Using Social Stories to Increase Social

Initiations by a Student with Autism to Typical Peers

StephanieH.Valentini,Med,BCBA TheMargaretMurphyCenterforChildren

RachelE.Robertson,PhD,BCBA-D UniversityofPittsburgh

Abstract

Individuals with autism often struggle to initiate interactions with peers. Although social stories maybeaneffectivestrategyforstudents withASDtoinitiateinteractionswithpeers,fewstudies haveexaminedtheeffectivenessofsocialstorieswithouttheuseofadditionalinterventions.This studyutilizedamultiple-baseline-across-peersdesigntodemonstratetheefficacyofasocialstory for increasing social initiations of a 6-year-old male student with autism to typical peers in a general education classroom. Introduction of the social story was associated with increased initiationsacrosspeers.Additionally,peersocialvaliditydataindicatedthatsocialinitiationswere positively received and similar to those of other typical peers. Implications, including increased supportforthisinterventionforchildrenwithautism,andlimitationsarediscussed.

Keywords: Autism, Social Stories, Social Initiations, Inclusion

Using Social Stories to Increase Social Initiations by a Student with Autism to Typical Peers

Childrenwithautismspectrumdisorder(ASD)havedeficitsinsociallanguageand communicationskills,andoftenspendmoretimeplayingalonecomparedtotheirpeers (Koegel, Koegel,Frea,&Fredeen,2001;Shabanietal.,2002).Theseskilldeficitsmakeitmore challengingforchildrenwithASDtoconnectwiththeirpeersorparticipateinmeaningfulgroup activitiesintheschoolsetting(Otero,Schatz,Merrill,&Bellini,2015).Functional communicationtraining(Carr&Durand,1985),discretetrialteaching(Smith,2001),andnatural environmenttraining(Dufek&Schreibman,2014)aresomewaysofdirectlyteachingchildren withASDthecommunicationskillsnecessarytoparticipatesuccessfullyintheirenvironment. Anotherinterventionthatcanbeusedtoimprovesocialcommunicationskillsinchildrenwith ASDissocialstories(Gray,1998).Asocialstoryis"…ashortstorythatadherestoaspecific formatandguidelinestoobjectivelydescribeaperson,skill,event,concept,orsocialsituation… Thegoalofasocialstoryistosharerelevantinformation.Thisinformationoftenincludes(butis notlimitedto) where and when asituationtakesplace, who isinvolved, what isoccurring,and why”(Gray,1998,p.171).

Severalsystematicreviewshavebeenconductedontheeffectsofsocialstoriesforstudentswith ASD(Kokina&Kern,2010;Qi,Barton,Collier,Lin,&Montoya,inpress;Wongetal.,2014). Forexample,Wongetal.(2014)identified17rigoroussingle-casestudiesshowingthatsocial storiesimprovedsocialinteractionskillsinstudentswithASD.Specifically,Wongetal.found thatsocialstorieshadbeeneffectiveinaddressingsocial,communication,behavior,joint

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |37

attention,play,school-readiness,academic,andadaptiveskills.Alternatively,othersystematic reviewsusingstrictercriteriaforstudyqualityand single-caseeffectsizehavefoundsocial storiesoflowtoquestionableoveralleffectiveness,particularlywhensocialstorieswereusedas thesoleinterventionand notaspartofatreatment package(Kokina&Kern,2010;Qi,Barton, Collier, Lin,&Montoya,2018).Themajorityofpublishedstudiestestedtreatmentpackagesof socialstoriescombinedwithotherindependentvariables,suchasfeedback(Chan&O’Reilly, 2008),videomodels(Litras,Moore,&Anderson,2010;Scattone,2008),prompting,or reinforcement(Leafetal.,2012).Becauseeachoftheseadditionalcomponentsalonemaycause behaviorchange,thedegreetowhichimprovementsinbehaviorwereduetothesocialstoryas opposedtoadditionalprocedureswasunclear.Itisimportanttoexaminewhethersocialstories inabsenceofprompting, reinforcement,andotherprocedurescancausebehaviorchangeasthat maybethemannerinwhichtheyareimplementedinpractice(Kokina&Kern,2010;Schneider &Goldstein,2010).

Six studiesmeetingtherigorousqualitycriteriainQietal.(2018)examinedtheeffectivenessof socialstoriesaloneinincreasingappropriatesocialbehaviorinchildrenwithASD(Crozier& Tincani,2007;Delano&Snell,2006;Hanley-Hochdorferetal.,2010;Reichow&Sabornie, 2009;Sansosti&Powell-Smith,2006;Scattone,Tingstrom,&Wilczynski,2006).Across studies,findingsweremixedinthattenparticipantsshowedmodesttolargeeffects(Crozier& Tincani,2007;Delano&Snell,2006;Reichow&Sabornie,2009;Sansosti&Powell-Smith, 2006;Scattone,Tingstrom,&Wilczynski,2006),oneparticipantrequiredadditionalprompting toshoweffects(Crozier&Tincani,2007),andsixparticipantsshowednoeffectsofsocial storiesonincreasingsociallyappropriatebehavior(Hanley-Hochdorferetal.,2010;Sansosti& Powell-Smith,2006;Scattone,Tingstrom,&Wilczynski,2006).

Examiningcharacteristicsofparticipantswhodidanddidnotrespondtotheinterventionmay indicateforwhomsocialstoriesaloneareeffective.Acrossstudies,allparticipantswereverbal, diagnosedwithASDorAspergerSyndrome,preschooltomiddleschoolage,andhadatleast pre-readingskills.Noclearpatterninparticipantresponse-to-interventionwaspresentinthat non-respondersincludedsimilaragesandabilitylevelsasresponders;howeversomenonresponderswerehypothesizedtobelessmotivatedby,oravoidantof,peerattention(Crozier& Tincani,2007;Hanley-Hochdorferetal.,2010),whileothershadpeerswhodidnotrespondto participantattemptsatsocialinteraction(Scattoneetal.,2006)orhadsocialstoriesimplemented withpoorfidelity(Sansosti&Powell-Smith,2006).

Inadditiontounderstandingforwhomsocialstoriesalonemaybeeffective,itisalsoimportant toexaminewhethertheeffectsofsocialstoriesaremaintained,generalized,orseenassocially valid.FiveofthesixstudiesidentifiedbyQietal.(Inpress) assessedmaintenanceofeffectsby fadingthefrequencyofstoryreading(Delano&Snell,2006;Sansosti&Powell-Smith,2006), replacingthestorywithavisualcue(Reichow&Sabornie,2009),turningthestoryoverto classroomteachers(Crozier&Tincani,2007),orremovingthestoryentirely(HanleyHochdorferetal.,2010).Ofthetenparticipantsforwhomtheinterventionwaseffective,only threemaintainedeffectsatinterventionlevels(Crozier&Tincani,2007;Reichow&Sabornie, 2009;Sansosti&Powell-Smith,2006).Additionally,onlyonehadsufficientdataduring

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |38

maintenancetoanalyzetrend,level,andvariability(Reichow&Sabornie,2009).Delanoand Snell(2009)alsoassessedgeneralizationofeffectsandfoundthat,althoughnoprogrammingfor generalizationwasprovided,allparticipantsgeneralizedsocialskillstonewpeersandtwoof threeparticipantsgeneralizedskillstonewsettings.Finally,threestudiesassessedsocialvalidity oftheinterventionthroughteacherquestionnaires(Crozier&Tincani,2007;Hanley-Hochdorfer etal.,2010;Scattone,Tingstrom,&Wilczynski,2006);allteachersratedtheinterventionas generallyacceptable.

Thepurposeofthisstudywastoaddtothesmallandmixedbodyofliteratureexaminingthe effectivenessofsocialstoriesasthesoleinterventionforincreasingsocialinitiationstopeersin childrenwithASD.Additionally,thisstudysoughttoexaminethegeneralizationand maintenanceoftheeffectsofthesocialstoryaswellasthesocialvalidityofitsresults,thus addingtothemixedfindingsintheseareasaswell.

Method

Participant

TheparticipantinthisstudywasJames,asix-year-oldCaucasianboywithadiagnosisofASD. Jamesreceivedhisdiagnosisatage3fromapsychologist,whoreferredhimtoahumanservices agencywherehisdiagnosiswasreaffirmedbyamedicaldoctor.Heattendedageneraleducation kindergartenclassroomforthefulldayandreceivedspeechandoccupationaltherapytwicea week.Through academic recordsandinformalobservations,itwasdeterminedthatJameswas academicallyandverballyadvanced,withareadinglevelslightlyabovegradelevel.Although hisdiagnosismadehimeligibleforanIndividualizedEducationProgram(IEP),theschoolteam decidedhedidnotrequireitbecausehewasonorabovegradelevelinmostacademic areas. However,Jamescontinuedtodemonstratesignificantdeficitsintheuseofsociallanguageas comparedtohispeersaswellashisabilitytoparticipateinsocialgroupsandunderstandsocial norms.Healsoengagedinrepetitivebehaviorswithcars,trucks,andmarbles,anddemonstrated restrictedinterestsinthesetoys.

Jamesrarelyinitiatedsocialinteractionsduringsnack,freeplay,recess,orotherappropriate timeswithhispeers.DuringthesetimesJameswouldgenerallysitbyhimselfandplaywith marbles,cars,ortrucks.Hedidwatchotherchildren,particularlyduringsnacktime,butdidnot independentlyinitiateorsustainsocialinteraction.Whenleftoutofgamesatgymorfreeplay, Jamesrarelynoticedthathehadbeenexcluded.Ontheoccasionsthathedidnotice,hewould cry,tantrum,androllonthefloor.James’peersrarelysociallyinitiatedtohim.Ingeneralhis peersdidnotsharemanyofhisinterestsandiftheydidinitiatetohim,hetypicallyrespondedby lookingatthemandsmiling,andtheywalkedaway. Basedonhiswatchingandsmilingatpeers, andfrustrationwhendidrealizehehadbeenexcludedfromtheirplay,itwashypothesizedthat Jameswasinterestedinpeerattentionandwantedtobeapartoftheinteractionsheobserved. Jamesdidnotappeartohaveanyfriendshipsintheclassroom.

Asaresultoftheseissues,sociallyinitiatingtopeerswas agoalidentifiedinhiswraparound servicetreatmentplan.Awraparoundserviceparaprofessional(thefirstauthor)visitedhimin

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |39

schooltoworkonthisandothertreatmentplangoals.AlthoughJamesrarelyinitiatedtopeers, hefrequentlysharedtoyswiththeparaprofessional,askedherquestions,andtriedtoplaywith her.TheclassroomteacherreportedthatJames’peersinteractedwithhimmorewhenhis paraprofessionalwaspresentlikelyduetotheirinterestinher.Theparaprofessional’sprimary previousinterventiontoincreaseJames’socialinitiationstopeerswastocontrivesituationsin whichhemightbemorelikelytosociallyinitiateandverballyprompthim todoso.For example,whileJameswasplayingwithcars,shemightgiveacartoatypicalpeerandverbally promptJamestoaskthepeerifhelikescarsorwantedtoplaycars.Jamestypicallyrefusedor ignoredtheseprompts.Shealsotriedmodelingpeerinteractionsforhimwhileattemptingtofade adultsupport.Thesestrategieshadnotbeensuccessful.

Setting

Thegeneraleducationclassroomcontained21studentsandonetothreeadults(teacher, paraprofessional,andteachingassistant).ThestudywasconductedbyJames’one-on-one wraparoundparaprofessionalinhisgeneraleducationclassroom,whichiswherethe paraprofessionalregularlysupportedhim.TheparaprofessionalwasaCaucasianfemalewithtwo years’experienceworkingwithchildrenwithASD,abachelor’sdegreeininternationalrelations, andwasattendingamaster’sprograminAppliedBehaviorAnalysisatthetimeofthestudy.The threetypicalpeerstargetedinthestudywerechosenbytheparaprofessional.Allthreepeers weretypicallydevelopingkindergartenstudents,ages5to6 yearsoldatthetimeofthestudy, andwereobservedengagingintypicalsocialinteractionsandplaywithotherpeers.Peers1and 3were female;peer2wasmale.Thesepeershadbeenobservedinteractingpositivelywith Jamesonoccasionbutgenerallydidnotgooutoftheirwaytoincludeorexcludehimintheir play.AllthreepeersverballyindicatedthattheylikedtotalktoJames,thoughtheyrarelydidso atthebeginningofthestudy.Theparaprofessionalprovidednotraining,prompting,or reinforcementtopeersforsocialinteractions.

Thestudysessionstookplaceonceperdayduring15-minsnacktime,fourdaysperweek.The socialstorywasreadinanareawithintheclassroomawayfrompeers.Distractingstimuliwere removedfromthisarea.Duringsnacktime,studentswereencouragedtoconversewitheach otherandwereseatedaroundasquaretablewiththreetofivestudentspertable.Thetableswere ina“U”shapeandJames’tablewasinthecenteroftheroom.Twoofhisclassmatessatatthe sametable,andoneoftheseclassmateswasselectedasapeerforthestudy.Theothertwopeers satatanadjoiningtable.Theparticipantwasabletointeractwithallthree peerseasilywhile remaininginhisseat.

Materials

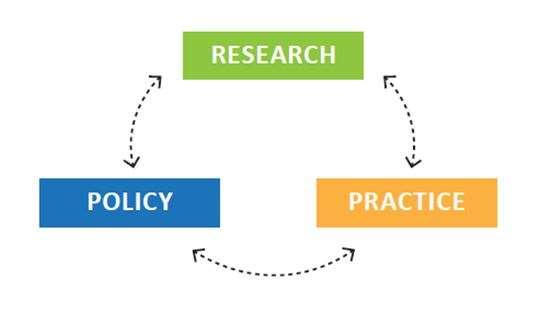

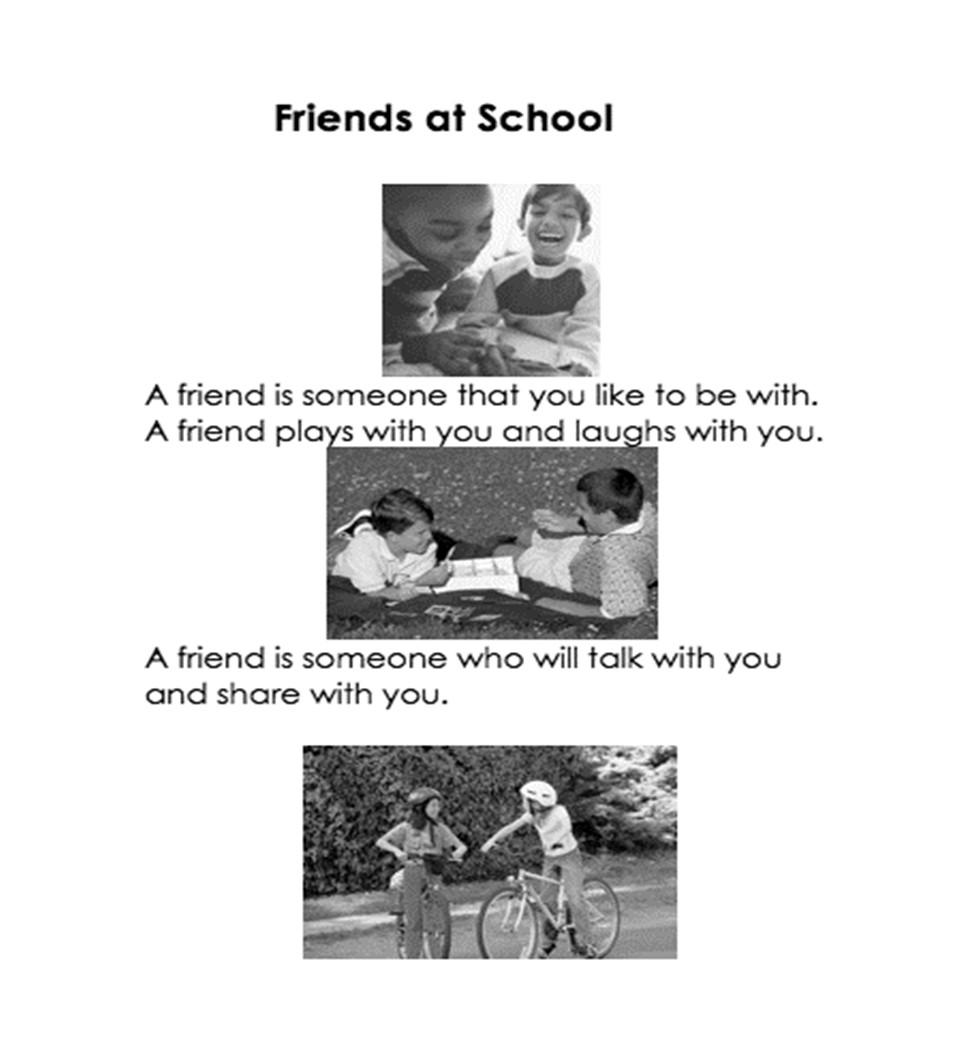

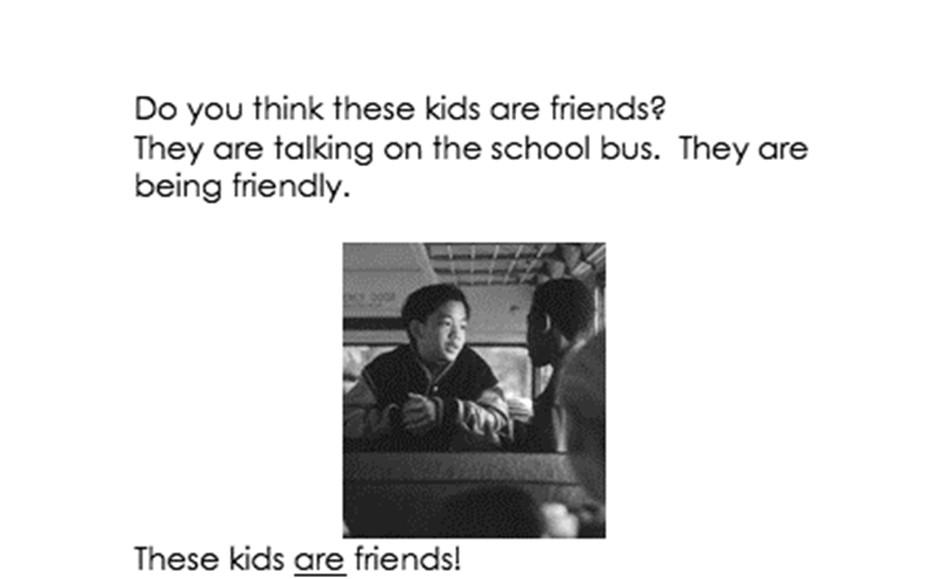

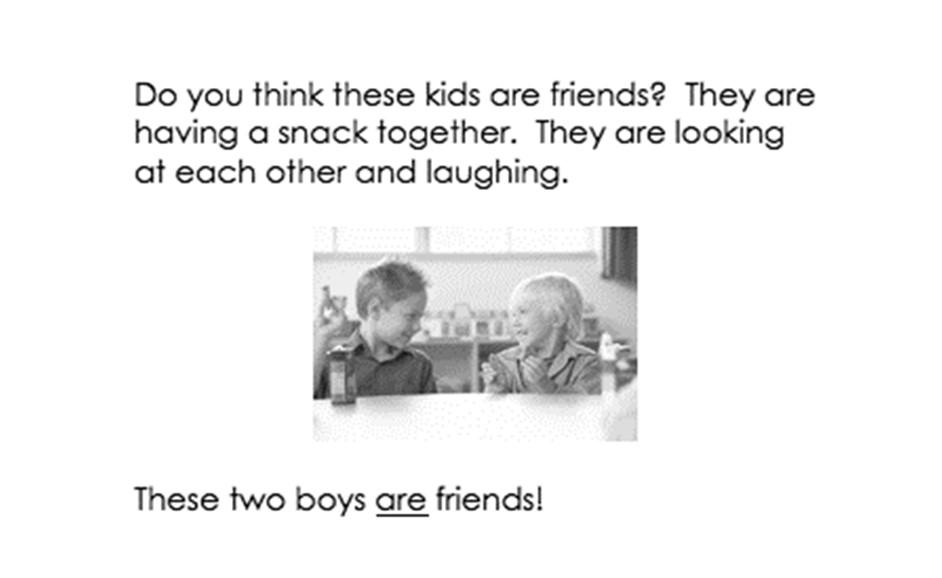

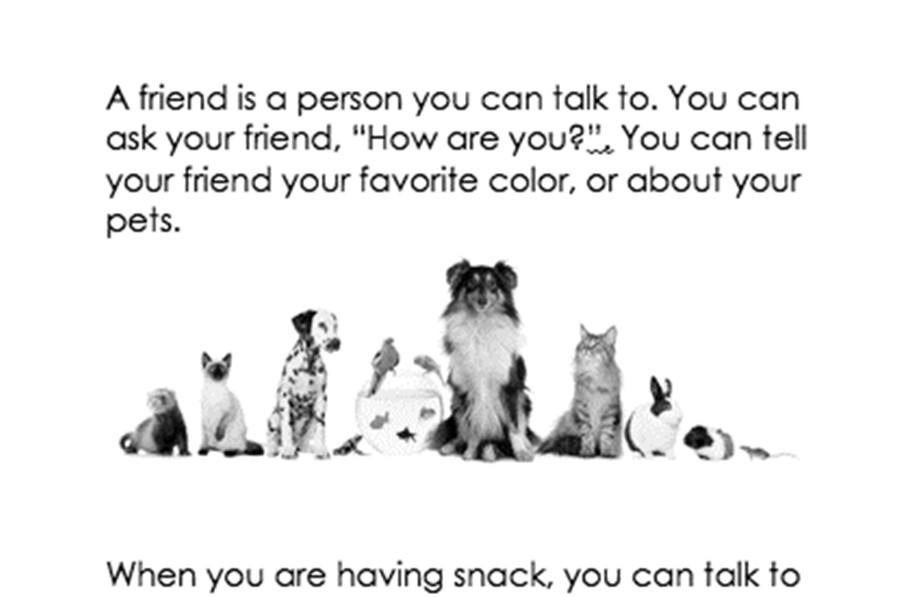

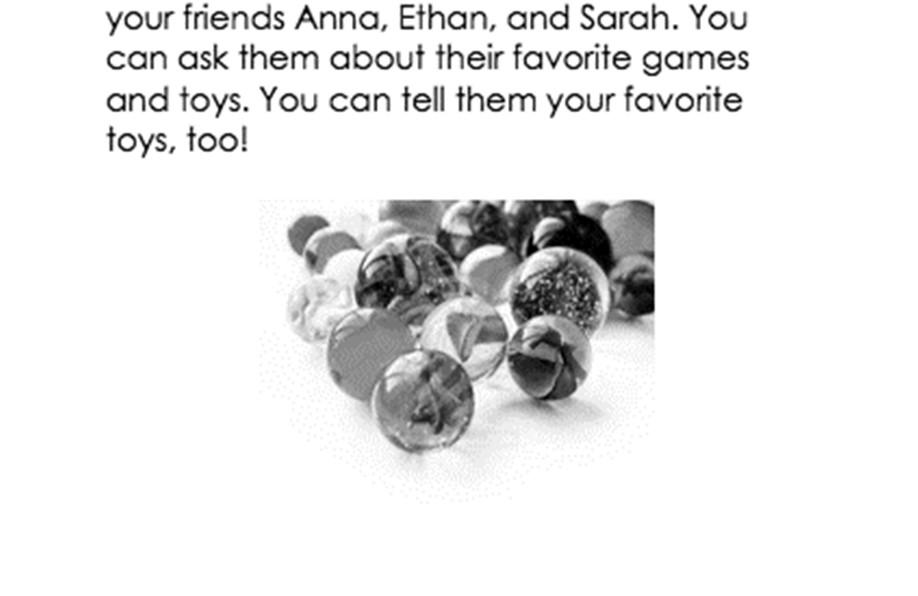

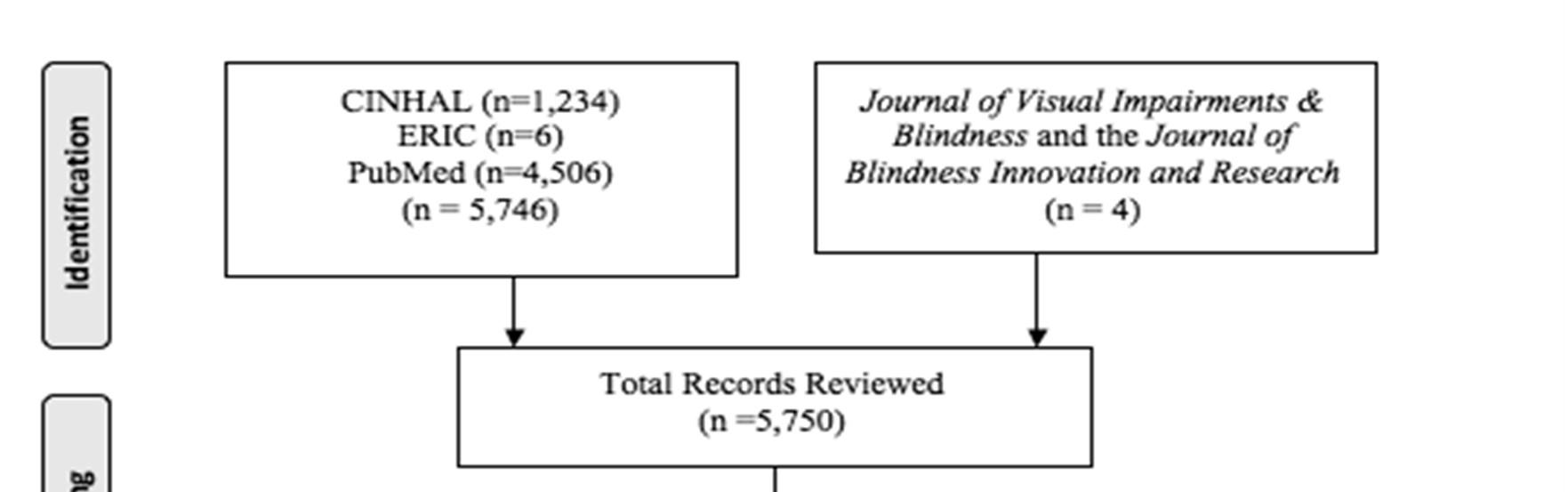

Socialstory.Thesocialstory(seeFigure1)wasfourpageslong,createdbythe paraprofessional,andsuggestedtopicsforsocialinitiationstopeers,suchaspets,favoritecolors, games,andtoys.Thetopicswerechosenbasedontheparaprofessional’sdirectobservationsof typicalpeers’conversationsintheclassroom.Noidentifyinginformationorinformationspecific tothepeerswasincludedinthestory.Althoughphotographsanddrawingswereutilizedinthe story,theyweregenericrepresentationsofitemsintheclassroomandfriends.Noactual

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |40

photographsofpeersorclassroomitemswereused.Theinitialsocialstoryidentifiedonlypeer1 asapeerwithwhomJamescouldinteract.Whenpeer2wasaddedasatargetpeer,thatpeer’s namewasaddedtothesocialstory.Thesamemodificationwasmadewhenpeer3wasaddedto theinterventionsuchthatallthreepeers’nameswereinthefinalversionofthestory;otherwise thesocialstorywasthesamethroughoutthestudy.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |41

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |42 Page1 Page2 Page3 Page4

Figure1. Social story text and images.

Socialvalidityquestionnaires.Socialvalidityquestionnairesweredevelopedbythe paraprofessionaland administeredtothetargetpeersandclassroomteacherattheconclusionof datacollection.Thepurposeofthepeersocialvalidityquestionnairewasto examinethesocial significanceofJames’initiationsandimportanceoftheeffectsoftheinterventionwithhistarget peers.Thepeersocialvalidityquestionnairewasreadbytheparaprofessionaltothetargetpeers andincludedthefollowingquestions:Do youliketalkingtoJames?WhatdoyouandJamestalk about?Whatdoyoutalk aboutwith yourotherfriends?Whoaresomeof yourfriendsinthe classroom? Theparaprofessionalrecordedeachpeer’sresponsetoeachquestion.Thepurposeof theteachersocialvalidityquestionnairewasto gaintheteacher’sperspectiveonthesignificance ofthegoals,acceptabilityoftheprocedures,andimportanceoftheresults.Theteacher’s questionnaireincludedthefollowingitems,whichsheratedfrom1(stronglydisagree)to5 (stronglyagree):Theinterventionfocusedonanimportantbehavior;Theinterventionproduced effectiveresults;Theinterventionwasnotintrusivetotheclassroom;Theinterventionrequireda reasonableamountoftime;Theinterventionproducedapositivechangein behavior.

DependentVariables

TheprimarydependentvariablewasthenumberofappropriatesocialinitiationsmadebyJames towardthethreetargetpeersabouttopicssuggestedinthesocialstory.Anappropriatesocial initiationwasdefinedasaverbalinitiationtoapeer,unpromptedbyadult orotherpeer,which wasage-appropriateandallowedforpeerresponse.Initiationswerenotindirectresponsetoa peerquestionorstatementthatoccurredinthepreceding10s.Aninitiationwasconsideredtobe anythingfromasinglewordtoagroupofphrasesorsentences.Anewinitiationwasrecorded whenJamesspoketoapeerafternotspeakingforatleast10sorchangedthepersontowhomhe wasspeaking.Additionally,thephrases,“Hello,”“Hi,”and“Howare you?”werespecific initiationsdescribedinthesocialstoryandthereforeconsideredtargetedsocialinitiations.Other examplesoftargetedsocialinitiationsincludedaskingapeer’sfavoritecolor,game,ortoy,and askingaboutapeer’spet.Non-examplesoftargetedsocialinitiationsincludedgestural initiationssuchaswaves,socialinitiationstoadults,correctionofpeers’speech,andstatements notdescribedinthesocialstory(thosewereconsidered generalizedinitiations,describedbelow). Thedependentvariablewasmeasuredasthefrequencyoftargetedsocialinitiationsmadeby Jamestoapeerduringthe15minsnacktime.Therefore,eachsessionproducedJames’ frequencyoftargetedsocialinitiationsper15min.

AsecondarydependentvariablewasthenumberofappropriatesocialinitiationsfromJamesto thethreetargetpeersabouttopicsnotincludedinthesocialstory.Examplesofgeneralizedsocial initiationsincluded,“Did youhaveagoodEaster?”“Isit yourbirthday?”or“Youhaveblond hair.”Theseinitiationswerenottaughtinthestory,butwereutteredbytheparticipantto targetedpeersduringdatacollectionsessions.Non-examplesincludedstatementsunlikelyto gainpeerresponse,suchas“Iameating”orvocalstereotypy.Generalizedsocialinitiationswere measuredasthefrequencyofgeneralizedinitiationsmadebyJamestothethreetargetpeers duringsnacktime,producingafrequencyof generalizedsocialinitiationsper15min.Each generalizedsocialinitiationwastranscribedverbatimbytheparaprofessional.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |43

ExperimentalDesign,Reliability,andTreatmentIntegrity

Amultiplebaselineacrosspeersdesignwasusedforthisstudy.Themultiplebaselinedesign wasconductedacrossthreepreselectedpeerswhosatincloseproximitytoJames. Inter-observer agreement(IOA)wascollectedbytheparaprofessionalandaUniversitySupervisorfor31%of sessions.TheparaprofessionalandUniversitySupervisorcollectedIOAduringeachphaseofthe study. IOAwascollectedontheaggregatenumberoftargetedandgeneralizedinitiations.IOA wascalculatedafterthesessionbytakingthesmallernumberofrecordedsocialinitiationsby utteranceanddividingbythelargernumberofrecordedsocialinitiations,thenmultiplyingby 100. Themean IOAwas 92.4%across allsessions(range,87%-100%).Toensurethatthe interventionwasimplementedeffectivelyandconsistently,atreatmentintegrityformasutilized asafidelitycheckonceperinterventionphase.Thistreatmentintegrityformwasfilledoutby theinvestigatorandtheUniversitySupervisorduringorimmediatelyfollowingthereadingof thesocialstory.Treatmentintegritywas calculatedasthepercentageofstepsimplemented correctly.Treatmentintegritywascompletedfor13%ofsessionswithameanof97%(range, 92%-100%).

Procedures

Baseline.Baselinesessionswereconductedduring15minsnackperiodsinJames’general educationclassroom.Throughoutallsessions,targetedpeersremainedinclosephysical proximitytoJames(eitherathistableortheadjoiningtable)andavailableforinitiations.During baseline,Jameswasnotgivenaccesstothesocialstory,promptedtointeract,orprovidedwith anyreinforcement(e.g.,edible,praise)contingentuponanysocialinitiations.Jameswasfreeto interactwithpeersashenormallywould.Peerswerenotpromptedbytheparaprofessionalto initiateorrespondtotheparticipant.

Intervention.TheparaprofessionalverballydirectedJamestogotoasemi-privateareainthe classroomeachday.TheparaprofessionalthenreadthesocialstorytoJamesimmediatelyprior tosnacktime.Duringthereading,theparaprofessionalreadeverywordaloud,gaveJamestime toaskquestionsduringandafterthestory,androle-playedtargetedsocialinitiations.A comprehensioncheckwasperformedverybrieflyandinformallybyaskingJames,“Whatcan youtalkaboutwith yourfriends?”andJameswouldrepeatwhathehadreadinthestory.The roleplayswerebrief(lessthan3min),occurredonceperreadingofthesocialstory,and consistedoftheparaprofessionalassumingtheroleofthepeerduringasnacktime.IfJames usedanincorrectinitiationduringtheroleplay,theparaprofessionalprovidedhimwithan appropriatestatementinstead.Jamesreceivednocontrivedreinforcement,prompting,or instructionsonhowtoinitiatetopeersoutsideofthecontentofthesocialstory.AfterJamesand theparaprofessionalfinishedreadingthestory,Jamestransitionedtothe15-minsnackperiod withhispeersduringwhichhissocialinitiationswererecorded.The15-minsnackperiodbegan whenJamesjoinedhispeers.

Interventionfading.Aninterventionfadingperiodfollowedtheinterventionphasetoexamine whethereffectsofthesocialstorywouldmaintaininabsenceoftheparaprofessionalreadingthe storytoJames.Thefirstfadingphasebeganthreeschooldaysaftertheterminationofthe

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE

|44

Page

interventionphase. InFading1,thesocialstorywasremoved.IfJamesdidnotinitiatetopeers, theparaprofessionaldid notinterveneandhewasnotprovidedthesocialstory. InFading2, Jameswasprovidedphysicalaccesstothesocialstorybutitwasnotreadtohimandhewasnot promptedtoinitiatetohispeers.

Results

Figure2displaysthenumberoftargetedandgeneralizedsocialinitiationsmadebyJamesto threepre-selectedpeersduringsnacktimepersession.Visualanalysisofthedataindicatesa functionalrelationbetweenthesocialstoryandincreasesintargetedandgeneralizedsocial initiations.Duringbaseline,Jamesmadetwosocialinitiationstopeer3acrossallbaseline sessionsandallpeers.Afterthesocialstorywasinitiallyintroducedwithpeer1’sname,there wasadelayedincreaseinsocialinitiationstopeer1.Initiationstopeer2andpeer3immediately increasedaftereachwasaddedtothesocialstory.Furthermore,Jamesincreasedgeneralized socialinitiationsontopicsnotcoveredinthesocialstorytoallthreepeersonlyaftertheirnames were addedtothesocialstory.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |45

Note. Triangulardatapointsindicateinitiationstopeersthatweregeneralizedfromthetopics coveredinthesocialstory.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |46

Figure2. Number of social initiations by James across peers for baseline, social story, Fading 1, and Fading 2 conditions

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132 Baseline SocialStory F1Fading2 Sessions Frequency of Targeted and Generalized Initiations to Peers During Snack Peer1 Peer2 Peer3

Duringbaseline,Jamesdidnotmaketargetedsocialinitiationstopeer1.Aftertheintroduction ofthesocialstorydirectingJamestosociallyinitiatetopeer1,heshowedadelayedresponseto theinterventionandbegantomaketargetedsocialinitiationstopeer1inthefifthintervention session.Hisinitiationstopeer1steadilyincreased,reachingamaximumof8initiationsin session22.Duringintervention,heaveraged2.72socialinitiationstopeer1,rangingfromzero toeightpersession.Forthelastfiveinterventionsessions,James’socialinitiationstopeer1 rangedfrom4to6persession.Jamesdidnotmaketargetedsocialinitiationstopeer2during baseline.Uponreadingthestorywithpeer2’snameaddedtothetext,Jamesimmediatelybegan sociallyinitiatingtopeer2withtwotargetedsocialinitiationsinthefirstsessionofintervention. Duringintervention,James’initiationstopeer2rangedfrom1to6,withanaverageof4 initiationspersession.Forthelastseveninterventionsessions,James’socialinitiationstopeer2 rangedfrom4to6persession.Duringbaseline,Jamesmadetargetedsocialinitiationstopeer3 onceinsession4andonceinsession5,saying“Hello”eachtime.Uponreadingthestorywith peer3’snameaddedtothetext,JamesimmediatelybegantargetedsocialinitiationstoPeer3 with5initiationsinthefirstsession.Initiationstopeer3remainedstable,with5to6initiations persessionandaninterventionaverageof5.2.Importantly,asJamesbegantoinitiatetopeer2, hecontinuedhisinitiationstopeer1,thusincreasinghistotalnumberofinitiationsacrosspeers. Similarly,ashebeganinitiatingtopeer3,hecontinuedinitiatingtopeers1and2.

Duringbaseline,Jamesmadenogeneralizedsocialinitiationstopeer1.Duringsession22ofthe socialstoryintervention,Jamesmade3generalizedinitiationstopeer1.Hisgeneralized initiationsincludedaskingpeer1aboutherweekend,favoriteplacetoplay,andabouther mother.Thissessionwastheonlysessionwithgeneralizedsocialinitiationstopeer1duringthe interventionphase.Jamesmadenogeneralizedsocialinitiationstopeer2duringbaseline.After fourdaysofthesocialstoryinterventiontargetingpeer2,Jamesmadegeneralizedsocial initiationstohimduringthenextfourconsecutiveinterventionsessions.SpecificallyJames madeonegeneralizedsocialinitiationtopeer2insession21,twoinsession22,andoneeachin sessions23and24,averaging1.25generalizedinitiationsduringthesesessions.Thegeneralized initiationstopeer2includedinvitationstoengageinpretendplaywithsnackfood,questions abouthishair,andstatementssuchas“(peer2),youaremyfriend.” Duringbaseline,Jamesdid notmakeanygeneralizedsocialinitiationstopeer3.Ontheseconddayofthesocialstory interventionwithpeer3(session24),Jamesmadeonegeneralizedsocialinitiationtoher.James madeanothergeneralizedinitiationtopeer3duringsession26andanotherinsession27.These initiationsincludedquestionsaboutherstickersandcrayonsinherdesk.

Afadingperiodfollowedtheinterventionphases.DuringFading1thesocialstorywasnotread toJamesorphysicallypresent.James’socialinitiationsimmediatelydecreasedtozerotoall peers.Aftertwosessionswithzeroinitiations,thefadingphasewasmodified(Fading2)andthe socialstorywasphysicallyprovidedtoJames.Theparaprofessionaldidnotreadthestory, promptJamestoreadthestory,orprompthimtoinitiatetopeers.James’targetedsocial initiationsimmediatelyincreasedtoallthreepeers,with1to2initiationsinthefirstFading2 session.Targetedsocialinitiationscontinuedtoincreaseinthisconditionandreturnedto interventionlevelswithpeer1andwereslightlybelowfinalinterventionlevelsforpeers2and3 afterthethirdsessionofFading2.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |47

JamesmadenogeneralizedsocialinitiationstoanypeersduringFading1.Afterintroductionof Fading2andphysicalaccesstothesocialstory,Jamesimmediatelyincreasedgeneralizedsocial initiationswith1topeer1and1topeer3inthefirstsessionofFading2.Inthesecondsession Jamesmadeanothergeneralizedinitiationtopeer1,andinthethirdsessionhemade2 generalizedinitiationstopeer1andonetopeer3.Nogeneralizedsocialinitiationsweremadeto peer2duringfadingphases.

Peers1,2,and3statedonthesocialvalidityquestionnairethattheyenjoyedspeakingwith James.Inresponsetothequestion,“WhatdoyounormallytalkaboutwithJames?”,thepeers listedfavoritecolors,games,toys,pets,and“newthings.”Inthefollow-upquestionof“Whatdo younormallytalkaboutwithyourotherfriends?”, thepeersstatedthattheydiscussedcolors, games,toys,movies,and thepark;indicatingthattheydiscussedmanyofthesametopicswith Jamesastheydidwiththeirtypicalpeers.Thepeerswerealsoaskedtolisttheirfriendsasaway toexaminewhetherJames’increasedininitiationshadanyeffectonpeers’perceptionsofJames asafriend.Whenaskedtonamesomeoftheirfriendsintheclassroom,peer1listedJamesinthe firstfivefriendsmentioned;peer2listedJamesfirst;andpeer3didnotlisthim.

Theteacherstronglyagreedthattheinterventionwasnotintrusivetotheclassroomandfocused onanimportantbehavior.Sheagreedthatitproducedeffectiveresultsandmadeapositive changeinbehavior.Althoughtheteacherdidnotimplementtheintervention,basedonher observationsshestronglyagreedthattheinterventiontookareasonableamountoftimeto implementandwasnotoverlytime-consuming.

Discussion

Previousresearchhasshownmixedsupportforusingsocialstoryinterventionsalonetoimprove socialinitiationsinchildrenwithASD.Inparticular,ReichowandSabornie(2009)foundsocial storieseffectiveinincreasingsocialinitiationstopeerswhileHanley-Hochdorferetal.(2010) didnot.Thepresentstudyaimedtoaddtotheresearchinthisareabyinvestigatingwhethera socialstorywithoutpromptingandreinforcementwouldincreasesocialinitiationstopeersina childwithASDandwhethertheseinitiationswouldmaintain,generalize,andbeconsidered sociallyvalid.

Theresultsofthisstudyindicatethatthesocialstorywassuccessfulinincreasingthe participant’ssocialinitiationstotypicalpeers.Eachtimethesocialstorywasamendedtodirect Jamestosociallyinitiatetoanewpeer,hissocialinitiationstothatpeerincreased.James consistentlyinitiatedtopeersthroughouttheinterventionphase,andhispeersrespondedtohis initiations.Althoughtherewasadelayedresponsetotheinterventionwithpeer1,responsesto theinterventionwithpeers2and3wereimmediate.Furthermore,aseachnewpeerwasaddedto thesocialstory,Jamesnotonlyincreasedinitiationstothatpeerbutcontinuedinitiationstopeers alreadyappearinginthestory.

Duringeachreadingofthesocialstory,Jameswouldreadalongwiththeinvestigator,and,by theend,couldrecitethestoryfrommemory.Duringthefirstfadingphasein whichthesocial

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |48

storywasnotpresent,Jamesrequestedthestoryeachday.Whenitwasnotpresented,herecited itfrommemoryanddescribedthepicturestohimself.However,hedidnot initiatetopeers, althoughhedidaskifheshould.Whenthestorywasprovidedthoughnotreadtohiminthe secondfadingphase,heresumedsociallyinitiatingtopeers.Thispatternofrespondingsuggests thatthephysicalpresenceofthesocialstorymayhavebecomeadiscriminativestimulusfor James’socialinitiations,astheparaprofessional’sbehaviorremainedconsistentacrossthefirst andsecondfadingphasesandtheonlydifferenceinthesecondfadingphasewasthephysical presenceofthesocialstory.James’dependenceonthepresenceofandpre-sessionexposureto thesocialstoryspeaksto thechallengesofgeneralizationfortheASDpopulation,evenin childrenwithhigh-functioningASD,andtheneedforexplicitinstructionandplanned generalizationofsocialbehaviors.

Interestingly,James’lackofsocialinitiationsduringFading1resembledthefindingsof ReichowandSabornie (2009).ReichowandSabornieusedasingle-casewithdrawaldesignand afterlargegainsinsocialinitiationsduringthefirstsocialstoryinterventionphase,withdrawal ofthesocialstoryinthereturntobaselineconditionresultedinzerosocialinitiationsthroughout thecondition.Forthisreason,ReichowandSaborniedecidedtouseavisualcueremindingthe participantofstorycontentinthefinalmaintenancephase,whichwaseffective.Itispossible thatsocialstoryinterventionsrequiresomeremainingstimulustomaintainovertime;itwould bevaluableforfutureresearchto furtherinvestigateprocedurestomaintainsocialinitiations afterthesocialstoryhasbeenremovedorfaded.

WhileJamesinitiallymadeonlytargetedsocialinitiationsbasedontopicsinthesocialstory, overtimeheproducedgeneralizedsocialinitiationsontopicsnotfoundinthestory.During theseinitiationsheaskedhispeersabouttheirfavoriteTVshows,movies,andthesnackthey were eating.Ononeoccasion,heengagedincooperativeandimaginativeplaywithpeer2,using thepretzelsticksthatwereforsnackthatday.Itis notclearwhatcausedthisspontaneous generalizationtonewsocialtopics;however,previousresearchhasidentifiedsocialinitiationsas apivotal,orcusp,behaviorinthattheacquisitionofsocialinitiationscontactsnatural contingenciesintheenvironmentleadingtothegenerationoffurthersocialcommunicationskills (Bosch&Fuqua,2001;Koegel,Carter,&Koegel,2003).InJames’case,thesocialstorymay havegivenhimaninitialscripttobeginsocialinitiationsandcontactcontingenciesofpeer reinforcement.Atthispoint,observingpeers’interactionsonothertopicsmayhaveledtohis acquisitionofgeneralizedsocialinitiations.

Onepotentiallimitationtothecurrentstudywastheconsistencyofthesocialstory.Whenthe storywasamendedforpeers2and3,theirnameswereaddedbutthetopicscoveredinthestory remainedthesame.Whileusefulfromaresearchdesignstandpoint,theconsistencyofthescript likelynarrowedthecontentofJames’socialinitiations.Jamesfrequentlyaskedpeer1thesame twoquestions(alongsideotherquestions)duringeachsession.Ifthesocialstoryhadbeen changedmoreforeachpeer,Jamesmighthavebeenabletomasteragreatervarietyofinitiations topeers.Ofnote,Jamesonlyinitiatedtopeersnamedinthestoryandneverinitiatedtoanyof theotherpeersinhisclass.Thisfindingmayreveallimitationsofthistypeofsocialstoryfor

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |49

practice; astorywithmorebroadsuggestionsonmakingsocialinitiationstoallpeersmaybe moreusefulinpractice.Overall,thesocialstorytestedinthepresentstudydidnotinclude programmingforgeneralization,whichisalimitationandrecommendedinfutureresearchand practiceinthisarea.Additionallimitationsincludethefocusonone,uniquestudentwithhigh functioningASDwhichnecessarilylimitsgeneralizationoffindings.Futurestudiesshould considermultiplebaselinedesignstoexaminetheeffectsofsocialstoriesonsocialinitiationsin multiplestudentswithASD.

Overall,thefindingsofthisstudysuggestthatasocialstoryusedwithoutpromptingor reinforcementwaseffectiveinincreasingsocialinitiationstotypicalpeersinone6-year-old participantwithhigh-functioningASD.ThisstudyaddstoReichowandSabornie(2009)as researchsupportingtheuseofasocialstorywithoutreinforcementorpromptingtoincrease socialinitiationsinsomechildrenwithASD.Futureresearchshouldcontinuetoinvestigatefor whomsocialstoriesareeffectiveforincreasingsocialinitiationsandothersocialcommunication skills.Forexample,Jameswashypothesizedtobehighlymotivatedbypeerattentionwhichmay havebeenacontributingfactortotheintervention’ssuccess.Futurestudiesshouldattemptto implementsocialstoriesalonewithmultiplestudentswithASDtofurtherexamine generalizabilityandmaintenanceoftheresultsandprovidemoreinformationonthepopulation forwhomthisfeasibleinterventioniseffective.

References

AmericanPsychiatricAssociation.(2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5thed.).Arlington,VA: AmericanPsychiatricPublishing.

BoschS.,FuquaR.(2001).Behavioralcusps:Amodelforselectingtargetbehaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34,123-125.

Carr,E.G.,&Durand,V.M.(1985).Reducingbehaviorproblemsthroughfunctional communicationtraining. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18,111-126.

CentersforDiseaseControlandPrevention.(2014).Prevalenceofautismspectrumdisorders amongchildrenaged8 years—Autismanddevelopmentaldisabilitiesmonitoring network,11sites,UnitedStates,2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63,1–22. Retrievedfromhttp://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/ss/ss6302.pdf

Chan,J.M.,&O'Reilly,M.F.(2008).ASocialStories™interventionpackageforstudentswith autismininclusiveclassroomsettings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41,405409.

Crozier,S.,&Tincani,M.(2007).Effectsofsocialstoriesonprosocialbehaviorofpreschool childrenwithautismspectrumdisorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37,1803-1814.

Delano,M.,&Snell,M.E.(2006).Theeffectsofsocialstoriesonthesocialengagement of childrenwithautism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8,29-42.

Dufek,S.,&Schreibman,L.(2014).Naturalenvironmenttraining.In Handbook of Early Intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorders (pp.255-269).NewYork:Springer.

Gray,C.(1998).SocialStoriesandcomicstripconversationswithstudentswithAsperger syndromeandhigh-functioningautism.InE.Schopler,G.B.Mesibov,&L.J.Kunce

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |50

(Eds.), Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism? (pp.167-198).NewYork: Plenum.

Gray,C.A.,&Garand,J.D.(1993).SocialStories:Improvingresponsesofstudentswithautism withaccuratesocialinformation. Focus on Autistic Behavior, 8,1-10.

Hanley-Hochdorfer,K.,Bray,M.,Kehle,T.,&Elinoff,M.(2010).Socialstoriestoincrease verbalinitiationinchildrenwithautismandasperger’sdisorder. School Psychology Review, 39, 484-492.

Ivey,M.L.,Heflin,L.J.,&Alberto,P.(2004).TheuseofSocialStoriestopromoteindependent behaviorsinnoveleventsforchildrenwithPDD-NOS. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19,164-176.

Kennedy,C.H.(2005). Single-case designs for educational research.PrenticeHall.

Koegel,R.,Bradshaw,J.,Ashbaugh,K.,&Koegel,K.(2014).Improvingquestionasking initiationsinyoungchildrenwithautismusingpivotalresponsetreatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44,816–827.

Koegel,L.K.,Carter,C.M.,&Koegel,R. L.(2003).Teachingchildrenwithautismselfinitiationsasapivotalresponse. Topics in Language Disorders, 23,134-145.

Koegel,L.K.,Koegel,R.L.,Frea,W.D.,&Fredeen,R.M.(2001).Identifyingearly interventiontargetsforchildrenwithautismininclusiveschoolsettings. Behavior modification, 25,745-761.

Kokina,A.&Kern,L.(2010).Socialstory™interventionsforstudentswithautismspectrum disorders:Ameta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40,812826.

Leaf,J.B.,Oppenheim‐Leaf,M.L.,Call,N.A.,Sheldon,J.B.,Sherman,J.A.,Taubman,M.,... &Leaf,R.(2012).Comparingtheteachinginteractionproceduretosocialstoriesfor peoplewithautism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45,281-298.

Litras,S.,Moore,D.W.,&Anderson,A.(2010).Usingvideoself-modelledsocialstoriesto teachsocialskillstoa youngchildwithautism. Autism Research and Treatment, 2010, 19.

Otero,T.L.,Schatz,R.B.,Merrill,A.C.,&Bellini,S.(2015).Socialskillstrainingforyouth withautismspectrumdisorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 24(1),99-115.

Qi,H.,Barton,E.,Collier,M.,Lin,Y.,&Montoya,C.(2018).Asystematicreviewofeffectsof socialstoriesinterventionsforindividualswithautismspectrumdisorder. Focus on Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 33,25-34.

Reichow,B.&Sabornie,E.(2009).Briefreport:increasingverbalgreetinginitiationswith autismviaasocialstoryintervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39,1740-1743.

Sansosti,F&Powell-Smith,K.(2006).Usingsocialstoriestoimprovethesocial behaviorof childrenwithAspergersyndrome. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8, 43-57.

Scattone,D.,Tingstrom,D.,&Wilczynski,S.(2006).Increasingappropriatesocialinteractions ofchildrenwithautismspectrumdisordersusingsocialstories™. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21, 211-222.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |51

Schneider,N.,&Goldstein,H.(2010).Usingsocialstoriesandvisualschedulestoimprove sociallyappropriatebehaviorsinchildrenwithautism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12, 149-160.

Shabani,D.B.,Katz,R.C.,Wilder,D.A.,Beauchamp,K.,Taylor,C.R.,&Fischer,K.J. (2002).Increasingsocialinitiationsinchildrenwithautism:Effectsofatactile prompt. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35,79-83.

Smith,T.(2001).Discretetrialtraininginthetreatmentofautism. Focus on Autism and other Developmental Disabilities, 16,86-92.

Travis,L.L.andSigman,M.(1998),Socialdeficitsandinterpersonalrelationshipsinautism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 4, 65–72.

White,S.W.,&Roberson-Nay,R.(2009).Anxiety,socialdeficits,andlonelinessinyouthwith autismspectrumdisorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39,10061013.

Wolf,M.M.(1978).Socialvalidity:Thecaseforsubjectivemeasurementorhowapplied behavioranalysisisfindingitsheart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11,203-214.

Wong,C.(2013). Social narratives (SN) fact sheet.ChapelHill:TheUniversityofNorth Carolina,FrankPorterGrahamChildDevelopmentInstitute.

Wong,C.,Odom,S. L.,Hume,K.Cox,A.W.,Fettig,A.,Kucharczyk,S.,…Schultz,T. R. (2014). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. ChapelHill:TheUniversityofNorthCarolina,Frank PorterGraham ChildDevelopmentInstitute,AutismEvidence-BasedPracticeReviewGroup.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |52

About the Authors

StephanieValentini isadoctoralstudentatTheUniversityofKansasintheAppliedBehavioral Sciencedepartmentandhasexperienceasabehavioranalystinthehome,clinic,andschool setting.

Dr.RachelRobertsonisanassistantprofessorofspecialeducationattheUniversityof Pittsburghwheresheteachesandconductsresearchinautismspectrumdisorders,behavioral disorders,andappliedbehavioranalysis.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |53

Identifying Special Education Professional Development Needs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

MorganChitiyo,Ph.D. DuquesneUniversity

ElizabethM.Hughes,Ph.D. ThePennsylvaniaStateUniversity

MohammedAladsani DuquesneUniversity

MohammedAlJaffal,Ph.D. KingSaudUniversity

SiddiqAhmed DuquesneUniversity

HamadHamdi DuquesneUniversity

Abstract

SincetheestablishmentofformalspecialeducationsystemsintheKingdomofSaudiArabia (KSA)in1958,thecountryhasmadeimportantstridesineffortstodevelopherspecialeducation system. Evenwithnotabledevelopments,morestillneedstobedone,especiallyintheareasof teacherpreparationandprofessionaldevelopment,toimprovethesystemofspecialeducational servicedelivery. Withresearchindicatingthatprofessionaldevelopmentofteachersismore effectiveiftheteachersthemselvesareinvolvedintheplanningprocess,theseresearchers wantedto getboth generalandspecialeducationteachersinthecountrytoparticipateintheir ownprofessionaldevelopmentplanning. Usinga surveymethod,theseresearcherssolicitedthe viewsof802in-serviceteachersinthecountryaboutinclusiveeducationandtheirspecial educationprofessionaldevelopmentneeds. Whiletheteacherswerealmostequallydivided aboutwhethertheyfavoredinclusiveeducationornot,theywereunanimousaboutthe importanceofprofessionaldevelopment. Theteachersalsoratedallthesuggestedprofessional developmenttopicsasimportant. Implicationsofthesefindingsarediscussed.

Identifying Special Education Professional Development Needs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

GeneralInformationabouttheKingdomofSaudiArabia

TheKingdomofSaudiArabia(KSA)wasestablishedbyIbnSaudin1932andislocatedin SouthwestAsia. Sincethediscoveryofpetroleumin1938,thecountryhasbecometheworld's largestoilproducerandexporter. Ithastheworld'ssecondlargestoilreservesandthesixth

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |54

largestgasreserves,whichmakesthecountrypoliticallyveryinfluential,particularlyinthe MiddleEast. TheKSAisgovernedbyamonarchyundertheinfluenceoftheIslamicreligion (RoyalEmbassyofSaudiArabiainWashington,DC,2016). AccordingtotheGeneral AuthorityforStatistics(2017),thepopulationofKSAwas32,552,336with20,768,627being Saudisandamajority(over67%)beingyoungpeoplelessthan30yearsold. Almost7%ofthe totalpopulationwerecategorizedashavingdisabilities(GeneralAuthorityforStatistics,2017).

TheEducationalsystem

In1925,beforetheofficialestablishmentoftheKSA,theDirectorateofKnowledgemarkedthe launchofthefirsteducationalsystemintheKSAandthissystemwasthecornerstoneofthe educationalsystemforboysinthenation(MinistryofEducation,2017). Thepowersofthe DirectorateofKnowledgeexpandedupontheestablishmentoftheKSAin1932.Sincethe establishmentoftheeducationsystem,boysandgirlshavebeenseparatedacrossalleducational levels(Alamri,2011). TheeducationintheKSAisfreetoallSaudisandnon-Saudistudents acrossalleducationallevels. However,freehighereducationisexclusivelyforSaudis.Thereare public,private,andinternationalschoolsintheKSAandallofthemmustadheretotheMinistry ofEducation’sstandardsandregulations(SaudiArabianCulturalMissionintheUSA,1991). Therearesix mainlevelsofpublic(governmental)andprivate(non-governmental)education: kindergarten,elementary,intermediate,secondary,university,andpostgraduate(Al-kahtani, 2015). PrivateschoolsareentitledtoreceivefinancialcontributionfromtheMinistryof Educationandtheymustfollowthesamecurriculumaspublicschools. Therearealsosome foreigninternationalschoolsinwhichEnglishisthelanguageofinstruction(Al-kahtani,2015).

SpecialEducation

Before1958,therewerenoformalspecialeducationservicesforindividualswithdisabilitiesin theKSA. Hence,parentsofstudentswithdisabilitieswereresponsibleforeducatingtheirown children(Al-Ajmi,2006).In1958,theKSAstartedaspecialeducationprogramforindividuals withvisualimpairment(Salloom,1995). By1962,theMinistryofEducationhadsetupa departmentforuniquelearningwhoseresponsibilitywastoimprovetheservicesrenderedto childrenwiththreetypesofdisabilitiesnamely,visualimpairment,hearingimpairment,and intellectualdisabilities(formerlymentalretardation)(Afeafe,2000).

In1987,theLegislationofDisabilitywaspassedtosafeguardtheinterests ofindividualswith physicaldisabilities. Thelawguaranteedequaleducationalrightsforchildrenwithdisabilities justliketheirpeerswithoutdisabilitiesandincludedmanyarticlesthatdefinedisabilities, describeprogramsforpreventionandintervention,andidentifyprocedures ofassessmentand diagnosistodetermineeligibilityforspecialeducationservices. TheLegislationofDisability alsoensuredthatpublicserviceproviders,suchasschools,accommodatedpeoplewith disabilities(MinistryofHealthCare,2010). In2000,theSaudigovernmentenactedthe DisabilityCode,whichguaranteedfreeaccesstoappropriaterehabilitationservicesforpeople withdisabilities(PrinceSalmanCenterforDisabilityResearch,2004). Furthermore,the MinistryofEducationrepresentativefromtheDirectorate GeneralofSpecialEducationand someprofessionalsfrom theDepartmentofSpecialEducationatKingSaudUniversity developedtheRegulationsofSpecialEducationProgramsandInstitutes(RSEPI),whichwere

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |55

modeledonthemainprinciplesoftheIndividualwithDisabilitiesEducationAct(IDEA)inthe UnitedStates. Althoughgreatstrideshavebeenmade,inthelastdecade,toimprovespecial educationservicesinthecountry,thereisstillneedtofurtherimprovethecurrentlyavailable services(Alquraini,2010).

IntheKSA,studentsclassifiedashavingmildlearningdisabilitieswereeducatedingeneral educationclassroomswithsomesupportsuchastimeinaresourceroom. Studentswithmildto moderatecognitivedisabilitieswereeducatedinseparateself-containedclassroomsinpublic schools(Al-Ajmi,2006). Ninety-sixpercentofstudentswithmultipleorseveredisabilitieswere educatedinseparateinstitutesin2007-2008;buttheseinstituteslackedrelatedservicessuchas occupationaltherapy,physicaltherapy,andspeechandlanguagepathologythatcouldbenefitthe students(Alquraini,2010;MinistryofEducation,2008).

TeacherPreparation

AlluniversitiesintheKSAofferatleastabachelor’sdegreeinspecialeducationwithsome offeringgraduatestudiesaswell. Allspecialeducationteachersarerequiredtohaveatleasta four-yearbachelor’sdegreeinteachingstudentswithspecificdisabilitiessuchasautism, learningdisabilities,andintellectualdisabilities,amongothers. Bothspecialand general educationteachersplayanimportantroleinimprovingthequalityofspecialeducationprograms andservices(Giangerco,Edelman,Broer,&Doyle,2001). Thus,theyneedtopossesssufficient skillsandknowledgetoprovideadequateandeffectiveeducationalservicesforstudentswith disabilities(Alquraini,2010). Ingeneral,thesuccessofanyinclusionprogram,accordingto Giangercoetal.(2001)andMcleskey,Henry,andAxelrod(1999),reliesongoodprofessional development. Allteachersneedtoparticipateinongoingprofessionaldevelopmenttopromote qualityeducationforchildrenwithspecialneeds(Alquraini,2010). IntheKSA,professional developmentiscommonlyprovidedthroughvariousformatssuchasseminarsandworkshops.

However,thereisstillneedinthecountrytoprovideprofessionaldevelopmentprogramsforall in-serviceteachersfocusingoninclusiveeducationandhowtoteachstudentswithdisabilitiesin theirclassrooms. Professionaldevelopmentprogramsshouldbeofferedthroughouttheschool yearforallspecialandgeneral educationteachers. Theseprogramsshouldfocusoneffective pedagogyandevidence-basedpracticesinspecialeducation. Inaddition,specialand general educationteachersshouldbeawareofthemethodsofcollaboration(Aldabas,2015),whichisso essentialforsuccessfulinclusionofstudentswithdisabilities.

FactorsInfluencingSpecialEducation

Severalstudieshaveexaminedteachers’perceptionstowardchildrenwithdisabilitiesinthe KSA. AstudyconductedbyAl-Faiz(2006)among240elementaryschoolteacherstoexamine theteachers’attitudestowardinclusiveeducationforstudentswithautismfoundthatmost participantshadpositiveattitudes. Al-Faiz’sstudyindicatedthatbeingfamily/relativesof studentswithdisabilityandexperienceofteachingstudentswithdisabilityinfluencedthe attitudesoftheteachers. Theperceptionsofteachersaboutstudentswithdisabilitiesarecritical tothesuccessfulimplementationofinclusiveeducation(Auramidis&Norwich,2002;Cross, Traub,Hutter-Pishgahi, &Shelton,2004).

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |56

Haimour(2013)evaluatedspecialeducationprogramsimplementedininclusiveschoolsinSaudi Arabiafromteachers’perspectives.Thefindingsindicatedthattheteachers'evaluationsof specialeducationprogramsintheirschoolsweregenerallypositive. Theresultsalsoshowed significantdifferencesin theteachers'evaluationsbasedontheirpositionandeducationallevels, withmorepositiveevaluationsfoundamongspecialeducationteacherswithmaster'sdegrees. In addition,therewerenosignificantdifferencesintheteachers'evaluationsbasedongenderor teachingexperience(Haimour,2013).

Al-Ahmadi(2009)conductedastudywith251specialandgeneraleducationteacherstoexamine theirattitudestowardstheintegrationofstudents withlearningdisabilitiesinregularSaudi publicschools. Theresultsshowedthatfemaleteachershadlowerpositiveattitudestowardsthe integrationofstudentswithlearningdisabilitiesthanmaleteachers. Inaddition,thestudy revealedthatteachers’levelsofeducationaffectedtheirattitudes. Forexample,teacherswho heldhighereducationdegrees(e.g.,masterordoctorate)weremorelikelytohavepositive attitudes. Thefindingsalsoindicatedthatbothgeneralandspecialeducationteachersbelieved theirtrainingwasinadequatetomanagethebehaviorsofstudentswithdisabilities,andtheywere concernedabouttheperceivedinabilityofregulareducationteacherstomeetthelearningneeds ofstudentswithspecialneeds(Alahmadi,2009).

Bakhsh(2009)evaluatedspecialeducationtrainingprogramsinKSAandfoundthattherewere somestrengthsregardingspecialeducationteachertrainingprogramsinKSAthatneededtobe promotedandsupported. However,therewerealsoseveralweaknessesthatneededtobe addressed. Someoftheweaknesseswerelimitedresearchontheneedsofspecialeducation teachers,whichincludebutarenotlimitedto,professionaldevelopmenttrainingprograms, class-management,andrisk-management(Bakhsh,2009).

Morerecently,Alquraini(2012)examinedSauditeachers’perspectivesregardingtheinclusion ofstudentswithsevereintellectualdisabilities. Thestudyindicatedthatteachershadslightly negativeperspectivestowardstheinclusionofstudentswithsevereintellectualdisabilities. Interestingly,thestudyalsoshowedthatgeneraleducationteachershadmorepositive perceptionsthanspecialeducationteachers(Alquraini,2012). Sincesomespecialeducation teacherswhoworkedwithstudentswithmilddisabilitiesininclusivesettingsparticipatedinthis study,theymighthavehadunsuccessfulexperienceswithinclusivesettings,whichmighthave influencedtheirperceptionsaboutinclusion. AsCook,Tankersley,Cook,andLandrum(2000) noted,negativeexperienceswithunsuccessfulinclusionmighthaveasignificanteffecton specialeducationteachers’perspectives. Inaddition,thegeneraleducationteacherswho participatedinCooketal.’sstudyworkedinpublicschoolsthathadspecialprogramsfor studentswithdisabilities. Hence,theymighthavehadanopportunitytointeractwiththese studentsinextra-curricularactivitiessuchasphysicaleducationandlunchtimeactivities, interactionswhichcould havebeenmorepositivethanacademiccurricularactivities;thismight havecontributedtotheteachers’positiveattitudes(Alquraini,2012).

Finally,Alshahrani(2014)investigatedschoolpersonnel’sattitudestowardinclusionofstudents withhearingimpairments.Thestudyreportedthatteacherstendedtobesomewhatagainst

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |57

inclusionofstudentswithhearingimpairmentsin mainstreamclasses. Assuch,researchseemed tohaveyieldedmixedresultsaboutinclusionintheKSA. Asaresult,Alquraini(2010)called formoreresearchtoassesstheattitudesofteachersandotherstakeholdersregardinginclusive educationandthefactorsbehindtheseattitudes. Alqurainialsoemphasizedthatpublicagencies shouldeducatefamiliesandthecommunity,throughthemedia,workshops,andconferences, abouttheimportanceofincludingchildrenwithdisabilitiesinregularclasses.

PurposeofthisStudy

Thisstudywasdesignedtoexplorethebeliefs,concerns,andspecialeducationprofessional developmentneedsofschoolteachersintheKSA. Thestudywasguidedbythefollowing researchquestions:(1)TowhatdegreedoschoolteachersintheKSAbelievethatstudentswith disabilitiesshouldbeeducatedtogetherwithstudentswithoutdisabilities? (2)Towhatdegreedo schoolteachersintheKSAindicatetheimportanceofprofessionaldevelopmentonteaching studentswithdisabilities?(3)WhatdoschoolteachersinKSAidentifyasprioritizedprofessional developmentneedsregardingspecialeducationknowledgeandservicesin KSA? (4)Whatdo educatorsinKSAidentifyasneedsforsuccessfulspecialeducationclassrooms? (5)Arethere differencesinattitudesbyplaceofemployment(i.e.,governmentorprivate),locationofschool (i.e.,urbanorvillage),anddegreespecialization(i.e.,whethertheyarespecialeducation certifiedornot)?

Method

SamplingandProcedure

Bothconvenienceandpurposefulsamplingwereusedtoaccessparticipantsforthisstudy. The researchersusedpurposefulsamplinginordertoaccessparticipantsfromthefiveregionsofthe country(i.e.,Central,Eastern,Western,Southern, andNorthernregions). Thequestionnairewas distributedelectronicallythroughmanyelectronic platformsandapplicationsonthesocialmedia suchasTwitterandWhatsApp. AccordingtoAbdurabb(2014),therearemorethan2.4million activeTwitterusersinSaudiArabia. Thus,theresearchersdistributedthequestionnairevia TwitterandWhatsApptomaximizethenumberofpotentialrespondentsreached. Finally,the surveywasalsodistributedviapersonalcontactsofsomeoftheauthorsofthisstudywhohave taughtinthedifferentregionsinthecountry. Asa result,atotalof802teachersparticipatedin thisstudy.

DemographicInformationofParticipants

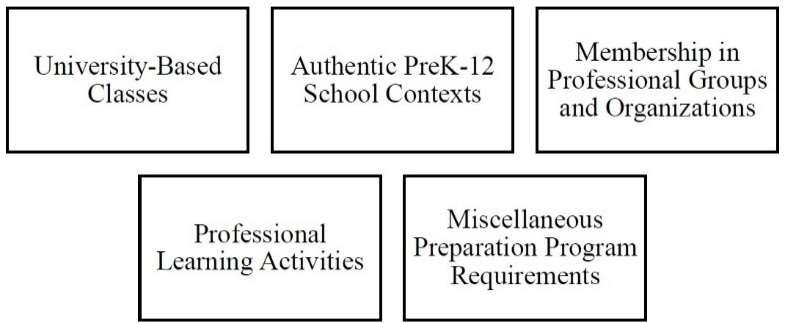

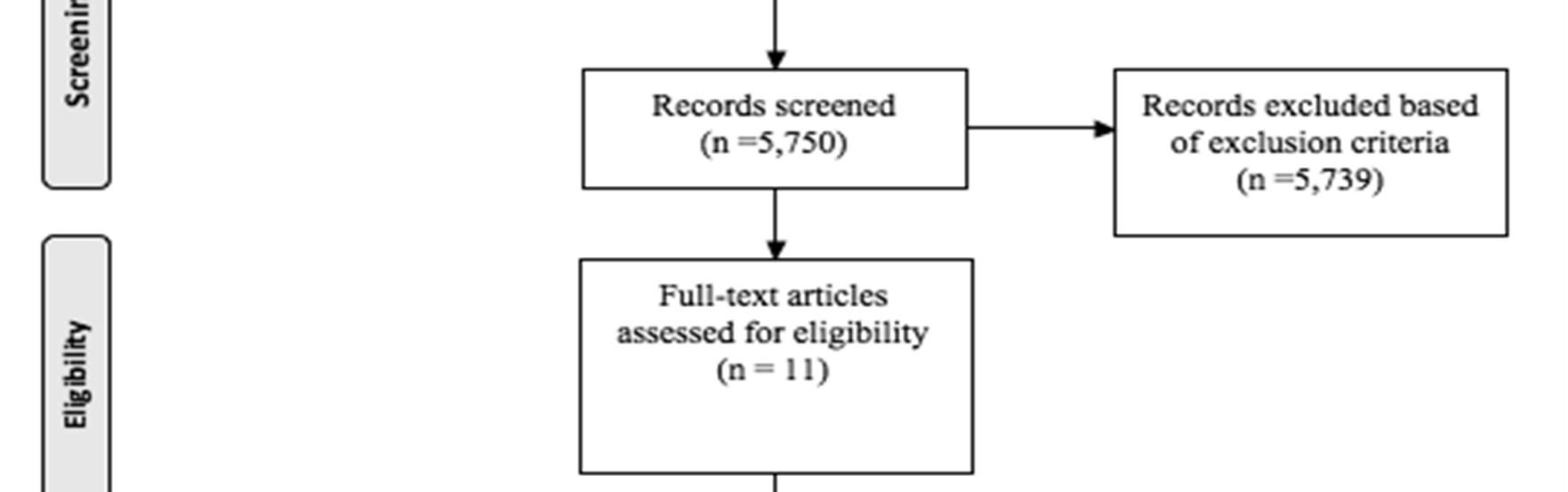

DemographicinformationabouttheparticipantsispresentedinTable1. About62%(n =500)of theparticipantsweremalewhileabout38%(n =302)werefemale;oneparticipantdidnot indicategender. Mostoftheparticipants(n =584;73%)hadabachelor’sdegree while18%(n = 141)hadamaster’sdegree;1%(n=10)hadcompletedmiddleschool,3%(n=22)hadadiploma, 2%(n =15)hadadoctoraldegree,and4%(n =31)indicated“other”withoutspecifying. A slightmajorityoftheteachers(n =471;59%)werequalifiedinspecialeducationwhiletherest werenot.

Overhalfoftheparticipants(n =454;53%)taughtelementaryschool,5%(n =41)taught kindergarten,14%(n =115)taughtmiddleschool, 15%(n =117)taughthighschool,andthe rest(n =106;13%)indicated“other”withoutspecifying. Mostoftheteachers(n =797;91%)

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |58

wereteachingatgovernment(public)schoolswhiletherest(n =76;10%) taughtatprivate schools. Amajorityoftheteachers(n =704;88%)alsotaughtaturbanschoolswhiletherest(n =99;12%)taughtatsuburbanorrural(village)schools. Theteacherswerealmostequally dividedintermsofthosewhowereteachingstudentswithdisabilitiesatthetimeofthestudy(n =458;57%)versusthosewhowerenot(n =345;43%). Finally,theteacherstaughtinvarietyof settingsincludinggeneraleducationclassroomwithoutstudentswithdisabilities(n =252;31%), inclusivegeneraleducationclassroom(n =49;6%),resourceroom(n =116;14%),special educationclassroominthegeneralschool(n =245;31%),institutionsofspecialeducation(n = 50;6%),rehabilitationcenters(n =21;3%),and“other”unspecified.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |59

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |60

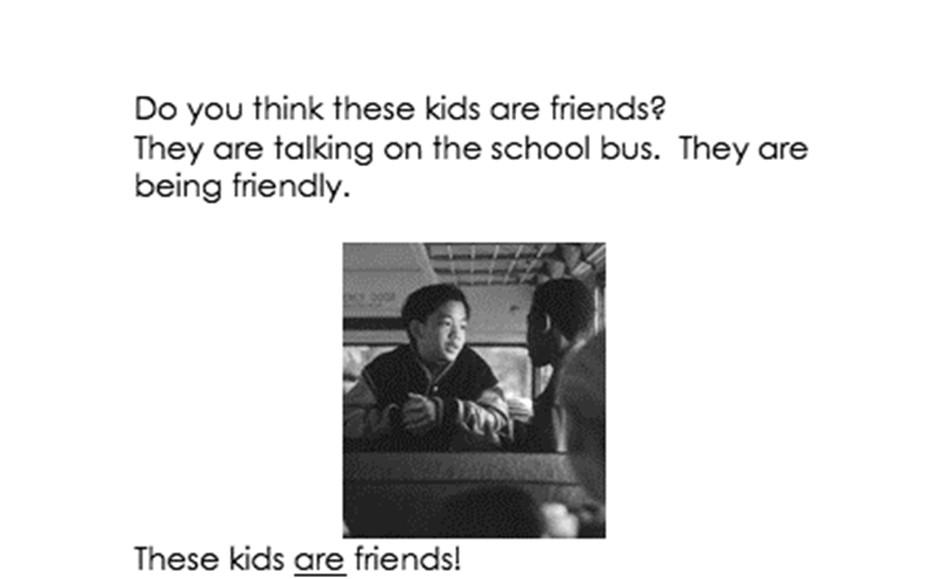

Table1

DemographicCharacteristics Numberof Teachers Percentof Teachers(%) Gender Male 500 62 Female 302 38 Highest Academic/Professional Qualification Middleschool 10 1 Diploma 22 3 Bachelor’sdegree 584 73 Master’sdegree 141 18 Doctoraldegree 15 2 Other 31 4 Any Qualification in Special Education? Yes 471 59 No 332 41 Grade Level Taught Kindergarten 41 5 Elementary 424 53 Middleschool 115 14 Highschool 117 15 Other 106 13 Type of School Taught Government(public) 727 91 Private 76 10 Location of School SuburbanorRural(village) 99 12 Urban 704 88 Teaching Students with Disabilities at the Time of Study Notteachingstudentswithdisabilities 345 43 Teachingstudentswithdisabilities 458 57 Type of Setting Generaleducationclassroomwithoutstudentswith disabilities 252 31 Inclusivegeneraleducationclassroom 49 6 Resourceroom 116 14 Specialeducationclassroominthegeneralschool 245 31 Institutionsofspecialeducation 50 6 Rehabilitationcenters 21 3 Other 70 9

Demographic Characteristics of the Participating Teachers

Instrumentation

Theresearchersusedamodifiedversionofthesemi-structuredquestionnairedevelopedby Chitiyo,Hughes,Changara,Chitiyo,andMontgomery(2016)toinvestigatespecialeducation professionaldevelopmentneedsinZimbabwe. Thequestionnaire,whichincluded12 demographicquestions,26Likert-typequestions,andthreeopen-responsequestions,was slightlymodifiedtofittheKSAcontext. Thechangesincludedlanguagerevisionstoreflectthe disabilitycategoriesrecognizedintheKSAaswellastranslationintoArabic. TheLikert-type questionselicitedparticipants’ratingsconcerningtheirbeliefsaboutinclusion,theneedfor professionaldevelopmentinspecialeducation,andtheimportanceofspecificspecialeducation professionaldevelopmenttopics. Theopen-responsequestionsaskedparticipantstolist,intheir ownwords,additionalareasofspecialeducationinwhichtheyneededprofessionaldevelopment aswellastoidentifyresourcesormaterialsneededforthesuccessfullearningofstudentswith disabilitiesintheirclassrooms. However,resultsofopen-endquestionswillbereported separatelyinanotherreportandwillnotbeincludedinthispaper.

Results

Teachers’AttitudestowardsInclusiveEducation

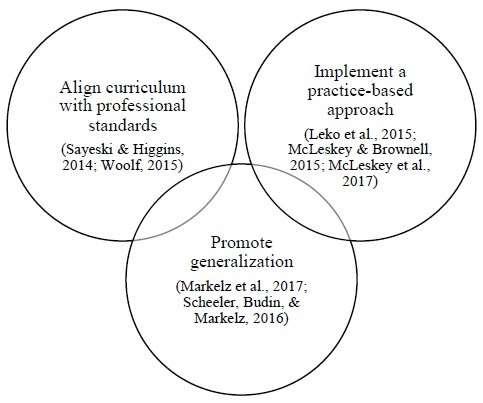

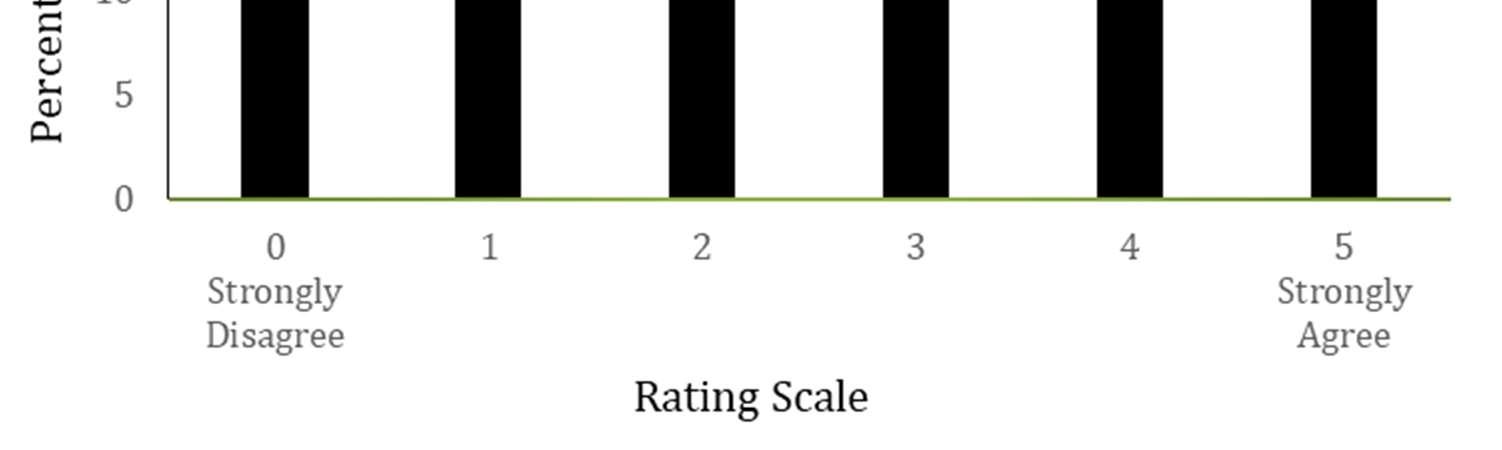

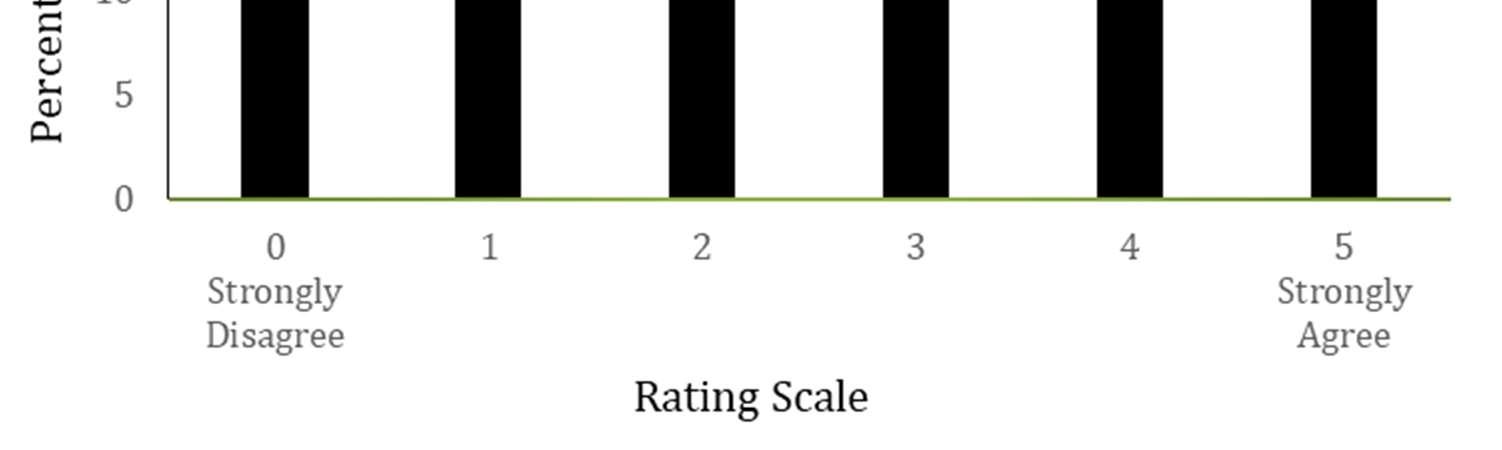

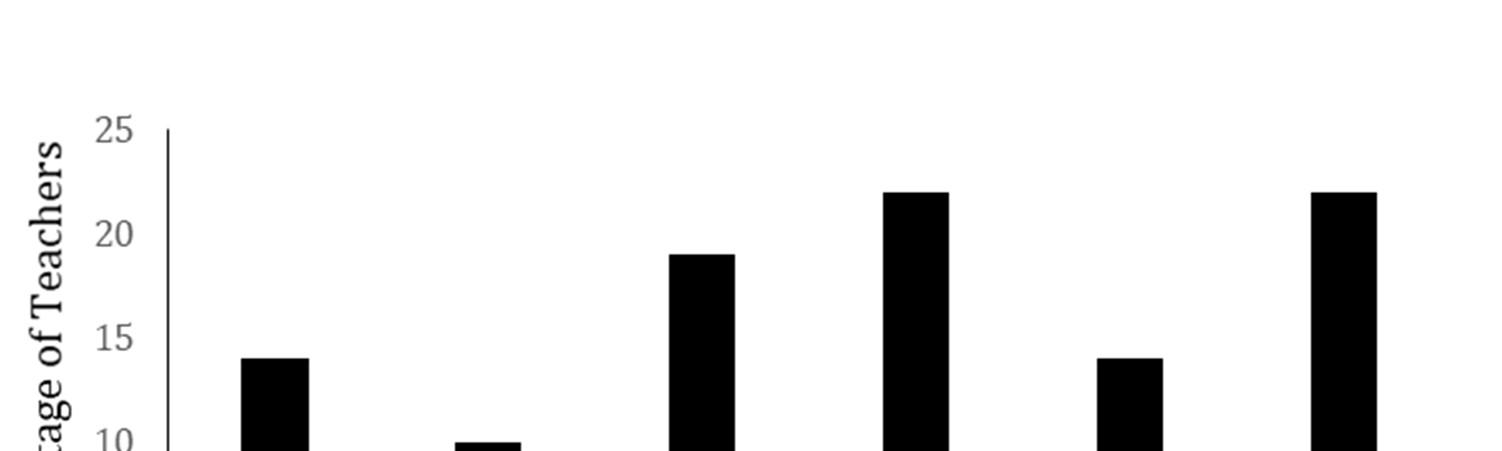

OnaLikertscalerangingfromzero(stronglydisagree)tofive(stronglyagree),theparticipants ratedtheirthoughtsabouteducatingstudentswithdisabilitiestogetherwith studentswithout disabilities. About14%(n =109)indicatedthattheystronglydisagreedwhile22%(n =173) stronglyagreedthatstudentswithdisabilitiesshouldbeeducatedtogetherwiththeirpeers withoutdisabilities. Overall,58%(n =463)respondedwitharatingofatleastthreewhile42% (n =339)respondedwith aratinglessthanthree. Thisindicatesthataslightmajoritysupported theideaofinclusiveeducationalbeitwithvaryinglevelsofenthusiasm. Figure1presentsthese ratings.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE

|61

Page

Figure 1. Teachers’RatingsWhetherStudentswithDisabilitiesShouldbeEducatedTogether withStudentswithoutDisabilities

TestsofDifferencesinTeachers’Attitudes

Several t testswereruntoassessdifferencesinteacherattitudesacrosscertainvariablessuchas typeofschool(i.e.,privatevs.government),locationofschool(i.e.,urbanvs.rural/village), gender,andwhethertheparticipantswereteachingstudentswithdisabilitiesornotatthetimeof thestudy. These t-testsresultsindicatedthefollowing:nosignificantdifferencein attitudes betweengovernment(M =2.75, SD =1.67)andprivate(M =3.04, SD =1.64, t(800)=-1.436, p >.05);nosignificantdifferenceinteachers'attitudesbetweenthoseteachinginurbanschools(M =2.82, SD =1.65)versusthoseinrural/villagesettings(M =2.52, SD =1.73, t(800)=-1.649, p >.05);nosignificantdifferenceinattitudesbetweenmaleteachers(M =2.73, SD 1.68)and femaleteachers(M =2.86, SD =1.63, t(799)=-1.120, p >.05). However,theresultsindicateda significantdifferenceinteachers'attitudesbetweenthosewhowereteachingstudentswith disabilitiesatthetimeofthestudy(M =2.89, SD =1.62)andthosewhowerenotteaching studentswithdisabilitiesatthetimeofthestudy(M =2.63,SD=1.71, t(800)=2.243, p >.05); educatorswhowereteachingstudentswithdisabilitieshadmorepositiveattitudes.

Regardingtestingfordifferencesinteachers'attitudesbywhetheranyoftheirdegreesor certificationswereinspecialeducation,Levene’stestindicatedthatthegroupshaddissimilar variances(F =8.134, p <0.01).Therefore,a t-testassumingunequalvarianceswasconducted, andtheresultindicatednosignificantdifferencebetweenthosewhohadadegreeinspecial education(M =3.03, SD =1.58)andthosewhodidnot(M =2.43, SD =1.72, t(675)=5.044,p< .001).

Teachers’PerceptionsaboutSpecialEducationProfessionalDevelopment

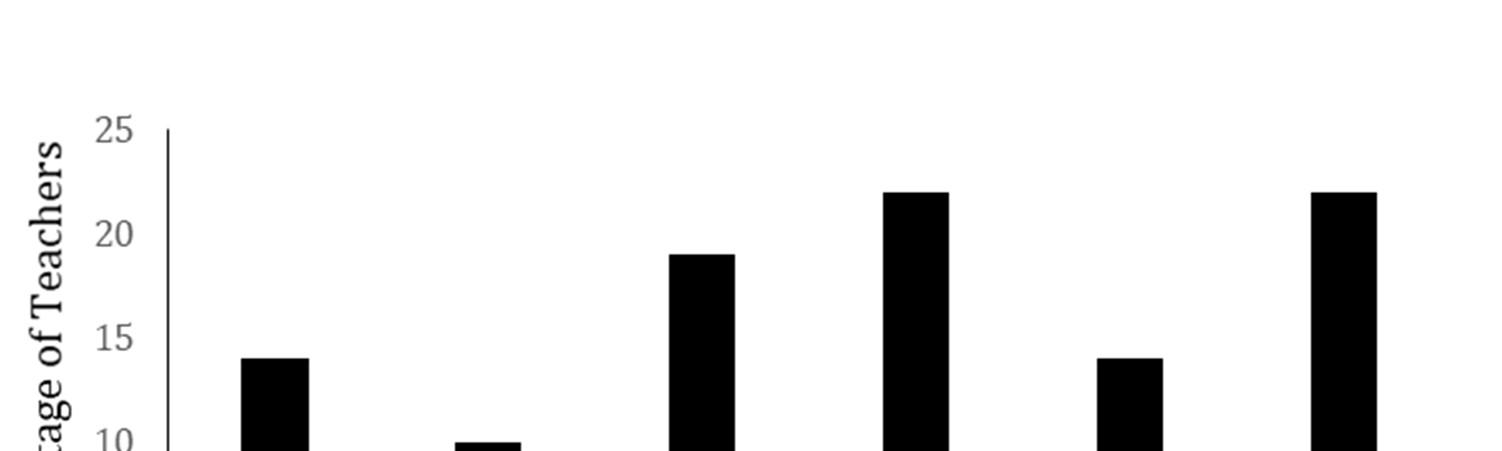

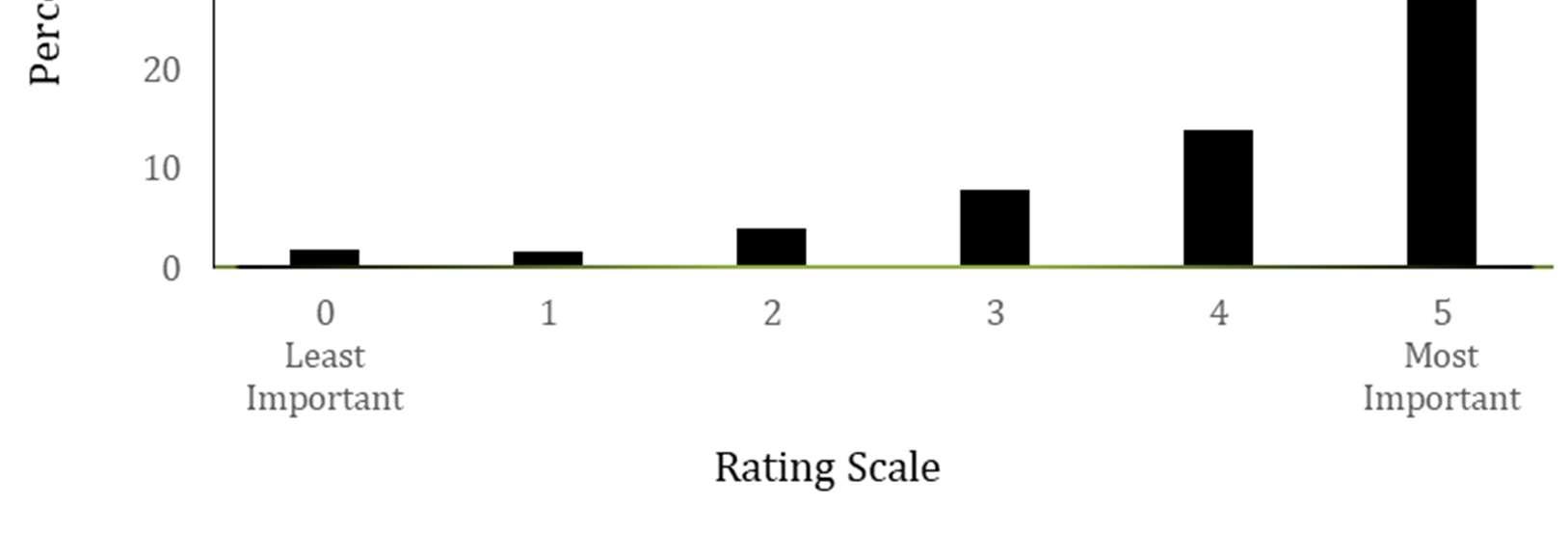

Theteacherswereaskedtorate,usingascalerangingfromzero (leastimportant)tofive(most important),howimportanttheythoughtprofessionaldevelopmentintheareaofspecial educationwas. Amajorityoftheteachers(71%; n =569)indicatedthatprofessional developmentwasmostimportantwhile2%(n =15)thoughtitwasleastimportant. Overall, 93%(n =743)oftheteachersrespondedwitharatingofatleastthreewhile8%(n =60) respondedwitharatinglessthanthree. TheseresultsarepresentedinFigure2.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |62

Figure 2. Teachers’RatingsoftheImportanceofProfessionalDevelopment Teachers’RatingsofSpecialEducationProfessionalDevelopmentTopics

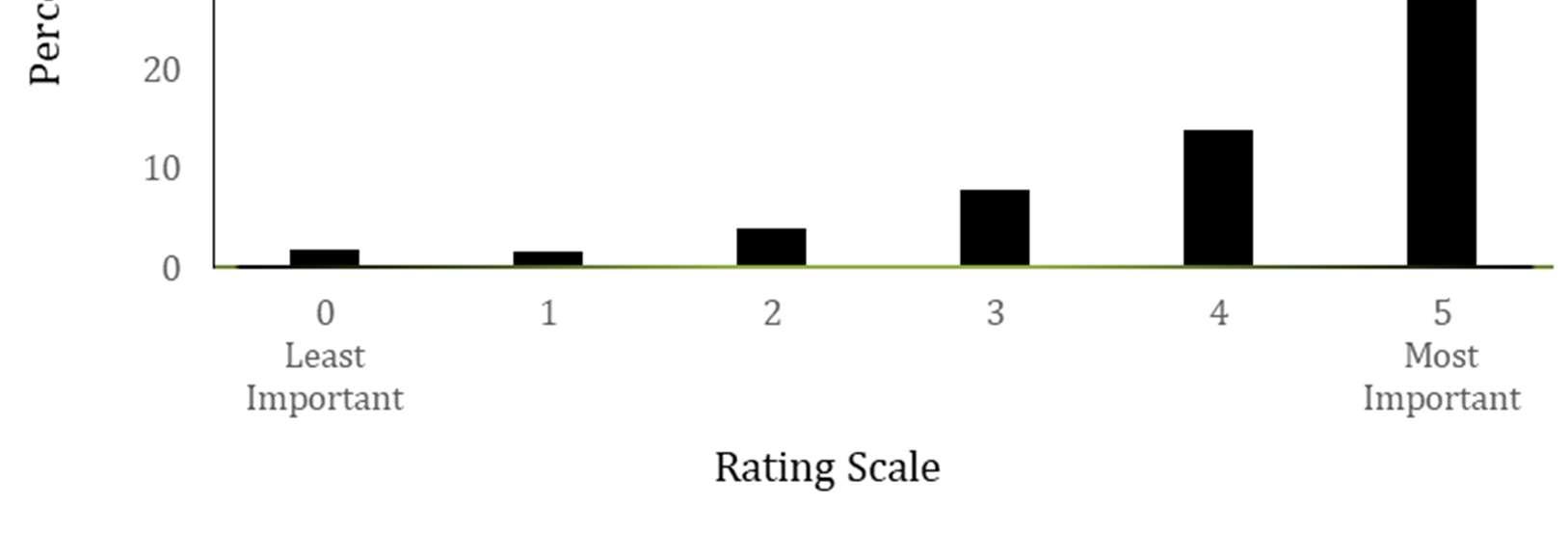

Theteacherswerepresentedwithseveralspecialeducationtopicsandaskedtorateeachofthem onascale rangingfromzero(leastimportant)tofive(mostimportant). Accordingtotheratings, allthetopicswere consideredtobeimportantwiththefollowingtopicsreceivingthehighestfive meanratings:teachinglifeskills(M =4.34; SD =1.15),howtodifferentiateinstruction(M = 4.32; SD =1.15),collaborationwithparents/guardians(M =4.29; SD =1.18),behavior management(M =4.28;SD=1.14),instructionalmethods(M =4.27; SD =1.18).Topicsthat receivedtheleastratingsincluded,birthtoagethree(M =3.32; SD =1.65),laws(M =3.50; SD =1.48),blindnessandvisualimpairment(M =3.61; SD =1.51). Theteachers’meanratingsof thespecialeducationprofessionaldevelopmenttopicsarepresentedinTable2.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |63

Teachers’ Mean Ratings of the Different Special Education Professional Development Topics

ItseemsteachersinKSAwerealmostequallydividedintheirperceptionsaboutinclusive educationwithaslightmajority(i.e.,58%)indicatingagreementthatstudentswithdisabilities shouldbeeducatedtogetherwiththeirpeerswithoutdisabilities. Thisfindingmaynotbe surprisinggiventhatpreviousstudieshaveyieldedmixedresultsregardingSauditeachers’ attitudestowardincludingstudentswithdisabilitiesinthegeneraleducationclassroom. For example,Al-faiz (2006)reportedpositiveattitudes,towardsinclusionofstudentswithautism, amongelementaryschoolteachersintheKSA. Onthecontrary,Alquraini(2012)foundthe attitudesofSauditeacherstowardsinclusiveeducationforstudentswithsevereintellectual disabilitytobenegative. However,itseemsfrom thesestudiesthatthedifferencesinattitudes tendtobeexplainedbythetypeofdisabilities,andotherfactorssuchasexperienceteaching

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |64

Table2

Discussion

Professional Development Topic N M SD Teachinglifeskills 803 4.34 1.15 Howtodifferentiateinstruction 803 4.32 1.15 Collaborationwithparents/guardians 803 4.29 1.18 Behaviormanagement 803 4.28 1.14 Instructionalmethods 803 4.27 1.18 Collaborationwithcolleagues 803 4.21 1.20 Discipline 803 4.17 1.21 Organizingyourteaching 803 4.11 1.24 Disabilitycharacteristics 803 4.11 1.26 ADHD 803 4.11 1.29 Learningstrategies 803 4.03 1.34 LearningDisabilities 803 4.00 1.37 BehaviorDisorders 803 3.99 1.34 Consideringthediversityofcultures 803 3.96 1.27 OtherHealth-relatedconditions 803 3.96 1.35 Assessment 803 3.92 1.30 Autism 803 3.87 1.44 IntellectualDisabilities(mentalretardation) 803 3.85 1.45 DeafnessorHardofhearing 803 3.75 1.52 InclusiveEducation 803 3.73 1.41 PhysicalDisabilities 803 3.72 1.50 BlindnessorVisualImpairment 803 3.62 1.51 Laws 803 3.50 1.48 BirthtoageThree 803 3.32 1.65

studentswithdisabilities,teachers’gender,andwhethertheteachersweregeneralorspecial educationteachers(Alquraini,2012).

Nevertheless,inthiscurrentstudytheresultsindicatednosignificantdifferencesinteachers’ attitudestowardinclusiveeducationbasedontheteachers’typeofschooltheytaughtat(i.e., privateversusgovernment),locationofschool(i.e.,urbanversusrural/village),theirgender,and whethertheyhadaspecialeducationdegreeornot. Theonlysignificantdifferencewasfound basedonwhethertheteacherswereteachingstudentswithdisabilitiesatthetimeofthestudyor not,withthosewhowereteachingstudentswithdisabilitieshavingmorepositiveattitudes towardsinclusiveeducationthanthosewhowere not. Thismaynotbesurprisingbecause exposuretoindividualswithdisabilitieshasbeenfoundtopositivelyinfluenceteacherattitudes (Park&Chitiyo,2009;2011). However,whatis surprisingisthatthisfindingseemsto contradictresultsofAlquraini’s(2012)studyindicatingthatgeneral educationteachersinKSA hadmorepositiveattitudestowardsinclusiveeducationthanspecialeducationteachers.

Alquraini’sfindingswouldbesurprising,ifweassumethatspecialeducationteachersgenerally havemoreexposuretostudentswithdisabilitiesthangeneraleducationteachers.Furtherstudies wouldbeneededtoexplorethisseemingcontradiction.

Itisnoteworthyandencouragingthatanoverwhelmingmajority(93%)oftheteachersrated professionaldevelopmentintheareaofspecialeducationasimportant. Inacountrywhere specialeducationisstilldeveloping,professionaldevelopmentforteachersisessentialasitcan contributetotheimprovementofteacherquality(Colbert,Brown,Choi,&Thomas,2008). However,inorderforprofessionaldevelopmenttobeeffectivelyconducted,establishingteacher buy-iniscrucialbecauseitcanpositivelyinfluencethesuccessofsuchefforts(Borko,2004; David&Bwisa,2013). Thisiswhythisfindingisnoteworthyandencouraging. TheKSAcan buildonthisandmakenotablestridesinthedevelopmentofspecialandinclusiveeducation.

Intermsoftheprofessionaldevelopmenttopics,theteachersratedallthelistedtopicsas importantwiththeleastratedtopichavingameanratingof3.32. Thetoptentopicsallhad meanratingsrangingfrom4.11to4.34,whichsuggestthattheywereconsideredveryimportant. Amongthesetopicswere teaching life skills, behavior management, differentiating instruction, discipline,and instructional methods amongothers. Thesefindingssuggestthattheteachers recognizedtheneedtoimprovetheirinstructionalandbehaviormanagementskillsandtheir knowledgeaboutdisabilitiesandthespecialandinclusiveeducationprocesses. Indeed,the MinistryofEducationprovidesprofessionaldevelopmentprogramsthroughouttheyear. However,theprogramsarenotmandatoryandwhethertheteachersattendornotdoesnothave bearingontheteachers’positions.

Asindicatedearlierinthispaperandelsewhere,involvingteachersintheplanningoftheirown professionaldevelopmentisanimportantinitialstepinthedevelopmentofeffectiveprofessional developmentfortheteachers(Charema,2010;Colbertetal.,2008). Thisstudyshouldbe interpretedassuchaneffortandthefindingsshouldinformpolicymakersandteacher preparationprogramsinthecountryonwhattoprioritizeintermsofbothpreserviceteacher preparationaswellasprofessionaldevelopmentforin-serviceteachers.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |65

Conclusion

FormalspecialeducationservicesintheKSAcanbetracedbackto1958.Sincethattime,the countryhasmadeimportantstridesineffortstodevelopherspecialeducationsystem. These effortsincludefundingandspecialeducationteacherpreparation. Inspiteofthenotable developments,morestillneedstobedonetoimprovethesystemofspecialeducationalservice delivery. Inparticular,thereisneedfordevelopingmoreprofessionaldevelopmentprogramsfor bothforbothgeneralandspecialeducationteachersintheareaofspecialeducation. Current researchindicatesthatprofessionaldevelopmentofteachersismoreeffectiveiftheteachers themselvesareinvolvedintheplanningprocess. Thiscurrentstudywasanattempttodothat. Theseresearcherswantedtosolicittheviewsofin-serviceteachersinthecountryaboutinclusive educationandtheirspecialeducationprofessionaldevelopmentneeds. Whiletheteacherswere almostequallydividedaboutwhethertheyfavoredinclusiveeducationornot,theywere unanimousabouttheimportanceofprofessionaldevelopment. Theteachersalsoregardedallthe differentprofessionaldevelopmenttopicsasimportant. Thesefindingsareimportantbecause teachers’viewscaninfluencetheirparticipationinprofessionaldevelopment. Futureresearch shouldexploreefficientwaystoimplementprofessionaldevelopmentforteachers. Suchefforts couldincludehowtouseonlinebasedplatforms,whicharecompatiblewiththeadvancein technologyacrosstheregion.

References

Abdurabb,K.T.(2014,June). SaudiArabiahashighestnumberofactiveTwitterusersinthe Arabworld.ArabNews.Retrievedfromhttp://www.arabnews.com/news/592901

Al-Ajmi,N.(2006). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Administrators’ and special education teachers’ perceptions regarding the use of functional behavior assessments for students with intellectual disabilities (UnpublishedDoctoralDissertation).Universityof Wisconsin-Madison,MadisonWS.

Afeafe,M.Y.(2000).SpecialeducationinSaudiArabia.Retrievedfrom http://www.khayma.com/education-technology/PrvEducation3.htm

Alahmadi,N.A.(2009). Teachers’ perspectives and attitudes towards integrating students with learning disabilities in regular Saudi public schools (Doctoraldissertation).Retrieved fromProQuestDissertationsandThesesGlobal.(AAT3371476)

Alamri,M.(2011).HighereducationinSaudiArabia. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 11(4),88-91.

Aldabas,R.A.(2015).SpecialeducationinSaudiArabia:Historyand areasforreform. Creative Education, 6,1158-1167.

Alfaiz,H.S.(2006).AttitudesofelementaryschoolteachersinRiyadh,SaudiArabiatowardthe inclusionofchildrenwithautisminpubliceducation(Doctoraldissertation).Available fromProQuestDissertationsandThesesdatabase.(UMINO.AAT3262967).

Al-kahtani,M.A.(2015). The Individual Education Plan (IEP) process for students with intellectual disabilities in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and solutions.(Thesis).KingSaudi University,KSA.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE

66

Page |

Alquraini,T.A.(2012).Factorsrelatedtoteachers’attitudestowardstheinclusiveeducationof studentswithsevereintellectualdisabilitiesinRiyadh,SaudiArabia. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 12(3),170–182.

Alquraini,T.(2010).SpecialeducationinSaudiArabia:Challenges,perspectives,future possibilities. International Journal of Special Education, 25(3),139-147.

Alshahrani,M.(2014).Saudieducators’attitudestowardsdeafandhardofhearinginclusive educationinJeddah,SaudiArabia(Doctoraldissertation).Retrievedfrom https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/15846

Auramidis,E.,&Norwich,B.(2002).Teachers'attitudetowardintegrationinclusion:Areview ofliterature. Journal of Special Education, 17(2),129-147.

Bakhsh,A.(2009).Therealityofspecialeducationin-serviceteachertrainingprogramsin KSA,andimprovementplansassuggestedbyteachers. Educational Journal, Kuwait University. 23(90)125-179.

Borko,H.(2004).Professionaldevelopmentandteacherlearning:Mappingtheterrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8),3-15.

Charema,J.(2010).InclusionofprimaryschoolchildrenwithhearingimpairmentinZimbabwe. Africa Education Review, 7(1),85–106.

Chitiyo,M.,Hughes,E.M.,Changara,D.M.,Chitiyo,G.,&Montgomery,K.M.(2016). Specialeducationprofessionaldevelopmentneeds inZimbabwe. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(1),48-62.DOI:10.1080/13603116.2016.1184326

Colbert,J.A.,Brown,R.S.,Choi,S.,&Thomas,S.(2008).Aninvestigationoftheimpactsof teacher-drivenprofessionaldevelopmentonpedagogyandstudentlearning. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(20),135–154.

Cook,B.G.,Tankersley,M.,Cook,L.,&Landrum,T.J.(2000).Teachers’attitudestowardtheir includedstudentswithdisabilities. Exceptional Children, 67(1),115–35.

Cross,A.F.,Traub,E.K.,Hutter-Pishgahi, L.,&Shelton,G.(2004).Elementsofsuccessful inclusionforchildrenwithsignificantdisabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 24(3),169-183.

David,M.N.,&Bwisa,H.M.(2013).Factorsinfluencingteachers’activeinvolvementin continuousprofessionaldevelopment:AsurveyinTransNzoiaWestDistrict,Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(5),224235.

Elyas,T.,&Picard,M.(2013).CritiquingofhighereducationpolicyinSaudiArabia:Towardsa newneoliberalism. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 6(1),31-41.

Giangerco,M.F.,Edelman,S.W.,Broer,S.M.,&Doyle,M.B.(2001).Paraprofessional supportofstudentswithdisabilities:Literaturefromthepastdecade. Exceptional Children, 68(1),45-63.

GeneralAuthorityforStatistics(2017). Kingdom of Saudi Arabia population.Retrievedfrom https://www.stats.gov.sa/en

Haimour,A.(2013).Evaluationofspecialeducationprogramsininclusiveprogramsofferedin inclusiveschoolsinSaudiArabiafromteachers’perspectives. Life Science Journal, 10(4),57–66

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |67

Mcleskey,J.,Henry,H.,&Axlerod,M.I.(1999).Inclusionofstudentswithlearningdisabilities: Anexaminationofdatafromreportstocongress. Exceptional Children, 66(1),55-66.

MinistryofHealthCare.(2010).Careofpeoplewithdisabilities.RetrievedfromMinistryof HealthCarewebsite:http://mosa.gov.sa/portal/modules/smartsection/item.php?itemid

MinistryofEducationofSaudiArabia.(2008).Developmentofeducationinthekingdomof SaudiArabia.Riyadh,SaudiArabia.

MinistryofEducationofSaudiArabia.(2017).Establishment[Online].Riyadh:KSA:Ministry ofEducationofSaudiArabia.Availablefrom:

https://www.moe.gov.sa/en/TheMinistry/Education/Pages/EstablishmentoftheMinistryof Education.aspx

Park,M.,&Chitiyo,M.(2009).Aproposedconceptualframeworkforteachers’attitudes towardschildrenwithautism. Southern Teacher Education, 2(4),39–52.

Park,M.,&Chitiyo,M.(2011).Anexaminationofteacherattitudestowardschildrenwith autism. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(1),70–78.

RoyalEmbassyofSaudiArabiainWashington,DC.(2016). About Saudi Arabia. Retrieved fromRoyalEmbassywebsite:http://www.saudiembassy.net/about/country information/default.aspx

PrinceSalmanCenterforDisabilityResearch.(2004). Kingdom of Saudi Arabia provision code for persons with disabilities.Riyadh,SaudiArabia.

Salloom,I.H.(1995).EducationinSaudiArabia(2ndEd.)Beltsville,MD:AmanaPublications. SaudiArabianCultural MissionintheU.S.A.(1991) Education in Saudi Arabia (1stedition). WashingtonDC:SaudiArabianCulturalMission.

AbouttheAuthors

MorganChitiyo,Ph.D., isdepartmentchairandprofessorofspecialeducationatDuquesne University.Heisformereditorofthe Journal of the International Association of Special Education,thefoundingandcurrentco-editorofthe African Journal of Special and Inclusive Education,andassociateeditorof Journal of International Special Needs Education.His researchinterestsareintheareasofbehaviormanagementandprofessionaldevelopmentfor teachers.

ElizabethM.Hughes,Ph.D., isanassistantprofessorofspecialeducationatthePennsylvania StateUniversity.Herresearchfocusesonacademicinterventionsforstudentswithdisabilities. Recentresearchincludestheuseofvideo-basedinterventionstoteachmathematicstostudents withautismanduseofgraphicnovelstoteachscienceandmathematicscontent.

MohammedAladsani isadoctoralcandidateinspecialeducationatDuquesneUniversity.His focusareasareassessmentandlearning.

MohammedAlJaffal,Ph.D.,isanassistantprofessorofspecialeducationatKingSaud University.Hisresearchinterestsareintheareasofprofessionaldevelopmentforgeneral educationteachersandevidence-basedpracticeforstudentswithautism.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |68

SiddiqAhmedSiddiq isadoctoralcandidatespecialeducationatDuquesneUniversity.He receivedfourmaster’sdegreeinlinguistic,educationaladministration,professionalspecial educationandMasterofScienceinspecialeducation.Hisresearchinterestsincludepositive behaviorsupports,peermediatedinterventionforstudentswithspecialneeds,andservicesand supportsforindividualswithautismindevelopingcountries.

HamadHamdi isadoctoralcandidateinspecialeducationatDuquesneUniversity.Hisfocus areasarebehaviordisordersandautism.

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |69

Portrayals of Inclusive Teaching Practices: The Nature and Extent of Special Education in Journals for Mathematics Teachers

BenjaminS.Riden,M.Ed. AndreaV.McCloskey,Ph.D.

Pennsylvania

StateUniversity

Abstract

Thiscontentanalysisstudyinvestigatestheleadingmathematicsteachingpractitionerjournals publishedbytheNationalCouncilforTeachersofMathematics(NCTM).Thepurposeisto identifywhatmessagesandresourcesmathematicsteachersarebeingprovidedregardinghow studentswithdisabilitieslearnmathematicsandhowteachersshouldinstructstudentswith disabilities.Bywayofacontentanddiscourseanalysis,weexamined27articlesfocusingon areasofspecialeducation,supportingresearch,mathematicalcontentareas,andsuggested teachingstrategiesincludedinthisprofessionalresourcegenre.Additionally, adiscourse analysiswasconductedtoexaminewhosevoices arerepresentedinarticlesthatprovideteacher andstudentdialogue.FindingssuggestNCTMpractitionerjournalsareconsideringavarietyof disabilitycategories,pullingfrommultipleresearchbases,focusingonstudentsinelementary andmiddlesschoolmorethanhighschool,andofferingstrategiesformathematicseducators workingwithstudentswithdisabilities.Implicationsforresearchandpracticearepresented.

Keywords: mathematicseducation,specialeducation,studentswithdisabilities

Portrayals of Inclusive Teaching Practices: The Nature and Extent of Special Education in Journals for Mathematics Teachers

EversincethereauthorizationoftheIndividualwithDisabilitiesEducationAct(IDEA)in2004, inclusivityhasbeenthelawoftheland.Asaresult,demandsongeneraleducationteachershave increasedtoincludenotonlynewerandmore“rigorous”curricularstandards,suchasthose espousedintheCommonCore,butalsotheexpertisetobeabletomeettheacademicneedsofan increasedrangeofstudents.WesharethevisionoftheNationalCouncilforTeachersof Mathematics(NCTM),theCouncilforExceptionalChildren(CEC),andotherorganizationsthat emphasizetheimportancethatALLstudentstobeaffordedopportunitiestobeactiveknowers anddoersofimportantmathematics.Inits Principles to Actions document,NCTM(2014) describestroublingandunproductiverealitiesincontemporaryschoolinginthisway:

Toomanystudentsarelimitedbylowerexpectationsandnarrower curriculaofremedial tracksfromwhichfeweveremerge.Anexcellentmathematicsprogramrequiresthatall studentshaveaccesstoahigh-qualitymathematicscurriculum,effectiveteachingand learning,highexpectations,andthesupportandresourcesneededtomaximizetheir learningpotential(p.35).

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |70

Weagreewiththisprinciple.However,ouryearsofexperienceasaspecialeducationteacher (firstauthor)andasecondarymathematicsteacher (secondauthor),aswellasourcurrentwork asteachereducatorsandresearchersinourrespectivefields,haveconvincedusthatgeneral educationteachersremainunder-supportedtoenactthesegoals.Wethereforesoughtoutto empiricallyinvestigatethequantityandqualityofprofessionalsupportcurrentlyprovidedto mathematicsteachersfortheirworkinteachingstudentswithdisabilities.

Wecanevaluatethequalityandquantityofprofessionalresourcesandsupportintermsofthe programmaticcontentinteacherpreparationandtherehasindeedbeenresearchofthistype(e.g., Blanton,Pugach,&Florian,2011;Dieker&Berg,2002),butinthisstudyweexaminethe resourcesprovidedtopracticingteachersthroughthemeansofprofessionalteacherjournals.We examinedlessonspublishedinhighlyregarded,widelycirculating,peer-reviewedjournals writtenforpracticingteachersofmathematicsattheelementary,middle,andsecondarylevels. ThesethreejournalsarepublishedbytheNCTM,andcanthereforebeconsideredtorepresentat leastsomelevelofinstitutionalandauthoritativeperspective.Mostofthese articlespresent lessonsoractivitiesforeducatorstouseintheirownclassroomteaching,andsomeofthemalso presentfindingsfromclassroom-based,empiricalresearchreportingontheimplementationof thosesameactivities.Weanalyzethenatureandextentoftheintegrationofmathematics educationwithspecialeducationresearchbodies.

Guidingourcontentanalysisexaminationwasthequestion“Whatarticleshavebeenpublished inmathematicsteachingpractitionerjournalsfrom2004-presentregardingstudentswith disabilities?”Weoperationalizedthisquestionusingthefollowingsub-questions:

Whattypesofscholarshiparepublished—empirical,classroom-based,theoretical,etc.?

Whatresearchbodiesofliteraturedotheauthorsdrawupon?

Whatkindsofteachingsuggestionsarebeingprovidedtoteachers?

Whatbarriersarethereportedteachersandstudentsfacing?

Whatmathematicscontentareasaretheyaddressing?

Inanyincludedexcerptsofclassroomdialogue,whoisdoingmoretalking:teachersor studentswithdisabilities?

Followingouranalysisofthecontentcontainedinthesearticles,wedrawconclusionsonwhat messagesteachersare—andarenot—receivingfromthisparticulargenreofprofessional resource.Weconcludewithsuggestionsoffuturedirectionsforresearchforbothspecial educationandmathematicseducationresearchers,andweespeciallymakethecasefortheneed forcontinuedcollaborationsamongthesefields.

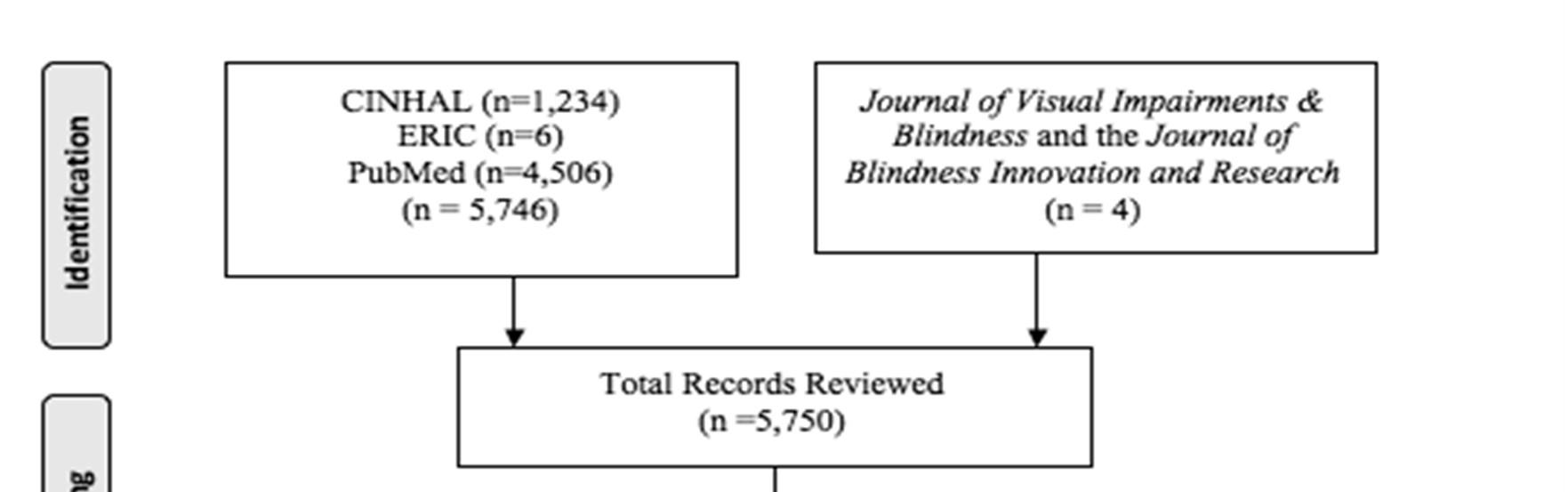

Methods

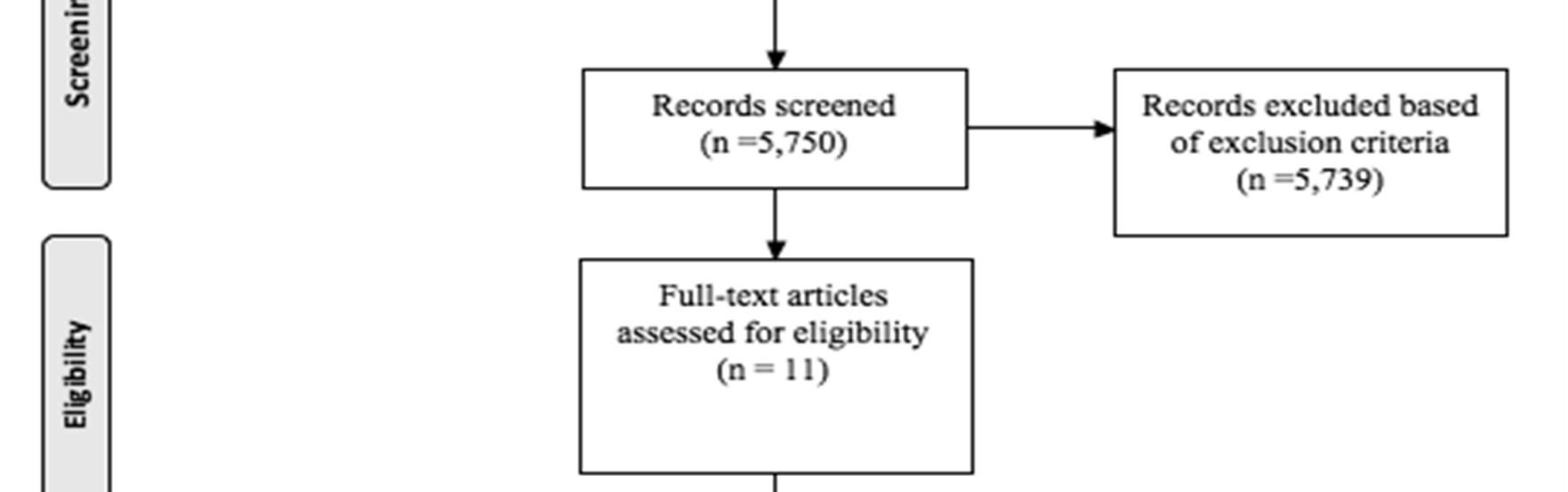

Articlesidentifiedforinclusionarepractitionerarticlesexaminingstrategiesforworkingwith studentswithdisabilitiesingeneraleducationmathematicssettings.Tobeincludedinthis contentanalysis,articleshadtobeEnglishlanguagepeer-reviewedarticlespublishedafter2004 inoneofthethreepractitionerjournalspublishedbytheNCTM(i.e., Teaching Children

HOFSTRAUNIVERSITY SPECIALEDUCATIONRESEARCH,POLICY&PRACTICE Page |71