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations-related health agencies, and other international health partners are still active. Their programs focus on basic primary healthcare, vaccination campaigns, nutrition, and emergency referrals. Still, children and elderly people have been disproportionately affected by the medicine shortage following the USAID cuts, especially those with chronic illnesses, in need of nutrition supple-

Pic. 2: A Rohingya old man selling vegetables near his shelter.

ments, and suffering from common infections.

We have health posts and primary health care centres around the camps. Now, at the end of September 2025, for general conditions and emergency support and NCD (Non-communicable Diseases) like hypertension, diabetes, diarrhea, eye problems, children health issues, heart and blood related disorders, services to the Rohingya community have been provided by various NGOs in collaboration with INGOs, UN Agencies and government health sector in the camp. But, when going to take treatment in these health facilities, people need to stand in long queues for a long time due to the huge number of patients. And access to actual treatments totally depends on funding. For severe health conditions like kidney stones, surgery, and other expensive and intensive healthcare support, access to treatment is even more limited.

The Health, Education, and Population Program for All (HEPPA) is still supporting pregnant women in some parts of the camp. It may provide three kinds of services: health, education and awareness. These mobile health clinics and outreach programs run by local NGOs and international partners have stepped in to partially fill the gap and typically provide basic consultations, maternal and child healthcare, limited vaccination services, and health awareness sessions, and distribution of hygiene kits. ANC and PNC (Antenatal and Postnatal Care) are operated in the camp by health organizations. But the main problem is the lack of skills among block-based health workers. Maternal care programs have been still operating in the Rohingya

camps during the past three months, even with reduced funding. Agencies like WHO, UNICEF, and public health NGO partners continue to run sexual and reproductive health services, including antenatal checkups, safe delivery by trained midwives, and emergency referrals. These services, however, are limited compared to the needs, but it is fortunate that they have not stopped completely. That said, gaps do exist. When women cannot reach clinics—because of distance, security, or lack of transport—they may resort to delivering their babies with assistance from traditional birth attendants or lay-women. These untrained helpers often lack sterile equipment and property skills, which makes deliveries far riskier. Such unsafe births increase the chances of complications and dangers for the newborns.

Access to medicines for chronic conditions has worsened since the funding cuts of early 2025. Over the past three months, from July to September, patients with severe illnesses have been able to see doctors at camp health posts, but they often leave without receiving the necessary medicines because stocks are so limited. To take treatment, families are turning to informal strategies. Some collect money from neighbors or relatives to buy drugs from local Bangladeshi pharmacies. There are also a few people obtaining drugs through black-market channels and other methods which are ultimately expensive, risky and sometimes involve counterfeit medicines. In more precarious situations, patients may turn to traditional remedies or homebased treatment. The lack of consistent medical monitoring increases the risk

of complications such as heart attacks, strokes, or diabetic crises.

As of late September 2025, most private clinics in the Rohingya camps remain closed, and the situation has not improved since mid-year. Refugees in need of urgent medical attention now rely mainly on government facilities and NGO health posts still operating inside the camps. These centers provide essential and emergency care but are often overcrowded and underfunded, with limited supplies and staff.

In the past three months, there have been initiatives in the camps geared toward training Rohingya volunteers and community health workers to help maintain healthcare services amid clinic closures and funding cuts. These programs focus on filling gaps in basic health education, maternal and child health, hygiene promotion, first aid, disease prevention, and early identification of common illnesses. The priorities of these initiatives are to ensure essential health services continue despite reduced formal facilities, with emphasis on maternal and child care, vaccinations, hygiene awareness, basic emergency response, and community health education. To support these priorities, a caregiving course is now offered in the camp for Rohingya youths.

Closure of shools and digital learning hampered

Rohingya children go to both religious schools and community schools during daytime. Children usually start the day with religious classes in the early morn-

Pic. 3: Rohingya workers in the early morning

ing, where they learn Quran recitation, Islamic studies, and basic moral lessons. Later in the morning or afternoon or evening, some of them attend community schools where they study subject matters following the Myanmar School Curriculum introduced in 2022-23. Depending on their interests, Rohingya youths may want to focus more on religious or community schooling. Religious education is based on a traditional Islamic curriculum focused on Quran, fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), Arabic, and moral lessons, taught by local imams in maktabs (elementary schools) and madrasas (secondary schools). Community schools use the Myanmar New Curriculum that include subjects like Myanmar, English, Mathematics, Social Studies, and Life Skills (primary level); Myanmar, English, Mathematics, Science, Geography and History (secondary level); and Myanmar, English, Mathematics, Chemistry, Physics, Biology (high school level).

Religious schools generally run six days a week as Friday is a holiday. Community schools open every day, early morning and early evening. Community learning centers in the Rohingya camps operating in the camp rely on Myanmar government curriculum. The rollout of the Myanmar curriculum began in early 2022 as a pilot program, starting with primary and secondary levels. By 2023-2025, it expanded gradually and as of 2025, it covers more grades in various centers. Almost every learning center follows that curriculum. However, from February 2025, suddenly all learning centers closed and all the host community teachers were suspended due to funding cuts. These centers were run by NGOs and UN Agencies, particularly UNICEF in collaboration with partner organizations, under the oversight of the Bangladesh Education Sector. Rohingya teachers, often trained by NGOs, deliver the classes. Since February 2025, the learning centers have been closed due to funding cuts in every part of the camp.

For post-secondary education, some Rohingya youths are engaging in online training and courses run by foreign universities and international organizations. In my observation, I see no new opportunity offered to Rohingya students to study abroad. However, there is an expectation that the Japanese government will take some Rohingya youths to Japan through a labor pathway program this year. When an announcement about scholarships or overseas study is made, it is often shared with only a

small circle of students and families. Knowledge of opportunities is not widely circulated across the camps, and many students never hear about them. For most Rohingya youth, the chance to study abroad or higher education remains a distant aspiration, as current education efforts are focused mainly on continuing basic community learning centers rather than pathways to higher education.

BRAC University is stepping up its efforts to offer online education programs like Refugee Higher Education Access Program (RhEAP) to Rohingya people. They are working with international organizations and universities to offer quality education for Rohingya students. To enroll in the online international program, a Rohingya student should have passed the matriculation, and completed the Language, Images and Analytical Thinking (LIT) program. BRAC University is doing its best to offer opportunities to Rohingya students.

UNICEF recently terminated over 1,000 host [Bangladeshi] teachers due to funding shortages. In response, the affected teachers protested, demanding reinstatement and warning that they would prevent NGO workers from carrying out their duties if their jobs were not restored. They also called for all education programs to be suspended until UNICEF rehired them. Despite these demands, other education providers continued their activities quietly, as no legal order had been issued. During this period, some protesting teachers visited a Refugee Studies Unit (RSU) operated by BRAC University field office in Kutupalong. In the Refugee Studies Unit, every student can get enough resources for their learning, digital tools, access to the internet, and a pleasant learning compound. During their visit, the teachers discovered staff and Rohingya refugee students engaged in learning activities. Local media representatives then confronted the Rohingya students, asking them inappropriate and unethical questions, and later published a viral news story. The reports accused BRAC University of taking Rohingya students outside the camps without Camp-in-Charge (CiC) approval and of providing them unauthorized education. In response, BRAC University decided to relocate its learning center inside the camps. However, the new locations are in remote areas without access to electricity or Wi-Fi, creating significant challenges for effective learning.

While pursuing educational opportunities is not easy, other opportunities are also not very accessible. Freelance jobs like content creation, video editing, or graphic design jobs do not provide a steady income especially since internet access is poor, electricity is highly restricted, and very few Rohingya people have the necessary equipment, training, and language skills to engage in online freelance work. While many Rohingya people have knowledge about how social media work, these cannot be considered as a source of income. These opportunities are only available for the most skilled individuals. Most refugees rely on informal camp-based income options, such as opening small grocery or tea stalls, tailoring or sewing from home, selling vegetables, doing handicraft and tutoring.

For Rohingya girls, the challenges are even bigger. They try to enroll in online courses for education, career, and digital skills. But challenges are significant, especially because of the poor internet connection or quality of digital devices used for online classes. Some girls may want to work with social media for some income. But no family will help them as families fear the exposure of their girls on social media. While working with social media, most content creators can't earn any income. Only those who have reasonable access and persevere may eventually earn some income after some time. However, it is not clear what the benefit is. Many consider that such activities may lead to a loss of grace and honor.

As I live in the camp, I see my future slipping further away each day as the situation continues to deteriorate. Yet, despite these challenges, I still hold on to hope—hope of one day returning to my homeland with safety, dignity, and rights, or of being resettled to a third country where I can rebuild my life. Living my entire life in the camp without opportunities or a future is not what I dreamed for myself or my family. Everyone deserves freedom, dignity, and the chance to live a meaningful life, and my greatest expectation is to secure safety, freedom, and a future of dignity for myself and my loved ones.

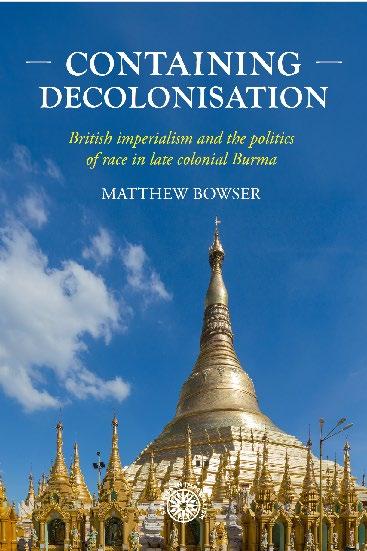

New Book

Containing Decolonisation: British imperialism and the politics of race in late colonial Burm a

Matthew Bowser

I am excited to announce that my book, Containing decolonisation: British imperialism and the politics of race in late colonial Burma, has been published by Manchester University Press on 2 September 2025. The book was written with the support of the Inya Institute through the CAORC-Inya Fellowship for the Study of Myanmar in a Third Country, which I received in 2022, and in it, I work to reframe the politics of the late colonial period in Myanmar and how those politics relate to the struggles of the present-day.

The book emerges from two key questions: Did imperialism “end” at the moment of decolonisation or did it merely adapt to changing circumstances? And why has ethnonationalism become so

powerful in so many post-colonial states?

To answer these questions and to untangle the association between them, this work examines British imperialism in late colonial Burma and finds that the imperialists attempted to protect their strategic and economic interests by supporting ethnonationalism. It argues that, as the rise of a powerful Burmese nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s made it increasingly clear that formal colonialism in Burma would eventually end, British colonial officials in London and on-thespot formed a tacit preference for Burmese ethnonationalists in order to combat the more revolutionary trends within Burmese politics. The relationship between imperialists and ethnonationalists may at

first seem paradoxical: ethnonationalists, by definition, demand political independence. But formal rule was often the least of British imperialists’ concerns, a “burden” even. The far more important end was the preservation of the foothold of British capital and geo-strategic operations in the long term. The British ultimately failed to achieve this objective in Myanmar, but the attempt nevertheless left an unmistakable footprint on the post-colonial politics that followed.

The work makes two key interventions into academic literature. First, for studies of imperialism, it bridges the gap between works on colonial “divide-and-rule” policies and works on neo-colonial “Containment” policies during the Cold War. It provides a key case study for how imperialists – and authoritarian states in general – utilise ethnonationalist politics as a force of passive revolution, providing the aesthetics of revolution while preventing real social and economic transformation. Second, for studies of Myanmar, it identifies the origins of the racial regime that scapegoats Indians and Muslims as foreign invaders and exploiters, encapsulated in the racialised term “Kala.” The British supported and amplified the colonial-era political movement behind this regime, U Saw’s Myochit Party; this support continued up to and including Saw’s assassination of the revolutionary leader Aung San, therefore helping to cement Myochit’s politics in the post-colonial period. The present-day Rohingya genocide is a result of the persistence of this racial regime, first utilised by the British and then re-activated by the post-colonial military junta. Ultimately, this book presents a symbiotic relationship between imperialism, capitalism, and ethnonationalism.

Recent Activities

Curriculum Development Workshop in Bangkok: An Evaluation

As part of a partnership between the Inya Institute and four Myanmar Community Colleges (MCCs) — Level Up College (LUC), Pinnya Tagar College (PTC), Cherry Myay College (CMC), and Tounge La’yat College (TLYC) — the curriculum development enhancement workshop for Associate of Arts Degree and Bachelor of Arts, led by Prof. Claudia Mercado and co-faciliated by Carolina Huerta, was held at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok on July 7-9. Please see the brief report of the workshop in our Summer 2025 issue.

During the three-day workshop, the school representatives and teachers from the four MCCs engaged in structured planning activities focused on curriculum development, academic program design, enrollment systems, and leadership structures. Each workshop session was supported by a participant packet that included daily schedules, facilitation guides, curriculum planning templates, and curated resources to support implementation.

Prof. Mercado’s mentioned the following,

“We could create an Academic Catalog framework that includes course codes, degree requirements, core courses, general education, and

elective options. To further support the colleges, they produced a Community College Resource Manual that outlines best practices in academic scheduling, course sequencing, institutional governance, culturally responsive curriculum design, and student enrollment process. This project resulted in a strengthened sense of cross-institutional collaboration, clear curriculum pathways, and practical tools to support long term implementation. Most importantly, it fostered leadership development and systems thinking among participants, equipping them to drive sustainable change in their institutions and communities.”

The experiences and learning gained from this workshop will help all four college launch an Associate of Arts degree in 2026 and a Bachelor of Arts degree in 2028. PTA’s school representative remarked that,

“Many of the things we are trying to get done have been done at the workshop. [...] What we have done at the workshop is quite momentous and will help us move more quickly to the destination which is the 4 year BA program.”

LYC’s school representative added,

“It helps us decide what is relevant for the four-year plan and it makes us feel good about it. We were able to discuss it well and get agreement on it. With a concrete three-month plan, we can also easily monitor our activities .”

The Three-month Action Plan discussed during the last day of the workshop will help MCCs in the implementation of the next steps taken by each institution. The TLYC confirmed,

“For both the Presidents and Deans, it will be easier to emphasize and follow up the plans working with their own team and as the whole body of MCC. The Deans and Presidents are now working on the three-month Action Plan developing the course description with the support of the subject teachers and meeting other partner organizations for the new course added to the program.”

Overall, comments show how this action plan helps to guide all MCCs to proceed with their plan.

Cherry Myay College

Level Up College

Tounge La’yat EGG College

Pinnya Tagar College

School representatives and teachers from the four MCCs now see the clear picture of where they are and where they are heading to, and which parts of their work need further development after this three-day workshop. CMC and PTC school representatives mentioned,

“The most important thing is about the clear understanding on how the community development curriculum is designed and adjusted according to local context and available resources

while aligning with academic standards”, “I have gained more knowledge about community colleges, the pathways available, and the components of different parts of colleges. On top of that, the most significant thing I got from this workshop is the confidence and aptitude to continue developing my college.”

For the future workshop, the school representatives and teachers from MCCs

suggest different components to cover, such as syllabus development, discussion with the practitioner from the universities which offers courses for Curriculum Development (as a major or a minor subject), and Internal Accreditation System, and Administrative Operation System including monitoring and evaluation framework, and teacher capacity building trainings.

Our thanks go to Prof. Mercado and Carolina for their expertise and participation in this initiative!

Pic. 1: Workshop participants at lunch time

Award

UCLA MEAP awards the institute a 2 nd grant for the digitization and cataloguing of monastic collections in the Greater Shan country!

Following a first award from UCLA’s Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP), the institute is thrilled to announce a second one from the same program. The first award supported an extensive survey of manuscript collections conducted in 2022-2023 across rural settings in Southern and Eastern Shan State and Mae Hong Son Province that resulting in the identification of six collections in critical need for digitization at this time of crisis in Myanmar. This second award will support the actual digitization of these collections over the December 2025-August 2027 period.

The scope and location of the survey was designed to complement the work done by other institutions like the Shan State Buddhist University (SSBU) in Taung-gyi (Shan State, Myanmar) and the Chiang Mai Rajabhat University (CMRU) in Thailand. Their work has mostly

focused on monasteries in urban settings where manuscript collections usually hold a larger number of manuscripts but are typically not under threat as custodians are aware of the collection’s significance and have the capacity to maintain the collection’s integrity.

The decision to focus on monastic collections in rural settings was also made in a context of heightened tensions in the Hopong and Hsihseng townships (Taunggyi area) where the Myanmar army and ethnic armed groups fought one another from October 2023 to July 2024.

The proposed digitization and cataloguing of six manuscript collections will be led by the institute and Dr. Jotika Khuryearn, Librarian and Shan Scholar, SOAS Library, University of London. The project will be undertaken with partners in both Myanmar and Thailand. The partner in Myanmar is SSBU. Our two partners in

Thailand are the Tai Yai Studies Center in Mae Hong Son and the Lanna Studies Center (CMRU).

Before field work, a digitization workshop will be organized in Yangon in early 2026 and led by Dr. David Wharton, a digitization expert. The workshop will bring representatives of groups committed to the preservation of manuscripts or other types of ancient artifacts from their communities. We hope to bring 12 representatives from across the country and under the guidance of David train them on the digitzation process.

Upon completing our own work and making it available on the archive-inyainstitute.org website, the institute will hold a series of webinars which will present the digitization of manuscripts, its process and methods, the scope of the work, and guidelines on how to use the platform. Stay tuned for more updates!

New Interns

My name is Thet Hnin Sint. I am 25 years old and currently living in Yangon. In July 2025, I was selected for the EU Mobility Program Myanmar (EMPM) Scholarship in order to work as a Desk Research Intern for Today’s Job Market at the Inya Institute.

I am a fresh graduate of Bachelor of Arts in International Relations. Since 2021, I have been working in many community-advocated projects and organizations. My first community work was at No Hunger Zone as a Public Relations officer. After that I had the chance to take part in the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiatives (YSEALI) Regional Workshop focusing on Mental Wellness for Reduction of Drugs Use with ICUDDR and Mahidol University withv funding from the U.S. Embassy in Yangon. As a follow-up activity, I received a small grant to implement a project within Myanmar about Peer Education for Reduction of Drugs Use.

I was later selected to participate in the YSEALI Economic Summit in Cambodia where I presented my plan for a new project that also later selected for funding. The project named “Triple E Myanmar” for Embracing Entrepreneurship Empowerment for Myanmar local SMEs and budding entrepreneurs facilitated training workshops and local brands embracing campaigns.

As an English teacher for rural youths, I had a chance to attend the YSEALI Innovating International Higher Education Workshop in Hanoi, Vietnam, held at National Economic University (NEU) Vietnam.

I was also the Myanmar delegate for the ROK-Mekong Youth Group Workshop in Seoul, Korea, conducted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Korea and the Mekong Institute. In this workshop, me and my team members’ project proposal, “Empowering Mekong Green Entrepreneurs” got a firt runner-up winning prize. 2024 was a major year for me since I joined the YSEALI Academic Fellowship for “Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Empowerment” and its five week-long exchange program. I travelled to the University of Connecticut and learned there much about business venturing and policies in the U.S. The internship at the Inya Institute offers me a meaningful research experience and I hope to gain much learning by interning at the Inya

My name is Zeyar Ye Yint. I was a student at Yangon University of Economics until 2022. After the political changes, I joined the CDM, but I did not stop studying and learning. During the COVID period and the coup, I attended courses on economics and social studies. In 2023, I attended the Diploma in Public Policy program at Spring University Myanmar (SUM): this allowed me to gain much research experience. As my interest in research grew, I wanted to explore, discover, and share my findings with the public. This experience motivated me to continue further. For some time, I also lived along the Thai Myanmar border, where I witnessed the challenges in education experienced by children in Myanmar. While there, I served as a volunteer teacher in secondary education for three academic years. Opportunities often came to me and I gained my second research experience as a research assistant. During this time, I studied the education laws of the U.S. and Australia and contributed recommendations for Myanmar with the Center for Research Policy, Research, and Innovation (CRPI), Burmese—American Community Institute (BACI)

Currently, I am studying Law and aiming to pursue a Bachelor’s degree at a foreign university. At the same time, I have also joined the Inya Institute as an EMPM fellow intern to expand my interest in education issues. I consider my research experiences as milestones in my life. When the future is uncertain, conducting research offers me opportunities to test my abilities. Although most of the research I have conducted are only small contributions, I view them as something that represents my resilience and survival.

I am Htoo Htet Khit, 24 years old, originally from a small town in Myanmar, and now living in Yangon. Moving to the city to continue my studies was a big step and life was not easy. I had to adapt to living independently, managing limited resources, and navigating new challenges every day. These experiences taught me resilience, independence, and the value of perseverance.

After three years at Yangon University, I had to pause my studies due to the political situation in the country. Unsure of what to do next, I started volunteering in online education programs. Helping students learn and grow gave me a sense of purpose and showed me that education is about more than textbooks—it’s about inspiring confidence, hope, and opportunity.

Later, I began working in Yangon, gaining experience managing academic programs and supporting students and teachers. Through this work, I learned how important communication, guidance, and encouragement are in helping people reach their potential.

Now, I am excited to continue learning and developing my skills through this internship. My goal is to support young people, help them tackle challenges, and create opportunities for them to grow. I hope to contribute to making education more empowering, inclusive, and meaningful for every young person, no matter their background.

Journal of Burma Studies |

SPECIAL ISSUE NOW AVAILABLE HERE AND IN BURMESE HERE!

Volume 29, Number 1, 2025

Table of Contents

• Histories of Belonging and Identities (Re)Imagined

Hitomi Fujimura, Alicia Turner

• The Appropriation of U Ottama by Japanese Bunkajin in Wartime Propaganda

Maynadi Kyaw

• Intoxicated Men and Moral Women: How the Multireligious Moral Movements

Crafted Gender in Colonial Burma

Hitomi Fujimura

• The Emergence of Ethnic Politics in 1940s Myanmar: Karens and Thakin Historiography

Kazuto Ikeda

• Reconsidering the “Anti-Footwear Campaign” in Colonial Burma (1916–1920): A Struggle between Religious and Political Interpretations

Kei Nemoto

Center for Burma Studies

Northern Illinois University

Annual Membership

Membership of the Inya Institute is now available for Institutions as well as Individuals!

Despite Myanmar’s current multidimensional crisis, the Inya Institute continues to operate in Yangon providing educational and training opportunities to Myanmar students, supporting scholarship by Myanmar and International researchers in Myanmar and in third countries, and offering language learning opportunities for those interested in Myanmar’s linguistic diversity. It is also one of the few libraries currently open to the public in Yangon. Interconnectedness between Myanmar, the U.S., the Myanmar diaspora in the U.S. and elsewhere is more important than ever and the institute is keen to support this value as shown by the activities presented in this newsletter. You can be part of this so please consider becoming a member of the Inya Institute! Contact us at: contact@inyainstitute.org

I NSTITUTIONAL MEMBERSHIP

Any recognized academic or educational institution in the United States or Canada may become an Institutional Member of the institute. If a representative of an institutional member chooses to send a delegate to serve on the board of directors, he/she has an opportunity to shape the institute’s programs and activities.

Other benefits include: (1) Recognition of institutional member status in the institute’s quarterly newsletter; (2) Publishing of members’ scholarly events in the institute’s quarterly newsletter; (3) Invitation to join online events, including conferences and webinars, organized by the institute.

Annual institutional membership dues are $400.

I NDIVIDUAL MEMBERSHIP

Anyone may become an Individual Member of the institute, upon application and acceptance by the institute.

Benefits: (1) Inclusion in the institute’s listserv of those institutions and individuals receiving the quarterly’s newsletter; (2) Invitation to join online events, including conferences or webinars, organized by the institute; (3) Reduced fees for the language learning opportunities developed by the institute.

Annual individual membership dues are $25.

Upcoming Events On Myanmar

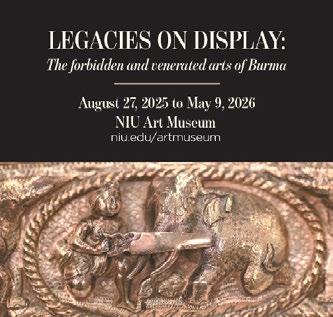

Legacies on Display: The forbidden and venerated arts of Burma

Location: NIU Art Museum, Northern Illinois University

Date: August 27, 2025 to May 9, 2026

Through a display of 19th to 21st century Burmese ivory, silver, textiles, and paintings, Legacies on Display reveals the complicated history of cultural and artistic objects and the lasting impact, intended or unintended, they leave behind as they travel from their point of origin to their final home in a museum, where a new history of public display and interpretation begins. Using the Burma Art Collection at NIU to explore these issues, this exhibition examines and questions the changing narratives that objects undergo as their life extends beyond a generation. From the once venerated elephant ivory carvings to the once forbidden modern protest paintings, Legacies on Display interrogates how meanings and interpretations are created, changed, and left behind as part of our human record. Legacies on Display invites viewers to reflect on the role of museums in the collecting, displaying, interpreting, and preserving of the past. How can we, as contemporary viewers, reconcile with artistic practices that are now understood to have had devastating effects on our past and present? How should we interpret artistic works that continue to hold true today in a world of continued political instability? And how can museums use these legacies as a catalyst for positive change? Through a diverse multimedia display, this exhibition demonstrates how our interpretation of art can simultaneously create and dismantle the legacies of the past. More info here

November Events

1. The Burmese Way to Socialist Realism: Comparing Burmese Remakes of Hollywood Movies from the Parliamentary Democracy and Socialist Periods

Location: Bunche Hall, Room 10383, UCLA and online

Date: November 10, 2025, 12:30-2:00

PM (PT)

Speaker: Jane Ferguson

Learning about, borrowing from, and copying established work to make a new product is a fundamental part of the creative industries. Motion pictures explicitly based on previous releases are called remakes. In an industry which sometimes privileges auteurship and creativity, yet has a business model that depends on mass appeal and established conventions, the production of the remake, and its possibilities for contestation present fruitful fodder in the exploration of the motion picture as art/spectacle/commodity. Burmese cinematic remakes of popular stories, novels as well as international films have been integral to the industry since its earliest years. Following a theoretical overview of the remake, its contestations, as well as its centrality to the motion picture business model, this talk will consider the meaning of the remake in Burma in the parliamentary democracy years (19481962). Then, turning to the socialist era (1962-1988) it will explore the remake as a cultural bellwether for Burmese engagement with global cinema. More info here

2. The Disguised Diversity of Myanmar’s Rohingya: Political Economy, State Formation, and Ethnogenesis in Arakan

Location: East-Southeast Asia Colloquium, University of Pennsylvania

Date: November 18, 2025, 5:157:00PM (ET)

Speaker: Elliott Prasse-Freeman

Most discourse on the Rohingya, a predominantly Muslim group indigenous to the western Myanmar state of Arakan, focuses on the genocidal violence they have suffered. An unfortunate corol-

lary to this imperative to speak about violence has been the flattening of all Rohingya into perfect replications of the body in pain. This obscures a great deal of diversity, which is, moreover, germane to understanding the violence itself. These tensions played out in the context of the country’s military state formation attempts. This protracted extrusion of Rohingya gave way to the mass violence of 2017’s expulsion of 800,000 Rohingya - a campaign that did not differentiate by class, and which, consequently, led to ethnogenetic consequences: Rohingya coming to identify as such, given their killability as tokens of that common type. More info here

December Events

1. How Ethnic Rebellion Begins: Theory and Evidence from Myanmar

Location: Room 555 Weiser Hall, University of Michigan

Date: December 5, 2025, 12:00-1:00 PM (CET)

Speaker: Jangai Jap

Since independence, most of the ethnic minority groups in Myanmar—though not all—have rebelled against the central government, making it home to the most simultaneous and longest ongoing armed conflict in the world. In this talk, Jangai Jap tracks the origins of armed ethnic organizations in Myanmar and argue that political exclusion—a primary grievance widely thought to motivate ethnic rebellion—played a rather minimal role in the onset of ethnic rebellions. Instead, what distinguishes ethnic groups in rebellion from other ethnic minority groups is the claim of having an ethnic “homeland” within Myanmar. Individuals from such ethnic groups form nascent armed groups, which are then fostered and supported by more established ethnic armed organizations. Jap illustrates this dynamic through the role of the Karen National Union and the Kachin Independence Organization in the proliferation of robust ethnic armed organizations in Myanmar. More info here.

New Books On Myanmar

The Palimpsest Constitution:

The Social Life of Constitutions in Myanmar

Melissa Crouch

Oxford University Press, 2025.

Since the mid-20th century, many former postcolonial states have engaged in multiple constitution-making exercises, with the turnover in written constitutions often due to coups or internal conflict. Conversely, people have resisted authoritarian rule through alternative constitution-making. The reality that most countries have had numerous official and unofficial constitutional texts begs the question: How do past constitutions matter in the present? This volume explores the social life of constitutions, or how past constitutions matter. Using the case of Myanmar, Crouch demonstrates that constitutions are a palimpsest of past texts, ideas, and practices, an accumulation of contested legacies. Through constitutional ethnography, she traces Myanmar’s modern constitutional history from the late colonial era through its postcolonial, socialist, and military regimes.

Arms Politics: Becoming and Being a Weapon in the Borderlands of Myanmar

Francesco Buscemi

Cornell University Press, 2025.

In Arms Politics, Francesco Buscemi tells the story of the ceasefire, disarmament, and rearmament of the Ta’ang movement in Myanmar’s Shan State through an analysis of the formation of the Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA). With a focus on the circulation of weapons through the post-1991 ceasefire, disarmament, and rearmament years, Buscemi explores how “becoming and being” an armed force leads to the “becoming and being” of a rebel polity.

Reproducing Revolution: Women’s Labor and the War in Kachinland

Jenny Hedström

Cornell University Press, 2025.

In Reproducing Revolution, Jenny Hedström explores the Kachin revolution in Myanmar from the perspective of female soldiers, female activists, and women displaced by the violence in northern Myanmar. Hedström argues that the household is an inherently gendered, militarized, and political space that impacts, and is in turn impacted by, the external conflict with which it coexists. In this context, women’s everyday labor—the gendered work of childcare, farming, fighting, and forging connections both across households and between the household and the army and the nation—is key to revolutionary survival. Hedström calls this labor militarized social reproduction, and in Reproducing Revolution she demonstrates that such labor is critical to the military effort, and that warfare itself is shaped through everyday domestic action.

The Milk Tea Alliance: Inside Asia’s Struggle Against Autocracy and Beijing

Jeffrey Wasserstrom

Columbia University Press, 2025.

Why are activists in Thailand, Hong Kong, and Burma willing to court danger to help one another? The political situations in Burma, Thailand, and Hong Kong are radically different. Only Burma is in a state of civil war. Only Hong Kong has changed in just a few years from a place with virtually no political prisoners to one with many. Only Thailand is a monarchy with lèsemajesté laws. Yet, many young activists and exiles from these regions feel that their struggles are connected. Historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom met dozens of dissidents. How do these activists, each facing their unique situations, find common ground and sustain one another? Wasserstrom traveled globally to interview members of this loosely constituted alliance, meeting some in Asia and others in exile, finding them united by democratic values, shared concerns over autocrats, and the rising influence of a common adversary—the Chinese Communist Party.