VOLUME THIRTY-FOUR

V.35 FEBRUARY 2026

2026 Winter Issue

VOLUME THIRTY-FOUR

V.35 FEBRUARY 2026

2026 Winter Issue

HISSN 2837-5696

HYDROVISIONS is the official publication of the Groundwater Resources Association of California (GRA). GRA’s mailing address is 808 R Street. Suite 209, Sacramento, CA 95811. Any questions or comments concerning this publication should be directed to the newsletter editor at hydrovisions@grac.org

The Groundwater Resources Association of California is dedicated to resource management that protects and improves groundwater supply and quality through education and technical leadership.

EDITOR

Rodney Fricke hydrovisions@grac.org

EDITORIAL LAYOUT

Smith Moore & Associates

EXECUTIVE OFFICERS

PRESIDENT

Erik Cadaret

Yolo County Flood Control & Water Conservation District

VICE PRESIDENT

Abhishek Singh INTERA

SECRETARY

Abhishek Singh INTERA

TREASURER

Marina Deligiannis

Sacramento Area Sewer District

DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION OFFICER

Annalisa Kihara

State Water Resources Control Board

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Christy Kennedy

Woodard & Curran

ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR

Amanda Rae Smith

Groundwater Resources Association of California

To contact any GRA Officer or Director by email, go to www.grac.org/board-of-directors

DIRECTORS

Jena Acos

Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck

Christopher Baker

CA DWR

Matthew Becker

California State University Long Beach

Trelawney Bullis

AC Foods, Central Valley

Dave Ceppos

Public Policy Mediation and Facilitaion

Elie Haddad

Haley & Aldrich

Dr. Hiroko Hort

GSI Environmental, Inc

Len Mason

Geosyntec Consultants, Inc.

Clayton Sorensen

West Yost Associates

Melissa Turner

MLJ Environmental

Savannah Tjaden

Environmental Science Associates

Roohi Toosi

APEX Environmental & Water Resources

R.T. Van Valer

The statements and opinions expressed in GRA’s HydroVisions and other publications are those of the authors and/or contributors, and are not necessarily those of the GRA, its Board of Directors, or its members. Further, GRA makes no claims, promises, or guarantees about the absolute accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of the contents of this publication and expressly disclaims liability for errors and omissions in the contents. No warranty of any kind, implied or expressed, or statutory, is given with respect to the contents of this publication or its references to other resources. Reference in this publication to any specific commercial products, processes, or services, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for the information and convenience of the public, and does not constitute endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the GRA, its Board of Directors, or its members.

Message Page 4

and Emergence Maps Page 6

Basin Characterization Page 14

on Tribal History Page 20 Reflections from the C hair Page 24 GeoH2OMysteryPix Page 28

Parting Shot Page 30

6 Groundwater Rise and Emergence Maps –Uncertainties, Limitations, and Appropriate Uses

14 DWR’s Basin Characterization Program: Groundwater Investigations at the Statewide, Regional, and Local Scales

20 Reflections on California Tribal History, Relationship Building, and Engagement Training

*can i Get a “wooH!”?=]*

Hello GRA Family, Friends, and Groundwater Super Fans!

I am thrilled to step into the role of GRA President for 2026 and 2027. I’m eager to embrace the opportunities and challenges ahead of our organization and industry, collaborating with the incredible people who make GRA what it is. We have a proud history of leading the way, setting high standards, and embodying our mission, vision, and values—including a commitment to equity and inclusion—through engaging programs that serve our diverse groundwater community. In my first President's message, I’d like to share my vision for what’s on the horizon for GRA and our industry.

GRA-Related Developments

Under Christy’s strong leadership as past GRA President and with the Board’s support from 2024–2025, we made significant progress by developing a focused strategic plan, which centers on two priorities: 1) expanding and engaging our membership and 2) bolstering our industry leadership through enhanced offerings and stronger partnerships with other organizations that reflect diverse interests and perspectives.

We’re now building a targeted marketing plan to better articulate our value and increase member involvement, ensuring equitable access to our resources. This plan should not only enrich benefits for existing members but also draw in new ones, fostering substantial growth over time. Equally exciting is our push to expand strategic partnerships with affiliate groups, enabling us to champion industry-wide solutions.

A prime example came from our October 2025 Contemporary Groundwater Issues Council (CGIC) meeting—a think tank where industry thought leaders from diverse backgrounds discuss pressing challenges candidly. Participants agreed on a forward-thinking proposal: GRA should facilitate dialogues among state, local, and federal agencies, along with legislative staff. By drawing on our technical expertise and varied perspectives, we can shape future policies that ensure equitable groundwater management, establishing GRA as an essential partner in capitol-level decision-making.

On a personal note, I believe our talented Board can achieve remarkable things together. I’m excited to work with these industry leaders to build deeper connections, camaraderie, and alignment with our members—opening up more ways for you to engage and support GRA’s initiatives. Over the next two years, you’ll hear from not just me, but the entire Board. We want to get to know you better, too!

Our sector is navigating a shifting regulatory environment, skilled labor shortages, and escalating costs—challenges that require innovative solutions from landowners, homeowners, public agencies, and private companies. These issues can feel overwhelming at times, but I’m optimistic about the future, especially if we prioritize equity to ensure benefits to all communities.

AI advancements are already boosting productivity dramatically. As a public agency employee, I’ve experienced how tools like Claude can create Python scripts for complex analyses in minutes—what used to take hours or days just five years ago. The possibilities for creative applications are endless, and I know many of you feel the same! AI can optimize tasks from regulatory reviews to staff training, work planning, and even tools for greater transparency and knowledge sharing between agencies, boards, and the public, all while cutting costs without sacrificing quality. I see AI as a game-changer for our industry, particularly in the public sector, helping us achieve more with fewer resources, advance sustainability goals, and promote equitable access to groundwater resources for underserved communities.

Moving forward, GRA can harness our creative, passionate members to pioneer these innovations. I’m energized by what we can accomplish with your involvement. How can you contribute? Share your ideas and feedback—let’s co-create GRA’s future. Together, we’ll guide the groundwater community toward a more innovative, resilient era that delivers lasting value to our diverse communities!

by Jason Gurdak, Santa Clara Valley Water District

Groundwater Rise and Emergence in California’s Coastal and Baylands Systems

Groundwater rise and emergence at land surface is a growing global concern among the wide-ranging impacts of climate change and sea-level rise (SLR) on groundwater resources (Green et al., 2011; Treidel et al., 2012). While rising sea levels may exacerbate seawater intrusion in overdrafted coastal aquifers (Zamrsky et al., 2024), they can also cause groundwater levels to rise, potentially emerging at land surface (Bosserelle et al., 2022).

Groundwater rise has the potential to damage subsurface structures, such as building foundations, basements, underground parking structures, septic systems, sewer lines, and other underground utilities. Groundwater emergence could affect land use and planning by temporarily or permanently flooding roadways and transportation corridors, above-ground structures, and other utilities. Hill et al. (2023) suggest that groundwater rise and emergence could mobilize subsurface contaminants. Some studies have warned that groundwater emergence could occur years to decades before marine inundation and shoreline overtopping from SLR (Habel et al., 2024).

In one of the first California studies, Hoover et al. (2017) identified coastal areas vulnerable to SLR-driven groundwater rise and emergence. They used a geographic information system (GIS)-based modeling approach to compare the existing highest water table map to land surface elevation, assuming groundwater will rise as a linear (1:1) response to future sea-level rise. Applying this GIS approach, Plane et al. (2019) presented a rapid assessment to map SLR-driven

groundwater rise and emergence. These studies assumed unconfined aquifers that are directly connected to the ocean or bay and a spatially uniform 1:1 response between SLR and groundwater rise. Several San Francisco Bay Area studies have adopted this GIS approach to estimate existing and future groundwater rise and emergence (e.g., May et al., 2020; 2022). News outlets subsequently have relied on these maps to illustrate the growing concerns over groundwater rise and emergence (e.g., KQED, 2024; San Francisco Examiner, 2024). This article uses a 2025 study in Santa Clara County, California to highlight some uncertainties and limitations that could affect how users interpret and apply these types of maps.

Santa Clara Valley Water District (Valley Water) is the Groundwater Sustainability Agency for the Santa Clara Subbasin, which is adjacent to South San Francisco Bay (Bay) in Santa Clara County. Valley Water conducted a multi-year study to better understand the impacts of tides, seawater intrusion, and SLR on groundwater rise and emergence in the Santa Clara Subbasin (Gurdak et al., 2025).

To maintain consistency with the previous studies, Valley Water used similar GIS methods with spline interpolation and the 1:1 response assumption to generate maps of existing and future highest groundwater conditions and emergence under a range of SLR scenarios. Advancing this approach, Valley Water conducted extensive validation using independent groundwater levels, field observations during several king tides, and evaluated the effects of different GIS interpolation methods on map uncertainty. The study methods are detailed in Gurdak et al. (2025), and major findings are also summarized in Gurdak (2025a; 2025b) and as follows.

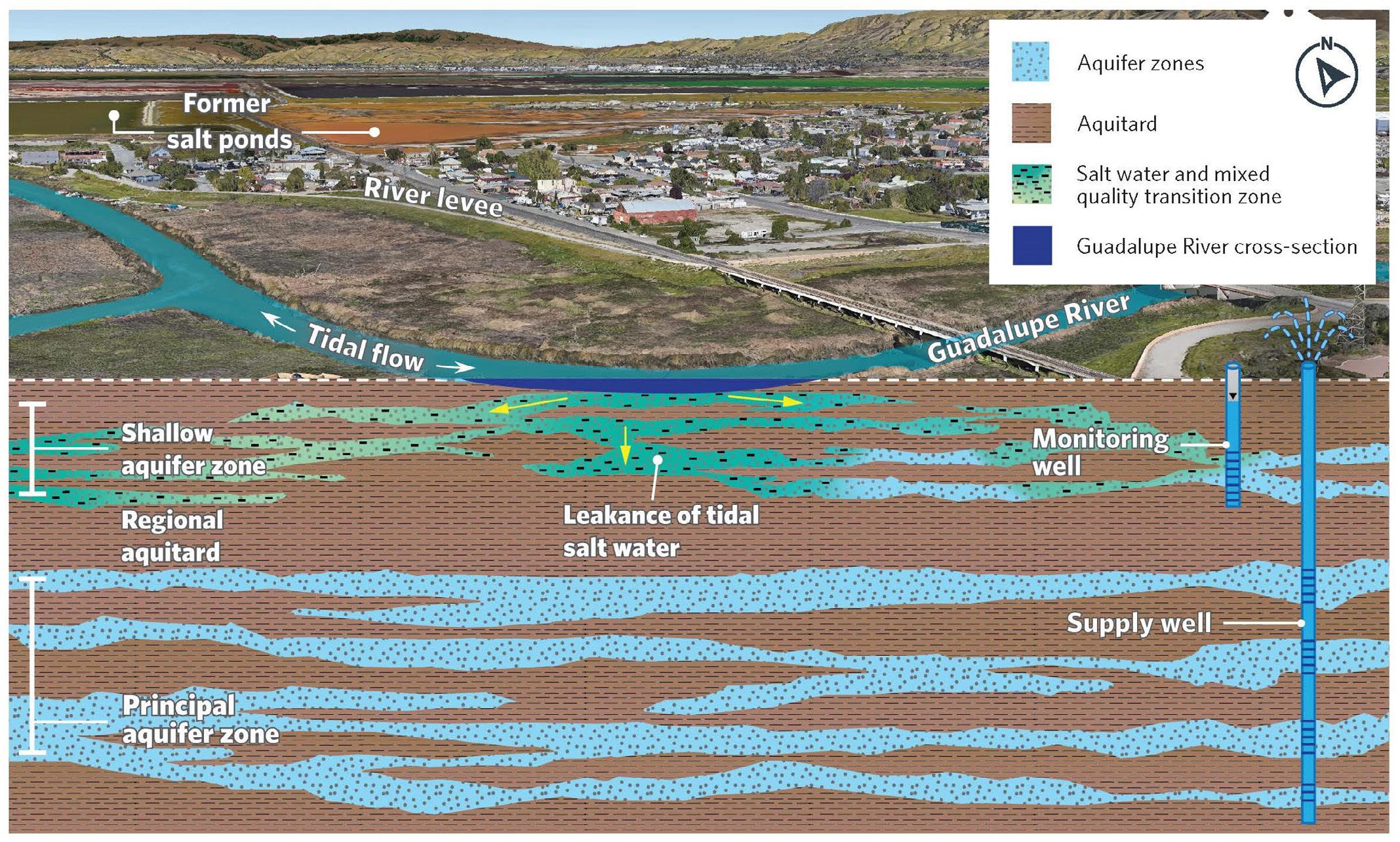

Hydrogeologic data from Valley Water’s seawater intrusion groundwater monitoring network confirms that Santa Clara Subbasin aquifer units near the Bay are relatively thin and typically separated from the Bay and tidal streams by thick clay aquitards that restrict the inflow of Bay water into the shallow aquifer. Additionally, due to the gently sloping land surface and the relatively shallow groundwater near the Bay, the shallow aquifer likely functions as a topography-limited system (Michael et al., 2013) where the water-table rise is less pronounced than SLR because the excess groundwater discharges into drainage networks, such as rivers, creeks, and unlined canals. As a result, future groundwater levels may not rise as a spatially uniform, linear (1:1) response to rising sea levels.

Because of the Bay mud and clay aquitards, the classic case of seawater intrusion with a saltwater wedge has a relatively minor role in the Santa Clara Subbasin. Rather, leakance of saltwater and brackish water beneath tidal stream channels is likely the most important mechanism that affects the overall spatial extent and inland migration of seawater intrusion in the Santa Clara Subbasin (Figure 1). Tidally influenced stream reaches extend considerable distances inland, generally aligning with the inland extent of maximum historical (circa 1960) seawater intrusion, supporting the conceptual model that tidal stream flow leakance is a key mechanism of seawater intrusion in the shallow aquifer.

Under current conditions, groundwater rise in the shallow aquifer typically follows seasonal and annual patterns in rainfall and tides. Shallow groundwater is a naturally occurring feature in some areas of the Santa Clara Subbasin and presents challenges for some basements and underground parking structures, particularly during above average wet winters. Shallow groundwater levels typically decrease during the dry summer and fall months of average rainfall years and during drought years.

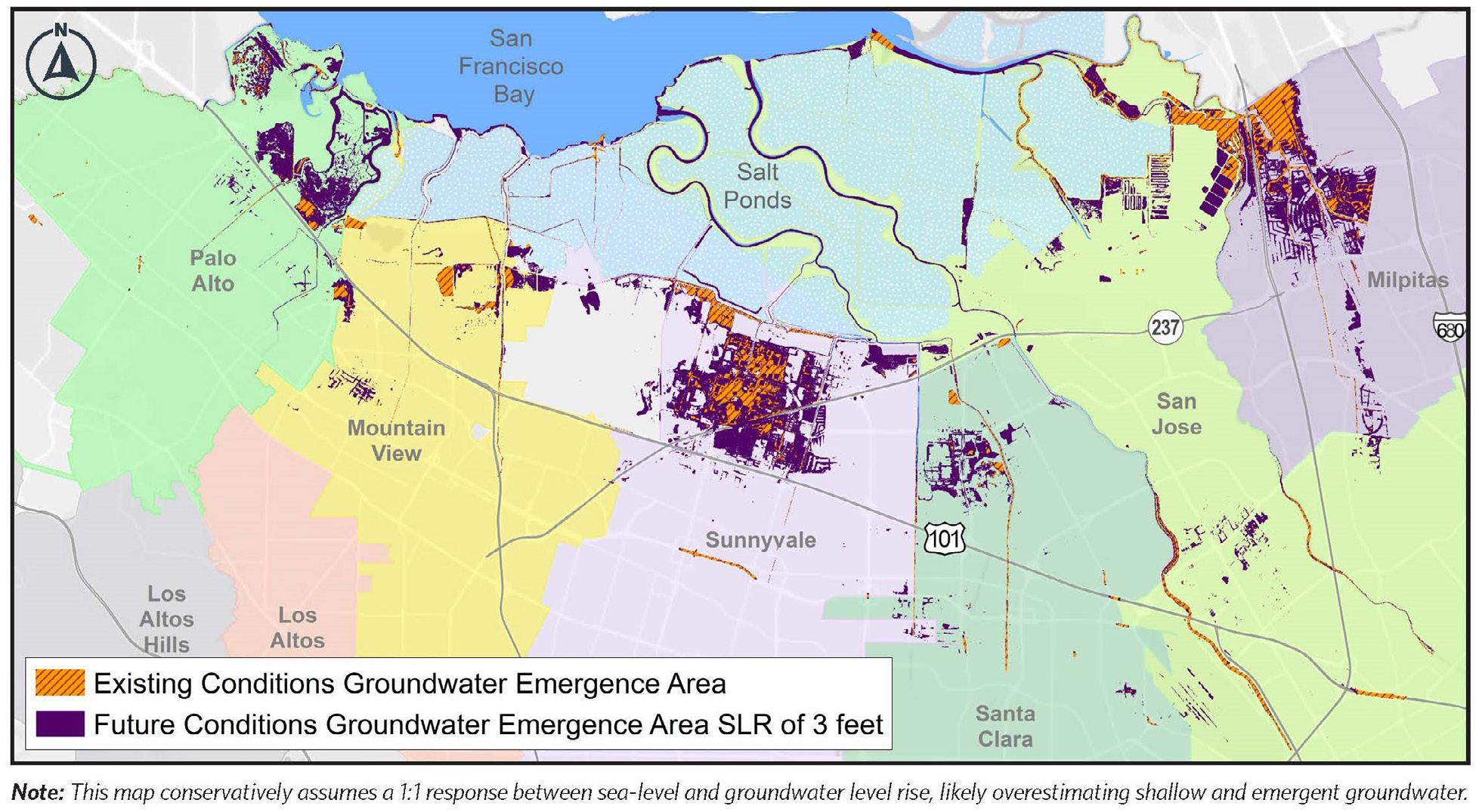

Groundwater emergence today is not a widespread concern in Santa Clara County, as it has been observed only in localized areas near the Bay, typically in undeveloped lands, open spaces, wildlife preserves, and parks, almost exclusively where land surface elevation is below mean sea level (Figure 2). While the Bay mud and clay layers generally protect the aquifer from seawater intrusion, these localized areas with tidally driven groundwater emergence likely have a subsurface connection to the Bay.

The estimated (interpolated) map of existing conditions shows about 1.7 square miles of groundwater emergence (Figure 3). However, a comparison of 330 independent groundwater levels from the exceptionally wet winter of 2022-2023 indicates that the map tends to overestimate shallow and emergent groundwater, with 70% of measurements deeper than depicted by the map. Although groundwater may be slightly shallower than shown for some areas, the actual highest groundwater is deeper than the map indicates at most locations. Several factors contribute to this tendency to overestimate conditions, as described next.

Maps of estimated groundwater rise and emergence, like all groundwater models, have inherent uncertainty and limitations because they simplify a complex system. Understanding these uncertainties is important for interpreting maps and appropriately using them to support management, planning, or policy decisions.

The usefulness of the existing and future maps of groundwater rise and emergence depends on both the map developer and map user. The map developer should clearly explain how the maps were created and describe their inherent uncertainties and limitations. Users should consider these uncertainties and limitations and evaluate whether these maps suit their intended application, recognizing that each project or community may have different needs or uses.

It is important for users to understand that the existing groundwater emergence map (Figure 3) represents a temporal composite of the highest recorded groundwater level at each well between 2000 and 2020 and therefore shows a theoretical

highest-case scenario for shallow groundwater conditions. However, given actual variability in recharge, discharge, and other aspects of the groundwater system, it is unlikely that all wells would have the highest recorded water levels simultaneously under actual conditions.

The maps were created using water levels from shallow monitoring wells less than 50 feet below land surface. While some wells are screened in aquifers with a direct hydraulic connection with tidally influenced streams or the Bay, many are screened in confined or semiconfined aquifers and have water levels that respond more to pressures changes from tides, stream stage, and rainfall- and soil moisture-loading. These aquifers have limited direct connection with Bay water and thus respond less to the actual flow of water from tides, rainfall, or SLR that could otherwise lead to rising groundwater levels or emergence in an unconfined aquifer. A pressure-driven potentiometric surface rise in a monitoring well screened in a confined or semiconfined aquifer does not necessarily indicate that groundwater will emerge from these aquifers because the thick clay layers restrict the upward flow of groundwater. For these reasons, the maps of existing highest groundwater conditions may overestimate shallow and emergent groundwater in some areas. These hydrogeologic concepts have important implications for interpreting how groundwater rise and emergence in the shallow aquifer of the Santa Clara Subbasin may respond to future changes in sea level, tides, and rainfall.

Field validation reinforces these findings. During the 2024 king tides (naturally occurring events that provide a preview of future sea levels because the tide rises one to two feet above the average), only about 33% of areas mapped (interpolated) as groundwater emergence had field confirmed or suspected

groundwater emergence and covered only 0.18 square miles — an order of magnitude smaller than the mapped 1.7 square miles (Figure 3). Field observations confirmed the remaining 67% of the areas mapped as groundwater emergence either had a direct connection to tidally influence surface water or had no observed groundwater emergence during the king tides. These results highlight the importance of field observations before using maps to inform decisions.

Interpolation methods also affect map results. Valley Water used spline, in part, because other interpolation methods (kriging, inverse distance weighting, and multi-quadratic radial basis) produced even greater overestimates of shallow and emergent groundwater, and in many cases, unrealistic spatial extents of groundwater emergence based on field observations. These results highlight that the choice of interpolation method likely has considerable bearing on the accuracy and reliability of groundwater rise and emergence maps. For example, a potential planning or policy decisions might have very different outcomes if based on maps created using spline versus multi-quadratic radial basis interpolation.

The map of existing highest groundwater conditions and emergence (Figure 3) is used to project future groundwater conditions under sea-level rise. Because existing conditions are already overestimated, the projected maps are likely to overestimate future shallow and emergent groundwater as well. In addition, the maps do not account for other factors that affect future groundwater levels, including future patterns in precipitation, evapotranspiration, streamflow, natural recharge, managed recharge, groundwater pumping, or changes in land use or operations of salt ponds, levees, or other infrastructure around the Bay.

Conclusions and Monitoring Window into the Future

Communities are beginning to use groundwater rise and emergence maps to help support management, planning, and policy decisions. As outlined in this article, identifying and discussing the inherent uncertainties and limitations of these maps can help communities evaluate the appropriate uses to support best-informed decisions.

Today’s tidally driven groundwater emergence areas not only provide an important dataset to validate groundwater rise and emergence maps but are a window into forecasting future groundwater conditions. As SLR continues, the areas of present-day tidally driven groundwater emergence may experience more frequent and persistent groundwater emergence that expands in area over time, likely before higher-elevation areas show noticeable changes. Valley Water plans to continue monitoring these locations to better understand how groundwater rise and emergence may expand or increase in other areas as Bay levels increase.

Acknowledgements

Valley Water staff Chanie Abuye, Scott Elkins, Victoria Garcia, Cheyne Hirota, Dana Kilsby, Geoff Tick, and Meijing Zhang were contributing authors on the 2025 study.

References

Bosserelle, A.L., Morgan, L.K., and Hughes, M.W., 2022, Groundwater rise and associated flooding in coastal settlements due to sea-level rise: A review of processes and methods, Earth’s Future, 10, e2021EF002580, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002580.

Green, T., Taniguchi, M., Kooi, H., Gurdak, J.J., Hiscock, K., Allen, D., Treidel, H., and Aurelia, A., 2011, Beneath the surface of global change: Impacts of climate change on groundwater, Journal of Hydrology 405:532-560, doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol2011.05.002.

Gurdak, J.J., 2025a, Groundwater response to tides, seawater intrusion and sea-level rise in Santa Clara County, California, Santa Clara Valley Water District (Valley Water), Fact Sheet, San Jose, California, 2 pages, https://www.valleywater.org/your-water/groundwater/groundwaterstudies

Gurdak, J.J., 2025b, Uncertainties and limitations of groundwater emergence maps for the Santa Clara Subbasin, South San Francisco Bay, California, 8th Annual Western Groundwater Congress, Groundwater Resources Association of California, San Diego, California, October 9, 2025.

Gurdak, J.J., Abuye, C., Elkins, S., Garcia, V., Hirota, C., Kilsby, D., Tick, G., Zhang, M., and De La Piedra, V., 2025, Groundwater response to tides, seawater intrusion and sea-level rise in Santa Clara County, California, Santa Clara Valley Water District (Valley Water), Report, San Jose, California, 237 pages, https://www.valleywater.org/your-water/ groundwater/groundwater-studies

Habel, S., Fletcher, C., Barbee, M., and Fornace, K.L., 2024, Hidden threat: The influence of sea-level rise on coastal groundwater and the convergence of impacts on municipal infrastructure, Annual Review of Marine Sciences, 16, 81-103, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevmarine-020923-120737

Hill, K., Hirschfeld, D., Lindquist, C., Cook, F., & Warner, S., 2023, Rising coastal groundwater as a result of sea-level rise will influence contaminated coastal sites and underground infrastructure. Earth’s Future, 11, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003825

Hoover, D.J., Odigie, K.O., Swarzenski, P.W., and Barnard, P., 2017, Sealevel rise and coastal groundwater inundation and shoaling at select sites in California, USA, Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 11, 234-249, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2015.12.055.

KQED, 2024, See which Bay Area schools are at risk from rising seas, by Katie Worth (ClimateCentral), Sirui Zhu (Climate Central), and Elzra David Romero (KQED), August 5, 2024,https://www.kqed.org/ science/1993798/see-which-bay-area-schools-are-at-risk-from-risingseas

May, C.L., Mohan, A.T., Hoang, O., Mak, M., Badet, Y., 2020, The response of the shallow groundwater layer and contaminants to sea level rise, Report by Silvestrum Climate Associates for the City of Alameda, California, 153 pages.

May, C.L., Mohan, A., Plane, E., Ramirez-Lopez, D., Mak, M., Luchinsky, L., Hale, T., Hill, K., 2022, Shallow Groundwater Response to Sea-Level Rise: Alameda, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo Counties. Prepared by Pathways Climate Institute and San Francisco Estuary Institute, https://www.sfei.org/documents/shallow-groundwater-response-sealevel-rise-alameda-marin-san-francisco-and-san-mateo

Michael, H.A., Russoniello, C.J., Byron, L.A., 2013, Global assessment of vulnerability to sea-level rise in topography-limited and recharge-limited coastal groundwater systems, Water Resources Research, 49, 2228-2240, doi:10.1002/wrcr.20213.

Plane, E., Hill, K., and May, C., 2019, A rapid assessment method to identify potential groundwater flooding hotspots as sea levels rise in coastal cities, Water, 11, 2228, doi: 10.3390/w11112228, https://www. mdpi.com/2073-4441/11/11/2228.

San Francisco Examiner, 2024, Rising groundwater, higher seas may threaten downtown San Francisco, by Patrick Hoge, April 21, 2024, https://www.sfexaminer.com/news/climate/whyrising-groundwatermay-threaten-san-francisco-buildings/article_c0f9b6a0-fdeb-11ee80c8-bfd3b8ef1431.html

Treidel, H., Martin-Bordes, J.J., and Gurdak, J.J. (Eds.), 2012, Climate change effects on groundwater resources: A global synthesis of findings and recommendations, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN: 9780-415-68936-6, 414 pages.

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G.H.P., Biefkens, M.F.P., 2024, Global impact of sea level rise on coastal fresh groundwater resources, Earth’s Future, 12, e2023EF003581. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003581

We don’t just understand municipal, local, and industrial water cycles — our experts partner with you to bring innovative solutions that meet today’s needs and anticipate tomorrow’s challenges

PROVIDING INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS FOR MANAGING OUR CRITICAL WATER RESOURCES

Related Services

Water Resources Modeling

Managed Aquifer Recharge

Interconnected Surface Water Analysis

Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems

Subsidence Analysis

Our Groundwater Sustainability Services

• Geophysical surveys and interpretation

• Hydrogeologic conceptual models

• Groundwater flow models

• Managed aquifer recharge

• Water availability assessments

• Risk and resilience assessments

• Vulnerability assessments

• Water resources management

• Data compilation and quality screening

• Data collection and management

• Expert witness/litigation support

Stormwater Management

PFAS Sustainable Groundwater Management

Groundwater

Celebrating 46 Years!

▪ Modeling Software Development

▪ Hydrogeological Modeling

▪ Geochemical Investigation & Modeling

▪ Contaminant Fate & Transport

▪ Water Supply Evaluations

▪ Aquifer Storage & Recovery

▪ Managed Aquifer Recharge

▪ Monitoring Well and Pump Performance Optimization

▪ Remediation Engineering for Soil, Groundwater, and Surface Water

▪ Sampling and Field Services

▪ Expert Testimony & Litigation Support

SGMA

Groundwater Policy and GSA Support

Multibenefit project planning, permitting, and design

Basin characterization and data visualization

Groundwater and surface water modeling

Groundwater monitoring and aquifer test analysis

Surface water interaction studies - Managed aquifer recharge siting, engineering and design

Source water protection

Groundwater-dependent ecosystem evaluation

Groundwater trading and accounting

by Katherine Dlubac1, Steven Springhorn1, Mesut Cayar2, Nicole Jacobsen2, Jack Baer2, Kyle Nordquist2, Vivek Bedekar3, Gengxin (Michael) Ou3, Paul Thorn4, Javier Peralta4, Timothy Parker4, Julie Chambon4, Maria Pinzon4

The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has a long history of studying and documenting groundwater conditions across the state through California’s Groundwater: Bulletin 118 and ongoing Basin Characterization (BC) Program efforts. Under the BC Program, DWR collects and analyzes data through statewide, regional, and local investigations to support SGMA implementation and address key data gaps.

These investigations involve digitizing existing information and collecting new data as needed. New data may include airborne and surface-based geophysics, advanced geophysical well logging, installation of new monitoring wells, or reactivation of existing wells. All collected and digitized data are integrated and analyzed using innovative tools to produce maps and models that describe aquifer materials, subsurface structures, key aquifer units, and potential recharge pathways. DWR will continue to update and maintain these products.

At the statewide scale, DWR completed the Statewide Airborne Electromagnetic (AEM) Survey Project in 2024. This project provides a geophysical and hydrogeologic interpretation dataset for medium- to high-priority basins and improves understanding of large-scale aquifer structures. More information is available in Chapter 3 of California’s Groundwater: Bulletin 118 – Update 2025

At regional and local scales, BC Program investigations focus on groundwater recharge pathways, surface water–groundwater interactions, land subsidence, seawater intrusion, and delineation of the base of fresh water, along with human-related concerns such as vulnerable domestic wells and disadvantaged communities. By incorporating new data, DWR is developing maps, models, guidance, and decision-support tools to help Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) and local communities better evaluate and manage their groundwater resources.

Regional Investigations

DWR is conducting regional investigations to better understand recharge potential and subsidence risk in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys. These efforts are coordinated in collaboration with local, state, and federal partners. The investigations are focused on the following three regions:

• Sacramento Valley

• Four County Area of the San Joaquin Valley (Madera, Fresno, Kings, and Tulare counties)

• San Joaquin Valley

The section below provides the local and regional investigation areas with links to the respective datasets on the California Natural Resources Agency Open Data Portal

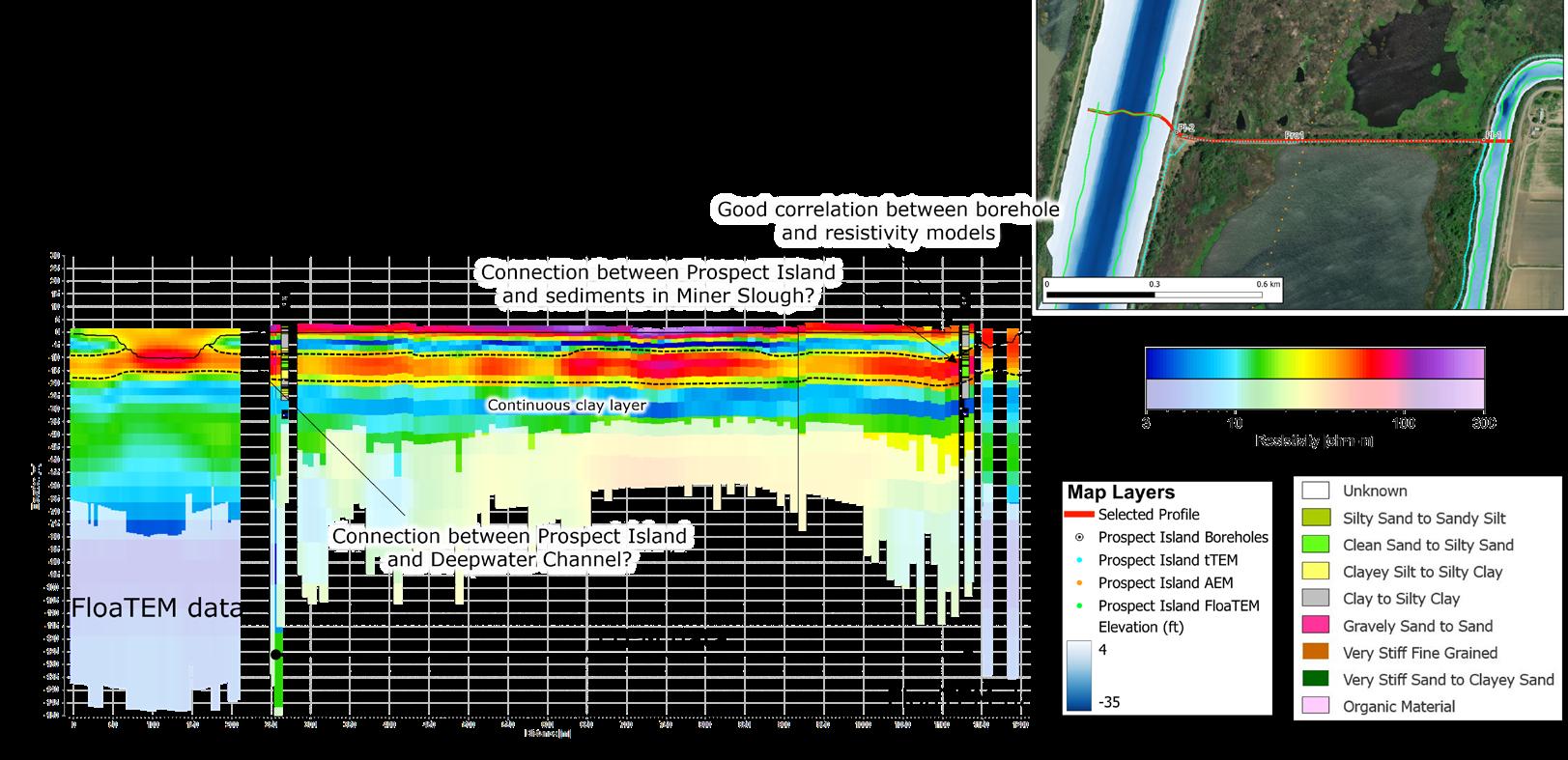

Local investigations aim to better understand recharge potential, subsidence, and surface water–groundwater interactions at a higher-resolution than the regional investigations. These investigations combine digitized data with new infill AEM, towed Transient EM (t-TEM) (Photo 1), and floating TEM (FloaTEM) (Photo 2) surveys to create detailed maps and models of subsurface conditions (Figure 1). Four local investigations are currently underway in the following locations:

• Madera & North Kings

• Pajaro

• Western San Joaquin Valley

• Prospect Island within the Sacramento Delta

The section below highlights the activities, maps, and models developed within the Madera and North Kings local investigation.

Madera and North Kings Local Investigation

This investigation supports floodplain habitat restoration, improved understanding of surface water–groundwater interactions, enhanced groundwater recharge, and assistance for vulnerable domestic wells. The study area lies in portions of the Kings and Madera subbasins, located between the Upper San Joaquin and Fresno rivers.

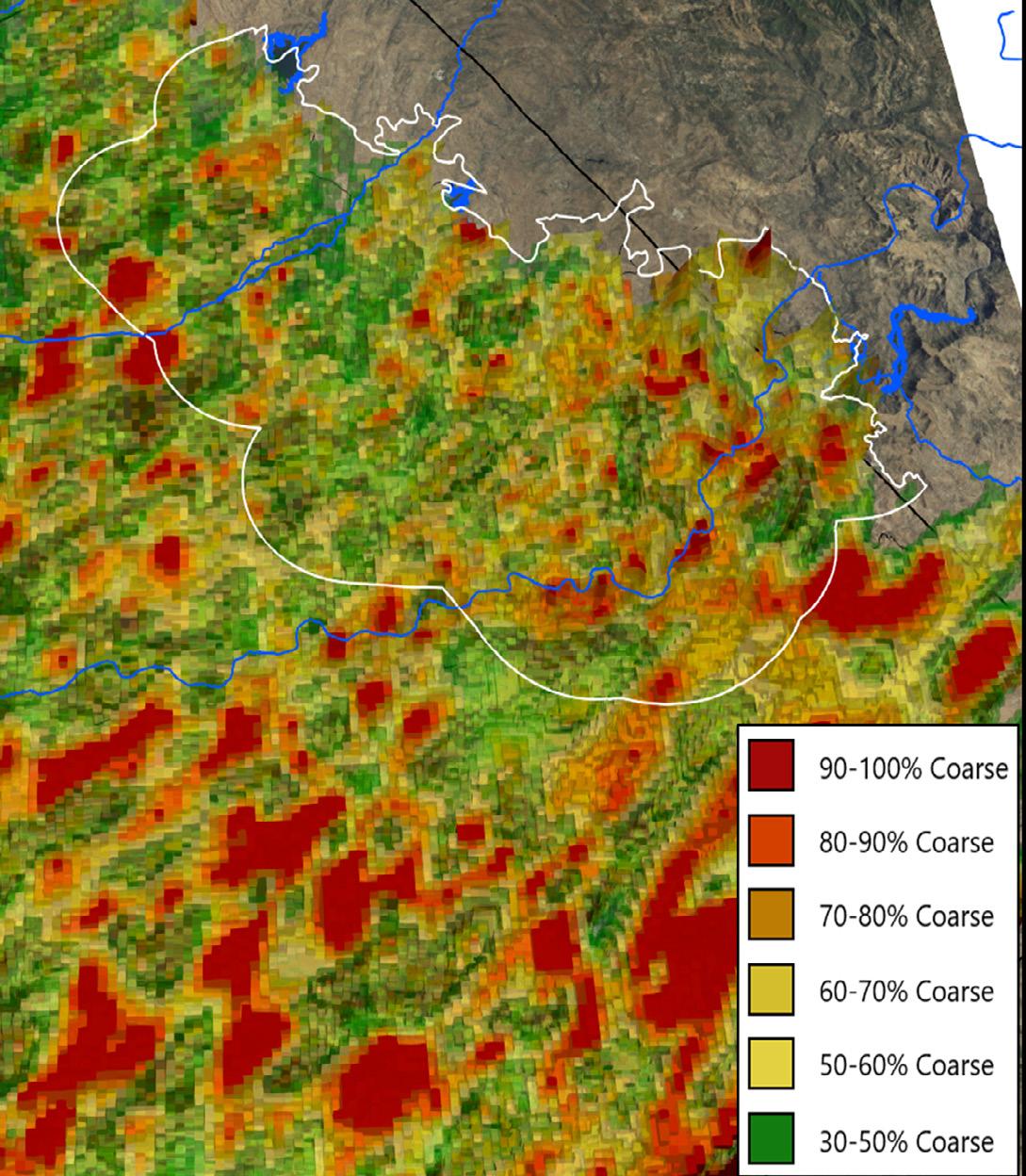

The goal is to help GSAs and local partners identify locations suitable for deep recharge (to replenish major aquifers), shallow recharge (to support vulnerable domestic wells), and floodplain restoration projects. To accomplish this, DWR reviewed statewide AEM data, collected infill AEM surveys, created a high-resolution texture model, developed Aquifer Recharge Potential (ARP) maps, and performed focused ground-based surveys.

AEM Infill Data Collection

Statewide AEM data aligned with known alluvial fan locations and revealed additional coarse-grained sediments outside the fans. Infill AEM surveys were conducted to provide finer detail in these potential recharge zones. Results showed coarse-grained pathways extending from the valley’s eastern edge into deeper aquifers, as well as crescent-shaped buried incised-valley fill (IVF) channels. For details on the infill AEM data interpretation for IVF, see Chapter 3 of California’s Groundwater: Bulletin 118 – Update 2025.

Texture Model

DWR used Data2Texture to integrate AEM data with digitized lithology logs, producing a 3D texture model with a horizontal resolution of 32 acres and 15-foot vertical layers to a depth of 400 feet (Figure 2). This model helps identify IVF channels and other promising recharge locations.

Aquifer Recharge Potential Maps

The texture model was combined with groundwater levels and soil data to create ARP maps, which highlight areas most suitable for different recharge methods. These maps are intended as screening tools, and site-specific studies are recommended before project development to monitor recharge suitability and assess water quality impacts.

Surface Geophysics Data Collection

ARP results were shared with GSAs and interested landowners to help prioritize sites for further investigation. DWR then collected t-TEM data at eleven sites, including agricultural fields, fallowed land, and developing detention basins. The t-TEM method involves towing a series of sleds containing geophysical equipment behind an all-terrain vehicle. These high-resolution t-TEM surveys help identify shallow sand and

gravel layers as well as clay barriers that influence recharge feasibility. The datasets are expected to be available to GSAs and landowners in early 2026.

This work demonstrates how integrating airborne, groundbased, and well log data with advanced analysis tools can significantly improve understanding of recharge opportunities and supports sustainable groundwater management. As part of the BC program, DWR continue to collect data, develop and refine analysis tools, and provide data and interpreted results on the California Natural Resources Agency Open Data Portal.

At LWA, we understand that groundwater is vital for California’s water future. We’re here to help communities manage this precious resource wisely and in line with state regulations.

Davis, CA | 530.753.6400 with regional offices in Berkeley, San Diego, San Luis Obispo, Santa Monica, Seattle, Ventura, and Yreka

Creating sustainable water supplies for the future requires reimagining the water cycle

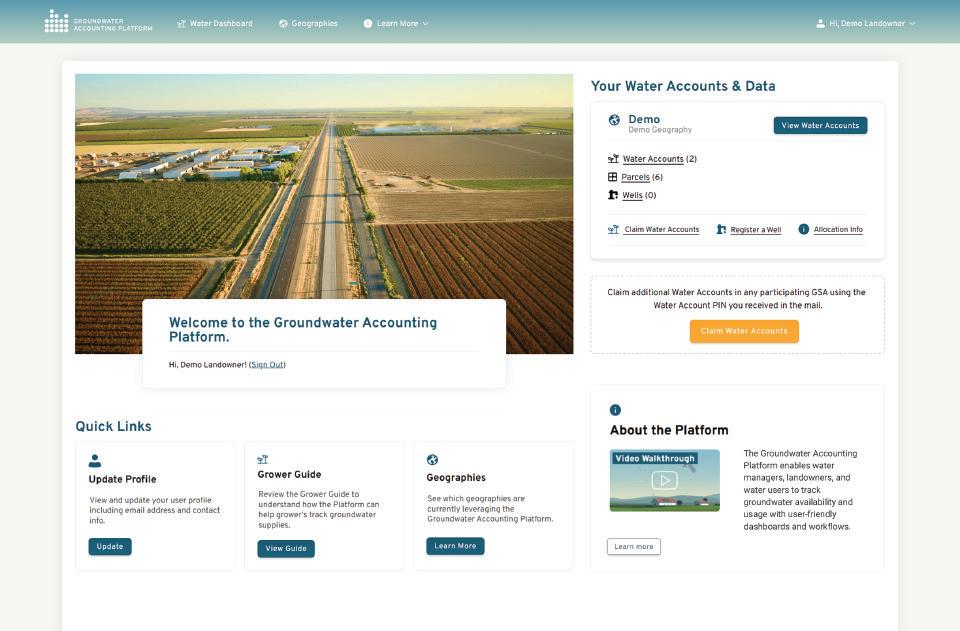

To help California water agencies implement their SGMA programs, a unique public-privatenonprofit partnership joined forces to develop the Groundwater Accounting Platform.

This flexible software enables water managers, landowners, and water users to track groundwater availability and usage with user-friendly dashboards and workflows, empowering local communities to meet their water usage goals.

It has been successfully deployed in 6 subbasins across the state, with new agencies and users joining every year.

Groundwater is California’s most vital resource. At WSP, we bring science, engineering and innovation together to deliver sustainable solutions that secure groundwater for generations to come.

by DEI Committee Members: Annalisa Kihara, State Water Resources Control Board and Angie Rodriguez-Arriaga, West Yost Associates

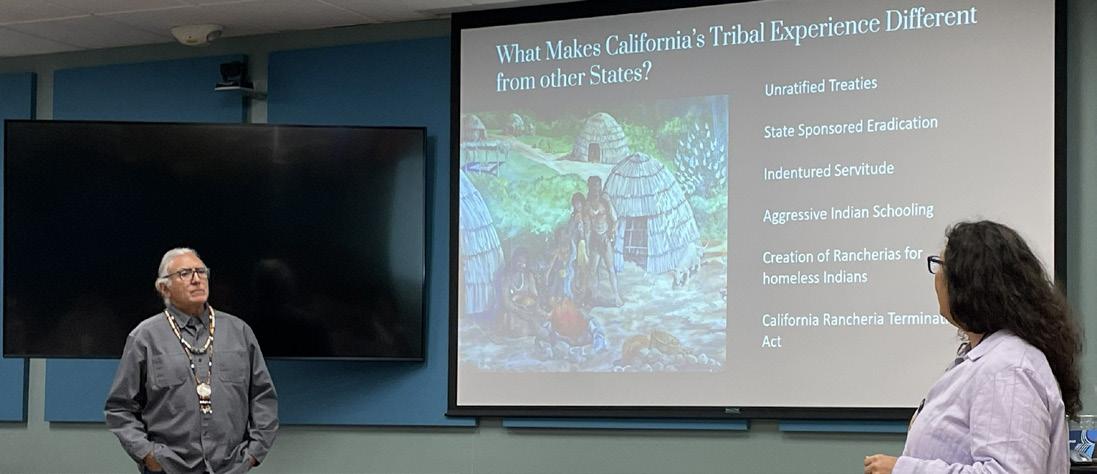

In early November 2025, GRA leadership, including Board Members and DEI Committee Members, came together for an impactful training on California Tribal History, Relationship Building, and Engagement, in Davis, CA. The workshop created a space for reflection, dialogue, and a deeper understanding of how water professionals can engage with California Tribes in more meaningful and informed ways and was facilitated by Watershed Solutions Network (WSN).

The idea for this training emerged from DEI Committee discussions, when members began reflecting on the persistent gap between technical planning and cultural understanding in California water management. The DEI Committee, which includes representatives from GRA, the State Water Resources Control Board, local agencies, and consulting firms, recognized that many groundwater practitioners lacked historical and cultural context for working with Tribes. In particular, they saw how this gap limits progress under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), where long-term sustainability depends on collaboration across all water users.

The GRA DEI Committee itself was formed in the summer of 2020 following nationwide conversations about equity and representation. What began as a small task force evolved into a standing committee supported by GRA’s first DEI Executive Officer. As the committee grew, members articulated a shared desire to create or host a training centered on groundwater projects and day-to-day work, rather than a DEI training program detached from water practice. When the committee searched for existing options, they found very few programs that addressed these needs, which ultimately led to a partnership with the WSN to develop a session tailored to GRA leadership.

The training was facilitated by Debbie Franco, CEO of WSN, and Mark Franco (Traditional Lifeways), former Headman of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe. The facilitators provided an overview of California’s distinctive Tribal history, one marked by the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, the eighteen unratified treaties of 1851-52, and later federal policies that gave rise to the Rancheria system and subsequent termination efforts. Participants explored how these legacies continue to affect Tribal sovereignty, land and water access, and recognition of Tribal rights today.

Debbie and Mark noted that, although interest in Tribal engagement is growing, meaningful opportunities are still limited for statewide for Tribal-led education within the water sector. They emphasized that this training represents only an initial step toward broader institutional learning and encouraged attendees to continue seeking out Tribal-led spaces for education and dialogue.

Participants reflected that agency and consultant engagement processes are often guided by project-specific timelines or regulatory requirements, which can unintentionally limit when and how dialogue with Tribes occurs. Meaningful collaboration, facilitators emphasized, depends on relationships built on continuity, reciprocity, and trust, rather than single phases of a project.

Participants were invited to reflect on how their current engagement practices align with these principles. Several recurring themes surfaced in small-group discussions. Participants observed that Tribal engagement is often initiated in response to regulatory requirements such as SGMA coordination or CEQA consultation, rather than emerging from an internal commitment to relationship building. Others reflected that engagement responsibilities are frequently assigned to a single project manager or liaison, which can unintentionally isolate Tribal coordination from broader project decision-making. Facilitators then encouraged participants to consider how these structural patterns influence outcomes. Participants discussed how, when

engagement is framed as a task rather than a relationship, Tribes are often left responding to predefined scopes and timelines rather than helping shape them. This approach suggests a need to revisit how engagement is built into early project scoping, budgeting, and team assignments rather than being layered in after decisions are already underway. By contrast, participants noted that involving Tribes earlier in conceptual phases allows projects to reflect a wider range of values, including cultural uses of water, intergenerational impacts, and place-based knowledge.

The session also incorporated Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and its relevance to modern resource management. Field-based collaboration and “sense-ofplace” learning were discussed as ways to bridge scientific and cultural perspectives. Case studies highlighted leaders such as Trina Cunningham (Mountain Maidu) and Austin Stevenot (River Partners), who demonstrate how Indigenous knowledge can guide restoration and watershed work.

Moving Forward

Participants concluded the workshop by sharing ways they hope to build on this momentum, including staying connected with Tribes in their project areas, being more intentional about how and when engagement is woven into projects, and continuing their own learning through resources such as the California Truth and Healing Council, the Native American Rights Fund’s Tribal Water Institute, and An American Genocide by Benjamin Madley.

“We often get caught up in planning and implementing projects without more thoughtful consideration of ‘How was the land valued and managed before us?’ This training provided a chance to take a step back and look at things differently. This in itself was valuable, but what really stood out to me is the need to encourage more engagement with our Tribal partners to steward our water resources more effectively.”

— Erik Cadaret, 2026 GRA President

To join the committee and/or stay connected via our monthly newsletter, please reach out to Annalisa.Kihara@waterboards. ca.gov or arodriguez@westyost.com

YJD specializes in, but is not limited to providing drilling services to the Environmental, Geotechnical, Mining, Water Supply and Energy Market Sectors.

Some of our available drilling methodologies include:

Flooded Reverse Circulation, Dual Tube Reverse Circulation, Dual Rotary, Mud Rotary, Air Rotary, Air Rotary Casing Hammer (ARCH), Air Rotary Casing Advancement (STRATEX), Sonic, Hollow Stem Auger, Direct Push, Conventional & Wireline Coring, Air Knife / Utility Clearance, Well Abandonment, and Well Services (Development/Pump Installations)

by Savannah Tjaden, GRA Director

A Conference Built on Connection

As Chair of the 2025 Western Groundwater Congress (WGC), I feel privileged to reflect on a week that reaffirmed why this conference—and this community—matters so deeply. From the very beginning, WGC has been about connection: bringing together the broader groundwater community to learn, grow, and face challenges together. While technical sessions and panels are a critical part of that experience, the real value of WGC is built through the relationships we carry back into our daily work—the trust we develop, the conversations that continue long after the conference ends, and the shared commitment to something bigger than any one project or organization.

This year, that sense of connection felt especially strong. Walking through the conference, I was struck not only by the familiar faces who return year after year, but by the number of new ones. The 2025 WGC set a new attendance record, with over 380 participants—representing roughly a 15% growth over previous years. More importantly than the number itself, that growth reflects something meaningful: people are finding value in coming together, continuing to build relationships, and sharing ideas in a space designed to foster trust and collaboration. Participant distribution included ~30% for both members and speakers, 20% government members, ~10% for both non-members and sponsors, plus several students and 10% of the participants attended the pre-WGC workshops.

Our 2025 theme, “Join Team GRA,” was meant as an invitation rather than a slogan. Groundwater management is, at its core, a team effort. It requires technical skill, open-mindedness, and creativity, and it demands that we work across roles, sectors, and perspectives that do not always naturally align.

At WGC, scientists, engineers, modelers, policymakers, regulators, consultants, nonprofit leaders, students, and community advocates come together as one team—united by a shared responsibility to steward groundwater resources in an increasingly complex and visible water landscape. For three days, the Congress served as a home base for that team, creating space to share ideas, challenge assumptions, and strengthen the relationships that shape the future of groundwater management in the West.

The opening keynote session captured another defining feature of the 2025 WGC: a focus on progress that is both pragmatic and deeply human. Rather than centering solely on outcomes, the keynote highlighted how collaboration, persistence, and partnership made those outcomes possible. The stories underscored a truth that surfaced again and again throughout the week—big groundwater problems cannot be solved in isolation.

Across sessions and conversations, a consistent theme emerged. Strong technical foundations are essential to groundwater management, but they are only part of the equation. As projects move from planning to implementation, success increasingly depends on our ability to work with a broad range of people from different backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives. Serving communities effectively means pairing rigorous science and data with an understanding of local context, human impacts, and the lived realities of those affected by groundwater decisions.

Engaging in big, hard conversations—with kindness, empathy, and respect—is not easy, but it is necessary. The 2025 WGC demonstrated that when people are willing to do that work together, meaningful progress becomes possible.

The strength of the 2025 Western Groundwater Congress was not just the wide range of topics and sessions, but how intentionally those conversations were brought together. The program reflected the increasingly interconnected nature of groundwater work—where technical innovation, data and modeling, recharge, water quality, governance, demand management, and community engagement are no longer siloed efforts, but interdependent parts of the same challenge. Creating space for those conversations to intersect is what allows ideas to move from theory to practice.

One of the most notable evolutions of the Congress this year was the introduction of pre-conference workshops. New to WGC in 2025, these workshops were designed to create hands-on, interactive spaces for participants to engage more deeply with shared challenges and emerging approaches. Based on the positive feedback we received, we see this as a format worth continuing and refining—one that creates dedicated time for collaborative learning and deeper peer exchange as part of the WGC experience.

Just as important were the moments that happened outside of formal sessions. Conversations over coffee, shared meals, poster sessions, and informal networking created opportunities for people at different stages of their careers and from different disciplines to connect. These exchanges— between students, early-career professionals, and seasoned practitioners—are where perspectives are broadened and assumptions are challenged. Seeing new faces alongside longtime attendees reinforced that the groundwater community is not static; it is growing, evolving, and actively welcoming those who want to contribute.

These informal interactions are often where the most lasting impacts begin. Mentorship relationships take shape, partnerships are formed, and ideas are pressure-tested in ways that don’t happen at a podium. They are also where the future of groundwater management is quietly built—through trust, shared understanding, and a willingness to learn from one another.

None of this would be possible without the care, insight, and generosity of the volunteers, presenters, planning committee members, and sponsors who make the Western Groundwater Congress happen. WGC is truly a communitydriven effort, shaped by people who step up to share their expertise, give their time, and invest in creating a space for meaningful exchange. We are also deeply grateful to our event sponsors, whose support helps make the Congress accessible, welcoming, and impactful year after year. Together, this collective commitment is what allows WGC to continue evolving and growing.

As we look ahead, the momentum from the 2025 Congress is something to carry forward. The conversations started in San Diego do not end there—they continue in board rooms, community meetings, field sites, agencies, and partnerships across the West.

The challenges facing groundwater management are complex and often daunting, but the 2025 WGC reinforced a hopeful truth: when people show up, engage thoughtfully, and commit to working together, meaningful progress is possible.

Thank you to everyone who joined us, contributed their expertise, and helped make this year’s Congress such a success. Whether you attended for the first time or have been part of WGC for many years, you are part of this community—and part of the team.

by Chris Bonds - DWR, Sacramento Branch Member at Large

GeoH2OMysteryPix is a fun addition to HydroVisions that started in Fall 2022, so going on 3 years now. The idea is simple; I provide one or more photograph(s) and two questions, along with a hint, and HydroVisions’ readers email in their guesses.

In a future issue of HydroVisions, I will share the answer(s) along with some brief background/historical information about the photos and acknowledge the first person(s) to email me the correct answer(s).

GRA looks forward to your continued participation in GeoH2OMysteryPix

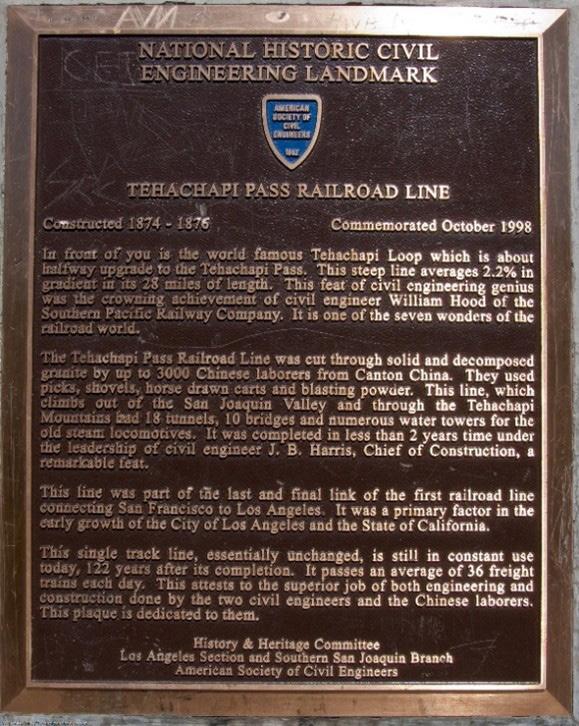

FALL 2025 ANSWERS

What is this? Where is it Located?

Hint: An amazing and world-famous railroad feature in the western U.S.

Congratulations to Trevor Pontifex, PG, Hydrogeologist, Montgomery & Associates for providing the following correct response to the Fall 2025 GeoH2OMysteryPix Questions:

TP: “I recognize Tehachapi Loop in the latest GeoH2OMysteryPix. My dad took me there on a road trip when I was a teenager. More recently, I was by myself taking a scenic route home from Yosemite. I planned to stop at Tehachapi Loop, but I didn’t know the train schedule. As luck would have it, I caught up to a train as I was approaching the Loop. It was a race to the viewpoint! I got there in

time to watch the train enter the Loop. The attached photo I took shows locomotives in the foreground pulling the train and some of the last cars on the train in the background.”

Background/History: The above personal photograph taken on September 1, 2016, shows a Union Pacific Railroad freight train traversing the Tehachapi Loop from the east.

The Tehachapi Loop (Loop) is a famous spiral section of railroad through the Tehachapi Mountains in Kern County (Southern California). Designed by Southern Pacific Railroad’s (SPRR) Chief Engineer William Hood and built by Chinese laborers using hand tools, black powder, and mules between 1874-1876, the Loop is considered an engineering marvel for its ability to allow trains to traverse the steep Tehachapi Mountains.

The intent of the Loop was to gain elevation at a manageable gradient (2.2%) and has worked so well for nearly 150 years that it has remained virtually unchanged and continues to be used by dozens of trains daily. For those of you that know and appreciate 19th century railroad engineering, a 2.2% gradient is STEEP!

The Loop extends for 3,799 feet (0.72 miles) with a diameter of 1,200 feet, a height difference of 77 feet between its highest and lowest points and includes the 428-foot-long tunnel #9. It is still a vital part of the area's transportation infrastructure and is now a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. Today, the Loop remains an important artery of Union Pacific Railroad after being acquired from SPRR in 1996.

Railfans from all over the world flock to this area hoping to get some $$ shots of trains traversing the Loop, Trevor P. and me, included...:)

References:

Wikipedia. 2025. Tehachapi Loop. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Tehachapi_Loop#

Adam Burns. 2024. Tehachapi Loop Grade: Map, Passenger Trains, History. American Rails blog.

https://www.americanrails.com/tehachapi.

html#gallery [pageGallery]/0/

What is this? Where is it Located?

Hint: The first of its kind US testing took place in this region of the Pacific Ocean during the mid-20th Century.

Think you know What this is and Where it is Located? Email your guesses to Chris Bonds at goldbondwater@gmail.com

by John Karachewski, PhD

Mount Shasta is a dormant stratovolcano in the southern Cascade Range. Geologic studies and natural hazard assessments indicate that Mount Shasta has erupted 10 or 11 times during the last 3,400 years, including at least 3 times in the last 750 years. At an elevation of 14,163 feet, Mount Shasta is the second-highest peak in the Cascade Range and the fifth highest in California.

Groundwater Modeling

The most voluminous of the Cascade volcanoes (estimated volume: 84 cubic miles), Mount Shasta is a massive compound stratovolcano composed of at least four main edifices constructed over the last 590,000 years. Two of the main eruptive centers at Mount Shasta, Shastina and Hotlum cones, were constructed during the Holocene Epoch.

Mount Shasta has a unique hydrology due to its volcanic geology and surface water - groundwater interactions. Although Mount Shasta often has a heavy snowpack, little surface water runs off the mountain. Snowmelt, rainfall, and glacial meltwater infiltrate and recharge fractured volcanic rocks and lava tubes as well broad aprons of pyroclastic-flow, debris flow, and alluvial deposits on the lower slopes of the mountain. Many springs discharge from the lower slopes of Mount Shasta.

Streams that originate on Mount Shasta drain into the Shasta River to the northwest, the Sacramento River to the west and southwest, and the McCloud River to the east, southeast, and south. Mount Shasta also hosts five glaciers: Bolam, Hotlum, Konwakiton, Whitney, and Wintun glaciers. Whitney Glacier is the largest glacier in California.

Photographed by John A. Karachewski, PhD, on February 8, 2023, near the Bunny Flat Trailhead along the Everitt Memorial Highway. The approximate GPS coordinates of the photograph are 41.354167° and -122.232986°. Information from the USGS California Volcano Observatory is available at https://www.usgs.gov/californiavolcano-observatory. Recreational reports for the Shasta-Trinity National Forest are summarized at https://www.fs.usda.gov/stnf.

Managed Aquifer Recharge

Hydrogeologic Investigations

Subsidence Evaluation and Mitigation

Seawater Intrusion Analysis

Municipal Well Design

Regulatory Compliance

Water Accounting Frameworks

SCAN TO LEARN MORE about GEI’s groundwater services

Jack Baer, PG is a Hydrogeologist at Woodard & Curran with more than seven years of experience in groundwater, surface water, and geologic modeling. His work combines programming and interdisciplinary methods to address groundwater and flood risk challenges. He holds degrees from Tufts University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Vivek Bedekar is a water resources consultant at S.S. Papadopulos & Associates with extensive experience in groundwater modeling, solute transport, and software development. He is the lead author of MT3D-USGS and contributes to peer-reviewed research and modeling training workshops.

Chris Bonds is a Senior Engineering Geologist (Specialist) with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) in Sacramento. Since 2001, he has been involved in a variety of statewide projects including groundwater exploration, management, monitoring, modeling, policy, research, and water transfers. Chris has over 31 years of professional work experience in the private and public sectors in California, Hawaii, and Alaska and is a Professional Geologist and Certified Hydrogeologist. He received two Geology degrees from California State Universities. Chris has been a member of GRAC since 2010, a Sacramento Branch Officer since 2017, and has presented at numerous GRAC events since 2004.

Erik Cadaret is an Associate Geologist with West Yost Associates and joined the GRA Board of Directors in 2021. Erik’s role with West Yost is to support various groundwater technical projects for clients within the state of California, management of a GSA in northern California, and support business development efforts to engage new clients. What Erik loves the most about his job is the interpersonal interaction with clients to help find creative solutions to meet their needs. Erik loves being a part of GRA because it provides an outlet to collaborate with some of the greatest minds in groundwater. Erik also loves to geek out on techy, innovative ideas that may significantly benefit the water industry in achieving sustainable groundwater for all.

Dr. Mesut Cayar, PE is a Senior Water Resources Engineer and Principal at Woodard & Curran with 20 years of experience in groundwater modeling, numerical analysis, and water resources planning. He leads integrated hydrologic and hydrogeologic investigations and focuses on developing innovative, datadriven solutions for sustainable groundwater management.

Dr. Julie Chambon, PE is a Senior Technical Manager at Ramboll with over 15 years of experience in hydrogeology, groundwater management, and modeling evaluation. She leads projects related to sustainable yield, climate change impacts, and management strategies for resilient groundwater supplies across California and the U.S.

Dr. Katherine Dlubac, PG is a Senior Engineering Geologist in the Sustainable Groundwater Management Office at the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), where she manages the Statewide Airborne Electromagnetic (AEM) Surveys and the Basin Characterization Program. She oversees data collection, analysis, and development of tools, maps, and models supporting SGMA implementation. Katherine holds degrees in Geophysics from Stanford University.

Dr. Jason Gurdak is the Groundwater Management Unit Manager at Valley Water where he has led compliance as a Groundwater Sustainability Agency under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). He has over 25 years of professional experience in groundwater management, hydrogeology, and aqueous geochemistry. Prior to joining Valley Water in 2020, he was a Professor of Hydrogeology at San Francisco State University, a Groundwater Hydrologist with the USGS, and led UNESCO’s global climate change and groundwater program called GRAPHIC. He has authored over 80 publications and is an internationally recognized authority on climate change and groundwater.

Nicole Jacobsen, PG is a Hydrogeologist at Woodard & Curran with over seven years of experience in groundwater and surface water monitoring, data analysis, and tool development using advanced datasets and machine learning. She holds a B.S. in Geology from Texas A&M University and is a licensed Professional Geologist in California.

John Karachewski, PhD, retired recently from the California-EPA in Berkeley after serving as geologist for many years in the Geological Support Branch of the Permitting & Corrective Action Division for Hazardous Waste Management. John has conducted geology and environmental projects from Colorado to Alaska to Midway Island and throughout California. He leads numerous geology field trips for the Field Institute and also enjoys teaching at Diablo Valley College. John enjoys photographing landscapes during the magic light of sunrise and sunset. Since 2009, John has written quarterly photo essays for Hydrovisions.

Annalisa Kihara, PE, is the Assistant Deputy Director in the Division of Water Quality at the State Water Resources Control Board where she oversees several critical programs within her branch, including groundwater monitoring, cleanup, protection, and permitting, as well as sustainable water programs such as recycled water and stormwater capture and use. She brings her strong commitment to equity to her role as the GRA DE&I Officer, serving as a key voice on GRA’s Executive Committee.

Kyle Nordquist is an Environmental Engineer at Woodard & Curran with over three years of experience in water and wastewater system design, data analysis, and hydraulic modeling. He holds a B.S. in Environmental Engineering from the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Gengxin (Michael) Ou is a hydrologic and groundwater modeler at S.S. Papadopulos & Associates specializing in model development, water resources planning, and software applications. He brings strong computational skills and has developed multiple MODFLOW packages and modeling tools.

Tim Parker, PG, CEG, CHG is Ramboll’s groundwater sustainability expert with more than 40 years of experience in California groundwater. He has worked extensively in both public and private sectors and currently supports DWR’s airborne geophysical surveys. Tim is a leader in the groundwater community, including serving as President of the IAH-US National Chapter.

Javier Peralta is a hydrogeophysicist at Ramboll specializing in near-surface and airborne geophysical surveys and their integration into hydrogeologic conceptual models. He holds a Master’s degree in Geophysics from Stanford University and focuses on electromagnetic methods for groundwater characterization.

Maria Pinzon is a geophysicist at Ramboll with expertise in seismic processing, geophysical well-log interpretation, and groundwater geophysics. She integrates near-surface and deep geophysical data into hydrogeologic conceptual models and holds degrees in Geology and Geophysics from the University of Houston.

Angie Rodriguez-Arriaga is a Geologist at West Yost Associates, where she supports groundwater sustainability, hydrogeologic analysis, and data-driven reporting for agencies across California. She is a co-lead of GRA’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Committee and is passionate about uplifting diverse voices in water management. Angie is committed to making groundwater science more accessible, equitable, and collaborative.

Steven Springhorn, PG is a Supervising Engineering Geologist at the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) and leads the Technical Assistance Section within the Sustainable Groundwater Management Office. With nearly 20 years at DWR, he supports SGMA implementation and oversees aquifer characterization efforts, including California’s Groundwater Bulletin 118.

Dr. Paul Thorn is a Managing Consultant and Project Manager at Ramboll with over 20 years of experience in groundwater mapping and management. His work spans hydrostratigraphic modeling, groundwater sustainability planning, and vulnerability assessments across multiple continents. He has served as project manager for DWR’s Statewide AEM program.

Savannah Tjaden is a Water Resources Specialist & Product Manager at Environmental Science Associates (ESA) and a Board Director for GRA. She is passionate about leveraging technology and data to adaptively manage water resources.

CORPORATE SPONSORS

EVENT SPONSORS

COMMUNICATIONS SPONSOR

Stults

Stefanie Shea

Assadi

Meeta Pannu Anaheim, CA

Rivers

Community Water Center working on drought, nitrate, and climate change related drinking water issues. Originally from San Diego, Kjia attended the University of California, Santa Barbara to obtain Bachelor of Arts in Environmental Studies and Political Science. During her time at UCSB, Kjia was to learn about environmental justice issues and vulnerable communities are often left out of the policy making process.