SINGING SONGS IN RWANDA

Sophie M Masereka

How I survived the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

Sophie M Masereka

How I survived the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

Singing songs in Rwanda.

How I survived the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

Sophie M Masereka

Forewords

A ‘Foreword’ is a short introduction to a book, usually written by someone other than the author.

There are four short ‘Forewords’ that introduce ‘Sophie’s Story’. They are written by Marigold, Marietta, and Marilene, who are Sophie’ s daughters, and Harreld, who is Sophie’s husband.

Each Foreword that follows over the next few pages tells us something about why Sophie’s Story matters to those in her family…and maybe why her Story might come to mean something to you.

My name is Marigold.

I’m 24 years old and I’m Sophie’s first-born child.

My Mum used to take me with her when she went to talk to people about her experiences in the Genocide of 1994. Early on, I always remember my Mum’s voice shaking a little bit; you could tell that she was really upset while she was delivering her testimony. Many of the details that she spoke about were new to me and I remember crying when I realised that everything she was saying had happened to her.

But hearing my Mum speak made me look at her in a whole new light: I now knew what she went through…and here she was, still standing

there, strong, having raised three children and happily married.As time went on, I could see my Mum’s strength grow. She was able to gain power from speaking – it really made her look like a superhero, a superwoman, in my eyes.

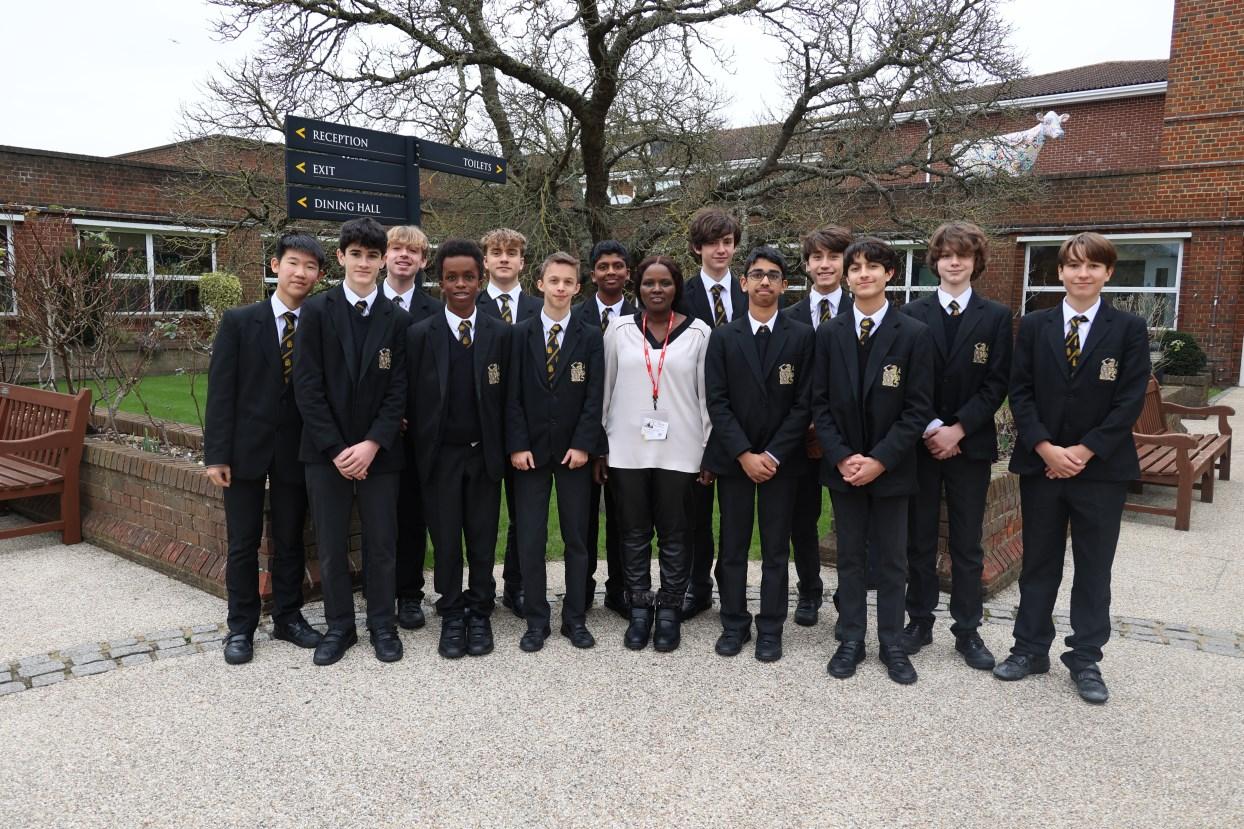

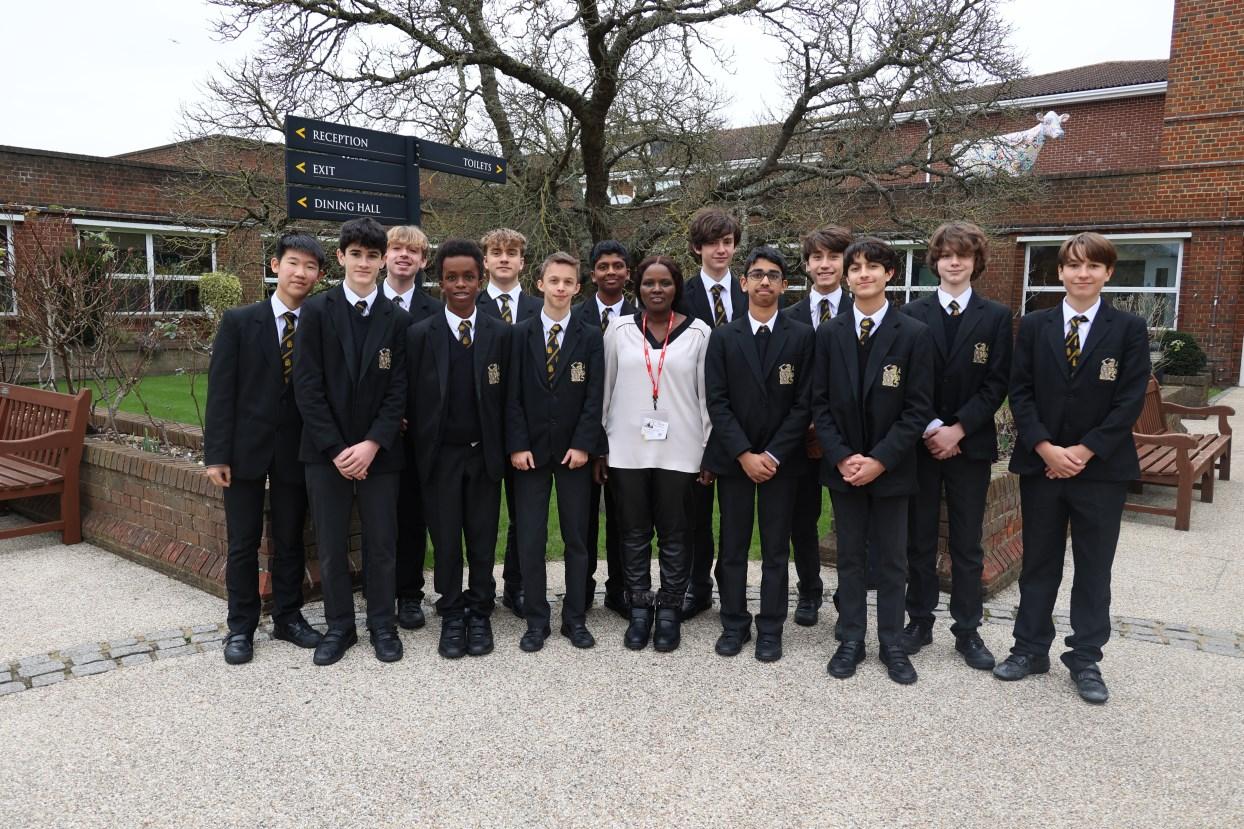

One of my favourite memories of my Mum was when she visited my School, when we were learning about the Genocide. I think I was with the whole of myYear group…and everyone knew that it was my Mum who was coming in to speak to us all. I was so proud of my Mum.

I was so proud of the fact that I was able to say ‘That’s my Mum. She went through the most terrible ordeal and yet she’s able to stand here and tell everyone.’

It felt good to have such a strong parent.

During the Genocide the attackers knew my Mum was someone studying to become a nurse. They wanted to get rid of anyone who helped those in need. But my Mum refused to give in, and she stayed strong in 1994. Now, thirty years later, my Mum is still the same. She still puts others before herself, she is still so caring and loving. She has stayed true to her nature, just like she did during the Genocide. She has resolutely defeated those who sought to kill her because of her identity. Her revenge on them is that she is still the same. She is still strong in her faith, she is still strong in her true character, the loving person she is, the generous person she is, the fact that she will use her last dollar to help someone else. It tells me and should tell everyone to

be a good person regardless. I love the fact that she doesn’t hold any hate in her heart despite the atrocities that were the worst thing I could imagine anyone could go through.

That is why I can truly say that I have the best Mum in the world… and mean it with all my being. I am so proud and glad that she was able to survive the Genocide.

My Mum is a soft, kind, sweet, gentle soul.

She has also taught me humility in my life.

Growing up in this country and having a happy childhood means that it is tempting to take life for granted. I didn’t really understand the true meaning of those words until I understood what my Mum went through during her own childhood. Despite everything she experienced she still put a roof over our heads, put warm food in our stomachs and covered us in warm blankets at nighttime.All that taught me to be humble and grateful. I love my Mum for that.

My Mum has taught me so much. The fact that she survived a Genocide teaches me so many things. Because of her experiences she teaches me to help others to not hate others, to be kind, to stay true to your character, to listen more than to speak…I could go on. I am so grateful and glad to have her as a parent.

My Mum, a survivor of a terrible Genocide, has taught me so much. I

hope that, by reading her story, you too can learn the lessons that I have.

My name is Marietta.

I’m 19 years old. I am Sophie’s second daughter. I remember when I was young, there was a photograph that we kept around our house. It had a blue background and showed an older man, two boys and a younger girl. My Mum told us that it was her dad, her two younger brothers and her niece. I remember her describing each of their characters – how one of her brothers was a really happy, jokey, goofy guy who always made my mum laugh.Another brother was just really nice…and he resembled my older sister because he had a bigger forehead! The picture of my Grandad – that is the only picture that I have ever seen of him. Right from the first time I saw it my Mum would always say how much he would have loved us and how he would have given each of us names based on how we looked or our characters that he saw. That was the earliest memory I had about my Mum and the Genocide. I think that I asked her who those people were, or she sat me and my sisters down to tell us who those people were. When I was young, I didn’t understand the extent of it. I just knew she lost people and that she could have died…. but I started to learn more when I attended her speeches. Every time I see her speak; I always

learn something new.

It has been so impactful and inspirational to me.

I see my Mum as the strongest woman I know and who I will ever know. She went through that. If that was someone else, they wouldn’t be where my Mum is: happy with a family, full of life…and even comfortable to talk about what she has been through. It has made me look up to my Mum so much to see the strength that she has in her, and I really adore that.

The scars of the Genocide still remain painful for my Mum, though. Certain things triggered her when we were growing up. I remember when I got army print jeans, which were a trend at the time. My Mum got very stressed seeing me wearing those jeans and I never really understood. I said ‘Mummy, it is just fashion, it is nothing…’but she never told me why it upset her. Later, my dad explained that those jeans triggered memories of the soldiers who were trying to kill her and her family during the Genocide.

Mum also gets anxious around Bonfire Night, in November each year. When we can hear all the fireworks going off, you can tell that my mum is scared. She never says anything, but you can tell that she is hearing noises that take her back to the Genocide and all the sounds of shooting and explosions.

It is so sad to see her like that.

So, growing up we are very aware that Mum’s memories of the Genocide are still there and still trouble her. It is because we love her so much that we don’t like to see her distressed and we come up with ways to help her feel better.

The month ofApril is a very, very sensitive time for my Mum. The anniversary of the start of the Genocide is a very dark time in our house. We know that, even though we help her recall cherished memories of her family, there will also be specific days inApril that are particularly painful for her. The trauma never totally leaves her.

I also had a traumatic time in my life when I got hit by a car when I was thirteen. It’s not the same story as my Mum’s, but I see some similarities. I see the scars that she has from the Genocide, and I have some too from my accident. For a time, I was very, very angry - angry that I had to go through the accident and the aftermath. But my Mum’s survival and how she deals with the pain really inspired me as a young girl to learn how to accept and grow from what you have come from. My Mum’s example of coming through the other side has taught me to be a stronger person. She is the strongest person that I know. It is a blessing to have her. She is such a strong woman, to be able to go around London to tell her story and teach people about the Genocide. I am so empowered by her and proud of her and who she is.

My name is Marilene.

I am 17 years old.

I am Sophie’s youngest daughter.

It took time for me to realise the magnitude of my Mum’s experiences in surviving the Genocide in 1994.

I remember when in Year 6, or even younger, my mum went to speak at my older sister’s secondary school. She asked me to go along and sing with her. Being in that room helped me to sit down and actually focus and listen…and that was the first time that I actually understood what had happened to my Mum during the Genocide. I didn’t really understand the true gravity of it until years later.

Gradually, it dawned on me. I began to realise that my Mum’s experiences were something different and significant. When I heard that my Mum had been invited to speak in Sweden…and then that the Queen of England had asked her to attend a Garden party at Buckingham Palace it made me think that my Mum’s life had not been the same as everyone else’s.

One of the biggest things that my Mum’s story reveals to me is how strong her faith is. She speaks about how she was able to cope and survive the Genocide because she had this really unbreakable spirituality and belief in God. Her faith is extraordinary. It was put to the ultimate test, and she was still able to stand strong. That gives me inspiration

and the belief that I can stand strong too!

Just to be able to point out, ‘that is my mum’, is a very proud moment for me. Her journey from Rwanda to India where she met my dad, made me look at their love in a different way. It was almost like my dad was a saviour for my mum. She had just come from an incredibly tormenting experience, and she was able to find love. The Genocide had left her feeling that she had no future and no desire to have children or get married. When you start to see death all around you start to see the world as an evil place. It isn’t a place into which you want to introduce children. The fact that she was able to find my dad and find peace and love is amazing. That’s probably one of my favourite parts of her story because it feels like a new start was given to her by my dad. Her experience of finding her soulmate is quite a beautiful story. Every time that I’m with my mum, her story rings in my head. Even when I’m annoyed with her, I just remember how strong she is. I think to myself, ‘remember who you are talking to!’. She is such a resilient, powerful, sympathetic woman. She has never given up. Ever.

There’s one last thing.

I don’t think that I’ve told anyone this.

I’d love to have a career as an actor…and it would be my dream to write and produce and direct a film of my mother’s story. I feel that her story specifically has something to say. It is such a moving story; it is such a powerful story of a powerful woman. I think that it would be beautiful to not just read on paper but to watch on film.

That is how inspired I am by her story. I hope that you are too.

My name is Harreld.

I am Sophie’s husband.

Next year will be twenty-five years since we got married. Through this long period, we have talked a lot about the Genocide. Her story has changed me as a person.

I have been at different commemorations both here in Britain and abroad.At all of them I hear stories of people who survived. Here, though, I am talking about one person.

One survivor.

Sophie.

Sophie has told me all about how she survived and what she went through. She has taken me to all the spots where she could have been killed but survived. She has also taken me to memorial sites all over Rwanda where I have seen things that I cannot describe. When you go there and see the bones and the skulls it takes your heart and sinks it to the bottom of the abyss. Seeing these things, hearing about what happened in 1994 from Sophie, has left scars and caused me to have nightmares about the killing and where my family is being attacked and I try to defend them.

I felt angry when I first visited Rwanda with Sophie. When she took me to her village and I could see the destruction that took place in the

land of my father-in-law, I felt angry. I was surprised when I saw that the people who had a hand in all this destruction were the neighbours, still walking freely and openly in the village.

My wife shook their hands.

She had brought beans, soap, cooking oil and lots of other supplies from the city and she gave it to them. I thought to myself, ‘What are you doing, Sophie?!’, these are the people who committed so many atrocities against your family. I was angry.

Sophie does the same every time we visit Rwanda, every two years. I ask myself how a person who was hurt so much can still do good things for the people who committed such crimes against her family. That has remained a question for me…but it has played a part in changing me from the man I was twenty-four years ago. The way that I have looked at how Rwandans have sailed through to recovery with a spirit of reconciliation has changed me and made me a better man, I think. I now look at a life without enemies, I’ve learned that it is not good to keep enemies. I’ve learned how to live alongside people who are not like me and who may not like me. I have become resilient and forged a way of living with them. By rubbing shoulders with people who ought to be your enemy it somehow brings a healing to you.

All this I have learned through the story of the Genocide that Sophie has taught me. So, Sophie’s story has changed me forever. Maybe reading her story will change you too.

Preface

Hello. My name is Sophie.

I hope that you never have memories like mine. I don’t like remembering what happened to me in 1994.

Yet nearly every night I do.

For fifteen years, I did not want to speak about my memories. I did not want to tell anyone about what happened to me in the hundred days in that spring and summer. 1994 was the year of a World Cup football tournament. It was the year that Nelson Mandela miraculously became President of South Africa. I had my own miracle that year. I survived a Genocide.

You may not have heard of the word ‘Genocide’. I certainly hadn’t when I was a young person in 1994. But I was engulfed in something so terrible that the world called it ‘Genocide’ (not that the world did anything beyond that to help me or others like me).

‘Genocide’ is the word that lawyers and judges use to describe a crime so terrible that it has been called ‘the crime of crimes. It is used to explain what happens when one group of people so hates another group that they try to destroy them.

Yes, you heard that right.

Destroy them.

Annihilate them.

Erase all trace of them…so that it would be as if they had never existed. Kill every single man, woman and child who is part of that group.

You may have heard of the Holocaust. That was when the Nazis and their collaborators tried to annihilate every single Jewish person under the cover of the Second World War. That was Genocide.

Well, in my country of Rwanda, in 1994, it occurred again. I was a part of the social group called ‘Tutsis’, who were targeted for annihilation. Not because of anything that I, or other Tutsis had done…but because of who we were. We were to be destroyed simply because of our identity. What happened in 1994, in Rwanda, has been called the ‘Genocide against the Tutsis’ because extremists intended to wipe out every Tutsi man, woman and child that they found.

Can you imagine that? In a way, I hope not.

So, what made me write a book about something so terrible? And why should you read a book about such a dreadful time?

Well, I decided to write this book in the hope that at least one person,

young or old, might learn about what happened to me. If we are ever to prevent such terrible things from happening again then we need to know how they happen and what causes them. So, if you know more about my story and what happened in Rwanda, then maybe you will help to stop a Genocide from happening in the future.

I also hope that my story can help you in another way. If you face troubles or problems, please know that I once did too. If you feel alone and that everyone is against you, then I can identify with you. It happened to me. And I survived. I hope my story can help anyone who is suffering in some way. I hope that my story might help you understand that no matter how bad things get, you are not alone. When all seems lost…keep going.

Just after the Genocide I thought that no one would be interested in my story. During the killing in 1994 I was hated. Afterwards I found it difficult to convince myself that I should tell anyone who I was and what I had been through. I thought that because I had been hated once then I would be hated for evermore. So, I decided that I should bury my story and hide my past.

Today, though, I feel differently. I choose to share my experiences without any fear, and hope that people might benefit from reading my story. I talk about what happened to me in what has become known as the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, as much as I can. I want my story to be heard by as many people who will listen. But if you are the only person who reads about my experiences and understands them, then

that will be enough.

Like other survivors, I am alive not because I was any better than those who died. I was lucky. Now, I try to use my survival to give a voice to those who can no longer speak. Those of us who survived are there for those who were murdered in 1994.

I’ve had the honour of speaking to Kings, Princes, Prime Ministers, and government officials. I’ve had the chance to tell my story in grand venues and as part of prestigious ceremonies. Most importantly, I have had the privilege of explaining what happened to me to young people in schools, in churches, in newspapers, and on BBC radio and television. It has been that experience that led to this book that you are reading now. I’ve heard from teachers that they would like their students to understand what happened in Rwanda in 1994. As hard as I work to speak at as many schools as I can, I can’t do enough. Hopefully, my book might reach some more of you, some who I haven’t been able to meet in person yet.

As you read my story, I ask you to bear with me. I tell it as it was. Some parts of the story may sound impossible, but that is how it all happened. I recount events as I saw them.

During the Genocide, I lost my dad and my Grandad who I loved so much. My brothers, Charles, Danis and Jean Paul were killed. My sister, Marceline, was murdered. My dear cousins, Ephraim, Gerard, my baby nephew Emmanuel died with her mum who was my sister-inlaw, Rachel. All of them couldn’t grow up to live their lives.

I lost my nieces, Odette and Nayira. My uncle, Chadrack Nzabamwita, and his wife Esther, and her family were murdered. My mum’s brothers, Uncle Muvunyi and Uncle Gerard perished too. Her cousin, Vincent and his brother were all killed. My Auntie Lidia was murdered along with her baby and her husband Pastor Jerome Kalisa. The parents of Chadrack Kamanzi, my brother in law who saved my siblings, were also murdered. My sister in law, Vestine, the wife of my brother Charleston did not survive. Her parents and her brothers and sisters were also killed. These people mattered so much to me.

So many neighbours and family friends were cut down during the Genocide too: Amon Iyamuremye and family, Amon Rugerinyange’s family, Mukamurangwa, Murangwa, Murwanashya, Elisha, and their baby brothers that I loved so much, Rurinda and the family, Umurisa's family, Musoni’s family, the Ntaganiras, Semadimbas, the Sezisonis, Stephany, Mother-in-Law (Antonia), my classmates Captoline, Irene, Grace and Bosco. My teacher Oswald (who taught us maths and was in charge of our school choir too) and his beautiful wife, Antoinette…

All gone and murdered. The list is endless.

And that list is just those I can remember. And that is just my memory. I am just one person. If you asked everyone who survived to tell you the names of all those they lost, can you imagine how long it would take to write such a list?

Introduction

I want to tell you what happened to me when I was a teenager.

It might be the same sort of age you are now or have memories of being. Teenage years are supposed to be a time of fun and laughter with friends and family.Atime of discovery.Atime to dream.

My memories of that period of time are quite different. The things I discovered about people and the dreams I had aren’t those that normal teenagers are supposed to have…and that is why I want to tell you about them. But first of all, let me ask you about singing. Yes, you heard that right.

Singing. Do you like singing? Some do, some don’t. Me? I love it.Always have.

Singing has long been a tradition in my family. My Mum and Dad told me that, in our family, when they got married, they would sing together and then perform in churches. Then, when they had children, the little ones would learn the songs and join the family ‘choir’.

Growing up I remember singing with my family all the time.At home, in the street, at my Grandparents’house, singing with neighbours, singing to the songs on the radio, singing in Church, singing along at concerts we went to, singing with my brothers and sisters on the way to school. Until, that is,April 1994.

Part One: Before

These are the memories that I have from my life in Rwanda before the Genocide. You’ll forgive me if all I can do is present you with just a few fragments.

I haven’t got any pictures from my early years to show you. We didn’t have a camera in our family, we weren’t rich or privileged. There aren’t any pictures of our family celebrating each other’s birthdays or us playing in our garden. The few we had were destroyed in our house during the Genocide...by those who came to kill us.

All I have are my memories of those times.

Our house in the village

I went to Primary School in the south of Rwanda, in the countryside. Most of the country that I grew up in was countryside. Rwanda is famous for its fabulous highlands and is nicknamed ‘The Land of the Thousand Hills’. But there weren’t many hills where we lived. Most of those thousand hills must be in the north of the country because it was pretty flat in our area. Our village was on a plain, as I might have learned in my Geography lessons. Neither did we have winter in our village. Summers were hot and sunny and then came the rainy season.

If it was colder all you needed was a light jacket to stay warm. If you asked me what ‘snow’was, whilst I was in Year 5, I wouldn’t have known what you were talking about.

My Dad had built the house that we lived in.Actually, it was two

houses connected together, and another beside it served as a kitchen and storerooms. It was a good, sturdy house that had solid walls and a roof of thick corrugated iron sheets.

The beginning of my day in Year 5

My Mum and Dad worked in the capital city called Kigali which was a bit of a journey from our home. So, they would leave us kids at home in the village from time to time. They wouldn’t leave us on our own, though. Every day one of our kind neighbours, Minani, stayed with us at our house to help us prepare our lunch and evening meals, after Mum and Dad had left for Kigali. Then after eating our dinner, another neighbour, Kayijamahe, would come and look after us until morning. Before we went to sleep Kayijamahe would tell us funny stories. My Dad trusted Kayijamahe. Dad told us that he would look after us, if anything happened in the village whilst he was away in Kigali.

We’d wake up by ourselves. We had no phones or watches to wake us, but we did have a radio. Radios were everywhere in Rwanda, and we knew it was time to get up when the radio started really early in the morning at 5am. But the radio that woke us wasn’t even our own. That belonged to our neighbour Ugirashebuja. Without fail, every day, he would turn it on at 5am. When we heard his radio, we knew that it was time to get up and get busy eating the food that Minani had helped us prepare the previous day or the porridge that we made ourselves. Then we would pack our school bags and get going to school.

The man in his garden and his radio

Like we didn’t have a watch or a phone to wake us, so we didn’t have a watch to help us tell the time on our walk to school…but we were never late.Again, we had Ugirashebuja’s radio to thank for that. We’d walk past his house every day as he listened whilst he worked in his garden. Every morning, he would dig, dig, dig. He’d dig with a spade and would use his machete (a big knife) to cut roots and chop thick stalks (lots of people in the village worked in their gardens like that). His radio would be on so loud that the whole village would listen as he worked. When we were walking through the village to our school, we would listen to it too and listen out for the time so that we wouldn’t be late.As we went along more and more of our friends would join us and we would walk in a group. Singing the songs that we heard on the radio as we went along. My house was near the road. We would pass people on the road as we all walked to school. Every day, thanks to the man with his radio, we arrived at eight o’clock. Right on time.

When we got to school, we’d line up on our playground, in two groups: one line for girls and another for boys, in front of the classroom. We never mixed. Then we would go inside, ready for our lessons.

The teacher and his bicycle

My teacher, Mr Kalima, looked kind to everyone who saw him. He was an old man, probably about as old as my dad. I can’t forget him, even today. He was a very tall man who used to live far away from the school, in a place called Gasoro. He used to cycle to school. Every

day, we would see him coming up the road looking like a wise giraffe trying to ride a bike. His bicycle was so small that his knees would nearly reach his head as he went.

Like every teacher in our school, Mr Kalima used to have a long stick to scare us with. But unlike all the other teachers he never used to hit anyone with it. When someone in our class was naughty Mr Kalima would call the misbehaving boy or girl to the front of the class as he reached for the stick. Just as all the other teachers would do. Like all the other teachers he would swing the stick high up in the air and then bring it down with a whoosh…but then he would stop it before it touched anyone. We used to work hard, not because we were afraid of the stick, but because we liked the kind and old Mr Kalima.

Other teachers took a different approach to Mr Kalima.

I made sure that I was good at Maths in Primary 6, the year after I was in Mr Kalima’s class. By then we had another teacher called Mr Samuel. He would write some Maths questions on the big board (called ‘ikibaho’in the Kinyarwanda language that everyone in Rwanda spoke) at the front of our classroom. We’d take up our crayons or itushi as we called them and our writing boards (known as ‘Urubaho’) ready to do the sums. Everyone knew what was going to happen next.

I made sure that I knew mathematics very well. When we had finished, we would then go to Mr Samuel’s desk to show him what we had done. He would slowly, carefully, look through the urubahos of my classmates. Then he came to mine. He would look through, write

‘10 out of 10’on it and then keep my urubaho to himself so that no one could see my answers. Then Mr Samuel would line up…and anyone who failed to get enough answers correct was beaten with a stick by Mr Samuel. He would go along the line but miss me out. That is why I made sure that I was good at Maths.

Singing with Mr Kabiligi

Myotherfavouritelessonwasmusic.Irememberourteacher,Mr Kabiligi,well.Hewasjustgraduatedfromteachercollege,andhe taughtusnewsongsinFrench,andletussingouroldsongstoo.

Iremember,inparticular,MrKabiligiteachingusasongaboutan apprenticeshepherd.ItwasinFrench.ItIscalled Quand J'étés Chez Mon Père (l'apprenti Pastoureau).Iwashappytofinditon YouTubewhenIlookedforittheotherday.

Ienjoyedsingingatschool.Withmyfriends.

Dodging the ball withAthalie and the other girls in my class. There were about forty students in our class. That might seem like a lot but for us it was about average in those days in Rwanda. Athalie was my best friend in my class. Each weekend either I would go to her house, or she would come to mine to play. I loved going to her house because they had a garden which had all kind of fruits. We’d get to her house, say that we were going outside to play and just sit in the sun and sing and eat the fruit that grew all around.

Anyway, back to school.

At break time, about half past ten, Athalie and I would play together, along with the rest of our class. Our favourite game was what you would probably call dodgeball these days. We had one small ball to play with. Some of the girls in our class would stand around the edge of the playground and the rest would stand in the middle. The girls round the edges would try to hit the girls in the middle with the ball… who had to escape and dodge the ball. If you were hit with the ball you were defeated. Whoever remained would be the winner. There was another way to win: if you were in the middle and caught the ball, you would be a winner too. We had blue dresses, called a Kontoni, that was our uniform, and I would try to use the dress to catch the ball. It was fun.

Our big family

We were a big family.

At that time in Year 5 and 6, I was the oldest of the children at home in the village. There were three of us. There were my brothers: Charles, Charleston and I. Dani and my sister Emma were very young and lived with my parents in Kigali. But that wasn’t all of us. I also had five older brothers and sisters who had also moved with my parents in the city.

My sister Ruth was married and lived in Kigali with her husband, Gashumba.Amon and Rose were also away and working in the city. Finally, there was also Manasse who was studying in Burundi before coming home to study in Gitwe, a little way from our village.

At home, Charleston was with me all the time. He helped me cook,

clean up, and wash the dishes. We would sing together as we worked. Then he would ask me for permission to go and play football. Charles spent most of his time with our grandparents, making sure that they were ok and looking after them as they got older. Charles was always visiting and singing with neighbours. He was always happy.All the neighbours loved him, his singing, and his happiness. Dani was younger but was funny too. He made us laugh all the time, imitating how everyone talked and walked.

All us kids loved eating ubugali, or fufu. We made it with cassava flour, it is like cooked, soft bread and we ate it with isupu, a kind of gravy. Dani, in particular, loved fufu. ‘No fufu, no eat’, he used to repeat.

Ruben

Ruben is my eldest brother and the first child that my Mum and Dad had when they got married. Ruben was such a loving person…but he grew up in a way unlike any of the children in our family. My parents took him to the primary school…but instead of going to classes he would go off and do other things. Ruben found his passion not in school but in gadgets. He’d repair watches, bikes and radios, anything that had moving parts. He didn’t finish primary school but grew up learning to be a repair man. People would bring him a radio. He would repair it and it would work. That was his job.All day, every day, he was surrounded by older people, and he soon learned how to drink and smoke. My parents hated Ruben’s drinking and smoking – in our house my dad never allowed there to be any beer or cigarettes. Dad

was so disappointed in what Ruben was getting up to. Dad tried and tried but just couldn’t persuade him to drop his habits.

Despite all this, Ruben married a very beautiful woman called Rachel. They had four children called Odette,Anita, Peace and Emmanuel. But because of his drinking habit, Ruben was not a good man to look after his family. Rachel would work hard. She’d do everything. She’d grow food in their garden for their family and sell any extra that they had to buy clothes and other essentials for the family. Ruben would not dig in the garden. He’d work at his repair shop.And drink and smoke. Finally, Rachel decided to go back to her home and leave Ruben because of his lifestyle.

When Rachel left, Ruben came to live with us. He continued to drink and smoke, which my dad didn’t like. When he was at home, he would try to hide his beer and he would smoke outside…but not in the house, at least.

Ruben wasn’t like us, but he was one of us. Deep down he loved us, and we loved him.

Silas and Elizabeth

Silas and Elizabeth were our Grandad and Grandma. They were my dad’s mother and father. They lived close by in the village.

Like all grandparents anywhere in the world, they were there to give us all the food and drink that we could want. Our Grandma made a traditional drink called ikigage that people all around Rwanda would

make. Grandma used to gather sorghum, soak it in water for a few days and then dry it in the sun where it would get its flavour. Every time we visited; Grandma always had some ikigage for us to drink. She would keep the ikigage in a clay pot called ‘ikibindi’. She was quite a lady and lived until she was 105. She was still strong; she could see without glasses and hear without hearing aids until she passed.

My Grandad, Silas, was a quiet man. He made juice from the bananas that grew in the village, and we’d all drink it from a ‘Umuvure’ (a hollowed-out tree trunk) using long straws.After we had enough, Grandad would take the rest of the juice and turn it into banana beer that he would sell to the men in the village. Before Grandad made the banana juice, we children were allowed to help him peel the ripe bananas and put them in the Umuvure. We probably weren’t the best workers: for every two bananas we would peel, we would eat one and then put the second in Umuvure. Although we were sure we were being ever so clever and hiding what we were doing, Grandad’s knew exactly what was going on, but pretended to not have seen us. I guess, like Grandads everywhere, he just enjoyed being with his grandchildren.

After making banana juice, Grandad made it into a kind of beer and then went to sell it on the street. All the men in our local area loved it. They loved it so much that they would often drink too much of Grandad’s banana beer and get rowdy and loud late into the night.

Even today I can picture Grandad wearing his shorts and a top when

he was doing his work. He had white, grey hair. When visitors came around, he would put on a colourful wrap around his waist and another around his top. That was the traditional look for older men in Rwanda at the time. He had a round hat and walked with a stick. On a Saturday we would all go to Church, but Grandad said that he was too old to come with us. Instead, he had his own way of worship. He would wear white, not the colourful clothing that he wore during the rest of the week. He would sit outside on the Sabbath, and I would hear him singing an old favourite hymn of his, welcoming the Sabbath as a special day of the week. In Kinyarwanda, he would sing “Nkunda guterana ku Isabato, kwiga ijambo ry’Imana”, which roughly means “I love to welcome the Sabbath when I can learn from God”. When I sing that hymn now, I always remember my Grandad, sitting outside of his house, looking kind and wise in white.

I loved Grandad so much.

My Dad

Tea. My Dad loved a cup of tea. With milk.Always. Whenever I think of him, I can picture him with a cup of tea. Wherever he was inside the house or out in the garden, he had a cup of tea in his hand.

My Dad always dressed well. More often than not he was in a suit. He was always smart. Even on his day off he would look good with his shirt and tie on. With a cup of tea in his hand, of course. During my holidays, I made sure his tea was in the flask, put on the table where he used to sit; when he came home from work, he would

find the tea waiting for him and he loved me for that. When I would go back to school (I was in boarding school) he would say, in joking way, that he would have a cup of tea when I was back for the holidays.

Dad was tall and slim and had few words. He spoke, in between sips of tea, when it was necessary; you knew that when Dad spoke, the words he chose would be important. But that didn’t mean that he was a lonely man. Each time his friends came round they would laugh so much, together. The moments that I could spend time with him, in my holidays from school, were always precious. I would go to work with him in his office in Kigali. He taught me how to type on the typewriter that he had in his office to write letters for people or translate letters from Kinyarwandan to French, English, and Swahili.

Dad was so protective of his children. He didn’t like us to go out and come home late. Six o’clock was the time when it got dark and six o’clock was the time that he told us to be home. Sometimes my brothers and I would go to concerts. We so loved to sing along to the songs that we heard performed there. The concerts would finish late, around nine or ten o’clock. So, when we were not back at six o’clock Dad would go looking for his stick. My Mum would see him…and then she would hide it so that he couldn’t hit us when we got home late. With the stick gone, my dad would wait with his belt.As soon as we would see it, we would run. My Mum would then keep watch…and let us know when it was safe to return to the house when my dad had fallen asleep. That all might sound quite shocking but, in those days, it was normal in Rwanda. All my friends would say the same thing.

By the next day, it would be as if nothing happened, he’d forgotten about being angry with us. I think that Dad was always a bit worried about us when we were out of the house…but we just loved going to those concerts.

Knowing that we were different.

On my first day in Year 5, we registered at School. The school administrator took down our details. They asked whether we were Hutu or Tutsi. Back then I didn’t know why they asked, or what being a Tutsi meant. I couldn’t understand why they wanted to know.

But because of the registration I knew that I was a Tutsi. There were about ten of us Tutsi in our class of forty. The others in the class were Hutus. There were always lots more Hutus than Tutsis in our school and in our village. My Dad told us that there were a lot more Hutus than Tutsi in the whole of Rwanda too. We knew that we were different and that we were few.

At the time in Year 5, it didn’t seem to matter that there were Tutsis and Hutus. We all spoke the same language, Kinyarwanda, we all sang the same songs, we all drank the same banana juice and ikigage. We were friends, good friends, with Hutu children – it made no difference to us or them who was who. They were good friends of ours, without exception.

Apparently, everyone in the village knew who a Tutsi was and who was a Hutu. My Mum and Dad knew very well who was who. When I asked them about it after the school registration, they wouldn’t say

anything more. But the glances that they exchanged and the way that they hastily moved the conversation on made me wonder what they weren’t telling me.

Leaving Primary School…and going nowhere

Things changed when I left my primary school. I left my village with all the good memories of the making banana juice, the friends I would walk to school with and the familiar sound of the radio from early in the morning.

I dreamed of being a doctor and I thought that I might just be able to achieve my ambition. I had worked hard in school, and I’d got good grades. I thought that if I continued to study hard, I could pass my secondary school exams and then start my medical training. Things turned out differently…

For the first time in my life, I started to understand why my Mum and Dad exchanged those glances when we would talk about Hutu and Tutsi. The first time I started to realise was when the results of the tests we had done at the end of our time at Primary School were announced. My teachers told me that I had done well…but when the lists of results were put up, I couldn’t even find my name. Neither could any of the other Tutsi children who I had been in Primary School with. It was as if we didn’t exist. The same thing happened all over Rwanda. Because we were Tutsi, we were not judged on how well we had done but simply by our identity. Hutus could move on to the next stage of their education as they wished. We were not allowed. Without my ex-

am marks I couldn’t go on to Secondary School…and I would have no chance at all of being a doctor.

There was one other option: private school. The problem was that, like most other Tutsi children, my family were not rich and there was no way that my parents could afford the money that it would cost to send me away to a private, non-government, school. It meant most Tutsi children had to leave school and had to try to find a job. We wouldn’t have any future at all, no proper education, no chance of training in a trade or going to university. Our hopes for a good future would be dashed.

Tutsi girls, in particular, had limited choices because they couldn’t go on to secondary education. In Rwanda at the time, it usually meant that they would get married at a young age, have children and be a mother and stay at home whilst their husband went out to work. I thought that I would marry and have children one day, but I wanted to see what I could achieve in the world, I wanted to help others as a doctor…I didn’t want to get married and have children just yet.

I was lucky, though. My parents were almost as determined as I was that I would keep learning and have a future with choices and decisions that I could make. When men came asking to marry me, my parent refused. Other girls were not so lucky. They told the men that they wanted me to keep going to school and that somehow, they would make it happen. My Dad told me that he had a dream that I would go to university one day. He would tell any man who came to ask me to

marry them, that his child would go to school instead.

Since we didn’t have enough money to pay the fees to go to the private secondary school, my dad found another school. Here I could learn things like cooking, sewing, and typing. It didn’t provide the education that I needed to become a doctor, but it did keep me learning.

Another door opens.

My eldest brother, Manasse, had a job selling Christian books during his holidays. He told me that he would get me to secondary school. So, over a holiday he saved all the money he made from selling his books and gave it to me so that I could go to a private secondary school. He didn’t keep a penny for himself. He saved enough to pay for one term at a nursing school. It meant that I probably wouldn’t be able to become a doctor, but it seemed like a miracle to me. I could learn to care for people and help make them better. I had no idea where we would find the money for the next term and the one after that, but it was a start.

I remember my brother giving me the fees for one semester, he said to me, the rest God will pay it.

Before the start of every term at nursing school, my family would struggle to find the money to pay for the next term.And the next.And so on. I remember the night before the start of every term my parents would never sleep, wondering where the school fees would come from. Somehow miracles always seemed to happen. My Dad, relatives and friends always seemed to find a way to find the money. Some-

times good samaritans who I never knew paid my fees.And so, it went on. By the time the calendar had turned over to 1994, I had made it to the last year of my nursing training.

The Radio Request

My whole family loved music. Music was something that really brought us together. Even though we were a big family with lots of kids of different ages music kept us together. Even though some of my brothers and sisters might be away from home, whenever they came home, we would play some music and start singing and we’d be one family together again. It was a tradition in our family that parents would sing together when they married…and their children joined in as soon as they were old enough.

My brother, Manasse, was a musician who liked to write songs. When I was a young teenager, he taught me to sing some of the songs he wrote. Out of all the children in our family, he asked me to learn one particular song for him. It was a long song, about a person in the Bible called ‘Job’. It was a story of how a person can survive through a great deal of suffering and still stay loyal and good to His God.

Whilst I learned Manasse’s song, he would be off writing other songs and playing them. He was talented. His friend, Sammuel, asked Manasse if he would like to record his songs for Rwanda Radio with him. Manasse accepted.As Tutsis it was really dangerous to go to important places like the radio station. But Sammuel really wanted to have his songs recorded and heard around the country…and we want-

ed to watch him record them. So, when the day of the recording session at the radio station came, my brother Charleston and my sister Emma and I got dressed up and followed along with Sammuel and Manasse. We figured that if we looked like we belonged in a place like the radio station then people wouldn’t ask any questions about who we were. Somehow, we were able to get in. I guess nobody was paying attention to a few young kids when all the focus was on the music. We hid in plain sight. Nobody challenged us or asked if we were the singers.

Then we were recognised.

Someone who had seen us singing in our local church spotted us. I froze.

If they knew that we had sneaked in without permission, we would be in real trouble. I could only guess what my Dad would do if we were found out.

Instead, the person who picked us out simply told his colleague that he knew we could sing and that we should perform for them. We looked at each other. We weren’t ready…but we couldn’t refuse. Manasse asked me if I could sing the song that he had asked me to learn. The song about Job.

Manasse played and I sang. We told them we could sing much better if all our family was with us, that we could perform it better next time if they gave us the chance.

Then we went home.

The next day we heard ourselves on the radio. Me singing Manasse’s song about Job. We were dumbfounded. On the radio? Us?

The day after, the radio station played it again.

People would contact the radio station and ask for the song to be played. They dedicated it to their friends and families. For a while, wherever I went people who knew me would just say ‘Job, Job, Job’. Even today, when I go back to Rwanda people who know me, keepsasking me to sing ‘Job’for them.

Dark clouds gather.

Being able to stay at the nursing school against the odds was like a ray of sunshine in my life. However, the sunshine came at a time when dark, ugly storm clouds were gathering over my school, my village and Rwanda.

The government who prevented young Tutsi people like me from going to school now started to spread hate against us too. On the way to and from school, I used to see and listen to people in uniforms singing “tuzabatsembatsemba” meaning “ we will finish them”. They were referring to Tutsi people. Usually, I would love to hear people sing. Now the songs we heard were those of hate. Hatred of us.

The haters shouted that we were inyenzi (which meant ‘cockroaches’) and chanted that Tutsi were inzoka (‘snakes’). They were comparing us to insects and reptiles – things that hurt others and it meant nothing to kill. They said that we Tutsi were enemies of everyone in Rwanda. Apparently, the government army was fighting a rebel army and extremists went around saying that the Tutsi people in Rwanda were helping the invaders. I did not know much about the history; but I knew that more and more people were being turned against Tutsis.

It began with words but soon it got even more serious…and came much closer to home.

I remember from 1990, Tutsi people who I knew began to disappear. First, there would be a rumour that a certain Tutsi person who we halfknew had disappeared.

Then another.

Then it was a distant cousin.

It came closer to us.

We heard stories of buses being stopped by thugs paid by the government. They would get on the bus, and demand to see everyone’s identity cards. Everyone in Rwanda had an identity card.Anyone who had ‘Tutsi’marked on their card was abused, spat at, beaten. Sometimes, a Tutsi man would be taken off the bus by the thugs and led away. Disappeared. Young Tutsi boys who weren’t much older than me were arrested and put to prison. The government said it was because they were helping the 'inkotanyi' (the name for the rebels). I knew it wasn’t true, but it didn’t matter. The storm clouds came closer and grew darker.

Soon, the dark clouds swirled around me.

I was in my nursing school at the start of a new term, Some of the Hu-

tu students, who had been our friends, came back to school with a different look on their faces. They looked at me in a different way. Instead of greeting me with a smile as they had done at the start of previous terms they now snarled or turned away. They spat out words at me as if I was an enemy. They had been listening to the hate speech that the government and extremists were spreading in newspapers and on the radio. Whilst they had been away during the holidays, they had started to believe the hate.

One day a group of Hutu students came up to me in the school. One of them showed me a knife and said, coldly, "You will see us tonight". I was petrified. I believed that they would carry out their promise. I thought that I would disappear like other Tutsis had.

That night I ran.

I ran from the school. I hid in the fields that were right next to our school. I hid in the bushes. I couldn’t sleep as I waited and watched. Ready to run again, I decided to go to my auntie who lived nearby. I spent the rest of the night with her and then, as the glow of the sun began to appear and push night away, I had to decide what I would do next. Should I stay away from the school? I couldn’t stay out there forever, Should I try to go home in Kigali? If I did, what would I say to my parents? I would be ashamed. Should I go back to school? I knew that I would have to see the Hutu students who had threatened to kill me in the corridors and in my classrooms.At least I knew that they wouldn’t attack me during the day.At least the teachers would be on

my side and would protect me. They would understand and put a stop to the terror.

Surely. Surely?

I went back. Instead, the opposite happened. I was accused of inciting the hatred! I was told that it had all been my fault and that I had provoked the Hutu students. I was suspended and sent home. I was not alone. Some Tutsi students had been suspended from school for two weeks. I was ashamed. My parents were asked to come with me to school after the fortnight was up. My Dad was made to apologise to the principal for my ‘behaviour’and beg him to allow me to return to the classroom. He had to plead with him. My Dad had to promise that such ‘behaviour’would not happen again. I hated the injustice of it. I hated the fact that my wonderful, proud, and honest Dad had to plead for forgiveness for something that I had not done.All because we were Tutsis. Such was my life at school now. Such was the atmosphere of hatred, discrimination, and persecution in Rwanda.

The storm was closing in. Everyone knew that it would soon break.

Part Two: During

These are the memories that I have from my life in Rwanda during the Genocide. You’ll forgive me if all I can do is present you with just a few fragments.

I haven’t got any pictures from the sixty-two days that I was running and hiding from the killers.All we could do was to try and stay alive.

All I have are my memories of those times.

In 1994 the storm broke. In just a hundred days, more than a million men, women and children were murdered simply because they were Tutsi.

Heading home inApril 1994

InApril 1994 we were supposed to be on holiday from school. Because I was studying nursing I usually stayed at our school, along with all the other nursing students. We normally had placements during the holiday so we would stay at the school when everyone else went home for a few weeks. We had to stay the extra days because of the placement.

However, as the Easter holiday approached inApril 1994, I was ill with malaria. I was admitted to a clinic close to School with the disease and then went to stay with a good family friend calledAmon Rugerinyange, who lived closer to the school than my parents who were back in Kigali. I had no appetite, but Rugerinyange’s wife

(Mama Monica) would offer me anything that would help me to get stronger. Rugerinyange’s family cared for me as if I was their own child.

I am sorry to say that those few days of kindness were to be the last that I would ever share with them. I will always remember Mama Monica, her daughter Joy, and all her grand children who were with her - all were gone! Mama Monica was so kind, beautiful, goodhearted and loved everyone who came to her. I will always remember the care the family game me when I was ill and sick in their clean bedsheets; they looked after me, trying to find food I could eat since I had no appetite just to make sure I gained strength to travel and to the survival place in Kigali.

When I was just about well enough to travel, I got a taxi and went back home to Kigali rather than going back to School. I was still very weak and so my Mum and Dad thought that it would be better if I went home to be looked after by them.

My dream about our neighbour

The night before I left for home, I had a dream. It was one of those dreams that are really vivid, that stay with you when you wake up. I’ve never forgotten it.

I dreamt that I was walking back to our home in Kigali.After getting out of the taxi from School I met an old woman who was one of our neighbours. She asked me where I was going, and I told her that I was back from School to see my family. She said, and this will stay with me forever, ‘Well, let’s see what happens here soon…’

It was as if she knew something.

I thought it was an odd, troubling, dream but I was soon concentrating on the possibly dangerous journey home.

Travelling back to Kigali

When I came to travel back to Kigali, I decided that I wouldn’t take my identity card with me. The card told anyone who looked at it that I was a Tutsi. I knew that it could cause problems. I took a risk, and I left it behind at school. Journeys became increasingly tense as more and more hate speech against Tutsi people was spread every day on the radio and in newspapers. Every day, all over Rwanda, in villages and towns and cities, the same thing was broadcast: ‘Tutsis are cockroaches’, ‘don’t trust Tutsis’, ‘Tutsis are our enemies’. I could imagine those messages of hate spewing from Ugirashebuja’s radio as he dug with his machete back in the village where we went to Primary School.

An identity card marked as ‘Tutsi’made me a target.

Soon I knew that I had made the right decision.

On the journey back to Kigali, the minibus that I was on was stopped by thugs who had blocked the road. Everyone was ordered out of the minibus. Everyone was ordered to produce their ID card. I just told them that I had forgotten mine. Because I wasn’t local to the place where the bus had been stopped, they didn’t know who I was, they didn’t know that I was a Tutsi.

I was still at risk though.

The thugs who had stopped the minibus often accused anyone who couldn’t produce an identity card of being a Tutsi, a ‘cockroach’. This time I was lucky. They sat us down, they spat at us, abusing us as ‘snakes’as they did.

These young men where part of a group called the ‘Interahamwe’. In English this Kinyarwanda word means ‘Those who fight together’. The men had been recruited by the extremist government and trained to hate Tutsis. On this occasion, on the minibus, they let us go. Some they did not. Some unlucky ones were forced to stay. Some were not seen again.

I made it home. I was so relieved to see my Mum and Dad at home. They smiled and hugged me as I went through the front door. I thought that I would be safe from the hatred in my own house, with my family and in our own community that we knew so well. But our neighbourhood felt strange. It felt different. I could see little changes. People who had been kind neighbours now looked at me differently. They didn’t chat anymore. When they saw me, they moved away quickly. Or gave me looks. I could see that the long grass that had grown around the houses in our area had been cut down with machetes.

And next to our house a pit had been dug.

That night that the President’s plane was shot from the sky.

April 6

I was at home when the Genocide began. The night wasApril 6. At about eight o’clock in the evening the radio began to play sorrowful, classical music. We heard that President Habyarimana’s plane had crashed. Nothing more was said. That was all we knew. In my family, we talked amongst ourselves. Perhaps it was just the plane that had crashed. Perhaps the President wasn’t on board. But why play mournful music if he wasn’t dead? We had to admit that we really didn’t know what exactly had happened on that first night.

That night the noise was insane.

Shouting.

Neighbours running.

People being attacked.

Shooting.

Houses being burned.

We could see the glow of flames close by and in the distance. It seemed as if the city was alight.

We left our radio on; we were desperate for news. The classical music stopped at last, and a sombre announcer came on air. It was ordered that we should remain in our houses.

Roadbooks started to appear. Everyone who passed by had to produce their identity cards. If the card said that the holder was a Tutsi they were murdered then and there.

In those early hours, I saw people running everywhere. They were running around the houses, trying to find somewhere to hide. From

those glimpses, we recognised who the people were. They were Tutsis. Crowds were running, hunting.

The hunters were Hutus. Our neighbours.

They were hunting the Tutsis. Our neighbours. The killers knew where they lived.

We could hear them.

When the killers found a Tutsi, they shouted as if they had found an animal or a snake. Or a cockroach.

When they found a Tutsi, they would shout to others and close in as a pack.

I saw what happened next. I can still see it. It haunts me. It was horrible.

We were still in the house, obeying the instructions that we had heard on the radio. That was when my Dad called us all together and told us that ‘the war’had come. He explained that when he and Mum were younger some similar things to this had happened. That Hutus had attacked Tutsis before. That we had to hide. That it would be ok. I’m not sure if he believed what he was saying or not. Or he was trying to reassure us.

We didn’t know that it would become a genocide, I’d never heard of that word…it must have seemed to my dad that war had been declared on the Tutsi people inside Rwanda. This time the Interahamwe, the trained killers, would wage it…helped by ordinary Hutus from each and every neighbourhood in Rwanda.Awar waged by neighbours against their neighbours just because of who they were.

There were eleven of us in our house: My three brothers, Ruben,

Between April and July 1994 a million Tutsi men, women and children were murdered simply because of who they were. Killing took place every day, right across Rwanda. Below is a timeline of significant events that cannot record the horrific nature of what happened every day between April and July 1994.

April

April 6 President Habyarimana’s plane is shot down

The Interahamwe sets up roadblocks to stop Tutsi from fleeing. Thousands are targeted as the killing spreads

Soon the extreme elements of the army and interahamwe were on the streets killing Tutsi and moderate Hutu on lists

April 7

The moderate Hutu PM is murdered. 10 Belgian soldiers are also killed by Hutu extremists. Belgium pulls her troops out

April 21 The UN reduces the number of troops in Rwanda.

May

May 14 Prime Minister Jean Kambanda visits the National University of Rwanda to thank the staff for the well-done “work” of killing Tutsi

May 17 Massacres continue across Rwanda. The UN authorises 5,500 troops to be sent to Rwanda. None are available or will arrive until the Genocide is over.

May 25 The United Nations Human Rights Commission unanimously adopts a resolution stating that “acts of genocide may have occurred in Rwanda”

May 26 UN Secretary General says that the failure of countries to send troops to Rwanda is a “failure for the international community”

June

June 2 Rwandan Patriotic Forces liberate town of Kabgayi and rescue hundreds of Tutsis

The New York Times publishes an article with the headline “Officials Told to Avoid Calling Rwanda Killings ‘Genocide’.”

June 10 Hutu power government continue to massacre civilians hiding in Kigali and elsewhere in Rwanda

July

July 19 RPF, led by Paul Kagame, drive the Hutu power government out of power and leading to the end of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda by July 19.

RWANDA

Gisenyi By midday April 7 the killing has spread from Kigali. The Interahamwe trapped Tutsi in churches, where they had fled for protection, and murdered them. This process went on for weeks.

Between May –June Tutsi fought for their lives on the hills of Bisesero. They repeatedly pushed the attackers back but suffered hugely for their defiance.

The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda was perpetrated right across the country. Although experiences differed from place to place the merciless killing of innocent men, women and children continued for 100 days in north, south, east, west and central Rwanda.

RTLM radio broadcast encouragement to people to kill Tutsi after April 6. It told people to put up barriers to stop Tutsi escaping, named people to be killed and districts to be attacked.

Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by Paul Kagame, drive the Hutu power government out of power and leading to the end of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi by July 19.

In Kaduha ordinary people, including secondary school students gathered to kill. Afterwards they would meet at Bar Mugema to drink and talk about their ‘work’.

In late April, Tutsi gathered at a school in Murambi, promised protection by French troops. However, the soldiers disappeared and, after a brave defence, the Interahamwe slaughtered the thousands of Tutsi men, women and children.

Kigali 6 April 1994 President

Habyarimana is assassinated. This is the spark for the genocide to begin. The moderate Prime Minister is murdered and the killing starts. The killers use lists to target their victims

Nyamata Just over a week after the President’s plane was shot down the killing of Tutsi spread to Nyamata. Here thousands of Tutsis were massacred in and around Nyamata Church from 14 16 April 1994.

MY FAMILY

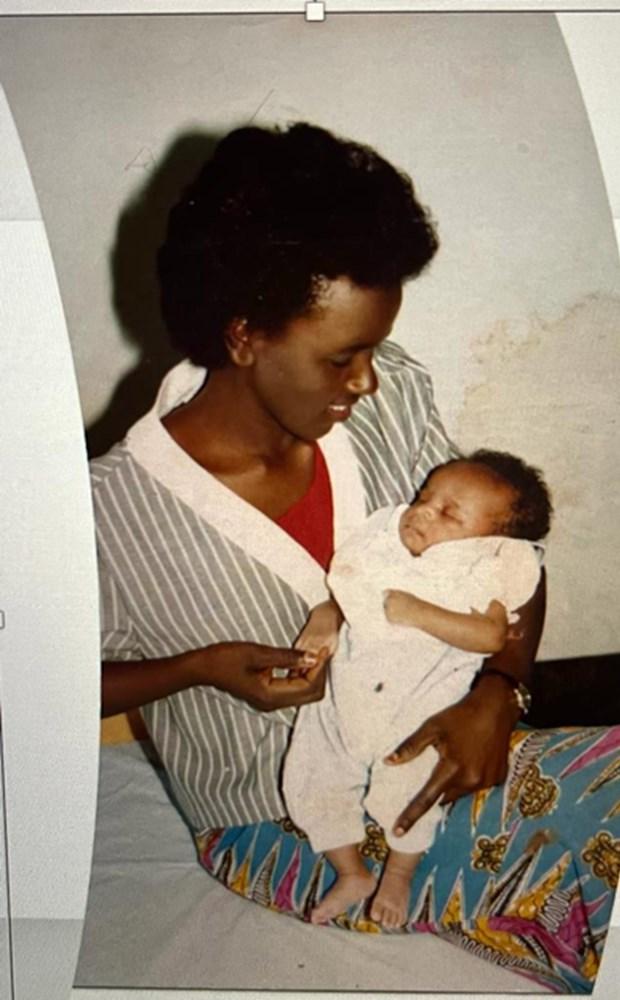

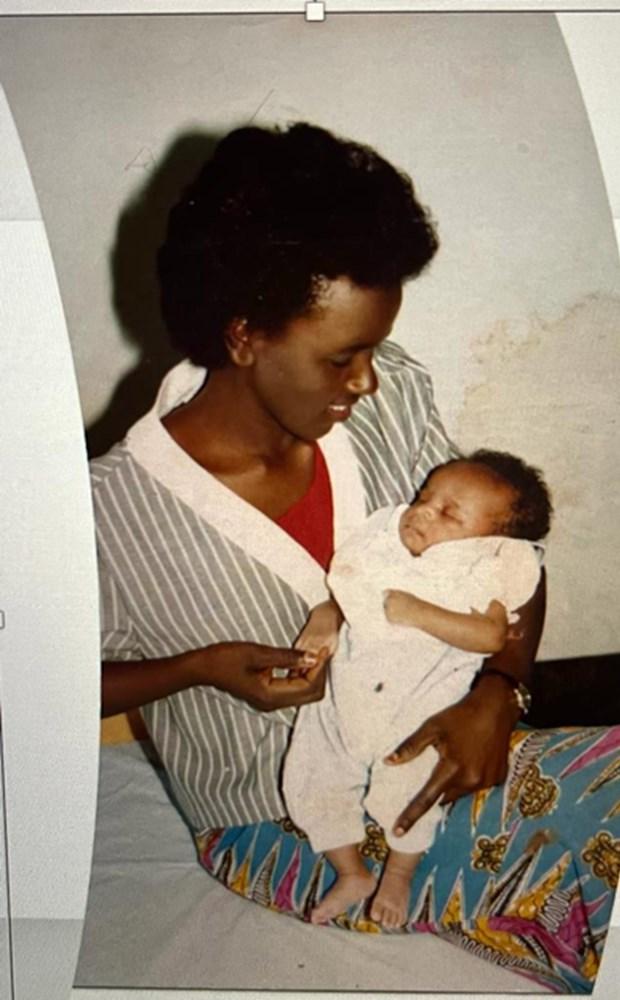

Our last family photograph before the Genocide.

My Grandparents.

Me and my niece, before the Genocide

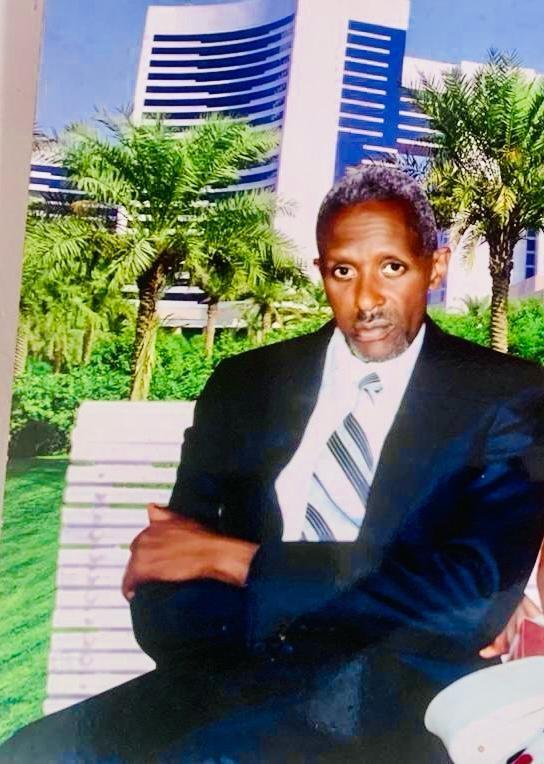

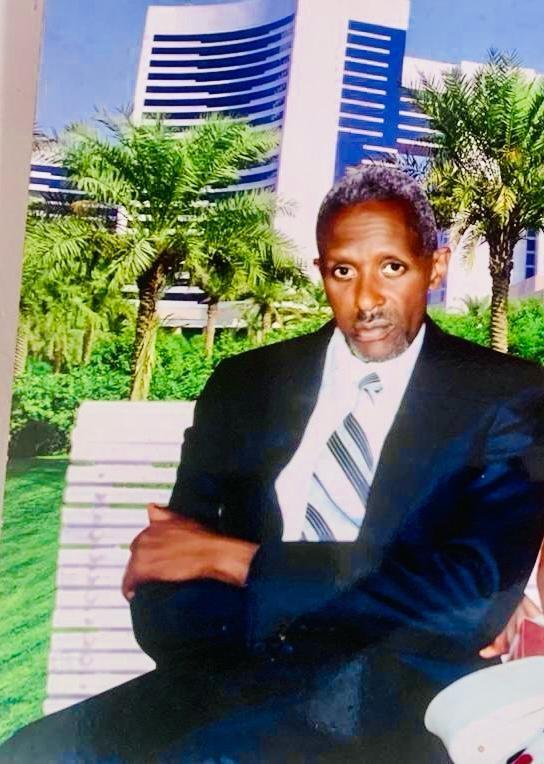

My Mum and Dad

My two brothers, niece and Dad who were murdered.

Me and my niece, before the Genocide

My Mum and Dad

My two brothers, niece and Dad who were murdered.

With my brother Ruben, after the Genocide

With my husband, Harreld, at a Buckingham Palace Garden Party.

Harreld and I, with our wonderful daughters.

Harreld and I, with our wonderful daughters.

MY FAMILY

Amon

Rusi

Chadrack

Emma.

Nana. He was just two years old during the Genocide

Rose

Charleston

Manasse

Amon

Rusi

Chadrack

Emma.

Nana. He was just two years old during the Genocide

Rose

Charleston

Manasse

Charles and Dani. My parents. My mum had a baby of just two years old (Nana). My two nieces, (Odette and Joselyn). Our cousin, Samuel. Minani.And myself.

Although the radio had said that we should stay in the house we could see that people were dying. We knew that if we stayed in the house, we would die…and so we had to get out.

I just froze. I didn’t know what to do.

I had accepted what was going to happen. There was no other way. There was nowhere to go, nowhere to run to.

My niece Jocelyn, my cousin Samuel and Minani decided to try and find their families and take their chances away from our house. They left.

Eight of us remained not knowing where to go.

Finding a hiding place

Living in the city meant that there wasn’t anywhere obvious to hide. We did have a garden with a few bushes in it, but we had already seen how the people who had tried to hide in it were discovered and attacked.And killed. We feared to go there to hide.

The perpetrators had already cut all the long grass and bushes in the neighbourhood. It made sense now.All this had been planned.All the hiding places had been removed. There were announcements on the radio that the tall grass should be cut. Chillingly, it also dawned on us that not only did this mean that the vegetation should be cut…but so

should human beings. Us.

The main road, just a minute away from our house gave us no avenue for escape. That was where the killers had already set up roadblocks to stop anyone from leaving the area. Local men had put obstacles like rocks or tree branches across the road to stop cars from going past. By the side of these obstacles small groups of killers stood or sat on chairs they had bought with them. They stopped anyone who tried to walk past. The roadblocks were everywhere. On each corner.

After a few days, the killers had decided to murder the Tutsis they caught by the road so that they could take the bodies away quickly. I had even sneaked up to the road one day just after the Genocide began, to see what had been happening there.

I saw bodies. The bodies of my neighbours who I knew well. They were just lying there, where they had been murdered. When I was there a car with killers inside drove past very slowly. My eyes met those of one of the Interahamwe. The killers, who hunted Tutsi like me.

Very slowly and deliberately he said to me ‘We will kill you and kill you until our children will ask us what you Tutsis used to look like.’

It was the last time that I went near to that road. I was so terrified.

But there was a slight chance. There was a glimmer of hope. We had a neighbour, Farouk, who was building some houses on the land next door to us. He was a good family friend and a friend of everyone in the area who just happened to be a Muslim. He said that we could go

and hide in one of the unfinished buildings on his plot. It was a risk for him, but he gave us his room out of his love. That was the only place that we could go to. The killers knew that no one lived in the houses, and we hoped that they wouldn’t go hunting for us there. We were not guaranteed to be safe there, of course.As the days went by the killers searched everywhere, the not-so-obvious places as well as the obvious places. If they found us in those houses, we would die. Farouk would also be a potential victim since he let us stay in his house. But because he had a kind heart, he risked his life for us. We thanked him, as a family, we will forever thank him. No one ever came to the houses, to the refuge we were in. The killers never thought that we would hide there.

The killers were local people. In every area it was the local people who set up and manned the roadblocks. They were our neighbours, we knew them.And they knew us. They knew my family. They knew that I was training to be a nurse, that I had sung on the radio. Even the man who rented the house next door to us was one of those who was on the roadblock. Here they would check the identity cards of everyone who went past.

Having ‘Tutsi’marked on your ID card meant death. The killers were young, middle aged and even older. Some of the killers really hated Tutsi, you could now see that they had a deep hatred that had been there for a long time. Others, like the Interahamwe, were taught to hate, they were brainwashed by the radio and newspapers to think that we were the enemies.

They did what they were told. Others just joined the killers to save

their lives. Others still said that they wouldn’t be part of the killing.

Some Hutus preferred to die with us because they didn’t want to be murderers.

Surviving the early days of the Genocide

The radio announced that everyone should stay indoors and leave our doors unlocked so that the ‘cockroaches’could be found more easily. In those early days of the Genocide, we left the doors open each morning as we left to hide until night. The killers would go into the house, search for us, and then leave unhappy. When darkness came, we could sneak back into the house. My parents would sit on guard, as we slept. They kept watch, looking out for the killers. Early in the morning they would wake us again and we would go to hide. That was how we spent our days.

Water supplies were soon cut off. Food was scarce. Both were dangerous to get. We were lucky because one of my brothers Charles, who was a primary school teacher thirty minutes’drive away in Mugesera, had recently brought us some food which we made last for a week. We also had a garden which had a few vegetables in it.

Ruben, my eldest brother

Before the Genocide, my eldest brother Ruben used to go to the pub and sit with some of the men he knew through his repair shop work. These men were Hutus…and became members of the Interahamwe. They talked in the pub about how they hated Tutsis and how they would kill them one day. Ruben would sit, drink, smoke and listen. He would hear the plans that the Interahamwe men were making. The ha-

tred that they were singing. Ruben too began to make his own plans.

When, in 1990, refugees from the civil war came to our area. They asked the government to replace the identity cards that they had lost. Ruben was so clever. He went and told the government that he was a Hutu refugee, from Byumba, running away from the rebel attacks and in need of an identity card. They gave him one. It said that he was a Hutu. He didn’t tell us any of this at the time, of course. Ruben quietly kept his Hutu identity card, ready for when he would need it.

When the Genocide began. Ruben put his Tutsi identity card to one side and took up his Hutu identity card. Whilst we had to hide, Ruben was able to walk around in the open, making sure that we were safe. The Interahamwe would stop him and check his ID card. Ruben had been seen around our house. They knew we were Tutsi…and yet Ruben’s card said he was a Hutu like them. Cleverly, every time they want to kill him that he is one of us, he told to them that although his mum was a Tutsi, his real father was not the Tutsi man in the house but instead was a Hutu from Byumba. They believed him. It made sense to them. Ruben was completely different to us. He was a drinker,Asmoker. None of us were. He seemed like an outsider to our family. That made sense to the Interahamwe.

Ruben helped many people during the Genocide. Using his skills, he changed people’s identity cards so that they had a chance to run away. Ruben saved many and they loved him for that.

11April

I remember Saturday 11 April 1994 very well.

One morning I pretended that nothing was happening. It was if I was in denial about the Genocide and wanted to believe that everything was ok.

I started to mop the house. Looking back, it was a crazy thing to do. There was such horror all around and there I was cleaning our floor. But it was a way to cope. It reminded me of normality, of the days before the killing started. Maybe, I thought, I could mop away the violence.

I looked up from my mop as my brother Charles came into the room. He always wore the nice jeans which he loved…but that morning he changed them and wore an old pair of jeans. It was as if he knew. He walked out of the house that morning. He went to visit a neighbour’s house to pray with them, which was a habit of his. He came back into the house and found me still mopping.

‘Why are you mopping? We are going to die’he said to me. Charles looked different in his eyes, very scared. Before I could answer him, a man came running from nowhere carrying a gun as if he was chasing and hunting someone. He stopped.

He grabbed my brother Charles, who was right beside me.

The Interahamwe pulled my brother away from me towards the road.

By now, I knew what would happen if you were taken to the road.

I could see my brother begging the man for his life.

Charles was taken on to the road. He was pushed to the ground and then shot twice. Charles made two sounds and then he died. That was the last time I saw my brother Charles. He was a quiet but social, loving brother. He was only twenty.

My brother Ruben went and sold the nice jeans Charles had taken off and then he bought some food with the money. Ruben cooked the food and brought it for us where we were hiding.

Before Charles died, I knew what day it was. I counted the days. I knew the dates:April 6,April 7,April 8 and so on.After Charles was murdered at eleven o’clock, I stopped counting days, or times; there was no point to knowing days as I would be dying anytime.All I could see was night and day, light, and darkness, that’s all.

The killer who took and killed Charles told the other Interahamwe at the roadblock that he was going to back for the sister. He meant me. My cousin Samuel told us.

When he came back to the house, I had gone to tell my parents about what had happened to Charles. I survived that day.

The announcement: I was to be killed the next morning.

The killing became like a job for the men in our area who carried it out. They would meet up and decide who they would hunt that day or the next. Often, they would disagree about who they would kill and argue about it. Once they had reached a decision, they would go out and kill for the day.

Later, after their day of ‘work’they’d meet again, discussing their ex-

ploits that day. Usually, they would drink and get drunk, boasting about what they had done before going home to their families. It soon became ordinary, a routine, to them.

Sometime later, I heard that the killers had talked about me at one of their meetings. They argued amongst themselves: some wanted to keep me alive for a while and use me, but others wanted to kill me immediately. They were convinced that, as I was studying to be a nurse, I survived, I would inject them with water and kill them or that I would marry an Inkotanyi and have children who would become ‘cockroaches’. Their enemies, a threat to them. Eventually, they agreed. They were going to kill me the next day. It was announced to us as a family.

That night, no one slept in our home. That night, we all slept in Farouk’s half-built house, where we normally hid during the daytime.

When dawn came, my mum told us that she would go home. She would stay there so that when the killers came to find me, they would find my mum.And kill her instead of hunting for me. She said goodbye and left us.As she left the room, I started to think. I couldn’t let my mum die for me. I walked out to follow my mum. If she was to die, I wanted to die with her. I told no one else. I left the room where my dad, Dan and Odette were. Mum always carried Baby Nana, that meant Nana was going to be killed too on my behalf. No one would look after the baby. I ran to be with her in the house.

We had left the doors to our house unlocked as ordered by the authorities on the first day of the Genocide.

My mum was in her room, looking out the window for the approach of the local Interahamwe. She turned and saw me. She begged me to leave. Mum was crying, telling me that she does not want to see me die in front of her.

It was the noise of the approaching mob of killers that we heard first. It halted our conversation. I shifted my eyes from my mum as she did for me, and we both looked out the front of our house.Acrowd of people were coming. They carried machetes. They snarled. My eyes, bleary, blinking through my tears could not identify anyone and yet I know that they were people that I knew well. They came closer. They were here. Banging on the door. Shouting my name. Telling us to open the door and let them in. I called back that I would open it.

But the door wouldn’t open. It was stuck. They hammered at the door. It wouldn’t budge.

That very morning, that door when the killers came through, had refused to open, when everyone in the house tried to open it as we were instructed by the government, it was as if someone strong was not allowing the key to open it, we had given up and left it close, but the opposite door was opened wide.

My mum was screaming at me to leave. To run. I don’t know how I got strength to leave my mother and Nana, I forgot the mission to die

with them then I left. Running out the back door as the killers tried to surge into the house from the front.

I went to another neighbour, closest to our house, hoping that the Interahamwe wouldn’t see me.At that moment they were all focusing their rage on the door that wouldn’t open. They were too busy to see me dart from the back of our house.

The neighbours chased me away from their house. They were frightened, telling me that they wouldn’t shelter me.