OAKLAND COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION

1760 S. Telegraph Road, Suite 100

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48302-0181

(248) 334-3400 • FAX (248) 334-7757 www.ocba.org

PRESIDENT

Sarah E. Kuchon

PRESIDENT-ELECT

Aaron V. Burrell

VICE PRESIDENT

Kari L. Melkonian

TREASURER

Victoria B. King

SECRETARY

Syeda F. Davidson

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Jennifer Quick

LACHES EDITORIAL BOARD

Victoria B. King

Syeda F. Davidson

Coryelle E. Christie

DIRECTORS

Julie L. Kosovec

Emily E. Long

Jennifer L. Lord

Moheeb H. Murray

Kimberley Ann Ward

Layne A. Sakwa

Silvia A. Mansoor

Stephen T. McKenney

James A. Martone

Jennifer J. Henderson

DELEGATE

James W. Low

Lanita L. Carter

Thamara E. Sordo-Vieira

Xavier J. Donajkowski

THE MISSION OF THE OAKLAND COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION IS TO SERVE THE PROFESSIONAL NEEDS OF OUR MEMBERS, IMPROVE THE JUSTICE SYSTEM AND ENSURE THE DELIVERY OF QUALITY LEGAL SERVICES TO THE PUBLIC.

Articles and letters that appear in LACHES do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Oakland County Bar Association, and their publication does not constitute an endorsement of views that may be expressed. Readers are invited to address their own comments and opinions to:

LACHES | Oakland County Bar Association

1760 S. Telegraph Rd., Ste. 100 Bloomfield Hills, MI 48302-0181

Publicationandeditingareatthediscretionoftheeditor.

LACHES

Oakland County Bar Association, 1760 S. Telegraph, Ste. 100, Bloomfield Hills, MI 48302-0181.

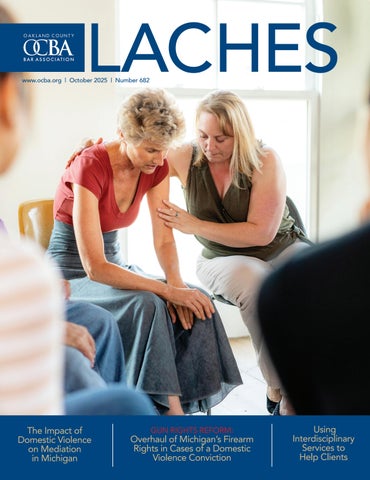

Gun Rights Reform: Overhaul of Michigan’s Firearm Rights and Restoration Following a Misdemeanor Involving Domestic Violence Conviction

The enactment of Public Act 201 of 2023 imposed sweeping changes to the gun rights of many Michiganders.

The Impact of Domestic Violence on Mediation in Michigan: Challenges and Attorney Best Practices

Though Michigan courts promote mediation, the presence of domestic violence introduces significant complications.

Using Interdisciplinary Services to Help Clients

Social service advocates can help clients fulfill their nonlegal needs so attorneys can focus on their legal cases.

Shame. We have all felt it. That feeling that something is inherently wrong with us. That we are bad. It is like a slow-burning fire that simmers, smoldering beneath the surface. It can distort our inner world, keeping us small, guarded, and disconnected. Over time, it seeps into everything — how we see ourselves, how we show up in relationships, and what we believe we deserve. Shame feeds on silence, secrecy, and fear. However, when we name it, talk about it, and hold it with compassion, shame begins to lose its power.

“Rise from the ashes” is more than a poetic idiom. It is a powerful metaphor for transformation, rooted in the myth of the phoenix that is reborn from fire. In life, many of us carry shame like heaping coals of fire on our heads, burning quietly but relentlessly wearing us down. Shame can stem from a range of experiences, some resulting from our choices, others inflicted upon us through trauma, rejection, or judgment. Regardless of its origin, shame isolates and disconnects. But instead of letting shame define us, we can flip the script and use those heaping coals of fire as tools to refine us, to help us grow, transform, and rise from the ashes.

Brené Brown, a research professor and renowned author, defines shame as “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love, belonging, and connection.” Unlike guilt, which is tied to behavior — i.e., “I did something bad” — shame attacks identity — i.e., “I am bad.”

Shame is an emotion that most of us feel. It thrives in secrecy and silence. It is especially pervasive for those who have experienced trauma. Whether it’s childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, addiction, or simply growing up in an environment where emotions were not safe to express, shame often becomes a hidden thread that influences our decisions, relationships, and sense of self-worth. Blame and judgment can trigger shame because they send the message that a person is bad, broken, or not enough.

By Sarah E. Kuchon

When someone is blamed, they are often made to feel responsible not just for what they did, but for who they are. Judgment piles on by declaring that they are somehow defective, immoral, or unworthy.

Because shame thrives in secrecy and silence, we often believe we are the only ones carrying quiet pain, unsure whether anyone would understand if they knew our truth. We feel disconnected and alone. We assume that someone who seems confident and composed has had an easy road. These assumptions fuel our separateness, keeping us stuck in the shadows of our pain. But the reality is that behind even the most composed

exteriors are often stories of struggle, resilience, and survival. I know this because I know plenty of people with a polished cover whose stories are full of challenges and struggles. My own story includes domestic violence and a childhood full of difficulties. For a long time, I stayed silent, afraid that if others knew the truth, they would see me differently. Over time, I learned that what once felt like it might undo me instead revealed my strength. In choosing to speak, I rose, not despite coals of fire, but because of them. By being open about my experiences, I reclaimed my worthiness and stopped hiding in the shadows. This is where shame ends and vulnerability and authenticity begin.

One of the most liberating truths is this: Our stories shape us but do not define us. What happened to us is part of our journey but is not the whole of who we are.

In narrative therapy, a core principle is that we are not the problem. e problem is the problem. is therapeutic approach invites us to externalize our pain, to put space between ourselves and the stories we carry, and to reclaim authorship of our lives. is means learning to hold our past with compassion rather than judgment. It means revisiting painful memories not to relive them but to reframe them. To say: is happened, but it does not define me. I am not what was done to me.

Shame resilience is about vulnerability and authenticity. It is the ability to identify shame, understand it, and respond in ways that protect our sense of self-worth and strengthen connection with others. It is a practice that requires intention, self-compassion, and community. It is a daily decision to accept who we are and to believe we are worthy.

According to Brené Brown’s research, building shame resilience involves four key

elements. We begin by recognizing how shame shows up for us and understanding its triggers. By recognizing shame, we can begin to create space between the feeling and our identity. We must also practice critical awareness. is means understanding why shame exists within us, how it works, and its impacts. is means questioning messages we download and asking where these messages come from. We then need a space to speak our truth. is means finding safe, supportive people who meet us with empathy and hold space for our stories without judgment. is does not mean oversharing. Rather, it means choosing to be honest with ourselves and others. It means naming shame and reclaiming our sense of self, not as good or bad, but as inherently worthy, whole, and human, flawed and growing, yet still deserving of love, belonging, and connection.

We all have wounds we carry. Some are visible; many are not. While our experiences may differ, the emotions we feel are the same and deeply human. One of my favorite quotes is attributed to the French philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin:

“We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.”

Let that sink in. When we remember that our feelings are a human experience and not the essence of who we are, we can hold our pain with a little more grace. We can see our survival not as weakness but as strength and offer that same compassion to others.

For too long, shame has kept survivors silent. It has convinced us that our value lies in perfection, performance, or our ability to hide the parts of ourselves we fear will not be accepted. But the truth is, our power lies in our willingness to be seen, vulnerable, and authentic.

If you take nothing else from this article, let it be this: You are not defined by what happened to you. You are not broken. You are not bad. You are not alone. Shame is part of the human experience, but it is just an emotion. It is not who you are. Shame resilience is how we rise from the ashes, claiming our story and remembering: We are spiritual beings, beautifully and imperfectly having a human experience. is perspective allows us to hold compassion for ourselves, to see our wounds as part of our becoming, and to rise from the ashes.

Sarah E. Kuchon is the president of the Oakland County Bar Association.

By Jennifer Quick

This past June, the Oakland County Bar Association board of directors adopted a forward-looking strategic plan designed to sharpen its focus on member services, diversity, professional development, and long-term organizational sustainability. Built on months of comprehensive research and member engagement, the plan charts a three-year road map to deepen the OCBA’s value and relevance within the evolving legal landscape.

Following a data-informed and inclusive planning process launched in early 2025, the strategic plan serves as a living document to guide the OCBA’s decisions, programming, and service delivery through June 2028.

I felt it was important to share this information with you, our members, because the strategic plan is designed with you in mind — it’s about creating more opportunities, support, and value for your membership. Whether it’s through expanded business development opportunities, tailored professional development, or more inclusive and responsive programming, the plan outlines concrete ways the OCBA will better meet your needs. By understanding what’s ahead, you can take full advantage of new initiatives and help shape the direction of a bar association that works for you.

At the heart of the plan is a commitment to building a more connected and inclusive member experience. The OCBA has recognized the need to modernize how it welcomes and supports members — especially early-career attorneys, solo practitioners, and underrepresented groups.

A new onboarding and retention framework aims to ensure that all new members receive structured support within the first few months of joining. This includes targeted mentorship and personal follow-ups by both staff and committee members. The goal: to raise first-year retention rates from the current 57% to at least 70% by mid-2026.

Our research unveiled that too many members are unaware of the full benefits available

to them. This initiative is about creating a more personalized and lasting connection with our members from day one.

In addition, the OCBA will launch a reengagement campaign to reach nearly 1,000 lapsed members. The campaign aims to reinstate at least 150 memberships and foster participation in follow-up programming.

To ensure the OCBA’s long-term vitality, the strategic plan puts a strong emphasis on cultivating the next generation of attorneys. Recognizing shifts in the profession — including declining law school enrollment and early retirements — the OCBA will roll out mentorship, leadership, and career development programs tailored for attorneys with zero to 10 years of experience.

Key goals include:

• A revamped mentorship program with at least 50 active mentor-mentee pairs by June 2026.

• A 15% increase in early-career attorney membership by 2027.

• A structured engagement track for new lawyers, featuring at least three events annually and opportunities for five new lawyers to take on OCBA leadership roles.

Current offerings like the Inns of Court and Pro Bono Mentor Match will be enhanced, while new initiatives will focus on law practice management, client development, and career longevity.

Beyond new-lawyer support, the plan addresses membership engagement at all stages. With a current membership of just over 2,400, the OCBA aims to grow its ranks by 10% by

mid-2028 through targeted outreach and revised membership packages.

A major part of this effort involves better demonstrating the value of membership. That includes refining postevent follow-ups and participation tracking to increase repeat attendance by 15% annually and collecting feedback to continually improve programming.

Additionally, the OCBA plans to raise the retention rate of members in their first five years from 73.65% to 80% by June 2027. This will be accomplished through improved onboarding, peer support, and better communication of member benefits.

The OCBA’s events — long a cornerstone of member engagement — are also getting a strategic refresh. By 2026, at least four flagship events will be reimagined to better reflect the association’s diverse membership and increase attendance by at least 15%. These include the New Lawyers vs. The Board Challenge, the Golf Outing, Meet the Judges, and the popular Bench/Bar Conferences.

New programming will be launched to engage underrepresented groups such as solo practitioners, law students, and transactional attorneys. Each initiative is expected to draw at least 10 new unique participants.

Behind the scenes, the OCBA will restructure its event-related committees to ensure alignment with the organization’s mission and member needs. Each committee will have a clearly defined purpose and annual deliverables.

The strategic plan also affirms the OCBA’s mission: to serve the professional needs of its members, improve the justice system, and ensure access to quality legal services. The vision includes fostering professional growth, promoting diversity and civility, and educating the public about the law.

With a robust financial position — includ-

ing a reserve equal to one year of operating expenses — and strong brand recognition, the OCBA is well positioned to lead.

An environmental scan conducted during the planning process highlighted both challenges and opportunities. While generational turnover, the rise of virtual platforms, and economic pressures present risks, they also offer avenues for innovation and growth.

e OCBA’s board of directors believes these conditions make the strategic plan not just timely but essential. e landscape of the legal profession is changing, and we must evolve with it to stay relevant. While developing the plan, the board made sure to honor the OCBA’s legacy while embracing a future that is more inclusive, more responsive, and more member-driven.

e plan begins with a 90-day implementation road map with clearly defined roles and moves forward with quarterly check-ins to monitor progress. It emphasizes that this is not a static document but a living strategy — adaptable to emerging needs and informed by continuous feedback.

Each of the four strategic priorities — building inclusion, supporting early-career lawyers, sustaining engagement, and designing intentional events — comes with success metrics, baselines, and target dates.

rough 2028, the OCBA will use these benchmarks to evaluate progress and ensure accountability, making course corrections as necessary.

To ensure the strategic plan reflects the diverse perspectives of our membership, the board of directors invited OCBA staff and leaders from all 29 committees to participate actively in the planning process, and many of them accepted.

eir thoughtful contributions — combined with insights gathered through extensive data collection — were instrumental in shaping a more inclusive, member-centered plan. I want to extend my sincere thanks to everyone who took part in this important effort. Your voices helped lay the foundation for the OCBA’s future.

As it looks ahead, the OCBA is doubling down on its role as a central hub for the Oakland

County legal community. e new strategic plan lays the groundwork for expanded benefits, smarter engagement, and a broader sense of belonging.

For members, that means more support, more opportunities, and more reasons to stay connected.

Jennifer Quick is the executive director of the Oakland County Bar Association.

If you would like more information about the Oakland County Bar Association’s strategic

and how you can get more involved, please reach out to me at jquick@ocba.org or (248) 334-3400.

Please Note: Dates listed below were sent to the publisher on July 31, 2025. It is possible that some of the events listed below have since been altered. Please check ocba.org/events for the most up-to-date schedule of events.

Join colleagues and members of the OCBA and local affinity bars for the biennial Taste of Diversity cocktail reception — a celebration of the rich diversity and multiculturalism within our legal community. Enjoy an evening of festive camaraderie, delicious hors d’oeuvres, and meaningful recognition.

The event will also feature the presentation of the Leon Hubbard Community Service Award and the Michael K. Lee Memorial Award, honoring individuals who have made outstanding contributions to advancing diversity in the legal profession. Don’t miss this inspiring and lively evening — register today at ocba.org/2025diversity

Our bench/bar brown-bag luncheon series continues virtually via Zoom and will feature Judge Kathleen M. McCarthy and Judge Edward Ewell Jr. from the Civil Division of the Third Judicial Circuit Court. They will share tips and preferred protocols for practicing in Wayne County. Bring your questions and join us for an informal discussion of legal topics and practice issues. Space is limited, so register today at ocba.org/events

Join us for a special fall Bar Night Out Mixer — an evening of connection, community, and celebration!

In partnership with the New Lawyers Committee’s annual Novemberfest, this lively event brings OCBA members together for a festive night featuring appetizers, a cash bar, and great company. Whether you’re reconnecting with colleagues or meeting new faces in the legal community, it’s the perfect way to unwind and expand your professional network. Don’t miss out — visit ocba.org/novemberfest for details and registration!

•

•

•

non-compete and non-solicitation

•

Drafting employment contracts

Separation agreement reviews and severance negotiations

• HR counseling, defending against government investigations

Expand Your Knowledge with These Great Seminars!

9 Update on the State of Juvenile Law 2025 (11:30 a.m. – 1 p.m.)

A seminar for criminal defense appointed counsel

Presenter: H. Elliot Parnes, Esq., H. Elliot Parnes, PLLC

This Zoom seminar will provide an annual review of developments in juvenile law, including new legislation, court rules, and case law from the past year. A Q&A session will follow the presentation. Worth 1.5 hours of criminal and juvenile training credit for appointed counsel

14 Domestic Violence Cases — Confrontation Clause (Noon – 1 p.m.)

A seminar for criminal defense appointed counsel

Presenters: Tanya A. Grillo, Esq., Grillo Law, PLLC, and Jennifer (Jen) C. Smith, Esq., Brimstone Law, PLLC

Join us during National Domestic Violence Awareness Month! This virtual seminar offers a concise and informative overview of the confrontation clause. In the context of domestic violence cases in Michigan, the confrontation clause of the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution plays a crucial role in ensuring a defendant’s right to confront their accuser in a criminal trial. This right, established in Crawford v. Washington, limits the admissibility of out-of-court “testimonial” statements against a defendant, meaning such statements are generally inadmissible unless the declarant is unavailable to testify and the defendant had a prior opportunity for cross-examination.

Worth 1 hour of criminal and juvenile training credit for appointed counsel

21 The Life Cycle of a Law Firm: Launch, Lead, and Leave a Legacy (Noon – 1 p.m.)

A seminar from the Professional Development Committee

Presenters: Jessica Fleetham, Esq., Evia Law PLC; Joseph Doerr, Esq., Doerr MacWilliams Howard PLLC; and Gerald E. McGlynn III, Esq., Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC

Moderator: Steven Susser, Esq., Evia Law PLC

This Zoom seminar will provide an overview of the life cycle of owning and managing a law firm. Your legal career will go through many different transitions — come get some tips and advice on managing your practice, from launching, maintaining, and growing a law firm to succession planning and exit strategies. You don’t want to miss this!

TBA Litigation-Proofing Your Deal: M&A Disputes, Contract Pitfalls, and Pro Strategies for Business Lawyers (TBA)

A seminar from the Professional Development Committee

Presenters: TBA Avoiding costly legal battles starts with smarter deal making. Join leading experts for a high-impact seminar designed for business lawyers and deal professionals, where we’ll unpack hard-earned lessons from real M&A disputes and explore how to structure deals that withstand scrutiny. Learn how to identify and resolve common sticking points in contract negotiation, draft with litigation in mind, and build agreements that reduce risk and enhance enforceability. Whether you’re negotiating your next merger or refining a standard contract, this session will arm you with the insights and tactics to protect your clients — and your deals — from future disputes. Don’t just close deals — future-proof them. Register now.

20 Update on the State of Criminal Law 2025 — Part Two (11:30 a.m. – 1 p.m.)

A seminar for criminal defense appointed counsel

Presenter: Alona Sharon, Esq., Alona Sharon PC

This Zoom seminar will provide an overview of the most recent published Michigan Court of Appeals cases with a focus on sentencing decisions. Join us for an in-depth discussion of hot topics, emerging issues, and practice pointers in criminal law. Worth 1.5 hours of criminal and juvenile training credit for appointed counsel

By Robert M. Goldman

With a sharp rise in the volume of domestic violence cases, and with so many notable cases grasping the public’s attention, many stakeholders and community members sought to strengthen the governance restricting gun rights following a criminal conviction. By amending key provisions of Michigan’s penal code, the state of Michigan sought to expand the class of individuals prohibited from possessing a firearm or ammunition following a criminal conviction — namely, to those convicted of misdemeanors involving domestic violence.

In response to the growing concern regarding the rise in domestic violence cases, the state of Michigan imposed a significant reform to the state’s regulation of firearms in connection with a misdemeanor conviction of domestic violence by enacting Public Act 201 of 2023, which took effect on February 13, 2024. In enacting this set of bills, the state Legislature overhauled key provisions of MCL 750.224f, the penal code statute prohibiting the possession, use, transportation, and distribution of a firearm or ammunition following a felony conviction. Proponents of the bill argue the reforms bring Michigan into closer alignment with federal regulations following a conviction for a misdemeanor involving domestic violence.

MCL 750.224f, commonly known as Michigan’s “felon in possession” statute, formerly addressed prohibitions and restoration following a felony conviction. e statute broke felony convictions into two categories: specified or unspecified offenses. For a felony to be considered “specified” for purposes of MCL 750.224f, one of the following conditions had to be met: e offenses convicted of had circumstances involving the use or attempted use of physical force; an element of the felony involved a controlled substance; an element involved unlawful possession or distribution of a firearm or use of an explosive; or, lastly, the felony was burglary or breaking and entering of an occupied dwelling or arson. An “unspecified” felony covered a felony conviction where the maximum term of imprisonment exceeded two years.

Following the overhaul of MCL 750.224f, Michigan reclassified the statute and enhanced the definitions of two key terms: “felon in possession” and “misdemeanor involving domestic violence.” With respect to “felon in possession,” the overhaul expanded the class of individuals considered to be “prohibited persons” by now including eligible misdemeanors within the scope of restriction. Where the former version considered an offense with a term of imprisonment of two or more years to be a felony, the current landscape now provides the definition of a felony to include a term of imprisonment exceeding one year, or an attempt to violate such law. e inclusion of the term “misdemeanor involving domestic violence” enhanced the scope of MCL 750.224f to now include misdemeanor offenses. Misdemeanors, which formerly were not considered under MCL 750.224f, now include offenses such as domestic assault, MCL 750.81(2); aggravated assault, MCL 750.81a(2); breaking and entering or entering without breaking of buildings, tents, boats, or railroad cars, MCL 750.115(2); vulnerable adult abuse in the fourth degree, MCL 750.145n(4); malicious

destruction of personal property, MCL 377a(1) (d) or (f); malicious destruction of property of house, barn, or building of another, MCL 750.380(5) or (7); stalking, MCL 750.411h(2)(c); and malicious use of telecommunications service, MCL 750.540e(1)(h). Moreover, an ordinance, a law of another state, or a law of the United States that substantially corresponds to a violation listed in MCL 750.224f(10)(c) or is specifically designated as domestic violence by the outside jurisdiction is included within the definition of a misdemeanor involving domestic violence.

e addition of these offenses, and the offense of domestic assault contrary to MCL 750.81, brings large swaths of individuals within the scope of these restrictions who previously did not see deprivation of gun rights for such convictions. As a result, defense counsel must advise clients of the newly enacted additional sanctions that can be imposed following a conviction for a misdemeanor involving domestic violence.

Pursuant to MCL 750.224f(5), upon conviction of a misdemeanor involving domestic violence, the prohibitions imposed on a prohibited person are in effect until the expiration of eight years and the following conditions are met: (a) e person has paid all fines imposed for the violation; (b) the person has served all terms of imprisonment imposed for the violation; and (c) the person has successfully completed all conditions of probation imposed for the violation.

e enactment of Public Act 201 of 2023 did not alter the process of restoring firearm or ammunition rights for a felony conviction. A person convicted of an unspecified felony, who has paid all fines, served all terms of imprisonment, and successfully completed all conditions of probation or parole, automatically has their firearm rights restored after the expiration of three years. An individual who has satisfied such conditions does not need to file a petition or seek judicial relief. But in circumstances concerning a “specified felony,” the law requires the satisfaction of the same conditions and, after the expiration of five years, requires the individual to petition the circuit court for the county in which they reside to have their gun rights restored pursuant to MCL 28.424.

e enactment of Public Act 201 of 2023 did not impose a requirement to petition the circuit court for relief as statute requires of a “specified felony.” Following a conviction for a misdemeanor involving domestic violence, satisfaction of and compliance with fines, jail time, and/or probation or parole, and the expiration of eight years following the conviction, can result in a person’s firearm rights being restored without further action.

A prohibited person found to have possessed, used, or transported a firearm in violation of MCL 750.224f, upon conviction, is guilty of

a felony punishable by imprisonment for not more than five years or a fine of not more than $5,000.00, or both. Additionally, a prohibited person found to have possessed, used, or transported ammunition in violation of MCL 750.224f, upon conviction, is guilty of a felony punishable by imprisonment for not more than five years or a fine of not more than $5,000.00, or both.

Perhaps most significantly, under the statutory reform, the restrictions and sanctions under MCL 750.224f apply retroactively. However, the restrictions and/or sanctions do not apply to a conviction that has been expunged or set aside, or for which the person has been granted a pardon, unless the expungement order or pardon expressly provides that the individual should not possess a firearm or ammunition.

An individual convicted of a misdemeanor involving domestic violence or a felony should be advised that the conviction and restrictions imposed under MCL 750.224f can prevent a person from obtaining or renewing a concealed pistol license (CPL). Pursuant to MCL 28.425b(7)(e), an individual prohibited under MCL 750.224f cannot be granted a CPL upon application. Moreover, an individual convicted of a misdemeanor involving domestic violence must wait eight years from their conviction, without any convictions during said wait period, before they may apply for a CPL.

e enactment of Public Act 201 of 2023 imposed sweeping changes to the gun rights of scores of Michiganders. rough the expansion of the class of prohibited persons and retroactive imposition of an eight-year prohibition of firearm rights, the environment in which prosecutors and defense counsel operate has shifted mightily. Now, defense counsel must be aware and advise their clients that in cases of misdemeanors involving domestic violence, the sanctions to be imposed have expanded considerably into unprecedented territory, and clients must understand the gun rights they lose in light of the statutory reform.

Robert M. Goldman is a solo practitioner and founder of the Law O ces of Robert Goldman, PLLC, in Bloomeld Hills. His practice focuses on criminal/tra c defense, driver’s license restoration, and expungements. Goldman is an active member of the OCBA’s New Lawyers Committee and Criminal Law Committee and the State Bar of Michigan.

By Channelle Kizy-White

Mediation has long been a preferred method of dispute resolution in family law cases including divorce and child custody and support matters, offering parties an opportunity to settle their differences outside the courtroom. In Michigan, mediation is often encouraged or mandated in family law disputes as a way to reduce conflict, save time, and foster cooperative solutions. Mediation typically serves as a cost-effective alternative to prolonged litigation. However, the presence of domestic violence complicates this process significantly. Domestic violence, defined broadly as a pattern of controlling, coercive, or abusive behavior used to assert power over a partner, can distort the dynamics of mediation and lead to inequitable outcomes. Attorneys must navigate these complexities carefully to ensure the safety and rights of their clients. This article examines how domestic violence impacts mediation, the legal and ethical obligations of attorneys, and practical strategies for supporting clients effectively.

Michigan courts promote mediation as a primary tool for dispute resolution. The Michigan Court Rules (MCR 3.216) authorize judges to refer family law cases to mediation, either upon motion or sua sponte. Mediation aims to facilitate communication, reduce court caseloads, and empower parties to reach mutually acceptable outcomes. In theory, this collaborative model serves the best interests of children and promotes amicable longterm co-parenting.

However, mediation depends on a foundational assumption of parity — emotional, psychological, and informational — which does not hold when one party has experienced abuse or coercion.

Domestic violence encompasses a range of coercive behaviors, including physical violence, emotional abuse, financial control, intimidation, and isolation. In Michigan, the Domestic and Sexual Violence Prevention and Treatment Board defines domestic violence as “a pattern of learned behavior in which one person uses physical, sexual, and emotional abuse to control another person.” Importantly, the effects of domestic violence are not limited to visible injuries. Long-term trauma, fear, and manipulation can profoundly alter the victim’s ability to engage in negotiation.

Michigan law recognizes the complexity of these dynamics. Under MCL 722.23, for instance, courts are required to consider domestic violence when determining the best interests of a child. But this statutory recognition does not always translate effectively into procedural protections during mediation.

Domestic violence laws in Michigan provide vital protections for survivors. The Michigan Domestic and Sexual Violence Prevention and Treatment Board defines domestic violence as behavior that causes or intends to cause harm, fear, or intimidation between individuals in a close relationship. Survivors often seek legal remedies such as personal protection orders (PPOs), custody modifications, or divorce filings.

The Michigan Court Rules allow courts to waive mediation when it poses a risk of harm. Specifically, MCR 3.216(D)(3)(b) exempts cases where domestic violence creates an imbalance of power or safety concerns. Despite these provisions, some survivors may still face pressure to engage in mediation due to misconceptions about its neutrality or efficiency.

Attorneys representing clients in family law cases involving domestic violence face unique ethical challenges. The Michigan Rules of Professional Conduct require attorneys to act diligently and competently while safeguarding client confidentiality and advocating for their clients’ interests. When domestic violence is involved, attorneys must balance these duties with a heightened awareness of power dynamics and trauma.

In cases where mediation is proposed, attorneys have an ethical obligation to ensure their clients are fully informed of their rights and the potential risks involved. They should also consider whether mediation is appropriate, given the history of abuse and the clients’ capacity to negotiate freely.

Mandatory mediation in domestic violence cases can exacerbate existing inequalities. Survivors may feel pressured to agree to unfavorable terms to avoid further conflict or retaliation. Abusers, conversely, may exploit mediation as a platform to manipulate or intimidate survivors. Recognizing these risks, Michigan courts and legal professionals must advocate for case-by-case evaluations to determine whether mediation serves the interests of justice.

The presence of domestic violence creates inherent power imbalances that undermine the fairness of mediation. Survivors often enter the mediation process with a diminished sense of autonomy and self-confidence, making it difficult to assert their needs effectively. The fear of reprisal from an abuser may further coerce survivors into agreeing to terms that perpetuate inequity.

Domestic violence takes a profound psychological toll on survivors, impacting their ability to make sound decisions during mediation. Trauma, anxiety, and depression are common among survivors, affecting their concentration and judgment. At-

torneys must be attuned to these challenges and provide appropriate support to help their clients navigate the process.

Safety is a paramount concern in mediation involving domestic violence. Traditional mediation settings, where both parties are present, can expose survivors to further intimidation or harassment. Even in shuttle mediation, where the parties are separated, survivors may still feel unsafe knowing their abuser is nearby.

When children are involved, domestic violence complicates parenting plans negotiated through mediation. Survivors may feel compelled to agree to custody arrangements that prioritize co-parenting, even when it poses risks to the child’s well-being. Attorneys must advocate for arrangements that prioritize safety and stability for both the survivor and the children.

The Michigan Supreme Court’s Standards of Conduct for Mediators require mediators to screen for domestic violence at the outset of mediation. If abuse is suspected, mediators must assess whether mediation is appropriate and safe. However, the rigor and consistency of these screening procedures vary widely.

In practice, victims may underreport abuse due to shame, fear of retaliation, or a lack of trust in the process. Additionally, mediators are often not trained in trauma-informed care, which can lead to misinterpretation of a survivor’s behavior or needs.

MCR 3.216(D)(3) sets forth the situations where cases may be exempt from mediation. Cases may be exempt from mediation on the basis of the following: (a) child abuse or neglect; (b) domestic abuse, unless attorneys for both parties will be present at the mediation session; (c) inability of one or both parties to negotiate for themselves at the mediation, unless attorneys for both parties will be present at the mediation session; (d) reason to believe that one or both parties’ health or safety would be endangered by mediation; or (e) other good cause shown.

However, this exemption is not automatic. The burden of proof often falls on the survivor to establish the presence of abuse, which can be retraumatizing and may disincentivize disclosure.

This is why it is particularly important for attorneys to know their client and know their case. If attorneys feel that they can protect their client from manipulation and further abuse through

their zealous advocacy, then mediation can still be a good alternative to get a case resolved. However, if the abuser is overly aggressive or threatening, then mediation may not be the right avenue toward resolution.

Preparation is key to empowering survivors during mediation. Attorneys should educate their clients about their legal rights, the mediation process, and potential outcomes. ey should also address any safety concerns and explore accommodations, such as remote or shuttle mediation, to protect their clients. To mitigate power imbalances, courts may order shuttle mediation — where parties are kept in separate rooms — or allow virtual sessions. While these methods may reduce immediate physical intimidation, they do not eliminate psychological coercion or correct broader power differentials rooted in trauma.

When survivors of domestic violence are pressured into mediation, the results can be legally unjust and psychologically damaging. Abusers may use the process to prolong contact, manipulate agreements, or reassert control. is undermines the purported neutrality of mediation and can lead to unsafe parenting time arrangements, inequitable financial settlements, or further victimization.

Moreover, the adversarial yet confidential nature of mediation often means that coercive tactics are difficult to document or appeal. When outcomes are shaped by fear rather than fairness, the legitimacy of the legal process is compromised.

Selecting mediators who are trained in domestic violence dynamics is essential. ese professionals understand the complexities of abuse and can implement strategies to ensure a fair and balanced process. Attorneys should advocate for mediators who prioritize safety and confidentiality.

Attorneys play a critical role in advocating for resolutions that protect their clients’ interests. is may involve challenging proposals that perpetuate power imbalances or negotiating terms that prioritize safety and justice. Attorneys must remain vigilant in identifying and addressing any coercion or manipulation during mediation. Attorneys must use common sense, logic, and good judgment to determine whether a client appears to be entering into an agreement due to coercion or fear.

Professionals involved in Michigan family law cases bear a significant ethical responsibility when domestic violence is present. Judges must exercise discretion in exempting parties from mediation and ensuring appropriate safeguards are in place. Attorneys must advocate assertively for their clients’ safety and autonomy, particularly when facing pressure to pursue “cooperative” resolutions.

Sometimes, attorneys may take the fall, so to speak, for their client by making sure the opposing party and the mediator know that it is the attorney who is not allowing an agreement to move forward because it is they who do not believe it to be fair. is is very difficult for an attorney to do in advocating for their client’s best interests, but doing so in this fashion and taking the blame puts the spotlight on the attorney and takes it away from the client. is protects the client from possible future retaliation from the abuser once the mediation has concluded.

Mediators must be trained not only in conflict resolution but also in trauma-informed practice and the dynamics of abuse. Without this expertise, they risk becoming unwitting participants in a process that favors the abuser.

In cases where mediation is unsuitable, judicial alternatives provide a more structured and protective environment. Attorneys should consider requesting waivers for mediation and pursuing litigation or arbitration instead. While these processes may be more adversarial, they offer greater safeguards for survivors.

Protective orders and other legal remedies play a vital role in safeguarding survivors during dispute resolution. Attorneys should explore these options to provide their clients with added security and leverage during negotiations.

To ensure that mediation serves all families equitably and safely, several reforms should be considered:

Comprehensive, ongoing training should be required to help professionals recognize abuse patterns, assess risk, and respond appropriately.

2. Uniform Screening Tools and Procedures

e adoption of standardized, evidencebased screening tools can improve identification of domestic violence and consistency across jurisdictions.

3. Legal Counsel for All Parties in Mediated DV Cases

Survivors should have guaranteed access to legal counsel to prevent coercion and ensure informed decision-making.

4. Postmediation Judicial Review in DV Cases

When mediation occurs in cases with the presence of domestic violence, any resulting agreements should undergo heightened judicial scrutiny to assess fairness and voluntariness.

Domestic violence presents significant challenges to the mediation process, requiring attorneys to adopt a nuanced and empathetic approach. By understanding the impact of abuse on mediation dynamics and implementing best practices, attorneys can advocate for fair and equitable outcomes for their clients. Legal professionals have an opportunity to lead the way in creating safer and more effective mediation practices that prioritize the well-being of survivors.

While mediation offers many benefits in Michigan family law cases, it is not a one-sizefits-all solution. In situations involving domestic violence, the process can be retraumatizing, coercive, and fundamentally unjust if proper safeguards are not in place. Michigan courts, practitioners, and policymakers must continue to refine and enforce protections that recognize the unique challenges posed by abuse dynamics. Only then can mediation truly serve the best interests of families — and uphold the principles of justice and safety for all. rough diligent representation and a commitment to justice, attorneys can make a meaningful difference in the lives of those affected by domestic violence.

Channelle Kizy-White is a trusted family law attorney with over a decade of legal experience and a strong record of success. Known as a passionate advocate, she treats her clients’ battles as her own — o ering compassionate counsel and relentless representation. A proud South eld native from a large Chaldean family, Kizy-White is dedicated to protecting children, solving problems, and ghting for what’s best for families across Michigan. Her mission is simple: help people, every single day.

S ER VING H EALTHCA RE PR OV ID ERS FOR OVE R 30 Y EARS

Wachler & Associates represents healthcare providers, suppliers, and other entities and individuals in Michigan and nationwide in all areas of health law including, but not limited to:

•Healthcare Corporate and Transactional Matters, including Contracts, Corporate For mation, Mergers, Sales/Acquisitions, and Joint Ventures

•Healthcare Corporate and Transactional Matters, including Contracts, Corporate For mation, Mergers, Sales/Acquisitions, and Joint Ventures

•Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Third-Party Payor Audits and Claim Denials

•Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Third-Party Payor Audits and Claim Denials

•Licensure, Staff Privilege, and Credentialing Matters

•Provider Contracts

•Licensure, Staff Privilege, and Credentialing Matters

•Billing and Reimbursement Issues

•Provider Contracts

•Billing and Reimbursement Issues

•Stark Law, Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS), and Fraud & Abuse Law Compliance

•Physician and Physician Group Issues

•Stark Law, Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS), and Fraud & Abuse Law Compliance

• Regulatory Compliance

•Physician and Physician Group Issues

•Corporate Practice of Medicine Issues

• Regulatory Compliance

•Provider Participation/Ter mination Matters

•Corporate Practice of Medicine Issues

•Provider Participation/Ter mination Matters

• Healthcare Litigation

• Healthcare Investigations

• Healthcare Litigation

•Civil and Criminal Healthcare Fraud

• Healthcare Investigations

•Civil and Criminal Healthcare Fraud

•Medicare and Medicaid Suspensions, Revocations, and Exclusions

•Medicare and Medicaid Suspensions, Revocations, and Exclusions

•HIPAA, HITECH, 42 CFR Part 2, and Other Privacy Law Compliance

•HIPAA, HITECH, 42 CFR Part 2, and Other Privacy Law Compliance

S ER VING H EALTHCA RE PR OV ID ERS FOR OVE R 30 Y EARS

S ER VING H EALTHCA RE PR OV ID ERS FOR OVE R 30 Y EARS

By Gwendolyn Taylor and Emily Calabrese

For generations, society has ignored violence against women. To an extent, it makes sense why; collectively, we would rather blame individual victims and make excuses for perpetrators than accept our share of responsibility for a society that accepts abuse. To understand that such violence exists, we are required to confront the abusive acts that one human being has done to another, and not many people today have the capacity to do that effectively.

Domestic violence agencies and legal services organizations have focused on training attorneys and judges on simply recognizing and understanding domestic violence dynamics to help unravel generations of preconceived notions and bias about what society thinks a woman would or should do in an abusive relationship. It is likely that if you are still reading this article, you have been through some of that training or perhaps have personal experience navigating an abusive relationship for a client, friend, family member, or yourself.

The question I always hear after discussing domestic violence in family cases at a training or meeting is, “OK, so there’s domestic violence. What do I do for my client?” Many attorneys have represented clients in an abusive relationship, and it can take a lot out of a practitioner.

It is generally understood that it takes a victim an average of seven attempts to finally leave an abusive relationship. So, what if that victim presents to your office on the first attempt? You are the first person they have told their story to; the intake interview may have lasted over an hour. In that interview, you learned the parties have children and that the abusive partner is the primary wage earner. You also learned gruesome details of physical and sexual abuse and threats to kill your client. You set aside all other tasks and jump into action immediately drafting ex parte motions to protect this new client, and as soon as you have orders signed by the judge, you get a call from your client that the parties are reconciling because she is not ready yet and the abuser promised to change. But what if that new client had somebody to help them “get ready”? For this reason, Lakeshore Legal Aid, a nonprofit law firm in Oakland County, incorporated social service advocates into its practice in 2024. Social service advocates can provide a multitude of services to clients that support their nonlegal needs alongside the attorney’s legal representation. This article will discuss how an interdisciplinary approach with a social service advocate can assist attorneys in (1) connecting clients with valuable resources through referrals; (2) completing client safety planning; (3) providing trauma-informed care; and (4) managing cases and providing emotional support. Finally, specific examples of how this interdisciplinary approach can benefit a client will be discussed.

Domestic violence survivors contemplating legal action against their batterer may require additional resources beyond legal representation. For many, this may be the first time facing financial independence, which can be a barrier to leaving an abusive relationship for many survivors. Clients may need assistance

with various resources, such as housing, mental health services, public benefits, employment, professional clothing, food, etc. Furthermore, a survivor who is separating from their partner will be establishing a new routine without the help of the opposing party. While in this process, the client may need assistance with finding resources for child care, employment, support groups, physicians, and a multitude of other life necessities formerly shared with the opposing party. A social service advocate can provide referrals to agencies and initiate seamless connections with these organizations.

Some domestic violence survivors may be in immediate danger when reaching out for legal assistance; a common scenario is when the survivor remains living in the marital home with the batterer when seeking a divorce. In these circumstances, clients are particularly vulnerable, as separating from an abusive partner is one of the most dangerous times for survivors of domestic violence. Statistically, 75% of domestic abuserelated homicides occur once the survivor leaves or attempts to leave the relationship.1 Additionally, the fear of retaliation or physical harm can deter clients from proceeding with the divorce. One way to assist survivors during this time is to safety plan with the client. This could include connecting the client with local domestic violence shelters or exploring alternative options. If circumstances arise where a domestic violence shelter is not a viable option for the client, a social service advocate can help the client connect with loved ones regarding temporary living arrangements, locate housing resources, or develop an emergency safety plan within the home.

During this process, the social service advocate can also assist the client in navigating their emotions, as this can be a potentially scary time and is a high-risk/high-stakes situation for many survivors. Professional assistance with navigating resources, emotions, and safety planning strengthens the client’s ability to focus on their legal matter and helps them become litigation-ready.

Establishing a trauma-informed legal environment for your client is a great way to ensure your office is a safe space for domestic violence survivors. When a client is in crisis, there are many ways to ensure your client feels safe.

For some survivors, this may be the first time they are disclosing the abuse they have endured. Some survivors who have tried to reach out for help may have felt unheard or feel that nobody believes them. A client’s first interaction with your office is a great way to set the tone that you are there in allyship and that they can trust you and your team enough to disclose the abuse they have suffered.

While working with domestic violence survivors, you may also encounter a client who does not recognize that they are experiencing domestic violence. This could be due to a number of factors, including societal generalizations of domestic violence, religious or cultural beliefs, minimization of the client’s own experiences, or normalization. It is important to respect the client’s feelings around the subject and leave an open door for them to approach the matter at their own pace, as it can be very difficult for them to reconcile their status as a survivor. For example, there is a common misconception

that domestic violence is exclusive to physical harm. This narrative is dangerous as it does not encompass the multiple ways in which a person can experience abuse. A client who is finding out that their relationship was rooted in abuse, after believing domestic violence to be strictly physical, could possibly need time to process that information.

When disclosing domestic violence, clients may have a hard time expressing what they have gone through or may feel compelled to communicate all of their trauma upon their first interaction with you and your law firm. It is important to pay attention to the client’s temperament and try to assess what the client may need in those moments. Small gestures such as asking the client if they would like a drink of water or a quiet place to sit, or offering tissues when a client is crying, are all ways to establish with the client that you are actively listening. Simply asking the client what they need in that moment helps set a tone that the client has agency in this process and that you are willing to meet them where they are. More often than not, the survivors we encounter have not been allowed to make decisions, as their abusers control multiple aspects of their lives. Paying attention to the client’s cues will help determine how to best assist the client during their time of crisis.

Research has found that trauma can affect the brain and each survivor differently. Continuous trauma can affect how a client processes situations, regulates emotions, and perceives the world.2 It is helpful to have the entire office trained in trauma-informed practices, as well as how to notice signs of trauma. This will ensure that the client is in a safe space from the moment they walk into your office to complete an intake. Sometimes, clients come to receive legal services mere moments after they have experienced a domestic violence event. It is imperative that these situations are treated delicately so the clients are not being retraumatized or triggered.

Integrating a social service advocate into the legal team can allow the attorney to focus on the legal needs of the client while the social service advocate focuses on the nonlegal needs. It is important for both the social service advocate and the attorney to be open to each disciplinary perspective. Attorneys and social service advocates both share a common goal in committing to the client’s needs and helping the client through to the legal finish line. Social service advocates can assist attorneys in this way by working to remove the barriers that may prevent the client from accomplishing what the attorney is asking of them.

As an example, an attorney may reasonably ask for their client to come to court in a timely fashion and dressed in court-appropriate attire. The attorney may not know that the client no longer has access to a vehicle or their wardrobe, as the opposing party has restricted access. A social service advocate can assist the client in finding reliable transportation as well as resources for appropriate business apparel. Social service advocates are skilled in facilitating solutions to the manufactured barriers abusers create, while also providing some supportive care to the client.

Abusers often use a client’s financial and emotional hardships as a way to make them feel they have no way out and use that opportunity to continue their abuse. Even once the client and abuser have physically separated, the abuser will attempt to make the client’s life as difficult as possible. This could mean removing their access to their personal belongings, finances, and support systems. The removal of clients from a lifetime of social support, assets, and funds often places them in predicaments where they are forced to seek immediate resources. Many clients are interfacing with these resources and agencies for the first time and can become anxious about the process of separating their daily necessities from the opposing party.

Furthermore, there is a level of uncertainty many domestic violence survivors face when they are escaping an abusive partnership that can be equally as triggering as the abuse they experience. This uncertainty can be related to their personal safety, their standard of living, or the stigma often associated with shelters, therapy resources, and public benefits. The client may also experience some of the agencies having limited resources and find they need to contact several organizations to receive assistance. These occurrences can elicit feelings of confusion and shame in the client. In addition to helping the client navigate agencies and resources, the social service advocate can also hold space for the client to process their emotions and provide a judgmentfree ear.

It is important for the attorney and social service advocate to maintain frequent communication. Providing space to debrief and strategize helps to improve overall outcomes for the client, as their legal and nonlegal needs can be met in tandem. This also helps both parties gain a basic understanding of each discipline and meet the client’s needs in a robust and meaningful way. This typically evolves into the attorney and advocate developing an ability to spot areas where the client can benefit from each other’s service. This increases the ways in which a client can be supported and sets the client up for a more successful experience throughout the litigation process.

Trudy, a 35-year-old homemaker, had been married to her husband, an accountant, for eight years. The parties shared two minor children and a dog. Trudy’s husband had been physically and financially abusing her for the entirety of their marriage. Prior to their marriage, Trudy was a teacher, but she had not been allowed to work in the past six years. The opposing party had complete control over their finances. Trudy’s husband filed for divorce and declared that Trudy and the children were not allowed to stay in the home. Trudy was afraid that if she did not leave the home, he would kill them based on his threats. She was overwhelmed by the process of divorce and could not concentrate on the initial tasks her attorney asked her to complete. While at the office, Trudy was visibly upset and reported to her attorney that she simply could not focus, as she feared for her life.

Upon hearing Trudy’s concerns, her attorney invited a social service advocate to work with the client and help Trudy plan for her safety. The attorney briefed the social service advocate on details of the case. The advocate then spoke with Trudy and found that while she was open to going to a domestic violence shelter, she was worried that once she and the children left the home, the opposing party would turn his abuse toward their dog. The social service advocate and client called local domestic violence shelters and were able to locate a shelter that had space for Trudy and her children. The shelter was also partnered with a local pet shelter that allowed survivors to visit their pets, so Trudy was able to secure a safe placement for her dog. After Trudy and the children were safely out of the home, the social service advocate worked with the client on finding employment at a day care center and helped the client enroll the children in after-school programs. As Trudy began to feel safe and more secure in her finances, her ability to focus on her divorce and be an active partner with her attorney drastically improved.

Another example to consider is that of Hank, a 69-year-old retiree who had been working with his attorney and advocate team for three months. Hank was physically separated from his wife and had been living in a retirement community for the past two months. Prior to his leaving the home, Hank’s wife had been tracking all of his devices and his vehicle. The opposing party threatened to shoot him with her gun several times throughout their relationship. Hank expressed to his team that he believed his wife had started tracking him again, and he was no longer able to access his email, phone, and social media accounts. All of Hank’s important documents and financial information were saved in his email and various accounts. This was

incredibly difficult for Hank to navigate, as he was not as technologically savvy as the opposing party. Hank also noticed that he had started to see his wife in public spaces that he frequented and had seen her car circle his apartment complex on at least three different occasions. He expressed that he was worried his wife was going to attempt to do something awful and that he was too afraid to leave his home to meet with his attorney.

As the attorney worked on a personal protection order for Hank, the social service advocate worked with the client on creating a safety plan for his residence and the public spaces he frequented. e social service advocate was also able to facilitate a meeting with Hank’s landlord and incorporate them into a safety plan. After the client had a safety plan in place, the social service advocate assisted Hank in contacting his phone service provider, his email provider, and the relevant social media companies to help him regain access to his devices and accounts. ey were then able to apply security features to his devices to prevent future incidents. With additional safety precautions in place, Hank felt safer leaving his home, was able to attend meetings with his attorney at the office, and again had ac-

cess to all of the documents his attorney needed to successfully litigate Hank’s case.

Without their advocates’ services, Hank and Trudy would have faced tasks that felt impossible for them, increasing the likelihood of reconciliation or inequitable results. Having the advocates’ support allowed them to actively and productively participate in their cases, which undoubtedly made their attorneys’ jobs easier.

At Lakeshore, the overall results of this interdisciplinary model have been positive with benefits for all. Clients get the benefits of an effective referral network, trauma-informed care, case management, and emotional support. Attorneys are able to focus on legal work, increase efficiency, and enjoy the benefits of having an organized client prepared for litigation.

Gwendolyn Taylor, a client support advocate, has been working with survivors of domestic violence as part of a multidisciplinary team at Lakeshore Legal Aid since 2022. Prior to working at Lakeshore, Taylor was

a child and family advocate for Kids-Talk Child Advocacy Center in Wayne County. Taylor has demonstrated experience advocating for survivors of domestic violence, human tra cking, and child abuse and has a passion for increasing access to justice for everyone.

Emily Calabrese is the former chief advocacy o cer at Lakeshore Legal Aid. Along with others at Lakeshore, Calabrese created the Client Support Advocacy department to better serve clients and allow lawyers time to focus on legal work. Calabrese is a member of the Domestic Violence Committee of the Family Law Section of the State Bar of Michigan and focuses a lot on education around lethality factors in abusive relationships.

Footnotes:

1. stoprelationshipabuse.org/educated/barriers-toleaving-an-abusive-relationship.

2. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191.

One of the most downloaded podcasts is The New York Times’ The Daily, which highlights one contemporary news topic each weekday for anywhere from 20 to 40 minutes. One of the show’s primary hosts, Michael Barbaro, is known for expressing his curiosity about a show’s topic or interviewee’s comment by uttering an uncanny “Hmmm.” It serves as an alert to listeners that something interesting is afoot or about to occur. It is my hope the title to this article elicits the same trigger with Laches readers.

I have had the privilege of being involved with both the Oakland County Bar Association and Oakland County Bar Foundation for several years. Frankly, someone in my predicament has no excuse for being ignorant about the primary differences between these two venerable institutions.

Over the years, however, I can think of countless examples when attorneys have confused the OCBF and OCBA. I am reminded of this every year before the OCBF’s annual Signature Event fundraiser in May, when many colleagues and friends innocently ask me if I am going to the “Oakland Bar Association Event.”

By Andrew M. Harris

Even more frequent than the confusion in the organizations’ names is the understandable lack of awareness about how the OCBF differs from the OCBA and vice versa. To help with this confusion, here is a brief summary of the OCBF and OCBA, followed by a section about how the institutions overlap.

The OCBF is a charity under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, originally formed with the sole purpose of supporting the Adams-Pratt Oakland County Law Library. In 1988, the organization expanded its mission to create a greater impact and renamed itself the Oakland Bar-Adams Pratt Foundation. This revised mission (always included as part of the president’s monthly article) is to ensure access to justice and promote an understanding of law in our community. Later, in 1999, the OCBF took on its current name.

The OCBF comprises a five-member Exec-

The Oakland County Bar Foundation’s mission is to ensure access to justice and an understanding of the law in our community. It is dedicated to:

Improving and facilitating the administration of justice in Oakland County and throughout the state of Michigan;

Ensuring to the fullest extent possible that legal services are made available to all members of the public;

Promoting legal research and the study of law as well as the diffusion of legal knowledge;

Promoting the continuing legal education of lawyers and judges; and

Educating the public as to their legal rights and obligations, and fostering and maintaining the honor and integrity of the legal profession.

If you know an organization that could use assistance to pursue these goals within Oakland County, please refer them to ocba.org/ocbfgrants, where they can find information about applying for a grant from the foundation.

utive Committee, a 20-member board of trustees, and 24 emeritus members (all of whom served at least one year as trustees). Katie Tillinger serves as the OCBF’s deputy director, leading the foundation with her 18 years of experience and oversight of all the foundation’s work (internal and public-facing).

Collectively, this group meets many times throughout the year as a full board and in five separate committees (Fellows, Finance, Fundraising, Planning, and Projects). This work involves countless tasks, including budgeting, financial review, exhaustive event planning, grant application evaluation, and internal governance. Among many other accomplishments (often immeasurable), the foundation doled out over $185,000 last year to qualified recipients (one of them, Catholic Charities of Southeast Michigan, was profiled in last month’s edition of Laches). For more information about the OCBF, you can visit its website at ocba.org/ocbf.

The OCBA is a nonprofit organization under Section 501(c)(6) of the Internal Revenue Code (for trade organizations) that helps attorneys, judges, paralegals, law professors, and law students in Oakland County/metro Detroit build their careers through continuing education, committees, networking events, and volunteer opportunities. Formed in 1934 with under 50 attorneys, the OCBA now has nearly 2,500 members. The OCBA also has five officers along with a 15-person board, elected by OCBA members. Day-to-day, the OCBA is overseen by a 10-member staff and led by its executive director, Jennifer Quick.

Some of the OCBA’s more noteworthy

events for members include its Holiday Gala, Taste of Diversity, Annual Meeting & Awards Ceremony, and Circuit-Probate Court Bench/ Bar Conference. e public also benefits from the OCBA through its elementary mock trial program, Youth Law Conference, Judicial Candidate Forums, Senior Law Day, Lawyer Referral Service, and other law clinics. For more information about the OCBA’s services to its members and the public, you can visit its website at ocba.org.

While the OCBF and OCBA have separate missions, governance, planning, and operation, their work is not entirely separate. Realizing the opportunity of shared resources, the OCBF and OCBA entered into a formal agreement in 2002, since amended in 2003 and 2017. e thrust of this agreement promotes the organizations’ overlapping purposes and includes, among other terms, the following:

• Six members of the OCBF’s board shall be appointed by the OCBA board of directors (and shall include the OCBA president-elect and vice president).

• At least two-thirds of the OCBF trustees have to be OCBA member attorneys.

• e OCBA actively assists the OCBF in its fundraising efforts.

• e OCBA provides valuable administrative resources to the OCBF in exchange for an annual expense payment.

While the agreement reflects the organizations’ binding obligations to one another, practically, they work together harmoniously on a continuing basis for mutual benefit.

e legal community is fortunate to have both the OCBF and the OCBA serving the public and those in the legal field. e community is also fortunate that these organizations have the good judgment, foresight, and spirit of cooperation to work with each other when appropriate for their mutual benefit.

Now that you know more about how these organizations are the same and how they are different, you will be less likely to say you are going to the “Association Event” when attending the OCBF Signature Event in May 2026!

Andrew M. Harris is a shareholder with Maddin Hauser Roth & Heller P.C. in South eld, Michigan, where his practice includes business litigation and commercial real estate. Harris is also a licensed civil mediator. He lives in Birmingham with his wife (Ti any), two teenage sons (Roger and Russell), and two dogs (Maizey and Blue).

There are many topics in life that we know we should address but put off because the issue makes us uncomfortable in some way. Depending upon the individual, this list could include a trip for an annual physical, a colonoscopy, a mammogram, a visit with the dentist, an appointment with the accountant, calling the plumber about that slow drain or leaky pipe, or preparing a will or other estate planning documents. Today, I challenge you to add, and to resolve, another item on that list if you are an active attorney in private practice — planning for your practice in case you become temporarily or permanently incapacitated.

Like many article topics that I have written about, this one arises from issues in the court. It brings to mind a saying often attributed to Benjamin Franklin: “If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.”1

You may recall that in 2023, the Michigan Supreme Court adopted proposed Michigan Court Rule Subchapter 9.300 and Rule 21, Mandatory Interim Administrator Planning, of the Rules Concerning the State Bar. ese provisions created new obligations for attorneys in private practice and for the State Bar of Michigan. However, in the hustle and bustle of everyday life and the frenzy of maintaining a practice, it is possible that this recent obligation has not risen to the top of your to-do list beyond perfunctorily checking a box when you renew your bar membership each year. With this in mind, I offer the following refresher on interim administrators.

Interim administrators may be appointed by the circuit court in the county in which the affected attorney lives or practices or designated by the practicing attorney. MCR 9.301(C) and (D). An interim administrator is “an active Michigan attorney in good standing who serves on behalf of a Private Practice Attorney who becomes an Affected Attorney.” MCR 9.301(E). e term “interim administrator” also includes “a law firm with at least one other

By Richard Lynch

active Michigan attorney that is designated to serve on behalf of a Private Practice Attorney who becomes an Affected Attorney.” Id Michigan attorneys in private practice “must designate an Interim Administrator to protect clients by temporarily managing the attorney’s practice if the attorney becomes unexpectedly unable to practice law as set forth in MCR 9.301 and pursuant to Rule 2(B) of the Rules Concerning the State Bar of Michigan.” Rules Concerning the State Bar, Rule 21(A). Each private practice attorney must also “identify a person with knowledge of the location of the attorney’s professional paper and electronic files and records and knowledge of the location of passwords and other security protocols required to access the attorney’s professional electronic records and files.” Rules Concerning the State Bar, Rule 21(A)(2). ose in private practice have an annual obligation to certify their compliance with the interim administrator requirements and whether they are willing to serve as an interim administrator for other bar members. Rules Concerning the State Bar, Rule 2(B)(2) and (C).

In a perfect world, the interim administrator requirements would operate as an unutilized best practice, much like we wish for our auto, home, or life insurance policies. Life experience suggests that this Pollyannaish desire is unrealistic. e State Bar of Michigan reports that four interim administrators were appointed in 2024 and seven have been appointed in 2025

as of the time of the submission of this article.2

Based upon my glancing interaction with the interim administrator process, instances in which an appointment is needed will carry a level of urgency — thus the importance of private practice attorneys establishing the foundation for the process by fully complying with the requirements of the governing rules. By failing to properly plan for the appointment of an interim administrator, the affected attorney delays the process designed to protect the interests and rights of the underlying clients. For professionals who swear or affirm an oath to protect the client and the administration of justice, the passing discomfort of contemplating a temporary or permanent change in life circumstances that leaves one unable to practice law seems a small price to pay for the protection this practice offers to one’s clients and practice.

I thank you in advance for your compliance with this requirement and pray that you never require its use.

Richard Lynch is the court administrator for the Oakland County Circuit Court.

Footnotes:

1. quoteinvestigator.com/2018/07/08/plan, last accessed August 5, 2025. Of note, while Ben Franklin may never have uttered this proverb, many wise individuals have stated something similar to it, including John Wooden.

2. michbar.org/appointments, last accessed August 5, 2025.

“If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.” —attributed to Benjamin Franklin1

7/14/2025

7/15/2025

7/22/2025

7/1/2025

7/7/2025

7/1/2025

7/8/2025

7/22/2025

6/23/2025

Cohen

Cohen Anderson

Gant O'Brien

2024-291521-FC People v. Bryngelson

2024-290369-FH

People v. Hurford

2025-293508-FH People v. Cornell

2020-503106-DM

R. Moses v. D. Moses

2025-292633-FH People v. Hopkins

2024-289196-FH People v. Witgen

2024-291097-FH People v. Sherban

O'Brien

Valentine

7/21/2025

7/29/2025

7/14/2025

AlexanderVisiting Judge

Ronayne KrauseVisiting Judge

YoungVisiting Judge

2024-290113-FH People v. Majette

2024-205547-CB

Biotech Clinical Lab v. RSL Medical Marketing

2025-292356-FH People v. Marland

2023-285448-FH People v. Joseph

2023-202740-NH

P. Spagnuolo v. A. Wahab

Stephen Frey

Robyn Kennedy

Dillon Salge

Mitchell Foster

Danielle Librandi Tameka Tucker

Tova Shaban

Jason Abel, Henry Nirenberg

Jason DeSantis, Amanda Hudson

Duane Johnson

Qamar Stamos

Bruce Leach

Qamar Stamos

Michael O'Malley

Allison Krueger

Scott Kozak

Mark Rossman

Philip Cwagenberg

Andrew McGarrow

Paul Stablein

Danielle Librandi

Paul Curtis

Euel Kinsey, Gerald Thurswell

John Ramar, Douglas Durfee

Cts. 1-4, 6-7, 9-11, 16-17

CSC 1st Deg., Cts. 5, 8, 15 CSC 2nd Deg., Cts. 12-14 CSC 1st Deg. (Relation)

CSC 3rd Deg. (Force)

Felon Poss. Firearm, Weapons - Ammunition Felon

Divorce/Minor Children3rd Party Joinder

Weapons - Poss. by Prohibited Person, Weapons - FF

OWI 3rd Offense, DWLS

OUIL - Occupant <16 - 2nd or Sub. Offense

Assault w/ I to do GBH, Child Abuse 4th Deg.

Larceny $1K-$20K

Medical Malpractice

Plunkett Cooney is pleased to announce that Madeleine C. Craig has joined the firm’s Commercial Litigation practice group in its Bloomfield Hills office. Craig represents clients in state and federal courts to resolve disputes involving breach of contract, warranty claims, shareholder conflicts, and real estate and general business issues.

Craig also maintains a robust transactional practice wherein she works with clients to provide them with advice and counsel on all stages of business operations, including entity formation, regulatory compliance, business planning, and capital financing. She routinely negotiates and drafts contracts for the purchase and sale of real estate, landlord/tenant contracts, property management agreements, financing statements, and operating agreements.