Winding Roads

Fords Triumphant

How Ron Jenkins ’76 found a calling in prison Creative Sparks A truly inspirational artistic collaboration

Winding Roads

Fords Triumphant

How Ron Jenkins ’76 found a calling in prison Creative Sparks A truly inspirational artistic collaboration

How one alum’s journey with Parkinson’s disease is reshaping research in Haverford’s blossoming neuroscience program PLUS: SCENES FROM COMMENCEMENT AND ALUMNI WEEKEND

Editorial Director

Dominic Mercier

Editor

Brian Howard

Class News Editor

Mara Miller Johnson ’10

Copy Editor

Colleen Heavens

Photographic Director

Patrick Montero

Graphic Design

Anne Bigler

Vice President for Marketing and Communications

Melissa Shaffmaster

Associate Vice President for College Communications

Chris Mills ’82

Vice President for Institutional Advancement

Kim Spang

Contributing Writers

Charles Curtis ’04

Debbie Goldberg

Ron Jenkins ’76

Curran McCauley

Hillary O’Connor

Patrick Rapa

David Silverberg

Anne Stein

Contributing Photographers

Holden Blanco ’17

Dan Z. Johnson

Paola Nogueras

Mac Sanders ’24

Haverford magazine is published three times a year by Marketing and Communications, Haverford College, 379 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA 19041, 610-896-1000, hc-editor@ haverford.edu

©2025 Haverford College

Advancement Services

Haverford College 370 Lancaster Avenue Haverford, PA 19041 or devrec@haverford.edu

30 Tell Us More

Leighton Rice ’06: The Apples of His Eye

By Hillary O’Connor

32 Building a New Brain Trust

How one alum’s journey with Parkinson’s disease is fueling ethical inquiry in Haverford’s blossoming neuroscience program. By Dominic Mercier

Plus: Navigating Uncertain Terrain

What changes in the federal funding landscape mean for STEM research at Haverford. By Chris Mills ’82

40 The Art of Collaboration

This fall, thanks to a grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, a thriving Haverford partnership will put neurodivergent artists in the national spotlight. By Anne Stein

Come to Haverford, and you’ll find yourself surrounded by curious, smart people who are dedicated to and love learning. You’ll also find a shared interest in making Haverford, and the world, a better place.

The pursuit of such worthy goals inevitably brings disagreement or even conflict. The past few years have been particularly fraught for those of us in higher education. Even when we have shared values, the journey of discovery brings the potential for disagreement at every step.

But as I see it, the fact of disagreement isn’t the problem; the question is, what do we do with it? You could say that at Haverford, disagreement is a feature, not a bug—all toward improving how we offer an incomparable liberal arts education in a living, learning, teaching, and working community.

Disagreement is often uncomfortable, particularly before it reaches a productive outcome that dialogue across difference ideally yields. Unfortunately, I see our society growing less accustomed to sitting with and engaging ourselves in this kind of discomfort, partly because we live at a time when vehement disagreement, lack of engagement across those disagreements, and a relative paucity of constructive outcomes are often rewarded. Waging our disagreements via social media, while theoretically an open venue for engaging in queries, listening, and conversation, often inflames rather than settles.

All this can make it difficult to disagree with people, let alone use disagreement as a productive and constructive way forward. And move forward we must.

In uncertain times, I have found that one’s foundational principles provide a dependable resource for navigating necessary change, particularly when that change is accompanied by the friction of disagreement.

Such guidance by principle, for me, is tap-rooted in my work as a molecular biologist. Natural laws create the foundation for how atoms and molecules interact to build and regulate cells. Relying on well-known physical principles governed my laboratory experiments, even as I used those experiments to discover previously unknown ways that cells work. But this process of discovery necessarily gave rise to disagreements about approach, interpretation, and conclusion. My fellow researchers and I never could have worked our way through those without first accepting—no, embracing—the very existence of differences among us as the work progressed. Such a mindset inclined us all toward learning, discovery, helping one another to be better scientists, and promoting constant progress.

Here at Haverford, we are fortunate to be able to rely on the longstanding strength of our mission and values, particularly at times like the present, when pressures across higher education demand a good deal of smart navigation and resourceful

planning. Such values inform distinctly Haverfordian principles that are key to our success, and chief among them is the principle of respect for and expectation of each member’s contributions to this community. We saw the fruits of collaboration in the creation of Better Learning, Broader Impact: Haverford 2030, whose recent outcomes include a new curricular program in entrepreneurship, the curricular and programmatic launch of the Michael B. Kim Institute for Ethical Inquiry and Leadership, expansion of paid summer research experiences once during every student’s four years, and implementing a campus-wide compensation study to ensure the market competitiveness of faculty and staff salaries.

Shared principles enable the work of community while also shaping queries— of ourselves, and others—that can help us move through and beyond disagreement. (Make no mistake, each of these examples saw plenty of disagreement during the shaping of the final form.)

Additionally, four collaborative community endeavors are both testing and showcasing the power of foundational principles to inspire and guide the work, while providing venues for engaging across difference:

No other college or university offers a learning and living experience like Haverford, where students have unparalleled opportunities to shape their own path and collaborate in community. This spring, we developed a draft set of core values that define the type of campus culture that we collectively aspire to uphold.

“

In uncertain times, I have found that one’s foundational principles provide a dependable resource for navigating necessary change.

”I don’t need to tell you how and why our student-administered Honor Code is central to the Haverford experience. And, as is the case with all our institutional policies, the Honor Code exists within, and must comply with, federal and state legal frameworks. In order to address some misalignments between the Code and the current legal landscape, a revised Honor Code, drafted in consultation with the Honor Council cochairs and Students’ Council co-presidents, is temporarily in effect. A working group of students is spending the summer drafting a Code for consideration at a Special Plenary this fall in order to address these misalignments while maintaining the integrity, purpose, and spirit of the Code.

After several months of extensive engagement with on- and off-campus community members, and informed by expert literature and best practices in higher education, the Ad Hoc Committee on Freedom of Expression, Learning, and Community has issued its final report. The report details areas of concern, strength, and opportunity that sit at the intersection of expressive freedom and fostering a campus community in which all members can thrive. I thank the committee for its indepth and thoughtful work and will lead the implementation of many of the recommendations contained within the report in order to advance Haverford’s educational mission, now and well into the future.

We have developed an interim revision to the Policy on Expressive Freedom and Responsibility to better articulate the College’s commitments and each community member’s rights and responsibilities. We are in the process of reviewing feedback and will discuss with campus stakeholders and finalize changes to the interim policy this fall.

Ambitious, worthy, essential undertakings all, each has the potential to unite and empower individuals and our community. As you might expect, the efforts that have brought each working group to the point of deliverables has relied on our core principles to define and spotlight goals, while also giving those in the groups—and you, via our feedback process—a basis for crafting argument in favor or against specifics along the way. The experience reminds me of my work back in the labs of Cornell and Harvard, where I learned to acknowledge, then embrace, then work with difference, all in service of a stronger outcome.

And, like the healthy and productive disagreement that has marked these recent engagements, I fully expect that many of us—you, me, the greater Haverford community on campus and beyond—will find discernment through dialogue that, even with disagreement, advances our beloved Haverford.

I will welcome that dialogue.

With gratitude,

I very much enjoyed Eils Lotozo’s article in the latest Haverford magazine about alums in historic preservation (“Building on the Past,” Winter 2025), but was a little startled to see that none of those profiled were architects. Can it be that I am the only one?

While I love preservation advocacy and have served on my share of design review boards over the years, I have to point out the difference between advocacy and action. It takes a dedicated team of architects, engineers, and contractors, as well as advocates, to move a project from concept to reality.

After graduating in 1973, I spent three years teaching in a Friends elementary school while figuring out what I might want to do with the rest of my life. I came to believe that architecture offered a path to indulge many of my interests in a career where I could even make a living. The Haverford career center was

Ask a question or offer a comment on one of our stories. Tell us about what you like in the magazine, or what you take issue with. If your letter is selected for publication, we’ll send you a spiffy Haverford College coffee mug.

Email: hc-editor@haverford.edu Or send letters to: Haverford magazine

Marketing & Communications

Haverford College

370 Lancaster Ave.

Haverford, PA 19041

able to connect me with alumni who had followed such a path, and I soon moved to Salt Lake City to obtain a master’s in architecture.

I retired in 2020 after a career in which I worked on hundreds of existing buildings and exactly two new buildings. One of the pleasurable side effects of working on historic buildings is that they have already established their place in local culture and society, and their restoration, preservation, or adaptive reuse is a statement of their value. Very few of the buildings that I have touched over the years have been demolished.

What I learned along the way was that my Haverford education was much more important than my architectural degree, something I never fail to tell prospective students. So much of architecture has changed in the last 50 years, but the process has always involved the same skills of problem identification, analysis, communication, and consensus that I first learned at Haverford.

Architecture is a communal art form, and historic buildings are a community resource. All of those that you profiled in your article are participating in a continuing collaboration that eases the transition of communities from the past to the future. They all play different but

essential roles in this collaboration. But don’t forget the architects!

—Jim McElwain ’73

Thanks for Eils Lotozo’s excellent article “Building on the Past.” I am Aaron Wunsch’s father. I think of him every moment, it seems. I know he would have taken great pleasure from your article and your treatment of him and his students. —A. David Wunsch

I was particularly excited to see that you mentioned my “grandplant’s” application to Haverford for the class of ’26 in Jill Waldbieser’s story “A Growing Tradition” (Winter 2025). I would like to clear up a small misunderstanding in your article, though. Roger’s application to Haverford was never actually denied. We never received a response from [Vice President of Admission] Jess Lord, so we presumed the application was lost in the mail during COVID. I had been in contact with [Arboretum Program Coordinator] Jennie Kelly back in 2022 about Roger, so she likely misremembered the outcome of his application.

Once again, thanks so much for reviewing the topic, and I’ll be sure to let Roger know that he made it into the magazine again.

—David Schutzman ’74, P’06

Commencement was a picture-perfect sendoff for the 394 members of the Class of 2025. FOR

At Commencement, 394 Fords crossed the stage and into the next chapter of their lives. BY

DOMINIC MERCIER

On Saturday, May 17, families, friends, faculty, and staff gathered in Alumni Field House to celebrate Commencement with Haverford’s Class of 2025. Under skies that shifted from overcast to dazzling, the College honored the accomplishments and resilient spirit of 394 Fords who began their journey amid a global pandemic and emerged from their academic experiences transformed.

The weekend’s festivities were not limited to Saturday. In the days leading to Commencement, the College honored the identities that shaped the Class of 2025 with

celebrations for Chesick Scholars, international students and their families, students of color, and the College’s LGBTQIA+ community. The cheerful—and sometimes emotional—gatherings reflected the many ways the class supported one another with care and intention.

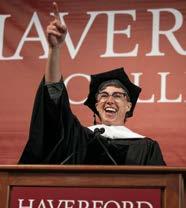

In delivering his remarks for the Class of 2025, Yehyun Song ’25 proudly declared his peers “The Class of Doers.” Recounting their journey from COVID-era uncertainty to embracing their roles as tomorrow’s leaders, Song praised classmates who reinvigorated Haverford’s campus life post-pandemic, creating new opportunities and

filling the campus with “life, laughter, and love.”

“If there’s one thing the Class of 2025 knows how to do, it is to live and lead in uncertainty. In fact, we’ve spent the last four years doing exactly that,” he said. “We didn’t wait for a perfect moment to get involved. We did what we could, where we were, with what we had.”

Student-selected speaker and Laurie Ann Levin Professor of Comparative Literature Maud McInerney drew on poetry to mark the moment, turning to the works of Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich to illustrate how language and imagination could illuminate the graduates’ path forward.

“Poetry is not a luxury,” McInerney said, quoting Lorde. “It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.” She urged grads to stay attuned to beauty, justice, and truth: “Keep reading. Keep writing. Keep thinking.”

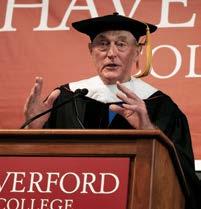

The College also continued its tradition of awarding honorary doctorates to individuals whose lives and work exemplify the College’s mission. This year, two Haverfordians were honored: Katrina Spade ’99 and legendary track and cross country coach Tom Donnelly.

Spade, the founder and CEO of Seattle-based Recompose, shared her journey from anthropology major to advocate and leader for compassionate and sustainable death care. She urged graduates to embrace uncertainty, lead with curiosity, and “fight like hell for a livable planet.” Donnelly, who retired last year after an astounding 49 seasons, offered graduates one last bit of coaching: “You’re almost at the finish line—but it’s also the starting line of the next race.”

As Dean of the College and Vice President John McKnight called their names, each graduate strode across the stage to receive their congratulatory handshake from President Wendy Raymond and revel in cheers. With tassels turned and futures unfolding, the Class of 2025 stepped into the sunlight, ready to carry their Haverford experiences into the wider world.

Capping it off: The Class of 2025 makes its way to Alumni Fieldhouse (1); one Ford is ready to say goodbye (2); Yehyun Song ’25 addresses “The Class of Doers” (3); legendary track coach Tom Donnelly receives his honorary doctorate (4); marking the moment, Haverford style (5); one excited Ford celebrates his accomplishments (6); a family grabs a quick selfie outside the Gardner Integrated Athletic Center (7); President Wendy Raymond congratulates a graduate (8); Katrina Spade ’96 encourages the class to “fight like hell for a livable planet” (9); three Fords make last-minute adjustments before the ceremony begins (10).

One Person’s Trash In recognition of Earth Day, Administrative Assistant Jake Gaspari curated the pop-up exhibition Rebirth along the College’s Nature Trail. The featured artworks, which included pieces created by students, faculty, neighbors from nearby Narberth, Pa., and Gaspari himself, were all made from recycled or repurposed materials. Though it was only on view for two and a half hours, the exhibition provided a delightful surprise for hikers and runners and has inspired Gaspari to consider more ways to bring art to the College’s scenic spaces.

Game On for Giving The fourth annual Gameday Fords Giving Challenge shattered records, raising nearly $440,000 from 1,209 donors—more than double the goal. Support came from alumni, parents, students, and even incoming members of the Class of 2029. All 23 varsity teams benefited, with fencing, field hockey, and cricket leading the charge. Matching gifts amplified the impact, helping to fund the scholar-athlete experience across campus.

March Through History For the second year in a row, Haverford students, faculty, and staff journeyed through the American South during spring break as part of the College’s annual civil rights trip. The journey led them through many key sites of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, from Charleston, S.C.’s slave auction sites and plantations, to the historic streets of Montgomery, Ala. The weeklong experience, organized by the College’s Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Access division, provided Haverford’s travelers with a deeper understanding of the ongoing fight for racial justice.

BIG BANG ... AND A BIG HONOR

Professor Emeritus Bruce Partridge, a pioneer in observational cosmology, was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Known for his research on the cosmic microwave background—the heat that remained after the Big Bang created our universe —and his contributions to major international projects like the Planck satellite, Partridge has also inspired generations of students through his decades of teaching and mentorship. His election honors both his scientific achievements and his continued impact on the Haverford community.

April Fools With a Scientific Twist Pranksters at Koshland Integrated Natural Sciences Center (KINSC) struck again, transforming it into a whimsical wonderland this April Fools’ Day. Students from the biology, chemistry, math, and physics and astronomy departments decked the halls with handmade decorations: a Magic School Bus, Super Mario’s Mushroom Kingdom, a “Mathopoly” board, and a Magic: The Gathering tribute featuring professors and their unique powers.

Crankie Through a performance organized by Visiting Assistant Professor of East Asian Languages and Cultures Honglan Huang, interdisciplinary artist Maisie O’Brien demonstrated for the College the art of illuminated crankie theater. The illuminated scrolling panorama is a method of storytelling rooted in ancient Indian and Indonesian traditions, where scrolls were used to tell stories drawn from religious epics. O’Brien’s performance combined shadow puppetry and song, proving that traditional techniques can play a powerful role in contemporary storytelling.

Delaney Kenney ’25, a neuroscience major with minors in psychology and museum studies, is Haverford’s first FAO Schwarz Fellow. This prestigious two-year fellowship at Boston’s Museum of Science will have her designing youth programs and in-gallery experiences to make STEM more accessible. Inspired by her own journey—which includes a diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and a transformative internship in Colorado—Kenney looks to turn science communication into an impactful tool.

Traditional Chinese Dance In April, the Bi-Co Chinese dance group Mei filled Marshall Auditorium for its spring showcase. With the theme “A Wordless Poem,” the performances found inspiration in Chinese poetry, murals, and music—transcending linguistic barriers to highlight the ephemeral beauty of spring. A week later, Mei cheered on five of its dancers as they traveled to Los Angeles to compete in the prestigious World Culture Dance Competition.

Conclave Confidential As the world waited for white smoke to billow from the Sistine Chapel’s chimney, Associate Professor of Religion Molly Farneth, who teaches a course on the politics of ritual, spoke with the New York Times about the importance of the papal conclave that eventually elected Pope Leo XIV. Farneth discussed the metaphor of handing the keys of the Catholic Church to a new leader and whether or not Pope Francis’ successor, through the moral authority granted to him, could shrink or expand the church’s community.

Fords were encouraged to take a moment to connect with the sounds around them when renowned New Zealand-born contemporary composer and sound artist Annea Lockwood visited campus in March. Lockwood, who burst onto the scene in 1968 with a performance that included lighting a piano on fire and recording it, led Fords through an immersive exploration of deep listening and ecological awareness as part of the Bi-Co Environmental Studies program’s Re(Growing) a Living Culture series.

Curator Rainey Tisdale ’94 has been preserving verse and storing it in jars—because nourishment comes in many forms.

When she was a Haverford student, Rainey Tisdale ’94 found comfort and solace in the thousands of trees on campus. As her family life back in North Carolina unraveled “like a southern gothic novel,” the arboretum became her refuge, a place where she could set her roots in the face of uncertainty.

“When I visited Haverford on my college tour, I could feel how special it would be to go to school in the middle of an arboretum. I felt that viscerally,” Tisdale recalls. “It’s a big part of why this place felt so right to me.”

In April, Tisdale returned to campus to install Provisions, an exhibition in Lutnick Library that channeled her experiences into a tender offering: 81 jars of what she calls “poem preserves.” Each is filled with buckeyes, the seeds of certain Aesculus trees, that Tisdale collects after they fall. She then

dries them and inscribes each with lines of poetry in tiny, meticulous script. Each jar is marked with a tag indicating the poet and poem contained within and includes at least one buckeye Tisdale collected from Haverford’s 18 Aesculus trees. The exhibition was on view through early June.

The assemblage of jars, which Tisdale finds at thrift stores and upcycles, resembles an oldfashioned larder. That’s precisely the point, she says. “I’m drawing on the pantry as an important metaphor. We need to preserve and put by for the long winter our poems, just as much as we need to preserve our peaches, okra, and tomatoes, because poems also nourish us in a way we need to be nourished.”

Tisdale, a museum curator in her daily life, began writing poetry on buckeyes more than a decade ago. She says she found inspiration in the buckeyes’ natural form, the tactile process of

painstaking handwriting, and her family history: Her father was a prolific poet, and she grew up surrounded by his verse. The transcription process, slow and meditative, is almost a form of devotion that allows Tisdale to absorb each poem word by word, she says.

“Organized religion never took for me,” she says. “I explored a few of them, the major ones, and they just didn’t inspire me. But somewhere along the way, much later in life, I realized creativity has always been my religion and poetry is the sacred text.”

The notion for the exhibition grew from Tisdale’s long friendship and shared love of poetry with Haverford staff member and poet Charlotte Boulay. Together, they issued a call to Haverford’s community seeking original poems or suggestions for published works that community members found particularly meaningful. The collection they’ve curated includes works by established poets such as Tracy K. Smith and Elizabeth Bishop alongside contributions from alums and students. Boulay’s poem “Foxes on the Trampoline,” the source for one of the first jars Tisdale ever created, was also featured.

“The vernacular of Rainey’s artistic practice spoke to me from the beginning,” says Boulay. “I’ve lived with the jar of my poem that she made for me some years ago for a while now, after she gave it to me. My first book came out 11 years ago this spring, and this collaboration has helped my writing by convincing me that I should keep at it, and that my poems might still have something to say.”

While some of Tisdale’s jars have appeared in smaller-scale installations—most notably the Fulbright Scholar Program’s offices in Sofia, Bulgaria, last year—Provisions was her largest display so far. It arrived on campus at the perfect time, as April is National Poetry Month. During the opening reception, which Tisdale describes as “very gratifying,” community members read poems and walked away with their own buckeyes inscribed with the words: “You are poetry.”

“We’re living in a time of great uncertainty. We spend a great deal of that time at work,” says Boulay. “It means a lot to me that Rainey and I proposed a small way of speaking to each other and to the community through this exhibit that might remind people that both poetry and the natural world can be a respite, and perhaps a guide.” —DM

WHO: Tea aficionados and first-year students Esme Dorsey ’28 and Ian Trask ’28 felt that Haverford could use a recurring klatch for their tealoving peers, from novices to seasoned sippers, to explore the vast world of steeped beverages together. The result is the Tea Tasting Club, one of the College’s newest student-run organizations. Trask, who has been drinking tea since his mother began bringing back unfamiliar varieties from her global travels, says he has long dreamed of starting a tea club. Dorsey, who discovered a love of tea during the pandemic, figured the club would be a good way to meet new people and taste new flavors.

WHAT: The club meets about every two weeks during the academic year to discuss and sample the ethically sourced teas it acquires online or from Ardmore’s The Head Nut. Typically, about 20 Fords turn out to filleth their cups with brews of three different flavors, from classics like Earl Grey and Irish Breakfast to more unique offerings, like the blue-hued Indigo Punch. The club’s future plans include exploring iced varieties in warmer months and educating about the art of tea making.

WHERE: Most events are held in room 102 of the Visual Culture, Arts, and Media building thanks to its fireplace and generally cozy atmosphere. The club also uses other campus locations, like the Skate House, when available.

WHY: In addition to introducing Fords to different teas, the club seeks to foster a greater sense of community on campus. Trask’s and Dorsey’s focus extends beyond the kettle to raising awareness of tea’s colonial history and the social impacts surrounding its production. “We do our research when we buy our teas,” says Trask, “and talk about how colonialism, child labor, and bad labor practices are continuing problems in many areas where tea is grown.” —DM

Follow the club on Instagram: Haverford kcc

Taught by:

Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor Ezgi Guner

What Guner says about her course: This advanced seminar is an anthropological exploration of empire, both as an analytical category and a historical phenomenon. In the first half of the course, we focus on the historical entanglements between the discipline of anthropology and empire. This exploration ranges from early modern travel writing to the colonial practices of collecting, classifying, and exhibiting objects as well as humans and human remains, for instance, in world’s fairs or anatomy museums.

The second half of the course examines the anthropological critiques of this legacy. Each week, we engage with ethnographies of empire from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, the

Middle East, and North America. Through this global examination, students deepen both their regional knowledge and conceptual understanding of race, settler colonialism, empire, museums, and restitution.

Guner on why she wanted to teach this class: This course emerged from my own research interest in the intertwined histories of empire in the Middle East and Africa and their ongoing legacies in the present.

I also have an interest in the history of the discipline, which is inseparable from the formation and consolidation of ideas around race and racial difference, as well as from imperial conquest, chattel slavery, and colonial domination. In merging these two interests, I developed “Anthropology of Empire” to share my passion for historicizing and critiquing systems of oppression with students. By asking students to develop their own final projects, this course also allows space for everyone to pursue their own intellectual passions. In turn, I learn a great deal from students as well!

Guner on what makes this class unique: This course provides a unique and immersive learning experience that is rooted in hands-on experience. We start by watching a sci-fi video essay to explore the connections between science and empire. Next, we read a 17th-century Renaissance utopia to further examine the relationship between para-ethnographies and fiction as a non-scientific genre. In an in-class exercise, students engage in archival research and visual analysis by studying the Quaker Special Collection at Lutnick Library. Finally, students write a critical museum review as their midterm after a field trip to a Philadelphia museum, such as the Mütter Museum or the Africa Galleries at the Penn Museum. These are all examples of experiential learning, where students learn by engaging directly with various literary, artistic, and ethnographic materials and practices and actively co-create meaning.

Cool Classes is a recurring series on the Haverblog. For more, go to hav.to/coolclasses.

Nearly 400 students will join Haverford this fall as members of the Class of 2029 , representing 36 states , Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and 21 countries . About 15 percent are first-generation college students, and 15 percent are coming from outside the U.S. including, for the first time, students from Afghanistan, Ecuador, and Uzbekistan. The class also includes more than 30 students with family ties to Haverford.

Spotlighting the holdings of Quaker and Special Collections

An early atlas of the sky reminds us that humans have always sought to understand the stars.

Well before the dawn of powerful telescopes and startracking apps, those with an eye on the heavens turned to books like La Sfera del Mondo to comprehend them. Published in 1540 by Italian astronomer, philosopher, and humanist Alessandro Piccolomini, the elegant volume was envisioned as a practical guide for the Renaissance’s cosmically curious.

As one of the first printed star atlases, La Sfera del Mondo (which translates to The Sphere of the World and was published with a companion work, Delle Stelle Fisse ) diverges from earlier works by labeling observable stars with letters instead of filling its pages with mythical creatures, marking a new era for astronomy rooted in empirical observation. Eschewing elaborate illustrations, La Sfera del Mondo’s relatively plain pages feature woodcut renditions of individual stars and constellations akin to our modern-day star charts.

Those simple diagrams and Piccolomini’s alphabetic labeling of stars allowed readers to identify different stars and constellations quickly. Accessibility also made La Sfera del Mondo incredibly popular, with 12 editions printed between 1540 and 1595. The copy in Haverford’s collection was printed in 1566.

The book, part of a larger effort to make scientific knowledge more accessible, highlights the convergence of art, science, and education characteristic of the humanist movement. In fact, Piccolomini’s choice to produce it in Italian instead of Latin tells us who his intended audience was: not scholars or the church, but rather the everyday residents of a world bursting with new knowledge. It’s not hard to imagine a 16th-century reader, book in hand, gazing into the night sky from Siena’s Piazza del Campo while matching the heavenly lights above to La Sfera del Mondo’s diagrams.

In many ways, the book remains relevant today, not just for the knowledge it contains, but as a record of human curiosity. For instance, Professor of Physics and Astronomy Karen Masters’ 2024 book The Astronomer’s Library: The Books that Unlocked the Mysteries of the Universe features Piccolomini’s tome prominently. For Fords studying the universe today, whether detecting gravitational waves or logging time on Strawbridge Observatory’s 12- and 16-inch telescopes, that spirit of curiosity persists. While the universe might feel even more expansive and mystifying than it did in Piccolomini’s time, the quest to make sense of the stars and understand our place in the universe remains unchanged nearly 500 years later. —DM

2025 PHOTO CONTEST

Ashrith Kandula ’26 was late to the eastern screech-owl party. “This particular owl became a local celebrity this spring,” he tells Haverford , noting that birders first started reporting its presence on campus in late February. Once Kandula, co-leader of the Haverford Ornithological Club, caught wind of it in March, he spent several futile evenings lying in wait. Then, after spring break, a friend texted him. The owl was in its roosting hole in a tree on the Nature Trail—and the quest for the perfect snap was afoot. Kandula, who’s been published in Birding magazine and a finalist in nature photography competitions, knew just what to do “to achieve the eye-level effect— without being 15 feet tall!” He grabbed a long lens, set up at a distance, and then waited for the snoozing bird to open its eyes. About an hour later—voilà!

Kandula’s was one of 47 entries to the fourth-annual Arboretum photo contest, which is open to students, staff, faculty, and community members—“essentially anyone who has possibly taken a photo of the campus,” says Arboretum Program Coordinator Jennie Kelly. “Traditionally, the winner has been a stunning fall color shot,” she adds. “We had more wildlife photos than ever before.”

To that end, the second- and third-place photos, both by Sam Cohen ’26, feature squirrels—one being eaten by a red-tailed hawk and another eating a nut.

—Brian Howard

Since she arrived at Haverford College in 2009, Helen White has made her mark as a teacher, a researcher, and, in the role of associate provost for curricular development and research, an academic leader.

On July 1, she will step into a new role—provost—overseeing the entirety of the College’s academic enterprise, ranging from faculty, curriculum, and research, to Tri-Co Philly and study abroad programs. She will also be charged with overseeing implementation of Better Learning, Broader Impact: Haverford 2030, the strategic plan she helped develop.

As a scientist, White—who earned her master’s in chemistry from the University of Sussex in England and Ph.D. in chemical oceanography from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution—has received funding for research that includes the widespread impact of oil spills and environmental contamination.

What excites you most about stepping into the role of provost at this moment in the College’s history, and what experiences as a scholar do you expect to shape your leadership?

Having been part of the team that shaped Haverford 2030, I’m especially looking forward to helping bring that plan to life on campus, and being ambitious about what’s possible in the years ahead.

My work as an oceanographer has shown me the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration across scientific, social, and ethical perspectives. My research into marine pollution, specifically oil spills, has taught me to value the many forms of expertise that exist both within academia and in broader communities. As provost, I hope to maintain this openness, supporting academic work that is both rigorous and welcoming of different ideas and approaches.

You played a key role in developing the strategic plan. Which aspects are you most excited to help bring to life?

Haverford 2030 offers a vision that builds on the strengths of the academic program while inviting new ways of thinking and working. I’m most excited by the parts of the plan that invest in faculty scholarship, expand interdisciplinary opportunities, and strengthen the connec-

tions between what students learn and how they apply that learning beyond the classroom.

Do you think a liberal arts education can remain relevant at a time of significant challenges to higher ed, including high costs, campus unrest, and threats of the loss of federal funding?

In a time of uncertainty, the ability to think critically and creatively, communicate clearly, and engage across perspectives is more important than ever. A Haverford education helps students connect what they learn to how they want to live, with a sense of responsibility to the world around them. That kind of education feels not only meaningful, but essential.

Institutions are facing serious pressures, but I believe this is a moment to celebrate our strengths. At Haverford, collaboration between faculty and students through both research and teaching is at the heart of what we do. It’s what makes the College distinctive. The challenge is to advance that meaningful work with care and purpose, even as the landscape around us shifts.

How has your scientific background informed the way you think about leadership and the importance of supporting research?

My scientific background has taught me to stay with questions, even when answers are slow to come, and to embrace the unexpected. It’s shown me that understanding comes both from close examination and from stepping back to see the big picture. Working in disaster response, specifically during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, taught me the importance of building relationships and shared responsibility. That experience informs how I think about collaboration, which I aim to carry forward as provost.

At a time when fundamental research faces real pressures, it’s vital that faculty are supported in all aspects of their scholarly work. At Haverford, research is not just preparation for a career—it’s a way of contributing to the world. That shared purpose is central to our community, and I’m committed to sustaining it.

—Debbie Goldberg

With a remarkable finish at the national championship, and a member named the nation’s top college lawyer, Haverford’s student-run team takes its place among the elite.

There’s no debate here—Haverford’s Mock Trial team has a lot to celebrate after its stellar showing at the American Mock Trial Association’s National Championship Tournament in April. Not only did the team place fifth in its division, securing its spot as one of the top 25 teams in the U.S., but co-president Bella Salathé ’25 emerged as the nation’s top collegiate lawyer.

What’s most impressive, though, is that Haverford’s team remains an entirely student-run affair. Among the 700 teams that compete in the association’s events, some are backed by law schools and paid coaches. Haverford’s team receives guidance only from alumni, including Ceci Cohen ’24, Jordan

BY DOMINIC MERCIER

McGuffee ’18, and Isabella Canelo Gordon ’18, who attended nationals with the team.

“We couldn’t have done it without them,” says Salathé’s fellow co-president, Isabella Otterbein ’26.

This was the third appearance at nationals for the team, which boasts about 20 members, half of whom are aspiring attorneys. Its last run at the title was in 2023. Since then, the team has continued to build on its reputation for creativity and resourcefulness, including its unorthodox strategy of organizing its case around a single strong fact it discovers.

“We spend a lot of time developing a theory that makes us feel confident and will put the rest of our team in a position to score well,” says Otterbein, a political science major. “But we do go a little rogue. That makes it fun and forces the other team to adapt to our one-fact case.”

This unconventional style paid dividends for the team this year as it navigated the pressure and complexities of the championship. In regional competitions, collegiate attorneys and witnesses will typically work on one case from August through March. For nationals, however, the team was given just three weeks to prepare. At the championship, which was held in Cleveland this year, the team took on a wrongful death suit in which a man was killed after his tie was caught in a bowling alley’s machinery.

In addition to its podium finish, Haverford was the runner-up for the Spirit of the American Mock Trial Association (SPAMTA) award, which is presented to teams that exemplify kindness, respect, and civility. The award is something Otterbein and Salathé always strive for, and that approach has resulted in friendships with other teams—American University and University of Maryland, Baltimore County, in particular—that

Bruce Landon Davidson: Humanistic Documentarian, Photographs from 1958-1992

Through Sept. 2 in the Jane Lutnick Fine Arts Center, Atrium Gallery

From the teenage gangs of New York to the marches on the streets of Selma, Ala., Bruce Davidson’s striking black-and-white photographs provide an empathetic yet unflinching visual record of mid-20th-century America. Bruce Landon Davidson: Humanistic Documentarian, Photographs from 1958–1992, on view this summer in the Jane Lutnick Fine Arts Center’s Atrium Gallery, includes a survey of 36 compelling prints the photographer produced throughout his more than 70-year career.

Davidson, who joined the influential collective Magnum Photos in 1958 and remains a contributing member at age 91, is widely regarded as one of the most important humanist photographers of his generation. Much of his work engages with social justice and exhibits the high level of trust he establishes with his subjects as he captured their lives over the span of months and years. The exhibition includes selections from several of Davidson’s most notable series, including Times of Change, his extensive chronicle of the Civil Rights Movement and the Freedom Riders’ efforts in the early 1960s.

To place Davidson’s work in a broader context, the exhibition also features work by Davidson’s

contemporaries and stylistic influences, including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, and Diane Arbus. Together, the photographs prompt viewers to reflect on the medium’s ability to shape public consciousness and spur social change.

extend well beyond the courtroom. The bonds the team has formed, they say, set them apart from the bigger and better-resourced teams.

“We make that part of our mission and team expectations,” Otterbein says. “We all agree that regardless of how we feel about the judging, we’re always going to represent Haverford’s values of trust, concern, and respect.”

Salathé’s honor, the result of voting by the competition’s judges, is somewhat unexpected considering the rocky start to her mock trial career. Growing up in Japan, she didn’t have access to a team in high school. Seeing herself as an “argumentative person,” she joined Haverford’s team, but struggled during her first year.

“It was so weird because my first year at Haverford was mostly on Zoom, and I had no idea what was going on,” Salathé, a computer science major, recalls. “I think I cried at every single trial. I just felt constantly humiliated.”

Determined to improve, Salathé reached out to the team’s alumni supporters and continued to grow. This summer, before beginning computer science graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania, she was slated to be the first Ford to represent the College at Trial by Combat, a one-onone mock trial competition hosted by Drexel University and UCLA, that pits the nation’s 16 best collegiate attorneys against one another.

After completing her program at Penn, Salathé plans to pursue law school and eventually work in law surrounding the tech sector.

“At first, mock trial made me not want to be a lawyer, but then it kind of made me want to become a lawyer,” she says with a laugh. “But it’s also taught me how to speak about complicated tech in ways anyone can understand. It’s also helped me with job interviews. I am really grateful for what the team has done for me.”

Participants in the inaugural Bi-Co Exploring Transfer Together (ETT) program peek at what’s growing at the Haverfarm in early June. The weeklong summer program invites students enrolled in community colleges to envision themselves in a liberal arts environment and aims to demystify the application and transition process. Through the theme “Global Environmental Challenges: Strategic Communication, Collaboration, and Solutions,” students engaged in collaborative learning and residential life on Haverford and Bryn Mawr’s campuses. Visits like this one highlight the liberal arts’ interdisciplinary approach to environmental and social issues. ETT is designed to serve as a guide for students as they navigate the transfer process, and create a network of faculty, staff, and peers who will support them throughout their educational journey.

Scholarship support from THE JOSEPH C. AND ANNE N. BIRDSALL SCHOLARSHIP FUND has opened the door for biology major Diego Zuniga ’28 to thrive in the vibrant community and rigorous academics that make Haverford unique.

“ Thank you so much for your donations to all the students who benefit. I myself am very grateful, as I know I would not have the same level of education, same level of community, and same level of opportunity if I went to another school. Not only is Haverford the right school for me, but it was made possible through these generous donations. ”

When data analyst Juliette Rando ’15 isn’t working to uncover the mysteries of the brain, she’s merging art and activism in her band Eraser. BY PATRICK

RAPA

“I think it’s very powerful to be succinct,” says Juliette Rando of her band’s music. “We’re not trying to take up too much space, but we do have something to say.”

By day, Juliette Rando ’15 works in an environmental epidemiology lab at Drexel University, sorting through large data sets related to autism.

By night, she can be found behind a drum kit with Eraser, a fiery Philly band that just released their first record, Hideout, on stalwart Philadelphia independent music label Siltbreeze.

Whether she’s analyzing data or keeping a beat, you could say Rando’s job is to maintain a level head when things get noisy. “It’s nice to make order where there was chaos before,” she says.

Rando, who grew up in the Boston area, was a biology major with a neuroscience minor at Haverford, and went on to get her master’s in public health from the University of Pennsylvania.

At the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute—where she’s pursuing another master’s, this time in data science—she works with a team studying the influence of diet and environment on neurological development. She’s “still doing the science thing,” as she puts it, “but not pure bio-wet-lab-pipetting stuff. More like data analysis.”

“I basically spend a lot of time cleaning and or-

we didn’t live in a society that’s extremely stigmatizing of people with any disability.”

In the four years she’s worked at the Autism Institute, Rando has seen strides made, including new studies that examine ways to improve the lives of people with autism, and efforts to include people with autism on advisory boards to offer feedback and insight. There’s plenty of research to be done, she points out, on subjects like comorbidities, connections to gut health, and more. “Wouldn’t that be a much more respectful and worthwhile use of research funding”—better understanding and improving the lives of people with autism—“rather than preventing them from existing?”

ganizing data, and creating data sets from large, messy databases. And then I’ll run different statistical tests based on what my outcome is and what my predictors are,” she explains. “It’s just very satisfying to do. It’s very relaxing.”

That said, Rando is wary of the ways such data could be misunderstood or misused. “If a study shows, for example, that eating red meat in pregnancy is associated with your child having autism, is there now going to be a panic and people avoiding eating red meat because they don’t want autistic kids? That’s a horrifying eugenics takeaway from the research.”

Simply understanding brain development, she says, “would be a wonderful goal and mission—if

It’s no surprise Rando has some strong, well-enunciated opinions on ethics. For one thing, she went to Haverford. For another, she volunteers with the Human Rights Coalition, which advocates for prisoner rights and an end to mass incarceration. For a third, she’s in Eraser—a brash and bratty dance-punk band that wears its heart on its sleeve.

“I do a lot of community organizing on the side, and it’s always been kind of separate from my music stuff,” says Rando, who has played in several Philly bands, including Corey Flood, which generated a bit of national buzz before splitting up during the pandemic era. “It’s really meaningful to have it coalesce.”

The first song Eraser ever released was on a 2024 compilation called No Occupation: Another Benefit for Mutual Aid in Gaza, and that outspoken vibe continues on Hideout. Led by drywitted singer and synths player Sonam Parikh, muscular empowerment anthems “Simon Says” and “Talk to Me” bring to mind trailblazers from the early ’90s Riot Grrrl era.

The eight-song, 15-minute-long release was recorded in Rando’s mom’s therapy office in Western Massachusetts and released in March 2025. “I think it’s very powerful to be succinct,” says Rando. “We’re not trying to take up too much space, but we do have something to say.”

Jo Vito Ramírez ’13 brings a scientist’s curiosity to a multifaceted arts career.

From children’s theater at the Arden to Shakespeare in Clark Park to roles with some of the city’s most artistically adventurous figures and troupes, including Whit MacLaughlin, Headlong Dance Theater, and FringeArts, among others, actor and artist Jo Vito Ramírez ’13 (they/them) has pushed the boundaries for more than a decade in the Philadelphia theater scene.

In February, Ramírez wrapped up a mainstage run in the title role at Arden Theatre Company’s Peter Pan, and more recently served as assistant director for the company’s children’s production of The Hobbit.

my major to theater to focus on the playful act of creation.”

“I’d never directed on such a large scale, so I asked if I could assist the director, Becky Wright,” says Ramírez, who’d been directed by her once. “I knew I’d learn a lot from her.”

It’s an example of what’s become a recurring theme in their career: constant learning through pushing into new forms of artistic expression. For example, Ramírez is currently focused on painting and music making. “What’s most important to me as an artist is to stay curious and to continue to challenge myself, which often means trying new media,” says Ramírez, speaking from their home art studio in Germantown. “Often, I’ll pick up a new medium and find it has something to teach me about my artistic practice in general.”

Their current project is a 3 feet by 3 feet landscape painting combining an interest in Roman history (Ramírez’s mother and grandmother live in Calabria, Italy) with a portrait of Ramírez wearing the hairshirt of St. John the Baptist (it’s an homage to Renaissance compositions). “I didn’t have any training in painting and I think that’s one of the reasons I enjoy making art so much. In some ways, it can be extremely foreign to me, but feel so close to home.”

A QuestBridge College Prep Scholar from the Bronx, Ramírez attended high school at the borough’s Collegiate Institute for Math and Science, then came to Haverford to study astrophysics and minor in theater. “There was very little in the way of art at my high school,” says Ramírez, who started a drama club there after dabbling in theater in junior high.

At Haverford Ramírez realized that the hard sciences weren’t a strong suit, so they shifted to sociology while taking theater classes at Bryn Mawr. “Junior year I decided I’d much rather write and direct a play than write a sociology thesis, so I shifted

Ramírez was especially inspired by two professors in the Bryn Mawr-Haverford Bi-College Theater Program: Professor Mark Lord, with his rich academic view of theater practice, and Associate Professor Catharine Slusar, who most influenced Ramírez’s artistic practice.

In a Lord course on playwright Samuel Beckett, for example, Ramírez learned that Beckett, a native English speaker, challenged himself by writing in French. It’s a technique adapted by Ramírez, who’s currently playing instruments they’re not familiar with, including harmonica, cello, and the chord organ, and composing music in what they call an earnest, playful, and contemplative style.

“Art can be a practice in pretension—you can try to impress people and make it purely with the audience in mind,” explains Ramírez, “but I feel like I have this one precious life and I ought to continue to play and challenge myself and fail, because that’s the best way to learn.”

Making a life in the arts, Ramírez admits, is challenging. “With the recent [proposed] defunding of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), I’m hyper-aware that it’s important for artists to come from every class in our society, and I encourage artists who aren’t particularly wealthy—who are scraping it together as I’ve had the challenge and delight, at times, to do—to be gentle with yourself and rely, when possible, on a strong artistic community.”

–Anne Stein

Ramírez is also part of Theatre Contra, which stages movie readings at Philadelphia-area bars. Ramírez’s paintings, poems, handmade furniture, and other creations can be seen at jovitoramirez. com. Their first album, There Is No There There, by Jo Vito and the There There, is available on Spotify and other music sites.

When Alex Gendzier ’84 talks about how U.S. veterans are too often deserted by government programs, his voice rises. Ask him, though, how we can help veterans better reintegrate into society after they’ve served their country, and his tone takes on a more sympathetic lilt.

Gendzier recognizes the challenges veterans face in refinding purpose after their military service, which is a core theme in his book, co-authored with former Navy SEAL Rob Sarver. For Warrior to Civilian: The Field Manual for the Hero’s Journey (Balance/ Hachette), they spoke to hundreds of veterans, coaches, health professionals, pastors, and others to craft a guide mirroring the popular literary archetype of the hero’s journey, riffing off Gendzier’s ancient Greek and Native American studies at Haverford.

Based in New York and Dallas as the general counsel and chief compliance officer at Sycamore Tree Capital Partners, Gendzier began to tinker with ideas for the book when his older son told him he was going to enlist. “I wanted him to have something in that moment because I was aware that the transition to civilian life for most veterans is extremely difficult,” he recalls. “And when he gets out, I may not be around.”

Gendzier spoke to Haverford’s David Silverberg about the many ways veterans can find purpose after they’ve fought for their country and lean into the learning curve of becoming a civilian again.

David Silverberg: What are some of the main challenges veterans face when they return to their civilian lives?

Alex Gendzier: Putting aside healing from wounds that can be deep, whether visible or invisible—the number one issue that comes up over and over again is the search for a new identity, a new sense of purpose in life. The fundamental issue is coming to grips with the

idea that you no longer have a cause in uniform that is transcendent to you or the country.

There’s this phrase from the military, “You have to fight as hard inside the wire as outside.” So outside the wire is combat. Inside the wire is home or your base. And how do you do that in a way where you can live? Not as someone with two different realities or life experiences, but a combined new one. And if you do that, you can find great new meaning in your life journey and self-narrative. You develop a chance to lift up those around you, such as your family, your friends, your community, your country. That is what the hero’s journey is all about.

DS: A Deloitte survey found that about one in three American veterans say the military prepared them somewhat well for transitioning to civilian life, and four in 10 said the military didn’t prepare them too well. What’s your reaction to this finding?

AG: The transition to the military is an enormous one. It becomes your entire sense of self and purpose. But nothing in the military is meant to prepare you upon exit. It’s not what it’s there for.

The Department of Defense with the Veterans Affairs Department and the Department of Labor have run a program called the Transition Assistance Program, available within each branch the military, and we have studied them, interviewed dozens of people about them. And it’s a failure. The instructors are well-intended people, but they end up viewing this as a resume-writing and fast job-placement endeavor. Veterans do need jobs. And there are many companies looking to make a buck placing veterans into jobs, but they miss the point and do damage with rushed and ill-advised placements just to say they did. What’s the proof? The statistics don’t lie. On average, within one year, 44 percent of veterans who get a job leave the role, and by the second year, that figure reaches 80 percent.

DS: Your book includes a chapter on the role that families of veterans can play in this transition. Why did you include that section?

AG: It’s an issue of enormous importance that is overlooked in our country. Families, like veterans, don’t prepare in advance for that change of purpose

and identity. There’s a lack of preparation of where to live, what job to get, how this transition affects children. And the transition they undergo is as important and as challenging as that of the veteran.

For example, there’s a spike in divorce rates among families once the veteran separates from the military, and the truth is, it’s due to inadequate planning, not communicating effectively, and not having coaches to help them.

DS: A chapter I didn’t expect to see was one focused on plant- and psychedelics-based therapy for veterans.

AG: We struggled with this inclusion because it’s a very controversial topic. But we encountered story after story of those dealing with different forms of injury, whether from Iraq or Afghanistan service, whether through traumatic brain injury or PTSD, and how they have lost hope. Some have found help with psychedelics and plant-based remedies where no conventional remedy made a difference.

There is a disproportionate amount of negativity and cynicism around these therapies. But there is a lot of new, cutting-edge work being done in this area. We’re not talking about going to the corner bodega to get high, we’re talking about responsibly supervised, science-based programs.

DS: I read that you believe Warrior to Civilian also has lessons to share with those who were never involved with the military.

AG: It’s a book that has universal appeal. This is not just for veterans but also for the guy that loses his wife to cancer who has to raise two children by himself. And then those children go off to college to have lives of their own. And that guy then has to find a new job in his 50s. Well, that’s me. And all those moments are huge life transitions. I am not unique. Everyone has momentous life transitions. We civilians have inspiring lessons to learn from the heroes’ journeys of veterans. In these stories and our own, one can find great nobility of purpose, dignity, joy, and love.

David Silverberg is a journalist and writing coach in Toronto who has been reviewing books and interviewing authors for more than 15 years.

KIRSTEN MENGER-ANDERSON ’91: The Expert of Subtle Revisions (Crown)

In her debut novel, MengerAnderson has crafted a time-travel mystery infused with mathematics, memory, and identity set in 2016 California and 1930s Vienna. In Half Moon Bay, Ca., Hase, who spends her spare time editing Wikipedia entries, investigates her father’s disappearance as cryptic clues lead her to a machine: some sort of music box rumored to hold the power of time travel. At the same time, mathematician Anton Moritz navigates Europe’s intellectual circles as fascism rises and World War II looms. Deemed “an appealing intellectual mystery” by Publishers Weekly and featured in the Washington Post’s notable books for March, The Expert of Subtle Revisions plumbs the complexities of time and the narratives we construct for ourselves.

RICHARD STEELE ’74: Ambassadors in Chains: Four Christian Prisoners of Conscience (Cascade Books)

In Steele’s compelling study, he profiles four Christians— Perpetua of Carthage, Maximus the Confessor, Thomas More, and Martin Luther King Jr.—from vastly different eras who were all imprisoned for their opposition to unjust state policies. Drawing on writings and historical context, Steele provides insight into how faith sustained them through incarceration and highlights their continued relevance amid contemporary challenges of authoritarianism and religious nationalism. This book, which Steele worked on for nearly 25 years, is a valuable resource for anyone interested in social ethics, penology, or prison ministry.

JED BRODY ’96:

The Joy of Quantum Computing: A Concise Introduction (Princeton University Press)

In his latest work, Brody offers an engaging and accessible exploration of quantum computing, exploring its foundational algorithms and applications while distilling the field’s complex concepts into a digestible narrative that requires only a precalculus background to understand. Brody’s concise volume is an educational resource and a philosophical journey into the quantum realm, proving that quantum information science is much more than high-speed calculations and data security.

LINDA GAUS ’87 (TRANSLATOR):

Huts Full of Character: 52 Charming Huts in the Alps (Schiffer Publishing)

This vivid photographic guide, which Gaus translated from German, invites readers to explore 52 charming huts nestled in the Alps across France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Liechtenstein, Austria, and Slovenia. The rustic retreats are an important part of alpine culture, offering food, accommodation, and stunning views. Gaus’ translation brings the charm of these mountain havens to English-speaking audiences and armchair adventurers. No passport or hiking boots needed.

DAVE BARRY ’69:

Class Clown: The Memoirs of a Professional Wiseass: How I Went 77 Years Without Growing Up (Simon & Schuster)

The longtime humor columnist takes readers across the arc of his life in prose that’s, yes, funny, but also at turns probing and heartrending. Barry, known for taking almost nothing seriously, gets introspective and philosophical while talking about his family, his early life, and the various stages of his career, right through his decisions to quit his

long-running column and eventually write a memoir. Barry’s time as a Ford features prominently: He recounts naming his college band, Federal Duck, after a mind-altering experience at the Duck Pond and, as an English major, reading “roughly a third of the way through many great literary works.”

STÉPHANE GERSON ’89 (EDITOR):

Scholars and Their Kin: Historical Explorations, Literary Experiments (University of Chicago Press)

This anthology of 10 essays probes the intricate process of historians writing about their own families. Through a range of writing styles, the contributors explore the give and take of personal narratives and historical analysis while touching on themes of memory, identity, and the complexities of familial research. Scholars and Their Kin provides a new perspective on historiography and the insights that emerge when scholars turn their analytical gaze inward.

MARK RUSS ’75:

The Family Guide to Psychiatric Hospitalization (Johns Hopkins University Press)

Every year, millions of Americans face psychiatric hospitalization, but the process can be stigmatized and cloaked in mystery or misunderstanding. In this guide, Russ, chief medical officer for Silver Hill Hospital in New Canaan, Conn., offers patients and their families critical information to navigate this challenging process. Drawing on his dual perspectives of physician and patient, Russ’ unparalleled understanding of psychiatric hospitalization shapes this guide into a testament to the healing power of compassionate care.

BLYTHE COONS ’01 (CO-AUTHOR): The Motivated Speaker: Six Principles to Unlock Your Communication Potential (Wiley)

Coons and her co-authors have created a practical guide that collates decades of collective coaching experience into six principles for effective communication. By drawing from their backgrounds in theater and executive coaching, the authors provide insight into the necessary habits and mindsets to empower speakers to connect with their audiences authentically. The Motivated Speaker is a valuable resource for professionals looking to enhance their speaking skills and perform like superstar TED speakers and Fortune 500 leaders.

JONATHAN GROSS ’85: The European Byron: Mobility, Cosmopolitanism, and Chameleon Poetry (Anthem Press)

Gross, a professor of English at DePaul University, examines how Lord Byron’s literary persona was informed by European writers like Thomas Moore, Percy Shelley, Torquato Tasso, and others. The European Byron seeks to better understand Byron’s concept of “mobility” by highlighting the various cultural identities and literary styles he adopted. Gross also ties Byron’s influence to Slavic poets, demonstrating his impact across boundaries and the 19th century’s literary landscape.

DAVID FELSEN ’92: New York City Monuments of Black Americans: A History and Guide (The History Press)

Felsen’s guide is a thoughtful exploration of the New York City monuments honoring Black Americans. While tracing the evolution of the city’s monuments—from the nameless symbolic figure depicted

in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery to the first monument dedicated to a Black woman, Harriet Tubman—Felsen, an 11th-grade history teacher, provides context and insightful narratives for 30 sites. Felsen takes great care to highlight stories of triumph over great adversity to provide a deep understanding of New York’s rich Black history.

ROBERT WHITE ’69: Bad Fathers, Wicked Stepmothers, Cannibalistic Witches, Amorous Princes: The Psychoanalytic Study of Fairy Tales (Ethic International Press)

Through his scholarly examination, White probes the psychological themes of classic fairy tales through Freudian theory and psychoanalytic critique. White explores the themes of desire, repression, and parental ambivalence featured in these seemingly simple stories to reveal the emotional structure encoded within them. Featuring both accessible prose and clinical insight, the book is a fitting read for scholars, mental health professionals, or anyone interested in the darker themes coursing through classic childhood stories.

WILLIAM W. MALANDRA ’64: The Bundahišn: Translated With Commentary (Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph No. 68)

Malandra’s scholarly work is an in-depth English translation of the Bundahišn, an important Zoroastrian text that details ancient Iranian cosmology. Completed just before the Arab conquest of Iran, Bundahišn is a record of pre-Islamic religious thought. Malandra’s commentary throughout helps unravel complex passages and places the text within broader literary and religious traditions.

FORD AUTHORS: Do you have a new book you’d like to see included in More Alumni Titles? Please send all relevant information to hc-editor@haverford.edu.

When Jordan Stuart ’05 played soccer for Haverford, he was all about defense. Now he’s focused on setting—and reaching—goals as an owner of two professional teams in the burgeoning U.S. soccer ecosystem.

BY CHARLES CURTIS ’04

Jordan Stuart ’05 never dreamt, when he was running up and down the pitch as a defender for Haverford’s soccer squad, that he’d someday be an owner in the sport he loved.

But that’s where the political science major and Bryn Mawr, Pa., native finds himself today, a part-owner of not one but two professional soccer franchises. First, there’s Loudon United FC, a men’s team based in Leesburg, Va., that competes in the United Soccer League Championship (a second-division league beneath Major League Soccer [MLS]). Then there’s the DC Power FC, a women’s team in the nation’s capital that plays in the top-tier USL Super League (it’s on par with the National Women’s Soccer League).

There he serves as club president, having built the team from the ground up after it was founded in 2024 and signed up big-name investors including WNBA star Angel Reese and MLB All-Star Josiah Gray.

So how did he make his way into sports ownership? He told Haverford about how he got here, his big eureka moment, how he juggles multiple jobs at once, and what it means to be involved in soccer as the men’s and women’s World Cups come to the United States in the next several years.

His love of soccer began during the last U.S.-hosted World Cup. In 1994, I was 12, and there was a soccer subculture growing when the

World Cup was here. You started to have talented kids coming together on these travel teams. I was a defender because I couldn’t score. I was a forward for most of my high school career, and then coaches told me there was no such thing as a defensive forward: “If you can’t score, you’re not playing this position.” I took a lot of pride in shutting down scorers from other teams, and that’s what I spent my four years doing at Haverford.

The path to ownership began in real estate. After graduation, I worked in consulting and government contracting in Washington, D.C., but I got my real estate license when I was 24. While sitting in a cubicle in 2014, I had an epiphany. I asked myself: What’s a value-add for me that’s also an entry point for the love of sports I had while growing up outside of Philadelphia? The answer: I started finding housing for pro athletes who were new to the city. I ended up working with every major pro sports franchise in D.C. This led to my current role as the director of sports and entertainment real estate for Keller Williams Realty, where I help athletes and entertainers with real estate needs across North America.

His D.C. soccer connection was made thanks to an all-time great. In 2018, I worked with former England national team captain and new D.C. United signee Wayne Rooney to find him and his family a place to live. That’s how I became close with the owners of the MLS club. They realized I was this independent third party who could bring minority investors into the club, and so I got all kinds of big names to be part-owners: NFL running back Mark Ingram, B.J. and Justin Upton from Major League Baseball, and others. The owners saw I was good at it, so they told me they wanted to give me an opportunity to invest, too. So I invested in Loudoun United FC, which used to be a D.C. United affiliate. A year later, I was asked to be the first club president of the DC Power FC, while also becoming a ground-floor primary investor.

Building a sports franchise from the ground up goes beyond the product on the field. With any grassroots team in its inaugural season, you want a brand identity and you have to field a team, so I was heavily involved in all of that. We had to begin by focusing on our three revenue streams: sponsorships, ticket sales, and consumer products. But we also had to figure out how to sign players and how to get them housing, medical benefits, and so on. Building out the infrastructure of a team before hiring a coach? That’s very difficult. I oversee all day-to-day operations of the team, communicate with players, agents, the league, housing reps. … It’s the most complicated situation.

How the Haverford experience helped on and off the field. You need to have experience and a love for the game, an entry point into the sport where you can tell how one player is 10 percent better than another. But there’s also living that life, practicing every day then going to a philosophy class. It forces you to multitask and pay attention to different things. Also, I wrote so many papers that helped me improve my writing. I think my biggest strength now is writing a succinct email and getting my point across.

The 2026 World Cup is a huge opportunity.

With the men’s World Cup coming to the U.S. next year and the women’s World Cup here in 2031, that’s going to bring a lot of eyes to the sport, as well as a lot of money. I’m creating relationships—not to just produce a winning team, but to bring in sponsors who may have been focused elsewhere. I’m at the forefront of showcasing why our teams and leagues should be relevant. We’re building out the game at every level.

Charles Curtis ’04 is managing editor for USA Today’s For the Win and an author of the Weirdo Academy series, published by Month9Books.

Get updates on your favorite Haverford teams on X (@HCFords_Sports) and Instagram (@HCFordsSports), or visit the Athletics Department website at haverfordathletics.com.

‘‘ At Haverford, I wrote so many papers that helped me improve my writing. I think my biggest strength is writing a succinct email and getting my point across. ”

BY CURRAN MCCAULEY

In the 2024–2025 season, Haverford came to play. Across every playing surface, the College’s student-athletes contributed to one of the most triumphant seasons in recent history. Fords not only notched conference wins and playoff berths, they set new records and garnered national recognition. But success wasn’t limited to competition. Many studentathletes collected academic honors that reflect the College’s commitment to excellence on the field and off. These are just some of the high points of Athletics’ triumphant year.

◄ Eric Chen ’27 became the College’s first-ever U.S. Fencing Coaches Association Division III Men’s Epee Athlete of the Year. The two-time Division III All-American was the only men’s epeeist in that division to qualify for this season’s NCAA National Collegiate Championships in April, where he placed 22nd against athletes from all three NCAA divisions. Chen also won the NCAA Elite 90, awarded the student-athlete with the highest GPA at each championship site.

Fresh off his 2025 Centennial Conference Track Athlete of the Year honors, Reza Eshghi ’25 received All-American honors in the indoor 3,000-meter and oudoor 5,000-meter events. In cross country, Eshghi placed 191st in 25:43.9—an 89-place improvement from 2023. Peter LaRochelle ’25 ► earned Second Team All-America honors in the outdoor 10,000-meter with an 11thplace finish. In cross country, the 2025 Metro Region Runner of the Year earned his second consecutive All-America honor with a 40th-place finish at the 2024 NCAA Division III Cross Country Championships, clocking 24:46.4. Both distance stars conclude decorated collegiate careers marked by multiple NCAA appearances, regional titles, and academic accolades.

After finishing with a program-best 15 wins, Women’s Lacrosse was ranked No. 17 nationally and earned its first-ever NCAA tournament victory. The team’s success was driven by a dominant trio of All-Americans: Brooke Epstein ’26, Tiffany Mikulis ’25 Eva Baumann ’25. Epstein led the Centennial Conference in goals, points, and draw controls, setting multiple program records in the process. Mikulis, a three-time All-Centennial pick, surpassed 200 career points. Baumann anchored one of the conference’s top defenses with 28 caused turnovers.

After going undefeated during its spring regular season, Cricket marked its best result this century at the Philadelphia International Cricket Festival in early May by finishing as the runner-up. Led by Sidd Phatak ’25 ► and Mohanish Bajaj ’25, the team combined aggressive batting with disciplined bowling.

WOMEN’S SOCCER’S standout campaign included its first 10-plus win season and Centennial Conference playoff appearance since 2019. MEN’S LACROSSE finished its season with nine wins, the most since 2011. VOLLEYBALL clinched a spot in the Centennial Conference Championships as the No. 5 seed, marking its 20th postseason appearance in the last 24 years.

Men’s Tennis Men’s Tennis capped a historic 2025 season finishing 16–6, tying the program record for wins, and securing national (No. 16) and regional (No. 4) rankings. The Fords reached the Centennial Conference final for the first time in over a decade and returned to the NCAA tournament for the first time in nearly three decades, where they notched the program’s first-ever firstround win. Coach Eric Spangler was honored as the Intercollegiate Tennis Association Atlantic South Regional Coach of the Year, while six players earned All-Centennial Conference recognition and four received College Sports Communicators Academic All-District honors.