@greymattersjournalvc

@greymattersjournalvc

Beyond the Billboards: Uncovering the Hidden Potential of GLP-1 Medications

It Takes a Microbial Village: Maternal Microbiota and Neonatal Neurodevelopment

PANDAS: A Not so Fluffy Disorder

FEATURED ARTICLE

8

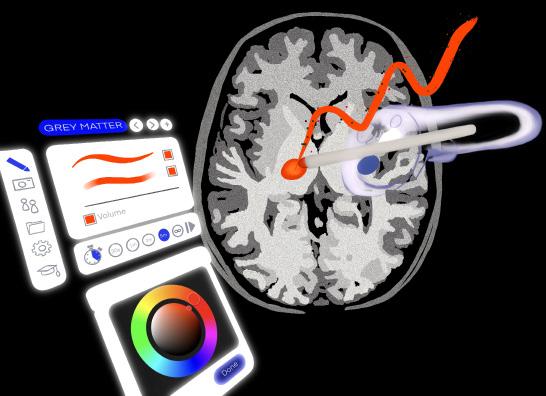

BEYOND THE BILLBOARDS: UNCOVERING THE HIDDEN POTENTIAL OF GLP-1 MEDICATIONS

by Jacqueline Rosenblum | art by Grace Buckles

13

BRAIN UNDER FIRE: WHEN FEVER TURNS TO SEIZURE

by Lucy Gaffneyboro | art by Cora Thompson

17

UNDER THE SURFACE: REVEALING THE MECHANISMS BEHIND EATING DISORDERS

by Sam Jacobs | art by Emily Holtz

23

FROM DEAN'S LIST TO DRAINED LIST: THE BRAIN SCIENCE OF BURNOUT

by Joseph Lippman | art by Racine Rieke

FEATURED ARTICLE

27

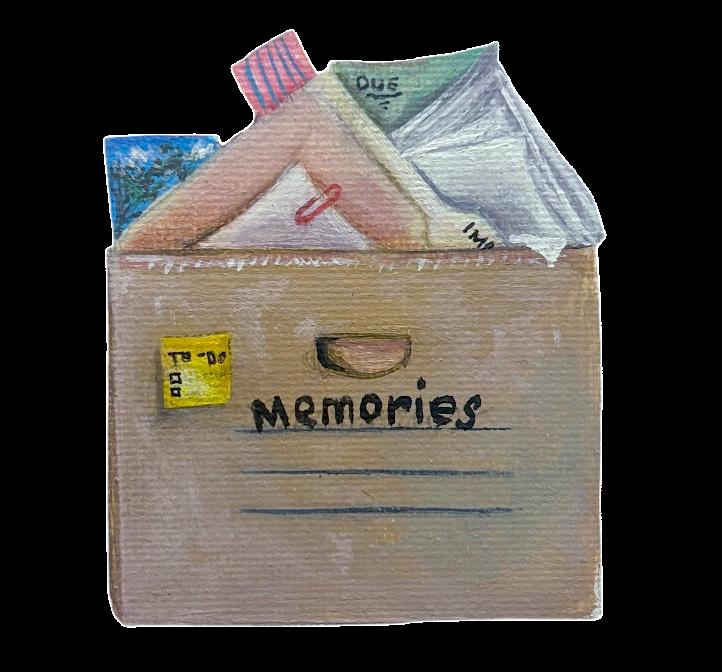

IT TAKES A MICROBIAL VILLAGE: MATERNAL MICROBIOTA AND NEONATAL NEURODEVELOPMENT

by Jannessa Ya | art by Elizabeth Catizone

34

38

PICTURE PERFECT: THE NEW REALITY OF REHABILITATION IS VIRTUAL

by Sushama Gadiyaram | art by Alexandra Tapia

WAKE-UP CALL: THE DISASTROUS CONSEQUENCES OF SLEEP DEPRIVATION

by Daniel Bader | art by Erica Langlais

44

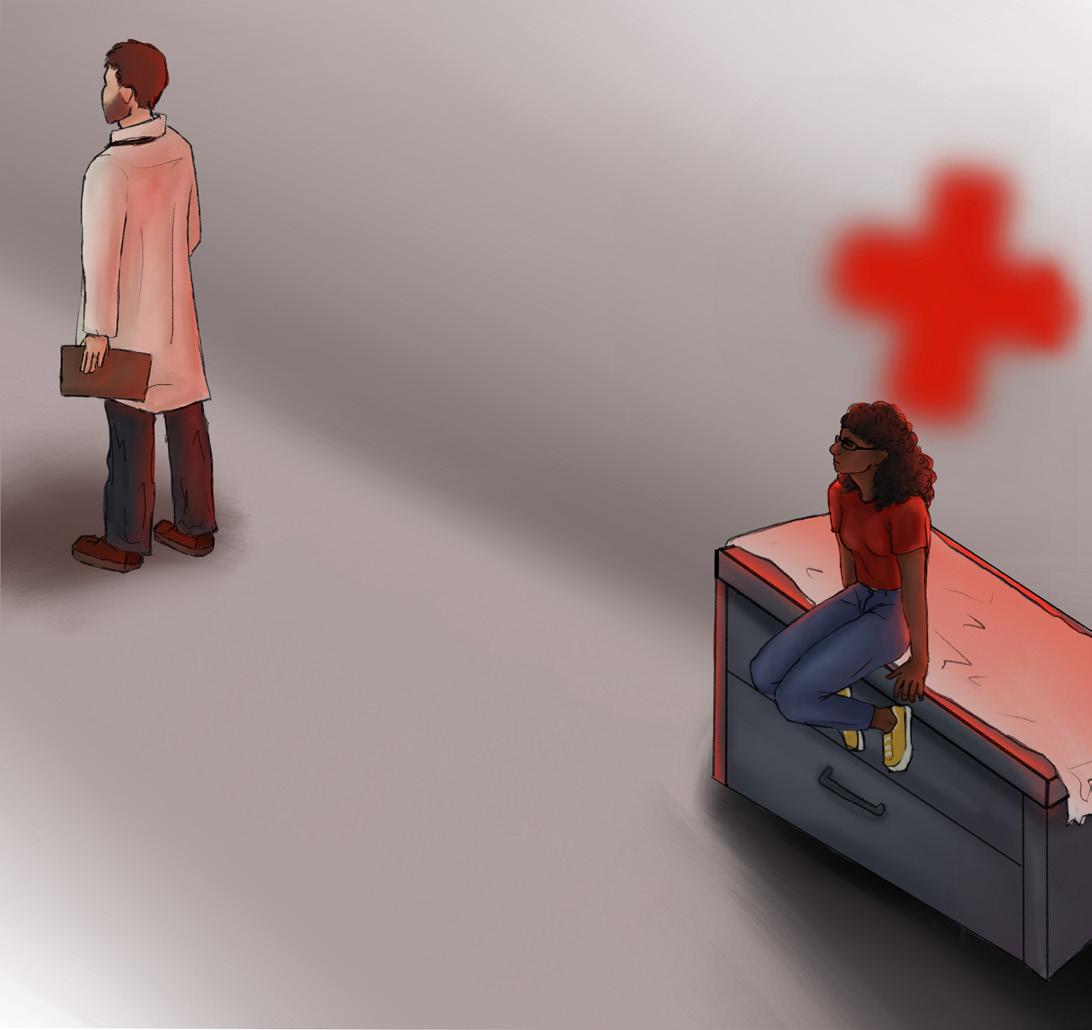

COMPASSION DIVIDED: HOW RACIAL BIAS IMPACTS EMPATHY

by Yasmine Alami | art by Ella Manhardt

FEATURED ARTICLE

48

53

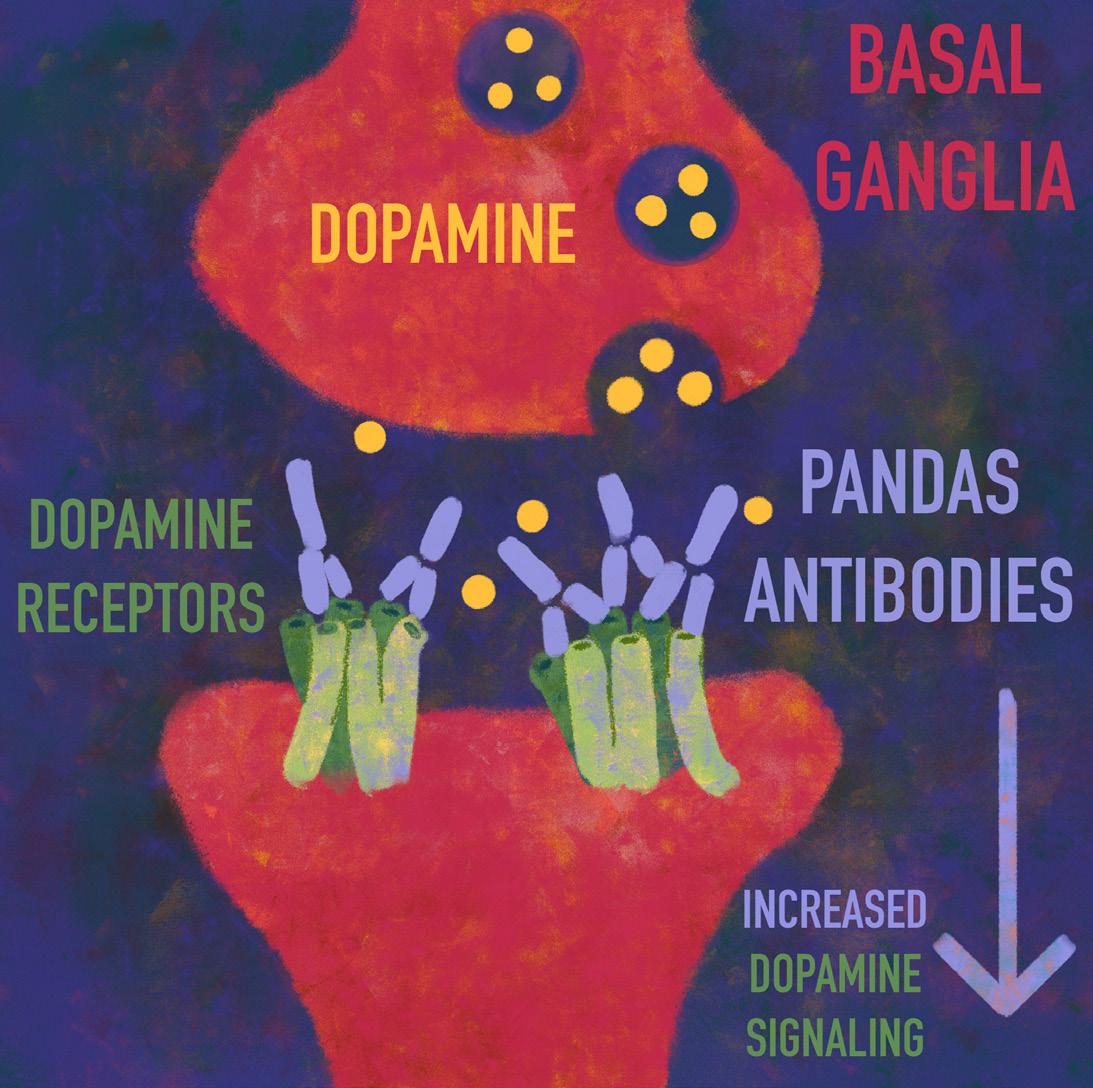

PANDAS: A NOT SO FLUFFY DISORDER

by Cailey Metter | art by Leo Malkhe

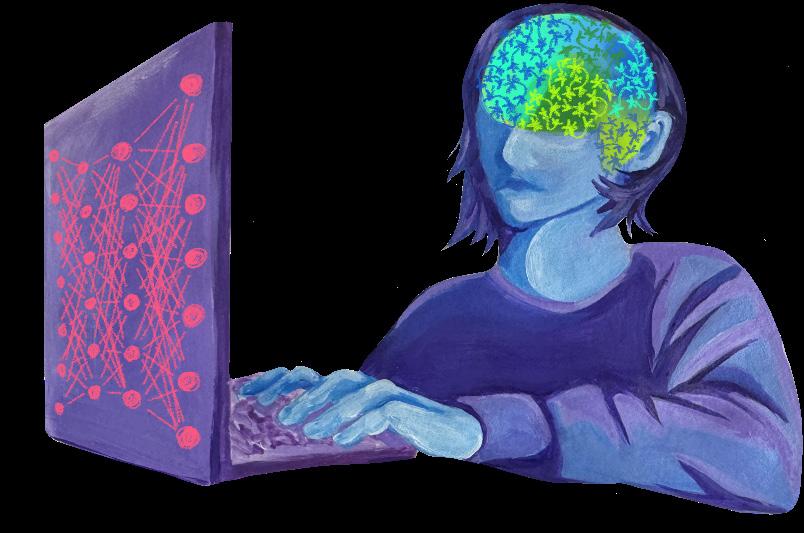

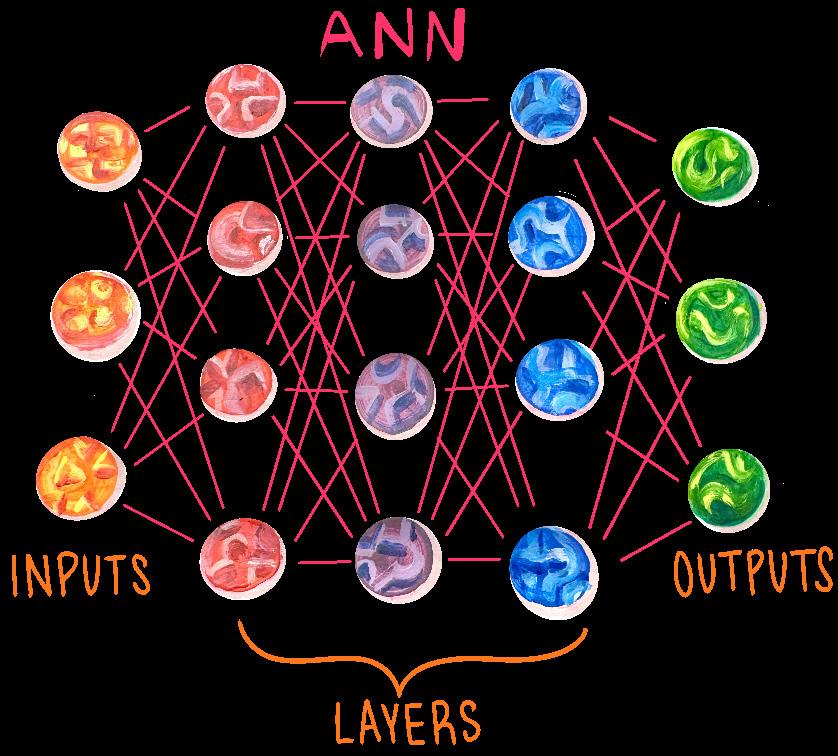

COMPARING MINDS AND MACHINES: WHAT WE’VE LEARNED ABOUT LEARNING by Jaron Ezekiel | art by Sarah McDonald

Art by Alexandra Tapia

If you have any questions or comments regarding this Issue 11, please write a letter to the editor at brainstorm.vassar@gmail.com.

Check out our website to read our articles, find out how to get involved, and more at greymattersjournalvc.org.

Alexandra Tapia

Cora Thompson

Elizabeth Catizone

Ella Manhardt

Emily Holtz

Erica Langlais

Grace Buckles

Leo Malhke

Racine Rieke

Sarah McDonald

Anoushka Bhatt

Ashley Hong

Caleb Joyce

Caroline Martin

Hannah Lee

Matthew Rawson

Max Tuz

Nika Jalali

Paige King

Sydney Keenan

Talia Mohideen

TJ Schully

Veronica Crenshaw

Cailey Metter

Dan Bader

Jacqueline Rosenblum

Jannessa Ya

Jaron Ezekiel

Joseph Lippman

Lucy Gaffneyboro

Sam Jacobs

Sushama Gadiyaram

Yasmine Alami

Alex Astalos

Alex Orellana Rico

Alexis Lazarte

Alma Sutherland-Roth

Ashton Spradling

Bailey Mann

Charlotte Tobin

Emily Nothdurft

Jadyn Smith

Kavi Agnihotri

Malathi Kalluri

Ren Nicolau

Stella Petersen

Tara Dacey

Bojana Zupan PhD

Evan Howard PhD

Hadley Bergstrom PhD

John Long PhD

Lori Newman PhD

Stephanie Jackvony PhD

James Hatch — Layout

Summer Stern Layout

Catherine Zhang Layout

Anna Cohen

Basma Sultan

Chloe Bilger

Claire Paris

Cooper Jaffe

Jenais Panday

Julian Cardenas-Moncada

Kaitlin Raskin

Lea Repovic

Lena Lynch

Lila Horberg Decter

Lily Paine

Mercer Colby

Nazwa Rahman

Shayni Richter

Sophia Lorens

Stephanie Norris

Susie Osborne

Tyler Lawton

Zachary Cahn

Zoe Rodriguez

In a world where we are constantly inundated by flashing headlines, phones buzzing with notifications, and an endless stream of social media posts, it can feel overwhelming to wade through the sheer amount of information that surrounds us. Attempting to find reliable scientific news online often feels futile: a simple Google search might return links to academic publications filled with complicated terminology, inaccurate social media posts, or politicized news articles that undermine the integrity of scientific research — everything but a clear explanation. Grey Matters Journal at Vassar College aims to cut through the noise by remaining dedicated to our mission of providing our readers with reliable scientific articles that are approachable for readers of all backgrounds.

Throughout my first publication cycle as Editor-in-Chief, I have been endlessly inspired by the efforts of the GMJvc team to make neuroscience accessible. I have watched the articles of Issue 11 truly come to life over the past semester, growing from proposals to fully developed pieces that are creatively crafted and rigorously researched. Each article reflects the collaborative effort of students who came together to engage in meaningful conversations about science with the intention of opening the world of neuroscience to the public. Witnessing these conversations encourages me to continue pursuing the goal that motivated me to join GMJvc in the first place — making scientific research accessible to every reader — and makes me feel optimistic about our generation’s commitment to accessibility within science.

I am honored to have had the opportunity to lead our incredible team this semester, and am beyond excited to turn Issue 11 over to our readers. Upon opening this newest issue, you can expect to find a variety of articles that span the breadth of the neuroscientific field. I invite you to learn about neuroscientific breakthroughs, such as the growing neurological applications of GLP-1 drugs in ‘Beyond the Billboards: Uncovering the Hidden Potential of GLP-1 Medications’ or the use of virtual reality in neurorehabilitation in ‘Picture Perfect: The New Reality of Rehabilitation is Virtual’. Readers can also discover the neuroscientific basis of issues such as work-related burnout or lack of sleep in ‘From Dean’s List to Drained List: The Brain Science of Burnout’ or ‘Wake-Up Call: The Disastrous Consequences of Sleep Deprivation’.

Upon publishing Issue 11, I am immensely proud of how much GMJvc has grown as an initiative, and would like to thank our readers for enabling our journal to flourish. Thank you for your support, and I hope you enjoy reading Issue 11 as much as we have enjoyed working on it.

Sincerely,

Evelynn Bagade Editor-in-Chief

by Jacqueline Rosenblum | art by Grace Buckles

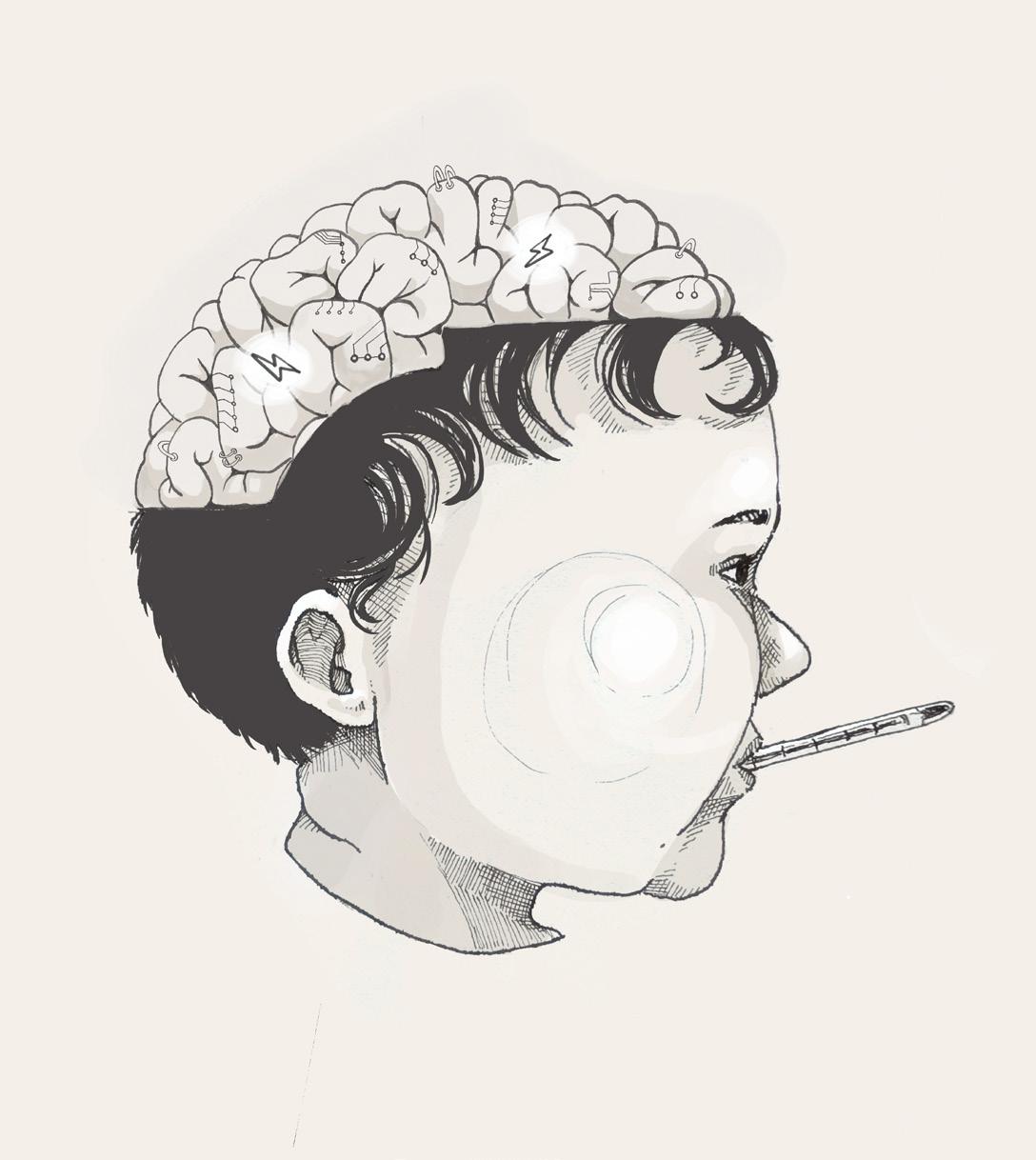

Whether you’re watching the morning news on cable or streaming your favorite movie, odds are that you’ve seen advertisements for Ozempic, Trulicity, and Mounjaro — medications used to treat diabetes. Now, these pharmaceuticals have rapidly entered public awareness as weight-loss drugs, becoming major cultural talking points on social media, in celebrity interviews, and across medical headlines. Behind this growing buzz lies a complex biological story about how these medications actually work. Originally, GLP-1 medications were prescribed to people with type 2 diabetes, a disorder in which the body is unable to properly regulate energy use and storage, specifically involving how the body’s metabolic processes break down the simple carbohydrate, glucose [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The key mechanism of these medications is glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1), a hormone naturally produced in the intestines, pancreas, and certain brain regions [6]. GLP-1 plays a critical role in maintaining energy balance by stimulating metabolism, slowing digestion, and signalling fullness after eating [7, 8]. Today, GLP-1s have hit mainstream media following the discovery of their powerful weight-loss effects, but this is not the full story [8]. What’s left out of the advertisements you’ve seen is that GLP-1 also communicates with the brain by interacting with neurons — specialized cells that send and receive the electrical and chemical signals within the nervous system [9]. Though initially formulated and prescribed for the treatment of metabolic conditions like type 2 diabetes, evidence is growing regarding how GLP-1 agents may be repurposed for the treatment of brain conditions that threaten neuron survival [4].

In the human body, an organ called the pancreas releases two important signaling molecules: insulin, which lowers blood sugar levels, and glucagon, which raises them [10, 11]. When you have not eaten for a while, such as while sleeping overnight, your blood sugar drops [11]. In response, the pancreas releases glucagon, which acts as a key to directly ‘unlock’ energy reserves in the liver, releasing glucose into the blood [11, 12]. Additionally, glucagon acts on fat cells to release fatty acids and on muscle cells to break down glycogen — the body’s stored form of glucose — thereby increasing the availability of glucose for energy conversion [11,12]. As you eat breakfast, your blood sugar rises, and the pancreas releases insulin, which becomes the new key that fits into a different

set of ‘locks’ [11]. This set of locks opens specialized ‘doorways’ in the cell membrane through which glucose can be brought into the cell by transporters for use or storage [11]. If a person’s cells stop responding properly to insulin, they are said to have insulin resistance — a hallmark symptom of type 2 diabetes, where the ‘locks’ become jammed or the ‘keys’ are missing, leaving glucose stranded outside the ‘doors’ [3]. Before a patient with type 2 diabetes receives a management regimen to address chronic high blood sugar, they may notice symptoms such as increased urination, blurry vision, a drastic increase in thirst, and unexplained nausea [13]. Additionally, when left untreated or managed poorly, type 2 diabetes significantly increases one’s risk for other long-term health consequences [14]. Such complications include high blood pressure, heart disease, liver disease, stroke, loss of vision, kidney failure, painful nerve damage, and sores or ulcers [14]. Additionally, type 2 diabetes is associated with a greater vulnerability to infection, bone loss, joint issues, and muscle problems — all of which can become severe enough such that amputation is necessary to address the immediate issue [14]. Together, these complications can greatly reduce quality of life, making the management and reduction of insulin resistance crucial in treating type 2 diabetes [8].

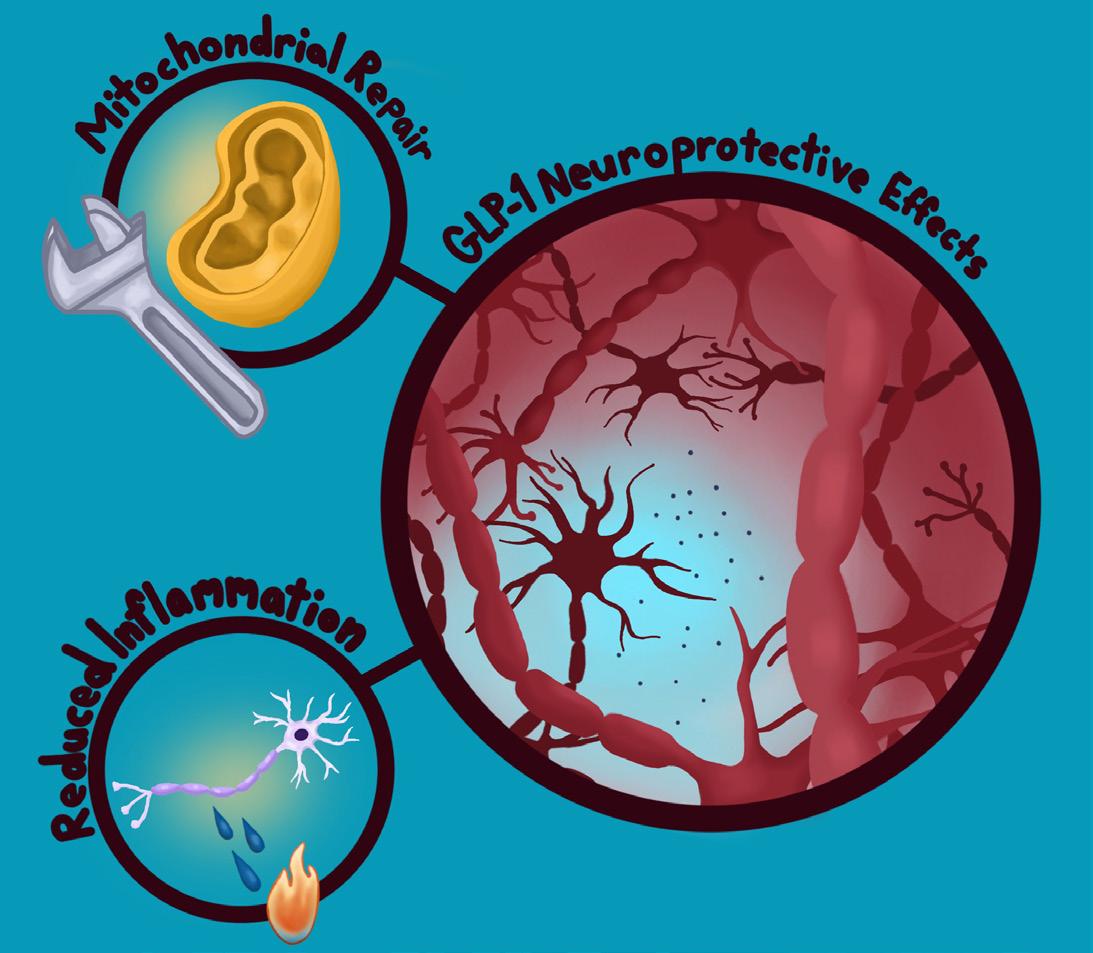

GLP-1-based therapies act by binding to specific receptors, thereby enhancing insulin release and suppressing glucagon secretion in response to blood glucose levels [15]. While this mechanism regulates blood sugar and weight by slowing the passage of food from the stomach to the intestines, the impact of these drugs extends far beyond the digestive system [8]. GLP-1, in both natural and synthetic forms, plays a critical role in the gut-brain axis, a complex

communication network linking metabolic function with the nervous system [16]. Because GLP-1 receptors are found in both the brain and throughout the rest of the body, GLP-1-based medications exert effects on various biological systems [16]. Interestingly, these drugs may offer neuroprotective effects by reducing neuroinflammation associated with both type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases [17]. Neuroinflammation is the brain’s response to injuries, toxins, and pathogens, which helps control damage, clear debris, and initiate healing [18, 19]. In neurodegenerative diseases, neuroinflammation becomes chronic as cells that regulate brain metabolism and immune response release inflammatory proteins, causing damage and leading to progressive neuronal degeneration [18]. The neuroprotective effects of GLP-1 medications are inspiring further research that could eventually position these drugs as promising agents for the treatment and prevention of neurodegenerative diseases [17].

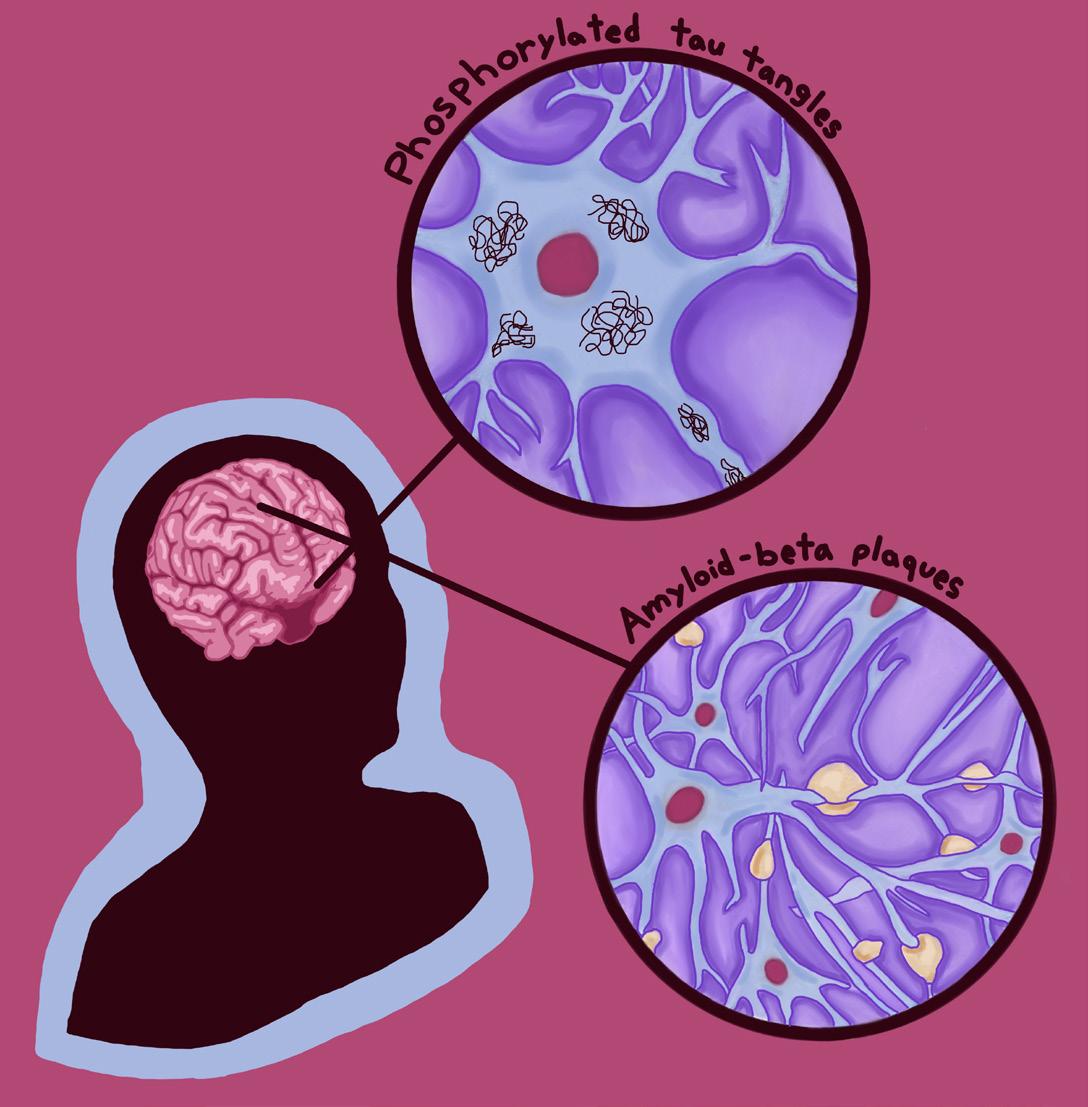

Dementia is a well-known umbrella term for several neurodegenerative conditions [20]. In fact, dementia is actually considered to be a pandemic condition among the aging population, with cases expected to double in the US and Europe over the next 25 years [21, 22, 23]. One disorder that falls under this umbrella is Alzheimer’s disease [20]. In its early stages, Alzheimer’s disease typically manifests as subtle changes in a person’s memory and thinking, such as forgetting recent conversations, struggling to make decisions, or becoming easily confused [24]. Over time, individuals may also experience shifts in mood or behavior, including increased irritability, episodes of verbal or physical aggression, and symptoms of depression [24]. Though there are no definitive conclusions regarding the causes of Alzheimer’s, there are two possible mechanisms that GLP-1s may manipulate to counteract this neurodegenerative condition [24]. The first mechanism is the buildup of two abnormal proteins: amyloid-beta proteins and phosphorylated tau proteins [24]. Amyloid-beta plaques are clumps of irregularly folded proteins that accumulate on the outer surfaces of neurons and disrupt cell-to-cell communication [24]. Additionally, the accumulation of abnormal tau proteins blocks the neuron’s internal transport system, impairing the movement of materials crucial for energy production and other cell functions [25]. The second mechanism contributing to Alzheimer’s development is impaired glucose

metabolism, in which neurons cannot properly absorb and break down enough glucose to produce adequate energy [18]. The brain has two types of cells: neurons and glial cells [26]. Glial cells are neuron-supporting cells that regulate neural immune response and metabolism [26]. One key function of glial cells is their ability to turn glucose into fuel that neurons can use [26]. While the role of glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s is debated, it is theorized that the amyloid plaques associated with the condition may prevent glial cells from converting enough glucose into sufficient fuel. This inconsistency reduces the energy available to neurons and may therefore reduce the production of chemical messenger molecules necessary for neuronal communication [18, 27, 28]. Conventional Alzheimer’s treatments aim to reduce the cognitive impairments that result from abnormal protein accumulation and deficiencies in glucose metabolism [18].

Synthetic GLP-1s are being considered as a new avenue for potential neurodegenerative disease treatments due to the growing evidence in clinical studies and animal models that type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s exacerbate one another [29]. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to develop dementia, including Alzheimer’s [30]. In people with type 2

diabetes, neurons become less responsive to insulin due to a lack of insulin receptors and/or interrupted insulin signaling [31]. Because insufficient insulin response impairs glucose utilization, neural insulin resistance causes an energy deficit among brain cells [31]. The resulting metabolic irregularity could disrupt the processes that maintain a healthy balance of functional proteins within a neuron as well as its waste-clearing mechanisms, leading to the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and phosphorylated tau [29, 31]. These protein abnormalities may subsequently disrupt communication to insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, thus reducing insulin production and insulin sensitivity throughout the body, worsening neurodegeneration [29]. Because both Alzheimer’s and type 2 diabetes involve the buildup of misfolded proteins that interfere with cellular communication and metabolic stability, GLP-1-based therapies traditionally used to treat the latter may be a new way to slow — or possibly prevent — the progression of Alzheimer’s [17].

The synthetic GLP-1 drug, liraglutide, has been shown to demonstrate this benefit in animal models by preventing abnormal protein accumulation that would otherwise impair glucose metabolism in neurons, contributing to the presentation of Alzheimer’s [4]. As a result, classic Alzheimer’s symptoms seem to be reduced by mitigating learning problems, restoring brain signaling, and potentially even reversing memory loss [4]. One example of how these mechanisms counteract the symptoms of Alzheimer’s is evident in the way that connections between neurons in the hippocampus — a brain region important for memory formation — strengthen in response to GLP-1 treatment [6, 32]. As a result, the brain is better equipped to store new memories, retain information for longer periods, and organize information more effectively [32]. People with Alzheimer’s who take synthetic GLP-1s seem to maintain normal brain glucose metabolism and have more gradual cognitive decline, delaying the progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms [33]. By reducing inflammation and improving glucose metabolism in the brain, neurons can generate the energy needed to support the growth of stronger, more stable connections, thereby delaying the deterioration of cognitive function [6].

Another potential application for synthetic GLP-1s is in the treatment of the neurodegenerative condition Parkinson’s disease [34]. Parkinson’s is characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms [34]. Motor

symptoms can present as muscle rigidity, involuntary rhythmic shaking at rest, and difficulty maintaining balance [34]. On the other hand, non-motor symptoms may manifest as cognitive decline, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating, along with dysfunctions that cause an abnormal heart rate and low blood pressure [34]. These symptoms are a direct byproduct of the degeneration of neurons within the substantia nigra, a brain region associated with motor control and coordination [35]. The substantia nigra contains cells that produce dopamine, a chemical signal that allows the brain to initiate and regulate smooth, intentional muscle movement [35, 36]. When dopamine levels drop, the brain’s communication with the body becomes impaired, leading to the motor symptoms that characterize Parkinson’s [35, 36]. Research into novel treatments for Parkinson’s disease is crucial, as it is the fastest-growing neurological disorder in the world [37]. Currently, Parkinson’s treatments are comparable to patches on a crack in the foundation of a house — current therapies manage symptoms and delay progression, but ultimately do not prevent the underlying disease [38]. As the number of people affected grows and neurodegeneration progresses, developing new approaches is essential to truly protect brain health [37, 38].

Fortunately, synthetic GLP-1s may offer new hope by protecting the brain in multiple ways [39]. One of their most promising effects is helping preserve the dopamine neurotransmitter system, as has been found in mouse models [39]. In Parkinson’s, the cells that produce dopamine slowly die off, leading to motor symptoms that impede daily functioning [39].

Because GLP-1s seem to shield dopamine-producing neurons to some degree, they can help those important neurons survive longer and function more effectively [39]. Beyond protecting the dopamine system, GLP-1s also appear to reduce harmful inflammation in the brain, as seen in Alzheimer’s mouse models [39]. Essentially, these drugs act as ‘firefighters’ containing a chronic ‘fire’ that gradually damages neurons [39]. GLP-1s support mitochondria, the cell’s energy factories, which become vulnerable in individuals with Parkinson’s disease [39]. In addition, GLP-1s may prevent misfolded proteins from building up and contributing to degeneration [39]. Because neuroinflammation, insulin resistance, and other biological mechanisms overlap across type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s, GLP-1s have the potential to offer meaningful effects beyond just symptom management for individuals with any of these conditions [17, 39].

NEXT GENERATION NEUROPROTECTION: DUAL AGONISTS AGAINST PARKINSON’S

The use of synthetic GLP-1s as a treatment for Parkinson’s shows promise through the use of dual agonists — drugs that act upon two receptors rather than one [40]. Specifically, GLP-1s work closely with glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), a gut hormone that also stimulates insulin secretion and regulates appetite [41]. This dual-receptor activation mimics a more natural hormone response in the body, similar to how the gut normally uses GLP1 and GIP signals together to regulate metabolism and cellular health [42]. In preliminary mouse model studies, DA-CH5 — a dual agonist drug designed to activate both GLP-1 and GIP receptors — stood out for its ability to provide therapeutic effects from the activation of both GLP-1- and GIP-related signaling pathways [43, 44, 45]. Once inside the brain, DA-CH5 appears to act like a ‘smart key’ by turning on only the GLP-1 and GIP switches without inadvertently activating any other systems, unlike insulin and glucagon, which act on systems throughout the whole body [45, 46]. DA-CH5 treatment may also help preserve neurons in the brain region most affected by Parkinson’s, delaying degeneration at least as effectively as existing treatments [45]. Beyond protecting neurons, DA-CH5 promotes processes that clear dysfunctional glial cells from the brain [45]. Typically, specific glial cells called microglia regulate neuroinflammation pathways by increasing inflammation in response to pathogens and by initiating cell death to clear abnormal or damaged cells from the brain

[45]. In Parkinson’s, however, chronic hyperactivity of microglia induces long-term neuroinflammation and triggers a process in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the fatty membranes of neurons [45]. It is suggested that by activating both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, dual agonists initiate signaling processes that protect vulnerable neurons from immune attack, improve mitochondrial energy production, and normalize the breakdown of cellular material, ultimately providing broader neuroprotection than solely GLP-1based drugs [45]. With their wide range of promising effects, dual agonists represent a powerful new direction for Parkinson’s treatment [43, 45].

Although GLP-1 medications were originally developed to treat metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes, emerging research suggests they may also play a valuable role in addressing neurodegenerative diseases [8]. Since they act on the gut-brain axis, reduce neuroinflammation, and protect vulnerable neurons, GLP-1s are being explored as potential disease-modifying therapies for various conditions, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, where current FDA-approved treatments remain largely limited to symptom management [4, 16, 17]. Despite this growing scientific interest, GLP-1 drugs remain widely known for their effects on blood sugar regulation and weight loss, yielding results that have fueled their rapid rise in popularity. Their presence in advertising, social media, and celebrity culture has transformed GLP-1s into a highly commercialized medical phenomenon — often overshadowing their broader, and still largely untapped, neuroprotective potential.

References on page 59.

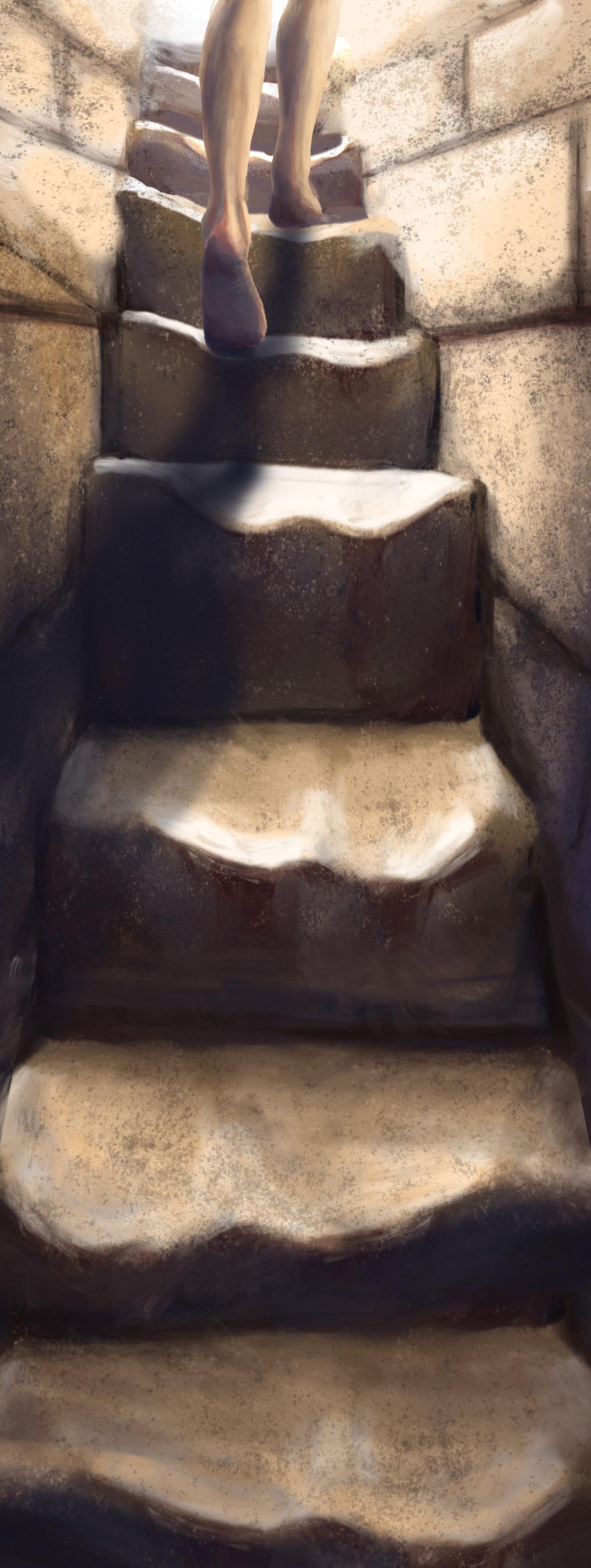

by Lucy Gaffneyboro | art by Cora Thompson

Amy Brown has been out sick from preschool for the past two days. Her parents assumed that her fever and runny nose were due to a common cold. But last night, as Amy’s dad finished tucking her into bed, she suddenly began to twitch violently and lost consciousness. Unbeknownst to her parents, Amy had suffered from a seizure: a transient episode of excessive and often synchronized electrical activity in the brain [1, 2]. When a seizure is provoked by a fever, it is referred to as a febrile seizure, an often benign phenomenon that commonly occurs in children under the age of five [3]. Even though young children frequently get fevers, only 2-5% develop febrile seizures [4]. Most children who have a febrile seizure will fully recover and have no further complications, but others may go on to experience recurrent episodes or chronic symptoms. In some cases, a febrile seizure can evolve into a more serious lifelong condition that impacts everyday life, begging the question:

What are the underlying physiological and genetic factors that can predispose certain children to these chronic disorders?

Every brain is constantly thrumming with electrical activity that strives to regulate the body. Within the brain, cells called neurons transmit information through electrical signals [5]. Every neuron has a membrane potential, a voltage created by the unequal distribution of charged particles called ions across the neuronal membrane [6]. Typically, inactive neurons have a constant voltage called the resting membrane potential [7]. When a neuron is sufficiently stimulated by incoming signals from surrounding neurons, the flow of ions across the membrane changes [8]. If there is enough ion movement to significantly alter the voltage of the neuronal membrane, the cell becomes activated. Signals are then sent to adjacent neurons by chemical messengers called neurotransmitters [8, 9].

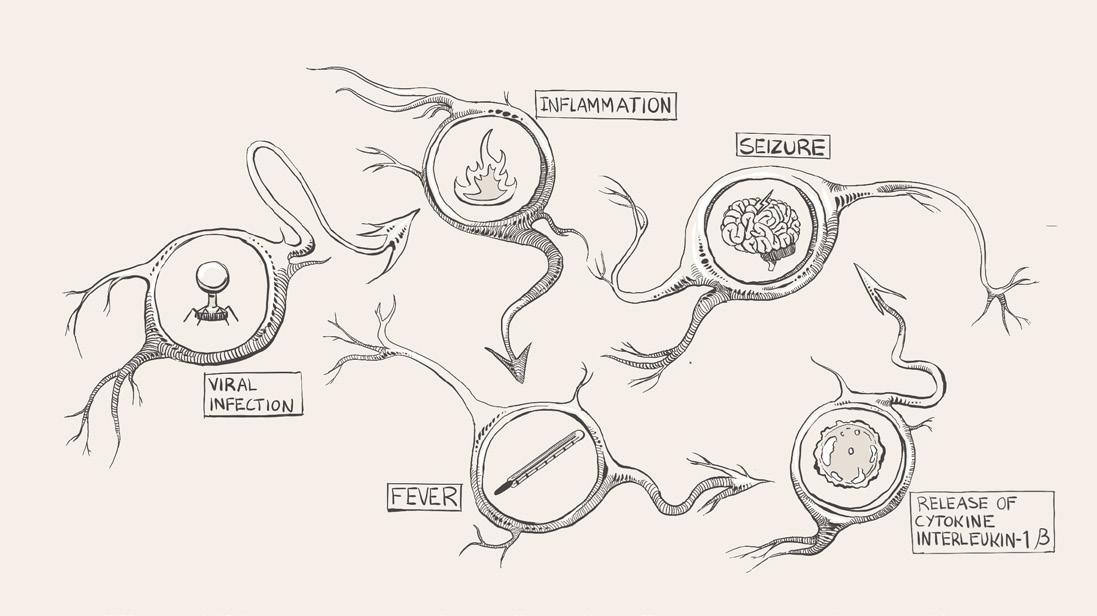

During a seizure, like the one that Amy experienced, the normal pattern of electrical signalling is disrupted [10]. Neurons become hyperexcitable, or overreactive, and are more likely to send out extraneous signals, leading to excessive and irregular electrical firing in the brain that is characteristic of a seizure [11]. All seizures are caused by the disruption of typical neuronal function, but different types of seizures can present with varied symptoms [12, 13, 14]. Some seizures appear more pronounced, potentially including a loss of consciousness, rapid jerking movements, or the body becoming either stiff or floppy [15]. These types of seizures are often seen in medical dramas. However, some seizures present more subtly, manifesting as occasional slight muscle twitching, a prolonged blank stare into space, or both [15]. Most seizures only last a few minutes [15]. If a seizure lasts longer than five minutes or consists of multiple recurrent seizure episodes without regaining full consciousness, it is classified as status epilepticus, a serious condition that requires immediate hospitalization [16, 17]. During a viral infection, such as the flu, proteins called

antibodies detect a virus in the body and trigger the immune system to respond [19]. Through a process called inflammation, immune cells are sent to attack the virus [20]. Inflammation stimulates the release of cytokines, which are small proteins that play many roles in the body and can indirectly affect how likely neurons are to become activated [20]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines ramp up immune activity to destroy the pathogen, whereas anti-inflammatory cytokines promote healing and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine pathways [20, 21]. Both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are present in every immune response, and an equilibrium of cytokines is crucial to a healthy and functional immune system [20, 22]. Equilibrium does not necessarily mean completely equal levels of each type, but rather an ever-changing harmonization between the two [22].

A common byproduct of inflammation is fever, an immunological defense that limits bacterial and viral proliferation [23]. Although a fever defends against unwelcome pathogens, over time, the continuous immune response can wreak havoc by disrupting the body's carefully calibrated equilibrium [24]. During a fever, pro-inflammatory cytokines are released throughout the body [25]. For example, interleukin-1β increases the production and release of glutamate, a neurotransmitter that increases the likelihood of a neuron becoming activated [26, 27]. As glutamate levels rise, weak stimuli that do not typically change the membrane voltage end up prompting a neuronal response [14]. If enough hyperexcitable neurons are concentrated in one area of the brain, erratic electrical activity can compound and lead to a febrile seizure [28, 29]. If a febrile seizure lasts longer than five minutes, it is referred to as febrile status epilepticus (FSE) [30]. Keeping the possibility of FSE in mind, Dr. Bird walks into the exam room and consults Amy's chart. He sees that she had a high fever and tested positive for a viral infection. He considers her age and concludes that she had a febrile seizure, a

seizure brought on by a fever greater than 100.4°F [13, 31]. Young children are more vulnerable to febrile seizures than other age groups since their nervous systems are still developing [29]. Given that this was Amy's first seizure, Dr. Bird explains to the Browns that this seizure increases her likelihood of having another.

Febrile seizures and their associated conditions sometimes have no known cause, but they can also be the result of a constellation of factors that make one brain more susceptible than another [13]. A family history of febrile seizures increases an individual’s chance of having one themselves, suggesting an underlying genetic basis for febrile seizure development [25, 32, 33]. Amy's mother also had a febrile seizure as a child, which Dr. Bird noted in his assessment [34]. One gene likely responsible for some of the hereditary patterns of febrile seizures is SCN1A, which helps control the construction of voltage-gated channels: special proteins that help modulate the membrane potential of a neuron [35]. A mutation in the SCN1A gene disrupts the flow of sodium ions through these channels, decreasing the brain’s ability to inhibit neurons and subsequently increasing the potential for neuronal hyperexcitability [35, 36, 37]. SCN1A mutations, therefore, elevate a person’s likelihood to experience a febrile seizure during a fever [36, 37]. Genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) is associated with mutations in the SCN1A gene and is an inherited disorder that encompasses several febrile seizure-related conditions [38, 39]. Around half of all children with GEFS+ have at least one parent with the same condition [39]. In addition to febrile seizures, individuals with GEFS+ experience febrile seizures plus (FS+), which are seizures that occur outside of the typical febrile seizure age range and are not caused by fevers [33, 40]. While most children will outgrow febrile seizures, children with GEFS+ will continue to have both recurrent FS+ and non-febrile seizures past age six [39]. In the next room over from Amy, Dr. Bird sees another one of his patients: Luke, an eight-month-old recently admitted for Dravet syndrome. A severe subtype of GEFS+, Dravet syndrome, affects one in 15,700 people, and its onset is often provoked by fevers in infancy [35, 41, 42]. The SCN1A mutation predisposes Luke to unnecessary pro-inflammatory responses; during a fever, his brain releases more pro-inflammatory cytokines than necessary [43]. In addition to fever, Dravet syndrome seizures can also be triggered by acute stress, sudden changes in temperature, or excitement as a

result of SCN1A gene dysfunction [44]. Despite similarities in the underlying mechanisms of febrile seizure and Dravet syndrome, the latter seizures are harder to regulate and treat because the threshold for neuronal excitement is lower [45, 46].

When a status epilepticus seizure or an FSE rages for several minutes, there is a chance that the harm caused to the brain can be irreversible, leading to lifelong medical complications [47, 48]. For example, temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is caused by abnormal electrical signaling in the temporal lobe, a brain region crucial to language, emotion, visual recognition, and memory [49, 50, 51]. In the long term, TLE can cause cognitive decline and even the development of disorders such as depression and anxiety [52]. Additionally, TLE can negatively affect executive functions such as memory, planning, and attention, making it more challenging to maintain social relationships, manage time, and control impulses [52, 53]. Within the temporal lobe is the hippocampus, a structure integral to short and long-term memory, spatial awareness, and emotional memory [54]. Damage to the hippocampus can result in memory impairment [55]. Recent research has investigated the relationship between the structure and orientation of the hippocampus and the occurrence of FSE [56]. Hippocampal malrotation (HIMAL) is a condition that describes an abnormally positioned hippocampus, and it can be an indicator of abnormal brain development that can predispose individuals to seizures [57]. Individuals could be born

with HIMAL, or HIMAL could arise after a seizure [57]. HIMAL is predominantly observed in patients who have had an FSE as opposed to those who have had a febrile seizure, and it may play a role in the development of TLE [57]. Reduced hippocampal size also predisposes individuals to febrile seizures and FSE development, and children with FSE have higher rates of internal hippocampal injury; however, it is unclear whether the damage preceded the seizure or whether the seizure caused the damage [25, 58].

Dr. Bird's schedule is packed. His next patient is a seven-year-old boy named Harry, who was previously healthy without any neurological illnesses. One week ago, Harry developed a fever and a sore throat, so his parents brought him to be seen by his primary care doctor, who gave him medicine to treat his respiratory infection. After many days, some of his symptoms resolved, but his fatigue and fever lingered, and Harry was admitted to the hospital. Several days into his hospital stay, he started having refractory status epilepticus, which are seizures that cannot be stopped after treatment with two or more medications [33]. Dr. Bird and his team concluded that Harry was suffering from febrile-infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). FIRES is a chronic, sudden-onset epilepsy condition that arises after a fever caused by an infection [59]. The key difference between FIRES and an FSE or febrile seizures is that FIRES is often accompanied by lifelong after-effects [60]. FIRES can cause refractory status epilepticus that arises between twenty-four hours to two weeks after the onset of a fever, just like Harry experienced [61]. A fever is a marker of the body’s immune system protecting against pathogens with inflammation, but excessive inflammation in the brain can induce seizures, which in turn provoke more inflammation [23, 62]. Individuals with FIRES are often found to have increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β [63]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines trigger the release of even more pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to a cytokine storm [64]. The massive increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines causes increased excitability of neurons and subsequent exacerbation of seizures [65, 66]. FIRES is most commonly observed in children of elementary school age, like Harry, but it can affect individuals from infancy to adolescence [33, 67]. Patients continue to suffer from progressively debilitating seizures throughout their lives; damage to their brains is significant [68]. As a result, FIRES can cause neurological symptoms like memory loss and behavioral problems [69].

When Amy arrived at the hospital, she was first given medication, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, to control her fever [4, 42, 70]. If the seizure had been an FSE, the dose of acetaminophen would have been followed by a depressant medication such as a benzodiazepine to slow the nervous system by preventing hyperexcitable neuronal firing, which terminates the seizure [30]. If seizure activity hadn’t stopped after the first dose of benzodiazepine, additional doses would have been given [30]. Most children who have a seizure will experience no long-term complications, but immediate medical attention is crucial to ensure a full recovery [3, 71]. Unlike febrile seizures and FSE, FIRES has a different treatment plan: cytokine-directed immunotherapy (CDI), which uses the body's own molecular components and processes to modulate cytokine activity [28, 72]. CDI is individualized: One person’s treatment could focus on increasing levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines while another person’s could focus on increasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [72]. CDI is used for a variety of conditions, and it can be incredibly successful in treating FIRES by targeting specific cytokines that are key to regulating inflammation [28, 72]. During Harry's hospital stay, he was treated with a CDI drug called Anakinra IL-1 to block pro-inflammatory IL-1 receptors [28, 72]. When IL-1 receptors are blocked, inflammatory cytokines cannot bind to them, which reduces seizure propagation [73]. Anakinra IL-1 can be used over long periods of time for chronic inflammatory conditions, and Harry will likely receive this medication for up to a year [74]. Another common drug used for CDI is Tocilizumab, an antibody that binds to a different pro-inflammatory receptor site and prevents that pro-inflammatory cytokine from further activating more immune cells [28].

Amy, Luke, and Harry all had fevers, and their haywire immune responses produced a myriad of side effects, ultimately resulting in febrile seizures. Dr. Bird's patients showcase how febrile seizures range from benign and temporary to life-threatening and chronic. Pronounced seizures like the ones that Luke and Harry experienced are well-documented in the media, but their prevalence on page and screen belies their relative rarity. More common instances of seizures, such as Amy's febrile seizure, are shorter, less consequential, and less dramatic; however, they can still be traumatic and alarming to both patients and their family members. All seizures are the result of the

same core physiological vulnerability: a brain temporarily pushed to the brink by neuronal hyperexcitability. In the cases of Amy, Luke, and Harry, their brains were also the victims of fever and inflammation, but the extent to which genetics and family history contributed to their conditions remains unknown. Although Dr. Bird is fictional, real-life physicians treat people who experience brief febrile seizures and others with lifelong neurological challenges. These physicians must effectively communicate with patients and families while balancing the nuances between each condition to provide the best treatment.

References on page 60.

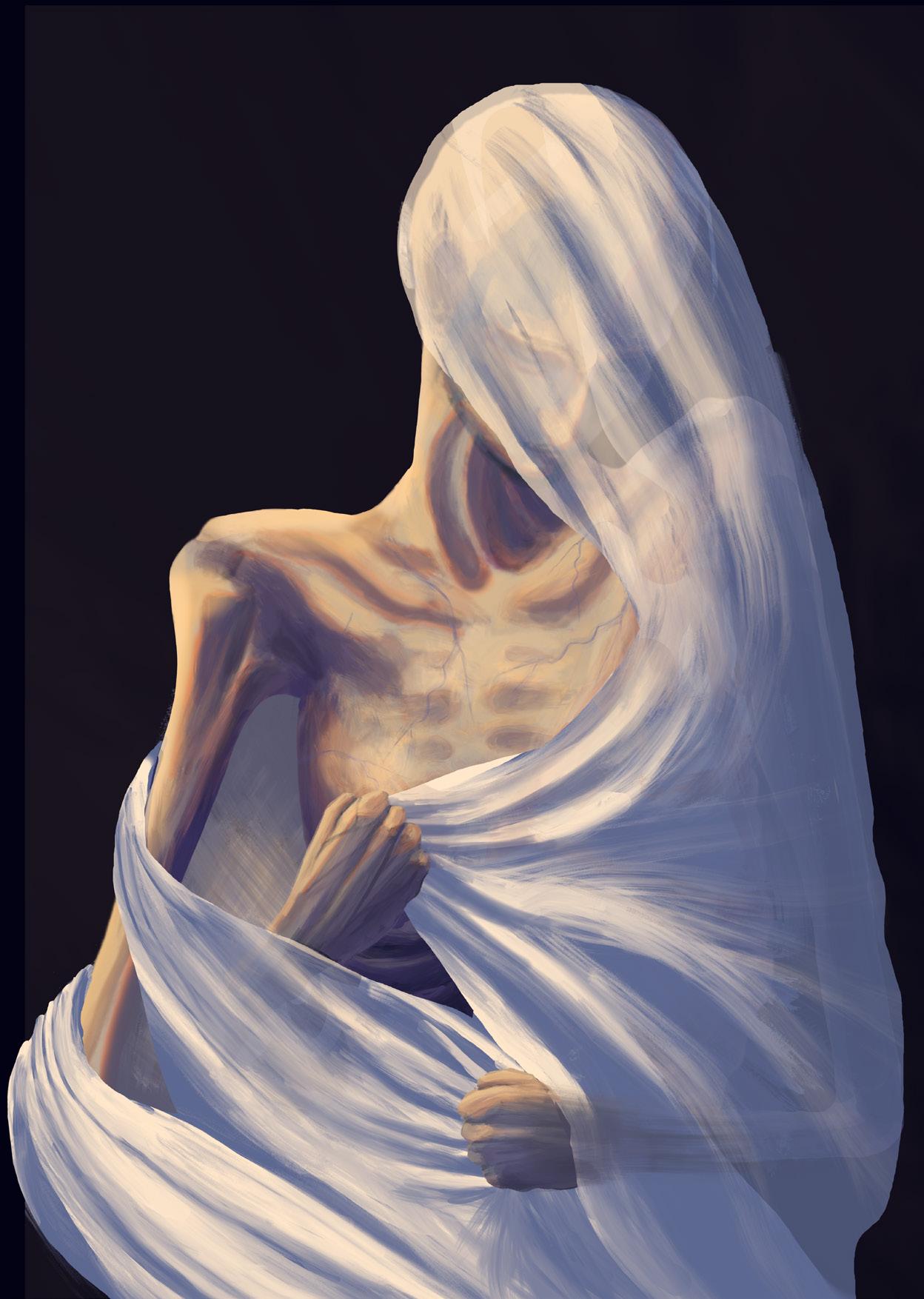

by Samuel Jacobs | art by Emily Holtz

Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are serious, life-threatening medical conditions that are often misunderstood as mere ‘vanity disorders’ due to an excessive preoccupation with body shape and weight [1, 2]. The most widely known kind of anorexia nervosa is the restrictive subtype, characterized by the persistent restriction

of food relative to what an individual’s body needs [2].

On the other hand, bulimia and the binge-purge subtype of anorexia nervosa (AN-BP) are characterized by recurrent binge-eating episodes accompanied by purging behaviors, including vomiting, fasting, excessive exercise, or misuse of laxatives and diuretics [2].

The cycle of bingeing and purging is a behavioral loop that briefly relieves emotional distress, but ultimately reinforces harmful eating patterns [3, 4]. Individuals with bulimia may eat large amounts of food over a short period and feel unable to stop [3]. These binges are often followed by intense guilt or discomfort that compels the individual to engage in purging behaviors aimed at preventing weight gain [3, 5]. Patterns of restriction in anorexia nervosa and binge-purge in bulimia/AN-BP can both cause distinct structural alterations within the brain [6]. Specifically, physical changes can occur within neural circuits, the pathways between different brain regions [6]. Through the modification of neural circuits that underlie eating habits, behaviors can become permanently altered, contributing to the dangerous long-term nature of eating disorders [6]. Even after recovery, many individuals continue to experience residual symptoms, rather than a definitive return to a pre-disorder baseline [7]. Due to this, eating disorders have high relapse rates, and individuals in recovery remain vulnerable to returning to destructive behaviors [8, 9]. As a result, they could suffer from the long-lasting psychological and physical effects of these disorders for the rest of their lives [10, 11, 12].

Individuals with bulimia have immense difficulty shifting their thinking away from binge-purge behaviors, even when these actions no longer provide a sense of reward or satisfaction [13]. In fact, these behaviors can persist despite the unpleasant consequences, ranging from emotional distress to dental decay [3, 14]. The brain relies more on ingrained harmful behaviors than flexible responses, such as recognizing

hunger and fullness cues, eating regularly, or seeking emotional support [15]. The flexible responses require conscious reflection rather than thoughtless reaction [15]. Over time, repeated responses strengthen the specific neural connections responsible for these behavioral reactions, creating a mental ‘shortcut’ that makes binge-purge routines habitual and difficult to interrupt [15]. So, when feelings of shame or loss of control hit after bingeing, a person might automatically purge as a way to ‘undo’ the experience, even if they no longer believe it actually helps [3, 13]. If purging is not an option, individuals may struggle to figure out what to do next, since the brain pathways that normally help them move from emotional distress to flexible problem-solving are not communicating efficiently [15].

While bulimia is driven by compulsive reward-seeking through binge-purge behaviors, anorexia nervosa is driven by reward-seeking through rigid control and avoidance of foods [16, 17]. However, both share a fundamental disruption in the neural circuits underlying reward learning and habit formation [16, 18].

Similar to bulimia, the reward system of an individual with anorexia nervosa becomes less responsive to ordinary pleasures and more attuned to the sense of control that comes from restriction and the pleasure created from this control [19]. For example, a person with anorexia nervosa may avoid high-calorie and high-fat foods or adhere to strict meal rituals [17, 20]. The more a person restricts their food intake, the more distressing normal eating patterns can feel, whereas avoiding food can feel calming or purposeful [19, 21]. Once a particular behavior has been reinforced, such as food restriction, individuals with anorexia nervosa tend to persist in that pattern even when it starts causing life-threatening health effects like heart and blood-vessel complications or bone deterioration [21, 22, 23, 24]. This inflexibility is a characteristic of the restrictive and ritualized nature of eating behaviors in anorexia nervosa [19].

In a healthy brain, dopamine serves as a chemical messenger that signals which experiences are rewarding, thereby motivating repeated behaviors [13]. The brain’s reward circuit relies on dopamine as a central component that guides decision-making and reinforces learning [25]. When a behavior, such as maintaining a daily calorie deficit, yields a more positive result than expected — for example, alleviating discomfort or expediting weight loss — dopamine levels increase, leading to behavior reinforcement [26]. Conversely, when a behavior, such as unintentionally overeating, turns out worse than expected and prompts feelings of discomfort, dopamine levels drop, teaching the brain to avoid this behavior in the future [13, 25]. A ‘two-stage’ model can be used to describe dopamine’s integral role in reinforcing anorexia nervosa [27]. First, dopamine activity may increase in response to dieting and excessive exercise, producing a sense of control and success that reinforces food restriction [27]. In the second stage, prolonged starvation lowers overall brain dopamine levels, making the dopamine receptors hypersensitive [27]. Consequently, a normal burst of dopamine from regular eating can feel abnormally intense, triggering an anxiety response instead of a pleasurable one [13, 27]. This heightened dopamine sensitivity in anorexia nervosa illustrates why normal eating can feel uncomfortable or anxiety-provoking, helping explain how restriction becomes reinforced even though it is ultimately harmful [26]. In this model, dopamine not only contributes to the onset of anorexia nervosa but also sustains the duration of the disorder by transforming short-term relief into unhealthy routines [27]. Additionally, binge-purge behaviors in bulimia may also engage dopamine signaling in a similar pattern to anorexia nervosa [28]. In bulimia, habit and reward-related brain circuits are dysregulated in a manner that promotes impulsive, reward-seeking behavior like bingeing, associated with decreased dopamine receptor binding [13]. Bulimia appears to be linked with lower dopamine sensitivity, so larger amounts of food are often needed to generate a noticeable sense of reward or satisfaction [26]. Thus, both disorders exhibit maladaptive patterns in the same underlying reward circuitry [30].

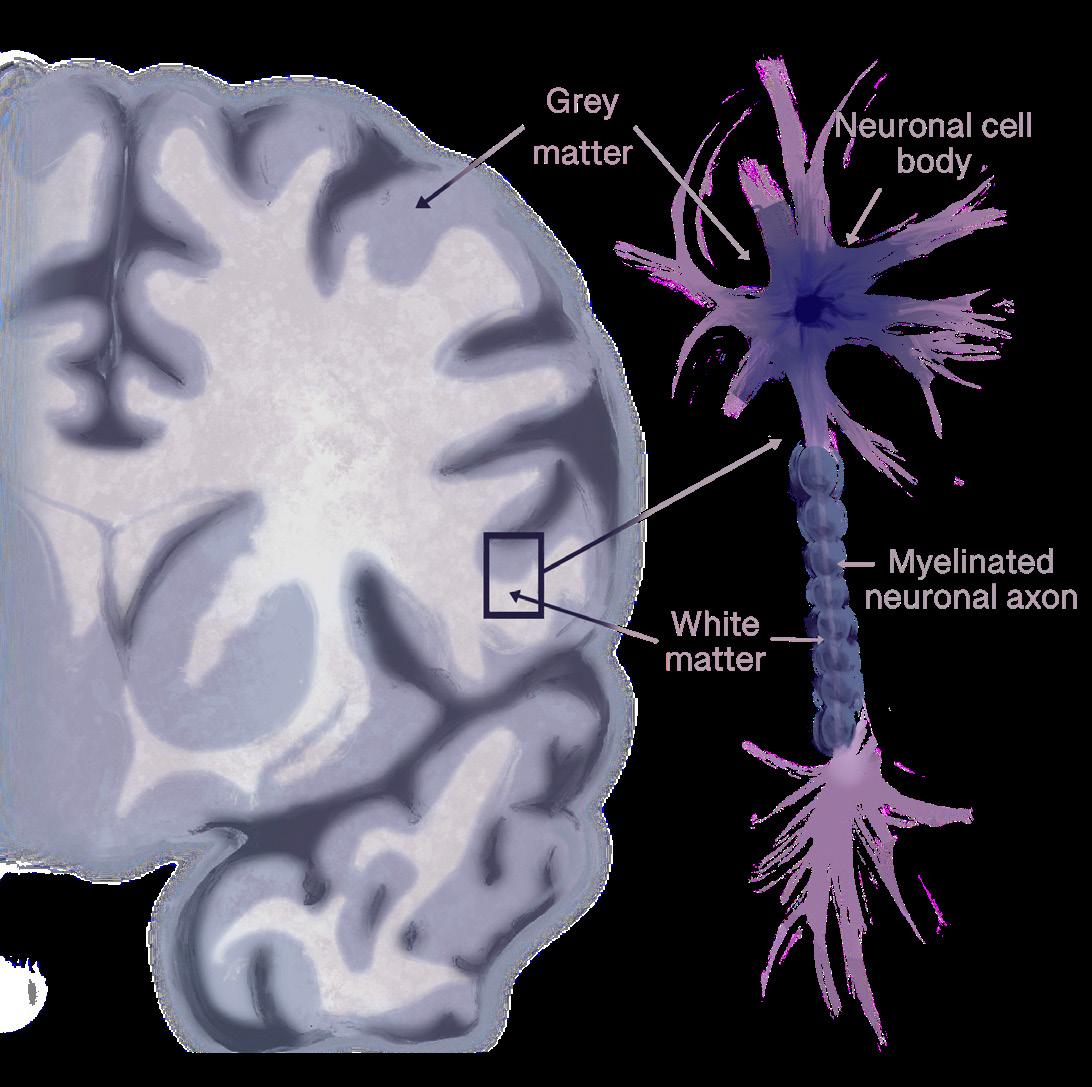

Eating disorders leave their mark not only on behavior but within the brain itself, where structural changes leave a lasting neurobiological impact [29, 30, 31]. The brain is composed of two main types of tissue: gray matter and white matter [32, 33]. Gray matter contains neurons that handle thinking and processing, while white matter consists of bundles of axons — long, slender projections of neurons that conduct electrical impulses away from the cell body — that are coated in an insulating fatty sheath, fostering quick communication between distant brain regions [32, 34, 35]. In anorexia nervosa, the white matter begins to thin due to malnutrition, which reduces coordination between areas that regulate reward, emotion, and self-perception [36, 37]. Think of white matter as a network of highways connecting different cities: when the roads are well-maintained, traffic flows smoothly, and messages are delivered efficiently to their intended destinations. Thinning of axons in these pathways is similar to potholes, lane closures, or damaged bridges on the highways — signals slow down, get misdirected, or fail to reach their destination, which can disrupt coordination between brain regions that regulate reward, emotions, and self-perception [37]. In the brain, these disruptions in physical wiring and coordinated regional activity represent a breakdown in overall connectivity [6]. People with anorexia nervosa experience reduced connectivity, meaning weaker communication between brain circuits like the default mode

network, which is involved in self-focused thinking, and the salience network, which helps the brain detect important emotional or bodily signals like hunger or fullness [37]. Furthermore, loss of white matter fibers has been found in pathways connecting emotional and decision-making centers of the brain [37]. Reliance on rigid, well-worn habits over flexible decision-making can lead to sudden spikes of fear or distress around eating, making even small changes — like adding one new food to a meal — feel impossible [17]. Some white matter abnormalities improve during long-term weight restoration, while others persist and are associated with illness duration [18]. A longer illness duration predicts enduring white matter deficits, suggesting that the longer anorexia nervosa remains untreated, the more persistent these changes become [38]. Over time, structural disruptions may deepen and become harder to reverse, making early intervention critical to recovery [39].

In contrast, bulimia is characterized by abnormalities in brain regions that support habit formation and reward regulation [18, 38]. Disrupted communication within those regions can harm reward evaluation abilities and behavioral control [38]. Structural disturbances may contribute to the compulsive nature of binge-purge cycles and the difficulty of disengaging from them [40]. Moreover, bulimia is linked to structural alterations in brain regions that regulate reward, self-control, and emotional processing [18]. Abnormalities include reduced gray-matter volume or altered connectivity in key areas involved in evaluating rewards and regulating internal bodily sensations like hunger, fullness, and taste [18, 41]. Changes in underlying brain structure may reinforce maladaptive patterns of eating behavior and make it harder to resist urges to binge or purge [18]. Taken together, both anorexia nervosa and bulimia are marked by structural and connectivity disturbances that reinforce maladaptive behaviors; anorexia nervosa shows disrupted communication between self-perception and control networks, while bulimia shows dysfunctional integration within reward and habit systems [18, 23, 38].

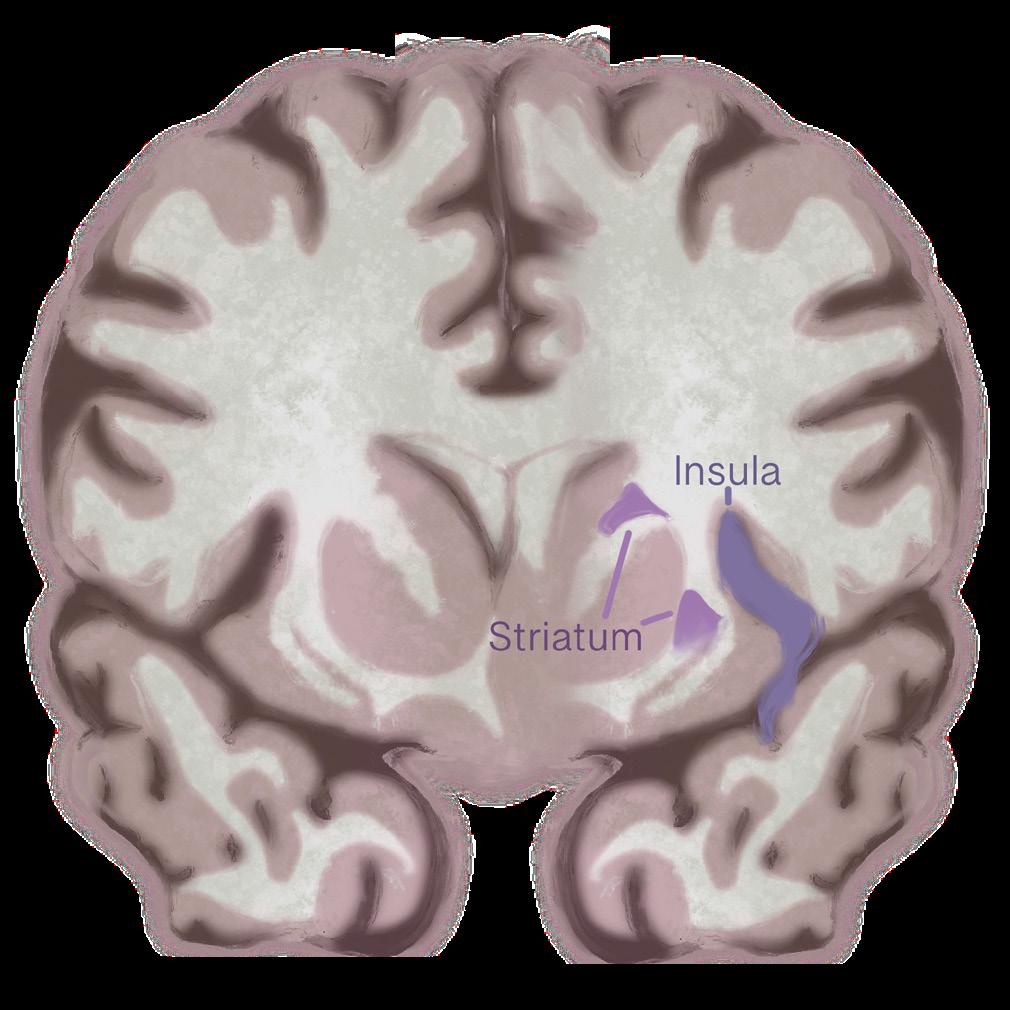

Structural changes in a brain region called the insula may drive binge-purge behavior in bulimia. Similar to anorexia nervosa, bulimia also affects the insula [13]. People with bulimia have less gray matter in the front part of the insula. Reductions in gray matter may

indicate a decrease in healthy neurons in a given area, and that the insula does not function as efficiently when integrating emotions with physical urges or sensations in bulimia. Weakened integration could make it harder to regulate powerful urges to binge or purge, since the brain struggles to align emotional experiences with body signals. Disrupted activity in different subregions of the insula also suggests that cognition-emotion coordination is impaired, contributing to the impulsive, emotionally driven eating behaviors seen in bulimia. These findings highlight the insula’s key role in linking emotional states with bodily urges, showing how its dysfunction may fuel the binge-purge cycle [13]. Beyond structural changes in the insula, bulimia also disrupts communication between brain re gions, particularly within circuits that link motivation, habits, and decision-making [38]. A key structure in this process is the striatum, a deep-brain region involved in learning what feels rewarding and shaping habitual behaviors [38]. In people with bulimia, the striatum shows abnormal communication with other regions such as the prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and sensorimotor areas — regions responsible for planning, emotional regulation, and body awareness. A miscommunication appears to dis rupt the balance between the brain’s reward and control systems, which may underlie the recurring binge–purge cycle. When these systems fail to coordinate properly, urges to binge or purge can override rational decision-making, making the behavior feel automatic and difficult to stop [38].

symptoms: those with more pronounced connectivity issues tend to experience stronger binge–purge urges and more emotional instability [42]. These findings suggest that bulimia involves widespread disruptions not only in reward and control circuits, but also in the broader networks that govern attention, self-control, and emotional regulation [38, 42].

Large-scale brain region networks that coordinate attention, emotion regulation, and self-control also appear to function differently in bulimia [42]. These networks, such as the fronto-parietal network (FPN) and the cingulo-opercular network (CON), are like the brain’s ‘command centers’ that help people stay focused on goals, manage impulses, and adapt their behavior [42]. The FPN supports flexible control and attention, while the CON helps maintain task focus and emotional stability over time [42, 43]. In bulimia, these large-scale networks show decreased connectivity, indicating weaker functional communication within and between them [42]. The degree of this disruption is linked to the severity of a person’s

Just as the brain’s wiring patterns can shape habits and emotions, its chemical composition also plays a crucial role in the development and persistence of eating disorders [13]. Chemicals known as metabolites are small molecules that help neurons produce energy, communicate effectively, and repair themselves [13]. When these chemical systems are disrupted, the brain may struggle to regulate hunger, reward, and emotional balance [13]. Reduced levels of metabolites in the insula may indicate that the neurons are functioning, but not at full capacity [41]. Weakened neural signaling in the insula may contribute to the disconnect that many people with anorexia nervosa experience from their own bodily cues, making hunger feel confusing or even anxiety-provoking rather than natural [41]. Lower levels of the metabolite N-acetylaspartate (NAA) are strongly linked to greater concern about weight and body image, and therefore, these chemical changes may reinforce obsessive self-focus and distorted body perception [41]. Importantly, these chemical changes may not be permanent. As individuals begin the recovery process, metabolite levels in some regions, such as the insula, begin to return to typical ranges [41]. At this point, the brain can regain chemical balance with appropriate treatment and nutrition, thereby promoting the restoration of hunger cues [44]. However, many individuals still report lingering difficulties with body image, suggesting that emotional and cognitive patterns often return to baseline more slowly than brain chemistry [41]. Recovery from anorexia nervosa is both physical and psychological, requiring time for both the brain and self-perception to return to baseline [41].

In bulimia and AN-BP, brain chemistry follows a somewhat different pattern from anorexia nervosa [45]. Both disorders involve abnormal activity in brain regions responsible for reward, self-control, and emotional awareness, but the underlying neurochemistry is not identical. People with AN-BP showed reduced levels of NAA and myo-inositol — chemicals that support healthy brain cell membranes and energy use — in the prefrontal cortex, a region involved in impulse regulation, and the occipital lobe, an area involved in visual information. This could mean that the brains of individuals with AN-BP are less efficient at regulating impulses and integrating visual information related to body image [45]. Conversely, people with bulimia do not show the same reductions in certain brain chemicals seen in anorexia nervosa, suggesting that their symptoms may arise from a different pattern of brain activity related to how rewards are processed, rather than from widespread reductions in brain efficiency [45]. Together, these findings suggest that while both anorexia nervosa and bulimia affect overlapping networks in the brain, each disorder uniquely disrupts the brain chemistry; therefore, effective treatment might need to target not just behavior, but also the specific neurochemical imbalances underlying each condition [41, 45].

Eating disorders can be treated through pharmacological, psychological, or neurological methods [46, 47, 48]. Anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medications treat anorexia nervosa and bulimia by reducing co-occurring depression or anxiety that reinforce restrictive behaviors, and are often used in tandem with psychotherapy for further symptom reduction [28, 46, 49]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-ED) is the most widely supported psychological approach across eating disorder diagnoses [47]. CBTED targets the cognitive and behavioral mechanisms that sustain disordered eating — such as strict dieting, over-valuation of shape and weight, and maladaptive emotion regulation [47]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for anorexia nervosa (CBT-AN) helps individuals recognize and modify patterns that maintain restriction or obsessive focus on weight [50]. Patients who receive CBT-AN show greater weight gain and larger reductions in eating disorder symptoms compared to standard care [50]. Cognitive-training programs that aim to dissuade urges to binge-purge and strengthen inhibitory control are showing promise in reducing compulsive eating patterns in bulimia as well [16, 45]. CBT-ED protocols address the specific psychological and neurobehavioral mechanisms that

maintain anorexia nervosa and bulimia, regardless of whether the presentation is restrictive or bingepurge [51].

Similarly, emerging therapies that directly target brain circuits offer another avenue for treating anorexia nervosa and bulimia [48, 52]. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive technique that applies a mild electrical current to specific brain areas, aiming to improve cognitive control, emotional regulation, and food intake [49, 53, 54]. Depressive symptoms, which often co-occur with anorexia nervosa and bulimia, may be reduced by tDCS [48]. While still experimental, these interventions aim to strengthen the brain circuits that are disrupted in anorexia nervosa and bulimia [16, 48, 52]. In anorexia nervosa, tDCS helps patients regain more flexible responses to food and emotional cues, similar to findings reported in bulimia [48, 52]. After only a few sessions of tDCS, individuals with bulimia reported suppression of binge-purge urges and increases in self-regulatory control [52]. Multi-session trials would be necessary to validate this approach as a clinical treatment method for bulimia; however, the findings to date have been positive [52]. By targeting the neural underpinnings of the disorder, neurofeedback and brain-stimulation techniques could eventually complement traditional therapy and behavioral interventions.

While both anorexia nervosa and bulimia share core features of disrupted eating behaviors, body-image disturbance, and altered brain processes, the neurobiological pathways that sustain each disorder diverge in meaningful ways [13, 19]. Anorexia nervosa is characterized by extreme food restriction, heightened dopamine sensitivity, rigid habit formation, and structural white-matter and connectivity changes that reflect a brain entrenched in avoidance and control [25, 27, 37]. Bulimia and AN-BP, however, are marked by binge-purge cycles, reduced dopamine responsiveness, impulsive reward-seeking, and alterations in habit and reward-based circuitry [13, 28, 30]. Structural and functional brain alterations in eating disorders continue even after physical recovery, indicating persistent neurobiological vulnerability even after symptomatic improvement [29, 30]. Therefore, recovery not only involves returning to normalized eating behaviors but also restoring healthier brain circuit function and encouraging flexible behavioral patterns [41, 44]. Treatment should be tailored to these neural profiles: for bulimia, interventions may

focus on disrupting maladaptive habit loops and retraining reward sensitivity, while for anorexia nervosa, strategies may focus on targeting dopamine or metabolite-related pathways to rewire the brain’s rigid control systems toward adaptive regulation [16, 26, 27, 42]. Early intervention is critical because the longer pathological reward or habit patterns persist, the more entrenched and difficult they become to reverse [38, 39]. By viewing anorexia nervosa and bulimia not just as psychiatric disorders, but as disorders of neural circuitry and learned behavior, we gain a clearer framework for precise treatments and innovative therapeutic approaches [18, 52].

References on page 64.

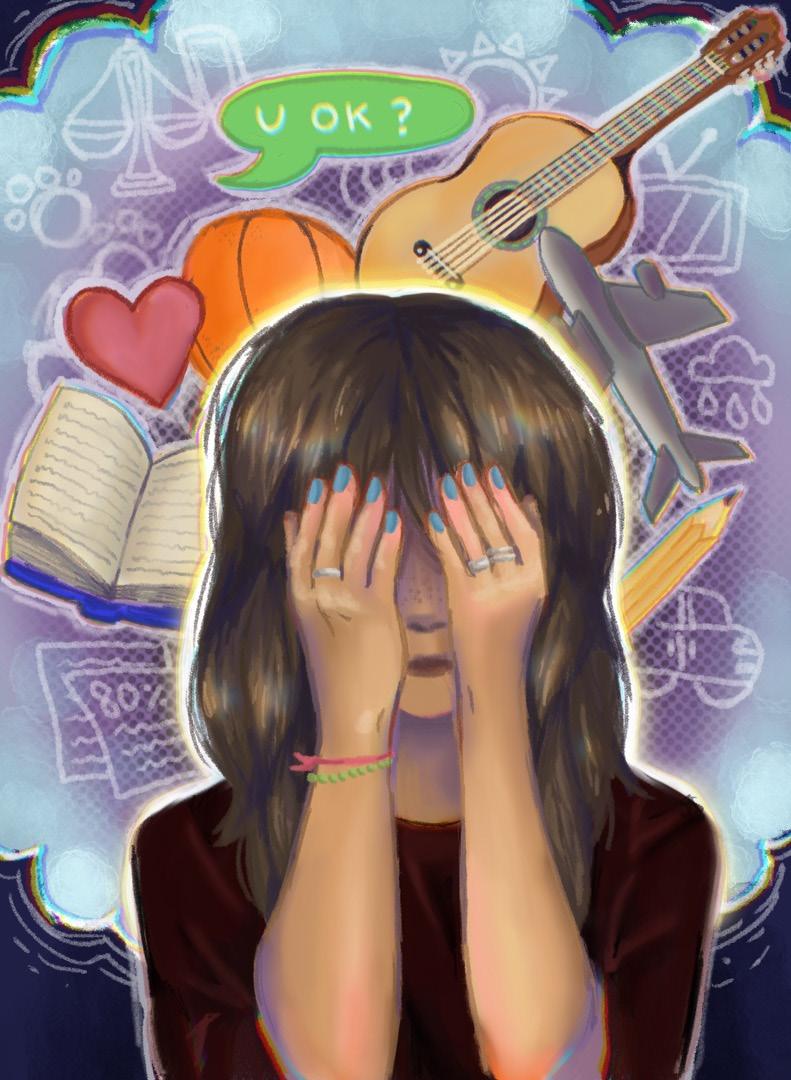

by Joseph Lippman | art by Racine Rieke

When you picture somebody burning the midnight oil, what comes to mind? An exhausted college student? A nurse during the COVID-19 pandemic, overworked and underappreciated? Chances are, if you have ever overexerted yourself for a period, you are probably familiar with the feeling of burnout. Burnout is commonly thought of as psychological — a way to describe extreme mental exhaustion from being overly stressed [1, 2]. Prolonged exposure to stress, known as chronic stress, can result in feeling burnt out and affects much more than simply our mental state [1, 3]. The impacts of this exhaustion extend to physical ailments such as high blood pressure and obesity [4, 5, 6]. It is vital to understand how burnout affects the mind and body in order to combat its debilitating effects, especially for those who work in consistently high-stress environments.

Imagine a student who is nervous about their upcoming midterm exam. The content feels difficult to understand, they have little time to study, and the exam accounts for a massive percentage of their grade. Needless to say, the student is experiencing a good amount of stress. Stress is a physiological and psychological response that is prompted by a perceived threat, causing worry and increased focus on a given task [7, 8, 9]. While it has an unpleasant reputation, stress in moderation allows us to function efficiently [10, 11]. For example, stress will compel the student to manage their time and focus on studying for their midterm [12, 13, 14]. Studying for a midterm is an example of an acute stress response, characterized by short bursts of stress that allow the individual to push past the stressor [10, 12, 14]. Healthy and unhealthy amounts of stress are best measured by utilizing a principle called the Yerkes-Dodson law, which stipulates that a moderate amount of stress is ideal for optimal performance [15, 16]. This principle suggests that too little stress can lead to insufficient motivation, while excessive stress can lead to anxiety and a decline in performance [15, 16].

Chronic stress occurs when the body is overloaded with a repeated or constant stress response [17, 18, 19]. A student may be struggling with chronic stress if they are constantly worrying about their exam to the extent that they are unable to focus or commit to productive studying [20, 21]. Individuals working under excessive workloads and high emotional demands, such as healthcare workers in hospital settings, commonly experience chronic stress [3, 22, 23]. Chronic stress overwhelms the body’s response to acute stressors, interrupting the process of returning to a resting state and prolonging the symptoms of stress [17, 18]. For instance, if the student experiences chronic stress from being spread too thin

with commitments and is unable to study efficiently, their chronic stress can result in burnout [3, 23]. In burnout, an individual might feel severe emotional exhaustion, lack of personal achievement, and general cynicism [3, 23, 24]. Historically, the association of burnout with stressful work environments has led many to believe that burnout is simply psychological [1, 2, 14]. This is, however, an incorrect assumption, as burnout is also physiological [14, 25, 26]. In the case of burnout, the physiological symptoms of the typical stress response, such as increased blood pressure and exhaustion, become prolonged and can potentially lead to harmful long-term health consequences [14, 25, 26]. Therefore, it is important to understand the mechanism of the typical stress response and what changes when it becomes chronic [26, 27].

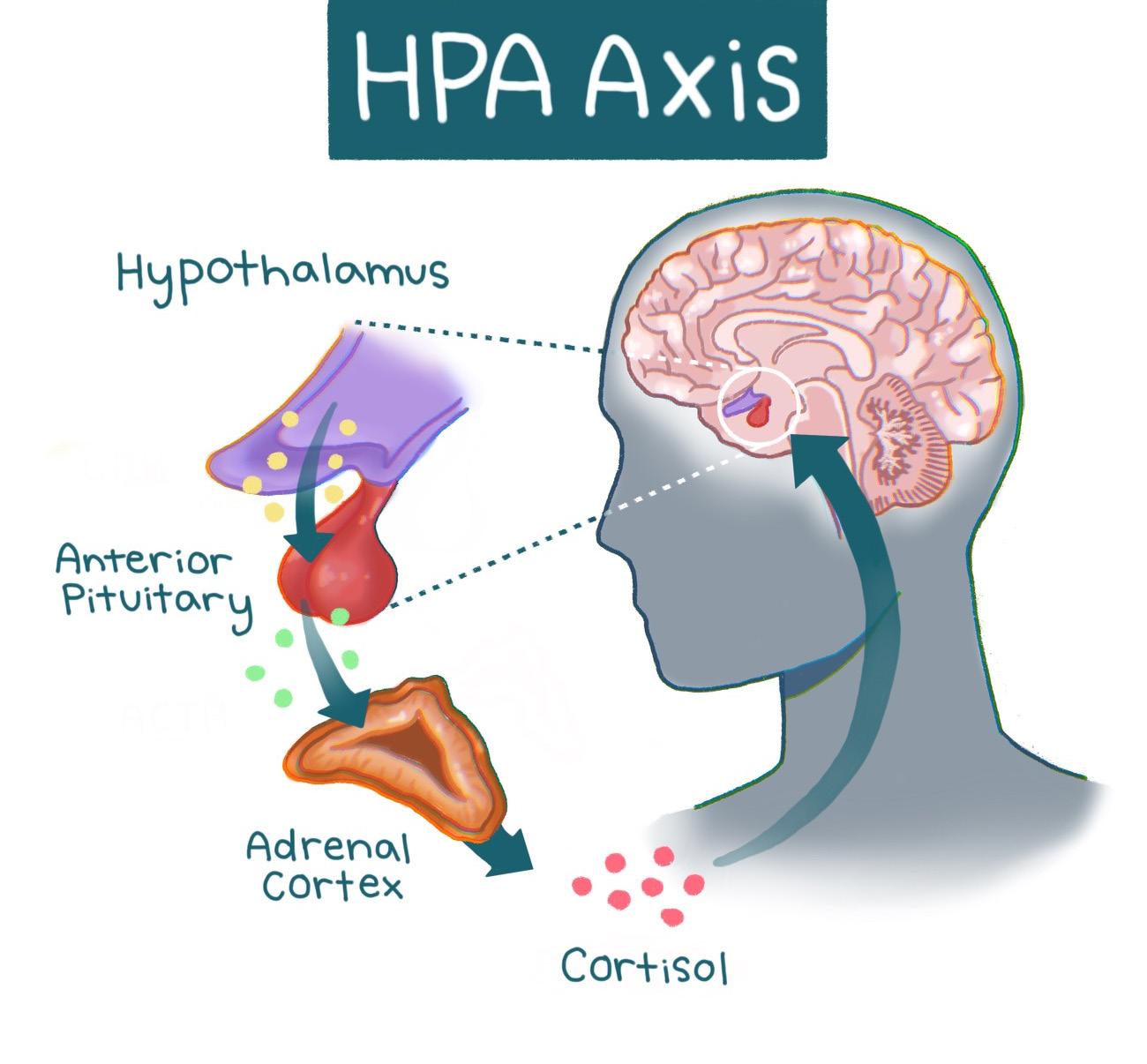

Stress responses are mediated by a pathway in our brain and body known as the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis [11, 28]. At the onset of a stressful event, the hypothalamus is activated [10, 11]. The hypothalamus is a structure in the brain responsible for multiple regulatory functions and links the brain’s emotional centers with the major structures involved in the stress response [28, 29]. Activation of the hypothalamus triggers a cascade of hormones — chemical messengers that mobilize the energy and resources needed for the body to overcome a stressor [11, 28]. The cascade is similar to a relay race, with different hormones acting as runners that pass the ‘stress response’ baton. In the first leg of the race, hormones carry the baton from the hypothalamus to the brain structure that acts as the hormonal control center

called the pituitary gland, which releases hormones that control metabolism, blood pressure, and other physiological responses [11, 28, 30]. The second runner — the next set of hormones — carries the baton to the adrenal gland, which produces one particularly important hormone released in this process: cortisol, commonly known as the ‘stress hormone’ [10, 31]. Cortisol is also involved in immune function, as well as helping to regulate metabolism and blood pressure [10, 31]. Following its release, cortisol prompts the hypothalamus to cease the cortisol-producing hormone cascade [11, 32]. Similarly, once the relay runners cross the finish line, the race is over. The inhibition of the hormone cascade restores the body to a neutral state [10, 11]. Think of the HPA axis as a thermostat that adjusts to changing temperatures. When the thermostat senses that the temperature is warmer than the set temperature — such as when cortisol levels are elevated — the thermostat will turn off the heat. Once cortisol signals to the hypothalamus to stop sending signals to the pituitary gland, overall cortisol production will be reduced [10, 11]. The restoration of the body to a neutral state is key in acute stress responses, as it allows a person to focus on a stressor or task for the duration of the response and then return to regular functioning [10, 33]. When cortisol is regulated correctly, the HPA axis maintains the ability to utilize stress constructively [10, 11]. However, as most college students will report, stress does not always feel healthy [33, 34].

During states of chronic stress, prolonged activation of the HPA axis leads to hypercortisolism, a condition characterized by excess cortisol production [11, 26, 35]. In the early stages of burnout, symptoms have been heavily associated with hypercortisolism — excess cortisol release — highlighting a link between overactivation of the HPA axis and burnout [26, 35, 36]. With that said, severe burnout has also paradoxically been associated with hypocortisolism, a condition characterized by reduced cortisol release from the HPA axis [36, 37]. Hypercortisolism eventually transforms into hypocortisolism as the body stops being able to produce cortisol efficiently in response to constant stress [37, 38, 39]. After experiencing heightened levels of cortisol, individuals may experience a blunted stress response caused by hypocortisolism that can manifest as negative feelings, depressed mood, and reduced task-related motivation [4, 5, 40]. For a burnt-out student, a blunted stress response during burnout might look like having significantly lower motivation to study or perform well and believing they will get a bad grade regardless of their efforts.

While the physiological ramifications of hypocortisolism remain understudied, hypercortisolism has been connected to negative health outcomes such as altered cardiovascular function and impaired stress response [6, 41, 42]. During a stress response, hypercortisolism can additionally lead to the dysregulation of metabolic processes, wherein the body struggles to process carbohydrates, fats, and sugars [6, 43, 44]. Excess levels of cortisol from the chronic stress response can make it harder for the body to manage blood sugar, sometimes leading to hyperglycemia, or an excess of sugar in the blood [45, 46, 47]. Chronic stress also activates the body’s immune system, releasing inflammatory molecules called cytokines in order to attempt to attack the stressor and stop the endless stress response cycle [48, 51]. While inflammation is helpful in short bursts, persistent inflammation, caused by the sustained activation of the HPA axis, can disrupt metabolism, making it harder to control blood sugar and contributing to weight gain as well as other health risks [47, 49, 50]. Usually, when blood sugar rises, the body signals the pancreas to release insulin, the hormone that allows cells to absorb energy from sugar [52]. Insulin, however, becomes less effective during chronic inflammation due to the cytokines disrupting the insulin signaling pathway [47]. When cells cannot properly take in sugar, it remains in the bloodstream, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and other metabolic problems [53, 54, 55]. In this way, chronic stress can create a cycle where elevated cortisol and inflammation interfere with the body’s ability to handle sugar and fat, putting longterm health at risk [56, 57]. There are often physiological consequences to psychological processes, such as stress. The HPA axis is a significant example of that brain-body connection [58, 59]. For instance, people with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder experience more physical health issues than the general population [60, 61]. These disorders are all associated with chronically high levels of psychological distress, similar to burnout, which may explain the equivalent health risks [60, 62, 63]. Long-term physiological changes, such as increased inflammation due to chronic stress, can in turn result in the deterioration of tissue in the nervous system [11, 64]. Psychological symptoms of burnout such as cynicism and emotional exhaustion are also coupled with structural changes in the brain, specifically in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which is involved in

regulating stressors [24, 65, 66]. Shrinkage of the vmPFC has been linked to dysregulated HPA axis responsivity and it is possible that this impairment could be due to burnout [65, 66, 67]. Furthermore, burnout may lead to more serious physical conditions culminating in increased mortality below age 45 [85, 86].

Burnout, as well as hypercortisolism, often accompanies symptoms such as higher levels of depression, lack of satisfaction with job performance, and substantially altered HPA axis activity [10, 68, 69]. At a societal level, burnout has been concerningly correlated with decreased job performance in critical professions such as nursing, causing a lower quality of patient care [70, 71]. Similar to nurses, other medical professionals are at high risk for burnout due to their high-stakes work environment, which should be reason enough to sound the alarm for access to reliable burnout prevention [69, 72]. Knowing that burnout can be detrimental to long-term psychological and physical well-being, the logical next step is to investigate the ways that burnout could be prevented or mitigated. Physical exercise, including yoga as well as aerobic and strength exercises, has been shown to

reduce burnout symptoms and overall stress [73, 74]. Physical exercise can reduce stress via increased production of serotonin — a hormone involved in both emotional regulation and cognitive function [73, 75]. Interestingly, mindfulness-based practices do not show a decrease in burnout, but they do seem to alleviate symptoms such as anxiety and poor mood [76, 77, 78]. If a stressed student is feeling burned out after their midterm and tries to help themselves by engaging in a mindfulness-based practice like meditation, they might feel a short-term reduction in anxiety and be in a better mood. However, while these shortterm effects may be achieved, meditative practices are unlikely to improve cortisol levels in the body and will not change how burned-out the student actually feels [74, 78]. It is critical to consider the effects that burnout has on society to prioritize reliable burnout prevention and reduction strategies. As established, healthcare workers are particularly vulnerable to burnout due to their intense work schedules and the stakes of their jobs [69, 70]. Strategies that focus on reducing burnout in a particular individual include reducing monotony in the workday by varying everyday responsibilities as well as receiving guidance from peers and counselors to mediate the effects of burnout before they escalate [79, 80, 81]. On a larger scale, those working high-demand jobs, like doctors, benefitted greatly from structural and policy change such as the alteration of work schedules for more reasonable hours, and the introduction of medical scribes [71, 82, 83]. Structural changes in the healthcare system are needed to reduce physician burnout, an issue that is affecting quality of healthcare [70, 71, 82].

Given the prevalence of burnout today, understanding the complex effects of burnout and chronic stress on the body is profoundly important [69, 70]. More than half of US physicians are now experiencing professional burnout [84]. High-risk populations, like healthcare professionals, require reliable ways to prevent and reduce burnout symptoms to improve both their health and their service to patients [69, 70]. Investigations of burnout prevention strategies have proven that not only is individual treatment required in the form of physical stress-busters, but importantly, that large-scale change is needed to refine the systems that generate lasting burnout for healthcare workers [87, 88]. Burnout has been proven to be a physiological phenomenon in addition to a psychological one, as evidenced by the effects of chronic stress on both the brain and body [4, 5, 6]. With the knowledge that acute stress is a normal and helpful response, we should strive to embrace stress in a healthy manner while also being mindful of the possible consequences of chronic stress [10, 12, 14].

References on page 67.

by

*Note: This article uses female-gendered language to refer to pregnant and postpartum people due to the vast majority of cited literature being focused on female-identifying subjects. The editors wish to acknowledge that pregnancy is independent of gender identity.

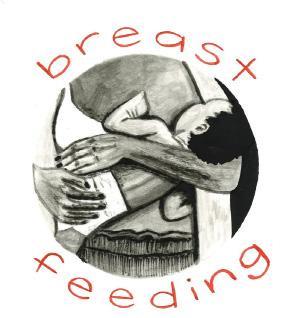

What if someone told you that since the moment you were born, and possibly even before that, tiny creatures have been living throughout your body, quietly helping you go about your life? No, it’s not your fairy godmother; it’s microbes! Microbes are microscopic organisms that are undetectable to the naked eye, yet have an enormous impact on human lives [1, 2]. You may know microbes as the cause of some diseases, but the majority of microbes are harmless and are actually beneficial [3, 4]. In particular, microbes residing in the gut are integral to human health [5, 6]. However, the impacts of microbes are not limited to the host they inhabit; they can even shape the health of future generations through the maternal-fetal relationship [7]. Maternal microbiota — referring to all of the microbes of a mother — can influence neurodevelopment both before and after birth, highlighting how bacteria support human function from the earliest stages of development [8]. To understand how maternal microbiota may affect neonatal brain development, it is essential first to become familiar with the microbial communities that inhabit the human body and their unique characteristics.

When you eat, you are not only providing sustenance for your body, but also for the trillions of microbes that live inside you [9]. The human body harbors various communities of microbes, and the gut microbiome is home to the most concentrated one [2]. The human gut microbiome refers to the collection of microorganisms that live in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which consists of the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine [10]. Much like a natural ecosystem, the gut microbiome relies on intricate interactions among its microbes to maintain balance and function [11]. Microbes live together in much the same way that organisms coexist in a coral reef: coral rely on algae for energy, algae rely on fish waste for nutrients, and fish rely on coral for shelter, maintaining an optimal and delicate harmony [12]. If an invasive species, such as a lionfish, were introduced to the reef, the balance would unravel — smaller fish would vanish, algae would overgrow, and the coral would

begin to die off, destabilizing the entire ecosystem [13]. Similarly, proper functioning of the gut microbiome depends on symbiotic interactions between the host and other microbes [5, 14]. For example, the bacteria Oxalobacter formigenes break down oxalate, a compound that can lead to kidney stone development, and in return, the bacteria gain nutrients and energy from the host [15, 16]. The gut microbiome is both dynamic and interdependent, and even minor disturbances can contribute to extremely detrimental effects [5].

Despite the misconception that all bacteria are harmful, microbes throughout the body have developed mutually beneficial relationships with their hosts that are crucial for the survival of both [ 4,9]. Gut microbiota help maintain a stable internal environment in the body, defend against foreign invaders, and synthesize metabolites — small molecules that support digestion, immunity, and communication between cells [17, 18]. In addition, gut microbiota are involved in regulating the immune response, wherein the body recognizes, identifies, and eliminates foreign substances while supplying essential nutrients like vitamins [9,19]. The specific composition of microbial species in the gut varies considerably between individuals and is influenced by factors like diet, environment, and lifestyle, each of which introduces new microbes and shapes the microbial community of the GI tract [9, 20]. Although no two people share the same microbial species composition, the bacteria generally perform similar functions across all individuals [9, 21].

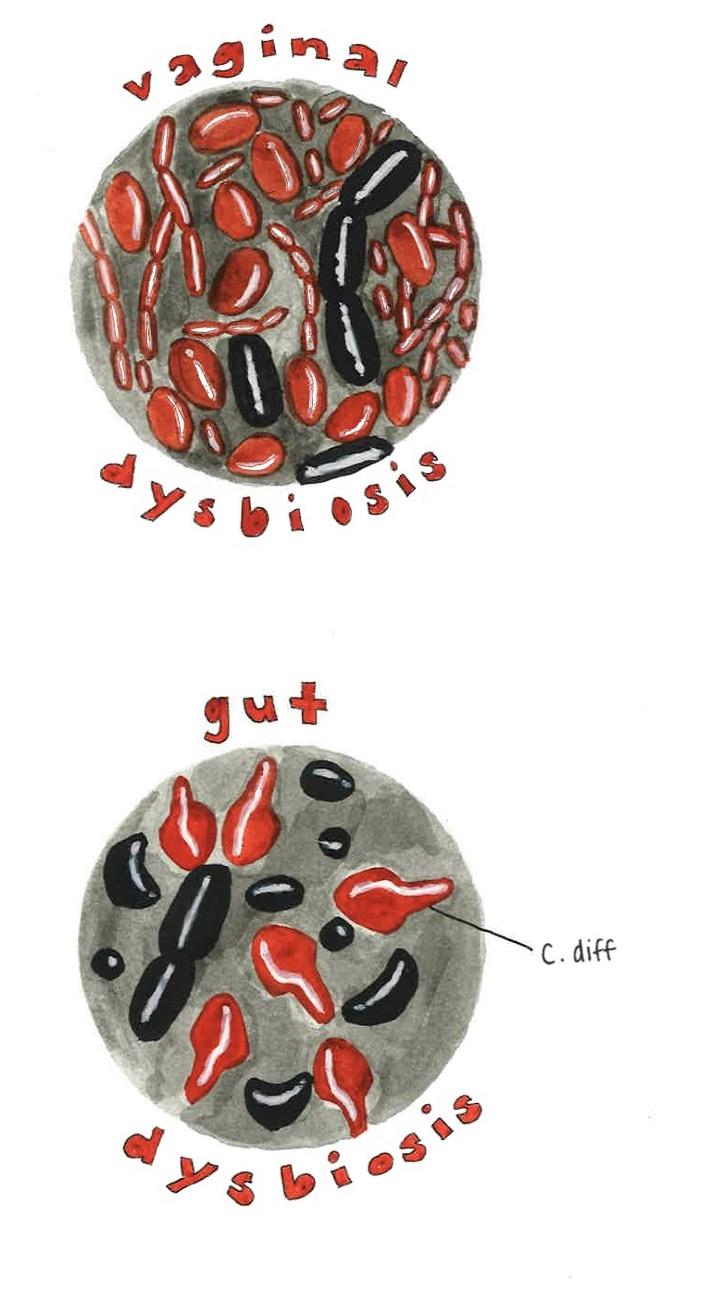

A balanced gut microbiome facilitates proper bodily functions, while deviations can be detrimental to overall health [22]. Disruption of this balance can lead to gut dysbiosis, a condition in which the composition or function of the gut microbiome is altered due to a loss of beneficial bacteria, an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, or a reduction in the variety of microorganisms present [22, 23]. Specifically, pathogenic bacteria cause disease, whereas non-pathogenic bacteria generally do not harm their host [24, 25]. One pathogenic bacterium that can cause

infection is Clostridiodes difficile, which infects the gut microbiome and induces diarrhea and other severe intestinal issues [26, 27]. However, when the host is in a weakened state, even non-pathogenic bacteria can become dangerous by attacking the host and causing illness [25, 28]. Maintaining microbial balance requires several physical and chemical defenses. For example, the mucus layer, which coats the intestinal cell surface, serves as the first line of defense against pathogenic bacteria and protects the gut lining [29, 30]. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) inhabits the mucus layer and typically aids in the processing and digestion of carbohydrates like fiber, starches, and sugars [31, 32]. During periods of prolonged carbohydrate deficiency, B. theta may begin degrading the gut’s sugar-composed mucus layer, making the host more susceptible to infection [30]. Therefore, even beneficial bacteria like B. theta can contribute to dysbiosis when environmental or nutritional imbalances disrupt the gut microbiome [30].

Microbiomes exist in multiple locations throughout the body, not just the gut. The vaginal microbiome is another finely tuned ecosystem where microbial balance plays a crucial protective role [33]. In both pregnant and non-pregnant women, the vaginal microbiome is typically dominated by the Lactobacillus genus, which is the primary producer of lactic acid, thereby lowering vaginal pH and limiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria [33, 34, 35]. Beneficial vaginal microbes thrive in acidic conditions, whereas many pathogenic bacteria struggle to survive [35].