The Inya Institute Quarterly Newsletter

Spring 2023

Myanmar’s currently expanding civil war is bringing to the fore long-standing narratives about its borderlands, which now assume additional critical relevance. As you will read on pp. 3–7, Jangai Jap and Billie Thoidingjam Guarino, two of our CAORC-INYA fellows who hail from Kachin State and Manipur (Northeast India) respectively, reflect on these borderland issues following field work conducted during the summer of 2022 in Thailand for the former, and Northeast India for the latter. Both accounts tell of incredible hardship, acute precarity, but also tenacious resilience and relentless hope.

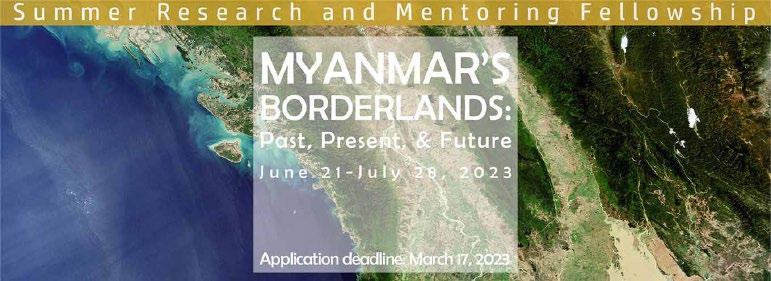

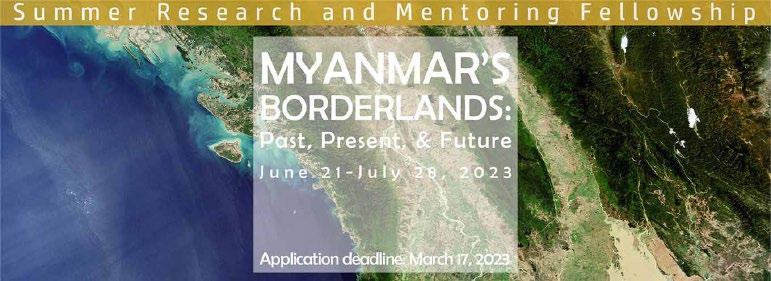

As we seek to contribute to the crucial conversation on Myanmar’s borderlands – their past, present, and future – the institute, together with partners in Myanmar and neighboring countries, will hold a “Summer Research & Mentoring Workshop Series” scheduled for June 26-July 28, 2023, and an international conference on these themes in mid-2024. The first event, the workshop series, will be led by a scholar specializing in borderland issues and will involve the participation of six to eight Myanmar junior researchers, interested in developing research papers on the topic. The second event, the conference, will offer this group of researchers an opportunity to present their final papers a year later to international

www.inyainstitute.org

and Myanmar peers. In the meantime, interim online workshops will help them develop their data collection and analysis, and oral presentation skills.

Also aligned with the need to advance our collective conservation about Myanmar’s borderlands and following last year’s success, our 2023 “Languages of Myanmar Course Series” will introduce learners to the fundamentals of Kachin, Karen, and Shan languages. With increased opportunity to learn languages spoken in the regions will come a greater understanding of the crucial role they have played and will continue to play in the country’s future.

In our Yangon office, we wish to bid farewell to Zin Nyi Nyi Zaw who joined our team as Digital Resource and Information Assistant two years ago at an extremely difficult time. We are very grateful for his work and wish him all the best in his new endeavors now that he and his family have relocated in Taunggyi. Aung Kyaw Phyo has taken over from Zin Nyi. Also new to our team is Pyae Phyo Myint, our Education and Training Manager. Read their profiles on pp. 11–12 and join us in welcoming them to our team!

In this issue Reflections from the Field 3 “Pondering over the State in Myanmar”

J. Jap Reflections from the Field 5 “Surviving Displacement and the Art of Storytelling in the Borderlands of Myanmar”

Insights 7 “A Review of Digital Collections of Shan Manuscripts”

Khur-Yearn News from our staff 11 Current Opportunities at Inya 13 Upcoming Opportunities at Inya 14 Upcoming Events in the U.S. and beyond 15 New Books on Myanmar 16

The Inya Institute Team in Yangon

by Dr.

by Dr. B. Guarino

by Dr. J.

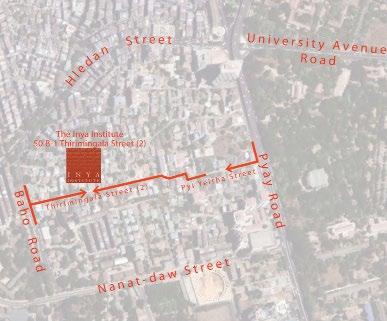

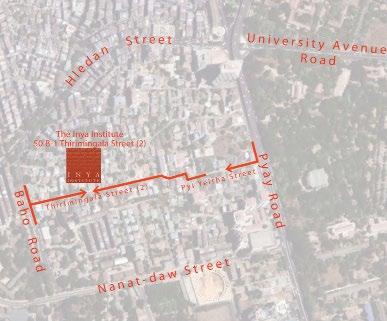

Address in Myanmar: 50 B-1 Thirimingala Street (2)

8th Ward

Kamayut Township Yangon, Myanmar +95(0)17537884

Address in the U.S.: c/o Center for Burma Studies

101 Pottenger House

520 College View Court

Northern Illinois University

DeKalb, IL 60115 USA

+1 815-753-0512

Director of Publication:

Dr. François Tainturier

Layout and Formatting:

Zin Nyi Nyi Zaw & Aung Kyaw Phyo

Administrative Assistant: Chai Mana

U.S. Liaison Officer: Carmin Berchiolly

Contact us: contact@inyainstitute.org

Visit us on Facebook: facebook.com/inyainstitute.org

Library: It currently holds a little more than 830 titles and offers free access to scholarly works on Myanmar Studies published overseas that are not readily available in the country. It also has original works published on neighboring Southeast Asian countries and textbooks on various fields of social sciences and humanities. Optic fiber wifi connection is also provided without any charge.

Library digital catalog: Access here.

Working hours: 9am-5pm (Mon-Fri)

Digital archive: It features objects, manuscripts, books, paintings, and photographs identified, preserved, and digitized during research projects undertaken by the institute throughout Myanmar and its diverse states and regions. The collections featured here reflect the country’s religious, cultural, and ethnic diversity and the various time periods covered by the institute’s projects developed in collaboration with local partners.

Digital archive: Access here

The Inya Institute is a member center of the Council of American Research Centers (CAORC). It is funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act (2020-2024).

Academic Board

Maxime Boutry, Centre Asie du Sud-Est, Paris

Jane Ferguson, Australian National University

Lilian Handlin, Harvard University

Bod Hudson, Sydney University

Mathias Jenny, Chiang Mai University

Ni Ni Khet, University Paris 1-Sorbonne

Alexey Kirichenko, Moscow State University

Christian Lammerts, Rutgers University

Mandy Sadan, University of Warwick

San San Hnin Tun, INALCO, Paris

Juliane Schober, Arizona State University

Nicola Tannebaum, Lehigh University (retd)

Alicia Turner, York University, Toronto

U Thaw Kaung, Yangon Universities’ Central Library (retd)

Board of Directors

President: Catherine Raymond (Northern Illinois University)

Treasurer: Alicia Turner (York University, Toronto)

Secretary: François Tainturier

Jane Ferguson (Australian National University)

Lilian Handlin (Harvard University)

Nicola Tannenbaum (Lehigh University)(retd)

Thamora Fishel (Cornell University)

Reflections from the Field

Pondering over the State in Myanmar

Jangai Jap, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Government at the University of Texas at Austin and a recipient of the 2022 CAORC-INYA Scholars Fellowship. She studies Comparative Politics with a focus on ethnic politics, nationalism, minority-state relations, and civil war with a regional focus on Burma/Myanmar. In her on-going book project, she examines mundane citizen-state encounters and their implications for ethnic minorities’ attachment to the state.

Conducting field research has never come naturally to me. I tend to drag my feet getting out to the field. I struggle to fill up my week with appointments. And I often find myself spending a significant portion of my time in the field dealing with non-research matters (e.g., tracking down delayed/lost luggage, sickness, etc.). But time and time again, being in the field never disappoints. I always (unexpectedly) meet people who are most generous with their time and have extraordinary conversations, providing new insight that could be gleaned only in the field.

While in the field in Myanmar during the summer of 2017, that extraordinaryconversation was with a civil servant. I was on a pre-dissertation research trip. My research interest then was ethnic minorities’ political representation. The return to electoral politics in 2010 made political representation of ethnic minorities possible, and I had hoped to better understand if and how political representation shapes ethnic minorities’ political behavior and attitudes. But my conversation with the civil servant sparked a new research avenue.

Our discussion was not a research interview. He was telling me about his day at the local government office, people he encountered, problems he helped solve, problems he could not solve, and so on. From our discussion I realized that people across Myanmar have routine, quotidian interactions with the Myanmar state via civil servants, and the state holds a near monopoly over administrative services ordinary citizens seek. People visit streetlevel bureaucracy to apply for NRC, passports and other government-issued identification documents, to register their

household members, to apply for building permit, to register ownership of a new plot of land and so on. These are mundane but arguably most tangible experiences with the state. What happen in these citizenstate encounters? And what are their implications for minority-state relations? These became the motivating questions for the new direction of my research.

After a year of conducting field research in Myanmar, I left Yangon in December 2019 for a brief holiday, intending to come back in the new year. However, due to the pandemic and the coup in 2021, I would not be able to conduct field research again until the summer of 2022 when I travelled to Thailand, with the generous support from the CAORC - INYA fellowship.

3

Figure 1: Survey implementation on the Chin Hills, Fall 2019

Figure 2: Highway to Mae Sot, Summer 2022

I arrived right when Southeast Asian countries were relaxing their Covid-19 protocols. Due to severe weather and other exceptional circumstances, I arrived in Chiang Mai twenty-four hours later than my original arrival time and without any luggage. My luggage would not arrive in Chiang Mai for another three weeks… when I was in Mae Sot.

My research objective in summer 2022 was to better understand what the “state” is like in the liberated areas, i.e., areas of Myanmar controlled by the ethnic revolutionary organizations (EROs). These areas are beyond the reaches of the Myanmar state, but we know there is political and social order in such areas in Myanmar and beyond (there is an extensive literature on “rebel governance” in social sciences.) We also know that there is extensive service provision, including healthcare and education, in the areas under the major EROs in Myanmar. Moreover, EROs also provide extensive judicial services. Even residents of government-controlled might approach the ERO authorities to settle land disputes, inheritance disagreements, personal status issues, and so on. At the same time, a major feature of the state is making the population and territory it governs legible.1 How do the leaders of these organizations think about their role as the de facto state in these areas? Beyond service provision, how do they administer the territories under their control?

During my fieldwork I was able to connect, in person, with key leaders in the major EROs as well as with individuals who have lived in the liberated areas. Those I met in person would then virtually connect me to their friends and colleagues living in the liberated areas. I learned about what counts as forms of identification, title to land/property ownership, and other forms of official documentation. It became clear very quickly that the de facto state in the liberated areas is much more informal and personal than the state I was used to studying. Given that the EROs are armed revolutionary organizations, this is not surprising—setting up bureaucratized public administration structure is unlikely to be a priority for them.

Residents of the government-controlled area routinely visit local government offices to obtain a National Registration Card, to register their household members, get documentation of their property ownership and so on. But such official documentations seem almost unnecessary in the liberated areas. If you wanted to buy a piece of land, you just write up the terms of agreement on an A4 paper and ask the village chief and a witness to sign the paper (in addition to you and your transacting counterpart). It seems unnecessary to register this transaction to the authority governing the area. Here the de facto state does not appear to have a final say on who you are, who you are related to or what you own. In fact, the de facto state seems uninterested in doing so. Not needing to engage in routinized citizen-state encounters feels liberating indeed, but I constantly wondered if the de facto state should behave more like the official state (specifically, in terms of public administration).

Visiting local government offices is a reluctant task for most people, yet there is a clear demand for officially recognized documents. And the demand for services of the administrative state exists because without these irksome documents, the kind of life an individual wishes to pursue may not be possible. Without these documents, they cannot register their

children at a local school, and getting a formal employment would be unthinkable. Furthermore, for ordinary citizens, these documents are proof that they have rights to operate a small market or work a farmland, or that they own their properties. After all, if your ownership of a piece of land is not recognized, do you really own that land? In a way, these documents serve as a form of protection, to a certain extent, from arbitrary whims of the state and the elites. These realizations left me with unease because they underscore why durable the state can be and how its existence is propped up by ordinary citizens’ compliance with its demands.

As I wrapped up my field research and was waiting to board my flight at Suvarnabhumi Airport, I replayed some of the meetings and conversations I had in the prior weeks. I was relieved and thankful that many individuals so generously shared their time with me. The moment that lingered on my mind as I boarded my flight was when I saw Myawaddy across Moei/Thaungyin River from Mae Sot. In that moment, I am once again reminded of how cruel the coercive state can be, especially when it becomes fused with a ruthless autocratic regime. And I am left with questions about whether the administrative services provided by the state could be de-monopolized.

4

1 Scott, James C. Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press, 1998.

Figure 3: A police station in Laiza, the headquarters of the Kachin Independence Organization (Photograph by David Brenner, 2014).

Reflections from the Field

Surviving Displacement and the Art of Storytelling in the Borderlands of Myanmar

Billie Thoidingjam Guarino, Ph.D., is an Independent Scholar. Having grown up in northeastern India, a region plagued by armed conflict for over seven decades, and as a survivor of that conflict, she focuses on exploring inclusive pedagogy vis-à-vis minority literature(s), and intersections of gender with security studies, migration, and conflict in South & Southeast Asia. She conducted her fieldwork in Champhai and Aizawl in Mizoram and Moreh and Chaurachandpur in Manipur.

“People do not know us or Myanmar. And those who know us seem to have forgotten about our people and us.” - Y1

My task today is to reflect on my time with Myanmar’s “forgotten people” in the borderlands of India and an iteration of their stories, struggles, and the military’s brutality that has rendered them homeless. As I ponder, vivid memories of the individuals I encountered flood my thoughts. Everyone one of them wanted an end to the violence and longed to return home. I remember moments of excitement - first helicopter ride from Aizawl to Champhai, sharing a plate of ‘memu’ with the people in the shelters and having da-nyin-thee with them, crossing across to Myanmar at the Zokhawthar border and walking on ‘Burmese soil’ again, etc.

My project investigated the Tatmadaw’s biopolitical regime and strategy of ‘slow genocide.’ Rob Nixon employs the term “slow violence” in his book, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, to portray the disregard we exhibit towards the long-drawn-out and lethal consequences of environmental crises, which starkly contrasts with the attentiongrabbing, dramatic messaging that propels public mobilization. I incorporated Judith Butler’s concept of “precariousness” to highlight asylum-seekers’ inescapable ontological state of displacement and human insecurity. I argued that their persecution is a result of systemic and structural factors, including disciplinary power of imprisonment, supervision, and surveillance, and the invisible power of social control and regulations. I explored corporeal vulnerability, the politicization of bodies, and how the performance of protest can redefine the boundaries of oppressed bodies and their potential for political resistance.

1 Name Changed

I adopted ethnographic and qualitative research methods to conduct phenomenological interviews with protestors, asylumseekers, CDMers [participants to the Civil Disobedience Movement], and PDF [People Defence Forces] members. This approach was a crucial and innovative component of the research, as it reflected my personal background of growing up within a culture that places importance on storytelling and orality in conflict-ridden Manipur.

I want to tell the story of the children asylum seekers. I did not interview them, but they were conspicuously present throughout my research. They were not actively protesting the military dictatorship but exhibited their defiance of authoritarianism and resilience through their artworks. I documented their art made on walls and pages of the records register that documented people in each shelter.

I am still disturbed by a young girl who was shaving a block of wood into kindling. I saw her as we walked in to see the ‘Myanmar side’ - a stone’s throw away from the shelter. When we walked back a few hours

later, the girl was still in the same position, her gaze blank, mechanically hewing the wood. I cannot help but wonder about what she must have gone through. The Tatmadaw has killed, imprisoned, tortured, and sexually abused children. According to the Human Rights Council report published in June 2022, detained children have been subjected to abuse similar to adults.2

Like the adults, the children deal with the trauma of displacement and loss of home and endure harsh living conditions and limited access to education, healthcare, food, and water. However, they have coped better with the trauma they had experienced. Their artworks tell a story of remarkable resilience and adaptability. They have formed close-knit friendships with other children and learned to rely on each other for support. It was endearing to see that a group of four girls had adopted a stray kitten in one of the shelters.

Another aspect of storytelling that I have to highlight is the lack of ethical concerns of Indian ‘parachute journalists’ who visit the northeastern states for ‘scoops.’ The Union Home Ministry

5

Figure 1. Resilience - collage of artwork by children in shelters in Northeastern India

2 “Detained children have reportedly experienced many of the same types of abuses that have by used against adults: cutting with knives, beating with fists, guns, and rods, kicking, pulling out fingernails and teeth, burning with cigarette butts, stress positions, mock executions and burials, deprivation of food and water, and being forced to drink toilet water.”

had sent an advisory to “the four northeastern states Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh” to not give asylum except for medical emergencies.

On June 19, 2022, The Print published an article: “‘They’re taking over our hills’: Manipur groups want NRC to weed out Myanmar refugees,” by journalist Sonal Matharu. During her interview with Mary and John, she unintentionally disclosed their location and identity, despite changing their names and taking photos from behind to avoid revealing their faces.

Asylum-seekers who come under the radar of the state are arrested under the Foreigners Act. On June 28, 2022, nine days after the article was published, the Manipur Police conducted a “massive operation” checking door to door in search of illegal Myanmar nationals, and 80 individuals were apprehended. The adults - 25 men and 35 women - were imprisoned, while the 20 minors were sent to a juvenile observation home. These children were still in the juvenile centers during the time of my fieldwork.

In 2018, the separation and detention of children from their parents who were seeking asylum in the United States sparked global outrage. Little attention is paid to detained Burmese children, and there is no public outcry. There is no one to tell their story. There is no one to share their story, and even the parachute journalists have moved on as their stories are not newsworthy or too controversial, leaving these stories buried and forgotten. While migration and refugee crises have been actively engaged by academics, activists, journalists, and policymakers, the focus regions are often the US and

Europe. As a result, certain gaps emerge where people disappear, are forgotten, and ignored from our collective and individual consciousness – one of these gaps is the violence and consequent refugee crisis in Myanmar.

When the coup happened in Myanmar, and military brutality was exposed, everyone made the right noises. The situation no longer gets enough attention, but that does not mean the violence has ended. There is an ongoing civil war in parts of Myanmar, but state-controlled media suppress all news of violence. Shelling by the military happens almost every day. Such footage is only available through individual uploads on Twitter and Facebook. The act of recording and sharing this footage becomes an act of defiance and protest. The term “resistance” has become so idealized that it has become fashionable for many. However, resistance is often the only means of survival for those who live

in areas plagued by conflict and violence. Like George Floyd’s last words, “I can’t breathe,” becoming the refrain and a rallying cry of the Black Lives Movement in America, for the people of Myanmar, surviving the military’s violence and living to tell the tale of the oppression has become an act of resistance.

To conclude my reflections, l draw upon the crucial role played by ‘storytelling’ and victim-survivor testimonies in closing the aforementioned gap. The protesters, members of the PDF, and performance artists that I studied for my project play a crucial role in bridging this gap. One of the most wonderful things about storytelling is that a tale’s conclusion is yet to be written, waiting to unfold in the future. I hope the story concludes with my little friends returning home to rebuild a Myanmar founded on the principles of democracy.

6

Figure 3. Children returning from school at Zokhawthar village in Champhai District, Mizoram. The Young Mizo Association and the Village Council have been instrumental in enrolling children asylum seekers in school and providing uniforms and books.

Figure 2. Four girls and their kitten in Khuangleng in Champhai District, Mizoram

Figure 4. Zokhawthar-Rihkhawdar bridge. The photo was taken from the Rih (short for Rihkhawdar) in Falam District, Chin State, Myanmar.

A Review of Digital Collections of Shan Manuscripts

Dr Jotika Khur-Yearn is the librarian for Southeast Asia, History, Religion and Philosophy at the Library of SOAS University of London and a Teaching Fellow of the Shan State Buddhist University, Taunggyi, Shan State, Myanmar. His research focuses on classical Shan lik loung poetic texts, many of which are still preserved in traditional locally made Shan manuscripts. This expertise has led to his participation in several projects on cataloguing and preserving old Shan manuscripts during the last two decades. A Co-Principal Investigator of a UCLA-funded documentation project undertaken by the Inya Institute in the Shan State, he puts this project in the larger context of digital collections of Shan manuscripts available worlwide.

The Winter 2023 newsletter reported about field trips conducted in late 2022 first in Taung-gyi and then in Kengtung for identifying manuscript collections at monastic libraries and with a view to digitizing them in the future. At this time, it seems appropriate to gain a broader picture of collections of Shan manuscripts (including those available in digital format) currently preserved at institutions outside Myanmar. The review that follows will show that Shan manuscripts (whether in digital format or not) are more readily accessible for research from these institutions than at any monastic institutions located in the country. The purpose of our UCLA-funded project on Shan monastic libraries is an attempt to redress the situation and ensure that manuscripts held in significant monastic libraries of the Shan State are preserved in correct conditions and in digital format, and also accessible to the community of scholars for research purposes.

Before starting this review of collections, let me first offer some background on manuscript cultural practices in the Shan State. As it is well known, the tradition of making and commissioning Shan manuscripts came out of the Buddhist practice of merit making and other ritual performances. These traditions and ritual practices still exist today even though they are declining rapidly. Because of this tradition shared across the area, collections of manuscripts can be found all over the Shan communities.

While the majority of Shan manuscripts feature Buddhist texts, other subject fields that can be found in these textual sources include folklore, history, astrology and spiritual rituals, such as healing, charms, and protection in which many types of ritual

performances are involved including the practice of tattooing and making magical candles. Procedures related to these ritual performances are usually presented in the form of instruction manuals and featured in old Shan manuscripts (Terwiel, 2003:33).

In this piece, I discuss the digital collections of Shan manuscripts that I have accessed over many occasions in the past few years. Digital collections of Shan manuscripts have become treasure houses for me and opened to me the gates to troves of information about various aspects of Shan history, culture, and Buddhism as I will show here through prominent examples. In addition to a greater accessibility of digital collections of Shan manuscripts, I was also involved in a few cataloguing projects of Shan manuscripts; consequently, I came across or was made aware of many more collections of Shan manuscripts that are still awaiting digitization.

It is amazing that we are now living in and experiencing the digital age. With the help of digital technologies, it is much easier for us to get access to old documents such as manuscripts. Digitization of these materials offers many benefits. It allows us access to original documents which are normally kept in the archives or access to special collections usually preserved under strict rules. In other cases, like Shan manuscripts which have been traditionally kept by local communities, digitization also allows us access to these sources without having to travel to remote places which may be also difficult to reach. And yet, even though digital technologies have become widely available in the last twenty years and many Shan manuscripts from various museum collections in European countries have been digitized, with some invaluable

Shan manuscripts being now available for the public at large, it is important to recognize that there are still challenges ahead and digitization of manuscripts remains a long-term effort.

Here, I would like to introduce some digital collections of Shan manuscripts that I have visited and accessed in the past eight years or so. The manuscripts that are featured here below are selected samples and represent the highlights of these digital collections.

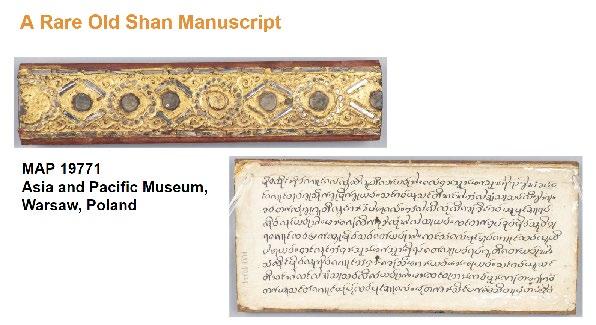

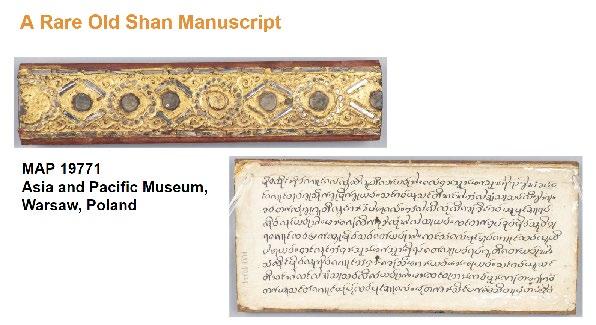

There is a notable Shan manuscript in the collection of the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw, Poland (Reference no. MAP 19771; see next page upper picture). My assumption, based on my assessment of the digital version of this manuscript, is that while the manuscript is incomplete, it was also partly destroyed by a modern artist, who used it as a base/tool to attract collectors. The artist may have used paper colon to cover the old texts on some pages and make them look like new blank papers for the images depicting the famous Eight Victories of the Buddha. Underneath of images, there are Burmese descriptions written with a modern ball-pen.

The subject of the text is on the teaching of Buddhism, with a focus on the meditation of the life of a lay person as a messy and suffering one and the life of a monk as a simple and peaceful one. While the physical form of the manuscript looks to be old, I can also assume that the genre of the text is also of an early style of classical Shan poetic literature, known in Shan as ‘Langka Sawng Kio’ [Poetry of Two Strands], confirming a highly possibility of an old age of the manuscript. It is also notable that the script of the text also looks to be an old form of early Shan writ-

7 Insights

ing which did not use tonal mark: indeed, the manuscript’s text does not feature a single tone.

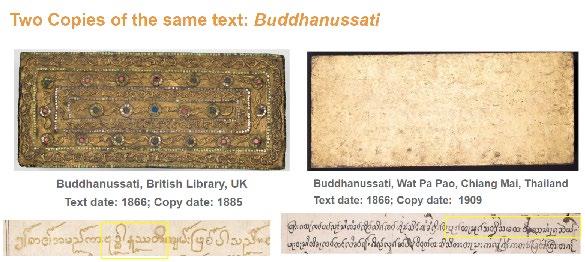

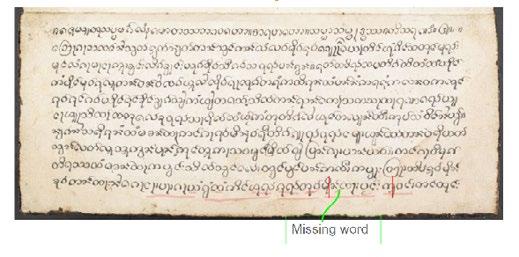

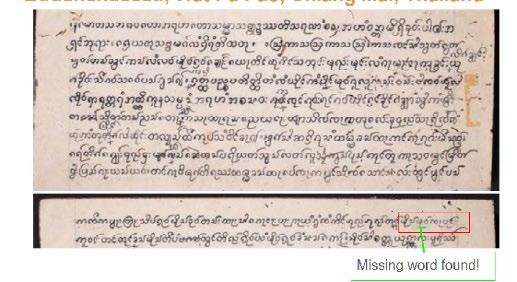

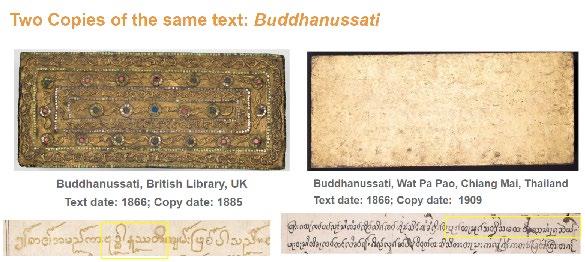

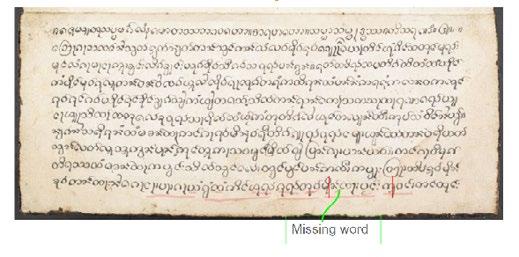

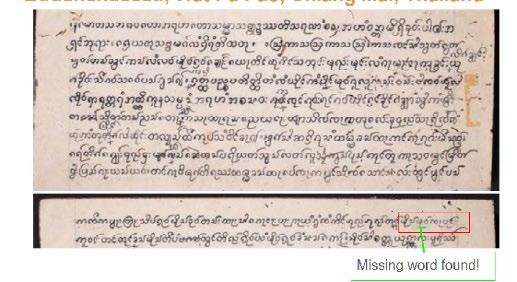

Turning to manuscripts of higher scholarly significance, I would like to briefly present two copies of Buddhānussati, or ‘Verses of Recollection on the Buddha’, that can be recited as a meditation on the Buddha and the qualities of his teachings. Both manuscripts are written in Shan script, with one preserved at the British Library and the other at Wat Pa Pao in Chiang Mai, Thailand; both have been digitized and can be fully accessed online as shown in the photos below.

Both manuscripts have beautiful, gilded covers. While the cover of the manuscript at the British Library is gilded and decorated with floral arts and inlaid coloured glasses, the cover of Wat Pa Pao’s manuscript is all but gilded without any floral art or glass. This type of plain gilded manuscript has been described by Jana Igunma as “a bar of pure gold”; Igunma also added that “the idea of pure gold rather refers in a figurative sense to the purity and the moral value of the sacred texts contained in these manuscripts” (Igunma 2016 ). Usually such gilded covers were

made possible by sticking several layers of the sa mulberry papers together and then having them painted with red or black lacquer to harden the cover before decorating it further with floral art designs and gold decorations. Manuscripts with gilded covers are an indication of a significant donation of manuscripts from well-to-do people in the communities such as local lords or landlords.

When comparing the texts of the two manuscripts, we can see that more than ninety-nine percent of them are the same. However, it is worth noting

8

MS Ref: Or 12040 MS Code: 010910102_00 ; Lanna no. 4453]

Map 19771: Asia and Pacific Museum, Warsaw,

that there is one very important word, a rhyming word, which is missing from the manuscript copy of the British Library. And this missing word is found in the manuscript copy of Wat Pa Pao. This example shows how digitization of manuscripts allows researchers to identify scriptural variations between similar texts and how this new technology offers researchers an opportunity to expand textual research across collections spread around the world, in turn contributing to a philological approach to Buddhism. While each of the manuscripts has its own unique features, some manuscripts also share some commonalities, e.g. the main contents of the texts and the sequence of how data such colophon of the text, including date of composing and the names of the original donors are placed in the overall text. This is clear evidence that all manuscripts are invaluable and all of them ought to be preserved and, ideally, digitized.

There is another digital manuscript entitled Buddhānussati, which is kept at the Punglong Monastery, Kyaukme township in the northern Shan State of Myanmar (MS No. 92). The significance of this manuscript is that, although it bears the same title, Buddhānussati , as the two manuscripts presented above, the genre or style of writing is rather different. Yet, the text’s content seems similar across of all three manuscripts. This manuscript is dated 1920 (1282 SE; image no. 0011232), but further study is needed to determine whether the date is a copy date or the date of composing. My initial assessment is that this manuscript could be the original work, judging by the fact that there are many corrections of spelling mistakes throughout the manuscript. Further research is needed for determining the name of the author of the text and whether a copy of this text is found somewhere else.

This manuscript is part of a digitization project conducted by the Inya Institute in the village of Pung Long village, Kyaukme township, that took place in 2017-2018 and supported by the Gerda Henkel Foundation. I see this digitization project as a special one mainly because the collection is situated in an area where a number of armed groups have been operating for many decades. Recent fighting north of Kyaukme between the armed wing of RCSS, one of the Shan armed groups, and the Ta’ang armed group, TNLA, have led to the displacement of villagers and may also have compromised the integrity of Pung Long Monastery and the paraphernalia preserved there, including its manuscript collections. Following the digitization of its ninety-two manuscripts, I was able to conduct a cataloguing of the collection which is now available at this link. This digital collection is a real treasure house for the history of the monastery and the area which has a rich diversity of ethnicity and cultural heritage.

9

MS Ref: Or 12040

MS Code: 010910102_00 ; Lanna no. 4453]

To sum up, I would like to say that the digital collections of Shan manuscripts are highly significant treasure-houses. I only briefly mentioned the collection of the Asia and Pacific Museum, Warsaw (Poland), which holds 50 manuscripts (all digitized) and that of the British Library which has digitized 10 Shan manuscripts. Also worth mentioning are the Digital Library of Northern Thai Manuscripts, featuring 178 Shan manuscripts, and that of SOAS, University of London, which has digitized 4 of over 20 Shan manuscripts. As can be seen from this brief review, most Shan manuscripts in digital format are available from institutions located outside Myanmar, there is therefore a need to pursue documentation of collections of manuscripts in the Shan State and digitization of these collections, especially at this time of deep political crisis. Our UCLA-funded project conducted across the Shan State and Northern Thailand aims to partly fill this gap.

References

Igunma, Jana (2016). ““A bar of pure gold”: Shan Buddhist manuscripts”, Asian and African studies blog, The British Library, UK, published on 25 March 2016. [accessed 26 June 2022].

Khur-Yearn, Jotika (2018). “Working notes on the cataloguing of the digital documents of the monastic collection of Pung Long monastery, Kyaukme, Shan State, Myanmar”; a full final version of the catalogue and the digital collection are kept at the Inya Institute, Yangon, Myanmar (https://archive-inyainstitute.org/).

Khur-Yearn, Jotika (2020). “Working notes on the cataloguing of the digital documents of the Burmese collection at the Asia and Pacific Museum, Warsaw, Poland”; a final version of the catalogue and the digital collection are available online at https://manuskrypty. muzeumazji.pl/en-collection-burmese/

Terwiel, B. J., & Chāichưn Khamdǣngyōttai. (2003). Shan manuscripts. Stuttgart: F. Steiner.

Websites

The British Library, Digitised Manuscripts: https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/

Digital Library of Northern Thai Manuscripts (Lanna): https://iiif.crossasia.org/s/ lanna/

Inya Institute Digital Archive : https:// archive-inyainstitute.org/

Asia and Pacific Museum, Warzaw, Poland: https://manuskrypty.muzeumazji.pl/encollection-burmese/

10

News from our Staff

I am Pyae Phyoe Myint and recently joined the Inya Institute becoming the organization’s new Education and Training Manager. Before this, I worked at a nonprofit organization for a year and have more than eight years of work experience in the education sector. Before I move on to further explain about my working experience, I would like to share some information about my educational background.

I got a Bachelor of Education from Yangon University of Education with a high GPA. Then I earned a Master’s degree with a specialization in Educational Planning and Management. I joined the Education College (now Education Degree College) as a teacher so as to utilize the knowledge gained during the Master’s degree course and share it with undergraduate, graduate students and in-service teachers. In 2017, I started a doctoral degree focusing on coping strategies pursued by teachers to improve their work life balance but it was postponed after the coup.

Regarding my work experience, I worked in both basic education and higher education sectors. My time at the Education college was quite exciting and challenging for me since I had to teach a wide range of learners of different age

levels, backgrounds and motivation levels. The discussion time with graduate level students was particularly demanding as I had to prepare lots of teaching learning materials including reading papers, questions and videos etc. The most memorable time at the Education college was when, facing a lack of interest, engagement, and motivation from students upon using traditional textbooks, I decided to conduct some participatory action research (PAR) using videos, and other teaching materials, in addition to using textbooks. The insights gained from the experience were later shared with my fellow teachers so that they can adapt their teaching learning resources instead of only relying on outdated contents. When the Education College was upgraded to the Education Degree College, a new approach to curriculum development was introduced, that of spiral curriculum, with key concepts presented repeatedly, but with deepening layers of complexity. This approach also included a fair proportion of projects, case studies and quizzes that encourage prospective teachers to acquire new teaching skills more adapted to the 21st century. In turn, the new approach required the teachers to do lots of preparation including the activity named “lesson study”. I keenly participated in every lesson study conducted by each teacher educator and gave supportive ideas to run the teaching process smoothly.

The turning point of my life was when I joined a non-profit organization after the 2021 coup. I gained lots of experience not only in teaching but also in research. As a part-time instructor, I developed syllabi for two courses related to leadership and management. and adapted them following the students’ feedback before the new class starts. The organization offers all instructors lots of liberty in their mandate so each of us is responsible for applying pedagogy following one’s interests and preparing teaching materials to build an effective teaching learning environment. Joining that organization gave me the chance to pursue my greatest interest:

conducting research. This was done by participating as a co-lead researcher in a research project focusing on the barriers university level students faced when continuing their education after the coup. That was my very first time leading the team and supervising the research project.

The experience I have gained in the education field working for both the public and non-profit sectors brings me to work at the Inya Institute. As an Education and Training Junior Manager, I am responsible for planning, coordinating, developing training and capacity building activities, including the creation of e-learning modules and support materials in collaboration with the team. So far I have been assisting the team in planning and coordinating the 2023 ‘Languages of Myanmar’ Course series that will be held in late June together with the Shan, Karen, and Kachin language teachers. I have been developing a plan for short-term training courses on critical thinking skills and social science research. Other tasks include the presentation of our library resources by writing Myanmar language summaries of books held at the institute. The book summaries express with clarity and the careful selection of Myanmar words the gist of the book’s contribution to the general public. This new experience encourages me to read more books in order to use the correct words and disseminate information without any ambiguous meaning. I also have to help the team with the translation of English language materials into Myanmar that are used for short videos on a variety of research-related matters, like the one recently completed which offers tips on how to evaluate information sources. I really look forward to taking the role of education and training junior manager to the fullest of my potential including participating and assisting the team in the conduct of research projects with local and international researchers and interns.

11

Pyae Phyoe Myint Education and Training Manger

News from our Staff

Aung Kyaw Phyo Digital Resources and Information Assistant

My name is Aung Kyaw Phyo and I am 24-years-old and I am the new Digital Resources and Information Assistant at the institute. I am Karen ethnic and I live in North Dagon with my family. I passed the Matriculation exam in the year of 2014. And then I joined the Bachelor Program at the Myanmar Institute of Theology (Liberal Arts Programs) with a specialization in Computer Studies. During the Bachelor programs’ years from 2016 to 2020, I studied many subjects and activities and applied my learning through many practical and group works.

During the first academic year, I studied General knowledge related to Civic Education, Human Rights, Religions, Micro Economics, Health, Computer and Music. In the ‘Civic Education and Human Rights’ class, I studied the country’s constitution, the country’s recent crises (including that of the Rohingyas), as well as domestic international politics, climate change and the politics of ethnicity. Together with other MIT students I was fortunate to visit the National Parliament in Nay Pyi Taw; the visit was actually a compulsory assignment for the Civic Education class.

In the ‘Health Education’ class, teaching was carried out by Medical Doctors, Nurses, Dentists and Pharmacists who shared their experiences and basic health education. The ‘Religion’ class included teaching about eastern & western religions and philosophy of religions. As a final project of the religion class, we made a short film about forgiveness based on one of the Bible’s Psalms. For the ‘Music’ class, the instructor divided students into groups and asked them to write songs on a topic of their choice. The students then had to sing these songs in front of the whole school as a final project. During the second academic year (2017-2018), we were taught Ethics, Research Methods, Gender Studies and English. In addition to these compulsory subjects and as I also had taken Computer Studies as a major, I learned Programming, Networking, Multimedia, Project Management, System Analysis, Web Development and Mathematics. In the third and final academic year, I had chosen Music as my minor for my Bachelor Degree so as to learn music theories and how to play the violin.

As a Computer Studies student, I created a total number of five projects spanning each of the academic semesters during my time at MIT. I created a typing tutor software with Python programming for the final Python project, WordPress and Drupal for website development. The three other projects focused on a student information system, a celebrity website and an online car rental website with HTML/CSS, PHP for web development final projects.

During the final year, all students are required to do an internship. I worked as an office intern at the Saint Francis Xavier Brothers (Department of Printing Press) which is one of Myanmar’s prominent Catholic religious organizations. During that time, I assisted the team in upgrading digital documents and helped it develop the media design. During the second semester of the final academic year, the Covid-19 outbreak started and all students

turned to an online teaching system. On the day of 31 December, 2020, I completed my Bachelor Degree in Computer Studies. A year before in February 2019, I also had started to study philosophy for one year at Dagon University.

Because of the uncontrollable Covid-19 situation and the 2021 Military Coup in Myanmar, it has been very difficult to get an entry level job after finishing my studies. So I started studying online classes to upgrade my skills and expand my interests. I received several certificates from online learning platforms such as Coursera, Edx, Google Foundation, SME Academy, and the United Nations. I also started some freelance activities as a video editor and online conference admin.

On the first day of July 2022, I started an internship in the Business Development section of MAGI Company, a car rental company located in Yangon. It was a six months’ internship program so I worked until 30 December 2022. I learnt basic concepts of business management, office management, vehicle leasing and maintenance, government processes, accounting and operation. I also worked as a trainee for Openfor.Co as a partnership development associate from November 2022 to December 2022. After finishing my internship, I worked as a part time data collector for the INGOs called New Humanity Myanmar and ACTED and helped the organizations’ team develop a survey about households living in slums in Insein.

I now really look forward to working as the Inya Institute’s new Digital Resources and Information Assistant in a position that will help me combine my interests in the development of web-based resources and materials and my broader interests in Myanmar-related religious, historical and cultural matters.

12

Current Opportunities at Inya

The Inya Institute is now accepting applications for a Fellow to lead the Summer 2023 Research and Mentoring program devoted to supporting the study of Myanmar’s borderlands.

The Fellow may be based in Thailand, India, or Bangladesh and will lead a series of online workshops sponsored by the institute with a group of 6-8 Myanmar researchers. During the online workshop sessions, the Fellow will mentor the group of Myanmar researchers on the development of their research papers. The first batch of online sessions will focus on research design, guidance on research methods and field research with all participating Myanmar researchers. The remaining weeks will involve one-on-one online mentoring sessions with each of the 6-8 Myanmar researchers.

The Fellow will be expected to mentor researchers whose work may address any of the following themes related to Myanmar’s borderlands:

• legacy of colonial knowledge of borderlands and their communities;

• ethno-history of borderlands;

• natural resources and challenges to environmental protection in borderlands;

• communities, networks, and trade across borders;

• legal and illegal border migration;

• humanitarian relief to refugees and public health in borderlands;

• borders at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic;

• formal and informal governance of borderlands;

• externalized economic development of borderlands;

• formal and non-formal education in borderlands;

• other themes related to borderlands.

The Inya Institute will cover international airfare (to Thailand, India, or Bangladesh, as per the Fellow’s proposed choice) and additional costs (including domestic travel, local accommodation, meals, internet costs). Within the limits of the time available outside of the Fellow’s mentoring duties, the Fellow may also engage in their own personal research work.

Following the Summer 2023 research and mentoring program, the Inya Institute will organize a conference in 2024 in Thailand on ‘Myanmar’s borderlands: past, present, and future’ in which both the Fellow and the Myanmar researchers will participate and present their papers.

Full information: https://www.inyainstitute.org/2023-summer-researchmentoring-fellowship/

Eligibility

1. The fellowship is open to post-doctoral scholars whose past or current research interests and work align with the study of Myanmar’s borderlands (see list above);

2. The fellowship is open to: (1) U.S. citizens who obtained their PhD degree in the last 10 years in a U.S. university or a university overseas: (2) foreign nationals who obtained their PhD degree in the last 10 years in a U.S. university.

Application requirement

1. Completed application form including information about the selected country, location for running the online mentoring sessions, and statement detailing past or current research on Myanmar’s borderlands, and its relevance to one or more of the topics listed above (max. 1,200 words);

2. Proposed Work Schedule showing how the online mentoring sessions will be conducted throughout the fellowship period;

3. Proposed Itemized Budget with Budget Narrative; Allowable costs include airfare, ground transportation (in the U.S. and selected country), lodging, meals and incidental expenses, and internet costs;

4. Curriculum Vitae;

5. One Academic Reference Letter; The applicant is responsible for notifying the referee of their request for letter and for ensuring the letter is submitted to the Inya Institute by the deadline.

All documents must be sent by email to the following email address: contact@inyainstitute.org

Fellowship Benefits

In addition to a stipend covering international travel, ground transportation, lodging, local subsistence, and internet costs, the Fellow will receive US $4,800 as teaching and mentorship fees.

Deadline and Notification

Applications must be sent by March 17, 2023 (11:59 PM EST).

Awards will be announced by April 21, 2023.

13

The Summer 2023 Research and Mentoring Fellowship is funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act.

Upcoming Opportunity at Inya

2023 Languages of Myanmar Course Series

Karen – S’gaw Kachin – Jinghpaw Shan – Tai Long

What

Online registration for International Applicants opening soon!

Stay

The Inya Institute is pleased to announce its 2023 language course series on three prominent languages spoken in Myanmar: (1) Kachin – Jinghpaw; (2) Karen - S’gaw; and (3) Shan - Tai long.

The three-week language course will equip participants with the essential skills needed to communicate confidently and effectively in Shan language in a broad range of situations. Our team of language teachers received training from and had course materials reviewed by U.S. trained language instructors.

No prior knowledge of these languages is required.

Who

The language course is open to undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate students, professionals, researchers, and NGO workers of any nationality, wherever they are based in Myanmar, Southeast Asia or the U.S.

The language of instruction will be English.

Karen-S’gaw Language classes will be held online:

When

• U.S. EDT: from 9:30 pm to 11:00 pm, Sundays to Thursdays, July 2-20, 2023;

• Thailand Time: from 8:30am to 10:00am, Mondays to Fridays, July 3-21, 2023;

• Myanmar Time: from 8:00am to 9:30am, Mondays to Fridays, July 3-21, 2023.

How

Kachin-Jinghpaw Language classes will be held online:

• U.S. EDT: from 8:30 pm to 10:00 pm, Sundays to Thursdays, June 18 - July 6, 2023;

• Thailand Time: from 7:30am to 9:00am, Mondays to Fridays, June 19 - July 7, 2023;

• Myanmar Time: from 7:00 am to 8:30 am, Mondays to Fridays, June 19 - July 7, 2023.

Shan-Tai Long Language classes will be held online:

• U.S. EDT: from 9:30pm to 11:00pm, Sundays to Thursdays, July 2-20, 2023;

• Thailand Time: from 8:30 am to 10:00 am, Mondays to Fridays, July 3-21, 2023;

• Myanmar Time: from 8:00 am to 9:30 am, Mondays to Fridays, July 3-21, 2023.

• For International participants, the course fee will be $80 (undergraduate students) and $380 (any other applicants). Payment of the course fee will be through Paypal and will help to cover the cost of the language teachers’ tuition. It will have to be made two weeks before the language course starts. Graduate students in difficult financial situation may benefit from a fee reduction and are invited to contact us: contact@inyainstitute.org

To apply, please go to the following link: https://www.inyainstitute.org/2023-languages-of-myanmar-course-series/

• For Myanmar participants (whether based in Myanmar or elsewhere), the course will be free of charge.

To apply, please go to the following link and fill in the Google Form here

Application deadline: May 26, 2023, 4 pm, Myanmar Time

We look forward to your participation!

Tuned to this page!

July 2-20 (EDT) June 18-July 6 (EDT) July 2-20 (EDT) July 3-21 (MM & Thailand Time) June 19-July 7 (MM & Thailand Time) July 3-21 (MM &Thailand Time)

14

The 2023 ‘Languages of Myanmar’ Course Series is partly funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act.

Upcoming Events across the U.S. and beyond

April Event

1. CSEAS Graduate Colloquium Lecture: Resistance, Accommodation, Violence, and the Role of Local Administrators in Post-coup Myanmar

Location: Northern Illinois University, Zoom

Date: April 7, 2023 at 12:00 pm - 1:00 pm in Central Time (US & Canada)

Lecturer: Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

More info here

Zoom registration here

2. Democracy and Ethnic War in Southeast Asia

Location: AS8 04-04 Seminar Room, FASS NUS

Date: 10 April, 2023 at 3:00 - 4:30 pm

Speaker: Prof. Jacques Bertrand

Chaired by: A/P Douglas Kammen

After 2011, there were reasons to think that Myanmar might be growing more democratic, and that dialogue between rulers and ethnic minorities might alleviate the latter’s long-standing rebellions. Instead, in 2021, a military coup ended democratic reform, triggered mass opposition, and plunged Myanmar back into civil war. In ostensibly democratic Indonesia and the Philippines, on the other hand, rebellions respectively by the Moros and the Acehnese have transitioned to peace. Yet, it would be too simplistic to conclude that democracy alleviates or even resolves ethnic conflict. Although democratic institutions and negotiations can help to resolve deep and enduring conflicts, he concludes, they can also be used and have been used, mainly by the state, to manipulate and undermine insurgent ethnic minority groups. The presentation will discuss and illustrate these insights by comparing cases in the three countries.

More info here

3. An Attempt to Reconcile the Disputing parties?

The Burmese Saṅgharāja Ñeyyadhamma’s letter to the non-confusionists in Sri Lanka

Location: Cornell University

Date: April 14, 2023 at 10:00am to 11:00am

Lecturer: Petra Kieffer-Pülz

Between 1803 and 1813 five ordination lineages were introduced from Burma to Sri Lanka that formed the Amarapuranikāya. In 1851 a dispute

concerning the legal validity of the monastic boundary (sīmā) of Balapiṭiya in the southwest of Sri Lanka arose amongst two of them. This was a serious matter, since a sīmā is the basis for all administrative and legally binding activity of a Buddhist monastic community (saṅgha), including ordination. Since the parties were not able to resolve the conflict themselves, and since their ordination lineage was ultimately based on a Burmese ordination tradition, they turned for help to the highest authority of the Burmese Buddhist monastic community. The group who considered the sīmā of Balapiṭiya confused with the village boundary, and, hence, legally invalid, sent the first delegation (1857–1858).

More info here

Zoom registration here

4. Perilous Homelands: The Rohingya Crisis and The Violence of National Territory

Location: Cornell University

Date: April 27, 2023 at 4:30 pm

Speaker: David Ludden

The Rohingya survival crisis – in borderlands of Myanmar and Bangladesh -- has disappeared from the headlines, but Rohingyas remain one of the largest stateless populations in the world. Their suffering can be understood as an extreme example of the violence inflicted by national territory around the world. In South Asia, “partition” is the keyword in that violent history: it denotes the forced expulsion of people deemed foreign to the nation and the forced inclusion of people living on land claimed by nations during the demolition of British India. Rohingyas are among the latest and most brutalized victims of this imposition of national state boundaries on mobile imperial spaces during the ongoing global process of decolonization.

More info here

5. CSEAS Lecture Series: Merchants, Magistrates, and Mendicants: Unofficial European Settlers in Burma, 1850 - 1890

Location: Northern Illinois University

Date: April 28, 2023 at 12:00 pm in Central Time (US and Canada)

Lecturer: Trude Jacobsen Gidaszewski

More info here

Zoom registration here

June Event

1. 15th International Burma Studies Conference

Envisioning Myanmar: Crisis, Change, Continuity

Location: University of Zurich

Date: June 9-11, 2023

Tatmadaw’s 2021 coup d’etat precipitated a crisis for Myanmar and its people. Scholars are taking stock of how the coup has reshaped a wide range of issues, encompassing conflict, livelihoods, gender relations, and the environment. But although crises tear apart, they can also mend. New social relations are being formed among people and groups who were once divided, and as a result, new aspirations for the country are taking root. As scholars continue their support for research and educational endeavours, they too participate in co-creating these new futures.

More info here

Conference Event in July

1. 2023 Myanmar Update From Coup to Revolution

Location: Australian National University

Date: July 21-22, 2023

The 2023 Update Conference hosted by the ANU Myanmar Research Centre seeks to explore the complexities of the revolutionary struggle; the effects of the coup on the state and economy; and, the myriad ways in which the people in Myanmar are coping with deepening violence and poverty. How has the coup and the popular response to it reshaped Myanmar politics? How are new armed groups forming, and how are they sustained? What has happened to the civil disobedience movement? What are the social, economic, and psychological implications of continued violence? How is the diaspora contributing to the revolution? How can foreign governments and the international aid community best support resistance to dictatorship? We aim to address these kinds of questions, among others, in this conference.

More info here.

New Books On Myanmar

the motifs, designs, and patterns that appear repetitively on silver pieces. Accompanied by detailed photographs and explanatory texts, this groundbreaking volume proposes a new way of looking at Burmese silver.

century genocides bring this horrific history up to the present moment: the genocide perpetrated by the government during Argentina’s “Dirty War,” the genocide of the Yazidis by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), genocidal violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar, and China’s genocide of the Uyghurs. Powerful survivor testimonies bring the essays to life and help readers grapple with the difficult lessons presented throughout the book.

WinningbyProcess: The State and Neutralization of EthnicMinoritiesinMyanmar

Jacques Bertrand, Alexandre Pelletier and Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung

Cornell University Press, 2022

Winning by Process asks why the peace process stalled in the decade from 2011 to 2021 despite a liberalizing regime, a national ceasefire agreement, and a multilateral peace dialogue between the state and ethnic minorities. Winning by Process argues that stalled conflicts are more than pauses or stalemates. Winning by process represents the state’s ability to gain advantage by manipulating the rules of negotiation, bargaining process, and sites of power and resources. The Myanmar case shows how the process can shift the balance of power in negotiations intended to bring an end to civil war.

BuddhismandComparativeConstitutionalLaw

Tom Ginsburg and Benjamin Schonthal

Cambridge University Press, 2022

Buddhism and Comparative Constitutional Law offers the first comprehensive account of the entanglements of Buddhism and constitutional law in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Tibet, Bhutan, China, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan. Bringing together an interdisciplinary team of experts, the volume offers a complex portrait of “the Buddhist-constitutional complex,” demonstrating the intricate and powerful ways in which Buddhist and constitutional ideas merged, interacted and co-evolved.

RethinkingCommunityinMyanmar: PracticesofWe-FormationAmong Muslims and Hindus in Urban Yangon

Judith Beyer

NIAS Press, 2022

Burmese Silver from the Colonial Period

Alexandra Green

Ad Ilissvm Publisher, 2022

A stunning catalog of an exceptional collection of rare Burmese silver. Green examines silver from a local perspective, drawing on Burmese texts and information that allows for a nuanced view of

Centuries of Genocide: CriticalEssaysandEyewitnessAccounts,FifthEdition

Samuel Totten

University of Toronto Press, 2022

Four new case studies of twenty-first-

This is the first anthropological monograph of Muslim and Hindu lives in contemporary Myanmar. In it, Judith Beyer introduces the concept of “weformation” as a fundamental yet underexplored capacity of humans to relate to one another outside of and apart from demarcated ethno-religious lines and corporate groups. Rethinking Community in Myanmar develops a theoretical and methodological approach that reconciles individuality and intersubjectivity and that is applicable far beyond the Southeast Asian context. Its focus on we-formation also offers insights into the dynamics of resistance to the attempted military coup of 2021. The newly formed civil disobedience movement derives its power not only from having a common enemy, but also from each individual’s determination to live freely in a more just society.

16