HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART

Long before Hofstra was founded, indeed before there was “Long Island,” the Indigenous peoples called this region Sewanhacky, Wamponomon, and Paumanake — sacred territory inhabited by the Carnarsie, Rockaway, Matinecock, Merricks, Massapequa, Nissequoge, Secatoag, Seatauket, Patchoag, Corchaug, Shinnecock, Manhasset, and Montauk. Each tribe had its own territory, whose boundaries were respected by the others, and all inhabitants were united in their shared desire for peace. The land that surrounds Hofstra is part of that history. We want to protect its legacy and honor the Indigenous peoples who have made untold contributions to our region.

September 2-December 16, 2025

Emily Lowe Gallery

Curatorial Team

Team Love

Jamel Shabazz

Robert Dupreme Eatman

Bilal Polson

Principal, Northern Parkway School Uniondale, New York

Erik Sumner

Art Educator, Northern Parkway School Uniondale, New York

Alexandra (Sasha) Giordano Director, Hofstra University Museum of Art

Guest Essayist

Chris Gampat

Editor in Chief, The Phoblographer

The Hofstra University Museum of Art’s programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.

This project is supported by Long Island Grants for the Arts through funds provided by the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature, and administered by the Huntington Arts Council.

Alexandra (Sasha) Giordano, Director, Hofstra University Museum of Art

An exhibition is not just about seeing. It’s about discovering, connecting, and researching. Art serves students’ and guests’ curiosity by offering original sources and inviting all to look beyond what they think they know. Art meets the community where it is. It says, “I don’t know you yet, but look at me, understand me, question me, feel me” — and somehow, through that shared experience, a transformation happens.

Early mornings, one may find the Emily Lowe Gallery filled with local third-grade students exploring non-Western artifacts. Some of these students are having their first museum experience or stepping onto a college campus for the first time. On other mornings, high school students may participate in a new program that cultivates conversations about the arts and introduces them to fine arts faculty, creating pathways to a soaring creative future. Another afternoon, one may find a professor encouraging their students to write ekphrastic poetry inspired by a work of art, which will then be performed with passion for their classmates. All while community groups and visitors filter in and out of the gallery. As day turns to night, the gallery may become a venue for an open mic night event, where students share their artistic creations in response to the current exhibition. Later that same week, evening programming may include a panel discussion or exhibition tour, offering the public stimulating and thought-provoking art experiences. Academics, artists, community members, and students can be found shoulder to shoulder, contemplating ideas about art and beauty, questioning all that is right and wrong with the world we live in, collectively expanding our minds.

Community is the heart of a museum.

The exhibition Love Is the Message: Photography by Jamel Shabazz was conceived with this spirit and curated by Team Love, a collective partnership composed of the artist Jamel Shabazz; Robert Dupreme Eatman; Dr. Bilal Polson, principal of Northern Parkway School in Uniondale, New York; Erik Sumner, art educator at Northern Parkway School; and the Hofstra University Museum of Art. Over two years, slowly and carefully, through meeting after meeting, the exhibition took shape from concept to fruition.

With Team Love’s valuable insights, Love Is the Message honors 50 years of Jamel Shabazz’s artistic achievement and is his first solo exhibition on Long Island — a fitting location as he is a longtime resident of Hempstead, New York. The works on view serve as a retrospective of Shabazz’s street photography from the 1980s to the present, capturing the evolution of hip-hop culture, fashion trends, and music. Above all else, Love Is the Message is a celebration of community that highlights the bonds of friends and family. Through the medium of photography, Shabazz has created an enduring archive of memory and meaning with images that not only reflect the times in which they were made but continue to speak to today’s conversations around race, representation, and belonging.

Love Is the Message explores how Jamel Shabazz’s work occupies a vital space at the intersection of art, activism, and cultural storytelling. Deeply influenced by trailblazers like Gordon Parks, Shabazz embraces the camera not just as a creative tool but as a means of witnessing everyday life within Black and Brown communities. Shabazz centers dignity, resilience, and beauty in his portraits by capturing not only how his subjects look, but how they

live and love. His lens is one of empathy, inviting viewers not simply to observe but to feel and to witness the quiet strength of a father holding his child, the joy in a group of friends dressed for a block party, or the pride in a young person striking a confident pose. In this way, Shabazz’s work does more than document; it cultivates understanding, mends division, and illuminates the shared humanity that connects us all.

In Shabazz’s own words, his work is “visual medicine,” underscoring the power of the arts. Art can heal what is broken, connect what was severed, and deliver messages of peace, hope, and love, which are much needed in today’s world.

We are grateful to the following participants, whose support helped deliver Jamel Shabazz’s legacy of love:

Team Love for creating this beautiful exhibition in a time when it is needed most.

Art Bridges who generously loaned and funded the transportation of two works of art: Native Son (Circus) (2006) by Terry Adkins and Bronzeville at Night (1949) by Archibald John Motley Jr. These works complement and amplify the themes and visual language present in Jamel Shabazz’s photography and provide historical context.

Hofstra University administration for their ongoing support of our endeavors.

Hofstra Cultural Center for co-sponsoring the Exhibition Reception.

Hofstra University Drama and Dance Department for being a kind neighbor and sharing the dance studio for the Exhibition Reception.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Advisory Committee for their continued encouragement, creativity, and participation.

Hofstra University Museum of Art staff and students who show up every day committed to making the world a better place through the arts.

Huntington Arts Council for funding the Shabazz Public Engagement Project, a series of public programs organized by the Hofstra University Museum of Art. The project is supported by Long Island Grants for the Arts through funds provided by the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature, and administered by the Huntington Arts Council.

The Uniondale Community Council for their guidance, participation, and communication efforts.

The Hofstra University Museum of Art is more than a building full of objects. It’s a bridge between Hofstra University and the neighborhood, between the past and the present, between knowledge and meaning. Through inclusive, interdisciplinary opportunities and socially responsible exhibitions and programs, it teaches, preserves, listens to, and belongs to every member of the community who walks through its doors.

Chris Gampat, Editor in Chief, The Phoblographer

Beauty and realism can sit at the same table and serve collaborative dishes to the pop-up dinner experience that is real, human photography. It doesn’t need to be looksmaxxed or Photoshopped with a makeup artist or use generative AI to make it more idyllic to conform to a beauty standard. Because the truth is that life doesn’t conform. I like to joke with my friends that I can use Jedi mind tricks to slow the 7 train downtown as it rolls onto the platform — and so I put my hand out and squish my face up as if it’s happening in real-time. But the truth is that physics is part of life. And life will always be something we need to realize and see for what it is.

The esteemed Jamel Shabazz is a photographer who embodies these ideas and whose work today reminds us that there is beauty in life all around us. We, as humans, just need to accept it and not worry about what trends, Instagram, social media, and other things are telling us to do. Beauty is as ingrained in the nearest human as in the simulation you’re staring at on your phone.

Most importantly, Mr. Shabazz’s work reminds us that we can sometimes even interact with that beauty instead of shyly observing. This is something that humanity has largely forgotten how to do after COVID. But as you stare into Uncle Jamel’s work, your mind can venture into many different directions, figuring out how he took his photos.

If you’re here, let’s be our most honest selves. For many of you, I’m sure that I don’t need to tell you the legend of Jamel Shabazz — so you can skip this paragraph. But for those of you first introduced to Mr. Shabazz, I hope you’re excited about the treat you’re about to see.

“I first fell in love with photography as a very young child, still in my single digits,” Mr. Shabazz told The Phoblographer in a 2013 article. “I think the infatuation came when I picked up my father’s Navy tour books featuring hundreds of beautiful black and white images chronicling his six years aboard the USS Aircraft Carrier Intrepid. He was assigned as one of the ship’s photographers, and the photos were composed of single portraits and group shots of the various units and personnel stationed aboard the ship.” He recalls seeing images from Europe and being in awe at the contrast between there and America.

Many of you may already know that he traveled around NYC, documenting real New Yorkers and real humans to show a more authentic side of the city and the communities around him.

“All too often, people look at my earlier photographs and basically see the fashion and swagger, but what I saw was the soul of a people that were coming of age during a very troubling day and time,” Mr. Shabazz told The Phoblographer in an interview. “My attraction to them was grounded in my deep desire and dedication to connect with young people both within and outside of my city, who were at the greatest risk of premature death and incarceration.”

In many ways, Mr. Shabazz’s work has influenced the work of many street fashion photographers. We can see his work in those like Scott Schuman — otherwise known as The Sartorialist — and so many other street fashion photographers who also interact with their subjects to get genuine poses.

Something Mr. Shabazz would often say is the following:

“With all due respect, I’m a photographer. When I look at you and your crew, I see greatness. If you don’t mind, I’d like to take your photograph.”

Indeed, Mr. Shabazz prioritized humans, which many of us feel is lacking in a world of hyper-capitalism, economic disparity, and social media echo chambers.

To get the images that he made, he often brought physical albums filled with his photographic portfolio with him. Folks would page through them, and then he’d eventually get their approval. Physical albums are an essential component of this. Put one in the hands of someone today, and they’ll probably page through it very slowly. Additionally, it’s a physical feeling that they don’t often get anymore or even at all. Instead, everything is typically digitized, and people commit random acts of scrolling due to addiction to the dopamine casinos that are brought to us by smartphones. When you scroll, you’re not really taking in the images. But the moment is completely changed when you put prints in front of people. If used today, this practice would probably encourage even more photographers to slow down and make better pictures for their own internal validation instead of for external validation.

In Uncle Jamel’s images, we can see this idea put forth. He isn’t shooting for likes, hearts, upvotes, or to make it really big in magazines. Instead, that happened organically with his people skills. Instead, Uncle Jamel is shooting for his internal validation first and foremost. His internal validation was well cared for, and he was fed a nutritious diet of the work of good photographers and solid symbiotic values. These mutualistic ideals are seen in the results of the images he makes.

Just think about it: How would you ask for someone’s portrait randomly and on the spot while you were on the NYC subway, for example? Photojournalists, for years, have used their people skills and eventually made people become accustomed to the camera around them.

Those images are some of Mr. Shabazz’s most famous — but his more candid street and high-end fashion photography is also noteworthy.

Mr. Shabazz’s roots are in New York City, and his travels have taken him from large wars abroad to smaller conflicts back home. But when he returned home to America, he traded in guns for cameras, maps for chessboards, and rations for orange juice and bananas.

By all means, you can’t fight every war with saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal. And realistically speaking, not everything is a war or a sports game. It’s a real-life situation that has to be approached from a place of humanity first.

Back in the day, and stemming from his time as a correctional officer, conflict resolution was a big part of what he did, and using the camera to document those around him became very important. Feeding from the fruit tree of Gordon Parks, Leonard Freed, Edward S. Curtis, Eve Arnold, and documentary photographer Joseph Rodriguez, Mr. Shabazz brought the seeds of photography with him through his journey and cultivated a rich photographic career. Throughout this career, there were several collaborators in his photographs. But at the center of this atelier is Jamel Shabazz and his ability to see humans first in his images.

Depending on who you spoke to today, photography teachers would tell you all about the technicalities of how to make an image. But they wouldn’t necessarily talk to you about the emotional communication or how to speak that language. Jamel Shabazz’s images are fluent in this vernacular. Uncle Jamel trades in technical excellence for a storied career in human excellence that most photographers born of the internet can never have.

In fact, perhaps the most famous photographer to shoot in a way similar to what Uncle Jamel has done is photographer Brandon Stanton — otherwise known as Humans of New York (2013).

I’ve been lucky enough to observe how Uncle Jamel works to this day. Working alongside Mr. Shabazz is quite a treat. He greets everyone with warmth, compliments, and personalized lines that are suited to each human, like a comfortably fitting piece of jewelry they can adorn themselves with. Then, he’ll often pose people and ask for different profiles. After they’ve feasted on his words and enjoyed their fill, those he photographs often seem ready for anything the world will throw at them. This demeanor is a fine wine that Jamel Shabazz has grown and aged all himself, and he shares its invigorating nectars with everyone’s cups. If you truly haven’t felt like your own emotional cup has received its fill, you’ll surely feel it after shooting and conversing with Uncle Jamel.

By Robert Dupreme Eatman

I was 12 when I first met Jamel Shabazz, introduced by my older sister who, in her wisdom, saw something kindred in our spirits. That introduction, casual at the time, would mark the beginning of one of the most defining relationships of my life. Jamel became more than a mentor or a friend — he became my big brother. Over the years, he has served as my mirror, my compass, and my challenger. And in many ways, his art, like his presence, has always held space for who I was and who I could become.

Jamel saw in me what few adults recognized at that age: a gifted young man in tune with his inner voice, already forming questions about culture, society, and politics. Rather than dismiss or hush me, he listened. He encouraged me to sharpen my thinking and deepen my understanding. Our bond grew, shaped by mutual respect and a shared commitment to excellence. Love Is THE Message was not just a mantra — it became our guiding principle.

I was a sponge, soaking up his wisdom — especially his gift for helping me process life’s challenges by encouraging me to consider a more balanced perspective. I remember vividly when he introduced me to my first health food store on the corner of Jay and Willoughby Streets in downtown Brooklyn. That’s where I first learned about many organic foods like sprouts, wheatgrass juice, and bee pollen. Every visit came with a new “supplement.” In hindsight, I actually may have been his test subject. More on that another time.

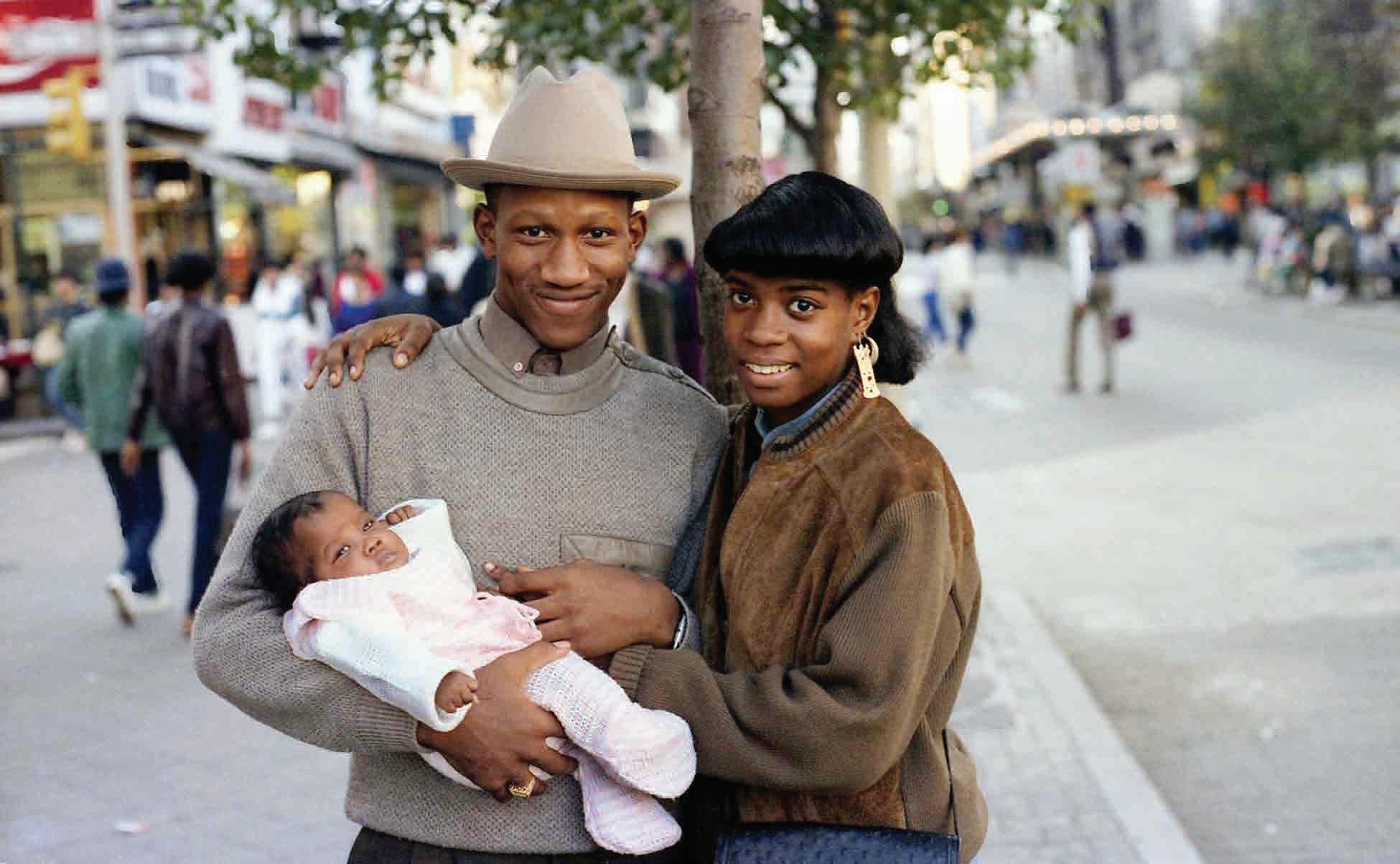

Jamel has captured all the phases of my life since boyhood. Whether riding the NYC subways to school or posted up in the epicenter of Brooklyn in the 1980s, at Albee Square Mall in downtown Brooklyn, he was there. When I began a 20-plus year career in financial services on Wall Street, he was there. Most profoundly, my stepping into fatherhood as a teen, when my daughter Ebonasia was born, Jamel was there to immortalize that family moment. That image — me cradling her, flanked by her mom, as she looked directly into Jamel’s lens — became one of his most powerful photographs, admired around the globe.

On July 25, 2024, when Ebby tragically passed away from sickle cell disease, that very image became a source of deep healing and reflection for our family. It reminded me of the love that birthed her and the light she brought into my life.

This exhibition project began two years ago. Prior to the 2024 presidential election, we had a candid conversation about how important it was for us to face an unfortunate political possibility. Our team realized that our country could possibly endure historic monumental turmoil, which would require leadership and a bold willingness to address these daunting challenges. Ergo, the exhibition’s title: Love Is THE Message and TEAM LOVE was born. Our mission is clear.

Jamel and I now share the audacity to positively impact human-to-human engagement, especially in a world that so urgently needs connection, reflection, and healing.

Jamel’s photography and presence have always been rooted in that — being present, seeing people fully, and uplifting truth.

Today, I stand as a reflection of that collaboration and a living extension of his legacy. I carry his influence with me as I pivot into a new chapter — exploring motivational speaking, leading panel discussions, and developing my political analysis to build bridges between brands, communities, and creative spaces. I am now welcoming opportunities across digital media platforms where I can bring voice, insight, and cultural fluency to conversations that matter. I am grateful for Jamel’s life-changing artistry.

By Erik Sumner, Art Teacher, Northern Parkway School, Uniondale, New York

Love Is the Message is more than an exhibition; it is a profound declaration and an urgent invitation. In these challenging times, when societal divisions often overshadow our shared humanity, this collection of photographic works by Jamel Shabazz serves as a powerful antidote. Curated with the belief that love is a fundamental human need and a potent force for healing, this exhibition aims to create a resonant space for reflection, connection, and understanding

From its inception in 2023, the vision for Love Is the Message was deeply rooted in the necessity of offering solace and hope. The exhibition intentionally interweaves love and hope for humanity into its very fabric. Each photograph by Jamel Shabazz, I believe, possesses a healing sonic frequency of 528 hertz — the “Love Frequency” — suggesting that every second spent with these compositions imparts positive energy and decreases stress 528 times over. This concept invites viewers to not only observe, but to feel the vibrations embedded within the metallic crystals of the exposed film, encouraging a deeper, more therapeutic engagement. And the vibes feel like, Boom, cha-cha, Boom, cha-cha, Boom, cha-cha!

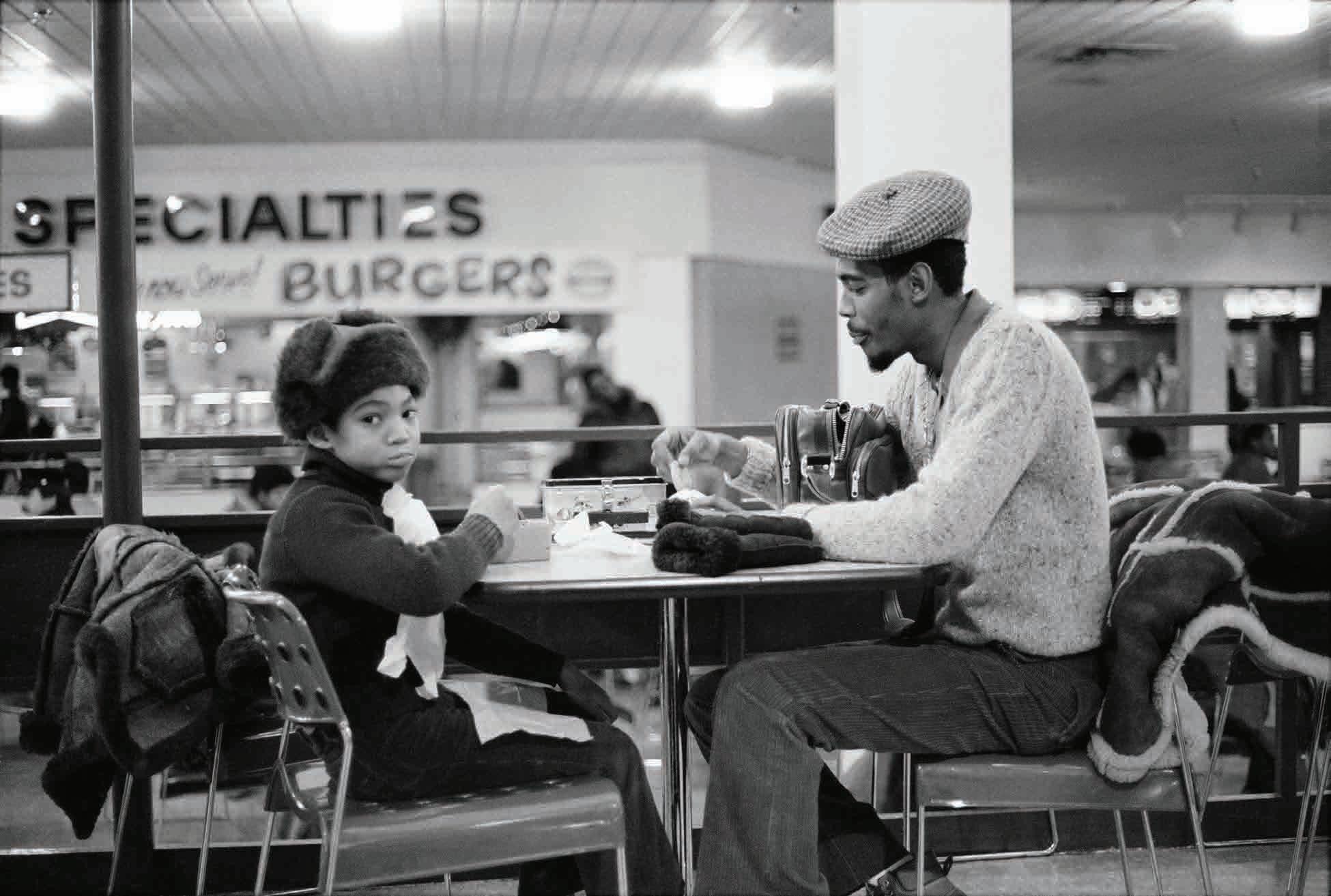

Shabazz’s work transcends mere aesthetic value; it is a form of visual literacy, mainly using “Black joy” to advocate for empathy and empowerment across all humanity. Shabazz’s piece Father & Son, Brooklyn. Downtown Brooklyn evokes universal themes of sustenance and reciprocal love, reminding us that we all broke bread with someone who helped us to know how important it is to give love and be loved in return. Simple yet profound. His photographs are echoes of ancestral voices, prophesying freedom and human dignity. They humanize “those people,” often unseen or misunderstood, boxing them in the frame not to confine, but to ensure their visibility and appreciation. Through his lens, Shabazz transforms strangers into “we the people,” dismantling prejudices and fostering a recognition of our similitude.

The 50-plus years of Mr. Shabazz’s artifacts and photographs curated in this exhibition underscore the importance of capturing and preserving images of love — self-love, platonic love, familial love, godly love — as a means to promote human compassion and unity. His innate ability to capture genuine gentleness, smiles, gazes, and embraces in fleeting moments solidifies love as a permanent fixture in time. His images are not just photographs; they are acts of activism, using joy to illuminate the inherent goodness in people. Jamel Shabazz’s lens captured the exuberant love for life in Black and Brown youth, and in doing so, revealed not just the birth of hip-hop, but the moment universal love, disguised as a cultural movement, brought the world together.

Jamel Shabazz’s Love Is the Message exhibition is a call to action for all communities that vibrate on the frequency of the Long Island Sound, from Brooklyn to the Points and everywhere in between. It aims to fortify a culture of love, acceptance, and excellence, mirroring the transformative power of hip-hop in the ’80s. Utilizing photography as a catalyst for change, empathy, and empowerment, this exhibition encourages explorations of identity and cultivates agency. It is a testament to the idea that love has to be the message if we are to realize a future of fulfilled expectations. Hofstra University, by hosting this exhibition, continues its legacy of building community and affirming that humanity, in all its diverse forms, is inherently connected by the universal language of love.

(American, born 1960)

Representing. Hempstead, NY. 2000

I Just Want to Play Ball. New York, NY. 2001

C-print

13.875 x 10.8125 inches

of the artist

Brooklyn, NY. 1980

C-print

9.75 x 14 inches

Shabazz (American, born 1960)

Youth and Age. Hempstead. Undated Archival pigment print 10.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

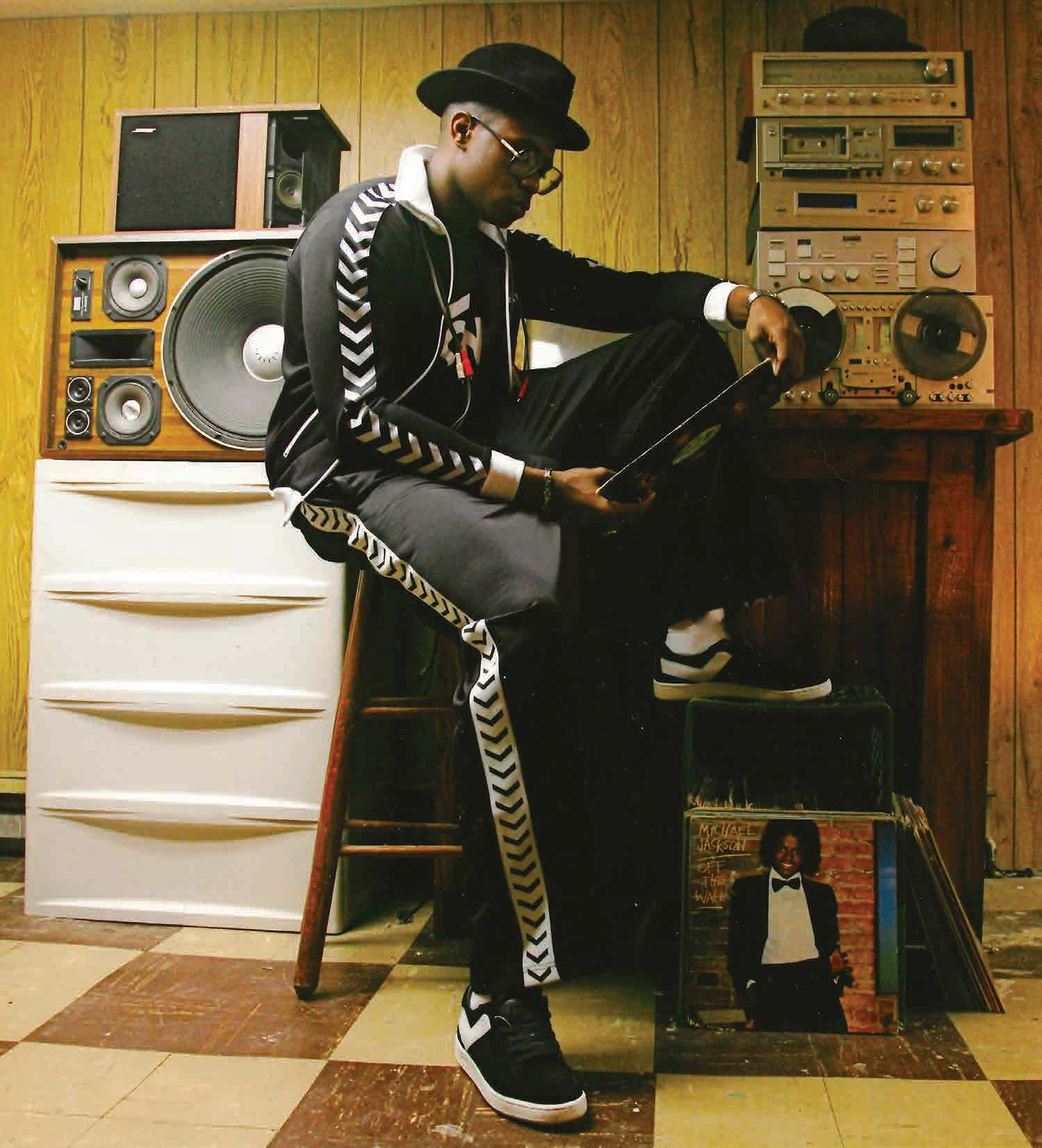

The Basement. Hempstead, NY. 2010

pigment print

29.75 x 31.75 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Terry Adkins (American, 1953-2014)

Native Son (Circus), 2006, fabricated 2015

Cymbals, armature, and additional technical components

20 x 96 x 96 inches

On loan from Art Bridges

Archibald John Motley Jr. (American, 1891-1981)

Bronzeville at Night, 1949 Oil on canvas

30 × 40 inches

On loan from Art Bridges

Jamel Shabazz (American, born 1960)

A frozen moment in time. Hempstead, NY. 2000

Gelatin silver print

19.5 x 13 inches

Courtesy of the artist

A Mother’s Love. Harlem, NY

1997

Gelatin silver print

6 x 9 inches

Courtesy of the artist

A Time of Innocence Series. East Flatbush. 1980

Gelatin silver print

10.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

A Time of Innocence Series. Flatbush, Brooklyn. 1980

Gelatin silver print

19 x 28.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

A Time of Innocence Series. Flatbush, Brooklyn. 1981

C-print

13.1875 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist

A Time of Innocence Series. Flatbush, Brooklyn. 1983

Archival pigment print

20.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Against all Odds. Annapolis, Maryland. 2016

Archival pigment print

10.75 x 13.75 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz for Cultured Magazine. 2018

Archival pigment print

11.75 x 9.25 inches

Courtesy of the artist

The Art of War. New York, NY. 1995

C-print

13 x 19.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

The Basement. Hempstead, NY. 2010

Archival pigment print

29.75 x 31.75 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Bed-Stuy, By Youth and Age. 2015

Archival pigment print

10.75 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Black in America. Crown Heights, Brooklyn. 2010

Archival pigment print

13.75 x 19.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Breezy Breakers. New York, NY. 2010

C-print

15.5 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Best Friends. Montreal, Canada. 2014

C-print

10.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Brooklyn, NY. 1980

C-print

9.75 x 14 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Brothers. Harlem, NY. Undated

Gelatin silver print

19.25 x 12.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Child’s Play. Red Hook, Brooklyn, NY 198 0

Archival pigment print

10.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Church Ladies. Harlem, NY. 1997

Archival pigment print

6 x 9 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Circle of Men. Harlem, NY. Circa 2010

C-print

14 x 19 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Cowboys and Girls. Hempstead, NY. 2010

Archival pigment print

10.25 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Cultured and Refined. New York, NY 2005

C-print

16 x 21 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Family Affair. Downtown Brooklyn 1985

C-print

12.25 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Father and Daughters. Crown Heights, Brooklyn. 1980

C-print

12.75 x 19.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Father & Son, Brooklyn. Downtown Brooklyn. 1982

Gelatin silver print

9.4375 x 14.125 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Flag of my Father. Queens, NY. 1992

C-print

12.75 x 19 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Front and Centered. New York, NY. 2002

Archival pigment print

8.5 x 13 inches

Courtesy of the artist

The Giver of Life. Jones Beach, NY 2005

Archival pigment print

10.75 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Gordon Parks. New York, NY. 1996

Gelatin silver print

9 x 12.75 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Hot Fun in the Summertime. East Flatbush, Brooklyn. 1980

C-print

9.3125 x 13.9375 inches

Courtesy of the artist

I Just Want to Play Ball. New York, NY. 20 01

C-print

13.875 x 10.8125 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Little Big Man. Harlem, New York Circa 2010

Gelatin silver print

14.75 x 19.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Looking to the Future. Hempstead Youth Parade. Undated

Archival pigment print

21.5 x 15.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Love of Family. Brooklyn, NY. 2014

Archival pigment print

13 x 19.25 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Love Me. Brooklyn, NY. 1980

Gelatin silver print

18.5 x 12.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Love Me. Harlem, NY. 2011

Archival pigment print

9 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

One Love. New York, NY. 1995

Gelatin silver print

9.4375 x 14 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Representing. Hempstead, NY. 2000

Gelatin silver print

14 x 9.6875 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Riding Partners. Brooklyn, NY. Undated

Gelatin silver print

18.5 x 13 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Rondell. Hempstead, NY. 2002

C-print

14 x 18.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Salute. Harlem, NY. 1995

Archival pigment print

13.25 x 19.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Saturday Night Live. East Flatbush, Brooklyn. 1980

Gelatin silver print

9 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

The Vietnam Generation. Undated

Archival pigment print

10.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

We Love our Youth. Harlem. Undated

Gelatin silver print

17.5 x 11.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Women of the Shinnecock Nation. East Hampton, Long Island. 2005

C-print

10 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Young and Gifted. New York, NY. 1990

Gelatin silver print

9.5 x 7.75 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Youth and Age. Hempstead. Undated

Archival pigment print

10.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Jamel Shabazz (American, born 1960)

2 Pairs of Glasses

Courtesy of the artist

2018 Gordon Parks Foundation Award 9 x 11 inches

Courtesy of the artist

2023 Lucie Foundation Award

14.75 x 3.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Black in White America, Leonard Freed

Courtesy of the artist

Gordon Parks: Voices in the Mirror, Gordon Parks

Courtesy of the artist

Hearts of Darkness, Don McCullin

Courtesy of the artist

Photo Album

Courtesy of the artist

Photographs from the artist’s portfolio

From photo books

Courtesy of the artist

Photography equipment

Courtesy of the artist

Stereo equipment

Courtesy of the artist

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY

SUSAN POSER President

CHARLES G. RIORDAN

Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

COMILA SHAHANI-DENNING Senior Vice Provost for Academic Affairs

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART

ALEXANDRA (SASHA) GIORDANO Director

TAMARA ALFANO Museum Educator

MARISA (RIS) AGUILÓ-CUADRA Museum Educator

JESSICA GALARZA Museum Educator

JACKIE GEIS

Senior Assistant to Director

STEPHANIE MCGEE Museum Educator

PRESLEY RODRIGUEZ Assistant Director of Exhibitions and Collections

AMY G. SOLOMON Director of Education

JORGE DANIEL TORRES de VENECIANO Scholar in Residence I Office of the Provost

VICTORIA UNZ Collections Manager

GRADUATE ASSISTANTS

Emily Colwell, Olivia Medford, Eddy Sanchez

GRADUATE ASSISTANTSHIP

Abigail Sullivan

UNDERGRADUATE CURATORIAL INTERN

Sarah Braun

UNDERGRADUATE ASSISTANTS

Britnee Bayas, Ellie Bell, Sarah Braun, Syd Hartstein, Rachel Jacob, Sabrina Juhasz, Katie Kim, Mick Krayn, Katie Mondry, Kyrah Mullings, Daniel Parr, Ryan Romanelli, Ayla Stendell, Gabriella Vallerugo