HUM NITIES

THE GRAY MATTERS ISSUE

02 ALGORITHMIC ART by Ganapathy Mahalingam

08 PERSONAL DIGNITY: A TRIBUTE TO THE WORK OF JOHN CROSBY AND LINDA ZAGZEBSKI by Anthony T. Flood

14 THE BEAUTIFUL COUNTRY AN INDIGENOUS GEOGRAPHY by Dakota Wind Goodhouse

18 HOW TO ADULT: A BRAVE CONVERSATION by Dennis Cooley

26 HOW LOCAL SCHOLARSHIP CAN HELP: BUILDING BETTER KNOWLEDGE ABOUT IMMIGRANTS AND REFUGEES IN WESTERN NORTH DAKOTA by Karen Hooge Michalka

30 HUMANITIES CHAUTAUQUA by George Fein

38 THE PRINCIPAL AND THE PRESIDENT: DINING AT THE WHITE HOUSE by Charles Everett Pace

42 CHAUTAUQUA & CHAT SERIES

HUMANITIES NORTH DAKOTA MAGAZINE is published by Humanities North Dakota.

To subscribe, please contact us: 701.255.3360 info@humanitiesnd.org humanitiesnd.org

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this magazine do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities or Humanities North Dakota.

50 THE WRITE STUFF by Rebecca Chalmers

The Humanities North Dakota Magazine has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom.

Humanities North Dakota (HND) thinks of lifelong learning in the humanities as a quest to find deeper meaning and purpose. We view our members as heroes, venturing forth into the landscapes of the mind and soul on personal missions of discovery.

According to Joseph Campbell’s seminal work on comparative mythology and psychology, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the hero’s journey starts with a call to adventure. A herald summons the protagonist to an “awakening of the self” that, “whether small or great, and no matter what the stage or grade of life, the call rings up the curtain, always, on a mystery of the transfiguration.” The board and staff at HND believe it is our mission to serve as heralds on your mission. We do so, even though Campbell’s description of the mythological courier isn’t terribly flattering: “The herald or announcer of the adventure, therefore, is often dark, loathly, or terrifying, judged evil by the world; yet if one could follow, the way would be opened through the walls of day into the dark where the jewels glow.”

As modern-day heralds, announcing opportunities to engage in transformative learning, we point out guides you can approach to aid in your quest for wisdom. These are the scholars at the heart of every HND program. As mentors they bring their expertise to bear on everything human beings have achieved, struggled for, and suffered from, across time and distance. From the facts of history to the fiction of literature, the humanities are encounters with the fundamental questions of human existence. All heroes must find their own answers.

Thank you for being our heroes! Godspeed on your journey!

Much heart, Brenna Gerhardt

Executive Director & Fellow Lifelong Learner

p.s. No journey is complete without companions. We hope you find ample opportunity to enjoy the company of fellow travelers along the way through in-person events or online class discussions. I know my lifelong learning journey has been enriched by those of you I’ve met along the way.

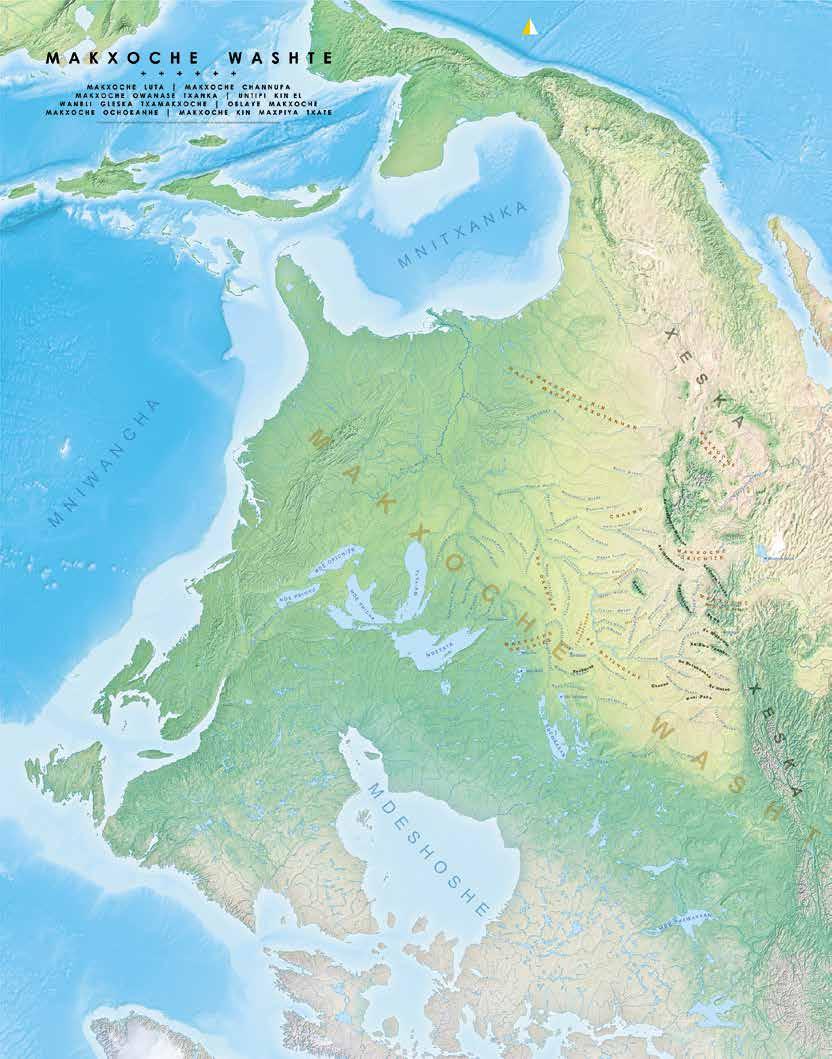

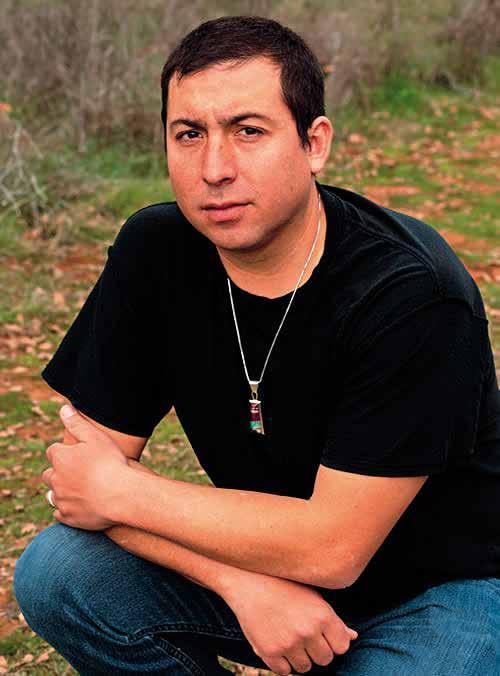

Dakota Wind Goodhouse, born and raised on the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation, created this map with his own people’s place names.

Goodhouse has a B.A. in Theology and a M.A. in History, and is a PhD candidate in NDSU’s history program. He edits and maintains the history blog The First Scout. Follow him on IG @thefirstscout.

Algorithmic Art is a collection of works, all created in 2022, that explores the frontiers of using algorithms to create works of visual art. All the works in the show are created using the programming language Processing and image processing tools.

Each work’s narrative is the actual algorithmic code that created it. This algorithmic code is composed of elements that reveal a more conventional narrative within it, hidden and intermittently revealing itself. Taking its cue from the ancient Indian system of Katapayadi, where numbers are assigned to letters, and computations are performed through text and poetry, this process of creating visual art explores symbol systems in a critical new way as well as how they can be processed using multi-layered techniques to create meaningful expressions of visual art.

Unlike conventional narratives that evoke meaning, these symbolic narratives actuate the creation of visual works of art. Then a conventional discourse emerges for the visual work that has been generated.

List of works:

1. proportional cascade

2. pourquoi Jessica (refined) 1

3. pourquoi Jessica (refined) 2

4. piety

5. da te tum ta

This a playful exploration of the proportions in the musical scale as a cascade of shapes. size(3000,3000); background(0); for (int i=0; i<500; i+=5) { fill(188, 175, 207); ellipse (random(height), random(width), i, i*1.732); fill(83,86,90); ellipse (random(height), random (width), i, i*1.414); fill(254,221,0); ellipse (random(height), random (width), i, i*1.5); fill(255); ellipse(random(height), random (width), i, i); fill(255,0,0); ellipse(random(height),random(width),i,i*0.5); };

saveFrame(“proportionalCascade.jpg”);

These symbolic narratives actuate the creation of visual works of art.

1 & 2

These two pieces are a tribute to North Dakota artist Jessica Wachter and reflect transformations based on algorithms and image processing.

PImage img; int jessica=10; int wachter=23; float art=5.0; size (3000,3000); background(0); img = loadImage (“jessica4.png”); for (int x = 0; x <= height; x += jessica) { for (int y=0; y <= width; y += wachter) { rotate (art); translate (jessica, wachter); image (img, random(x), random(y)); art += 10; }}; saveFrame(“pourJessica.jpg”);

This algorithmic piece is a tribute to the painter Piet Mondrian. It takes his name in a poetic form and is a paean to his minimalist piety.

size(3000,3000); background(255); for (int i=0; i<=height; i+=(height*0.2)){ fill(255,0,0); rect (0,random(i),random(i),random(i));} for (int i=0; i<=width; i+=(width*0.3)){ fill(255,255,0); rect (random(i),0,random(i),random(i));} for (int i=0; i<=(height/2); i+=(height*0.1)){ fill(0,128,0); rect (0,random(i),random(i),random(i));} for (int i=0; i<=(width/2); i+=(width*0.1)){

fill(0,0,255); rect (random(i),0,random(i),random(i));} fill(0); for (int i=0; i<=width; i+=(width*0.2)) { rect (random(i),0,random(50),height);} for (int i=0; i<=height; i+=height*0.2){ rect (0,random(i),height,random(50));} rect(width-15,0,15,height); rect (0,height-25,width,25); saveFrame(“mondrian.jpg”);

The work’s narrative is the actual algorithmic code that created it. This algorithmic code is composed of elements that reveal a more conventional narrative within it, hidden and intermittently revealing itself. Taking its cue from the ancient Indian system of Katapayadi, where numbers are assigned to letters, and computations are performed through text and poetry, this process of creating visual art, explores symbol systems in a critical new way, and how they can be processed using multi-layered techniques to create meaningful expressions of visual art. The title of the artwork is a musical play on the words date (da te), datum (da tum) and data (da ta). All these types of information are part of the algorithmic code that generates the artwork. All the information in the code that generates the artwork are pertinent to North Dakota State University. The algorithm is implemented in the programming language called Processing. l

GANAPATHY MAHALINGAM is a Professor of Architecture at North Dakota State University. He has been a resident of North Dakota for nearly 29 years and can be considered a native Fargoan. Ganapathy has a wide-ranging interest in the arts, comprising architecture, visual art, music, poetry and philosophy.

int ndacAge=70; int ndsuAge=52; int doctoralDegrees=52; int undergraduateDegrees=146; int graduateDegrees=87; int certificates =210; size (3000,3000); background(0); fill (0,102,51); for (int y = 0; y <= height; y += ndacAge) { for (int x = 0; x <= width; x += ndacAge) { ellipse (random(x),random(y),random(ndacAge),random(ndacAge));}}; fill (173,216,230); for (int y = 0; y <= height; y += ndsuAge) { for (int x = 0; x <= width; x += doctoralDegrees) { ellipse (random(x),random(y),random(doctoralDegrees),random(ndsuAge));}}; fill (255,204,0); for (int y = 0; y <= height; y += ndsuAge) { for (int x = 0; x <= width; x += ndacAge) { arc (random(x),random(y),random(undergraduateDegrees),random(graduate Degrees),radians (doctoralDegrees),radians(certificates));}}; saveFrame(“datetumta.jpg”);

What does it mean to say that each human being is a person, and what makes a person different from everything else? These questions, raised by John Crosby and Linda Zagzebski, have framed in a substantive way the horizons of my philosophical life. As a student of both thinkers, who are both now retiring from the teaching side of the profession, I wish to take a moment to honor them by offering a glimpse into their insights. I will begin by proposing a couple of general thought-experiments that aim to motivate the issues both thinkers address, proceed with a brief history of the intertwined notions of person and dignity, and then turn to the thinking of Crosby and Zagzebski.

Reflecting on how and why we value and love people in comparison to other kinds of things is a practical way into thinking about the nature and dignity of personhood. Suppose you are reading the newspaper, and I walk by, grab it, tear it up, and throw it away. It is reasonable to suppose that you are going to be annoyed at and upset with me. I destroyed something that you consider, at least in some small way, valuable. To make it up to you, I go out, get another copy of the newspaper, and give it to you. You still are going to be put off by the whole situation, but your demand for restitution should be satisfied—I have replaced

what I took from you. This little scenario raises the question of why another copy serves as fair recompense, for the destroyed object is gone forever. Regardless of what is offered in its place, you will never get the original back. The short answer is that we do not value such things as newspapers in terms of their individuality but, rather, only for their replaceable or shared content. One copy of the paper is as good as any other. In a real sense, whatever interest we have in the individuality of the thing is a by-product of our primary concern for the shared content, and we value the individual copy merely as a means of accessing the content. However, this valuation does not apply with persons—at least not in its entirety. If we lose a loved one, no human being, no matter how similar, will ever serve as an adequate substitute. We love our spouse, children, friends, etc. in a real way because of their individuality, which is why they cannot be replaced.

Consider another thoughtexperiment: imagine that you get engaged to be married. It is very likely that you will be asked “What makes you think this person is the one for you? What makes this person special? (and finally) Why do you love this person?”

Depending on who is asking, these questions might put you a bit on the defensive—as if you have to justify or prove that you are making the right decision. You proceed to

We love our spouse, children, friends, etc. in a real way because of their individuality, which is why they cannot be replaced.

make a case that this person, out of the pool of so many possibilities, satisfies the criteria as the right choice and worthy of the ultimate commitment of love. You are probably going to answer by offering a list of loveable qualities: Billy is smart, caring, kind, funny, handsome, hard-working, and on and on. However, qualities are repeatable and replaceable, both individually and in combination with other qualities. Lots of people are smart, caring, kind, etc. These qualities cannot be the full explanation of why you have this singular love for Billy.

One might suggest it is merely because you have a history with Billy but not with other similar people. Perhaps, but this answer does not seem true to experience, as he does not seem interchangeable with the other people. Connecting this to the previous reflection, Billy’s individuality is crucial to your love for him. Your love extends beyond just the qualities and goes to that which makes Billy a unique person, distinct and irreplaceable by anyone else. The question of why you wish to marry this person sheds light on a complexity about persons, their value, and why we love them. Crosby and Zagzebski’s analyses seek to explain this complexity and offer a clearer way of thinking through these sorts of things. I will frame their thinking by first presenting a very brief overview of the history of personhood and dignity.

The cradle of western philosophy lies in the ancient Greek world, particularly in Athens. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle asked questions about human nature and developed sophisticated accounts articulating what it is that makes us human beings. Aristotle famously defines us as “rational animals,” meaning that we share the general physiological and biological characteristics of other living things, but we also have specific rational powers and characteristics, such as self-knowledge, deliberate action, sophisticated language, and the like. Particular

human beings are just that—particular beings who have human nature and thereby exhibit these potentialities and abilities. Insofar as general human nature is valuable, then an individual instance of that nature also shares some of that same value.

The word “person” became the preferred way of referring to individual human beings. The term itself is taken from a theatrical context— actors wore masks to convey different characters and personalities. The Latin word for mask is persona. Roman law picked up on the term and used it to convey aspects of citizenship. Within theological debates regarding God as a Trinity and Christ as a being with two natures, thinkers adopted and adapted the term “person” to convey these relationships. Drawing from this usage, the sixth-century philosopher Boethius offers what becomes the standard definition going forward: a person is an individual substance of a rational nature. Notice that personhood is not tied explicitly to human nature but to any rational nature. Human beings are persons, but there can also be non-human persons.

The thirteenth-century thinker, St. Thomas Aquinas, insists that personhood signifies what is most perfect in all of nature by reason of dignity. In the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant defines the value of dignity in comparison with another kind of value, namely price. He remarks that dignity is a kind of value wholly distinct from price. In the case of a thing whose value is measured by price, there is always something that in principle can be adequately substituted. The worth of the thing is determined, in effect, by practical, economic considerations. We may call things “priceless,” but we usually do use this term literally. Our great-grandmother’s china cabinet may be “priceless,” but if someone were to offer us twenty million dollars for it, we would sell it in a heartbeat. Dignity, on the other hand, is a value incommensurate with price. There simply is no adequate substitute for this condition or attribute.

A spouse, child, friend, etc. is priceless in a literal manner—there simply is no other thing, collection of things, or amount of money that could serve as an adequate substitute. In other words, a person is irreplaceable and not interchangeable with anything else—not even other persons.

In the moral sphere, Kant formulates the Principle of Ends, namely that it is wrong to treat persons as a mere means to one’s own ends; persons are ends-in-themselves. Because human persons have dignity, there are moral implications concerning how they should and should not be treated. These philosophical developments have had a sizable influence on how the broader world thinks about these issues. In the political sphere, for instance, the connection of dignity to action is usually expressed in terms of rights. For instance, the Preamble of the United Nations “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” begins with “Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” (Obviously, one could say much more on the development of these ideas, but this suffices for our present purposes.)

In The Selfhood of the Human Person, Crosby explores what it is about the human person that accounts for dignity. His account focuses on two aspects: incommunicability and subjectivity. Communicability, in the metaphysical sense of the term, suggests the ability of a nature or a quality to be repeated or multiply instantiated. All squares are squares insofar as they somehow share a common/communicable nature. Moreover, if all particular squares were destroyed, that destruction would not destroy squareness— particular squares could exist again in the future. Communicability at the general level allows for repeatability at the particular level, which in turn is why such things can be adequately replaced.

Incommunicability, by contrast, conveys that which is unique and individual as such. It cannot be repeated or replaced. All individual things have incommunicability as individuals. However, what we value about the vast majority of things is not their individuality but their communicable nature. To use the earlier example, we value the copy of the newspaper in our hands, but what we value is its ability to convey common content—any copy of the same edition will do just fine. We do not really care about the individuality of the newspaper, which, again, serves merely as a means of expressing the communicable content. Persons, though, are different. We do not value our friend just because she is a human being; rather, we love her as an individual. We love her individuality as such—it is not just a means of expressing the communicable content of human nature. Our friend, in a real and substantive way, is unique and irreplaceable. This is why loss of a friend leaves a void that cannot be filled with another “copy” of human nature.

800-338-6543

info@humanitiesnd.org humanitiesnd.org

Crosby observes that a key distinguishing mark between the incommunicability of nonpersonal things and personal incommunicability is subjectivity. Each person has a unique interior life—their own first-person conscious experience of the world and themselves. Put simply, each person is a unique subject. We, of course, first experience this in ourselves, but love and friendship tend to give access to another person’s self-experience. Crosby remarks that it is not until we sympathetically enter into the other person’s subjective self-experience—experiencing a person as she experiences herself—that we truly

Each person has a unique interior life their own first-person conscious experience of the world and themselves.

experience the other precisely as person.

To summarize Crosby’s thinking, incommunicability and subjectivity are vital to what a person is. We can love humanity with all its marks and potentialities, but the love of persons is inherently a love of individuals. Moreover, the dignity of persons springs from each one’s subjective self-experience and irreplaceability as rooted in incommunicability.

Zagzebski, a prolific author best known for her work in virtue theory, treats the nature and value of personhood throughout many of her inquiries. She explores the subject of dignity in several of her works, most recently in The Two Greatest Ideas: How Our Grasp of the Universe and Our Minds Changed Everything. She, in part drawing from Crosby’s investigations, affirms that persons have an incommunicable subjectivity. She attends to these considerations by centering on two sources of value in human persons. In effect, the term “dignity” is more complex than at first glance, as we can use it to speak to two distinct kinds of value. Interestingly, the values themselves cannot be accounted for in the same way: one is infinite value, which is qualitative and comparable, while the other is irreplaceable value, which is non-qualitative and incomparable. She contends that human beings, due to their human nature, are infinitely valuable. In other words, due to human nature, each particular human being has great value.

Let us use Aristotle’s definition of human nature as rational animals to show how this concept works. Rational animality is more valuable than, say, bacterial nature. Consequently, particular human beings have greater value than particular instances of bacteria, all else being equal. Moreover, we can employ this metaphysical claim as a premise within our ethical reasoning. Thus, it is permissible, if not at times obligatory, to use antibiotics to kill bacteria to improve the life of a

human being because human nature has greater value than bacterial nature. Human beings are valuable because they are human beings, or to put it in Crosby’s terminology, we are valuable due our “communicable” content. However, the value, infinite or otherwise, of the qualities of human nature cannot be the source of incomparable, irreplaceable value. This is the case for at least two reasons. First, “infinite” can be compared with “finite,” and infinite is better than finite. Second, as we have been discussing, human nature is eminently communicable and human beings repeatable—that is the nature of natures. In fact, any quality, any qualitative mode of being is repeatable and therefore replaceable. So, assuming persons have infinite value, the source of this value cannot be the whole story of dignity, as infinite value is qualitative by nature.

Looking at this from the opposite perspective, persons also have irreplaceable value. Since the value of irreplaceability cannot be grounded on what is repeatable, and natures and qualities are inherently repeatable, the ground of irreplaceability must be something non-qualitative. Zagzebski points to the subjectivity of the person, specifically and inherently irreducible, as the key non-qualitative part of us that explains irreplaceability. By irreducible, she means that our experience of the world is inherently our own—it is inescapably first-personal. It seems evident that human beings experience things very similarly, but your experience is yours and mine is mine—neither of us can reduce our experience to those of others. As Crosby notes, we can sympathetically enter into another person’s subjective life, but we cannot literally have their experience.

To summarize Zagzebski’s account, dignity can be thought of as expressing both infinite and irreplaceable value. Yes, we are valuable because we are human beings by virtue of having human nature, but that is not the full story; each of us is valuable also because each of us is a unique self—

there is no other single thing, collection of things, single human being, or collection of human beings that can replace any of us.

To return to the question of love, why, then, do we want to marry Billy? Yes, because of the long list of his good qualities. These might even have an infinite value in themselves, but they are also all very much repeatable. Many people could fit the bill. However, he is also an individual—not just an individual who expresses qualitative modes of being, but an incommunicable, non-qualitative self. Of course, we do not want to drive too great a wedge between a person and her qualities. Both Crosby and Zagzebski speak to this in their fuller accounts. However, the point is that qualitative modes of being do not capture everything and probably not even that which is most significant in terms of why we love others and how we account for their dignity.

To conclude, if there were ever topics whose importance is always both perennial and timely, no two would rank higher than personhood and dignity. Of course, this does not mean that they are easy to grasp. Famously, St. Augustine once remarked that he knew what time was, until someone asked him what it was. Human personhood, dignity, and personal love are like that, too. This is why I am grateful to the work of John Crosby and Linda Zagzebski. They offer great insights, helpful distinctions, and compelling accounts on these and other topics that have benefitted me and many others and, I hope, many more to come. l

ANTHONY T. FLOOD is a Professor of Philosophy at NDSU. His research interest focuses on the themes of love and friendship in the thought of Thomas Aquinas. He resides with his wife and three children in Moorhead, MN.

There is no other single thing, collection of things, single human being, or collection of human beings that can replace any of us.

by Dakota Wind Goodhouse

by Dakota Wind Goodhouse

My name is Dakota Goodhouse. I often wondered if I would ever see a map with my own people’s place names. I’m in my forties, and I realized if I ever wanted this resource I had to make it myself. I needed the resources, too. The people at The Decolonial Atlas got me started, but it was Bob Petterson and his large, free, textless geography of North America that made me want this resource free and available to the public. I am grateful to my grandparents and extended relatives who shared places with me, too.

The Corps of Discovery called the source of the Missouri River “The Three Forks.” The Lakhota people also believe that this site is the source of this great water, but disagree where the river ends. The Lakhota know the Three Forks as Mnithanka, or “The Great Water.” When the one river leaves its headwaters, the Lakhota call it Mnisose, or “The Water-Astir.”

The Water-Astir flows through the landscape in a great sinuous line. The Lakhota observed that where other streams converged with The Water-Astir, the water swirled. These swirls kicked up sediment and contributed to the river’s brown muddy appearance. It was a dangerous river. The only safe crossings lay upstream from each confluence.

Lakes and rivers live and breathe. Every kind of water has spirit.

In the spring, the Lakhota broke camp and moved from the floodplain of the Missouri River to the high plains. Throughout the summer they moved from headwater to headwater. Sometimes they camped at the forks of confluences for trade. Winters were the longest season, and so they prepared for the following winter all summer. They celebrated winter’s return with a snowshoe dance at first snowfall. They wintered on the forested floodplain. In the heart of winter they drew water from beaver holes in the ice; they gathered red willow to mix with their tobacco. In late winter, or early spring, the Dakhota tapped maple trees for sap; the Middle Dakhota tapped white birth for sap; the Lakhota tapped boxelder for sap.

The creation story of the Ocheti Sakowin, the Seven Council Fires (i.e. “The Great Sioux Nation”), recalls that Inyan, The Stone, drew his own blood forth from his veins, the very water of the world, so that life could begin. All that lives, breathes. Lakes and rivers live and breathe. Every kind of water has spirit. The spirit of water the Lakhota call Wiwila. The flowers, grass, and trees that grow along the water have spirits, too, which they call Chanotila. The Lakhota say that the stone lives and breathes, too, and the spirit of stone they call Tunkan.

On the Great Plains, the Mnisose flows southerly. The direction this stream flows informs the south-oriented worldview perspective of the Ocheti Sakowin. All but one river in the landscape flows south. The Red River of the North. Inktomi, the Trickster, convinced this stream to flow in the opposite direction. But south, that is the direction the spirit goes when its journey here is done. The Mnisose is reflected in the heavens in the Spirit Road, or the Milky Way. Death is the great river that separates one shore from the other.

The Mnisose meanders across the vast open plains. Many rivers converge with it. Many Ozhate at every confluence. So many places to trade resources with other peoples. Sometimes conflict broke out, but many times, too, did people adopt a former enemy in the beautiful Making of Relatives Ceremony. Oftentimes, young men and

young women found love in a former enemy and married.

At one great confluence, where the Haha Wakpa, or Waterfall River (i.e. the Mississippi River), it is the Ocheti Sakowin perspective that the Haha Wakpa converges with the Mnisose, not the other way, and the great Mnisose flows even more directly south. When this great river reaches the end of its journey, it joins a great water they call Mnithanka, the Great Water, better known as the Gulf of Mexico.

For the Lakhota north of the Cheyenne River, the new year came in spring when the ice broke, when the geese returned, when the trees budded, and when the herald of the new year, the western meadowlark, sang aloud across the open plain, “Oiyokipi! Omaka Techa!” or “Take pleasure! The New Year is Here!” Even the wind that blows across the open plain in spring is more than just a spring wind. No, the Lakhota call it Niya Awichableze, or “The Enlightening Breath Upon Which All Life Returns.”

Aside from the vast open plain, other features of the landscape are rolling hills, plateaus, and broud coteau. The Lakhota have the phrase Pahayata, or “To Go To The Hill.” It can reference scouts ascending a summit in search of signs of Tatanka, the Great Ones; it can mean that an individual is going on a vision quest and is called to take oneself to a summit.

The Lakota have many names for a landscape. The Little Missouri River Country for example may be called Makoche kin Chansotka Wakpa, or the Country of the Towering Tree River; it might also be called Makosica, or the Pitiful Country. Citizens of North Dakota are inclined to call this same sacred landscape Theodore Roosevelt National Park, or the North Dakota Badlands.

A country that is drained by one main stream is named for that stream. The Lakhota might even have more than one name for a stream. They call the Little Missouri River by another name, Wakpa Chan Soka, or the River of Thick Timber.

Just as headwaters, lakes, rivers, summits, ranges, and conflicts might be known by more

than one name, so, too, do the Ocheti Sakowin know the vast open plain by more than one name. They call it Makoche Waste, or the Beautiful Country; they call it Makoche Luta, or the Beautiful Red Country; they call it Makoche Channupa, or the Land of the Sacred Pipe; they call it Makoche Owanase Tanka, or the Land of the Great Hunt; they call it Wanbli Gleska Tamakoche, or the Land of the Spotted Eagle; they call it Oblaye Makoche, or the Plains Country; they call it Makoche Ocokanhe, or the Land in the Middle; they call it Untipi kin El, or the Land in Which They Live.

The land is shaped by wind. The language of the indigenous peoples was shaped by the wind, too. The wind is part of the culture. “Taku sica

owas’inla kahwog iyanyin kte,” or “All the bad things are blown away with the wind.”

Is the Great Plains that the Ocheti Sakowin know so different from the one you know?

Welcome to the Land of Sky and Wind. l

DAKOTA WIND GOODHOUSE was born and raised on the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation. Goodhouse has a B.A. in Theology and a M.A. in History, and is a PhD candidate in NDSU’s history program. He edits and maintains the history blog The First Scout. Follow him on IG @thefirstscout.

Even the wind that blows across the open plain in spring is more than just a spring wind.

by Dennis Cooley

by Dennis Cooley

Socrates said that “An unexamined life is not worth living.” His claim is plausible–and might be a moral imperative when people are losing touch with democratic values and when social strife abounds. Given what many of us are seeing happen to our neighbors, to community, and to our country, this advice is right on target for the here and now.

Most pithy advice sounds really good to the ear, but, in general, practical concerns must be considered to turn a saying into action. What does the quote actually mean? What does it require us to do in practice? In this particular case, are all life’s aspects worth evaluative effort? As any reasonable person knows, some things are so trivial that to spend time examining them is a gross misuse of reason, a condition which makes us a unique species, able to conceptualize new realities and the methods to bring them about. Delving deeply into why one likes a nice slice of onion on a liverwurst sandwich, for example, would be far less valuable than looking into whether one’s valuation of others based on perceived conditions of race, sex, age, or other identifiers can ever be morally legitimate. Our hidden biases provide an excellent area for exploration, especially if doing so helps us to become better people. We can then formulate some sort of plan in order to manage–if not eliminate–those flaws and the questionable actions they cause.

Although people’s belief systems do not tell the entire story of who they are, beliefs certainly can say a lot about their identities and lives. Thus, beliefs give us a good place to begin the examination that Socrates suggests for a life worth living. It should go without saying that informed beliefs are much better than misinformed beliefs when it comes to making our lives

flourish. If we believe in baseless conspiracy theories created by anonymous internet writers, for instance, then we might shoot up a pizza place trying to find an imaginary pedophile ring.

Greater accuracy and exposure to what is real, on the other hand, helps us to analyze situations more precisely, concisely, and completely. It enables us to separate reality from illusion–and delusion–when it comes to identifying actual problems, their root causes, and their potential solutions. It enables resources to be allocated to the improvement of both individual and societal lives. It prevents the enshrinement of tribalism and the Us-versus-Them thinking that unravels the social bonds essential for us to be We the

People. For these and other benefits, there is at least some good reason to think that we are obligated to scrutinize very carefully what we believe since those propositions impact our very existence.

Our hidden biases provide an excellent area for exploration, especially if doing so helps us to become better people.

If examining our lives were easy, most everyone would have done it by now. Any rational or reasonable person who is interested in having a better existence would automatically be motivated to invest a minor amount of resources for what would likely net big gains to individual and social worth. Think of it like a dieter who must merely give up a food that has already fallen out of favor to drop a few pounds. So, too, would any prudent person check beliefs for falsehoods and then replace them with beliefs that far better reflect reality. In fact, the big gain with little pain would be so rewarding that it would soon become second nature. We’d be doing it all the time.

But the fact is that many of us rarely, if ever, examine our lives in the way that Socrates mandates. One problem: such an examination both challenges and threatens our sense of ourselves. Consider something that has likely happened to each of us. Moral failures in others sometimes require us to create a teachable moment, especially if we are responsible for their moral development, as we are for our children who need a lesson. Instead of viewing this moment as our attempt to help identify what was wrong and how to make amends, our child perceives in the questioning of his judgment and behavior that we have cast aspersions on his

character and actions. He thinks we are saying he is a bad person and lashes out as a result. It hurts his self-esteem and selfvalue.

What does this reaction mean for self-examination? Rigorous self-examination is difficult, in part because the beliefs, values, and principles under inspection are usually central to the core of who the person thinks he is. That is, they are part of how he identifies himself as the unique and valuable being he is in his natural and social environments, and those are now under critical scrutiny. Any attempt to alter them is viewed as an attack on his self-value. Even if they are merely important to his identity, having these characteristics and deeming them defective enough to need replacement implies that the person is not as good as others in his social circle and the community. If the person examining his life believes that these are his essential characteristics, then it is even more intimately tied to his existence and value. That is a hard reality to face. These threats to his value and existence are why there is so much resistance, fear, and anger when someone is challenged on issues linked to his perception of his core being. And that is something no one wants to happen – it hurts too much.

There is a different threat as well. Being a member of a herd is a natural and learned desire of most, if not all, people. Homo

sapiens result from a long line of evolutionary adaptations. We are social animals who naturally want to and work to belong to a group for the benefits that the group confers. And such membership is easiest when the group is a bunch of people just like us. In our complex society, few of us are wholly self-sufficient. Some of us like to think of ourselves as wholly self-made, but that idea is a myth. We all stand on the shoulders of others and their accomplishments. We need others in order to obtain the basic essentials of life, such as food, shelter, and emotional support in positive relationships, but also for those things that make life better but are unnecessary–although they might sometimes seem to be essential to those hooked on their convenience. All of these goods require us to use the work of others, as well as cooperating with them in various interdependent, complex relationships. Without them, our lives would be nasty, brutish, and short. As prudent people, therefore, we need to be solidly ensconced in the herd.

Challenging one’s core beliefs can threaten that herd membership. To be a perceived and actual group constituent requires a sufficient and necessary number of shared beliefs, values, principles, and lived experiences with other members. As anyone who has migrated into a new culture or society can readily attest, there

is automatic bonding between people when the newcomers are deemed to be “one of us” by the area’s natives. Being one of us might be based on physical appearance, but it also depends on how people interact with each other. I, for example, was considered to be rude when I first came to North Dakota because I did not understand that the length of time between finishing one sentence and beginning the next here is different from where I had lived before. When a North Dakotan was using a herdspeech convention, I mistakenly thought it was my turn to keep the conversation flowing. Often, I began to reply to a person before she had finished her entire line of thought. The rudeness was unintentional on my part. The social rules where I’m from have very short pauses between the end and beginning of sentences. Not responding quickly enough to someone from western New York appears to be dismissive or as if we’ve disengaged in the conversation. (I’m pleased to say that I’ve learned this speech rule, although for some reason, I still might be considered to be discourteous by being a very direct speaker in the land of indirect communication.)

Besides language conventions, there are myriad other ways we use to tell if someone is in-group or outgroup: their dress, diet, and etiquette can also signal

differences. And if one or more of these are detected by in-group natives, social and psychological barriers can be constructed to keep the outsider from fully entering into that herd.

To raise questions or show differences by critically examining one’s beliefs might represent some perceived threat to the group, especially if the beliefs are essential to herd membership. For newcomers to the community, it proves that they are out-group. Worse yet, for in-group people, obeying Socrates’s advice for these shared beliefs, customs, and psychological frameworks could very well banish the person to wander alone in a native land. There is, therefore, a strong incentive to peg one’s beliefs and values to the group’s, and never, ever, make waves by saying, “You know, I think we might be wrong about this.”

As Socrates did before him, John Stuart Mill argued that every person is obligated to scrutinize his values, beliefs, principles and any other psychological state influencing his worldly interactions and making him who he is. Mill thought that there were three types of beliefs that people could hold: wholly true, wholly false, partially true, and partially

false. The largest set contains beliefs that are partially true in one aspect and partially false in another. That shouldn’t surprise those living in the real world: we, as imperfect creatures with finite knowledge and information, do not often have the ability to know the truth and nothing but the truth about any proposition, especially the case if these beliefs are the complicated, entangled ones we find in the abortion, euthanasia, and other such debates. These issues involve a lot of unknowns and unknowables, which, of course, make it virtually impossible to get the entire truth precisely and completely right. Thus the prudent standard we should use for our empirical world beliefs is the probably and plausibly true with a small “t,” not the absolutely certain True with a large “T.”

Accepting our finite knowledge and infinite ignorance requires us to adopt “fallibilism.” Fallibilism is the motivating, critical-reasoning mental framework in which we know that we could be wrong even when we most strongly feel certain about something. Being a fallibilist is liberating: it makes adherents more humble and interested in examining beliefs. Instead of being overly confident and, therefore, not seeing a reason to question one’s belief, there is always the need to

We all stand on the shoulders of others and their accomplishments.

critically investigate everything we think. Instead of being overly worried that being wrong says something derogatory about our worth to ourselves or to others, it becomes more important to find out when we are wrong and to learn from the mistake. Truth is more important than ego and much more useful in general to achieve worthwhile goals because we know that being wrong is merely a mistake, not a character flaw signifying anything about us, who we are or how we should be valued by others who are in the same potentially dubious position.

For Mill, the best place to perform a thorough examination was in a democratic marketplace of ideas. In this realm, ideas are proposed and then critically reviewed for their strengths and weaknesses by many diverse people holding different beliefs, values, and principles. With honest brokers being involved in the process–and the dishonest ones as well– Mill thought that a position could more effectively shed itself of falsehoods and draw closer to the actual truth. One person’s lived experiences, for example, could act as a check on what is too theoretical and unlikely to be efficiently obtained and achieved in the actual world. In response to a mass shooting in a grocery store in a primarily

Black neighborhood in Buffalo, one activist demanded that the grocery store chain demolish its store and build a new one.

TOPS replied that it could not afford to make such a gesture, and it had already disposed of all the store’s contents and totally redesigned the store. More importantly, if the store closed, the underserved neighborhood in which it was located would lose its only access to a grocery store that others might take for granted. It would, in effect, create a food desert.

The marketplace’s buyers and sellers of ideas use criticalreasoning tools: the Principle of Charity and Questions of Meaning Come before Questions of Truth. The practical idea behind the latter is that it is a waste of time to try to determine if a claim is true or false without first knowing what the claim means. If a college instructor, for instance, makes remarks regarding his students being hot, then it is vital to find out how “hot” is being used here. If it merely means that the students are in a classroom with temperatures over 100 degrees, then nothing untoward is happening. In fact, the utterance hopefully indicates that the teacher thinks something should be done to help the students. If, however, “hot” is the

slang for finding the students attractive, then it might be time to have a serious discussion of appropriateness and what is involved in the teacher-student relationship–which should always be focused solely on learning and not dating.

The Principle of Charity is also useful in drawing closer to the truth, with the added benefits of respecting all speakers and their ideas and instantiating what free speech has always been intended to be and do. Although many conflate an idea’s source with the idea’s worth, even the worst people in the world can be right about something. This Principle recognizes that reality. It requires the strongest case be made for any claim or argument, regardless of one’s feeling about what that claim or argument is. It does so, in part, because a person could be wrong and the truth is more important than hurt feelings.

The Principle works in this way. First, each speaker is respected as a person with something important to say. This step helps evaluators focus on the ideas and not the personalities involved. After that, whatever is under market consideration should be fortified by making it as probable and plausible as possible. By creating only the best arguments, we don’t ignore real challenges by wasting time knocking down a strawman–which can, I admit, provide a kind of cheap satisfaction and, apparently,

Being a fallibilist is liberating: it makes adherents more humble and interested in examining beliefs.

does draw in a lot of revenue for cable news. Next, both the strengths and weaknesses of the strongest argument are identified and fairly weighted. Although this step would appear to be obvious, many of us tend to put our thumb on the scale in favor of those arguments and claims we favor. We neglect our positions’ weaknesses and overstate their strengths, while devaluing an opposing viewpoint’s plausibility and probability and overemphasizing its weaknesses. But this is not the way to seek the truth. Truth is about the facts–the latter make our beliefs true or false-and facts and truth do not care about a person’s feelings. Finally, the person engaged in the critical reasoning draws a conclusion based on the evidence alone. Is the argument proven on its own grounds and in comparison to competitors? Is the conclusion at least plausible and probable? If so, then, again, regardless of what one wants to be the case, intellectual honesty requires us to go where the evidence leads. If we are right, then we can go on our way knowing we have the information we need to make the best decisions and do the right thing in the circumstances. If we are wrong, then we acknowledge that, in part, by changing our beliefs to coincide with the more justified conclusions.

Over time in this dynamic, democratic marketplace, ideas, beliefs, mental states, and critical

processes would be refined until they were good enough to be useful in achieving the desired outcomes. Of course, the worth of a desired outcome would also have undergone the same democratic winnowing and improvement process to test its mettle.

My Grandpa Meyers once asked me if I knew the dirtiest word in the human language. Being a rather unworldly 14-yearold, I admit it was very, very intriguing to learn more. Although not titillating in the expected way, it turned out that the naughty word was “religion.” My grandfather explained that no other uniquely human endeavor had caused as much injury and suffering to people, animals, and the environment as those pursuing their religious beliefs, especially if there are two or more herds who each think that their god wants them to stamp out members of any competing religion. Making matters worse, many religious people use faith

alone to justify their beliefs and actions–not rationality, which concerns itself solely with going wherever the data takes us. Faith-based belief systems make it extremely difficult to change adherents’ perceptions because evidence does not have the authority it carries in the rational debate of an efficiently working marketplace of ideas. In fact, at times, there is a point of pride and superiority assumed by those who reject data in favor of pure faith, as has happened by both sides over COVID matters. In some cases, we might be justified in thinking that faith and membership in a religion is more central to our identity than being a rational person trying to find fact-based truths.

Let us pull out all the stops and examine an apparently innocuous religious belief using the Principle of Charity and Questions of Meaning. Of course, what is written here might cause a bit of controversy and even draw some ire. The intent of this exploration is not to spite anyone, but to show both how this process of examining one’s core beliefs, and therefore one’s life, works and to highlight

... no other uniquely human endeavor had caused as much injury and suffering to people, animals, and the environment as those pursuing their religious beliefs ...

how difficult it is to challenge “sacred cows” that form our central being and thinking processes.

We begin with the 1988 WWJD? fad. For those who do not remember, WWJD? stood for What Would Jesus Do? I’m not sure why it caught the fancy of Americans–much as pet rocks were a bewildering, big-ticket item in the 1970s–but it was impossible not to see someone wearing it on a t-shirt, wristband, or some other merchandise.

When this actual question is critically examined, a puzzle appears as soon as a Questions- of-Meaning-Comebefore-Questions-of-Truth approach is applied. In order to do what Jesus would do, it becomes necessary to know what Jesus was. That is, what were his essential characteristics that made him what he was? Assuming he existed–although there are religious scholars and historians who argue against it–was Jesus divine, and, if he was, what made him divine? There are a number of positions that have been posited and defended on this issue. The historical and religious views range from him being a Jewish member of Homo sapiens to being God, Himself. They include that he was both wholly a human mortal and wholly a divine entity,

at the same time. That option is far harder to handle than I want to take on here, so let us go for the two extremes in the range of answers.

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that Jesus was a mortal, finite human being. He would be a man who lived 2,000 years ago, spoke Aramaic, and had no conception of the world in which we now live. If this is true, then it would make WWJD? of little use to anyone who wanted to know the answer to questions never dreamed of 2,000 years ago. Our smart phones, internet, artificial intelligence, and other technology would baffle him even more than it does my and older generations. There would be no thought of inherent entitlements to anything, such as privacy. What would Jesus do? Probably be very puzzled–if not totally lost–by the massive changes that have occurred since his worldview worked. It would probably be better to ask for information of a neighbor with an Internet connection and the ability to tell credible from fantastic data sources.

Jesus as God has the same problem of not providing the guidance that people hoped–and actually may land them with a charge of blasphemy. In this interpretation, Jesus is the literal

child of God, an aspect of God, or God, himself. Any one of these being the case, then asking what Jesus would do is to ask what a god would do in that situation. But that is of little assistance to finite mortals lacking infinite knowledge, goodness, presence, and power found in the divine. We are manifestly unable to understand the situation in the manner an infinite mind with its infinite knowledge can. We cannot raise people from the dead, turn water into wine, and do other miracles that break or rewrite the laws of nature. Thus knowing what Jesus would do doesn’t much help any human being.

More troubling, if we think that we can act as a god would act, then we are in danger of being called out for hubris, if not being delusional. Some hearing us speak in this manner might rightly consider confinement in a place in which we cannot harm ourselves or others might be in good order. And, at worst, we should be wary of a lightning bolt from a clear sky or some other spectacular divine punishment that would cost a considerable amount of money to reproduce in an action movie.

The way to fix this quandary is to resort to the Principle of Charity. Those who were caught up in the movement seemed to be sincere about what they were doing: teens were using it as a tool against peer pressure. If they just did what Jesus did, then they would be better

We are manifestly unable to understand the situation in the manner an infinite mind with its infinite knowledge can.

people doing the right thing and, I assume, enjoy a thriving existence. The thoughtful among them were not attempting to emulate a 2,000-year-old Jewish man or a god. Rather, they were thinking along the lines of What Would Jesus Want Me to Do? (WWJWMD?) Although not as pithy as the shorter version, it is far more accurate to the intended purpose and outcome.

WWJWMD? becomes merely a form of Virtue Ethics with an Ideal Observer. A perfectly virtuous being with complete knowledge of all situations and ability to perfectly use its critical reasoning abilities would know the correct answers to what one should be and how one should act in each contextual circumstance. All that a finite mortal has to do is to behave as that virtuous person wants us to act in that situation and for the same reasons motivating that being. Although we might never fully know why we are obligated to exit and act in this way, whatever Jesus would want us to be and do has to be good and right because it is something deemed to have those statuses by the perfect judge. Given the very positive message provided in the New Testament, then that is likely to work out to being compassionate, eschewing violence, selfishness, and self-righteousness, bettering oneself by becoming more virtuous, loving and caring for one’s neighbor, and otherwise possessing excellences of

character and acting upon it all in a way that reasonable people would agree is an exemplary life. All one would need to add, perhaps, is regular examination of it and the beliefs the person living it holds.

In the history of Homo sapiens, it is unlikely that there was any particular moment in time when there wasn’t conflict and unnecessary pain and suffering caused by plain stupidity. Humans as imperfect beings, after all, can be saints, but they have proven themselves sinners in horrific ways. By critically examining our beliefs, especially those most central to who we are individually and communally, and how we act, as well as our overall life in the social and environmental contexts in which we live, there is a greater hope for We the People to survive the partisanship, tribalism,, and incivility currently being experienced. And hopefully to come out of the trial and to thrive. l

DENNIS COOLEY received his PhD in philosophy from the University of Rochester in 1995. His teaching and research interests include theoretical and applied ethics with a focus on pragmatism, bioethics, business ethics, personhood, and death and dying.

by Karen Hooge Michalka

by Karen Hooge Michalka

Large numbers of Afghan refugees began seeking stable places to land in the fall of 2021. The war in Ukraine has also created a diaspora of people desperate for a safe place to live and raise their children. Many of these refugees are making their way to North Dakota, a state with a proud immigrant past which yet seems ambivalent about its current openness to refugees and immigrants. How do we resolve this ambivalence, and what information do we use to make decisions about how best to allocate our resources, encourage the development of social trust, and create the economic and social conditions for a thriving community?

We live in an information era when innumerous facts and data are available to us at a finger’s touch. This knowledge can be used to establish justification for public policy, personal voting choices, and more, yet it can be difficult to know if the information we are drawing on truly represents our context and whether it is accurate and up to date. A region such as the northern plains often escapes national attention in many important debates and thus nationally representative surveys may not be completely accurate for understanding our setting. Personal anecdotes and experiences can be powerful, memorable, and influential, but they may also be completely inaccurate for understanding more pervasive local trends. To provide robust, well-researched information regarding our state, we need an increase in public scholarship, particularly for the western half of North Dakota, located farther from our research universities.

A problematic aspect of the current (mis)information age is that the glut of information is paired with a lack of clarity and accuracy of particular, sound information.

Thus, we can hear about the unique experiences and opinions of thousands of people within minutes, but we do not have a clear way of knowing how common, widespread, or accurate that information is. One local example of this kind of situation occurred in the fall of 2019 when Burleigh County gained national attention for addressing the question of whether refugee resettlement could continue. Though the commissioners voted 3-2 to allow refugee resettlement to continue, with yearly review, it created an intense discussion over refugees in a largely rural area. A town hall discussion brought over a thousand local residents to voice their concerns over refugees (and immigration more broadly) and their support for our local refugees, as well as speaking more broadly about these issues in the whole of the United States.

What kinds of information were drawn on as people shared their thoughts? One commonly used source of information was nationally representative surveys. These are powerful and important sources of information about the state of our nation, such as trends in public opinion, experience, or the hopes and fears of those who reside in this country. With a careful selection of respondents, nationally representative surveys, such as those run by the Public Religion Research Institute and Pew Research, can be accurate with even a relatively small number of cases. These surveys show that a strong majority of Americans support accepting refugees and believe that immigrants strengthen American society. However, while this information is true at a national level, applying these insights to a particular region or state, such as North Dakota, can lead to inaccurate and unreliable positions. With the need to welcome and integrate Afghan and Ukrainian refugees, among others, inaccurate data about public perception may lead to policies that weaken social trust rather than build it. A robust survey that accurately represents our nation as a whole may not have the analytical strength to zoom in closer.

On the other end of the spectrum, we find personal anecdotes and experiences that shape opinions are often widely shared and influential. A shocking or memorable story might carry more weight than the carefully researched and argued academic study. Repeatedly, in the 2019 county commission town hall, people shared their concerns and hopes regarding continued refugee resettlement, often based on personal experience or anecdote. These personal experiences may be indicative of larger trends, or they may be outliers. Without more context, it is impossible to know.

Where can we get this local-level context? The most reliable sources come from surveys, focus groups, and interviews that are built using the best research methods, conducted by unbiased researchers who are willing to follow the data as they are revealed, and disseminated in an understandable and accessible manner. These data must be current, relevant, accurate, and should come from trusted and trustworthy researchers, with any underlying purposes made clear.

It may be a comfortable assumption on the part of many people throughout the United States that research is primarily done for the purpose of scholars speaking to one another, or that it is commissioned by interested parties who want the aura of scientific rigor to promote their preconceived positions. And while it may be true in some cases, most scholars want their work to be accurate and to be useful to the local populations and communities in which they live. In many cases, the theoretical insights and data-driven methodology of sociology and other academic disciplines have failed to connect with a broader public. This situation, along with growing populism and distrust of expertise, means that the future of public scholarship faces unique challenges. It cannot stay in the ivory tower but must make creative connections with people, showing the usefulness of its approach. It is the duty of researchers to work to build community trust, and it is the duty of a civic-minded population

Inaccurate data about public perception may lead to policies that weaken social trust rather than build it.

to thoughtfully weigh this data as community members form opinions and live their lives.

Several current projects are looking at this potential shift, including one in which I am involved. This project, supported through Bismarck Global Neighbors and the University of Mary, is a needs-assessment survey of refugees, immigrants, and other arrivals from U.S. protectorates and territories. It represents one half of the full picture of understanding newcomers and their communities of reception. The goal is to publish a report, shared with the public, that can be used to develop policy proposals for the local, regional, and, potentially, state level as well as to promote an understanding of and appreciation for solidarity amid diversity. The project, an urgent need here in North Dakota, where generational memories of settler immigration still exist but where our local populace suffers ambivalence over current immigrant populations. If we lack clear, evidence-driven information about diversity and immigration, debates will only be able to rely on data that are too broad or too personal.

Good scholarship, such as that by Alejandro Portes and Ruben Rumbaut, has shown that immigrants bring many social and economic benefits to a region, but the research often overlooks the cultural isolation and distrust that can develop as a result. Building a community that values and welcomes refugees and immigrants and sees potential partners rather than competitors requires that we look seriously and soberly at real challenges that can develop. This attentive, open-minded approach requires good local studies and data.

Over the next months and years, we need research projects that bring world-class techniques when considering our local situations. We need to assess the needs, challenges, and opportunities that refugees, immigrants, and other newcomers face. We need to dive into the beliefs, histories, and social arrangements that can

contribute to the development of trust between old-timers and new arrivals. We need to uncover the social determinants of health that impact our physical, mental, and social well-being. We need this information to be shared widely–not just within academic circles, but with nonprofits, government agencies, and everyday residents, and we need an interested public.

A lack of good information can be the innocent result of the gap between robust, nationally representative studies and personal, local anecdotes, but we cannot allow ourselves to stay there. We need an increase in public scholarship, one that studies both our larger population centers and our rural countryside. Well-researched public scholarship is essential for the health of local communities, for our civic life, public policy, neighborly trust, and thriving cities and towns. l

KAREN HOOGE MICHALKA, PH.D., is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Mary. Her curiosity and interest in the lives of those around her developed after she moved from her hometown of Munich, ND, to college outside of Chicago, two years spent in Mexico, and finally graduate school at the University of Mary. Her research and writing focuses on immigrants and communities of reception, especially as it relates to issues of cultural exchange, religious impulses, and community trust.

by George Frein

by George Frein

Peeking through the curtains backstage, in the library’s multipurpose room, I could see it was a good crowd. Almost 200 people had come for tonight’s humanities program. I listened as the librarian made some announcements: the fiction book club would meet on Monday, fines for late returns would be waived until the end of the month, another Chautauqua program was scheduled for August. Then she introduced me: he was born in 1819, went to sea for the first time as a boy, published five sea books before writing his famous classic. Finally, came her cue for me to step out: “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Herman Melville.”

Pulling my coat collar up around my ears and with a little shiver, I begin: “Whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul, whenever I find myself joining every funeral procession I come upon, I count it high time to get to sea and let the ocean work its magic in my soul.” I explain, “I write of mariners, renegades, and castaways, and to them I ascribe the highest dignity. Oh, not the dignity of kings and robes, but that august dignity that has no robed investiture. Thou shalt see it shining in the arm that wields a pick and drives a pike - a democratic dignity.”

My talk lasts just 40 minutes. Then the audience asks Mr. Melville questions for 20 minutes more. After that, the librarian introduces me again, this time as a humanities scholar with a long interest in Melville, and I take more questions.

Audiences ask Mr. Melville about Ahab, the tyrannical captain of the Pequod. I say that he suffered from monomania. He thought of one thing only, “wreaking vengeance” on the white whale that sheared off his leg. Asked why the crew went along with the captain, I tell how he infected them with his madness by nailing a gold Spanish doubloon to the mainmast, promising it to the sailor who

first sighted the white whale and sang out, “Thar she blows.” I tell how only the first mate, Mr. Starbuck, resisted: “Vengeance on a dumb brute that smote thee out of blind instinct, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous.” I point out that Ahab’s answer reveals his character: “Mr. Starbuck, talk not to me of blasphemy man, [making a fist and clenching my teeth] I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.”

Out of character, I am asked: “George, where did Melville get his story about the white whale?” “What were his other sea books about?” “Why was MobyDick so long?” “What was Melville’s overall purpose?” “What does the whale symbolize?” “What makes Moby-Dick an American classic?” I answer the questions, but I also use this time to promote the humanities. I ask the audience questions and try to get a discussion going. I suggest how Moby-Dick raises philosophical and theological questions. Finally, I recommend other books by Melville and suggest a new book or two about his work.

I know how outrageous it is for me to go on stage and pretend to be Herman Melville. I know this even though I’ve read everything he wrote–novels, short stories, essays, poetry, letters. But, all that reading only made me want more. I wasn’t satisfied with his finished books. I wanted to get into his thinking process. So I spent months reading the books Melville bought and read himself. I found them in the rare books collection at Harvard’s Houghton Library. There, I held the very books Melville himself once held in his

I held the very books Melville himself once held in his hands. I read the notes Melville scribbled in the margins.

hands. I read the notes Melville scribbled in the margins. I soon discovered that he was a critical-minded reader. The margins of his books are crammed full of his arguments with the authors: Emerson, Hawthorne, Shakespeare, the authors of the Bible–God included. I was forced to read Melville’s marginalia slowly because his penmanship was almost illegible. But the result was thrilling. I could almost hear the man talking to himself as he read. I had gotten into his head. I listened to him think. Finally, with so much Melville in my head and ears, I turned to read the vast body of Melville criticism: history, biography, literary analysis.

Still, pretending to be Melville is outrageous, I know, but it proved to be rewarding. I got a unique chance to use what I had learned. Public audiences clearly enjoyed it. They played along with the fiction. They asked Mr. Melville probing questions. They asked good questions about Melville studies. They talked with me as if I were his latter-day personal friend.

show. My first performance was a practice program at a library, but, after that, my Melville traveled all across the Great Plains states for three summer seasons with six other writers from the American Renaissance. We pitched a big tent in a town park, filled it with 300 chairs, a good sound system, and a small stage. We invited townspeople to come hear from some of America’s most famous writers.

Now, thirty years later, I still hear each of those writers talking to audiences in the 1990s: listening recently to a two-faced politician, I hear Hawthorne telling the story of The Scarlet Letter and observing, “No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be true.”

Reading poetry when I should be working, I hear Walt Whitman: “We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. So medicine, law, business, engineering . . . these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love . . . these are what we stay alive for.”

The goal of the humanities was served: there was critical thinking about human nature, culture, and society. My Melville was as authentic as my scholarship could make him. Audiences seemed to learn something about themselves from their encounter with Melville. I sometimes think, after a particularly good show, that what we learned tonight about ourselves could not have been learned from anyone but Melville, telling stories and thinking out loud.

At the behest of the Humanities Council of North Dakota and for the Great Plains Chautauqua, I developed eleven different Melville programs in addition to the Moby-Dick

When a patriotic orator talks uncritically on July 4th about American exceptionalism, I hear Frederick Douglass speak: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”

After reading a news story about women in public office, I hear Louisa May Alcott observe, “When women are the advisers, the lords of creation don’t take the advice till they have persuaded themselves that it is just what they intended to do. Then they act upon it, and, if it succeeds, they give the weaker vessel half the credit of it. If it fails, they generously give her the whole.”

Learning that a woman has just shattered another glass ceiling, I hear Margaret Fuller, the first woman to become a foreign correspondent: “We would have every arbitrary

The goal of humanities was served: there was critical thinking about human nature, culture, and society.

barrier thrown down. We would have every path laid open to women as freely as to men. If you ask me what offices they may fill, I reply–any. I do not care what case you put; let them be sea captains, if you will.”

When a friend tells me he is thinking about living off the grid, I hear Henry David Thoreau say, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Watching a debate on TV about immigration, I hear Melville say: “Let us waive that agitated national topic, as to whether such multitudes of foreign poor should be landed on our American shores; let us waive it, with one only thought, that if they can get here, they have God’s right to come; though they bring all Ireland and her miseries with them.” And I hear the reason he gives for this: “America is not so much a nation as a world.”

As the above recollections suggest, what is unique about the humanities Chautauqua, and critical to its success, is the spoken word. When a Chautauqua program is successful, audiences remember what they heard, the way college students remember what they have read. The humanities, in school and out of school, work with texts: texts that are held in common, talked about together, analyzed, debated, compared with other texts, and tested for authenticity. All that work is easy for college humanities classes. Everybody gets the same reading assignment.

But no sizable, general, public audience can be assigned a book to read before attending most humanities programs. “Read Moby-Dick for next Friday’s discussion at the library” would guarantee a small gathering. “Come meet Herman Melville and hear him tell his story about the white whale” is an intriguing invitation and one that brings out a large, diverse crowd. A few will have read the book, many more will have started it, still

more think they should have read it, and some more will come along with a friend, “Why not? I don’t have anything doing. Tell me again, who is Herman Melville?” It’s a nice-sized crowd. It is also a democratic crowd. No matter their level of schooling, everybody hears the same firstperson talk. Everybody knows what everyone else has heard. Everybody can discuss and debate their common experience. It is as easy to go along with tonight’s fiction as it is to suspend disbelief while reading a novel or watching a movie.

If the audience is to have a rewarding humanities experience, however, there must be a good oral text for questioning. It must be constructed by a scholar who knows a character intimately and can make the fiction believable. The first-person monologue must be historically accurate. It must also be a talk that makes the audience think about things important to the humanities disciplines. Audience members should be prompted by the monologue to ask the speaker about philosophical and theological issues, literary matters, historical developments, ethical judgements, anything having to do with human nature, culture, and society.

The monologue should also bring listeners into the world and thinking of the character on stage and do so in such a way that they will readily ask questions from within the character’s time and place. In addition, they should have questions that compare and contrast the character’s time with their own.

Humanities Chautauqua asks scholars for work that is authentic and intellectually stimulating. But it asks more than that. It asks them to be actors, not professional actors, but fair amateurs. If you put on a costume, get up on stage, and play the part of a historical character, you are an actor–at least, that is how the audience is going to see you. So there must be some acting. The monologue must have a little drama: no reading or working from notes, verbs in the present tense, perhaps some dialogue with an imagined other person. The amount of acting required is not much, just

enough to make it believable. Too much drama and the humanities are overshadowed by the art; too little and the monologue becomes a lecture.

Additionally, the Chautauqua scholar must be a storyteller. The monologue is not a professorial lecture. The scholar should tell stories in order to engage listeners as only stories can. Abstractions can leave general audiences unmoved. Stories about concrete times and places and people capture listeners’ attention and hold it from the beginning, through the middle, to the end.

When the Humanities Chautauqua movement began in the 1980s it mostly employed college professors. Before long, however, it reached out to actors and storytellers and selected those who could do the work of humanities scholars. It required actors to go beyond playing a part in someone else’s script and demanded that they do their own research and compose their own texts. In addition, they had to be prepared to answer audience questions spontaneously and with historical accuracy. Storytellers were required to have the same research skills. Actors and storytellers were asked to think of their work as thought-provoking presentations, designed to generate questions and encourage discussions critical to the humanities. Scholars who now do Chautauqua combine research skills and performance skills. They have all been required to find skills they didn’t know they had.

It is not just the performers who learn something. Humanities Councils, too, have learned something, something central to the humanities. Working with actors and storytellers–having them do their work on a stage, for an adult, out-of-school audience–councils have discovered that humanities scholarship can be fun. Chautauqua has taught the humanities something about itself: it can be as enjoyable as it is serious.

Now, more than ever, the humanities need to keep Chautauqua programs alive and well. The reason is simple: Chautauqua helps make

the humanities one of the most enjoyable forms of adult learning.