Language Arts

Popular Culture and Media Literacy

Nation Council of Teachers of English 93rd Annual Convention

November 20-25, 2003

San Francisco, California

Share

ideas with the classroom teachers from across the country

Discover the latest in teaching resources and strategies

Connect with the best minds in English language arts

Interactive sessions, world-class speakers, daylong workshops, special events, and more to inspire, invigorate, and renew your teaching. You’ll return to school with new ideas and energy that will make you difference in your classroom.

Featured Speakers:

Robert MacNeil, former anchor of MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour and author of the upcoming Do You Speak American?

Chang-rae, author of Native Speaker and a Gesture Life

For convention details-including additional speakers, updates, registration and hotel information-and much more, visit http://www.ncte.org/convention

PHOTOS: SAN FRANCSCO CONVENTON & VISITORS BUREAUPopular Culture and Media Literacy

99 THOUGHTS FROM THE EDITORS

100 Popular Literacies and the “All” Children: Rethinking Literacy Development for Contemporary Childhoods

Anne Hoas Dyson

110 Bringing the Outside In: One Teacher’s Ride on the Anime Highway

Dibba Mahar

118 What Pokemon Can Teach Us about Learning and Literacy

Vivian Vasquez

126 E-mail as Genre: A Beginning Writer Learns the Conventions

Julie E. Wollman-Bonilla

135 Children’s Book Publishing in Neoliberal Times

Daniel Hade & Jacqueline Edmondson

145 Children’s Everyday Literacies: Intersections of Popular Culture and Language Arts Instruction

Donna E. Alvermann & Shelley Hong Xu

Departments

155 SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING ON POPULAR CULTURE AND MEDIA LITERACY

Carnen Luke

156 READING CORNER FOR EDUCATORS

The Place of Media and Popular Culture in Literacy Instruction

Danling Fu, Linda Leonard Lamme, & Zhihui Fang

158 READING CORNER FOR CHILDREN

The 2003 Orbis Pictus Award Winner and Other Recommended Nonfiction Books

Carolyn Lott, Christine Duthie, Nancy Hadaway, Julie M. Jensen, Deborah L. Thompson, James Valle, Sandip LeeAnne

Wilson, & Carol Avery

164 Profile An Interview with Bernice E. Cullinan, Outstanding Educator in the Language Arts

Dorothy S. Strickland & Lee Galda

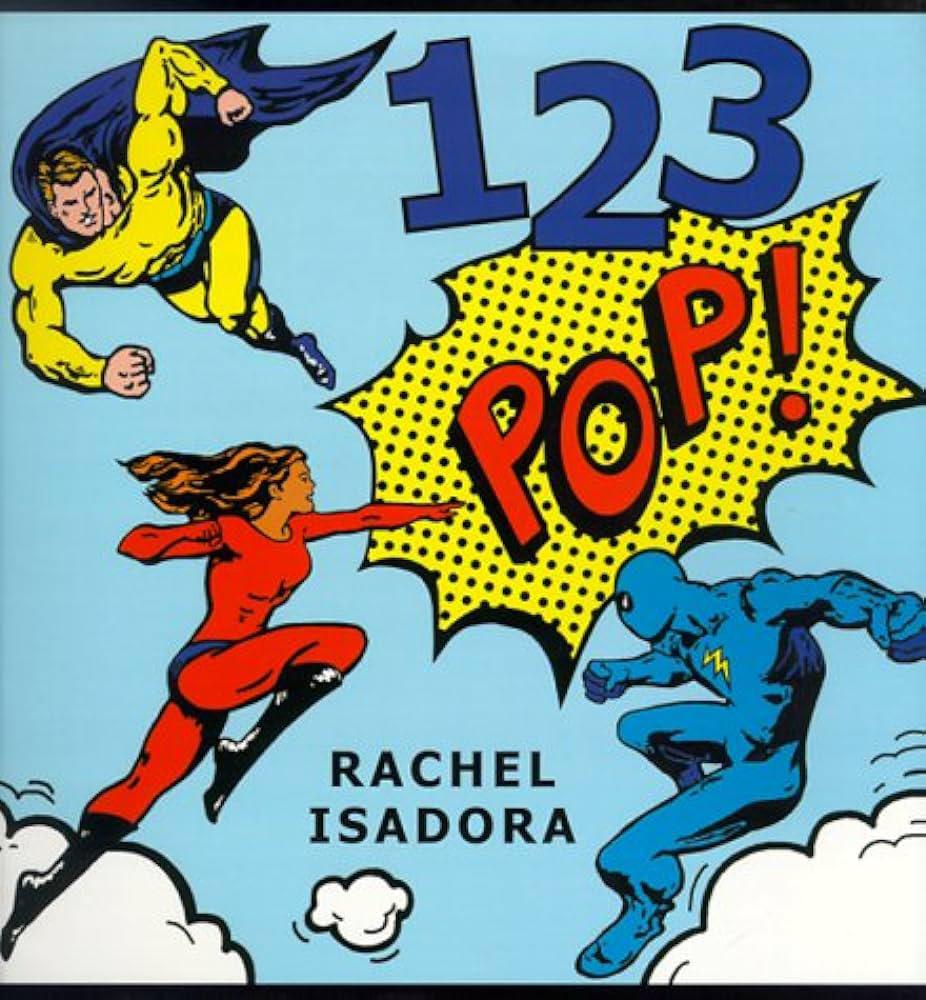

Cover and interior ilustration from 1 2 3 Pop! by Rachel Isadora. Used by permission of Viking Children’s Books, a division of Penguing Young Readers Groups. Illus. © 2000 by Rachel Isadora. Vol. 81 No. 2 November 2003 National Council of Teachers of English

Teaching Spelling, Grades k-6

Cindy Marten

Foreword by Donald H. Graves

Finally, here is the groundbreaking spelling book all teachers have been waiting for a sensible, comprehensive, research-based approach to word study that includes exploration, strategies, classroom-based assessment. and fabulous taching ideas - all based on learning how to determine each student’s level of spelling development and craft appropiate instruction. An exceptional resource.

-Regie RoutmanAt long last, a spelling and vocabulary book written by a classroom teacher who’s a literacy specialist, too!

Cindy Marten respons to the demand for “direct, systematic, and explicit phonies and spelling instruction”that goes way beyond what to teach - she addresses the questions of how, when, and why spelling should be taught, More important, she situates spelling within the contexts of real writing and the individual learner’s needs.

In Word Crafting, Marten offers an approach that is the once playful, intellectual, and awful, engaging students in inquiry and wonder about words. Dip into her book for tools to .assess and group students for effective instruction .engage them from the start in smart work study .help students learn high-frequenc words, rules, patterns, and spelling demons.align your teaching with school, district, state and national mandates. Read Marten and craft a word study program that turns your students into more than good spellers - they’ll be fine word crafters.

0-325-003220X / 2003 / 176 pp / $18.50

Don’t just read about it, implement Cindy Marten’s approach with her online course: Beyond the spelling Workbook: Crafting a Program to Meet Student Needs.

Special offer through December 31, 2003: Purchase book and course together and receive 20 % off the course fee!

www.heinemann.com

Call 800.225.5800, fax 603.431.2214, or write: Heinemann, P.O. Box 6926, Portsmouth, NH 03802-6926

It’s more than an online assessment... it’s a new way of seeing student progress.

ONLINE FAMILY FROM IOKNOW PROGRESS ONLINE REPORTING SYSTEM CTB/MCGRAW-HILL...

Target instruction | Meet instructional | Select pre-made tests | Meet AYP with fast and | goals with aligned | or use item banks for | requirements with reliable feedback | content | optimum flexibility | longitudinal reporting

Contact us today for special introductory packages, go to www.ctb/iknowpromo or special online offers. Call 888.282.5690 for your CTB/McGraw-Hill Evaloation Consultant

Or contact Customer Services 800.538.9547

COPYRIGHT 2003 BY CTB/MCGRAW-HILL LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Mcgraw-Hill Companies

The Journal of the Elementary Section of the National Council of Teachers of English Published since 1924.

Coeditors

Kathy G. Short, University of Arizona, Tueson, AZ

Jean Schroeder, Tueson Unified School District, AZ

Gloria Kauffman, Tueson Unified School District, AZ

Sandy Kaser, University of Arizona, Tueson, AZ

Department Editors

Barbara Bell, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC

Zhihui Fang, University of Florida Gainesville, FL

Danling Fu, University of Florida Gainesville, FL

Darwin Henderson, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

Angela M. Jaggar, New York University, New York, NY

Lester Laminack, Western Carolina University, Cullowhere, NC

Linda Leonard Lamme, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Field Consultants

Marilyn Carpenter, Eastern Washington University, Spokane, WA

Linda Labbo, Universityof Georgia, Athens, GA

Richard Meyer, Universityof New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

Karen Smith, Arizona University, Tempe, AZ

Santa Barbara Classroom Discourse Group: Sabrina Tuyay, Ana Floriani, Judith Green, Carol Dixon, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA

Language Arts Cadre, Tueson, Arizona

Tuesom Unified School District: Cheri Anderson, Stacie Cook

Emert, Richard Foester, Leslie H. Khan, Kelly Langford, Lisa Langford, Julia Langford, Julia Lopez-Robertson, Rebecca Rico

Montano, Barbara Peterson, Lafon Phillips

Catalina Foothills School District: Abigail Foss, Tracy Smiles

Editorial Review Board

Carl Anderson, Teachers College Reading & Writing Project, New York, NY

Kathryn Au, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI

Joyce M. Bainbridge, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Betty Shockley Bisplinghoff, University of Georgia, Athens, GA

Randy Bomer, The University of Texas, Austin, TX

Lois Brandts, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA

Valerie Brown, John H. Hamline Elementary School, Chicago, IL

Aimee Buckner, Brookwood Elementary, Snellville, GA

Kelly Chandler-Olcott, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY

Ward Cochrum, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ

Ralph Cordova, Goleta Union School District/University of California, Goleta/Santa Barbara, CA

Amy Donnelly, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

Catherine Dorsey-Gaines, Kean University, Union, NJ

Kim Douillard, Cardiff Elementary School, San Diego, CA

Curt Dudley-Marling, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA

Joel E. Dworin, The University of Texas, Austin, TX

Michele Ebersole, Waiakrawaena Elementary, Hilo, HI

Patricia Enciso, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Off

Cecilia Espinosa, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ

Janet Evans, Liverpool Hope University, Liverpool, England

Zhihui Fang, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Ralph Fletcher, Author/Consultant, Lee, NH

Carolyn Frank, California State University, Los Angeles, CA

Linda Gambrell, Clemson University, Clemson, SC

Celia Genishi, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY

Carol Gilles, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

Dierdre Glenn Paul, Montclair State University, Upper Montelait, Mary Louise Gomez, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

Marjorie R. Hancock, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS

David Hornsby, Curriculum Consultant, Melbourne, Australia

Louise Jennings, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

Douglas Kaufman, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Allen Koshewa, Lewis & Clark College, Portland, OR

Linda Leonard Lamme, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Mitzi Lewison, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Dan Madigan, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH

Prisca Martens, Towson University, Towson, MD

Carmen Martinez-Roldán, The University of lowa, lowa City, IA

Amy A. McClure, Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, OH

Marilyn McKinney, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV

Shirley McPhillips, Literary Consultant, Dumont, NY

Jane McVeigh-Schultz, Abington Friends School, Jenkintown, PA

Carmen L. Medina, Indiana University, Purdue University, Indianapolis, IN

Mary Beth Monahan, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC

Pamela Murphy, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY

Sharon Murphy, York University, Toronto, ON

Jodi Nickel, University of Western Ontario, London, ON

Sylvia Pantaleo, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC

Jann Pataray-Ching, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA

Leslie Patterson, University of North Texas, Denton, TX

Rise M. Paynter, Templeton Elementary School, Bloomington, IN

Bertha Perez, The University of Texas, San Antonio, TX

Katherine Mitchell Pierce, Clayton School District, Clayton, MO

Debbie Reese, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL

Laura Robb, Powhatan School, Boyce, VA

Wayne Serebrin, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. MB

Laurence Sipe, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Karen Smith, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ

Karen P. Smith, Queens College, Flushing, NY

Diane Stephens, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

Dorothy Strickland, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ

Anna Sumida, Kamehameha Schools, Honolulu, HI

Denny Taylor, Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY

Charles A. Temple, Howard & William Smith Colleges, Geneva, NY

Deborah L. Thompson, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ

Richard D. Thompson, Canyon Elementary School, Hungry Horse, MT Rick Traw, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA

Ann Trousdale, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA

Jan Turbill, University of Wollongong. Wollongong, NSW, Australia

Sheila Valencia, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Vivian Vasquez, American University, Washington, DC

Constance Weaver, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI

Phylis Whittin, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI

Kathryn F. Whitmore, The University of lowa, lowa City, IA

JoAnn Wong-Kam, Punahou School, Honolulu, HI

Vicki Zack, St. George’s Elementary School, Montreal, QC

NCTE Executive Committee

David Bloome, Patricia Lambert Stock, Randy Bomer, Leila Christenbury, Katherine Bomer, Tonya Perry, MaryCarmen Cruz, Kathryn Mitchell Pierce, Curt Dudley-Marling, Katherine Ramsey, Rebecca Bowers Sipe, Pat Graff, Patricia Harkin, Rudolph Sharpe. Jr., Shirley Wilson Logan, Kathleen Blake Yancey, Jody Millward, Dawn Abt-Perkins, Stephen Hornstein, Erika Lindemann

Elementary Section Steering Committee

Katherine Bomer, Ralph Cordova, Aurelia de Silva, Curt DudleyMarling, Shari Frost, Isoke Nia, Kathryn Mitchell Pierce, Richard D. Thompson, JoAnn Wong-Kam

Editorial Assistant

Rebecca Ballenger

Photographer

Joel Brown

Production Editor

Carol E. Schanche

The Language Arts editorship is a collaboration between the University of Arizona and Tucson Unified School District.

Language Arts (ISSN 0360-9170) is published bimonthly in September, November, January, March, May, and July by the National Council of Teachers of English. Annual membership in NCTE is $40 for individuals, and a subscription to Language Arts is $25 (membershin is a prerequisite for individual subscriptions). Institutions may subscribe for $75. Add $8 per year for Canadian and all other international postage. Single copy: $12.50 (member price,$6). Remittances should be made payable to NCTE by credit card, or by check, money order, or bank draft in U.S. currency. Orders can also be placed toll-free at (877) 369-6283 or online at www.ncte.ong. Communications regarding orders, subscriptions, single copies, and change of address should be addressed to Language Arts, NCTE, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801-1096. Communications regarding permission to reprint should be addressed to Permissions, NCTE, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801- 1096. Communications regarding advertising should be addressed to Carrie Stewart, NCTE, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801-1096

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Language Arts, NCTE, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801-1096. Periodical postage paid at Urbana, Illinois, and at additional mailing offices. Copyright

Language Arts publishes original contributions on all facets of language arts learning and teaching, focusing primarily on issues concerning children of preschool through middle school age. To have a manuscript considered for publication, submit & copies of your manuscript to the Editors. Authors outside of the United States and Canada may submit electronic copies of manuscripts Be sure to include an e-mail address with your manuscript. Manuscripts are usually approximately 20 pages (6500 words) or less in length (including references). Manuscripts should be double-spaced in 12-point font and should have 1” margins. Photo essays must include black-and-white photographs. Please include charts, graphs, children’s artifacts, bulleted points, and/or figures wherever possible to vary the format and en- hance the content of the article. We also encourage the inclu sion of children’s voices where appropriate in manuscripts. Send copies, not original figures, photographs, or samples of chil- dren’s work with your initial submission. Such materials will be requested later if the manuscript is accepted for publication.

All manuscripts should be prepared according to the style specified in the 5th edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association with the following excep- tions: a) a 25-50 word abstract of the manuscript; b) the run- ning head information need only appear on the cover page; and c) endmatter should be ordered as follows-Author’s Note, Children’s Books Cited (only for cases in which there is a lengthy children’s book list), and References. Do not use foot- notes or endnotes. Should a manuscript contain excerpts from previously published sources that require a reprint fee, the fee payment is the responsibility of the author. Each manuscript should include a cover sheet containing the manuscript title, a running head and the author’s name, affiliation, position, preferred mailing address, e-mail address, telephone number(s), and fax number. Identifying information should not appear elsewhere in the manuscript in order to ensure impartial review. Manuscripts are reviewed anonymously by at least two members of the Editorial Review Board. All submissions are acted upon as quickly as possible. However, because of the themed nature of Language Arts, a final decision about a manuscript may take as long as a year. Usually decisions are made within 5 months. Edi- torial correspondence and manuscripts should be directed to:

Language Arts Editorial, 515 College of Education, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721.

E-mail: langarts@u.arizona.edu

The current sociopolitical contest provides an unprecedented Copportunity to promote early literacy, Although everyone agnes on the significance of early literacy lonstruction, what gets pin moted is highly dehated. The press, legislators, and national re ports focus on academic approaches that emphasize direct instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics. At the same time, carly childhood educators focus on authenticity, experien tially-based pedagogy, and literacy learning through play. We invite articles that focus on cutting-edge work in early literacy What are authentic literacy experiences for young children? (Submission deadline: November 15, 2001)

May

The current trend of devaluing teachers has resulted in the re duction or ellmination of long-term professional development opportunities in many school districts. Professional inquiry about literacy and instruction are often replaced with one-size- fits-all inservices focused on the implementation of scripted teacher-proof materials, rigid procedures, and packaged pro grams. These inservices are delivered so teachers can meet formal, high-pressure goals, rather than develop knowledge and curriculum. We believe that in order to create and sustain pro- ductive learning conditions for students, these same conditions for professional learning must exist for teachers, Professional study invites teachers to act, talk and reflect over time to con struct theories of literacy learning based on their experiences and knowledge. Now, more than ever, we need to explore alter- native approaches to inservices that treat teachers as profes sionals who are lifelong learners, nor technicians. We invite manuscripts focusing on innovative professional development approaches to literacy instruction. These approaches might be particular professional development models coming out of other fields, such as the Japanese Lesson Study or Critical Friends Groups, as applied to literacy, or strategies for professional study and curricidum development that literacy educators have created in their own contexts. We are interested in appmaches where the sitimate goal is developing thoughtful professionals who can assess and revne their own actions to improve the literacy karming of their students, rather than creating individuals who unthinkingly follow a cookbook appmach to traching Submission deadline: January 31, 2004)

July 2005:

This unthemed issue will feature ongoing work in theory, research, and/or practice that is part of current explorations in the field of language arts. These articles could include cat ting-edge work or a revisiting of continuing projects and lin gering issues. What are your current questions? exploration gerimalies? projects? What are you passionate about? What causes you tension in the field of literacy today? What are you thinking about and working on? Although Language Ant is normally themed, this issue of the journal provides an op portunity for educators to submit articles about their own current work in literacy and language arts. This is your chance to write about your work without being confined to particular theme. What would you like to share with other language arts educators? (Submission deadline: March 31, 2004)

September

The past ten years have been difficult ones for educators whe are committed to bringing books and children together in thoughtful ways. Most students now find themselves in iso- lated “skill and drill” boot camps for reading instruction. Ther is little time for meaningful engagement with story and litle space for real books. Although the current political context is grim, many educators continue their work in using authentic. well-written pieces of literature to create communities of read ers who experience the joy of reading. These educators View children as readers of books, not consumers of commercial materials. The surface features of their classrooms may have changed as a survival mechanism, but the deep structure of their teaching remains the same as they continue to search for meaningful ways to bring children and books together. In this issue, we invite articles that celebrate the ways in which litera ture can add connection and significance to children’s lives.These articles might highlight issues related to specific engage ments that support students in connecting with books, such as read-aloud, independent reading, choral reading, readers the atre, book share, or literature discussion and response. Another emphasis could be connections between literature and the arts or with other areas of the curriculum. The focus might be on joyful engagements with literature or critical examinations of multicultural, multilingual, and global issues through litera ture. Another possibility is a focus on issues within the field of children’s literature, such as trends in publishing, an analysis of a particular group of books, or a discussion of the creative processes of writing, illustrating, and publishing books. We arr Interested in articles about classrooms where teachers and chil dren are resisting increasingly narrow and restrictive views of literature and are persisting in their cutting-edge work.

(Submission deadline: May 31, 2004).

September

The past ten years have been difficult ones for educators who are committed to bringing books and children together in thoughtful ways. Most students now find themselves in iso- lated “skill and drill” boot camps for reading instruction. There is little time for meaningful engagement with story and little space for real books. Although the current political context is grim, many educators continue their

work in using authentic, well-written pieces of literature to create communities of read- ers who experience the joy of reading. These educators view children as readers of books, not consumers of commercial materials. The surface features of their classrooms may have changed as a survival mechanism, but the deep structure of their teaching remains the same as they continue to search for meaningful ways to bring children and books together. In this issue, we invite articles that celebrate the ways in which litera- ture can add connection and significance to children’s lives. These articles might highlight issues related to specific engage- ments that support students in connecting with books, such as read-aloud, independent reading, choral reading, readers’ the- atre, book share, or literature discussion and response. Another emphasis could be connections between literature and the arts or with other areas of the curriculum. The focus might be on joyful engagements with literature or critical examinations of multicultural, multilingual, and global issues through litera- ture. Another possibility is a focus on issues within the field of children’s literature, such as trends in publishing, an analysis of a particular group of books, or a discussion of the creative processes of writing, illustrating, and publishing books. We are interested in articles about classrooms where teachers and chil- dren are resisting increasingly narrow and restrictive views of literature and are persisting in their cutting-edge work.

(Submission deadline: May 31, 2004).

Teachers, researchers, and theorists have grown up in a world radically different from that of the children they study and teach. While educators tend to focus on books, texts such as video games, movies, Web sites, television programs, and music often carry the most meaning for students. Finding meaning in students’ im- mediate experiences through engagements with all Forms of literacy has the potential to bring “kid culture” into schools. This issue includes a range of articles that explore the significance of everyday literacies as they intersect with children’s lives and with school literacy. Superheroes are popular culture icons that connect across generations. The multiethnic superheroes of both genders that soar across our cover reflect the increasing diversity in popular culture images available to children today.

These comic-book superheroes are found in 1, 2, 3 Pop!, a counting book that uses kid-friendly images, pop art, and dialogue balloons to reflect the high-energy playful- ness that popular culture brings to children’s lives.

When we wrote the call for manuscripts, we assumed that this issue would feature articles connecting popular culture with curriculum. We quickly realized, however, that educators need to first understand the complexity of children’s thinking as they participate with popular cul- ture texts before considering instructional implications. The first four articles are close observations of the multi- ple literacy texts and strategies that children use as they interact with popular culture both in and out of school.

Anne Haas Dyson argues that all children bring knowledge and skills gained from their everyday lives to school, but that the current emphasis on pedagogical uniformity ignores children’s experiences with popular media texts. Donna Mahar was drawn into a lunchtime group in her classroom that formed a cultural identity around their devotion to anime. She examines the strate- gies they used to teach her about the rules of gaming and the genre of fanfics. In contrast, Vivian Vasquez explores the highly complex literacies that a young boy uses as he teaches himself the codes (the ways of talking and doing) associated with the Pokémon world. Julie Wollman- Bonilla analyzes the composition of e-mail messages, one kind of everyday literacy currently available to children, through a case study of a six-year-old child. Daniel Hade and Jacqueline Edmondson take us a step back from observing children to considering the broader world within which children function, specifically the marketing of children’s books. They argue that the cor- porate goal is not to sell as many books as possible, but to push a specific book into as many different product lines as possible. The idea is not to read, but to consume. Donna Alvermann and Shelley Hong Xu return us to the classroom by providing a description of four approaches to using popular culture in the curriculum. They offer teaching suggestions and consider the conflict inherent in teachers trying to develop children’s critical aware- ness of the very things that children find most pleasur- able about popular culture.

Carmen Luke offers a list of further professional readings on popular culture and media literacy. Danling Fu, Linda Lamme, and Zhihui Fang review three books that demon- strate the power of children’s minds and intellects in me- diating their world and school literacies. The 2003 Orbis Pictus Committee highlights the Orbis Pictus award win- ners and other outstanding nonfiction for children. Fi- nally, the Profile by Dorothy Strickland and Lee Galda features Bernice Cullinan, this year’s recipient of the NCTE award for Outstanding Educator in the Language Arts.

The key tension for us after reading these articles is moving from careful observation of children’s thinking about popular culture texts into thoughtful pedagogy. One danger is reducing popular culture to trite activities designed to get children’s attention, but which actually devalue the culture through surface connections. An- other danger is insisting that children critique their pop- ular culture worlds through an adult lens to persuade them that these worlds are bad or a waste of time. We realize that a critical study of popular culture may be an unwanted intrusion into student’s lives that widens, not bridges, the gap between teachers and children. The stance we want to take as educators is that of inquirers who recognize and value the complexities and potentials of children’s everyday lives and literacies.

The assumption that “diverse” children come to school without literacy ignores the resources they bring from popular media texts.

-Anne Haas Dyson“I’m mad and I followed the drinking god.”

-Denise (age 6. first grade)

Six-year-old Denise is potentially one of those “all” children. Often written with a graphic wink, “all” is sometimes knowingly underlined or righteously capitalized, and it is almost always syntactically linked or semantically associated with that other category, the “different” children-not middle class and not white literacy education, these concerns about the “all” children are often undergirded by what might be called the “nothing assumption- The decision to mike no assumption.

that children have any relevant knowledge. The “all” children are in urgent need, so the argument goes. of a tightly scripted, linear, and step-by-step monitored march through proper language awareness, mastery of letters, control of sound/ symbol connections, and on up the literacy ladder.

In response, I offer an account of school literacy development for all children. This account does not depend on the assumption of “nothing,” nor on an idealized. print- centered childhood. Rather, it

In literacy education, these concerns about the “all” children are often undergirded by what might be called the “nothing” assumption the decision to make no assumption that children have any relevant knowledge.

depends on the assumption that children will always bring relevant resources to school literacy. That is, there will always be local manifesta- tions of true childhood universals- an openness to appealing symbols (sounds, images, ways of talking), and a playfulness with this every- day symbolic stuff.

This account of literacy development is based on an ethnographic study of Denise and her close school friends, all first graders in an urban public school (Dyson, 2003). I studied their childhood culture, documenting their cultural practices-their talk, singing, collaborative play-and the symbolic stuff with which they played. The children had a wealth of textual toys, of free symbolic stuff to play with. They found those toys in the words and images of parents, teachers, teenagers, and other kids, as well as on radios, TVs, videos, and other everyday forms of communication.

The children not only manipulated or played with their everyday symbolic stuff in the unofficial or peer world, they stretched, reorganized, and remixed this material as they entered into official school literacy.

In this article, I use a metaphoric drinking god to capture the influence that children’s nonacademic textual experiences have on their entry into school literacy. That influence may leave us as educators without the proper frame of reference for build- ing on children’s efforts. Moreover, any desires we may have for peda- gogical uniformity cannot withstand the power of the drinking god. That “god of all learning children” messes up any unitary pathway, renders visible the multiple communicative experiences that

may intersect with literacy learning, and bequeaths to each child, in the company of others, the right to enter school literacy grounded in the familiar practices of their own childhoods.

Before explaining this approach for all children, I need to do some stage-setting by discussing the “all and nothing” assumption in early literacy pedagogy and its relationship to the desire for uniformity and order. I formally introduce the metaphoric drinking god and briefly describe my study methods. Then I allow the children-and the drinking god-center stage. To clarify my view, I link it to that of Marie Clay, an important scholar who took an early stand against uniformity.

In my former California locale, discontricts have been turning to state-approved reading programs designed with the “all” children in mind. The design rests on the assumption that the “all” children bring nothing, as suggested by the following quotes, the first from the program’s Grade 1 Teachers Guide (Adams, Bereiter, Hirshberg. Anderson, & Bernier, 2000):

As society becomes more and more di- verse and classrooms become accessi- ble to more and more children with special needs, instruction must be de- signed to ensure that all [sic] students have access to the best instruction and the highest quality materials and are subject to the same high expecta- tions.. Diverse and individual needs are met by varying the time and intensity [but not the means) of in- struction. (p. 12F)

The second quote comes from the program’s Web site (SRA, 2000, p. 1):

[The program] is designed such that no assumptions are made about stu- dents’ prior knowledge; each skill is systematically and explicitly taught in a logical progression, to enable understanding and mastery.

These quotes suggest that the noth- ing assumption for the “all” children is not about sociocultural variation in children’s experiences with liter- acy, in their ways of communicating with adults and peers, or in the nature of their everyday worlds and, thus, their everyday knowledge (Genishi, 2002; McNaughton, 2003; Nieto, 1999). The nothing assumption rests on a concern that “di- verse” children are more apt to come to school without literacy skills.

The nothing assumption recalls the concern in the sixties

for the “cul- turally disadvantaged.” In their professional text on “teaching dis- advantaged children,” Bereiter and Englemann (1966) portray teaching reading skills as a means of over- coming the assumed linguistic barrenness (the nothingness) of children’s everyday lives. The potentially unruly disadvantaged children are contrasted with the “culturally privileged ones.

The latter children’s assumed language- rich life allows them to come to school, if not with everything, at least with some awareness of words and the alphabetic principle.

This contrast between the ideal chil dren developing literacy and the racialized and classed other children lacking resources has assumed new prominence. Government-backed literacy “science” has made teaching the “all” children a matter of equity (Schemo, 2002). Organize manage able hits of literacy knowledge into a sequenced curriculum and teach it directly to orderly children-and do so as early as possible. No time to waste. Al, but the rub is the chil- dren themselves, whose sociality is among the worst enemies to what we call teaching” (Ashton-Warner. 1963, p. 1031.

School brings many children together in one space. And those children de velop social bonds and playful prac tices linked to, but not controlled by, adults. In other words, children have minds and social agendas of their own. And, in I illustrate below, it is the metaphoric drinking god that wields power over the children and leads them to play “the very devil with orthodox method” (AshtonWames, 1963, p. 103).

I first met the drinking god when he was invoked by Denise as she worked on a task in her first- grade classroom:

Denise has just participated in a class lesson blending a study of the artist Jacob Lawrence with a study of the underground railroad-that net-work of pathways and dwellings through which slaves escaped from the southern U.S. to freedom in Canada. The lesson centered on slides of Lawrence’s paintings of Harriet Tubman, an escaped slave who led many others to freedom. During the lesson, Rita, the teacher, discussed with the children Lawrence’s use of the North Star, which guided the people, and, also the star’s location in the constellation called the Drinking Gourd or, alternatively, the Big Dipper. Over many days to come, Rita and the children would sing and study the

words to Pete Seeger’s er sion of “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” Now that the lesson is over, Denise and her peers are to show whar they’ve learned. And so, sitting side-by-side. Denise and her good friend and “fake sister” Vanessa, both African American, draw their versions of a muscular Harriet Tubman chopping wood, tears streaming down her face. As she draws, Denise becomes Harriet Tubman, writing “Denise That’s me” on her drawn image and, then, adding the statement, “Tom mad and I followed the drinking god.”

The drinking god. Mmmm. Usually a quiet observer, I intervene and ask Denise if she means the “drinking gourd.” “It’s drinking god,” she says definitively.

Vanessa agrees. Some people say “god,” some say “gourd. Duk!” Un- daunted, I persist:

Dyson: What does this god do? [very politely]

Denise: He makes the star for them to follow...

Dyson: Why did Harriet Tubman follow the drinking god?

Denise: She was a slave.

Vanessa: If she sung a song, her friends would love her. What’s that song? (recollecting a tune)

And soon an R&B song learned from the radio arises from Denise and Vanessa’s table.

With this vignette, I formally introduce the drinking god factor-the factor that becomes evident when one assumes that children bring, not nothing, but frames of reference (i.e., familiar practices and old sym- bolic stuff) to make sense of new content, discursive forms, and symbolic tools. As they participate in the official school task of composing “what I learned,” Denise and Vanessa blend resources from varied it is a serious error to assume that any child brings nothing to new experiences. Indeed, all reputable developmental accounts assume that nothing comes from nothing.

experiences, including those they shared as collaborative child players, churchgoers, participants in popular culture, and attentive young students. They know, for example, that music is a symbol of affiliation, not only for them (“What’s that song we both know?”), but also for Harriet Tubman and other conductors on the Underground Railroad (“Let my people go”). And they know that people speak different varieties of English-

people’s voices have different rhythms and rhymes, different ways of drawing out or cutting short sounds; such language variation is an official topic in sound/ symbol lessons and in literary ones in their room, but not a topic in the first-grade pro- grams for the “all” children, who are to speak in uniform ways.

Given the power of the drinking god, it is a serious error to assume that any child brings nothing to new experiences. Indeed, all rep-utable developmental accounts assume that nothing comes from nothing. Any learning must come from something, from some experimential base that supports participa- tion and sense-making in the designated learning tasks (Piaget && Inhelder, 1969; Vygotsky, 1962).For Denise and her friends, that base comes from their everyday lives in a complex social landscape like that theorized by Bakhtin (1981, 1986). Their landscape is filled with interrelated communication prac- tices, involving different kinds of symbol systems (e.g., written lan- guage, drawing, music), different technologies (e.g., video, radio, ani- mation), and different ideologies or ideas about how the world works.

The children experience these practices as kinds of voices (Hanks, 1996)-the voices, say, of radio dee- jays and stars, sitcom characters, and oft-heard poets, of sports announcers, preachers, teachers, and teenagers, and on and on. So, in my research project, I studied how children used their experiences participating in all these practices for their own childhood pleasures and for school learning. That is, I studied the recontextualization processes (Bauman Et Briggs, 1990; Miller & Goodnow, 1995) through which they borrowed material from these practices, translated it across and reorganized it within childhood play practices, and, also, official school literacy ones.

The children’s school was an urban elementary school in the East San Francisco Bay. Denise’s teacher, Rita, was highly experienced, having begun teaching in the London primary schools of the 60s. Rita’s curriculum included both open-ended activities, such as writ- ing workshop, where the children wrote and drew relatively freely, followed by class sharing, and more teacherdirected ones, such as as- signed tasks in study units, in which children wrote and drew as part of social studies

and science learning.

I spent an academic year in Rita’s room studying the childhood cul- ture enacted by a small group of first graders, all African American, who called themselves “the broth- ers and the sisters”-and they meant that quite literally; they pre- tended to have a common Mama. The children were Denise, Vanessa, Marcel, Wenona, Noah, and Lakeisha. I observed and audio- taped them on the playground and in the classroom, particularly during composing activities, and I also interviewed their parents. As the work progressed, I realized how much the popular media in- formed the children’s world. From their experiences with the media, children formed interpretive frames-or understandings of typi- cal voice types or genres. And within those varied kinds of voices, they found much play material, in- cluding conceptual content; models of textual structures and elements: and a pool of potential characters. plots, and themes.

Studying how the children used this material in official (or school- governed) as well as unofficial (or child-governed) words resulted in

I observed the children sampling symbolic material from the communicative practices-the varied kinds of voicesthat filled the landscape of their everyday lives.

This account of literacy development. Because of space constraints, I focus on a key event from Marcel’s case, although I allow Denise some time in the spotlight as well.

Fittingly enough, as I tried to articulate an account of literacy development grounded in the project’s particulars, I turned to a major source of the children’s textual toyship hop. Hip hop, in factm is about “making something out of nothing,” I heard that explanation more than once from the hip hop practitioners, whom I consulted in the course of this project. As they explained, rap was born during a time when public funds for education and for youth programs were slashed and public distrust of youth was heightened. Som informed by cultural traditions that stretch back through time, urban youth took their used cultural stuff and old technologies and transformed them into flexible modes of epression (Yerb Buena Center for the Arts, 2001; Smitherman, 2000). They made a drum out of a turntable, a style of dancing out of karate kicks, a storyteller out of a chanter. They created something, if not out of nothing, at least out of some things that

might not originally have been seen as innovative, creative, and generative. This notion of material that might be seen as “nothing” becoming “something” seemed to capture the essence of my project, I observed the children sampling symbolic material from the communicative practices-that varied kinds of voices that filled the landscape of their everyday lives. Analogous to rap artists, the children appropriated and adapted this material as they constructed their unofficial and playful practices. Moreover, like producers who remix musical compositions, they adapted that old textual stuff to the new heats re quired in official literacy spaces.

The children’s sampling and remixing their recontextualization processes-opened up literacy pathways to their resources from diverse communicative practices I do my own textual sampling to illustrate these processes as co acted in children’s unofficial and official worlds

Like her fake siblings. Denise found many of her textual toys on the Bay Area’s leading hip hop radio station. In her recess radio play, she and her lake siblings deconstructed that station into a set of diverse and interrelated kinds of practices, of voices.

The children’s sampling and remixing-their recontextualization processes-opened up literacy pathways to their resources from diverse communicative practices.

For example, in radio play, Denise did not simply sing. She became a kind of singer-a rapper, a soul singer. Moreover, she could situate singers in relationship to others fe.g. deejays, audience members) and to varied interrelated radio practices (song announcing, radio interviews), She had a sense of the landscape of practices of voices-upon which she was playing; and she could flexibly manipulate words, phrasing, intona thon, even speaking turns as the situ ation required. Listen to a hit of playground radio play, as Denise in terviews herself Denises framing a polite, interested inet Dewise. Tell us, why

Denise: Do you like to sing and your friends? Frapping! We want to be a star / In the store We want to be on stage/ For our cage

For Marcel, sports media was a favored source of textual play materials. He and Wenona and Noah enacred a relational world of coaches, teammates, and rivals. The children had a demanding schedule: their coach was based both in Minnesota (where he had a coed hockey team, the Mighty Ducks, based on a movie of the same namel and in Texas (Dallas, Texas, to be exact, where he coached the Cowboys, a professional football team).

The children’s sports play, like railio play, involved a range of in- terrelated practices that included. first, planning agendas that allowed time for practice sessions, travel to varied destinations foften across state lines), habysitting for relatives, and homework: second. narrating highlights of previous games, featuring themselves; and, third, evaluating the relative merits of teams. And, like professional sports broadcasters. Marcel and his friends made much use of adverbs of time and place. Listen as Marcel and Wenona discuss up-coming events:

Wenona and Marcel are sitting ta gether furing a morning work period. Thes are doing their wurk in the official world, but they are also doing their “work” in the wwofficial warhl Bie, planning their upcoming schedule):

Wenona: You know I’m thinking about going over to la rela tive’s house today but we gutta play gumes. I forgat We playing hockey Today soe pürsing hockey

Martel: Cause we gotta play hockey (agreeing)

Wenna: In Los Angeles- no-

Marcel: It’s in Los Angeles. [affirming]

Wenona: It’s in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles

Marcel: I forgot. We gotta play Pittsburgh

Wenona: In Pittsburgh

Marcel: Pittsburgh is real weak.

“In Pittsburgh,” said Wenona, emphasizing the preposition in and thewby, the distinctio Бетите а city location and a city tram ba smilar way, the children sometimes played “Minnesota (pause) in Mis mesota” or “Dallas fped in Dall In the children’s play, Dallas always won, but that was not the case when Marcel engaged in spurte chat with other boys. He, Samel, and Zephe

nia often repeated foochall scores te rach other after an opening. “Did you see the game?” And, in that practier, Dallas could lose. Like Denise, then, Marcel’s playful practices evidenced his hortowing and revoicing of we bolic material from a landscape of possibilities. He flexibly manipulsed textual material (including scoresi in different ways, depending on the social situation he was in).

In official school activities, too. children borrowed from their land scape of possibilities. Their remixing processes displayed the drinking god’s power-the power of these un expected frames of reference-to create hoth onder and havoc. On the one hand, these frames guided children’s agency, their decision- making about how in manipulate the elements of the written system its letters, words, syntax-to accom pish sume end. On the other hated they posed very useful symbolis social, and ideological challengesa they moved across symbol systems

and social worlds with different ex- pectations and conventions.

I aim to describe how, energized and guided by the desire for social participation, children use old resources from familiar practices and adapt them to enter into new ones.

Before I illustrate this official remixing with an example from Marcel, I engage in a little textual play of my own. I link this “remix” approach to an earlier nonlinear view of literacy development, that of Marie Clay. In this way, I hope to clarify what the remix view may add to the repertoire of ways of un- derstanding child literacy..

My textual play: Situating Clay’s “kaleidoscopic reshuffle.” Beginning most notably with What Did I Write? in 1975, Clay has detailed a con- structivist view of written language development. In this view, children must take control over the written medium, learning to direct and mon itor its use in producing and receiv Ing messages. Unlike many other developmental views emerging in the seventies, Clay did not reduce early composing to spelling nor did she posit “stages” of learning. Based on close observation of the ways of writing for children entering New Zealand schools, Clay analyzed how children engage with written lan- guage as a complex system, at first “in approximate, specific, and what seem to be primitive ways and later with considerable skill” (p. 19).

Children’s first efforts may suggest the idiosyncratic and varied bits of knowledge that they have accumu lated from diverse experiences with print in families and communities: among such knowledge may be letter forms, written names, perhaps a sense of how certain kinds of print sound when read. When they re- spond to school literacy taskes, chil dren orchestrate their knowledge and know-how to construct basic concepts about print the nature of signs, page arrangement, directionality, voice/print match. Flexibility in child response is important because rigid early learning may keep chil- dren from adapting their understandings as new literacy tasks are faced. Clay (1975) notes, “Chance experi- ences may produce new insights at any time” (p. 71. Hence, her “kaleido- scopic reshuffle-the reworking of children’s understandings of a com plex, multilayered system (1998).I entered the child literary conver sation at a different time and with different conceptual tools-more sociolinguistic, sociocultural, and folkloric than psychological, like Clay’s. Given those tools, I aim to situate Clay’s cognitive reshuffle within a social notion of commu- nicative practices. That is, I aim to describe how, energized and guided by the desire for social participa tion, children use old resources from familiar practices and adapt them to enter into new ones. Thus, their pathways into school literacy are found in the converging and diverg- ing trajectories of practices. The ideal developmental outcome of these processes is not only flexibil- ity and adaptability with written conventions but also with symbol systems and with social conven- tions. To illustrate, I turn to a key event from Marcel’s case. Marcel re-mapping his words and worlds. Marcel is sitting by Lakeisha on one side and a parent volunteer, Cindy, on the other. Lakeisha is his fake sister and un derstands that he plays for a win ning team-Dallas. Indeed, Marcel tells her that he is planning to write about Dallas. Through his text, Marcel will enact a familiar practice-reporting his team’s triumphs. His planned text is thus sit uated at least partially in the child- hood world he shares with Lakeisha.

Marcel: (to Lakeisha) I know what I want to write about. “The Dallas Cowboys[beat] Carolina.”

Cindy: They (Dallas) lost. Did you watch the game?

The adult Cindy corrects the child. Marcel She is not, after all, a rela tive, she views Marcel as a little boy who has the facts about Dallas’s fate in the football playoffs wrong. She Initiates a different practice-a “Did- you-watch-the-game?” practice. Marcel can participate in this practice as well:

Marcel: They’re out! Out of the playoffs?

Cindy: They’re like the 49ers now.

Marcel changes his plans. He still starts with The Dallas, then stops, gets the classroom states map for spelling help, and begins to copy

Minnesota, whom Dallas had beaten the previous week (see Figure 11.)

Marcel: (to the table, generally as he looks at the map) It’s got all the states right here.

(to himself as he writes Min- mesota) Minnesota, Min- nesota, Minnesota, Minnesota to the city of dreams. Minnesota, Minnesota, Min- nesota, to the city of dreams. (pause) Dallas, Texas. Dallas, Texas. Dallas, Texas.

(to the table) This has all the states, right here. I have all the states, right over here

I’m writing “Dallas ogatest Minnesota.”

Marcell then recites “Dallas, Texas” several more times before writing “in Texas.”

Marcel: It [the score)-it was, 15-no 15 to 48.

Marcel: (to Cindy) This says, “Dallas against Minnesota. In Texas. 15 to 48.”

Marcel has recalled the exact score. He does come to school, after all, quite prepared to participate in the “Didyou-watch-the-game?” prac-tice. He simply had not been planning to participate in that one. And, in fact, he now slips back into the fictionalized world of team players and fake siblings that he shares with Lakeisha.

Marcel: (to Lakeisha) I be home tomorrow, only me and Wenona will be home late. ‘Cause me and Wenona got practice... I still got to go to football practice... Wenona got cheerleading.

Marcel and Wenona will both be home with Mama and Lakeisha tomorrow-but they’ll be late. The Cowboys may be out of the play-offs, but Marcel’s “still got to go to football practice,” and Wenona’s still got to go to cheerleading. In this complexly situated event, you can hear Marcel sample a score-reporting practice of televised sports. And that practice is itself situated within the frame of the children’s unofficial sports play. (Dallas won!) That unofficial frame converges with the official one of writing workshop. This converging of different social practices, with their different uses of symbolic media, yields challenges-potential learning and teaching opportunities-including all those discussed by Clay and more. To begin, you can hear and see the converging of practices when Marcel translates (or remixes) the audiovisual display of sports scores to a paper and pencil display. As Clay might anticipate, Marcel’s event reveals how children have to sort out the nature, and allowable

flexibility, of different kinds of signs, among them letters, numbers, and images. But Marcel is not grappling with “the” set of written conventions-the conventions of these converging practices differ. In school, Marcel is expected to write using letter graph-ics, but, as a sports announcer, Marcel should place team emblems by their names (the Vikings’ horn, the Cowboys’ star). Marcel’s event also highlights Clay’s concepts of directionality and page arrangement. But Marcel’s efforts here are not the result of a child engaging solely with print but, again. of a child recontextualizing written language across practices. Marcel does not follow the left-to-right conventions of a prose report; he arranges team names and scores vertically, as on a TV screen.The converging of different practices is notable too in the complex interplay of what is written and what is read (i.e. voice) print match.

To hear that interplay, you have to know that, in the official writing workshop, Rita emphasized that the children should monitor how their spoken and written words match. And you must know too that the sports announcers’ practice is to read a more elaborate text than the one visually displayed. With those practice details as back. ground information, you can hear Marcel as he shifts voices, precariously positioned between practices. He initially writes The before he writes Dallas, a prose reporting style since he has a sentence planned, “The Dallas Cowboys beat Carolina.” After the parent, Cindy, corrects him. Marcel writes a screen-like display of team names and scores to accurately report the previous week’s play in which Dallas did beat Minnesota.

Between his columns of tear names are the words “in Texas.” which would not be written on such a display, but which an announcer might read. Marcel himself adopts an announcer voice as he rereads hs text to the adult, “Dallas against Minnesota. In Texas. 15 to 48,” In so doing, he reads the unwritten “against,” but not the written the. Beyond these symbolic and discur sive challenges, there are conceptual ones. Marcel grapples with the dis ones. Mael era cities and ste. dinetion betweem ate in team man (e.g., the Minnesota Vikings, the Dallas Cowboys). “This [map] has all the states, right here,” he an-

nounces. Entering into the map-reading practice, Marcel’s articu lated knowledge emerges as the geographic knowledge embedded in football team names is disrupted and reorganized. In a previous event. Marcel had tried unsuccessfully to find “Oakland” [for the Oak land Raiders] on the states map, which led to a discussion about the map with Rita. Then, as if all those challenges were not enough. Marcel confronts the situated reality of “truth.” What is true in the brothers’ and sisters’ world (that Dallas always wins) is not necessarily true in the real Bay Area world. And, finally, there are

Learning to read, or learning anything, for that matter, is actually a process of complex variation.

the gender ideologies embedded in all football-related events, ideologies that could become salient when they entered the official world through whole-class sharing, as they did when Kita led a class discussion about the truth of a child’s assertion that only boys like football. In sum, when Marcel translated eul-tural material (e.g., names, informational displays, kinds of texts, text sequencing conventions) across the boundaries of different practices, the symbolic, social, and ideological knowledge embedded in those practices could be disrupted and brought into reflective awareness, Certainly a childhood practice built with the textual toys of media sports shows is not on anyone’s list of critical early literacy experi-ences. But there it was anyway, evidence of the drinking god factor and of Marcel’s, and children’s, agency in deciding what’s relevunt to literacy tasks. Similar analyses were done for all the brothers and sisters (Dyson, 2003) whose cases are filled with converging and diverging practices. The practices-the typified voices-of hip hop radio, cartoon shows, and popular films all figured-in unexpected but ultimately productive ways-into the written language trajectories of individual children, brothers and sisters, growing up in these voice-filled times.

Institutions serving the “all” children are being urged to reduce literacy to the “basics”-and to reduce early childhoods themselves to a time for reading readiness. And yet, as Anderson-Levitt (1996) comments,

the premise that learning takes place in stages along a

narrow linear path (assumes that... I one could learn more only by progressing further along that path instead of by wandering off the track. This is the same fawed idea that Stephen Jay Gould found at the core of intelligence mea-sures.... He called it the “fallacy of ranking... our propensity for ordering compler variation as a gradual ascending scale” (p. 24). Learning to read, or learning anything, for that matter, is actually a process of complex variation. “Wan-dering off the track” was something the brothers and sisters often did without any intention to do so. They simply did what all learners do-they called upon the drinking god, that is, upon familiar frames of reference and well-known materials, to help them enter into new possibilities.

The very diversity of organized social spaces within which they lived (e.g., families, schools, media events, not to mention the brothers and sisters’ world) mitigated against unilateral control of children’s learning by any one in-stitution. And this was good, as it led to their productive grappling with the symbolic, social, and ideological complexities of written texts and social worlds. This developmental point of view, with its openness to children’s sampling and remixing, should render anemic those views that attempt to fragment written language into a string of skills or to narrowly define the home and community experiences that can contribute to school learning (Reyes & Halcon, 2001).

The message for teaching inherent in this view is deceptively straight-forward-teachers must be able to recognize children’s resources, to see where they are coming from, so that they can establish the common ground necessary to help children differentiate and gain control over a wealth of symbolic tools and communicative practices.

To develop such common ground, teachers like Rita work toward a productive interplay of unofficial and official worlds. For example, through open-ended composing periods, educators can learn about children’s textual toys and the themes that appeal to them. And in classroom forums in which children present their work, teachers can help children name and compare how varied kinds of texts look and sound and, moreover, how and why and even if they appeal to all of them as classroom participants (Dyson, 1993, 1997; Marsh &t Millard, 2000). As children bring unexpected practices, symbolic ma-terials, and technological tools into the official school world, the curriculum itself should broaden and

“run, don’t walk, to get your copy of this book...”

“This book is important or several reasons. First, it is readable, practical, and grounded in real classrooms. Seconds, it is based on powerful theoritical and empirical evidence. And third, and perhaps most important, it is just what we need...given to extent to which children in this country struggle to read informational texts.”

-Richard L. Allington, University of Florida“[The authors] bring the classroom to life with understanting practical suggestions and ideas...My advice to primary teachers is run, don’t walk, to get your copy of this book, which gets at the heart of the excitment and joy of reading and writing informational text.”

-Linda B. Gambrell, Clemson UniversityIncreasingly, research supports the importance of teaching children to read and write informational text, but few resources show how to do it well. This book fills the gap. The authors explain why it’s important to weave informational text into the primary curriculum. From there, they explain how. They provide a framework for organizing your time and space, and share classroomtested strategies for helping children become wise consumers and creator of informational text.

2003 . 0-439-53123-3 . paper . 272 pages . $22.99

“Duke and Bernnett-Armistead know how teachers can use informational text in guided reading and writing, independent reading, sharing and reading aloud, and other aspects of primary-grade instruction... This is a book that teachers will refer to over and over again.”

-Steven A. Stahl, University of Illinois“Nell, Susan, and colleagues really understand classrooms, and they know about informational text. This is a mustread for everyone wsanting to break loose from using narrative texts!”

-Sheila Valencia, University of Washington

To order your copy, call 1-800-724-6527 or fax 1-800-560-6815. SAVE 20% when you mention promo code TFG. Visit the Teacher Store at Scholastic.com.