Relationships between neuroactive steroids, GABA, and glutamate MRS and functional connectivity in postpartum depression Tiffany

1 Porras ,

MPH, Kristina M.

1,2 Deligiannidis ,

MD

1Donald

and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell 2Division of Psychiatry Research, Women’s Behavioral Health, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, New York, NY

Background

Methods

Results

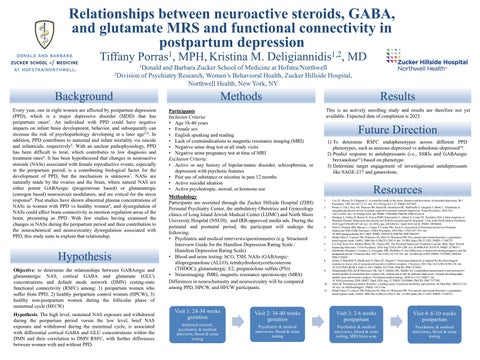

Every year, one in eight women are affected by postpartum depression (PPD), which is a major depressive disorder (MDD) that has peripartum onset1. An individual with PPD could have negative impacts on infant brain development, behavior, and subsequently can increase the risk of psychopathology developing at a later age2-4. In addition, PPD contributes to maternal and infant mortality via suicide and infanticide, respectively5. With an unclear pathophysiology, PPD has been difficult to treat, which contributes to low diagnosis and treatment rates6. It has been hypothesized that changes in neuroactive steroids (NASs) associated with female reproductive events, especially in the peripartum period, is a contributing biological factor for the development of PPD, but the mechanism is unknown7. NASs are naturally made by the ovaries and the brain, where natural NAS are either potent GABAergic (progesterone based) or glutamatergic (estrogen based) neurocircuit modulators, and are critical for the stress response8. Past studies have shown abnormal plasma concentrations of NASs in women with PPD vs healthy women9, and dysregulation of NASs could affect brain connectivity in emotion regulation areas of the brain, presenting as PPD. With few studies having examined the changes in NASs during the peripartum period and their contribution to the neurochemical and neurocircuitry dysregulation associated with PPD, this study aims to explore that relationship.

Participants Inclusion Criteria: • Age 18-40 years • Female sex • English speaking and reading • Lack of contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) • Negative urine drug test at all study visits • Negative urine pregnancy test at time of MRI Exclusion Criteria: • Active or any history of bipolar/manic disorder, schizophrenia, or depression with psychotic features • Past use of substance or nicotine in past 12 months • Active suicidal ideation • Active psychotropic, steroid, or hormone use

This is an actively enrolling study and results are therefore not yet available. Expected date of completion is 2025.

Hypothesis Objective: to determine the relationships between GABAergic and glutamatergic NAS, cortical GABA and glutamate (GLU) concentrations and default mode network (DMN) resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) among: 1) peripartum women who suffer from PPD, 2) healthy peripartum control women (HPCW), 3) healthy non-postpartum women during the follicular phase of menstrual cycle (HFCW) Hypothesis: The high level, sustained NAS exposure and withdrawal during the peripartum period versus the low level, brief NAS exposure and withdrawal during the menstrual cycle, is associated with differential cortical GABA and GLU concentrations within the DMN and their correlation to DMN RSFC, with further differences between women with and without PPD.

Methodology Participants are recruited through the Zucker Hillside Hospital (ZHH) Perinatal Psychiatry Center, the ambulatory Obstetrics and Gynecology clinics of Long Island Jewish Medical Center (LIJMC) and North Shore University Hospital (NSUH), and IRB-approved media ads. During the perinatal and postnatal period, the participant will undergo the following: • Psychiatric and medical interviews/questionnaires (e.g. Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale / Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) • Blood and urine testing: hCG, TSH, NASs (GABAergic: allopregnanolone (ALLO), tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC); glutamatergic: E2, pregnenolone sulfate (PS)) • Neuroimaging: fMRI, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) Differences in neurochemistry and neurocircuitry will be compared among PPD, HPCW, and HFCW participants.

Future Direction 1) To determine RSFC endophenotypes across different PPD phenotypes, such as anxious-depressed vs anhedonic-depressed10. 2) Predict response to antidepressants (i.e., SSRIs and GABAergic brexanolone11) based on phenotype. 3) Determine target engagement of investigational antidepressants like SAGE-217 and ganaxolone.

Resources 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9.

10. 11.

Cox JL, Murray D, Chapman G. A controlled study of the onset, duration and prevalence of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993 Jul;163:27-31. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.1.27. PMID: 8353695. Posner J, Cha J, Roy AK, Peterson BS, Bansal R, Gustafsson HC, Raffanello E, Gingrich J, Monk C. Alterations in amygdala-prefrontal circuits in infants exposed to prenatal maternal depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;6(11):e935. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.146. PMID: 27801896; PMCID: PMC5314110. Madigan S, Oatley H, Racine N, Fearon RMP, Schumacher L, Akbari E, Cooke JE, Tarabulsy GM. A Meta-Analysis of Maternal Prenatal Depression and Anxiety on Child Socioemotional Development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;57(9):645-657.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.012. Epub 2018 Jul 20. PMID: 30196868. Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG, Stein A. Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child Outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 1;75(3):247-253. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4363. PMID: 29387878; PMCID: PMC5885957. Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders: a populationbased register study. JAMA. 2006 Dec 6;296(21):2582-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. PMID: 17148723. Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, Gaynes BN. The Perinatal Depression Treatment Cascade: Baby Steps Toward Improving Outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77(9):1189-1200. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15r10174. PMID: 27780317. Sundström Poromaa I, Comasco E, Georgakis MK, Skalkidou A. Sex differences in depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Neurosci Res. 2017 Jan 2;95(1-2):719-730. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23859. PMID: 27870443; PMCID: PMC5129485. Sarkar J, Wakefield S, MacKenzie G, Moss SJ, Maguire J. Neurosteroidogenesis is required for the physiological response to stress: role of neurosteroid-sensitive GABAA receptors. J Neurosci. 2011 Dec 14;31(50):18198-210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2560-11.2011. PMID: 22171026; PMCID: PMC3272883. Deligiannidis KM, Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Tan Y, Dubuke ML, Shaffer SA. Longitudinal proneuroactive and neuroactive steroid profiles in medication-free women with, without and at-risk for perinatal depression: A liquid chromatographytandem mass spectrometry analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020 Nov;121:104827. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104827. Epub 2020 Aug 13. PMID: 32828068; PMCID: PMC7572700. Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:21929. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. PMID: 14711766. Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders: a populationbased register study. JAMA. 2006 Dec 6;296(21):2582-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. PMID: 17148723.

Visit 1: 24-34 weeks gestation

Visit 2: 34-40 weeks gestation

Informed consent, psychiatric & medical interview, blood & urine testing

Visit 3: 2-6 weeks postpartum

Visit 4: 6-10 weeks postpartum

Psychiatric & medical interviews, blood & urine testing

Psychiatric & medical interviews, blood & urine testing, MRI brain scan

Psychiatric & medical interviews, blood & urine testing