MA A+U

Copyright @2022 Manchester, UK

All rights reserved Manchester School of Architecture

Copyright reserved by Heena Jameel Ahmed Shaikh

University ID: 21429764

MA Architecture and Urbanism

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

1

A CKNOWLEDGEMENT

I want to thank all the tutors, staff, and students at the Manchester School of Architecture for their constant support and encouragement throughout this journey.

To Prof. Eamonn Canniffe for his consistent support and for sharing a great amount of reading material and sources that helped me build my research.

To Aissa Sabbagh Gomez, my thesis guide, who guided me at each step, making me progress efficiently through my research work.

To my family and friends in India and those, I met during my Architectural journey in the past decade. I have learnt a great deal from all.

Special mention to Architect Rahul Kadri, Mumbai, who has shaped my interest and enthusiasm in the field of Urban planning and design.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

2

A BSTRACT :

The recent pandemic was an eye-opener and made us realise the value of open spaces yet again. An important aspect of city life is the availability of such Public Open Spaces. Cities in India have neglected this aspect due to a preoccupation with building residential and commercial real estate. While shelter remains the priority, we are drifting away from social needs where people can unite and participate with equal opportunities. We often neglect the impact of this deflection that leads to grave physical and mental illbeing. In the absence of playgrounds, parks, and high streets, people will remain inward-looking and find it difficult to interact in the coming times. It is of utmost importance to analyse this aspect of the urban core and provide necessary solutions for enhancing and expanding Public Open Space. This research will focus on the critical study and further provide strategies for enhancing and expanding Public Open Space. As a research context, the city of Mumbai, India, is investigated as the main focus of the discussion. This densely populated metropolitan can further act as a precedent for many other Asian cities with similar backgrounds.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

3

00

Figure 1: An Overview of the Southern tip of Mumbai illustrating its built urban fabric against the coast. (Source: Darren, 2019:Online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

4

C HAPTERS OF C ONTENT :

00. Abstract 03

01. List of Figures & Tables 06-10 02. Abbreviations and Terminologies 11-12

03. Research Overview 13 - 20

a) Introduction b) Aim c) Objectives d) Research Questions e) Research strategy f) Research Methodology

04. What is Public Open Space? 21-33 a) Definition b) Importance and Impact c) Typologies

05. Research Context- Mumbai, India 34-52 a) Introduction b) History- Bombay to Mumbai c) Present day Mumbai

06. Literature Review 53-69 a) Open Mumbai, Re-envisioning open Mumbai b) Formulating open space policies, Mumbai 07. Research Methods (Empirical study) 70-89 a) Case Study- Global comparison b) Case Study- Qualitative evaluation of POS in Mumbai 08. Strategies and Way forward 90-92 09. Conclusion 93-94 10. References 95-99 11. Appendices 100-104

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

5

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES :

Cover Image: Graphics by the author

Figure 1: An Overview of the Southern tip of Mumbai illustrating its built urban fabric against the coast. (Source: Darren, 2019:Online)

Figure 3.1: Overview of the Marine Drive promenade in South Mumbai. (Source: Lloyd, 2017:online)

Figure 3.2: Open Space comparison between major global cities (Source: Paul. F, 2019:online)

Figure 3.3: Diagram showing the considerations for planning the open spaces (Source: Public open space is accessible, protected and enhanced, n.d.: online)

Figure 3.4: Diagram explains the research structure by author.

Figure 4.1: Lonsdale Street, Dandenong, has been transformed from a busy urban thoroughfare to a pedestrian boulevard ( Source: Leathlean, n.d.:online)

Figure 4.2: The benefits of a Good Public space as illustrated by PPS (Source: PPS, 2018:online)

Figure 4.3: Riverside Green supports Brisbane’s leisure and recreation needs in the city’s existing parks and public spaces and helps boost physical and mental wellbeing (Source: Burrows, 2022:online)

Figure 4.4: The lush and shaded rainforest deck and pavilion is an inviting, free public space designed for Brisbane’s subtropical climate (Source: Burrows, 2022:online)

Figure 4.5: Satellite image showing the plan view of Juhu Garden, western suburbs, Mumbai, admeasuring 0.4 hectares (Source: Google earth, 2022:online)

Figure 4.6: Image of Juhu garden, Mumbai, which can be classified as a Neighbourhood public space based on its size and usage (Source: Rajithagopinath, 2015:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

6

01

Figure 4.7: Satellite image showing the Priyadarshini park in South Mumbai, admeasuring 8 hectares (Source: Google earth, 2022:online)

Figure 4.8: Overview of Priyadarshini park, a City POS in South Mumbai. (Source: Chand, 2015:online)

Figure 5.1: A welcome city signage on the coast of Mumbai, India (Source: Kazemi, 2009:online)

Figure 5.2: Geographical map showing the location of Mumbai globally (Source: Kumar, 2020:online)

Figure 5.3: Map of Bombay in 1660 with the seven segregated islands linked in the 19th century was linked by The Hornby Vellard to form present-day Mumbai (Source: File:1660 Bombay map.jpg, 2018:online)

Figure 5.4: Population growth of Mumbai metropolitan in 2022 (Source: Mumbai population 2022, 2022:online)

Figure 5.5: The timeline of Mumbai highlighting major historic events (Source: By Author, 2022: Data from online)

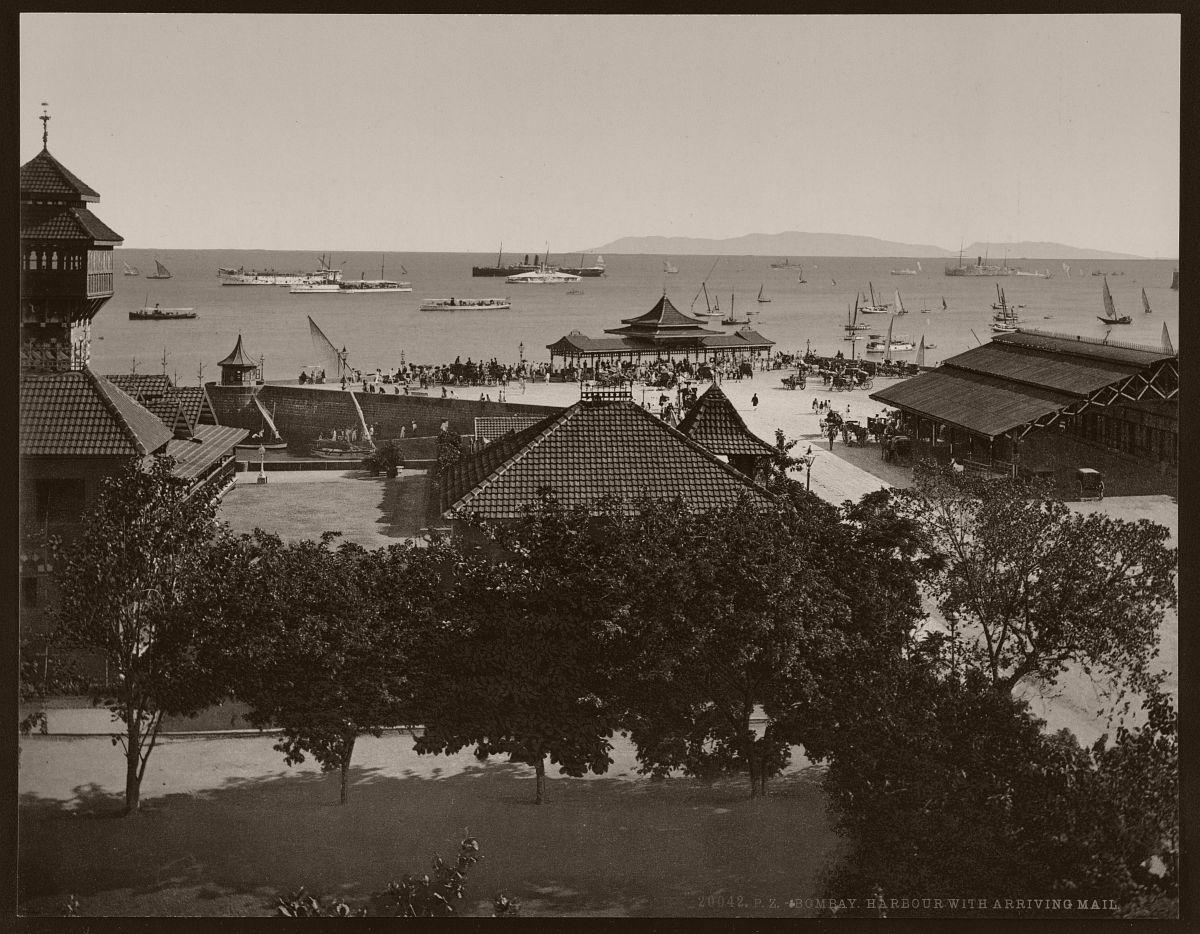

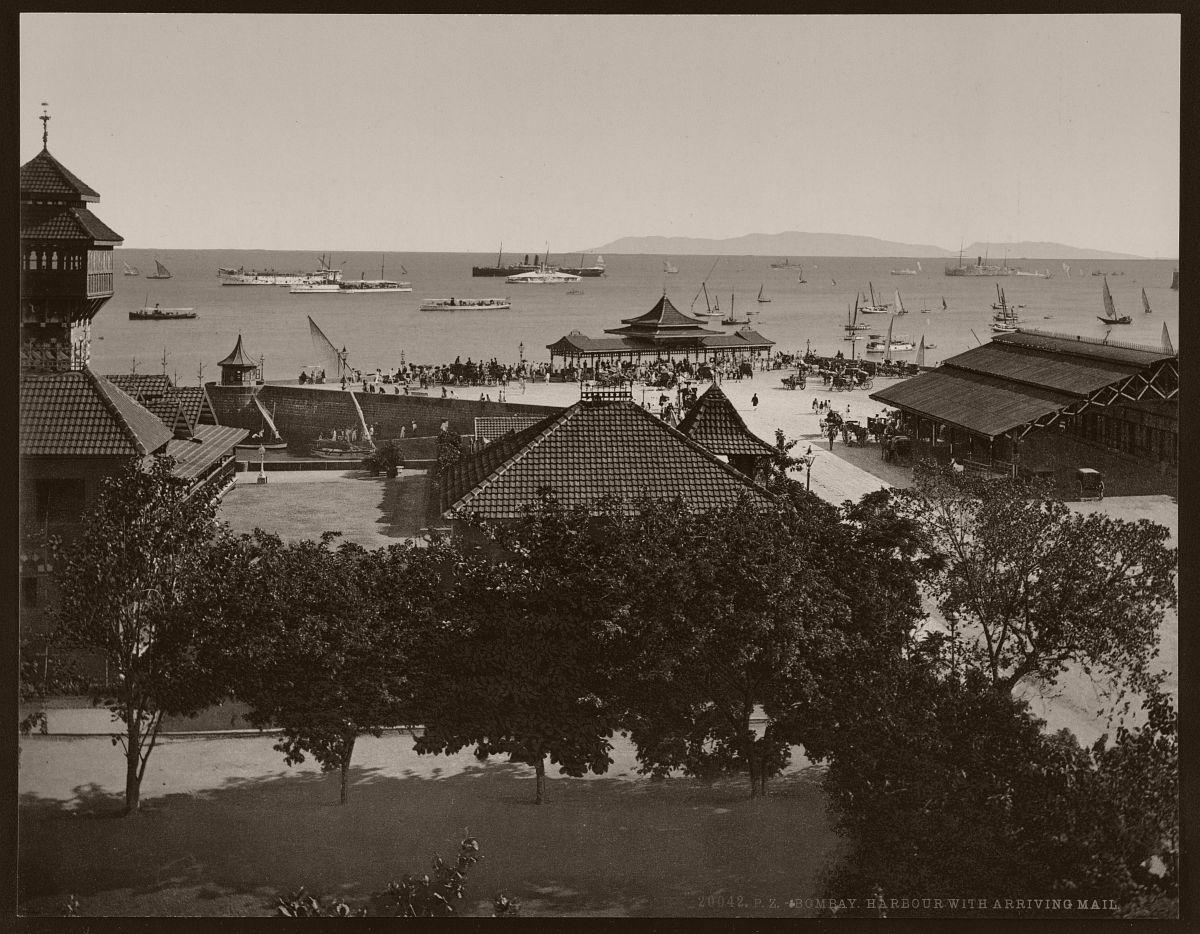

Figure 5.6: Bombay. Harbour with arriving mail. (1890s) (Source: Vintage: Historic B&W photos of Bombay, India (1890s),)2019:online)

Figure 5.7: The textile mills during the British rule were the early testimony of Bombay’s tryst as a trade capital (Source: Tale of the iconic textile mills of Bombay, 2022:online)

Figure 5.8: The geographical map of Mumbai with its suburban divisions (Source: Lesniewski, n.d.:online)

Figure 5.9: The Oval maidan in Colonial Bombay, 1875 (Source: Oval Maidan, n.d.:online)

Figure 5.10: The Oval maidan, Mumbai, is widely used as a playground today, 2010. (Source: Oval Maidan, n.d.:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

7

Figure 5.11: Satellite image of South Mumbai showing its colonial playgrounds, stadiums, promenade and nearest railway stations (Source: By author, image Google earth, 2022:online)

Figure 5.12: Satellite image of the maidans in Mumbai, as shown in the plan above (Source: 9gag.com, 2018:online)

Figure 5.13: Once there were sheds that used to be horse stables at Azad Maidan, Mumbai, under the British; over time, these were taken over by political parties and government offices (Source: The Story of Two Maidans, 2017:online)

Figure 5.14: The iconic Azan maidan hosts protests and public rallies even today, 2019 (Source: Kakade, 2022:online)

Figure 5.15: The social inequality in Mumbai as seen through its urban fabric. (Source: Miller, n.d.:online)

Figure 5.16: Map of Mumbai City showing its suburban regions, 2015 (Source: Maharashtra state gazetteers - greater Bombay district, n.d.: online)

Figure 5.17: Maps indicating the vegetation proportion decline in Mumbai over 30 years (Source: Maharashtra state gazetteers - greater Bombay district, 2020: online)

Figure 5.18: Land use change map indicating the sprawling of urban areas into open spaces over the period indicates a vast decline in its Mangrove zone (Source: Hrishikesh, 2020: online)

Figure 5.19: Tourism map of Mumbai showing the concentration of most public activities in the south of the city (Source: Mumbai map tourist attractions, 2016: online)

Figure 5.20: Mumbaikars relaxing on the promenade of Marine drive located in South Mumbai (Source: Norsworthy, 2010:online)

Table 6.1: Total provisions made for the gardens department from 2018 to 2020 (Source: ORF pg1:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

8

Figure 6.2: The poor maintenance and broken bench in a public park in Wadala suburb, Mumbai (Source: Mumbai Mirror, 2019: online)

Table 6.3: Table indicated the types of Open spaces in Mumbai (Source: Audit Public Open Spaces, 2007, pg.113:online)

Figure 6.3: Map indicating the open spaces in Mumbai (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Figure 6.5: The beachfront development in Tel Aviv, Israel, that attracts tourism (Source: Awl images, 2018:online)

Figure 6.6: New coastal street developed in Tel Aviv, Israel, for Recreational activities (Source: Barrel, 2019:online)

Table 6.7: Displays information about the proposed waterfront development in the DCR 2034 (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Figure 6.8: Plan demonstrating the development proposal for the Bandstand promenade in western Mumbai. It is a major source of recreational POS in the city (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Figure 6.9: Transformation of the Bandstand promenade in western Mumbai (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Figure 6.10: The scope for open space expansion summary, Mumbai (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Figure 7a.1: People enjoying a sunny afternoon in Richmond park, London (Source: Katie, 2017:online)

Figure 7a.2: Demographics comparison between London and Mumbai (Source: London vs Mumbai, 2021:online)

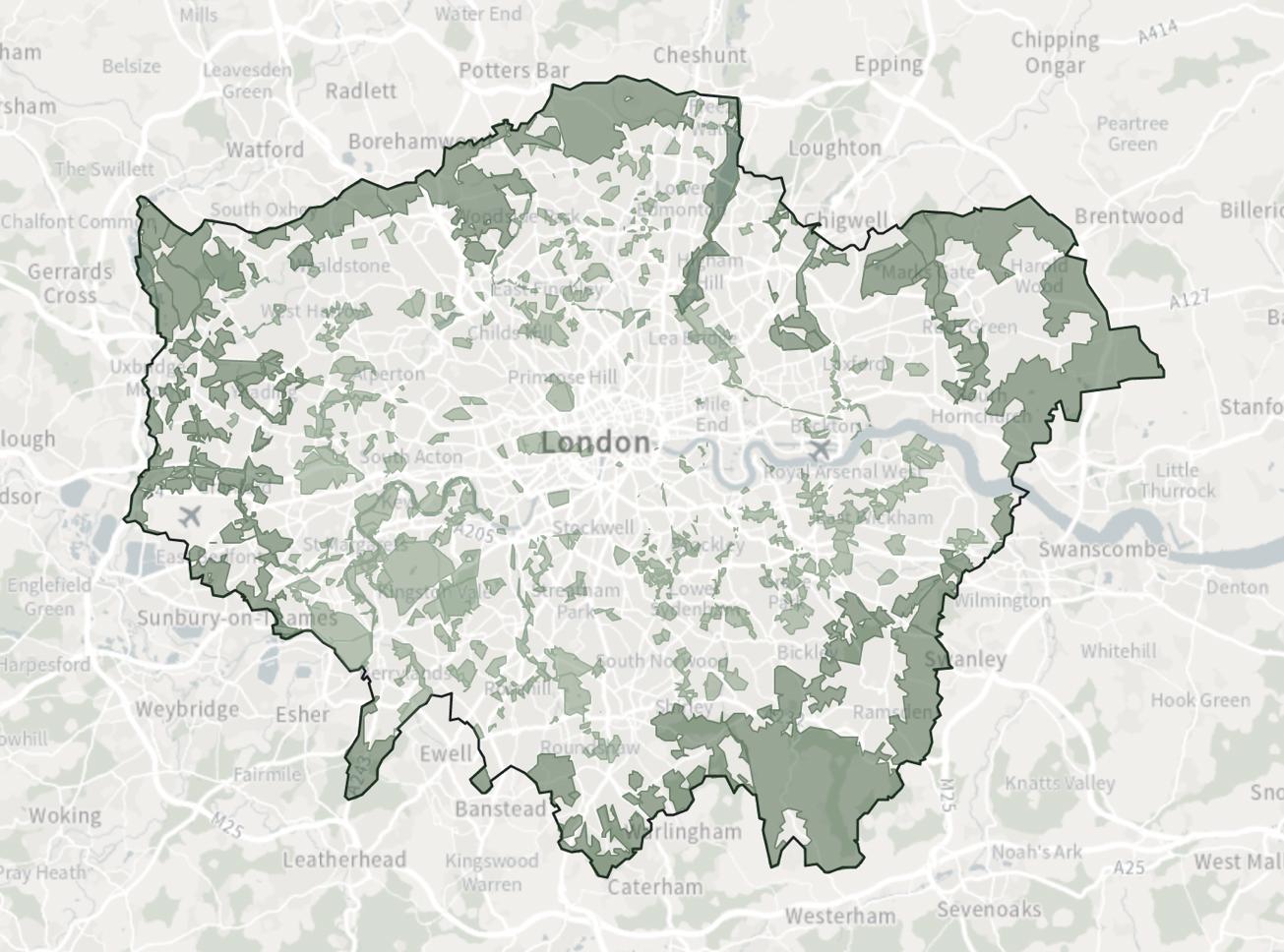

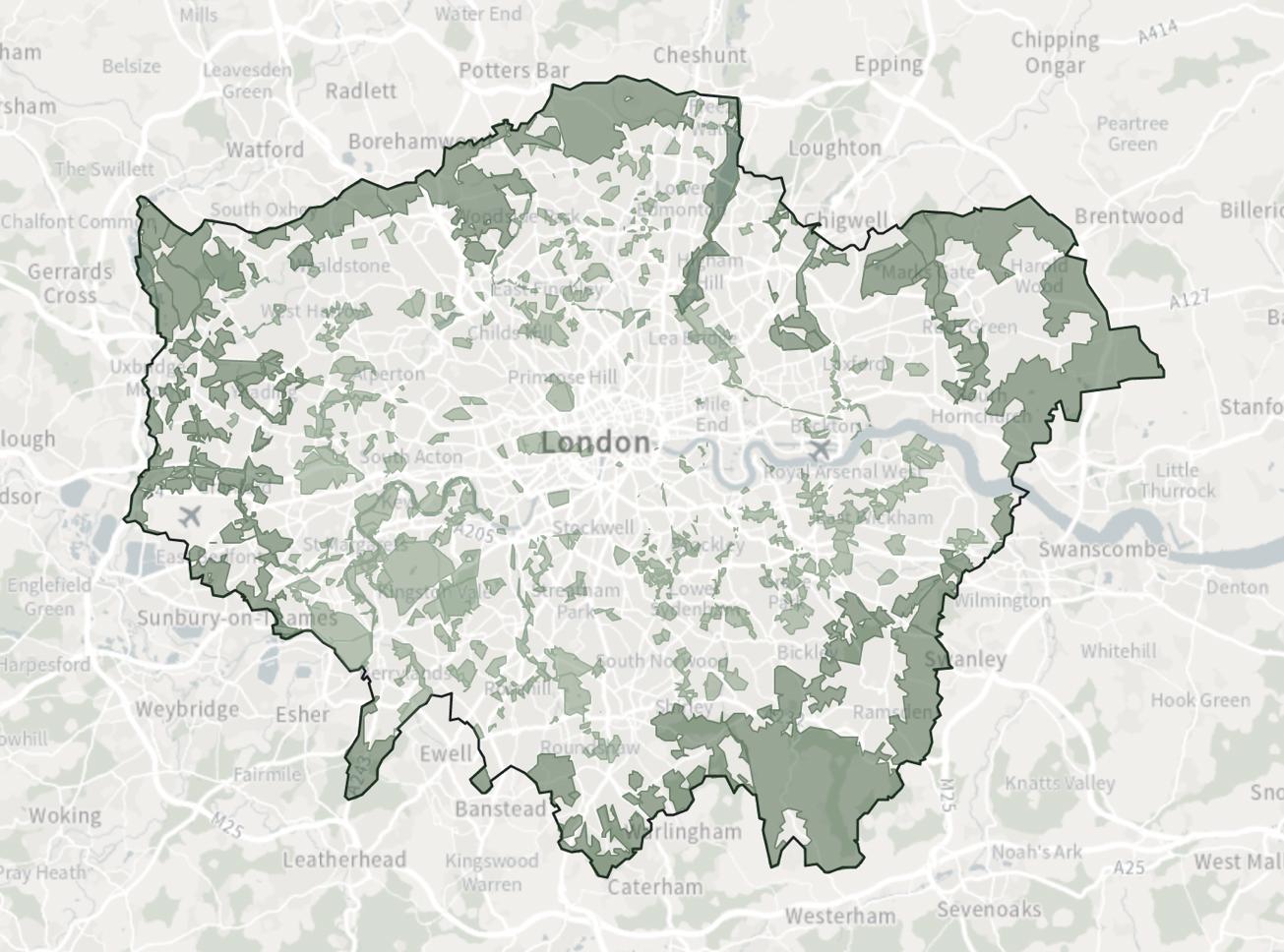

Figure 7a.3: The data map for London shows Designated Open Space (Source: Planning data map, 2022:online)

Table 7a.4: The London Plan Open Space Hierarchy (Source: Open Spaces Committee, 2015:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

9

Figure 7a.5: Demographics comparison diagram between London and Mumbai indicating London with a higher quality (Source: London vs Mumbai, 2021:online)

Figure 7a.6: Leisure comparison diagram between London and Mumbai indicating London with a higher component (Source: London vs Mumbai, 2021:online)

Figure 7a.7: An early morning overview of Hyde park, a widely used public open space in central London, UK, 2014 (Source: The National Police Air Service,2014:online)

Figure 7b.1: Factors that contribute to making a great place. ( Source: PPS, 2018: online)

Figure 7b.2: Location map for Juhu beach, Mumbai ( Source: Maps, of India: online)

Figure 7b.3: Juhu beach Land use and transport analysis map (Source: Vision Juhu, 2002:online)

Figure 7b.4: Analysing key functional issues on the beachfront of Juhu, Mumbai. (Source: By Author, 2022)

Figure 7b.5: Analysis of the pedestrian movement and utilities, Juhu beach, Mumbai (Source: By Author, 2022)

Figure 7b.6: Analysis of beach shore and activities, Juhu beach, Mumbai (Source: By Author, 2022)

Table 7b.7: Analysis of the Juhu beach based on design criteria is provided on a score of ten by the author (2022)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

10

A BBREVIATIONS AND T ERMINOLOGIES :

1) POS- Public Open Space

R.G- Recreational Ground

NPPF- The National Planning Policy Framework

ORF- Observer Research Foundation

BCIT -The Bombay City Improvement Trust

BMC- Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation

MCGM- Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

DCPR – Development control planning regulation

DP- Development proposal

URDPFI – Urban and Regional Plan Formulation and Implementation

PPS- Project for Public Spaces

Koli: An aboriginal fishing community of people with a rich history. There are currently about 23 existing Koli villages in Mumbai. (Refer to pg. 39)

Mumbaikar: The local inhabitants of Mumbai city are fondly referred to as ‘Mumbaikars’ (Refer to pg. 20,51,56,58,69 and 83)

Social Cohesion: Refers to the strength of relationships and the sense of solidarity among community members (Manca, 2014). (Refer to pg. 15 and 27)

Hornby Vellard Project: Then Governor William Hornby started the project in 1782 to combine the seven segregated islands of Bombay into one homogeneous land by building a causeway. The project linked all islands by 1838 to form present-day Mumbai (The islands come together: The Hornby Vellard reclamation project, n.d.). (Refer to pg. 37)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

11

02

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

11)

Indigenous rules: “Indigenous” describes any people native to a specific region. In other words, it refers to people who lived there before colonists or settlers arrived, defined new borders, and began to occupy the land (What does Indigenous mean? Definition, how to use it, and more, 2021) (Refer to pg. 39)

East India Company: The East India Company was an English company formed to exploit trade with East and Southeast Asia and India (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022) (Refer to pg. 39)

Salsette: The sizeable northern island of Bombay during the colonial era that was later connected to Mumbai by a causeway (What does SALSETTE mean? n.d.) (Refer to pg. 41)

Maidan: Originally a Persian word for town square was later adapted into the Urdu language, referring to a large open playground (Refer to pg. 42)

Development proposal: a development plan generally indicates how land use in the planning authority's area will be regulated. The Development Plan 2034 (DP) is a planning blueprint for all development (promotion and regulation) in the municipal area of Greater Mumbai. The DP document essentially comprises development control and promotion regulations (DCPR), proposed land use maps (DP Sheets) and a report on the development plan (DP Report) (UDRI, 2016). (Refer to pg. 66 and 93)

Ganesh Visarjan: Immersion day of Lord Ganapati's idol that takes place in a river, sea or water body as a part of the Hindu festival. (Refer to pg. 83)

Gaothan: The word 'Gaothan' is a Marathi word derived from the words 'Gaon' (which means 'village') and 'Than' (which means 'site'). It denotes the land included within the site of a village, town or city as determined by section 122 (Gaothan definition, n.d.). (Refer to pg. 84)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

12

RESEARCH OVERVIEW

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

13 03

‘Architecture is about Public spaces held by buildings . ’

Figure 3.1: Overview of the Marine Drive promenade in South Mumbai. (Source: Lloyd, 2017:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

14

- Architect Richard Rogers (in an Interview with Charlotte Higgins(Higgins, 2012))

3. INTRODUCTION :

A good public space enhances the quality of public life, which is integral to leading a democratic life. In a society where life is becoming steadily more privatised with private homes, cars, computers, offices and shopping centres, the social component of our lives is slowly vanishing. The cities need to be more inviting so that we can meet our fellow citizens and experience them directly (Matan, 2017). The presence of other people is always essential for your feeling of safety. Suitable quality public spaces do add value along with many other environmental benefits. It encourages social cohesion and contributes to social capital and community well-being when people of varying demographics come together to utilise it. Children who grow up in and around public places develop superior physical attributes and more vital social and cognitive skills in confrontation, emotional understanding, and crisis management (Gupta, 2022).

Mumbai, India's financial and entertainment capital, encompasses 604 sq. km and is home to 20.6 million people according to the census 2021 (Mumbai population 2022, 2022.). As per the UN's Sustainable Development Goals, creating "sustainable cities and communities" requires sufficient green open spaces. As the city is expanding, its open spaces are shrinking. There are merely 1.24 square metres of accessible open space per person in Mumbai, ahead only of Chennai at 0.81 square metres. Comparatively, Delhi has 21.52 square metres of open space per citizen, while Bangalore has 17.32 square metres. The international standard is 11 square metres per person (Pradeep Chaudhry, 2011). Figure 3.2 compares Mumbai to other global megacities with more open space per capita, including London, with 31.68 square metres; New York, with 26.4 square metres; and Tokyo, with 3.96 square metres (Udas, 2020).

15

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

Moreover, the current density of the city makes it impossible to build any large parks or centrally accessible public spaces. In a democratic country like India, it is impossible to create a garden the size of New York's central park without displacing more than 100,000 people (Das, 2013). This congestion thus demands an alternate strategy to create public space in cities like Mumbai, where more comprehensive solutions are challenging

Figure 3.2: Open Space comparison between major global cities (Source: Paul F, 2019:online)

3a. Aim:

To study and analyse the Public open space (POS) in Mumbai, India and further develop a framework to generate future strategies to increase the current per-person open space ratio.

3b. Objectives:

1. To analyse the current POS in Mumbai and understand the challenges of the city that lead to the present insufficiency.

2. To research guidelines laid for successful urban POS designs by planners globally compared to the existing ones in Mumbai.

3. To study the existing proposals for POS laid by the governing body in the development plan 2034 and reflect upon its shortcomings.

4. To explore the future potential in the city to increase the per-person open space ratio from 1.3 sq. m per person to the standards laid by the UN. (9 sq. m /person)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

16

3c. Research Questions:

1. Where does Mumbai stand compared to the global cities in its POS standards?

2. How can we uplift the existing design quality of POS and provide strategies to increase the open space ratio in the future?

Figure 3 3: Diagram showing the key considerations for planning open public spaces (Source: Public open space is accessible, protected and enhanced, n.d.,: online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

17

3d. Structure of Research:

The research chooses analytical methods based on the qualitative study of the current POS situation in Mumbai. Figure 3.3 defines the considerations for planning an open public space, and the same factors will be scrutinised in this research. The first chapter briefly defines POS and its impact to lay the foundation for the chosen research, its relevance, and the need. The following chapter provides a brief insight that focuses on the city of Mumbai, thus providing a background for the study. Further, the literature review provides a critical analysis of the available research material and helps derive the gap that will later be addressed in the empirical chapters. In the following chapters, empirical research methods, such as case studies and qualitative evaluation, are carried on to strengthen the research aim further. All these methods finally contribute to the suggestion of future strategies and opportunities the city withholds.

3e. Research Methodology:

To understand POS in the diverse urban setup, qualitative methods are adapted for this research to restrict the scope and derive the required framework This investigative research is mainly based on reviewing the available literature, urban survey maps, case studies, and empirical work. The following gives a brief description of each

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

18

3ei.

Literature Review:

It was essential to investigate two means of literature review for this research work. Firstly is to get the overall perspective of POS and understand its impact Secondly, to locally investigate the urban POS in Mumbai in its current setup For this purpose, the research begins with a brief review of the extensive works of some prominent Urban planners. Readings from the works of Jan Gehl, Jane Jacobs and Dr Luisa Bravo form the background spine of this research. Further, the study proceeds into the urban microanalysis of Mumbai and its current POS state. Urban planners P.K Das and Ar. Rahul Mehrotra is intensively involved with Mumbai to uplift its urban public space quality. This diverse review area has aided the formation of the research objectives and questions.

3eii.

Study of Maps:

Mapping is a systematic approach to thoroughly analyse a particular scope of research and evaluate its modifications over time. Recognising the factors that led to the present-day abysmal state is essential Data is available in the form of survey maps carried out by reliable sources that indicate the depletion of green spaces within the city.

3eiii.

Case Study:

The urban fabric of each POS is unique. This research will provide a comparative analysis of the POS in a global city like London. It is intended to establish a comparative analysis between parallel metropolitans and further adapt the good This section will lead to the micro-level qualitative analysis of today's widely used POS in Mumbai. In conclusion, this will set a precedent to understand what future measures should be taken.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

19

3eiv.

Empirical Study:

It is possible to recognise a space's unique characteristics through observation, one of the essential empirical methods. As a researcher, one can better understand spatial form and utilisation by observing segments of the relevant spaces. With this method, it will be possible to grasp the sense of the existing POS As a constant user of the POS in Mumbai, analysing its spatial quality came naturally to me. During my architectural journey, I spent hours observing how Mumbaikars used their public realm. The need for solid visual aesthetics, quality materials and the need for its expansion arose several times. This was one of the motivating factors that intrigued my interest in researching this topic

Figure 3 4: Diagram explains the research structure by author.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

20

WHAT IS PUBLIC OPEN SPACE?

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

21 04

22

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

-Jane Jacobs ( The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961:238)

Figure 4.1: Lonsdale Street, Dandenong, has been transformed from a busy urban thoroughfare to a pedestrian boulevard ( Source: Leathlean, n.d.: online)

‘

4.1 Definition

The city, throughout the history of humankind, has been the meeting place for people. Much of the culture of humankind has happened in the public space. Public space is a very important aspect of a good and well-functioning city’ (One, 2019:no pagination) - Jan Gehl

‘Public space in cities is a common good, meant to be open, inclusive and democratic, a fundamental human right for everybody’ (Stand up for public spaceLuisa Bravo, 2017)

The Charter of Public Space defines Public Spaces as ‘All places publicly owned or of public use, accessible and enjoyable by all for free and without a profit motive’ (Public space-Un Habitat, 2020)

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) defines open space as: 'All open space of public value, including not just land, but also areas of water (such as rivers, canals, lakes and reservoirs) which offer important opportunities for sport and recreation and can act as a visual amenity ' (National planning policy framework NPPF, 2012).

Although public spaces are commonly conceived of as ‘parks or other green spaces, this series defines public spaces as those spaces in which people take part in public life including parks, plazas, streetscapes, waterfronts, other permanent cultural assets such as museums or historical sites, as well as publicly accessible socioeconomic assets such as farmers’ markets, and pop-up cafes’ (Love and Kok, 2021)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

23

POS can be described in multiple ways, depending on the context, location, users, functionality and other factors. They can be further viewed through visual character, policy making, planning, and management Urban studies use many crucial formal terms and definitions to refer to ‘urban open and green spaces,’ including green space, urban greenery, open space, public space, public gardens and parks. From squares and boulevards to neighbourhood gardens and children's playgrounds, public space frames the city image. It takes many spatial forms, including parks, streets, sidewalks and footpaths that connect playgrounds of recreation and marketplaces. It also edges space between buildings or roadsides, often essential spaces for the urban poor.

Every space is defined by its people and their activities, often more powerfully than physical definitions alone. People may share a municipal park, a local street crowded with vendors, or a backyard among residences for socialising and recreation. We form our impressions of a city primarily based on the quality of its public spaces. Unless they are pleasant and preserved, or if they convey a sense of insecurity, we will not return. It should be the rule, not the exception, for these spaces to be well-planned (Pacheco, 2017)

This research paper will primarily focus on public open spaces that are present, free, accessible, and used by the public for recreational purposes. To further analyse the topic, let us first understand why its existence is significant and how it benefits society. The following chapter will discuss and investigate key points which will help understand its impact.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

24

4.2 Importance of Public Open Space:

“A good city is like a good party people stay longer than necessary because they are enjoying themselves”.

Jan Gehl (Cities for people,2010)

A city's quality of life is heavily influenced by its open spaces. The origins of many of these spaces are owed to people's regular use, while others were developed consciously. Today, public space deals with cultural richness, identity and diversity, inequalities, contradictions and conflicts (Stand up for public space - Luisa Bravo, 2017). As part of the urban fabric, open spaces provide spaces for leisure, interaction, and, often, everyday transactions. It has long been shown to enhance community well-being producing positive health, environmental, economic, and social outcomes for residents who can access them (Braubach et al., 2017).

As jobs get more hectic and demand long desk hours, green spaces promote relief to better mental well-being. Physical activity in a natural environment helps in reducing depression and physiological stress. As public space allows us to interact and bond, diminishing leads to loneliness and other adverse psychological effects (Kapoor, 2022).

Figure 4.2 illustrates a diagram of the benefits of a good public place. According to the UN-Habitat 2018 held in Nairobi, in addition to enhancing the quality of life, a network of open public spaces improves the mobility and efficiency of the city as well. Streets and open public spaces designed and maintained well can help lower crime rates and violence. They also create opportunities for formal and informal economic activities and provide services and opportunities for a diverse user population, especially those marginalised. Providing opportunities for youth, empowering women, and fulfilling human rights requires public space as a common good (United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi, 2018). Creating green

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

25

open spaces mitigates the effects of climate change, provides wildlife habitats and improves air and water quality.

Figure 4.2: The benefits of a Good Public space as illustrated by PPS ( Source: PPS, n.d: online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

26

According to the Project of Public Spaces, 2009, some of the prominent advantages of POS are listed below (10 benefits of creating good public spaces, 2009):

• Improving Public health: Human health and well-being, i.e. positive impacts of POS and park use on human health (both mental and physical) and wellbeing through direct or indirect effects such as recreation and leisure activities. Figure 4.3 shows the new Riverside Green development in Brisbane with jogging and cycling tracks which help boost physical and mental well-being.

• Social cohesion / Identity: Humans are said to be social animals. The importance of public spaces in fostering social links, relationships, and cohesiveness has always been essential.

• Boosting Tourism: Longer-term trips for leisure outside the home or working surroundings are a common practice today. Tourism is essential owing to its benefits to the local economy and its potential to boost the health and wellbeing of tourists.

• Fostering Biodiversity: The significance of green open spaces in sustaining and fostering biodiversity, particularly species diversity, can be seen in figure 4.4, where the new riverside development in Brisbane fosters biodiversity Human well-being is intimately related to biodiversity through nature experience. At the same time, it offers a vital foundation for ecosystem functioning and, as a result, a variety of ecosystem services (Cecil C. Konijnendijk Matilda Annerstedt Anders Busse NielsenSreetheran Maruthaveeran, 2012, pg3)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

27

• Ecological Impact: It positively impacts air quality by reducing air pollutants and carbon content. It also contributes to water management by creating percolation surfaces that can absorb the runoff water against the hardscape, which leads to accumulation and floods in most cases.

• Economic growth: Neighbourhoods with POS facilities such as recreation spaces, sports grounds, and parks increase the demand for the place and, in return, lead to high valuation. The POS also provides a grassroots opportunity to boost the local economy.

• Supporting local business: POS provides opportunities for local businesses to thrive. These open spaces can be used as flexible, multi-use plazas to hold local markets, fairs, and events. This practice is often observed in the Medieval squares in European countries.

• Providing cultural opportunities: Culture gives every city its unique character. With the new multicultural and diverse habitation in the 21st century, the function of a POS can be elaborated to suit the needs. Various cultural activities, such as street plays, theatre, and live performances, can help entertain and educate the people.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

28

29

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

Figure 4.3: Riverside Green supports Brisbane’s leisure and recreation needs in the city’s existing parks and public spaces and helps boost physical and mental well-being (Source: Burrows, 2022:online)

Figure 4.4: The lush and shaded rainforest deck and pavilion is an inviting, free public space designed for Brisbane’s subtropical climate (Source: Burrows, 2022:online)

4.3 Types of Public Space:

According to the UN-Habitat, City-wide public space strategies: Guide for local governments, draft report 2018, Public open spaces can be categorised into four broad levels based on their sizes and catchment (Rudd, 2018).

1. Local public open spaces – These are small neighbourhood parks that range to a distance of 400 meters. The purpose is to meet the recreational requirement of the immediate neighbourhood (Rudd, 2018)

2. Neighbourhood Public open spaces – These are bigger spaces that fulfil the community's social and recreational needs. Within 400 metres of homes, they are conveniently accessible and range in size from 0.04 to 0.4 hectares (Rudd, 2018) Figure 4.6 shows an image of the Juhu Garden in Mumbai, which fulfils the recreational requirement of the Santacruz suburb.

3. District/city or city Public open spaces - They have sizable recreation areas and some natural regions. The areas, which range in size from 0.4 to 10 hectares, are intended to benefit those who live within 800 metres or a 10-minute walk (Rudd, 2018). Figure 4.8 gives an overall view of the Priyadarshini park, Mumbai, which measures about 8 hectares and serves the entire city.

4. Regional /Larger city parks- These are virtual spaces for organised play, socialising, unwinding, and enjoying the outdoors. They will likely draw tourists outside any local government area and serve one or even more geographical or socioeconomic regions. Their sizes vary from 10 to 50 hectares (Rudd, 2018)

5. National / Metropolitan Public open spaces – These are substantial regions, between 50 and 200 hectares. They accommodate several purposes and offer recreational, sports, and basic facilities (Rudd, 2018).

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

30

Figure 4.5: Satellite image showing the plan view of Juhu Garden, western suburbs, Mumbai, admeasuring 0.4 hectares (Source: Google earth, 2022:online)

Figure 4.6: Image of Juhu garden, Mumbai, which can be classified as a Neighbourhood public space based on its size and usage (Source: Rajithagopinath, 2015:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

31

Figure 4.7: Satellite image showing the Priyadarshini park in South Mumbai, admeasuring 8 hectares (Source: Google earth, 2022:online)

Figure 4.8: Overview of Priyadarshini park, a City POS in South Mumbai. (Source: Chand, 2015:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

32

We see the presence of all the types mentioned above POS in our cities daily. If we carefully examine them based on their location, size and function, it will be easier to categorise each mentally When dealing with POS, the scale may vary from a local neighbourhood part to the vast recreational promenades This variation makes it an exciting research forum to analyse and further discuss. This introductory chapter thus helps us to understand the idea of Public Open Space that the research will further look into. This research focuses on the accessible open space for public recreation and leisure. Understanding the POS's scale, types, and various functions is essential. It supports the research aim and objectives and forms a narrative to signify the importance of its presence and the need to bring it to attention in an urban fabric.

Regional context plays a crucial role in how cities develop and respond to its surrounding. Each city is unique based on the interventions created and the response generated over time. This determines its strengths, weaknesses, failures and present-day reality. The city of Mumbai is no different. It has evolved since its existence, which has had a significant impact on its current POS. To further streamline this research, the next chapter will focus on exploring and scrutinising the context it is placed in, the city of ‘Mumbai’.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

33

RESEARCH CONTEXT

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

34 05

Figure 5.1: A welcome city signage on the coast of Mumbai, India (Source: Kazemi, 2009:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

35

‘More dreams are realised and extinguished in Bombay than any other place in India.’

-Gregory David Roberts (Gregory David Roberts Quotes, n.d.)

5.1 Introduction to Mumbai

India is the most populous democracy and the second-most populous nation in the world. Figure 5.2 shows the location of Mumbai, the state capital of Maharashtra, which lies on the western coast of India. With a population of over 21 million in 2022, it is the most densely populated city in the country and amongst the most densely populated urban area in the world (Mumbai Population 2022, 2022). It has a deep harbour with the main port on the Arabian sea; in addition to trade activities, it is also India's financial and commercial capital (Raghavan, 2022a) Figure 5.3 shows a group of seven segregated islands that have undergone severe reclamation to form present-day Mumbai (Gupta, 2005).

Figure 5 2: Geographical map showing the location of Mumbai globally (Source: Kumar, 2020:online)

36

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

Figure 5.3: Map of Bombay in 1660 with the seven segregated islands linked in the 19th century was linked by The Hornby Vellard to form present-day Mumbai (Source: File:1660 Bombay map.jpg, 2018:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

37

It covers an area of about 619 square km within an urban limit (Dermographia World Urban Areas, 2022). The population of Mumbai is growing by approximately 5 per cent yearly (Refer to Fig 5.4). Mumbai's business opportunities attract migrants from all over India. The centre of India’s cotton textile industry subsequently developed into a highly diversified manufacturing sector (Raghavan, 2022a). However, due to the high density, it has experienced some problems that plague many considerably developing industrial towns, including pollution, lack of affordable housing, open space encroachment and overpopulation. The physical restrictions of the city's island position worsen the current situation as the scope of expansion drastically reduces. (Raghavan, 2022a).

Figure 5.4: Population growth of Mumbai metropolitan in 2022 (Source: Mumbai population 2022, 2022:online)

To better evaluate the current situation in the city, let us look at pre-independent Mumbai in the 18th century under the colonial reign and the way many of its presentday open spaces came into existence.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

38

5.2 History – BOMBAY TO MUMBAI :

The history of Mumbai dates back to the 7th century when the Koli people first inhabited the area. The islands were under the control of successive indigenous rulers for centuries before the Portuguese Empire and subsequently to the East India Company in 1661 due to Catherine Braganza's dowry when she married Charles II of England (Wynn).e, 2004). The British then took control of the city in the 18th century and transformed it into a major trade and industrial hub. Figure 5.7 demonstrates that the city was known for its cotton mills and thriving port during the British reign In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Mumbai experienced rapid growth and expansion. Figure 5.5 demonstrates the city's timeline until it became part of independent India in 1947 (Gupta, 1996).

Figure 5.5: The timeline of Mumbai highlighting major historic events (Source: By Author, 2022: Data from online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

39

Figure 5.6: Bombay. Harbour with arriving mail., 1890s (Source: Vintage: Historic B&W photos of Bombay, India (1890s),)2019:online)

Figure 5.7: The textile mills during the British rule were the early testimony of Bombay’s tryst as a trade capital (Source: Tale of the iconic textile mills of Bombay, 2022:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

40

5.3 Public spaces in Colonial Mumbai:

The old city, which stretched from Mahim and Sion on Bombay Island's northern shore to Colaba Point on its southern point, encompassed around 26 square miles (67 square km). Figure 5.8 demonstrates the many suburban division of the city that came into existence post-independence for administrative purposes. Mumbai grew to include the sizable island of Salsette in 1950, which connected to Bombay Island via a causeway

Figure 5.8: The geographical map of Mumbai with its suburban divisions (Source: Lesniewski, n.d.:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

41

In pre-independent India, from 1888 to 1947, the Bombay Presidency maintained and protected all open spaces in the city. The Bombay City Improvement Trust (BCIT) was formed in response to the 1898 plague epidemic (Pathak, 2021) It prepared a development plan with 300 open spaces to better public health and living conditions. The impact was also seen in crowded neighbourhoods, where streets were expanded, encroachments were cleared, and the sea was reclaimed for expansion (Pathak, 2021).

The textile export led to the immense development of the coast. At the same time, the eastern harbour was mainly used for trade and remained inaccessible to people. The western coast subsequently developed into promenades and accessible beaches, resulting in public open spaces. A few notable public spaces like the maidans (playground) of South Mumbai, as seen in figure 5.11 and spatial markers like the Martyr's Memorial at Flora Fountain offered respite from the busy city. Figure 5.9 and 5.10 demonstrates the Oval Maidan, admeasuring 22 acres, which is located near the Gateway of India, used for recreational activities such as cricket and soccer even today. Another maidan worth mentioning is the Azad maidan measuring about 40 acres, an active protest ground during the Indian independence era, as seen in figure 5.13.

Figure 5.9: The Oval maidan in Colonial Bombay, 1875 (Source: Oval Maidan, n.d.:online)

Figure 5.10: The Oval maidan, Mumbai, is widely used as a playground today, 2010. (Source: Oval Maidan, n.d.:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

42

Location Plan, South Mumbai

Figure 5.12: Satellite image of the maidans in Mumbai, as shown in the plan above (Source: 9gag.com, 2018:online)

43

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

Figure 5.11: Satellite image of South Mumbai showing its colonial playgrounds, stadiums, promenade and nearest railway stations (Source: By author, image Google earth, 2022:online)

Figure 5.13: Once there were sheds that used to be horse stables at Azad Maidan, Mumbai, under the British; over time, these were taken over by political parties and government offices (Source: The Story of Two Maidans, 2017:online)

Figure 5.14: The iconic Azan maidan hosts protests and public rallies even today, 2019 (Source: Kakade, 2022:online)

44

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

Conclusion:

A strong design influence in Mumbai’s public open spaces is derived from the colonial era; the spaces are still preserved and enjoyed by locals. Colonial proportions, architecture and ornamentation, are strongly visible in the city's southern tip This is why most major tourist attractions are concentrated here We see a vast difference in this zone when compared to the central and northern suburbs that were organically developed later. Compared to the present proportion and scale, the public open spaces in the past were larger and integrated in planning. They formed a central node for the agglomeration of people during festive celebrations, sports and historical events such as protests and rallies during the 1947 Independence of the country.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

45

5.3 Present-day Mumbai

Crawling with people from different parts of the world, it is a religious, social and economic icon. Like any other global city, Mumbai is an amalgamation of diverse neighbourhoods, each with distinct identities, opportunities, strengths and weaknesses. It possesses the dichotomous dualism of being the financial capital of the country as well as the slum capital of the world. About 12 % of Mumbai’s geographical area is covered by its nine million slum dwellers, which constitute 55% of its total population (Borgen Project, 2017). The population density of Dharavi, the largest slum in Asia, is 2,77,136/km2 compared to 38,242/km2 in New York City (Singh, 2022) As seen in figure 5.15, with luxury skyscrapers and blue tarp-covered shanties existing side-by-side, the city has some of the most unequal neighbourhoods in the world.

46

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

Figure 5.15: The social inequality in Mumbai as seen through its urban fabric. (Source: Miller, n.d. :online)

Figure 5.16: Map of Mumbai City demarcating its suburban regions, 2015 (Source: Maharashtra state gazetteers - greater Bombay district, n.d.: online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

47

Depletion of Open Spaces:

Of Mumbai’s total area of 63,035 hectares (ha), the green cover was 29,260 ha in 1988, which fell to 20,481 ha in 1998, 17,331 ha in 2008, and 16,814 ha in 2018, which means an overall decline of 42.5% over 30 years (Chatterjee, 2020). Figure 5.17 shows that the green cover lost is 12,446ha, more than the size of the largest national park in Mumbai, the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (10,300ha) location in figure 5.16 (Chatterjee, 2020).

Figure 5.17: Maps indicating the vegetation proportion decline in Mumbai over 30 years (Source: Maharashtra state gazetteers - greater Bombay district, 2020: online)

As seen in figure 5.17, the ratio of green spaces to total area fell from 46.7% in 1988 to 26.67% in 2018, with the most significant changes observed during 1988-1998, when around 14% of green spaces had transformed due to development activities (Chatterjee, 2020 ). This study conducted as published in the journal Springer Nature states that this depletion has adversely affected the microclimate of Mumbai (Chatterjee, 2020). It has further impacted the air quality and the ecological balance. The above maps show major green depletion in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park towards the north and the Goregaon creek area towards the central west. The

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

48

environmentalist in the city fears that if the same trend is seen in the next ten years, it will gravely affect biodiversity and human well-being.

Figure 5.18: Land use change map indicating the sprawling of urban areas into open spaces over the period indicates a vast decline in its Mangrove zone (Source: Hrishikesh, 2020: online)

Figure 5.18 shows that the Urban areas are sprawling over the open green, resulting in the drastic depletion of the natural greens. Mumbai has 15.37 square kilometres of accessible open space, providing free and fair entry to all citizens. Overall, the depletion of open spaces in Mumbai results from several factors, including urbanisation, population growth, lack of planning and regulation, and the high land cost. This has negatively impacted the city's quality of life, as residents have less access to open green spaces. As seen in figure 5.19, most tourist hubs like the Marine Drive promenade (Figure 5.20), the Chowpatty, Kamla Nehru park, Priyadarshini gardens, and Gateway of India are concentrated towards the south. At the same time, the western coast provides some relief to the suburbs with the restoration of the Bandstand and Carters promenade, leaving the national park alone to balance the North of the city

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

49

Figure 5.19: Tourism map of Mumbai showing the concentration of most public activities in the south of the city (Source: Mumbai map tourist attractions, 2016: online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

50

Figure 5.20: Mumbaikars are relaxing on the widely used recreational Marine drive promenade in South Mumbai. One can see a high density of people on the weekends due to the lack of sufficient POS in the city. (Source: Norsworthy, 2010:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

51

Conclusion:

Unfortunately, the decline in public open space in Mumbai city has been observed in recent years. This trend is concerning as these spaces provide numerous benefits to the community, including green infrastructure, recreation opportunities, and economic benefits. It is important for city leaders and residents to prioritise the protection and maintenance of public open spaces to ensure they continue serving as valuable assets for the city. The POS provide much-needed green space in a densely populated city and serve as an important gathering place for the community. Despite its many challenges, including overcrowding and pollution, it remains a vital and vibrant city, attracting visitors and residents from all over India and the world. It is a true testament to the resilience and spirit of its people. Just like the city provides its people with all the overwhelming opportunities, it is time for us to pay back by providing the city with much-needed breathing space.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

52

LITERATURE REVIEW

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

53 06

6.1 Formulating open space policies, Mumbai

Introduction:

The city's government is administered by the fully autonomous Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM). Several standing committees within its legislative body are elected every four years through public voting (Raghavan, 2022b) The Observer Research Foundation, in April 2020, analysed the state of the many government bodies in India that drive the open space regulation in Mumbai and further discovered the shortcoming and inadequacies that have led to the current state of POS. It further describes how these policies can be amended and improved to increase the current POS index in the city. This chapter will be a review to understand the reasoning and to find unaddressed gaps that will be explored.

Information:

Every city is driven by its development plans and regulations that dictate these plans. According to the ORF paper, the city of Mumbai has lost significant open spaces due to the discrepancy between the BMC and other bodies, in addition to the unachievable goals, ancient policies and poor division of power. According to the URDPFI guidelines, Open spaces are listed under three categories: recreational space, organised green space, and other common open spaces. All local bodies within the city follow these URDPFI land planning guidelines (Udas, 2020). In the current 2034 development draft, the BMC has increased the open space from 26 per cent to 46 per cent in 2016. To achieve this leap, the definition of open space was revised, including ecologically sensitive areas like mangroves, coral reefs and biosphere reverse along with water bodies such as beaches, coastlines, creeks and rivers. However, most of these open spaces are inaccessible to the people and thus should not qualify as POS (Udas, 2020).

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

54

In a country like India, political influence and power often sway development in the direction of personal agendas and achievements. In this battle, the city and its people always face greater losses For instance, with a 16-kilometre coastline, most beaches in the city remain inaccessible. This results from its many interfering bodies, each trying to supersede the other. The beaches fall under a central government agency, which often does not work in coordination with the local civic bodies (Udas, 2020).

Further, an interesting aspect of this research focuses on the current maintenance policies of the POS. Unfortunately, the BMC Act, which narrates the rules for the city, considers the maintenance of POS as a discretionary duty and not a mandatory one. This has resulted in a casual attitude by authorities in maintaining the same. The present state of many such POS is poorly maintained, with broken public utilities such as benches, play equipment and toilets (Udas, 2020). Private entities own an additional 128.41 square kilometres of available open space, thus restricting free access for people. This poor maintenance, in turn, affects the budget allocations, as seen in table 6.1, for POS upkeep. In 2017-18, the BMC allocated only 1.3 per cent of its total budget towards maintaining open spaces, which was subsequently cut down to 0.7

Table 6.1: Total provisions made for the gardens department from 2018 to 2020 (Source: ORF pg11:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

55

The ORF research paper further analyses the 1967-87 DP, 1991-2011 DP and the recently proposed 2014-34 DP. It systematically lays down the impact of amendments bought about by each. From the given data, it is observed that from 1991, the city expanded towards its northern suburbs rapidly in search of affordable housing. This leads to a higher population density in these pockets, thus leading to ignorance of the POS balance. Most large POS is currently observed in the South of Mumbai as the British colonies administered from this pocket. The imbalance between the Organic Northern suburbs and Planned Southern Island city is seen today.

Key Findings:

• DCR was created in 1991 to regulate the development of the different land uses in the development plan. Mumbai's population has grown by more than 75% since then, but the 2034 DP does not show a corresponding increase in public amenities and POS (Audit: Public Open Spaces in Mumbai, 2007).

• The 2014-34 DP for Mumbai bumped up the percentage of open space in the city from 26 per cent in 2012 to 46 per cent in 2016 by changing the definition of open space (Udas, 2020)

• Private developers and the value of real estate effectively regulate most government policies. Post-1991, the BMC introduced a special clause that gave the municipal commissioner rights to allow acquiring open plots through certain agreements. Several of the plots were later found to be associated with political organisations. (Refer to appendices)

• Ownership and maintenance of such parcel of public open space shall be under one deemed body. At present, it is distributed amongst the central, state and local governments, which further leads to loss of ownership and, in order, makes its protection, maintenance, and development difficult due to several hidden political agendas.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

56

Figure 6.2: The poor maintenance and broken bench in a public park in Wadala suburb, Mumbai (Source: Mumbai Mirror, 2019: online)

Table 6.3: the types of Open spaces in Mumbai ( Audit Public Open Spaces, 2007, pg.113:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

57

Conclusion:

The strength of the evidence of this paper was accessed based on understanding the past and existing policies that regulate the POS in Mumbai. Considering the present situation, it may not be possible to match the open space percentage of global cities like New York, Sydney and London. Still, it can undoubtedly be improved by making necessary provisions in the development plan. The research well summarises the impact of the changing policies on the POS but fails to present case studies of a specific case scenario. Elaboration on the impact of these policies must be conducted by examining the current state of the POS in the city. It provides a detailed understanding of how the policies led to the failure of the expansion of the public open spaces in the city of Mumbai; rather does not dwell on physical solutions that the city holds. The research would have been more relatable if the DP regulations in Mumbai were put in perspective along with some successful global examples. It is important to understand why one failed; rather essential, knowing how one could have succeeded. The narration is backed up by intense data research from authenticated sources, though it lacks relevant case studies.

After understanding the policies that have regulated the city POS, let us know its actual impact as seen today. In addition to the arbitrary decisions in urban development, several other physical factors lead to declined POS. In the further review, the research examines the present-day data through a survey carried out by an urban planner in the city. It offers elaborate solutions without bringing about substantial changes in the 2034 D.P.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

58

6.2 Open Mumbai: Re-Envisioning Open Spaces

Introduction: Our cities have deteriorated into an undesirable state due to declining quality of life, growth of uncontrolled informal settlements, deprivation of open spaces, exploitation of the environment and abuse of ecological assets, including the coastline. Other factors, such as lack of affordable housing, arbitrary decision-making, segregated privatised development and the growing real estate thrust, drive the growth of available open spaces. With the economic development, foreign investments and global operation shift, the city are governed by the real estate agenda. This agenda needs an immediate change of drifting focus towards the people, their community and their social needs.

Several Urban planners in Mumbai have been rigorously working on studying the city, its urban limits, built fabric and open spaces. One of many such pioneers is Activist and Architect P.K. Das. In this review, Das, through years of surveys and research, provides a strategy for the increase in current POS. In Open Mumbai, he carefully analyses the geographical structure of the city. It proposes to conserve and convert the city's natural assets in integration with the urban infrastructure and make them accessible to people.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

59

Figure 6.4: Map indicating the open spaces in Mumbai (Source: Das, 2013:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

60

Information:

While there is an expansion in towns, the shrinking of open spaces is more evidently visible. Unplanned urbanisation has only 2152 reserved recreational open spaces, including games, playgrounds, recreational grounds, beaches and promenades within Mumbai; out of this, 600 are encroached upon, and data for the remaining others is not available with the municipal corporation. These open spaces comprise 3.3% of Mumbai's total area (Das, 2013). The urge to create non-exclusive and nonbarricaded spaces has become the utmost priority the need to go beyond recreational gardens and parks as open social spaces are desired. The vast natural resources available within Mumbai provide an opportunity to include existing coastlines, harbours, forest land, mangroves and beaches as accessible POS. The main objective of this research is thus based on the expansion and connection of various available natural parcels to conserve, protect and further provide a comprehensive plan for its public use. In order to do so, it also recommends making necessary amendments to the DP and DCR.

Open Mumbai has calculated that the city has just 1.1 square metres of open space gardens, parks, recreational grounds and playgrounds per person. This city has 2.5 square kilometres of gardens and parks, 4 square kilometres of playgrounds and 7.7 square kilometres of recreational grounds (Das, 2013). This adds up to just over 14 square metres of open spaces for 12.4 million people, 1.1 square metres per person; this corresponds to the statistics that Mumbai has a poor 0.03 acre of open space per 1000 people (Rajadhyaksha, 2012)

Urban development plans have always targeted coastal regions because of their historical and socio-political significance. As seen earlier, Mumbai is a city along the West coast of India, which gives it the physical opportunity of a vast coastline. Currently, with 149 km of coastline and an interconnected island, many of these still need to be made available. In addition to the seafronts, the research proposes to

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

61

develop and integrate beaches, rivers, creeks, mangroves, and forest lands into POS. Table 6.7 displays the potential to develop its 16-kilometre-long beachline and open out the spectacular views of the Arabian Sea. Tel Aviv, Israel, has successfully adopted a similar beach restoration programme, as seen in figure 6.6 Unfortunately, at present, constructions are being permitted close to the coast, leading to ecological damage and water contamination. Besides the coast, it has about 70 sq. km of mangroves and creeks. These eco buffers need awareness to conserve them and can be developed as boardwalks and nature trails to make them public recreation spaces. These proposals are backed up by data, physical surveys, and information from local civic bodies, making them even more practical. The research provides case studies of a few earlier works by Das in the city. These include the Western promenade of Carter road and Bandstand along with Juhu beach.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

62

Figure 6.5: The beachfront development in Tel Aviv, Israel, that attracts tourism (Source: Awl images, 2018:online)

Figure 6.6: New coastal street developed in Tel Aviv, Israel, for Recreational activities (Source: Barrel, 2019:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

63

Table 6.7: Displays information about the proposed waterfront development in the DCR 2034 (Source: Das, 2013:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

64

Figure 6.8: Plan demonstrating the development proposal for the Bandstand promenade in western Mumbai. It is a major source of recreational POS in the city, especially for the western suburbs. (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Figure 6.9: Transformation of the Bandstand promenade in western Mumbai, new pavement work, and landscape elements were added. (Source: Das, 2013:online)

Left: Image before it was accessible to public use.

Right: Image after redevelopment, the promenade has become a busy recreational POS for people

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

65

Key findings:

• The research suggests that all re-developments should recognise and respect existing realities as part of the planning and urban development process.

• It strongly recommends that open spaces demarcated in the development plan shall not be built upon under any circumstances or exceptions.

• The plans and proposals should be rooted in conservation, restoration, recycling, re-planning and re-structuring existing realities and their spatial transformation.

• Mumbai needs to identify, preserve and explore its natural assets to increase its POS and experience them as a part of the freely accessible public realm.

• The research encourages integrating natural assets with urban areas providing recreational activities such as cycling, walking and jogging.

• Natural lands, including the National Park, the mangrove, and the forest, shall be declared protected zone by the government.

• A network of open spaces, transparent and easily accessible, is proposed to be created for all citizens equally.

• It further recommends reserving spaces around public markets and buildings as POS with a view to its future expansion and needs.

• Lastly, public participation and representation are vital in creating awareness and decision-making policies. Several citizen groups can co-ordinate within its neighbourhood precinct for easy monitoring and administration

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

66

Figure 6.10: The scope for open space expansion summary, Mumbai. The summary proposes to achieve 41.7 % open spaces if the research strategies are implemented (Source: Das, 2013:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

67

Conclusion:

Mumbai's open spaces are being mapped as part of a more significant movement to reclaim public spaces. To comprehensively document the city's open spaces, it is necessary to conduct surveys and gather data, including the wide range of environmental assets described in this research Mumbai can thus take one step closer to being not only a global metropolitan but also one of the most liveable This research is meticulously worked on smaller wards, making it easier to understand. It does not provide a radical approach but focuses on smaller, more practical solutions that can easily be implemented. Sharing case studies of exemplary precedents within the city provide hope for this real opportunity. However, in addition to all the new proposals, it could also draw attention to the quality of the existing POS in Mumbai. It is important to propose new ones; at the same time, it is also essential to uplift the quality of the existing POS to match set standards. Factors such as public amenities, benches, landscape, shelter, lighting, and safety shall be measured, and the initiative to improvise upon it shall be one of the strategies. Mumbaikar's voice needs to include their idea of an Open Mumbai; their suggestions and comments on the present POS are something the research will focus on in the empirical chapters. The chosen literature reviews provide an in-depth understanding of the two critical aspects of POS in Mumbai: the impact of policies and the proposed strategies that can be adapted In the next chapter, the research will progress to understand the policies that have led to flourishing cities with great POS ratios.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

68

CASE STUDY: a. GLOBAL COMPARISON

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

69 07

70

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

‘If you see a city with many children and many old people using the city’s public spaces, it is a sign that it is a good quality place for people.’

- Jan Gehl (Life between buildings, Stubbs, 2020)

Figure 7a.1: People enjoying a sunny afternoon in Richmond park, London (Source: Katie, 2017:online)

7a.1. London, United Kingdom

Introduction: Mumbai aspires to be counted among the leading global cities, but its lack of POS proves one of its greatest downfalls. This failure seems more prominent compared to London, New York, and Chicago. Mumbai is inevitably compared to London as both cities are their countries' financial and commercial headquarters. Both cities display diversity in their people, employment opportunities, growth, and, most importantly, high real estate values. There are several other attributes that Mumbai shares with London: cosmopolitan ethos, strong work ethic, a reasonably good commute system, and more safety for women compared to other cities in the country (Prabhakar, 2022) It would be only fair to compare their public realm to evaluate the approach in both cities' POS. In this chapter, we shall briefly analyse London's POS and the measures the city adapts to maintain and increase the same.

London

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

71

Mumbai Figure 7A 2: Demographics comparison between London and Mumbai (Source: London vs Mumbai, 2021:online)

Data:

Public spaces are London’s living rooms. They are where Londoners walk, congregate, eat, socialise, meditate, and celebrate. A network of parks, canals, reservoirs, and riversides adorns London's landscape. When we think of London, and its public realm, its garden and green spaces strike a chord with all. With over 3,000 parks and public open spaces, they cover about 18% of London, which is more than the coverage area of its railways and roadways combined (Satterthwaite, 2022) With its spread of large central parks, it also has many smaller public parks across the city that are accessible from surrounding neighbourhoods. For instance, Kingston, one of London’s 32 boroughs, has 183 parks, gardens, recreation grounds and nature reserves. Open spaces within the Square Mile have increased significantly over the last 70 years (Open Spaces Committee, 2015) In 1927, there were just three surviving public open spaces, each of which had passed into the Corporation’s care years before, plus some churchyards and disused burial grounds. Today, there are more than 376 open spaces in the City, not counting private gardens, including 4 Historic Parks and Gardens and many churchyards (Open Spaces Committee, 2015). This totals approximately 32.09 hectares, of which 25.66 hectares is public open space; the existing day-time population of 428,000 means that the target of roughly 0.06 hectares per 1000 weekday day-time population is being met (Open Spaces Committee, 2015). All of these account for the current 31.68 square meters of open space per person, which is relatively high compared to Mumbai. Per the new plan, the POS in London is divided into categories (as seen in the table) based on their size and location. This classification instead makes it convenient for authorities to administer and for policy-making purposes.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

72

Figure 7a 3: The data map for London shows Designated Open Space (Source: Planning data map, 2022:online)

Open space categories Size guidelines Distance from home

Regional Parks 400 hectares 3.2 to 8 km

Metropolitan Parks 60 hectares 3.2 km

District Parks 20 hectares 1.2 km

Local Parks and Open Spaces 2 hectares 400 m

Small Open Spaces Under 2 hectares Less than 400 m

Pocket Parks Under 0.4 hectares Less than 400 m

Linear Open Spaces Variable Wherever feasible

Table 7a.4: The London Plan Open Space Hierarchy (Source: Open Spaces Committee, 2015:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

73

The London Plan:

The following two definitions have guided sites included in the Open Space Strategy: The government’s Planning Policy Guidance Note for planning for Open Space, Sport and Recreation (PPG 17):

Definition of Open Space in PPG17- Open Space is defined in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 as land laid out as a public garden or used for the public purposes of public recreation or land which is a disused burial ground.

The Mayor’s London Plan:

Definition of Open Space in the London Plan- All land use in London that is predominantly undeveloped other than by buildings or structures that are ancillary to the open space use. The definition covers the broad range of open space types within London, whether in public or private ownership and whether public access is unrestricted, limited or restricted

The London Plan sets the spatial planning framework for 2031 London and is prepared by the Mayor of London. The proposed London plan aims to protect and promote public open spaces and suggest strategies to increase them. It aims to create a uniform strategy that all Boroughs can implement to create and enhance open spaces (Open Spaces Committee, 2015)

The Mayor supported London in being declared the world’s first National Park City in July 2019 and aims to make more than 50% of the city green by 2050 (Shenker, 2017).

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

74

London Mumbai

Figure 7a 5: Demographics comparison diagram between London and Mumbai indicating London with a higher quality (Source: London vs Mumbai, 2021:online)

Figure 7a 6: Leisure comparison diagram between London and Mumbai indicating London with a higher component (Source: London vs Mumbai, 2021:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

75

Figure 7a.7: An early morning overview of Hyde park, a widely used public open space in central London, UK, 2014 (Source: The National Police Air Service,2014:online)

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

76

Key findings:

• The National Policy and Planning Framework (NPPF) sets out the need to assess the quality and quantity of open space. This qualitative assessment is crucial to set high standards for the upcoming POS. It is not just the expanse of POS but also the character and calibre of a space that adds value to its urban fabric.

• The current Mayor has committed to launching a Public London Charter of rights and responsibilities for users, owners, and managers of public spaces, to ensure that everyone understands the rules and restrictions of public access and use of these spaces.

• Most parks in London are owned, managed and funded by London boroughs, and some by other public bodies and environmental charities, which makes the responsibility clear and thus avoids conflict between bodies.

• There are dedicated fund allocations for green strategic projects and maintenance of the present POS (Parks and green spaces, 2022).

• To avoid misuse of space and reduce anti-social activities, strict laws on begging or sleeping in POS are practised.

• A well-planned CCTV surveillance generates a sense of security and safety around most major POS.

• The City of London Tree Strategy states that there are approximately 2,400 trees on both public and private land, many of which are essential in terms of visual amenity and biodiversity.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

77

Conclusion:

Post-visiting the city of London on multiple occasions in the past year and observing its public realm has helped to analyse the impact it generates. As a user, it is indeed exciting to see the distribution of POS in the city with diverse sizes, functions and design characters. In addition to the government initiative and strategies being implemented, how users treat these spaces is most significant. If people understand and value its presence, it does impact future policymaking and efforts made at administrative levels. On weekends you see families and groups of friends enjoying a day out, and more so ever in summers, these become active hubs of social interaction. City parks are buzzing with activities, cultural events, fairs for children and entertainment venues. It is always the people who decide the value of urban space, and how its users utilise it defines its true purpose. It was observed that since most of the larger parks are centrally located and visible from the busy streets, it evokes a sense of safety and security at all times. This leads to enjoyment of the space without much hesitation. Although, as seen in the data, many eastern boroughs are deficient in their public realm, efforts are being taken by the council to upgrade the same. Another important factor contributing to the quality of space is the clear signage, which leads to easy navigation. This is one of the key highlights that help the millions of tourists visiting the city of London. Factors like metro and bus connectivity, dedicated bicycle lanes and wide footpaths near most public spaces add to the memorable experience created.

On the other hand, in Mumbai, reasons such as encroachment, commercial development, and lack of security are vital reasons for its failure. If the safety of people is compromised, they will be unable to enjoy leisurely places. The way embankment area is being developed in London; even Mumbai has scope to unify its coastal stretch to form a continuous linear Public realm.

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in Mumbai and its opportunities

78

People and Public Open Spaces: Analysing the POS in

and its opportunities 79 05 06 07 07 08

11 12 13 14 15 16

Mumbai

09 CASE STUDY: 10 b. QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

7b.1 Introduction: