05.23

DESIGN FOR FUTURE LIVING

ARC5051: FUTURE HOMES 2

05.23

ARC5051: FUTURE HOMES 2

This project takes a look at alternative economic and social models for living and sharing space. The brief is to design a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable neighbourhood in Birmingham for the year 2070.

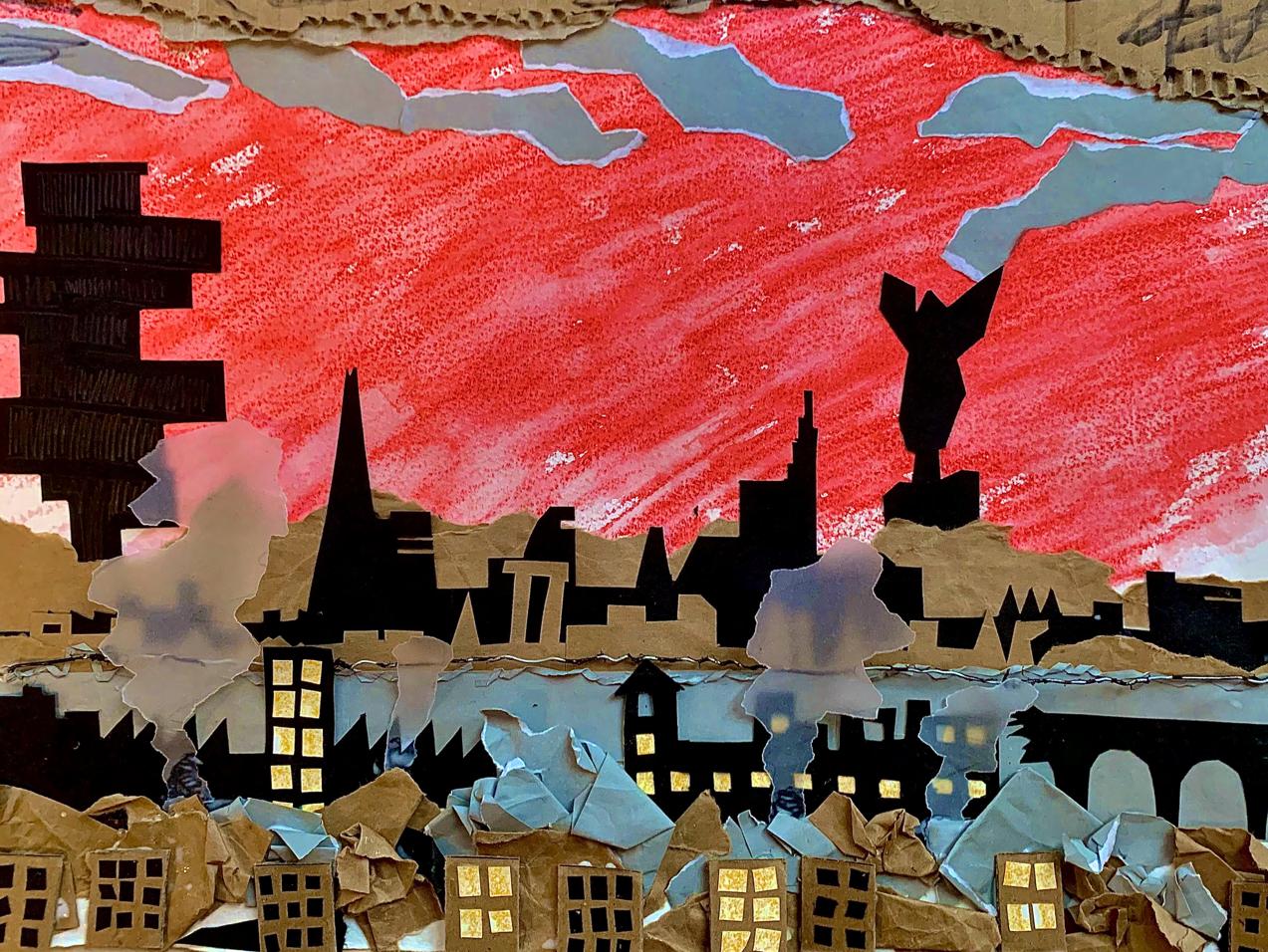

Part 1 begins with an in depth examination of the site and its surrounding context, focussing on movement through space and water management. This is followed by a ‘dystopian vision’ of 2070 exploring the worst case scenario for the site if no positive interventions are made.

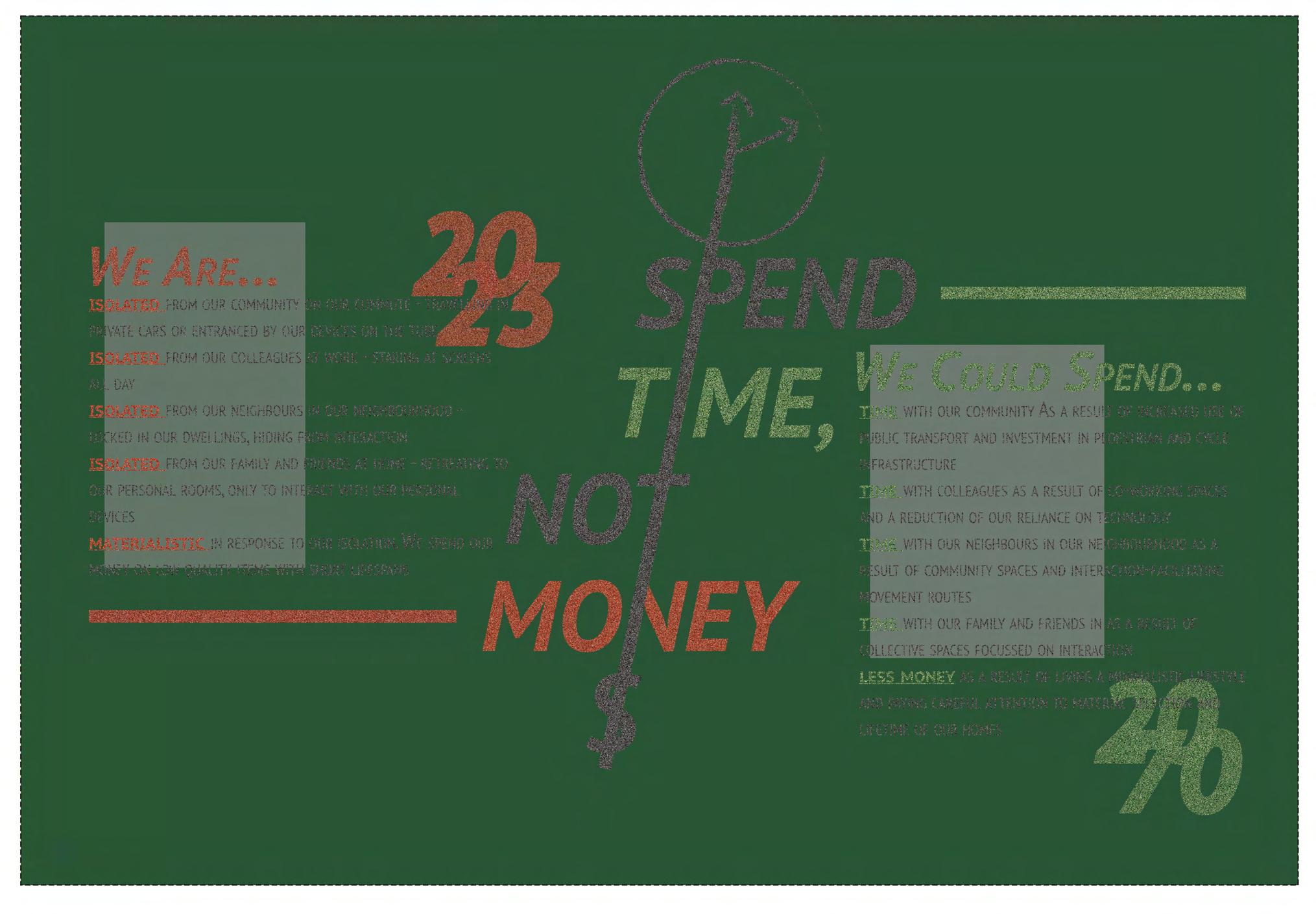

Part 2 responds with an opposing ‘utopian vision’ and manifesto, exploring the interventions necessary to foster sustainable development in our cities. I expand on this by proposing an urban planning strategy inspired by Barcelona’s Superilla.

Part 3 discusses my response to the site, detailing my proposal for retrofitting existing buildings on the site and implementing a movement strategy early on in the design process. I then use numerous precedent studies to research architectural forms and spatial principles which aid my design development.

Part 4 explains my proposal for the site through a series of drawings that use a range of graphical techniques. In this section I divide the site into separate parts, and examine each in detail.

Part 5 documents the design development of the individual dwellings on the site through manual and digital techniques, finishing with rendered plans showing inhabitation and a collage of work representing the conceptual drivers of the overall project.

Enjoy!

The materiality of the local area reinforces its industrial history. The use of steel is a recurring feature but it usually serves the purpose of restricting access to a space. Local buildings are made from affordable materials and are rarely maintained.

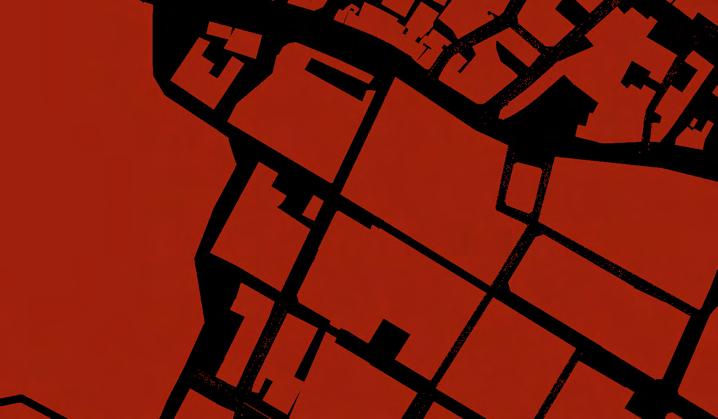

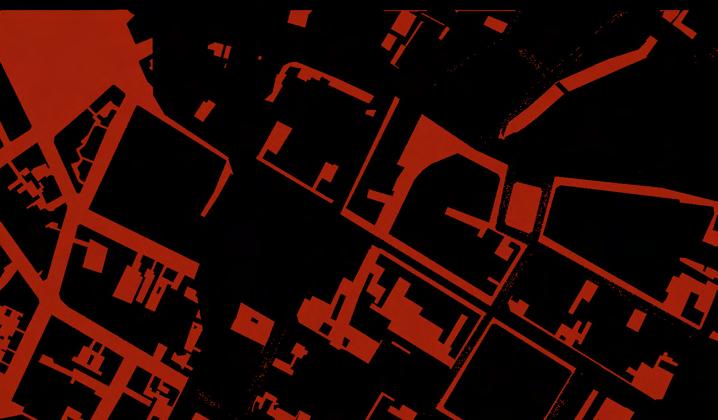

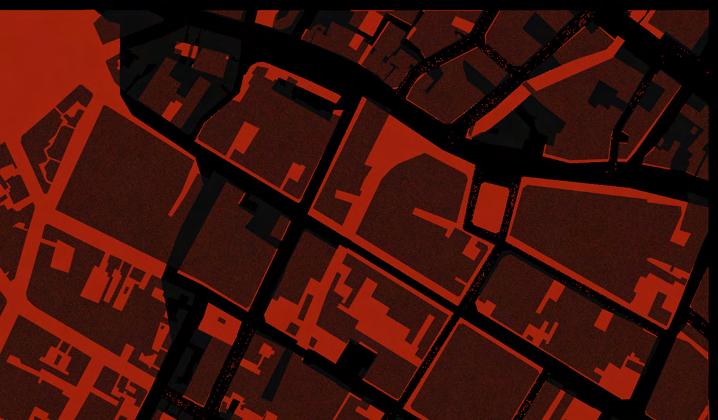

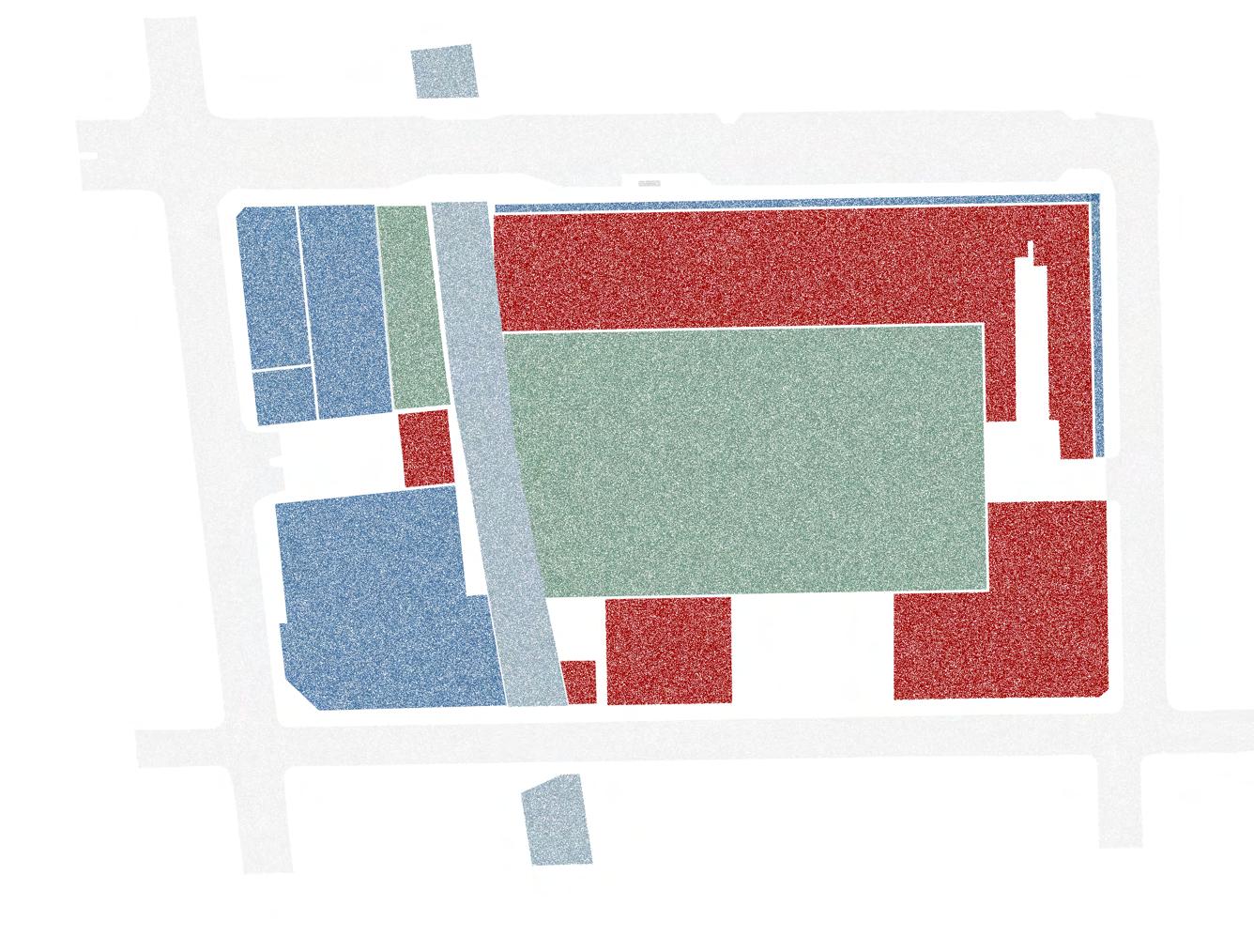

The graphics to the left show how publicly accessible space has changed in the area over time. The top two images show the inaccessible land in 1950 (left) compared to 2023 (right). Once overlaid, we can see how much publicly accessible space has been lost in the last 70 years. Additionally, the entire river bank in the selected area is now inaccessible.

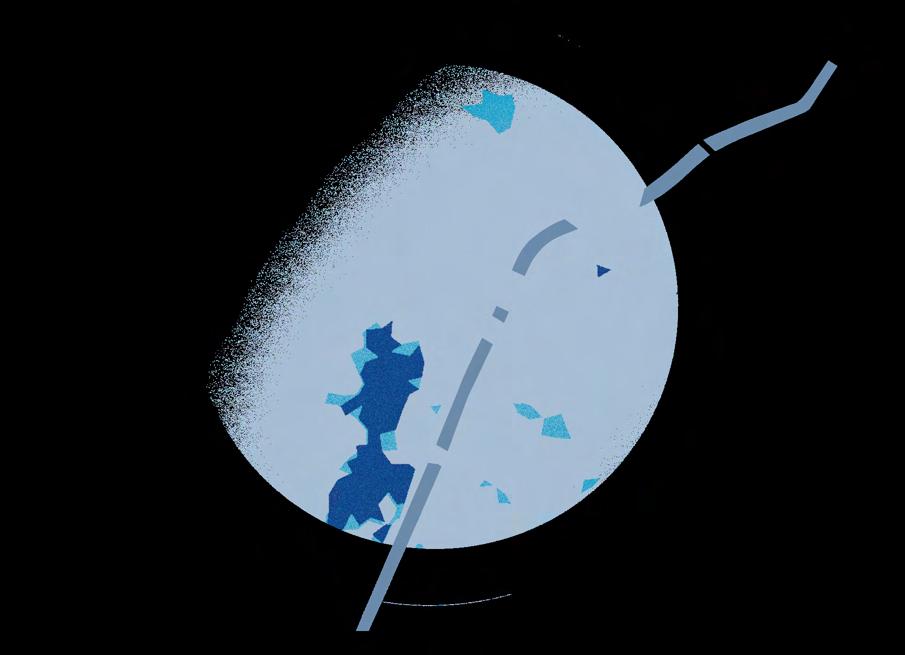

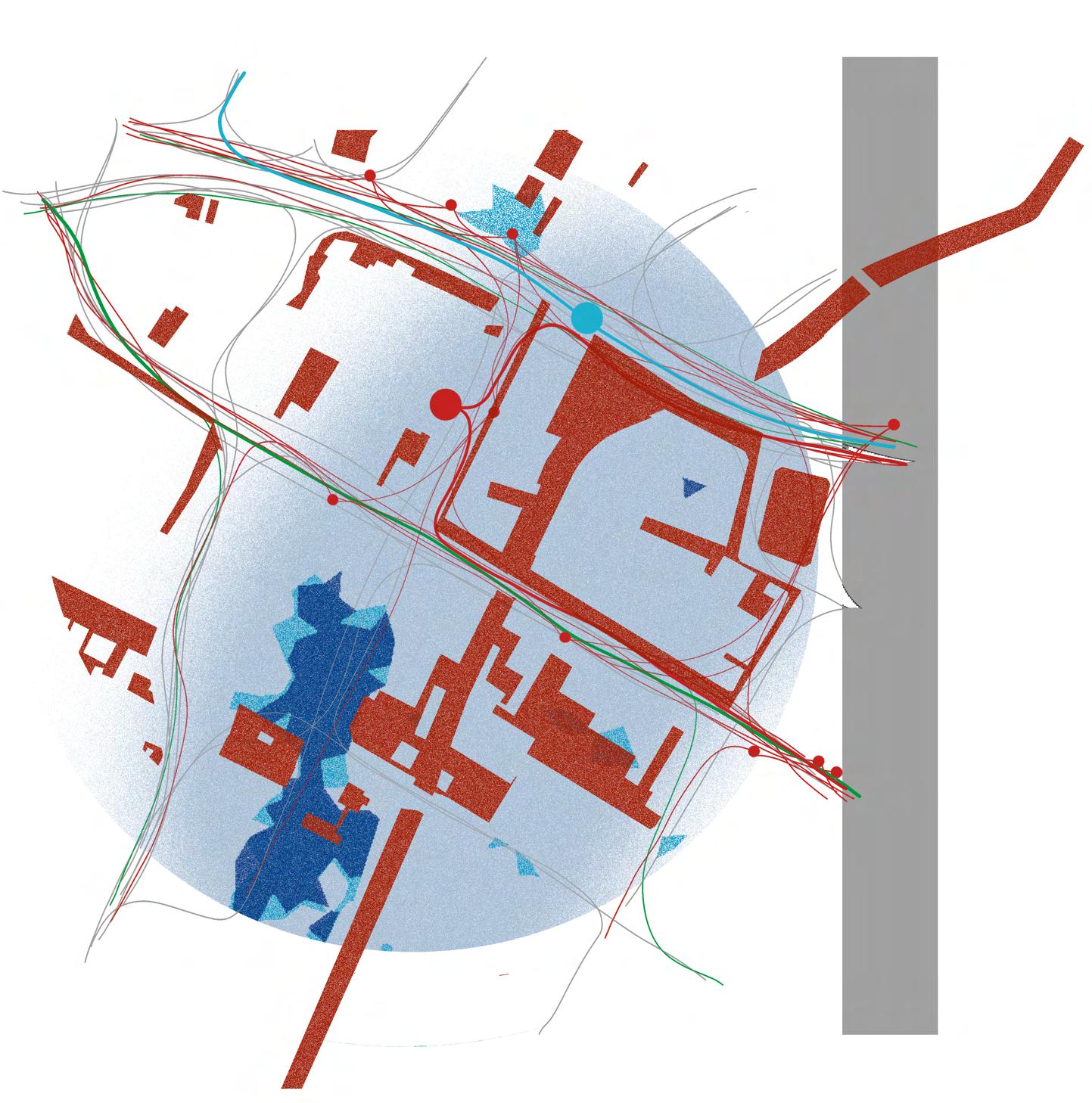

The data maps on the right were composed of primary and secondary data. They highlight the importance of the transport network in the area, notably the coach and tram stations. We also see a lack of vegetation and biodiversity and we notice that the area has a relatively high flood risk. The chosen site is not in a conservation area and includes no listed buildings. It has been earmarked for redevelopment following the Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment (HELAA).

My figure ground analysis highlighted the importance of preserving public access in urban settings. Private housing developments restrict access citing safety and privacy as justification. I would like to use this project to explore design solutions that create privacy and safety while maintaining a permeable threshold around the site to create a greater sense of freedom for local residents.

I would also like to re-wild the river bank, introducing biodiversity and re-establishing a connection between local residents and the natural resources the river provides. I believe this could foster a sense of empathy towards nature that is so easily lost in cities.

Public transport investment is high in local area, and the coach station connects Rea Street not just to Birmingham, but the rest of the UK. I want to use this project as an opportunity to imagine the future of transportation, cycling and pedestrian movement in an urban context.

River and surface water flooding pose a risk to the site and surrounding area, especially when considering the rise in extreme weather events we are likely to see in 2070 as a result of climate change. I would like to use this project to explore sustainable urban drainage solutions and water filtration to reduce the risk of flooding and improve water quality in rivers.

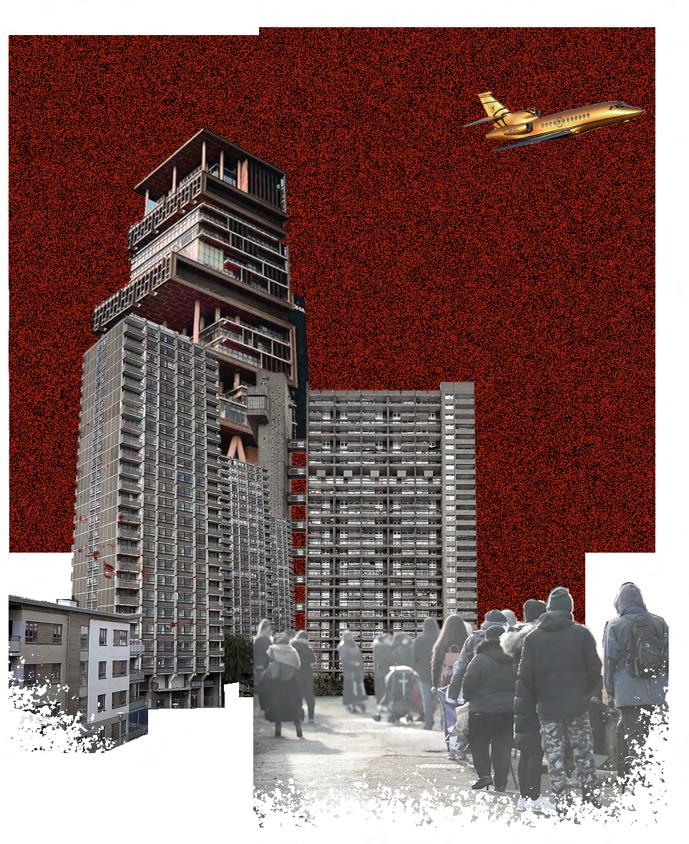

The collage above features Antilla, Mumbai - the private residence of a billionaire that is situated near several slum areas. It is a symbol of gross inequalities in cities. This contrasts with the foreground, depicting 1970s social housing blocks and a queue for a food bank. The background is reminiscent of my urban grain study - recognising how access to basic needs is restricted as a result of privatisation.

The following is the worst-case scenario for 2070:

1. Extreme weather; climate change has caused storms, floods and draughts.

2. Inaccessibility; well-insulated houses, electric cars and other sustainable technologies are only accessible to the rich, causing greater wealth disparity.

3. Gentrification; high-end private developments have driven up land prices, displacing communities.

4. Pollution; manufacturing and construction industries continue to pollute without condemnation or regulation.

5. Neglected heritage; historic buildings have been demolished in favour of short-term economic growth.

5. Neglected heritage; historic buildings have been demolished in favour of short-term economic growth.

6. Homogeneous mass housing; the few attempts the government made at building social housing resulted in substandard and psychologically damaging homes

7. Neglected public space; empty plots and derelict buildings stand where parks and playgrounds should lie.

8. Failed transport infrastructure; people remain reliant on private cars.

9. Neighbourhood divisions; physical and psychological divisions contribute to hostility, violence and crime.

10. Authoritarianism; citizen power is at an all-time low.

In J.G Ballard’s book The High-Rise, he writes “The high-rise was a vertical city, and like all cities it was a place of many classes, each separated from the others by subtle psychological barriers ... between the higher and lower floors.”

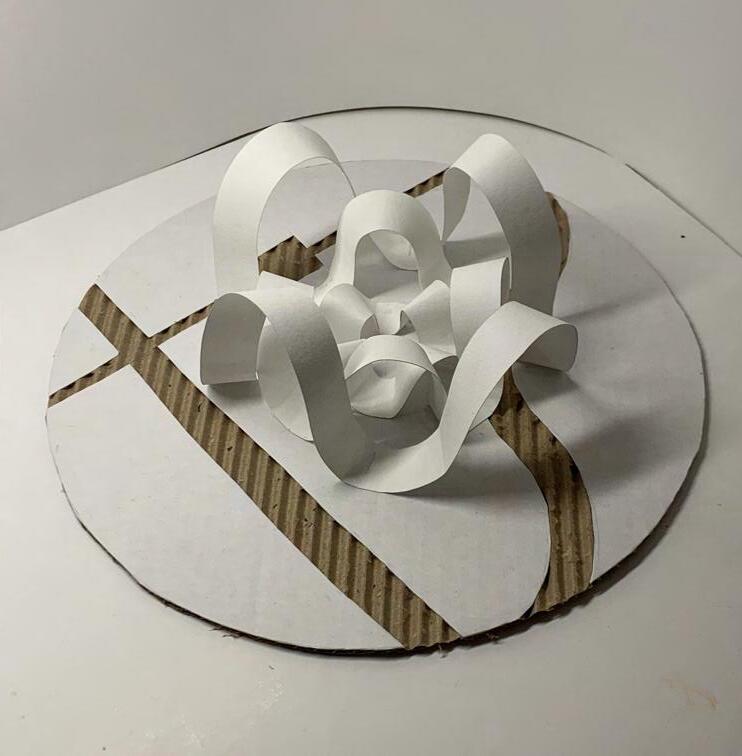

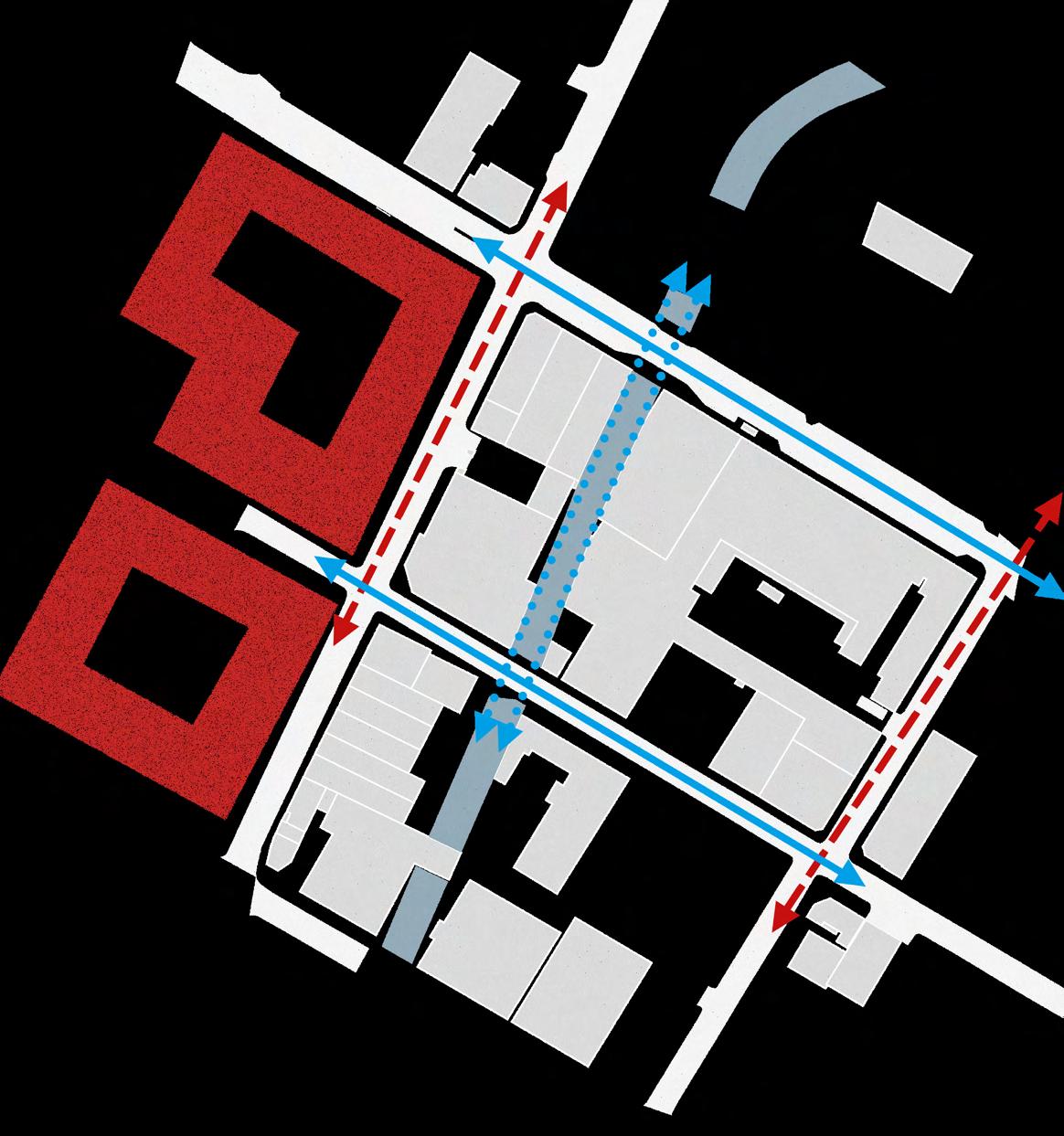

In the model, the high and low floors are connected in the middle, forming a symbolic meeting-ground and recognising how different income groups can benefit from living and working together. I believe a utopian future of housing would bring high- and lowincome groups together in harmony, reducing division.

Movement through Urban Scales

In Part 1.4 and 1.5, I identified the significance of public trasport and the river Rea in the district so I want to ensure this feeds through into the neighbourhood scale. I want my site to make provisions for public transport and river access.

I also noted the importance of free pedestrian movement through neighbourhood blocks. This will be key in my masterplan development.

District Neighbourhood

High Low

Interdependence

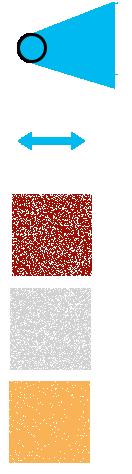

Chief Executive of Open City, Phineas Harper told the Guardian (2018) that “Congestion is not reduced by building more roads, but by reducing roads and making it less convenient to drive.” He argues that reducing roads in a city makes people turn to alternatives like public transport and cycling. Using this principle, I propose a new movement strategy in Digbeth and Deritend.

The primary roads would remain as they are but secondary roads would only be for public transport and deliveries. Cycling and walking would be prioritised on all routes in some cases would be the only option. This would reduce transportrelated emissions, increase safety and improve the quality of life in the district.

This scheme takes inspiration from Barcelona’s “Superilla”, where the majority of traffic is restricted to the perimeter of a 3-by-3 block square and any traffic within is subject to strict requirements and speed limits.

Primary roads

Secondary roads

Primary pedestrian routes

Secondary pedestrian routes

Smithfield Development

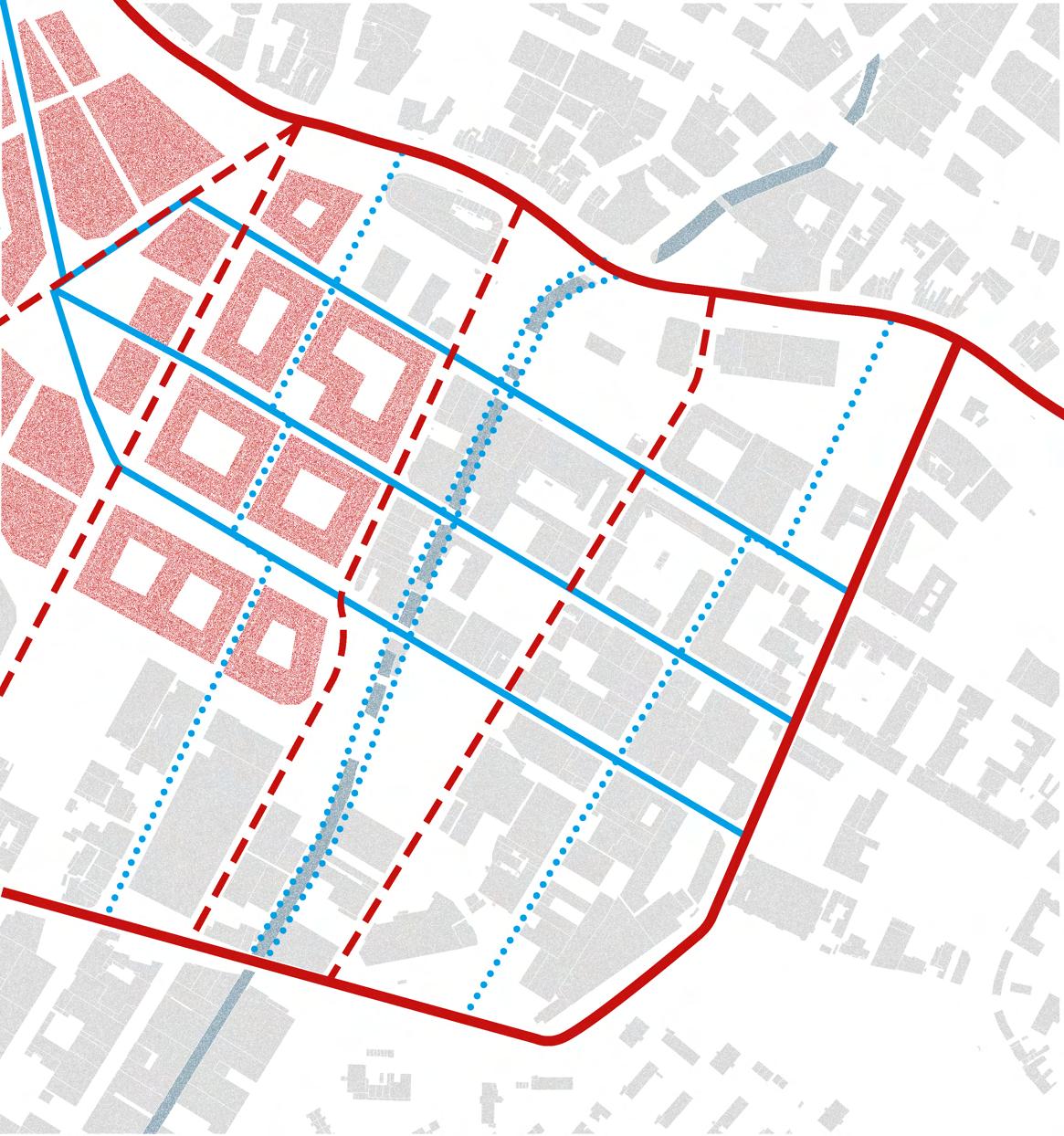

Plans for the redevelopment of Smithfield Market into a collection of residential, commercial, and civic spaces have been approved, so my vision for 2070 will assume the redevelopment is complete. The nearby blocks (shown in red) are mostly residential and feature private central courtyards.

Permeable Boundaries

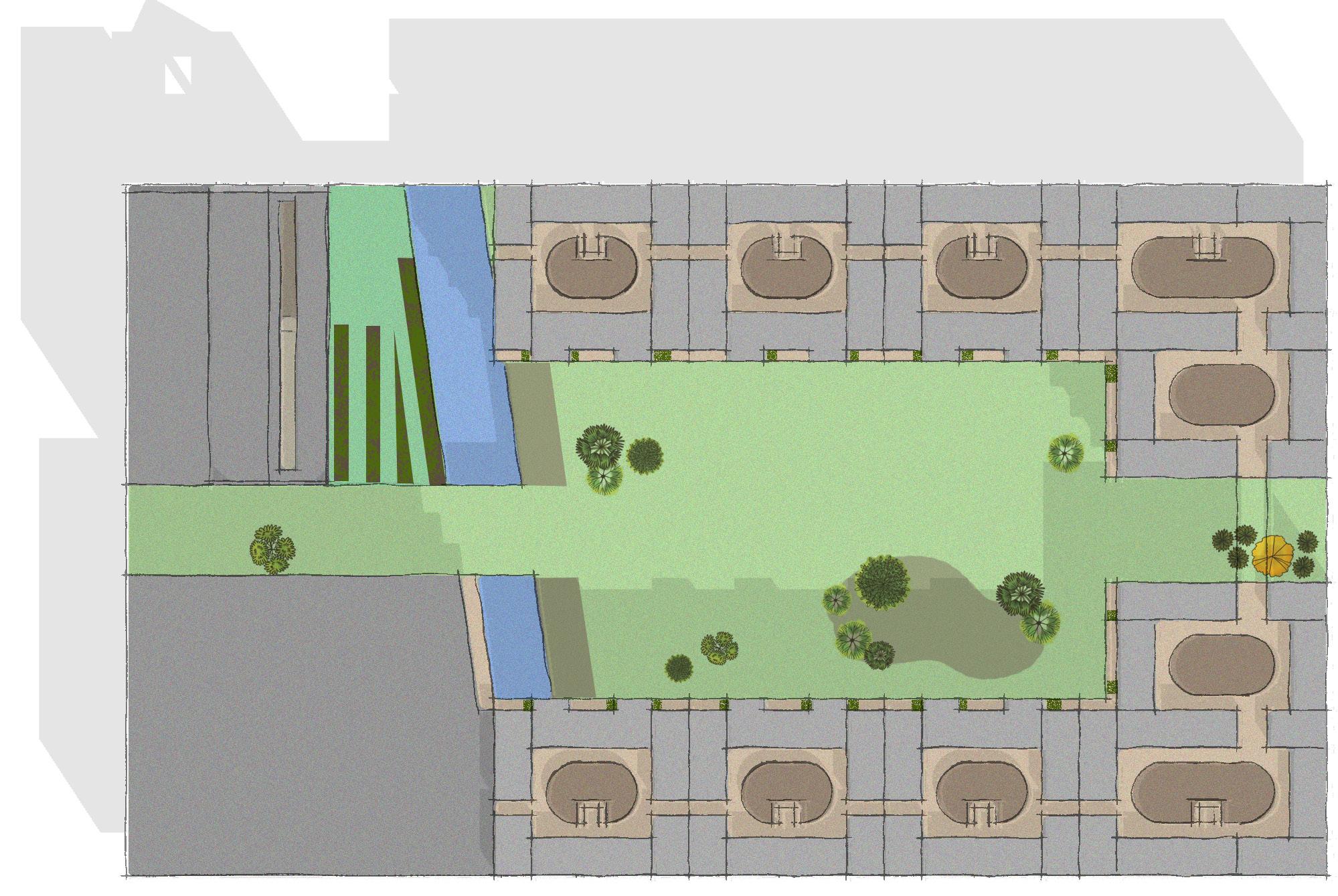

Unlike the Smithfield neighbourhoods, this site will allow pedestrian access through the site. This will strengthen the resident’s connection with the district and allow locals access to the river bank.

Versatility

As shown in the district plan, this neighbourhood plan could be repeated in similar locations around Birmingham. Therefore, I intend on making my design versatile enough to adapt to different areas.

Secondary roads

Primary pedestrian routes

Secondary pedestrian routes

In 2019 the Architects Journal introduced a new campaign called RetroFirst promoting the reuse of existing buildings to reduce demolition waste and the need for carbon-heavy new-builds. They state that “it is essential that we think reuse first, new build second”. That is why I have developed a strategy to retain and reuse existing buildings.

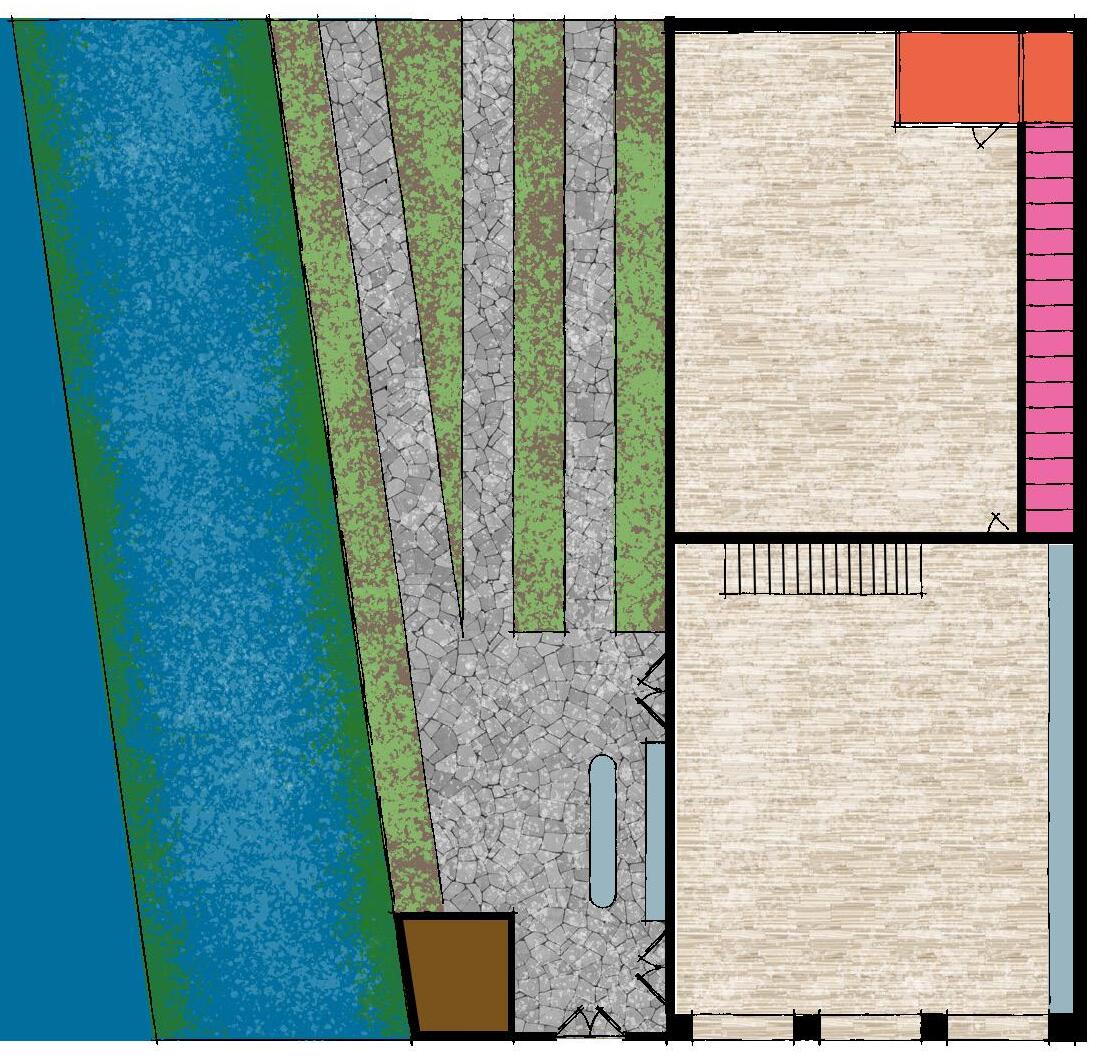

1. This four-storey brick building is in structurally sound condition and could be retrofitted for residential use.

2. I believe this old warehouse is an important part of the history of this site. The facade and structural steel could be retained but a new roof and side wall will be required.

3. This storage unit next to the river is in poor condition and not worth keeping. I propose it to be demolished and planted as a neighbourhood vegetable garden.

4. The existing facade on Bradford Street is historically significant for the area. I propose retaining the facade and building up to it.

5. St. Eugene’s Court is a 46-bed property providing longterm social housing, advice, and support to Birmingham residents. I propose keeping the structure and function but performing minor alterations to open it up to the rest of the site.

6. This bridge extension of St. Eugene’s Court restricts views and access to the rest of the site so should be demolished.

7. The remaining buildings are in poor condition. I propose demolishing them and constructing new residential buildings in their place.

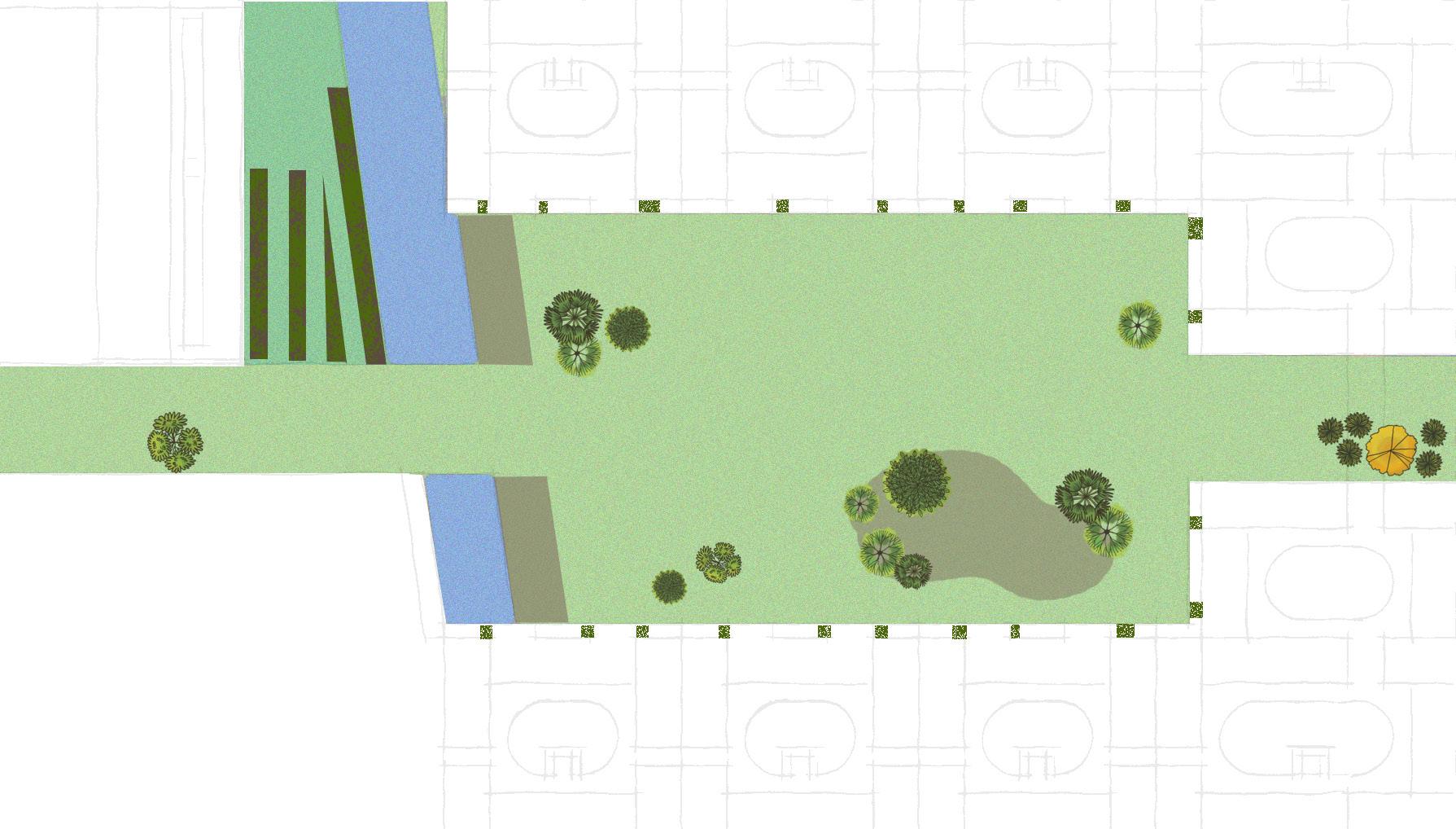

8. The condition of the inner courtyard is poor so I propose replacing it with a large central park with an integrated flood protection system.

Retrofit/Retain Demolish and Plant Demolish and Build

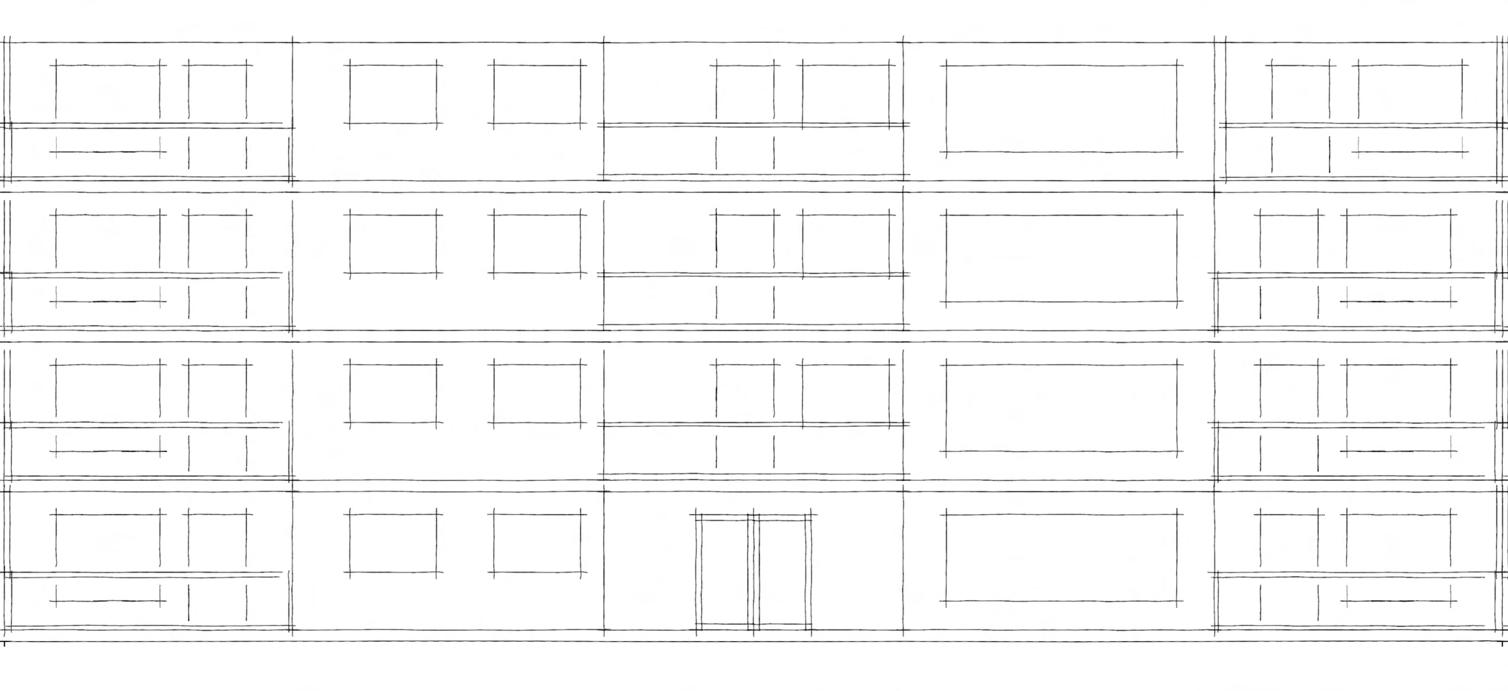

In light of the ongoing shortage of housing stock across the UK, I decided this development should be high-density, at around 200 dwellings per hectare.

Based on the English Housing Survey (2021), 29% of people in the UK live in 1-bedroom properties, 38% in 2-bedroom properties, and 24% in 3-bedroom properties. To have a balanced mix of housing in my development, I aim to divide it equally into these three property sizes.

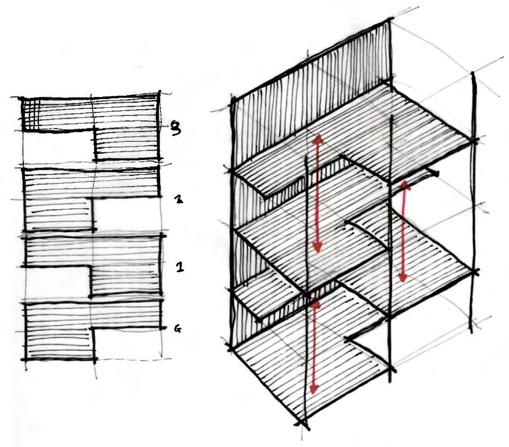

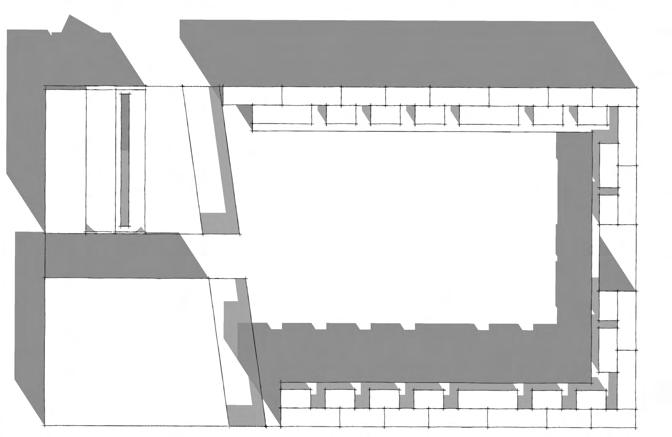

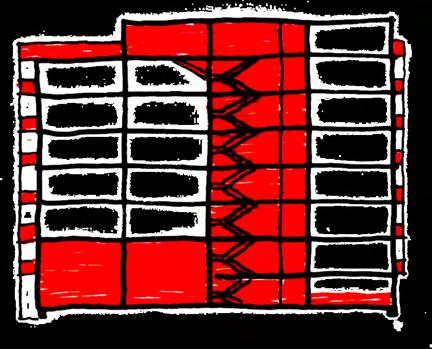

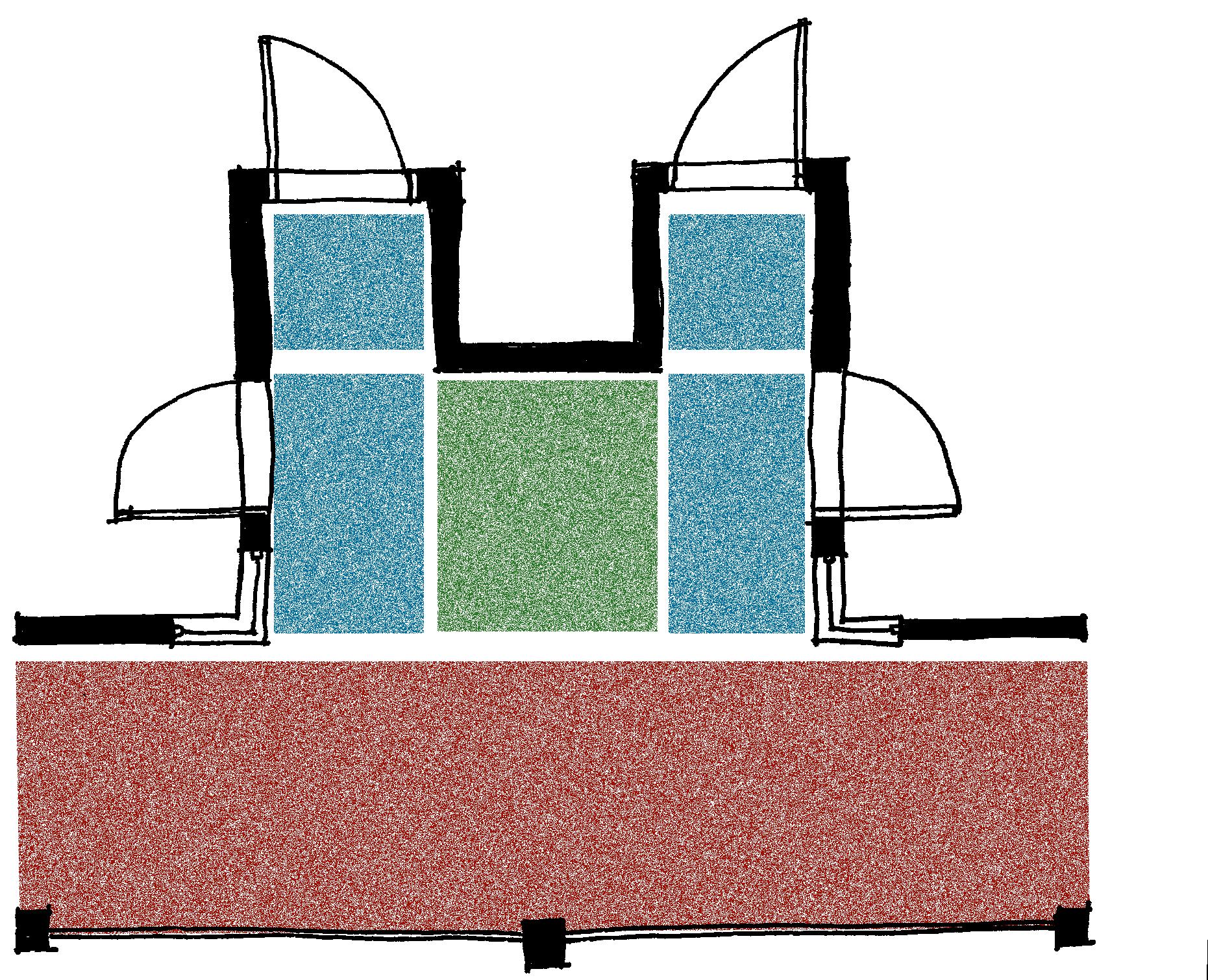

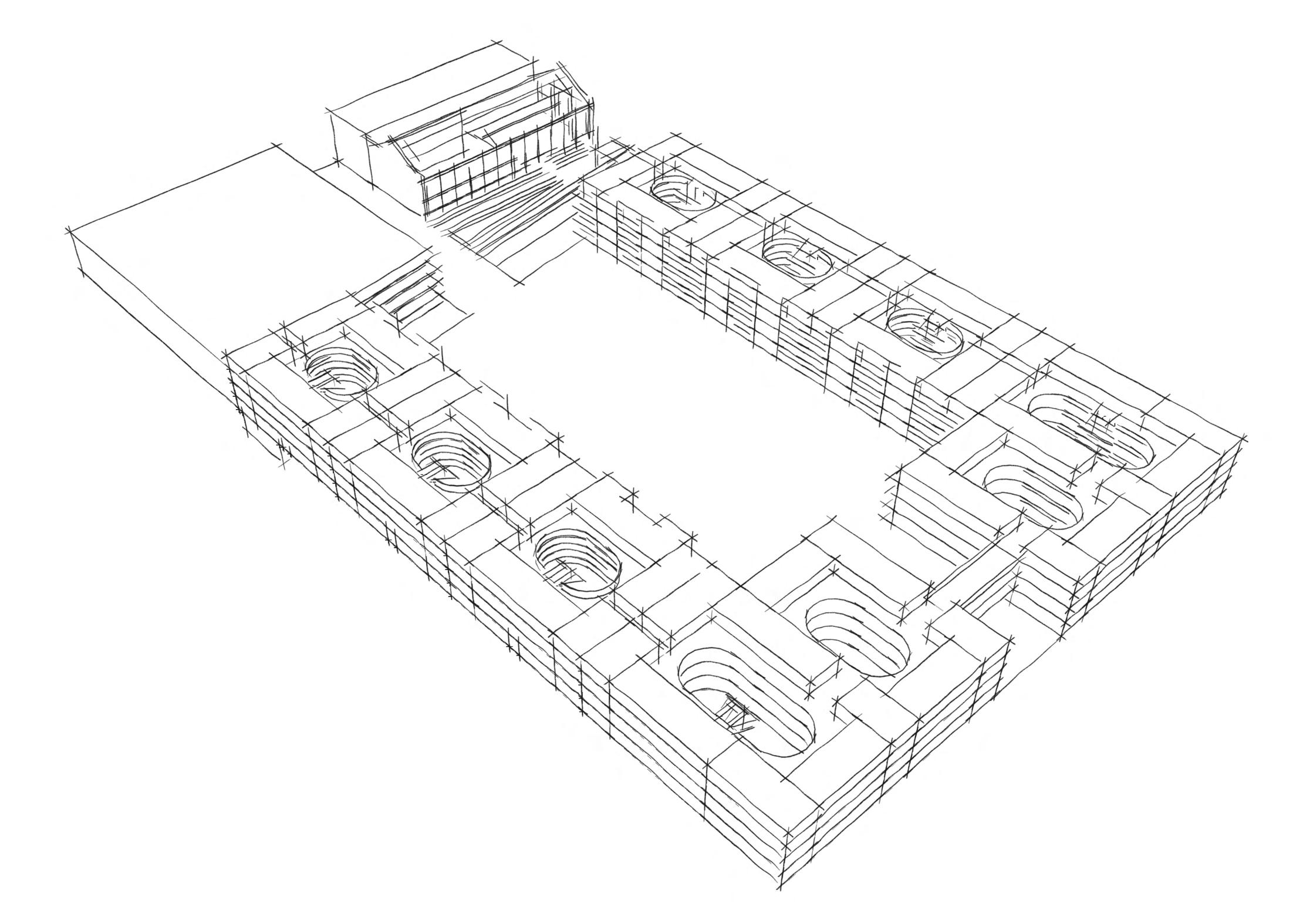

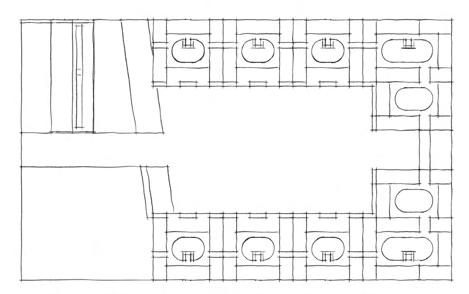

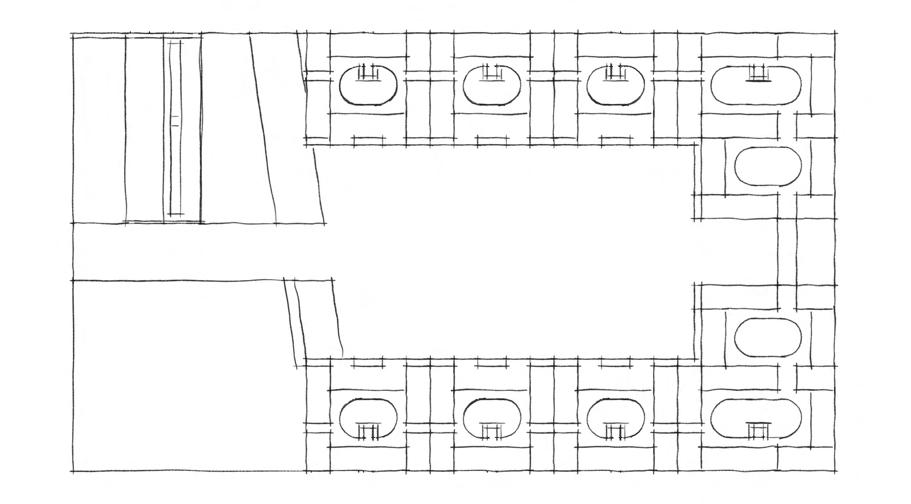

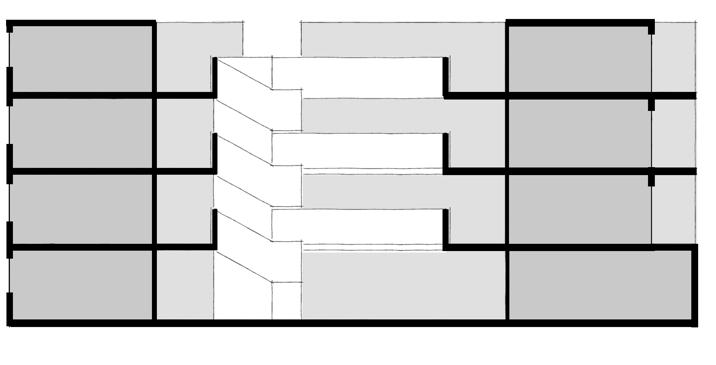

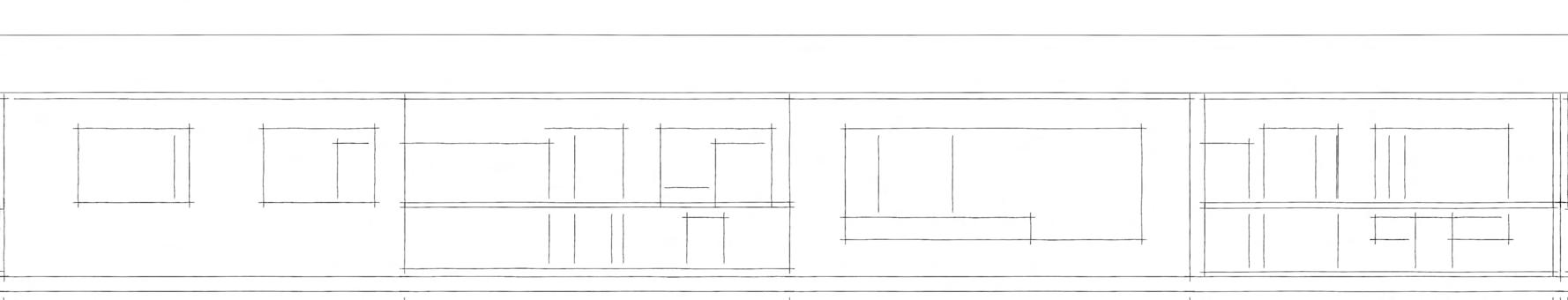

Using a representative sample of each property size, I experimented with numerous arrangements to see how they performed differently. The best two are shown on the right.

While both designs employ a deck access strategy, design ‘B’ creates a more communal environment due to the arrangement around a shared courtyard. This also allows for passive surveillance of neighbour’s front doors, increasing security.

The flats in ‘A’ are all single-aspect, but those in ‘B’ are all double-aspect. Studies show that double-aspect flats had better indoor air quality, received more natural ventilation (Wildevuur, S. 2019), and provide residents with higher levels of well-being than to single-aspect flats. (Kim, J. 2013)

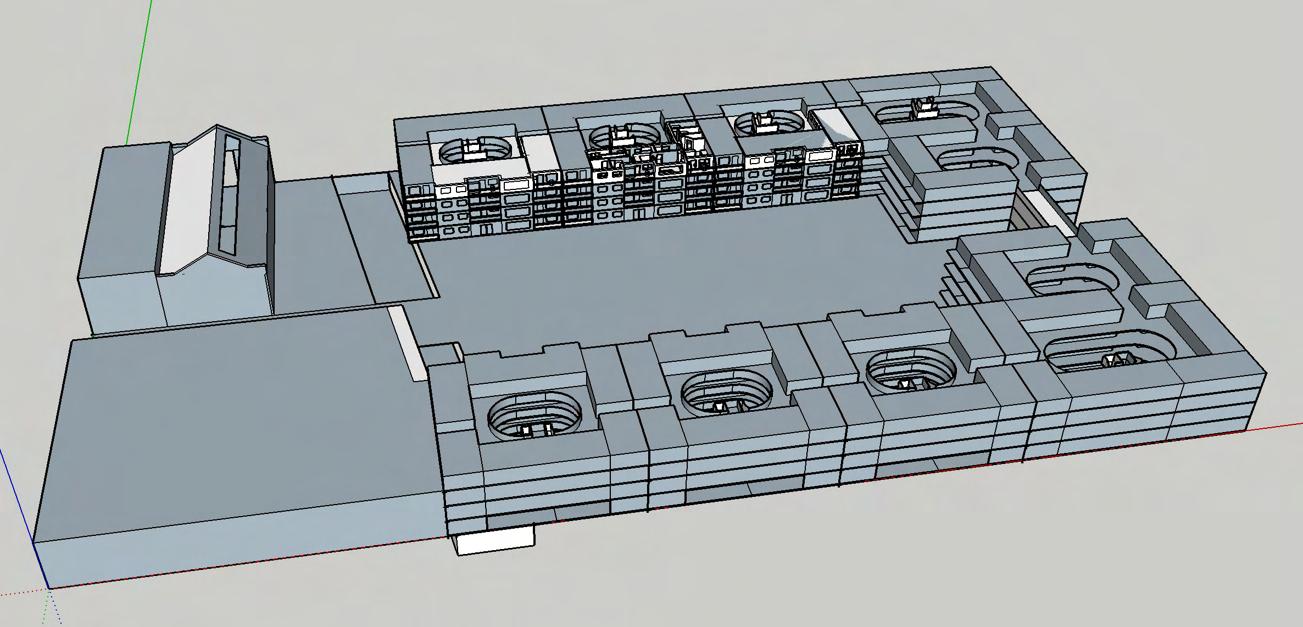

The shadow studies show that the inclusion of courtyards in ‘B’ provides direct sunlight to more dwellings. It also allows for more dwellings per floor. Standing at 4 storeys, and including the retrofit of the existing buildings, design ‘A’ would provide 220 dwellings, achieving a density of 149dph. Design ‘B’ would provide 304 dwellings achieving a density of 206dph. Therefore I will proceed with ‘B’ as my final choice.

Views / Daylight Ingress

R50 by Ifau und Jesko Fezer and Heide & von Beckerath is a co-housing scheme in central Berlin. It is the product of a ‘Baugruppe’, or building group, consisting of 19 households who pooled their funds to build their new home. This investment model bypassed any commercial developer which reduced the price and gave the residents design flexibility. They worked alongside the architects in the design process, collaboratively designing their individual flats and communal spaces.

Each floor (excluding the first and loft) has three flats, each with access to a shared balcony that wraps around the building. This blurs the line between private and communal space. The balconies are accessible to all residents although they are predominantly used by the flats on the same floor. While residents can access their neighbours balcony, this would mean standing in front of their floor-to-ceiling windows so a psychological threshold is created between private and communal space, allowing the residents to take ownership of their section of the balcony. This is an architectural symbol of the trust and respect that is required for co-housing to work.

The design facilitates impromptu meetings in the bicycle parking area and communal kitchen or on the landings or rooftop garden. On the other hand, the plan is carefully arranged to give residents an option between a public route to their flat or a more private route. This is a recognition that co-housing should be designed with reclusive days in mind.

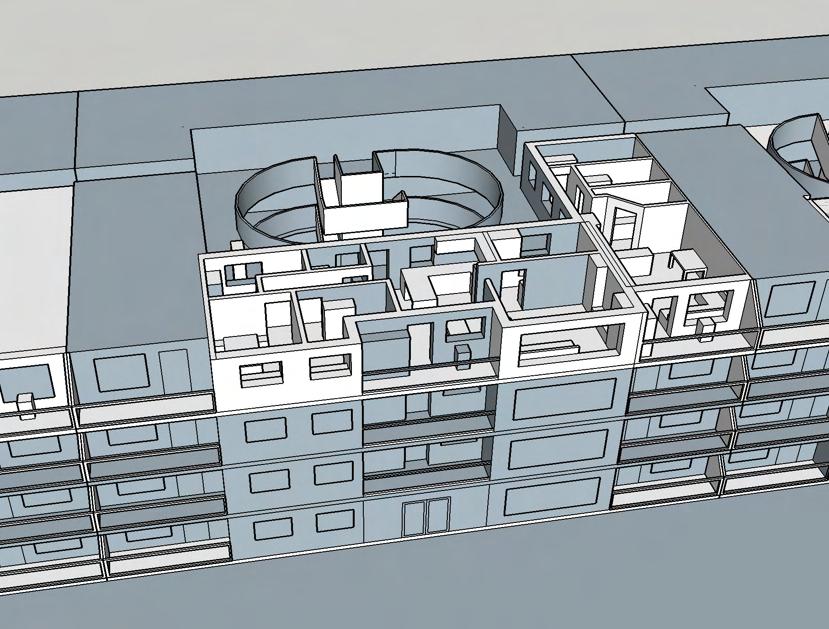

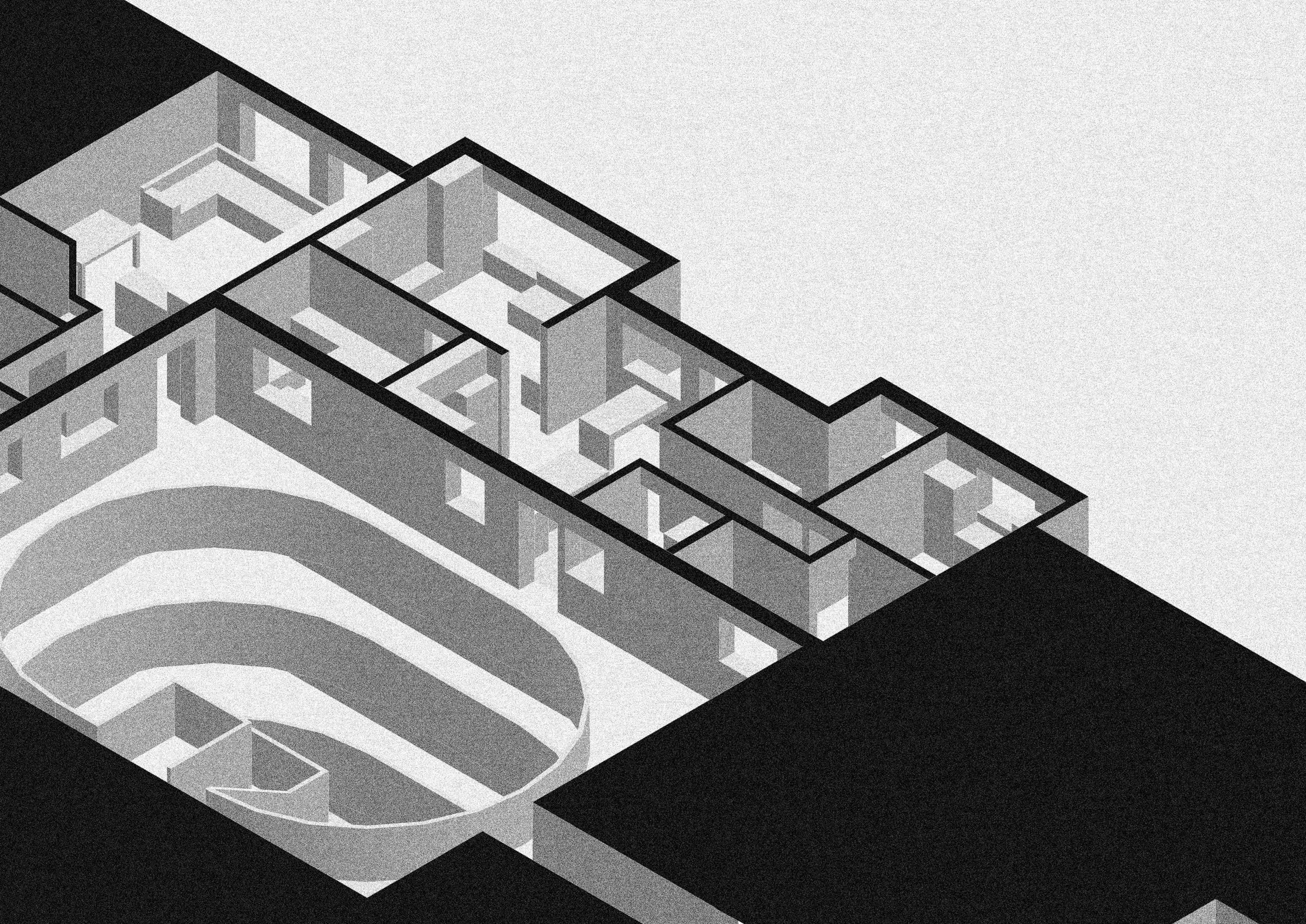

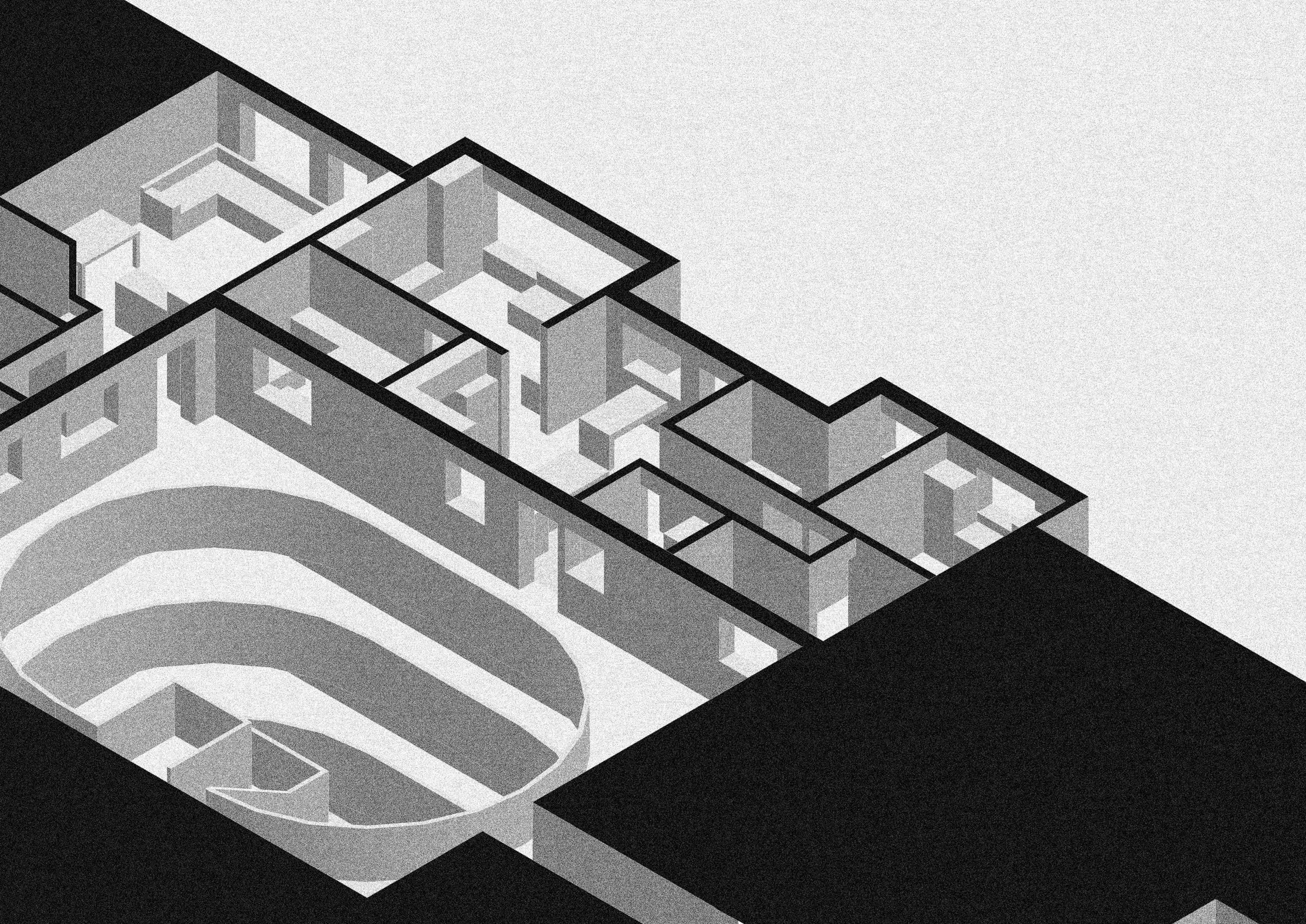

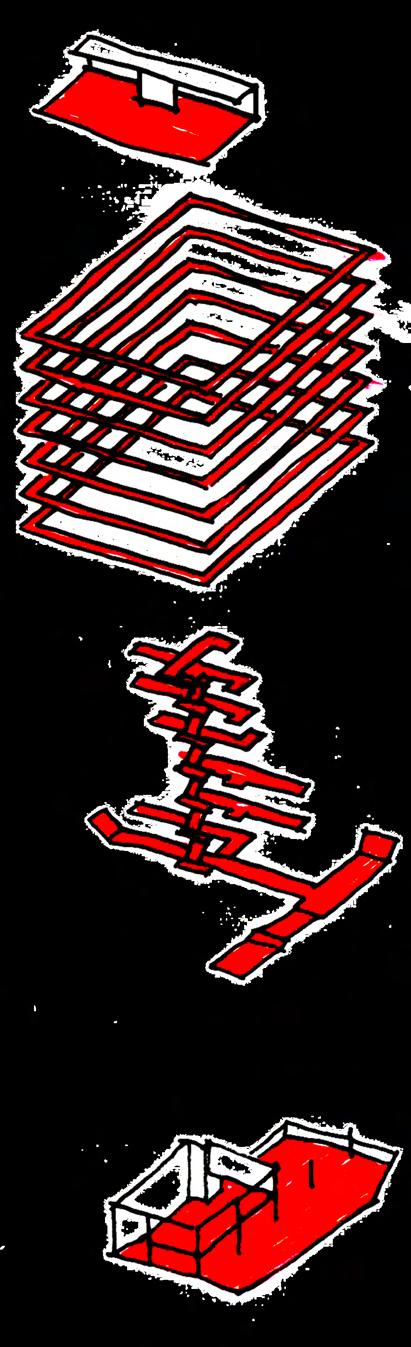

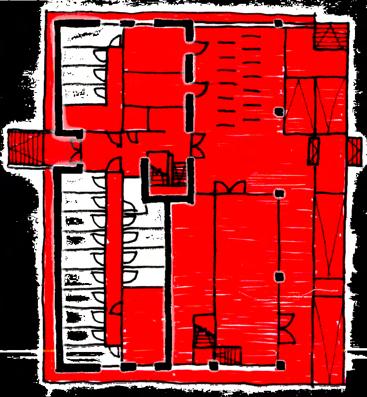

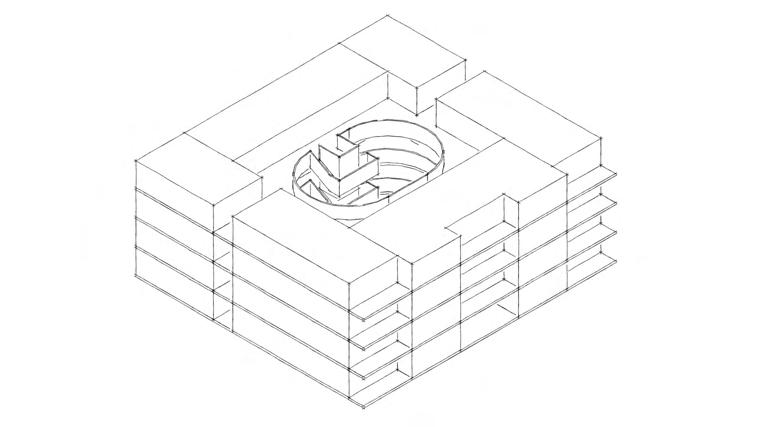

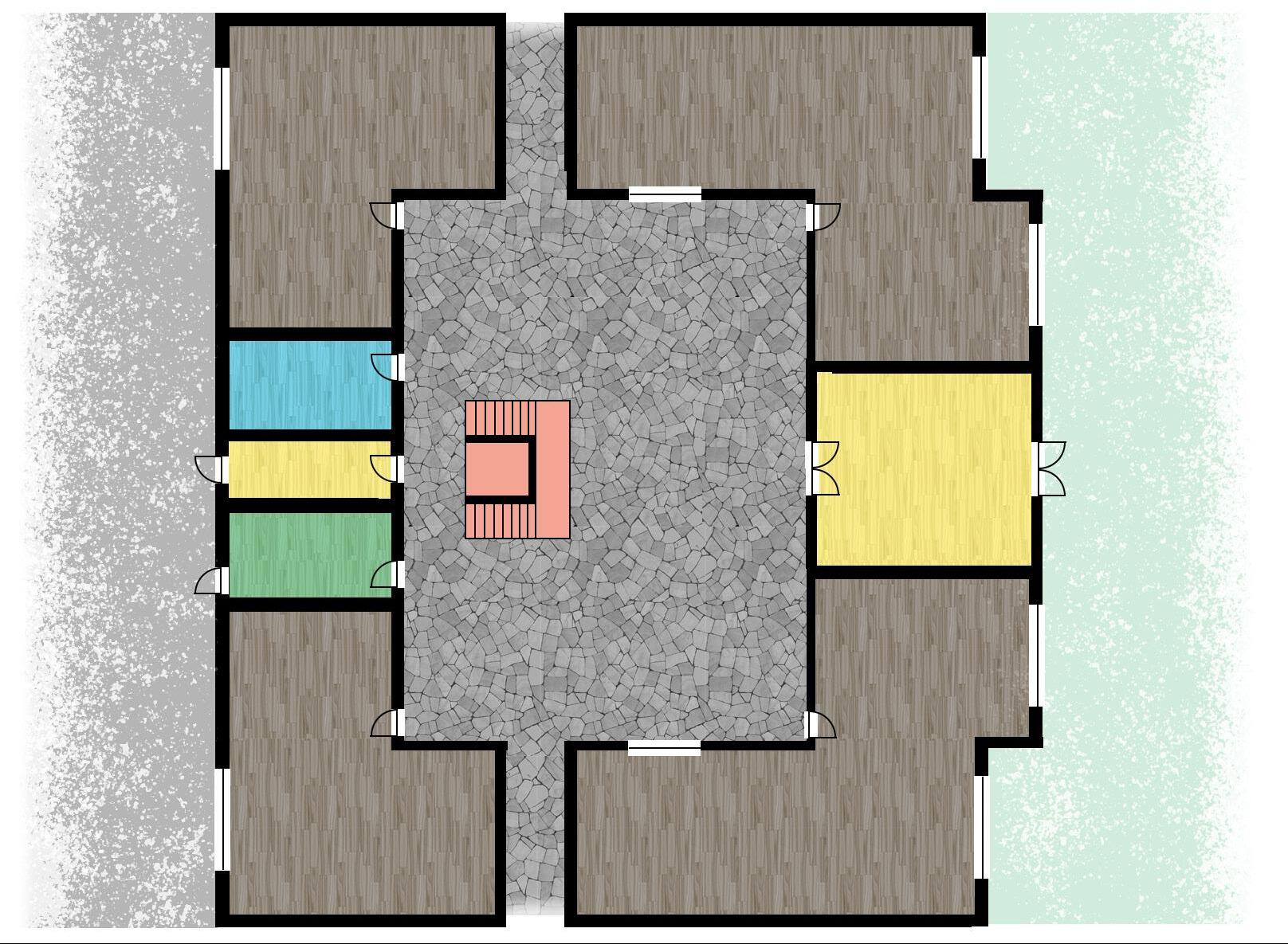

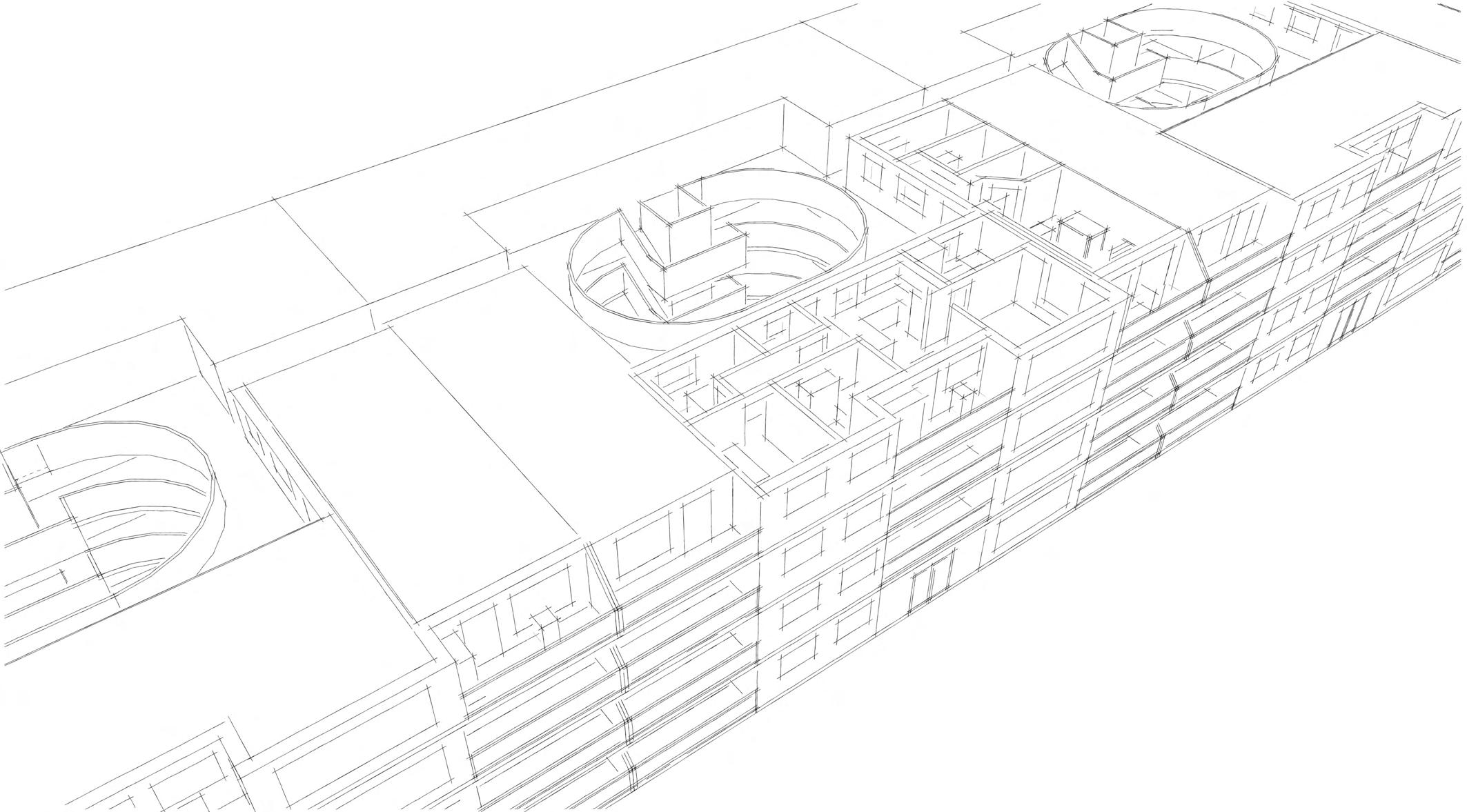

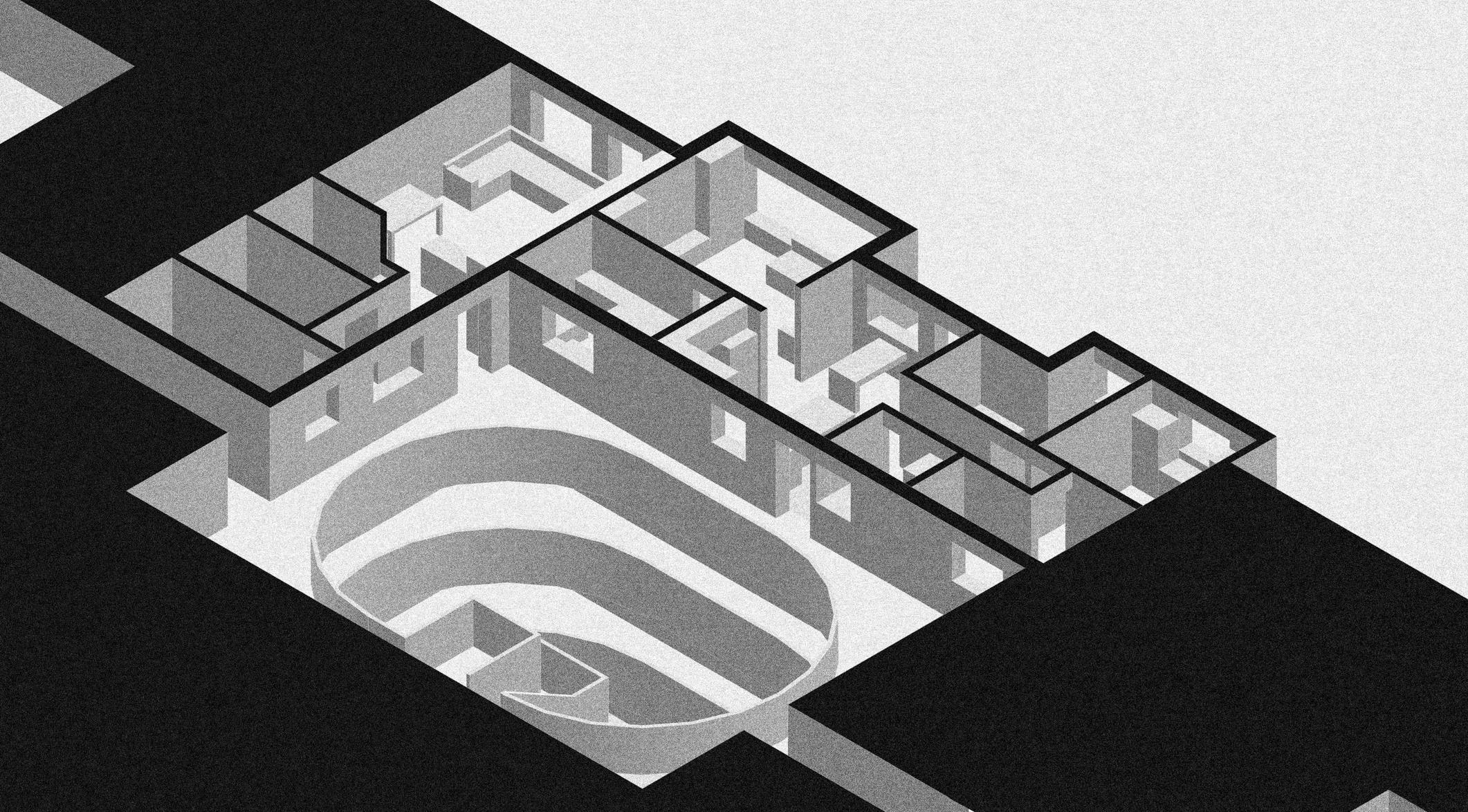

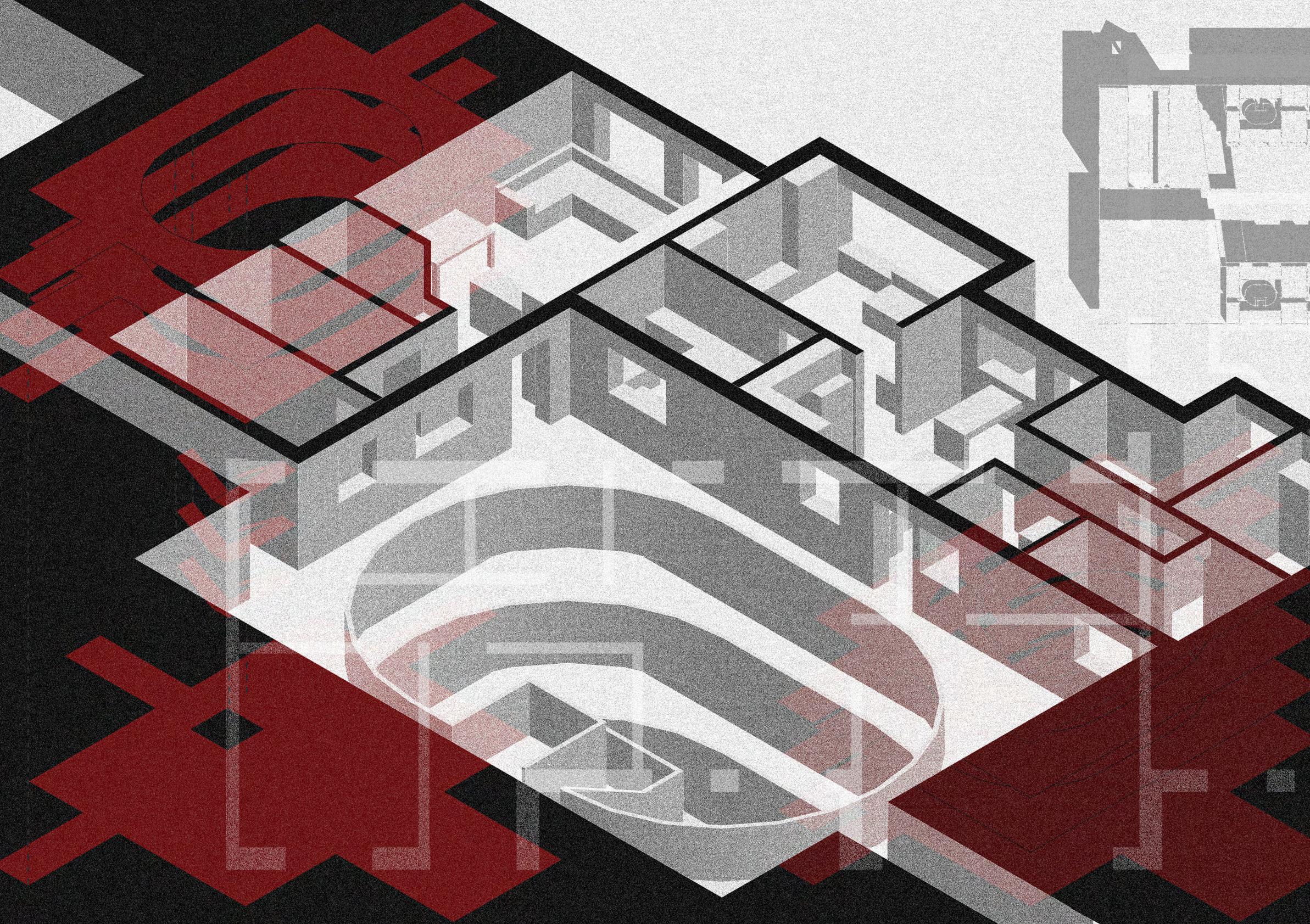

I used the spatial principles highlighted in my R50 precedent study to inform my design. It is essentially an inverted plan with the circular movement occurring in the centre of the plan and the flats situated at the edge. This allows lines of sight across the plan and between floors, facilitating conversation and play.

Similarly, the vertical circulation is open to the courtyard, which connects residents with the structure and each other. This shared central space encourages a neighbourly environment within each block. While this is encouraged across the entire development, it is more attainable at a smaller scale and this block only contains 22 households.

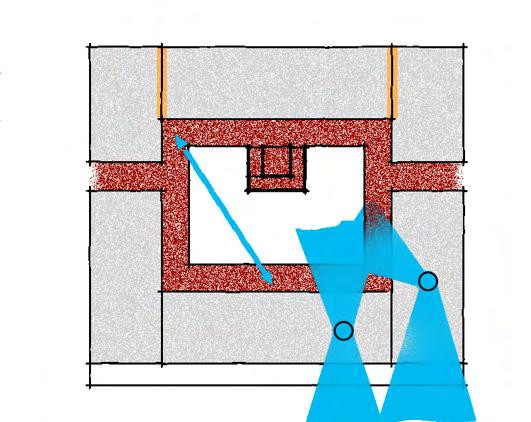

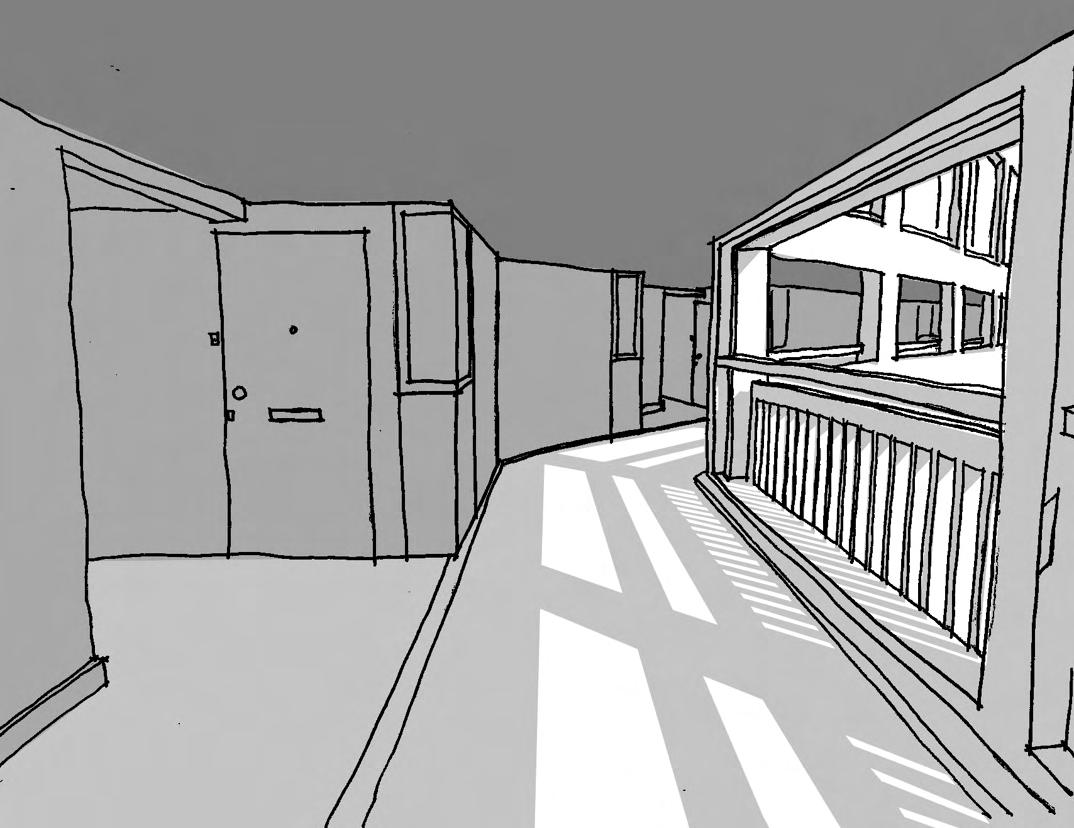

Park Hill in Sheffield has recently undergone a transformational renovation designed by Mikhail Riches. The estate is known for its “streets in the sky” - wide open-air access decks that facilitate a neighbourly environment similar to a terraced street.

The renovation included the addition of ‘porches’ to each property. This created a space that is shared by 4 households. While there are no physical separations within the space, each household claims ownership over the area in front of their door as shown above.

Circulation Space

Shared Space

Implied Private Space

The study drawing above depicts the ‘streets in the sky’ and the ‘porches’. The architectural form creates a divide between the circulation space and porch space. This is highlighted by a linear drain on the floor and more noticeably, by shading. Each deck casts a shadow on the porches below, but the decks remain lit. This draws people towards the edge and away from the more private porch spaces.

Beverdidge Mews by Peter Barber Architects is a row of eight terraced houses built in place of old garages behind a social housing block. It is a great example of infill architecture bringing desperately needed homes to a city centre. The houses are for people “who would otherwise live in overcrowded lodgings or outside the city” (Long, n.d.).

The homes range from 3 to 7 bedrooms, the largest of which has space for 11 people. Each dwelling follows a repeated plan, varying in the number of floors depending on their size.

In Barber’s signature style, each house appears to have been carved out of a solid form, rather than built up. This technique sculpts the form to allow daylight to penetrate deep into the plan. The staircase is placed in the north corner of the house below a circular roof window that guides light into the darkest corner of the plan. As shown in the daylight study below, this light can reach the ground floor around noon in the Summer.

We can also see that the house receives more daylight during the winter, increasing passive thermal gain when it is needed and reducing the risk of overheating when it is not. The roof terrace areas receive almost constant sunlight year-round, increasing their usability.

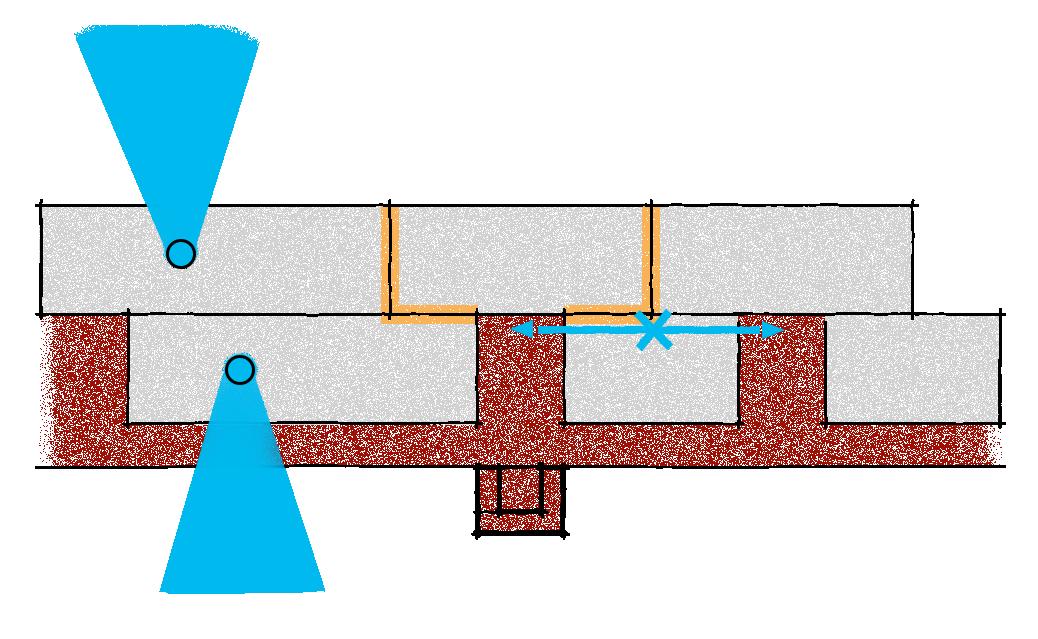

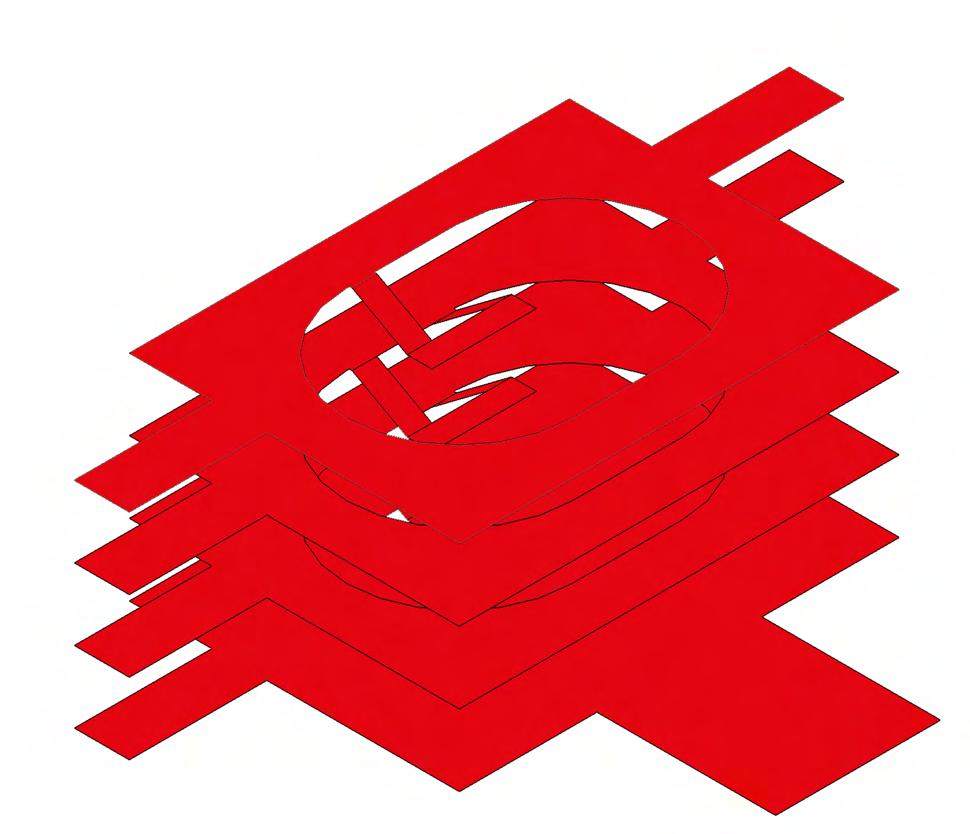

Park Hill’s ‘porches’ turned the access decks into a multifunctional space, used to meet neighbours, grow plants, and store shoes. To use this dynamic space in my scheme I would have to change the shape of the decks. To avoid reducing the internal floor plans of the flats, the decks could be extended into the courtyard.

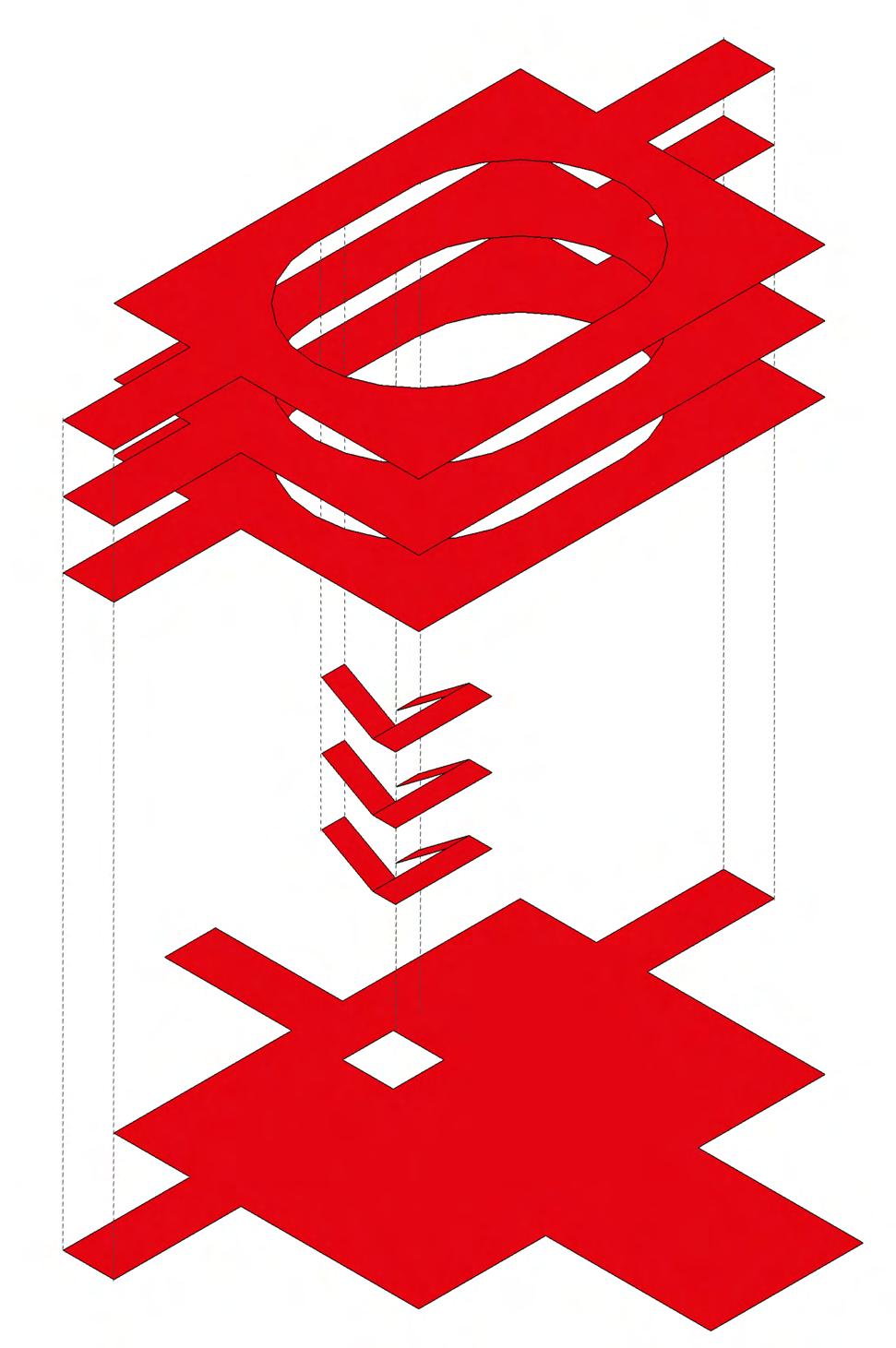

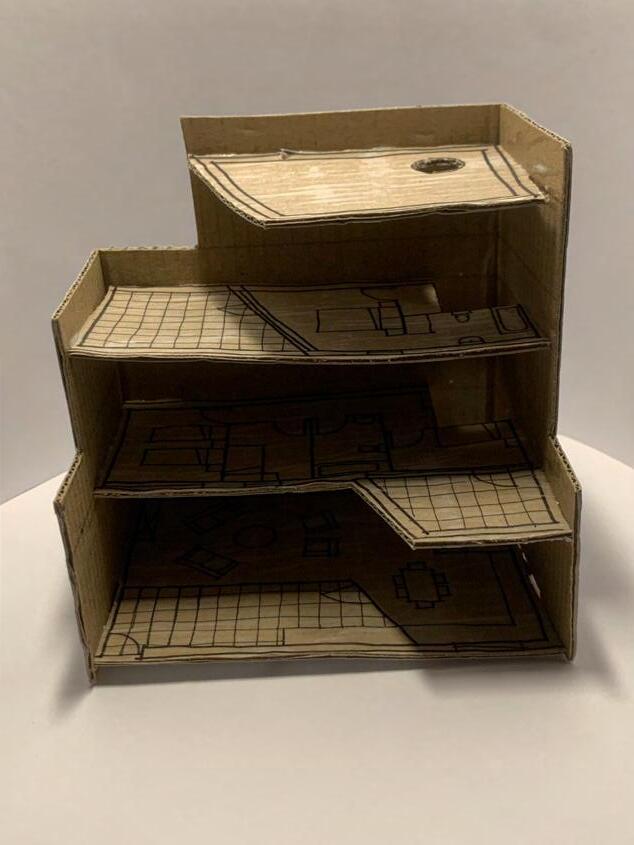

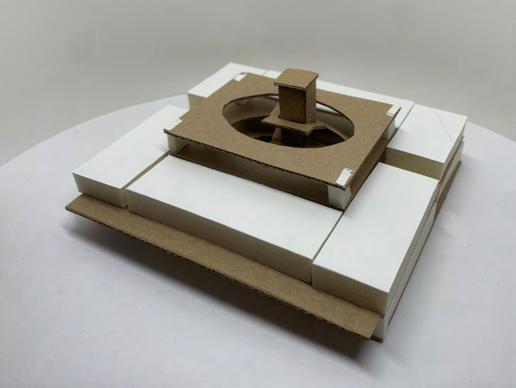

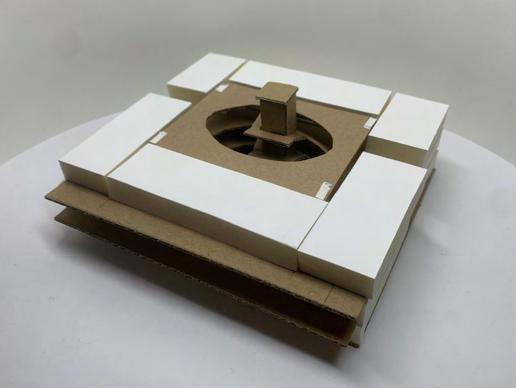

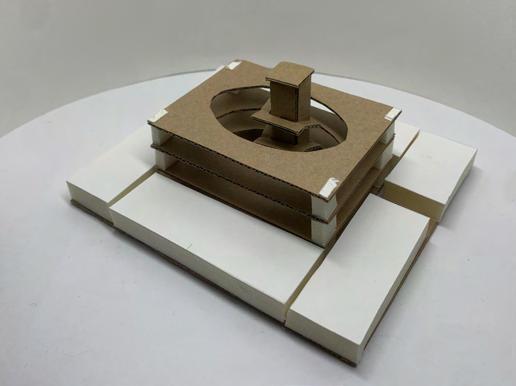

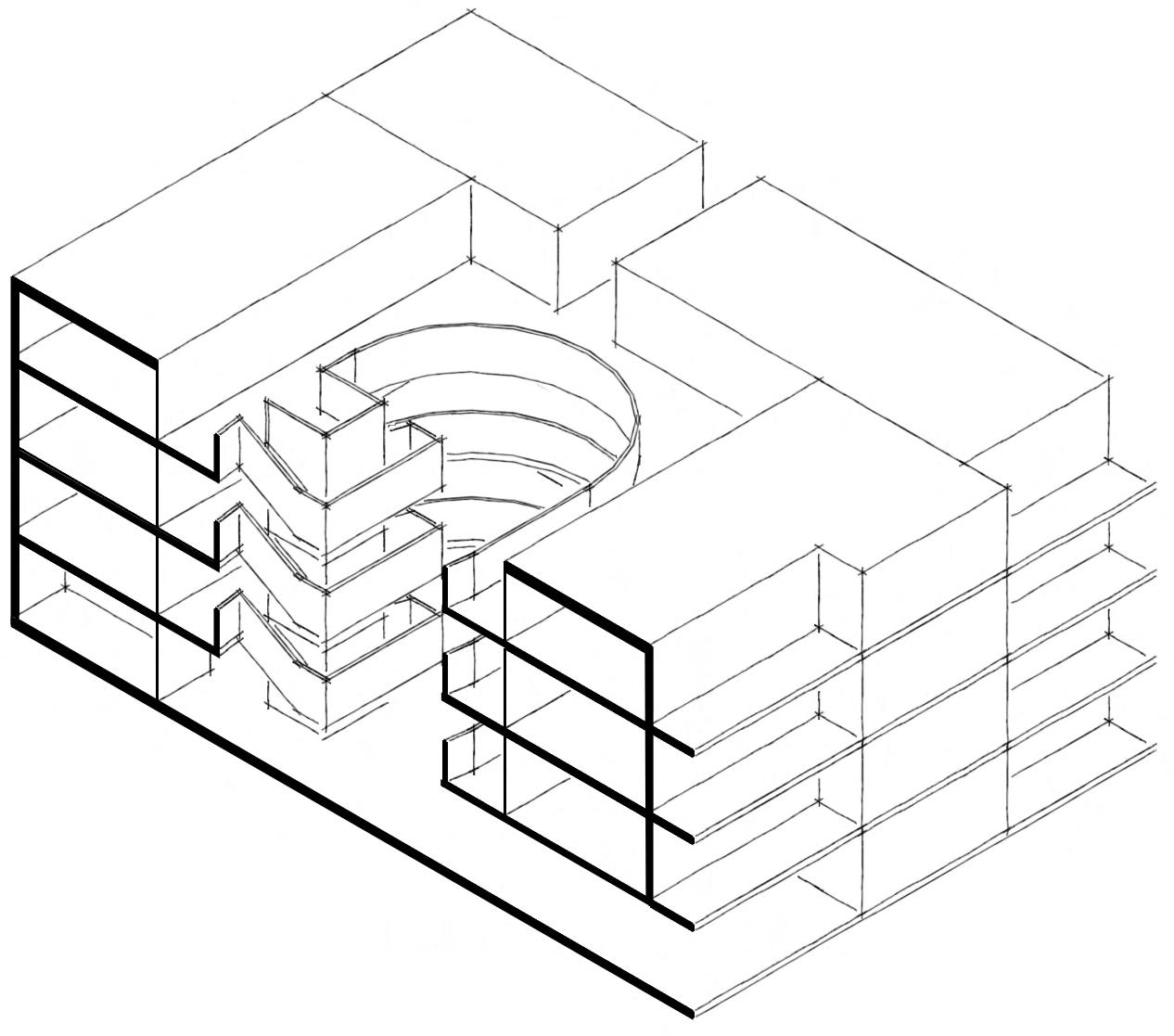

I was inspired by Barber’s attention to daylighting, so I made models to analyse how much light could enter the courtyard depending on the shape of the deck.

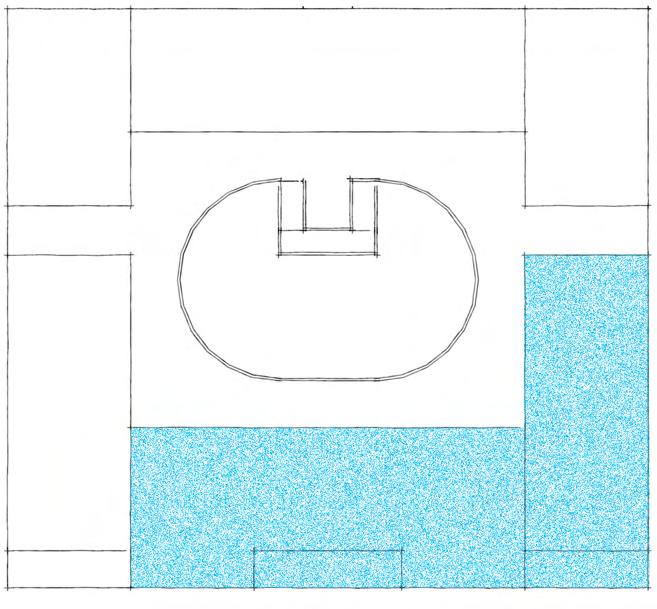

This daylight study shows that the circular courtyard is generous with deck space but lets in the least light, whereas the rectangular courtyard lets in the most light but doesn’t provide enough space. The oval is a balance of the two, allowing direct sunlight into the courtyard all year round and extending the balcony out at the corners to facilitate interaction and imply ownership. I prefer it over the octagon as the fluid shape symbolises free movement and unity.

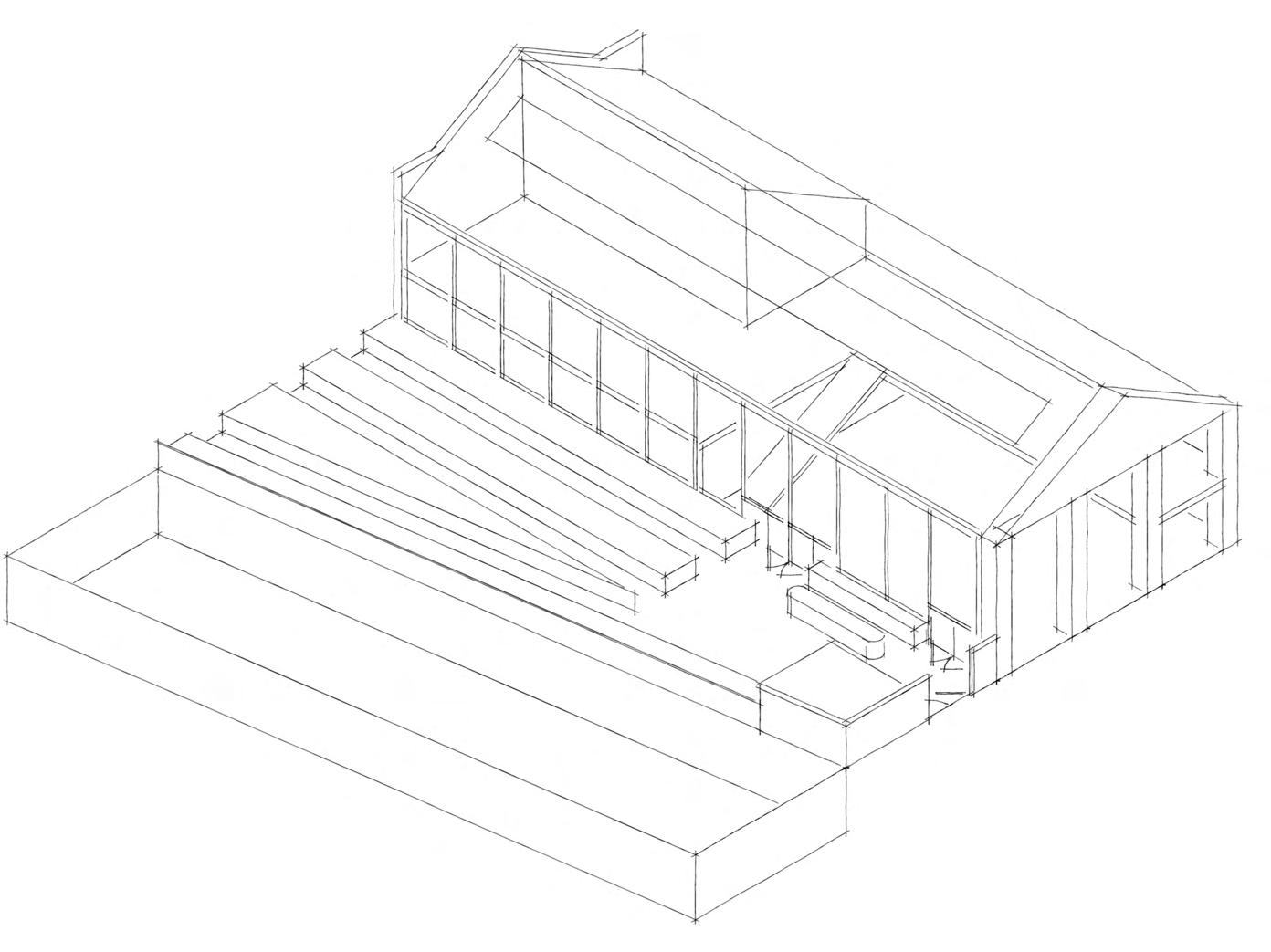

Building Massing

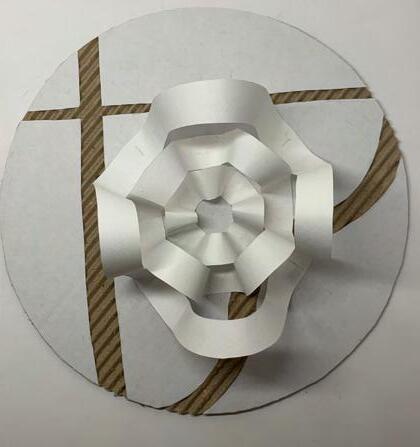

This study model at a scale of 1:200 was useful to understand the massing of each flat in relation to the block of 24. It helped me understand how the decks, balconies, and courtyard could be used.

Staircase Design

I also used this opportunity to design the central lift core and surrounding staircase. I designed it this way so it is lit by natural light during the day and is visible from the decks and courtyard which increases the sense of safety when used at night.

Choreography

Additionally, they bring an interesting twist to the choreography of how the space is used; imagine a conversation between someone on the staircase and someone on the deck across the void.

The design of this generously sized park in Manchester is inspiring. Studio Egret West cleverly allows interaction with the river without actually permitting access to the water. This is done with a combination of bridges, viewing platforms, and thoughtful use of materiality, forming a psychological connection between the park and the river bank.

The design also incorporates salvaged stone and iron found on and around the site. This reminds visitors of the industrial past of the site and the vital role the river played in Manchester’s industrialisation.

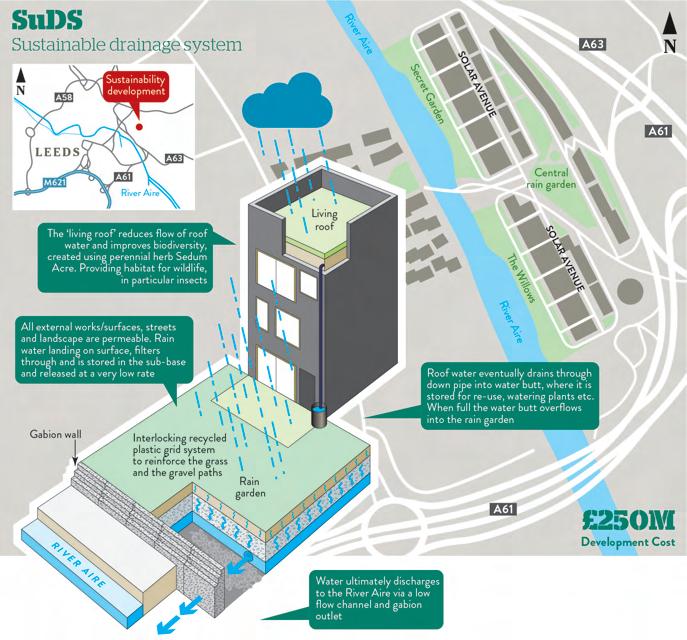

This scheme in Leeds uses careful layering of landscaping materials to slow the movement of rainwater into the river to prevent flooding.

The majority of the ground, and even the roofs, are used as a rain garden or are covered with permeable paving. It is a prime example of where sustainable urban drainage solutions are used effectively.

This experimental display demonstrates how gardens can flourish in small urban spaces. The gardening team developed a growing calendar so even a small space like this can grow all year. It includes herbs and vegetables so the garden is functional and provides a sustainable alternative food source.

Shared growing space

River Rea

Communal space

Patio

Tool storage

Kitchen

Personal storage

Maintenance store

Children’s play area

Co-working

The ground floor includes an open-plan co-working space for residents who work from home but enjoy the office environment. Using this space will give residents a chance to meet their neighbours, which could benefit them professionally and personally.

Co-growing

Between the river and the building is a vegetable garden and tool shed. This presents another opportunity for residents to spend time with their neighbours while producing home-grown, sustainable produce.

Co-eating

Inspired by R50, the garden features an outdoor kitchen with a barbecue and the building includes a large fitted kitchen with numerous appliances. These can be used to host events ranging from children’s birthday parties to neighbourhood-wide celebrations.

Co-playing

To complement the playground in the centre of the neighbourhood park, the community building contains a children’s play area, helping them and their parents meet their neighbours and providing a place for organised childcare to occur.

Co-caring

Members of the community have a responsibility to care for their neighbourhood. To assist with this, a maintenance store is accessible to all and equipped with tools and equipment that can be used for general upkeep. This will help alleviate pressure from the maintenance team on site.

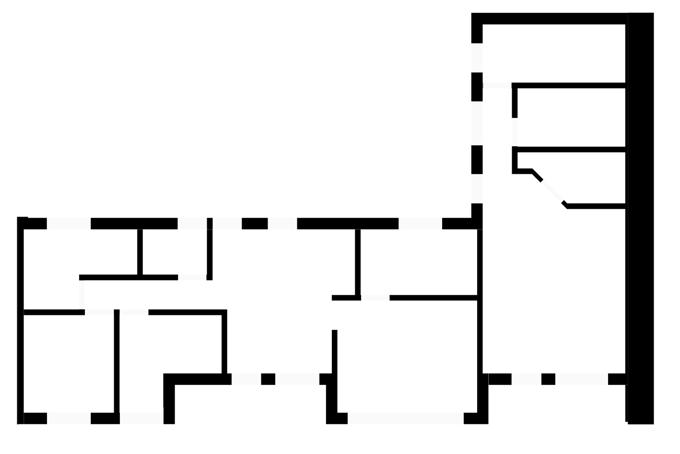

Scalability

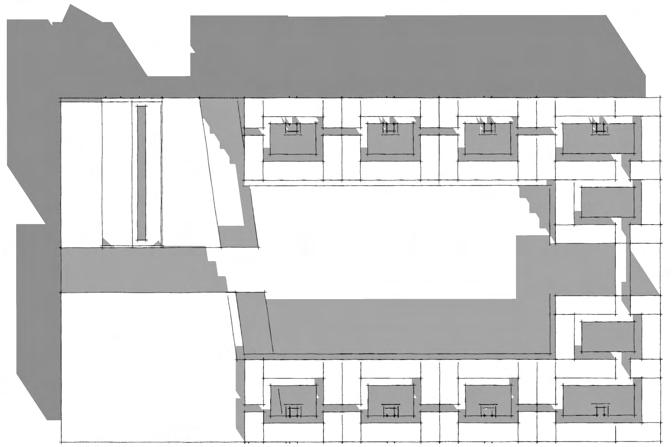

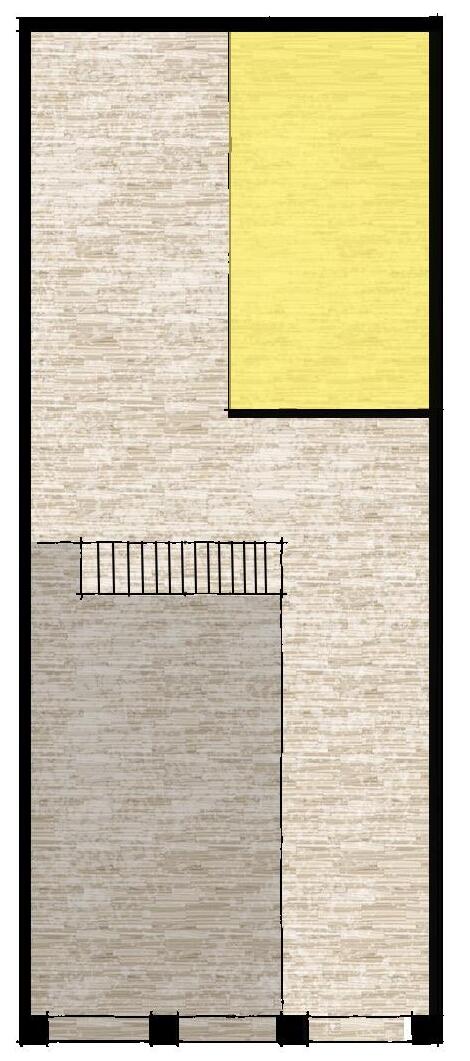

In Part 2.4 I identified the need for versatility in my design so it could be applied to similar sites. This is achieved by dividing the master plan into blocks. Any number of these blocks can be placed next to each other to form a neighbourhood with unbroken access from one side to the other. Each block functions on its own, featuring front, back, and side entrances, a courtyard, stair and lift core, 3 access decks, and recycling and laundry facilities. A small communal area is provided for the residents, encouraging a community to be formed within the block in addition to the neighbourhood as a whole. Each block contains 22 flats, ranging from one to four bedrooms.

Modern Methods of Construction

The blocks are Designed for Manufacture and Assembly. Each flat can be divided into 4 modules, each small enough to fit on a truck and be delivered to site with no special delivery measures in place. The timber-framed modules minimise the use of concrete which is limited to the foundations and elevator core.

Exterior Interactions

The block in the example is on Bradford Street which, as shown in Part 2.4, will be a pedestrianised road. The block can be accessed directly from the street through two doors for increased security. The door on the other side access the garden, accessed through the communal space.

Courtyard

Private dwellings

Lift/Stair core

Communal spaces

Laundry room

Refuse/Recycling room 0

Scale 1:100 10m

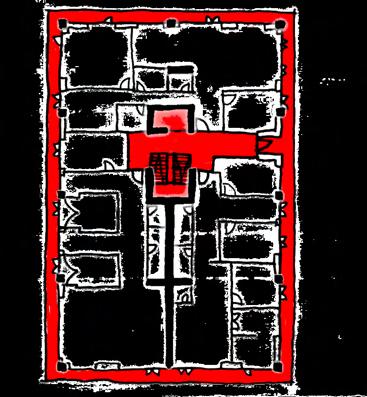

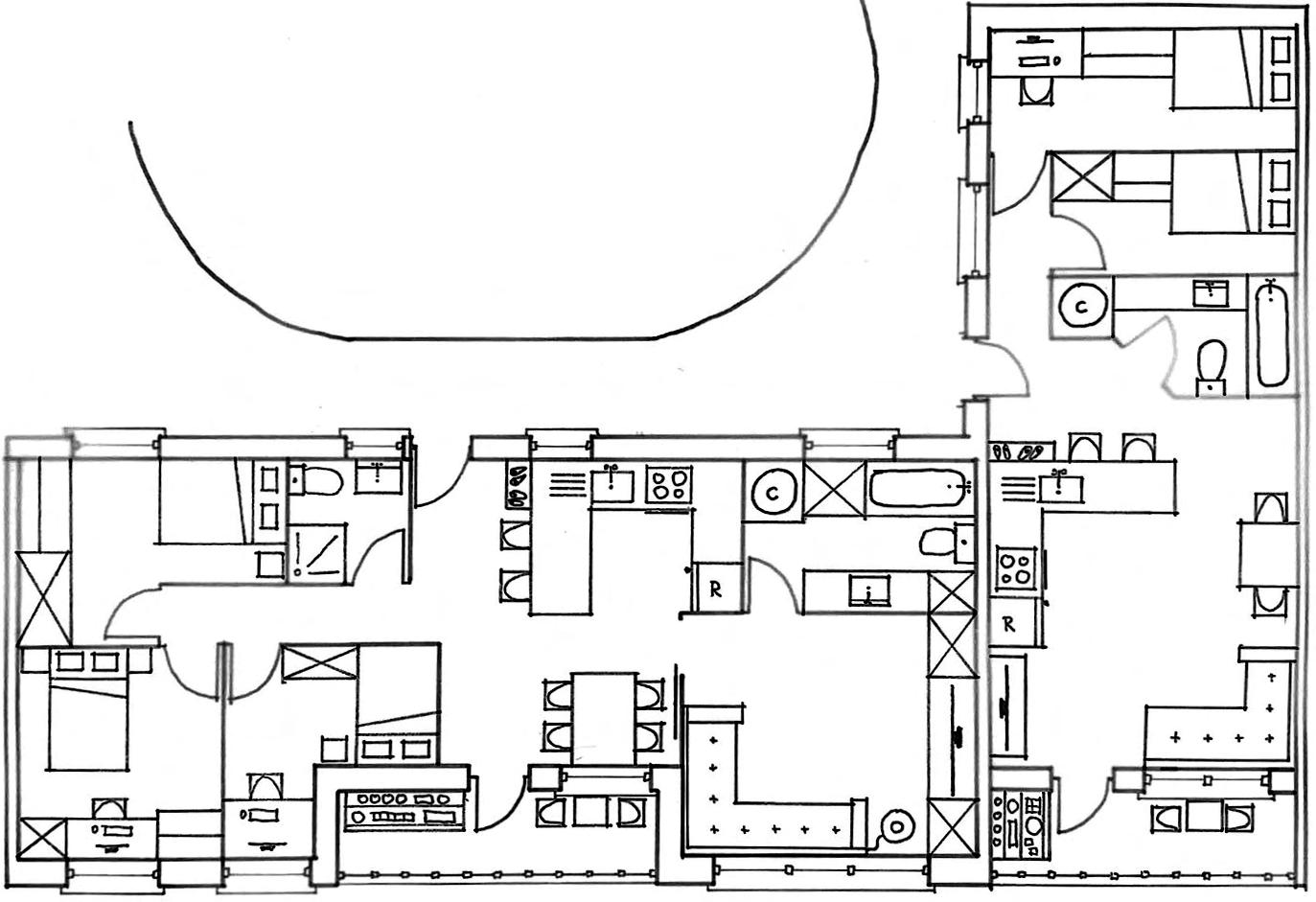

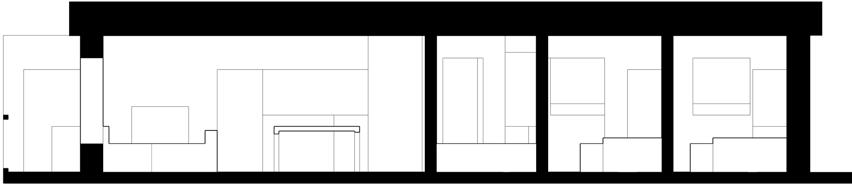

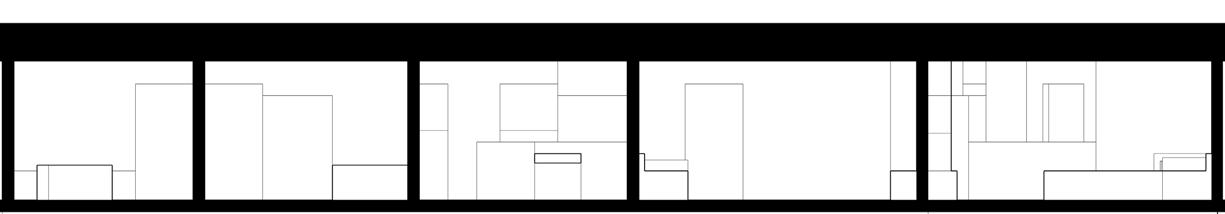

I chose to design these flats because I could use them to show the interaction between neighbours on the decks, through party-walls, and from their private balconies.

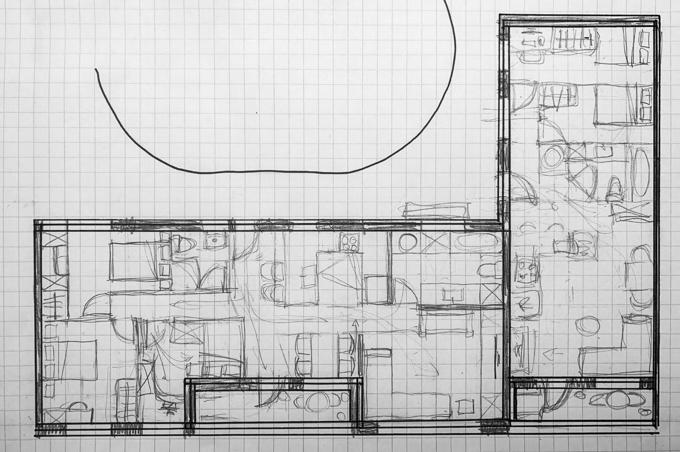

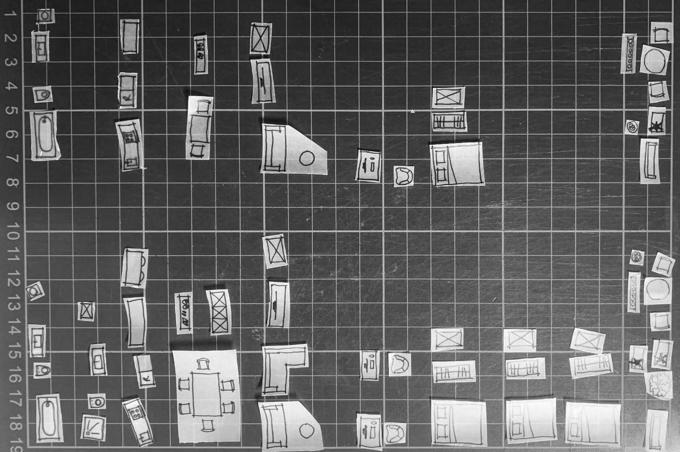

Based on my master plan, these were 2-bed and 3-bed flats so I began my design process by drawing the furniture that would be needed by each household at 1:100 and cutting them out. I used the pieces for an iterative design process, trying out numerous arrangements. My manifesto influenced my design thinking. I dedicated most of the space to communal areas within the flats, making the bedrooms smaller, with the intention of encouraging people to spend time with each other. I designed for natural light ingress which can reduce the energy bills and carbon footprint of a property.

Flats chosen to design in detail

Inspired by The Place of Houses by Charles Moore (2000) I considered the ‘Three Orders’ of machines, rooms, and dreams. While all of the pieces I had cut out could be considered as machines, I focused on the fixed appliances and kept these at the back of the plans, making space for ‘rooms’. I explored how people would move through and around the spaces with ease as well as considering lines of sight and implied thresholds. This inspired the addition of a sliding door, changing the rooms from open- to closed-plan. Finally, the balconies and access decks provide a space for ‘dreams’ facilitating views of the city and interactions with neighbours.

Birmingham City Council. (n.d.) MyBrumMap. Available at: https://maps.birmingham.gov.uk/ webapps/brum/mybrummap/ [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Harper, P. (2018, August 29). The car has been a disaster for our cities. Let’s get rid of them. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/aug/29/car-citiesvehicles-pollution-public-transport-tax [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Hurst, W. (2019) Architects Journal. Introducing RetroFirst: a new AJ campaign championing reuse in the built environment. Available at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/introducingretrofirst-a-new-aj-campaign-championing-reuse-in-the-built-environment [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Ifau. (March 2011) Arch+ Features. R50. Available at: http://www.ifau.berlin/content/1projects/26-r50/ifau-fezer-hvb-r50-archplus.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2023]

J.G, Ballard. (1975) The High Rise. J, Cape. The University of Michigan. ISBN 0-224-01168-5

Kim, J. & Dear, R. (2013). Workspace satisfaction: The privacy-communication trade-off in openplan offices. Journal of Environmental Psychology, Volume 36. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.001 [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Long, K. (n,d) HANNIBAL ROAD GARDENS. Peter Barber Architects. http://www. peterbarberarchitects.com/hannibal-road-gardens [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Mellor, T. (2020) Euro Cities. Reclaiming the streets. Available at: https://eurocities.eu/stories/ reclaiming-the-streets/ [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. (2021). English Housing Survey: headline report 2019-20. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey2019-to-2020-headline-report [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Moore, C., Allen, G. & Donlyn, L. (2000) The Place of Houses. University of California Press. California. ISBN 0520223578

White. (n.d.) Climate Innovation District masterplan. Available at: https://whitearkitekter.com/ project/climate-innovation-district-masterplan/ [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Wildevuur, S. (2018). The Impact of the Physical Environment on Mental Wellbeing. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014823 [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Beckerath, H. (2021) Models (2003-2021). Available at: https://heidevonbeckerath.com/single/ models-2003-2021?search=R50 [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Citu. (n.d.) What are sustainable urban drainage systems, and why are they important? Available at: https://citu.co.uk/citu-live/what-are-sustainable-urban-drainage-systems-and-why-are-theyimportant [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Cole, M. (2019) Future of Stormwater | Major SuDS scheme for Leeds housing. Available at: https://www.newcivilengineer.com/the-future-of/future-stormwater-major-suds-scheme-leedshousing-18-11-2019/ [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Harper, P. (Guest). (2023, January 19). Could increasing congestion on London’s roads improve transport? [Audio podcast episode]. LNDWN. Open City. [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Kim, G. & TED. How cohousing can make us happier. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=mguvTfAw4wk [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Mark, L. (2023) The Architectural Review. Park Hill Phase 2 in Sheffield, United Kingdom by Mikhail Riches. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/awards/w-awards/park-hillphase-2-in-sheffield-united-kingdom-by-mikhail-riches [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Peter Barber Architects Ltd (2023) HANNIBAL ROAD GARDENS. Available at: http://www. peterbarberarchitects.com/hannibal-road-gardens [Accessed 11 May 2023]

PLANE—SITE (2017) Building Portrait: R50, ifau und Jesko Fezer + Heide & Von Beckerath. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSaNIi8vEQ4 [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Ravenscroft, T. (2023) Ibstock Place School Refectory in Roehampton by Maccreanor Lavington The Dezeen guide to mass timber in architecture. Available at: https://www.dezeen. com/2023/03/01/dezeen-guide-mass-timber-revolution/ [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Urban Splash. (n.d.) Park Hill Sheffield. Available at: https://www.urbansplash.co.uk/ regeneration/projects/park-hill [Accessed 11 May 2023]

Wckedx. (2014) R50. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m3VMNuw3fB8 http://www.architekturclips.de/r50/ [Accessed 11 May 2023]