Preserving the Past

Honoring architectural conservator Aaron Wunsch ’92

College Finances

How Fords are paying it forward

The Magazine of Haverford College

A Second Shot

Lauren Paprocki ’26 finds her true sport and a global team

Preserving the Past

Honoring architectural conservator Aaron Wunsch ’92

College Finances

How Fords are paying it forward

A Second Shot

Lauren Paprocki ’26 finds her true sport and a global team

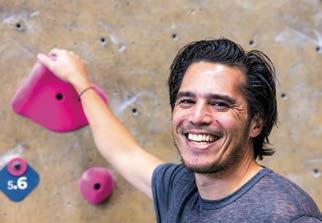

The incredible adventures of Robert Ocampo ’04

Editorial Director

Dominic Mercier

Editor

Jill Waldbieser

Class News Editor

Mara Miller Johnson ’10

Copy Editor

Colleen Heavens

Photographic Director

Patrick Montero

Graphic Design

Anne Bigler

Vice President for Marketing and Communications

Melissa Shaffmaster

Associate Vice President for College Communications

Chris Mills ’82

Vice President for Institutional Advancement

Kim Spang

Contributing Writers

Charles Curtis ’04

Lini S. Kadaba

Eils Lotozo

Jason Nark

Patrick Rapa

Ben Seal

Anne Stein

David Silverberg

Contributing Photographers

Gabbi Bass

Holden Blanco ’17

David Sinclair

Julia Vandenoever

Haverford magazine is published three times a year by College Communications, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA 19041, 610-896-1000, hc-editor@haverford.edu

©2025 Haverford College

SEND ADDRESS

Advancement Services Haverford College 370 Lancaster Avenue Haverford, PA 19041 or devrec@haverford.edu

Tal Galton, ’96: Celebrating Biodiversity

By Eils Lotozo

26 The Climb

Robert Ocampo ’04 has been on some of the most incredible adventures in the world, set records, and even braved Mount Everest. But for him, exploring the great outdoors is about testing his inner limits.

By Jason Nark

For a field dedicated to history, architectural preservation faces some decidedly modern challenges: inclusivity, climate change, and more. Meet some of the Bi-Co alums dedicated to finding solutions.

By Eils Lotozo

Fords who benefited from financial aid are committed to giving back to the school that helped them succeed.

By Lini S. Kadaba

In her lab and in the classroom, Associate Professor of Psychology Laura Been, a behavioral neuroendocrinologist by training, probes the connection between the brain, hormones, and behavior in rodents. Her research, which has been supported by a substantial National Institutes of Health grant, hinges on the transition to parenthood and how hormonal shifts—particularly the rise and fall of estrogen—prepare the brain to embrace new parental duties and can cause serious issues like postpartum depression and anxiety.

Every year, Been supports seniors through their thesis research and has co-authored numerous peer-reviewed journal articles with her students. In 2021, she was honored with the rarely awarded Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience Mentor Award, which has only been presented 14 times since 2000.

Been is also the director of the Bi-College neuroscience program, which has risen to become one of the most popular majors at Haverford since launching just four years ago. Across both schools, about 100 students have declared the interdisciplinary major, which draws faculty primarily from biology and psychology although those minoring in the subject may also take courses in computer science, linguistics, and chemistry.

Students pursue the major for numerous reasons, whether they plan to attend medical school or are interested in exploring the intersection between neuroscience and other fields, like law or art. “It’s a really awesome, diverse group of students,” says Been. “We’re really excited about that because we know that a diverse group of people working together and thinking about things leads to better answers to the questions we have.”

❶ Her kids’ artwork: In addition to studying pregnancy and postpartum life, Been is a parent herself. She keeps numerous family photos in her office, as well as these drawings her sons Milo and Owen made when they were younger. “We joke all the time that my sons are my unofficial lab technicians because they get dragged to the office and the lab all the time,” she says. “I think they enjoy it, and I love that they get to see examples of what I do at work outside of being a mom.”

❷ Brains: Been’s office is chock-full of brains, from the squishy stress ball variety to a series of coasters inspired by MRI imaging. Many of them

are gifts from her students. She also keeps a box full of colorful brains emblazoned with Bi-Co neuroscience branding to give to prospective students who attend the College’s information sessions. “There are brains here, brains there, and brains over there,” Been says as she gestures around her office. “We just love a brain around here.”

❸ Mentorship awards: At last year’s Lavender Graduation, which recognizes the College’s LGBTQIA+ students, Been was presented with the LaBeija Mentorship Award in recognition of her dedication to Haverford students. The print depicts Crystal and Lottie LaBeija, who founded

the first drag ballroom in New York. “That’s probably the most meaningful award I’ve ever received,” Been says. Above it sits the distinguished mentor award Been received from the Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience in 2021.

❹ Dopamine: For the past several years, students in Been’s lab have employed a technique called fast-scan cyclic voltammetry to measure the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter responsible for feelings of pleasure and motivation, in mice. “It’s really powerful, and we’re collecting some very exciting data,” she says. This framed print, which was given to her by former lab technician Jessica Maurice, depicts the lab’s

first successful collection of dopamine using the technique.

❺ Signed ceiling tiles: Scattered across Been’s lab on the top floor of the Koshland Integrated Natural Sciences Center are ceiling tiles signed by her students. Every year, after their senior theses are submitted, her students pop a bottle of champagne in the lab and purposely aim the cork for the ceiling before adding their signatures. “I make the students wear safety goggles,” Been says with a laugh. “It’s a lot of fun, and my hope is that someday the entire ceiling will be covered in signatures.”

❻ Nor’easter by Jackie Battenfield: In Branch Series,

New York-based artist Jackie Battenfield explores the gestures of tree branches and vines. Nor’easter, one of 11 works in the series, hangs above Been’s desk. “It’s two depictions of the same tree, but I love it because they look like neurons,” she says.

❼ A photo with her parents: Been is the first person in her family to earn her Ph.D. This photo with her parents, Claudia and Ken Been, was taken on the day of her hooding ceremony at Georgia State University in 2011. “It’s a very sentimental photo, and it was a big day for our family,” Been says. “My parents have been incredibly supportive of my education.”

—Dominic Mercier

LLOYD LIGHTS As the days grew darker and the end of the fall semester loomed, the beloved tradition of Lloyd Lights brought an extra dose of merriment and friendly competition to campus. Like every year, the denizens of Lloyd Hall decorated all nine of its entrances and vied for the year-long bragging rights that come with being crowned winner. A record number of participants cast a vote for their favorite in the College’s online poll, and Stokes (61-62) took the top spot with 21 percent of the votes.

Sound as art Pew fellow and Philadelphia-based artist Raúl Romero visited campus in October as part of the::sense::archive workshop, founded by Assistant Professor of Classics Ava Shirazi and Monica Huerta, an assistant professor of English at Princeton. With Romero as their guide, Haverford students delved into an exploration of sound and its transmission through various surfaces. They also collaborated on sound collages, demonstrating how sculptures and installations can influence our perception of sound.

Recognition for research Haverford received a new designation from the American Council on Education (ACE) and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The new “Research Colleges and Universities” category recognizes institutions with at least $2.5 million in research and development expenditures in an average year and is separate from Carnegie’s traditional “R1” and “R2” classifications, which require significantly higher research expenditures and doctoral degree programs. Haverford is one of 216 institutions to receive the classification for 2025.

Boxing on the big screen In December, Variety reported that Dancing in the Ring , the film adaptation of Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature Roberto Castillo Sandoval’s novel Muriendo Por La Dulce Patria Mía was picked up by Disney+. It will also receive a theatrical release in August 2025 before it becomes available for streaming. The story is centered on legendary Chilean boxer Arturo Godoy, who squared up with world heavyweight champ Joe Louis in 1939 and 1940.

Microgrants Emile Roth ’27 and Pranav Rane ’25 were the recipients of fall microgrants from the Haverford Innovations Program. Roth is creating a card game based on his summer experience with the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps, while Rane is exploring how to harness artificial intelligence as a way to store and retrieve knowledge more easily.

DIY ACTION FIGURES Students in Kent Watson’s “Some Assembly Required: Designing Objects of Play” class 3D-printed their own action figures this semester. Using the Visual Culture, Arts, and Media (VCAM) facility’s Maker Arts Space, a little childhood nostalgia, and some innovation, these aspiring fun engineers created original characters of their own design.

An alum on Broadway As Daniel Dae Kim ’90 took the Broadway stage in the lead role of the Obie Award-winning Yellow Face, a group of 150 Fords traveled to New York’s Todd Haimes Theatre to show their support. The night was a reunion for many and a celebration for all, filled with smiles, laughter, and some deliciously greasy New York slices.

The return of The Bi-College News, paper edition After a long break, the editorial team at The Bi-College News is once again producing a regular print edition. The December edition highlighted fall Plenary’s focus on equal access to health and financial resources, the history of the College’s radio station, WHRC, and another year of tangible growth at the Haverfarm. On campus, copies can be found in VCAM, the Office of Admission, and the Library Cafe. Online readers can still head to bicollegenews.com.

Gameday Giving In an extraordinary show of support for Haverford Athletics, the College raised a record-breaking $439,907 during the fourth annual Gameday Fords giving challenge in February. Support poured in from 1,209 donors—more than double the initial goal—and classes from 1963 through 2024 were represented, as well as members of the incoming Class of 2029, parents from 1996 through 2029, and every class of current student-athletes.

The semi-annual Haverthrift swap Students in search of Haverford swag and sharp looks flocked to Founders Great Hall just before winter break for the annual Haverthrift clothing swap. Established by the Committee for Environmental Responsibility, the student-led initiative focused on bringing small-scale, sustainable practices to Haverford’s campus. The swap is the perfect opportunity for an end-of-year closet cleanout or a cost-free wardrobe refresh.

For the past four years, Kripa Khatiwada ’26 has been working with an eco-friendly feminine hygiene products company and supporting the women of her home country.

In countries around the world, menstruation is viewed as a rite of passage, signifying the end of puberty. In Nepal, cultural and religious beliefs can impose a heavy toll on those experiencing this transition. Many, especially those who live in more rural areas, are forced to endure an ancient tradition called Chhaupadi.

In an effort to challenge the stigmas around menstruation she grew up with, Kripa Khatiwada ’26, ABOVE, has helped broaden the reach of a Nepalese company that employs local women to make reusable menstrual products, RIGHT

Based on the belief that menstruation is “unclean,” Chhaupadi prohibits any menstruating woman from touching certain foods, religious icons, or men, and consigns them to small sheds for the duration of the cycle. Even though the country’s supreme court outlawed Chhaupadi in 2008, as many as 15 Nepali girls and women died in a 13-year span as a result of it, some after the law was passed, according to a 2019 report by the Himalayan Times.

Kripa Khatiwada ’26, a growth and structure of cities major and data science minor at Bryn Mawr, experienced Chhaupadi firsthand while growing up in Nepal.

Despite living in Kathmandu, considered a progressive city compared to rural regions, she says, “I grew up following a lot of those traditional restrictions. When I got my period for the first time, I was put in a dark room for seven days. I went through it. A lot of other girls I knew went through it. I thought it was normal.” Her perspective changed after talking to friends who had more liberal parents, and Khatiwada has spent the past four years working to evolve the stigmatized views of menstruation in her home country. In 2020, she began working with Reusable Pads Nepal, a small company that produces eco-friendly

feminine hygiene products. Her role was to grow and manage the company’s online presence.

“It was an opportunity that combined sustainability with women’s empowerment, so I was all for it,” Khatiwada says. “Plus, I had a lot of free time because of the COVID pandemic.” As sales grew, Khatiwada approached Reusable Pads Nepal’s owners with a new idea: Why not direct some of the profits to broaden its fledgling outreach and education programs? “That way, it’s not just a business. We would also be doing something to uplift the women of our country,” she says.

Through her leadership, the company’s outreach grew well beyond Kathmandu, where most resources are consolidated, reaching into Nepal’s rural villages. Programs included basic information about menstruation as a natural, biological process and why sustainable hygiene products are better for the environment. All the programs, she says, are reinforced with a plea to remove harmful restrictions surrounding menstruation.

Even after arriving at Haverford, Khatiwada continued her work and, through funding from the College’s Center for Peace and Global Citizenship, has spent nearly every break in the academic year conducting workshops at home. Last summer alone, she estimates that she engaged more than 1,000 students while leading three reusable menstrual pad sewing workshops in three different villages. Khatiwada’s team collaborated with several village development committees that are providing funds for local women to start their own small businesses to sell the menstrual pads they create.

Khatiwada’s work with students is perhaps the most fulfilling, she says. Amid the giggles that generally accompany discussions about reproductive health with young people, she makes a concerted effort to engage young men so that they can better understand what their classmates are enduring and what she once dealt with.

“I don’t care if I can’t change the whole country’s views,” she says. “But if one girl goes up to her parents and says, ‘I learned about this today, so I will not be restricting myself anymore,’ I feel like I’ve done my job.”

—Dominic Mercier

How does a college like Haverford balance a commitment to creating an inclusive educational learning community with the exercise of expressive freedom?

The College’s Ad Hoc Committee on Freedom of Expression, Learning, and Community was created by Haverford President Wendy Raymond last year in order to identify and assess that complex relationship. With the entire 2024–2025 academic year to conduct its inquiries and deliberations, the committee issued an interim report in January.

The committee was formed following a difficult period at Haverford—and in the world at large—that the interim report describes as “multiple serious challenges: a global public health crisis in COVID-19 that has had lingering social, psychological, economic, and structural impacts; a continued quest for racial justice that precipitated a student strike and raised issues related to structural inequities on campus as well as in the nation; a year of heightened violence in the Middle East that catalyzed student activism and surfaced strong differences in perspective; and a period of overall increased political polarization in our society.”

The 16 student, faculty, staff, and alumni committee members are charged with defining “areas of concern, strength, and opportunity in advancing that aspect of Haverford’s educational mission with respect to the ways that expressive freedom and fostering a campus community in which all members can thrive advance Haverford’s educational mission.” Along with reporting its findings, the committee will recommend to the president future actions for consideration.

Preliminary findings include the committee’s assessment that Haverford is “in a period of reknitting our social fabric, lifting up our foundational ethos, and rearticulating and recommitting to our values.” The interim report identifies a number of tensions extending beyond Haverford that are affecting Haverford directly, including the tension between protected speech and fostering a productive learning environment. For example, the report asks rhetorically, “What is spirited or sharp disagreement versus ‘threatening’ behavior?” The report indicates that the committee is reviewing a number of policies, including the College’s Honor Code, noting it intended to develop “queries and recommendations for the student body to consider in its annual reconsideration” of the code.

The report invites feedback from the greater Haverford community via listening sessions organized in collaboration with governance groups, an anonymous comment form, and via email. In total, the committee will have held more than 20 listening sessions and reviewed hundreds of comments spanning the entire Haverford community before issuing its final report in June.

In an effort to guide community members through this process of discernment, the report includes eight queries centered around community principles and values, designed to stimulate thinking about learning and community. These begin with, “Am I committed to ongoing learning, critical thinking, and intellectual rigor? Do I seek truth and strive for knowledge, even when it is challenging and/or uncomfortable?” and conclude with, “Do I act responsibly and with integrity? Do I hold myself and others accountable for lapses in integrity?”

For more about the report, the work of the committee, and how to share your thoughts, go to hav.to/ogq.

— Chris Mills '82

Course title: “Japanese Book Art and Printing”

Taught by: Visiting Assistant Professor of East Asian Languages and Cultures Honglan Huang replication and transmission? What might different printing techniques teach us about our own perceptual and interpretive processes?

What Huang has to say about the course: In this class, we look at Japanese book art, from early illustrated scrolls to contemporary artists’ books, and explore a range of printmaking and bookmaking processes, such as wood grain printing and katazome (paste-resist dyeing). Through both discussions and hands-on exercises, we try to understand questions such as: What happens when we pay attention to how books are made and how readers physically engage with the books? How do we think about books and printing beyond traditional emphasis on

Huang on why she wanted to teach this class: I have always been interested in the relationship between printing and community, as well as how material books can make reading and other creative processes visible to us. The intellectual community of a classroom is a wonderful place to think together about questions like: How can a surface simultaneously

split and connect communities? How can a page hover between a record of past performance and a script to be performed in the present?

I am also excited to include a session on creative prints by Japanese women artists, inspired by my visit to the exhibition A Sign of Things to Come: Prints by Japanese Women Artists After 1950 at the Art Institute of Chicago. During this session, we discuss how these artists make use of the materiality of the printing processes, and how they negotiate with the possibilities and challenges of being a woman artist.

Huang on what makes this class unique: This class includes visits to the Special Collections at both Haverford and Bryn Mawr. Through physically engaging with materials, we think about material traces of past readers in books like fingerprints, the effects of wood grain patterns in Japanese woodblock prints, and how paper texture can participate in the construction of national and colonial identities in chirimen-bon (crepe paper books).

In addition, each class session is paired with a hands-on exercise that introduces a printmaking or bookmaking technique. Through them, students learn to tinker and troubleshoot as a maker and experience making itself as a process of experimental thinking

Cool Classes is a recurring series on the Haverblog. For more, go to hav.to/coolclasses.

In February, Haverford was once again named a Fulbright Top Producer. This is the ninth time in the past 10 years that the College has been recognized for its ability to place scholars into the country’s most prestigious international exchange program. Four young alums are currently engaged in fellowships across Africa, Asia, and Europe. Read more about their work around the globe at hav.to/o70.

Spotlighting the holdings of Quaker and Special Collections IN THE COLLECTION

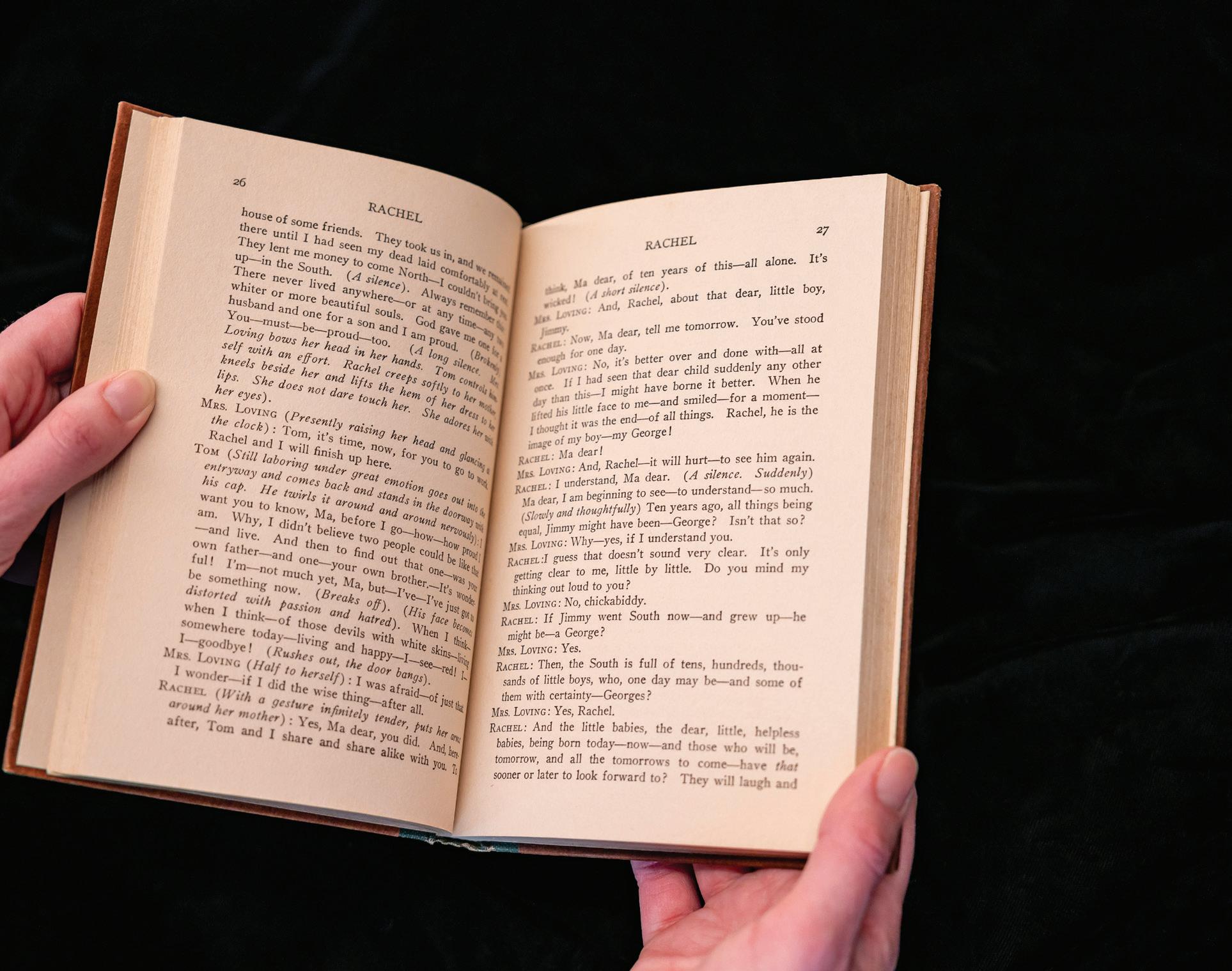

When it was produced in 1920, Angelina Weld Grimké’s Rachel: A Play in Three Acts made history as the first staged play by an African American writer and the first to be performed by an all-Black cast.

Better known as a poet, Grimké regularly published her work in The Crisis, the official NAACP newspaper edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, and numerous magazines and anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance. Grimké penned Rachel , a slim 96-page volume, in 1916 as a response to the NACCP’s call for new creative works that refuted D. W. Griffith’s 1915 Ku Klux Klan-glorifying film, The Birth of a Nation .

Originally titled Blessed Are the Barren , the play centers on Mrs. Mary Loving and her children, Rachel and Thomas. They are a close-knit middle-class Black family that moved to an unnamed northern U.S. city in the early years of the Great Migration. As the curtain rises, the Lovings look toward a more promising and prosperous future in their new home.

The titular Rachel, a sensitive and educated young woman, loves children and longs to become a mother. Later, as she witnesses the devastating effects pernicious racism has on the chil-

Four years after the 96-page play was penned, it became the first to be produced by an African American writer, and the first with an all-Black cast.

dren she tends to and learns that her father and older brother were lynched 10 years earlier, she swears off having her own. In the closing moments, Rachel asks John Strong, her crestfallen suitor, “Do you think I could stand it, when my own child, flesh of my flesh, blood of my blood, learned the same reason for weeping?”

Grimké (not to be confused with her noted abolitionist and Quaker great-aunt, Angelina Grimké Weld) hoped the play would help audiences, especially white ones, grapple with the psychological devastation of racism. It seems to have worked, with one critic for the Buffalo Courier noting in a review that there is “a terrible tragic note throughout, which compels one to think, and if possible to lend aid to try and remove the prejudice against the colored race.”

Rachel was first produced by the NAACP’s drama committee and performed in 1920 at Miner Normal School, a Washington, D.C. teachers college. The following year, it was staged in New York’s Lower East Side before traveling to Cambridge, Mass. In more recent years, Rachel has been performed at Spelman College, in London, and, in 2020, at Philadelphia’s Quintessence Theatre. Despite its age, the play remains as relevant as ever.

Seniors Emmett Huiskamp and Ellie Baron turn finals week into a performance art piece.

very semester as finals loom, students across the country turn to caffeine and sheer will to power themselves through marathon study sessions. An affront to the physician-recommended eight hours of sleep, the all-nighter, for better or worse, is a quintessential college experience.

ESince their sophomore year, Ellie Baron ’25 and Emmett Huiskamp ’25 regularly decamped to the Dining Center’s basement to complete their finals in a 24-hour period. They say their tradition, which went on to become a piece of performance art called Noon to Noon, is both an academic necessity, a commentary on higher education’s norms, and an exhibition of the absurdities of our society at large.

“As a sociology major, I have a lot of critiques about the way we treat work and treat our bodies in this society,” Baron says. “In many ways, [Noon to Noon] is a critique of the system we’re in and a society that requires us to put our well-being on hold to get massive amounts of work done.”

What began as a dare two years ago, Baron says, evolved into a piece of performance art through funding from the John B. Hurford ’60 Center for the Arts and Humanities. In mid-December, as the fall semester wound down, Baron and Huiskamp moved Noon to Noon to the Visual Culture, Arts, and Media Center (VCAM), livestreaming their 24-hour cram session on YouTube and

inviting students across campus to join them in solidarity or tune in over the internet.

“People would come by to work with us for an hour at a time,” says Huiskamp, an English and fine arts double major. “But it was really just Ellie and I, for at least the bulk of the time, in the basement, slowly going insane.”

Between noon on December 17, 2024, and noon the following day, the duo welcomed nearly 30 fellow Fords to VCAM’s media production and object study space for anywhere between 30 minutes to 22 hours to complete their work in solidarity.

“ IT ALMOST FELT LIKE PEOPLE THOUGHT WE WERE RUNNING A MARATHON, AND THEY WERE THERE TO SAY, ‘YOU CAN DO IT!’

—Ellie Baron ’25

”

There were ample snacks provided by the Hurford Center funding, including the mother of all-nighter foods, chicken-flavored Top Ramen. Over the course of the project Huiskamp downed six packets, although not entirely happily. “I will eat ramen in my day-to-day life, but it definitely plunges you into a certain feeling,” Huiskamp

Study sessions in the VCAM, TOP LEFT, became art, thanks to the innovation of Ellie Baron '25 and Emmett Huiskamp '25, BOTTOM LEFT.

says. “It doesn’t feel good to eat.”

They marked the passage of time with hourly group selfies taken with an instant camera and a running list of completed finals. Huiskamp, who opted to wear a dapper suit and freshly shined shoes, became a canvas for time as he became increasingly rumpled throughout the night and added a pithy sticker to his shirt every time he completed a final.

Among the Fords joining them was Amelia LaMotte ’25, who, as a fellow English major, heard Huiskamp talk about his Noon to Noon experiences in their junior seminar. LaMotte arrived at 6 p.m. expecting to stay for just a few hours, but remained through the night. In that time, she says, she completed her most pressing matter: the annotated bibliography for her thesis focused on the archive of Phillis Wheatley, widely considered the first Black author of a published book of poetry. LaMotte, who struggles with bouts of insomnia, is no stranger to sleepless nights, and says she was bolstered by the sense of camaraderie among those also laboring through the night. “I now feel very close to everyone that was in the room with me, especially during the final hours,” LaMotte says, attributing that feeling to the shared sense of “self-inflicted suffering.”

Despite the more grueling aspects of Noon to Noon, students still managed to find some bright spots. “This iteration was really fun because we got to see so many of our friends through it all,” Baron says. They even received encouragement from Huiskamp’s high school friends who tuned into the livestream. “It almost felt like people thought we were running a marathon," she says, “and they were there to say, ‘You can do it!’” —DM

The Cornell communicator will lead an expanded effort to build brand visibility.

Melissa Shaffmaster joined the Haverford community as the College’s inaugural vice president for marketing and communications in mid-January. She came to Haverford from Cornell University, where she served as senior director of strategic communications in university relations.

“Melissa quickly distinguished herself in our nationwide search for this new position, which will lead College Communications with an expanded charge around enhancing Haverford’s visibility and public profile,” noted Haverford President Wendy Raymond in a message to campus. “She impressed the search committee—and me—with her deep and broad experiences at Cornell, spanning internal and external communication systems, navigating emergent issues requiring crisis communications, and helping a wide range of publics understand the institution’s mission and contributions to the greater good.”

During the search, Shaffmaster evidenced considerable familiarity with Haverford’s history, values, culture, and people, and expressed a deep affinity for, and commitment to, the distinctive value of residential liberal arts colleges. “I’m delighted to join President Raymond and the Haverford College team in service of an institution renowned for its commitment to intellectual rigor, ethical leadership, and a strong sense of community,” Shaffmaster says. “Haverford’s values resonate with me both personally and professionally, and I am honored to become a part of such an esteemed institution.”

Her role at Haverford will include managing the College Communications team, a group of 10 professionals with a portfolio that connects Haverford with a broad array of audiences. From admission and alumni to the general public that’s reached via external news organizations, “Team CoCo” (as the group refers to itself) operates platforms including the College website, Haverford magazine, social media, and myriad departmental publications.

“I look forward to helping share the College’s unique story, bridging its rich history as one of America’s leading liberal arts colleges with its future ambitions,” Shaffmaster says. “Haverford’s legacy of shaping principled leaders is inspiring, and I’m excited to contribute to its continued impact and excellence.”

In her announcement, President Raymond noted that Associate Vice President Chris Mills ’82, who has led College Communications—now renamed Marketing and Communications—since 2007, will continue to be part of the communications leadership team. Mills has been deeply invested in elevating Haverford’s public profile and its distinctive approach to liberal arts through innovative initiatives like the Kim Institute for Ethical Inquiry and Leadership, a centerpiece of the College’s strategic plan.

Shaffmaster has led strategic communications at Cornell since 2015, overseeing teams that manage communications strategy, institutional messaging, issues management, social media, and visitor relations. She has led a variety of high-visibility communications and marketing initiatives that helped to advance Cornell’s reputation as a top research institution. Before joining Cornell, she held roles in public affairs and government relations. She has served as a board member of Gadabout Transportation, a nonprofit service for older adults and people with disabilities within Tompkins County, N.Y., since 2018.

She received her bachelor’s degrees in English literature and visual communication from Lycoming College and a master’s degree in strategic communication from American University. A Pennsylvania native, Shaffmaster says she’s eager to return to the area with her husband, Christian, and their daughter. —CM

An online advice column offers counsel through verse.

J‘‘ POETRY GETS MADE FUN OF A LOT— THAT IT’S PRETENTIOUS OR JUST FOR PARTICULAR KINDS OF PEOPLE. BUT THE WAY I THINK ABOUT IT IS, EVERYONE HAS THE CAPACITY TO USE POETRY TO ENGAGE IN THE WORLD DIFFERENTLY.

—Joshua Moses, professor of anthropology and environmental studies

”oshua Moses is a professor of anthropology and environmental studies at Haverford, but he’s always had an affinity for poetry. When he met a like-minded scholar in his post-doc program at McGill University, a bond was forged. For more than a decade, Moses and McGill University neuroscientist Suparna Choudhury have corresponded using poetry. Through the pandemic, illnesses, and life’s more typical ups and downs, they would email and text poems, or passages from poems, that seem appropriate or uplifting.

Then about five years ago Choudhury suggested to Moses that they share their exchanges with a larger audience. Her thinking was, “We do this for one another and it gives us so much solace, why not make this a wider offering for our friends or the public, so that people can get a vicarious experience from exchanges of poetry?”

They did even better: After securing funding and hiring a web designer, they launched Poetry Clinic, an online advice column. Each month, a poet-in-residence responds to four or five reader letters with what the site calls “a poetic tonic.” Topics include romance, parenting, illness, death, and how to stay grounded or keep hold of positive feelings. The responses begin with general thoughts and counsel, followed by poems and passages relevant to the issue.

“There’s something about the letter-writing form that feels intimate and close, but also amenable to wider audiences,” Choudhury says.

The site is also a way for Moses and Choudhury to engage poets and artists in the daily lives of people. “Poetry gets made fun of a lot—that it’s pretentious or just for particular kinds of people,” Moses says. “But the way I think about it is, everyone has the capacity to use poetry to engage in the world differently. In a small way, Poetry Clinic brings poetry into our daily lives, to help us understand the world and use our imagination.”

At a time when many people feel isolated, scared, and anxious about the world—feelings that students have expressed in the classroom— the site offers solace, ideas, and encouragement. “I think the arts have an important and often

Professor

forgotten role in people’s well-being, especially at the present moment. With climate catastrophe and economic precarity, people don’t know where to turn,” Choudhury says. “Poetry offers a sense of solidarity, it connects people, and the open-endedness gives form to complex and overwhelming emotions.”

Moses and Choudhury have sponsored in-person events to further engage the public, including a collaboration in Montreal with McGill’s Critical Media Lab. Last September, at Haverford’s Hurford Center for the Humanities, Choudhury spoke about “Ecology, Arts, and Survival” at the (Re)growing a Living Culture series. More Poetry Clinic events are planned at Haverford and in Philadelphia this coming year.

“There are certain lines or phrases in poetry that are a reminder that people are much bigger and full of possibilities than they think they are, and that we live in a world that tells us otherwise,” says Moses. “Poetry’s a more fundamental way of showing us how mysterious and insane and beautiful the world is at once, and that in the end, poetry is a necessity, as many poets have pointed out.”

View Poetry Clinic letters at poetryclinic.org.

—Anne Stein

Even in the dead of winter, there’s one place on campus that’s always lush and vibrant: the Haverford College Arboretum greenhouse, which is a temporary home to hundreds of student plants over winter break. “About half our greenhouse is student plants,” says Charlie Jenkins, one of three horticulturalists charged with caring for them.

The Arboretum has offered plant-sitting services for more than 35 years, ever since Florence Genser ran it, according to Carol Wagner, a longtime Arboretum horticulturist who worked with Genser and retired in January 2023. “Florence came up with the idea that every incoming student should get a free plant as an introduction to the Arboretum,” Wagner says. “She also started offering to watch plants over winter break.”

Haverford, various graduate schools, and, after he became a professor of religion at Canisius University in Buffalo, even COVID-19. “A week into the pandemic shutdown, they announced that we had to get permission from security and the provost to even come to campus,” he says. “It was the first thing I rescued from my office. It reminds me of Haverford and all the adventures I had there.”

The past couple years, this service has been pretty popular, says Jennie Kelly, the Arboretum’s program coordinator, with 407 student plants spending last winter break. The all-time high was 500 plants in 1990. “We try not to turn people away,” she says. The Arboretum staff will watch any houseplant, not just those given out at the beginning of the year. The most they’ve ever cared for from a single student was 32.

They can’t revive a dead plant. And students who are dropping a plant off are encouraged to take proper precautions when transporting them, such as placing the plant inside a bag to keep it warm. One of the most common reasons a plant won’t make it is because of cold damage. If a plant doesn’t make it, the Arboretum does have replacements on hand, left behind by students who have graduated and given their plants back.

Others, like Jonathan Lawrence ’93, still have their original first-year plants. “I think it’s called a ponytail palm,” he says. “I brought it back home every summer and it lived with my parents.” The palm survived

WHAT: The Haverford Debate Society gives students a chance to sharpen their rhetorical skills in a competitive but supportive environment, with ample opportunities to participate throughout the year. It was founded in spring 2023 by Jonah Paterson ’26. “My high school debate mentor told me, ‘Jonah, debate isn’t about winning. It’s about making better people,’” Paterson says. “I’ve tried to ensure the club is structured along those lines. I want people to come to practice or a debate round, learn something, and have some fun.”

WHY: Debate has long been an important part of life on campus, beginning with the Haverford Loganian Society in the early 1900s, one of the College’s first and longest-running clubs. The Feb. 13, 1938, edition of The New York Times even included a note about the College’s all-male debate team facing off with Swarthmore’s all-female team. Paterson, who was a member of his high school debate team, founded

The Arboretum staff has heard from several students who have had their plants for 20 years or more, and one even reached out when the plant turned 18 to inquire if it could apply to Haverford. The request was denied, says Kelly, but shows how much students care about their plants.

“It teaches students to be responsible for something,” says Wagner, and fulfills Genser’s vision of helping the Arboretum staff connect with students. They’re happy to offer re-potting, pest control, and other plant care and advice throughout the year. “It’s nice to see when a student comes in with a really healthy plant,” Jenkins says.

Although sometimes, looks can be deceiving. “Once,” Kelly recalls, “someone gave us a plastic plant.”

—Jill Waldbieser

the club to continue that intellectual tradition after a previous iteration was dissolved during the COVID-19 pandemic.

WHO: The society is open to all Haverford and Bryn Mawr students, regardless of their experience level. “Jonah has been doing debate for years, but I didn’t start until my sophomore year of college,” says society co-head Sarah Weill-Jones ’26. “We have a lot of members with varying level of experience. There are people who did policy debate in high school for years and other people who are just curious about debate.”

WHERE: The society holds practices in Union Building once a week and competes in weekend American Parliamentary Debate Association events up and down the Northeast Corridor—and occasionally, much further afield. As the society grows, Weill-Jones says, it hopes to host tournaments at Haverford in the future.

Gary Kuehn: In Situ is the largest American exhibition of the minimalist sculptor’s work in nearly 40 years. The exhibition, which was on view through March 7 in Haverford’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, included more than 20 of Kuehn’s sculptures and works on canvas created between 1962 and 2016. It was organized by Sid Sachs, who for more than two decades served as the curator for Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery and the Philadelphia Art Alliance, both at University of the Arts.

Kuehn received his MFA from Rutgers University in the early 1960s, where he studied under eventual colleagues including Roy Lichtenstein, Allan Kaprow, Robert Watts, and Robert Morris. It was at Rutgers that he was introduced to the Fluxus movement, which emphasized blending different artistic media, and attended the very first happenings on his mentor George Segal’s New Jersey farm. His experiences at Rutgers and his work as a roofer and iron worker informed his relationship with the workaday materials—straw, twigs, tar, and plaster—that are prevalent in his work.

Reacting against the prevailing rigid trends in minimalist sculpture, Kuehn developed innovations with fiberglass and wood that sag and respond to gravity and experience. Sections of some of his sculptures are overly secured by large bolts, while others seem to extrude flowing liquids. In creating such situations, Kuehn’s works produce a visceral sympathetic response in viewers.

Support for the exhibition was provided by the John B. Hurford ’60 Center for Arts and Humanities.

hav.to/aw2025

Registration opens in April. Email alumni@haverford.edu or call (610) 896-1004.

Gary Kuehn: In Situ included 20 of the artist's sculptures and works on canvas created between 1962 and 2016. Together, they highlight Kuehn's place in American art history.

FINE ART

A creative coast-to-coast collaboration between a poet and photographer, Ghost Book turned out to be haunting in more ways than one. BY

NANNE STEIN

orthern California poet Marc Zegans ’83 was preparing for the Manship Artists Residency, which would take him across the country to Starfield, a 15-acre estate in Gloucester, Mass. “I expected to spend a month there writing and doing some poetry readings. It seemed like the perfect opportunity,” says Zegans, who has published seven collections of poems.

Then COVID-19 turned things upside down. The residency closed its doors to out-of-state

visitors, allowing only brief, solo visits from local artists. Rather than treat the residency as a total loss, however, Zegans came up with a novel idea: a virtual residency and collaboration between himself and an on-site photographer. The result is the just-published fine art volume Ghost Book

The premise is exactly what Zegans pitched back in 2020: “What if we imagined there was a poet on the property, and that a photographer with access to the grounds discovered and documented that presence?”

The 15-acre estate appeared abandoned during the COVID-19 pandemic, and made the perfect canvas for photography that explores the interplay between dark and light.

Once he received the greenlight for his so-called “Ghost Residency” project, Zegans pored through artist portfolios looking for the right match. When he saw the work of Gloucester photographer Tsar Fedorsky, he thought it was fantastic, and decided to give her a call.

“I explained the project and there was a gasp of delight,” he says. “She lives just down the street from [Starfield], had never been, and always wanted to. We agreed we’d go forward.”

Fedorsky shot over the summer of 2020 when no one else was on site. A few of her photos showed staged scenes—rumpled bedsheets, a glass of water, an open book—that gave the sense someone was there. But those interventions by Fedorsky were few and far between, and most photos in the book’s three sections—“Stone,” “Ghost,” and “Life”—focus on the house and grounds, and the interplay between dark and light.

Fedorsky and Zeagans winnowed hundreds of photos down to the curated collection found in the book, and shared them with a colleague, Samantha C. Harvey, professor of English at Boise State University. In an odd twist, Harvey called Zegans to tell him she’d found an apparition in one of the images: a face wearing a muslin mask worn during the 1918 flu pandemic.

“Samantha found the first ghost,” says Zegans, “and then we began finding more. From then on, the book took on a very different dimension.” Harvey wrote the book’s foreword.

“We started the project with a premise of noticing things that were there, and what changed was this whole epiphenomenal quality,” Zegans says. “If you look carefully, one starts to see things that one wouldn’t anticipate in a photograph.”

There are just 100 copies of Ghost Book, including a standard edition (Haverford Libraries is home to one) and a muslin edition, which are targeted at museums and library special collections.

“It’s a book that’s very rare in its attention to detail,” says Zegans. Both editions feature museum-quality prints for both the front and rear cover images, and each copy is hand-bound and hand-stitched. The end papers are tangerine-colored and embossed with a handspun pattern so the reader feels the texture of the page, and the rest of the book is printed on heavy archival paper. A handmade muslin bag hemmed with red vintage thread holds the muslin edition, which is housed in a stamped, clamshell box.

For Zegans, the residency that wasn’t became a cross-country collaboration that redefined what a residency can be. “It turned into a really intense, intimate, and evolving collaboration which ultimately involved dozens of people, through funding, writing, and editing. It has created a community, including a variety of fellow Fords, and life around it.”

For more information, go to: tsarphoto.com/ ghost-residency.

The first time Aidan Un ’11 walked into a Second Sundae dance party, he knew he wanted to make a film about it. “Between the lights and the mirrors and the moving bodies, I just had this feeling like I had stumbled onto a treasure trove of images,” he says.

Half diner, half night club, Silk City at Fifth and Spring Garden streets in Philadelphia has long been a magnet for enthusiastic crowds and eclectic musical events. In particular, Second Sundae, held on the second Sunday of every month since 2011, is beloved for its high-energy dance floor and its old-school dance and hip-hop soundtrack.

Un, an independent filmmaker entrenched in the Philly arts scene, spent more than a decade capturing the sights and sounds of the Second Sundae scene for his gorgeous and delightfully atypical documentary You Don’t Have To Go Home, But… In it, he sets aside wide swaths of time to soak in the kinetic atmosphere. The shots are mostly handheld and visceral, full of waving arms, shuffling feet, and smiles lit up by disco ball flashes. The dancers spin and battle and get lost in the music.

Even outside the club, dance is never far from the minds of the film’s major players. We see Jenesis, a dancer with formal training, in a studio taking a class. We walk down the street with neighborhood-famous Mach Phive as he wonders aloud what it would be like to dance on the checkered floor of a shuttered pizza shop. And we check in now and again with an older gentleman who goes by Shiny Dancer and prefers to put in his earbuds and groove on Spring Garden Street.

Un is especially fond of the off-the-cuff interviews shot outside the club at 2 a.m. when the dancers are sweaty and tired but beaming. “I think that’s just the joy, whatever state of ecstasy folks have reached at the club that’s making them talk,” he says.

Un, who grew up in France with a Korean father and French mother, had never visited Haverford before starting school there in 2007. “I didn’t know what a Quaker was,” he says with a laugh. At Haverford, Un majored in philosophy, but it was a school project for an anthropology course that steered him toward his current path.

Former Assistant Professor of Anthropology Jesse Shipley offered his students a video alternative to the traditional final term paper. Intrigued, Un and a classmate went around interviewing students, professors, dining hall workers, and more about their various frustrations with life at the College.

“When I look back on it now, it seems a little crazy that people were willing to be so open, and to share so honestly,” Un says.

“It was just really fun for me, discovering what filmmaking could be like,” he says. “It was all extremely new, and the realm of possibilities was infinite—or at least as much as I knew how to do on Final Cut 7 at the time.”

After college, Un made a short film about a Cambodian man who ran a French bakery in South Philly. “No one paid me to do it,” he says. “I just had a small camera, and I wanted to see if I could make another film.”

Encouraged, Un dove into the city’s art world and started making short films on a shoestring budget for artists in the theater and dance scenes. Eventually, it became his full-time gig. He was working on a film for Mark Wong ’05—artistic director of the Hip Hop Fundamentals dance company—when he was first turned on to Second Sundae.

“I wanted to make a record of what it looked like, what it felt like, what it sounded like,” Un says. “What clothes people were wearing. How they had their hair. What the club looked like. I just wanted to take that slice of time and to immortalize it.”

The result, captured on film, has gotten a warm reception. Un screened You Don’t Have To Go Home, But… at the Asian American Film Festival and BlackStar Film Festival, where he took home the Audience Award for Favorite Feature Documentary.

But for the filmmaker, the real prize has been the reaction he’s gotten from his target audience. “Just to have dancers come up to me [after a screening] and tell me it touched them, that it reminded them of something, that they were happy to just see this documented,” he says, “It just really meant everything to me.”

—Patrick Rapa

Most people would consider the rigors of fertility treatment, then giving birth to and raising twins enough of a radical life change. Not Megan Williams ’91, whose follow-up move was to enroll in the Philadelphia Police Department at age 45.

In her publishing debut, One Bad Mother: A Mother’s Search for Meaning in the Police Academy (Sibylline Press), she writes about struggling to find an identity beyond being a parent: “Motherhood had made me dull and ordinary. I applied to the police department because I wanted to be extraordinary.”

Struggling to conceive, giving birth at 29 weeks, and then dealing with not one but two newborns with a slew of health

issues took a toll on Williams, and it isn’t surprising that she wasn’t enthralled with every aspect of motherhood. But, she writes, “I wasn’t allowed to say this. Nobody had told me that when I became a mother, I would always feel trapped. Conflicted.”

Her decision to abandon a career in academia and apply to the police academy, a grueling two-year process, may sound like a self-inflicted punishment, or at the very least, an unusual sort of midlife crisis. But for Williams, it was a much-needed escape and opportunity to receive recognition for something other than raising children. Pursuing that dream, however, never seemed to quite alleviate the guilt that’s evident in the title of her memoir, and she writes openly and vulnerably about her experiences in and out of uniform.

Williams, who lives in Bellingham, Washington with her husband and twins, spoke to Haverford magazine writer David Silverberg about why she decided to write about a subject very few parents discuss publicly.

David Silverberg: You could have done a lot of things to shake up your life or career. Why the police academy?

Megan Williams: I had a chance encounter on a track where the Montgomery County Police Department was running their physical fitness test. I was there coaching running for a local high school, and an officer told me I should apply. I was at an impasse in academia at that point, having given up my lecturer position at Santa Clara University when we moved. If I wanted to stay in academia, I would have had to begin again—write another book, publish all the articles. The police gave me the idea that I could begin again, reinvent myself. I wanted to do the canine unit. I love dogs and have trained several therapy dogs to go into schools in the Reading to Rover program.

DS: Can you elaborate on what you meant when you wrote, “Did I want this particular job, or did I want moments in my life that would allow me, because of their violence and immediacy, to forget I was a mother? This was the question I didn’t have an answer to because its very existence was shameful.”

MW: That was a really hard sentence to write because you’re supposed to love every moment of being a mother. Our society is very, very critical of, say, what baby food you use, of the hundred rules of being a mom. If a kid gets left in the car, the first question is always, “Where’s the mother?” Not, “Where’s the dad?” And for me, that created a fair amount of anger. I felt like I was in a box that I couldn’t get out of, and I think part of the appeal of the police academy was the whole physicality of it. I’ve always balanced my life between the physical and the cerebral. When I was getting my Ph.D. in English, I was coaching high school running full-time. The police offered me a chance to lean into the physical.

DS: It took you close to two years to try out for the police academy, and during that time you dealt with a lot of pressures you had never faced before. Was that overwhelming? MW: It was a welcome distraction because they set up all of these tests, and then they tell you that they’re very difficult to pass. So when I did pass them, I felt this great feeling of success, of validation. It was something that made me realize, “Hey, I could be really good at this!” But the arc of this book is realizing that you can have self-worth outside of any test at all. You can

just be holding a sick kid or being kind to someone and you can be a good person.

DS: What would you say was the most difficult part of your experience with the police academy and why?

MW: To me, the toughest part of the tests to get into the academy was the realization that it didn’t operate as a meritocracy. My whole life, I believed that if I worked hard enough, I could be the best. Then I got to the end of the 2-mile test. I knew I could win, but I also knew that if I did, it would put a bull’s-eye on me. The last thing you want in the police academy is to stand out as different, and I already was different because of my previous career path, gender, and age. My experience there was all about conformity. I’d never been in that position before, where I deliberately didn’t try my hardest because there were larger forces of gender, age, and class at play. Not trying to win absolutely gutted me because it marked the beginning of the many ways I would have to change if I wanted to become an officer.

CHRIS FILSTRUP ’66 AND JANE MERRILL: The Turban: A History from East to West (University of Chicago Press)

For a simple strip of cloth, the turban has a vast and detailed history, and has played a role in religion, fashion, and culture. This narrative traces the head covering through history and geography, as it moved from the Arabian Peninsula to Europe and the Americas. The story also highlights the versatility of the turban, which is prominent in the Sikh religion, Black culture, Renaissance art, and contemporary fashion. It’s an informative and engaging look at an accessory that has meant, and continues to mean, many different things to many people.

DS: What message do you hope readers take away from this book?

MW: My title pretty much says it. I took the label “One Bad Mother” because I wanted to remove myself from the debate. I was tired of always feeling I wasn’t good enough. With this title, I didn’t need to try to meet society’s expectations any more. I’d already failed and could now work on defining and meeting my own.

DS: Now that you’re a full-time writer, what are you working on next?

MW: I’m writing a memoir about the Great Fires of 1947 that burned down Maine’s Acadia National Park. My father’s family had to be evacuated from their house in a tank, and they had five minutes to get their belongings. I’ve been interviewing survivors of the fire, asking what they took with them. The book explores what we take from the present and hopefully into the future, and it documents some of my family drama around the house that burned down.

David Silverberg is a journalist and writing coach in Toronto who has been covering technology for more than 20 years.

DAVID LEVY ’90 AND RUTHIE LEVY: Ruthie Wonders: The Mystique of Creation (self-published)

The curiosity of children is a persistent thing, as any parent knows, but can also be an enlightening and entertaining lens through which to view the world. Levy, a prolific author and Jewish scholar, uses his 6-year-old daughter’s endless curiosity to address life’s biggest mysteries and how Judaism explains them. Guided by Ruthie, who is a co-author and illustrator, this children’s book makes the complex and abstract concepts of creation and spirituality accessible by framing them as a series of questions and answers between her and her father. In do-

ing so, it captures the childlike wonder and awe at existence that is at the heart of any creation story, making this a book adults will enjoy, too.

JONATHAN STUBBS ’74: No Clue: White American Affirmative Action Exists and Demands a Moral Revival Now! (Twelve Table Press)

Both a professor and a preacher, Stubbs describes this book as “a fact-based introduction to how law has apportioned benefits and burdens along the color line from Colonial to modern times.” His history targets one of the major obstacles to overcoming America’s racial divide, namely, the notion that modern society bears no responsibility to remedy the racial injustices of the past. The narrative accomplishes this by presenting a fact-based overview of race and the law in the United States beginning in Colonial Virginia. “It is a small contribu-

tion to truth and reconciliation in the United States,” Stubbs says. “For humans to survive through the 21st century, we need to adopt and apply the simple law of love: love all of our human extended family as we love ourselves. Or stated differently, love your neighbor as yourself.”

ANNIE KARNI ’04 AND LUKE BROADWATER: Mad House: How Donald Trump, MAGA Mean Girls, a Former Used Car Salesman, a Florida Nepo Baby, and a Man with Rats in His Walls Broke Congress (Random House) New York Times congressional reporters Karni and Broadwater had a fly-onthe-wall view of the chaos that was the 118th Congress, and in this recent history they chronicle what was, at the time, their day jobs. The stories, though, are as salacious as any fiction: the response to the January 6 attack on the Capitol Building, the antics of George Santos and Lauren Boebert, and revenge porn being shown on the floor of the House. While entertaining, this book also maps the frightening descent from democracy into extremism, and a legislative branch marked by pettiness, egomania, and a thirst for revenge.

MARCY DERMANSKY ’91: Hot Air (Knopff)

Dermansky has a penchant for the quirky, and her latest novel is no different. Fast-paced and offbeat, it follows the aftermath of a chance meeting of two couples in the post-pandemic era:

one on a first date, the other, billionaires who crash land their hot air balloon in the middle of said date. In one of many unlikely coincidences, Joannie, one of the four narrators, realizes the balloon is helmed by a former childhood crush who made it big, and his wife. The two couples then embark on miscellaneous adventures, highlighting the contrast between the haves and the have-nots in a witty, modern way.

ANDREW LIPSTEIN ’10: Something Rotten (Macmillan)

This novel, Lipstein’s third, follows Cecilie, a New York Times business reporter and her husband Reuben, new parents who flee to Denmark following a caught-on-Zoom incident that costs Reuben his job as a host for NPR. The pair hope to start fresh with a visit to Cecilie’s hometown of Copenhagen, but when she reconnects with old friends, she learns an old boyfriend is dying of a rare, fatal illness. While Cecilie hopes to convince her former flame to go through with a lifesaving operation, another member of the friend group, Mikkel, entangles himself in her and her husband’s lives. Initially taken with what he sees as Mikkel’s unrestrained masculinity, Reuben is persuaded to act the fool—shave his head, get tattooed, and more—as he attempts to emulate his new idol. After a number of twists, and deceit on behalf of all involved, the plot ends on the note you’d expect from a book whose title is derived from a Shakespearean tragedy.

PETER GORSKI ’70: The Color of Meaning, third edition (Politics and Prose)

This collection by Gorski, who is a physician as well as an author, jumps from poignant social commentary to intimate essays to poetry, but is unified by a single theme: how to create a fulfilling life and a humane society. Introspective and often humorous, the curated collection of essays and poems provides a fresh analysis of how we live, work, and care about one another, and the influence we have, both individually and collectively, on our health and happiness. This collection will make you think about what truly gives meaning to our lives, and why maintaining a hopeful attitude is key.

Teaching from an Ethical Center: Practical Wisdom for Daily Instruction (Harvard Education Press)

Can philosophical inquiry enrich teaching practice and help teachers act justly? Furman believes so, and wrote this guide to explain her methodology for incorporating it into teacher education. She illustrates the benefits of thinking philosophically in day-to-day instruction for both educators and their students, weaving in firsthand accounts and posing thoughtful exercises. She also presents philosophical inquiry as a foundation for an inclusive education because it offers continuous opportunities for reflection and affirmation. The practice encourages a focus on core values that can help educators face

challenges, including student behavior concerns and conflict management, regardless of their level of experience.

ALEX GENDZIER ’84 AND ROBERT SARVER: Warrior to Civilian: The Field Manual for the Hero’s Journey (Hachette)

Along with his co-author, a former Navy SEAL, Gendzier wrote this as a how-to for transitioning from active duty to civilian life, a task undertaken by more than 200,000 new American veterans each year. That transition has historically not been a very smooth one, as indicated by the high incidence of suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and homelessness among veterans. This

guide, the result of five years of research, is modeled after the popular literary archetype of the hero’s journey and draws on Gendzier’s ancient Greek and Native American studies at Haverford. It serves as a resource for both the practical and more abstract parts of that journey, and addresses the special challenges faced by veterans of color and those in LGBTQ+ communities. Informed by veterans, their partners, and professionals who work closely with veterans, it’s an empathetic and useful manual on a much-needed subject.

TOM NAVRATIL ’82: Dog’s Breakfast (Between the Lines Publishing/Willow River Press)

This political satire takes place at a U.S. embassy, familiar territory for Navratil, who joined the U.S. Foreign Service after graduating from Haverford and has served in American embassies around the world. His debut novel centers on

Andy Pulano, a power-hungry embassy worker who creates chaos in their host country in order to advance in his career.

When Tara Zadani, a junior officer, arrives to investigate the attempted poisoning of the ambassador’s prized Labrador, she discovers more than she set out to. The fast pacing and humor make this an easy read, and the depiction of petty squabbles and power struggles is all too authentic.

FORD AUTHORS: Do you have a new book you’d like to see included in More Alumni Titles? Please send all relevant information to hc-editor@haverford.edu.

With support from the Quinlan-Newshel Family Scholarship Fund, Emma Ganaj ’27 is able to study chemistry with a concentration in biochemistry, and establish meaningful connections with students and faculty members along her research journey.

“ Because of you, students like me can fully engage in Haverford’s intellectual community and prepare for futures that would not have been otherwise accessible. Your generosity is an investment in our potential. Thank you so much for making a difference in our lives in the Haverford community! ”

To support current-use financial aid, visit hav.to/give. To learn about endowed scholarships, contact Matt Keefe at mkeefe@haverford.edu or (610) 795-3377.

Although she came late to lacrosse, Lauren Paprocki ’26 found a community within the sport in more ways than one. BY CHARLES

Up until her freshman year of high school, Lauren Paprocki ’26 was convinced she would be a professional soccer player. In the span of just a few years, however, the New Jersey native found herself playing on an international team in an entirely different sport: lacrosse.

Since Paprocki set down the soccer ball and picked up a lacrosse stick, she has proven herself a solid defender, playing for the Haverford women’s lacrosse team while pursuing a degree

CURTIS

’04

in biology. Last summer, a chance encounter on campus led Paprocki, who is half-Filipino, to join a national women’s team for the Philippines. Now, after recovering from a knee injury she suffered last fall, she will be joining them for the 2026 World Lacrosse Women’s Championship in Japan.

Paprocki spoke with Haverford magazine about her sport switch-up, why she doesn’t feel the need to prove herself, and the importance of community on and off the field.

Soccer was her first love. I played the sport my whole life and thought I could go pro. But after my high school team won a state championship, there was a lot of pressure to win again, and I wasn’t feeling it mentally. The school’s lacrosse coach told me, “Come play for us. We wouldn’t put that kind of pressure on you.” Even though I hadn’t picked up a stick before, I was athletic, I enjoyed the sport, and I had a great team. Thanks to soccer, I had amazing footwork and that allowed me to be a great defender in lacrosse. I could barely pass and catch at the beginning of the season, but by the end, I was competing for a place on varsity. That personal growth kept me going.

She saw that same opportunity to grow at Haverford. I played in a Division III showcase and my future coach Katie Wertman ended up leading the team I was on. I decided to choose Haverford because I saw the person I wanted to be in the players on the team. I was shadowing a senior who was working for NASA and met another who was training for a marathon postgrad. She didn’t feel the need to prove herself to anyone. I never felt more accepted. I felt like a part of the community.

One fateful summer led her to international competition. I spent the summer of 2024 living on campus and working in the lab of biology professor Rob Fairman. I realized that summer that I needed to do more running to help me in lacrosse, so I was running on campus one day when I saw a ton of people out on Featherbed and Swan Fields. I spoke to some parents who were watching lacrosse games, and they told me it was the Heritage Cup, in which international teams of men, women, boys, and girls compete in tournaments. I’m half-Polish and half-Filipino, so I stopped by the Poland and Philippines tents looking to buy shirts or jerseys. Someone at the Philippines tent told me the women’s team was short on defenders and I could help out if

I wanted. So they gave me a jersey and I started playing—if you have a Filipino passport or can qualify for one, you can play for the team. I did well, and the coaches told me they were having a tryout in Colorado and to come by. I thought, “Why not?” I made it to the next phase of tryouts that was held in Maryland and I made the team as the only Division III player on the roster that would compete in Australia. If I hadn’t gone on a run that day over the summer, all of that might not have happened.

A major injury was a setback, but also, a learning opportunity. I was playing in a Haverford fall scrimmage and tore my ACL. I couldn’t play for the Philippines in Australia, but they placed third at world qualifiers so I am hoping to compete with them in the world championships in Japan in 2026. I keep telling myself this opportunity is going to come, and to focus on my recovery. This injury has forced me to go day by day and slow down, both literally and figuratively. And I get to be a mini coach on the sidelines for Haverford this season. But it’s a challenge. The players wanted me to be part of team bonding, so being in the group chats and the Snapchats, getting photos from the team while they were in Australia was hard.

Being on a national team is so meaningful.

The Polish side of my family is all located in Poland, so family events are usually spent with my Filipino family. They’re very excited for me. So this is definitely meaningful. Some people think I’m not white enough to be white, or I’m not Asian enough to be Asian. To be able to own up to my heritage and where I’m from and a culture I resonate with was something I wanted to do for me. This is who I am.

Charles Curtis ’04 is managing editor for USA Today’s For The Win and an author of the Weirdo Academy series, published by Month9Books.

‘‘ I DECIDED TO CHOOSE HAVERFORD BECAUSE I SAW THE PERSON I WANTED TO BE IN THE PLAYERS ON THE TEAM.

”

When he wasn’t studying history at Haverford, Tal Galton ’96 spent every moment he could outdoors. One summer break, he worked as a naturalist in a state park in South Dakota’s Black Hills. Another summer, he supervised teenage trail crews in Yosemite National Park in California.

After graduation, Galton ran a youth program at the Museum of Life and Science in Durham, N.C. and eventually relocated to work at Arthur Morgan School, a Quaker institution where he led outdoor trips, ran an organic farm, and taught basic biology to kids in grades seven through nine.

These days, Galton helps others learn about

and connect to nature through his company, Snakeroot Ecotours, which offers guided hikes to see local wildflowers, bioluminescent fungi, mountaintop cloud forests, and more. A writeup in The New York Times last June raved about one of Galton’s nighttime excursions in Pisgah National Forest to view displays of synchronous and blue ghost fireflies (Phausis reticulata).

Galton founded the company in 2016, and lives on a 1,100-acre communal settlement in the Black Mountains of North Carolina with his wife, fellow Haverford grad Jessica Ruegg ’96, a psychotherapist. He spoke to Haverford magazine about the tours, his efforts to cure “plant blindness,” and more.

What moved you to launch Snakeroot Ecotours?

I was inspired by a trip to Costa Rica in 2010, where I saw how important ecotourism is to the economy there. Instead of logging it all, they’ve set aside vast tracts of land and built an entire economy around showing the world their amazing forests and all the critters and plants that live there. I was living here in southern Appalachia, which is also one of the great forests of the world, and I thought, “We could do that here.” We have incredible biodiversity. It’s a temperate forest, so it doesn’t have quite the richness that tropical forests have, but it’s still awfully special in its own right. And we have similarly charismatic plants and animals.

What are some notable ones?

A lot of people are surprised to learn that there are quite a few orchids growing here in our forests. I’ve documented about 25 or so species that live right in our valley. These temperate orchids are an indicator of just how botanically diverse our forests are. In early springtime, before the trees leaf out, these rich forests erupt in ephemeral wildflowers. So I arrange trips to see those. And if we have a rainy spell in August or into September, we’ll have the same thing, but with mushrooms. This incredible diversity of mushrooms pops up from the forest floor seemingly overnight. With animals, we have the standard East Coast wildlife, but we also have many, many species of salamander. Our company logo has a red eft on it, which is an adolescent Eastern red-spotted newt—a type you are likely to see on a summer stroll through the forest, especially if it’s been raining. Then there are hellbenders, which live in the cold rivers in the mountains. They’re one of the largest salamanders in North America and can grow up to about 2 feet. They look like little monsters.

‘‘

THE MORE PEOPLE CAN SEE AND APPRECIATE THESE FORESTS, THE MORE LIKELY THEY’LL BE TO PROTECT THEM.

’’

You organize entire trips to view local fireflies. What is special about them?

This happens to be an epicenter of biodiversity for East Coast fireflies. The most famous are synchronous fireflies, which is a rare species that synchronizes their flashing patterns, and there’s also a species called the blue ghost firefly. They are very different from any other species because they don’t actually flash or blink, they stay lit. They hover about a foot or two off the ground, and when there are large populations it’s like you’re standing in a sea of bioluminescence.

Blue ghosts have a relatively short display period of about three weeks or so during the second half of May, and they live in the forest. The only way to experience them is by going into the forest with no light whatsoever. If you have a flashlight, or if you’re driving with headlights on your car, you would never see anything.

I had been observing them for a long time, but it wasn’t until much later, when I was starting my business, that I did more research and learned what they actually are. The first scientific papers about them were only published about 15 years ago.

You’ve written about the need for people to overcome “plant blindness.” What is it and why do we need to overcome it?

The basic idea is that humans have created this built environment for ourselves that, for the most part,

we’re very comfortable in. But in doing so, we’ve neglected old ways of relating to the ecosystems around us. Back in the old days, plants were either food or medicine, or some of them might have been hazardous— and everybody would know all the different types. But we’ve lost that knowledge. We go around completely blind to the plant diversity around us. We go into the forest and it’s just a green wall. I like opening people’s eyes to botanical diversity because once folks are able to recognize and name different species, it makes their experience in the world so much richer.

Is there anything else you hope people who go on a Snakeroot Ecotour might come away with?

I do think that the more-than-human world has an inherent value beyond what we place on it in economic terms. One thing I hope with my work is that the more people can see and appreciate these forests, the more likely they’ll be to protect them. There’s a quote from marine biologist and nature writer Rachel Carson along those lines: “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.”

For more information visit www. snakerootecotours.com

—Eils Lotozo

Editor’s note: After this interview was conducted, Hurricane Helene devastated parts of North Carolina. With many roads closed, along with the Pisgah National Forest, Galton put his nature tours on hold while working to aid local recovery efforts. He plans to start guiding nature hikes again in the spring.

Eils Lotozo is a freelance writer whose work focuses on food, farms, gardens, sustainability, and the environment.

Robert Ocampo ’04 has been on some of the most incredible adventures in the world, set records, and even braved Mount Everest. But for him, exploring the great outdoors is about testing his inner limits. BY JASON NARK

If Haverford offered courses in adventure, Robert Ocampo ’04 would have his doctorate, with a minor in thrill-seeking. After all, it’s not every alum who summits Mount Everest.

Ocampo, who majored in biology and psychology at Haverford with the goal of becoming an astronaut, has spent the last two decades racking up a laundry list of accomplishments in the great outdoors, including traveling the world to ascend mountains far higher than the tip of Founders Hall’s cupola.

Most of Ocampo’s journeys have been upward, into elevations where mountains meet clouds and the slightest mistakes can be perilous. He’s summited 1,200 peaks since graduation, including Everest, infamous for its “death zone.” He aims to conquer the tallest peaks on all seven continents and, after ticking off Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania last summer, only Puncak Jaya, also known as Carstensz Pyramid, in New Guinea and Russia’s Mount Elbrus remain.

Ocampo poses in front of the Matterhorn during the first of his two tries to solo summit the peak . “If I could only climb in one place going forward,” he says, “the Alps would be it.”

The Climb