Aula Mediterrània

Articles Compilation

ARTICLE

n.170 16/01/2025

MIGRACIONES INTERNACIONALES Y CONSTRUCC IÓN DEL MEDITERRÁNEO. MIRADAS HISTÓRICAS

En los últimos años, el mar Mediterráneo se ha convertido en una frontera y en un cementerio para migrantes: más de 50.000 personas han muerto intentando cruzar a la orilla norte desde principios de la década de 1990. Así, el Mediterráneo se ha convertido en la frontera más mortífera del mundo. Según la Organización Internacional de las Migraciones (OIM), en todo el mundo, 65.000 personas han muerto en rutas migratorias desde 2014. La mitad de estas muertes tuvieron lugar en el Mediterráneo.

Esta situación es resultado directo de unas políticas migratorias europeas que, desde la segunda mitad del siglo XX, han reducido progresivamente las posibilidades legales de migrar desde países del sur y, en particular, desde las costas sur y este del Mediterráneo, hacia Europa. El establecimiento del espacio Schengen (1985/1995), la biometrización de los pasaportes y la creación en 2004 de Frontex –la agencia de la Unión Europea encargada del control y la gestión de las fronteras exteriores del espacio Schengen– son distintas etapas de un modelo migratorio de control de las fronteras mediterráneas que ha traído consigo la criminalización de las migraciones internacionales. Estas medidas están amparadas por el Pacto Europeo sobre Migración y Asilo, reformado en 2023.

El control de las fronteras exteriores de la Unión Europea ha ido acompañado del refuerzo de los muros (en Ceuta, Melilla, o en la frontera greco-turca a lo largo del río Evros) y de la creación de campos de tránsito, como los hotspots creados en islas griegas e italianas en 2015. En estos países llamados «de primera línea» según lo establecido en los acuerdos de Dublín, se recogen las huellas digitales y las solicitudes de asilo de las personas migrantes recién llegadas. Estos procedimientos van de la mano con una política de externalización de fronteras que busca desplazar la responsabilidad de la gestión migratoria hacia países del sur del Mediterráneo, con el objetivo último de contener las llegadas a Europa. De este modo, la Unión Europea financia a la guardia costera libia que, vulnerando los derechos humanos, maltrata y encierra a migrantes provenientes de distintos territorios africanos que tienen la esperanza de cruzar hacia la orilla norte del Mediterráneo. Asimismo, para evitar la travesía del Sahara y la llegada a las costas del Mediterráneo, la Unión Europea financia, junto con la OIM, centros de selección de migrantes en el Sahel.

Por todo ello, varios autores afirman que, lo que la clase política europea bautizó como «crisis migratoria» en 2015, a raíz de la llegada ese año de 1,3 millones de personas migrantes –

* Catedrática de Geografía, Universidad de Aix Marseille

ARTICLE

Virginie Baby-Collin*

2

provenientes, entre otros países, de Siria–, fue más bien una «crisis de acogida»1 y, por tanto, una crisis de gestión del asilo dentro de la Unión Europea.

En definitiva, a pesar de que los países europeos son signatarios de la Convención de Ginebra sobre el Estatuto de los Refugiados, y de que no existe prueba alguna de que la llegada de migrantes tenga efectos negativos, las políticas europeas contribuyen a construir el relato de la inmigración como un problema. De hecho, cabe destacar que varios estudios científicos muestran los efectos positivos de la presencia de migrantes en las economías nacionales2, contradiciendo discursos políticos cargados de nacionalismo identitario y xenofobia.

El Atlas des Migrations en Méditerranée, un proyecto de investigación para informar sobre cómo las movilidades y las migraciones han construido el Mediterráneo En este contexto, es esencial que las ciencias sociales difundan los resultados de sus investigaciones y, así, arrojen luz sobre los procesos migratorios, demostrando su importancia histórica en la construcción del espacio mediterráneo.

En este artículo presentamos un proyecto de investigación colectivo cuyo objetivo es mostrar cómo, a lo largo de la historia, las migraciones y las movilidades han dado forma a las sociedades y culturas mediterráneas y han contribuido a la construcción de sus territorios, considerados el fruto de interacciones entre las sociedades y los espacios. Se trata, entonces, de tomar distancia frente a una omnipresente actualidad alarmista y frente a la tentación del presentismo3 para considerar las movilidades y las migraciones en el largo plazo, poniendo en perspectiva las realidades contemporáneas y movilizando los resultados de investigaciones sobre distintos periodos históricos. Así, esta obra4 es el resultado de cinco años de trabajo colaborativo de un equipo multidisciplinar de 80 investigadores e investigadoras franceses y europeos –compuesto por historiadores especializados en diferentes épocas de la historia del Mediterráneo, desde la Antigüedad hasta la Edad Contemporánea, así como politólogos y geógrafos– que aceptaron el reto.

En 2020, el Mediterráneo sigue siendo un espacio migratorio de gran importancia a nivel internacional: los países ribereños representan aproximadamente el 7% de la población mundial, pero acogen al 15% de los 280 millones de migrantes internacionales del planeta. Dos tercios residen en los países de la orilla norte del Mediterráneo y la mitad de las personas que emigraron desde la costa sur vive en Europa, lo que demuestra la vitalidad de los lazos inscritos en una larga historia común.

La observación del espacio físico del Mediterráneo muestra que, históricamente, el mar ha favorecido la conectividad de sus 20.000 km de costas, gracias al cabotaje y a las islas que han

1 Véase, por ejemplo, la obra: Lendaro A, Rodier C, Lou Vertongen Y, dir., 2019, La crise de l’accueil. Frontières, droits, résistances, París : la Découverte.

2 « Macroeconomic evidence suggests that asylum seekers are not a “burden” for Western European countries », Hippolyte d’Albis, Ekrame Boubtane, Dramane Coulibaly, Science Advances, 2018 (4) : eaaq0883.

3 Hartog François, 2012, Régimes d’historicité: Présentisme et expériences du temps, París: Seuil.

4 Baby-Collin Virginie, Bouffier Sophie, Mourlane Stéphane, dir., 2021, Atlas des migrations en Méditerranée, de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Arles: Actes Sud.

servido de escalas y asentamiento en las travesías marítimas desde la Antigüedad, como así lo relatan los míticos viajes de Ulises. El interior de los países mediterráneos es a menudo montañoso, y las llanuras y espacios costeros están más orientados hacia el mar que hacia el interior, hecho que ha contribuido a hacer del Mediterráneo ese «espacio en movimiento» del que hablaba el historiador Fernand Braudel.

¿Cómo han modelado y transformado los movimientos de poblaciones las sociedades mediterráneas a lo largo del tiempo? ¿Qué formas han tomado estos encuentros entre grupos y sociedades a lo largo y ancho del Mediterráneo? ¿Sobre qué estructuras se han construido estas movilidades? ¿Quiénes han sido los principales actores de estas movilidades? ¿Qué territorios y sociedades han resultado de estas movilidades?

El proyecto se ha articulado siguiendo una lógica temática, no cronológica, con el objetivo de confrontar los distintos períodos, las escalas y las temporalidades, y poner a prueba la diacronía. Este enfoque ha permitido discutir las propias categorías de movilidades, así como sus actores y sus efectos. El Atlas aborda de manera sucesiva las estructuras que enmarcan, controlan o acompañan las migraciones (rutas, fronteras, lugares de acogida, marcos políticos), los actores que las animan (comerciantes, obreros, esclavos, religiosos, intelectuales, artistas, etc.), así como las modalidades de contacto entre las personas migrantes y las sociedades de acogida (invasiones, colonizaciones, transferencias, cosmopolitismo, xenofobia). También permite discutir la pertinencia del término «espacio mediterráneo», poniendo de relieve las conexiones antiguas y renovadas que, a través de las migraciones, articulan el Mediterráneo con el resto del mundo, y destacando la noción de «pulsaciones migratorias»5.

Diversidad de movilidades y actores

En todas las épocas, los movimientos migratorios, voluntarios o forzados, han sido impulsados por motivos de diversa índole, como la supervivencia, la búsqueda de un mundo mejor, el deseo de descubrimiento y viaje, la sed de conocimiento o riqueza, un proyecto político de dominación, de conquista, de proselitismo religioso, de colonización o de sometimiento. Estas razones económicas, políticas, culturales, étnicas o religiosas son de carácter individual, familiar y, en ocasiones, comunitario, y toman una dimensión masiva cuando la intensidad de las crisis o los conflictos es tal que impulsa a las personas a emigrar. Por lo que al estatus se refiere, cabe destacar que éste es generalmente definido por las condiciones de movilidad y de estancia. Asimismo, conviene señalar que las sociedades precontemporáneas nunca han sido inmóviles, si bien en la época contemporánea asistimos a una aceleración y una masificación de las movilidades, facilitadas por las revoluciones industriales y tecnológicas, del transporte y, posteriormente, de las comunicaciones. Por ejemplo, aproximadamente 26 millones de personas precedentes de Italia dejaron su país entre los años 1860 y 1960.

Migraciones y movilidades transnacionales

Las migraciones internacionales, generalmente definidas por un cambio de residencia por un tiempo determinado y por motivos muy diversos, están inscritas en las movilidades de población

5 El término « pulsaciones migratorias » remite a la idea de vaivén. En este sentido, refleja que los movimientos migratorios son reversibles.

(véase, por ejemplo, las migraciones estacionales de trabajo, las trashumancias). La variedad histórica de trayectos, etapas y duraciones de estancia cuestiona la visión comúnmente aceptada de que la migración es un movimiento unidireccional y definitivo. En realidad, incluso en épocas antiguas, las migraciones a menudo consistían en movilidades, es decir, idas y venidas, retornos, que a veces se daban en personas de una o dos generaciones posteriores que no siempre regresaban al lugar de origen. Sin embargo, no fue hasta finales del siglo XX cuando se empezó a hablar de transnacionalismo para designar estos vínculos entre el «aquí» y el «allá». Desde hace ya mucho tiempo, se han creado espacios relacionales entre las sociedades receptoras y los lugares de origen, generando transferencias culturales en campos tan diversos como las artes, la gastronomía o las ciencias. Las migraciones en masa inscriben estos intercambios en la cotidianidad, abriendo espacios sociales transnacionales.

Las migraciones también pueden ser salidas ineludibles, huidas, exilios. Esto da lugar a la figura de la persona refugiada –que apareció a mediados del siglo XX– y que a veces genera dinámicas «diaspóricas» que, animadas por una fuerte conciencia identitaria, en algunos casos transforman el sueño del retorno en una experiencia concreta.

Contactos: cosmopolitismos y segregaciones

Como bien representan las grandes metrópolis mediterráneas, los contactos no son solo vectores de intercambios y cosmopolitismo. Los fenómenos de rechazo, los procesos de discriminación y sus efectos segregadores también están inscritos a largo plazo. Sea cual sea el territorio, la época o el origen de las poblaciones, la persona extranjera es frecuentemente percibida como una amenaza política y social, lo que influye en la morfología urbana de las ciudades mediterráneas, a pesar de su cosmopolitismo. Pensemos en los guetos, cuyo primer ejemplo encontramos en Venecia en 1516, pero también en las instituciones contemporáneas de los campos de tránsito y detención, como los hotspots italianos o griegos mencionados anteriormente.

Pulsaciones migratorias y el Mediterráneo como espacio-mundo Finalmente, es importante destacar que, a lo largo de la historia, los países ribereños del Mediterráneo han sido simultánea o sucesivamente espacios de salida y de llegada, de acuerdo con diversas pulsaciones migratorias. España, Italia y Grecia, al igual que más recientemente los países del sur del Mediterráneo, se han convertido en países de recepción de migrantes después de haber sido países de emigración. El Mediterráneo nunca ha sido un espacio cerrado: desde la Antigüedad, las movilidades han conectado el Mediterráneo con el mundo, el horizonte se ha ampliado y los intercambios se han intensificado. Alejandro Magno se lanzó a la conquista de Asia en el siglo IV a.C.; en la Edad Media, cristianos y musulmanes se aventuraron por rutas terrestres y marítimas desconocidas a través de Asia o del Sáhara, mientras que, desde el siglo XV, las Américas atraen a los mediterráneos. Desde la globalización de la segunda mitad del siglo XX, el espacio mediterráneo recibe, en ambas orillas, migrantes provenientes de Europa del Este, América Latina y África subsahariana o Asia. La diáspora económica china está presente en todas las grandes plazas comerciales mediterráneas. Al amanecer del siglo XXI, el Mediterráneo es un espacio de mezcla globalizada, que prolonga y amplía su función de crisol. 4

ARTICLE

n.171 28/02/2025

TRANSFORMATION OF URBAN ECONOMIES IN THE MEDITERRAN EAN: THE CASE OF TURKISH CITIES

Background: the Mediterranean as One the Oldest System of Cities

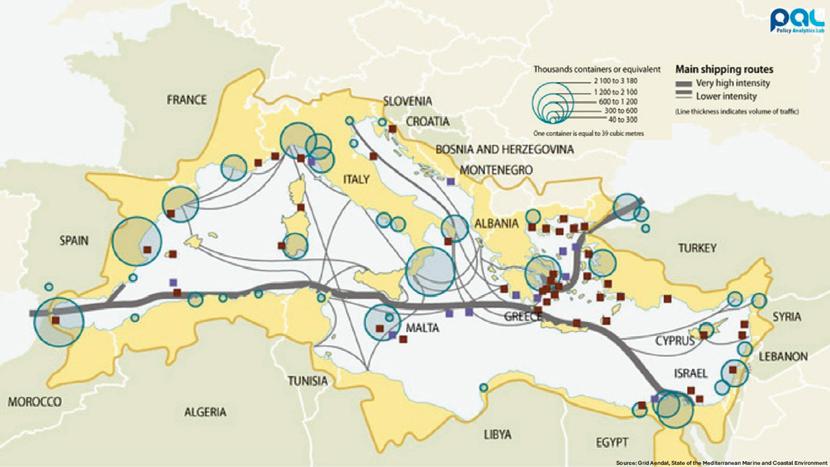

The Mediterranean is home to one of the world’s oldest system of cities, where urban economies have thrived for millennia through trade linkages. Over 2,000 years ago, during the Roman Empire, cities were already interconnected by commerce and migration. Today, the region remains a dynamic network of ports and trade routes, attracting people, businesses, investments, and millions of visitors. With 40 major cities across 23 nations − some large, some small − many still serve as economic hubs, maintaining their historical role in a system of interconnected urban centres.

System of Cities in the Mediterranean, 2,000 Years Ago and Today1

Economically, cities are engines of progress, generating agglomeration benefits. Large labour markets create more job opportunities, and firms located near one another experience productivity gains, fostering economic growth. Proximity also accelerates the exchange of ideas, driving innovation. However, urbanisation presents challenges, including congestion, pollution, crime, and, as was recently experienced, vulnerability to pandemics.

The future of cities remains uncertain, with ongoing debates about their role within nation-states, the evolution of cross-border city linkages amid growing trade barriers, and the complexities of multi-level governance. While there is no universal blueprint, some clear patterns emerge from recent research: urbanisation is closely linked to rising incomes, and denser cities tend to have lower per capita emissions, highlighting the potential role of well-managed urban density in addressing climate change.

* Managing Partner, Policy Analytics Lab (PAL), Ankara

1 Grid Aendal, State of the Mediterranean Marine and Coastal Environment.

ARTICLE

Esen Caglar*

Two Major stylised Facts about Cities2

The Tale of Turkish Cities: Key Trends in Economic Transformation Urbanisation and Economic Diversification

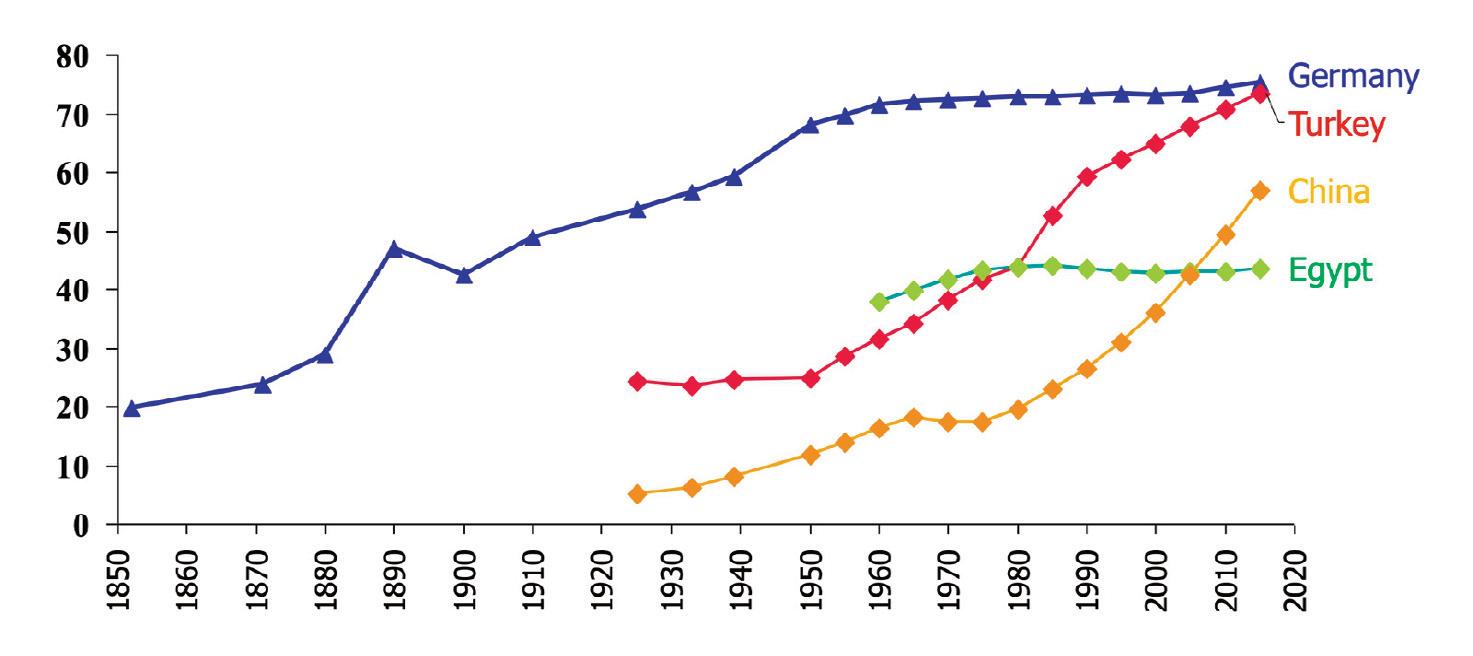

Turkey presents an interesting case in terms of rapid urbanisation and economic transformation, with several lessons to offer for other Mediterranean countries, particularly for those in the South and East. Over the past century, the country has transitioned from a predominantly rural society to an urbanized economy, with major cities driving industrialisation, employment, and economic diversification. This shift has been fuelled by internal migration, as people move from rural areas to cities in search of better opportunities. However, the uneven spatial distribution of growth has created disparities, with some cities emerging as industrial powerhouses while others struggle to integrate into national and global value chains.

Urbanisation Rate in Selected Countries, 1850-20203

One of the most striking economic trends in Turkish cities over the past two decades has been the remarkable expansion of exports. Between 2010 and 2022, Turkish exports more than doubled, showcasing greater integration with Mediterranean markets and a shift toward higher-value-added goods. Today 25% of Turkish exports, a total of 62 billion USD, goes to the Mediterranean countries.

2 World Bank, World Development Report 2009.

3 Sources: Hoffmann, Walter G. 1965. Das Wachstum der deutschen Wirtschafr seir der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Springer; Twarog Sophia. 1997. Heights and Living Standards in Germany, 1850-1939: The Case of Wurttemberg. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; World Urbanization Prospects, the 2014 revision, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Growth of the world’s urban and rural population, 1920 - 2000, United Nations, 1969, s.105-106.

3

This volume was 27 billion USD in 2010. This shift has been accompanied by increased diversification in export destinations and product categories, signalling deeper economic resilience and competitiveness.

Growth of Turkish Exports, 2010-20224

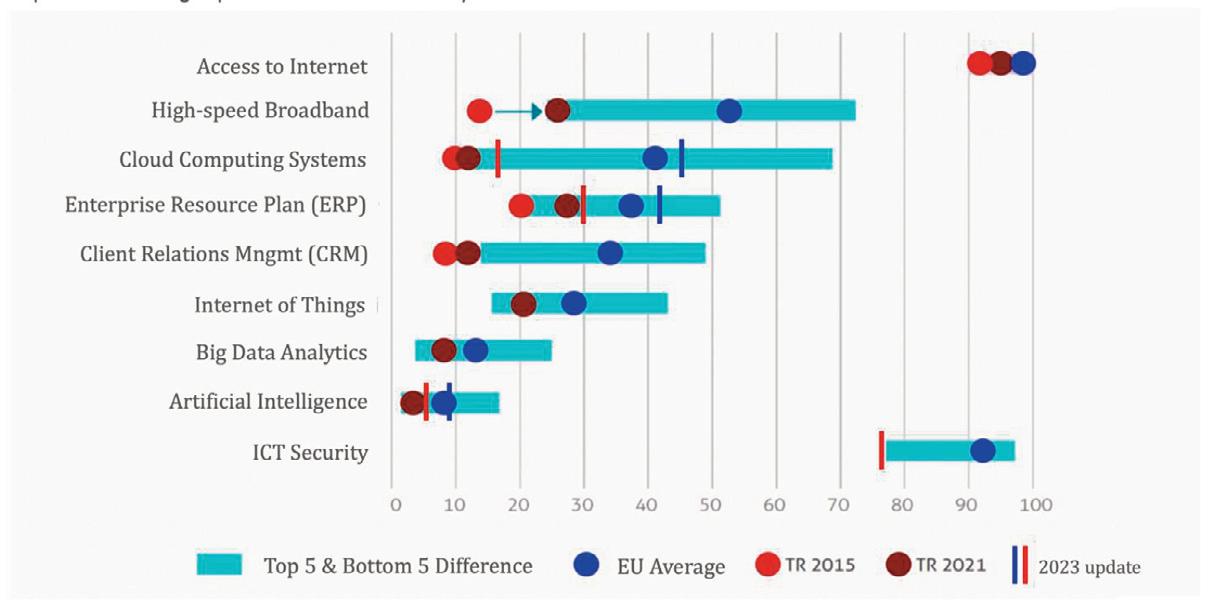

Digitalisation and the Future of Competitiveness

Digital transformation has become a defining factor in the global economy, and Turkish cities are no exception. While the country has made progress in adopting digital technologies, it still lags behind leading Mediterranean economies in key indicators such as digital skills, broadband access, and enterprise-level digital adoption. The current growth rate of digital skill acquisition in Turkey is not sufficient to catch up with the EU. To reach this target, the growth rate of the digitally-skilled population needs to nearly double.

Basic Digital Skills: Conversion Toward the EU Levels5

Recent advancements in digital tool adoption among Turkish businesses indicate a positive trajectory. However, significant gaps remain, especially in the integration of advanced digital solutions such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems and high-speed broadband in

4 Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity.

5 Source: Eurostat, TÜK HHBTA Mikro Veri Seti, PAL calculations.

smaller firms. Bridging these gaps will be crucial for ensuring inclusive and broad-based economic growth.

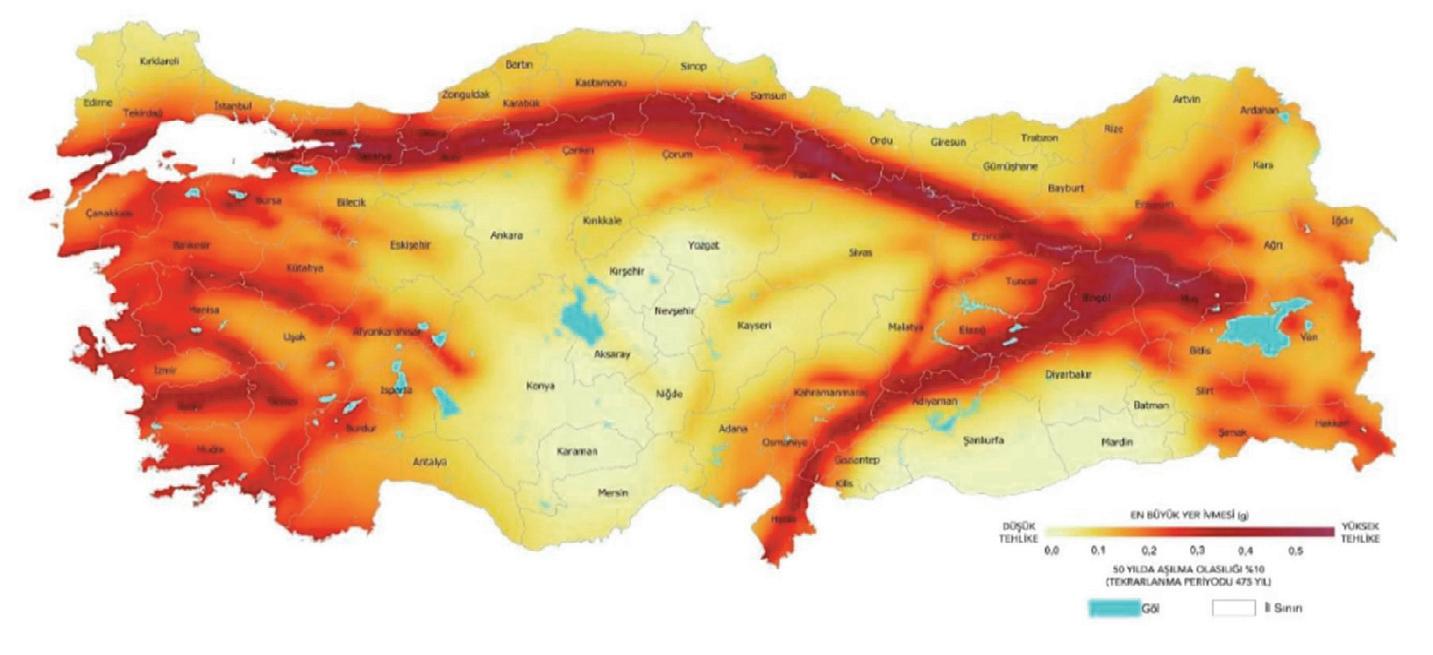

Resilience and Green Transition: Navigating Environmental Challenges

Resilience has emerged as a central aspect in urban economic planning, particularly in the face of environmental and seismic risks. Turkey is highly vulnerable to earthquakes, among other forms of natural disasters, with cities such as Istanbul and Izmir facing considerable threats due to their geographical positioning. Building earthquake-resistant infrastructure and implementing risk mitigation strategies are essential for safeguarding urban economies.

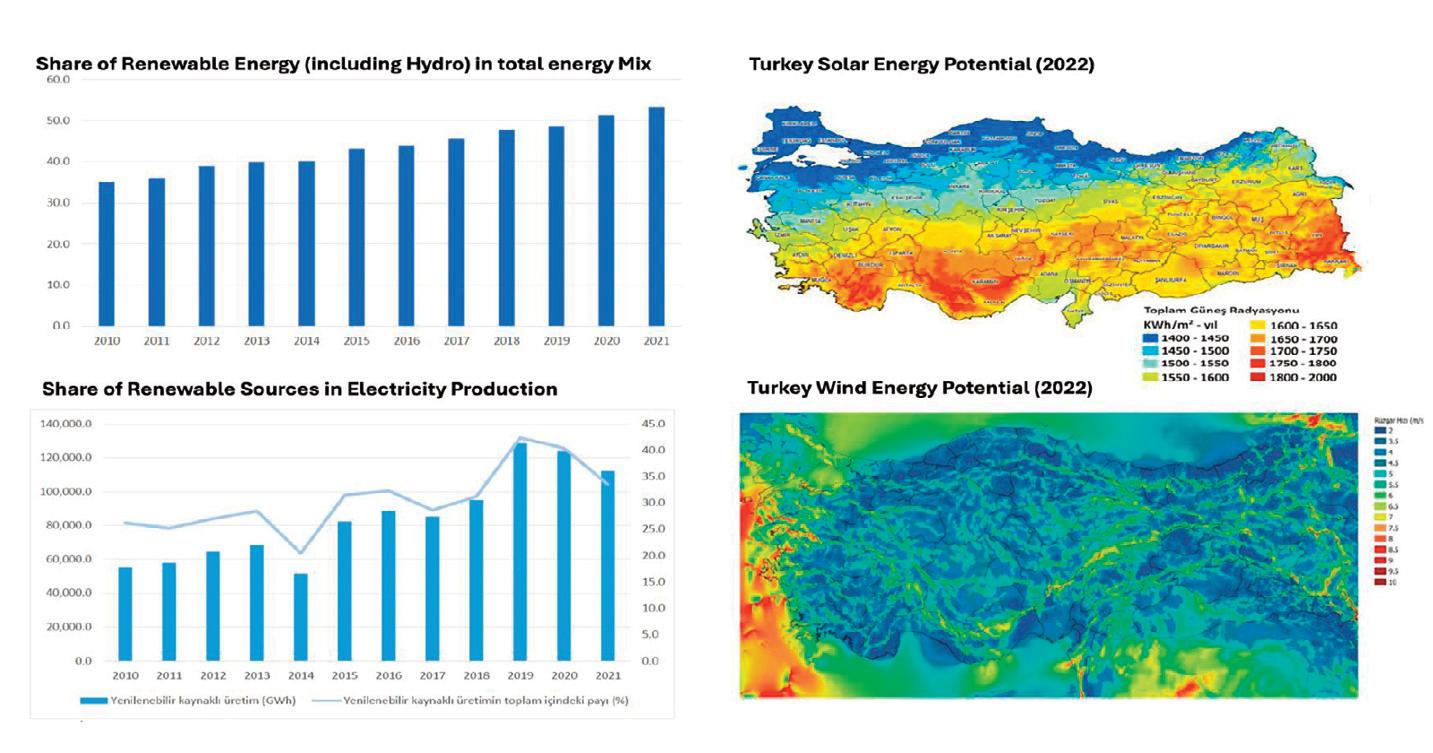

Turkey’s Earthquake Risk Map7 Environmental sustainability is another pressing challenge. While denser cities generally have lower per capita emissions, Turkey’s energy mix remains heavily reliant on coal, contributing to elevated greenhouse gas emissions. Nonetheless, the share of renewable energy in the country’s energy production has been steadily increasing, offering significant opportunities for Mediterranean cities to lead the green transition. The Mediterranean region is well-positioned to become a green-energy

6 The countries with the highest and lowest values have been selected from those sharing data with Eurostat. Source: Eurostat, TÜK GBTKA, PAL calculations.

7 Source: AFAD, National Strategy for Regional Development 2024. 4

Usage Rates of Digital Tools in Turkey vs. EU6

powerhouse, leveraging its abundant solar and wind resources. Accelerating investments in renewable energy infrastructure, particularly in urban areas, will be critical for ensuring long-term sustainability and energy security.

Renewable Energy Growth and Potential in Turkey8

Managing the New Urban Agenda: Lessons for the Future

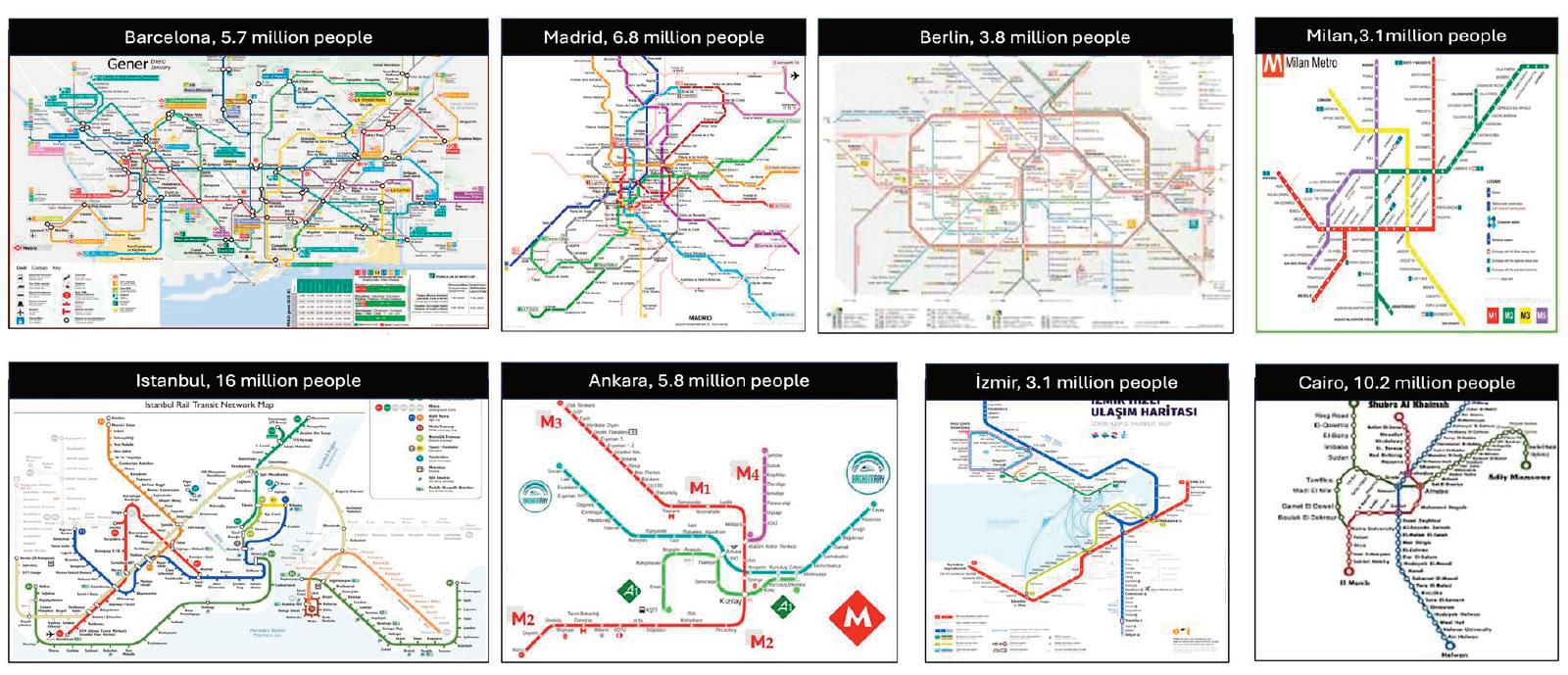

As Mediterranean cities continue to grow and evolve, they face three core challenges: managing densification, addressing urban diversity and mitigating emerging risks. Turkish cities offer valuable lessons in each of these areas; some in terms of what to do, and some on what to avoid.

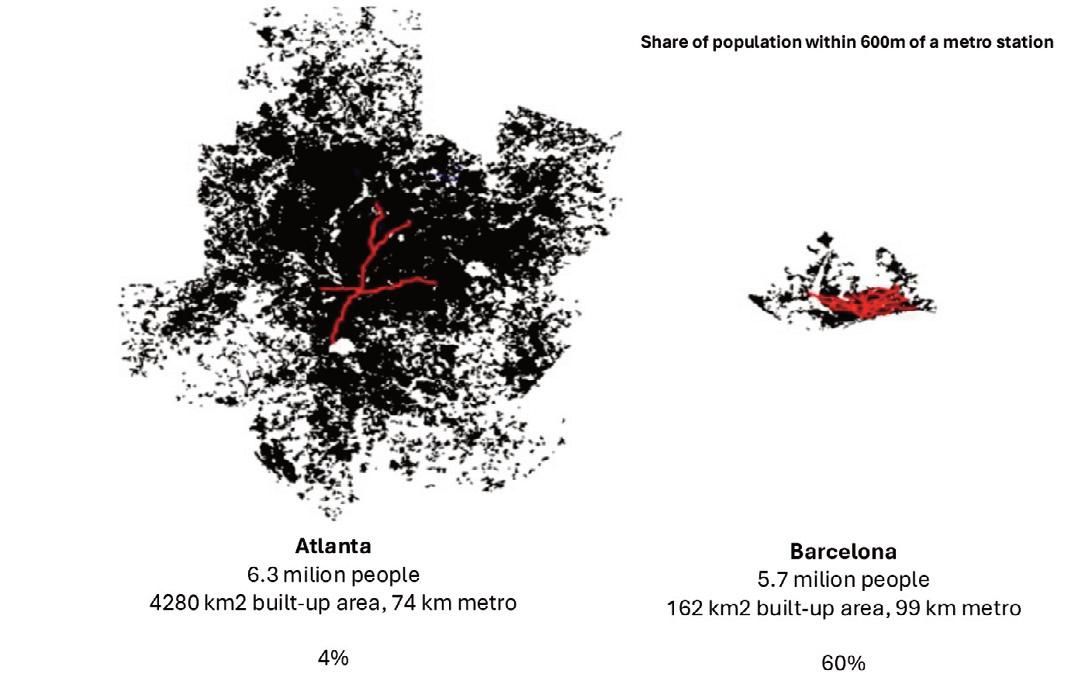

Managing Densification

Efficient urban planning is essential for managing high-density cities. Barcelona, for example, provides an exemplary model of compact urban design, integrating public transport and high population density while maintaining high living standards. Turkish cities, as well as other Southern and Eastern Mediterranean cities, can learn from such examples to develop sustainable, wellconnected urban environments.

Barcelona vs. Atlanta Urban Density Comparison9

8 Source: Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, TEIAS, National Strategy for Regional Development 2024.

9 Richardson, Harry W., and Chang-Hee, Christine Bae. 2004. Urban Sprawl in Western Europe and the United States. Burlington: Ashgate. 5

Governing Diverse Urban Economies

One of the defining features of Turkish urbanisation is the coexistence of vastly different economic structures within a single national framework. Some cities function as global economic hubs, while others remain regionally oriented. Balancing centralised governance with local autonomy is critical for fostering economic competitiveness and social cohesion.

City Typologies in Turkey10

Political and economic preferences vary significantly across Turkish cities, further complicating governance structures. Implementing a multi-level governance model that empowers local administrations while ensuring national-level coordination can help cities navigate these complexities effectively.

Mitigating Emerging Risks: AI and Economic Disruptions

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) presents both opportunities and risks for urban economies. On the one hand, AI-driven automation has the potential to enhance productivity and create new

economic sectors. On the other, it may lead to job displacement, increasing inequality and economic disruption. Turkish cities must adopt proactive policies to address these challenges, including workforce reskilling, AI literacy programmes, and economic diversification strategies.

Conclusion: Shaping the Future of Mediterranean Cities

The transformation of Turkish cities offers a compelling case study for broader Mediterranean urban economies. As they navigate the challenges of urbanisation, digitalisation, and green transition, these cities must adopt forward-looking strategies that emphasise resilience, sustainability, and inclusivity. By leveraging lessons from Turkey’s experience, from both the positive and negative aspects, Mediterranean cities can position themselves as global leaders in economic transformation and sustainable urban development.

MUERTES EN EL MEDITERRÁNEO.

CUERPOS, HUELLAS Y AFECTOS

ARTICLE

n.172 28/02/2025

Carolina Kobelinsky*

… seabed shrouds

For some went that way before the answer

Could be given – will there be sun ? Or rain ?

We’ve come to the bay of dreams.

Estos son los últimos versos del poema titulado Migrant del escritor nigeriano Wole Soyinka que descubrí en su versión en italiano la primera vez que fui al cementerio municipal de Catania1 Los versos están inscritos en cada una de las 17 lápidas blancas que forman parte del monumento Speranza naufragata, que se construyó a petición del Ayuntamiento para enterrar y rendir homenaje a las 17 personas que murieron en un naufragio en el mar Mediterráneo en mayo de 2014 y cuyos cuerpos fueron transportados a esta ciudad siciliana. Unas semanas después de su inauguración, respondiendo a la urgencia de tener que hacer frente a un nuevo y muy mortífero naufragio, la municipalidad otorga un nuevo espacio en el cementerio donde se sepultarán los restos de cientos de personas migrantes. Se trata de una parcela dispuesta en hileras de pequeños montículos de tierra, sobre los que unas placas de metal indican un código, un número, una fecha e incluso el nombre de un barco. La muerte de estas personas cuyos cuerpos llegan a la ciudad de Catania incomoda. Nadie sabe bien cómo tratarla. Ello se debe a que, tal como argumentaba Abdelmalek Sayad (2000), la muerte del inmigrante resiste a los esfuerzos de clasificación. Además, la mayoría de los cuerpos no solo son extranjeros, sino también desconocidos, sin nombre.

«Los tratamos como a cualquier otro cuerpo, pero no podemos mentir, nos afectan mucho (…) los migrantes… son jóvenes y están solos, nos conmueve a todos aquí. Estos muertos, li portiamo a casa [los llevamos a casa]». Así resume el señor Mancini, uno de los responsables de la funeraria municipal de Catania, la relación con estos muertos. La funeraria, como el cementerio, pero también el registro civil, la policía científica y la squadra mobile [policía judicial] son instituciones acostumbradas a tratar con cuerpos sin vida. Pero con estos cuerpos de personas que murieron en el mar Mediterráneo cuando intentaban llegar a Europa sin las autorizaciones exigidas por los distintos estados les ocurre algo particular, algo que no les es indiferente. Todo lo contrario.

* Investigadora en Antropología en el Laboratorio de Etnología y Sociología Comparada, CNRS, París

1 El poema está publicado en idioma original, junto a la traducción en italiano realizada por Alessandra di Maio en el volumen bilingüe Migrazioni/Migrations : An Afro-Italian Night of the Poets/La notte dei poeti afro-italiana, 66than2n, 2016, p. 74.

Estos cuerpos –tanto aquellos que fueron enterrados en lo que mis interlocutores llaman el quadrato migranti como aquellos que se encuentran dentro del monumento– fueron llevados a Catania en el marco de operaciones de rescate en el mar entre 2014 y 2018. Desembarcaron al mismo tiempo que hombres, mujeres y niños que sobrevivieron a las condiciones de viaje en embarcaciones improvisadas procedentes del continente africano. Entre 2015 y 2018, Catania fue uno de los primeros puertos de llegada al territorio italiano, y en marzo de 2016 el puerto de la ciudad se convierte oficialmente en un hotspot, donde se pone en marcha un dispositivo nacional destinado a identificar y registrar a quienes entran en el país y, en segundo lugar, a dirigirlos a diversas infraestructuras repartidas por toda Italia. Así, varios miles de personas cuyas vidas corrían peligro en el mar desembarcaron en Catania. Muchas otras murieron durante la travesía. La OIM ha registrado 31.287 muertes y desapariciones en el Mediterráneo en los últimos diez años2 Durante este periodo, llegaron a Catania unos 270 cuerpos sin vida, que fueron enterrados en el cementerio municipal. Muchísimos otros permanecen desaparecidos.

El tratamiento de los muertos depende de la cantidad de cuerpos que llegan, pero siempre se basa en los recursos y las competencias del municipio de llegada. Su presencia se anuncia a las instituciones antes de que atraquen en el puerto, lo que permite a la Funeraria municipal –a la que pertenece el señor Mancini– preparar su material y dirigirse al puerto. Esto también permite al fiscal delegado designar a uno o varios médicos forenses que acudirán al puerto para realizar un examen externo de los cuerpos con el fin de determinar la causa de la muerte. Los cuerpos son después trasladados a la morgue para la toma de muestras de ADN y la inspección forense, que proporcionará información sobre sus características físicas y rasgos especiales (tatuajes, piercings, estado dental, etc.). Allí también se catalogarán los objetos encontrados junto a los cuerpos antes de enviarlos al tribunal para que sean guardados. Una vez recopilada toda la información, los cuerpos se transportan al cementerio para su inhumación en el «cuadrado de los migrantes».

Mientras tanto, se abre una investigación judicial para determinar si se trata de un crimen y, en caso afirmativo, encontrar a los responsables. En concreto, la investigación pretende localizar a los traficantes, figuras omnipresentes en el discurso público en torno a las cuestiones migratorias. En este contexto, el fiscal puede solicitar una autopsia y llevar a cabo investigaciones para identificar a la víctima. La autopsia sirve para determinar la causa de la muerte pero, en el caso de las muertes en el mar, suele bastar con el examen externo realizado en el puerto. Las investigaciones sobre la identificación de estos cuerpos en Catania son inexistentes, ya que ninguna institución italiana o europea tiene entre sus competencias la de identificar a estos muertos. ¡Impresionante contraste si pensamos en los numerosos procedimientos de identificación y trazabilidad utilizados para quienes llegan vivos a suelo europeo!

En este contexto, quisiera poner el foco en la iniciativa de un pequeño grupo de habitantes de Catania, que seguimos cual etnógrafos junto a Filippo Furri (Kobelinsky y Furri 2024). Voluntarias de la Cruz Roja local, estas personas atendían a los y las sobrevivientes durante los desembarcos en el puerto. Un sentimiento de malestar por la falta de investigaciones para identificar y contactar

2 https://missingmigrants.iom.int/fr/region/mediterranee [consultado el 3 de febrero de 2025]. 2

a las familias fue el puntapié inicial de lo que pronto se convertiría en un proyecto para tratar de identificar los cuerpos enterrados en el cementerio.

El trabajo se pone en marcha a finales de 2017, en un momento en que la frecuencia de los desembarcos en el puerto es menos intensa. Al principio, son solo tres voluntarios motivados: Silvia, Riccardo y Davide. Todos ellos participan activamente en el programa Restoring Family Links. Creado hace varias décadas en el seno del movimiento internacional de la Cruz Roja y de la Media Luna Roja para ayudar a las familias que buscan a sus seres queridos desaparecidos como consecuencia de un conflicto armado o un desastre natural, el programa se despliega ahora en gran parte para ayudar a restablecer los contactos familiares perdidos como consecuencia del cruce y la gestión de fronteras. Durante las operaciones en el puerto, los voluntarios reparten tarjetas para informar a las personas que acaban de llegar a Europa de que el programa puede ayudarles en caso de separación familiar. Probablemente no sea casualidad que los voluntarios especialmente comprometidos con este programa, centrado en la importancia de mantener los lazos familiares, se preocupen por las muertes «que las familias no pueden llorar». Silvia, Riccardo y Davide logran convencer al presidente del comité local de la Cruz Roja del interés de iniciar un proyecto articulado en torno a los cuerpos enterrados en el cementerio municipal. Se trata de invertir la lógica habitual del programa Restoring Family Links, que se activa cuando un miembro de la familia pide ayuda para buscar a un hijo, sobrina, madre, de la que no se sabe nada y que puede eventualmente estar muerta. La propuesta es la inversa: partir de los cuerpos, se intenta encontrar a las familias.

Para poder trazar el itinerario de estos cuerpos desde el cementerio hasta sus casas, dondequiera que estén, el equipo necesita ubicar a todos los actores que puedan tener información sobre los cuerpos, incluidas las instituciones municipales y nacionales, las asociaciones de apoyo a los migrantes y personas clave como los médicos forenses. El Comité local formaliza un acuerdo para acceder sistemáticamente a los documentos elaborados por las distintas oficinas municipales y al poco tiempo firma otro protocolo con el poder judicial. La apuesta es que, poniendo en red todos los datos relativos a un mismo cuerpo, se puedan encontrar pistas sobre su identidad. El equipo comienza así a trabajar en la construcción de una base de datos para sistematizar y explorar la información existente sobre los cuerpos en busca de pistas que puedan llevar a su identificación y a la localización de sus familiares. Estamos lejos aquí del uso de los métodos forenses y del cotejo de muestras de ADN, que en Italia fueron utilizados de forma excepcional y por decisión del gobierno nacional para tratar los restos del naufragio del 3 de octubre de 2013 primero y del 18 de abril de 2015 posteriormente. El trabajo del equipo es sumamente artesanal y se despliega en un modo cercano al paradigma indiciario caro a Carlo Ginzburg (1980): se trata de buscar e interpretar detalles mínimos que puedan ser reveladores.

Silvia, Riccardo y Davide recopilan datos contenidos en documentos muy diversos: certificados de defunción, formularios de inspección forense, informes de sobrevivientes obtenidos antes de los desembarcos, declaraciones de búsqueda de familiares, objetos encontrados con el cuerpo. El trabajo es arduo, en parte porque ninguno de ellos sabe muy bien cómo hacerlo. Una vez construida una versión inicial, muy sencilla técnicamente, de la base de datos, el equipo busca elementos que puedan conducir a identificaciones. Se mantienen conversaciones con interlocutores clave de las instituciones, por ejemplo, de la squadra mobile si las pistas proceden de un informe policial, o del 3

registro civil si se trata de información facilitada en sus oficinas. Ello anima al equipo a revisar o ajustar las pistas. Aunque el pequeño equipo constituye el núcleo duro de este trabajo, muchos agentes de las distintas instituciones comienzan a participar activamente en estas charlas. Todos sin excepción habían recibido con gran interés la iniciativa desde el principio, subrayando siempre la importancia de colmar la ausencia de investigación oficial. Para todas estas personas, independientemente de sus biografías, la juventud y la soledad de estos muertos dejan huella. Durante las charlas, el registro empático al hablar de estos «Otros» muertos, que la mayoría de las veces se asocia a un «Nosotros», es muy habitual, al igual que la importancia que otorgan a destacar la humanidad compartida con estos difuntos. Los discursos se acompañan de prácticas que dan cuenta de la atención especial que se presta a estas personas fallecidas.

«Li portiamo a casa», nos explicaba el señor Mancini. El responsable de la funeraria quería que comprendiéramos que el recuerdo amargo de haber tenido que ocuparse de los cuerpos de migrantes los acompañaba a él y a sus compañeros fuera de las horas de trabajo. Nos contó que conversaba sobre estos «pobres jóvenes» con su esposa. Nos contó también que no decía nada sobre el estado de degradación de los restos. Lo mismo le ocurre a la inspectora Pessina de la policía científica, quien charlando con su hija adolescente intenta «hacerse una idea de quiénes eran» las personas fallecidas. Hablar de ellas fuera del espacio estrictamente dedicado a su tratamiento material es una forma de introducirlas en la esfera de las amistades y las relaciones familiares. En estas conversaciones, los muertos del Mediterráneo aparecen a menudo como un grupo relativamente homogéneo de personas que merecen ser respetadas y honradas. Pero a veces las conversaciones giran en torno a una persona en particular: un niño pequeño del que nadie sabe con quién viajaba pero que fue enterrado junto a una mujer; un hombre y una mujer que se ahogaron pero cuyos informes forenses indicaban enfermedades graves, y que han sido objeto de especulaciones en cuanto a su relación (¿eran hermanos o pareja?). Durante una charla en la oficina de la inspectora Pessina, la imaginación se activa mirando una foto encontrada en el pantalón de un joven fallecido que muestra a una joven sentada a la sombra de un árbol. Davide comenta que tal vez se trate de la prometida del difunto, la inspectora dice que para ella es la hermana. En el mismo sentido, algunas de las personas que participan del proyecto no dudan en nombrar a estos muertos tomando prestados nombres que aparecen en el testimonio de un compañero de viaje o en algún documento que les concierne, que no son el resultado de un proceso de identificación, pero que les permite liberarse de las nomenclaturas administrativas que adjudican un código alfanumérico a cada cuerpo y acercarse un poco más a las personas. Los muertos también se inmiscuyen en las vidas de quienes participan en el proyecto a través de sus sueños. Los empleados de la funeraria suelen tener pesadillas en las que los muertos del Mediterráneo están descompuestos, solos o perdidos, y el soñador se ve incapaz de cuidar de ellos. Para otros que no están en contacto directo con los restos, en sus sueños es habitual que aparezca la soledad que padecen estas y estos migrantes. O las vidas que las y los soñadores inventan para las personas fallecidas.

Soñar con quienes están enterrados en Catania, hablar de ellos o ir a visitarlos al cementerio son actos pequeños pero que complementan el trabajo y las actividades que cada uno de nuestros interlocutores lleva a cabo dentro de las distintas instituciones, o en relación con la base de datos, forjando vínculos afectivos y relaciones de proximidad. Imaginar y nombrar son prácticas que 4

intensifican la presencia de los muertos y que están en el centro de la emergencia de una nueva inscripción social de estas personas; una inscripción junto a estos hombres y mujeres que les atribuyen un lugar en sus vidas.

La dimensión hospitalaria atraviesa el proyecto desde el comienzo. Riccardo presentaba el proyecto como un «acto mínimo de hospitalidad». Para Silvia, Riccardo y Davide se trata ante todo de «respetar» a los muertos ofreciéndoles la hospitalidad que deberían haber recibido en vida. Esta se traduce en un conjunto de prácticas destinadas a cuidar de los muertos y una forma de denuncia pública del carácter hostil del régimen de frontera en Europa. En este sentido, la hospitalidad tiene una dimensión política definida, que nuestros interlocutores no dejan de afirmar. Seguramente no todas las personas implicadas en el proyecto comparten esta idea. Sin embargo, todas subrayan la importancia de «acoger» y recibir con dignidad a «los migrantes muertos». La relación naciente con ellos y el lugar que les adjudican en sus vidas no están claramente definidos ni se expresan con palabras, pero tienen muchos puntos en común con una forma de parentesco, casi una forma de adopción. El apego que surge de pequeños actos de atención y cuidado dota a la hospitalidad de una dimensión íntima.

Las experiencias íntimas, privadas y públicas de hospitalidad y la proximidad con los muertos cuyos cuerpos están enterrados en el cementerio municipal se entrelazan constantemente, produciendo un desplazamiento en el «reparto de lo sensible» (Rancière 2000), que da espacio, visibilidad, textura a quienes murieron en el Mediterráneo. Así, las y los cataneses implicados en el proyecto contribuyen a la construcción de otro relato sobre los efectos del entramado de políticas migratorias en Europa. Un relato situado, anclado en una gramática afectiva que resulta –en un nivel acotado, marginal pero certero– políticamente potente.

Referencias citadas

G INZBURG, C. 1980. « Signes, traces, pistes. Racines d’un paradigme de l’indice ». Le Débat VI (6), p. 3- 44.

KOBELINSKY, C. Y F. FURRI, 2024. Relier les rives. Sur les traces des morts en Méditerranée, París, La Découverte.

RANCIÈRE, J., 2000. Le partage du sensible. Esthétique et politique, París, La Fabrique.

SAYAD, A., 2000. Préface, Chaïb, Y. L’émigré et la mort, Aix-en-Provence, Edisud, p. 5-16.

UNA PERSPECTIVA TRANSNACIO NAL I CULTURAL

DE LES XARXES MERCANTILS A (I DES DE)

LA MEDITERRÀNIA OCCIDENTAL

ARTICLE

n.173 6/03/2025

Josep San Ruperto*

Els darrers anys, la història transnacional ha adquirit un notable protagonisme en la historiografia. Més enllà de representar una «moda» historiogràfica, els seus pressupòsits ens mostren un conjunt d’eines i qüestions analítiques bàsiques que contribueixen a la comprensió de processos de connexió interregionals en el marc de la primera globalització des de finals del segle XV. En el cas de la Mediterrània, disposem ja de nombrosos estudis que adopten aquest enfocament. Un bon exemple són els treballs de Francesca Trivellato i Sebouh Aslanian, que analitzen els agents mercantils de les diàspores sefardites i armènies des d’aquesta perspectiva. Tot i que la perspectiva transnacional ha començat a aplicar-se a estudis d’història cultural, podem assenyalar que encara queda un llarg i prometedor camí per descobrir plenament el seu potencial. Aquest enfocament ofereix la possibilitat de repensar períodes històrics, com l’època moderna ibèrica, aportant una major complexitat, un avenç que ja s’observa de manera més habitual en estudis centrats en l’època contemporània.

En aquest context, el meu objectiu és analitzar la perspectiva transnacional des d’una vessant d’història cultural o sociocultural. Això implica explorar les relacions, trobades, símbols, representacions, interaccions i maneres d’entendre el món durant l’època moderna. En concret, em proposo desgranar les xarxes de mercaders a la Mediterrània occidental per comprendre els seus intercanvis i les seves dinàmiques econòmiques i socials, així com les experiències d’aquests agents en un context de transformació.

Precisament, com explica Bartolomé Yun Casalilla, la perspectiva transnacional ens permet examinar l’impacte d’aquest procés de canvi en els subjectes, els significats que li atorgaren i les seues experiències, en un món on sorgiren noves connexions i oportunitats emmarcades en el moment de dificultats que la historiografia ha assenyalat tradicionalment per al segle XVII. En eixe sentit, cal destacar com els subjectes de la Corona d’Aragó han quedat sovint als marges d’aquestes narratives. Sembla que la Corona d’Aragó oberta al món, emprenedora i poderosa va entrar en declivi en el trànsit de l’època medieval a la moderna i no va tornar a revifar fins al segle XVIII. Si bé aquestes consideracions s’han revisat a casa nostra des dels inicials estudis d’Emili Girlat o Sebastià García Martínez a les més recents aportacions de Jaume Dantí o Patrici Pojada , el seu impacte en la historiografia anglosaxona no ha estat el mateix. Afegir les trajectòries i experiències d’aquest important i vertebral territori de la Mediterrània, així

* Professor d’Història Moderna, Universitat de València

ARTICLE

com incloure’l en les dinàmiques globals de la Monarquia Hispànica, afegeix complexitat a un passat molt més ric i connectat del que la historiografia centrada en els marcs d’anàlisi estatnacionals atorga al període modern.

Arran de la meua tesi doctoral, publicada per la Fundació Noguera, Emprenedors Transnacionals. Les trajectòries econòmiques i socials de les famílies Cernezzi i Odescalchi a la Mediterrània occidental (ca. 1590-1689), i d’algunes recerques posteriors, m’agradaria proposar tres formes d’història transnacional que poden oferir possibilitats d’estudis per observar el passat a partir dels emprenedors.

Xarxes globals a (i des de) la Mediterrània

La importància de les xarxes mercantils mediterrànies en la connexió transregional i global al segle XVII és cada vegada més reconeguda. La trajectòria de les famílies de negocis Cernezzi i Odescalchi exemplifica l’experiència d’una xarxa que evidencia la Mediterrània com un espai on les connexions s’intensificaren, s’arrelaren xarxes ja existents i es crearen noves vies i negocis, presentant uns individus que foren capaços d’adaptar-se a noves conjuntures. Entre els molts exemples que podríem emprar en destacarem dos: el cas dels negocis de la seda i del mercuri.

Els emprenedors de la seda coordinaren desenes de companyies comercials distribuïdes arreu d’Europa per controlar totes les fases de la vida del producte, des del seu inici, comprant la llavor de seda a València, passant per la distribució fins a Gènova, la producció de teixits semielaborats a Milà i a la Toscana, la seua redistribució al centre i nord d’Europa i la seva venda a places com Sevilla o Amsterdam. També des d’Oaxaca, companyies d’italians en connexió amb els Cernezzi exportaren cotxinilla per tenyir teixits als centres italians.

Aquesta dinàmica, que articulava informació i pràctica a nivell transregional, matisa la idea d’una Mediterrània aïllada i mostra la participació activa dels seus emprenedors en els canvis econòmics a (i des de) la Mediterrània cap a altres parts d’Europa i el món, desbordant les connexions en un espai geogràfic autoreferencial. Milanesos sense accés directe al mar, juntament amb altres mercaders, es van integrar a les xarxes mercantils creant la possibilitat de portar a terme grans i importants negocis que impactarien de maneres molt diverses a nivell local.

En eixa direcció, un altre exemple és el comerç del mercuri, clau per a l’extracció d’argent americà i que va afectar directament enclavaments econòmics, com el port de Venècia. Al segle XVII, les mines d’Idrija a Eslovènia van ser gestionades per xarxes d’italians que connectaven Idrija, Venècia i Sevilla, fent arribar el mercuri, l’argento vivo, a Amèrica.

La República de Venècia, negociant amb els diferents arrendadors italians de les mines d’Idrija, buscava atreure el tràfic del mercuri per estimular el comerç marítim i augmentar els ingressos fiscals. Tot i les mesures aplicades, com reduccions aranzelàries, i les diferents pressions entre institucions i magnats del mercuri, el desplaçament d’aquest comerç cap a altres rutes va afectar 2

greument l’economia veneciana, provocant també una desconnexió. Seguir el procés de presa de decisions entre diferents seus de les companyies, així com per part de les institucions, ens porta a comprendre el funcionament de l’economia des del cor de les mateixes empreses, observant el poder, el rol social i cultural i l’impacte de les decisions davant d’un món que atenia a transformacions i noves exigències globals per a prendre decisions locals. En síntesi, els agents mediterranis no només connectaven regions, sinó que transformaven les dinàmiques econòmiques globals, posant de manifest la seva rellevància en el context de la primera globalització.

Les comunitats d’emprenedors i la confiança transnacional

Més enllà de la creació, l’articulació i el maneig de xarxes que permetien moure productes a nivell global, m’interessa destacar com la perspectiva transnacional ajuda a comprendre les dinàmiques entre les diferents companyies mercantils ―de no més de dos o tres socis―, fins i tot quan es tractava d’emprenedors que no es coneixien entre ells. Així doncs, observarem dos exemples: un del treball a l’àmbit local i un altre a un nivell més interregional.

Les relacions de negocis van entrellaçar agents de diverses comunitats. En un àmbit local com el valencià, aquestes relacions revelen la dimensió transnacional del comerç, amb la participació de milanesos, genovesos, francesos, anglesos, alemanys, irlandesos, valencians i catalans. Les recerques recents destaquen una densa presència de francesos, especialment durant els anys 1630. Aquesta comunitat, amb el marcat caràcter juvenil dels seus integrants, va aportar innovacions en la producció tèxtil i va aprofitar oportunitats econòmiques latents. Per exemple, el 1635, malgrat els embargaments contra la seua comunitat en el marc de la Guerra dels Trenta Anys, els seus membres van rebre suport d’altres comunitats, com els milanesos i valencians, que fins i tot van refusar quedar-se amb els seus negocis i van avalar les seues companyies davant de les institucions. Això reflecteix una col·laboració activa i una certa protecció comunitària i institucional.

Confiar era imprescindible en el joc econòmic en què la distància i la pluralitat d’agents de diferents «nacions» marcava la quotidianitat. La confiança jugava un paper clau en aquestes xarxes, no només des d’un punt de vista racional, institucional o cognitiu, sinó també en la seua dimensió emocional. Tot i els enganys, les malversacions o els conflictes, la confiança podia reeixir gràcies a factors com la reputació, l’amistat, els lligams familiars o la gestió de les emocions. Per exemple, al voltant del 1637, la companyia dels Cernezzi es va veure afectada per tensions internes quan Pietro Martire, a Venècia, va prendre decisions sense consultar els socis. Malgrat els rumors i les tensions, els vincles familiars, l’afecte pels nebots i el paper rellevant de la companyia a Venècia van fer que la confiança s’hagués de recompondre.

La gestió emocional era essencial per evitar ruptures en relacions que generaven beneficis econòmics. Aquesta qüestió s’observa en casos com el de Giovanni Battista Benzi, agent d’Amsterdam, el to impertinent del qual alterava altres socis. Els Odescalchi, des de Gènova, intentaven calmar els ànims, destacant la importància d’una gestió emocional per preservar la col·laboració. Les cartes comercials no només transmetien informació, sinó també emocions, reflectint alegria, ansietat o frustració davant de l’èxit o el fracàs de les operacions.

Francesco Cernezzi, des de Venècia, afirmava que conèixer en persona els seus socis hauria evitat enganys. No obstant això, fins i tot a distància, era possible construir un sistema de confiança emocional a través del llenguatge escrit. Les fórmules d’etiqueta, els apel·latius i el to transmetien personalitat i passions, revelant un equilibri entre racionalitat i emoció en les complexitats del comerç mediterrani. Aquesta combinació resulta fonamental per comprendre com es van sostenir relacions duradores en un context d’intercanvis transregionals, comptes i interessos creuats.

La representació del món global i la literatura de viatges Als testaments, així com en els seus poders, els mercaders solien incloure la reclamació dels seus deutes a «Espanya, Itàlia i qualsevol altra part del món». Conscients de viure en un món en expansió, sabien que els seus interessos es distribuïen en una globalitat que no només era econòmica, sinó també cultural. És per això que, en darrer terme, m’agradaria apropar-me al món percebut, simbòlic i imaginat del món global a partir de les lectures que circulaven sobre la mundialització i els discursos expressats pels propis mercaders que viatjaren arreu del món.

A les seves llars, conservaven mapes i representacions del món, així com béns procedents de regions llunyanes com cotxinilla, porcellana, mobles de fusta de la Índia i pebre negre. A les seves biblioteques s’hi trobaven llibres sobre la història del món i relats de viatges, com en el cas de Manuel Cernezzi, que atresorava una cinquantena de llibres relatius a històries, viatges i descripcions de diferents parts del món extraeuropeu. Per entendre com percebien aquest món global, vaig analitzar els títols de les seves biblioteques i em vaig endinsar en la literatura de viatges escrita per mercaders o amb referència a activitats mercantils , un gènere que reflecteix tant experiències individuals com col·lectives, així com un dispositiu cultural que creava un imaginari sobre la globalitat, tal com ho han referit autors com Joan Pau Rubiés o Juan Pimentel.

La literatura de viatges de l’època era profundament transnacional. Autors portuguesos, espanyols, italians i holandesos utilitzaven formes similars per narrar els seus viatges a finals del segle XVI i principis del XVII. Entre aquests autors, m’he centrat en aquells que, almenys en algun moment, es definien com a mercaders: Pedro Ordóñez de Ceballos, de Jaén, i Francesco Carletti, de Florència, que van escriure sobre les seves voltes al món. També estic incorporant els relats del portuguès Fernâo Mendes Pinto i del mercader holandès Jacob Le Maire, expulsat de la Companyia Neerlandesa de les Índies Orientals (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie) Alguns d’ells tingueren diferents traduccions, apareixien conjuntament en compendis i empraven el mateix règim de veracitat per dotar els textos de versemblança.

Aquests textos, a més, reflecteixen una cultura híbrida per diversos motius. D’una banda, pel valor atorgat al descobriment individual del món, una idea que es consolidà a finals del segle XVI. Navegar sense suport estatal o missioner, comerciar i descobrir eren accions que reivindicaven el poder dels mercaders. A través dels seus relats, aquests comerciants cercaven dignificar la seva professió, sovint desacreditada per acusacions d’usura, i alhora, de l’altra banda, com ha subratllat Giuseppe Marcocci, donaven significat al món global en què participaven, la qual cosa era agraïda per la població europea, àvida de notícies. 4

Els relats de viatges poden ser interpretats com narracions heterotòpiques, en què es tracten múltiples temàtiques, però especialment la mundialització. Encara que alguns textos, com els de Carletti, són profundament mercantils, combinen història, descripció de mercaderies, aproximacions antropològiques i representacions dels gèneres, feminitats i masculinitats clau per construir un «relat del món» integrador, però alhora profundament jerarquitzat.

Aquestes produccions literàries són cabdals per entendre, precisament, les jerarquies de poder global i la diferència colonial des d’una perspectiva cultural. Els relats no només descrivien un món econòmic i material, sinó que el (re)significaven, establint un discurs que mesclava exploració, comerç i poder amb les dinàmiques de gènere i la representació de l’altre. Aquesta és la construcció simbòlica que m’interessa analitzar: com aquests textos transformaren la idea del món en una narrativa de significats globals. Un món global que era alhora viscut i representat a i des de la Mediterrània.

THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA REGION’S GREENISATION: A COMPARATIVE OUTLOOK

ARTICLE

In the last two decades, an institutional greenisation process has incrementally made its way into the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Greenisation is understood here as a policy shift that incorporates environmental ideas and ideals into the state fabric by crafting ad hoc regulatory, administrative, financial, and knowledge structures and encompasses both domestic and foreign policy arenas (Cimini, 2024). Despite much earlier yet scattered environmental initiatives, a more committed and distinctive openness and receptiveness to green standards and goals is indeed a recent endeavor representing a noteworthy change of pace in a well-known history of resistance and obstructionism to climate action.

National strategies prioritizing renewables and energy efficiency supported by official discourse, the proliferation of environment-devoted laws and institutions (from ministries to agencies to foundations and councils), and a proactive engagement on the international stage such as hosting the Conference of Parties (COP) and forging new partnerships, provide compelling evidence of an ongoing transformation. As in previous environmental actions, this process is also far from linear and without contradictions, featuring some key traits.

The first is a reversed historical trend in global emissions and emissions per capita. The MENA region’s greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint is lower than in other regions worldwide, standing at around 8 percent. However, if we turn to the emissions per person, since the mid-1990s, the regional average has consistently exceeded the world average (Climate Watch Data, 2025a). Moreover, global emissions have tripled in the past three decades, with a growth rate almost equal to those of East Asia and the Pacific. This troubling pattern enhances (some) Arab countries’ ‘negative’ environmental power internationally, making their engagement towards environmental sustainability even more needed.

Second, energy transitions take the lion’s share in MENA’s greenisation, discursively and through flagship initiatives already in place or in the making. Noor I, the world’s largest single-site concentrated power plant located on the Sahara’s doorstep in Morocco, smart cities like Abu Dhabi’s pioneering Masdar City, or NEOM on the Red Sea are the best-known examples meant to embody a heavily touted green turn. Remarkably, these ‘visionary’ initiatives are firmly rooted under the aegis of the state’s highest ranks. Saudi King Muhammad Bin Salman, Emirati President Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, and Moroccan King Mohammed VI are particularly

* Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Political and Social Sciences, Università di Bologna

ARTICLE

Giulia Cimini*

vocal in sponsoring environmental sustainability. In other words, mainstream environmental narratives and projects, mainly equating with renewables and mega-projects, are heavily topdriven and focused on investment in new technologies and facilities. Against this shining backdrop, however, it is especially the dimension of social justice with fairness and equity that, while being a fundamental pillar of ecological transitions, remains largely overshadowed, if not completely missing.

Thirdly, greenisation, net of some common trends, is proceeding at different speeds from country to country, mirroring different interests, capacities and capabilities. It is never trivial to reaffirm that thinking ‘regionally’ should not lose sight of profound internal heterogeneity in environmental policies and politics, as indeed is the case for strikingly diverse colonial histories, unique local cultures, distinct political systems, and disparate economic characteristics. Although the twenty-two members of the Arab group usually act and negotiate together at the COPs, every country is at a different point in its journey towards sustainability and green transitions. So, whereas in the ‘east’ a regional heavyweight such as Saudi Arabia aims at frontrunning the green transition in competition with an earlier environmental advocate like the United Arab Emirates (Zumbrägel, 2022), in the ‘west’, Morocco plays its cards through its green diplomacy, leveraging on consolidated relationships with Europe and pivoting to Africa. The others follow or lag behind. According to the Arab Future Energy Index monitoring and analyzing sustainable energy competitiveness in the Arab region, the countries’ cumulative target of 190 GW of renewable energy capacity set by 2035 is expected to account for as much as 30 percent of global growth in renewable energy. Zooming in on the many countries, however, one learns that individual renewable energy targets for overall electricity generation vary, with Bahrain setting a target as low as 5 percent by 2025 – which is second only to Qatar in terms of emissions per capita (Climate Watch Data, 2025b) – and Morocco aiming for as high as 100 percent by 2050. Likewise, only seven countries, mainly in the Gulf, have committed to achieving net-zero goals by (UAE, Oman, and Tunisia) or around mid-century (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Morocco).

That said, what are the drivers of such a policy change? Economic profitability, yet motivated by environmental protection and sustainable development, is the general reading of the MENA region’s policy shift. Diversification aimed at maintaining competitiveness in what is often referred to as a ‘post-oil’ era is an asset for major Arab fossil-fuel producers. Indeed, it is explicitly acknowledged and deemed ‘vital’ for the economy’s sustainability in national strategies or ‘visions’ like that of Saudi Arabia (Vision 2030). Likewise, for hydrocarbon resource-poor countries, renewables might be profitable alternatives to lowering extremely high levels of energy dependency. Again, Morocco is a case in point because, despite significant efforts in the last fifteen years, it remains a net energy importer (91 percent of the total energy supply). This underscores how greenisation takes time to bear fruit, should it need to, beyond the spotlight.

Changing international attitudes toward climate action had its own influence as an exogenous factor. The push to reduce the global demand for hydrocarbons worked as both a threat and an incentive. In this regard, the European Union (EU)’s green calls and policy orientation across 2

the ‘wider’ Mediterranean, not least following the adoption of the European Green Deal (EGD) in 2019 and the REPowerEU strategy meant to be the new roadmap to overcome dependency on Russian fossil fuels rapidly after the outbreak of the war on Ukraine, are indicative. Albeit amid increasing competition, the EU remains a key trading partner for many Arab countries. European or bilateral initiatives of individual member states with MENA countries on energy issues are the order of the day. However, in October 2022, ahead of COP27, the EU and Morocco signed an unprecedented Green Partnership to advance the external dimension of the EGD. The agreement, which provides a political framework rather than new financial tools, is the first such initiative to be signed with a non-EU country, thus a harbinger far beyond the MENA region, and is expected to become a model for similar partnerships with other countries.

Shifting domestic needs and global energy markets, coupled with the sense of urgency associated with a high vulnerability to the effects of climate change, all play a role, as does the extrinsic value of ‘greening’ the country to increase regional and international leverages. In this respect, the quest for international prestige and modernity also drives this shift towards a greener state architecture.

A mixture of constraints and consideration of political and economic opportunities thus lies at the heart of greenisation, which is gradually expanding geographically in the region. However, it is worth wondering to what extent this shift is broadening to domains other than decarbonization to embrace wider environmental protection and deepening domestically to include bottom-up priorities and local communities’ needs. Likewise, whether we can talk about a norm-diffusion effect, which also implies the interiorization of green standards and principles as a norm with intrinsic value, is far from evident.

Bibliographical references

C IMINI, G. (2024) ‘Greening the Mediterranean: North Africa and Middle East’s Pathways to Environmental Policy’, in Calandri, E. et al. (eds.) Routledge Handbook on Cooperation, Interdependencies and Security in the Mediterranean. London: Routledge, pp. 355–368.

C LIMATE WATCH DATA (2025a) Global Historical Emissions (per capita): MENA vs. World. https://www.climatewatchdata.org/embed/ghg-emissions?breakBy=regions&calculation= PER_CAPITA&chartType=line&end_year=2019®ions=WORLD%2CMNA§ors=totalincluding-lucf&start_year=1990

C LIMATE WATCH DATA (2025b) Global Historical Emissions (per capita): MENA countries. https://www.climatewatchdata.org/embed/ghg-emissions?calculation=PER_CAPITA&chart Type=line&end_year=2019®ions=MNA§ors=total-including-lucf&start_year=1990

Z UMBRÄGEL, T. (2022) Political Power and Environmental Sustainability in Gulf Monarchies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

ARTICLE

n.175 12/03/2025

MIGRACIONES F EMENINAS INTERNACIONALES Y DERECHOS HUMANOS EN PAÍSES DE LA UNIÓN EU ROPEA. DESAFÍOS Y APORTES PARA LA GO

BERNABILIDAD DEMOCRÁTICA

Teresa Terrón-Caro*

Las migraciones internacionales se configuran como procesos sociales dinámicos y en constante evolución, caracterizados por su alta complejidad, naturaleza bidireccional y múltiples factores intervinientes (Naïr, 2016). Su relevancia en el contexto actual no radica en su historicidad, sino en su capacidad de adaptación y transformación frente a cambios globales (Terrón-Caro & Campani, 2022). Este dinamismo se manifiesta a través de dimensiones interrelacionadas, tales como: la evolución de perfiles migratorios —con fenómenos como la feminización de los flujos—, geografías fluctuantes, políticas de respuesta adaptativas —ante presiones geopolíticas o demográficas—, estrategias migratorias renovadas, etc.; contribuyendo todas ellas a transformaciones estructurales significativas en sociedades de origen, tránsito y destino.

Si bien el protagonismo femenino como eje transformador es clave, no siempre se ha tenido en consideración. Según el Informe sobre las Migraciones en el Mundo 2022 y el Informe sobre las Migraciones en el Mundo 2024 (OIM), el 3.6% de la población global (281 millones) reside fuera de su país de nacimiento, con un 48% de participación femenina (ONU Mujeres, 2023). Su participación no solo refleja un cambio cuantitativo, sino cualitativo: emergen como agentes activas en redes migratorias y como sujetos con incidencia socioeconómica multidimensional (laboral, cultural, política, educativa). Este giro paradigmático exige repensar críticamente las políticas y prácticas de integración-inclusión desde enfoques interseccionales que reconozcan al género como categoría clave de análisis, siendo eje estructurante de las trayectorias migratorias.

Bajo estas premisas, la conferencia «Migraciones femeninas internacionales y Derechos Humanos en países de la Unión Europea. Desafíos y aportes para la gobernabilidad democrática» tiene como objetivo principal analizar el desafío social que representan las migraciones, con énfasis en los flujos femeninos dentro del contexto europeo actual. Para ello, se adopta un enfoque que integra perspectivas de género, interseccionales, multidimensional, multiescala y de Derechos

Humanos, examinando los procesos de inclusión-exclusión social y las políticas de gobernanza migratoria, desde un análisis crítico, en seis países de la Unión Europea.

El soporte teórico-metodológico se fundamenta en investigaciones desarrolladas bajo la línea «Migraciones, derechos humanos y educación: procesos migratorios, inclusión, participación social y gestión de la diversidad cultural» enmarcada en el Grupo de Investigación

* Presidenta de la Sociedad Española de Educación Comparada y profesora titular del departamento de Educación y Psicología Social, Universidad Pablo de Olavide de Sevilla

en Acción Socioeducativa (GIAS), adquiriendo especial relevancia el proyecto Erasmus + Voices of Immigrant Women (2020-1-ES01-KA203-082364), cuyo diseño metodológico y principales resultados se presentan como eje analítico de este artículo.

Voices of Immigrant Women: Diseño metodológico

El Proyecto Erasmus + Voices of Immigrant Women (VIW), cofinanciado por la Unión Europea bajo la acción Asociaciones Estratégicas en el sector de Educación Superior (KA203) (20202022), ha sido coordinado por la Universidad Pablo de Olavide (España) y ha involucrado a un total de ocho instituciones de seis países europeos: España, Francia, Portugal, Italia, Grecia y Eslovenia. Su objetivo principal ha consistido en analizar las iniciativas de integración e inclusión de mujeres migrantes conociendo cómo se implementaron, el nivel de colaboración multiactor —sinergias entre sector público, sociedad civil y academia— y el impacto producido —efectos en el acceso a derechos, autonomía económica, participación social y cohesión comunitaria—, entre otros.

Para abordar la complejidad interdisciplinar y holística del fenómeno migratorio se ha adoptado un diseño de estudio de casos múltiples (Stake, 2020). Este método se basa en el examen sistemático, contextualizado y en profundidad de realidades multifactoriales. Cada país participante ha funcionado como una unidad de análisis primaria, integrada por diversos subelementos de análisis (individuos o grupos, unidades geográficas y productos generados — políticas, publicaciones, estadísticas—) y en cuatro niveles de concreción que se interrelacionan entre sí: microperspectiva, mesoperspectiva, exoperspectiva y macroperspectiva. Dicho planteamiento se realiza de acuerdo con la propuesta metodológica para la investigación de las migraciones del Instituto Internacional de Integración (Moreno, 2013), así como con una adaptación del modelo ecosistémico aplicado a procesos migratorios de Falicov (2008).

La relevancia metodológica radica en su diseño bottom-up, que sitúa a las mujeres migrantes como sujetos activos en la producción del conocimiento a través de narrativas situadas (Haraway, 1988), combinado con un enfoque multiactor que integra cuatro tipos de agentes clave:

- Comunidad académica: personal investigador, profesorado universitario y alumnado de grado/postgrado en disciplinas vinculadas a ciencias sociales, trabajo social, derecho, salud y educación.

- Sociedad civil: ONG y entidades especializadas en migración femenina.

- Sector público: Representantes de instituciones de Educación Superior, de administraciones locales y nacionales con competencias en políticas migratorias y en el ámbito educativo.

- Profesionales en activo: Agentes sociales, mediadores interculturales y personal de atención directa.

A su vez, se han utilizado una gran diversidad de técnicas cualitativas de recogida de información: Análisis Documental; 1 Focus Group por país (6 en total) a actores clave — profesionales que trabajan con mujeres migrantes—; 1 Panel Delphi con 3 rondas a expertas y expertos en la temática a nivel nacional e internacional; 67 entrevistas en profundidad a mujeres 2

migrantes en los países que participan en el proyecto. A nivel cuantitativo, se ha aplicado una encuesta dirigida a mujeres migrantes que residen en las zonas geográficas identificadas en cada país.

Principales resultados del proyecto

Esta triangulación metodológica valida tanto los saberes experienciales como los marcos teórico-normativos, generando una cartografía crítica de las migraciones femeninas que nos ha permitido revelar las agencias, resistencias y contribuciones de las mujeres migrantes que han participado en el proyecto VIW, así como las violencias estructurales a las que se enfrentan y las desigualdades de género existentes.

Tras la sistematización, análisis e interpretación de la información recogida durante el desarrollo del proyecto, se han diseñado los siguientes resultados:

• Mapa de Estudios de Casos de Integración e Inclusión de Mujeres Migrantes en España, Italia, Portugal, Francia, Grecia y Eslovenia

Este instrumento analítico sistematiza 67 estudios de caso transnacionales, centrados en experiencias exitosas de integración lideradas por mujeres migrantes. Cada caso se ha organizado mediante un esquema de análisis multidimensional que incluye:

1. Marco institucional: Actores implicados y tipología de iniciativas.

2. Estrategias de agencia migrante: resiliencia, prácticas culturales transnacionales (identidades complejas), historial personal.

3. Impacto estructural: transformaciones cualitativas, incidencia política, resultados… De forma complementaria se ha diseñado un cuadro de yuxtaposición a nivel transnacional e interdisciplinario en el que se examinan de forma resumida los diferentes ámbitos analizados durante el trabajo de campo en los contextos de estudio.

• Plan de Aprendizaje E-learning sobre Migraciones, Género e Inclusión en el Contexto Europeo: Un enfoque Interdisciplinario

Este instrumento es un programa formativo en línea de acceso abierto que tiene como objetivo central fortalecer las competencias críticas de alumnado universitario, agentes sociales, profesionales y futuros especialistas en migraciones, mediante una aproximación que combina teoría crítica y praxis transformadora. Alineado con el triple compromiso universitario —docencia, investigación e impacto social—, busca contrarrestar problemáticas estructurales como: discriminación interseccional y segregación espacial, racismo institucional y violencia de género racializada, así como desigualdades en el acceso a derechos fundamentales (salud, educación, participación política).

Los contenidos están organizados en 8 módulos y cada módulo tiene una doble dimensión: una transnacional y otra nacional. La formación se basa en la teoría y la práctica.

• Libro de Recomendaciones Políticas. Migraciones, Género e Inclusión desde una perspectiva Internacional

Este documento estratégico ofrece directrices operativas basadas en evidencia para actores clave en gobernanza migratoria y educación superior, con el fin de transformar

las políticas públicas mediante un enfoque interseccional y de derechos humanos. Está dirigido a personas con responsabilidades políticas en la gobernanza sobre gestión migratoria y políticas para la integración e inclusión social, así como a liderazgos universitarios —equipos rectorales, diseñadores y diseñadoras de planes de estudio y comités de responsabilidad social.

Su objetivo central es favorecer la construcción de instituciones, administraciones y, en definitiva, sociedades más inclusivas que eliminen barreras sistémicas para las mujeres migrantes, articulando cuatro ejes temáticos:

1. Necesidades de las mujeres migrantes e intervenciones de integración exitosas.

2. Promover la sensibilización del estudiantado universitario y la responsabilidad cívica y social hacia la integración de las mujeres migrantes.

3. Cooperación entre instituciones de educación superior y del tercer sector.

4. Educación superior inclusiva. Este enfoque, alineado con los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS 5, 10 y 16) y el Pacto Mundial para Migraciones Seguras (ONU, 2018), subraya el carácter aplicado del documento, convirtiéndolo en una herramienta para la rendición de cuentas y el cambio estructural.

Consideraciones finales

A modo de cierre, cabe destacar que los recursos generados —elaborados desde una perspectiva interdisciplinar, internacional, de género y derechos humanos, disponibles en seis idiomas y de acceso abierto— sintetizan un diseño metodológico innovador que combina procesos participativos en la construcción del conocimiento con una mirada multinivel: global, nacional y local. Este enfoque, que prioriza el género como categoría analítica central y reconoce la interseccionalidad inherente a los fenómenos migratorios, permite abordar la complejidad multidimensional de las migraciones mediante análisis contextualizados en realidades culturales específicas. La triangulación de investigación, intercambio, formación y cooperación —articulada bajo un compromiso ético-político con la justicia social— busca trascender la mera descripción académica para impulsar una gobernanza migratoria transformadora. Este modelo, al integrar evidencias empíricas, marcos normativos y narrativas situadas, aspira a catalizar cambios estructurales que materialicen el principio de «no dejar a nadie atrás» en las políticas públicas. Para ello, redefine la cooperación y la coparticipación como herramientas fundamentales para promover la equidad epistémica y fortalecer la acción colectiva.

Referencias Bibliográficas

FALICOV, C. (2008). «El trabajo con inmigrantes transnacionales: Expandiendo los significados de familia, comunidad y cultura». Revista Redes, 1(20).

HARAWAY, D. (1988). «Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective». Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

I NTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR M IGRATION. (2022). Informe sobre las migraciones en el mundo 2022 https://publications.iom.int/books/informe-sobre-las-migraciones-en-el-mundo-2022

I NTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR M IGRATION (2024). Informe sobre las migraciones en el mundo 2024. https://publications.iom.int/books/informe-sobre-las-migraciones-en-el-mundo-2024

M ORA M ORENO, D. (2013). «Metodología para la investigación de las migraciones». Integra Educativa, 6(1), 13–41.

NAÏR, S. (2016). Refugiados: Frente a la catástrofe humanitaria, una solución real. Crítica.

PORRAS RAMÍREZ, J. M., & R EQUENA DE TORRE, M. D. (Eds.). (2021). La inclusión de los migrantes en la Unión Europea y España: Estudio de sus derechos. Thomson Reuters Aranzadi.

TERRÓN-CARO, T., & CAMPANI, G. (2022). Presentación [Editorial]. Cuestiones Pedagógicas: Revista de Ciencias de la Educación, 31(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.12795/CP.2022.i31.v1.00

STAKE, R OBERT E. (2020). Investigación con estudios de casos (sexta edición) Morata. Madrid.

U NITED NATIONS (1981). Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/professionalinterest/cedaw.pdf

U NITED NATIONS (2018). Pacto mundial para la migración segura, ordenada y regular. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/sites/default/files/180711_final_draft_0.pdf

ARTICLE

DISMANTLING GREEN (N EO)COLONIALISM: ENERGY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE IN THE ARAB REGION

n.176 25/04/2025

The reality of climate breakdown is already visible in North Africa and the Arab region, undermining the ecological and socioeconomic basis of life. Addressing this global climate crisis requires a drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and a rapid transition towards renewable energies. However, there are potential risks and dangers that such a transition would maintain the same practices of dispossession and exploitation that currently prevail, reproducing injustices and deepening socioeconomic exclusion.

Every year, the world’s political leaders, advisers, media and corporate lobbyists gather for another United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP) on the issue of climate change. But despite the threat facing the planet, governments continue to allow carbon emissions to rise and the crisis to escalate. After three decades of what the Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg has called ‘blah blah blah’, it has become evident that these climate talks are bankrupt and are failing. They have been hijacked by corporate power and private interests that promote profit-making false solutions, like carbon trading and so-called ‘net-zero’ and ‘nature-based solutions’, instead of forcing industrialised nations and fossil fuel companies to reduce carbon emissions and leave fossil fuels in the ground.

With COP28 held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), between 30 November and 12 December 2023, the Arab region had hosted the climate talks five times since their inception in 1995. COPs attract massive media attention but tend not to achieve major breakthroughs. COP27, held in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022, achieved an agreement on Payment for Loss and Damage that has been lauded by some as an important step in making richer countries accountable for the damage caused by climate change in the global South. However, as the agreement lacks clear funding and enforcement mechanisms, critics worry it will meet with the same fate as the broken promise (first made in COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009) to provide $100 billion in climate finance by 2020. As for COP28, the UAE’s appointment of Sultan alJaber, CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, to preside over the talks seems to many activists and observers to symbolise the deep commitment to continued oil extraction, regardless of the cost, which has characterised negotiations to date.

* Researcher at the Transnational Institute. He is the co-editor of Dismantling Green Colonialism: Energy and Climate Justice in the Arab Region (Pluto Press, October 2023)

ARTICLE

Hamza Hamouchene*